Abstract

The rapid emergence of virulent and multidrug-resistant (MDR) non-typhoidal Salmonella (NTS) enterica serovars is a growing public health concern globally. The present study focused on the assessment of the pathogenicity and antimicrobial resistance (AMR) profiling of NTS enterica serovars isolated from the chicken processing environments at wet markets in Dhaka, Bangladesh. A total of 870 samples consisting of carcass dressing water (CDW), chopping board swabs (CBS), and knife swabs (KS) were collected from 29 wet markets. The prevalence of Salmonella was found to be 20% in CDW, 19.31% in CBS, and 17.58% in KS, respectively. Meanwhile, the MDR Salmonella was found to be 72.41%, 73.21%, and 68.62% in CDW, CBS, and KS, respectively. All isolates were screened by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for eight virulence genes, namely invA, agfA, IpfA, hilA, sivH, sefA, sopE, and spvC. The S. Enteritidis and untyped Salmonella isolates harbored all virulence genes while S. Typhimurium isolates carried six virulence genes, except sefA and spvC. Phenotypic resistance revealed decreased susceptibility to ciprofloxacin, streptomycin, ampicillin, tetracycline, gentamicin, sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim, amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, and azithromycin. Genotypic resistance showed a higher prevalence of plasmid-mediated blaTEM followed by tetA, sul1, sul2, sul3, and strA/B genes. The phenotypic and genotypic resistance profiles of the isolates showed a harmonic and symmetrical trend. According to the findings, MDR and virulent NTS enterica serovars predominate in wet market conditions and can easily enter the human food chain. The chi-square analysis showed significantly higher associations among the phenotypic resistance, genotypic resistance and virulence genes in CDW, CBS, and KS respectively (p < 0.05).

Introduction

Salmonella has been recognized as one of the common pathogens that cause gastroenteritis [1, 2] with significant morbidity, mortality, and economic loss [3, 4]. WHO reported 153 million cases of NTS enteric infections worldwide in 2010, of which 56,969 were dead along with 50% were foodborne [5]. The disease surveillance report of China from 2006 to 2010 identified Salmonella as the second foodborne outbreak [6]. NTS serovars like Typhimurium and Enteritidis are the predominant worldwide among the 2,600 serotypes of Salmonella that have been identified [7, 8]. Poultry has been regarded as the single prime cause of human salmonellosis and avian salmonellosis is not only affects the poultry industry but also can infect humans and caused by the consumption of contaminated poultry meat and eggs [9]. The eggs are considered to be the primary cause of salmonellosis and numerous other foodborne outbreaks [10–13]. Generally, Salmonella grows in animal farms may contaminate eggs and/or meat during the slaughtering process before being transferred to humans through the food chain. Indeed, numerous previous studies have been reported the isolation of Salmonella from foods of animal origin as well as human samples [14–17]. Human S. Enteritidis are generally linked with the consumption of contaminated eggs and poultry meat, while S. Typhimurium with the consumption of pork, poultry, and beef [18, 19]. Different prevalence of Salmonella enterica serovars has been reported around the globe from animal products and by-products [18, 20, 21]. Salmonella Typhimurium and Enteritidis are the most frequently reported serovars associated with human foodborne illnesses [22]. Untyped Salmonella of animal origin has been increasingly observed in Bangladesh [23, 24] but limited information has been published on Salmonella enterica serovars isolated from chicken processing environments.

Widespread uses of antimicrobials in poultry farming generate benefits for producers but aggravate the emergence of AMR bacteria [25]. Microorganisms that develop AMR are sometimes referred to as superbugs and open the door to treatment failure for even the most common pathogens, raise health care costs, and increases the severity and duration of infections. AMR burden may kill 300 million people during the next 35 years with a terrible impact on the global economy declining GDP by 2–3% in 2050 [26]. WHO recognized AMR as a serious threat, is no longer a forecast for the future, which is happening around the world and affects everybody regardless of age, sex, and nation [27]. Misuse and overuse of existing antimicrobials in humans, animals, and plants are accelerating the development and spread of AMR [28]. Antimicrobials are used in Bangladesh as the therapeutic, preventive, and growth promoters in the poultry production system [29]. The problem of AMR Salmonella emerged global concern in the modern decade [24, 30]. MDR Salmonella of poultry origin has been increasing in Bangladesh [31, 32].

Usually, the virulence factors promote the pathogenicity of Salmonella infection. Chromosomal and plasmid-mediated virulence factors are associated with the pathogenicity of Salmonella. Salmonella possesses major virulence genes such as invA, agfA, IpfA, hilA, sivH, sefA, and sopE. The infectivity of Salmonella strains is related with different virulence genes existent in the chromosomal Salmonella pathogenicity islands (SPIs) [33]. The attack qualities invA, hilA, and sivH code with a protein within the inward chromosomal membrane of Salmonella that’s essential for the intrusion to epithelial cells [34]. Moreover, Salmonella effector protein attached by sopE gene which have potential to Salmonella virulence [35]. The plasmid-mediated spvC gene is liable for vertical transmission of Salmonella [36]. The long polar fimbria (Ipf operon) make the fascination of the organisms for Peyer’s patches and attachment to intestinal M cells [37]. The aggregative fimbria (agf operon) advances the essential interaction of the Salmonella with the digestive system of the host and invigorate microbial self-aggregation for higher rates of survival [38]. The Salmonella-encoded fimbria (sef operon) supports interaction between the organisms and the macrophages [38]. In spite of the fact that was a paucity of information in the determination of virulence gene from Salmonella enterica serovars in Bangladesh but recently eight virulence genes were found in Salmonella isolates of poultry origin in Bangladesh [32].

Wet markets are very common in Bangladesh which are commonly dirty, chaotic, and unhygienic and floors are constantly sprayed with water for washing and to conserve the humidity [39]. Dressing and processing of poultry in the open environment are common practices in the traditional wet markets. The chicken vendors himself dressing the chicken without having personal protective devices, without using clean dressing utensils such as chopping boards and knives. Even the same water is used frequently for washing or cleaning the whole dressed carcass. There is a great possibility of cross-contamination and horizontal distribution of MDR Salmonella in the environment of wet markets [40]. The whole chicken carcass, vendor, and the consumer may be infected with Salmonella due to poor sanitary and hygienic practices. Even there is a great scope to spread and transmission of Salmonella enterica serovars in the agricultural food chain in the wet markets since most of the products are sold at room temperature and exposed to the environment [41]. A previous study stated that the incidence of Salmonella at different sites of wet markets has indicated a cause of cross-contamination in the meat during sale through food or equipment contact surfaces [39]. Based on the importance of foodborne Salmonella at wet markets, this study aimed at determining the pathogenicity and profile of antimicrobial susceptibility of Salmonella enterica serovars isolated from poultry processing environments in the wet markets of Dhaka, Bangladesh.

Materials and methods

Study design and sample collection

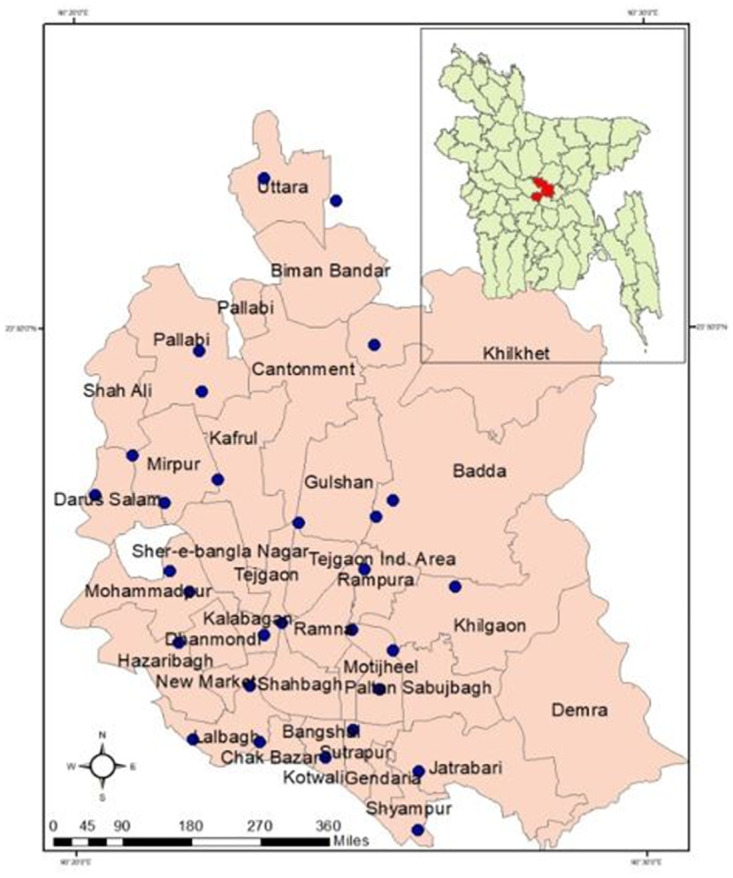

The study was conducted in the 29 chicken wet markets around Dhaka city, the capital of Bangladesh from February to December 2019 in a cross-section manner (Fig 1). Dhaka city is called the biggest chicken selling hub due to the mass population density and economic sovereignty of the population. The sample size was calculated by using the “sample size calculator for prevalence studies, version 1.0.01” based on the 25% prevalence of Salmonella spp. reported previously in Bangladesh [42, 43]. The desired individual sample number should not be less than 289. Three types of poultry processing environmental samples consisting of carcass dressing water (CDW), chopping board swabs (CBS), and knife swabs (KS) were collected independently as the number of 290. The ten samples of each three types (CDW, CBS and KS) were collected from each site on a single visit. The sterile cotton swabs contained in 10 ml buffered peptone water (BPW) were used for swabbing the samples. The samples were collected aseptically and immediately brought to the Antimicrobial Resistance Action Centre (ARAC) with an insulated icebox. This study received ethical approval from the Ethical Committee of the Animal Health Research Division at the Bangladesh Livestock Research Institute (BLRI), Dhaka, Bangladesh (ARAC: 15/10/2019:05).

Fig 1. Map of the Dhaka city with study locations (blue colored circles) of 29 wet markets.

