Abstract

Liver transplant recipients (LTRs) are at high risk for cardiovascular disease (CVD). We sought to characterize LTR, informal caregiver, and health care provider perceptions about CVD care after liver transplantation (LT) to inform the design of solutions to improve care. Participants included adult LTRs, their caregivers, and multispecialty health care providers recruited from an urban tertiary care network who participated in 90-minute focus groups and completed a brief survey. Focus group transcripts were analyzed using thematic analysis, and survey data were analyzed using descriptive statistics. A total of 17 LTRs, 9 caregivers, and 22 providers participated in 7 separate focus groups. Most (93.3%) LTRs and caregivers were unaware of the risk of CVD after LT. Although 54.5% of providers were confident discussing CVD risk factors with LTRs, only 36.3% were confident managing CVD risk factors in LTRs, and only 13.6% felt that CVD risk factors in their LTR patients were well controlled. Barriers to CVD care for LTRs included (1) lack of awareness of CVD risk after LT, (2) lack of confidence in an ability to provide proper CVD care to LTRs, (3) reluctance to provide CVD care without transplant provider review, and (4) complexity of communication with the multidisciplinary LTR care team about CVD care. Participant recommendations included improved education for LTRs and caregivers about CVD risk factors, electronic health record alerts for providers, clearly defined CVD care provider roles, increased use of the transplant pharmacist, and multidisciplinary provider meetings to discuss care plans for LTRs. Multiple barriers to CVD care after LT were identified, and targeted recommendations were proposed by participants. Transplant centers should integrate participants’ recommendations when designing interventions to optimize CVD care for LTRs.

Liver transplantation (LT) uses a scarce resource, is a major health care investment ($1.4 million = average LT cost), and requires months devoted to surgical recovery by patients and their caregivers.(1) Thus, the care and monitoring of liver transplant recipients (LTRs) is paramount. Yet, cardiovascular disease (CVD) is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality after LT.(2–5) Approximately 1 in 3 LTRs will have a CVD complication after LT.(2,3,5) CVD among LTRs is expected to increase in the coming years, with traditional CVD risk factors (ie, older age, obesity, and diabetes mellitus) becoming more common.(2,3,6–8) Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis is a leading indication for LT in the United States and is also associated with high CVD morbidity and mortality.(9) Posttransplant immunosuppression leads to increased CVD risk such as hypertension, dyslipidemia, insulin resistance, weight gain, and renal disease.(10)

Given LTRs’ high risk of developing CVD after LT, targeted preventive care is needed. However, a practice gap appears to exist between knowing about CVD risk factors and managing them. We recently demonstrated in 602 LTRs that only 29% had blood pressure controlled to the guideline-recommended target of <140/<90 mm Hg, which is associated with improved survival and decreased CVD events.(11) Furthermore, less than one-third of those who did not meet guideline-recommended blood pressure targets were referred to a hypertension specialist for additional management, highlighting an important area for quality improvement.(11) Data from other transplant centers have demonstrated similar practice gaps wherein LTRs do not receive appropriate guideline-directed CVD treatments, such as statin use for secondary prevention of atherosclerotic CVD.(12)

LTRs, their informal caregivers, and their health care providers (“providers,” eg, physicians, nurses, mid-level providers, pharmacists) play a role in mitigating the risk of CVD. Given the high risk of CVD in LTRs, we sought to understand patient, caregiver, and provider perceptions of CVD care after LT, particularly barriers to CVD care after LT, which have not previously been described. Moreover, we elicited potential recommendations to address the identified barriers and improve CVD care after LT.

Patients and Methods

STUDY DESIGN

Focus groups and post–focus group surveys were administered sequentially on the same day. Focus groups assessed participants’ experiences, perceptions, and information needs about CVD care after LT and elicited recommendations to address the identified barriers. A standardized focus group moderator guide was used and included open-ended questions based on the Health Belief Model(13) (Supporting Information A and B). The content of the moderator guide was iteratively modified as new topics emerged from the focus groups.

The surveys assessed participant demographics and information about the perceived severity of CVD in the LTRs, susceptibility of the LTRs to develop CVD, and self-efficacy for managing CVD and its related risk factors after LT (Supporting Information C). Participants were asked to rate their agreement with statements on a 5-point Likert scale, anchored by “strongly disagree” and “strongly agree.” The study protocol conformed to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Northwestern University Institutional Review Board (STU00205016), and all participants provided written informed consent.

STUDY SAMPLE AND RECRUITMENT

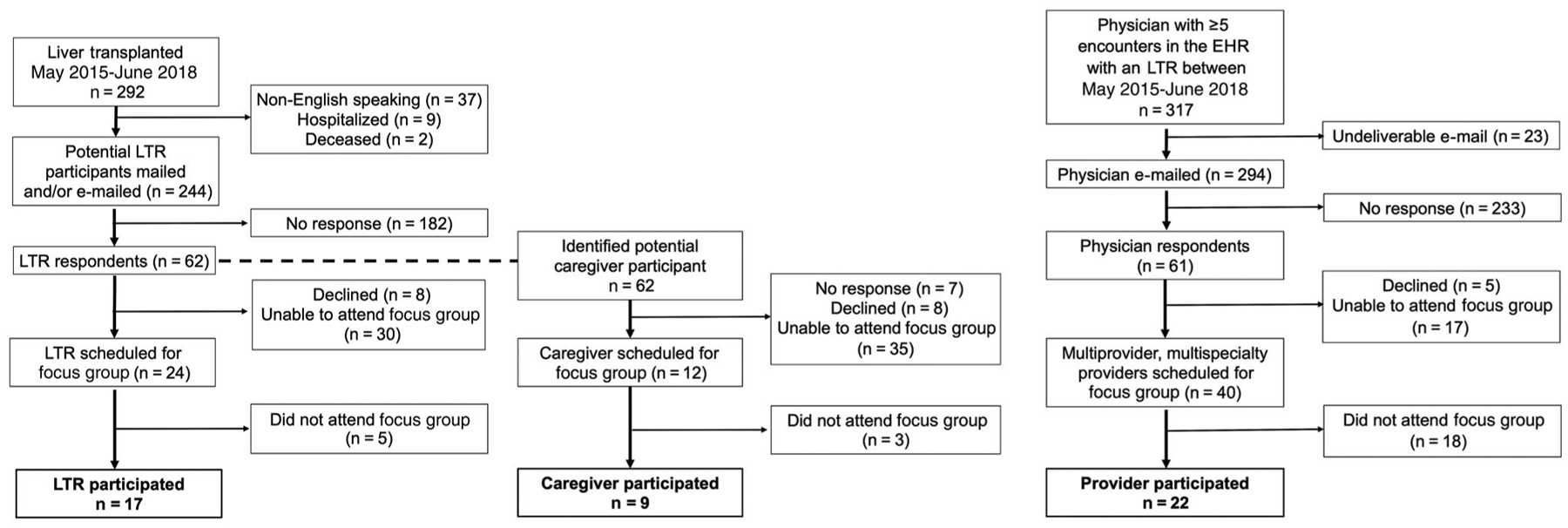

Patients who had undergone an LT between May 2015 and June 2018 and informal caregivers, identified by each LTR, who were aged 18 years or older, English-speaking, and able to participate in an informed consent were eligible to participate. Consecutive sampling was used to recruit these participants. The nonpurposive sampling approach was chosen because of its efficiency and ability to obtain a diverse sample population in a timely manner. To minimize the potential for selection bias common to this type of sampling, we recruited all participants during a set time frame and used a priori criteria for both study entry and the number and size of the focus groups needed to reach theoretical saturation based on prior research experience. The Northwestern Medicine Enterprise Data Warehouse (NMEDW), which contains clinical data for 7.5 million individual patients at all Northwestern Medicine sites, was used to identify the LTRs (n = 292). Of these, 48 LTRs were ineligible for participation (Fig. 1). The remaining LTRs and their informal caregivers were invited to participate in the study via e-mail or mail (n = 244). LTRs’ informal caregivers were recruited by having LTRs ask their caregivers to opt in and call the research team to provide consent. Respondents (n = 62, 25.4%) and their caregivers were then recruited in person during a previously scheduled clinic appointment on the Northwestern Medicine Chicago campus.

