Abstract

The clinicopathological features of myeloid-derived suppressor cell (MDSC) and CD8+ T-cell infiltration in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) are poorly understood. The present study examined MDSC and CD8+ T-cell infiltration in surgically resected primary HCC specimens and investigated the association of MDSC and CD8+ T-cell infiltration with clinicopathological features and patient outcomes. Using a database of 466 patients who underwent hepatic resection for HCC, immunohistochemical staining of CD33 (an MDSC marker) and CD8 was performed. High infiltration of MDSCs within the tumor was observed in patients with a poorer Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer stage, larger tumor size, more poorly differentiated HCC, and greater presence of portal venous thrombosis, microscopic vascular thrombosis and macroscopic intrahepatic metastasis. MDSC infiltration and CD8+ T-cell infiltration were independent predictors of recurrence-free survival and overall survival, respectively. Stratification based on the MDSC and CD8+ T-cell status of the tumors was also associated with recurrence-free survival (10 year-recurrence-free survival; MDSChighCD8+ T-cellLow, 3.68%; others, 25.7%) and overall survival (10 year-overall survival; MDSChighCD8+ T-cellLow, 12.0%; others, 56.7%). In conclusion, the present large cohort study revealed that high MDSC infiltration was associated with a poor clinical outcome in patients with HCC. Furthermore, the combination of the MDSC and tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T-cell status enabled further classification of patients based on their outcomes.

Keywords: tumor infiltrating lymphocyte, CD8+ T cell, tumor microenvironment, immune checkpoint inhibitor, T cell exhaustion

Introduction

Primary liver cancer is the fourth most common cancer worldwide. HCC occurs due to liver cirrhosis, hepatitis B/C virus infection, and alcoholic or nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Although liver resection has been performed as an effective and safe treatment in patients with HCC, the possibility of recurrence remains high (1,2). The use of combination immune checkpoint inhibitors for unresectable HCC was recently approved.

Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes are a major component of the host anti-tumor immune response. Cluster of differentiation (CD)3+, CD8+, CD4+, and FoxP3+ T lymphocytes are the representative subsets of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes. With the growing interest in tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes, an increase in the number of activated cytotoxic T lymphocytes has been reported to correlate with better survival in some malignant tumors, including HCC (3–5). CD8+ T-cell infiltration in tumors plays an important role in host immunity against tumor progression. Phase III clinical trials for various immune checkpoint inhibitors and multikinase inhibitors have been conducted since the approval of sorafenib for hepatocellular carcinoma in 2009, all of them failed for 10 years until the emergence of Lenvatinib. The tumor microenvironment in HCC is complex, due to crosstalk with tumor components, such as cancer cells, stromal cells, and immune cells. Phenotypic changes in cancer cell by genetic and epigenetic alternations affect anti-cancer immunity and cancer-stromal cell interaction, through the expression of immune checkpoint molecule, cytokines, and growth factors, which may affect immune system in the tumor (6).

Although dysregulation of the immune system and uncontrolled inflammatory responses may also contribute to disease pathology, immune responses are necessary for clearance of malignant cells, pathogens, and virus-infected cells (7). Myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), which are immature cells, reportedly play important roles in tumor immune invasion and have a remarkable ability to suppress T-cell responses (8). Major factors in MDSCs-mediated immune suppression include expression of arginase, inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), transforming growth factor-β, interleukin-10, and cyclooxygenase 2 (9). In particular, the suppressive activity has been reported to be associated with the metabolism of L-arginine. L-arginine is a substrate for two enzymes: iNOS, which generates nitric oxide (NO) and arginase, which converts L-arginine into urea and L-ornithine (8). Both of these enzymes has an ability of direct inhabitation for T cell function (10,11). In addition, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) is secreted form tumors and causes MDSCs to accumulate into tumors. VEGF is produced from MDSCs themselves and is involved in promoting growth of tumor and MDSCs themselves (12). The attention for therapeutic strategies for MDSC is increasing. All-trans retinoic acid induces the differentiation of MDSCs into functional macrophages and dendric cells (13,14). Induction of differentiation into functional macrophage and dendric cells, as antigen-presenting cells, stimulates effector T cells and enhance the anti-tumor immune response. In the phase IB study, the treatment with 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 decrease the ratio of CD34-positive MDSCs in patients with head and neck cancer (15).

In this study, we investigated the tumor-infiltrating MDSC and CD8+ T-cell status by immunohistochemistry and evaluated the prognostic impact of tumor-infiltrating MDSCs and CD8+ T cells in patients with HCC. Additionally, we clustered the patients with HCC showing MDSCs and CD8+ T cells and investigated the prognostic impact of the clustering.

Patients and methods

Patients

In total, 466 patients with HCC who underwent initial liver resection at the Department of Surgery and Science, Kyushu University Hospital from January 2004 to November 2018 were enrolled in this study. The details of our surgical techniques and patient selection criteria for liver resection in HCC have been previously reported (16). The patients were followed up as outpatients every 1 to 3 months after discharge. Dynamic computed tomography was performed if recurrence was suspected. Clinical information and follow-up data were obtained from the medical records. No patients underwent immune checkpoint inhibitor treatment for recurrence. Informed consents were obtained. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Kyushu University (approval code 2020-180). An opt-out approach was employed to obtain informed consent from our patients and personal information was protected during data collection.

Immunohistochemical staining

Immunohistochemical staining for CD8 was performed as previously reported (4). The samples were fixed with 3.7% formaldehyde solution (Sigma-Aldrich) in room temperature for 24-48 h. Immunohistochemical examinations were performed on 4-µm formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded sections. The sections were first deparaffinized. After inhibition of endogenous peroxidase activity for 30 min with 3% hydrogen peroxidase in methanol, in room temperature, the sections were pretreated with Target Retrieval Solution (Dako) in a microwave oven at 99°C for 20 or 10 min for CD33 or CD8, respectively, and then incubated with monoclonal antibodies at 4°C overnight. Immune complexes were detected with an EnVision Detection System (Dako), anti-mouse secondary antibody, for 60 min, in room temperature. The sections were finally incubated in 3,3′-diaminobenzidine, for 7 min (CD33) and 4 min (CD8), in room temperature, counterstained with hematoxylin, and mounted. The primary antibodies used were a CD33 mouse antibody (PA0555, no dilution; Leica Biosystems) and a CD8 mouse antibody (ab75129, 1:50; Abcam). Stained slides were scanned using the NanoZoomer digital slide scanner (Hamamatsu Photonics K.K.). Immunohistochemical data for CD33 and CD8 staining were evaluated by three experienced researchers (T.T., S.I. and K.Y.), who were blinded to the clinical status of the patients. The final assessments were achieved by consensus. The cells exhibited plasma membranous staining for CD33.