Salmonella isolation and identification

Salmonella isolation and identification was carried out according to the guidelines of ISO [44] as follows; pre-enrichment of the swab smear in BPW (Oxoid, UK) followed by aerobic incubation at 37°C for 18–24 h. Further, 0.1 mL of the pre-enriched sample was positioned discretely into three different locations on Modified Semisolid Rappaport Vassiliadis (MSRV; Oxoid, UK) agar and incubated at 41.5°C for 20–24 h. Further, a single loop of MSRV cultured medium was taken and subsequently smeared onto Xylose Lysine Deoxycholate (XLD; Oxoid, UK) and MacConkey agar (Oxoid, UK) medium and overnight incubated at 37°C. The typical black centered colony with a reddish zone on XLD and a colorless colony on MacConkey were extracted and subsequently sub cultured in nutrient agar (NA; Oxoid, UK) medium. The biochemical conformation was done by triple sugar iron (TSI), motility indole urea (MIU), catalase and oxidase tests. Final confirmation was done by the mechanical Vitek-2 compact analyzer (bioMérieux, France) as well as molecular detection by the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) method [32].

DNA extraction

The conventional boiling method was used for the extraction of DNA followed by a proven procedure as applied earlier [32, 45, 46]. Concisely, the pure Salmonella isolate was cultured on nutrient agar medium and subsequently overnight incubated at 37°C. A few fresh and juvenile colonies were harvested from overnight culture and suspended in nuclease-free water. Then the bacterial suspension was boiled at 99°C for 15 min followed by chilled on ice for a short duration. Lastly, the debris was separated by high speed centrifugation and the supernatant was taken as the DNA template for further PCR assay.

PCR detection of Salmonella and Salmonella enterica serovars

Uniplex PCR (U-1) was performed to detect Salmonella species targeting virulence gene invA [47]. Multiplex PCR (M-I) was done to detect S. Typhimurium and S. Enteritidis [48, 49]. PCR reaction was adjusted in 25 μL mixture containing 2 μL of DNA template, 12.5 μL of 2x master mix (Go Taq Green Master Mix, Promega), 0.5 μL each of forward and reverse primers (10 pmol/μL) and 9.5 μL nuclease-free water. The PCR products were run at 100 V with 500 mA for 30 min in 1.5% agarose gel containing ethidium bromide. A 100bp DNA ladder (Thermo Scientific, USA) was used as a size marker. The primers used to detect Salmonella and Salmonella enterica serovars are presented in Table 1. The ATCC of S. Typhimurium (ATCC-14028) and S. Enteritidis (ATCC-13076) were used as a positive control. Consequently, PCR positive Salmonella serovars Typhimurium and Enteritidis was further reconfirmed by the Vitek-2 compact analyzer (bioMérieux, France).

Table 1. Primers used to detect Salmonella enterica serovars and resistance genes.

| PCR | Target gene | Sequence | Amplicon size (bp) | Thermal Profile | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| U-1 | invA | F-GTGAAATTATCGCCACGTTCGGGCAA | 284 | 95°C for 1 min; 38 cycles of 95°C for 30s, 64°C for 30s and 72°C for 30s; elongation step at 72°C for 4 min | [58] |

| R-TCATCGCACCGTCAAAGGAACC | |||||

| M-1 | Typh | F-TTGTTCACTTTTTACCCCTGAA | 401 | 95°C for 2 min; 30 cycles of 95°C for 1 min, 57°C for 1 min and 72°C for 2 min; elongation at 72°C for 5 min | [49] |

| R-CCCTGACAGCCG TTAGATATT | |||||

| sdf-1 | F-TGTGTTTTATCTGATGCAAGAGG | 293 | [48] | ||

| R-CGTTCTTCTGGTACTTACGATGAC | |||||

| M-II | blaTEM | F-CCGTTCATCCATAGTTGCCTGAC | 800 | 94°C for 10 min; 30 cycles of 94°C for 40 s, 60°C for 40 s and 72°C for 1 min; elongation step at 72°C for 7 min | [56] |

| R-TTTCCGTGTCGCCCTTATTC | |||||

| blaSHV | F-AGCCGCTTGAGCAAATTAAAC | 713 | [56] | ||

| R-ATCCCGCAGATAAATCACCAC | |||||

| blaOXA | F-GGCACCAGATTCAACTTTCAAG | 564 | [56] | ||

| R-GACCCCAAGTTTCCTGTAAGTG | |||||

| M-III | blaCTX-M-1 | F-TTAGGAARTGTGCCGCTGYA | 688 | 94°C for 10 min; 30 cycles of 94°C for 40 s, 60°C for 40 s and 72°C for 1 min; elongation step at 72°C for 7 min | [56] |

| R-CGATATCGTTGGTGGTRCCAT | |||||

| blaCTX-M-2 | F-CGTTAACGGCACGATGAC | 404 | [56] | ||

| R-CGATATCGTTGGTGGTRCCAT | |||||

| blaCTX-M-9 | F-TCAAGCCTGCCGATCTGGT | 561 | [56] | ||

| R-TGATTCTCGCCGCTGAAG | |||||

| blaCTX-Mg8/25 | F-AACRCRCAGACGCTCTAC | 326 | [56] | ||

| R-TCGAGCCGGAASGTGTYAT | |||||

| M-IV | sul1 | F-CGG CGT GGG CTA CCT GAA CG | 433 | 95°C for 15 min; 30 cycles of 95°C for 1 min, 66°C for 1 min and 72°C for 1 min; elongation step at 72°C for 10 min | [57] |

| R-GCC GAT CGC GTG AAG TTC CG | |||||

| sul2 | F-CGG CGT GGG CTA CCT GAA CG | 721 | [57] | ||

| R-GCC GAT CGC GTG AAG TTC CG | |||||

| sul3 | F-CAACGGAAGTGG GCGTTG TGGA | 244 | [57] | ||

| R-GCT GCA CCA ATT CGC TGAACG | |||||

| M-V | tet(A) | F-GGC GGTCTT CTT CAT CATGC | 502 | 94°C for 15 min; 30 cycles of 94°C for 1 min, 63°C for 1 min and 72°C for 1 min; elongation step at 72°C for 10 min | [57] |

| R-CGG CAG GCA GAG CAA GTAGA | |||||

| tet(B) | F-CGC CCA GTG CTG TTG TTGTC | 173 | [57] | ||

| R-CGC GTT GAG AAG CTG AGG TG | |||||

| tet(C) | F-GCT GTAGGCATAGGCTTGGT | 888 | [57] | ||

| R-GCC GGA AGC GAG AAGAATCA | |||||

| strA/strB | F-ATGGTGGACCCTAAAACTCT | 893 | [57] | ||

| R-CGTCTAGGATCGAGACAAAG |

Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (AST)

The Kirby-Bauer disc diffusion method was used to determine the AMR profile of all isolates, according to the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute’s standards [50]. A panel of 16 antimicrobials representing 10 different classes were selected for AST consisting of aminoglycosides: amikacin (AK, 30μg), gentamicin (CN, 10μg), streptomycin (S, 10μg); carbapenem: meropenem (MEM, 10μg); cephalosporin/beta-lactam antibiotics: ceftriaxone (CRO, 30μg), cefotaxime (CT, 10μg), ceftazidime (CAZ, 30μg), aztreonam (ATM, 30μg); beta-lactamase inhibitors: amoxicillin–clavulanate (AMC, 30μg); penicillins: ampicillin (AMP, 10μg); macrolides: azithromycin (AZM, 15μg); quinolones/fluoroquinolones: ciprofloxacin (CIP, 5μg), nalidixic acid (NA, 30μg); folate pathway inhibitors: sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim (SXT, 25μg); tetracycline: tetracycline (TE, 10μg); phenicols: chloramphenicol (C, 30μg). The isolates which were resistant to three or more classes of antibiotics were regarded as MDR [51]. The intermediate isolates were considered resistant as the acquisition and transition from susceptible to resistance had already begun [52]. The positive control was used as Escherichia coli ATCC 25922. The multiple antibiotic resistance (MAR) index was calculated and interpreted using a proven method [53, 54].

MAR index calculation

Multiple Antibiotic Resistance (MAR) indexing has been considered as the cost effective and valid method for source tracking of a bacteria. MAR index is calculated as the ratio of number of resistant antibiotics to which organism is resistant to total number of antibiotics to which organism is exposed [55]. MAR index values larger than 0.2 indicate the organism is highly resistant where antibiotics are often used.

PCR detection of AMR genes

The phenotypically resistant Salmonella isolates were screened by PCR for the detection of 14 antibiotic resistance genes, comprising of 7 β-lactamase genes (blaTEM, blaSHV, blaOXA, blaCTX-M-1, blaCTX-M-2, blaCTX-M-9 and blaCTX-Mg8/25), 3 tetracycline resistant genes (tetA, tetB and tetC), 3 sulfonamide resistant genes (sul1, sul2 and sul3) and single streptomycin resistant gene (strA/B). For β-lactam gene, two cycles of multiplex PCR (M-II & M-III) were carried out following the proven method of Dallenne et al. [56]. Consecutively, two cycles of multiplex PCR (M-IV & M-V) were performed to detect the resistance genes for sulfonamide, tetracycline and streptomycin in consistent with the established method [57]. PCR reaction mixture, as well as gel electrophoresis was done in alignment with the procedures applied for the detection of Salmonella enterica serovars in this study. The primers used to detect resistance genes are presented in Table 1.

PCR detection of virulence genes in Salmonella isolates

All Salmonella isolates were screened for the determination of eight important virulent genes encoding invA, agfA, IpfA, hilA, sivH, sefA, sopE and spvC. The PCR was executed in single reactions following previously used specific primers and thermal profiles [37, 59–64]. PCR reaction mixture, as well as gel electrophoresis was done in alignment with the procedures applied for the detection of Salmonella enterica serovars in this study. The reference positive control (S. Typhimurium ATCC 14028 and S. Enteritidis ATCC 13076) and negative control (E. coli ATCC 25922) were used for validation. The primers used in this study are presented in Table 2.

