Summary

Numerous pathological changes of subcellular structures are characteristic hallmarks of neurodegeneration. The main research has focused to mitochondria, endoplasmic reticulum, Golgi apparatus, lysosomal networks as well as microtubular system of the cell. The sequence of specific organelle damage during pathogenesis has not been answered yet. Exposition to rotenone is used for simulation of neurodegenerative changes in SH-SY5Y cells, which are widely used for in vitro modelling of Parkinson’s disease pathogenesis. Intracellular effects were investigated in time points from 0 to 24 h by confocal microscopy and biochemical analyses. Analysis of fluorescent images identified the sensitivity of organelles towards rotenone in this order: microtubular cytoskeleton, mitochondrial network, endoplasmic reticulum, Golgi apparatus and lysosomal network. All observed morphological changes of intracellular compartments were identified before αS protein accumulation. Therefore, their potential as an early diagnostic marker is of interest. Understanding of subcellular sensitivity in initial stages of neurodegeneration is crucial for designing new approaches and a management of neurodegenerative disorders.

Keywords: Parkinson’s disease, α-synuclein, Neurodegeneration, Mitochondria, Endoplasmic reticulum, Golgi apparatus, Microtubules, Lysosomes, Fluorescence microscopy

Introduction

Neurodegenerative disorders can be identified as a class of neurological diseases sharing similarities in course of intracellular pathology. Most typical hallmark of neurodegeneration, specific protein accumulation, is accompanied by presence of other intracellular processes that lead to dysfunction of subcellular structures. In case of Parkinson’s disease, accumulation of α-synuclein (αS) and formation of advanced aggregates, which are finally incorporated to Lewy bodies are considered to be a major hallmark (Braak et al. 2003).

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is the second most prevalent neurodegenerative disorder worldwide (Polito et al. 2016). Wide variety of parallel and/or preceding changes occur during pathology of PD. Given the volume of data on this topic, mitochondrial dysfunction, presented mainly by disruption of the respiratory chain with consequent increased reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, is still considered to play an integral role in intracellular pathogenesis (Perfeito et al. 2012, Park et al. 2018). Mitochondrial network is actively sustained in a healthy condition by balanced fusion and fission processes that coordinate mitochondrial degradation by mitophagy (Park et al. 2018). Mitochondrial membrane dynamics is properly regulated by range of molecular factors. Except the others, αS is predominantly expressed by neuronal cells and appears to be closely related to mitochondrial dynamic processes. Overexpression of αS has toxic effects on mitochondrial physiology. Higher level of protein can stimulate mitochondrial fragmentation, Ca2+ signaling disruption as well as a decrease of effectivity of respiratory chain, mainly complex I (Vicario et al. 2018). Special status of mitochondrial complex I is given by the fact, that its inhibition is platform for overexpression of αS in experimental in vivo as well as in vitro models of PD (Giraldez-Perez et al. 2014). Role of αS is particularly evident at the junction sites with ER (MAM), which are critically involved in regulation of mitochondrial processes (Guardia-Laguarta et al. 2014). Beside the primary function of ER like protein synthesis, glycosylation, and folding (Schroder and Kaufman 2005), importance of this organelle is crucial in regulation of mitochondrial function and vice versa (Rizzuto et al. 1998, Gomez-Suaga et al. 2018). Inconvenient environmental conditions associated with increased need for the synthesis or repair of misfolded proteins is generally specified as an ER stress, a hallmark of onset of various metabolic and inflammatory disorders as well as neurodegenerative diseases (Apostolova et al. 2013, Omura et al. 2013, Wikstrom et al. 2013).

Apart from mitochondria and ER, αS is involved in dynamic membrane processes during vesicular transport (Lautenschlager et al. 2017). The Golgi network system, which consists of parallel sets vesicles carrying cargo, plays a dominant role in intracellular vesicle trafficking. Disruption of this tightly regulated network system, leads to its fragmentation, which is characteristic for different types of neurodegenerative disorders with no exception of PD (Gonatas et al. 2006). In addition to vesicular based trafficking, membrane dynamics is crucial condition for autophagy and recycling processes, where lysosomes play a prominent role. Recently, lysosomal insufficiency has been described as the cause of PD pathology in number of patients, who were supposed to suffer from idiopathic PD (Klein and Mazzulli 2018). Disruption of microtubule turnover, as a fundamental component of cytoskeleton and infrastructure demanded for cargo transport in neurons, is further strongly discussed phenomenon in context of neurodegenerative diseases (Dubey et al. 2015).

