Abstract

Objective:

To present the incremental cost from the payer’s perspective and effectiveness of couples’ family planning counseling (CFPC) with long-acting reversible contraception (LARC) access integrated with couples’ voluntary HIV counseling and testing (CVCT) in Zambia. This integrated program is evaluated incremental to existing individual HIV counseling and testing and family planning services.

Design:

Implementation and modeling

Setting:

55 government health facilities in Zambia

Subjects:

Patients in government health facilities

Intervention:

Community health workers and personnel promoted and delivered integrated CVCT+CFPC from March 2013-September 2015.

Main outcome measures:

We report financial costs of actual expenditures during integrated program implementation and outcomes of CVCT+CFPC uptake and LARC uptake. We model primary outcomes of cost-per-: adult HIV infections averted by CVCT, unintended pregnancies averted by LARC, couple-years of protection against unintended pregnancy by LARC, and perinatal HIV infections averted by LARC. Costs and outcomes were discounted at 3%/year.

Results:

Integrated program costs were $3,582,186 (2015 USD), 82,231 couples received CVCT+CFPC, and 56,409 women received LARC insertions. The program averted an estimated 7,165 adult HIV infections at $384/adult HIV infection averted over a 5-year time horizon. The program also averted 62,265 unintended pregnancies and was cost-saving for measures of cost-per-unintended pregnancy averted, cost-per-couple-year of protection against unintended pregnancy, and cost-per-perinatal HIV infection averted assuming 3 years of LARC use.

Conclusions:

Our intervention was cost-savings for CFPC outcomes and CVCT was effective and affordable in Zambia. Integrated couples-focused HIV and family planning was feasible, affordable, and leveraged HIV and unintended pregnancy prevention.

Keywords: cost-effectiveness, couples, family planning, HIV, integrated programs, Zambia

INTRODUCTION

Population growth is a driver of poverty in sub-Saharan Africa where the average woman bears more than five children[1]. Family planning (FP) reduces unintended pregnancy, abortion, maternal death, and perinatal HIV infections when unintended pregnancies are averted in HIV-positive women[2]. Zambia is one of only three countries in Africa with increasing fertility rates, rising from 5.15 in 2009 to 5.67 in 2016[3]. Unmet need for family planning in Zambia is 22% among married women[4]. In particular, long-acting reversible contraceptives (LARC) such as the non-hormonal copper-T intrauterine device (IUD) and subcutaneous hormonal implants are highly effective, with typical-use failure rates of <1%/year[5]. However, they are used by just 1.2% and 5.7% of Zambian women with stable partners, respectively[6], and access to LARC methods continues to be limited by a lack of trained providers and necessary equipment[7].

Unmet need for FP is often higher among HIV-positive women than the general population[8–10]. In sub-Saharan Africa, FP and HIV programs serve similar populations, primarily cohabiting heterosexual couples. The integration of FP and HIV services is supported by the World Health Organization (WHO), the United Kingdom Department for International Development, and the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) to improve health outcomes, client satisfaction, resource use, and to reduce stigma[11–13]. Sponsors have urgently called for development and evaluation of adaptable integrated models[11].

Previous studies have explored costs and/or cost-effectiveness of HIV services integrated with sexual and reproductive health services. Sweeney et al conducted a systematic review which concluded that integration of HIV with sexual and reproductive health services was cost-effective relative to standard of care alternatives[14]. Obure et al reviewed the costs of delivering six HIV service programs integrated with sexual reproductive health services in resource limited settings and similarly concluded that savings are possible given more efficient allocation of human and capital resources[15]. In Kenya, a home-based intervention where pregnant women and their partners received HIV counseling and testing was found to be cost-effective over a 10 year time horizon[16]. However, no previously studies have evaluated couples-focused interventions integrating HIV and FP.

Couples’ voluntary HIV counseling and testing (CVCT), in which both partners participate jointly in pre- and post-test counseling with mutual disclosure and development of prevention strategies based on joint HIV test results, is a cost-effective and affordable prevention strategy [17–19] endorsed by WHO, PEPFAR, Global Fund, and the Government of Zambia[20–23]. This intervention reduces HIV risk by increasing condom use in discordant couples and decreasing outside sex partners and is an entry point into FP[18, 24, 25].

From 2013–2015, the Zambia Emory HIV Research Project (ZEHRP) was supported by provide CVCT plus couples’ FP counseling (CFPC) with a focus on fertility-goal based LARC promotion combined with service provision was introduced in subset of clinics. The objective of this analysis is to report on the incremental cost and effectiveness of the integrated CVCT+CFPC program.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Integrated CVCT and CFPC program development and operations

HIV counselors were trained to provide CVCT using US CDC counselor training materials following WHO guidelines[20]. Services were promoted to heterosexual women and their partners in 55 government facilities in seven Zambian cities using a combination of mass media and promotions by community health workers and influential network agents (opinion leaders within communities), and overtime pay for weekday and weekend service provision off-duty government health facility staff[26, 27].

CFPC training materials and procedures were developed during the first 6 months of the program based on prior research[27] and adapted for use in government clinics. CFPC counseling was based on stated fertility goals with access to the full range of contraceptive options. LARC methods were emphasized for couples wishing to delay pregnancy for 2 or more years. After government clinics had a full complement of staff trained in CVCT+CFPC promotion and provision and LARC insertion and removal, staff from individual HIV testing and counseling, FP, outpatient, antiretroviral treatment, and infant vaccination departments were provided $1 USD for each referral that resulted in a CVCT+CFPC visit or a LARC client. These reimbursements were provided to the health care facilities who distributed them to providers based on their performance with their regular pay.