Fig. 1.

Participant eligibility diagram.

First, multispecialty (eg, general nephrology, transplant surgery, transplant hepatology, transplant nephrology, endocrinology, primary care, or cardiology) physicians were identified through the NMEDW. A physician was eligible for participation if he or she had at least 5 documented encounters with an LTR between May 2015 and June 2018 (n = 317). Physicians were invited to participate in the study via e-mail. Physician respondents were asked, in turn, to identify their multiprovider support staff (eg, nurses, mid-level providers, pharmacists, and social workers) who were then invited to participate in a focus group. To accommodate the clinical commitments of providers, groups were offered at various times throughout the early morning or late evening. Recruitment goals were to enroll approximately 20 total LTRs and their caregivers and 30 specialty-specific providers for a total enrollment of approximately 50 participants with equal numbers of men and women in each group.

Recruitment of all participants and the focus group interviews were completed between August 2018 and September 2018.

DATA COLLECTION METHODS AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

A total of 7 separate focus groups were conducted at the Northwestern Medicine Chicago campus with 6 to 8 participants in each focus group based on whether participants were LTRs (n = 2 groups), informal caregivers to an LTR (n = 1 group), or providers for LTRs (general cardiology [n = 1 group], transplant medicine [n = 1 group], general nephrology and endocrinology [n = 1 group], and primary care [n = 1 group]). An experienced facilitator (L.V.W., J.L.H., or E.G.) moderated each focus group for a 90-minute discussion using the standardized moderator guide with customized questions for each participant group (Supporting Information B). The moderator guide was developed by the principal investigator (L.V.W.) with study team members (J.L.H. and E.G.) who have previous qualitative research experience. All focus group sessions were audio recorded with field notes. The audio recordings of each focus group were professionally transcribed verbatim and uploaded into the MAXQDA software (VERBI GmBH, Berlin, Germany; https://www.maxqda.com/qualitative-analysis-software?gclid=CjwKCAiAl4WABhAJEiwATUnEF5RPA5GRLxeO6Be2gJYLqnx-jEKPwPivDPX1-eoq9Jd7jN3HE9CXeRoCwkEQAvD_BwE). A total of 6 investigators from diverse professional backgrounds (T.H. and B.A., general internal medicine; L.V.W. and A.D., transplant medicine; J.L.H. and D.J.F., health care delivery science) independently reviewed a set of transcripts and generated initial codes. Meetings of at least 3 reviewers of each transcript were held to reach consensus on the codes. A final code book was created, and all transcripts were recoded using the final codebook. It was determined that theoretical saturation was reached when concepts and themes were redundant with previous observations. Descriptive statistics (eg, frequencies) were used to analyze the survey responses using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 23 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY).

Results

DEMOGRAPHICS

Of the 158 eligible participants who responded to the invitation to take part in the study, 30.4% (17 LTRs, 9 caregivers, 22 providers) participated in a focus group, and 29.4% (17 LTRs, 8 caregivers, and 22 providers) completed the survey (Table 1). Mean age of the LTRs was 63.3 (standard deviation [SD], 6.2) years, of which 70.6% were men, 76.5% self-identified as White, and 17.6% self-identified as Hispanic. Most LTRs had received an LT within a median of 28 (range, 7–52) months prior to the focus group. By self-report, 75.0% of LTRs had at least 1 CVD condition or CVD-related risk factor. Using publicly available data from the Organ Procurement and Transplantation database, the mean age (63.3 versus 62.7 years), sex (70.0% men versus 68.0% men), and race/ethnicity (76.5% versus 71.7% White, and 17.0% versus 15.0% Hispanic) of the sample LTR population was similar to that reported by our institution to United Network for Organ Sharing during the study eligibility time period (2015–2018).(14)

TABLE 1.

Participant Demographics and Characteristics

| Characteristic | LTR | Informal Caregiver | Health Care Provider |

|---|---|---|---|

| Respondent | 17 (36.2) | 8 (17.0) | 22 (46.8) |

| Male | 12 (70.6) | 2 (22.2) | 9 (40.9) |

| Age, years | 63.3 ± 6.2 | 59.0 ± 10.3 | 43.2 ± 11.6 |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| White | 13 (76.5) | 5 (62.5) | 10 (45.5) |

| Black | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Asian | 0 | 1 (12.5) | 8 (36.4) |

