Key Points

Question

To what extent has physician-based mental health care utilization among children and adolescents changed through the COVID-19 pandemic?

Findings

In this population-based repeated cross-sectional study, following an initial large and rapid decline in mental health care utilization at the pandemic onset, utilization increased and was sustained at approximately 10% to 15% above expected levels through the first year of the pandemic, with 70% of care delivered virtually.

Meaning

System-level planning to monitor quality and ensure capacity for this modest but important rise in mental health care needs is warranted.

This population-based cross-sectional study evaluates utilization of outpatient mental health care services among children and adolescents in Ontario, Canada, during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Abstract

Importance

Public health measures to reduce the spread of COVID-19 have heightened distress among children and adolescents and contributed to a shift in delivery of mental health care services.

Objectives

To measure and compare physician-based outpatient mental health care utilization before and during the COVID-19 pandemic and quantify the extent of uptake of virtual care delivery.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Population-based repeated cross-sectional study using linked health and administrative databases in Ontario, Canada. All individuals aged 3 to 17 years residing in Ontario from January 1, 2017, to February 28, 2021.

Exposures

Pre–COVID-19 period from January 1, 2017, to February 29, 2020, and post–COVID-19 onset from March 1, 2020, to February 28, 2021.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Physician-based outpatient weekly visit rates per 1000 population for mental health diagnoses overall and stratified by age group, sex, and mental health diagnostic grouping and proportion of virtual visits. Poisson generalized estimating equations were used to model 3-year pre–COVID-19 trends and forecast expected trends post–COVID-19 onset and estimate the change in visit rates before and after the onset of COVID-19. The weekly proportions of virtual visits were calculated.

Results

In a population of almost 2.5 million children and adolescents (48.7% female; mean [SD] age, 10.1 [4.3] years), the weekly rate of mental health outpatient visits was 6.9 per 1000 population. Following the pandemic onset, visit rates declined rapidly to below expected (adjusted relative rate [aRR], 0.81; 95% CI, 0.79-0.82) in April 2020 followed by a growth to above expected (aRR, 1.07; 95% CI, 1.04-1.09) by July 2020 and sustained at 10% to 15% above expected as of February 2021. Adolescent female individuals had the greatest increase in visit rates relative to expected by the end of the study (aRR, 1.26; 95% CI, 1.25-1.28). Virtual care accounted for 5.0 visits per 1000 population (72.5%) of mental health visits over the study period, with a peak of 5.3 visits per 1000 population (90.1%) (April 2020) and leveling off to approximately 70% in the latter months.

Conclusions and Relevance

Physician-based outpatient mental health care in Ontario increased during the pandemic, accompanied by a large, rapid shift to virtual care. There was a disproportionate increase in use of mental health care services among adolescent female individuals. System-level planning to address the increasing capacity needs and to monitor quality of care with such large shifts is warranted.

Introduction

The public health measures implemented to manage the COVID-19 pandemic necessitated an unprecedented transformation in health care delivery1 and contributed to large shifts in health care needs and utilization.2,3 This global health emergency ignited a rapid adoption and restructuring of virtual care by health care professionals and organizations to help contain and address challenges presented by the coronavirus.4,5,6 The encouraged and accelerated transition to virtual care during the pandemic was facilitated by implementing new virtual care platforms, digital health innovations, and virtual care reimbursement models, with variation in uptake by jurisdiction, population, and disease grouping.7-9 Specific to outpatient mental health physician services, on March 14, 2020, in Ontario, Canada, the Ministry of Health added fee codes for assessments or counseling of insured persons by telephone or video.7 These included additional specific codes for mental health care above and beyond the infrequently used, more restrictive, preexisting telemedicine fee codes.8

Virtual mental health care has been presented as an innovative health strategy with the potential to improve engagement with patients through convenient access. However, virtual mental health care was underutilized by both patients and psychiatrists before the pandemic.9,10,11,12,13 The most important diagnostic tools in a psychiatric assessment include the history and mental status examination, both of which may be easily obtained virtually, especially for children and youth, who may be more accustomed to the technology. Studies on the effectiveness of telepsychiatry demonstrate that virtual and in-person visits have equivalent outcomes in patient satisfaction, adherence, and symptom reduction across diverse mental health conditions.11,14,15,16

In parallel to the shifts to virtual care delivery during the pandemic, social isolation, school closures, and other pandemic-related stressors have increased the risk of distress and mental illness among children and adolescents.17 This, in turn, may have increased demand for mental health services and resulted in an immediate need for a virtual care model that ensured access to care while adhering to health measures and guidelines aimed to reduce viral transmission and spread.18 However, both the extent of change in mental health care utilization at a population level and the magnitude of the shift to virtual care is not known but important for system-level planning.

In this study, our main objectives were to measure the temporal trends in outpatient physician-based mental health care utilization in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic and measure the extent of shift to virtual mental health care delivery. As a secondary objective and to provide broader system perspective, we sought to measure the temporal trends in acute care mental health utilization during the pandemic. We hypothesized that mental health care utilization would increase through the pandemic with a large, rapid, and sustained shift to virtual care. We further hypothesized that both overall utilization and uptake of virtual care would differ by diagnostic grouping (eg, anxiety, psychotic, and neurodevelopmental disorders) and be greater among adolescents compared with children aged 7 to 12 years.

Methods

We conducted a population-based, repeated cross-sectional study of all children and adolescents living in Ontario, Canada, and eligible for provincial health insurance between January 1, 2017, and February 28, 2021, using linked health administrative databases. We obtained data using unique encoded identifiers from linked population-based data sets available at ICES (formerly the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences), an independent research institute the legal status of which under Ontario’s health information privacy law allows it to collect and analyze health care and demographic data without individual patient consent for health system evaluation and improvement. Databases included the provincial health insurance registry (Ontario Registered Persons Database) and physician billings database (Ontario Health Insurance Plan database) to identify ambulatory care visits to family physicians, pediatricians, or psychiatrists for mental health care; the National Ambulatory Care Reporting System to ascertain mental health emergency department visits; and the Canadian Institute for Health Information’s Discharge Abstract Database and the Ontario Mental Health Reporting System to identify mental health hospitalizations (eTable 1 in the Supplement). The Research Ethics Board at The Hospital for Sick children approved this study. This study followed the Reporting of Studies Conducted Using Observational Routinely Collected Health Data (RECORD) Guidelines.19

Outcome Measures and Exposure

Our primary outcome was the count of mental health outpatient visits to a pediatrician, family physician, or psychiatrist. We assigned visits as either in-person or virtual, based on the location code from preexisting physician fee codes indicating a virtual visit or from any of the newly introduced virtual care codes (eTable 1 in the Supplement).8 Visits were further classified into broad diagnostic groupings widely used by our group using a validated algorithm modified for pediatric care.20 As a balancing measure to provide context within the broader mental health system, we also examined visits to acute care (emergency department [ED] visits and hospitalizations) overall and for select mental health diagnoses (International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision [ICD-10] main diagnostic codes F06-F99 or secondary diagnostic codes X60-X84, Y10-Y19, and Y28) or any Ontario Mental Health Reporting System hospitalization records (eTable 1 in the Supplement).

