Summary

Background

We describe post-COVID symptomatology in a non-hospitalised, national sample of adolescents aged 11–17 years with PCR-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection compared with matched adolescents with negative PCR status.

Methods

In this national cohort study, adolescents aged 11–17 years from the Public Health England database who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 between January and March, 2021, were matched by month of test, age, sex, and geographical region to adolescents who tested negative. 3 months after testing, a subsample of adolescents were contacted to complete a detailed questionnaire, which collected data on demographics and their physical and mental health at the time of PCR testing (retrospectively) and at the time of completing the questionnaire (prospectively). We compared symptoms between the test-postive and test-negative groups, and used latent class analysis to assess whether and how physical symptoms at baseline and at 3 months clustered among participants. This study is registered with the ISRCTN registry (ISRCTN 34804192).

Findings

23 048 adolescents who tested positive and 27 798 adolescents who tested negative between Jan 1, 2021, and March 31, 2021, were contacted, and 6804 adolescents (3065 who tested positive and 3739 who tested negative) completed the questionnaire (response rate 13·4%). At PCR testing, 1084 (35·4%) who tested positive and 309 (8·3%) who tested negative were symptomatic and 936 (30·5%) from the test-positive group and 231 (6·2%) from the test-negative group had three or more symptoms. 3 months after testing, 2038 (66·5%) who tested positive and 1993 (53·3%) who tested negative had any symptoms, and 928 (30·3%) from the test-positive group and 603 (16·2%) from the test-negative group had three or more symptoms. At 3 months after testing, the most common symptoms among the test-positive group were tiredness (1196 [39·0%]), headache (710 [23·2%]), and shortness of breath (717 [23·4%]), and among the test-negative group were tiredness (911 [24·4%]), headache (530 [14·2%]), and other (unspecified; 590 [15·8%]). Latent class analysis identified two classes, characterised by few or multiple symptoms. The estimated probability of being in the multiple symptom class was 29·6% (95% CI 27·4–31·7) for the test-positive group and 19·3% (17·7–21·0) for the test-negative group (risk ratio 1·53; 95% CI 1·35–1·70). The multiple symptoms class was more frequent among those with positive PCR results than negative results, in girls than boys, in adolescents aged 15–17 years than those aged 11–14 years, and in those with lower pretest physical and mental health.

Interpretation

Adolescents who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 had similar symptoms to those who tested negative, but had a higher prevalence of single and, particularly, multiple symptoms at the time of PCR testing and 3 months later. Clinicians should consider multiple symptoms that affect functioning and recognise different clusters of symptoms. The multiple and varied symptoms show that a multicomponent intervention will be required, and that mental and physical health symptoms occur concurrently, reflecting their close relationship.

Funding

UK Department of Health and Social Care, in their capacity as the National Institute for Health Research, and UK Research and Innovation.

Introduction

SARS-CoV-2 in children and young people is usually mild1 compared with adults.2 However, little is known about the diagnosis, prevalence, phenotype, or duration of long COVID (also known as post-acute COVID syndrome) in children and young people.3 The English National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) defines acute COVID-19 as disease with symptoms that last less than 4 weeks after confirmed infection. Ongoing symptomatic COVID-19 is defined as disease with symptoms lasting 4–12 weeks, and post COVID-19 syndrome as disease with symptoms lasting more than 12 weeks.

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

This study was designed in November, 2020, when there was little known about long COVID in general and long COVID in children and young people in particular. Of the few publications, most reported data from clinical populations of children and young people seeking treatment and did not include controls. A search on July 26, 2021, of Medline, Cochrane, medRxiv, and PROSPERO, using the terms “COVID-19”, “sars-cov-2”, “child”, “adolescents”, “youth”, “young”, “long-COVID”, “sequelae”, “post acute” and “persistent”, from inception and with no language restrictions, did not identify any controlled, cohort studies of continuing symptoms following SARS-CoV-2 infection in non-hospitalised children or adolescents before our study was designed.

Added value of this study

This is a large cohort study of adolescents with PCR-proven SARS-CoV-2 status, not self-reported infection. The symptoms were reported by the adolescents themselves and, importantly, there was a matched test-negative group of adolescents who have lived through the pandemic but never tested positive for SARS-CoV-2. The participants were recruited nationally. Physical and mental health symptoms were described rather than undefined, self-reported long COVID. There was an increase in symptoms in adolescents who were either test-positive or test-negative 3 months after testing. The symptom profile was similar between the two groups but with a higher prevalence of symptoms in adolescents who tested positive than in those who tested negative and, importantly, adolescents who tested positive were more likely than those who tested negative to have multiple symptoms at the time of PCR testing and 3 months later. Subsequent waves of data collection will allow prospective tracking of mental and physical health symptoms in this cohort.

Implications of all the available evidence

We provide data on the presence of 21 physical symptoms and four wellbeing scales 3 months after SARS-CoV-2 testing in 6804 adolescents. Overall, this evidence shows the multiplicity and heterogeneity of long COVID in young people. These findings have implications for services, commissioners, researchers, clinicians, and affected families in understanding the prevalence and manifestation of long COVID in children and young people not accessing hospitals, and in informing health-care systems on service planning.

Ongoing symptomatic COVID-19 and post COVID-19 syndrome are referred to as long COVID4 but the term post COVID-19 condition is also used. Researchers funded by the UK National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) and UK Research and Innovation (UKRI) continue to use the term long COVID because this is used by the public, healthcare professionals, and in literature searches and systematic reviews. Therefore, we use the term long COVID but are explicit that what we report are symptoms 3 months after a positive SARS-CoV-2 test. More than 200 symptoms have been associated with long COVID5, 6 in individuals symptomatic or asymptomatic with acute SARS-CoV-2 infection and as persistent or intermittent symptoms.5, 6 Adolescents might have a higher risk1 than young children but it is unclear if long COVID symptoms are related to the viral infection or the effects of lockdown, school closures, and social isolation.

A July, 2021, literature review of long COVID in children and young people identified 21 relevant publications (appendix pp 16–18, 28–29). These studies included 16 243 children and young people aged 0 to 20 years with follow-up ranging between 28 and 324 days; median follow-up was 125 days (IQR 99–231; appendix pp 16–18, 28–29). Fourteen (67%) were cohort studies, six (29%) were cross-sectional studies, and one was a case report. Seven of the 21 studies included population-based control groups. Nine (43%) recruited from a mix of hospitalised and non-hospitalised children and young people, eight (38%) recruited from non-hospitalised children and young people, and four (19%) recruited hospitalised children or young people post-discharge. The most common symptoms at 3 months were fatigue, insomnia, anosmia, and headaches. The reported rate of long COVID in children and young people was 1–51%, with smaller studies reporting higher rates. Additionally, a UK survey of self-reported or parent-reported long COVID reported a prevalence of 0·16% in those aged 2–11 years, 0·65% in those aged 12–16 years, and 1·22% in those aged 17–24 years.7

The CLoCk study is a national, matched, longitudinal cohort study of children and adolescents in England,8 describing the clinical phenotype and rate of post-COVID physical and mental health problems in those with laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection compared with those who test negative for SARS-CoV-2. This paper presents the descriptive results from the study 3 months after PCR testing.

