Abstract

Our objective was to establish the rate of neurological involvement in Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli–hemolytic uremic syndrome (STEC-HUS) and describe the clinical presentation, management and outcome. A retrospective chart review of children aged ≤ 16 years with STEC-HUS in Children’s Health Ireland from 2005 to 2018 was conducted. Laboratory confirmation of STEC infection was required for inclusion. Neurological involvement was defined as encephalopathy, focal neurological deficit, and/or seizure activity. Data on clinical presentation, management, and outcome were collected. We identified 240 children with HUS; 202 had confirmed STEC infection. Neurological involvement occurred in 22 (11%). The most common presentation was seizures (73%). In the neurological group, 19 (86%) were treated with plasma exchange and/or eculizumab. Of the 21 surviving children with neurological involvement, 19 (91%) achieved a complete neurological recovery. A higher proportion of children in the neurological group had renal sequelae (27% vs. 12%, P = .031). One patient died from multi-organ failure.

Conclusion: We have identified the rate of neurological involvement in a large cohort of children with STEC-HUS as 11%. Neurological involvement in STEC-HUS is associated with good long-term outcome (complete neurological recovery in 91%) and a low case-fatality rate (4.5%) in our cohort.

|

What is Known: • HUS is associated with neurological involvement in up to 30% of cases. • Neurological involvement has been reported as predictor of poor outcome, with associated increased morbidity and mortality. | |

|

What is New: • The incidence of neurological involvement in STEC-HUS is 11%. • Neurological involvement is associated with predominantly good long-term outcome (90%) and a reduced case-fatality rate (4.5%) compared to older reports. |

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00431-021-04200-1.

Keywords: HUS, STEC-HUS, Neurology, Neurological involvement

Introduction

Hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS) is characterized by a triad of thrombocytopenia, microangiopathic hemolytic anemia, and kidney failure. Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC)-HUS is typically preceded by a diarrheal illness (usually bloody). In Ireland, the most common Escherichia coli (E. coli) serotype is O157:H7 [1]. Shiga toxin induces an inflammatory cascade, triggering endothelial injury, and thrombotic microangiopathy, resulting in micro-thrombi formation in multiple organs [2–4]. Activation of the alternative complement pathway may also have a role [5]. Shiga toxin-producing E. coli–HUS is the most common cause of acute kidney injury in children [1, 6–9]. Since 2004, STEC is a notifiable disease in Ireland and we consistently have the highest reported rate of STEC infection in Europe (19.4 per 100,000 in 2017) [10].

Neurological involvement is reported in approximately 30% of all types of HUS [2, 11–29]. Seizures, irritability, lethargy, encephalopathy, and coma are the most common central nervous system (CNS) manifestations. Neurological involvement in STEC-HUS is associated with a higher mortality rate (up to 30%), long-term physical disability, neuropsychological and cognitive sequelae (Supplementary Table 1) [11–16, 18, 21–25, 27–35].

Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli HUS is managed with careful fluid and diuretic administration, red cell transfusion, and in up to 50% of cases temporary kidney replacement therapy (continuous veno-venous hemofiltration (CVVH), peritoneal dialysis (PD), or hemodialysis (HD)) [36]. There is no consensus on the treatment of CNS involvement in STEC-HUS. Mixed outcomes have been reported after treatment with plasma exchange (PE) and/or anti-C5 monoclonal antibodies, e.g., eculizumab [13, 29, 34, 37–43].

We have reviewed all cases of STEC- HUS in children (≤ 16 years) referred to tertiary pediatric nephrology services in the Republic of Ireland over 13 years (n = 202). We report the rate of neurological involvement in this group, describe the clinical presentation, neurological and renal outcomes, and present an overview of management.

Methods

Study design

We undertook a retrospective chart review of children aged ≤ 16 years with STEC-HUS in Children’s Health Ireland, Dublin from, January 1, 2005, to December 31, 2018. Children’s Health Ireland is the sole provider of tertiary pediatric nephrology services in the Republic of Ireland. Patients were identified through the hospital discharge coding system and the nephrology patient database.

Inclusion criteria

Children aged ≤ 16 years who met the clinical criteria for a diagnosis of HUS and laboratory confirmation of STEC infection were included.

STEC-HUS case definition

Hemolytic uremic syndrome was defined as acute kidney injury, microangiopathic hemolytic anemia (hemoglobin < 10 g/dL with fragmented red cells), and thrombocytopenia (platelets < 150 × 109/L). Laboratory confirmation of STEC was performed at the Health Service Executive Public Health Laboratory at Cherry Orchard Hospital, Dublin, which provides the National Reference service for STEC. Criteria for microbiological confirmation (as per national Health Surveillance and Protection Centre criteria) was as follows: (1) isolation of an E. coli strain by culture that is known to produce Shiga toxin (stx) or harbours stx1 or stx2 gene(s), or (2) direct detection of stx1 or stx2 nucleic acid (without strain isolation) by polymerase chain reaction (PCR), or (3) detection of E. coli serogroup specific antibodies [10].

Neurological manifestations

Neurological involvement was defined as encephalopathy (altered or fluctuating level of consciousness), focal neurological deficit (abnormal neurological examination), and/or seizure activity. Patients were divided into those with neurological involvement (neurological group) and those without (non-neurological group). The total group refers to all children with STEC-HUS. Image interpretation was performed by two specialized pediatric radiologists.

Exclusion criteria

Children with HUS who did not have confirmed STEC infection or had proven STEC infection but had a confirmed genetic diagnosis of atypical-HUS (aHUS) were excluded (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Data collection

Data was collected from the medical and electronic charts regarding symptoms at presentation, laboratory values (urea, creatinine, hemoglobin, sodium, white cell count and differential at presentation and maximum values), microbiological results, investigations (radiology, electrophysiology), treatment, duration of stay, and long-term outcomes (defined below).