Visit rates were expressed per 1000 population overall and by age group (preschool [3 to 6 years], school age [7 to 12 years], and adolescent [13 to 17 years]), by sex (male and female), and by diagnostic group (mood and anxiety disorders, psychotic disorders, substance use disorders, social concerns, and neurodevelopmental and other concerns). We used the Ontario population on January 1 of each year (2017 to 2021) as the denominator (eTable 2 in the Supplement). Our exposure was the first 12 months of the COVID-19 pandemic, defined from March 1, 2020, to February 28, 2021, representing the onset of the pandemic in Ontario to the end of complete data availability.

Statistical Analyses

To measure changes in utilization of mental health care, we used Poisson generalized estimating equations models for clustered count data to model 3-year pre–COVID-19 trends and used these to forecast expected post–COVID-19 trends in the absence of restrictions.21 The unit of analysis was the age-sex-week stratum. The dependent variable was the stratum-specific count of events to the population in the stratum; the offset was the log of the stratum-specific population; the working correlation structure was AR(1) autocorrelation with a lag of 1, to account for correlations in visit rates over time. The pre–COVID-19 model included age-sex indicators, a continuous linear term of weeks since January 1, 2017, to estimate the secular trend in visit rates through February 29, 2020, and pre–COVID-19 month indicators to model monthly variations, with April as the reference month.

We computed the expected post–COVID-19 visit rates and 95% CIs by applying the linear combination of pre–COVID-19 regression coefficients to the post–COVID-19 age-sex-month strata and exponentiating. The relative change in post–COVID-19 visit rates was expressed as the ratio of observed to expected rates; these were obtained by calculating the difference between observed and expected post–COVID-19 log rates, computing standard errors and 95% CIs for this difference as it was a linear combination of regression coefficients, and finally exponentiating to express rates and 95% CIs on the original scale. To measure the extent of virtual mental health care utilization during the pandemic, we determined the proportion of overall weekly outpatient physician-based visits that had a virtual care fee code and plotted the age-sex and diagnosis-specific trends over time. Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS statistical software version 9.4 (SAS Institute).