According to summarized knowledge, it is concluded that cells of neuronal origin can accumulate pathological features of neurodegeneration at almost all types of subcellular structures. Majority of experimental studies were focused on solitary pathogenesis of chosen organelle, while general insight into organelles changes is still missing. Deeper analysis of organelle sensitivity in induction of neurodegenerative changes is crucial for designing new approaches and the management of neurodegenerative disorders. The aim of this study was to describe the temporal sequence of neurodegenerative pathogenesis of the most affected organelles: mitochondria, ER, Golgi apparatus, lysosomal network and microtubular cytoskeleton, in the rotenone influenced SH-SY5Y cell model.

Methods

Cell culture and rotenone use

Human SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells (CRL-2266; ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA) were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s media (DMEM) supplemented with 10 % fetal bovine serum (FBS, Biosera) and 1× Penicillin/Streptomycin (1× PS; Biosera) at 37 °C in a 5 % CO2 humidified atmosphere. For rotenone (Sigma, R8875) exposition, final concentration of drug was achieved by dilution of concentrated stock solution into growth medium. All procedures were repeated for at least 3 times and the most representative pictures were chosen for presentation.

Oxidative stress level evaluation

Measurement of ROS generation was performed by CellROX-orange oxidative reagent (Life technologies, C10443). Test was performed on 96-well plate with 15000 cells per well according to manufacturer protocol. Fluorescence emission at 565 nm was measured after 545 nm excitation. Measurement was repeated 4 times with 4 biological replicates in time points 0 h, 2 h, 4 h, 24 h. Data is presented as a percentage fold change against control sample.

Rotenone cytotoxicity evaluation and ATP synthesis

The toxic effects of rotenone were evaluated with the Mitochondrial Toxicity Test (Promega, G8001), based on the simultaneous measurement of ATP production by mitochondria (luminescence), as well as by evaluating the proportion of apoptotic/necrotic cells whose cell membrane is permeable to the fluorescent substrate (485/530 nm). Sample analysis was performed in already indicated time points, biological replicates and the cell number similar as for evaluation of ROS generation. Protocol procedure was executed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Filters for excitation/emission were set up on 485/530 nm. Data was analyzed by GraphPad Prism software and presented as a relative change of samples versus control sample.

Mitochondrial complex I activity measurements

Mitochondrial respiration was measured by high-resolution respirometry performed in a two chamber system O2k-FluoRespirometer (Oroboros Instruments, AT) according to Evinova et al. (2020). Inhibitory potential of rotenone on complex I was assigned by sequential addition of elevating rotenone concentrations. Measurements were repeated two times.

Immunocytochemistry

For visualization of αS and βIII-tubulin, SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells were fixed in 4 % paraformaldehyde (PFA), permeabilized in PBS with 0.1 % Triton X-100, and blocked with PBS supplemented with 5 % bovine serum albumin (BSA, Sigma). Cells were then incubated with primary mouse anti-α-synuclein (Abcam, ab1903) and rabbit anti-βIII tubulin. The counterstaining was performed with anti-mouse IgG-AlexaFluor-488 Alexa (ThermoFisher scientific, A-11001) and goat anti-rabbit IgG AlexaFluor-594 antibody (ThermoFisher Scientific, A-11037).

Live cell staining

Prior to live cell staining, cells were grown to approximately 50–60 % confluence. The staining was performed to visualize the mitochondria, Golgi apparatus, endoplasmic reticulum and lysosomes. MitoTracker®Red FM (MTR, Invitrogen, M22425), ER-tracker Blue-White DPX (ThermoFisher Scientific, E12353), LysoTracker Red DND-99 (ThermoFisher Scientific, L7528) and BODIPY™ FL C5-Ceramide complexed to BSA (ThermoFisher Scientific, B22650) was used to display organelles in vivo.

Confocal microscopy

Fluorescence images were acquired with a Carl Zeiss LSM 880 NLO confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss AG, Jena, Germany). For the analysis of fixed cells Plan Apochromat 63×/1.4 Oil DIC objective was used. Living cells were analyzed using a W Plan Apochromat 40×/1.0 DIC objective. The same confocal system parameters were retained for the entire set of images for samples stained by one fluorescent dye/antibody.