Outcome

Renal sequelae were defined as the presence of one of the following: (1) hypertension requiring antihypertensive medication; (2) proteinuria (> 0.15 g/L or urinary protein-to-creatinine ratio greater than 20 mg/mmol); (3) impaired kidney function with an estimated glomerular filtration rate < 90 mL/min/1.73 m2 (Pediatric Schwartz formula) [44]. Neurological sequelae were defined as recurrent seizures, focal neurological deficit, or altered functional status at follow-up. The Pediatric Cerebral Performance Category (PCPC) was used as a qualitative assessment of overall neurological morbidity [45].

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was granted by the local research and ethic committee.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using the SPSS version 26.0 (IBM SPSS Statistics, IBM Corporation). Frequencies and percentages were calculated to compare groups. To test for normal distribution, the Shapiro–Wilk test was used. For non-parametric data, quantitative and continuous variables were expressed as median and interquartile range (IQR). Non-parametric data were analyzed by Mann–Whitney U test and Pearson chi-square test. Statistical significance was determined at P value less than .05.

Results

Population

We identified 240 children with HUS. No evidence of STEC infection was detected in 36/240 (15%) patients. Two children had confirmed STEC infection but later developed recurrence of HUS in the absence of STEC infection—pathogenic complement gene mutations were subsequently identified. Two hundred two children with confirmed STEC infection (total group) were included in the analysis (Supplementary Fig. 1). Neurological involvement was identified in 22/202 children (11%) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographics, clinical presentation, and management of pediatric HUS patients

| Total HUS group, n = 202 | HUS neurological group, n = 22 | HUS non-neurological group, n = 180 | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| Gender, female:male, n | 114: 88 | 13:9 | 101:79 | .79 |

| Age (years), median (IQR) | 3.2 (1.6–6.3) | 2.6 (1.1–7.4) | 3.2 (1.6–6.2) | .44 |

| Age category, n (%) | ||||

| < 1 year | 15 (7.4) | 4 (18) | 11(6.1) | |

| ≥ 1–2 years | 44 (22) | 4 (18) | 40 (22) | .228 |

| ≥ 2–5 years | 79 (39) | 7 (32) | 72 (40) | |

| ≥ 5 years | 64 (32) | 7 (32) | 57 (32) | |

| Season, n (%) | ||||

| Spring | 35 (17) | 4 (18) | 31 (17) | |

| Summer | 86 (43) | 12 (55) | 74 (41) | .381 |

| Autumn | 64 (32) | 6 (27) | 58 (32) | |

| Winter | 17 (8.4) | 0 (0.0) | 17 (9.4) | |

| LOS, days | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 10 (6.0–16.0) | 21 (13.0–34.0) | 9.0 (6.0–15.0) | < 0.001 |

| ICU admission, n (%) | 48 (24) | 19 (86) | 29 (16) | < 0.001 |

| Presenting symptoms | ||||

| Incubation period, days | ||||

| Median (IQR) | (4.0–7.0) | 5 (3.5–7.0) | 5 (4.0–7.0) | .092 |

| Diarrhea, n (%) | 196 (97) | 22 (100) | 174 (97) | 0.39 |

| Urine output, n (%) | ||||

| Normal | 45 (22) | 1 (4.5) | 44 (24) | |

| Anuria/oliguria | 157 (78) | 21 (95) | 136 (76) | .034 |

| Laboratory findings | ||||

| (admission) median (IQR) | ||||

| White cell count (× 109/L) | 13.2 (10.4–18.4) | 16.1 (12–20) | 13.0 (10.4–18.1) | .18 |

| Neutrophils (× 109/L) | 7.0 (5.1–11.1) | 7.4 (5.3–12.2) | 6.8 (5.1–11) | .18 |

| Hemoglobin (g/L) | 87.0 (75–100.0) | 87.5 (76.8–98.5) | 87.0 (74.3–100.8) | .80 |

| Platelets (× 109/L) | 51.0 (31–76) | 51.5 (29.8–63.5) | 50.0 (31–78) | .82 |

| Urea (mmol/L) | 23.4 (15.2–32.1) | 24.6 (16.1–37.1) | 23.3 (15.1–32) | .63 |

| Creatinine (μmol/L) | 211 (121.5–314.5) | 297.5 (148.5–371.3) | 208 (120–305) | .06 |

| Max. creatinine (μmol/L) | 349.5 (150.5–578.8) | 383 (271.5–737.5) | 349 (142–576) | .82 |

| Sodium (mmol/L) | 134 (132–136) | 135 (132–138) | 134 (132–136) | .34 |

| Treatment | ||||

| Dialysis, n (%) | 107 (53) | 19 (86) | 88 (49) | < .001 |

| CVVH | 16 (7.9) | 6 (27) | 10 (5.6) | |

| PD | 83 (41) | 10 (46) | 73 (41) | .016 |

| CVVH and PD | 8 (4.0) | 3 (14) | 5 (2.8) | |

| Duration, days, median (IQR) | 9 (6–13) | 11 (7.3–19) | 9 (6–13) | .81 |

| PE, n (%) | 24 (12) | 15 (68) | 9 (5.0) | |

| Duration, days, median (IQR) | 4 (2.5–5) | 4 (3–55) | 4 (1–5) | < .001 |

| Eculizumab, n (%) | 8 (4.0) | 8 (36) | 0 (0) | 0.503 |

No missing data

CVVH continuous veno-venous hemofiltration, HUS hemolytic uremic syndrome, ICU intensive care unit, IQR interquartile range, LOS length of stay, max maximum, n number, PD peritoneal dialysis, PE plasma exchange

Microbiology

A Shiga toxigenic strain of E. coli was isolated in 187/202 (92%) children on stool culture; 172 also had stx detected on PCR and 37 had antibodies on serology. Seven E. coli serotypes were identified; O157 (50%) and O26 (30%) were the most common. Sixteen patients (8%) had an ungroupable E. coli serotype (Table 2). In 4 patients, stx was detected without isolation of an E. coli strain. Both stx1 and stx2 were detected in 43 children, stx2 alone in 109 and stx1 alone in three. Unspecified stx was identified in 18 and no stx detected in 27.

Table 2.