Results

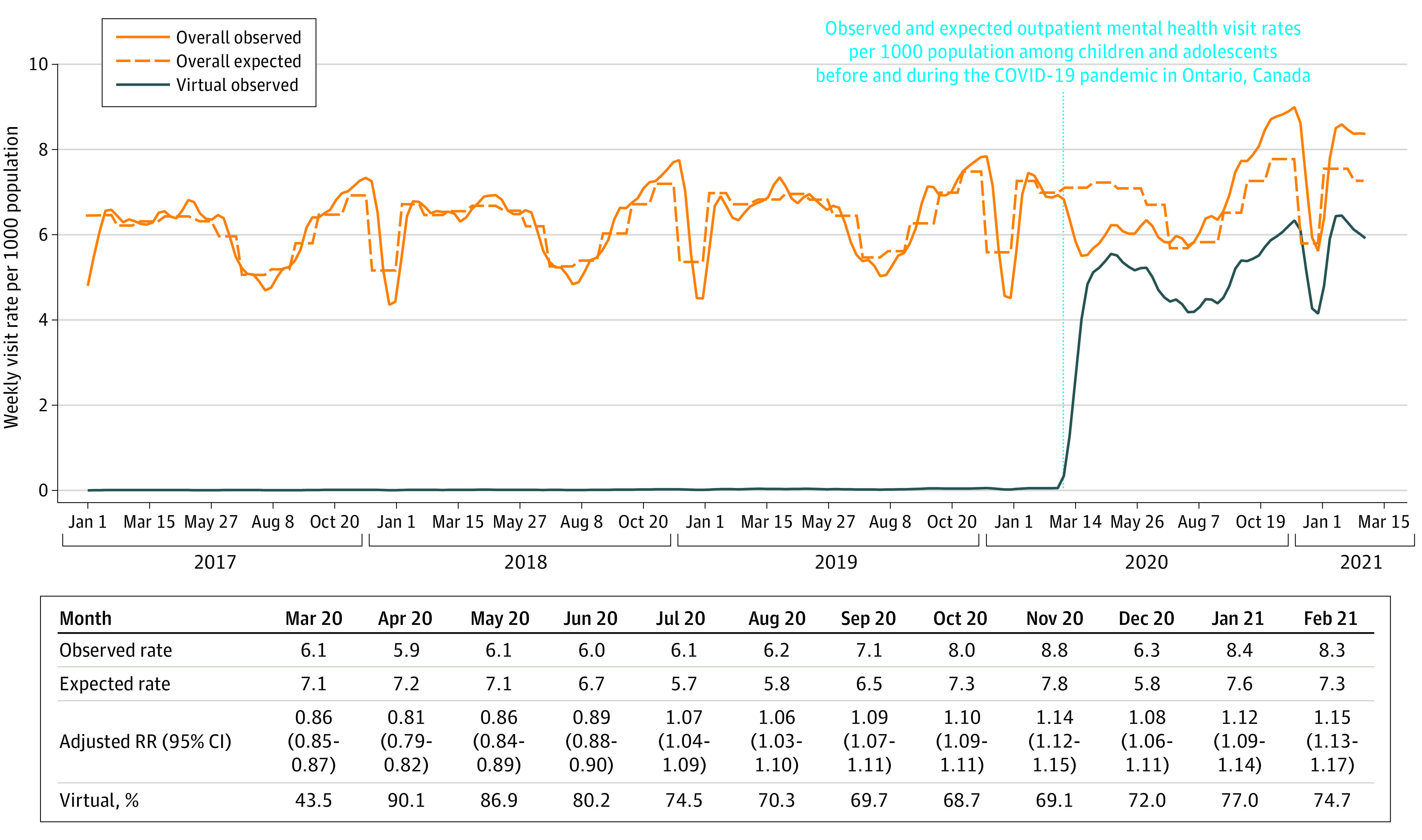

Almost 2.5 million Ontario children and adolescents were included in the annual denominator in the study with stable demographic characteristics across study years (eTable 2 in the Supplement). Of these, 1 181 864 (48.7%) were female, with a mean (SD) age of 10.1 (4.3) years. In the pre–COVID-19 period (January 1, 2017, to February 29, 2020), weekly visit rates for outpatient mental health care were 6.9 per 1000 population, with virtual visits making up 0.1% of visits (Figure 1). Physician-based outpatient mental health visit rates in the pre–COVID-19 period (all per 1000 population) were 2.7 (female individuals aged 3-6 years), 5.5 (male individuals aged 3-6 years), 4.4 (female individuals aged 7-12 years), 8.0 (male individuals aged 7-12 years), 11.2 (female individuals aged 13-17 years), and 8.1 (male individuals aged 13-17 years) (eTable 3 in the Supplement, expected rates). Visit rates per 1000 population were greatest for neurodevelopmental and other concerns (3.7), followed by mood and anxiety disorders (2.5) (eTable 4 in the Supplement).

Figure 1. Observed and Expected Outpatient Mental Health Care Visits Over Time in Ontario, Canada.

RR indicates rate ratio.

Changes in Outpatient Mental Health Care Utilization

In March 2020, the first month of the pandemic in Canada, the mental health outpatient care weekly visit rate was less than expected (6.1 vs 7.1/per 1000 population, adjusted relative rate [aRR], 0.86; 95% CI, 0.85-0.87; Figure 1), with virtual care jumping to 43.5% of visits. While the visit rate remained overall lower than expected through June 2020 with a nadir in April 2020 (adjusted relative rate [aRR)] 0.81; 95% CI 0.79-0.82), the proportion of visits conducted virtually was relatively high (90.1% in April [5.3 visits per 1000 population], 86.9% in May [4.8 visits per 1000 population], and 80.2% in June [4.8 visits per 1000 population]). From July 2020 onward, however, visit rates were slightly above expected levels (aRR, 1.07; 95% CI, 1.04-1.09 for July 2020), with sustained 6% to 15% increases above expected levels. Throughout the July 2020 to February 2021 period, virtual visits consistently made up about 70% to 75% of visits (Figure 1).

