Abstract

Mobile phone-delivered interventions have proven effective in improving glycemic control (HbA1c) in the short term among adults with type 2 diabetes (T2D). Family systems theory suggests engaging family/friend in adults’ diabetes self-care may enhance or sustain improvements. In secondary analysis from a randomized controlled trial (N=506), we examined intervention effects on HbA1c via change in diabetes-specific helpful and harmful family/friend involvement. We compared a text messaging intervention that did not target family/friend involvement (REACH), REACH plus family-focused intervention components targeting helpful and harmful family/friend involvement (REACH+FAMS), and a control condition. Over 6 months, both intervention groups experienced improvement in HbA1c relative to control, but at 12 months neither did. However, REACH+FAMS showed an indirect effect on HbA1c via change in helpful family/friend involvement at both 6 and 12 months while REACH effects were not mediated by family/friend involvement. Consistent with family systems theory, improvements in HbA1c mediated by improved family/friend involvement were sustained.

Keywords: family, social support, mediation, mobile health, type 2 diabetes

Introduction

Self-care is key to successful management of type 2 diabetes (T2D) and largely occurs within the social context of the individual (Bennich et al., 2017; Glasgow & Toobert, 1988; Nicklett, Heisler, Spencer, & Rosland, 2013; Rosland, Heisler, & Piette, 2012). Family and friends’ (referred to collectively as “family” throughout) involvement in diabetes management has positive and detrimental effects on diabetes management, depending on the valence of the involvement. Helpful family involvement includes actions that facilitate or at least do not get in the way of patients’ efforts to improve self-care, including shopping for healthy foods, making time for physical activity, and helping remember medications. More helpful family involvement is independently associated with better diabetes self-care and glycemic control cross-sectionally (Mayberry & Osborn, 2014; Rosland et al., 2008; Walker, Smalls, & Egede, 2015; Wen, Shepherd, & Parchman, 2004) and longitudinally (Nicklett et al., 2013; Nicklett & Liang, 2010). Alternatively, harmful family involvement creates barriers for the patient attempting to initiate better self-care and/or creates conflict as family members nag or exert social control over patients (Mayberry & Osborn, 2012) and is independently associated with worse self-care cross-sectionally (Henry, Rook, Stephens, & Franks, 2013; Stephens et al., 2013) and worse glycemic control (Hemoglobin A1c [HbA1c]) longitudinally (Mayberry, Berg, Greevy Jr, & Wallston, 2019). Further, harmful family involvement may be particularly problematic for individuals with additional stressors (Goins, Noonan, Gonzales, Winchester, & Bradley, 2017; Mayberry, Egede, Wagner, & Osborn, 2015) or vulnerabilities such as limited health literacy (Mayberry, Rothman, & Osborn, 2014). Helpful and harmful involvement can both occur within the same families. Attending to positive and negative aspects of family involvement in adults’ diabetes self-care simultaneously is critical for understanding the full social context in which patients are managing their diabetes (Mayberry, Harper, & Osborn, 2016; Mayberry & Osborn, 2014; Rosland, Heisler, Choi, Silveira, & Piette, 2010; Vongmany, Luckett, Lam, & Phillips, 2018).

Systematic reviews have reported mixed effects of family interventions on diabetes management (Baig, Benitez, Quinn, & Burnet, 2015; Torenholt, Schwennesen, & Willaing, 2014). In one systematic review, only three of ten included studies reported significant improvements in biological (e.g., HbA1c) and educational (e.g., diabetes knowledge) outcomes from family interventions (Torenholt et al., 2014). Another systematic review concluded that family interventions improved patient outcomes including diabetes knowledge, diabetes self-care, and perceived social support; however, only seven of the 19 studies that measured HbA1c reported significant post-intervention changes (Baig et al., 2015).

Family systems theory offers two key insights into the otherwise mixed findings of interventions targeting family involvement. First, according to family systems theory, when an individual initiates a behavior change to the family environment, such as increasing self-care for diabetes, the family reacts in ways that maintain or undermine the behavior (Whitchurch & Constantine, 2009). For example, family members could choose to cook meals within the dietary recommendations of the person with T2D which would maintain efforts towards healthful eating, or they may complain about changes to the menu which would undermine those efforts. Second, family systems theory posits that lasting change occurs through second-order or higher level change (Whitchurch & Constantine, 2009) which is when the family responds in ways that reinforce the individuals’ changes, creating a positive feedback loop. For example, when an individual initiates first-order change by making healthier diet choices, these changes are often not sustained. It is when the family responds with second-order change by incorporating the healthier choices into the family’s menu and grocery shopping that changes are maintained. This theory posits that without the family or social system responding in ways that reinforce the individuals’ changes, patients will have difficulty maintaining their efforts over time and are likely to regress to previous functioning that is reinforced by the unaltered family system and/or social system. Thus, for family interventions for diabetes self-care to be effective and improvements maintained, interventions must improve family involvement which serves to reinforce individuals’ behavior change, leading to sustained change.