Methods

Study design

A cohort study of adolescents aged 11–17 years from the Public Health England (PHE) database who tested PCR-positive for SARS-CoV-2 were matched on month of test, age, sex, and geographical area to adolescents who tested negative. PHE receives results of all SARS-CoV-2 PCR tests in England from health-care settings (pillar 1 tests) and community settings (pillar 2 tests), irrespective of reason (screened for school attendance, contact of a positive case, or symptomatic). Only UK National Health Service (NHS) number, name, age, sex, and postcode were recorded. PHE can access the electronic Patient Demographic Service (PDS), containing name, postal address, and vital status (alive or dead) of all NHS patients.

Participants

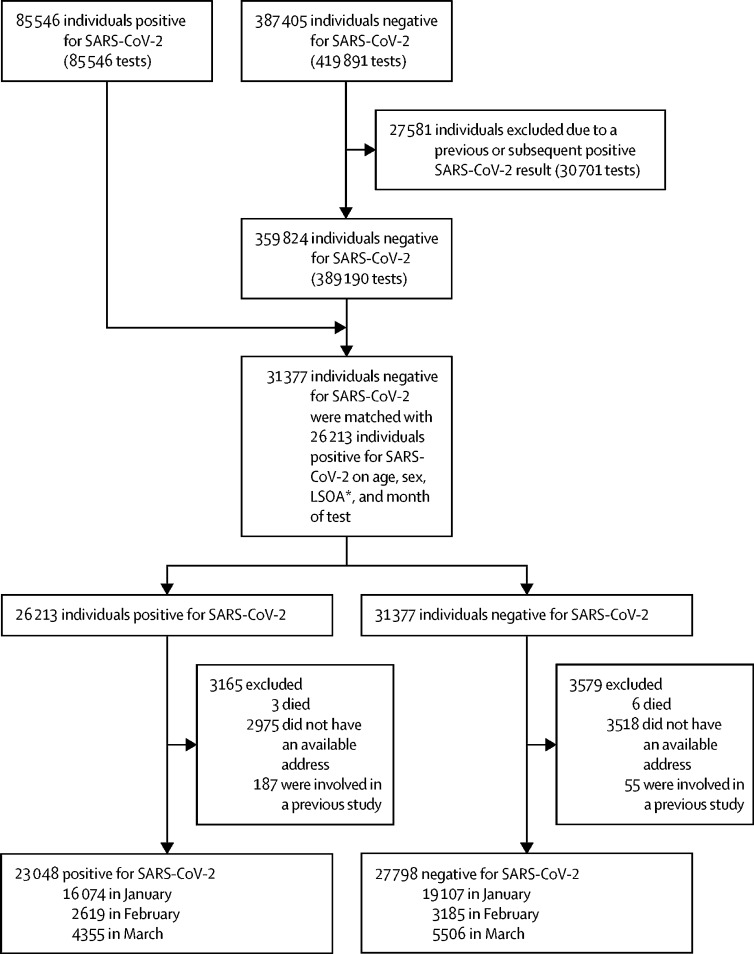

The CLoCk study collects data on more than 19 000 adolescents aged 11–17 years at 6, 12, and 24 months after a SARS-CoV-2 PCR test was taken between September, 2020 and March, 2021.8 Between January and March, 2021, 85 546 adolescents tested positive for SARS-CoV-2, and 387 405 adolescents tested negative of whom 27 581 (7·1%) were excluded from our study because they had previously tested positive or went on to test positive for SARS-CoV-2 in the following 3 months. 23 048 SARS-CoV-2-positive adolescents were matched with 27 798 SARS-CoV-2-negative adolescents, excluding 3165 (13·7%) SARS-CoV-2-positive adolescents and 3579 (12·9%) SARS-CoV-2-negative adolescents who had either died, had no available address, or had been involved in a previous study (target population; figure). We selected a subsample of approximately 7000 participants including 3065 positive adolescents and 3739 negative adolescents (study population). The selection of the study population was based on those who could report, without recall bias, symptoms 3 months after testing because adolescents tested before January, 2021, were more than 3 months post-test at study launch. All participants in the study population gave written informed consent. Our study was approved by Yorkshire and The Humber—South Yorkshire Research Ethics Committee (REC reference: 21/YH/0060; IRAS project ID:293495).

Figure.

Flowchart of young people invited to participate in the study

All participants were aged 11–17 years and had been PCR tested for SARS-CoV-2 between January and March, 2021. LSOA=lower super output areas. *LSOA are a standardised geographical hierarchy designed to improve the reporting of small area statistics in England and Wales.

Procedures

Adolescents tested between January and March, 2021, were contacted by letter 3 months after testing, with reminders 2 and 4 weeks later. Those who consented completed an online questionnaire about their physical and mental health at the time of their PCR test (baseline) and at the time of completing the questionnaire, although symptoms could have waxed and waned over the intervening 3 months; a carer could assist adolescents who requested it and those with special educational needs or disabilities.

The questionnaire assessed participant demographics, included elements of the International Severe Acute Respiratory and emerging Infection Consortium (ISARIC) paediatric COVID-19 questionnaire,9 and included the recent Mental Health of Children and Young people in England surveys.10 Designed with ISARIC Paediatric Working Group as a harmonised data collection tool to facilitate international comparisons, it included the assessment of 21 physical symptoms (mostly assessed as present or absent; appendix pp 6–11, 19–21). The Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD), derived from the adolescent's lower super output area (LSOA; a small local area level-based geographical hierarchy), was used as a proxy for socioeconomic status. We used IMD quintiles from most (quintile 1) to least (quintile 5) deprived.

Participants were asked to rate their physical and mental health before their SARS-CoV-2 test in two separate questions using a five-category Likert scale; for analysis, we recoded these variables into three categories (very poor and poor, okay, and good and very good). To assess mental health and wellbeing, the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ)11 was summarised into the total difficulties score that excluded the prosocial dimension, along with the short 7-item version of the Warwick Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale (SWEMWBS).12 A higher SDQ total difficulties score indicates more behavioural and emotional difficulties and a higher SWEMWBS score indicates better mental wellbeing. Quality of life and functioning was measured using the EQ-5D-Y13 and fatigue was measured by the 11-item Chalder Fatigue Questionnaire (CFQ).14

Statistical analysis

The original study design calculation was that a study population of 5000 participants (2500 test-positives and 2500 test-negatives) would have 80% power to detect a difference of at least 4% in symptom frequency at 5% significance, if test-negative participants had a 34% symptom prevalence (based on available data at the time),15 accounting for attrition and possible lower baseline symptom prevalence. A difference of 4% was thought to be clinically relevant and realistic. To achieve these numbers, accounting for potentially differential response rates in test-positives and negatives, we planned to invite twice as many test-negative participants than test-positive participants (ie, because we expected negatives to be less likely to respond we intended to invite twice as many of them but our aim was always to end up with a ratio of 1:1 positives and negatives completing the questionnaire), and to match the distribution of age, sex, geographical region, and month of testing of the participants who were test-positive. As interest in studying multiple symptoms and in identifying risk factors for long COVID developed, and evidence that long COVID was less common in adolescents increased, we realised a larger study was needed. For these reasons, we invited all test-positives and, when numbers allowed, twice the number of test-negatives (except those tested in December, 2020 due to funding constraints).8

To assess the representativeness of our study population, we compared their demographic characteristics (sex, age, region of residence, and IMD) to those of the target population (all invited participants). The participants' demographic characteristics, physical symptoms at baseline, and physical symptoms, mental health status, wellbeing, quality of life and functioning, and fatigue 3 months after testing were stratified by SARS-CoV-2 test status. As the prevalence of long COVID might vary by age,1, 7 we stratified the analyses into two age groups that reflected key educational stages (11–14 years vs 15–17 years).