Fertility-goal-based FP counseling was also offered to women attending FP alone with referral for CVCT+CFPC. Conversely, couples attending CVCT+CFPC who did not request LARC due to time constraints or the desire to think about options before deciding were referred for a later date.

The addition of CFPC to the CVCT training curriculum required one additional day of didactic training and added an average of 5 minutes to the pre-test counseling flip-chart guided group session and 2 minutes (for couples not eligible for LARC promotion) to 10 minutes (for couples educated about and offered LARC methods) to flip-chart guided post-test counseling.

Experienced ZEHRP staff trained government counselors and nurses to provide the integrated program in their clinics. Initially, counselors previously trained in CVCT received CFPC training, and subsequently new counselors received CVCT+CFPC training concurrently. ZEHRP staff also trained community health workers, influential network agents, and clinic staff to promote the integrated program in the clinic and community. Data shown are from March 2013-September 2015.

Integrated program costs

We report costs following Global Heath Cost Consortium guidance [28]. We report incremental financial costs of actual expenditures to add CVCT+CFPC into existing services. We report the additional costs incurred without including costs of the existing programs. This is a primary costing study of actual resources used (i.e., costs related to integrated service provision were observed and not modeled). Costs reflect the cost of scaling up CFPC with LARC training integrated with CVCT services. Cost data were recorded by ZEHRP staff during program implementation and entered in AccPac (Sage Group). Expenditures are reported both by activity (CVCT+CFPC service delivery, LARC service delivery, and training and monitoring and evaluation (M&E)) and by category in 2015 United States Dollars (USD). We apply straight-line depreciation for capital goods resulting in an annual cost over the life of the project[29].

Observed integrated program outcomes

ZEHRP staff recorded the number of nurses who completed didactic and practicum LARC training and were certified by two physicians accredited by the Ministry of Health, and the number of counselors trained in CVCT+CFPC. Clinic staff were given logbooks to record service delivery outcomes (couples receiving CVCT and CFPC, HIV serostatus results, IUD/implant insertions, removals and replacements) and referral information. Data was entered into a Microsoft Access database for data management, cleaning, quality control, M&E, and analysis by ZEHRP staff.

Cost-effectiveness and modeling analyses

We adhere to Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards[30] for cost-effectiveness analyses. All costs and outcomes are discounted at 3%/year. The counterfactual comparison in our analyses comprised the services offered prior to our implementation for which outcomes were abstracted from existing medical records: individual HIV testing and counseling and separate FP programs serving women only and generally not offering LARC with no demand creation activities.

Modeling outcomes and cost-effectiveness of CVCT

We used a compartmental model transitioning couples between HIV and/or antiretroviral treatment use status to estimate outcomes of adult HIV infections averted and cost-per infection-averted over a five-year time horizon. Details of the model and its parameters, which were derived from a study in 73 Zambian government clinics among 207,428 couples (roughly 414,856 individuals) in Zambia, have been published[19] and key parameters are shown in Table 3. Briefly, we apply the HIV seroincidence rates in patients undergoing CVCT and individual VCT (the counterfactual) by couple serostatus and ART use status and the distribution of ART use among CVCT and individual VCT patients observed in the previous study [19]. In this model, we evaluated the effect of possible differential loss to follow-up, informative censoring, and confounding when using observational data to estimate the effect of treatment and found that our model was robust in sensitivity analyses[19]. Here, we model the HIV prevention impact among the 108,399 couples tested in the present integrated program, 6.3% of whom were discordant and 80.4% of whom were concordant negative. We apply the costs of service delivery and training observed during our integrated program implementation (Table 1) and did not include any additional costs to the healthcare system such as the future lifetime costs of adult HIV infection.

Table 3.

Model Parameters for the Integrated CVCT and CFPC Intervention

| Standard of care control: HIV seroincidence rates in individual VCT, cases per 100 PY | |

| Among non-ART using HIV discordant couples | 13.00 (1) |

| Intervention: HIV seroincidence rates after CVCT, cases per 100 PY | |

| Among non-ART using HIV discordant couples | 4.82 (1) |

| ART use | |

| Among HIV positive adults after CVCT (intervention) | 50.6% (1)a |

| Number of couples tested | 108,399b |

| Proportion concordant negative | 80.4%b |

| Costs to deliver CVCT: Service delivery + training costs | $3,191,571b |

ART: antiretroviral treatment; CVCT: couples’ voluntary HIV counseling and testing; PY: person-year; PMTCT: prevention of mother-to-child transmission; CYP: couple-years of protection; IUD: intrauterine device, USD United States Dollar, LARC, long-acting reversible contraception

With 5% additional uptake per year

Values observed in present study

Table 1.

Allocation of Financial Costs of Actual Expenditures by Activity to Implement the Integrated Program, 2015 USD, March 2013 - September 2015

| Total (col %) | CVCT & CFPC Service Delivery (col %) | LARC Service Delivery (col %) | Training†† (col %) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full time program staff | $339,530 (9%) | $339,530 (29%) | ||

| Part time government clinic staff | $833,904 (23%) | $567,775 (28%) | $130,495 (33%) | $135,633 (11%) |

| Advocacy and promotions | $633,616 (18%) | $551,251 (27%) | $82,364 (21%) | |

| Recruitment | $113,700 (3%) | $92,449 (5%) | $21,251 (5%) | |

| Consumables | $42,999 (1%) | $34,964 (2%) | $8,035 (2%) | |

| HIV test kits | $13,217 (0.4%) | $10,747 (1%) | $2,469 (1%) | |

| Travel for training | $266,306 (7%) | $266,306 (22%) | ||

| International staff | $290,350 (8%) | $162,718 (8%) | $31,663 (8%) | $95,969 (8%) |

| Shared expenses† | $1,048,565 (29%) | $587,647 (29%) | $114,338 (29%) | $346,580 (29%) |

| Total Costs USD | $3,582,186 | $2,007,552 | $390,616 | $1,184,018 |

| Percent of total (row%): | 56% | 11% | 33% |

Communication, automobiles (annualized), supplies, equipment, administrative travel, field rentals, field facilities