However, there have not been many opportunities to test the hypotheses of family systems theory among adults with T2D. Most studies of family interventions use treatment as usual or print materials as a control group which eliminates the opportunity to compare family interventions to individually delivered interventions. Moreover, studies rarely measure changes in helpful family involvement which serves to reinforce individual-initiated behavioral changes (Torenholt et al., 2014). Very few interventions include specific content addressing harmful family involvement or assess if the intervention changes harmful family involvement (Baig et al., 2015).

Herein, we conducted a secondary analysis from a larger 3-arm randomized control trial (RCT) (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT02481596) (Nelson et al., 2018) which provides a unique opportunity to experimentally test the family systems theory hypothesis that individual changes combined with improvements in family involvement may lead to sustained intervention effects over time. All participants assigned to intervention received the Rapid Encouragement/Education And Communications for Health (REACH) intervention which consisted of automated text messages to promote diabetes self-care for 12 months. REACH content did not target family and friend involvement. Half of the participants who received the REACH intervention were randomly assigned to also receive family-focused components (FAMS; Family-focused Add-on to Motivate Self-care) for the first 6 months. FAMS is based on family systems theory and helps participants identify and build skills to increase helpful involvement and cope with or redirect harmful involvement (Mayberry et al., 2020). A priori analyses and outcomes from the study have been published (Mayberry et al., 2020; Nelson et al., 2021). In short, both intervention groups saw improvements in self-efficacy, medication adherence, and dietary behavior relative to controls at 6 months (Mayberry et al., 2020). Only participants assigned to receive the additional FAMS components reported improvements in family involvement (Mayberry et al., 2020). In addition, there was an overall intervention effect (both intervention arms combined) on HbA1c at 6 months, which was not significant at 12 months (Nelson et al., 2021). All outcomes followed a similar trajectory as HbA1c, with significant effects largest at 6 months (Nelson et al., 2021). Therefore, we focus on HbA1c here for simplicity as it is one outcome that reflects changes in multiple outcomes.

We hypothesized that HbA1c changes mediated by improved feedback (increased helpful and reduced or stable harmful involvement) from family and friends would be sustained, whereas changes not mediated by improved feedback would not be sustained. Specifically, we hypothesized REACH+FAMS would activate second-order change, as suggested by family systems theory, and lead to sustained HbA1c improvement through improved family involvement. In contrast, REACH improvements, which were not accompanied by improvements in the family context, would be less likely to be sustained. As intervention effects on HbA1c depended on baseline levels (Nelson et al., 2021), we also explored how baseline HbA1c impacted these hypotheses.

Methods

Participants

Adults (≥18 years) with T2D were recruited from Vanderbilt University Medical Center (VUMC) adult primary care clinics and surrounding community clinics from May 2016 to December 2017. Individuals needed to be prescribed at least one daily diabetes medication (oral, insulin, and/or noninsulin injectables), be responsible for taking their own medications, have a cell phone, and speak and read English to be eligible. Exclusion criteria included most recent HbA1c value <6.8% within the prior 12 months, auditory or communication limitations that would inhibit participation in phone calls, failing a brief cognitive screener, and inability to respond to a text message.

There were 2,091 participants approached and 1,244 screened. Of those screened, 511 were ineligible and 70% of those eligible enrolled (512/733). Six individuals were administratively withdrawn prior to randomization. The final sample was 506 individuals randomized. Average age was 56.0 years (SD = 9.5) and 54% were female. Over half the sample was non-White (53%), including 39% non-Hispanic Black and 6% Hispanic. The sample included individuals with lower socioeconomic status (SES): 42% had a high school degree or less education, 56% had annual incomes <$35,000, and 49% were uninsured or had only public insurance. Participants were randomized (2:1:1) to the control condition (N = 253), REACH (N = 127), or REACH+FAMS (N = 126), using optimal multivariate matching, resulting in balance on variables of interest including gender, race/ethnicity, SES, diabetes medication, medication adherence, and glycemic control. This process matches participants prior to randomization using baseline data and randomizes within matched pairs to ensure balance on important covariates (for more information on matching process, see (Nelson et al., 2021; Nelson et al., 2018)).