Statistical analysis

Data was analyzed by one-way ANOVA. Treated groups were compared to control (0 h) samples for statistical significance. Results were expressed as mean ± SEM. Overall level of significance was defined as p<0.05. Data with p value less than 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Cytotoxic effect of rotenone

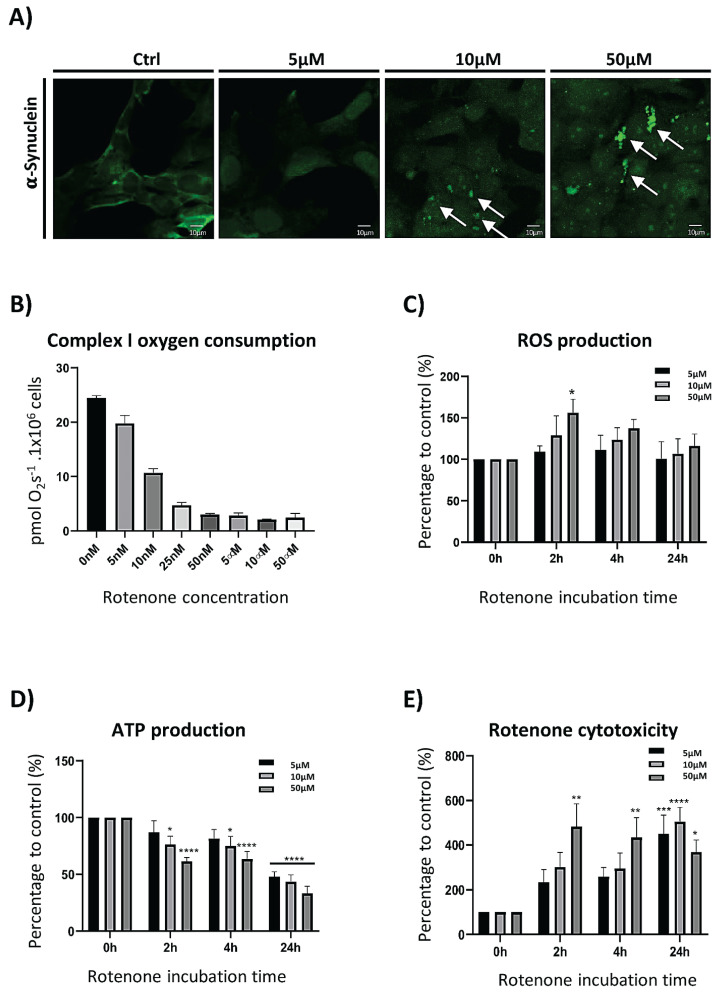

Rotenone, a mitochondrial complex I inhibitor, is highly evaluated because of its ability to reconstruct PD pathogenesis in high fidelity (Hisahara and Shimohama 2010). For the determination of rotenone effectivity in induction of PD-like pathology, we investigated the accumulation of αS. As shown in Figure 1A, 24 h exposure to 10 and 50 μM rotenone caused increase of αS, as documented by immunocytochemistry of SH-SY5Y cell line. Inhibition of complex I by 5 μM concentration of rotenone was insufficient in having the same effect after 24 h lasting exposure. In this time point, no accumulated signal from αS was visible. Chosen concentrations (μM) are known to have total inhibitory effect on complex I (Fig. 1B), although the oxygen consumption was still recognized by measurement of complex II respiration in cells exposed to measured concentrations for 24 h (data not shown). ATP synthesis alternative pathways are probably responsible for preservation of certain intracellular level of ATP, as seen on Figure 1D. According to our measurements, decrease of ATP concentration was dependent on rotenone concentration as well as on exposure time (Fig. 1D). Reactive oxygen species (ROS) production showed mild increase in initiation stages of rotenone exposure (2 h), and only 50 μM concentration was able to induce statistically significant relative increase of ROS (Fig. 1C). 50 μM concentration was also able to induce 5-fold increase in cell death rate, after only 2 h. Longer period was needed to obtain the same effect, if 5 μM or 10 μM concentration was used (Fig. 1E).

Fig. 1.

Characterization of rotenone effect on SH-SY5Y cell line. (A) Dose dependence of αS accumulation in SH-SY5Y cells on rotenone 24 h exposition. Green dots of accumulated αS are marked by arrows. (B) Graphical illustration of rotenone impact on complex I respiration in different concentrations. (C, D, E) Effects of rotenone concentrations (5, 10, 50 μM) on reactive oxygen species production, ATP depletion and increase of cell death in time.

Rotenone affects primarily morphology of microtubules

Comparison of rotenone efficiency to induce the morphological changes led us to identify microtubular network as the most vulnerable cell compartment from the chosen panel of subcellular structures. Fibrillary pattern of microtubular fluorescence could be seen in all images obtained from control cells (Fig. 2A). The only 1 h exposure of rotenone was responsible for disruption of fibrillary character of cytoskeleton fluorescence and its substitution by diffuse fluorescence pattern. Without exception, described remodeling was observed for every rotenone concentration used (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 2.