E. coli serogroups identified from pediatric HUS patients

| Escherichia coli | Total HUS group, n = 202 (%) | stx detected, n (%) | Neurological group, n = 22 | stx detected, n (%) | Non-neurological group, n = 180 (%) | stx detected, n (%) | P value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli O157, n (%) | 101 (50) | 86 (85) | 7 (29) | 5(66) | 94 (52) | 81 (86) | 0.05 |

| E. coli O26, n (%) | 62 (30) | 53 (85) | 8 (38) | 6 (75) | 54 (30) | 47 (87) | 0.34 |

| Ungroupable, n (%) | 16 (7.9) | 12 (75) | 4 (19) | 3 (75) | 12 (6.6) | 9 (75) | 0.05 |

| E. coli O145, n (%) | 13 (6.4) | 12 (92) | 2 (9.5) | 2 (100) | 11 (6) | 10 (83) | 0.20 |

| E. coli O103, n (%) | 4 (2.0) | 4 (100) | 0 | 0 | 4 (2.2) | 4 (100) | 0.49 |

| Shigatoxin only, n (%) | 4 (1.5) | 4 (1.5) | 0 | 0 | 4 (2.2) | 4 (2.2) | 0.49 |

| E. coli O111, n (%) | 3 (1.5) | 3 (100) | 1 (4.8) | 1 (100) | 2 (1.1) | 2 (100) | 0.19 |

| E. coli O132, n (%) | 1 (0.5) | 1 (100) | 0 | - | 1 (0.6) | 1 (100) | 0.73 |

| E. coli O78, n (%) | 1 (0.5) | 1 (100) | 0 | - | 1 (0.5) | 1 (100) | 0.80 |

| Total | 205** | 176** (85) | 22 | 16 (76) | 183** | 160** (86) | - |

HUS hemolytic uremic syndrome, PCR polymerase chain reaction, stx shigaotoxin

*Difference in serotypes between neurological and non-neurological group; **Three patients had both O26 and O157

Clinical presentation

At presentation, 196/202 (97%) children had diarrhea, of whom 121/196 (61%) had bloody diarrhea, and 45/202 (22%) were febrile. There was a significantly higher proportion of patients in the neurological group with oliguria or anuria (96% vs. 76% (P = .034)). The degree of leukocytosis, thrombocytopenia, anemia, and hyponatremia at presentation were not significantly different between groups. Admission and peak creatinine were similar in both groups (Table 1). Admission rate to the PICU was higher [86% vs. 16% (P < .001)] and median length of hospital stay was longer [21.0 days vs. 9.0 days (P < .001)] in the neurological group.

Neurological presentation

The neurological group comprised of 22 children (Table 3). The median time from admission to the onset of CNS symptoms (seizures, encephalopathy or focal neurological impairment) was one day (IQR 0.0–2.3 days). Seizure was the most common presentation [16/22 (73%)]; four children presented with status epilepticus. Ten patients were clinically encephalopathic, and four had focal neurological deficits. Anti-epileptic medications were used during hospital admission in 16 patients; four remained on medication at discharge. All medications had been discontinued by 6 months post-discharge.

Table 3.

Presentation, investigations, and outcome of the neurological cohort (n = 22)

| No | CNS symptoms | Acute radiological features of HUS | EEG | Treatment | AEDs | Neurological outcome (PCPC score) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CT | MRI | ||||||

| 1 | Encephalopathic | - | RD and T2-hyperintensity in the centrum semi-ovale and PVWM | - | PE | BZD | Normal (1) |

| GTCS | Follow-Up: Resolved | Discharge: Nil | |||||

| 2 | Encephalopathic | - | - | Absence of cerebral activity | PE then Eculizumab | - | Deceased |

| Hypotonic | |||||||

| 3 | Encephalopathic | - | - | - | Eculizumab | - | Normal (1) |

| 4 | GTCS | - | - | - | - | BZD | Baseline (2) |

| Discharge: Nil | |||||||

| 5 | Status Epilepticus | No | - | - | PE | BZD, PHY | Normal (1) |

| Discharge: Nil | |||||||

| 6 | Seizure | No | No | Slow | PE | VPA | Baseline (2) |

| Discharge: VPA | |||||||

| 7 | Encephalopathic | No | No | Slow | Eculizumab | BZD, PHY, LEV | Normal (1) |

| GTCS then prolonged focal seizure later in admission | Discharge: LEV | ||||||

| 8 | GTCS | - | - | Eculizumab | PHY | Normal (1) | |

| Discharge: Nil | |||||||

| 9 | Encephalopathic | - | No | - | PE | BZD | Normal (1) |

| GTCS | Discharge: Nil | ||||||

| 10 | GTCS | No | No | Slow | Eculizumab | - | Normal (1) |

| 11 | Encephalopathic | - | No | - | PE | BZD, PHB, PHY | Normal (1) |

| Status epilepticus | Discharge: Nil | ||||||

| 12 | GTCS | No | - | - | PE | BZD | Normal (1) |

| Discharge: Nil | |||||||

| 13 | Encephalopathic | No | - | Slow | PE | - | Normal (1) |

| 14 | Status epilepticus | Low attenuation in bilateral BG and THAL | T2 hyperintensity and mixed increased/RD in BG and THAL | - | PE then eculizumab | PHB, PHY, THI | Normal (1) |

| Focal seizures | Follow-Up: Improved | Discharge: PHY | |||||

| 15 |

Encephalopathic Hemiparesis GTCS |

Loss of GWM differentiation in R occipital lobe | T2 and FLAIR hyperintensity in the PVWM bilaterally (R > L) and R occipital lobe | Abnormal | PE | PHB, PHY Discharge: PHB | Normal (1) |

| 16 |

Prolonged focal motor seizure Encephalopathic Abnormal tone |

Low attenuation in bilateral BG and THAL | T2 hyperintensity and mixed increased/RD in BG and THAL | Slow | Eculizumab then PE |