The number of cells with cytoplasm or membrane staining in three high-power fields was counted, and we used the receiver operative characteristic analysis for overall survival (OS) as the cutoff value of CD33+ infiltrating cells in tumors. The cutoff value for CD8+ infiltrating cells in tumors was previously reported (4). CD33+ cells in tumors were defined as MDSCs in accordance with previous reports (17).

Statistical analysis

Standard statistical analyses were used to evaluate descriptive statistics, such as medians, frequencies, and percentages. Continuous variables without a normal distribution and variables were compared with the Mann-Whitney U test. A logistic regression analysis was performed to identify variables associated with MDSC infiltration. Categorical variables were compared using the χ2 test or Fisher's exact test. Survival data were used to establish a univariate Cox proportional hazards model. Covariates that were significant at P<0.05 were included in the multivariate Cox proportional hazards model. The cumulative OS and recurrence-free survival (RFS) rates were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method, and differences between the curves were evaluated using the log-rank test. Differences were considered statistically significant at P<0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using JMP15 software (SAS Institute Inc.).

Results

MDSCs, CD8+ T cells and clinicopathological factors

In our cohort of 466 patients with HCC, 344 (73.8%) patients were male. The median age of the patients was 69 years (25–75% quantile, 63-76 years). Among all 466 patients, 73 (15.7%) and 239 (51.3%) showed positive hepatitis B surface antigen and hepatitis C virus antibody expression, respectively. The median observation period was 3.69 years (25–75% quantile, 1.99-6.62 years).

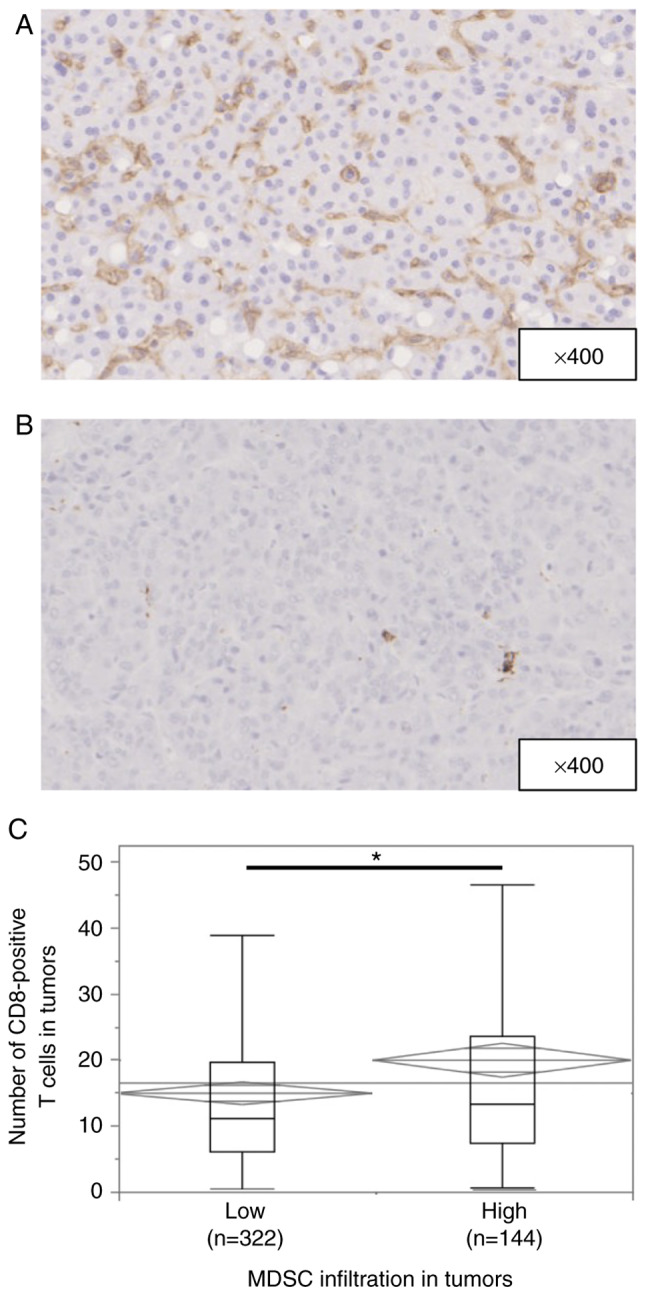

Fig. 1A and B shows representative immunohistochemical staining of CD33 in HCC tissues. CD33 expression was observed in the cytoplasm or plasma membrane of mononuclear cells. The median number of invading CD33+ cells was 73.6 per field (25–75% quantile, 39.6-121 per field). According to the cut-off value of 108, 144 (30.9%) of 466 patients had high infiltration of MDSCs. The association between MDSC infiltration and the patients' clinicopathological characteristics is shown in Table I. High MDSC infiltration was observed in patients with larger tumors (P=0.0216), a poorer Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) stage (P=0.0002), more poorly differentiated HCC (P<0.0001), and a greater presence of microscopic vascular invasion (P=0.0003) and macroscopic intrahepatic metastasis (P=0.0087).

Figure 1.

Immunohistochemical staining of MDSCs in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. (A) Image of a high MDSC infiltration pattern. Magnification, ×400. (B) Image of a low MDSC infiltration pattern. Magnification, ×400. (C) Median numbers of intra-tumor CD8+ T cells in the high and low MDSC groups were 13.3 (range, 0.667-114) and 11.0 (range, 0.333-85.3), respectively (*P=0.0015). MDSC, myeloid-derived suppressor cell.

Table I.