Rotenone-induced morphological changes in microtubules and mitochondria. (A) Fluorescence signal pattern of microtubules after different concentrations of rotenone presence for 1 h. Fibrillary microtubules in control cells are substituted by diffuse fluorescence after microtubular depolymerization already after 1 h of rotenone exposure. (B) Demonstration of mitochondrial fluorescence change in 5, 10, 50 μM rotenone after 1 h (C) Graphical illustration of significant increase observed in fluorescence intensity of MitoTracker red FM analysed in time course.

Morphological changes occurring in mitochondria and ER confirm interconnections between these two organelles

Association of mitochondria and ER is well documented fact. Fluorescent dye “MitoTracker Red FM” was used for imaging of mitochondrial network. Indicated fluorescent probe is transported only by active mitochondria. Quantitative analysis of fluorescence intensity revealed strong increase in fluorescence signal levels after exposition by rotenone in 50 and 10 μM concentration (Fig. 2B, C). The increase is evident shortly after supplement of complex I inhibitor (Fig. 2C). The opposite situation can be seen on ER fluorescence imaging. Membrane bound fluorescence probe exerts significant decrease of signal after 1 h as well as 24 h rotenone exposure (Fig. 3A, C). After disappearance of diffuse or “healthy” ER signal from the cells, small sacks from ER based fluorescence remain visible (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

Rotenone-induced morphological changes in Endoplasmic reticulum. (A) Examples of endoplasmic reticulum visualizations by ER-tracker after different concentrations of rotenone in time. (B) Sack-like cisternae relevant for ER stress establishment are marked by white arrows after 24 h of rotenone effect in 50 μM, while absence of their formation is seen in control cells. (C) Graphical illustration of significant decrease observed in fluorescence intensity of ER tracker analysed in time course.

Decreased (5 μM) rotenone concentration promoted less significant morphological changes in both organelles. Although these subcellular compartments exert high degree of interconnection, mitochondrial network seems to be more significantly affected in time after 5 μM exposition. Increase of fluorescence signal after MitoTracker staining was strongly significant after 1 h exposure (Fig. 2C). Slightly lower vulnerability of ER was evident when the robustness of fluorescence changes was compared. Statistical significance of ER fluorescence decay caused by rotenone decreased in each time point of 5 μM exposition (Fig. 3C).

Golgi apparatus morphological change tightly follows ER, while lysosomes are the most resistant organelles

Similarly, like in the case of microtubules, qualitative morphological changes can be observed after visualization of Golgi apparatus in control and rotenone affected cells by ceramide derived fluorescent probe. Perinuclear and well centralized Golgi apparatus in control cells was in evident contrast with fragmented pattern of the same organelle imaged after 1 h exposure of 10 and 50 μM rotenone (Fig. 4A). Slower and diminished effects were observed after the use of 5 μM rotenone, while trend for fragmentation was recognized after 4 h of exposition finally (Fig. 4A).

Fig. 4.

Rotenone-induced morphological changes in Golgi apparatus and Lysosomes. (A) Golgi apparatus fragmentation was observed in 10, 50 μM rotenone 1 h exposition. 5 μM caused qualitative change after 4 h delay. Fragmented Golgi could be observed as a small vesicle with intensive green fluorescence scattered through cellular volume. Control cells are characteristic by presence of Golgi apparatus centralized in peri-nuclear region of cell. (B) Demonstration of lysosomal fluorescence change after 4 and 24 h rotenone presence in 50 μM concentration (C) Increase of lysosomal diameter in time course of rotenone presence (50 μM).

Morphological changes of lysosomal network were observed as well. Highest concentration of rotenone (50 μM) induced statistically significant change of lysosomal appearance after 4 h as intensive increase of lysosomal diameter has been recognized (Fig. 4B, C). In case of lysosomes, changes were detected as the slowest registered rotenone induced effect inside the cell.

Discussion

Experimental design of this study was set up for the purpose of complex insight on intracellular remodeling relevant for neurodegeneration. Cellular toxic model that is based on mitochondrial complex I inhibitor – rotenone, was selected amongst the other variants of neurodegeneration inducing agents, because of its higher fidelity in recapitulating of PD intracellular hallmarks (Hisahara and Shimohama 2010). All observed phenomena running at subcellular structures in SH-SY5Y cells were correlated in time. It helped us to determine the vulnerability of specific organelle in neurodegeneration recalling mainly PD-like pathology.