Training costs also include monitoring and evaluation costs

Financial costs presented here are undiscounted; all costs were incurred by the funder (DFID)

CVCT: couples’ voluntary HIV counseling and testing; CFPC: couples’ family planning counseling; LARC: long-acting reversible contraception; USD: United States Dollar

Modeling outcomes and cost-effectiveness of LARC uptake

Among women who selected LARC, we calculated counts and costs-per: pregnancies averted, cumulative couple-years of protection (CYP, a commonly used estimate of the length of contraceptive protection against pregnancy provided per unit of that method[31]) gained, and perinatal infections averted in HIV-positive women. All LARC impact and cost-effectiveness model parameters are shown in Table 3 and described below. The counterfactual applied the baseline distribution of contraceptive method use by women the 56,409 women who had received standard of care FP services prior to LARC uptake in our integrated program.

To calculate pregnancies averted by LARC use, we used published estimates of annual pregnancy risk for each method of contraception[5] and assume that all pregnancies among contraceptive users are unintended. We conservatively assumed three years of LARC use before discontinuation. To estimate CYP gained after LARC uptake, we used published CYP estimates[31]. Finally, we calculated perinatal infections averted in HIV-positive women who initiated LARC, assuming that 17% of women were HIV-positive (as observed in this study) and 5% of HIV-positive women who become pregnant transmit to their child (as observed in Zambian PMTCT program data[12]). Using published data for pregnancy outcomes, we assume that 53% of pregnancies end in live birth, 14% in miscarriage/stillbirth/death, and 33% in abortion (including spontaneous and induced, the latter being legal in Zambia)[32].

To estimate cost-effectiveness measures, we included the costs to deliver LARC in the integrated program (service delivery and training). We also included additional costs to the healthcare system including the costs of: 1) live birth (estimated using data from Zambia and including costs of personnel, administration, training, quality control, medical supplies, equipment, and pharmaceuticals, infrastructure, and utilities[33]); 2) miscarriage/stillbirth/death (estimated using data from low and middle income countries and including costs for facility stay, personnel, medications, supplies, equipment, disinfection, and services[34, 35]); 3) abortion (estimated using data from Zambia and including costs of safe and unsafe abortions, medications for medical abortion, manual vacuum aspiration for surgical abortion, treatment for incomplete abortion, abortion complications, drugs, equipment, diagnostics, personnel, and administration[36]); 4) antenatal care (assuming four visits for women whose pregnancies ended in live birth and two visits for women whose pregnancies end in miscarriage/stillbirth/death, and including costs of personnel, drugs and consumables, equipment, and overhead/facilities[37]); 5) PMTCT for HIV-negative women (estimated using data from Zambia and including costs of repeat HIV testing (three HIV tests per guidelines for women with live births and one HIV test for women with miscarriage/ stillbirth/death), personnel, recurrent inputs and services, capital, training, and supervision[38]); and 6) PMTCT for HIV-positive women (estimated using data from Zambia and including costs of receiving nevirapine prophylaxis, one-time infant HIV testing, personnel, recurrent inputs and services, capital, training, and supervision)[38]).

We did not include the future costs of perinatal HIV infection to the health care system (only costs through PMTCT). We assume no antenatal care or PMTCT costs for women whose pregnancies ended in abortion, and PMTCT costs were only applied to estimates of cost-per-perinatal HIV infection averted. All costs are in 2015 USD.

One-way sensitivity analyses

We conducted one-way sensitivity analyses on all model variables by varying each parameter by +/−20% and applying a range of discounting rates (2%, 5%, 7%). Inputs which most influence model results are reported.

Probabilistic sensitivity analyses

Because of uncertainty around healthcare system costs, we conducted a Monte Carlo simulation probabilistic sensitivity analyses using SAS v9.4 (Cary, NC) with 1,000 draws (using a uniform distribution, defined at +/−50% of the primary analysis estimates) for each cost parameter of interest. The median and 95% confidence interval of those simulated estimates were calculated. A uniform distribution was selected to not place a functional form on the parameter estimates in sensitivity analyses, reflecting a large degree of uncertainty around the estimates.

Demand creation through cross-referral referral between CVCT+CFPC and LARC

We compared LARC use prior to implementation of CVCT+CFPC in the first six months (April-September 2013) to the last six months (July-December 2015) to estimate the impact of referrals from CVCT+CFPC on LARC uptake. Belatedly, in December 2014 the converse measurement (proportion of clients requesting LARC in FP clinics who reported prior CVCT+CFPC) was added to LARC logbooks and reported for the last year of the program.

Ethics

The Emory Institutional Review Board determined that that no ethical approval was required for anonymized data collected during program service delivery (non-research).

RESULTS

Integrated program costs (Table 1)

The total program cost was $3,582,186 USD. Key costs for CVCT+CFPC and LARC service delivery included part-time staffing, and advocacy/promotional activities. Key costs for training included full-time staff and travel. Expenses shared across activities were a substantial part of the overall budget.

