Abstract

Rapid enterovirus detection is important for decisions about antibiotic administration and length of hospital stay. The efficacy of rapid antigen detection-cell culture amplification (Ag-CCA) was evaluated with monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) 5-D8/1 (DAKO) and Pan-Enterovirus clone 2E11 (Chemicon) with 10 poliovirus, echovirus, and coxsackievirus type A and B stock isolates and College of American Pathologists check samples. By using Ag-CCA technology, MAb 2E11 was more sensitive than 5-D8/1 at detecting a greater number of stock isolates at or past tube (cytopathic effect [CPE]) culture (TC) end points. The efficacy of Ag-CCA in the clinical setting was subsequently confirmed with 273 consecutively freshly collected nasopharyngeal aspirate or swab specimens, rectal swab, and cerebrospinal fluid specimens during the 1999 enterovirus season. All specimens were tested by Ag-CCA in parallel with rhesus monkey kidney (RhMk), MRC-5, and A549 conventional TCs. Approximately 60% of field specimens were additionally tested with Hep-2 and HNK conventional TCs. Sixty-two percent of the clinical specimens tested were Ag-CCA positive after 48 h. Among 51 isolates, the mean time to CPE or culture confirmation was 5.5 days (range, 2 to 18 days). After 48 h, Ag-CCA achieved sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive values of 62, 100, 100, and 93%, respectively. During the same period, TC-CPE displayed test parameters of 12, 100, 100, and 85%, respectively. After 5 days, the sensitivity and specificity of Ag-CCA increased to 92 and 98%, respectively. Within the same period, isolation attained sensitivity and specificity of 52 and 100%, respectively. Although Ag-CCA displayed slightly reduced sensitivity and reduced specificity compared with conventional cell culture after 14 days, the markedly superior 48-h enterovirus Ag-CCA detection rate supports incorporation of this assay into the routine clinical setting.

During the summer season, enteroviruses are responsible for the majority of viral diseases among pediatric and adult patients. Approximately 10 to 15 million symptomatic infections due to enteroviruses occur each year, resulting in a variety of disease syndromes (9). A rapid laboratory diagnosis of an enterovirus infection is important in patient care and management (e.g., decisions about antibiotic use and length of hospital stay). The significance of rapid enterovirus diagnostics is further underscored by recent progress in enterovirus drug research (8).

Enteroviruses in general grow rapidly in cell culture. Most clinical enterovirus strains are isolated within 4 to 5 days of conventional culture inoculation (S. M. Lipson, unpublished observations). The need to perform subpassages on toxic cultures and/or the performance of culture confirmation may add an additional 24 or more h to test turnaround time. In one study with stool isolates, for example, a mean time to isolation and confirmation of 11.5 ± 5 days was reported (1).

Molecular diagnostics, both “automated” and nonautomated, have been introduced to the laboratory medicine community. Molecular enterovirus testing, although more sensitive than conventional cell culture (14) is expensive and requires a designated laboratory facility. Furthermore, the enterovirus season is short-lived (viz., commonly 6 to 8 weeks), which raises questions about the cost-effectiveness of bringing enterovirus genome amplification technology into the general virology or microbiology laboratory setting.

Antigen detection-cell culture amplification (Ag-CCA) has been shown to be effective for the rapid detection of viruses in clinical specimens (3, 6). However, in the clinical laboratory setting, use of this technology has been limited primarily, if not totally, to nonenterovirus groups. Several research teams have addressed the potential application of an enterovirus Ag-CCA assay (4, 11, 12). However, those studies did not employ freshly collected specimens and utilized in-house-seeded shell vials or microtiter plates—characteristic of those found in the research setting.

The purpose of this study was to determine the efficacy of the enterovirus Ag-CCA assay by using commercially manufactured shell vials and a current generation (and heretofore untested) monoclonal antibody (MAb), as well as by incorporating freshly collected clinical (field) specimens.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Clinical specimens and reference viruses.

The initial phase of this study utilized reference enterovirus isolates, including 10 coxsackievirus A and B, echovirus, and poliovirus strains. All strains were obtained from the Virology Service (North Shore University Hospital, Manhasset, N.Y.) Culture Collection and from New York State Proficiency test samples.