Procedure

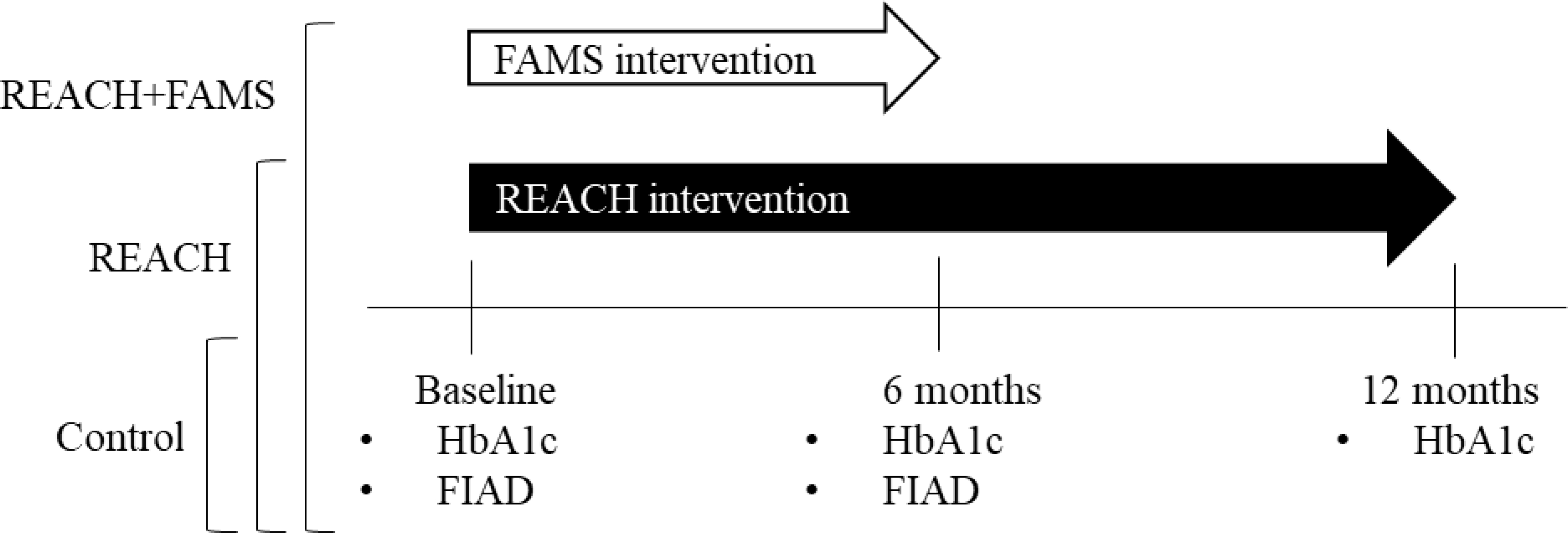

The Vanderbilt University Institutional Review Board approved all study procedures. All participants completed surveys and HbA1c tests at baseline and 6 months; in addition, participants completed an HbA1c test at 12 months. Surveys could be completed in-person at participants’ respective clinic or via phone, web, or mail, by preference. All participants received access to a helpline to ask questions about the study and their diabetes medications, text messages advising how to access study HbA1c results, and quarterly newsletters with information on living with diabetes. Control participants received usual care alongside what is described above. Participants assigned to REACH or REACH+FAMS received additional contacts, described below (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Diagram of conditions, interventions, and assessment timeline. Rapid Encouragement/Education And Communications for Health (REACH), Family-focused Add-on to Motivate Self-care (FAMS), Hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c), Family/Friend Involvement in Adult Diabetes (FIAD)

REACH Intervention.

The REACH intervention consists of daily automated text messages that promote self-care (one-way messages, e.g. “Even if you don’t think it is helping you now, your future health depends on taking your medicines every day”), and ask about medication adherence (interactive messages, e.g. “Did you take all of your diabetes meds today, [date]? Please reply Y or N.”). A weekly text provided feedback and encouragement based on responses to interactive messages for 12 months (Nelson et al., 2021). The intervention content targeted medication adherence and other self-care behaviors (i.e. diet, exercise, self-monitoring of blood glucose) and did not target family/friend involvement.

FAMS Intervention.

The FAMS intervention is based on family systems theory and designed as an additive to REACH (Mayberry et al., 2020; Mayberry, Berg, Harper, & Osborn, 2016). Specifically, participants assigned to REACH+FAMS received monthly phone coaching (20–30 minute long calls) and the option to invite an adult support person to receive text messages for the first 6 months. They received the same text messages as REACH participants, but the one-way messages addressing other self-care behaviors were replaced with one-way messages tailored to the goals they set in coaching (e.g. Your goal was to walk 15 minutes 4 days. How many days did you meet this goal last week (Sun-Sat)? Reply with the number of days, 0–7.). REACH+FAMS participants received one additional text each week, which assessed their goal progress and provided feedback based on their response. Phone coaching focused on setting diet or physical activity goals, identifying families’ actions that support or inhibit self-care goals and increasing skills to ask for needed support and/or manage harmful actions. About half (47%) of REACH+FAMS participants invited a support person and 42% had a support person enroll in the study. Support person text messages were designed to increase dialogue and support for patients’ self-care goals.

Measures

Sociodemographic characteristics.

Participants self-reported age, race/ethnicity, income, and insurance information.

Family/Friend Involvement in Adult Diabetes.

Participants also competed the helpful and harmful subscales of the Family/Friend Involvement in Adult Diabetes (FIAD)(Mayberry et al., 2019). Participants respond to each item on a scale from 1 “never in the past month” to 5 “twice or more in each week.” The helpful subscale includes nine items that assess received support for diabetes (e.g. “How often do your friends or family members exercise with you or ask you to exercise with them?”). The harmful subscale includes seven items that assess lack of support for diabetes (e.g. “How often do your friends or family members bring foods around that you shouldn’t be eating?”). Responses to items for each subscale are averaged. In prior studies, both subscales were associated with diabetes self-care behaviors and glycemic control (Mayberry et al., 2019). Reliability in the present sample was good for the helpful subscale (Cronbach’s α = .87) and acceptable for the harmful subscale (α = .63).

Hemoglobin A1c.