We used latent class analysis to assess separately whether and how physical symptoms at baseline and at 3 months clustered among participants.16 We analysed the data jointly by test status but separately by time and allowed for differential model parametrisation by SARS-CoV-2 test status. The number of classes was selected by comparing the Akaike and Bayesian Information Criteria. Predicted class membership was estimated and used to assign participants to their most likely class; this classification was then used to describe the characteristics of the latent classes.

This is a descriptive study. Significance tests should be avoided in descriptive tables according to STROBE guidelines;17 hence we do not report p values for comparisons by SARS-CoV-2 test status at baseline. However, we do report p values for crude (unadjusted) comparisons of symptoms by SARS-CoV-2 test status at 3 months after testing (accounting for multiple testing using Bonferroni correction) and also report estimates of latent class prevalence by SARS-CoV-2 test status, as well as their ratio, with CIs computed using the delta method.18 To assess the effect of potential response bias, we reweighted all symptom frequencies according to the age, sex, region, IMD, and SARS-CoV-2 test status of the responders so that analyses align with the characteristics of the target population. All analyses used STATA version 16.0. This study is registered with the ISRCTN registry (ISRCTN 34804192).

Role of the funding source

The Department of Health and Social Care, as the NIHR, and UKRI awarded grant COVLT0022 but were not involved in study design, data collection, analysis, or writing.

Results

Of 50 846 adolescents who were tested between Jan 1 and March 31, 2021, and were invited to participate, 6804 (13·4%) consented to complete the 3-month questionnaire and constituted the subsample population (table 1), including 3065 (45·0%) who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 and 3739 (55·0%) who tested negative (table 2). A total of 63 adolescents who tested negative reported having had a previous positive SARS-CoV-2 test (before testing) and were excluded. Of those who tested positive, 49 went to hospital with 26 staying overnight. The completed questionnaires were returned at a median of 14·9 weeks (IQR 13·1–18·9) after testing.

Table 1.

Response rate of participants who completed the 3-month questionnaire

| Target population (n=50 846) | Study participants (n=6804) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative SARS-CoV-2 test | 27 798 | 3739 (13·5%) | ||

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 15 120 | 2352 (15·6%) | ||

| Male | 12 678 | 1387 (10·9%) | ||

| Age, years | ||||

| 11–14 | 12 689 | 1609 (12·7%) | ||

| 15–17 | 15 109 | 2130 (14·1%) | ||

| Region (England) | ||||

| East Midlands | 2132 | 340 (15·9%) | ||

| East of England | 4278 | 630 (14·7%) | ||

| London | 5356 | 629 (11·7%) | ||

| North East England | 925 | 122 (13·2%) | ||

| North West England | 3816 | 426 (11·2%) | ||

| South East England | 4262 | 620 (14·5%) | ||

| South West England | 1554 | 293 (18·9%) | ||

| West Midlands | 3414 | 431 (12·6%) | ||

| Yorkshire and the Humber | 2061 | 248 (12·0%) | ||

| IMD quintile* | ||||

| 1 | 8097 | 756 (9·3%) | ||

| 2 | 6300 | 740 (11·7%) | ||

| 3 | 4978 | 733 (14·7%) | ||

| 4 | 4439 | 718 (16·2%) | ||

| 5 | 3984 | 792 (19·9%) | ||

| Positive SARS-CoV-2 test | 23 048 | 3065 (13·3%) | ||

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 12 412 | 1945 (15·7%) | ||

| Male | 10 636 | 1120 (10·5%) | ||

| Age, years | ||||

| 11–14 | 10 651 | 1244 (11·7%) | ||

| 15–17 | 12 397 | 1821 (14·7%) | ||

| Region (UK) | ||||

| East Midlands | 1815 | 297 (16·4%) | ||

| East of England | 3392 | 466 (13·7%) | ||

| London | 4412 | 510 (11·6%) | ||

| North East England | 819 | 111 (13·6%) | ||

| North West England | 3235 | 371 (11·5%) | ||

| South East England | 3496 | 483 (13·8%) | ||

| South West England | 1238 | 238 (19·2%) | ||

| West Midlands | 2854 | 373 (13·1%) | ||

| Yorkshire and the Humber | 1787 | 216 (12·1%) | ||

| IMD quintile* | ||||

| 1 | 6732 | 643 (9·6%) | ||

| 2 | 5198 | 633 (12·2%) | ||

| 3 | 4159 | 571 (13·7%) | ||

| 4 | 3679 | 593 (16·1%) | ||

| 5 | 3280 | 625 (19·1%) | ||

Data are n (%). IMD=Index of Multiple Deprivation.

IMD quintiIe 1 represents most deprived and quintile 5 represents least deprived.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of all study participants who completed the 3-month questionnaire

| All participants (n=6804) | Positive for SARS-CoV-2 (n=3065) | Negative for SARS-CoV-2 (n=3739) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||

| Female | 4297 (63·2%) | 1945 (63·5%) | 2352 (62·9%) |

| Male | 2507 (36·8%) | 1120 (36·5%) | 1387 (37·1%) |

| Age, years | |||

| 11–14 | 2853 (41·9%) | 1244 (40·6%) | 1609 (43·0%) |

| 15–17 | 3951 (58·1%) | 1821 (59·4%) | 2130 (57·0%) |

| Ethnicity | |||

| White | 5035 (74·0%) | 2231 (72·8%) | 2804 (75·0%) |

| Asian or Asian British | 1011 (14·9%) | 491 (16·0%) | 520 (13·9%) |

| Mixed | 342 (5·0%) | 147 (4·8%) | 195 (5·2%) |

| Black, African, or Caribbean | 249 (3·7%) | 109 (3·6%) | 140 (3·7%) |

| Other | 115 (1·7%) | 60 (2·0%) | 55 (1·5%) |

| Unknown | 52 (0·8%) | 27 (0·9%) | 25 (0·7%) |

| Region (England) | |||

| East Midlands | 637 (9·4%) | 297 (9·7%) | 340 (9·1%) |

| East of England | 1096 (16·1%) | 466 (15·2%) | 630 (16·8%) |

| London | 1139 (16·7%) | 510 (16·6%) | 629 (16·8%) |

| North East England | 233 (3·4%) | 111 (3·6%) | 122 (3·3%) |

| North West England | 797 (11·7%) | 371 (12·1%) | 426 (11·4%) |

| South East England | 1103 (16·2%) | 483 (15·8%) | 620 (16·6%) |

| South West England | 531 (7·8%) | 238 (7·8%) | 293 (7·8%) |

| West Midlands | 804 (11·8%) | 373 (12·2%) | 431 (11·5%) |

| Yorkshire and the Humber | 464 (6·8%) | 216 (7·0%) | 248 (6·6%) |

| IMD quintile* | |||

| 1 | 1399 (20·6%) | 643 (21·0%) | 756 (20·2%) |

| 2 | 1373 (20·2%) | 633 (20·7%) | 740 (19·8%) |

| 3 | 1304 (19·2%) | 571 (18·6%) | 733 (19·6%) |

| 4 | 1311 (19·3%) | 593 (19·3%) | 718 (19·2%) |

| 5 | 1417 (20·8%) | 625 (20·4%) | 792 (21·2%) |

Data are n (%). IMD=Index of Multiple Deprivation.

