Abstract

Introduction

Management of neuropathic cancer pain (NCP) refractory to regular opioids remains an important challenge. The efficacy of pregabalin for NCP except chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy (CIPN) has already been confirmed in two randomised controlled trials (RCTs) compared with placebo. Duloxetine offers the potential of analgesia in opioid refractory NCP. However, there are no RCT of duloxetine for the management of opioid-refractory NCP as a first line treatment. Both classes of drugs have the potential to reduce NCP, but there has been no head-to-head comparison for the efficacy and safety, especially given differing side effect profiles.

Methods and analysis

An international, multicentre, double-blind, dose increment, parallel-arm, RCT is planned. Inclusion criteria include: adults with cancer experiencing NCP refractory to opioids; Brief Pain Inventory (BPI)-item 3 (worst pain) of ≥4; Neuropathic Pain on the Leeds Assessment of Neuropathic Symptoms and Signs Pain Scale of ≥12 despite of an adequate trial of regular opioid medication (≥60 mg/day oral morphine equivalent dose). Patients with CIPN are excluded.

The study will recruit from palliative care teams (both inpatients and outpatients) in Japan and Australia. Participants will be randomised (1:1 allocation ratio) to duloxetine or pregabalin arm. Dose escalation is until day 14 and from day 14 to 21 is a dose de-escalation period to avoid withdrawal effects. The primary endpoint is defined as the mean difference in BPI item 3 for worst pain intensity over the previous 24 hours at day 14 between groups. A sample size of 160 patients will be enrolled between February 2020 and March 2023.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethics approval was obtained at Osaka City University Hospital Certified Review Board and South Western Sydney Local Health District Human Research Ethics Committee. The results of this study will be submitted for publication in international journals and the key findings presented at international conferences.

Trial registration numbers

jRCTs051190097, ACTRN12620000656932.

Keywords: adult palliative care, cancer pain, clinical trials

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first study to compare the analgesic efficacy and safety of duloxetine with pregabalin in patients experiencing neuropathic cancer pain (NCP) refractory to opioids, not induced by chemotherapy. The results of the trial will clarify the first-line standard of care for NCP.

A high-quality double-blind multicentre randomised controlled trial (RCT) study design adequately powered to provide a clinically meaningful outcome, and enable the safety and tolerability following intervention to be prospectively and systematically evaluated.

This study includes heterogeneous causes of NCP not related to chemotherapy to determine the pharmacological effects of pregabalin and duloxetine in sparsely studied but clinically relevant populations.

The primary endpoint is not average pain intensity over the past 24 hours but the difference in worst pain intensity score, which has shown the highest degree of internal consistency for assessing a pain-reduction treatment effect.

Recommendations for maximum dosing of adjuvant analgesics will be followed, and the results of this RCT will be the first to evaluate the efficacy of pharmacological treatment on well-defined NCP.

Introduction

Management of patients with cancer experiencing opioid-refractory neuropathic pain remains an important challenge. Neuropathic pain requires multipharmacological therapy, with adjuvant analgesics such as anticonvulsants and antidepressants, added to opioids; however, strong evidence for their efficacy in neuropathic cancer pain (NCP) is limited.1

According to numerous guidelines, gabapentinoids (pregabalin, gabapentin), tricyclic antidepressants (TCA) including amitriptyline and selective serotonin noradrenalin reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) including duloxetine are recommended with careful titration as first-line drugs.2–7 Among them, the efficacy of gabapentinoids for this population has already been demonstrated in three randomised controlled trials (RCTs) compared with placebo, arguably making this a standard of care.8–10 Data support gabapentinoids as promising, safe agents in this setting, warranting further evaluation in robust RCTs compared with other candidates (eg, SNRIs and TCAs). The results of two RCTs targeting NCP10 11 found the effect of TCA is limited and even in small dose (eg, amitriptyline; 30–50 mg/day), many adverse events (AEs) occurred. Pregabalin was superior in terms of analgesic effect and opioid reducing effect in comparisons among pregabalin, gabapentin, amitriptyline and placebo.10

Duloxetine has been reported to be effective in the management of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy (CIPN),12 but no randomised trials have examined its effects on opioid-refractory NCP. Although there is no standard first line treatment for NCP, a systematic review and meta-analysis suggested gabapentinoids be used first.13 Although there are few reports of duloxetine in NCP, Matsuoka et al have conducted a feasibility pretest and post-test14 and an RCT,15 16 which have shown the benefit of duloxetine (number needed to treat=3.4)15 and superiority for tingling pain.16 However, there are no RCTs of oral duloxetine for the management of opioid-refractory NCP.

In the double-blind RCT described here, we will evaluate the efficacy and safety of duloxetine and pregabalin for opioid-refractory NCP. Both classes of drug have the potential to reduce NCP, but there has been no head-to-head comparison for the efficacy and safety especially given differing side effect profiles. The results of this RCT may help to clarify the first-line standard treatment for NCP.