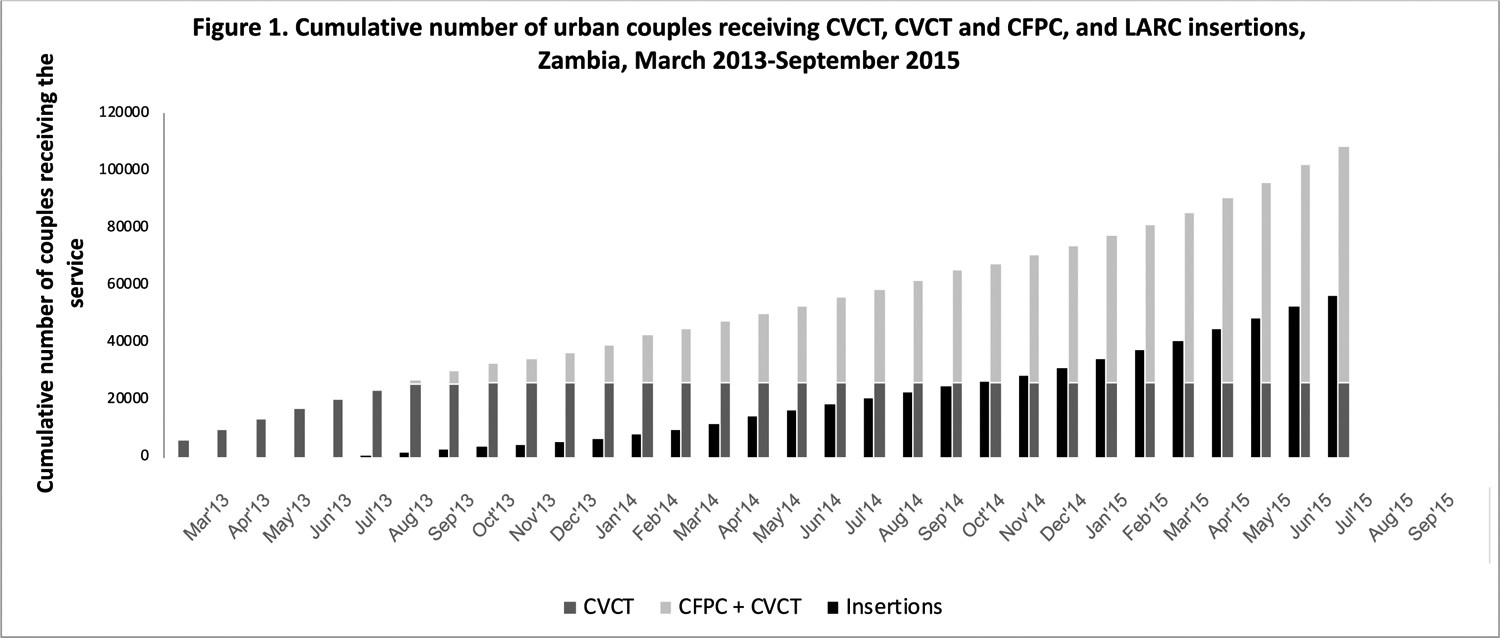

Integrated program outcomes (Table 2, Figure 1)

Table 2.

Integrated Program Outcome Measures, March 2013 - September 2015

| Training Outcomes | |

| Number of clinics providing CVCT and family planning services | 55 |

| Number of counselors trained | 391 |

| Number of nurses trained in IUD/implant insertions/removals | 257 |

| Number of community health workers and influence network agents trained in promotions | 3,999 |

| Couples’ Voluntary HIV Testing (CVCT) Outcomes | |

| Number of couples tested | 108,399 |

| M-F+ | 3,891 |

| M+F- | 2,972 |

| M+F+ | 14,419 |

| M-F- | 87,117 |

| Couples’ Family Planning (CFPC) Outcomes | |

| Number of couples provided with CFPC and CVCT | 82,231 |

| Total LARC insertions | 56,409 |

| Total IUD insertions | 5,417 |

| Total implant insertions | 50,992 |

| Total LARC removals | 19,415 |

| Total IUD removals | 2,187 |

| Total implant removals | 17,228 |

CVCT: couples’ voluntary HIV counseling and testing; CFPC: couples’ family planning counseling; LARC: long-acting reversible contraception; IUD: intrauterine device; implant: Jadelle

Outcomes presented here are undiscounted

Figure 1.

Cumulative number of couples receiving CVCT, CVCT/CFPC, and LARC, Zambia, March 2013-September 2015.

CVCT: couples’ voluntary HIV counseling and testing; CFPC: couples’ family planning counseling; LARC: long-acting reversible contraception; IUD: intrauterine device

The integrated program was delivered in 55 urban facilities in seven cities. We trained n=391 counselors, n=257 nurses in LARC delivery, and n=3,999 promotional agents. Of 108,399 couples tested for HIV, 16% of men were HIV-positive, 17% of women were HIV-positive, and 6% of couples were HIV discordant. Of couples who received CVCT, 82,231 also received CFPC. LARC services included insertion (n=56,409, 10% IUD and 90% implant) and removal/replacement (n=19,415) (11% IUD and 89% implant). Prior to the integrated program, most women were using injectables (30%) or no modern method of contraception (46%) (data not shown). The majority of LARC removals were methods inserted prior to initiation of our program[39]. CVCT uptake, CVCT+CFPC uptake, and LARC insertions are shown over calendar time in Figure 1.

CVCT/CFPC client demographics (data not tabled)

The average age in years for men was 33.5 (standard deviation, SD=10.3), for women was 27.8 (SD=9.0), and 78% of women and 64% of men reported ever previously testing for HIV. Almost one quarter (24%) of couples reported previously receiving joint CVCT services, and 22% of women reported current pregnancy. 98% of couples reported cohabiting for longer than three months (5.9 years (SD=6.8)).