BZD Discharge: Nil |

Mild Impairment (2) Difficulty with complex motor tasks |

| 17 | Encephalopathic | - | - | Slow | PE |

LEV Discharge: Nil |

Normal (1) |

| 18 | Status epilepticus | - |

RD in WM and BG Follow-Up: Resolved |

Slow | PE then eculizumab |

BZD, PHB Discharge: Nil |

Normal (1) |

| 19 | Dysarthria and weakness | - | - | - | - | - |

Mild Impairment (2) Dysarthria, mild weakness |

| 20 | Focal motor seizure | - |

RD in centrum semi-ovale and PVWM T2 hyperintensity in centrum semi-ovale |

Slow | PE |

BZD, LEV Discharge: Nil |

Normal (1) |

| 21 |

Left 4th CN palsy L upper limb weakness |

No | Increased DWI and edema in cerebellum | - | PE | - | Normal (1) |

| 22 | GTCS | No | - | - | - |

BZD Discharge: Nil |

Normal (1) |

AED antiepileptic drugs, BG basal ganglia, BZD benzodiazepine, CN cranial nerve, CNS central nervous system, CT computed tomography, DWI diffusion-weighted imaging, EEG electroencephalogram, GTCS generalized tonic–clonic seizure, L left, LEV levetiracetam, MRI magnetic resonance imaging, PCPC Pediatric Cerebral Performance Category, PE plasma exchange, PHB phenobarbitone, PHY phenytoin, PVWM periventricular white matter, R right, RD restricted diffusion

Electroencephalogram was performed in 10 children during the acute illness. All studies were abnormal, with a slow background consistent with encephalopathy in nine and absent cerebral activity in one.

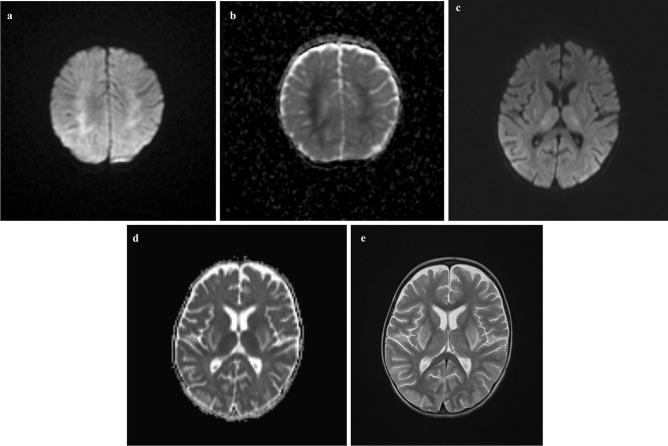

Neuroimaging was available in 17 children (Table 3). Ten patients had no acute findings on neuroimaging despite clinical evidence of encephalopathy (3 magnetic resonance imaging (MRI); 4 computer tomography (CT); 3 both MRI and CT). There was no difference in the timing of imaging between those with or without acute changes. Table 3 summarizes neuroimaging findings. Figure 1 illustrates the typical restricted diffusion pattern on diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI). Three patients had follow-up MRI studies which showed improvement or complete resolution.

Fig. 1.

a, b Patient 1: axial DWI (a) and ADC map (b) show reduced diffusivity in both centrum semi-ovale which extended inferiorly to the periventricular white matter adjacent to bilateral frontal horns. c–e Patient 16: axial DWI (c) and ADC map (d) show restricted diffusion in the thalami bilaterally with increased diffusion within the periphery of the lentiform nuclei. There is corresponding increased signal abnormality in grey matter structures on axial T2 images (e)

Management

In the total group, 107/202 (53%) required dialysis. Significantly more patients in the neurological group needed dialysis than in the non-neurological group (86% vs. 49%, (P < .001)). The most common modality utilized was PD in 83/107 (77%); CVVH in 16 (15%) and 8 (7.5%) children had both.

In the total group, 24/202 (12%) had PE; 15/22 (68%) in the neurological group and 9/180 (5.0%) in the non-neurological group. The median number of PE sessions in the neurological group was 4.0 (IQR 3.0–5.0). Patients who received PE without evidence of CNS involvement (n = 9) did so due to atypical presentation before the confirmation of STEC. Eight children had eculizumab, all in the neurological group (Supplementary Fig. 1).

In the neurological group, 19/22 patients (86%) had either PE or eculizumab (Table 3). Three patients received neither—one had a single seizure in a referring hospital but was not clinically encephalopathic on arrival at our center (patient 4); one had a prolonged PICU admission and neurological deficits were only noted post-extubation (patient 19); one had a seizure thought to be related to severe hypertension at the time (patient 22). One patient received eculizumab then PE (4 days later) due to the re-emergence of neurological signs (abnormal neurological examination, increased tone and altered level of consciousness) despite an initial improvement (patient 16). Three received PE then eculizumab—due to concerns regarding response to the initial treatment or evolving diagnostic uncertainty. Plasma exchange was commenced within 24 h of the onset of neurological symptoms in 13 of 15 (87%) cases. Four patients were treated with eculizumab alone. All patients who received eculizumab initially did so within 24 h.

One patient in the neurological group died from multi-organ failure. Two patients developed central line related deep venous thrombosis requiring anticoagulation. One of these patients also received treatment for an associated fungal infection. All patients who got eculizumab were given antibiotic prophylaxis and appropriate meningococcal vaccination.

Outcomes

Neurological

Of the 21 surviving patients with neurological involvement, 19/21 (91%) made a complete recovery. Two patients (9.5%) had mild impairment on PCPC at both discharge and most recent follow-up: both reported difficulties with complex motor tasks. One patient developed a brief generalized onset-motor seizure 1-year post-discharge but was not commenced on anti-epileptic medication.

Renal

Complete follow-up data were available on 178/202 children (88%), 18 (9%) were referred to regional pediatric centers for follow-up, and 5 (2.5%) were lost to follow-up. Renal recovery was achieved in 154/178 (87%) after a median follow-up of 2.4 years (IQR 0.7–5.5 years). A greater proportion of patients in the neurological group had renal sequelae (27% vs. 12%; P 0.031) (Table 4). Two patients, one from each group, developed stage 5 chronic kidney disease and were transplanted.