IMD quintiIe 1 represents most deprived and quintile 5 represents least deprived.

At the time of testing, 1084 (35·4%) of 3065 adolescents who tested positive and 309 (8·3%) of 3739 who tested negative reported having had any symptoms; 936 (30·5%) of those who tested positive and 231 (6·2%) of those who tested negative had at least three symptoms and 726 (23·7%) who tested positive and 143 (3·8%) who tested negative had at least five symptoms. Because differences between adolescents who tested positive and those who tested negative become more striking for multiple symptoms than for a single symptom, we use three or more symptoms and five or more symptoms for illustrative purposes (table 3). The most common symptoms among adolescents who tested positive were sore throat, headache, tiredness, and loss of smell and among those who tested negative were sore throat, headache, fever, and persistent cough. The prevalence of symptoms varied by SARS-CoV-2 status (eg, headaches were reported by 806 [26·3%] of those who tested positive compared to 178 [4·8%] of those who tested negative). Of note, prevalence of pre-existing morbidity (eg, asthma) were broadly similar in participants positive and negative for SARS-CoV-2 (appendix p 19).

Table 3.

Reported symptoms at the time of test, and physical and mental health before test, by SARS-CoV-2 status, overall and stratified by age group

|

All participants |

Participants aged 11–14 years |

Participants aged 15–17 years |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 (n=3065) | Tested negative for SARS-CoV-2 (n=3739) | Tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 (n=1244) | Tested negative for SARS-CoV-2 (n=1609) | Tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 (n=1821) | Tested negative for SARS-CoV-2 (n=2130) | ||

| No reported symptoms | 1981 (64·6%) | 3430 (91·7%) | 830 (66·7%) | 1450 (90·1%) | 1151 (63·2%) | 1980 (93·0%) | |

| 1 symptom | 60 (2·0%) | 35 (0·9%) | 32 (2·6%) | 22 (1·4%) | 28 (1·5%) | 13 (0·6%) | |

| 2 symptoms | 88 (2·9%) | 43 (1·2%) | 45 (3·6%) | 29 (1·8%) | 43 (2·4%) | 14 (0·7%) | |

| 3 symptoms | 101 (3·3%) | 52 (1·4%) | 50 (4%) | 29 (1·8%) | 51 (2·8%) | 23 (1·1%) | |

| 4 symptoms | 109 (3·6%) | 36 (1·0%) | 56 (4·5%) | 15 (0·9%) | 53 (2·9%) | 21 (1·0%) | |

| ≥5 symptoms | 726 (23·7%) | 143 (3·8%) | 231 (18·6%) | 64 (4·0%) | 495 (27·2%) | 79 (3·7%) | |

| Specific symptoms | |||||||

| Fever | 548 (17·9%) | 148 (4·0%) | 195 (15·7%) | 76 (4·7%) | 353 (19·4%) | 72 (3·4%) | |

| Chills | 461 (15·0%) | 91 (2·4%) | 154 (12·4%) | 40 (2·5%) | 307 (16·9%) | 51 (2·4%) | |

| Persistent cough | 476 (15·5%) | 143 (3·8%) | 149 (12·0%) | 67 (4·2%) | 327 (18%) | 76 (3·6%) | |

| Tiredness | 696 (22·7%) | 125 (3·3%) | 233 (18·7%) | 57 (3·5%) | 463 (25·4%) | 68 (3·2%) | |

| Shortness of breath | 354 (11·5%) | 56 (1·5%) | 83 (6·7%) | 19 (1·2%) | 271 (14·9%) | 37 (1·7%) | |

| Loss of smell | 631 (20·6%) | 55 (1·5%) | 210 (16·9%) | 24 (1·5%) | 421 (23·1%) | 31 (1·5%) | |

| Unusually hoarse voice | 145 (4·7%) | 41 (1·1%) | 42 (3·4%) | 16 (1·0%) | 103 (5·7%) | 25 (1·2%) | |

| Unusual chest pain | 280 (9·1%) | 57 (1·5%) | 71 (5·7%) | 13 (0·8%) | 209 (11·5%) | 44 (2·1%) | |

| Unusual abdominal pain | 138 (4·5%) | 44 (1·2%) | 55 (4·4%) | 21 (1·3%) | 83 (4·6%) | 23 (1·1%) | |

| Diarrhoea | 166 (5·4%) | 41 (1·1%) | 52 (4·2%) | 20 (1·2%) | 114 (6·3%) | 21 (1%) | |

| Headaches | 806 (26·3%) | 178 (4·8%) | 306 (24·6%) | 86 (5·3%) | 500 (27·5%) | 92 (4·3%) | |

| Confusion, disorientation, or drowsiness | 225 (7·3%) | 29 (0·8%) | 53 (4·3%) | 9 (0·6%) | 172 (9·4%) | 20 (0·9%) | |

| Unusual eye-soreness | 185 (6·0%) | 30 (0·8%) | 56 (4·5%) | 13 (0·8%) | 129 (7·1%) | 17 (0·8%) | |

| Skipping meals | 360 (11·7%) | 67 (1·8%) | 103 (8·3%) | 23 (1·4%) | 257 (14·1%) | 44 (2·1%) | |

| Dizziness or light-headedness | 462 (15·1%) | 86 (2·3%) | 133 (10·7%) | 33 (2·1%) | 329 (18·1%) | 53 (2·5%) | |

| Sore throat | 687 (22·4%) | 200 (5·4%) | 241 (19·4%) | 98 (6·1%) | 446 (24·5%) | 102 (4·8%) | |

| Unusually strong muscle pains | 338 (11·0%) | 45 (1·2%) | 99 (8·0%) | 17 (1·1%) | 239 (13·1%) | 28 (1·3%) | |

| Earache or ringing in ears | 155 (5·1%) | 41 (1·1%) | 44 (3·5%) | 11 (0·7%) | 111 (6·1%) | 30 (1·4%) | |

| Raised welts on skin or swelling | 35 (1·1%) | 7 (0·2%) | 14 (1·1%) | 3 (0·2%) | 21 (1·2%) | 4 (0·2%) | |

| Red or purple sores or blisters on feet | 21 (0·7%) | 9 (0·2%) | 7 (0·6%) | 5 (0·3%) | 14 (0·8%) | 4 (0·2%) | |

| Other | 73 (2·4%) | 17 (0·5%) | 29 (2·3%) | 13 (0·8%) | 44 (2·4%) | 4 (0·2%) | |

| Health before test* | |||||||

| Very poor or poor | 66 (2·2%) | 81 (2·2%) | 14 (1·1%) | 22 (1·4%) | 52 (2·9%) | 59 (2·8%) | |

| Okay | 670 (21·9%) | 800 (21·4%) | 223 (17·9%) | 281 (17·5%) | 447 (24·5%) | 519 (24·4%) | |

| Good or very good | 2329 (76·0%) | 2858 (76·4%) | 1007 (80·9%) | 1306 (81·2%) | 1322 (72·6%) | 1552 (72·9%) | |

| Previous mental health* | |||||||

| Very poor or poor | 279 (9·1%) | 362 (9·7%) | 60 (4·8%) | 84 (5·2%) | 219 (12%) | 278 (13·1%) | |

| Okay | 901 (29·4%) | 1065 (28·5%) | 265 (21·3%) | 341 (21·2%) | 636 (34·9%) | 724 (34%) | |

| Good or very good | 1885 (61·5%) | 2312 (61·8%) | 919 (73·9%) | 1184 (73·6%) | 966 (53·1%) | 1128 (53·0%) | |

Data are n (%).