Age and Sex

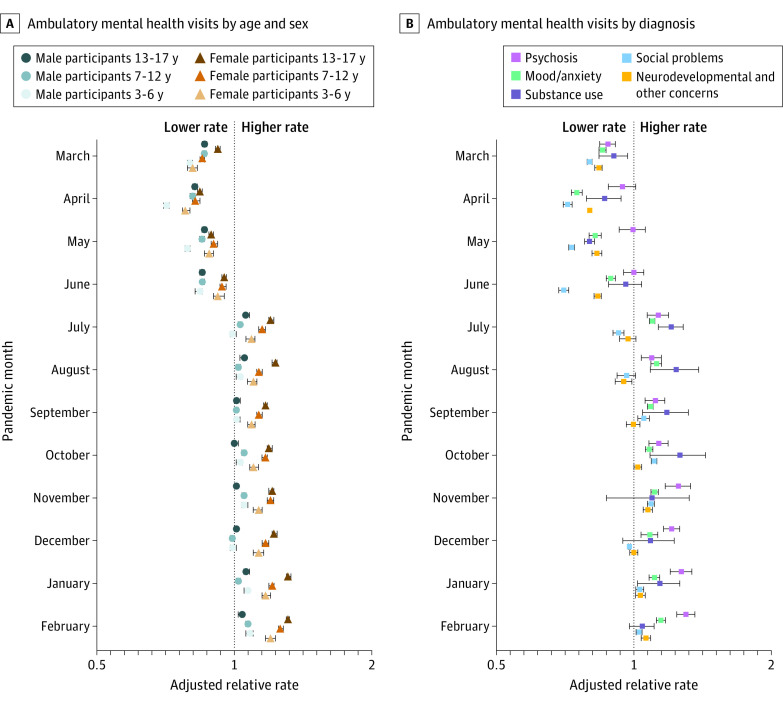

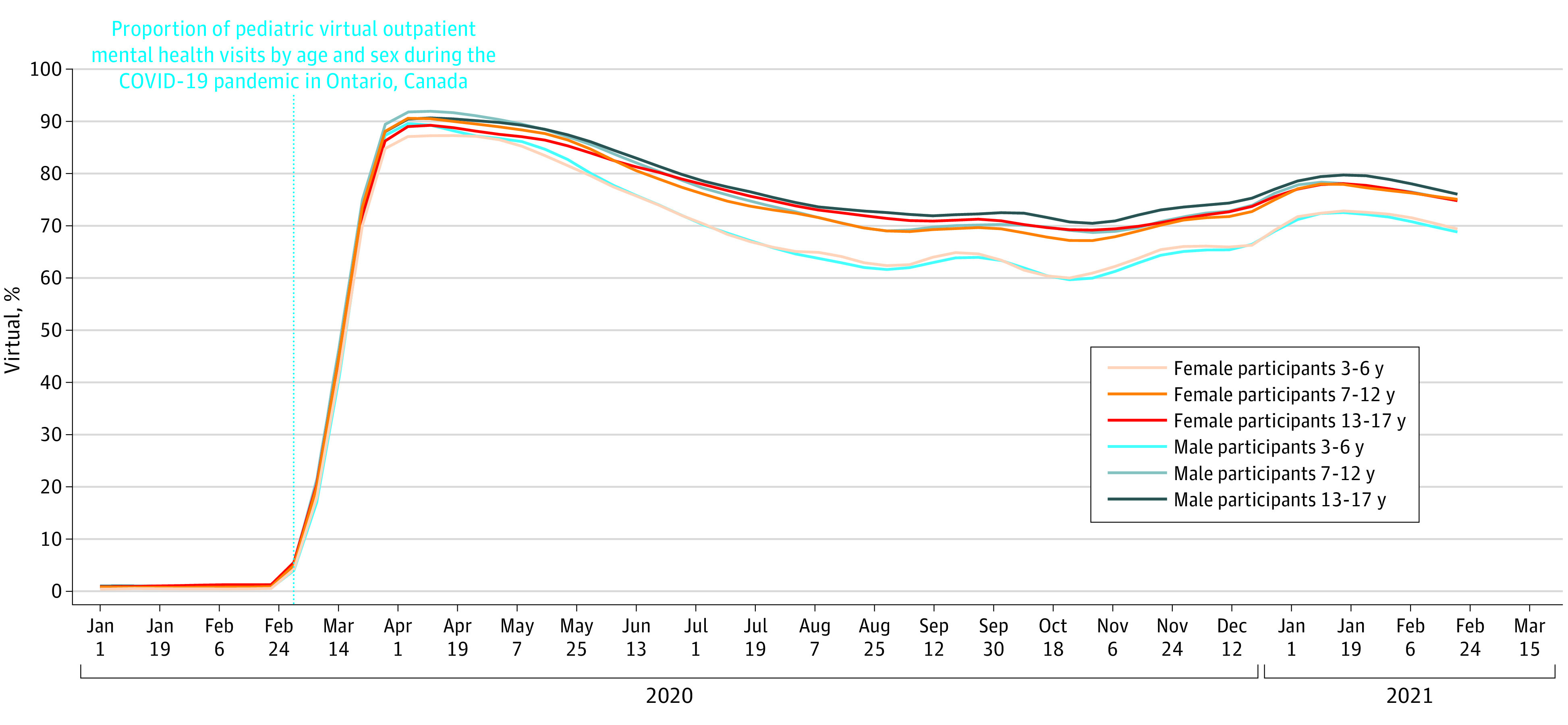

From March to June 2020, few differences were observed by age or sex, with all age-sex groups using physician-based outpatient mental health care below expected rates (Figure 2; eTable 3 in the Supplement). From July 2020 onward, female individuals, and especially adolescents aged 13 to 17 years, had visit rates 17% to 31% above expected, whereas visit rates among male individuals were at or just above expected (Figure 2; eTable 3 in the Supplement). The proportion of visits conducted virtually was initially similar for male and female individuals and by age group in March, April, and May 2020. After that time, the proportion of visits conducted virtually decreased most in the youngest age group (ages 3 to 6 years) than in the other age groups (Figure 3; eTable 3 in the Supplement).

Figure 2. Adjusted Relative Rate of Monthly Outpatient Mental Health Visits Following the Onset of the COVID-19 Pandemic in Ontario, Canada.

Figure 3. Proportion of Virtual Outpatient Mental Health Visits by Age and Sex in Ontario, Canada.