| Hispanic | 3 (17.6) | 2 (25.0) | 4 (18.2) |

| Other | 1 (5.9) | 0 | 0 |

| Marital status | |||

| Married/domestic partner/civil union | 12 (70.6) | 5 (62.5) | 16 (72.7) |

| Separated or divorced | 4 (23.5) | 0 | 2 (9.1) |

| Widowed | 0 | 0 | 1 (4.5) |

| Never married/single | 1 (5.9) | 3 (33.3) | 3 (13.6) |

| Education | * | ||

| Less than high school graduate | 1 (5.9) | 0 | 0 |

| High school graduate | 2 (11.8) | 0 | 0 |

| Some college | 7 (41.2) | 1 (14.3) | 0 |

| College graduate | 7 (41.2) | 4 (57.1) | 2 (9.1) |

| Postgraduate | 0 | 2 (28.6) | 20 (90.9) |

| Employment | * | ||

| Not employed/retired | 7 (41.2) | 1 (14.3) | 0 |

| Employed part-time | 3 (17.6) | 2 (28.6) | 1 (4.5) |

| Employed full-time | 5 (29.4) | 2 (28.6) | 21 (95.5) |

| Disabled | 1 (5.9) | 0 | 0 |

| Homemaker | 1 (5.9) | 0 | 0 |

| Student | 0 | 2 (28.6) | 0 |

| Household income | * | ||

| More than $95,000 | 8 (47.1) | 2 (28.6) | 18 (81.8) |

| Between $75,000 and $94,999 | 1 (5.9) | 3 (13.6) | |

| Between $55,000 and $74,999 | 2 (11.8) | 2 (28.6) | 1 (4.5) |

| Between $35,000 and $54,999 | 2 (11.8) | 2 (28.6) | 0 |

| Less than $15,000 | 2 (11.8) | 1 (14.3) | 0 |

| Primary health insurance | * | ||

| Private health insurance | 9 (52.9) | 6 (85.7) | 21 (95.5) |

| Medicaid/Medicare | 7 (41.2) | 1 (14.3) | 1 (4.5) |

| Other | 1 (5.9) | 0 | 0 |

| Donation type | NA | NA | |

| Living | 2 (11.8) | ||

| Deceased | 15 (88.2) | ||

| Time since liver transplant | NA | NA | |

| <6 months | 1 (5.9) | ||

| 6–12 months | 4 (23.5) | ||

| 13–24 months | 4 (23.5) | ||

| >24 months | 7 (41.2) | ||

| Current heart disease risk factors | NA | NA | |

| Hypertension | 12 (70.6) | ||

| High cholesterol | 3 (17.6) | ||

| Overweight or obesity | 5 (29.4) | ||

| Chronic kidney disease | 3 (17.6) | ||

| Diabetes mellitus | 9 (52.9) | ||

| Current heart disease conditions | NA | NA | |

| Stroke or TIA | 1 (5.9) | ||

| Arrhythmia | 2 (11.8) | ||

| Thromboembolism | 1 (5.9) | ||

| Heart failure | 1 (5.9) | ||

| Coronary artery disease | 3 (17.6) | ||

| Peripheral vascular disease | 0 | ||

| Current or prior smoker | 3 (17.6) | NA | NA |

| Certification type | NA | NA | |

| M.D. | 13 (59.0) | ||

| R.N./B.S.N. | 3 (13.6) | ||

| A.P.P./P.A./N.P. | 2 (9.0) | ||

| Other† | 4 (18.2) | ||

| Provider primary specialty | NA | NA | |

| General cardiology | 3 (13.6) | ||

| Transplant cardiology | 1 (4.5) | ||

| Endocrinology | 2 (9.1) | ||

| Transplant hepatology | 5 (22.7) | ||

| General nephrology | 4 (18.2) | ||

| Transplant nephrology | 4 (18.2) | ||

| Transplant surgery | 2 (9.1) | ||

| Primary care | 3 (13.6) | ||

| Primary health care role | NA | NA | |

| Clinician | 15 (68.2) | ||

| Clinical researcher | 3 (13.6) | ||

| Basic or translational scientist | 1 (4.5) | ||

| Educator | 2 (9.1) | ||

| Other | 1 (4.5) | ||

| Years in practice | NA | NA | |

| <5 years | 7 (31.8) | ||

| 5–10 years | 4 (18.2) | ||

| 11–14 years | 0 | ||

| 15–20 years | 6 (27.3) | ||

| >20 years | 5 (22.7) | ||

| Unique LTRs seen in the past year | NA | NA | |

| <10 | 4 (18.2) | ||

| 10–50 | 11 (50.0) | ||

| 51–100 | 5 (22.7) | ||

| >100 | 2 (9.1) |

NOTE: Data are provided as n (%) or mean ± SD.

Missing data: percentages are based on n = 7.

Other certifications included social work, nutrition, pharmD, and physical therapy.

Among the caregivers who completed the survey (n = 8), 22.2% were men with a mean age of 59.0 (SD, 10.3) years, 62.5% self-identified as White, and 25.0% self-identified as Hispanic. The majority (62.5%) of caregivers were married or in a domestic partnership or civil union, and all had at least some college education or higher. The age, sex, and race/ethnicity of caregivers who did not respond to the invitation to participate are unknown.

Of the physicians initially recruited (n = 61), 13 participated (19.2% response rate). Physicians identified their multidisciplinary team members for recruitment. A total of 22 providers participated (mean age 43.2 ± 11.6 years, 40.9% men, 45.5% White, 18.2% Hispanic). Among health care provider nonrespondents or those who declined participation, 45.8% were men. The age and race/ethnicity of health care provider nonrespondents are unknown. The majority of providers were medical doctors (59.0%, n = 13), 9.0% (n = 2) were mid-level providers (eg, advanced practice nurse), 13.6% (n = 3) were nurses, and 18.2% (n = 4) were other professionals (social worker [n = 1], pharmacist [n = 1], nutritionist [n = 1], physical therapist [n = 1]) practicing in diverse medical specialties (Table 1). Most (68.2%) providers had more than 5 years of clinical experience, not including residency or fellowship training, and 81.8% had seen 10 or more individual LTRs in their clinical practice within the preceding year.

SURVEY-BASED PERCEPTIONS ABOUT CVD AND RELATED RISK FACTORS AFTER LT

Liver Transplant Recipients

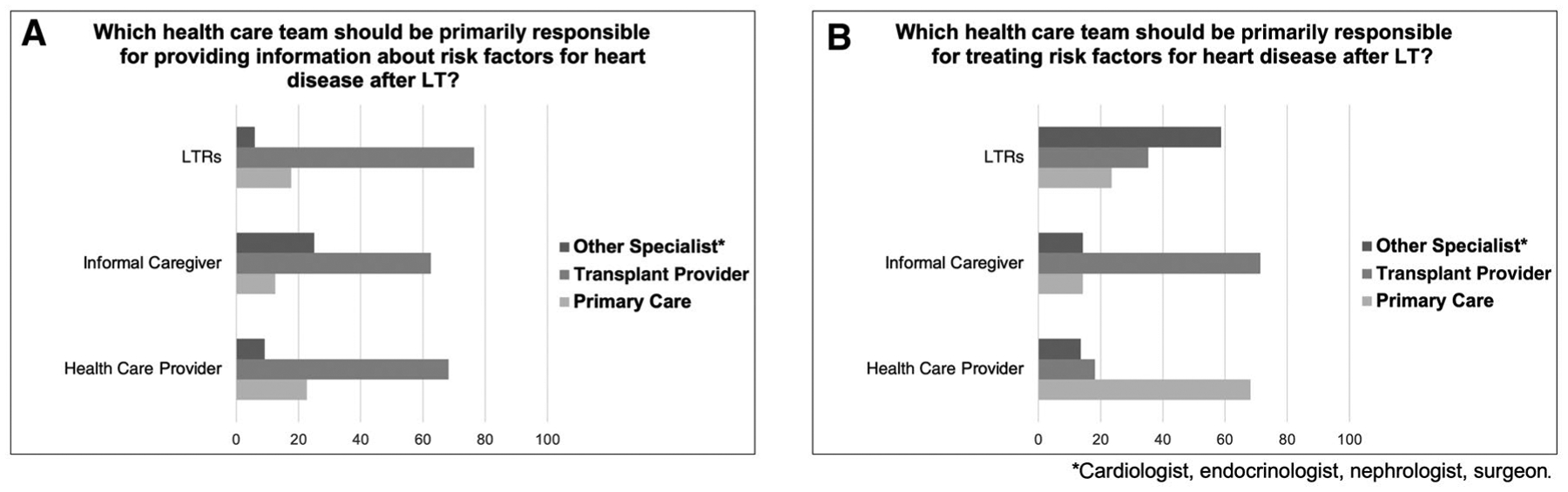

Most LTRs (94.1%) reported being unaware, prior to participation in the focus group, that CVD is a leading complication after LT (Table 2). All LTRs were confident (strongly agree and agree) in talking to their LT providers about CVD risk, but 11.8% were not confident (strongly disagree, disagree, and neutral) in talking to their non-LT providers about CVD risk. Most (76.4%) LTRs felt that their LT provider should be primarily responsible for providing information about CVD after LT, and 58.8% of LTRs felt that other specialty providers should provide the information; only 23.5% felt that primary care providers should provide CVD care after LT (Fig. 2).

TABLE 2.