Table 2. Primers used to detect virulence gene in Salmonella isolates.

| PCR | Target Gene | Sequence | Amplicon size (bp) | Thermal Profile | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P-1 | agfA | F-TCCACAATGGGGCGGCGGCG | 350 | 94°C for 1 sec; 58°C for 1 sec; 74°C 21 sec | [59] |

| R-CCTGACGCACCATTACGCTG | |||||

| P-2 | IpfA | F-CTTTCGCTGCTGAATCTGGT | 250 | 94°C for 1 sec; 55°C for 1 sec; 74°C 21 sec | [37] |

| R-CAGTGTTAACAGAAACCAGT | |||||

| P-3 | hilA | F-CTGCCGCAGTGTTAAGGATA | 497 | 94°C for 120 sec; 62°C for 1 min; 72°C 1 min | [60] |

| R-CTGTCGCCTTAATCGCATGT | |||||

| P-4 | sivH | F-GTATGCGAACAAGCGTAACAC | 763 | 94°C for 30 sec; 56°C for 45 sec; 72°C 45 sec | [61] |

| R-CAGAATGCGAATCCTTCGCAC | |||||

| P-5 | sefA | F-GATACTGCTGAACGTAGAAGG | 488 | 94°C for 1 sec; 56°C for 1 sec; 74°C 21 sec | [62] |

| R-GCGTAAATCAGCATCTGCAGTAGC | |||||

| P-6 | sopE | F-GGATGCCTTCTGATGTTGACTGG | 398 | 94°C for 1 min; 55°C for 1 min; 72°C for 1 min | [63] |

| R-ACACACTTTCACCGAGGAAGCG | |||||

| P-7 | spvC | F-CCCAAACCCATACTTACTCTG | 669 | 93°C for 1 min; 42°C for 1 min; 72°C for 2 min | [64] |

| R-CGGAAATACCATCTACAAATA |

Statistical analysis

The antimicrobial susceptibility data was presented in Excel sheets (MS-2016) and analyzed with SPSS software (SPSS-24.0). The prevalence was calculated using descriptive analysis and the Chi-square test was applied to determine the level of significance. Statistical significance was determined by a p-value less than 0.05 (p <0.05).

Results

Prevalence of NTS enterica serovars

Of all 870 samples, 165 (18.96%) were positive for Salmonella. The prevalence of Salmonella was found 20% (58 in 290) in CDW, 19.31% (56 in 290) in CBS, and 17.58% (51 in 290) in KS. Meanwhile, the MDR Salmonella was found to be 72.41% (42 in 58), 73.21% (41 in 56), and 68.62% (35 in 51) in CDW, CBS, and KS, respectively. The overall prevalence of S. Typhimurium, S. Enteritidis, and untyped Salmonella was found to be 8.96%, 1.6%, and 8.38%, respectively along with an overall MDR of 71.41%. The prevalence of NTS Typhimurium, Enteritidis and untyped Salmonella were found to be 7.93% (23 in 290), 1.72% (5 in 290), and 10.34% (30/290) in CDW, respectively. Likewise, the prevalence of NTS Typhimurium, Enteritidis, and untyped Salmonella was found to be 10.34% (30 in 290), 2.06% (6 in 290), and 6.89% (20/290) in CBS, respectively. Similarly, the prevalence of NTS Typhimurium, Enteritidis, and untyped Salmonella was represented 8.62% (25 in 290), 1.03% (3 in 290), and 7.93% (23 in 290) in KS, correspondingly.

Phenotypic resistance patterns of NTS isolates

AST result in CDW revealed the highest resistance to ciprofloxacin (68.95%) followed by nalidixic acid (62.06%), tetracycline (60.33%), ampicillin, (58.61%) and streptomycin (56.88%); moderate resistance to gentamicin (39.64%), amoxicillin-clavulanate (31.92%), sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim, (27.58%) and chloramphenicol (20.67%). On the contrary, low resistance was observed to azithromycin, amikacin and meropenem, respectively. Third-generation cephalosporins (ceftriaxone, cefotaxime, ceftazidime, and aztreonam) were found almost sensitive to all Salmonella isolates recovered from CDW (Table 3). Consecutively, AST result of CBS showed higher resistance to streptomycin (64.28%) followed by ciprofloxacin (62.49%), ampicillin (62.27%), tetracycline (60.7%), nalidixic acid (53.56%), and gentamicin (53.56%); moderate resistance (14.27%-46.41%) was recorded for sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim, amoxicillin-clavulanate, chloramphenicol, and azithromycin. Besides, complete sensitivity was found in all third-generation cephalosporins, including carbapenem (ceftriaxone, cefotaxime, ceftazidime, aztreonam, and meropenem) (Table 4). Successively, AST result of KS exhibited higher resistance to ciprofloxacin (64.69%), ampicillin (64.69%), streptomycin (64.7%), nalidixic acid (58.81%), and tetracycline (54.89%); moderate resistance was recorded to gentamicin (47.05%), sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim (47.05%), amoxicillin-clavulanate (27.44%) and chloramphenicol (21.56%). On the contrary, very low resistance or almost sensitivity were observed to azithromycin, amikacin, meropenem, and third-generation cephalosporins (ceftriaxone, cefotaxime, ceftazidime, and aztreonam) (Table 5). There was harmony and synergy among the phenotypic resistance patterns of CDW, CBS, and KS. The AST pattern of ciprofloxacin in CDW was significantly higher compared to CBS (p < 0.05). Similarly, the AST pattern of gentamicin in CBS was significantly higher compared to CDW and KS (p < 0.05). A statistical association of phenotypic resistance patterns was found among the carcass treatment water, cutting board swabs, and knife swabs (p<0.05). The details of phenotypic and genotypic antimicrobial resistance data of Salmonella sevovars are presented in S1 Text.

Table 3. Phenotypic resistance pattern of NTS enterica serovars in carcass dressing water (CDW).

| Serovar | Antimicrobial Resistance (%) | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CIP | S | AMP | TE | NA | CN | SXT | AMC | C | AZM | AK | MEM | ATM | CRO | CT | CAZ | |

| S. Typhimurium | 34.49 | 27.58 | 31.04 | 34.48 | 29.31 | 27.59 | 5.17 | 18.97 | 6.89 | 3.45 | 0 | 1.72 | 0 | 0 | 3.45 | 0 |

| S. Enteritidis | 6.89 | 3.44 | 5.17 | 3.44 | 5.17 | 3.44 | 5.17 | 3.44 | 1.72 | 0 | 1.72 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Untyped Salmonella | 27.58 | 25.89 | 22.41 | 22.42 | 27.58 | 8.62 | 17.24 | 8.62 | 12.07 | 3.44 | 1.72 | 1.72 | 0 | 0 | 3.44 | 0 |

| Overall Resistance | 68.96 | 56.9 | 58.62 | 60.34 | 62.06 | 39.65 | 27.58 | 31.03 | 20.68 | 6.89 | 3.44 | 3.44 | 0 | 0 | 6.89 | 0 |

Table 4. Phenotypic resistance pattern of NTS enterica serovars in chopping board swab (CBS).

| Serovar | Antimicrobial Resistance (%) | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CIP | S | AMP | TE | NA | CN | SXT | AMC | C | AZM | AK | MEM | ATM | CRO | CT | CAZ | |

| S. Typhimurium | 39.28 | 41.07 | 42.85 | 42.86 | 41.07 | 39.29 | 23.21 | 23.22 | 10.72 | 10.72 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| S. Enteritidis | 7.15 | 7.14 | 5.35 | 5.35 | 7.14 | 1.78 | 5.36 | 1.78 | 0 | 1.78 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Untyped Salmonella | 16.07 | 16.07 | 19.65 | 12.5 | 5.36 | 12.5 | 17.85 | 10.71 | 8.92 | 1.78 | 1.78 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Overall Resistance | 62.5 | 64.28 | 67.85 | 60.71 | 53.57 | 46.42 | 46.42 | 35.71 | 19.64 | 14.28 | 1.78 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Table 5. Phenotypic resistance pattern of NTS enterica serovars in knife swab (KS).

| Serovar | Antimicrobial Resistance (%) | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CIP | S | AMP | TE | NA | CN | SXT | AMC | C | AZM | AK | MEM | ATM | CRO | CT | CAZ | |

| S. Typhimurium | 43.14 | 35.29 | 41.17 | 41.17 | 41.18 | 37.25 | 31.37 | 21.57 | 15.68 | 5.88 | 0 | 1.96 | 0 | 0 | 1.96 | 0 |

| S. Enteritidis | 0 | 1.96 | 3.93 | 3.92 | 5.88 | 0 | 1.96 | 1.96 | 1.96 | 0 | 1.96 | 1.96 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Untyped Salmonella | 21.56 | 27.45 | 19.6 | 9.8 | 11.76 | 9.8 | 13.72 | 3.92 | 3.92 | 1.96 | 1.96 | 1.96 | 5.88 | 3.92 | 5.88 | 5.88 |

| Overall Resistance | 64.7 | 64.7 | 64.7 | 54.9 | 58.82 | 47.05 | 47.05 | 27.45 | 21.56 | 7.84 | 3.92 | 5.88 | 5.88 | 3.92 | 7.84 | 5.88 |

MAR index patterns of NTS isolates

The large phenotypic resistance pattern in CDW was found CIP-S-AMP-TE-NA-CN-AMC-SXT-CT-MEM while most one was CIP-S-AMP-TE-NA-CN-AMC. Similarly, the large phenotypic resistance pattern in CBS was found CIP-S-AMP-TE-NA-CN-AMC-AZM-SXT while the most one was CIP-S- CIP-S-AMP-TE-NA-CN-AMC. Likewise, the large phenotypic resistance pattern in KS was found CIP-S-AMP-TE-NA-AMC-SXT-CT-CAZ-CRO-ATM while the most common one was CIP-S-AMP-TE-NA-CN-AMC-C. The overall MAR index of more than 0.2 was found in 50%, 50%, 64.7% isolates of CDW, CBS and KS respectively. Besides, the highest MAR index value of 0.68, 0.62, and 0.56 was recorded in KS, CDW, and CBS, respectively. The complete sensitive isolates were identified at 1.39% (4 in 290), 2.06% (6 in 290), and 1.03% (3 in 290) in the CDW, CBS, and KS, respectively. The AMR patterns and MAR index of Salmonella enterica serovars are shown in S2 Text.