Diagnostic Groupings

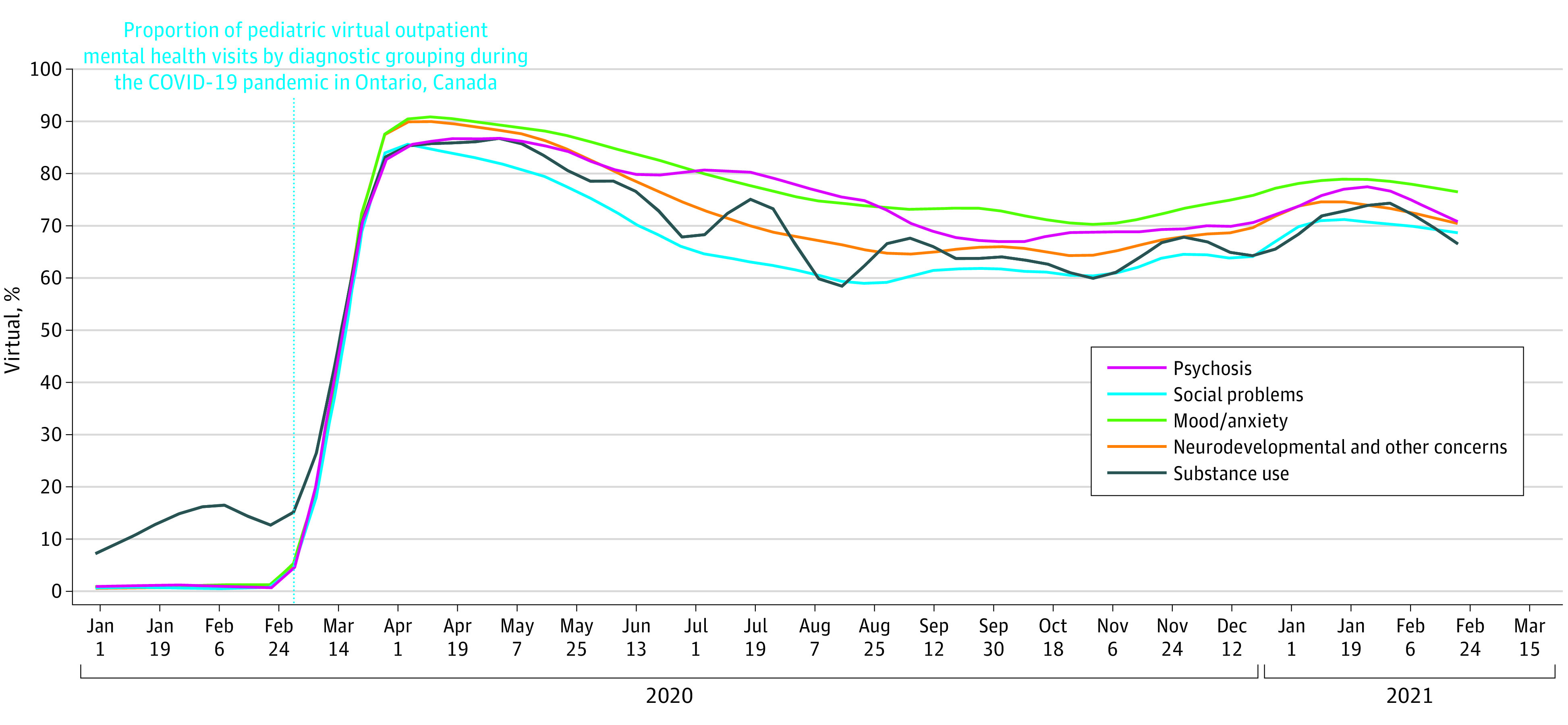

There was some variability in observed vs expected visit rates by diagnosis (Figure 2; eTable 4 in the Supplement). Increased visit rates compared with expected were seen by July 2020 for substance use disorders and for psychotic disorders. Both of these increases were sustained and above expected to the end of the study period, although visits for these disorders made up a small proportion of overall mental health visits. Visit rates for mood and anxiety disorders were elevated compared with expected in July 2020 (July observed 2.22 vs expected 2.02 visits per 1000 population; aRR, 1.10; 95% CI, 1.08-1.11), in alignment with the overall results. Visit rates for social problems and neurodevelopmental concerns followed a different pattern, with lower visit rates than expected from March to June and visit rates very similar to expected in July and August (as well as September for neurodevelopmental concerns), with increased visit rates only emerging in the late fall of 2020. The largest proportions of virtual visits over the entire study period were observed for mood and anxiety disorders (74.7%), psychosis (73.2%) and substance use disorders (83.6%), with clinically important lower proportions of virtual visits for social concerns (64.6%) and neurodevelopmental concerns (69.8%) (Figure 4; eTable 4 in the Supplement).

Figure 4. Proportion of Virtual Outpatient Mental Health Visits by Diagnoses in Ontario, Canada.

Changes in Acute Care Utilization

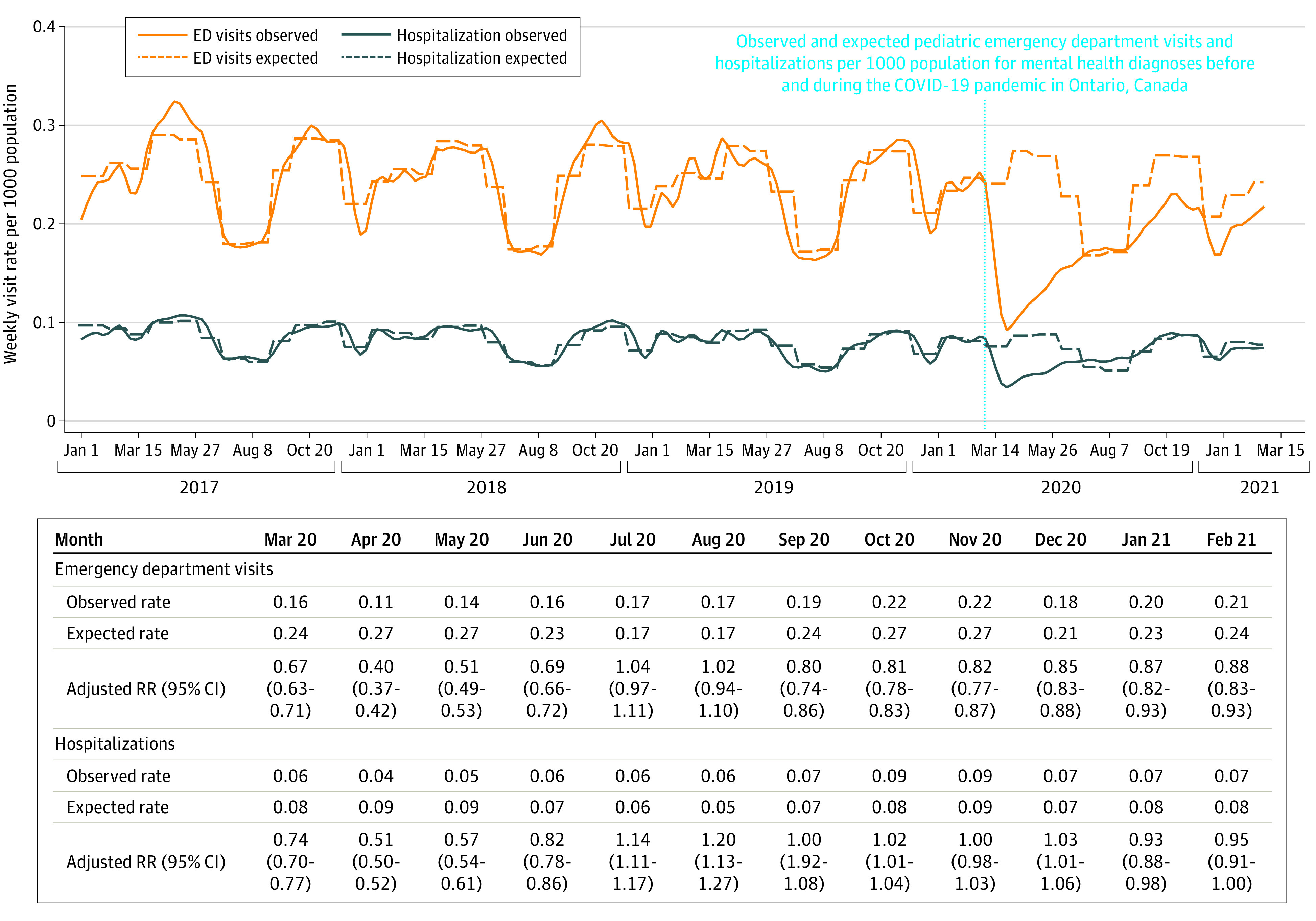

Figure 5 reports the changes in ED visits and hospitalizations for mental health concerns. There was an immediate rapid drop in ED visit rates (aRR, 0.40; 95% CI, 0.37-0.42 [April 2020]) followed by a return to expected levels by July 2020, but this was not sustained with visit rates 12% to 20% below expected from September 2020 to February 2021. Mental health hospitalizations decreased initially; however, they remained at or just above expected levels from July 2020 onward.

Figure 5. Observed and Expected Emergency Department Visits and Hospitalizations for Mental Health Diagnoses Over Time in Ontario, Canada.

RR indicates rate ratio.