Methods and analysis

Study design

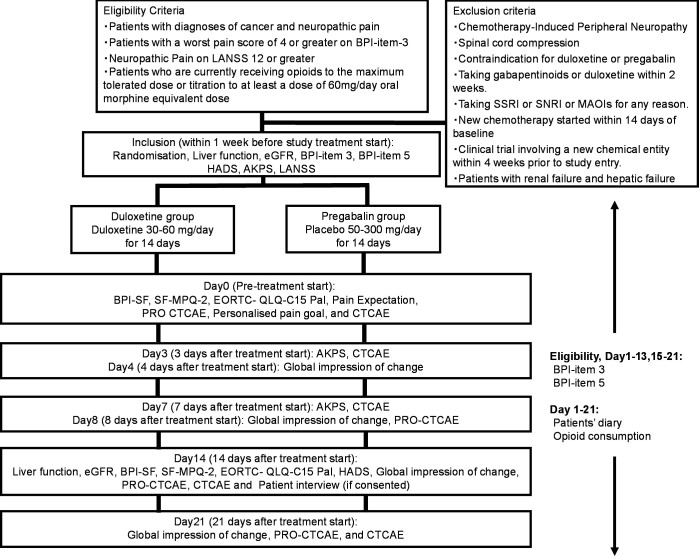

The Standard Protocol Items for Randomised Trials statement and its checklist were followed in preparing the protocol. This international, multicentre, randomised, double-blind, two-parallel arm, dose-increment study will be performed to compare the efficacy and safety of duloxetine and pregabalin for NCP (figure 1). This study will also have a qualitative substudy in which patient experience of the intervention will be explored if additional consent is provided.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the procedures in the study. Participants will be randomised (1:1 allocation ratio) into the duloxetine group or the pregabalin group. AKPS, Australia-modified Karnofsky Performance Status; BPI-SF, Brief Pain Inventory-Short Form; EORTC, European organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; LANSS, Leeds Assessment of Neuropathic Symptoms and Signs Pain Scale; MPQ-2, McGill Pain Questionnaire 2; PRO-CTCAE, Patient-Reported Outcomes version of the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events; SNRI, serotonin noradrenalin reuptake inhibitor; QLQ-C15, Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 15.

Study settings and participants

Participants will be recruited from adult palliative care sites across Japan and Australia (both inpatients and outpatients). The inclusion and exclusion criteria are summarised in box 1.

Box 1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Inclusion criteria

Inpatients and outpatients with diagnoses of cancer and neuropathic pain who, in the opinion of the site investigator, are candidates for therapy with duloxetine or pregabalin.

Insufficient response (defined as pain related to cancer with a worst pain score of ≥4 or greater on Brief Pain Inventory item 3 (worst pain intensity) score in the past 24 hours) to an adequate opioid medication (defined as the maximum tolerated dose or titration to at least 60 mg/day oral morphine equivalent dose for 24 hours unless contraindicated or further escalation is deemed unnecessary or inappropriate in the opinion of the clinical investigator).

Age 18 years or older (Japan 20 years or older).

Australia-modified Karnofsky Performance Status ≥50.

Taking stable regular analgesics (opioids, paracetamol, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) and any type of regular adjuvant analgesic (eg, antidepressants, anticonvulsants, antiarrhythmic agents, N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor antagonists, and steroids) within 72 hours before commencing on the study. Short-acting and rapid-onset breakthrough-opioids as needed may be used ≤4 doses/day and still be considered ‘stable’.

Exclusion criteria

Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy (glove and stocking distribution and prior use of a therapy known to cause this).

Spinal cord compression.

Contraindication for duloxetine or pregabalin.

Taking gabapentioids or duloxetine for any reason within the previous 2 weeks.

Taking Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor (SSRI) or serotonin noradrenalin reuptake inhibitor for any reason.

Taking a monoamine oxidase inhibitor.

Participants who have participated in a clinical trial involving a new chemical entity within 4 weeks prior to study entry.

Starting a new chemotherapy regimen within 14 days of baseline.

Patients with renal failure defined as estimated glemerular filtration rate (eGFR) ≤30 mL/min/1.73 m2 calculated according to the GFR-EPI equation.

Patients with hepatic failure (Child Pugh B or C).

Patients who have a recent history of drug misuse.

Patients who are pregnant, breast feeding or may possibly be pregnant.

Other patients who are determined to be inappropriate for participation in the study by the clinical investigator.

The main inclusion criterion will be adults experiencing cancer pain (neuropathic or mixed) refractory to opioids. Diagnosis of NCP is based on the International Association for the Study of Pain criteria, in which a diagnosis of NCP is made for patients with (1) pain with a distinct neuroanatomically plausible distribution; (2) a history suggestive of a relevant lesion or disease affecting the peripheral or central somatosensory system; (3) a range of pain that is neuroanatomically plausible and symptoms suggesting somatosensory injury or neurological disease (ie, hyperalgesia, hypoalgesia, dysesthesia or allodynia along the dermatome) and (4) relevant objective or imaging findings suggesting nervous system injury or disease (ie, imaging findings showing that a lesion is present). Based on these criteria, the certainty of the presence of NCP is graded as definite NCP (1–4 present) and probable NP (1–3).17 Definite and probable NCP will be considered to indicate NCP and patients with these conditions will be eligible as subjects. Patients with a worst Numerical Rating Scale (NRS) pain score (Brief Pain Inventory, BPI-item 3) in the preceding 24-hour period ≥418 and those with Leeds Assessment of Neuropathic Symptoms and Signs Pain Scale (LANSS) scores ≥12 will be included.19 The exclusion criteria will be patients with: CIPN (glove and stocking); spinal cord compression; contraindications for duloxetine or pregabalin; or impaired cognitive function.

Recruitment, randomisation, masking and follow-up

Recruitment

Eligible patients satisfying the screening inclusion and exclusion criteria will be invited to participate in the study by site investigators and informed consent will be obtained.