Association between background characteristics of patients and intra-tumoral CD33 expression.

| Variable | CD33 low (n=322) | CD33 high (n=144) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 69 (17–87) | 70 (34–86) | 0.5311 |

| Sex (male), n (%) | 235 (73.0) | 109 (75.7) | 0.5382 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 23.0 (16.0-37.9) | 22.5 (14.2-32.6) | 0.8539 |

| HBs-Ag positive, n (%) | 47 (14.6) | 26 (18.1) | 0.3495 |

| HCV-Ab positive, n (%) | 166 (51.6) | 73 (50.7) | 0.8640 |

| Child-Pugh classification, grade B, n (%) | 11 (3.4) | 5 (3.5) | 0.9755 |

| Albumin, g/dl | 4.0 (2.1-5.1) | 3.9 (1.8-4.8) | 0.1193 |

| DCP, mAU/ml | 77 (2–250400) | 109 (9–89477) | 0.9493 |

| AFP, ng/ml | 7.4 (1–693700) | 28.1 (1–994600) | 0.1632 |

| Performing preoperative TACE or TAE, n (%) | 8 (2.5) | 6 (4.2) | 0.3256 |

| Tumor size, cm | 3.2 (0.9-30) | 3.7 (1–20) | 0.0216 |

| Multiple tumors, n (%) | 64 (19.9) | 36 (25.0) | 0.2131 |

| BCLC staging (B or C), n (%) | 45 (14.0) | 42 (29.2) | 0.0001 |

| Gross classification, single nodular type, n (%) | 208 (65.0) | 80 (55.9) | 0.0633 |

| Poorly differentiation, n (%) | 80 (24.9) | 63 (43.8) | <0.0001 |

| Microscopic vascular invasion, n (%) | 82 (25.5) | 61 (42.4) | 0.0003 |

| Microscopic intrahepatic metastasis, n (%) | 47 (14.6) | 36 (25.0) | 0.0070 |

| F3 or F4, n (%) | 141 (43.8) | 55 (38.5) | 0.2830 |

Data are presented as n (%) or median (range). BMI, body mass index; HBs-Ag, hepatitis B surface antigen; HCV-Ab, hepatitis C virus antibody; DCP, des-γ-carboxy prothrombin; AFP, α-fetoprotein; TA(C)E, transcatheter arterial (chemo)embolization; BCLC, Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer.

Fig. S1A and B shows representative immunohistochemical staining of CD8 in HCC tissues. CD8 expression was observed in the cytoplasm or plasma membrane of mononuclear cells. The median number of invading CD8+ T cells was 12.0 per field (25–75% quantile, 6.33-21.0 per field). Low CD8+ T-cell infiltration was observed in male patients and in patients with larger tumors (P=0.0045), multiple tumors (P=0.0129), a poorer BCLC stage (P=0.0363), and a greater presence of microscopic vascular invasion (P=0.0011) and microscopic intrahepatic metastasis (P<0.0001) (Table SI). The number of CD8+ T cells in tumors was greater in patients with high than low MDSC infiltration (P=0.0015) (Fig. 1C).

We also examined the association between MDSC infiltration and the tumor characteristics. Multivariate analysis showed that high MDSC infiltration in HCC was significantly associated with CD8+ T-cell infiltration (P=0.0003) in addition to poor differentiation (P=0.0068) and microscopic vascular invasion (P=0.0370) (Table II).

Table II.

Univariate and multivariate analyses of high CD33+ cell infiltration and clinicopathological factors in patients who underwent hepatic resection for hepatocellular carcinoma.

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||

| Variable | HR | 95% CI | P-value | HR | 95% CI | P-value |

| Age | 0.99 | 0.98-1.01 | 0.5317 | |||

| Sex | ||||||

| Male (n=344) | 1.15 | 0.73-1.81 | ||||

| Female (n=122) | 1.00 | (ref.) | 0.5363 | |||

| HBsAg | ||||||

| Positivity (n=73) | 1.28 | 0.76-2.17 | ||||

| Negativity (n=392) | 1.00 | (ref.) | 0.3544 | |||

| HCVAb | ||||||

| Positive (n=239) | 0.96 | 0.65-1.43 | ||||

| Negative (n=229) | 1.00 | (ref.) | 0.8640 | |||

| Alb | 0.71 | 0.46-1.09 | 0.1210 | |||

| DCP | 1.00 | 1.00-1.00 | 0.9493 | |||

| AFP | 1.00 | 1.00-1.00 | 0.1820 | |||

| Tumor size | 1.06 | 1.01-1.12 | 0.0247 | 1.00 | 0.94-1.07 | 0.9683 |

| Macroscopic tumor numbers | ||||||

| Multiple (n=100) | 1.94 | 1.48-2.55 | 0.97 | 0.95-1.87 | ||

| Single (n=366) | 1.00 | (ref.) | <0.0001 | 1.00 | (ref.) | 0.9347 |

| Poorly differentiated | ||||||

| Present (n=143) | 2.34 | 1.55-3.55 | 1.88 | 1.19-2.97 | ||

| Absent (n=322) | 1.00 | (ref.) | <0.0001 | 1.00 | (ref.) | 0.0068 |

| Tumor types | ||||||

| Boundary type (n=288) | 1.00 | (ref.) | ||||

| Nonboundary type (n=175) | 1.46 | 0.98-2.19 | 0.0646 | |||

| Microscopic vascular invasion | ||||||

| Present (n=143) | 2.15 | 1.42-3.26 | 1.67 | 1.03-2.70 | ||

| Absent (n=323) | 1.00 | (ref.) | 0.0003 | 1.00 | (ref.) | 0.0370 |

| Microscopic intrahepatic metastasis | ||||||

| Present (n=83) | 1.94 | 1.19-3.17 | 1.73 | 0.896-3.34 | ||

| Absent (n=382) | 1.00 | (ref.) | 0.0076 | 1.00 | (ref.) | 0.1022 |

| Fibrosis | ||||||

| F0-2 (n=269) | 1.00 | (ref.) | ||||

| F3, 4 (n=196) | 0.80 | 0.54-1.20 | 0.2818 | |||

| CD8-positive cell infiltration | 1.02 | 1.01-1.03 | 0.0021 | 1.02 | 1.01-1.04 | 0.0003 |

Parameters without subcategories are evaluated using continuous variables. HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; HBs-Ag, hepatitis B surface antigen; HCV-Ab, hepatitis C virus antibody; Alb, albumin; DCP, des-γ-carboxy prothrombin; AFP, α-fetoprotein; ref., reference.