ED visits were stratified by mental health diagnostic grouping (eTable 5 in the Supplement) and by age and sex (eTable 6 in the Supplement). Following the onset of the pandemic, visit rates were lower than expected overall for anxiety (aRR, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.71-0.86), mood disorders (aRR, 0.71; 95% CI, 0.67-0.76), substance use disorders (aRR, 0.69; 95% CI, 0.65-0.73), and trauma and stressor-related disorders (aRR, 0.68; 95% CI, 0.64-0.73). Overall, ED visits for psychotic disorders were higher than expected (aRR, 1.20; 95% CI, 1.02-1.41) following the onset of the pandemic.

Hospitalization rates overall and select mental health diagnoses (Figure 5; eTable 7 in the Supplement) were lower than expected following the onset of the pandemic except for psychotic disorders and substance use disorders, where observed hospitalization rates were greater than expected. Overall, hospitalization rates were lowest for anxiety (aRR, 0.73; 95% CI, 0.65-0.81) compared with other mental health diagnoses.

ED visits and hospitalizations following the onset of the pandemic were consistently at or higher than expected levels for female individuals and below expected levels for male individuals (eTable 6 and eTable 8 in the Supplement). The largest relative changes in ED visits and hospitalizations compared with expected were observed among female individuals aged 7 to 12 years.

Discussion

In this population-based study with inclusion of almost all children and adolescents in Ontario, physician-based outpatient mental health visit rates decreased initially for 4 months followed by a rapid increase and were sustained at approximately 10% to 15% above expected through the first 12 months of the COVID-19 pandemic. This increase in outpatient mental health visits occurred in contrast to the relatively large initial decrease in emergency department visits and hospitalizations that was sustained at or below expected levels through the latter half of the first year of the pandemic. We observed striking sex-based differences in mental health care utilization following the pandemic onset relative to expected levels, with school-aged and adolescent female individuals seemingly more affected by pandemic-related changes than male individuals and preschool-aged children. While there was heterogeneity in observed vs expected changes in utilization by diagnostic category, the moderate and lasting increase in visits for substance use disorder in both outpatient and hospital settings warrants attention and continued monitoring. We report a large shift in care modality, with three-fourths of outpatient mental health care visits delivered virtually, a proportion larger and more sustained than reported for any other population, disease grouping, or jurisdiction.6,22,23,24,25

Extensive media coverage26,27 and survey data28,29 have reported on the deleterious effects of the pandemic on the mental health of children and adolescents. Our findings suggest that population-level demand for outpatient mental health care increased above expected through the fall of 2020, corresponding to the start of a second wave of COVID-19 in Ontario with a continued rise in the winter of 2020 and early 2021 at the peak of lockdown measures. In contrast, we did not observe a significant rise in overall acute mental health care utilization for children and adolescents through the first 12 months of the pandemic, except for hospitalization among school-aged and adolescent female individuals. Indeed, distress may not equate to mental health disorders or the need for acute mental health care services. We speculate that the shift in case mix toward less acute disorders, better suited to ambulatory care (eg, anxiety disorder and substance use disorder) or perhaps virtual care settings, may explain our results. Fear of or barriers to attending acute care may have contributed to these findings. Other population-level studies across all age groups in the US have shown reduced acute care visits for mental illness30 and suicide31,32 following the pandemic onset. One other large US study showed a slight increase in ED visits for mental health concerns.3 The novel observation of large sex-based differences in pediatric mental health care utilization suggests pandemic-related changes disproportionately affected young female individuals and specific attention must be paid to ensure equity in and adequacy of supports for this sector of the population. Taken together with our findings, changes to mental health care utilization for children and adolescents through the pandemic have been heterogeneous, and trends need to be examined by age group and disease to describe emerging COVID-19 patterns more fully. Further, given the chronic and cumulative nature of distress on mental health and well-being, the impact of the pandemic on the mental health of children and adolescents is likely not yet fully realized.

The widespread shift to virtual mental health care has not been matched in other sectors, including pediatric primary care33,34 and ambulatory care more broadly,6,35 or in other jurisdictions.6,36 This shift in care delivery can improve access to timely developmental and mental health care, reduce indirect costs of missed school or caregiver work time, and improve patient and caregiver satisfaction. Although the proportion of virtual care visits was not sustained through the whole study period, peaking at over 90% of visits in April 2020, virtual care remained the predominant mode of care delivery for mental health care visits, despite episodes of low COVID-19 infection rates during the defined study period.37

In Ontario, virtual care was supported by a fee structure to remunerate physicians to deliver such care.7 In contrast, in jurisdictions where remuneration was lower, uptake of virtual care was inadequate and may partly explain the variation observed.33,35 Among children and adolescents, evidence supporting the feasibility, acceptability, and effectiveness of virtual care for both mental health assessments and treatment is emerging incrementally.38 In addition to overall therapeutic effectiveness, there is a high degree of practitioner satisfaction and enhanced capacity of practitioners and families and lower system costs.39 The overall efficacy of virtual care compared with in-person visits and which diagnostic groupings benefit the most is not yet fully understood and will be essential to monitor as virtual care services continue to be broadly used. This is particularly true for neurodevelopmental conditions where direct observation of a child may be needed and in-person assessments are likely appropriate. Ongoing funding will be needed to support continued virtual care delivery, as well as digital health platforms. In addition, training and support programs should be implemented to ensure that clinicians can deliver high-quality virtual mental health care.

Limitations

Strengths of this study include the use of population-wide measures of mental health care utilization through the first 12 months of the pandemic in a publicly funded health care system. We were limited by the inability to measure population-level mental health care unmet needs and non–physician-based care delivered by social workers, psychologists, and other therapists, who are not linked in available data sets and who provide a material amount of care in Ontario. Our virtual care fee codes do not distinguish between telephone and video visits, which may affect the quality of mental health assessment and counselling. Outpatient data, while validated to identify mental health visits broadly,20 could only be categorized into large diagnostic groups based on physician billing diagnostic codes rather than clinical diagnostic criteria. This precluded assessment of more granular changes in utilization by diagnosis, such as eating disorders. While other jurisdictions have also implemented billing codes for virtual care, remuneration may differ and may affect the extent of virtual care uptake, limiting generalizability. Individual-level measures of the child or adolescent or family were not available in existing data to further contextualize utilization. We attributed observed changes in health system utilization to the pandemic, although other unobserved factors may be contributing to our findings. Furthermore, our data measure utilization through February 2021, and the longer-term impact of the pandemic on mental health care utilization by children and adolescents remains to be studied.