Table 4.

Renal outcome of the total group with STEC-HUS

| Total group, n = 202 (%) | Neurological group, n = 22 (%) | Non-neurological group, n = 180 (%) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Long-term data available | 178 (88) | 21 (96) | 157 (87) | |

| Regional center follow-up | 18 (8.9) | 0 | 18 (10) | .11 |

| Lost to follow-up | 5 (2.5) | 0 | 5 (2.8) | |

| Deceased | 1 (0.5) | 1 (4.5) | 0 | |

| Total group, n = 178 (%) | Neurological group, n = 21 (%) | Non-neurological group, n = 157 (%) | ||

| Duration of follow-up, years, median (IQR) | 2.4 (0.7–5.5) | 3.6 (2.3–4.6) | 2.2 (0.6–5.6) | .037 |

| Complete renal recovery | 154 (87) | 15 (71) | 139 (89) | .031 |

| Long-term renal sequelae | 24 (14) | 6 (27) | 18 (12) | .031 |

| Proteinuria | 14 (7.9) | 5 (24) | 9 (5.7) | .004 |

| Hypertension | 7 (3.9) | 1 (4.8) | 5 (3.2) | .707 |

| Mild impairment (eGFR 60–89 mL/min/1.73 m2) | 6 (3.4) | 3 (14) | 3 (1.9) | .003 |

| Mild/moderate impairment (eGFR 45–59 mL/min/1.73 m2) | 4 (2.2) | 0 | 4 (2.5) | .459 |

| CKD 5-transplant | 2 (1.1) | 1 (4.8) | 1 (0.6) | `.092 |

Definitions: complete renal recovery, absence of proteinuria or hypertension and a normal eGFR; hypertension, ≥ 95th percentile for age, height, and sex and requiring an antihypertensive medication; proteinuria, > 0.15 g/L or urinary protein-to-creatinine ratio greater than 20 mg/mmol

eGFR estimated glomerular filtration rate, CKD chronic kidney disease, n number

Discussion

We have identified that the rate of neurological involvement in STEC-HUS is 11%. Neurological involvement is associated with predominantly good long-term outcome (90%) and a reduced case-fatality rate (4.5%) compared to older reports.

The reported rate of neurological involvement in children with HUS varies between 10 and 52% (Supplementary Table 1) [11–16, 18, 20–25, 27–35]. We report a rate of 11% based on a strict definition of neurological involvement (seizures, encephalopathy or focal neurological deficit). We considered features such as irritability or lethargy to be non-specific. Four patients met the criteria for neurological involvement, but STEC infection was not confirmed, and they were excluded; no alternative etiology was identified. The possibility of failure to identify STEC infection in this small group exists—their inclusion would increase the rate of neurological involvement to 12%.

Seizure (16/22 (73%)) was the most common presentation of neurological involvement. Neurological involvement was noted early in the disease course, manifesting within 48 h of admission to hospital in 73%. Close monitoring of CNS symptoms and careful clinical assessment is important to identify neurological involvement in children with HUS early in the course of their disease.

Demographic variables did not predict neurological involvement in our cohort, and we did not identify a trend for a higher degree of leukocytosis or peak creatinine, as reported previously (Table 1) [14, 18, 46]. The E. coli serogroups identified were comparable between the neurological and non-neurological groups. Children in the neurological group had a significantly greater need for dialysis (86% vs. 49%, (P < .001)), PICU admission (86% vs. 16%, (P < 0.001)), and a longer length of hospital stay (21 (13–34) days vs. 9 (6–15) days, (P < 0.001)), reflecting a more severe course of illness in this group. The implementation of a HUS prognostic index score has been proposed as a predictor of short and long-term outcomes [47]. However, in our cohort, it did not predict CNS involvement, length of stay, mortality, or long-term sequelae (Supplementary Table 3). Therefore, other markers of disease severity or prediction score needed to be developed to predict disease severity.

Neuro-radiology in children with HUS is focused on the exclusion of hemorrhage and the identification of cerebral edema and vasculitis [19]. Children in the neurological group underwent CT and/or MRI depending on their individual clinical circumstances. Based on availability, and if patients are sufficiently stable to allow for a longer examination duration, MRI is the imaging modality of choice. We identified the typical DWI abnormalities of both deep white and grey matter in our patients (n = 7) [13]. All children who had DWI changes had a normal neurological outcome (Table 3). Therefore, observed DWI changes are reversible lesions in children with good neurological recovery and routine follow-up neuroimaging is not required, unless abnormal neurological examination.

Evidence supporting the use of supplemental treatments, such as PE or eculizumab, in STEC-HUS is lacking [48–51]. Extensive cases series and small cohort studies have been published but no randomized control trials have been reported (Supplementary Table 2) [13, 15, 29, 33, 34, 37–43, 52–54]. Many specialists, while cautiously skeptical of the role of such treatments, tend to use supplemental therapies in severe cases of HUS, particularly in the context of CNS involvement [48–51]. In our cohort, we reserved additional treatments for children with severe disease, treating 20/202 children (9.9%) with PE, 4/202 (1.9%) with eculizumab, and 4/202 (1.9%) with both. Our initial approach is treatment with PE; reserving Eculizumab for use when prompt initiation of PE is not practicable or if overwhelming multi-system involvement. It is important to avoid the simultaneous use of PE and eculizumab as monoclonal antibodies will be removed by PE. It is difficult, based on our positive experience, to forgo supplemental therapies until the outcomes of randomized controlled trials are available.