Randomisation

Physicians will introduce the trial to patients after screening for eligibility by nurse or staff. On enrolment, patients will be randomly allocated to duloxetine or pregabalin groups in a web-based central randomisation system using minimisation methods and a computer-generated randomisation schedule with a 1:1 allocation ratio. In performing this allocation, we will minimise the following adjustment factors20 to avoid a large bias: (1) worst pain intensity measured by the NRS in the last 24 hours (≤6, ≥7)2 21; (2) dose of opioid (≥90 mg oral morphine equivalent dose, 60–90 mg, 60 mg)22 23; (3) NRS total score (≤10, ≥11)24; (4) body weight (≥80 kg or <80 kg)25; (5) race (Australian (Asian descent; eg, China, India, Vietnam, Philippines),25 Australian (partial or no Asian descent), Japanese, others (eg, Italy South, Africa)) and (6) study site.25 26

Masking

Patients and clinicians responsible for treatment will be blinded to administration of duloxetine or pregabalin. Both the duloxetine and the pregabalin capsules will be indistinguishable by encapsulation and only unblinded pharmacists at each site will know the allocation result of each patient. Duloxetine (Cymbalta) and pregabalin (Lyrica) will be administered with a change in dosage form: the capsules will be covered with a No. 1 capsule (length 19 mm) of the same material to make an overcapsule.

Data management, central monitoring and audit

Evaluations will be performed at eight time points: eligibility, the day before the start of treatment (day 0; the time of randomisation), day 3, day 4, day 7, day 8, day 14 and day 21 after initiation of treatment. The timing and details of evaluations are given in table 1.

Table 1.

Times and events schedule

| Eligibility* baseline/D1 |

D2 | D3 | D4 | D5 | D6 | D7 | D8 | D 9–13 |

D 14/ET |

D 15–20 |

D 21 (EOS) |

|

| Investigations | ||||||||||||

| Consent randomisation | 〇* | |||||||||||

| Liver function, eGFR | 〇* | 〇 | ||||||||||

| Study drug administration | 〇 | 〇 | 〇 | 〇 | 〇 | 〇 | 〇 | 〇 | 〇 | 〇 | 〇 | 〇 |

| Medical file review | ||||||||||||

| Demographics, diagnosis | 〇* | |||||||||||

| Selected medications (eg, opioid) |

〇 | 〇 | 〇 | 〇 | 〇 | 〇 | 〇 | 〇 | 〇 | 〇 | 〇 | 〇 |

| Breakthrough medications | 〇 | 〇 | 〇 | 〇 | 〇 | 〇 | 〇 | 〇 | 〇 | 〇 | 〇 | 〇 |

| Patient assessed (PRO assessments) | ||||||||||||

| Daily diary | 〇 | 〇 | 〇 | 〇 | 〇 | 〇 | 〇 | 〇 | 〇 | 〇 | 〇 | 〇 |

| BPI-SF | 〇 | 〇 | ||||||||||

| Worst pain (BPI-item 3) | 〇* | 〇 | 〇 | 〇 | 〇 | 〇 | 〇 | 〇 | 〇 | 〇 | 〇 | |

| Average pain (BPI-item 5) | 〇* | 〇 | 〇 | 〇 | 〇 | 〇 | 〇 | 〇 | 〇 | 〇 | 〇 | |

| SF-MPQ-2 | 〇 | 〇 | ||||||||||

| EORTC-QLQ-PAL-C15 | 〇 | 〇 | ||||||||||

| HADS | 〇* | 〇 | ||||||||||

| Global impression of change | 〇 | 〇 | 〇 | 〇 | ||||||||

| Pain expectation | 〇 | |||||||||||

| PRO-CTCAE | 〇 | 〇 | 〇 | 〇 | ||||||||

| Clinician assessed | ||||||||||||

| Medical assessment | 〇* | |||||||||||

| Height and weight | 〇 | |||||||||||

| Vital signs | 〇 | 〇 | 〇 | |||||||||

| AKPS | 〇* | 〇 | 〇 | 〇 | ||||||||

| LANSS | 〇* | |||||||||||

| Personalised pain goal | 〇 | |||||||||||

| Adverse events (CTCAE) | 〇 | 〇 | 〇 | 〇 | 〇 | |||||||

| Substudies (if consented) | ||||||||||||

| Qualitative patient interview | 〇 | |||||||||||

*Data from 7 days before the commencing day of the treatment (not including the day of the commencing day) to just before the commencement of this study is allowed

AKPS, Australia-modified Karnofsky Performance Status; BPI-SF, Brief Pain Inventory-Short Form; CTCAE, Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events; EORTC-QLQ-PAL-C15, The European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 15 Palliative Care; EoS, End of Study; ET, early termination; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; LANSS, the Leeds Assessment of Neuropathic Symptoms and Signs; MPQ2, McGill Pain Questionnaire-2; PRO-CTCAE, patient-reported-CTCAE.

Once a patient is enrolled or randomised, the study site will make every effort to follow the patient for the entire study period. Patients will not be allowed to cross over from one group to another group until the end of the study, however, they can choose to leave the study for any reasons at any time without detriment to the provision or quality of their clinical care. The investigators at each study site will maintain individual records for each patient as source data, which will include a signed copy of informed consent, medical records, laboratory data and other records or notes. All data will be collected by the independent data management centre. The Japanese Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (JORTC) Data Centre (Japan) and the Improving Palliative Care through Clinical Trials Trials Coordination Centre (Australia) will oversee the intra-study data sharing process in each country. The clinical data entry, data management and central monitoring will be performed using the electric data capture system VIEDOC 4 (PCG Solutions, Sweden) in Japan and Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap, Vanderbilt University, USA) in Australia. An interim analysis will not be performed. Audit may take place by JORTC Audit Committee in Japan and by an external agency in Australia.

Safety assessments

Investigators must record all AEs in the medical records and web systems. The National Cancer Institute’s (NCI) Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE Ver.4.0)27 28 will be used to grade each AE. All AEs are to be followed up continually during their course. All serious AEs must be reported to Osaka City University Hospital Certified Review Board (CRB) and a Medical Monitor within Australia, with annual safety reporting to the Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC), and to investigators in all sites. Participants that are enrolled into the study will be treated by healthcare providers properly.