Genotypic resistance patterns of NTS isolates

All phenotypically resistant Salmonella isolates were screened by PCR for the detection of 14 antibiotic resistant genes encompassing 7 β-lactamase genes (blaTEM, blaSHV, blaOXA, blaCTX-M-1, blaCTX-M-2, blaCTX-M-9 and blaCTX-Mg8/25), 3 tetracycline resistant genes (tetA, tetB and tetC), 3 sulfonamide resistant genes (sul1, sul2, and sul3) and single streptomycin resistant gene (strA/B) recovered from CDW (Table 6), CBS (Table 7) and KS (Table 8).

Table 6. Genotypic resistance pattern of NTS enterica serovars in carcass dressing water.

| Serovar | Genotypic resistance (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| blaTEM | TetA | Sul1 | StrA/B | |

| S. Typhimurium | 39.65 | 36.2 | 34.48 | 13.79 |

| S. Enteritidis | 8.62 | 3.44 | 3.44 | 3.44 |

| Untyped Salmonella | 13.79 | 20.68 | 22.41 | 18.96 |

| Overall resistance | 62.06 | 60.32 | 60.33 | 36.20 |

Table 7. Genotypic resistance pattern of NTS enterica serovars in chopping board swab.

| Serovar | Genotypic resistance (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| blaTEM | TetA | Sul1 | Sul2 | Sul3 | StrA/B | |

| S. Typhimurium | 42.85 | 41.07 | 42.85 | 1.78 | 1.78 | 14.28 |

| S. Enteritidis | 5.35 | 5.35 | 5.35 | 0 | 0 | 3.57 |

| Untyped Salmonella | 21.42 | 12.5 | 21.42 | 1.78 | 1.78 | 7.14 |

| Overall resistance | 69.62 | 58.92 | 69.62 | 3.56 | 3.56 | 24.99 |

Table 8. Genotypic resistance pattern of NTS enterica serovars in knife swab.

| Serovar | Genotypic resistance (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| blaTEM | TetA | Sul1 | Sul3 | StrA/B | |

| S. Typhimurium | 43.13 | 41.17 | 37.25 | 9.8 | 15.68 |

| S. Enteritidis | 3.92 | 3.92 | 1.96 | 0 | 0 |

| Untyped Salmonella | 15.68 | 13.72 | 9.8 | 7.84 | 15.68 |

| Overall resistance | 62.73 | 58.81 | 49.01 | 17.62 | 31.36 |

Out of seven, only one ESBL gene, blaTEM was detected with a prevalence rate of 62.06%, 69.62%, and 62.73% in CDW, CBS, and KS, respectively. Consecutively, out of three tetracycline resistant genes, only one tetA was identified with a prevalence level of 60.32%, 58.92%, and 58.81% in CDW, CBS, and KS, respectively. Sequentially, the prevalence of the sul1 gene was found 60.33%, 69.62%, and 49.01% in CDW, CBS, and KS, respectively. Furthermore, sul2 and sul3 were found in CBS with lower prevalence rate of 3.56% and 3.56%, respectively. Similarly, the sul3 gene was detected in KS with a prevalence rate of 17.62%. Moreover, the streptomycin resistance gene, strA/B was detected with a prevalence rate of 36.2%, 24.99%, and 31.36% in CDW, CBS, and KS, respectively. The detailed genotypic susceptibility pattern, including Salmonella enterica serovars and untyped Salmonella from three different sources, is presented in tabular form (Tables 6–8). The sul1gene in CBS was significantly higher compared to CDW and KS (p < 0.05). Similarly, the strA/B gene in CDW was significantly higher compared to KS and CBS (p < 0.05). A statistical association of genotypic resistance patterns was found among the carcass treatment water, cutting board swabs, and knife swabs (p<0.05).

PCR detection of virulence genes for NTS isolates

All Salmonella isolates were screened by PCR to monitor eight common virulence genes namely invA, agfA, IpfA, hilA, sivH, sefA, sopE, and spvC. S. Enteritidis and untyped Salmonella isolates were found positive for all eight common virulence genes whereas S. Typhimurium harbored six virulence genes (Table 9). The analysis showed significantly higher associations among the virulence genes in CDW, CBS, and KS respectively (p < 0.05). The detail statistical analysis is given in S3 Text.

Table 9. Virulence genes distribution among the Salmonella enterica serovars.

| Prevalence of virulence genes (%) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Samples | Serovar | InvA | AgfA | IpfA | HilA | SivH | SopE | SefA | SpvC |

| CDW | S. Typhimurium | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| S. Enteritidis | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | |

| Untyped Salmonella | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | |

| CBS | S. Typhimurium | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| S. Enteritidis | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | |

| Untyped Salmonella | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | |

| KS | S. Typhimurium | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| S. Enteritidis | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | |

| Untyped Salmonella | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | |

Discussion

NTS enterica serovars isolated from chicken processing environments at wet markets in Bangladesh have only been reported in a few investigations. In our research, we discovered an overall prevalence of Salmonella 18.96% in poultry processing environmental samples such as CDW, CBS, and KS. Previously, in Bangladesh the prevalence of Salmonella was found to be present 23.33% in poultry slaughter specimens [23]; 26.6% in chicken cloacal swab, intestinal fluid, egg surface, hand wash, and soil of chicken market samples [65]; 25.35% in the chicken cloacal swab, eggshells, intestinal contents, liver swabs, broiler meat, and swabs of slaughterhouse [66]; 35% in broiler farms settings [31]; 23.53% in poultry samples [67]; 37.9% in poultry production settings [68]; 31.25% in broiler farm settings [69]; 42% in broiler chicken [70] and 65% in frozen chicken meat [71]. The prevalence of Salmonella was found to be 8.62% in broiler, 6.89% in sonali and 3.1% in native chicken cecal contents according to Siddiky et al. [32]. The prevalence of Salmonella isolates in our findings was consistent with earlier findings of Bangladesh.

In Ethiopian butcher shops, the overall prevalence of Salmonella was determined to be 17.3%. Salmonella was found in KS, CBS, hand washings, and meat, which is consistent with our findings [72]. The study based on the wet market conducted in India revealed the prevalence of Salmonella of 14.83% in the chicken meat shops [73]; 19.04% in retail chicken stores [74]; and 23.7% in white and red meat in local markets [75]. A study demonstrated the high prevalence of Salmonella (88.46%) in poultry processing and environmental samples obtained from wet markets and small-scale processing plants in Malaysia [39]. Salmonella was found 35.5% and 50% in broiler carcasses at wet markets and processing plants, respectively, according to Rusul et al. [76]. Furthermore, in Penang, Malaysia, the overall incidence of Salmonella serovars was found to be 23.5% in ducks, duck raising, and duck processing environments [53]. Furthermore, our findings were connected to the recent frequency of Salmonella both at home and abroad. In our investigation, the prevalence of NTS Typhimurium was determined to be 7.93%, 10.34%, and 8.62% in CDW, CBS, and KS, respectively. Similarly, it was noted that the occurrence of S. Enteritidis was 1.72%, 2.06%, and 1.03% in CDW, CBS, and KS respectively. Siddiky et al. [32] found the overall prevalence of S. Typhimurium and S. Enteritidis at the rate of 3.67% and 0.57% in chicken cecal contents. There was a link between the prevalence of Salmonella enterica serovars in caecal content and environmental samples. Thung et al. [77] found S. Enteritidis and S. Typhimurium in raw chicken meat at retail markets in Malaysia, with prevalence rates of 6.7% and 2.5%, respectively. The major Salmonella enterica serovars in our investigation was S. Typhimurium, which was similar with the findings of McCrea et al. [78], who identified S. Typhimurium as the major Salmonella serovars from a California poultry market. According to Saitanu et al. [79], S. Typhimurium (5.5%) was the most common serotype in duck eggs in Thailand. The studies conducted in Bangladesh, S. Typhimurium was found to be 15.91% in broiler production systems [80]; 85% in broiler farm samples [31] and 5% in commercial layer farm settings [81]. S. Typhimurium was found to be more common in our study, which corresponds to findings both at home and overseas. Consecutively, S. Typhimurium and S. Enteritidis were isolated from raw chicken meat at retail markets in Malaysia [77]; higher prevalence of S. Enteritidis (21.9%) and S. Typhimurium (9.4%) were isolated from chicken in Turkey [82]; Salmonella enterica serovars were identified in backyard poultry flocks in India [83]; S. Enteritidis and S. Typhimurium recovered from chicken meat in Egypt [84]. Suresh et al. [22] recovered S. Typhimurium and S. Enteritidis in large proportions from various poultry products in India, compared to other serovars. Furthermore, China and some European countries detected S. Enteritidis and S. Typhimurium from catering points and meat of pork, chicken and duck as the most prevalent serotypes [85, 86].