Univariate and multivariate analyses of prognostic factors for RFS and OS

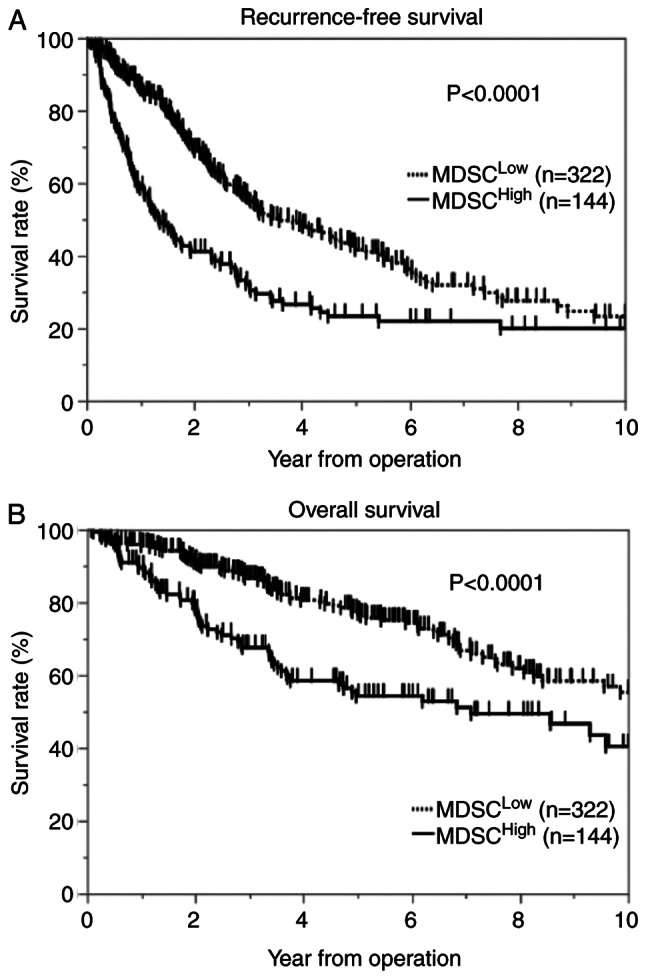

We assessed the association between MDSC infiltration and patient postoperative survival using the Kaplan-Meier method. The results showed that patients with high MDSC infiltration in tumors had significantly shorter RFS (log-rank P<0.0001) and OS (log-rank P<0.0001) after surgery than patients with low MDSC infiltration (Fig. 2A and B). Next, we assessed the association between CD8+ T-cell infiltration and patient postoperative survival using the Kaplan-Meier method. The results showed that patients with CD8+ T-cell infiltration in tumors had significantly shorter RFS (log-rank P<0.0001) and OS (log-rank P<0.0001) after surgery than patients with high infiltration (Fig. S2A and B).

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier curves showing the survival of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma according to the number of intra-tumoral MDSCs. (A) Recurrence-free survival and (B) overall survival in all patients according to high and low numbers of intra-tumoral MDSCs. MDSC, myeloid-derived suppressor cell.

Tables III and IV list the univariate and multivariate analysis results associated with RFS and OS in patients with surgically resected HCC. Cox proportional hazard regression models with multivariate analysis showed that high MDSC infiltration in tumors was associated with significantly worse RFS and OS (hazard ratio [HR], 1.98; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.51-2.60; P<0.0001 and HR, 1.82; 95% CI, 1.27-2.62; P=0.0012) and that low CD8+ T-cell infiltration in tumors was associated with significantly worse RFS and OS (HR, 2.31; 95% CI, 1.77-3.01; P<0.0001 and HR, 3.28; 95% CI, 2.20-4.48; P<0.0001). Age was the only OS factor, but CD8-positive cell infiltration, microscopic serum albumin, AFP, tumor size, and intrahepatic metastasis were independent prognostic factors for both RFS and OS.

Table III.

Results of univariate and multivariate analyses of recurrence-free survival.

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||

| Variable | HR | 95% CI | P-value | HR | 95% CI | P-value |

| Age | 1.01 | 0.97-1.02 | 0.2481 | |||

| Sex | ||||||

| Male (n=344) | 1.28 | 0.96-1.71 | ||||

| Female (n=122) | 1.00 | (ref.) | 0.0870 | |||

| HBsAg | ||||||

| Positivity (n=73) | 0.83 | 0.59-1.16 | ||||

| Negativity (n=392) | 1.00 | (ref.) | 0.2709 | |||

| HCVAb | ||||||

| Positive (n=239) | 0.98 | 0.77-1.25 | ||||

| Negative (n=229) | 1.00 | (ref.) | 0.8607 | |||

| Alb | 0.55 | 0.42-0.72 | <0.0001 | 0.59 | 0.45-0.78 | 0.0001 |

| DCP | 1.00 | 1.00-1.00 | 0.0001 | 1.00 | 0.99-1.00 | 0.6709 |

| AFP | 1.00 | 1.00-1.00 | <0.0001 | 1.00 | 1.00-1.00 | <0.0001 |

| Tumor size | 1.09 | 1.06-1.12 | <0.0001 | 1.05 | 1.01-1.09 | 0.0133 |

| Macroscopic tumor numbers | ||||||

| Multiple (n=100) | 1.94 | 1.48-2.55 | 1.33 | 0.952-1.87 | ||

| Solitary (n=366) | 1.00 | (ref.) | <0.0001 | 1.00 | (ref.) | 0.0941 |

| Poorly differentiated | ||||||

| Present (n=143) | 1.81 | 1.41-2.33 | 1.23 | 0.925-1.65 | ||

| Absent (n=322) | 1.00 | (ref.) | <0.0001 | 1.00 | (ref.) | 0.1524 |

| Tumor types | ||||||

| Boundary type (n=288) | 1.00 | (ref.) | 1.00 | (ref.) | ||

| Nonboundary type (n=175) | 1.50 | 1.17-1.90 | 0.0012 | 1.02 | 0.78-1.33 | 0.9106 |

| Microscopic vascular invasion | ||||||

| Present (n=143) | 1.90 | 1.48-2.44 | 1.19 | 0.89-1.60 | ||

| Absent (n=323) | 1.00 | (ref.) | <0.0001 | 1.00 | (ref.) | 0.2480 |

| Microscopic intrahepatic metastasis | ||||||

| Present (n=83) | 3.11 | 2.33-4.17 | 1.72 | 1.17-2.55 | ||

| Absent (n=382) | 1.00 | (ref.) | <0.0001 | 1.00 | (ref.) | 0.0060 |

| Fibrosis | ||||||

| F0-2 (n=269) | 1.00 | (ref.) | ||||

| F3, 4 (n=196) | 1.11 | 0.87-1.41 | 0.4139 | |||

| CD33-positive cell infiltration | ||||||

| High (n=144) | 1.87 | 1.46-2.40 | 1.98 | 1.51-2.60 | ||

| Low (n=322) | 1.00 | (ref.) | <0.0001 | 1.00 | (ref.) | <0.0001 |

| CD8-positive cell infiltration | ||||||

| High (n=219) | 1.00 | (ref.) | 1.00 | (ref.) | ||

| Low (n=247) | 2.00 | 1.56-2.56 | <0.0001 | 2.31 | 1.77-3.01 | <0.0001 |

Parameters without subcategories are evaluated using continuous variables. HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; HBs-Ag, hepatitis B surface antigen; HCV-Ab, hepatitis C virus antibody; Alb, albumin; DCP, des-γ-carboxy prothrombin; AFP, α-fetoprotein; ref., reference.