Assessment tools

All the appropriate permissions were obtained for the use for the assessment instruments.

BPI-Short Form

The BPI-Short Form (SF) will be used as it is a brief and easy tool for the assessment of pain within both the clinical and research settings. It has been validated in both the chronic pain and cancer settings. The NRS of 0–10 is simple for participants to use and reflects common clinical assessment of pain.29

Global Impression of Change

The Global Impression of Change is a participant-rated 7- point scale (1–7) that provides information about the participants’ perception of their overall change in pain since commencing the study. This will allow the investigators to compare the pain rating using the NRS with participant perception of improvement. The results of this scale over the study period will assist to determine the clinical significance of any improvement seen.30

Leeds Assessment of Neuropathic Symptoms and Signs

The LANSS estimates the probability that neuropathic mechanisms contribute to the chronic pain experience in each participant. It has 85% sensitivity for detecting neuropathic pain. It is a seven-item scale including sensory description and examination. A score of ≥12 indicates that neuropathic mechanisms are likely to contribute to the participant’s pain. It will be used to define a population with neuropathic pain.31 The LANSS will be collected to determine eligibility.

Short-Form McGill Pain Questionnaire 2

The SF-McGill Pain Questionnaire 2 (SF-MPQ-2)32 will be used to examine differences in effects due to pain mechanisms. The SF-MPQ-2 and its Japanese version have been validated in cancer neuropathic pain.33 It is a 22-item questionnaire covering the domains of superficial and deep spontaneous pain, paroxysmal pain, evoked pain and paresthesia/dysaesthesia. We also used this tool in the pilot study that underpins the current trial15 16 and consider the possibility of effective pain types. This time it will be used to make a comparison for that verification.

Personalised pain goal

The personalised pain goal34 is a tool used to tailor pain management to individual needs. ‘Participants are asked to describe on a 0–10 scale, the level/intensity of pain that will allow the patient to achieve comfort in physical, functional and psychosocial domains.’34 This will be asked by the research nurse or staff at baseline, and may include explanation of terminology. Zero will represent no pain and ten will represent worst pain. This is not a validated tool. We use this scale because some argued that neither between-group difference in mean values nor changes in pain intensity (eg, absolute or relative values) correctly evaluated the patient’s discomfort.

European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer-Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 15 Palliative Care

The European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 15 Palliative Care (QLQ-C15-PAL) will be used for evaluation of patient quality of life. The reliability and validity of the original version35 and Japanese version36 have been confirmed.

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale

The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS)37 will be used for measurement of psychiatric symptoms (anxiety and depression) of patients with a physical disease. HADS is a screening tool that allows assessment based on a small number of items. Its reliability and validity have been verified internationally.37 38

Patient expectation

Patient’s expectation of a decrease in pain of each patient will be examined as one study has shown the effect of expectation of pain decrease influenced pain prognosis in cancer pain.39

Australia-modified Karnofsky Performance Status (AKPS)

The Australia-modified Karnofsky Performance Status (AKPS)40 will be used to assess performance status. The AKPS is a useful modification of the Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS)41 and validated as an appropriate tool for palliative medicine.

CTCAE/Patient-Reported Outcomes version of the CTCAE

Any new or worse AEs will be evaluated and classified according to CTCAE criteria27 28 and the Patient-Reported Outcomes version of the CTCAE (PRO-CTCAE).42 PRO-CTCAE was developed by the NCI as an AE assessment system to evaluate patients’ subjective symptoms. Its content validity and psychometric validity have been verified in the original English version.42 43 Japanese version of the PRO-CTCAE had acceptable reliability and linguistic44 and psychometric45 validity for common and clinically important symptoms.

Interventions

All participants will take blinded opaque capsules each morning after breakfast and bedtime for 14 days. Dose escalation is until day 14 and from day 14 to 21 is a dose de-escalation period to avoid withdrawal effects. Participants will increase the study drugs to stage 2 on day 4 and to stage 3 on day 8. Participants will be assessed for AEs during the study period. If a person experiences mild, moderate, or severe AEs, as classified by the NCI Criteria, they will be treated symptomatically. If symptoms persist, participants will continue the previous dose prior to adverse symptoms being noted (or if on the amount of stage 1 will exit the study). If participants experience unacceptable AEs on: days 1–3 on the stage 1 drug (30 mg duloxetine or 50 mg pregabalin daily dose) they will be withdrawn from the study; days 4–7 on the stage 2 drug (30 mg duloxetine or 150 mg pregabalin daily dose) they will continue in the study to day 14 on stage 1 drug (30 mg duloxetine or 50 mg pregabalin daily dose); days 8–14 on the stage 3 drug (60 mg duloxetine or 300 mg pregabalin daily dose) they will continue in the study to day 14 on stage 2 drug (30 mg duloxetine or 150 mg pregabalin daily dose). Assessments to determine net clinical effect will be conducted on day 14. The dose will be tapered down until the amount of stage 1 (stage 3→2→1 or stage 2→1) and the medication will be stopped to avoid a discontinuation syndrome, mirroring the schedule for initial upwards titration (ie, duloxetine 30 mg/pregabalin 150 mg for 4 days, 30 mg/50 mg for 3 days then cease <from stage 3; days 15–21>or duloxetine 30 mg/pregabalin 50 mg for 3 days then cease <from stage 2; days 15–17 >). Rescue opioids will be available on an ‘as needed’ basis, up to eight doses of currently prescribed breakthrough opioid in any 24-hour period. Following cessation of study medications, participants will be reviewed by their treating clinician regarding any future open label prescribing of the study medications. If pain is present or reoccurs during the downward titration phase, the treating clinician should determine the most appropriate pain medication according to the local standard of care and monitor the patient closely.