LTR Knowledge, Attitudes, and Confidence to Take Action on CVD and Related Risk Factors After LT

| Responses (n = 17), % | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Survey Staement | Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Neutral | Agree | Strongly Agree | Mean ± SD |

| Perceived severity or susceptibility | ||||||

| Heart disease is a serious condition after liver transplantation | 5.9 | 0.0 | 5.9 | 35.3 | 52.9 | 4.3 ± 1.0 |

| Liver transplant recipients have a higher chance of developing heart disease than the general population | 5.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 35.3 | 58.8 | 4.4 ± 0.97 |

| My chance of developing heart disease is important to discuss with my nontransplant providers | 5.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 35.3 | 58.8 | 4.4 ± 0.97 |

| My chance of developing heart disease is important to discuss with my liver transplant providers | 5.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 5.9 | 88.2 | 4.7 ± 0.96 |

| Self-efficacy | ||||||

| I am confident talking about heart disease risk factors with my nontransplant providers | 5.9 | 5.9 | 0.0 | 23.5 | 64.7 | 4.1 ± 0.85 |

| I am confident talking about heart disease risk factors with my liver transplant providers | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 35.3 | 64.7 | 4.6 ± 0.48 |

| I am confident in my ability to check my blood pressure | 0.0 | 0.0 | 11.8 | 29.4 | 58.8 | 4.5 ± 0.69 |

| I am confident in my ability to maintain a food diary | 11.8 | 0.0 | 23.5 | 41.2 | 23.5 | 3.6 ± 1.2 |

| I am confident in my ability to eat a healthy diet* | 6.3 | 6.3 | 18.8 | 31.3 | 37.5 | 3.9 ± 1.2 |

| I am confident in my ability to get physical activity at least 30 minutes per day on most days of the week | 5.9 | 0.0 | 23.5 | 35.3 | 35.3 | 3.9 ± 1.1 |

| I am confident in my ability to eat a diet low in salt (sodium) | 5.9 | 5.9 | 0.0 | 23.5 | 64.7 | 4.4 ± 1.1 |

| I am confident in my ability to not smoke | 5.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 11.8 | 82.4 | 4.6 ± 0.97 |

| I am confident in my ability to maintain a healthy body weight† | 0.0 | 6.7 | 20.0 | 26.7 | 46.7 | 4.1 ± 0.96 |

| I am confident in my ability to schedule clinic appointments with multiple health care providers | 5.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 23.5 | 70.6 | 4.5 ± 0.98 |

| I am confident in my ability to attend clinic appointments with multiple health care providers* | 6.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 18.8 | 75.0 | 4.6 ± 1.0 |

| Confidence in health care providers | ||||||

| My transplant doctors seem informed and up to date about the heart disease risk factor care I receive from nontransplant doctors* | 0.0 | 0.0 | 31.3 | 12.5 | 56.3 | 4.3 ± 0.90 |

| My nontransplant doctors seem informed and up to date about the heart disease risk factor care I receive from nontransplant doctors* | 6.3 | 6.3 | 37.5 | 6.3 | 43.8 | 3.8 ± 1.3 |

One participant skipped this question. Percentages are based on n = 16.

Two participants skipped this question. Percentages are based on n = 15.

Fig. 2.

Comparison of LTR, caregiver, and provider attitudes on the role and responsibility of the multidisciplinary health care team in (A) communication and (B) delivery of care for CVD risk factors after LT.

In terms of self-efficacy for performing preventive actions to reduce CVD risk, most LTRs (94.2%) were confident in their ability to not smoke, eat a low-sodium diet, and check their blood pressure. In contrast, 35.3% were not confident in their ability to maintain a food diary, eat a healthy diet, get at least 30 minutes of exercise a day, or maintain a healthy body weight.

Caregivers

Most caregivers (87.5%) also reported being unaware, prior to participating in the focus group, that CVD is a leading complication after LT (Table 3). All caregivers were confident talking with LT providers about CVD care for LTRs, although 12.5% were not confident talking to non-LT providers. Similar to LTRs, the majority of caregivers indicated that LT providers and other subspecialty providers (eg, cardiologist, nephrologist) should be primarily responsible for providing CVD care after LT. Only 14.3% of caregivers felt that primary care providers should be responsible for communication about CVD risk or for providing CVD care (Fig. 2).

TABLE 3.

Informal Caregiver Knowledge, Attitudes, and Confidence to Take Action on CVD and Related Risk Factors after LT

| Responses (n = 8), % | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Survey Staement | Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Neutral | Agree | Strongly Agree | Mean ± SD |

| Perceived severity or susceptibility | ||||||

| Heart disease is a serious condition after liver transplantation | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 12.5 | 87.5 | 4.9 ± 0.33 |

| Liver transplant recipients have a higher chance of developing heart disease than the general population | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 12.5 | 87.5 | 4.9 ± 0.33 |

| The liver transplant recipient that I care for chance of developing heart disease is important to discuss with their nontransplant providers | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 100.0 | 5.0 ± 0.0 |

| The liver transplant recipient that I care for chance of developing heart disease is important to discuss with their liver transplant providers | 0.0 | .00 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 100.0 | 5.0 ± 0.0 |

| Self-efficacy | ||||||

| I am confident talking about heart disease risk factors with my liver transplant recipient’s nontransplant providers | 0.0 | 0.0 | 12.5 | 12.5 | 75.0 | 4.6 ± 0.70 |

| I am confident talking about heart disease risk factors with my liver transplant recipient’s liver transplant providers | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 100.0 | 5.0 ± 0.0 |

| I am confident in my ability to help the liver transplant recipient that I care for check their blood pressure. | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 100.0 | 5.0 ± 0.0 |

| I am confident in my ability to help the liver transplant recipient that I care for check his or her blood sugar | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 12.5 | 87.5 | 4.9 ± 0.33 |

| I am confident in my ability to help the liver transplant recipient that I care for maintain a food diary | 0.0 | 0.0 | 12.5 | 12.5 | 75.0 | 4.6 ± 0.70 |

| I am confident in my ability to help the liver transplant recipient that I care for eat a healthy diet | 12.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 12.5 | 75.0 | 4.4 ± 1.3 |

| I am confident in my ability to help the liver transplant recipient that I care for not smoke or stop smoking* | 0.0 | 0.0 | 14.3 | 14.3 | 71.4 | 4.6 ± 0.73 |

| I am confident in my ability to help the liver transplant recipient that I care for get regular physical activity (regular = least 30 minutes per day on most days of the week)* | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 14.3 | 85.7 | 4.9 ± 0.35 |

| I am confident in my ability to help the liver transplant recipient that I care for eat a diet low in salt (sodium)* | 0.0 | 0.0 | 14.3 | 14.3 | 71.4 | 4.6 ± 0.73 |

| I am confident in my ability to help the liver transplant recipient that I care for maintain a healthy body weight* | 0.0 | 0.0 | 14.3 | 28.6 | 57.1 | 4.4 ± 0.73 |

| I am confident in my ability to help the liver transplant recipient that I care for schedule clinic appointments with multiple health care providers* | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 100.0 | 5.0 ± 0.0 |

| I am confident in my ability to help the liver transplant recipient that I care for attend clinic appointments with multiple health care providers* | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 100.0 | 5.0 ± 0.0 |

| Confidence in health care providers | ||||||

| The transplant doctors seem informed and up to date about the heart disease risk factor care that the liver transplant recipient that I care for receives from nontransplant doctors* | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 100.0 | 5.0 ± 0.0 |

| The nontransplant doctors seem informed and up to date about the heart disease risk factor care that the liver transplant recipient that I care for receives from transplant doctors* | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 100.0 | 5.0 ± 0.0 |

One participant skipped this question. Percentages are based on n = 7.