Table IV.

Results of univariate and multivariate analyses of overall survival.

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||

| Variable | HR | 95% CI | P-value | HR | 95% CI | P-value |

| Age | 1.02 | 1.00-1.04 | 0.0160 | 1.02 | 1.00-1.04 | 0.0161 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male (n=344) | 0.99 | 0.69-1.44 | ||||

| Female (n=122) | 1.00 | (ref.) | 0.9763 | |||

| HBsAg | ||||||

| Positivity (n=73) | 0.94 | 0.60-1.45 | ||||

| Negativity (n=392) | 1.00 | (ref.) | 0.7657 | |||

| HCVAb | ||||||

| Positive (n=239) | 1.13 | 0.81-1.57 | ||||

| Negative (n=229) | 1.00 | (ref.) | 0.4783 | |||

| Alb | 0.36 | 0.27-0.51 | <0.0001 | 0.40 | 0.28-0.59 | <0.0001 |

| DCP | 1.00 | 1.00-1.00 | 0.0001 | 1.00 | 0.999-1.00 | 0.9713 |

| AFP | 1.00 | 1.00-1.00 | <0.0001 | 1.00 | 1.00-1.00 | 0.0257 |

| Tumor size | 1.11 | 1.07-1.15 | <0.0001 | 1.04 | 0.98-1.09 | 0.1847 |

| Macroscopic tumor numbers | ||||||

| Multiple (n=100) | 1.74 | 1.22-2.50 | 0.76 | 0.47-1.23 | ||

| Solitary (n=366) | 1.00 | (ref.) | 0.0025 | 1.00 | (ref.) | 0.2656 |

| Poorly differentiated | ||||||

| Present (n=143) | 2.20 | 1.58-3.06 | 1.45 | 0.98-2.15 | ||

| Absent (n=322) | 1.00 | (ref.) | <0.0001 | 1.00 | (ref.) | 0.0606 |

| Tumor types | ||||||

| Boundary type (n=288) | 1.00 | (ref.) | 1.00 | (ref.) | ||

| Nonboundary type (n=175) | 1.48 | 1.07-2.05 | 0.0193 | 0.83 | 0.57-1.20 | 0.3182 |

| Microscopic vascular invasion | ||||||

| Present (n=143) | 2.89 | 1.65-3.18 | 1.27 | 0.86-1.87 | ||

| Absent (n=323) | 1.00 | (ref.) | <0.0001 | 1.00 | (ref.) | 0.2360 |

| Microscopic intrahepatic metastasis | ||||||

| Present (n=83) | 3.32 | 2.32-4.74 | 2.07 | 1.23-3.49 | ||

| Absent (n=382) | 1.00 | (ref.) | <0.0001 | 1.00 | (ref.) | 0.0063 |

| Fibrosis | ||||||

| F0-2 (n=269) | 1.00 | (ref.) | ||||

| F3, 4 (n=196) | 1.14 | 0.82-1.59 | 0.4250 | |||

| CD33-positive cell infiltration | ||||||

| High (n=144) | 1.94 | 1.40-2.70 | 1.82 | 1.27-2.62 | ||

| Low (n=322) | 1.00 | (ref.) | <0.0001 | 1.00 | (ref.) | 0.0012 |

| CD8-positive cell infiltration | ||||||

| High (n=219) | 1.00 | (ref.) | 1.00 | (ref.) | ||

| Low (n=247) | 3.37 | 2.33-4.09 | <0.0001 | 3.28 | 2.20-4.88 | <0.0001 |

Parameters without subcategories are evaluated using continuous variables. HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; HBs-Ag, hepatitis B surface antigen; HCV-Ab, hepatitis C virus antibody; Alb, albumin; DCP, des-γ-carboxy prothrombin; AFP, α-fetoprotein; ref., reference.