Concomitant therapy

Concomitantly administered analgesics such as opioids, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, acetaminophen or other adjuvant analgesics such as anticonvulsants, antidepressants, antiarrhythmics, N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor antagonists and steroids will not be changed during the follow-up period. New analgesics will not be started. If nausea occurs during the treatment period, use of an antiemetic will be permitted.

Study endpoints

Primary endpoint

The primary endpoint is a mean difference between study arms of worst pain intensity over the previous 24 hours at day 14 measured using the BPI items 3.

Secondary endpoints

Efficacy will be assessed using the following secondary endpoints: the average pain intensity (BPI items 5) at days 14 and 21; the worst pain intensity (BPI items 3) at day 21; the SF-MPQ-2 scores; EORTC QLQ-C15-PAL scores; changes in HADS score; and daily opioid dose (on each day). AEs will also be assessed using NCI CTCAE and PRO-CTCAE.

Additionally, we will calculate percentage of participants with a reduction (BPI-I items 3) of 1 point; 2 points; >2 points; 30% and 50% pain decrease from the baseline on day 3, day 7 and day 14, percentage of participants in whom increase to the maximum dose is achieved, percentage of participants in whom can achieve personal pain goal, percentage of participants in whom need to adjust baseline opioids and adjuvant analgesics, the completion rate of the study medication and procedures, total daily dose of adjuvant analgesics use (on each day), prospectively sought AEs with the likelihood of relationship to intervention (toxicity), and health service utilisation planned and unplanned contact, investigations, hospitalisations.

Statistical considerations

All statistical procedures will be detailed in the statistical analysis plan through a blinded data review before data fixation, including the handling of missing values and necessity of sensitivity analysis. For the primary endpoint, the current policy is to employ observed case analysis when the number of missing observations is very small, and to employ multiple imputation when there are a certain number of missing observations and the missing mechanism is considered to be missing at random.

Statistical hypothesis

Comparison of the primary endpoint of the worst pain intensity (BPI items 3) at day 14 between duloxetine groups and pregabalin groups will be conducted using a two-sided Student’s t-test at a significance level of 5% according to the intention-to-treat principle. Point estimates and 95% CIs for the difference between two group means will be calculated.

The secondary endpoints of efficacy (BPI items 5, SF-MPQ-2, EORTC QLQ-C15-PAL, HADS, daily opioid dose, and group comparison of worst pain on the BPI-item3 in the previous 24 hours) will be evaluated similarly to the primary endpoint.

Longitudinal changes in BPI-item 3 and BPI-item 5 will be evaluated using mean scores and 95% CIs. The distribution of grades of AEs (NCI CTCAE and PRO-CTCAE) and the incidence of AEs of grade 3 or higher and of grade 4 will be determined. Subgroup analyses will be performed to evaluate the difference among various types of peripheral NCP.

Sample size calculation

The difference between group BPI-item 3 on day 14 is assumed to be one point and the SD of the NRS is taken to be 2.0 points.16 46 47 As there was no consensus about the minimal clinically important differences in NCP at the planning stage of the study, we decided to adopt 1-point difference compared with pregabalin as the clinical significant difference, according to the recommendation of interpreting the clinical importance of group differences in chronic pain clinical trials.46

Based on our primary outcome, which is worst pain intensity (BPI-item 3) at day 14, we will estimate 64 participants per group would detect a mean difference of 1.0 (SD 2.0; 80% power with a two-sided significance level of 0.05 for comparison).

Considering withdrawal and drop-out of 20%, we plan to recruit 160 participants into the study.

Ethical issues

All patients will be required to provide written informed consent. The study will be performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, the Australian Good Clinical Practice, and the Japan’s Clinical Trials Act. The protocol was approved by the Osaka City University Hospital CRB and the Scientific Advisory Committee (Palliative Care Clinical Studies Collaborative) within Australia with annual safety reporting to the approving HRECs. This trial has been registered with the clinical trials registries within both Japan and Australia. Modifications in the study protocol will be communicated to approving CRB (Japan) and HRECs (Australia). Each ethics committee or institutional review board will review informed consent materials given to participants and adapt according to their own institution’s guidelines.

Discussion

To our knowledge, the results of the recent systematic review48 has shown the low quality of currently available evidence on the effectiveness of adjuvant analgesics in the treatment of cancer pain and our subsequent clinical trial16 shows the low-quality evidence of adjuvant analgesics for opioid refractory NCP as well. There has been no RCT of the analgesic efficacy of oral duloxetine for the management of opioid refractory NCP as a first line treatment.

In our planned trial, the use of a randomised, double-blind, two-parallel arm design, is the most appropriate design to demonstrate the efficacy of a new therapy. Our findings using this approach may also allow international recommendations to be updated. We also considered a crossover design, but a parallel design was finally chosen, given that the cross-over design has several limitations, especially in this population,49 namely; the treatment might have carryover effects and alter the response to subsequent treatments; and palliative patients may not be in a comparable condition at the start of the crossover trial treatment period.

Several issues related to the content of the trial require discussion. There will be five major concerns: (1) the heterogeneity of causes of NCP, (2) risk of drug–drug interactions and masking/confounding of the true effect of the study intervention, (3) the choice of the primary endpoint, (4) necessity of a placebo group and (5) the dose schedule of each drugs.