Hemoglobin A1c was collected via venipuncture or point-of-care by patients’ clinics. Otherwise, participants were provided with an HbA1c kit analyzed by CoreMedica Laboratories (Lee’s Summit, MO), which have been validated against venipuncture (Fokkema et al., 2009). Across the timepoints included in this study, 58% of HbA1c values were collected via venipuncture, 34% were collected via HbA1c kit, and 7% were point-of-care.

Data Analyses

Self-report measures were completed by 92% of the randomized sample at 6 months. Likewise, HbA1c data was available for 90.3% of the randomized sample at 6 and 12 months. Multiple imputation with chained equations accounted for missing data (m=20 imputed datasets). All models were conducted in Stata following procedures of the PROCESS macro, which is an ordinary least squares path analysis modeling tool capable of modeling multiple mediators simultaneously (Hayes, 2009; Preacher & Hayes, 2004). The randomized study design allowed us to conduct a causal mediation analysis (Preacher, 2015) to test change in helpful and harmful family involvement during the first 6 months of the intervention period (when the REACH+FAMS group experienced the FAMS components) as mediators of HbA1c at 6 and 12 months. Change in helpful and harmful involvement was calculated as a difference score between 6 month and baseline values. Separate models were tested comparing REACH+FAMS versus control and REACH versus control. Due to the 2:1:1 randomization design of the larger study, comparing the intervention groups with the control group has more power than comparing the intervention groups to one another. Models were adjusted for baseline HbA1c to enhance precision and handle any potential confounding not accounted for by randomization. As a result, effects on 6-month and 12-month HbA1c can be interpreted as change in HbA1c. Indirect effects were estimated with 3000 bootstrap samples and unstandardized mean changes are reported below.

To investigate the impact of baseline HbA1c on these models, we re-ran the same models as described above, but divided the sample into low (HbA1c <8.5%) and high (HbA1c ≥ 8.5%) baseline glycemic control, based on prior observed interaction effects in this data (Nelson et al., 2021). Due to lower power for these models, point estimates and confidence intervals are presented instead of p values.

Results

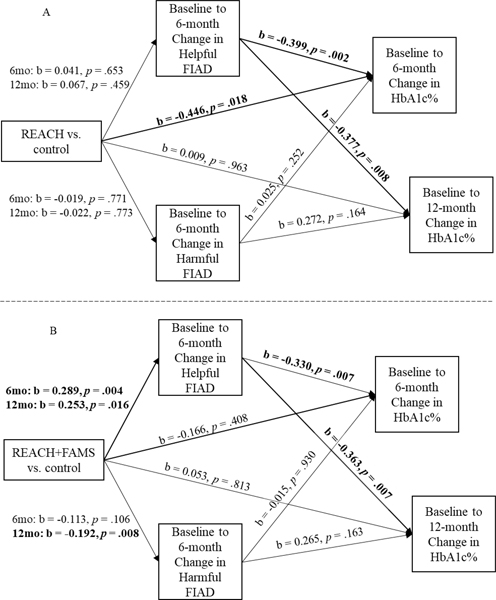

REACH had total and direct effects on 6-month HbA1c but not 12-month HbA1c (Table 1) and increased helpful family involvement during the first 6 months was related to improved HbA1c (Figure 2A) at both 6 and 12 months. However, because the REACH intervention did not improve family involvement, there was no evidence of mediation through family involvement on 6- or 12-month HbA1c in the group receiving REACH only (i.e., no significant indirect effects, Table 1).

Table 1.

Full Sample Total, Direct, and Indirect Effects

| Outcome | N | Total Effect | Direct Effect | Bootstrapped Indirect Effect | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||||

| b | p | b | p | b | 95% CI | ||

|

| |||||||

|

REACH vs. Control

|

|||||||

| 6-month HbA1c | 339 | −0.47 | .015 | −0.45 | .018 | −0.03 | [−0.13, 0.04] |

| via helpful involvement | −0.03 | [−0.13, 0.05] | |||||

| via harmful involvement | 0.00 | [−0.06, 0.02] | |||||

| 12-month HbA1c | 343 | −0.023 | .913 | 0.009 | .963 | −0.05 | [−0.15, 0.03] |

| via helpful involvement | −0.04 | [−0.15, 0.03] | |||||

| via harmful involvement | 0.00 | [−0.07, 0.03] | |||||

|

|

|||||||

|

REACH+FAMS vs. Control

|

|||||||

| 6-month HbA1c | 338 | −0.26 | .188 | −0.17 | .408 | −0.10 | [−0.25, −0.01] |

| via helpful involvement | −0.10 | [−0.24, −0.03] | |||||

| via harmful involvement | 0.00 | [−0.04, 0.06] | |||||

| 12-month HbA1c | 338 | −0.09 | .674 | 0.05 | .813 | −0.18 | [−0.35, −0.04] |

| via helpful involvement | −0.13 | [−0.28, −0.03] | |||||

| via harmful involvement | −0.05 | [−0.19, 0.01] | |||||

Note: Bolded terms indicate significant findings. CI = bias corrected confidence interval

Figure 2.