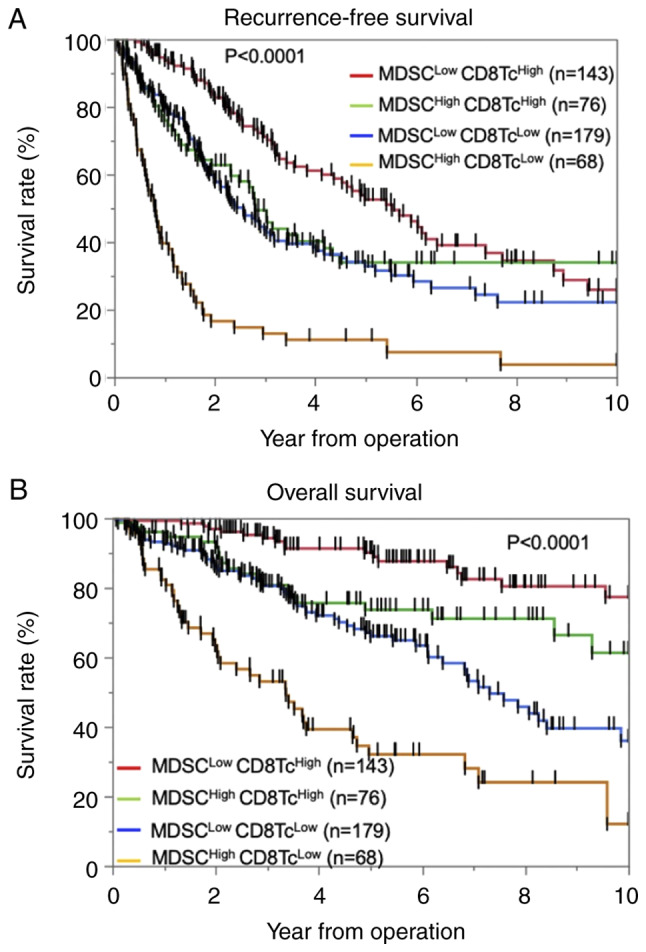

Stratification of MDSC and CD8+ T-cell infiltration in HCC

Next, we evaluated the significance of MDSC and CD8+ T-cell infiltration in predicting OS and RFS. The patients were divided into the following four groups: MDSC-Low/CD8-High (n=143), MDSC-High/CD8-High (n=76), MDSC-Low/CD8-Low (n=179), and MDSC-High/CD8-Low (n=68). We found that both RFS (log-rank P<0.0001) and OS (log-rank P<0.0001) were significantly different among the four groups [RFS: MDSC-Low/CD8-High; 25.9%, MDSC-High/CD8-High; 33.9%, MDSC-Low/CD8-Low; 22.2%, MDSC-High/CD8-Low 3.68%, OS; MDSC-Low/CD8-High 77.3%, MDSC-High/CD8-High 61.3%, MDSC-Low/CD8-Low 36.0%, MDSC-High/CD8-Low 12.0%] (Fig. 3A and B). Among the patients with high MDSC infiltration, those with low CD8+ T-cell infiltration had significantly poorer RFS (log-rank P<0.0001) and OS (log-rank P<0.0001) compared with patients with high CD8+ T-cell infiltration. Similarly, among the patients with low MDSC infiltration, those with low CD8+ T-cell infiltration had significantly poorer RFS (log-rank P<0.0001) and OS (log-rank P<0.0001) compared with patients with high CD8+ T-cell infiltration. The differences in the clinicopathological characteristics between patients with high MDSC infiltration and low CD8+ T-cell infiltration are shown in Table SII. High MDSC infiltration and low CD8+ T-cell infiltration were observed in patients with larger tumors (P=0.0001), high serum AFP leve (P=0.0070), low rate of single nodular type (P=0.0181), a poorer BCLC stage (P=0.0004), more poorly differentiated HCC (P<0.0001), and greater presence of microscopic vascular invasion (P<0.0001) and macroscopic intrahepatic metastasis (P<0.0001).

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier curves for patients classified according to the numbers of intra-tumoral MDSCs and CD8+ T cells. Kaplan-Meier curves for (A) recurrence-free survival and (B) overall survival in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma according to the numbers of intra-tumoral MDSCs and CD8+ T cells. CD8Tc, CD8+ T-cell; MDSC, myeloid-derived suppressor cell.

Discussion

In the present study, we analyzed the CD33+ cells in patients with HCC who had undergone hepatic resection. We demonstrated that high numbers of tumor-infiltrating CD33+ cells and CD8+ cells were correlated with a poor prognosis, and we were able to stratify the prognosis based on the number of tumor-infiltrating CD33+ cells and CD8+ cells.

MDSCs are the major immunosuppressive population existing only in pathological conditions such as malignancy and chronic inflammation (18). Malignant cells regulate distant sites, such as the bone marrow and spleen, by secreting soluble factors that cause the accumulation of myeloid cells; these myeloid cells subsequently promote tumor metastasis and neovascularization (18). Patients with HCC exhibiting high numbers of MDSCs reportedly have more vascular invasion than patients with low numbers of MDSCs (19). In the present study, patients with high numbers of MDSCs had a significantly higher frequency of microscopic intrahepatic metastasis and vascular invasion as well as shorter RFS.

Human MDSCs are phenotypically characterized as CD11b+ or CD33+ (8,20,21), and the CD33 myeloid marker can be used instead of CD11b because the number of CD15+ cells is very low (20). Hence, in this study, we used only CD33 as an MDSC marker, and the effects of CD33+ cells other than MDSCs was considered to be very small. Although some small studies have focused on MDSCs and the prognosis of HCC, we examined a large number of patients (nearly 500).

Cytotoxic CD8+ T cells play a pivotal role in anti-tumor immunity. However, in the context of a suppressive tumor microenvironment and prolonged antigen exposure, tumor-specific effector CD8+ T cells tend to differentiate into a condition called T-cell exhaustion (22). Such exhausted CD8+ T cells are distinguished from functional and memory T cells by their hierarchical loss of cytokine production ability and killing capacity (23). Hepatocellular CCRK/EZH2/NH-kB/IL-6 signaling deteriorates anti-tumor T-cell responses by induction of MDSC immunosuppression, and HCC with high mRNA CD11b/CD33/CCRK expression is significantly correlated with shorter OS and disease-free survival rates (24). In the present study, the MDSC-High/CD8-Low group had the poorest RFS and OS, although there were more CD8+ T cells in the tumors in the high than low MDSC group. In our study, MDSC high group had significantly poor OS and RFS than MDSC low ones, in CD8+ high group. MDSC has been reported to decrease mTOR activity in CD8 positive cells, inhibit T cell differentiation into effector cells, and reduce the efficacy of immunotherapy (25). Clinical trial in head and neck cancer have shown that the PI3Kδ/γ, a selective inhibitor of MDSCs, can enhance the effect of anti-PD-L1 (26). Hence, the stratification of the patient with HCC by MDSC and CD8+ T cells may predict the therapeutic effect of immune checkpoint inhibitor, and addition of anti-MDSCs drugs may bring therapeutic effects to the group that has not response to immune checkpoint inhibitors. Our analysis shows that the number of MDSC infiltration is a prognostic factor independent of CD8+ T cells, and further investigation is needed.

After encountering tumor antigen, T cells acquire effector function and traffic to the tumor site to mount an attack on the tumor (17). Infiltration of T cells into the tumor microenvironment is the pivotal obstacle for T cells to initiate an effective anti-tumor response. However, once T cells have infiltrated the tumor, their success in killing the tumor is determined by their ability to overcome additional obstacles and counter-defense mechanisms that they encounter from the tumor cells, MDSCs, regulatory T cells, stromal cells, inhibitory cytokines, and other cells in the complex tumor microenvironment, which act to deteriorate the anti-tumor immune response (27). Immunotherapy focusing on immune checkpoint inhibitors has been approved for the treatment of various cancers (27–30). Immune checkpoint blockage using anti-programmed death-1 (PD-1)/programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) antibodies in HCC has recently shown favorable results (31,32). Although a strong prognostic effect of PD-1/PD-L1 expression in HCC has been reported (4,22,33–36), the response rate appears to be much lower than that of immunogenic tumors such as Hodgkin's lymphoma and melanoma, which are characterized by higher tumorous PD-L1 expression and intratumor CD8+ cells and a less immunosuppressive microenvironment in most responding patients (24,27,28). These clinical observations emphasize the importance of the compelling need to reverse the non-immunogenic liver tumor microenvironment for more effective therapeutic responses to immune checkpoint therapy (24). Although effective treatment for the non-immunogenic microenvironment in HCC, such as MDSCs, has not been established, atezolizumab + bevacizumab may be useful. A recent large phase III study called IMbrave150 compared atezolizumab + bevacizumab with sorafenib as the first treatment for patients with unresectable HCC. The study demonstrated statistically significant and clinically dramatic improvements in both OS and RFS for atezolizumab + bevacizumab compared with sorafenib. Bevacizumab, an anti-vascular endothelial growth factor antibody, has the capability of promoting vascular normalization, increasing the infiltration of lymphocytes into tumor tissues, and decreasing the amount and function of MDSCs, tumor-associated macrophages, and regulatory T cells, thus leading to synergistic efficacy after combination with PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors (37). In addition, a variety of therapeutic agents in other cancers have been reported for MDSCs. In model mouse, administration of docetaxel decrease MDSCs and increase the expression of macrophage differentiation markers (38). Fluorouracil also selectively damaged MDSCs, which led to an increase response of tumor specific CD8+ T cell (39).