Participants were asked to rate their physical and mental health before their SARS-CoV-2 test in two separate questions using a five-category Likert scale; for analysis, we recorded these variables into three categories (very poor and poor, okay, and good and very good).

3 months after testing, the presence of physical symptoms had increased in both groups: 2038 (66·5%) of those who tested positive and 1993 (53·3%) of those who tested negative had symptoms of any kind, 928 (30·3%) of those who tested positive and 603 (16·2%) of those who tested negative had at least three symptoms, and 411 (13·4%) of those who tested positive and 238 (6·4%) of those who tested negative had at least five symptoms (table 4). The most common symptoms among those who tested positive were tiredness, headache, and shortness of breath, and, among those who tested negative, were tiredness, headache, and the unspecified category of other. Again, the prevalence of tiredness and headache was consistently higher in those who tested positive (1196 [39·0%] for tiredness and 710 [23·2%] for headaches) than those who tested negative (911 [24·4%] for tiredness and 530 [14·2%] for headaches). For both the group who tested positive and the group who tested negative, prevalence of most symptoms was higher for adolescents aged 15–17 years than those aged 11–14 years; for example, 818 (44·9%) of those aged 15–17 years who tested positive reported being tired compared with 378 (30·4%) of adolescents aged 11–14 years who tested positive. When we reweighted the percentage of reported symptoms at baseline and at 3 months post-test, broadly similar patterns were observed to those reported above (appendix pp 19–21). When we compared reasons for testing, the majority of adolescents who tested negative were identified via school surveillance (2658 [71·1%]) versus only 793 (25·9%) of those who tested positive (appendix p 21). Apart from age, no systematic differences were observed in demographic characteristics across reasons for testing (appendix p 22).

Table 4.

Reported symptoms at 3 months by SARS-CoV-2 status, overall and stratified by age group

|

All participants |

Participants aged 11–14 years |

Participants aged 15–17 years |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 (n=3065) | Tested negative for SARS-CoV-2 (n=3739) | p value* | Tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 (n=1244) | Tested negative for SARS-CoV-2 (n=1609) | p value* | Tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 (n=1821) | Tested negative for SARS-CoV-2 (n=2130) | p value* | ||

| No reported symptoms | 1027 (33·5%) | 1746 (46·7%) | <0·0001 | 492 (39·5%) | 845 (52·5%) | <0·0001 | 535 (29·4%) | 901 (42·3%) | <0·0001 | |

| 1 symptom | 671 (21·9%) | 1019 (27·3%) | .. | 293 (23·6%) | 436 (27·1%) | .. | 378 (20·8%) | 583 (27·4%) | .. | |

| 2 symptoms | 439 (14·3%) | 371 (9·9%) | .. | 167 (13·4%) | 123 (7·6%) | .. | 272 (14·9%) | 248 (11·6%) | .. | |

| 3 symptoms | 300 (9·8%) | 228 (6·1%) | .. | 91 (7·3%) | 68 (4·2%) | .. | 209 (11·5%) | 160 (7·5%) | .. | |

| 4 symptoms | 217 (7·1%) | 137 (3·7%) | .. | 70 (5·6%) | 51 (3·2%) | .. | 147 (8·1%) | 86 (4·0%) | .. | |

| ≥5 symptoms | 411 (13·4%) | 238 (6·4%) | .. | 131 (10·5%) | 86 (5·3%) | .. | 280 (15·4%) | 152 (7·1%) | .. | |

| Specific symptoms | ||||||||||

| Fever | 50 (1·6%) | 55 (1·5%) | 0·59 | 9 (0·7%) | 18 (1·1%) | 0·28 | 41 (2·3%) | 37 (1·7%) | 0·25 | |

| Chills | 269 (8·8%) | 192 (5·1%) | <0·0001 | 96 (7·7%) | 88 (5·5%) | 0·015 | 173 (9·5%) | 104 (4·9%) | <0·0001 | |

| Persistent cough | 98 (3·2%) | 98 (2·6%) | 0·16 | 35 (2·8%) | 41 (2·5%) | 0·66 | 63 (3·5%) | 57 (2·7%) | 0·15 | |

| Tiredness | 1196 (39·0%) | 911 (24·4%) | <0·0001 | 378 (30·4%) | 277 (17·2%) | <0·0001 | 818 (44·9%) | 634 (29·8%) | <0·0001 | |

| Shortness of breath | 717 (23·4%) | 388 (10·4%) | <0·0001 | 202 (16·2%) | 135 (8·4%) | <0·0001 | 515 (28·3%) | 253 (11·9%) | <0·0001 | |

| Loss of smell | 414 (13·5%) | 51 (1·4%) | <0·0001 | 145 (11·7%) | 12 (0·7%) | <0·0001 | 269 (14·8%) | 39 (1·8%) | <0·0001 | |

| Unusually hoarse voice | 56 (1·8%) | 46 (1·2%) | 0·044 | 21 (1·7%) | 20 (1·2%) | 0·32 | 35 (1·9%) | 26 (1·2%) | 0·075 | |

| Unusual chest pain | 216 (7·0%) | 129 (3·5%) | <0·0001 | 61 (4·9%) | 46 (2·9%) | 0·0044 | 155 (8·5%) | 83 (3·9%) | <0·0001 | |

| Unusual abdominal pain | 119 (3·9%) | 107 (2·9%) | 0·019 | 43 (3·5%) | 33 (2·1%) | 0·021 | 76 (4·2%) | 74 (3·5%) | 0·25 | |

| Diarrhoea | 92 (3·0%) | 80 (2·1%) | 0·024 | 35 (2·8%) | 29 (1·8%) | 0·071 | 57 (3·1%) | 51 (2·4%) | 0·16 | |

| Headaches | 710 (23·2%) | 530 (14·2%) | <0·0001 | 258 (20·7%) | 174 (10·8%) | <0·0001 | 452 (24·8%) | 356 (16·7%) | <0·0001 | |

| Confusion, disorientation, or drowsiness | 198 (6·5%) | 123 (3·3%) | <0·0001 | 61 (4·9%) | 43 (2·7%) | 0·0016 | 137 (7·5%) | 80 (3·8%) | <0·0001 | |

| Unusual eye-soreness | 182 (5·9%) | 134 (3·6%) | <0·0001 | 55 (4·4%) | 49 (3·0%) | 0·052 | 127 (7·0%) | 85 (4·0%) | <0·0001 | |