Modeled outcomes and cost-effectiveness (Table 4)

Table 4.

Modeled outcome and cost-effectiveness estimates

| Adult HIV infections averted by CVCT | 7,165 |

| Cost-per-adult infection averted by CVCT† | $384 |

| Unintended pregnancies averted by CFPC among LARC users | 62,265 |

| Cost-per-unintended pregnancy averted by CFPC among LARC users†† | dominant |

| Cumulative CYP gained by CFPC among LARC users | 387,726 |

| Cost-per-CYP gained by CFPC among LARC users††† | dominant |

| Perinatal HIV infections averted by CFPC among LARC users * | 842 |

| Cost-per-perinatal HIV infection averted by CFPC among LARC users†††† | dominant |

Assumes 17% of urban women are HIV+ (see Table 2), 53% of pregnancies result in live births, and 5% of HIV+ pregnant women transmit to their child

CVCT: couples’ voluntary HIV counseling and testing; QALY: quality-adjusted life years; FP: family planning; IUD: intrauterine device; LARC: long-acting reversible contraception; CYP: couple years of protection; HC: health care; PMTCT: prevention of mother-to-child transmission

Cost-savings results are indicated as ‘dominant’

3%/year discounting applied to all costs and outcomes

Incremental cost-effectiveness ratios are calculated as:

[discounted service delivery and training costs to incrementally add CVCT+CFPC to existing standard of care VCT and FP services (Table 1)] / [discounted total number of adult HIV infections averted by CVCT versus standard of care VCT]

[discounted service delivery and training costs to incrementally add CVCT+CFPC to existing standard of care VCT and FP services (Table 1) plus incremental pregnancy outcome costs to the health care system (Table 3)] / [discounted total number of unintended pregnancy averted by CFPC among LARC users versus standard of care FP]

[discounted service delivery and training costs to incrementally add CVCT+CFPC to existing standard of care VCT and FP services (Table 1) plus incremental pregnancy outcome costs to the health care system (Table 3)] / [discounted total number of CYP gained by CFPC among LARC users versus standard of care FP]

[discounted service delivery and training costs to incrementally add CVCT+CFPC to existing standard of care VCT and FP services (Table 1) plus incremental pregnancy outcome and PMTCT costs to the health care system (Table 3)] / [discounted total number of perinatal HIV infections averted by CFPC among LARC users versus standard of care FP]

7,165 adult HIV infections were averted over a five-year time horizon, corresponding to 56% of new infections averted. The cost-per-HIV infection averted was $384. Among those selecting LARC, 62,265 pregnancies were averted, 387,726 CYPs were gained, and 842 perinatal HIV infections were averted. Cost-per-pregnancy averted, -CYP gained, and -perinatal HIV infection averted were cost-saving.

Sensitivity analyses

One-way sensitivity analyses indicated our models were most sensitive to HIV seroincidence rates among concordant negative couples before CVCT (reducing the rate to 0.8/100PY increased the cost-per-adult HIV infection estimate by 65%). Our model was also sensitive to years of LARC use (assuming 2 years of LARC use increased the cost-per-perinatal HIV infection averted by 54%, though it was still cost-saving). Our findings were robust to probabilistic sensitivity analyses.

Demand creation through referral between CVCT+CFPC and LARC

In December 2014, 41% of clients requesting LARC in FP clinics reported prior CVCT+CFPC, rising to 54% in December 2015 when service integration and mutual referral mechanisms were fully optimized. In the first six months of the program, 4% of CVCT couples had already received a LARC method, rising to 21% in December 2015, reflecting improved referrals from FP clinics to CVCT services.

DISCUSSION

We show that an innovative, integrated model combining CFPC and CVCT with access to LARC leveraged prevention of adult and perinatal HIV and unintended pregnancy and increased CYP. In a 2017 systematic review, though promoting integrated HIV and FP services to women and couples was highlighted as important, no studies described couples-focused programs[40]. This is a missed opportunity since engaging couples in HIV testing is a high impact HIV prevention strategy [17, 19, 24, 25, 41] that enables couples to discuss fertility goals in light of their HIV status, and couples’ FP counseling improves LARC knowledge and uptake[27].

Our cost-per-adult HIV infection averted estimates are comparable with other highly cost-effective interventions including individual VCT (estimated in a previous systematic review of studies in sub-Saharan Africa at $1,315/HIV infection[42] and $483/HIV infection averted for either individual or couples testing in Kenya[42, 43]). Similarly, our cost-per-perinatal HIV infection averted via FP findings (cost-savings) are comparable to those from a systematic review ($663/perinatal HIV infection averted via FP)[42]. For further context, another, more recent systematic review of 60 studies reporting the cost-effectiveness of HIV prevention interventions in Africa, median cost-per-HIV infection averted have been estimated for PMTCT via ART ($1,144/HIV infection averted), pre-exposure prophylaxis ($13,267/ HIV infection averted), male circumcision ($2,965/HIV infection averted), treatment-as-prevention interventions ($7,903/HIV infection averted)[44].