Subsequent field testing utilized consecutively collected specimens obtained during the 1999 summer enterovirus season. Patient specimen sources consisted of nasopharyngeal swabs (NP), NP aspirates (NPA), sputum, rectal swabs (RS), and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). Approximately 90% of the specimens used in this study were obtained from pediatric patients. A unity prevailed among specimens received from male and female patients.

Cell culture.

All clinical (field) specimens were inoculated into A549, rhesus monkey kidney (RhMk), and MRC-5 conventional tube cultures (TCs). Hep-2 and HNK TC, were added to the routine cell culture panel based upon the specimen source and clinical symptoms (e.g., vesicular lesions) upon clinical presentation. Culture confirmation of the enterovirus cytopathic effect (CPE) was performed by indirect immunofluorescence testing with reagents 5-D8/1 and 2E11 (see below).

Virus titration.

The titers of all reference enterovirus strains were determined in primary RhMk conventional TCs. Briefly, RhMk TCs were inoculated in pentuplicate at 10-fold serial dilutions. Cultures were incubated at 36.5°C for 14 days. Viral titers were determined by the Reed-Muench end point procedure (7).

Ag-CCA. (i) Immunoreagents.

Enterovirus clone 5-D8/1 (catalog no. M7064; DAKO Corporation, Carpinteria, Calif.) and the Pan-Enterovirus 2E11 MAb (catalog no. 3362; Chemicon International, Inc., Temecula, Calif.) immunoreagents were used in the establishment of the enterovirus Ag-CCA assay. Reagent 5-D8/1 reacts with the highly conserved VP1 region of the enterovirus (11). Reagent 2E11 is an enterovirus group-specific MAb to the viral capsid (12). Preliminary titration experiments revealed that each immunoreagent attained an optimal immunofluorescent signal at the concentration supplied by the manufacturer.

(ii) Specimen inoculation and antigen detection.

RhMk shell vials were purchased from BioWhittaker, Inc., Walkersville, Md. Briefly, RhMk shell vials were inoculated in duplicate with 0.2 ml of enterovirus reference strains (at the viral end point) or field (clinical) specimens. Shell vials were centrifuged at 600 × g for 60 min at 36 ± 1°C, followed by the addition of serum-free maintenance medium. After 48 h for reference strains and 24, 48, 72, 96, and 120 h for field strains, the vials were washed with 1× phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), harvested, fixed in acetone at 4°C, and then immunostained with MAb 5-D8/1 and/or 2E11. Clone 2E11 was used in initial and field strain testing. Clone 5-D8/1 was used in initial assay development only. The secondary immunostaining reagent consisted of a fluorescent-conjugated goat anti-mouse whole-molecule MAb supplemented with Evans blue counterstain (Organon Teknika Corp., Cappel Research Reagents, Durham, N.C.). The negative control consisted of PBS in place of the primary immunoreagents. Conventional RhMk, A549, MRC-5, Hep-2, and HNK TCs (Hep-2 and HNK TCs were used to supplement RhMk, A549, and MRC-5 in the testing of ca. 60% of field specimens) were inoculated in parallel with all RhMk shell vials. Positive signals were identified by the appearance of a cytoplasmic apple-green stippling or a broad cytoplasmic apple-green signal among the reagents 2E11 and 5-8D/1, respectively. Readings were reported as mean focus-forming units per two shell vials. Shell vials were read with a Nikon UFX epifluorescent microscope equipped with a 100-W mercury bulb. The RhMk monolayers were read under a ×40 objective; confirmatory readings, if necessary, were performed with a ×50 oil immersion objective.

Specimen interpretation.

AG-CCA, TC-CPE-negative specimens were considered true negatives. AG-CCA-positive, TC-CPE-positive results were interpreted as true-positive specimens. Among the 273 clinical specimens tested in this study, a single AG-CCA-positive, TC-CPE-negative specimen (no. 2127) was deemed uninterpretable; resolution testing of this sole discordant specimen would not have a significant impact on the results of this study.

Statistics.

The McNemar test was used to compare qualitative differences in virus detection between cell cultures. Sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive values (PPV and NPV, respectively) of the AG-CCA and TC-CPE assays were calculated according to standard procedures (10).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Comparison of cell types for the isolation of NPEVs.