Conclusions

In this cross-sectional population-based study, we found increasing rates in outpatient mental health care visits, especially among adolescents and female individuals, with relatively stable acute mental health care utilization and a large and rapid shift to virtual physician-based mental health care for children and adolescents through the first 12 months of the COVID-19 pandemic. These findings point to a need for increased capacity to ensure timely access to appropriate treatment for those seeking care and a need for system-level planning and implementation of virtual care to optimize access and quality of mental health care services. The longer-term patterns of virtual care utilization and impact on the access and quality of care warrant further study.

eTable 1. Ontario Health Insurance Plan and International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision mental health diagnostic codes and groupings

eTable 2. Baseline demographic characteristics of children and adolescents, ages 3 to 17 years in Ontario, 2017-2021

eTable 3. Observed and expected rates and adjusted relative change (RR, 95% CI) in outpatient visits in Ontario during the post-pandemic era. Rates are average weekly visit rates per 1000 population

eTable 4. Observed and expected rates and adjusted relative change (RR, 95% CI) in outpatient visits in Ontario during the post-pandemic era. Rates are average weekly visit rates per 1000 population

eTable 5. Observed, expected and adjusted relative change (RR, 95% CI) in ED visits in Ontario, during the post-pandemic era, by mental health diagnosis. All rates are weekly visit rates per 1000 population

eTable 6. Observed and expected rates and adjusted relative change (RR, 95% CI) in ED visits in Ontario during the post-pandemic era. Rates are average weekly visit rates per 1000 population

eTable 7. Observed, expected and adjusted relative change (RR, 95% CI) in hospitalizations in Ontario, during the post-pandemic era, by mental health diagnosis. All rates are weekly visit rates per 1000 population

eTable 8. Observed and expected rates and adjusted relative change (RR, 95% CI) in hospitalizations in Ontario during the post-pandemic era. Rates are average weekly visit rates per 1000 population

References

- 1.WHO Director-General’s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19—11 March 2020. News release. World Health Organization; March 11, 2020. https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---11-march-2020

- 2.Williams TC, MacRae C, Swann OV, et al. Indirect effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on paediatric healthcare use and severe disease: a retrospective national cohort study. Arch Dis Child. 2021;106(9):911-917. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2020-321008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Holland KM, Jones C, Vivolo-Kantor AM, et al. Trends in US emergency department visits for mental health, overdose, and violence outcomes before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Psychiatry. 2021;78(4):372-379. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.4402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mann DM, Chen J, Chunara R, Testa PA, Nov O. COVID-19 transforms health care through telemedicine: evidence from the field. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2020;27(7):1132-1135. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocaa072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Webster P. Virtual health care in the era of COVID-19. Lancet. 2020;395(10231):1180-1181. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30818-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weiner JP, Bandeian S, Hatef E, Lans D, Liu A, Lemke KW. In-person and telehealth ambulatory contacts and costs in a large US insured cohort before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(3):e212618. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.2618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-term Care. Changes to the schedule of benefits for physician services (schedule) in response to COVID-19 influenza pandemic effective March 14, 2020. Health Services Branch, Ministry of Health, bulletin 4745;2020. Accessed July 1, 2020. https://www.health.gov.on.ca/en/pro/programs/ohip/bulletins/4000/bul4745.aspx

- 8.Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-term Care. Virtual Care Program—Billing Amendments to Enable Direct-to-Patient Video Visits and Modernize Virtual Care Compensation. Ontario: Claims Services Branch, Ministry of Health, bulletin 4731;2019. Accessed July 1, 2020. https://www.health.gov.on.ca/en/pro/programs/ohip/bulletins/4000/bul4731.aspx

- 9.Serhal E, Crawford A, Cheng J, Kurdyak P. Implementation and utilisation of telepsychiatry in Ontario: a population-based study. Can J Psychiatry. 2017;62(10):716-725. doi: 10.1177/0706743717711171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fortney JC, Pyne JM, Turner EE, et al. Telepsychiatry integration of mental health services into rural primary care settings. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2015;27(6):525-539. doi: 10.3109/09540261.2015.1085838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chipps J, Brysiewicz P, Mars M. Effectiveness and feasibility of telepsychiatry in resource constrained environments? a systematic review of the evidence. Afr J Psychiatry (Johannesbg). 2012;15(4):235-243. doi: 10.4314/ajpsy.v15i4.30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Greenberg N, Boydell KM, Volpe T. Pediatric telepsychiatry in Ontario: caregiver and service provider perspectives. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2006;33(1):105-111. doi: 10.1007/s11414-005-9001-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pignatiello A, Teshima J, Boydell KM, Minden D, Volpe T, Braunberger PG. Child and youth telepsychiatry in rural and remote primary care. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2011;20(1):13-28. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2010.08.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hilty DM, Ferrer DC, Parish MB, Johnston B, Callahan EJ, Yellowlees PM. The effectiveness of telemental health: a 2013 review. Telemed J E Health. 2013;19(6):444-454. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2013.0075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bishop JE, O’Reilly RL, Maddox K, Hutchinson LJ. Client satisfaction in a feasibility study comparing face-to-face interviews with telepsychiatry. J Telemed Telecare. 2002;8(4):217-221. doi: 10.1258/135763302320272185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.O’Reilly R, Bishop J, Maddox K, Hutchinson L, Fisman M, Takhar J. Is telepsychiatry equivalent to face-to-face psychiatry? results from a randomized controlled equivalence trial. Psychiatr Serv. 2007;58(6):836-843. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.6.836 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cost KT, Crosbie J, Anagnostou E, et al. Mostly worse, occasionally better: impact of COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of Canadian children and adolescents. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2021. doi: 10.1007/s00787-021-01744-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Canadian Institute for Health Information . COVID-19 intervention timeline in Canada. Accessed July 11, 2021. https://www.cihi.ca/en/covid-19-intervention-timeline-in-canada