First, to address the heterogeneous causes of NCP, we excluded patients with CIPN and central NP, and targeted patients with NCP non-responsive or intolerant to opioid therapy, but the trial might still be criticised due to combination of various peripheral NCPs in one study. Narrower criteria are theoretically possible, but accrual of patients who meet these criteria is likely to be difficult. Furthermore, in palliative care field, a framework for classifying research subpopulations to which the research findings are being applied by clinicians, health planners and funders in real-world settings has been suggested.50 We, thus, decided to include various types of peripheral NCP in the study, and subgroup analyses will be performed.

Second, although drugs with major drug-drug interactions with duloxetine or pregabalin (eg, contraindicated) will be excluded, continuation of the other adjuvant analgesics might cause the risk of moderate-minor drug–drug interactions. The possibility of masking/confounding of the true effect of the study intervention cannot be completely ruled out, however, randomisation will allow for some degree of balance between the groups.

Third, the primary endpoint is the difference in worst pain intensity score at day 14 between two groups. Although we had acknowledged that the average pain intensity is adopted by many clinical trials about NCP,51 including three RCTs8 9 16 in patients with NCP, some authors recommend worst pain intensity in the last 24 hours as primary endpoints because it satisfies most key recommendations in the draft guidance.18 Furthermore, to evaluate chronic pain, especially considering the nature of NCP in this setting, we concluded that it is better to use the ‘worst pain intensity in the last 24 hours’ as the primary endpoint after discussion among the members of the study’s steering committee.

Fourth, although we discussed the need for a placebo arm, gabapentinoids (gabapentin and pregabalin) are one of the most widely used treatments for NCP (not for just cancer pain, nor CIPN). Phase III studies8 10 revealed moderate analgesic effects of gabapentinoids (gabapentin and pregabalin) compared with placebo in combination with opioids for NCP (not for just cancer pain, nor CIPN). From the results of these 2 RCTs,8 10 we concluded that it was no longer ethical to use a placebo arm.

Finally, the following dose titration schedule has been devised to maximise the likelihood of benefit while minimising the risk of AEs. The participant will commence duloxetine or pregabalin at 30 mg and 50 mg, respectively, and will be titrated according to response in increments of cessation to a maximum of 60 mg (duloxetine) and 300 mg (pregabalin). As the starting dose differs between Australia and Japan, it was necessary to determine a uniform dose for the international study. The starting dose of duloxetine in Japan is 20 mg in the setting for palliative care,52 while in the West it is usually 30 mg or 60 mg. We chose 30 mg for the starting dose of duloxetine because we assumed that it was also tolerable for Japanese patients. In the same setting, the starting dose of pregabalin in Japan is 50 mg,52 while in the West it is usually 25–100 mg from the results of recent systematic review and meta-analysis.13 Taking these results into consideration, we assume that starting 150 mg pregabalin is not tolerable and 50 mg is safe for patients in both countries. Dworkin et al conducted a systematic review of pharmacologic management of NCP and made the recommendations for maximum dosing53 and according to the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guideline of adult cancer pain2 we have defined initiation dose and maximum dose of both drugs.

Moreover, we set a dose decrement titration periods instead of doing key open to avoid a discontinuation syndrome of each drug and to keep scientific reliability. Therefore, the planned international double-blind multi-centre RCT will be the first to evaluate the efficacy and safety of duloxetine and pregabalin treatment in patients suffering from well-defined NCP refractory to opioids, and the results of the trial will help to clarify the first-line standard treatment for NCP.

Trial status

The trial opened in January 2020. At the time of manuscript submission (February 2021), 21 patients have been randomised. We expect to complete the recruitment by September 2022 and to finish this trial by March 2023.

Confidentially

Data will be retained in accordance with the Japanese Clinical Research Act and the Australian regulations for Good Clinical Practice. Participants will be allocated a unique identification (ID) number at entry. The master list linking participant personal information and ID number will be maintained in a separate locked cabinet and password-protected hard drive at each institution. Data will be analysed by ID number only. Records will be retained for 15 years after study completion and then destroyed by the data centre.

Dissemination

The results of this trial will be submitted for publication in international peer-reviewed journals and the key findings presented at conferences. Participants will be informed of the results of the trial by the investigators. Authorship will be ascribed in accordance with the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors guidance.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for support from the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED), Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research, and the Australian Government National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Clinical Trials and Cohort Studies funding. The authors thank in advance all the patients, investigators, patients and caregivers’ representatives and institutions involved in this study.

Footnotes

Contributors: HM, KC, BF, LB, HI, YM, HH, KA, JL, BL, PA, SK, NF, TM, ML, MA, ES, SI, JP, AK and DCC participated in the design of the study. SO and TY designed the statistical analysis plan. All authors contributed to writing and revising the manuscript critically, and all gave their final approval of the version to be published.

Funding: This work was supported by the following grant: 2017–2019 Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED) award (19ck0106328h0003, Innovative Clinical Cancer Research) and will be supported by the following grants: 2020–2024 Australian Government National Health and Medical Research Council Clinical Trials and Cohort Studies funding (NHMRC: APP1188023) and 2020–2022 Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED) award (20ck0106603h9901, Innovative Clinical Cancer Research).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

References

- 1.Jongen JLM, Huijsman ML, Jessurun J, et al. The evidence for pharmacologic treatment of neuropathic cancer pain: beneficial and adverse effects. J Pain Symptom Manage 2013;46:581–90. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2012.10.230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Swarm RA, Paice JA, Anghelescu DL, et al. Adult cancer pain, version 3.2019, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2019;17:977–1007. 10.6004/jnccn.2019.0038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cruccu G, Truini A. A review of neuropathic pain: from guidelines to clinical practice. Pain Ther 2017;6:35–42. 10.1007/s40122-017-0087-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Palliative care for patients with incurable cancer. Available: https://www.awmf.org/fileadmin/user_upload/Leitlinien/128_D_Ges_fuer_Palliativmedizin/128-001OLkengl_S3_Palliative_care_2021-03.pdf [Accessed 24 Sep 2021].