Models for 6-month HbA1c and 12-month HbA1c were run separately and displayed simultaneously for parsimony. Bolded paths indicate significance. Effects on 6-month and 12-month HbA1c are labeled change in HbA1c as models were adjusted for baseline HbA1c. Rapid Encouragement/Education And Communications for Health (REACH), Family-focused Add-on to Motivate Self-care (FAMS), Hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c), Family/Friend Involvement in Adult Diabetes (FIAD)

In contrast, REACH+FAMS did not have total or direct effects on 6- or 12-month HbA1c but did show mediated effects on both 6- and 12-month HbA1c (Table 1). Compared to control, REACH+FAMS improved helpful family involvement (Figure 2B), and improvements in helpful family involvement during the first 6 months were related to improvements in HbA1c at 6 and 12 months (Figure 2B). As a result, there were significant indirect effects through improved helpful family involvement for 6-month HbA1c and 12-month HbA1c in the group receiving REACH+FAMS (Table 1). Improvement in harmful family involvement was not related to improvements in HbA1c at 6 or 12 months (Figure 1B) and no mediation effects were found via harmful family involvement (Table 1).

For individuals with high baseline HbA1c (Table 2), the confidence intervals for the total and direct effects at 6 months for REACH and REACH+FAMS indicate change occurring, while there is little evidence of change via the indirect effects. However, for individuals with low baseline HbA1c (Table 2), there is little evidence of change for REACH via direct or indirect effects, whereas for REACH+FAMS, confidence intervals suggest change occurs indirectly mostly through helpful family involvement at 6 months. Similar to analyses for the complete sample, there was little evidence of change at 12 months for REACH, regardless of baseline HbA1c. For REACH+FAMS at 12 months in the high and low baseline HbA1c subgroups, there was little evidence of sustained indirect effects in the high baseline group, but evidence of sustained indirect changes in the low baseline HbA1c group.

Table 2.

Subsetted by Baseline HbA1c; Total, Direct, and Indirect Effects

| HbA1c ≥ 8.5% | HbA1c < 8.5% | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||

| REACH vs. Control | ||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Total Effect | Direct Effect | Indirect Effect | Total Effect | Direct Effect | Indirect Effect | |||||||

|

|

||||||||||||

| HbA1c | b | 95% CI | b | 95% CI | b | 95% CI | b | 95% CI | b | 95% CI | b | 95% CI |

| 6-month | −0.85 | [−1.53, −0.16] | −0.89 | [−1.51, −0.18] | 0.00 | [−0.12, 0.11] | −0.17 | [−0.56, 0.22] | −0.12 | [−0.50, 0.27] | −0.06 | [−0.20, 0.07] |

| via helpful involvement | 0.00 | [−0.12, 0.12] | −0.06 | [−0.20, 0.07] | ||||||||

| via harmful involvement | −0.01 | [−0.09, 0.07] | 0.00 | [−0.04, 0.04] | ||||||||

| 12-month | −0.20 | [−0.92, 0.52] | −0.17 | [−0.87, 0.53] | −0.04 | [−0.19, 0.10] | 0.08 | [−0.37, 0.54] | 0.12 | [−0.33, 0.56] | −0.05 | [−0.17, 0.07] |

| via helpful involvement | −0.03 | [−0.17, 0.11] | −0.05 | [−0.17, 0.06] | ||||||||

| via harmful involvement | −0.01 | [−0.11, 0.09] | 0.00 | [−0.05, 0.06] | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| REACH+FAMS vs. Control | ||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Total Effect | Direct Effect | Indirect Effect | Total Effect | Direct Effect | Indirect Effect | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| HbA1c | b | 95% CI | b | 95% CI | b | 95% CI | b | 95% CI | b | 95% CI | b | 95% CI |

|

| ||||||||||||

| 6-month | −0.74 | [−1.43, −0.05] | −0.70 | [−1.39, −0.01] | −0.02 | [−0.20, 0.15] | 0.11 | [−0.33, 0.56] | 0.28 | [−0.17, 0.73] | −0.20 | [−0.43, 0.03] |

| via helpful involvement | −0.04 | [−0.17, 0.09] | −0.18 | [−0.38, −0.01] | ||||||||

| via harmful involvement | 0.02 | [−0.08, 0.11] | −0.02 | [−0.09, 0.06] | ||||||||

| 12-month | −0.16 | [−0.94, 0.62] | −0.08 | [−0.86, 0.70] | −0.09 | [−0.36, 0.18] | −0.01 | [−0.48, 0.46] | 0.15 | [−0.34, 0.64] | −0.19 | [−0.40, 0.03] |

| via helpful involvement | −0.09 | [−0.29, 0.12] | −0.11 | [−0.27, 0.04] | ||||||||

| via harmful involvement | 0.00 | [−0.17, 0.16] | −0.07 | [−0.22, 0.07] | ||||||||

Note: CI = bias corrected confidence interval; indirect effects are bootstrapped. Sample sizes for HbA1c ≥ 8.5% for REACH vs Control are N = 137 and N = 134 and for REACH+FAMS vs Control N = 131 and N = 127 at 6 and 12 months, respectively. Sample sizes for HbA1c < 8.5% for REACH vs Control are N = 177 and N = 176 and for REACH+FAMS vs Control N = 184 and N = 180 at 6 and 12 months, respectively.