- 19.Benchimol EI, Smeeth L, Guttmann A, et al. ; RECORD Working Committee . The Reporting of Studies Conducted Using Observational Routinely-collected Health Data (RECORD) statement. PLoS Med. 2015;12(10):e1001885. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Steele LS, Glazier RH, Lin E, Evans M. Using administrative data to measure ambulatory mental health service provision in primary care. Med Care. 2004;42(10):960-965. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200410000-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schull MJ, Stukel TA, Vermeulen MJ, Alter D. Study design to determine the effects of widespread restrictions on hospital utilization to control an outbreak of SARS in Toronto, Canada. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2006;6(3):285-292. doi: 10.1586/14737167.6.3.285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chunara R, Zhao Y, Chen J, et al. Telemedicine and healthcare disparities: a cohort study in a large healthcare system in New York City during COVID-19. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2021;28(1):33-41. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocaa217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Patel SY, Mehrotra A, Huskamp HA, Uscher-Pines L, Ganguli I, Barnett ML. Variation in telemedicine use and outpatient care during the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. Health Aff (Millwood). 2021;40(2):349-358. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2020.01786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Patel SY, Mehrotra A, Huskamp HA, Uscher-Pines L, Ganguli I, Barnett ML. Trends in outpatient care delivery and telemedicine during the COVID-19 pandemic in the US. JAMA Intern Med. 2021;181(3):388-391. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.5928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Glazier RH, Green ME, Wu FC, Frymire E, Kopp A, Kiran T. Shifts in office and virtual primary care during the early COVID-19 pandemic in Ontario, Canada. CMAJ. 2021;193(6):E200-E210. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.202303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Casey L. ‘Kids are not all right’: mental health among Ontario children deteriorating during COVID-19. Global News. Published February 2, 2021. Accessed August 1, 2021. https://globalnews.ca/news/7615078/ontario-children-mental-health-coronavirus-covid-19/

- 27.Liu S. ‘They are all changed’: what more than a year of pandemic isolation means for youth mental health. CTV News. Published April 14, 2021. Accessed July 23, 2021. https://www.ctvnews.ca/health/coronavirus/they-are-all-changed-what-more-than-a-year-of-pandemic-isolation-means-for-youth-mental-health-1.5387300

- 28.Statistics Canada . Impacts on mental health. Accessed June 29, 2021. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/11-631-x/2020004/s3-eng.htm

- 29.Centre for Addiction and Mental Health . COVID-19 national survey dashboard. Accessed June 24, 2020. https://www.camh.ca/en/health-info/mental-health-and-covid-19/covid-19-national-survey

- 30.Simpson SA, Loh RM, Cabrera M, et al. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on psychiatric emergency service volume and hospital admissions. J Acad Consult Liaison Psychiatry. 2021;62(6):588-594. doi: 10.1016/j.jaclp.2021.05.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Faust JS, Shah SB, Du C, Li SX, Lin Z, Krumholz HM. Suicide deaths during the COVID-19 stay-at-home advisory in Massachusetts, March to May 2020. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(1):e2034273. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.34273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Faust JS, Du C, Mayes KD, et al. Mortality from drug overdoses, homicides, unintentional injuries, motor vehicle crashes, and suicides during the pandemic, March-August 2020. JAMA. 2021;326(1):84-86. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.8012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Macy ML, Huetteman P, Kan K. Changes in primary care visits in the 24 weeks after COVID-19 stay-at-home orders relative to the comparable time period in 2019 in metropolitan Chicago and northern Illinois. J Prim Care Community Health. 2020;11:2150132720969557. doi: 10.1177/2150132720969557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Siedner MJ, Kraemer JD, Meyer MJ, et al. Access to primary healthcare during lockdown measures for COVID-19 in rural South Africa: a longitudinal cohort study. medRxiv. Preprint posted online May 20, 2020. doi: 10.1101/2020.05.15.20103226 [DOI]

- 35.Alexander GC, Tajanlangit M, Heyward J, Mansour O, Qato DM, Stafford RS. Use and content of primary care office-based vs telemedicine care visits during the COVID-19 pandemic in the US. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(10):e2021476. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.21476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Epic Research . Expansion of telehealth during COVID-19 pandemic. Published May 5, 2020. Accessed June 24, 2020. https://ehrn.org/articles/expansion-of-telehealth-during-covid-19-pandemic

- 37.Public Health Ontario . COVID-19 data and surveillance. Accessed June 16, 2021. https://www.publichealthontario.ca/en/data-and-analysis/infectious-disease/covid-19-data-surveillance

- 38.Myers KM, Valentine JM, Melzer SM. Feasibility, acceptability, and sustainability of telepsychiatry for children and adolescents. Psychiatr Serv. 2007;58(11):1493-1496. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.11.1493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Serhal E, Lazor T, Kurdyak P, et al. A cost analysis comparing telepsychiatry to in-person psychiatric outreach and patient travel reimbursement in Northern Ontario communities. J Telemed Telecare. 2020;26(10):607-618. doi: 10.1177/1357633X19853139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mansour O, Tajanlangit M, Heyward J, Mojtabai R, Alexander GC. Telemedicine and office-based care for behavioral and psychiatric conditions during the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. Ann Intern Med. 2021;174(3):428-430. doi: 10.7326/M20-6243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Ontario Health Insurance Plan and International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision mental health diagnostic codes and groupings

eTable 2. Baseline demographic characteristics of children and adolescents, ages 3 to 17 years in Ontario, 2017-2021

eTable 3. Observed and expected rates and adjusted relative change (RR, 95% CI) in outpatient visits in Ontario during the post-pandemic era. Rates are average weekly visit rates per 1000 population

eTable 4. Observed and expected rates and adjusted relative change (RR, 95% CI) in outpatient visits in Ontario during the post-pandemic era. Rates are average weekly visit rates per 1000 population

eTable 5. Observed, expected and adjusted relative change (RR, 95% CI) in ED visits in Ontario, during the post-pandemic era, by mental health diagnosis. All rates are weekly visit rates per 1000 population

eTable 6. Observed and expected rates and adjusted relative change (RR, 95% CI) in ED visits in Ontario during the post-pandemic era. Rates are average weekly visit rates per 1000 population

eTable 7. Observed, expected and adjusted relative change (RR, 95% CI) in hospitalizations in Ontario, during the post-pandemic era, by mental health diagnosis. All rates are weekly visit rates per 1000 population

eTable 8. Observed and expected rates and adjusted relative change (RR, 95% CI) in hospitalizations in Ontario during the post-pandemic era. Rates are average weekly visit rates per 1000 population