- 5.Piano V, Verhagen S, Schalkwijk A, et al. Treatment for neuropathic pain in patients with cancer: comparative analysis of recommendations in national clinical practice guidelines from European countries. Pain Pract 2014;14:1–7. 10.1111/papr.12036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Piano V, Schalkwijk A, Burgers J, et al. Guidelines for neuropathic pain management in patients with cancer: a European survey and comparison. Pain Pract 2013;13:349–57. 10.1111/j.1533-2500.2012.00602.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Attal N, Cruccu G, Baron R. European Federation of neurological societies. EFNS guidelines on the pharmacological treatment of neuropathic pain: 2010 revision. Eur J Neurol 2010;17:1113–88. 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2010.02999.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Caraceni A, Zecca E, Bonezzi C, et al. Gabapentin for neuropathic cancer pain: a randomized controlled trial from the gabapentin cancer pain Study Group. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2004;22:2909–17. 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dou Z, Jiang Z, Zhong J. Efficacy and safety of pregabalin in patients with neuropathic cancer pain undergoing morphine therapy. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol 2017;13:e57–64. 10.1111/ajco.12311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mishra S, Bhatnagar S, Goyal GN, et al. A comparative efficacy of amitriptyline, gabapentin, and pregabalin in neuropathic cancer pain: a prospective randomized double-blind placebo-controlled study. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2012;29:177–82. 10.1177/1049909111412539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mercadante S, Arcuri E, Tirelli W, et al. Amitriptyline in neuropathic cancer pain in patients on morphine therapy: a randomized placebo-controlled, double-blind crossover study. Tumori 2002;88:239–42. 10.1177/030089160208800310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith EML, Pang H, Cirrincione C, et al. Effect of duloxetine on pain, function, and quality of life among patients with chemotherapy-induced painful peripheral neuropathy. JAMA 2013;309:1359–67. 10.1001/jama.2013.2813 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kane CM, Mulvey MR, Wright S, et al. Opioids combined with antidepressants or antiepileptic drugs for cancer pain: systematic review and meta-analysis. Palliat Med 2018;32:276–86. 10.1177/0269216317711826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Matsuoka H, Makimura C, Koyama A, et al. Pilot study of duloxetine for cancer patients with neuropathic pain non-responsive to pregabalin. Anticancer Res 2012;32:1805–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matsuoka H, Iwase S, Miyaji T, et al. Predictors of duloxetine response in patients with neuropathic cancer pain: a secondary analysis of a randomized controlled trial-JORTC-PAL08 (direct) study. Support Care Cancer 2020;28:2931–9. 10.1007/s00520-019-05138-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Matsuoka H, Iwase S, Miyaji T. Additive duloxetine for cancer-related neuropathic pain nonresponsive or intolerant to Opioid-Pregabalin therapy: a randomized controlled trial (JORTC-PAL08). J Pain Symptom Manage 2019:30364–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Finnerup NB, Haroutounian S, Kamerman P, et al. Neuropathic pain: an updated grading system for research and clinical practice. Pain 2016;157:1599–606. 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Atkinson TM, Mendoza TR, Sit L, et al. The Brief Pain Inventory and its "pain at its worst in the last 24 hours" item: clinical trial endpoint considerations. Pain Med 2010;11:337–46. 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2009.00774.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mulvey MR, Boland EG, Bouhassira D, et al. Neuropathic pain in cancer: systematic review, performance of screening tools and analysis of symptom profiles. Br J Anaesth 2017;119:765–74. 10.1093/bja/aex175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Therneau TM. How many stratification factors are "too many" to use in a randomization plan? Control Clin Trials 1993;14:98–108. 10.1016/0197-2456(93)90013-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smith SM, Dworkin RH, Turk DC, et al. Interpretation of chronic pain clinical trial outcomes: IMMPACT recommended considerations. Pain 2020;161:2446–61. 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gaudreau J-D, Gagnon P, Harel F, et al. Psychoactive medications and risk of delirium in hospitalized cancer patients. J Clin Oncol 2005;23:20:6712–8. 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grond S, Radbruch L, Meuser T, et al. High-Dose tramadol in comparison to low-dose morphine for cancer pain relief. J Pain Symptom Manage 1999;18:174–9. 10.1016/S0885-3924(99)00060-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brown LF, Kroenke K, Theobald DE, et al. The association of depression and anxiety with health-related quality of life in cancer patients with depression and/or pain. Psychooncology 2010;19:734–41. 10.1002/pon.1627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Saquib N, Saquib J, Ioannidis JPA. Practices and impact of primary outcome adjustment in randomized controlled trials: meta-epidemiologic study. BMJ 2013;347:f4313. 10.1136/bmj.f4313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moher D, Hopewell S, Schulz KF, et al. Consort 2010 explanation and elaboration: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ 2010;340:c869. 10.1136/bmj.c869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.National Cancer Institute . National Institutes of health, us department of health and human services. common terminology criteria for adverse events version 4.03 (CTCAE), 2010. Available: https://evs.nci.nih.gov/ftp1/CTCAE/About.html [Accessed 10 Feb 2018].

- 28.Japan Clinical Oncology Group . Common terminology criteria for adverse events version 4.0 (CTCAE v4.0-JCOG). Available: http://www.jcog.jp/doctor/tool/CTCAEv4J_20170912_v20_1.pdf [Accessed 10 Feb 2018].