In conclusion, high infiltration of MDSCs in HCC was found to be an independent prognostic factor for OS and RFS, and patients with high infiltration of MDSCs and low infiltration of T cells in HCC showed a worse prognosis than other patients. Therefore, MDSC and T-cell infiltration in HCC may be a clinical biomarker for selection of patients for anti-PD-1/PD-L1 and anti-vascular endothelial growth factor therapy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr Angela Morben for editing a draft of this manuscript.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- BCLC

Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer

- CI

confidence interval

- HR

hazard ratio

- iNOS

inducible nitric oxide synthase

- MDSC

myeloid-derived suppressor cells

- NO

nitric oxide

- OS

overall survival

- PD-1

programmed death 1

- PD-L1

programmed death ligand 1

- RFS

recurrence-free survival

Funding Statement

The present study was supported by the following grant: Japan Society for the Promotion of Science KAKENHI (no. JP-19K09198).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors' contributions

TTomiy, SI and TY conceived and designed the study. TTomiy, SI, KY, KK, NI, AM, KM, MM and YO developed the methodology. TTomiy, SI, NI, AM, KT, YKF, TTomin, TK, YN, KM and NH acquired data. TTomiy, SI, KT, KY, KK and YO analyzed and interpreted data. TTomiy, SI, MM and TY wrote, reviewed and/or revised the manuscript. MM, YO and TY supervised the study. TTomiy, SI and NI confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The present project received ethical approval from Kyushu University Hospital (approval no. 2020-180; Fukuoka, Japan). An opt-out approach was employed to obtain informed consent from our patients and personal information was protected during data collection.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Itoh S, Morita K, Ueda S, Sugimachi K, Yamashita Y, Gion T, Fukuzawa K, Wakasugi K, Taketomi A, Maehara Y. Long-term results of hepatic resection combined with intraoperative local ablation therapy for patients with multinodular hepatocellular carcinomas. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16:3299–3307. doi: 10.1245/s10434-009-0721-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Itoh S, Shirabe K, Taketomi A, Morita K, Harimoto N, Tsujita E, Sugimachi K, Yamashita Y, Gion T, Maehara Y. Zero mortality in more than 300 hepatic resections: Validity of preoperative volumetric analysis. Surg Today. 2012;42:435–440. doi: 10.1007/s00595-011-0108-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yagi T, Baba Y, Ishimoto T, Iwatsuki M, Miyamoto Y, Yoshida N, Watanabe M, Baba H. PD-L1 expression, tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes, and clinical outcome in patients with surgically resected esophageal cancer. Ann Surg. 2019;269:471–478. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Itoh S, Yoshizumi T, Yugawa K, Imai D, Yoshiya S, Takeishi K, Toshima T, Harada N, Ikegami T, Soejima Y, et al. Impact of immune response on outcomes in hepatocellular carcinoma: association with vascular formation. Hepatology. 2020;72:1987–1999. doi: 10.1002/hep.31206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Unitt E, Marshall A, Gelson W, Rushbrook SM, Davies S, Vowler SL, Morris LS, Coleman N, Alexander GJ. Tumour lymphocytic infiltrate and recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma following liver transplantation. J Hepatol. 2006;45:246–253. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2005.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nishida N. Role of oncogenic pathways on the cancer immunosuppressive microenvironment and its clinical implications in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancers (Basel) 2021;13:3666. doi: 10.3390/cancers13153666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Feehan KT, Gilroy DW. Is resolution the end of inflammation? Trends Mol Med. 2019;25:198–214. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2019.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gabrilovich DI, Nagaraj S. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells as regulators of the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:162–174. doi: 10.1038/nri2506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marvel D, Gabrilovich DI. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells in the tumor microenvironment: Expect the unexpected. J Clin Invest. 2015;125:3356–3364. doi: 10.1172/JCI80005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rodríguez PC, Ochoa AC. Arginine regulation by myeloid derived suppressor cells and tolerance in cancer: Mechanisms and therapeutic perspectives. Immunol Rev. 2008;222:180–191. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00608.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bronte V, Zanovello P. Regulation of immune responses by L-arginine metabolism. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:641–654. doi: 10.1038/nri1668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tartour E, Pere H, Maillere B, Terme M, Merillon N, Taieb J, Sandoval F, Quintin-Colonna F, Lacerda K, Karadimou A, et al. Angiogenesis and immunity: A bidirectional link potentially relevant for the monitoring of antiangiogenic therapy and the development of novel therapeutic combination with immunotherapy. Cancer Metast Rev. 2011;30:83–95. doi: 10.1007/s10555-011-9281-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nefedova Y, Fishman M, Sherman S, Wang X, Beg AA, Gabrilovich DI. Mechanism of all-trans retinoic acid effect on tumor-associated myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Cancer Res. 2007;67:11021–11028. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Almand B, Clark JI, Nikitina E, van Beynen J, English NR, Knight SC, Carbone DP, Gabrilovich DI. Increased production of immature myeloid cells in cancer patients: A mechanism of immunosuppression in cancer. J Immunol. 2001;166:678–689. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.1.678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lathers DMR, Clark JI, Achille NJ, Young MRI. Phase 1B study to improve immune responses in head and neck cancer patients using escalating doses of 25-hydroxyvitamin D3. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2004;53:422–430. doi: 10.1007/s00262-003-0459-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Itoh S, Shirabe K, Matsumoto Y, Yoshiya S, Muto J, Harimoto N, Yamashita Y, Ikegami T, Yoshizumi T, Nishie A, Maehara Y. Effect of body composition on outcomes after hepatic resection for hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21:3063–3068. doi: 10.1245/s10434-014-3686-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ni H, Zhang L, Huang H, Dai S, Li J. Connecting METTL3 and intratumoural CD33+ MDSCs in predicting clinical outcome in cervical cancer. J Transl Med. 2020;18:393. doi: 10.1186/s12967-020-02553-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gabrilovich DI, Ostrand-Rosenberg S, Bronte V. Coordinated regulation of myeloid cells by tumours. Nat Rev Immunol. 