Discussion

We found evidence that improvements in family involvement (helpful involvement, specifically) occasioned by the FAMS intervention, mediated improvements in post-intervention HbA1c and sustained HbA1c improvements. In contrast, REACH (the intervention targeting individual behavior only and not family/friend involvement) had significant total and direct effects on HbA1c at 6 months but there was no evidence of mediation by family involvement and no evidence of sustained effects on HbA1c. Finally, changes in harmful family involvement did not mediate improvements in HbA1c immediately post-intervention or over follow-up for REACH or REACH+FAMS.

Results from this secondary analysis of an RCT begin to support the family systems theory hypothesis that when an individual initiates behavior changes, such as improving self-care for diabetes, reinforcement (i.e., feedback loops) from family and friends may serve to sustain those changes. Participants in REACH+FAMS showed increased support from friends and/or family as they initiated better self-care, which had both an immediate and sustained effect on HbA1c. Similarly, Berrera and colleagues reported that a lifestyle program focused on using social supports to create change in health behaviors found improvements in HbA1c were mediated by increased frequency of using social supports (Barrera, Toobert, Angell, Glasgow, & Mackinnon, 2006). Family systems theory would suggest the increases in helpful family involvement or use of social resources, concurrent with individual efforts to improve self-care, facilitate second-order, sustained change (Whitchurch & Constantine, 2009). Furthermore, increases in helpful family involvement could serve to increase concordance in dyadic expectations around managing diabetes (Seidel, Franks, Stephens, & Rook, 2012) or increase communal coping (Zajdel, Helgeson, Seltman, Korytkowski, & Hausmann, 2018), both of which have been associated with better adherence to self-care. This could suggest that by involving family and/or friends in the management of T2D in helpful ways, participants in REACH+FAMS may have been able to create positive feedback loops within their family and social context and make lasting behavioral changes that had long-term impacts on glycemic control. In contrast, participants assigned to REACH only were successful in making individual self-care changes and had short-term improvements in glycemic control, but with no evidence of sustained effects. Evidence of sustained effects are particularly noteworthy, given that the majority of self-management interventions for T2D do not sustain effects past 6 months (Captieux et al., 2018).

Notably, intervention effects did differ based on high or low baseline HbA1c. Although we did not conduct a formal test of effect modification by baseline HbA1c here, a priori analyses indicating the presence of effect modification prompted our subgroup analyses here. Our subgroup analyses suggest individuals with high baseline HbA1c benefited from the REACH intervention (i.e., did not achieve additional benefit from FAMS), whereas individuals with low baseline HbA1c achieved and maintained changes via family involvement. It may be that an individualized self-care support intervention like REACH is sufficient to initiate lifestyle changes that reduce very high HbA1c, such as improving medication adherence and watching carbohydrate intake, whereas the activation of family involvement can supplement and sustain efforts these among individuals already performing these individual self-care behaviors (as indicated by a lower baseline HbA1c). Similarly, in a study comparing diabetes education, education plus individual telephonic coaching, and education plus couple telephonic coaching, for individuals with moderate baseline HbA1c (8.3–9.2%) only those receiving couple coaching benefited from the intervention, whereas for individuals with high baseline HbA1c (≥9.3%), all conditions benefited (Trief et al., 2016). This is a speculative interpretation of these data, and formal testing of different mediators for individual and family-focused interventions, such as medication adherence in REACH and family involvement for REACH+FAMS, would extend the work here.

Contrary to observational research linking harmful family involvement to worse and worsening glycemic control (Mayberry & Osborn, 2014; Nicklett et al., 2013; Nicklett & Liang, 2010; Rosland et al., 2008; Wen et al., 2004), improvements in glycemic control were not mediated by decreased harmful family involvement. Previous work has demonstrated an interaction effect between helpful and harmful family involvement, such that detrimental effects of harmful family involvement are attenuated by simultaneously high levels of helpful family involvement (Mayberry & Osborn, 2014). This interaction could help to unpack why no mediation effects were found through changes in harmful family involvement in this study. Perhaps by increasing helpful family involvement, any negative effects of harmful family involvement on glycemic control were mitigated. The lack of mediation through decreased harmful family involvement occasioned by FAMS could also further support family systems theory, which postulates that reinforcing feedback loops are more important for newly initiated behaviors (Whitchurch & Constantine, 2009).

Limitations and Strengths

We conducted this secondary analysis in the context of a larger RCT which created a unique opportunity to test the family systems theory hypotheses about first-order and second-order, sustained change – and we found differential effects in line with the theory. However, this RCT context contributed limitations and strengths. First, we had less power to compare REACH+FAMS to REACH and thus separately compared each intervention group to the control group. A follow-up study powered to directly test differences between family-focused and individualized interventions would strengthen these findings. Second, glycemic control was used as a proxy for sustained behavioral change in this study, but is an imperfect measure as it is affected by other factors. In addition, we utilized sophisticated statistical techniques allowing us to model multiple mediators simultaneously, as the literature suggests is critical to consider helpful and harmful involvement together to understand the full scope of family involvement. The study was conducted within a sample that was about 50% racial/ethnic minority and/or lower SES and had high retention rates across one year, which increases generalizability and reduces the risk of bias in the findings. Finally, a support person was not required to enroll and the intervention was flexible to include multiple sources of support, allowing for patients with diverse social contexts to participate in the study.