Neurological involvement in HUS has been reported to be associated with high mortality and significant long-term neurological morbidity (Supplementary Table 1) [11–16, 18, 20–25, 27–35]. Reported outcomes vary depending on the period studied and the case definition employed. Studies based on cohorts of children with HUS and CNS involvement before 2010 had a median mortality rate of 17% (IQR 7.0–45%) [11, 12, 19, 21–25, 27, 28, 30] and long-term neurological sequelae of 14% (IQR 11–33%) [12, 19, 22, 24, 30, 31]. More recent studies (cohorts after 2010) have better outcomes with lower mortality (14%, (IQR 13–22%)) [13, 14, 16, 18, 20, 34] and less long-term neurological sequelae (8.3%, IQR 5.3–35%)) [13, 15, 16, 18, 33–35]. Substantial improvements in diagnosis and supportive care have evolved in the intervening period. In our neurological group (n = 22), one patient died, and two children had long-term neurological consequences—giving comparative rates of 4.5% case-fatality, 9.5% mild neurological sequelae, and no severe neurological sequelae. The rate of kidney sequelae on follow-up is significantly better than that described in other cohorts—14% vs 20–25% [2, 54]. It is likely that advances in supportive care are the primary driver for improved outcomes (renal and neurological) in our cohort compared to older published cohorts. We believe that more optimism should be afforded when counseling parents regarding long-term neurological and renal sequelae.

Making comparisons between cohorts of HUS patients treated using different protocols in different centers is not optimal. Differences in the case definition, case capture, inclusion of aHUS patients, length of follow-up, and treatment modalities, along with demographic variables and the genetic background of the population make comparisons complex. Our cohort benefits from a high degree of case capture based on a well-defined geographical area served by a single tertiary center—near complete capture of HUS cases with more mild disease involvement will have an impact on measurement of overall disease severity.

One important limitation of our study is the ability to detect more subtle changes in neurocognitive function and behavior. The PCPC was developed to quantify overall functional morbidity in children after critical illness—application of more sensitive scales may allow for the detection of more subtle changes in neurocognitive outcomes and behavior [46, 55–57].

Conclusion

One in ten children with STEC-HUS will have neurological involvement and 90% will have a complete neurological recovery. The optimal management of neurological involvement in STEC-HUS needs further study. In the absence of good quality randomized control studies, it is important that cohort studies are reported.

Supplementary information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the work of the National STEC Reference Service based at the Health Service Executive Public Health Laboratory, Dublin Mid-Leinster, for their reference laboratory work on these samples and isolates.

Abbreviations

- aHUS

Atypical-HUS

- CNS

Central nervous system

- CT

Computed tomography

- CVVH

Continuous veno-venous hemofiltration

- DWI

Diffusion-weighted imaging

- HD

Hemodialysis

- HSPC

Health Surveillance and Protection Centre

- HUS

Hemolytic uremic syndrome

- IQR

Interquartile range

- MRI

Magnetic resonance imaging

- PCPC

Pediatric Cerebral Performance Category

- PCR

Polymerase chain reaction

- PD

Peritoneal dialysis

- PE

Plasma exchange

- PICU

Pediatric intensive care unit

- STEC

Shigatoxin-producing Escherichia coli

- stx

Shigatoxin

Authors’ contributions

Drs. Costigan and Raftery assisted with study design, data collection, data analysis, drafted the initial manuscript and edited all versions of the manuscript for intellectual content. Drs. Carroll and. Twomey gathered and interpreted data, contributed to drafting of the manuscript and critically reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content. Drs. Wildes and Reynolds collected data and critically reviewed the manuscript. Drs. Riordan, Cunney, Dolan, Drew, Lynch, O’Rourke, Shahwan, Stack, Sweeney and Waldron contributed to patient care and critically reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content. Prof. Awan and Dr Gorman conceptualized and designed the study, reviewed and revised the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding

Open Access funding provided by the IReL Consortium.

Data Availability

Data can be provided on request.

Declarations

Ethics approval

Ethical approval was granted by the local research and ethic committee.

Conflict of interest

Professor Awan previously served on the Alexicon medical advisory board. All other authors declare that there have no relevant interests of a financial/non-financial nature between the parties involved.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Caoimhe Costigan and Tara Raftery contributed equally as co-first authors

Atif Awan and Kathleen M. Gorman contributed equally as co-senior authors

Contributor Information

Caoimhe Costigan, Email: caoimhe.costigan@cuh.ie.

Tara Raftery, Email: tararaftery1@gmail.com.

Anne G. Carroll, Email: annegcarroll@gmail.com

Dermot Wildes, Email: dermotwildes@rcsi.ie.

Claire Reynolds, Email: Claire.reynolds@olchc.ie.

Robert Cunney, Email: Robert.cunney@cuh.ie.

Niamh Dolan, Email: Niamh.dolan@cuh.ie.

Richard J. Drew, Email: Richard.drew@cuh.ie

Bryan J. Lynch, Email: bryan.lynch@cuh.ie

Declan J. O’Rourke, Email: Declan.orourke@cuh.ie

Maria Stack, Email: maria.stack@cuh.ie.

Clodagh Sweeney, Email: clodagh.sweeney@cuh.ie.

Amre Shahwan, Email: amre.shahwan@cuh.ie.

Eilish Twomey, Email: eilish.twomey@cuh.ie.

Mary Waldron, Email: mary.waldron@cuh.ie.

Michael Riordan, Email: Michael.riordan@cuh.ie.

Atif Awan, Email: atif.awan@cuh.ie.