Prior to laboratory testing of the Ag-CCA assay, there was a need to confirm the cell type within our (cell culture) panel that permitted maximum isolation of non-polio enterovirus (NPEV) strains seen in our clinical setting. Among 32 clinical specimens consecutively tested with A549, primary RhMk, MRC-5, Hep-2, and HNK cells, RhMk and MRC-5 cells demonstrated the greatest NPEV yields (Table 1). These findings were similar to those reported by Chonmaitree et al. (2), but indicated that MRC-5 was slightly more sensitive than monkey kidney. Although no statistical difference was recognized in our comparison of RhMk and MRC-5 cells for the isolation of NPEVs from clinical specimens (P = 0.27), the slightly higher recovery rate observed with RhMk directed our use of RhMk as the sole cell type for the performance of the Ag-CCA assay.

TABLE 1.

Cell culture sensitivity to NPEV

| Specimen no. | Conventional TC resulta

|

Virus Serotype | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A549 | RhMk | MRC-5 | Hep-2 | HNK | ||

| 1589 | + | + | − | − | + | CB4 |

| 1638 | + | − | + | − | − | E30 |

| 1640 | + | + | − | + | + | NT |

| 1644 | − | + | + | − | + | CB3 |

| 1655 | − | + | + | − | + | E18 |

| 1747 | − | + | + | − | − | CB5 |

| 1802 | + | + | − | − | − | E21 |

| 1804 | − | + | + | − | − | E13 |

| 1845 | − | − | + | − | − | E11 |

| 1864 | − | − | + | − | − | NT |

| 1873 | − | + | − | − | − | NT |

| 1909 | − | + | − | − | − | E15 |

| 1910 | + | + | − | − | − | E7 |

| 1922 | + | + | − | − | − | CA7 |

| 1923 | − | − | + | − | − | E15 |

| 1926 | + | + | + | − | − | E11 |

| 1927 | + | − | − | − | − | NT |

| 1945 | − | + | − | − | − | E15 |

| 1960 | + | + | − | − | − | E20 |

| 1963 | + | + | + | − | − | CA9 |

| 1964 | − | + | + | − | − | E5 |

| 1990 | − | − | + | − | − | E15 |

| 1991 | + | + | + | − | − | E17 |

| 1993 | − | + | + | + | + | E14 |

| 1994 | − | + | + | − | − | CB4 |

| 1999 | − | + | + | − | − | CA9 |

| 2053 | + | − | + | − | − | CB4 |

| 2055 | + | + | − | − | + | CB4 |

| 2096 | − | + | − | − | − | E14 |

| 2128 | − | − | − | − | + | NT |

| 2178 | + | + | + | − | + | E15 |

| 2188 | − | + | + | − | − | CB3 |

| Total positive (%) | 14 (43) | 24 (75) | 19 (59) | 2 (<1) | 8 (<1) | |

RhMk versus A549, P = 0.02; RhMk versus MRC-5 P = 0.27; A549 versus MRC-5, P = 0.35; A549 versus HNK, P = 0.002; A549 versus HNK, P = 0.19.

NT, not typeable with LBM enterovirus pools (specimens identified as NPEVs by exclusion with Chemicon's Pan-Enterovirus clone 2E11 and poliovirus blend).

Ag-CCA assay standardization under laboratory conditions.