Firstly, characterization of rotenone effect had to be performed. Our results indicate, that rotenone (10 and 50 μM) exposure induce accumulation of αS between 4–24 h. More specifically, the αS accumulation (as detected by anti αS antibody) was determined at 24 h, while 4 h exposition by 50 μM rotenone was not able to cause αS accumulation (data not shown). Microscopic detection of αS expression with the lowest concentration (5 μM) used did not prove αS accumulation after 24 h (Fig. 1A). Upregulation of αS expression induced by rotenone is nowadays well documented fact, as could be seen in several published papers. The increase of expression by 50 and 100 % respectively was detected by western blot analysis performed with non-differentiated SH-SY5Y cells after 24 h exposure to 5/10 μM rotenone. Same study provides data showing the increase of Triton X-100 soluble/insoluble (available/aggregated) fraction of αS (Ramalingam et al. 2019). Also, the lower concentrations (0.1–200 nM) led to the overexpression and aggregation of αS, however with the longer exposure time needed and with the use of primary or differentiated neurons (Borland et al. 2008, Radad et al. 2008, Sala et al. 2013, Chaves et al. 2016).

Rotenone, as a potent inhibitor of complex I is able to block complex I activity in the concentration of 25–50 nM within minutes in undifferentiated SH-SY5Y cells (Fig. 1B). According to obtained results, it is evident that increasing potential of rotenone on αS accumulation is observable in dose dependent manner of concentrations 5–50 μM. Presence of other rotenone target outside from mitochondria is therefore highly relevant and also well documented by several studies published over the last decade (Srivastava and Panda 2007). Rotenone binding ability to α-tubulin is confirmed, as well as its strong depolymerizing effect on microtubular cytoskeleton observed at 10 μM and higher concentration during 3, 6 and 24 h (Passmore et al. 2017).

Other field of intracellular processes with high relevance in PD evolvement is reactive oxygen species (ROS) production. Rotenone as an inductor of neurodegeneration is significant player in ROS upregulation. Our results also indicate, that short (2 h) exposure to 50 μM concentration of rotenone significantly increased concentration of ROS in SH-SY5Y cells (Fig. 1C). Although huge fraction of ROS produced inside the cell has mitochondrial origin (Chen et al. 2003), the strongest effect of rotenone on complex I was seen at 50 nM, while elevation of ROS seems to be dose dependent in 5–50 μM concentration range. Similarly, like mentioned above, another affected target is therefore probable. Out of mitochondria, rotenone is able to induce ROS production by inducing of NADPH oxidase activity after binding to this enzyme (Zhou et al. 2012). Enforcement of rotenone effects through activation of NADPH oxidase is dose dependent in 0.5 μM and 10 μM concentration range (Pal et al. 2016). Continuous attenuation of ROS levels during the prolonged exposure to rotenone (Fig. 1C) could be assigned to compensatory mechanism, as well as to deceleration of cellular metabolism.

Lowering of the metabolic rate together with higher cell death rate is imaged by ATP and cytotoxicity measurements (Fig. 1D, E). ATP synthesis restriction caused preservation of ATP concentration on the level between 30–50 % of normal production. Maximal cell death measured in our study is 4–5 times higher compared to control. These results, especially effect of rotenone at 50 μM, should reflect approximately 50 % survival of SH-SY5Y cell population after 24 h with 60 μM rotenone (Zhang et al. 2018). Almost 40 % of SH-SY5Y survival rate was observed by another group of authors after 24 h incubation with 10 μM rotenone concentration (Ramalingam et al. 2019). Concentration of 0.8 μM used for 24 h in another study led to survival of 60 % of SH-SY5Y cells (Sala et al. 2013).

Rotenone is an inducing agent of complex intracellular pathogenesis, which mimics pathology relevant mainly for PD. The earliest changes revealed by microscopy analysis were those related to the microtubules. Every concentration of rotenone that was used, led into qualitative change of microtubules structure from fibrillary to diffuse staining pattern after first 1 h of exposure (Fig. 2A). Rotenone used in concentration ranged from 0.1 to 50 μM in HeLa cells has retarded several dynamic actions of microtubules after minutes of incubation (Srivastava and Panda 2007). As in experimental models of PD, shrinkage of axons accompanied with disruption of intracellular traffic along microtubules is common in real PD cases (Pellegrini et al. 2017). As a conclusion, a rapid change of microtubules serves as platform for subsequent morphological changes observed consequently after microtubule depolymerization.