Kathleen M. Gorman, Email: Kathleen.gorman1@ucd.ie

References

- 1.Tarr PI, Gordon CA, Chandler WL. Shiga-toxin-producing Escherichia coli and haemolytic uraemic syndrome. Lancet. 2005;365:1073–1086. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71144-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Trachtman H, Austin C, Lewinski M, Stahl RAK. Renal and neurological involvement in typical Shiga toxin-associated HUS. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2012;8:658–669. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2012.196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gallo GE, Gianantonio CA. Extrarenal involvement in diarrhoea-associated haemolytic-uraemic syndrome. Pediatr Nephrol. 1995;9:117–119. doi: 10.1007/BF00858990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mayer CL, Leibowitz CS, Kurosawa S, Stearns-Kurosawa DJ. Shiga toxins and the pathophysiology of hemolytic uremic syndrome in humans and animals. Toxins (Basel) 2012;4:1261–1287. doi: 10.3390/toxins4111261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Orth D, Khan AB, Naim A, et al. Shiga toxin activates complement and binds factor H: evidence for an active role of complement in hemolytic uremic syndrome. J Immunol. 2009;182:6394–6400. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lynn RM, O’Brien SJ, Taylor CM, et al. Childhood hemolytic uremic syndrome, United Kingdom and Ireland. Emerg Infect Dis. 2005;11:590–596. doi: 10.3201/eid1104.040833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jacquinet S, De Rauw K, Pierard D et al (2018) Haemolytic uremic syndrome surveillance in children less than 15 years in Belgium, 2009–2015.Arch Public Heal 76.10.1186/s13690-018-0289-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Rowe PC, Walop W, Lior H, Mackenzie AM. Haemolytic anaemia after childhood Escherichia coli O 157.H7 infection: are females at increased risk? Epidemiol Infect. 1991;106:523–530. doi: 10.1017/S0950268800067583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jenssen GR, Hovland E, Bjerre A, et al. Incidence and etiology of hemolytic-uremic syndrome in children in Norway, 1999–2008 - a retrospective study of hospital records to assess the sensitivity of surveillance. BMC Infect Dis. 2014;14:1–9. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-14-265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.HSE Health Protection Surveillance Centre (2019) VTEC Infection in Ireland, 2017. Dublin: HSE HPSC