In terms of assisting the LTRs in performing actions to reduce CVD risk, all caregivers reported feeling confident in their ability to help the LTR with scheduling and attending clinic appointments with multiple providers, checking blood pressure and blood sugar, and helping the LTR get regular physical activity. On the other hand, 12.5% of caregivers were not confident in their ability to help the LTR maintain a food diary or eat a healthy diet, and 14.3% were not confident in their ability to help the LTR stop smoking, eat a low-sodium diet, or maintain a healthy body weight.

Providers

Of the providers, 36.3% reported not knowing, prior to taking part in the focus group, that CVD risk is elevated in LTRs (Table 4). Almost all providers agreed (95.5%) that CVD risk is an important topic to discuss with LTRs, although 45.4% were not confident in their ability to talk with LTRs about CVD risk. Only 13.6% of providers thought that CVD risk factors were well controlled in the LTRs under their care, whereas 36.3% were confident in their ability to provide CVD care to LTRs.

TABLE 4.

Health Care Provider Knowledge, Attitudes, and Confidence to Take Action on CVD and Related Risk Factors in LTRS

| Responses (n = 22), % | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Survey Staement | Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Neutral | Agree | Strongly Agree | Mean ± SD |

| Perceived severity or susceptibility | ||||||

| Cardiovascular disease is a serious complication in liver transplant recipients | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 27.3 | 72.7 | 4.7 ± 0.45 |

| Liver transplant recipients have a higher chance of developing cardiovascular disease than the general population | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 31.8 | 68.2 | 4.7 ± 0.47 |

| Cardiovascular disease risk is an important topic to discuss with the liver transplant recipients under my care | 0.0 | 0.0 | 4.5 | 27.3 | 68.2 | 4.6 ± 0.57 |

| Cardiovascular disease risk factors are well controlled in the liver transplant recipients under my care* | 4.8 | 28.6 | 52.4 | 9.5 | 4.8 | 2.8 ± 0.85 |

| Self-efficacy | ||||||

| I am confident talking with liver transplant recipients about cardiovascular disease risk | 0.0 | 13.6 | 31.8 | 40.9 | 13.6 | 3.5 ± 0.89 |

| I am confident managing cardiovascular disease risk factors in liver transplant recipients | 0.0 | 13.6 | 50.0 | 31.8 | 4.5 | 3.3 ± 0.75 |

| I am confident managing blood pressure in liver transplant recipients | 0.0 | 13.6 | 0.0 | 54.5 | 31.8 | 4.0 ± 0.93 |

| I am confident managing lipids in liver transplant recipients | 0.0 | 27.3 | 13.6 | 40.9 | 18.2 | 3.5 ± 1.1 |

| I am confident managing blood glucose in liver transplant recipients | 0.0 | 45.5 | 27.3 | 22.7 | 4.5 | 2.9 ± 0.91 |

| I am confident managing renal dysfunction in liver transplant recipients | 0.0 | 22.7 | 18.2 | 21.8 | 22.7 | 3.6 ± 1.1 |

| I am confident managing smoking in liver transplant recipients | 0.0 | 27.3 | 27.3 | 31.8 | 13.6 | 3.3 ± 1.0 |

| I am confident managing weight in liver transplant recipients | 0.0 | 18.2 | 40.9 | 36.4 | 4.5 | 3.3 ± 0.81 |

| I am confident coordinating cardiovascular disease care risk factor care in liver transplant recipients | 0.0 | 50.0 | 13.6 | 31.8 | 4.5 | 2.9 ± 1.0 |

| Care communication | ||||||

| I regularly communicate with health care providers within my institution on changes to cardiovascular disease risk factor care on the liver transplant recipients under my care | 4.5 | 18.2 | 31.8 | 20.9 | 4.5 | 3.2 ± 0.95 |

| I regularly communicate with health care providers external to my institution on changes to cardiovascular disease risk factor care on the liver transplant recipients under my care | 9.1 | 50.0 | 22.7 | 13.6 | 4.5 | 2.5 ± 0.99 |

| I receive accurate communication from providers within my institution on changes to cardiovascular disease risk factor care on the liver transplant recipients under my care* | 0.0 | 38.1 | 33.3 | 19.0 | 9.5 | 3.0 ± 0.98 |

| I receive accurate communication from providers external to my institution on changes to cardiovascular disease risk factor care on the liver transplant recipients under my care | 18.2 | 54.5 | 18.2 | 4.5 | 4.5 | 2.2 ± 0.95 |

One participant skipped this question. Percentages are based on n = 21.

Most providers (86.3%) were confident in their ability to manage blood pressure and lipids in LTRs, but a minority (<45%) were confident in their ability to manage smoking, renal dysfunction, weight, and blood glucose. Only 36.3% of providers were confident in their ability to coordinate CVD care in LTRs, and only 25.4% reported communicating regularly with other providers within their institution about changes to the CVD care of LTRs, and even fewer (18.2%) reported communicating regularly with providers outside their institution. Furthermore, 28.5% of providers reported receiving communications from providers within their institution about changes to CVD care of LTRs under their care, and only 9.0% reported receiving similar information from providers outside their institution (Table 4).

FOCUS GROUP THEMES

The four most common themes across all focus groups were (1) lack of awareness of CVD risk after LT, (2) lack of confidence in ability to provide CVD care to LTRs, (3) reluctance to provide CVD care without LT provider review, and (4) complexity of communication with the multidisciplinary LTR care team about LTRs CVD care (Table 5).

TABLE 5.

Themes, Subthemes, and Illustrative Quotations

| Theme and Subtheme | Example Quotations |

|---|---|

| Theme 1: lack of awareness of CVD risk after LT CVD is not a main health concern after LT The liver is the central concern Lack of knowledge about specific CVD risk factors No knowledge of level of CVD risk after LT Imminent health concerns take precedence |

They wouldn’t have given me a liver if my heart was bad, and I’ve never given it another thought. (LTR L15) |

| I have a lot of issues that could be heart-related, but I’m so focused [on] just the liver that I don’t need another problem. Going to a cardiologist is like taking my car to a mechanic and saying, “Is there anything wrong with this car?” They’re going to find something, and I have enough problems. (LTR L09) | |

| “I focus on my liver as being the cause why I’m not the same person I was eight years ago, why I’m fatigued, why my memory doesn’t work well, why a lot of other systems are not working. Therefore, I might get winded if I go up a flight of stairs. It all could be heart-related.” (LTR L01) | |

| I don’t think my husband is at risk for heart disease. He has diabetes and high blood pressure, but he takes medication for those so now that’s fixed. (caregiver C02) | |

| I don’t think my transplant patients perceive that they are at increased risk for cardiovascular disease. They are very focused on their transplant and I think sometimes they discount other things. (primary care provider P01) | |

| I think it’s more on educating us of there is a lot of risk of cardiac problems after liver transplant. (cardiology provider P03) | |

| I think we’re all guilty of not prioritizing blood pressure control as early on. I mean, we say it needs to be better managed, but we’re—I think we think of the other three or four things that in our minds take precedence and maybe it shouldn’t. (transplant provider P18) | |

| I don’t view that the liver transplant per se is that much substantially higher risk for cardiovascular disease, at least in my understanding. (endocrinology provider P05) | |

| It’s usually catastrophic and everyone’s working for those people because it’s catastrophic. It’s the in-betweens—transplants check their boxes. This person’s doing great because they’re on their immunosuppression, but they are not taking care of themselves. (endocrinology provider P06) | |

| Theme 2: lack of confidence in ability to provide proper CVD care to LTRs Barriers to individual CVD care Lack of recognition of suboptimal CVD risk factors Medication concerns |