We found that CFPC was cost-saving in preventing unintended pregnancy, and other studies of have found similar findings. A modeling study in Uganda of universal access to modern contraception compared to status quo found the hypothetical program averted unintended pregnancies at a low cost [45]. A hypothetical study of scaling up a new diaphragm in South Africa lead to a cost-per-unintended pregnancy averted of $153 from the payers perspective [46] and another modeling study found self-injectable contraception versus facility-based administration in Uganda to be cost-effective ($15/unintended pregnancy averted) [47]. Relatively few studies have focused on integration of HIV services specifically with FP services (and none focus on couples). In a 2017 systematic review, while integrated HIV and FP services were associated with a higher prevalence of modern contraceptive use and knowledge, the authors found insufficient evidence to evaluate program impact on unintended pregnancy or cost-effectiveness[40]. Only one study, a randomized controlled trial in Kenya[48], reported integrated HIV/FP program costs. In this trial, a ‘One-stop shop’ intervention integrated family planning (counseling and full method mix access including LARC) into HIV clinics, while control HIV clinics referred clients to family planning services within the same health facility. Effective contraceptive use increased from 17% to 37% in intervention clinics versus 21% to 30% in control clinics (p<0.05). The authors estimated a cost-per-pregnancy averted of $1,368 [48].

Our estimates of cost-per-CYP gained from LARC methods were cost-saving. This is in-line with literature estimating a cost-per-CYP in Zambia of $9 for the IUD and $15 for the implant[39]. In Ethiopia, Uganda, Burkina Faso, and Cameroon, cost-per-CYP was lowest for the IUD ($4-$23) and higher for oral contraceptive pills ($17-$31) and implants and injectables ($20-$58)[49]. Data from 13 USAID tier one priority reproductive health countries estimated that the cost-per-CYP was <$2 for the copper IUD and roughly $4 for Sino-Implant, $7 for injectables and oral contraceptive pills, and $8 for Jadelle[50]. Most studies have found costs-per-CYP to be lowest for the copper IUD and higher for the implant versus the copper IUD (largely due to differences in commodity costs[51]), which is important given that 90% of LARC uptake in this study was implant. Other LARC implementation studies in Africa have similarly found higher uptake of the implant versus the IUD[7, 52], a trend that has been reversed with provider re-training on IUD insertion and targeted efforts to increase IUD knowledge among clients using mass media and community-based efforts[53, 54]. These targeted efforts are important since the IUD is less well-known relative to the implant in much of sub-Saharan Africa[55–59].

An evaluation of peer-reviewed literature conducted by FHI360 highlighted facilitators for successfully integrated HIV and FP programs[60] including government and community leadership, evidence-based services tailored to local contexts, capacity building among providers and promoters with task-shifting, M&E systems for integrated program data collection, strong referral systems and supply chains, and involvement of men and high-risk groups. We recently published implementation and operations research conducted during our implementation in the 55 urban clinics described here as well as 215 rural clinics and report that with shifting of services from weekend to weekday, task-shifting, and well-coordinated training of providers plus facility- and community-based demand creation, CVCT+CFPC was highly feasible [61].

Limitations of our study include that we did not collect extensive couple-level demographics to explore predictors of uptake. Recognizing that many clients needed time to consider their options, we belatedly added queries about prior CVCT+CFPC to LARC data tools and prior LARC use to CVCT+CFPC tools. We did not include cost to patients (the societal perspective) and second and third order transmission benefits are also not captured in this model; thus are likely underestimating cost-effectiveness estimates.

CONCLUSIONS

Ours is one of very few studies to provide cost-effectiveness evidence supporting a novel integrated FP and HIV testing program with a focus on couples and LARC methods. Our intervention was cost-savings for the CFPC outcomes modeled. Additionally, the estimated cost-per-HIV infection averted due to CVCT is low compared to other HIV prevention interventions and, as we have demonstrated [19] affordable in Zambia. FP and HIV services will need to coalesce around funding, promotions, service delivery, and M&E. We recommend future integrated programs focus on fertility-goal based LARC promotion, engage couples, ensure accessible services alongside demand creation, and conduct cost-effectiveness evaluations. In Zambia, ouir work allowed for development of a model and tools for national monitoring of couple-focused and integrated HIV and FP services. This model is highly adaptable and could be explored in other locales in sub-Saharan Africa.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to all of the participants who made this study possible including staff and counselors at the government clinics, all ZEHRP staff, the District Health Management Teams, and the Ministry of Health in Zambia. We would also like to thank our funding agencies for their support.

Conflicts of interest and sources of support:

The authors have no conflicts of interest. This work presented in this document was funded by the UK Department for International Development. Additional support was provided from the National Institute of Child Health and Development (NICHD R01 HD40125); National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH R01 66767; K01 MH107320); the AIDS International Training and Research Program Fogarty International Center (D43 TW001042); the Emory Center for AIDS Research (P30 AI050409); National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID R01 AI51231; NIAID R01 AI64060; NIAID R37 AI51231). The funders had no role in design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Meetings at which parts of the data were presented: HIV Research for Prevention (R4P), Chicago, Illinois, United States, 17–21 October, 2016

REFERENCES

- 1.Bongaarts J Human population growth and the demographic transition. Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society of London Series B, Biological sciences 2009; 364(1532):2985–2990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tsui AO, McDonald-Mosley R, Burke AE. Family planning and the burden of unintended pregnancies. Epidemiologic reviews 2010; 32:152–174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.IndexMundi. Zambia Total fertility rate. In; 2016.

- 4.FP 2020. Zambia. In; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 5.CDC. Effectiveness of Family Planning Methods. In; 2017.

- 6.United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Trends in Contraceptive Use Worldwide 2015. In; 2015.