2012;12:253–268. doi: 10.1038/nri3175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gao X, Tian L, Wu J, Ma XL, Zhang CY, Zhou Y, Sun YF, Hu B, Qiu SJ, Zhou J, et al. Circulating CD14+ HLA-DR−/low myeloid-derived suppressor cells predicted early recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma after surgery. Hepatol Res. 2017;47:1061–1071. doi: 10.1111/hepr.12831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bronte V, Brandau S, Chen SH, Colombo MP, Frey AB, Greten TF, Mandruzzato S, Murray PJ, Ochoa A, Ostrand-Rosenberg S, et al. Recommendations for myeloid-derived suppressor cell nomenclature and characterization standards. Nat Commun. 2016;7:12150. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sanchez-Pino MD, Dean MJ, Ochoa AC. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSC): When good intentions go awry. Cell Immunol. 2021;362:104302. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2021.104302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ma J, Zheng B, Goswami S, Meng L, Zhang D, Cao C, Li T, Zhu F, Ma L, Zhang Z, et al. PD1Hi CD8+ T cells correlate with exhausted signature and poor clinical outcome in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Immunother Cancer. 2019;7:331. doi: 10.1186/s40425-019-0814-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Khan O, Giles JR, McDonald S, Manne S, Ngiow SF, Patel KP, Werner MT, Huang AC, Alexander KA, Wu JE, et al. TOX transcriptionally and epigenetically programs CD8+ T cell exhaustion. Nature. 2019;571:211–218. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1325-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhou J, Liu M, Sun H, Feng Y, Xu L, Chan AWH, Tong JH, Wong J, Chong CCN, Lai PBS, et al. Hepatoma-intrinsic CCRK inhibition diminishes myeloid-derived suppressor cell immunosuppression and enhances immune-checkpoint blockade efficacy. Gut. 2018;67:931. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2017-314032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Raber PL, Sierra RA, Thevenot PT, Shuzhong Z, Wyczechowska DD, Kumai T, Celis E, Rodriguez PC. T cells conditioned with MDSC show an increased anti-tumor activity after adoptive T cell based immunotherapy. Oncotarget. 2016;7:17565–17578. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.8197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Davis RJ, Moore EC, Clavijo PE, Friedman J, Cash H, Chen Z, Silvin C, Van Waes C, Allen C. Anti-PD-L1 efficacy can be enhanced by inhibition of myeloid-derived suppressor cells with a selective inhibitor of PI3Kδ/γ. Cancer Res. 2017;77:2607–2619. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-2534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sharma P, Allison JP. The future of immune checkpoint therapy. Science. 2015;348:56–61. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa8172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zou W, Wolchok JD, Chen L. PD-L1 (B7-H1) and PD-1 pathway blockade for cancer therapy: Mechanisms, response biomarkers, and combinations. Sci Transl Med. 2016;8:328rv4. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aad7118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brahmer JR, Tykodi SS, Chow LQ, Hwu WJ, Topalian SL, Hwu P, Drake CG, Camacho LH, Kauh J, Odunsi K, et al. Safety and activity of anti-PD-L1 antibody in patients with advanced cancer. New Engl J Med. 2012;366:2455–2465. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Borghaei H, Paz-Ares L, Horn L, Spigel DR, Steins M, Ready NE, Chow LQ, Vokes EE, Felip E, Holgado E, et al. Nivolumab versus docetaxel in advanced nonsquamous non-small-cell lung cancer. New Engl J Med. 2015;373:1627–1639. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1507643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kudo M. Immune checkpoint inhibition in hepatocellular carcinoma: basics and ongoing clinical trials. Oncology. 2017;92((Suppl 1)):S50–S62. doi: 10.1159/000451016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Prieto J, Melero I, Sangro B. Immunological landscape and immunotherapy of hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;12:681–700. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2015.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yugawa K, Itoh S, Yoshizumi T, Iseda N, Tomiyama T, Morinaga A, Toshima T, Harada N, Kohashi K, Oda Y, Mori M. CMTM6 stabilizes PD-L1 expression and is a new prognostic impact factor in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology Commun. 2021;5:334–348. doi: 10.1002/hep4.1643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu CQ, Xu J, Zhou ZG, Jin LL, Yu XJ, Xiao G, Lin J, Zhuang SM, Zhang YJ, Zheng L. Expression patterns of programmed death ligand 1 correlate with different microenvironments and patient prognosis in hepatocellular carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 2018;119:80–88. doi: 10.1038/s41416-018-0144-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Calderaro J, Rousseau B, Amaddeo G, Mercey M, Charpy C, Costentin C, Luciani A, Zafrani ES, Laurent A, Azoulay D, et al. Programmed death ligand 1 expression in hepatocellular carcinoma: Relationship with clinical and pathological features. Hepatology. 2016;64:2038–2046. doi: 10.1002/hep.28710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Iseda N, Itoh S, Yoshizumi T, Yugawa K, Morinaga A, Tomiyama T, Toshima T, Kohashi K, Oda Y, Mori M. ARID1A deficiency is associated with high programmed death ligand 1 expression in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology Commun. 2020;5:675–688. doi: 10.1002/hep4.1659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gao F, Yang C. Anti-VEGF/VEGFR2 monoclonal antibodies and their combinations with PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors in clinic. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2020;20:3–18. doi: 10.2174/1568009619666191114110359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kodumudi KN, Woan K, Gilvary DL, Sahakian E, Wei S, Djeu JY. A novel chemoimmunomodulating property of docetaxel: suppression of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in tumor bearers. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:4583–4594. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-0733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vincent J, Mignot G, Chalmin F, Ladoire S, Bruchard M, Chevriaux A, Martin F, Apetoh L, Rébé C, Ghiringhelli F. 5-fluorouracil selectively kills tumor-associated myeloid-derived suppressor cells resulting in enhanced T cell-dependent antitumor immunity. Cancer Res. 2010;70:3052–3061. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.