You end up being the new primary care doctor often, and that becomes sort of a lot of juggling involved there especially when you talk about other comorbidities and cardiovascular disease. I’ve always struggled with that. (transplant provider P10) |

| Certainly, the glucose needs to be followed carefully. I don’t know how well that’s done. I suspect that even the transplant doctors don’t look that careful. Somebody has a glucose of 130—that’s normal. It’s not. That may be new diabetes, so I think that that goes unrecognized. Is new onset diabetes a risk factor for cardiovascular disease? The thought is that probably is. Nonetheless, I don’t know that it’s recognizable by either the primary care person that may be following them or even the transplant person who’s following them. They could clearly be doing better. (endocrinology provider P06) | |

| I think that’s probably where the lack of knowledge comes into play: is a statin good, is it bad? What are blood pressure goals? Do I need to be the one moving their immunosuppression because their level was too high? So I think clear patient-specific goals. (nephrology provider P11) | |

| Theme 3: reluctance to provide CVD care to LTRs without transplant provider review Impact of transplant clinician’s advice Unclear identity of who is the primary provider Patient distrust of providers other than transplant provider |

My wife made the phone call so, I don’t know what was actually said. The end result was that it’s something that I should see my primary care physician about. But, the first thing the emergency room doctor said was, “Call the transplant center.” (LTR L11) |

| I think it’s different when a transplant doctor or a hepatologist that deals with transplant tells you something compared to a doctor, even my endocrinologist or somebody else. You tend to listen and it catches your ear more when it’s coming from them, because you know they see it. (LTR L16) | |

| I know before I even call that this is not a liver clinic thing. The gout was not a liver clinic thing, but we called here first. And the person I spoke with was so nice and helpful and said, “Go with your primary physician.” And I said “That’s what I thought but I just wanted to check.” And they always—whoever I’m talking to, when it comes like that, they say “That’s okay. Better safe than sorry. And it makes me feel, like, “Oh, they didn’t hang up, like, Oh my God. They’re going to call me” Then I feel free to call and I feel like I’ll have that for the rest of his life. And I’m really grateful for that, that there’s acceptance and care. (caregiver C08) | |

| Maybe it’s because people feel like transplant’s going to take care of everything. (primary care provider P12) | |

| They feel like their primary doctor—not primary care doctor—primary doctor is their hepatologist, you’ll hear them say if you want to make any change, well let me talk to X, Y, and Z before I do that. It’s not anyone’s fault but it’s a trust issue in terms of their hepatologist is their primary doctor and without interacting with them or us talking to them—make sure you talk to them before—have you talked to them before you started this? Like do they know that you’re starting this? I think that becomes a little bit of a barrier. (nephrology provider P13) | |

| You know what’s funny? I feel like the patients—most of these people have PCPs elsewhere. The impression that the patients have is, “If I see my PCP they’ll mess something up for the first year, so I shouldn’t see them.” That’s the impression that they have about their PCPs in the first year. (primary care provider P17) | |

| I wonder what primary care feels comfortable in a transplant patient, right? This is more what I’ve heard from patients rather than the actual doctors. A patient will be like, “My primary doctor said I should just ask you about this and they probably say that to you too when they see you.” So the person who’s supposed to be coordinator and see them the most often no longer is, but who is that person, right? (nephrology provider P14) | |

| So, there are primary care doctors that are very comfortable managing hypertension, glycemic control, lipids in the post-transplant patients, and then others that don’t do anything and they want us to do everything. The hard part is knowing who those people are, right? (transplant provider P09) | |

| Theme 4: complexity of communication with the multidisciplinary LTR care team about CVD care Time constraints Unclear care team roles and responsibilities Need for a quarterback Leveraging ancillary providers |

And it takes a long time to close that loop. It just takes a long, long time to communicate with the primary care doctor. (transplant provider P20) |

| I’m going to have you follow up with your PCP now for this, and then we know that we can take that over and start managing—following closely. I wonder how much we think that they’re doing and how much they think we’re doing, and if it’s just getting missed. (endocrine provider P06) | |

| They can communicate better with my primary care doctor and I don’t want them doing something down there that I know they haven’t contacted up here. Like I told you before, I worked too hard to get this. (LTR 013) | |

| There’s so many doctors that come in, I don’t know who is doing what. (LTR 004) | |

| We need a point person that’s in charge that is our go-to person because I don’t think it’s realistic for each of us to, in a uniform way, do the right thing and optimize CVD care. It’s just too much to do. (transplant provider P20) | |

| There has to be one captain. There cannot be like a thousand captains and I change the potassium drops, then I give nitrates, potassium drops and then something happens to the liver. I think that comprehensive care should be another field of post-transplant care. (nephrology provider P21) | |

| It would be nice to have that pass-off between nurse to nurse as if they didn’t have that cardiologist. We need to be more proactive instead of reactive, in terms of these risk factors that are there. (cardiology provider P18) |

Lack of Awareness of CVD Risk After LT

Most participants indicated that CVD is not considered to be a major health concern by LTRs, caregivers, or providers. LTRs stressed that, prior to transplant, they are primarily concerned with staying alive and, after transplant, they have more acute health concerns, such as liver graft rejection.

When I had to go through all the tests that you have to go through to get a liver, I thought, “Okay, my heart—because they wouldn’t have given me a liver if my heart was bad,” and I’ve never given it another thought. (LTR L02)

You’re not worried about the heart at that point, you’re worried about living. (LTR L07)

Providers indicated that, with limited time to spend with each patient, there are other important health concerns that providers are more likely to monitor.

I mean, I guess, yeah, the liver graft is number one and the—I mean, I always rank them in my impression and plan on sort of order of importance by liver graft, immunosuppression, their prophylaxis, antibacterial or antifungal or antiviral … And then the other things like cardiovascular disease, renal disease—those come lower down. (transplant provider P05)

Lack of Confidence in Ability to Provide CVD Care to LTRs

Both caregivers and providers expressed a lack of confidence in their abilities to provide care to LTRs. In particular, caregivers stressed the hardships associated with becoming a full-time caregiver to an LTR and feeling inadequately prepared to execute this role.

That was the most frightening experience, I think. From saying ‘You’re discharged.’ (caregiver C06)

Non-LT specialty providers expressed reticence to manage the CVD care of LTRs because of the complexity of LT.

I think nontransplant doctors are scared of transplant drugs, as they should be. These are bad drugs. We should be scared of them. (endocrinology provider P06)

Reluctance to Provide CVD Care to LTRs Without LT Provider Review

LTRs considered that LT providers were the key providers from whom information about complications or health conditions, including CVD, after LT should be received (Fig. 2). Similarly, all non-LT providers also considered LT providers as the key providers to deliver information to LTRs about any complications or health conditions after LT.

LTRs perceived the LT providers as the key providers for all care after LT, including provision of information about CVD risk factors.

Dr. X told me already, “Next time I see you, I need 10 pounds lighter.” And I’ve got a watch now that counts how many steps I take, so I do 10,000 a day and I’m working on it. It comes through with more emphasis from the liver doctor than my primary. (LTR L12)

However, the LT providers acknowledged that appropriate CVD care is not always provided and that they sometimes rely on LTRs’ primary care providers.

So, there are primary care doctors that are very comfortable managing hypertension, glycemic control, lipids in the post-transplant patients, and then others that don’t do anything and they want us to do everything. The hard part is knowing who those people are, right? (transplant provider P09)

All LTRs indicated that they believed that all of their health care after LT must “go through” the LT providers. However, LTRs and providers also expressed barriers to access to the LT providers for care.