Mitochondrial fluorescence elevation detectable after staining with MitoTracker Red FM dye was dose dependent, with only 25 % increase after 1 h incubation with 5 μM rotenone and more than 100 % when higher concentrations was used. The increase of fluorescence emitted by MitoTracker Red FM dye reflects hyperpolarized mitochondria. Although our expectations were opposite, effect of rotenone strongly depends on cell type used in experiment. Rat liver cells treated by 2.5–5 μM rotenone exerts about 20–30 % decrease observed for 360 min (Isenberg and Klaunig 2000). Mouse bone marrow-derived macrophages treated with 10 μM rotenone for 2 h showed slightly increase of fluorescence of MitoTracker (Won et al. 2015). Only 1–10 nM concentration of rotenone for 24 h resulted in increase of MitoTracker fluorescence in rat primary cortical neurons (Giordano et al. 2014). Significant elevation of MitoTracker signal was recognized after 24 h of incubation with 10 μM rotenone in motor neurons NSC34 (Jung et al. 2015). Compensatory adaptation or fusing processes of mitochondria could be hypothesized, but both of them need to be further investigated.

Results obtained during microscopic analysis provided supporting data on tight connections of mitochondria and ER. Statistically significant decrease of ER fluorescence followed closely changes in mitochondria. However, after 5 μM rotenone incubation, the decrease of ER was not so significant in comparison to mitochondrial change. Character of quantitative change is difficult to explain due to absence of relevant studies. Decrease of signal could be cell type specific and needs future investigation. Appearance of small vesicle-like structures with strong fluorescence intensity (Fig. 3B) is in agreement with earlier observation of Batova et al. (2017). Induction of ER stress in renal carcinoma cells by Englerin A was accompanied with formation of similar sack-like cisternae (Batova et al. 2017). Observations talks clearly in favor of ER stress establishment in rotenone model.

Golgi apparatus as an organelle with crucial role in intracellular transport exerts prolonged time (4 h) of response to 5 μM rotenone in comparison with already discussed structures (Fig. 4A). Fragmented pattern of Golgi is in agreement with similar observations after experimental depolymerization of microtubular cytoskeleton (Rogalski et al. 1984) as well as during real neurodegeneration process (Gonatas et al. 2006).

The slowest change was observed in context of lysosomal network remodeling. Lysosomes responded to 50 μM rotenone finally with significance after 4 h (Fig. 4B, C). Detection of larger (in diameter) lysosomal vesicles probably means activation of autophagy after rotenone induced damage (Giordano et al. 2014). Activation of autophagy-lysosomal pathway is described quite properly in neurodegenerative disorders (Adamec et al. 2000, Yu et al. 2004). Actual studies on SH-SY5Y cells focus mainly on dysfunction on molecular signaling pathways. Presented results provide essential information on reactivity of lysosomes and their morphology change in time after induction of degenerative processes.

According to the discussed facts, it could be summarized, that rotenone showed confirmed cytotoxic effects via impact on mitochondria, microtubules and NADPH oxidase. All three aspects are present in wide proportion of real PD and other types of neurodegeneration and seems to be mandatory for evolvement of broad pathogenesis of intracellular structures. Vulnerability of specific organelles amongst the others hasn’t been yet evaluated completely. Presented results are first that map simultaneously sensitivity of five crucial subcellular structures during initiation of neurodegeneration, which is mostly relevant to PD. The appearance of quantitative as well as qualitative changes observed in morphology precedes detectable protein accumulation. All observed hallmarks therefore own diagnostic potential as a candidate for early morphological hallmark of several types of neurodegeneration.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by VEGA 1/0334/18 and VEGA 1/0299/20.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

There is no conflict of interest.