| Skipping meals | 296 (9·7%) | 275 (7·4%) | 0·0007 | 84 (6·8%) | 91 (5·7%) | 0·23 | 212 (11·6%) | 184 (8·6%) | 0·0017 | |

| Dizziness or light-headedness | 419 (13·7%) | 314 (8·4%) | <0·0001 | 123 (9·9%) | 104 (6·5%) | 0·0008 | 296 (16·3%) | 210 (9·9%) | <0·0001 | |

| Sore throat | 291 (9·5%) | 281 (7·5%) | 0·0034 | 129 (10·4%) | 107 (6·7%) | 0·0004 | 162 (8·9%) | 174 (8·2%) | 0·41 | |

| Unusually strong muscle pains | 165 (5·4%) | 83 (2·2%) | <0·0001 | 56 (4·5%) | 29 (1·8%) | <0·0001 | 109 (6·0%) | 54 (2·5%) | <0·0001 | |

| Earache or ringing in ears | 191 (6·2%) | 165 (4·4%) | 0·0008 | 72 (5·8%) | 71 (4·4%) | 0·10 | 119 (6·5%) | 94 (4·4%) | 0·0032 | |

| Raised welts on skin or swelling | 48 (1·6%) | 32 (0·9%) | 0·0069 | 22 (1·8%) | 15 (0·9%) | 0·050 | 26 (1·4%) | 17 (0·8%) | 0·057 | |

| Red or purple sores or blisters on feet | 35 (1·1%) | 40 (1·1%) | 0·78 | 14 (1·1%) | 17 (1·1%) | 0·86 | 21 (1·2%) | 23 (1·1%) | 0·83 | |

| Other | 335 (10·9%) | 590 (15·8%) | <0·0001 | 145 (11·7%) | 280 (17·4%) | <0·0001 | 190 (10·4%) | 310 (14·6%) | 0·0001 | |

p values need to be considered after correcting for multiple testing using a Bonferroni adjustment (number of tests=66; ie, p<0·05 corresponds to p<0·000758 and p<0·01 corresponds to p<0·000152).

There was no difference in the distribution of mental health scores (assessed by the SDQ total difficulties scores) and wellbeing (assessed by SWEMWBS) between those who tested positive and those who tested negative for SARS-CoV-2. The SDQ median was 9 (IQR 5–14) for adolescents aged 11–14 years in both the test-positive and test-negative groups and 12 (7–16) for adolescents aged 15–17 years in both test groups. SWEMWBS scores did not vary by age and mean scores were similar among those who tested positive (21·5; SD 4·3) and those who tested negative (21·4; SD 4·3). Mean fatigue scores were not substantially different between those who tested positive (13·3; SD 5·2) and those who tested negative (12·5; SD 5·1), with slightly higher fatigue scores in older participants across both test groups. EQ-5D-Y scores, representing health-related quality of life, showed that adolescents who tested positive in both age groups were more likely to report problems with mobility, doing usual activities, and pain or discomfort than those who tested negative, and younger adolescents who tested positive were more likely to be worried or sad than younger adolescents who tested negative (appendix p 25). Strikingly, 1251 (40·8%) of participants who tested positive and 1467 (39·2%) who tested negative and felt worried, sad, or unhappy, as indicated on a single item of the EQ-5D-Y.

At baseline, there was no evidence of clustering of physical symptoms in either those who tested positive or those who tested negative. By contrast, there was evidence of clustering of physical symptoms reported at 3 months, with two subgroups emerging for both test groups (appendix pp 26–27). In each, the largest subgroup (class 1) had very low prevalence of most physical symptoms, and the second subgroup (class 2) was characterised in both test groups by multiple symptoms dominated by tiredness, headache, shortness of breath, and dizziness. We refer to these classes as few and multiple symptoms classes. The estimated probability (risk) of being in the multiple symptom class (class 2) was 29·6% (95% CI 27·4–31·7) for those who tested positive and 19·3% (17·7–21·0) for those who tested negative, and the risk ratio of being in class 2 versus class 1 comparing those who tested positive to those who tested negative was 1·53 (95% CI 1·35–1·70).

For both test groups, those assigned to the multiple symptoms class 2 at 3 months were more likely to be girls, older, and have very poor or poor baseline physical and mental health (appendix pp 23–24). At 3 months, adolescents assigned to class 2 were more likely to have worse mental health and wellbeing as shown by higher scores on all five items of the EQ-5D-Y scale, generally higher SDQ (total difficulties and each subscale) and CFS scores, and lower SWEMWBS scores (appendix p 24).

Discussion

Without a definition of long COVID, we elected not to ask about self-reported long COVID. This study describes adolescent-reported symptoms during their acute illness and 3 months after PCR-proven SARS-CoV-2 infection, with a PCR-negative comparison group and standardised mental health, well-being, and fatigue instruments.

Important findings are, first, 3 months after the SARS-CoV-2 test, the presence of physical symptoms was higher than at the time of testing, emphasising the importance of having a comparison group to interpret the findings. Although 1981 (64·6%) of adolescents testing positive reported no symptoms at time of testing (compared to 3430 [91·7%] of adolescents who tested negative), only 1027 (33·5%) of those who tested positive (and 1746 [46·7%] of those who tested negative) reported no symptoms at 3 months. This finding could be due to self-selection, recall bias for symptoms at the time of testing, or returning to school from March, 2021, following national lockdown from January, 2021, with exposure to other infections.

Second, symptoms reported at time of testing did not distinguish those who tested positive (sore throat, headache, tiredness, and loss of smell) from those who tested negative (sore throat, headache, fever, and persistent cough), potentially because national testing was primarily targeted for those with fever, new-onset cough, and loss of taste or smell. However, the two groups could be separated according to the number of symptoms at 3 months, when 928 (30·3%) of participants who tested positive and 603 (16·2%) of participants who tested negative had 3 or more symptoms. Consideration of number of symptoms is particularly important given that 1993 (53·3%) of the participants who tested negative had at least one symptom 3 months after the test. These figures should be interpreted against published prepandemic norms: 255 (30%) of 842 adolescents aged 11–15 years reported fatigue over a 4–6-month prepandemic period;19 a cross-sectional survey reported 1587 (19·9%) of 7977 adolescents to have headache, fatigue, or asthma.20

Third, for test groups, those assigned to the latent class with multiple symptoms at 3 months were more likely to be female, older, and have poorer physical and mental health before COVID-19, suggesting that pre-existing physical and mental health difficulties might influence symptoms at 3 months. Unsurprisingly, regardless of test status, those with multiple physical symptoms at 3 months after the test concurrently had poorer mental health, reflecting the close relationship between physical and mental health.