Conclusions

This study experimentally tested family systems theory and demonstrated that improved family and/or friend involvement leads to improved biological outcomes post-intervention and 6-months post intervention. Findings support the premise underlying family interventions for adults with T2D – that improvements in family involvement concurrent with individual behavior change could lead to sustained effects. Although we did not find evidence that improved family involvement enhanced effects, the family-focused intervention led to sustained effects driven by improved family/friend support for self-care. Considering ways individuals with T2D may exert influence on the health of their support persons is a promising avenue for further research which could provide further support for family interventions (Burns, Fillo, Deschenes, & Schmitz, 2020). Interventions targeting individual self-care behaviors, such as those needed to successfully manage T2D, should include elements targeting family involvement (reducing harmful involvement and especially bolstering helpful family involvement) to create changes in social systems that may support lasting improvements in T2D management.

Acknowledgments

Author note: This research is funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) through R01-DK100694. LAN was supported by a career development award from NIH/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (K12-HL137943). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. MKR is supported by the Office of Academic Affiliations, Department of Veteran Affairs and the VA National Quality Scholars Program with use of facilities at VA Tennessee Valley Healthcare System, Nashville, Tennessee. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States government.

The authors thank our partnering clinics – Faith Family Medical Center, The Clinic at Mercury Courts, Connectus Health, Shade Tree Clinic, Neighborhood Health, Vanderbilt Adult Primary Care – and the participants for their contributions to this research.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest. McKenzie K. Roddy, Lyndsay A. Nelson, Robert A. Greevy, and Lindsay S. Mayberry have no conflicts of interest to disclose. Findings were accepted to the 2021 Society of Behavioral Medicine Annual Meeting and Scientific Sessions.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

All procedures were approved by the Vanderbilt Institutional Review Board and all participants provided informed consent prior to inclusion in the study.

References

- Baig AA, Benitez A, Quinn MT, & Burnet DL (2015). Family interventions to improve diabetes outcomes for adults. Ann N Y Acad Sci, 1353, 89–112. doi: 10.1111/nyas.12844 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrera M Jr., Toobert DJ, Angell KL, Glasgow RE, & Mackinnon DP (2006). Social support and social-ecological resources as mediators of lifestyle intervention effects for type 2 diabetes. J Health Psychol, 11(3), 483–495. doi: 10.1177/1359105306063321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennich BB, Roder ME, Overgaard D, Egerod I, Munch L, Knop FK, … Konradsen H. (2017). Supportive and non-supportive interactions in families with a type 2 diabetes patient: an integrative review. Diabetol Metab Syndr, 9, 57. doi: 10.1186/s13098-017-0256-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns RJ, Fillo J, Deschenes SS, & Schmitz N (2020). Dyadic associations between physical activity and body mass index in couples in which one partner has diabetes: results from the Lifelines cohort study. J Behav Med, 43(1), 143–149. doi: 10.1007/s10865-019-00055-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Captieux M, Pearce G, Parke HL, Epiphaniou E, Wild S, Taylor SJ, & Pinnock H (2018). Supported self-management for people with type 2 diabetes: a meta-review of quantitative systematic reviews. BMJ open, 8(12), e024262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fokkema MR, Bakker AJ, de Boer F, Kooistra J, de Vries S, & Wolthuis A (2009). HbA1c measurements from dried blood spots: validation and patient satisfaction. Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine (CCLM), 47(10), 1259–1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasgow RE, & Toobert DJ (1988). Social environment and regimen adherence among type II diabetic patients. Diabetes Care, 11(5), 377–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goins RT, Noonan C, Gonzales K, Winchester B, & Bradley VL (2017). Association of depressive symptomology and psychological trauma with diabetes control among older American Indian women: Does social support matter? J Diabetes Complications, 31(4), 669–674. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2017.01.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF (2009). Beyond Baron and Kenny: Statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium. Communication monographs, 76(4), 408–420. [Google Scholar]