- 7.Duvall S, Thurston S, Weinberger M, Nuccio O, Fuchs-Montgomery N. Scaling up delivery of contraceptive implants in sub-Saharan Africa: operational experiences of Marie Stopes International. Global health, science and practice 2014; 2(1):72–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wekesa E, Coast E. Contraceptive need and use among individuals with HIV/AIDS living in the slums of Nairobi, Kenya. International journal of gynaecology and obstetrics: the official organ of the International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics 2015; 130 Suppl 3:E31–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wanyenze RK, Matovu JK, Kamya MR, Tumwesigye NM, Nannyonga M, Wagner GJ. Fertility desires and unmet need for family planning among HIV infected individuals in two HIV clinics with differing models of family planning service delivery. BMC women’s health 2015; 15:5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jhangri GS, Heys J, Alibhai A, Rubaale T, Kipp W. Unmet need for effective family planning in HIV-infected individuals: results from a survey in rural Uganda. The journal of family planning and reproductive health care 2012; 38(1):23–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.USAID. Promoting Integration of Family Planning into HIV and AIDS Programming. In; 2016.

- 12.World Health Organization. Strengthening the Linkages between Family Planning and HIV/AIDS Policies, Programs, and Services. In; 2009.

- 13.Druce N, Dickinson C, Attawell K, Campbell White A, Standing H. In. London, England: DFID; 2006.

- 14.Sweeney S, Obure CD, Maier CB, Greener R, Dehne K, Vassall A. Costs and efficiency of integrating HIV/AIDS services with other health services: a systematic review of evidence and experience. Sex Transm Infect 2012; 88(2):85–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Obure CD, Sweeney S, Darsamo V, Michaels-Igbokwe C, Guinness L, Terris-Prestholt F, et al. The Costs of Delivering Integrated HIV and Sexual Reproductive Health Services in Limited Resource Settings. PLoS One 2015; 10(5):e0124476–e0124476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sharma M, Farquhar C, Ying R, Krakowiak D, Kinuthia J, Osoti A, et al. Modeling the Cost-Effectiveness of Home-Based HIV Testing and Education (HOPE) for Pregnant Women and Their Male Partners in Nyanza Province, Kenya. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2016; 72 Suppl 2(Suppl 2):S174–S180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dunkle KL, Stephenson R, Karita E, Chomba E, Kayitenkore K, Vwalika C, et al. New heterosexually transmitted HIV infections in married or cohabiting couples in urban Zambia and Rwanda: an analysis of survey and clinical data. Lancet (London, England) 2008; 371(9631):2183–2191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Allen S, Tice J, Van de Perre P, Serufilira A, Hudes E, Nsengumuremyi F, et al. Effect of serotesting with counselling on condom use and seroconversion among HIV discordant couples in Africa. Bmj 1992; 304(6842):1605–1609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wall KM, Inambao M, Kilembe W, Karita E, Vwalika B, Mulenga J, et al. HIV testing and counselling couples together for affordable HIV prevention in Africa. Int J Epidemiol 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.WHO. Guidance on Couples HIV Testing and Counselling Including Antiretroviral Therapy for Treatment and Prevention in Serodiscordant Couples: Recommendations for a Public Health Approach. In. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO Press; 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). PEPFAR Monitoring, Evaluation, and Reporting Indicator Reference Guide version 2.1. In; 2015.

- 22.The Global Fund. HIV Information Note. In. Geneva, Switzerland; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zambian Ministry of Health. Zambia National Guidelines for HIV Counselling and Testing. In. Lusaka, Zambia; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wall KM, Kilembe W, Vwalika B, Haddad LB, Lakhi S, Onwubiko U, et al. Sustained effect of couples’ HIV counselling and testing on risk reduction among Zambian HIV serodiscordant couples. Sex Transm Infect 2017; 93(4):259–266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Allen S, Meinzen-Derr J, Kautzman M, Zulu I, Trask S, Fideli U, et al. Sexual behavior of HIV discordant couples after HIV counseling and testing. AIDS (London, England) 2003; 17(5):733–740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kelley AL, Hagaman AK, Wall KM, Karita E, Kilembe W, Bayingana R, et al. Promotion of couples’ voluntary HIV counseling and testing: a comparison of influence networks in Rwanda and Zambia. BMC public health 2016; 16:744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Khu NH, Vwalika B, Karita E, Kilembe W, Bayingana RA, Sitrin D, et al. Fertility goal-based counseling increases contraceptive implant and IUD use in HIV-discordant couples in Rwanda and Zambia. Contraception 2013; 88(1):74–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Global Health Cost Consortium. Analyzing and presenting results: Principles 15–17. In; 2020.

- 29.Walker D, Kumaranayake L. Allowing for differential timing in cost analyses: discounting and annualization. Health Policy Plan 2002; 17(1):112–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Husereau D, Drummond M, Petrou S, Carswell C, Moher D, Greenberg D, et al. Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards (CHEERS) statement. International journal of technology assessment in health care 2013; 29(2):117–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.USAID. Couple Years of Protection (CYP). In; 2014.