In our study, NTS enterica serovars Typhimurium and Enteritidis along with untyped Salmonella was found higher resistance to ciprofloxacin, streptomycin, gentamicin, ampicillin, tetracycline, and nalidixic acid; moderate resistance to sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim, amoxicillin-clavulanate, chloramphenicol, and azithromycin. Alam et al. [31] found a high percentage of Salmonella resistance to tetracycline, ampicillin, streptomycin, and chloramphenicol (77.1% to 97.1%). Furthermore, according to Parvin et al. [71], Salmonella has the highest resistance to oxytetracycline (100%), followed by trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (89.2%), tetracycline (86.5%), nalidixic acid (83.8%), amoxicillin (74.3%), and pefloxacin (74.3%). Mridha et al. [69] shown higher to moderate resistance of the isolates of Salmonella to erythromycin, tetracycline, amoxicillin, and azithromycin. Sequentially, Sobur et al. [87] found higher resistance of Salmonella to tetracycline, ciprofloxacin, and ampicillin. Salmonella isolated from the feces of chickens, ducks, geese, and pigs has been reported to be resistant to nalidixic acid (48.8%), tetracycline (46.9%), ampicillin (43.2%), streptomycin (38.3%), and trimethoprim/ sulfamethoxazole (33.3%), respectively [88–90]. It was found that Salmonella was highly resistant to ciprofloxacin (77%), sulfisoxazole (73%) and ampicillin (55.6%) in chicken hatcheries in China [91]; highly resistance to tetracycline and ampicillin in wet markets, Thailand [41]; higher resistance to nalidixic acid (99.5%), ampicillin (87.8%), tetracycline (51.9%), ciprofloxacin (48.7%), and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (48.1%) in broiler chickens along the slaughtering process in China [92]. S. enterica serovar Typhimurium was found to be resistance to ampicillin, tetracycline, and sulphamethoxazole isolated from chicken farms in Egypt [93]. The NTS enterica serovars was found to be higher resistance to ampicillin (95.71%), ciprofloxacin (82.86%), tetracycline (100%), and nalidixic acid (98.57%) in retail chicken meat stores in northern India [73]. Siddiky et al. [32] found that S. Typhimurium had the highest resistance to ciprofloxacin (100%) and streptomycin (100%) followed by tetracycline (86.66%), nalidixic acid (86.66%), gentamicin (86.66%), ampicillin (66.66%), and amoxicillin–clavulanate (40%) in in broiler chickens. Furthermore, Siddiky et al. [32] reported the highest resistance pattern of S. Typhimurium to ciprofloxacin (100%) and streptomycin (100%) followed by tetracycline (86.66%), nalidixic acid (86.66%), gentamicin (86.66%), ampicillin (66.66%) and amoxicillin–clavulanate (40%) in broiler chicken. Similarly, Siddiky et al. [32] identified the maximum resistance of the S. Enteritidis to streptomycin (100%) followed by ciprofloxacin (80%), tetracycline (80%), gentamicin (80%), and moderate resistance to amikacin (20%), amoxicillin–clavulanate (20%), azithromycin ((20%), and sulphamethazaxole-trimethoprim (20%) in broiler chicken. There was a substantial correlation and congruence with phenotypic resistance patterns of Salmonella enterica serovars both at home and abroad.

According to Mishra et al. [94], MAR index of 0.2 or higher indicates high risk sources of contamination, MAR index of 0.4 or higher is associated with fecal source of contamination. Thenmozhi et al. [95], also states that MAR index values > 0.2 indicate existence of isolate from high risk contaminated source with frequency use of antibiotics while values ≤ 0.2 show bacteria from source with less antibiotics usage. High MAR indices mandate vigilant surveillance and remedial measures. In this study, the overall MAR index of more than 0.2 was found in 50%, 50%, and 64.7% isolates of CDW, CBS, and KS respectively. Besides, the highest MAR index value of 0.68, 0.62, and 0.56 was recorded in KS, CDW, and CBS respectively.

A single beta-lactam-resistant blaTEM gene was discovered in all three categories of samples with a different frequency rate in our analysis, out of seven. In CDW, CBS, and KS, the prevalence of blaTEM was found to be 62.06%, 69.62%, and 62.73%, respectively. Ahmed et al. [96] detected a higher prevalence of blaTEM mediated ESBL gene among Salmonella isolated from humans in Bangladesh. Yang et al. [97] identified blaTEM, a gene encoded for beta-lactamases resistance, in 51.6% resistant Salmonella isolates. According to Aslam et al. [98], the blaTEM gene was found in 17% of Salmonella isolates from retail meats in Canada. Lu et al. [99] detected only 81.2% blaTEM gene, while blaCTX-M could not be detected in any of the examined isolates. Similarly, Van et al. [100] found only the blaTEM gene in E. coli recovered from raw meat and shellfish in Vietnam. The emergence of blaTEM mediated ESBL producing NTS enterica serovars indicated the use of beta-lactam antibiotics in poultry farming practices. Siddiky et al. [32] detected only the blaTEM gene from chicken cecal contents and Xiang et al. [101] reported plasmid-borne and easily transferable blaOXA-1 and blaTEM-1 genes. Consecutively, Suresh et al. [102] detected blaTEM as the predominant gene in food of animal origin in India. The blaTEM gene’s results were consistent with and related to earlier findings. In our analysis, just one tetracycline resistance gene, tetA, was found in carcass dressing water, chopping board swab, and knife swab, with prevalence rates of 60.32%, 58.92%, and 58.81%, respectively. The sul1, sul2, and sul3 genes were also found in NTS enterica serovars, with sul1 being the most common. Similarly, the streptomycin resistance gene (strA/B) was found in NTS serovars with a high prevalence rate. Arkali and Çetinkaya [82] detected 58% positive sul1 gene from the Salmonella isolates of chickens in eastern Turkey. Consequently, Jahantigh et al. [103] detected the most prevalent tetA gene from broiler chickens in Iran. Successively, Vuthy et al. [90] discovered blaTEM, tetA and strA/B genes from the chicken food chain, while Sin et al. [104] isolated tetA and sul1 genes from chicken meat in Korea. Zhu et al. [92] isolated beta lactam (blaTEM), tetracycline resistant (tetA, tetB, tetC) and sulfonamide resistant (sul1, sul2 and sul3) genes with prevalence of 94.6%, 85.7%, and 97.8% in Salmonella isolated from the slaughtering process in China. El-Sharkawy et al. [93] who revealed blaTEM, tetA, tetC, sul1, and sul3 genes from S. Enteritidis isolates at a chicken farm in Egypt. Doosti et al. [105] detected strA/B (37.6%) from S. Typhimurium isolates at poultry carcasses in Iran. Sharma et al. [73] detected the most predominant tetA and blaTEM genes in NTS isolated from retail chicken shops in India. Continually, Alam et al. [31] revealed tetA (97.14%) and blaTEM-1 (82.85%) genes in broiler farms, whilst Siddiky et al. [32] detected tetA, sul1, and strA/B genes in chicken cecal content in Bangladesh. The genotypic resistance patterns were well matched with previous findings at home and abroad.

In our study, harmonic and proportioned correlations were existent between genotypic and phenotypic resistance decoration. These findings were in agreement and alignment with the observations of previous studies conducted across the globe [31, 32, 92]. However, sometimes the phenotypic and genotypic resistance pattern were not found to be similar. This may be due to source and concentration of the antibiotic disk, source of primers, concentration of inoculum, facilities of the laboratory and the capacity and skills of the laboratory personnel [32]. Previous research findings supported the disagreement between genotypic and phenotypic resistance patterns [100, 106].

In our study, MDR Salmonella embedded mostly with ciprofloxacin, streptomycin, tetracycline, ampicillin, gentamicin, and nalidixic acid, probably due to the common and frequent use of these antibiotics in poultry production settings in Bangladesh [29, 107]. CLSI [50] reported Salmonella has become naturally resistant to first and second-generation cephalosporins and aminoglycosides. The MDR along with higher resistance to ciprofloxacin is very alarming in human treatment as WHO recommended ciprofloxacin, a first-line drug treatment of intestinal infections. Besides, watch group ciprofloxacin had higher resistance and azithromycin had moderate resistance, reflects the severity of the resistance pattern of Salmonella serovars [108]. Furthermore, higher resistance to tetracycline indicated the massive use of therapeutic and growth enhancers in poultry production [109]. The emergence of blaTEM mediated ESBL producing Salmonella enterica serovars indicated the use of beta-lactam antibiotics in the poultry production cycle. Moreover, ESBL is usually encoded by large plasmids that are transferable from strain to strain and between bacterial species [96, 110].

Virulence gene analysis indicated S. Enteritidis and untyped Salmonella isolates carried eight virulence genes, including two types of Salmonella pathogenicity islands (SPI-1 and SPI-2) and many adhesion-related virulence genes. Virulence genes along with the MDR resistance pattern would accelerate the infectivity of Salmonella isolates [35]. The emergence of antibiotic resistance of Salmonella isolates depends on their genetic and pathogenicity mechanisms, which can enhance their survivability by preserving drug resistance genes [98]. The virulence gene was found to be more prevalent in S. Enteritidis and untyped Salmonella isolates compared to S. Typhimurium isolates. Six common virulence genes (invA, agfA, IpfA, hilA, sivH, and spvC) were detected in all isolates of Salmonella, which was incompatible with prior findings around the world [111–114]. Moreover, sefA and spvC genes were detected in S. Enteritidis and untyped Salmonella isolates, whilst none of the S. Typhimurium isolates carried sefA and spvC genes. Alike findings have been recorded previously by researchers [112]. The higher occurrence of sefA in S. Enteritidis was compatible with prior findings [111, 114], and sefA was somewhat considered a target gene for encountering S. Enteritidis through the PCR method [111]. Successively, the invA gene was the most common and virulent gene present in all Salmonella isolates and was considered as a target gene for identifying Salmonella species [33, 115]. Continually, the hilA gene played a key role in exaggerating Salmonella virulence by stimulating the expression of invasion into the cell [116, 117]. Furthermore, the virulence genes invA and hilA could be considered target genes for rapid and reliable detection of Salmonella through the PCR method. The higher occurrence of lpfA, agfA, and sopE were consistent with previous research results [38, 118]. The occurrence of the sopE gene (100%) in S. Enteritidis was correlated with earlier studies [119]. Further, the agfA gene is liable for biofilm development along with adhesion to cells during the infection process [120]. In our study, the plasmid-mediated spvC virulence gene was detected in S. Enteritidis and untyped Salmonella isolates, which have similarities to earlier observations [111, 121, 122]. It was previously found S. Enteritidis had 92% spvC gene while S. Typhimurium had only 28% and S. Hadar had none [112]. The higher prevalence of major virulence genes indicated the pathobiology as well as the public health implications of the serovars. Moreover, all Salmonella enterica isolates were found to be highly invasive and enterotoxigenic, which had a significant public health impact. This was the first-ever attempt to determine a wider range of Salmonella virulence genes from poultry processing environments at wet markets in Dhaka, Bangladesh.