- Henry SL, Rook KS, Stephens MA, & Franks MM (2013). Spousal undermining of older diabetic patients’ disease management. Journal of Health Psychology, 18(12), 1550–1561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayberry LS, Berg CA, Greevy RA Jr, & Wallston KA (2019). Assessing helpful and harmful family and friend involvement in adults’ type 2 diabetes self-management. Patient education and counseling, 102(7), 1380–1388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayberry LS, Berg CA, Greevy RA, Nelson LA, Bergner EM, Wallston KA, … Elasy TA. (2020). Mixed-Methods Randomized Evaluation of FAMS: A Mobile Phone-Delivered Intervention to Improve Family/Friend Involvement in Adults’ Type 2 Diabetes Self-Care. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 55, 165–178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayberry LS, Berg CA, Harper KJ, & Osborn CY (2016). The design, usability, and feasibility of a family-focused diabetes self-care support mHealth intervention for diverse, low-income adults with type 2 diabetes. Journal of Diabetes Research, 2016, 7586385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayberry LS, Egede LE, Wagner JA, & Osborn CY (2015). Stress, depression and medication nonadherence in diabetes: test of the exacerbating and buffering effects of family support. Journal of behavioral medicine, 38(2), 363–371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayberry LS, Harper KJ, & Osborn CY (2016). Family behaviors and type 2 diabetes: What to target and how to address in interventions for adults with low socioeconomic status. Chronic Illn, 12(3), 199–215. doi: 10.1177/1742395316644303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayberry LS, & Osborn CY (2012). Family support, medication adherence, and glycemic control among adults with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care, 35(6), 1239–1245. doi: 10.2337/dc11-2103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayberry LS, & Osborn CY (2014). Family involvement is helpful and harmful to patients’ self-care and glycemic control. Patient Educ Couns, 97(3), 418–425. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2014.09.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayberry LS, Rothman RL, & Osborn CY (2014). Family members’ obstructive behaviors appear to be more harmful among adults with type 2 diabetes and limited health literacy. J Health Commun, 19 Suppl 2, 132–143. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2014.938840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson LA, Greevy RA Jr, Spieker A, Wallston KA, Kripilani S, Gentry C, … Mayberry LS. (2021). Effects of a tailored text messaging intervention among diverse adults with type 2 diabetes: Evidence from the 15-month REACH randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Care, 44(1), 26–34. doi: 10.2337/dc20-0961 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson LA, Wallston KA, Kripalani S, Greevy RA Jr, Elasy TA, Bergner EM, … Mayberry LS. (2018). Mobile phone support for diabetes self-care among diverse adults: Protocol for a three-arm randomized controlled trial. JMIR research protocols, 7(4), e92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicklett EJ, Heisler MEM, Spencer MS, & Rosland AM (2013). Direct Social Support and Long-term Health Among Middle-Aged and Older Adults With Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 68(6), 933–943. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbt100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicklett EJ, & Liang J (2010). Diabetes-related support, regimen adherence, and health decline among older adults. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci, 65B(3), 390–399. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbp050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ (2015). Advances in mediation analysis: A survey and synthesis of new developments. Annual review of psychology, 66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, & Hayes AF (2004). SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behavior research methods, instruments, & computers, 36(4), 717–731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosland A-M, Heisler M, Choi H-J, Silveira MJ, & Piette JD (2010). Family influences on self-management among functionally independent adults with diabetes or heart failure: do family members hinder as much as they help? Chronic illness, 6(1), 22–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosland A-M, Heisler M, & Piette JD (2012). The impact of family behaviors and communication patterns on chronic illness outcomes: a systematic review. Journal of behavioral medicine, 35(2), 221–239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosland A-M, Kieffer E, Israel B, Cofield M, Palmisano G, Sinco B, … Heisler M. (2008). When is social support important? The association of family support and professional support with specific diabetes self-management behaviors. Journal of general internal medicine, 23(12), 1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidel AJ, Franks MM, Stephens MA, & Rook KS (2012). Spouse Control and Type 2 Diabetes Management: Moderating Effects of Dyadic Expectations for Spouse Involvement. Fam Relat, 61(4), 698–709. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3729.2012.00719.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens MA, Franks MM, Rook KS, Iida M, Hemphill RC, & Salem JK (2013). Spouses’ attempts to regulate day-to-day dietary adherence among patients with type 2 diabetes. Health Psychol, 32(10), 1029–1037. doi: 10.1037/a0030018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torenholt R, Schwennesen N, & Willaing I (2014). Lost in translation--the role of family in interventions among adults with diabetes: a systematic review. Diabet Med, 31(1), 15–23. doi: 10.1111/dme.12290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trief PM, Fisher L, Sandberg J, Cibula DA, Dimmock J, Hessler DM, … Weinstock RS. (2016). Health and Psychosocial Outcomes of a Telephonic Couples Behavior Change Intervention in Patients With Poorly Controlled Type 2 Diabetes: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Diabetes Care, 39(12), 2165–2173. doi: 10.2337/dc16-0035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vongmany J, Luckett T, Lam L, & Phillips JL (2018). Family behaviours that have an impact on the self-management activities of adults living with Type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-synthesis. Diabet Med, 35(2), 184–194. doi: 10.1111/dme.13547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker RJ, Smalls BL, & Egede LE (2015). Social determinants of health in adults with type 2 diabetes--Contribution of mutable and immutable factors. Diabetes Res Clin Pract, 110(2), 193–201. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2015.09.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen LK, Shepherd MD, & Parchman ML (2004). Family support, diet, and exercise among older Mexican Americans with type 2 diabetes. The Diabetes Educator, 30(6), 980–993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitchurch G, & Constantine L (2009). Systems Theory. In Boss P, Doherty W, LaRossa R, Schumm W, & Steinmetz S (Eds.), Sourcebook of Family Theories and Methods (pp. 325–355). Boston, MA: Springger. [Google Scholar]

- Zajdel M, Helgeson VS, Seltman HJ, Korytkowski MT, & Hausmann LRM (2018). Daily Communal Coping in Couples With Type 2 Diabetes: Links to Mood and Self-Care. Ann Behav Med, 52(3), 228–238. doi: 10.1093/abm/kax047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]