Fourth, although the prevalence of physical symptoms differed between test groups, mental health, wellbeing, and fatigue scores were similar. However, a large proportion (approximately 40%) in both groups reported feeling worried, sad, or unhappy, consistent with parent-reported surveys of mental health of children and young people during the pandemic.21, 22 The findings emphasise the importance of incorporating a comparator-matched cohort of participants who tested negative and also experienced a pandemic, school closures, and social isolation. Our findings suggest that any definition of long COVID should consider multiple symptoms that affect functioning and recognise different clusters of symptoms.23

Finally, given the multiple symptoms at 3 months, a multicomponent intervention will be required to manage adolescents with long COVID, building on existing management of symptoms such as chronic fatigue and headaches.24 The most common symptoms at 3 months among those who tested positive of tiredness, headache, shortness of breath, dizziness, and anosmia are consistent with other studies in young people,1, 7 which also identified higher symptom prevalence in girls than boys, adolescents than younger children, and children with long-term conditions than those without.1

We show that mental and physical health symptoms are related. Stress might manifest as somatic symptoms,25 and persisting physical symptoms might be associated with depression and anxiety. Family approaches to managing continuing symptoms are key,26 as is the negative effect of protracted medical investigations and treatments.25

This study has limitations, including the cross-sectional nature of this initial questionnaire 3 months after testing. The questionnaire will be resent at 6, 12, and 24 months after testing. Although the study design is prospective, the data on symptoms at the time of PCR testing were retrospective and hence prone to recall bias. Some symptoms might have been present before SARS-COV-2 infection. Participants did not report the severity of symptoms and although the number of symptoms could serve as a proxy of overall illness severity, a single severe symptom might be more disabling than several mild symptoms. The EQ-5D-Y is one indicator of severity because it assesses the effect on daily living. It is possible that some participants might have been misdiagnosed as SARS-CoV-2 negative and vice versa. False negatives might be attributable to the timing of the PCR, swab technique, and assay sensitivity, but false-positive PCR results are rare. We could not recruit or match on ethnicity, medical history, or testing location (as not recorded in PHE database at testing) but subsequent self-reported ethnicity was very similar in both test groups and geographical address served as a proxy for socioeconomic status; both are potentially important variables in long COVID.27 We did not assess physical symptom severity at the time of testing or 3 months after testing. We used established scales to measure mental health,11 wellbeing,12, 13 and fatigue,14 but acknowledge the limitations of self-reporting and floor and ceiling effects (ie, if the tests or scales are relatively easy or difficult such that substantial proportions of individuals obtain either maximum or minimum scores and that the true extent of their abilities cannot be determined).

6804 (13·4%) of 50 846 adolescents responded to our survey, which is comparable to other COVID-19 related studies. The UK Office for National Statistics (ONS) studies had an enrolment rate of 12% between July, 2020, and November, 2021, when sampling randomly.28 The REACT 2 study had a 30% response rate for adults randomly selected from the NHS patient lists despite being offered a free antibody test delivered to their home.29 We cannot deduce how representative the 6804 respondents were of the 23 048 young people who tested positive and the 27 798 who tested negative that we approached, other than in terms of age, sex, geographical region, and IMD quintiles, because only NHS number, name, age, sex, and postcode were recorded in the PHE database. We can consider a sensitivity analysis of two scenarios. Between Sept 1, 2020, and March 31, 2021, 234 803 people aged 11–17 years tested positive for SARS-CoV-2. If our 13% of respondents are representative of all people aged 11–17 years who tested positive, then across England 70 441 adolescents would have at least three physical symptoms, 3 or more months after a positive test and 30 524 would have at least five physical symptoms. How many of these are attributable to SARS-CoV-2 infection over and above the background symptom levels in adolescents who tested negative? The excess is 32 872 (1 in 7, or 14% of 234 803) with three or more physical symptoms and 16 436 (1 in 14, or 7%) with five or more physical symptoms.

The ONS estimated the percentage of young people in England with self-reported long COVID of any duration as 0·51% for those aged 12–16 years and 1·21% for those aged 17–24 years, equating to 31 080 aged 11–17 years across England.7 Despite differences in definitions and methodology, this figure is very similar to our figure of 32 872 young people aged 11–17 years with three or more persisting physical symptoms attributable to SARS-CoV-2.

However, if our 13% of responders are entirely unrepresentative and the 87% of non-responders had completely recovered, then 9157 of the 234 803 adolescents aged 11–17 years who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 would have at least three physical symptoms 3 or more months after a positive test and 3968 would have five or more physical symptoms. The number attributable to SARS-CoV-2 infection over and above the background symptom levels in adolescents aged 11–17 years who test negative is 4273 (1 in 50, or 1·8% of 234 803) with three or more physical symptoms and 2137 with five or more physical symptoms (1 in 100, or 0·9% of 234 803). Both scenarios indicate the additional risk of multiple symptoms at least 3 months after a SARS-CoV-2 positive test is much less than the 51% feared, on the basis of some previous studies (appendix pp 16–18).

Another limitation is that we did not assess whether symptoms were intermittent or continuous for the entire 3 months. Finally, the experiences of adolescents were likely to vary depending on whether they were in lockdown or attending school at the time. At the time of PCR testing schools were closed, but at 3 months after testing, schools had reopened albeit with social distancing, repeated testing, and restriction of activities.

Our findings reflect a period when the alpha variant was predominant in the UK. The rate of continuing post-COVID symptoms might change with different variants. In summary, our research shows the importance of having a test-negative comparison group to interpret findings, that it is essential to consider multiple symptoms in the phenotype of long COVID, that mental and physical health symptoms should both be considered, and that adolescents with PCR-proven SARS-CoV-2 had a higher frequency of any symptoms, and multiple physical symptoms, 3 months after testing than adolescents who tested negative.

For more on LSOA see https://datadictionary.nhs.uk/nhs_business_definitions/lower_layer_super_output_area.html

Data sharing

Data are not publicly available. All requests for data will be reviewed by the Children & young people with Long Covid (CLoCk) study team, to verify whether the request is subject to any intellectual property or confidentiality obligations. Requests for access to the participant-level data from this study can be submitted via email to clock@phe.gov.uk with detailed proposals for approval. A signed data access agreement with the CLoCK team is required before accessing shared data. Code is not made available as we have not used custom code or algorithms central to our conclusions.

Declaration of interests

TS is Chair of the Health Research Authority and therefore recused himself from the research ethics application. TC is a member of the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence committee for long COVID. She has written self-help books on chronic fatigue and has done workshops on chronic fatigue and post infectious syndromes. All other authors declare no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Michael Lattimore, Public Health England, as Project Officer for the CLoCk study. This study was funded by The Department of Health and Social Care, in their capacity as the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), and by UK Research and Innovation (UKRI) who have awarded funding grant number COVLT0022. All research at Great Ormond Street Hospital NHS Foundation Trust and UCL Great Ormond Street Institute of Child Health is made possible by the NIHR Great Ormond Street Hospital Biomedical Research Centre. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR, UKRI, or the Department of Health. SMPP is supported by a UK Medical Research Council Career Development Award (MR/P020372/1).