Our results demonstrated that wet markets where chicken has been slaughtered and processed could spread and harbour NTS enterica serovars. Many studies have shown that cross-contamination of poultry could occur during processing and skinning in wet markets due to poor sanitary and hygienic measures [39]. In wet markets, the sources of contamination may be vendors, chopping board swab, knife swab, carcass dressing water, defeathering machines, scalding water, tanks, floors, drains, and work benches, etc. [39]. Free roaming MDR NTS serovars in poultry processing environments could facilitate release into the food chain, agricultural goods, and human populations in wet markets. Furthermore, Salmonella serovars were able to survive longer in soil-formed biofilms, and these biofilms were protected from detergents and sanitizers [123]. Therefore, cleaning and sterilization of the knife, chopping board, and frequent change of carcass dressing water are crucial to reduce the burden of horizontal transmission of Salmonella enterica in wet markets. The root causes indicated that MDR and highly pathogenic NTS enterica have emerged in poultry due to the irrational use of antimicrobials in farming practices.

Conclusion

The higher prevalence of multiple virulence and multidrug resistant NTS enterica serovars in the poultry processing environments drew public health attention. Chicken carcasses are dressed and processed in the open environment of the wet market, which exacerbated the spread of pathogens. The unclean and utilized utensils such as chopping boards and knives were used for chicken processing and cutting. Furthermore, unclean and dirty water were used frequently for chicken carcass dressing and washing. Numerous risk factors are prevailing at wet markets that can trigger the spread and contamination of NTS serovars. The wet market can be considered a hotspot for harboring NTS serovars which can easily anchor in the food chain as well as human health. The hidden source of these MDR pathogens was undoubtedly chickens, which indicates that there was more therapeutic and preventive exposure to antibiotics during the production cycle. The clean, hygienic and ambient poultry processing environments with good carcass processing practices might reduce the spread of contamination at wet markets. Besides, prudent and judicious use of antimicrobials has to be ensured in farming practices, as poultry farming is considered a fertile ground for the use of antimicrobials. This study could address the potential risk associated with the spread of NTS with multidrug resistance to humans as well as highlight the need to implement a strict hygiene and sanitation standards in local wet markets.

Supporting information

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

Acknowledgments

The author is very grateful for the logistics and technical support by the project "Combating the threat of antibiotic resistance and zoonotic diseases to achieve Bangladesh’s GHSA" during sample collection. We would like to thank Dr. Mohammod Kamruj Jaman Bhuiyan, Department of Agricultural and Applied Statistics, Bangladesh Agricultural University, Mymensingh-2202 for statistical analysis.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting information files.

Funding Statement

The authors received no specific funding for this work.

References

- 1.Hawker J, Begg N, Reintjes R, Ekdahl K, Edeghere O, Van Steenbergen JE. Communicable disease control and health protection handbook. John Wiley & Sons; 2018. Dec 3. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jain P, Chowdhury G, Samajpati S, Basak S, Ganai A, Samanta S, et al. Characterization of non-typhoidal Salmonella isolates from children with acute gastroenteritis, Kolkata, India, during 2000–2016. Braz J Microbiol. 2020. Jun; 51(2):613–27. doi: 10.1007/s42770-019-00213-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lin D, Yan M, Lin S, Chen S. Increasing prevalence of hydrogen sulfide negative Salmonella in retail meats. Food Microbiol. 2014. Oct 1; 43:1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2014.04.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sallam KI, Mohammed MA, Hassan MA, Tamura T. Prevalence, molecular identification and antimicrobial resistance profile of Salmonella serovars isolated from retail beef products in Mansoura, Egypt. Food control. 2014. Apr 1; 38:209–14. doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2013.10.027 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kirk MD, Pires SM, Black RE, Caipo M, Crump JA, Devleesschauwer B, et al. World Health Organization estimates of the global and regional disease burden of 22 foodborne bacterial, protozoal, and viral diseases, 2010: a data synthesis. PLoS Med. 2015. Dec 3; 12(12):e1001921. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pang L, Zhang Z, Xu J. Surveillance of foodborne disease outbreaks in China in 2006–2010. Chin J Food Hyg. 2011; 23:560–3. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Issenhuth-Jeanjean S, Roggentin P, Mikoleit M, Guibourdenche M, de Pinna E, Nair S, et al. Supplement 2008–2010 (no. 48) to the white–Kauffmann–Le minor scheme. Res Microbiol. 2014. Sep 1; 165(7):526–30. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2014.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Takaya A, Yamamoto T, Tokoyoda K. Humoral immunity vs. Salmonella. Front Immunol. 2020. Jan 21; 10:3155. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.03155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Behravesh CB, Brinson D, Hopkins BA, Gomez TM. Backyard poultry flocks and salmonellosis: a recurring, yet preventable public health challenge. Clin Infect Dis. 2014. May 15; 58(10):1432–8. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gieraltowski L, Higa J, Peralta V, Green A, Schwensohn C, Rosen H, et al. National outbreak of multidrug resistant Salmonella Heidelberg infections linked to a single poultry company. PloS one. 2016. Sep 15; 11(9):e0162369. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0162369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Keerthirathne TP, Ross K, Fallowfield H, Whiley H. Reducing risk of salmonellosis through egg decontamination processes. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017. Mar; 14(3):335. doi: 10.3390/ijerph14030335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Biswas S, Li Y, Elbediwi M, Yue M. Emergence and dissemination of mcr-carrying clinically relevant Salmonella Typhimurium monophasic clone ST34. Microorganisms. 2019. Sep; 7(9):298. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms7090298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yu H, Elbediwi M, Zhou X, Shuai H, Lou X, Wang H, et al. Epidemiological and genomic characterization of Campylobacter jejuni isolates from a foodborne outbreak at Hangzhou, China. Int J Mol Sci. 2020. Jan; 21(8):3001. doi: 10.3390/ijms21083001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ed-Dra A, Karraouan B, El Allaoui A, Khayatti M, El Ossmani H, Filali FR, et al. Antimicrobial resistance and genetic diversity of Salmonella Infantis isolated from foods and human samples in Morocco. J Glob Antimicrob Resist. 2018. Sep 1; 14:297–301. doi: 10.1016/j.jgar.2018.05.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Paudyal N, Pan H, Wu B, Zhou X, Zhou X, Chai W, et al. Persistent asymptomatic human infections by Salmonella enterica serovar Newport in China. Msphere. 2020. Jun 24; 5(3). doi: 10.1128/mSphere.00163-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jiang Z, Paudyal N, Xu Y, Deng T, Li F, Pan H, et al. Antibiotic resistance profiles of Salmonella recovered from finishing pigs and slaughter facilities in Henan, China. Front Microbiol. 2019. Jul 4; 10:1513. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.01513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Elbediwi M, Pan H, Biswas S, Li Y, Yue M. Emerging colistin resistance in Salmonella enterica serovar Newport isolates from human infections. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2020. Jan 1; 9(1):535–8. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2020.1733439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Park HC, Baig IA, Lee SC, Moon JY, Yoon MY. Development of ssDNA aptamers for the sensitive detection of Salmonella typhimurium and Salmonella enteritidis. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2014. Sep; 174(2):793–802. doi: 10.1007/s12010-014-1103-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Spector MP, Kenyon WJ. Resistance and survival strategies of Salmonella enterica to environmental stresses. Food Res Int. 2012. Mar 1; 45(2):455–81. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2011.06.056 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Freitas CG, Santana ÂP, da Silva PH, Gonçalves VS, Barros MD, Torres FA, et al. PCR multiplex for detection of Salmonella Enteritidis, Typhi and Typhimurium and occurrence in poultry meat. Int J Food Microbiol. 2010. Apr 30; 139(1–2):15–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2010.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shah AH, Korejo NA. Antimicrobial resistance profile of Salmonella serovars isolated from chicken meat. J Vet Anim Sci. 2012; 2:40–6. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Suresh T, Hatha AA, Sreenivasan D, Sangeetha N, Lashmanaperumalsamy P. Prevalence and antimicrobial resistance of Salmonella enteritidis and other salmonellas in the eggs and egg-storing trays from retails markets of Coimbatore, South India. Food Microbiol. 2006. May 1; 23(3):294–9. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2005.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Momtaz S, Saha O, Usha MK, Sultana M, Hossain MA. Occurrence of pathogenic and multidrug resistant Salmonella spp. in poultry slaughter-house in Bangladesh. Bioresearch Communications-(BRC). 2018. Jul 1; 4(2):506–15. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sultana M, Bilkis R, Diba F, Hossain MA. Predominance of multidrug resistant zoonotic Salmonella Enteritidis genotypes in poultry of Bangladesh. J Poult Sci. 2014:0130222. doi: 10.2141/jpsa.0130222 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Manyi-Loh C, Mamphweli S, Meyer E, Okoh A. Antibiotic use in agriculture and its consequential resistance in environmental sources: potential public health implications. Molecules. 2018. Apr; 23(4):795. doi: 10.3390/molecules23040795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.O’Neill J. Review on Antimicrobial Resistance Antimicrobial Resistance: Tackling a crisis for the health and wealth of nations. London: Review on Antimicrobial Resistance. 2014. https://amr-review.org/sites/default/files/AMR%20Review%20Paper%20-%20Tackling%20a%20crisis%20for%20the%20health%20and%20wealth%20of%20nations_1.pdf

- 27.Robicsek A, Strahilevitz J, Sahm DF, Jacoby GA, Hooper DC. qnr prevalence in ceftazidime-resistant Enterobacteriaceae isolates from the United States. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2006. Aug 1; 50(8):2872–4. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01647-05 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Interagency Coordination Group (IACG). No Time to Wait: Securing the Future from Drug-Resistant Infections, Report to the Secretary General of the United Nations; Interagency Coordination Group: New York, NY, USA; 2019.