- 32.Sedgh G, Singh S, Hussain R. Intended and Unintended Pregnancies Worldwide in 2012 and Recent Trends. Studies in family planning 2014; 45(3):301–314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, University of Zambia. Health Service Provision in Zambia: Assessing Facility Capacity, Costs of Care, and Patient Perspectives. In. Seattle, WA: Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Koontz SL, Molina de Perez O, Leon K, Foster-Rosales A. Treating incomplete abortion in El Salvador: cost savings with manual vacuum aspiration. Contraception 2003; 68(5):345–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rydzak CE, Goldie SJ. Cost-effectiveness of rapid point-of-care prenatal syphilis screening in sub-Saharan Africa. Sexually transmitted diseases 2008; 35(9):775–784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Parmar D, Leone T, Coast E, Murray SF, Hukin E, Vwalika B. Cost of abortions in Zambia: A comparison of safe abortion and post abortion care. Global Public Health 2017; 12(2):236–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hitimana R, Lindholm L, Krantz G, Nzayirambaho M, Pulkki-Brännström A-M. Cost of antenatal care for the health sector and for households in Rwanda. BMC Health Services Research 2018; 18:262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bautista-Arredondo S, Sosa-Rubi SG, Opuni M, Contreras-Loya D, Kwan A, Chaumont C, et al. Costs along the service cascades for HIV testing and counselling and prevention of mother-to-child transmission. AIDS (London, England) 2016; 30(16):2495–2504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Neukom J, Chilambwe J, Mkandawire J, Mbewe RK, Hubacher D. Dedicated providers of long-acting reversible contraception: new approach in Zambia. Contraception 2011; 83(5):447–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Haberlen SA, Narasimhan M, Beres LK, Kennedy CE. Integration of Family Planning Services into HIV Care and Treatment Services: A Systematic Review. Stud Fam Plann 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dunkle KL, Greenberg L, Lanterman A, Stephenson R, Allen S. Source of new infections in generalised HIV epidemics – Authors’ reply. Lancet (London, England) 2008; 372(9646):1300–1301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Galarraga O, Colchero MA, Wamai RG, Bertozzi SM. HIV prevention cost-effectiveness: a systematic review. BMC public health 2009; 9 Suppl 1:S5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.John FN, Farquhar C, Kiarie JN, Kabura MN, John-Stewart GC. Cost effectiveness of couple counselling to enhance infant HIV-1 prevention. Int J STD AIDS 2008; 19(6):406–409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sarkar S, Corso P, Ebrahim-Zadeh S, Kim P, Charania S, Wall K. Cost-effectiveness of HIV Prevention Interventions in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Systematic Review. EClinicalMedicine 2019; 10:10–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Babigumira JB, Stergachis A, Veenstra DL, Gardner JS, Ngonzi J, Mukasa-Kivunike P, et al. Potential Cost-Effectiveness of Universal Access to Modern Contraceptives in Uganda. PLoS One 2012; 7(2):e30735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lépine A, Nundy N, Kilbourne-Brook M, Siapka M, Terris-Prestholt F. Cost-Effectiveness of Introducing the SILCS Diaphragm in South Africa. PLoS One 2015; 10(8):e0134510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Di Giorgio L, Mvundura M, Tumusiime J, Morozoff C, Cover J, Drake JK. Is contraceptive self-injection cost-effective compared to contraceptive injections from facility-based health workers? Evidence from Uganda. Contraception 2018; 98(5):396–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shade SB, Kevany S, Onono M, Ochieng G, Steinfeld RL, Grossman D, et al. Cost, cost-efficiency and cost-effectiveness of integrated family planning and HIV services. AIDS (London, England) 2013; 27 Suppl 1:S87–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Babigumira JB, Vlassoff M, Ahimbisibwe A, Stergachis A. Surgery for Family Planning, Abortion, and Postabortion Care. In: Essential Surgery: Disease Control Priorities, Third Edition. Debas HT, Donkor P, Gawande A, Jamison DT, Kruk ME, Mock CN (editors). Washington DS: The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank; 2015. p. Table 7.3: Annual Cost per CYP of Contraceptive Methods in Selected African Countries. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tumlinson K, Steiner MJ, Rademacher KH, Olawo A, Solomon M, Bratt J. The promise of affordable implants: is cost recovery possible in Kenya? Contraception 2011; 83(1):88–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Management Sciences for Health. International Medical Products Price Guide. In; 2016.

- 52.Ngo TD, Nuccio O, Pereira SK, Footman K, Reiss K. Evaluating a LARC Expansion Program in 14 Sub-Saharan African Countries: A Service Delivery Model for Meeting FP2020 Goals. Maternal and child health journal 2017; 21(9):1734–1743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bellows B, Mackay A, Dingle A, Tuyiragize R, Nnyombi W, Dasgupta A. Increasing Contraceptive Access for Hard-to-Reach Populations With Vouchers and Social Franchising in Uganda. Global Health: Science and Practice 2017; 5(3):446–455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rattan J, Noznesky E, Curry DW, Galavotti C, Hwang S, Rodriguez M. Rapid Contraceptive Uptake and Changing Method Mix With High Use of Long-Acting Reversible Contraceptives in Crisis-Affected Populations in Chad and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Global Health: Science and Practice 2016; 4(Suppl 2):S5–S20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tibaijuka L, Odongo R, Welikhe E, Mukisa W, Kugonza L, Busingye I, et al. Factors influencing use of long-acting versus short-acting contraceptive methods among reproductive-age women in a resource-limited setting. BMC women’s health 2017; 17:25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ayad M, Hong R. Further Analysis of the Rwanda Demographic and Health Surveys, 2000–2007/08: Levels and Trends of Contraceptive Prevalence and Estimate of Unmet Need for Family Planning in Rwanda. In: DHS Further Analysis Reports No 67 Calverton, Maryland, USA: ICF Macro.; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 57.United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Trends in Contraceptive Use Worldwide 2015. 2015; ST/ESA/SER.A/349.

- 58.Rwanda FP2020 Core Indicator Summary Sheet: 2017. In; 2017.

- 59.National Institute of Statistics of Rwanda (NISR) [Rwanda] MoHM,], and ICF International. 2014–15 Rwanda Demographic Health Survey Key Findings. 2015.

- 60.FHI 360. Integrating Family Planning into HIV Programs: Evidence-Based Practices. In; 2013.

- 61.Malama K, Kilembe W, Inambao M, Hoagland A, Sharkey T, Parker R, et al. A couple-focused, integrated unplanned pregnancy and HIV prevention program in urban and rural Zambia. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]