I’ve gone to the emergency room before where the doctor in the emergency room wants to give me Advil and I’m like, “I’m not taking Advil.” And he’s telling me, “I’m the doctor.” I said, “You call Dr. X and do what he says,” “Okay, okay.” (LTR L02)

Complexity of Communication With the Multidisciplinary LTR Care Team About CVD Care

Most LTRs have a large multidisciplinary (eg, LT providers, primary care) care team, rendering communication between team members difficult. LTRs reported being unsure who to contact when complications arise, feeling frustrated, and having to communicate with each of the care team members and be their own advocate.

I know before I even call that this is not a liver clinic thing. The gout was not a liver clinic thing, but we called here first. And the person I spoke with was so nice and helpful … And I’m really grateful for that, that there’s acceptance and care. (caregiver C08)

A lot of times that blood work never does make it to my primary care doctor. I have to follow up with it even though I handed them the card; I watched them fill it out that they’re going to fax it. It may be three times out of ten that they’ll get it there. (LTR L14)

Providers also perceived the complexity of LTRs’ care team as a barrier to CVD care. They indicated that they are not always sure about which member of the care team is providing care for the different aspects of an LTR’s health. Time constraints, unclear care team roles, and unclear responsibility for each of the different aspects of CVD care were reported as barriers to LTR CVD care.

Who is actually managing the health of solid organ transplants, I don’t know who. (cardiology provider P13)

“I’m going to have you follow up with your PCP now for this, and then we know that we can take that over and start managing—following closely.” I wonder how much we think that they’re doing and how much they think we’re doing, and if it’s just getting missed. (endocrine provider P22)

RECOMMENDATIONS AND POTENTIAL SOLUTIONS

Participants provided several recommendations that can be summarized into the following 5 areas: (1) improved education for LTRs and caregivers about CVD risk factors, (2) electronic health record (EHR) alerts for providers, (3) clearly defined CVD care provider roles, (4) increased use of the transplant pharmacist, and (5) multidisciplinary provider meetings to discuss care plans for LTRs.

Discussion

This article represents an account of the perspectives of LTRs, informal caregivers, and providers about their awareness of increased CVD risks after LT, barriers to CVD care after LT, and potential recommendations to address the identified barriers. Key themes were lack of awareness of increased CVD risk after LT in LTRs and caregivers and lack of confidence among non-LT providers, without review by an LT provider, in their ability to provide appropriate CVD care to LTRs. Furthermore, all groups identified the complexity of communications about LTRs’ CVD care across the multidisciplinary care team as highly problematic.

Our findings confirm that most LTRs and caregivers, and some providers in our sample, are largely unaware of the increased CVD risk after LT. This lack of awareness likely contributes to suboptimal seeking and provision of care for blood pressure, weight management, glucose monitoring, physical exercise, and diet assessment.

Low self-efficacy or lack of confidence in providing appropriate CVD care to LTRs was a common theme among both caregivers and non-LT providers. Considering that self-efficacy is a significant mediator of positive health outcomes, low self-efficacy is highly problematic for CVD outcomes after LT.(15,16) The need to focus on 1 chronic condition at a time is common among patients with multimorbidity.(17) From a health care delivery perspective, there is a need to implement processes to improve guideline-concordant care across multiple chronic conditions, particularly those associated with CVD, after LT.

Most LTRs, caregivers, and non-LT providers indicated that all LTRs’ health care needs should be reviewed by an LT provider. However, they also reported that this review creates significant barriers to timely care. This failure in the systems and processes of LTR care appears to affect the quality and timeliness of appropriate CVD care substantively. Furthermore, the capacity to provide longterm care for LTRs is an issue due to the number of LTRs increasing in the United States with prolonged patient and graft survival, and aging of the LTR population who now more closely resemble a general chronic disease population.(18,19) LT providers indicated that they are no longer able to provide adequate CVD care to all LTRs because of time constraints and competing health priorities (ie, immunosuppression management). Personalized care planning, used often with medically complex patients, may be a potential system-based solution to improving CVD outcomes in LTRs.(20)

Finally, the multidisciplinary nature and complexity of the LTR care teams were reported as significant barriers to appropriate CVD care. LTRs noted that, because of their complex health care needs, they usually have multiple providers, but that they themselves do not know the role of each provider. All providers also indicated that they are unsure who to contact regarding CVD care for LTRs, as each patient has multiple providers. Furthermore, LTRs expressed that they often felt that they had to be their own advocate, making sure that their medical records and health information were shared across their providers. Although not unique to CVD care, this system-level failure points to the need for a redesign of the systems and processes of CVD care and potentially of other chronic disease management in LTRs.(19)

RECOMMENDATIONS AND POTENTIAL SOLUTIONS

LTRs, caregivers, and providers proposed several recommendations to address the identified barriers to CVD care in LTRs. First, making LTRs and caregivers aware of the increased CVD risk is essential. LT providers are likely to be most effective in informing patients about CVD risk after LT and in encouraging LTRs to seek preventive CVD care from non-LT providers.

All non-LT providers reported that their major concerns in providing CVD care for LTRs were related to medication adverse effects and interactions with immunosuppression. A potential solution is to provide easy access for non-LT providers to a consultation with an LT pharmacist. In addition, after LTRs are discharged, LT pharmacists could remain involved in monitoring LTRs’ medication regimens to assist with the detection of any interactions, address adverse effects, and encourage adherence to guideline-directed medical therapy.(21)

To increase non-LT provider awareness about the high CVD risk in LTRs, an EHR alert could be developed and linked to order sets and clinical algorithms for managing CVD risk factors (eg, thresholds and initial medication choice for elevated blood pressure, choice of statin medication for CVD prevention) in the LTR.

Training and education about CVD care after LT for caregivers and non-LT providers could be a potential solution to enhance caregivers’ and non-LT providers’ self-efficacy in providing CVD care. Caregivers who have received additional training on providing at-home care have been shown to have a significant increase in reported self-efficacy when compared with caregivers who did not receive additional training.(22) High ratings of self-efficacy have been shown to support better clinical outcomes for those being cared for.(23) Furthermore, non-LT providers’ self-efficacy could be addressed by developing standardized guidance to effectively communicate CVD risk factors to LTRs and caregivers as communication skills training has been shown to increase long-term self-efficacy among providers.(24) With the increased number of LTRs and increased survival of LTRs, expanding the number and role of LT coordinators as patient navigators is another potential solution. They could offer education about CVD risk and support CVD care by decreasing the need for transplant provider review by the LT providers before making CVD care decisions.

The complexity of LTR care teams was perceived as a major barrier to CVD care in LTRs and is similar to the complexity of oncology patients’ care teams. Recent research on the effectiveness of complex care teams in oncology has shown that multidisciplinary meetings can lead to improved clinical decision making, more coordinated patient care, and overall improved treatment for patients.(25) When nurses and coordinators are perceived as being as important within the care team as physicians, the teams are regarded as more effective, with patients’ preferences and comorbidities more likely to be considered.(25) Thus, a potential solution might be to have regular team meetings of the LTR care team, including outpatient nurses and LT coordinators who communicate often with LTRs and caregivers, focusing the facilitation of multidisciplinary input to assure effective communication about LTR care plans, including CVD care, to all team members. In the new era of telemedicine, such virtual team meetings may be more feasible and acceptable than ever before.