References

- ADAMEC E, MOHAN PS, CATALDO AM, VONSATTEL JP, NIXON RA. Up-regulation of the lysosomal system in experimental models of neuronal injury: implications for Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroscience. 2000;100:663–675. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4522(00)00281-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- APOSTOLOVA N, GOMEZ-SUCERQUIA LJ, ALEGRE F, FUNES HA, VICTOR VM, BARRACHINA MD, BLAS-GARCIA A, ESPLUGUES JV. ER stress in human hepatic cells treated with Efavirenz: mitochondria again. J Hepatol. 2013;59:780–789. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BATOVA A, ALTOMARE D, CREEK KE, NAVIAUX RK, WANG L, LI K, GREEN E, WILLIAMS R, NAVIAUX JC, DICCIANNI M, YU AL. Englerin A induces an acute inflammatory response and reveals lipid metabolism and ER stress as targetable vulnerabilities in renal cell carcinoma. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0172632. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0172632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BORLAND MK, TRIMMER PA, RUBINSTEIN JD, KEENEY PM, MOHANAKUMAR K, LIU L, BENNETT JP., JR Chronic, low-dose rotenone reproduces Lewy neurites found in early stages of Parkinson’s disease, reduces mitochondrial movement and slowly kills differentiated SH-SY5Y neural cells. Mol Neurodegener. 2008;3:21. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-3-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BRAAK H, Del TREDICI K, RUB U, De VOS RA, JANSEN STEUR EN, BRAAK E. Staging of brain pathology related to sporadic Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2003;24:197–211. doi: 10.1016/S0197-4580(02)00065-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHAVES RS, KAZI AI, SILVA CM, ALMEIDA MF, LIMA RS, CARRETTIERO DC, DEMASI M, FERRARI MFR. Presence of insoluble Tau following rotenone exposure ameliorates basic pathways associated with neurodegeneration. IBRO Rep. 2016;1:32–45. doi: 10.1016/j.ibror.2016.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHEN Q, VAZQUEZ EJ, MOGHADDAS S, HOPPEL CL, LESNEFSKY EJ. Production of reactive oxygen species by mitochondria: central role of complex III. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:36027–36031. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304854200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DUBEY J, RATNAKARAN N, KOUSHIKA SP. Neurodegeneration and microtubule dynamics: death by a thousand cuts. Front Cell Neurosci. 2015;9:343. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2015.00343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EVINOVA A, CIZMAROVA B, HATOKOVA Z, RACAY P. High-resolution respirometry in assessment of mitochondrial function in neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y intact cells. J Membr Biol. 2020;253:129–136. doi: 10.1007/s00232-020-00107-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GIORDANO S, DODSON M, RAVI S, REDMANN M, OUYANG X, DARLEY USMAR VM, ZHANG J. Bioenergetic adaptation in response to autophagy regulators during rotenone exposure. J Neurochem. 2014;131:625–633. doi: 10.1111/jnc.12844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GIRALDEZ-PEREZ RM, ANTOLIN-VALLESPIN M, MUNOZ MD, SANCHEZ-CAPELO A. Models of α-synuclein aggregation in Parkinson’s disease. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2014;2:176. doi: 10.1186/s40478-014-0176-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GOMEZ-SUAGA P, BRAVO-SAN PEDRO JM, GONZALEZ-POLO RA, FUENTES JM, NISO-SANTANO M. ER-mitochondria signaling in Parkinson’s disease. Cell Death Dis. 2018;9:337. doi: 10.1038/s41419-017-0079-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GONATAS NK, STIEBER A, GONATAS JO. Fragmentation of the Golgi apparatus in neurodegenerative diseases and cell death. J Neurol Sci. 2006;246:21–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2006.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GUARDIA-LAGUARTA C, AREA-GOMEZ E, RUB C, LIU Y, MAGRANE J, BECKER D, VOOS W, SCHON EA, PRZEDBORSKI S. alpha-Synuclein is localized to mitochondria-associated ER membranes. J Neurosci. 2014;34:249–259. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2507-13.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HISAHARA S, SHIMOHAMA S. Toxin-induced and genetic animal models of Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsons Dis. 2010;2011:951709. doi: 10.4061/2011/951709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ISENBERG JS, KLAUNIG JE. Role of the mitochondrial membrane permeability transition (MPT) in rotenone-induced apoptosis in liver cells. Toxicol Sci. 2000;53:340–351. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/53.2.340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JUNG SY, LEE KW, CHOI SM, YANG EJ. Bee venom protects against rotenone-induced cell death in NSC34 motor neuron cells. Toxins (Basel) 2015;7:3715–3726. doi: 10.3390/toxins7093715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KLEIN AD, MAZZULLI JR. Is Parkinson’s disease a lysosomal disorder? Brain. 2018;141:2255–2262. doi: 10.1093/brain/awy147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LAUTENSCHLAGER J, KAMINSKI CF, KAMINSKI SCHIERLE GS. alpha-synuclein - regulator of exocytosis, endocytosis, or both? Trends Cell Biol. 2017;27:468–479. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2017.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OMURA T, KANEKO M, OKUMA Y, MATSUBARA K, NOMURA Y. Endoplasmic reticulum stress and Parkinson’s disease: the role of HRD1 in averting apoptosis in neurodegenerative disease. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2013;2013:239854. doi: 10.1155/2013/239854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PAL R, BAJAJ L, SHARMA J, PALMIERI M, Di RONZA A, LOTFI P, CHAUDHURY A, NEILSON J, SARDIELLO M, RODNEY GG. NADPH oxidase promotes Parkinsonian phenotypes by impairing autophagic flux in an mTORC1-independent fashion in a cellular model of Parkinson’s disease. Sci Rep. 2016;6:22866. doi: 10.1038/srep22866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PARK JS, DAVIS RL, SUE CM. Mitochondrial dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease: New mechanistic insights and therapeutic perspectives. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2018;18:21. doi: 10.1007/s11910-018-0829-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PASSMORE JB, PINHO S, GOMEZ-LAZARO M, SCHRADER M. The respiratory chain inhibitor rotenone affects peroxisomal dynamics via its microtubule-destabilising activity. Histochem Cell Biol. 2017;148:331–341. doi: 10.1007/s00418-017-1577-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PELLEGRINI L, WETZEL A, GRANNO S, HEATON G, HARVEY K. Back to the tubule: microtubule dynamics in Parkinson’s disease. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2017;74:409–434. doi: 10.1007/s00018-016-2351-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PERFEITO R, CUNHA-OLIVEIRA T, REGO AC. Revisiting oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction in the pathogenesis of Parkinson disease--resemblance to the effect of amphetamine drugs of abuse. Free Radic Biol Med. 2012;53:1791–1806. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.08.569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- POLITO L, GRECO A, SERIPA D. Genetic profile, environmental exposure, and their interaction in Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsons Dis. 2016;2016:6465793. doi: 10.1155/2016/6465793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RADAD K, GILLE G, RAUSCH WD. Dopaminergic neurons are preferentially sensitive to long-term rotenone toxicity in primary cell culture. Toxicol In Vitro. 2008;22:68–74. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2007.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RAMALINGAM M, HUH YJ, LEE YI. The impairments of alpha-synuclein and mechanistic target of rapamycin in rotenone-induced SH-SY5Y cells and mice model of Parkinson’s disease. Front Neurosci. 2019;13:1028. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2019.01028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RIZZUTO R, PINTON P, CARRINGTON W, FAY FS, FOGARTY KE, LIFSHITZ LM, TUFT RA, POZZAN T. Close contacts with the endoplasmic reticulum as determinants of mitochondrial Ca2+ responses. Science. 1998;280:1763–1766. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5370.1763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROGALSKI AA, BERGMANN JE, SINGER SJ. Effect of microtubule assembly status on the intracellular processing and surface expression of an integral protein of the plasma membrane. J Cell Biol. 1984;99:1101–1109. doi: 10.1083/jcb.99.3.1101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SALA G, AROSIO A, STEFANONI G, MELCHIONDA L, RIVA C, MARINIG D, BRIGHINA L, FERRARESE C. Rotenone upregulates alpha-synuclein and myocyte enhancer factor 2D independently from lysosomal degradation inhibition. Biomed Res Int. 2013;2013:846725. doi: 10.1155/2013/846725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHRODER M, KAUFMAN RJ. ER stress and the unfolded protein response. Mutat Res. 2005;569:29–63. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2004.06.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SRIVASTAVA P, PANDA D. Rotenone inhibits mammalian cell proliferation by inhibiting microtubule assembly through tubulin binding. FEBS J. 2007;274:4788–4801. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2007.06004.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VICARIO M, CIERI D, BRINI M, CALI T. The close encounter between alpha-synuclein and mitochondria. Front Neurosci. 2018;12:388. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2018.00388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WIKSTROM JD, ISRAELI T, BACHAR-WIKSTROM E, SWISA A, ARIAV Y, WAISS M, KAGANOVICH D, DOR Y, CERASI E, LEIBOWITZ G. AMPK regulates ER morphology and function in stressed pancreatic beta-cells via phosphorylation of DRP1. Mol Endocrinol. 2013;27:1706–1723. doi: 10.1210/me.2013-1109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WON JH, PARK S, HONG S, SON S, YU JW. Rotenone-induced impairment of mitochondrial electron transport chain confers a selective priming signal for NLRP3 inflammasome activation. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:27425–27437. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.667063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YU WH, KUMAR A, PETERHOFF C, SHAPIRO KULNANE L, UCHIYAMA Y, LAMB BT, CUERVO AM, NIXON RA. Autophagic vacuoles are enriched in amyloid precursor protein-secretase activities: implications for beta-amyloid peptide over-production and localization in Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2004;36:2531–2540. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2004.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZHANG M, DENG YN, ZHANG JY, LIU J, LI YB, SU H, QU QM. SIRT3 protects rotenone-induced injury in SH-SY5Y cells by promoting autophagy through the LKB1-AMPK-mTOR pathway. Aging Dis. 2018;9:273–286. doi: 10.14336/AD.2017.0517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZHOU H, ZHANG F, CHEN SH, ZHANG D, WILSON B, HONG JS, GAO HM. Rotenone activates phagocyte NADPH oxidase by binding to its membrane subunit gp91phox. Free Radic Biol Med. 2012;52:303–313. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.10.488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]