- 11.Rooney JC, Anderson RM, Hopkins IJ. Clinical and pathological aspects of central nervous system involvement in the haemolytic uraemic syndrome. J Paediatr Child Health. 1971;7:28–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.1971.tb02465.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rosales A, Hofer J, Zimmerhackl LB, et al. Need for long-term follow-up in enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli–associated hemolytic uremic syndrome due to late-emerging sequelae. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54:1413–1421. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gitiaux C, Krug P, Grevent D, et al. Brain magnetic resonance imaging pattern and outcome in children with haemolytic-uraemic syndrome and neurological impairment treated with eculizumab. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2013;55:758–765. doi: 10.1111/dmcn.12161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Matthies J, Hünseler C, Ehren R, et al. Extrarenal manifestations in shigatoxin-associated haemolytic uremic syndrome. Klin Padiatr. 2016;228:181–188. doi: 10.1055/s-0042-108444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Loos S, Aulbert W, Hoppe B, et al. Intermediate follow-up of pediatric patients with hemolytic uremic syndrome during the 2011 outbreak caused by E. coli O104:H4. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;64:1637–1643. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tavasoli A, Zafaranloo N, Hoseini R, et al. Chronic neurological complications in hemolytic uremic syndrome in children. Iran J Kidney Dis. 2019;13:32–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Giordano M, Baldassarre ME, Palmieri V et al (2019) Management of stec gastroenteritis: is there a role for probiotics? Int J Environ Res Public Health 16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Ylinen E, Salmenlinna S, Halkilahti J, et al. Hemolytic uremic syndrome caused by Shiga toxin–producing Escherichia coli in children: incidence, risk factors, and clinical outcome. Pediatr Nephrol. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s00467-020-04560-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Steinborn M, Leiz S, Rüdisser K, et al. CT and MRI in haemolytic uraemic syndrome with central nervous system involvement: distribution of lesions and prognostic value of imaging findings. Pediatr Radiol. 2004;34:805–810. doi: 10.1007/s00247-004-1289-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brown CC, Garcia X, Bhakta RT, et al. Severe acute neurologic involvement in children with hemolytic-uremic syndrome. Pediatrics. 2021;147:e2020013631. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-013631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martin DL, MacDonald KL, White KE, et al. The epidemiology and clinical aspects of the hemolytic uremic syndrome in Minnesota. N Engl J Med. 1990;323:1161–1167. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199010253231703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bale JFJ, Brasher C, Siegler RL. CNS manifestations of the hemolytic-uremic syndrome. Relationship to metabolic alterations and prognosis. Am J Dis Child. 1980;134:869–872. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1980.02130210053014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sheth KJ, Swick HM, Haworth N. Neurological involvement in hemolytic-uremic syndrome. Ann Neurol. 1986;19:90–93. doi: 10.1002/ana.410190120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hahn JS, Havens PL, Higgins JJ, et al. Neurological complications of hemolytic-uremic syndrome. J Child Neurol. 1989;4:108–113. doi: 10.1177/088307388900400206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cimolai N, Morrison BJ, Carter JE. Risk factors for the central nervous system manifestations of gastroenteritis-associated hemolytic-uremic syndrome. Pediatrics. 1992;90:616–621. doi: 10.1542/peds.90.4.616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Siegler RL. Spectrum of extrarenal involvement in postdiarrheal hemolytic-uremic syndrome. J Pediatr. 1994;125:511–518. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(94)70001-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Banatvala N, Griffin PM, Greene KD, et al. The United States national prospective hemolytic uremic syndrome study: microbiologic, serologic, clinical, and epidemiologic findings. J Infect Dis. 2001;183:1063–1070. doi: 10.1086/319269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gerber A, Karch H, Allerberger F, et al. Clinical course and the role of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli infection in the hemolytic-uremic syndrome in pediatric patients, 1997–2000, in Germany and Austria: a prospective study. J Infect Dis. 2002;186:493–500. doi: 10.1086/341940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Loos S, Ahlenstiel T, Kranz B, et al. An outbreak of shiga toxin-producing escherichia coli O104:H4 hemolytic uremic syndrome in Germany: presentation and short-term outcome in children. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55:753–759. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Siegler RL, Pavia AT, Christofferson RD, Milligan MK. A 20-year population-based study of postdiarrheal hemolytic uremic syndrome in Utah. Pediatrics. 1994;94:35–40. doi: 10.1542/peds.94.1.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Eriksson KJ, Boyd SG, Tasker RC. Acute neurology and neurophysiology of haemolytic-uraemic syndrome. Arch Dis Child. 2001;84:434–435. doi: 10.1136/adc.84.5.434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Clarke SLN, Sen ES, Ramanan AV (2016) Juvenile idiopathic arthritis-associated uveitis. Pediatr Rheumatol 14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Nathanson S, Kwon T, Elmaleh M, et al. Acute neurological involvement in diarrhea-associated hemolytic uremic syndrome. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5:1218–1228. doi: 10.2215/CJN.08921209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pape L, Hartmann H, Bange FC, et al. Eculizumab in typical hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS) with neurological involvement. Medicine (Baltimore) 2015;94:e1000. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000001000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Giordano P, Netti GS, Santangelo L, et al. A pediatric neurologic assessment score may drive the eculizumab-based treatment of Escherichia coli-related hemolytic uremic syndrome with neurological involvement. Pediatr Nephrol. 2019;34:517–527. doi: 10.1007/s00467-018-4112-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Khalid M, Andreoli S. Extrarenal manifestations of the hemolytic uremic syndrome associated with Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC HUS) Pediatr Nephrol. 2019;34:2495–2507. doi: 10.1007/s00467-018-4105-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dundas S, Murphy J, Soutar RL, et al. Effectiveness of therapeutic plasma exchange in the 1996 Lanarkshire Escherichia cell O157:H7 outbreak. Lancet. 1999;354:1327–1330. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)01251-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Colic E, Dieperink H, Titlestad K, Tepel M. Management of an acute outbreak of diarrhoea-associated haemolytic uraemic syndrome with early plasma exchange in adults from southern Denmark: an observational study. Lancet. 2011;378:1089–1093. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61145-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kielstein JT, Beutel G, Fleig S, et al. Best supportive care and therapeutic plasma exchange with or without eculizumab in Shiga-toxin-producing E. coli O104:H4 induced haemolytic-uraemic syndrome: an analysis of the German STEC-HUS registry. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2012;27:3807–3815. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfs394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Menne J, Nitschke M, Stingele R, et al. Validation of treatment strategies for enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli O104:H4 induced haemolytic uraemic syndrome: case-control study. BMJ. 2012;345:e4565. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e4565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gianviti A, Perna A, Caringella A, et al. Plasma exchange in children with hemolytic-uremic syndrome at risk of poor outcome. Am J Kidney Dis. 1993;22:264–266. doi: 10.1016/S0272-6386(12)70316-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Percheron L, Gramada R, Tellier S, et al. Eculizumab treatment in severe pediatric STEC-HUS: a multicenter retrospective study. Pediatr Nephrol. 2018;33:1385–1394. doi: 10.1007/s00467-018-3903-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lapeyraque A-L, Malina M, Fremeaux-Bacchi V, et al. Eculizumab in severe shiga-toxin–associated HUS. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2561–2563. doi: 10.1056/nejmc1100859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fivush BA, Jabs K, Neu AM, et al. Chronic renal insufficiency in children and adolescents: the 1996 annual report of NAPRTCS. Pediatr Nephrol. 1998;12:328–337. doi: 10.1007/s004670050462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fiser DH, Tilford JM, Roberson PK. Relationship of illness severity and length of stay to functional outcomes in the pediatric intensive care unit: a multi-institutional study. Crit Care Med. 2000;28:1173–1179. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200004000-00043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bauer A, Loos S, Wehrmann C, et al. Neurological involvement in children with E. coli O104:H4-induced hemolytic uremic syndrome. Pediatr Nephrol. 2014;29:1607–1615. doi: 10.1007/s00467-014-2803-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ardissino G, Tel F, Testa S, et al. A simple prognostic index for Shigatoxin-related hemolytic uremic syndrome at onset: data from the ItalKid-HUS network. Eur J Pediatr. 2018;177:1667–1674. doi: 10.1007/s00431-018-3198-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Keenswijk W, Raes A, De Clerck M, Vande Walle J. Is plasma exchange efficacious in shiga toxin-associated hemolytic uremic syndrome? A narrative review of current evidence. Ther Apher Dial. 2019;23:118–125. doi: 10.1111/1744-9987.12768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Walsh PR, Johnson S. Eculizumab in the treatment of Shiga toxin haemolytic uraemic syndrome. Pediatr Nephrol. 2019;34:1485–1492. doi: 10.1007/s00467-018-4025-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Keenswijk W, Raes A, Vande Walle J. Is eculizumab efficacious in Shigatoxin-associated hemolytic uremic syndrome? A narrative review of current evidence. Eur J Pediatr. 2018;177:311–318. doi: 10.1007/s00431-017-3077-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schwartz J, Padmanabhan A, Aqui N et al (2016) Guidelines on the use of therapeutic apheresis in clinical practice—evidence-based approach from the Writing Committee of the American Society for Apheresis: the Seventh Special Issue. J Clin Apher 31:149–162 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 52.Ağbaş A, Göknar N, Akıncı N, et al. Outbreak of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia-coli-associated hemolytic uremic syndrome in Istanbul in 2015: outcome and experience with eculizumab. Pediatr Nephrol. 2018;33:2371–2381. doi: 10.1007/s00467-018-4033-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Monet-Didailler C, Chevallier A, Godron-Dubrasquet A, et al. Outcome of children with Shiga toxin-associated haemolytic uraemic syndrome treated with eculizumab: a matched cohort study. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2021;35:2147–2153. doi: 10.1093/NDT/GFZ158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Delmas Y, Vendrely B, Clouzeau B, et al. Outbreak of Escherichia coli O104:H4 haemolytic uraemic syndrome in France: outcome with eculizumab. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2014;29:565–572. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gft470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Garg AX, Suri RS, Barrowman N, et al. Long-term renal prognosis of diarrhea-associated hemolytic uremic syndrome: a systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. J Am Med Assoc. 2003;290:1360–1370. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.10.1360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Roche A, Poo P, Maristany M, et al. Haemolytic-uraemic syndrome: neurologic symptoms, neuroimaging and neurocognitive outcome. Neuroimaging Clin - Comb Res Pract. 2011 doi: 10.5772/23649. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schlieper A, Orrbine E, Wells GA, et al. Neuropsychological sequelae of haemolytic uraemic syndrome. Arch Dis Child. 1999;80:214–220. doi: 10.1136/adc.80.3.214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data can be provided on request.