- 29.Al Masud A, Rousham EK, Islam MA, Alam MU, Rahman M, Al Mamun A, et al. Drivers of antibiotic use in poultry production in Bangladesh: dependencies and dynamics of a patron-client relationship. Front Vet Sci. 2020; 7. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2020.00078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.O’Bryan CA, Crandall PG, Ricke SC. Antimicrobial resistance in foodborne pathogens. Food and Feed Safety Systems and Analysis. 2018. Jan 1; 99–115. doi: 10.1016/C2016-0-00136-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alam SB, Mahmud M, Akter R, Hasan M, Sobur A, Nazir KH, et al. Molecular detection of multidrug resistant Salmonella species isolated from broiler farm in Bangladesh. Pathogens. 2020. Mar; 9(3):201. doi: 10.3390/pathogens9030201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Siddiky NA, Sarker MS, Khan M, Rahman S, Begum R, Kabir M, et al. Virulence and Antimicrobial Resistance Profiles of Salmonella enterica Serovars Isolated from Chicken at Wet Markets in Dhaka, Bangladesh. Microorganisms. 2021. May; 9(5):952. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms9050952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nayak R, Stewart T, Wang RF, Lin J, Cerniglia CE, Kenney PB. Genetic diversity and virulence gene determinants of antibiotic-resistant Salmonella isolated from preharvest turkey production sources. Int J Food Microbiol. 2004. Feb 15; 91(1):51–62. doi: 10.1016/S0168-1605(03)00330-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Darwin KH, Miller VL. InvF is required for expression of genes encoding proteins secreted by the SPI1 type III secretion apparatus in Salmonella typhimurium. J Bacteriol. 1999. Aug 15; 181(16):4949–54. doi: 10.1128/JB.181.16.4949-4954.1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huehn S, La Ragione RM, Anjum M, Saunders M, Woodward MJ, Bunge C, et al. Virulotyping and antimicrobial resistance typing of Salmonella enterica serovars relevant to human health in Europe. Foodborne Pathog Dis. 2010. May 1; 7(5):523–35. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2009.0447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Silva C, Puente JL, Calva E. Salmonella virulence plasmid: pathogenesis and ecology. Pathog Dis. 2017. Aug;75(6):ftx070. doi: 10.1093/femspd/ftx070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bäumler AJ, Heffron F. Identification and sequence analysis of lpfABCDE, a putative fimbrial operon of Salmonella typhimurium. J Bacteriol. 1995. Apr 1; 177(8):2087–97. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.8.2087-2097.1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Collinson SK, Doig PC, Doran JL, Clouthier S, Kay WW. Thin, aggregative fimbriae mediate binding of Salmonella enteritidis to fibronectin. J Bacteriol. 1993. Jan 1; 175(1):12–8. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.1.12-18.1993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nidaullah H, Abirami N, Shamila-Syuhada AK, Chuah LO, Nurul H, Tan TP, et al. Prevalence of Salmonella in poultry processing environments in wet markets in Penang and Perlis, Malaysia. Vet World. 2017. Mar; 10(3):286. doi: 10.14202/vetworld.2017.286-292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bupasha ZB, Begum R, Karmakar S, Akter R, Bayzid M, Ahad A, et al. Multidrug-Resistant Salmonella spp. Isolated from Apparently Healthy Pigeons in a Live Bird Market in Chattogram, Bangladesh. World’s Vet J. 2020. Dec 25; 10(4):508–13. doi: 10.29252/scil.2020.wvj61 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sripaurya B, Ngasaman R, Benjakul S, Vongkamjan K. Virulence genes and antibiotic resistance of Salmonella recovered from a wet market in Thailand. J Food Saf. 2019. Apr; 39(2):e12601. doi: 10.1111/jfs.12601 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Naing L, Winn T, Rusli BN. Practical issues in calculating the sample size for prevalence studies. Arch Orofac Sci. 2006; 1:9–14. https://www.scribd.com/doc/63105077/How-to-Calculate-Sample-Size [Google Scholar]

- 43.Daniel WW. Biostatistics: A Foundation for Analysis in the Health Sciences, 7th ed.; John Willey & Sons: New York, NY, USA; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 44.ISO, 6579: 2002. Microbiology of Food and Animal Feeding Stuffs. Horizontal Method for the Detection of Salmonella spp.; British Standard Institute: London, UK; 2002.

- 45.Sarker MS, Ahad A, Ghosh SK, Mannan MS, Sen A, Islam S, et al. Antibiotic-resistant Escherichia coli in deer and nearby water sources at safari parks in Bangladesh. Vet World. 2019. Oct; 12(10):1578. doi: 10.14202/vetworld.2019.1578-1583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Heidary M, Momtaz H, Madani M. Characterization of diarrheagenic antimicrobial resistant Escherichia coli isolated from pediatric patients in Tehran, Iran. Iran. Red. Crescent. Med. J. 2014. Apr; 16 (4) doi: 10.5812/ircmj.12329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zahraei SM, Mahzoniae MR, Ashrafi A. Amplification of invA gene of Salmonalla by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) as a specific method for detection of salmonellae. J Vet Res. 2006; 61(2):195–199. https://www.sid.ir/en/journal/ViewPaper.aspx?id=83064 [Google Scholar]

- 48.Agron PG, Walker RL, Kinde H, Sawyer SJ, Hayes DC, Wollard J, et al. Identification by subtractive hybridization of sequences specific for Salmonella enterica serovar Enteritidis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2001. Nov 1; 67(11):4984–91. doi: 10.1128/AEM.67.11.4984-4991.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Alvarez J, Sota M, Vivanco AB, Perales I, Cisterna R, Rementeria A, et al. Development of a multiplex PCR technique for detection and epidemiological typing of Salmonella in human clinical samples. J Clin Microbiol. 2004. Apr 1; 42(4):1734–8. https://dx.doi.org/10.1128%2FJCM.42.4.1734-1738.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing; Approved Standard, 28th ed.; Document M100, 2019; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute: Wayne, PA, USA, 2019.

- 51.Magiorakos AP, Srinivasan A, Carey RT, Carmeli Y, Falagas MT, Giske CT, et al. Multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and pandrug-resistant bacteria: an international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012. Mar 1; 18(3):268–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03570.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jaja IF, Bhembe NL, Green E, Oguttu J, Muchenje V. Molecular characterisation of antibiotic-resistant Salmonella enterica isolates recovered from meat in South Africa. Acta trop. 2019. Feb 1; 190:129–36. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2018.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Adzitey F, Rusul G, Huda N. Prevalence and antibiotic resistance of Salmonella serovars in ducks, duck rearing and processing environments in Penang, Malaysia. Food Res Int. 2012. Mar 1; 45(2):947–52. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2011.02.051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Titilawo Y, Sibanda T, Obi L, Okoh A. Multiple antibiotic resistance indexing of Escherichia coli to identify high-risk sources of faecal contamination of water. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2015. Jul; 22(14):10969–80. doi: 10.1007/s11356-014-3887-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chitanand MP, Kadam TA, Gyananath G, Totewad ND, Balhal DK. Multiple antibiotic resistance indexing of coliforms to identify high risk contamination sites in aquatic environment. Indian J Microbiol. 2010. Jun; 50(2):216–20. doi: 10.1007/s12088-010-0042-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dallenne C, Da Costa A, Decré D, Favier C, Arlet G. Development of a set of multiplex PCR assays for the detection of genes encoding important β-lactamases in Enterobacteriaceae. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2010. Mar 1; 65(3):490–5. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkp498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kozak GK, Boerlin P, Janecko N, Reid-Smith RJ, Jardine C. Antimicrobial resistance in Escherichia coli isolates from swine and wild small mammals in the proximity of swine farms and in natural environments in Ontario, Canada. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2009. Feb 1; 75(3):559–66. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01821-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Malorny B, Hoorfar J, Hugas M, Heuvelink A, Fach P, Ellerbroek L, et al. Interlaboratory diagnostic accuracy of a Salmonella specific PCR-based method. Int J Food Microbiol. 2003. Dec 31; 89(2–3):241–9. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1605(03)00154-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cesco MAO, Zimermann FC, Giotto DB, Guayba J, Borsoi A, Rocha SLS, et al. Pesquisa de Genes de Virulência em Salmonella Hadar em Amostras Provenientes de Material Avícola; R0701-0; Anais 35 Congresso Brasileiro de Medicina Veterinária: Porto Alegre, Brazil, 2008.