- 29.Cleeland CS. Measurement of pain by subjective report. In: Chapman CRL, ed. Advances in pain research and therapy. volume 12: issues in pain measurement. New York: Raven Press, 1989: 391–403. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Farrar JT, Young JP, LaMoreaux L, et al. Clinical importance of changes in chronic pain intensity measured on an 11-point numerical pain rating scale. Pain 2001;94:149–58. 10.1016/S0304-3959(01)00349-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bennett M. The LANSS pain scale: the Leeds assessment of neuropathic symptoms and signs. Pain 2001;92:147–57. 10.1016/S0304-3959(00)00482-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dworkin RH, Turk DC, Revicki DA, et al. Development and initial validation of an expanded and revised version of the short-form McGill pain questionnaire (SF-MPQ-2). Pain 2009;144:35–42. 10.1016/j.pain.2009.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maruo T, Nakae A, Maeda L, et al. Validity, reliability, and assessment sensitivity of the Japanese version of the short-form McGill pain questionnaire 2 in Japanese patients with neuropathic and non-neuropathic pain. Pain Med 2014;15:1930–7. 10.1111/pme.12468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dalal S, Hui D, Nguyen L, et al. Achievement of personalized pain goal in cancer patients referred to a supportive care clinic at a comprehensive cancer center. Cancer 2012;118:3869–77. 10.1002/cncr.26694 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Groenvold M, Petersen MA, Aaronson NK, et al. The development of the EORTC QLQ-C15-PAL: a shortened questionnaire for cancer patients in palliative care. Eur J Cancer 2006;42:55–64. 10.1016/j.ejca.2005.06.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miyazaki K, Suzukamo Y, Shimozuma K, et al. Verification of the psychometric properties of the Japanese version of the European organization for research and treatment of cancer quality of life questionnaire core 15 palliative (EORTCQLQ-C15-PAL). Qual Life Res 2012;21:335–40. 10.1007/s11136-011-9939-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1983;67:361–70. 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kugaya A, Akechi T, Okuyama T, et al. Screening for psychological distress in Japanese cancer patients. Jpn J Clin Oncol 1998;28:333–8. 10.1093/jjco/28.5.333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Matsuoka H, Yoshiuchi K, Koyama A, et al. Expectation of a decrease in pain affects the prognosis of pain in cancer patients: a prospective cohort study of response to morphine. Int J Behav Med 2017;24:535–41. 10.1007/s12529-017-9644-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Abernethy AP, Shelby-James T, Fazekas BS, et al. The Australia-modified Karnofsky Performance Status (AKPS) scale: a revised scale for contemporary palliative care clinical practice [ISRCTN81117481]. BMC Palliat Care 2005;4:7. 10.1186/1472-684X-4-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Karnofsky D, Abelmann W, Craver L. The use of nitrogen mustard in the palliative treatment of cancer. Cancer 1948;1:634–56. doi:1097-0142(194811)1:43.0.CO;2-L [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hay JL, Atkinson TM, Reeve BB, et al. Cognitive interviewing of the US National cancer Institute's patient-reported outcomes version of the common terminology criteria for adverse events (PRO-CTCAE). Qual Life Res 2014;23:257–69. 10.1007/s11136-013-0470-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dueck AC, Mendoza TR, Mitchell SA, et al. Validity and reliability of the US National cancer Institute's patient-reported outcomes version of the common terminology criteria for adverse events (PRO-CTCAE). JAMA Oncol 2015;1:1051. 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.2639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Miyaji T, Iioka Y, Kuroda Y, et al. Japanese translation and linguistic validation of the US National cancer Institute's patient-reported outcomes version of the common terminology criteria for adverse events (PRO-CTCAE). J Patient Rep Outcomes 2017;1:8. 10.1186/s41687-017-0012-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kawaguchi T, Azuma K, Sano M, et al. The Japanese version of the National cancer Institute's patient-reported outcomes version of the common terminology criteria for adverse events (PRO-CTCAE): psychometric validation and discordance between clinician and patient assessments of adverse events. J Patient Rep Outcomes 2017;2:2. 10.1186/s41687-017-0022-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dworkin RH, Turk DC, McDermott MP, et al. Interpreting the clinical importance of group differences in chronic pain clinical trials: IMMPACT recommendations. Pain 2009;146:238–44. 10.1016/j.pain.2009.08.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Finnerup NB, Attal N, Haroutounian S, et al. Pharmacotherapy for neuropathic pain in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Neurol 2015;14:162–73. 10.1016/S1474-4422(14)70251-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.van den Beuken-van Everdingen MHJ, de Graeff A, Jongen JLM, et al. Pharmacological treatment of pain in cancer patients: the role of adjuvant analgesics, a systematic review. Pain Pract 2017;17:409–19. 10.1111/papr.12459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Senn SS. Cross-Over trials in clinical research. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Currow DC, Wheeler JL, Glare PA, et al. A framework for generalizability in palliative care. J Pain Symptom Manage 2009;37:373–86. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2008.03.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.McNicol ED, Midbari A, Eisenberg E. Opioids for neuropathic pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013:CD006146. 10.1002/14651858.CD006146.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Matsuoka H, Tagami K, Ariyoshi K, et al. Attitude of Japanese palliative care specialists towards adjuvant analgesics cancer-related neuropathic pain refractory to opioid therapy: a nationwide cross-sectional survey. Jpn J Clin Oncol 2019;49:486–90. 10.1093/jjco/hyz002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dworkin RH, O'Connor AB, Backonja M, et al. Pharmacologic management of neuropathic pain: evidence-based recommendations. Pain 2007;132:237–51. 10.1016/j.pain.2007.08.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.