Contributors

TS conceived the idea for the study and submitted the successful grant application. TS and RSh decided to submit the manuscript. TS, SMPP, RSh, and BLdS drafted the manuscript. SMPP did the statistical analyses for the manuscript. SMPP, BLdS, and RSi accessed and verified the data. RSh provided ideas on mental health to the original grant application and submitted the ethics and research and development applications. BLdS provided statistical input to the design and did the analyses, including sample size calculations. NR supported the drafting of the manuscript and the statistical analyses. KM adapted the questionnaire for the online SNAP survey platform. RSi designed the participant sampling and dataflow. MZ undertook a separate pilot study that informed the CLoCk consent process and the online questionnaire. LO'M contributed to the scoping review of the literature. TC and IH contributed to the work on psychiatric liaison. EC contributed to the work on chronic fatigue and contributed to the manuscript. EC, TJF, AH, IH, OS, and EW reviewed the manuscript. TJF contributed to the work on epidemiology, schools, and mental health. AH contributed to the work on primary care. OS and EW contributed to the work on infection and designed the elements of the ISARIC Paediatric COVID-19 follow-up questionnaire that were incorporated into the online questionnaire used in this study to which all the CLoCk Consortium members contributed. SNL developed the study methodology, operationalised the regulatory and recruitment ideas for the study, and revised the manuscript. All members of the CLoCk Consortium made contributions to the conception or design of the work and were involved in drafting both the funding application and this manuscript. All authors had full access to all the data in the study, had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Contributor Information

Terence Stephenson, Email: t.stephenson@ucl.ac.uk.

CLoCk Consortium:

Terence Stephenson, Roz Shafran, Marta Buszewicz, Trudie Chalder, Esther Crawley, Emma Dalrymple, Bianca L de Stavola, Tamsin Ford, Shruti Garg, Malcolm Semple, Dougal Hargreaves, Anthony Harnden, Isobel Heyman, Shamez Ladhani, Michael Levin, Vanessa Poustie, Terry Segal, Kishan Sharma, Olivia Swann, and Elizabeth Whittaker

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Molteni E, Sudre CH, Canas LS, et al. Illness duration and symptom profile in symptomatic UK school-aged children tested for SARS-CoV-2. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2021;5:708–718. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(21)00198-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sudre CH, Murray B, Varsavsky T, et al. Attributes and predictors of long COVID. Nat Med. 2021;27:626–631. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01292-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chevinsky JR, Tao G, Lavery AM, et al. Late conditions diagnosed 1-4 months following an initial coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) encounter: a matched-cohort study using inpatient and outpatient administrative data—United States, March 1–June 30, 2020. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;73(suppl 1):S5–16. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciab338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Spiegelhalter D, Masters A. Penguin Random House; UK: 2021. Covid by numbers: making sense of the pandemic with data. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davis HE, Assaf GS, McCorkell L, et al. Characterizing long COVID in an international cohort: 7 months of symptoms and their impact. EClinicalMedicine. 2021;38 doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.101019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Amin-Chowdhury Z, Ladhani SN. Causation or confounding: why controls are critical for characterizing long COVID. Nat Med. 2021;27:1129–1130. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01402-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Office for National Statistics Prevalence of ongoing symptoms following coronavirus (COVID-19) infection in the UK Statistical bulletins. 2021. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/conditionsanddiseases/bulletins/prevalenceofongoingsymptomsfollowingcoronaviruscovid19infectionintheuk/previousReleases

- 8.Stephenson T, Shafran R, De Stavola B, et al. Long COVID and the mental and physical health of children and young people: national matched cohort study protocol (the CLoCk study) BMJ Open. 2021;11 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-052838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ladhani SN, Baawuah F, Beckmann J, et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection and transmission in primary schools in England in June–December, 2020 (sKIDs): an active, prospective surveillance study. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2021;5:417–427. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(21)00061-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sigfrid L, Maskell K, Bannister PG, et al. Addressing challenges for clinical research responses to emerging epidemics and pandemics: a scoping review. BMC Med. 2020;18:190. doi: 10.1186/s12916-020-01624-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.NHS Digital Mental Health of Children and Young People in England, 2020: wave 1 follow up to the 2017 survey. 2020. https://tinyurl.com/NHSWave1FU

- 12.Goodman R. Psychometric properties of the strengths and difficulties questionnaire. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;40:1337–1345. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200111000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tennant R, Hiller L, Fishwick R, et al. The Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (WEMWBS): development and UK validation. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2007;5:63. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-5-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wille N, Badia X, Bonsel G, et al. Development of the EQ-5D-Y: a child-friendly version of the EQ-5D. Qual Life Res. 2010;19:875–886. doi: 10.1007/s11136-010-9648-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chalder T, Berelowitz G, Pawlikowska T, et al. Development of a fatigue scale. J Psychosom Res. 1993;37:147–153. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(93)90081-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McCutcheon AC. Sage; Beverly Hills, CA, USA: 1987. Latent class analysis. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vandenbroucke JP, von Elm E, Altman DG, et al. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE): explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:W163–W194. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-8-200710160-00010-w1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oehlert GW. A note on the delta method. Am Stat. 1992;46:27–29. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rimes KA, Goodman R, Hotopf M, Wessely S, Meltzer H, Chalder T. Incidence, prognosis, and risk factors for fatigue and chronic fatigue syndrome in adolescents: a prospective community study. Pediatrics. 2007;119:e603–e609. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-2231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Office for National Statistics Mental health of children and young people in Great Britain, 2004. 2004. https://files.digital.nhs.uk/publicationimport/pub06xxx/pub06116/ment-heal-chil-youn-peop-gb-2004-rep1.pdf

- 21.Creswell C, Shum A, Pearcey S, Skripkauskaite S, Patalay P, Waite P. Young people's mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2021;5:535–537. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(21)00177-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Skripkauskaite S, Shum A, Pearcey S, Raw J, Waite P, Creswell C. Report 08: changes in children's and young people's mental health symptoms: March 2020 to January 2021. 2021. https://cospaceoxford.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Report_08_17.02.21.pdf

- 23.Whitaker M, Elliott J, Chadeau-Hyam M, et al. Persistent symptoms following SARS-CoV-2 infection in a random community sample of 508,707 people. medRxiv. 2021 doi: 10.1101/2021.06.28.21259452. (preprint). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fisher E, Law E, Dudeney J, Palermo TM, Stewart G, Eccleston C. Psychological therapies for the management of chronic and recurrent pain in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;9 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003968.pub5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Willis C, Chalder T. Concern for Covid-19 cough, fever and impact on mental health. What about risk of Somatic Symptom Disorder? J Ment Health. 2021;30:551–555. doi: 10.1080/09638237.2021.1875418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.O'Connell K, Berluti K, Rhoads SA, Marsh AA. Reduced social distancing early in the COVID-19 pandemic is associated with antisocial behaviors in an online United States sample. PLoS One. 2021;16 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0244974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Patel P, Hiam L, Sowemimo A, Devakumar D, McKee M. Ethnicity and covid-19. BMJ. 2020;369 doi: 10.1136/bmj.m2282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Office for National Statistics Coronavirus (COVID-19) Infection Survey: technical data. 2021. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/conditionsanddiseases/datasets/covid19infectionsurveytechnicaldata

- 29.Ward H, Cooke GS, Atchison C, et al. Prevalence of antibody positivity to SARS-CoV-2 following the first peak of infection in England: serial cross-sectional studies of 365 000 adults. Lancet Reg Health Eur. 2021;4 doi: 10.1016/j.lanepe.2021.100098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data are not publicly available. All requests for data will be reviewed by the Children & young people with Long Covid (CLoCk) study team, to verify whether the request is subject to any intellectual property or confidentiality obligations. Requests for access to the participant-level data from this study can be submitted via email to clock@phe.gov.uk with detailed proposals for approval. A signed data access agreement with the CLoCK team is required before accessing shared data. Code is not made available as we have not used custom code or algorithms central to our conclusions.