Additional solutions include (1) providing LTRs and caregivers with a document that provides the names and roles of all the LTR’s care team members; (2) educating, from the very beginning of the LT process, LTRs and caregivers to first contact the LT coordinator for any concerns; (3) providing LTR care team members with contact information for the LT coordinator and pharmacist; and (4) including in each LTR’s EHR a summary of appropriate CVD care with links to clinical practice guidance and clinical algorithms.

LIMITATIONS

Several limitations to the study must be noted. All participants were recruited from a single LT network within a single health care system, which limits generalizability of the findings to other LT networks and health care systems. Selection bias is also possible as participants were not specifically sampled based on sex, age, race/ethnicity, or socioeconomic factors. Future work should assess the generalizability of the results across diverse settings with a focus on purposive sampling to examine differences in perspectives by sex and race/ethnicity. Participant recall bias may also be a limitation, although all LTRs had undergone an LT within the previous 3 years and all providers had cared for at least 5 LTRs within the previous year.

CONCLUSION

This study is the first to identify perceived barriers by LTRs and their caregivers and providers to CVD care for LTRs. Application of a user-centered design of the proposed recommendations and solutions, with rapid-cycle iterative testing and use of applied implementation principles, are needed to develop and implement effective solutions before further evaluation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments:

The authors thank Dario Ciacura, Arighno Das, M.D., and Patrick Stewart, M.D., for their assistance in recruitment for the focus group sessions. The authors thank all of the liver transplant recipients, caregivers, and health care providers for dedicating their time to this study. We also thank Tasmeen Hussain, M.D., and Blessing Aghaulor, M.D., for their assistance with analysis of the focus group transcripts.

This work was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute at the National Institutes of Health to Lisa B. VanWagner (Grant K23 HL136891).

Lisa B. VanWagner consults and has grants with W. L. Gore & Associates.

Abbreviations:

- APP

advanced practice provider

- CVD

cardiovascular disease

- EHR

electronic health record

- LT

liver transplantation

- LTR

liver transplant recipient

- MD

medical doctor

- NA

not applicable

- NMEDW

Northwestern Medicine Enterprise Data Warehouse

- NP

nurse practitioner

- PA

physician assistant

- RN

registered nurse

- SD

standard deviation

- TIA

transient ischemic attack

Footnotes

Additional supporting information may be found in the online version of this article.

REFERENCES

- 1).Habka D, Mann D, Landes R, Soto-Gutierrez A. Future economics of liver transplantation: a 20-year cost modeling forecast and the prospect of bioengineering autologous liver grafts. PLoS One 2015;10:e0131764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2).Albeldawi M, Aggarwal A, Madhwal S, Cywinski J, Lopez R, Eghtesad B, et al. Cumulative risk of cardiovascular events after orthotopic liver transplantation. Liver Transpl 2012;18:370–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3).Fussner LA, Heimbach JK, Fan C, Dierkhising R, Coss E, Leise MD, et al. Cardiovascular disease after liver transplantation: when, what, and who is at risk. Liver Transpl 2015;21:889–896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4).VanWagner LB, Lapin B, Levitsky J, Wilkins JT, Abecassis MM, Skaro AI, et al. High early cardiovascular mortality after liver transplantation. Liver Transpl 2014;20:1306–1316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5).VanWagner LB, Serper M, Kang R, Levitsky J, Hohmann S, Abecassis M, et al. Factors associated with major adverse cardiovascular events after liver transplantation among a national sample. Am J Transplant 2016;16:2684–2694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6).Bianchi G, Marchesini G, Marzocchi R, Pinna AD, Zoli M. Metabolic syndrome in liver transplantation: relation to etiology and immunosuppression. Liver Transpl 2008;14:1648–1654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7).Laish I, Braun M, Mor E, Sulkes J, Harif Y, Ben AZ. Metabolic syndrome in liver transplant recipients: prevalence, risk factors, and association with cardiovascular events. Liver Transpl 2011;17:15–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8).Pageaux G-P, Faure S, Bouyabrine H, Bismuth M, Assenat E. Long-term outcomes of liver transplantation: diabetes mellitus. Liver Transpl 2009;15(suppl 2):S79–S82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9).Wong RJ, Singal AK. Trends in liver disease etiology among adults awaiting liver transplantation in the United States, 2014–2019. JAMA Netw Open 2020;3:e1920294–e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10).Watt KD. Keys to long-term care of the liver transplant recipient. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015;12:639–648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11).VanWagner LB, Holl JL, Montag S, Gregory D, Connolly S, Kosirog M, et al. Blood pressure control according to clinical practice guidelines is associated with decreased mortality and cardiovascular events among liver transplant recipients. Am J Transplant 2020;20:797–807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12).Patel SS, Rodriguez VA, Siddiqui MB, Faridnia M, Lin FP, Chandrakumaran A, et al. The impact of coronary artery disease and statins on survival after liver transplantation. Liver Transpl 2019;25:1514–1523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13).Janz NK, Becker MH. The health belief model: a decade later. Health Educ Q 1984;11:1–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14).Kim WR, Lake JR, Smith JM, Schladt DP, Skeans MA, Noreen SM, et al. OPTN/SRTR 2017 Annual data report: Liver. Am J Transplant 2019;19(Suppl 2):184–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15).Mak WWS, Law RW, Woo J, Cheung FM, Lee D. Social support and psychological adjustment to SARS: the mediating role of self-care self-efficacy. Psychol Health 2009;24:161–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16).Riegel B, Dickson VV, Kuhn L, Page K, Worrall-Carter L. Gender-specific barriers and facilitators to heart failure self-care: a mixed methods study. Int J Nurs Stud 2010;47:888–895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17).Smith SM, O’Dowd T. Chronic diseases: what happens when they come in multiples? Br J Gen Pract 2007;57:268–270. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18).Durand F, Levitsky J, Cauchy F, Gilgenkrantz H, Soubrane O, Francoz C. Age and liver transplantation. J Hepatol 2019;70:745–758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19).Serper M, Asrani SK. Liver transplantation and chronic disease management: moving beyond patient and graft survival. Am J Transplant 2020;20:629–630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20).Bolton RE, Bokhour BG, Hogan TP, Luger TM, Ruben M, Fix GM. Integrating personalized care planning into primary care: a multiple-case study of early adopting patient-centered medical homes. J Gen Intern Med 2020;35:428–436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21).Milfred-LaForest SK, Gee JA, Pugacz AM, Pina IL, Hoover DM, Wenzell RC, et al. Heart failure transitions of care: a pharmacist-led post-discharge pilot experience. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 2017;60:249–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22).Hendrix CC, Landerman R, Abernethy AP. Effects of an individualized caregiver training intervention on self-efficacy of cancer caregivers. West J Nurs Res 2013;35:590–610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23).Nicholson O, Mellins C, Dolezal C, Brackis-Cott E, Abrams EJ. HIV treatment-related knowledge and self-efficacy among caregivers of HIV-infected children. Patient Educ Couns 2006;61:405–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24).Gulbrandsen P, Jensen BF, Finset A, Blanch-Hartigan D. Long-term effect of communication training on the relationship between physicians’ self-efficacy and performance. Patient Educ Couns 2013;91:180–185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25).Soukup T, Lamb BW, Arora S, Darzi A, Sevdalis N, Green JS. Successful strategies in implementing a multidisciplinary team working in the care of patients with cancer: an overview and synthesis of the available literature. J Multidiscip Healthc 2018;11:49–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.