- 60.Guo X, Chen J, Beuchat LR, Brackett RE. PCR detection of Salmonella enterica serotype Montevideo in and on raw tomatoes using primers derived from hila. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2000. Dec 1; 66(12):5248–52. doi: 10.1128/AEM.66.12.5248-5252.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kingsley RA, Humphries AD, Weening EH, De Zoete MR, Winter S, Papaconstantinopoulou A, et al. Molecular and phenotypic analysis of the CS54 island of Salmonella enterica serotype Typhimurium: identification of intestinal colonization and persistence determinants. Infect Immun. 2003. Feb 1; 71(2):629–40. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.2.629-640.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Oliveira SD, Santos LR, Schuch DM, Silva AB, Salle CT, Canal CW. Detection and identification of salmonellas from poultry-related samples by PCR. Vet Microbiol. 2002. Jun 5; 87(1):25–35. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1135(02)00028-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Prager R, Rabsch W, Streckel W, Voigt W, Tietze E, Tschäpe H. Molecular properties of Salmonella enterica serotype Paratyphi B distinguish between its systemic and its enteric pathovars. J Clin Microbiol. 2003. Sep 1; 41(9):4270–8. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.9.4270-4278.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Swamy SC, Barnhart HM, Lee MD, Dreesen DW. Virulence determinants invA and spvC in salmonellae isolated from poultry products, wastewater, and human sources. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996. Oct 1; 62(10):3768–71. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.10.3768-3771.1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Akond MA, Shirin M, Alam S, Hassan SM, Rahman MM, Hoq M. Frequency of drug resistant Salmonella spp. isolated from poultry samples in Bangladesh. Stamford J Microbiol. 2012; 2(1):15–9. doi: 10.3329/sjm.v2i1.15207 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Karim MR, Giasuddin M, Samad MA, Mahmud MS, Islam MR, Rahman MH, et al. Prevalence of Salmonella spp. in poultry and poultry products in Dhaka, Bangladesh. Int J Anim Biol. 2017; 3(4):18–22. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Al Mamun MA, Kabir SL, Islam MM, Lubna M, Islam SS, Akhter AT, et al. Molecular identification and characterization of Salmonella species isolated from poultry value chains of Gazipur and Tangail districts of Bangladesh. Afr J Microbiol Res. 2017. Mar 21; 11(11):474–81. doi: 10.5897/AJMR2017-8431 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mahmud MS, Bari ML, Hossain MA. Prevalence of Salmonella serovars and antimicrobial resistance profiles in poultry of Savar area, Bangladesh. Foodborne Pathog Dis. 2011. Oct 1; 8(10):1111–8. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2011.0917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mridha D, Uddin MN, Alam B, Akhter AT, Islam SS, Islam MS, et al. Identification and characterization of Salmonella spp. from samples of broiler farms in selected districts of Bangladesh. Vet World. 2020. Feb; 13(2):275. doi: 10.14202/vetworld.2020.275-283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sarker BR, Ghosh S, Chowdhury S, Dutta A, Chandra Deb L, Krishna Sarker B, et al. Prevalence and antimicrobial susceptibility profiles of non-typhoidal Salmonella isolated from chickens in Rajshahi, Bangladesh. Vet Med Sci. 2021. May; 7(3):820–830. doi: 10.1002/vms3.440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Parvin MS, Hasan MM, Ali MY, Chowdhury EH, Rahman MT, Islam MT. Prevalence and Multidrug Resistance Pattern of Salmonella Carrying Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamase in Frozen Chicken Meat in Bangladesh. J Food Prot. 2020. Dec; 83(12):2107–21. doi: 10.4315/JFP-20-172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Garedew L, Hagos Z, Addis Z, Tesfaye R, Zegeye B. Prevalence and antimicrobial susceptibility patterns of Salmonella isolates in association with hygienic status from butcher shops in Gondar town, Ethiopia. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2015. Dec; 4(1):1–7. doi: 10.1186/s13756-015-0062-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sharma J, Kumar D, Hussain S, Pathak A, Shukla M, Kumar VP, et al. Prevalence, antimicrobial resistance and virulence genes characterization of nontyphoidal Salmonella isolated from retail chicken meat shops in Northern India. Food control. 2019. Aug 1; 102:104–11. doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2019.01.021 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Waghamare RN, Paturkar AM, Zende RJ, Vaidya VM, Gandage RS, Aswar NB, et al. Studies on occurrence of invasive Salmonella spp. from unorganised poultry farm to retail chicken meat shops in Mumbai city, India. Int J Curr Microbiol Appl Sci. 2017; 6(5):630–41. doi: 10.20546/ijcmas.2017.605.073 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kaushik P, Kumari S, Bharti SK, Dayal S. Isolation and prevalence of Salmonella from chicken meat and cattle milk collected from local markets of Patna, India. Vet World. 2014. Feb 1; 7(2):62. doi: 10.14202/vetworld.2014.62-65 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Rusul G, Khair J, Radu S, Cheah CT, Yassin RM. Prevalence of Salmonella in broilers at retail outlets, processing plants and farms in Malaysia. Int J Food Microbiol. 1996. Dec 1; 33(2–3):183–94. doi: 10.1016/0168-1605(96)01125-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Thung TY, Radu S, Mahyudin NA, Rukayadi Y, Zakaria Z, Mazlan N, et al. Prevalence, virulence genes and antimicrobial resistance profiles of Salmonella serovars from retail beef in Selangor, Malaysia. Front Microbiol. 2018. Jan 11; 8:2697. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.02697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.McCrea BA, Tonooka KH, VanWorth C, Atwill ER, Schrader JS, Boggs CL. Prevalence of Campylobacter and Salmonella species on farm, after transport, and at processing in specialty market poultry. Poult Sci. 2006. Jan 1; 85(1):136–43. doi: 10.1093/ps/85.1.136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Saitanu K, Jerngklinchan J, Koowatananukul C. Incidence of salmonellae in duck eggs in Thailand. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 1994. Jun 1; 25:328–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Islam MJ, Mahbub-E-Elahi ATM, Ahmed T, Hasan MK. Isolation and identification of Salmonella spp. from broiler and their antibiogram study in Sylhet, Bangladesh. J Appl Biol Biotechnol. 2016; 4: 046–051. doi: 10.7324/JABB.2016.40308 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Parvej MS, Rahman M, Uddin MF, Nazir KN, Jowel MS, Khan MF, et al. Isolation and characterization of Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium circulating among healthy chickens of Bangladesh. Turkish Journal of Agriculture-Food Science and Technology. 2016. Jul 15; 4(7):519–23. doi: 10.24925/turjaf.v4i7.519-523.695 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Arkali A, Çetinkaya B. Molecular identification and antibiotic resistance profiling of Salmonella species isolated from chickens in eastern Turkey. BMC Vet Res. 2020. Dec; 16(1):1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12917-019-2207-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Samanta I, Joardar SN, Das PK, Das P, Sar TK, Dutta TK, et al. Virulence repertoire, characterization, and antibiotic resistance pattern analysis of Escherichia coli isolated from backyard layers and their environment in India. Avian Dis. 2014. Mar;58(1):39–45. doi: 10.1637/10586-052913-Reg.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Tarabees R, Elsayed MS, Shawish R, Basiouni S, Shehata AA. Isolation and characterization of Salmonella Enteritidis and Salmonella Typhimurium from chicken meat in Egypt. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2017. Apr 30; 11(04):314–9. doi: 10.3855/jidc.8043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Osimani A, Aquilanti L, Clementi F. Salmonellosis associated with mass catering: a survey of European Union cases over a 15-year period. Epidemiol Infect. 2016. Oct; 144(14):3000–12. doi: 10.1017/S0950268816001540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Zeng YB, Xiong LG, Tan MF, Li HQ, Yan H, Zhang L, et al. Prevalence and antimicrobial resistance of Salmonella in pork, chicken, and duck from retail markets of China. Foodborne Pathog Dis. 2019. May 1; 16(5):339–45. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2018.2510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Sobur A, Hasan M, Haque E, Mridul AI, Noreddin A, El Zowalaty ME, et al. Molecular detection and antibiotyping of multidrug-resistant Salmonella isolated from houseflies in a fish market. Pathogens. 2019. Dec; 8(4):191. doi: 10.3390/pathogens8040191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Long M, Lai H, Deng W, Zhou K, Li B, Liu S, et al. Disinfectant susceptibility of different Salmonella serotypes isolated from chicken and egg production chains. J Appl Microbiol. 2016. Sep; 121(3):672–81. doi: 10.1111/jam.13184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Im MC, Jeong SJ, Kwon YK, Jeong OM, Kang MS, Lee YJ. Prevalence and characteristics of Salmonella spp. isolated from commercial layer farms in Korea. Poult Sci. 2015. Jul 1; 94(7):1691–8. doi: 10.3382/ps/pev137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Vuthy Y, Lay KS, Seiha H, Kerleguer A, Aidara-Kane A. Antibiotic susceptibility and molecular characterization of resistance genes among Escherichia coli and among Salmonella subsp. in chicken food chains. Asian Pac J Trop Biomed. 2017. Jul 1; 7(7):670–4. doi: 10.1016/j.apjtb.2017.07.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Xu Y, Zhou X, Jiang Z, Qi Y, Ed-Dra A, Yue M. Epidemiological investigation and antimicrobial resistance profiles of Salmonella isolated from breeder chicken hatcheries in Henan, China. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2020. Sep 15; 10:497. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2020.00497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Zhu Y, Lai H, Zou L, Yin S, Wang C, Han X, et al. Antimicrobial resistance and resistance genes in Salmonella strains isolated from broiler chickens along the slaughtering process in China. Int J Food Microbiol. 2017. Oct 16; 259:43–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2017.07.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.El-Sharkawy H, Tahoun A, El-Gohary AE, El-Abasy M, El-Khayat F, Gillespie T, et al. Epidemiological, molecular characterization and antibiotic resistance of Salmonella enterica serovars isolated from chicken farms in Egypt. Gut Pathog. 2017. Dec; 9(1):1–2. doi: 10.1186/s13099-017-0157-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Mishra M, Patel AK, Behera N. Prevalence of multidrug resistant E. coli in the river Mahanadi of Sambalpur. Curr Res Microbiol Biotechnol, 2013: 1(5): 239–244. http://crmb.aizeonpublishers.net/content/2013/5/crmb239-244.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 95.Thenmozhi S, Rajeswari P, Kumar BS, Saipriyanga V, Kalpana M. Multi-drug resistant patterns of biofilm forming Aeromonas hydrophila from urine samples. IJPSR, 2014; 5(7): 2908. https://ijpsr.com/bft-article/multi-drug-resistant-patterns-of-biofilm-forming-aeromonas-hydrophila-from-urine-samples/ [Google Scholar]

- 96.Ahmed D, Ud-Din AI, Wahid SU, Mazumder R, Nahar K, Hossain A. Emergence of blaTEM type extended-spectrum β-lactamase producing Salmonella spp. in the urban area of Bangladesh. Int Sch Res Notices. 2014; 2014. doi: 10.1155/2014/715310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Yang B, Qu D, Zhang X, Shen J, Cui S, Shi Y, et al. Prevalence and characterization of Salmonella serovars in retail meats of marketplace in Shaanxi, China. Int J Food Microbiol. 2010. Jun 30; 141(1–2):63–72. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2010.04.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Aslam M, Checkley S, Avery B, Chalmers G, Bohaychuk V, Gensler G, et al. Phenotypic and genetic characterization of antimicrobial resistance in Salmonella serovars isolated from retail meats in Alberta, Canada. Food Microbiol. 2012. Oct 1; 32(1):110–7. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2012.04.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Lu Y, Wu CM, Wu GJ, Zhao HY, He T, Cao XY, et al. Prevalence of antimicrobial resistance among Salmonella isolates from chicken in China. Foodborne Pathog Dis. 2011. Jan 1; 8(1):45–53. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2010.0605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Van TT, Chin J, Chapman T, Tran LT, Coloe PJ. Safety of raw meat and shellfish in Vietnam: an analysis of Escherichia coli isolations for antibiotic resistance and virulence genes. Int J Food Microbiol. 2008. Jun 10; 124(3):217–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2008.03.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Xiang Y, Li F, Dong N, Tian S, Zhang H, Du X, et al. Investigation of a Salmonellosis outbreak caused by multidrug resistant Salmonella Typhimurium in China. Front Microbiol. 2020. Apr 29; 11:801. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.00801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]