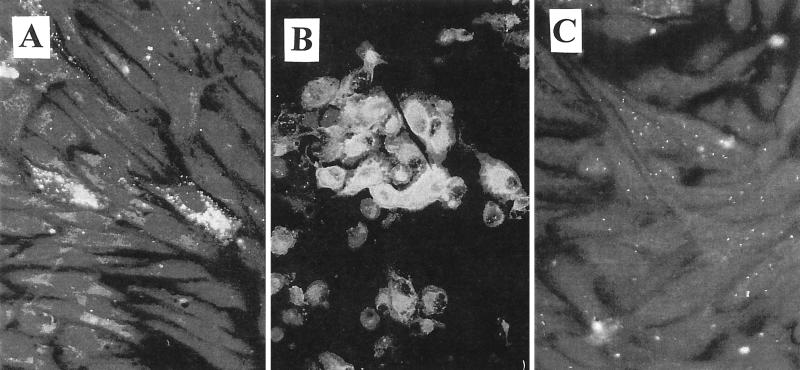

The efficacies of MAb clones 2E11 and 5-D8/1 were evaluated in parallel with 10 coxsackievirus, echovirus, and poliovirus strains. Antibody 2E11 and 5-D8/1 immunostaining patterns and intensities of signal were compared to isolation in conventional RhMk TCs utilizing stock enterovirus cultures at viral end points (7). Clone 5-D8/1, in concert with Ag-CCA, was more sensitive than conventional TC isolation (TC-CPE) among 4 of 10 enterovirus strains. Clone 2E11 was more sensitive than TC-CPE among 8 of 10 enterovirus strains. Ag-CCA utilizing clone 5-D8/1 was less sensitive than TC-CPE among 2 of 10 laboratory-adapted strains. The Ag-CCA assay incorporating clone 2E11 was equal to or more sensitive than TC-CPE among all 10 laboratory-adapted enterovirus strains (Table 2). These findings may be ascribed to unique differences in immunofluorescent staining patterns and signal intensities produced by the respective MAb clones. As shown in Fig. 1, clone 5-8D/1 produced a broad cytoplasmic immunofluorescent pattern that was difficult to discern from background fluorescence near the viral end point. In contrast, MAb clone 2E11 demonstrated a more recognizably definitive cytoplasmic apple-green immunofluorescent stippling pattern, permitting a readily interpretative signal at low viral titers. It is proposed that the use of enterovirus clone 2E11, rather than clone 5-D8/1, would more appropriately address the issue of low-level viral antigen detection within the centrifugation assay system herein described.

TABLE 2.

Comparison of MAb clones 5-D8/1 and 2E11 for the rapid Detection of enteroviruses by AG-CCA

| Virus type | Positive result witha:

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AG-CCA > TCID50

|

AG-CCA < TCID50

|

AG-CCA = TCID50

|

||||

| 5-D8/1 | 2E11 | 5-D8/1 | 2E11 | 5-D8/1 | 2E11 | |

| Poliovirus | ||||||

| 1 | Yes | Yes | ||||

| 3 | Yes | Yes | ||||

| Echovirus | ||||||

| 6 | Yes | Yes | ||||

| 9 | Yes | Yes | ||||

| 11 | Yes | Yes | ||||

| 30 | Yes | Yes | ||||

| Coxsackievirus | ||||||

| A9 | Yes | Yes | ||||

| A16 | Yes | Yes | ||||

| B3 | Yes | Yes | ||||

| B5 | Yes | Yes | ||||

The AG-CCA and conventional RhMk TC assay systems were inoculated with enterovirus stock cultures at viral end point concentrations. TCID50, 50% tissue culture infective dose. AG-CCA > TCID50, detection of enterovirus antigen (i.e., AG-CCA) occurred 24 to 48 h prior to isolation; AG < TCID50, isolation in conventional TC, occurred 24 to 48 h prior to antigen detection by AG-CCA; AG-CCA = TCID50, no difference to the time of viral detection by AG-CCA or isolation in conventional TCs was identified.

FIG. 1.

Immunofluorescent signal patterns obtained by using reagents 2E11 and 5-8D/1. (A) Reagent 2E11, positive signal. (B) Reagent 5-8D/1, positive signal. (C) Negative control. Original magnification, ×400.

Ag-CCA testing under clinical (field) conditions.

Based on preliminary data ascertained from the testing of laboratory-adapted strains, testing was extended with clone 2E11 to clinical specimens collected during the peak period of the 1999 summer enterovirus season.

Two hundred seventy-three clinical specimens, collected from 22 July 1999 through 8 October 1999, were assayed by Ag-CCA with reagent 2E11 in parallel with conventional TCs (Table 3). After an incubation period of 5 days (120 h), Ag-CCA attained a sensitivity and specificity of 92 and 98%, respectively. Within the same period, isolation in a conventional primary RhMk TC attained a sensitivity and specificity of 52 and 100%, respectively. After two days (48 h), Ag-CCA achieved a sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV of 62, 100, 100, and 93%, respectively. Within the same period, isolation attained a sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV of 12, 100, 100, and 85%, respectively. As seen on Table 3, the disparity between enterovirus detection and isolation rates decreased after extended incubation periods, with TC-CPE after 9 days postassay inoculation approaching that of Ag-CCA at day 5.

TABLE 3.

Comparison of AG-CCA and conventional TC for detection of enterovirus in clinical specimensa

| No. of days (h) to TC isolation | Cumulative no. positive

|

% Positive

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ag-CCA | TC-CPE | Ag-CCA | TC-CPE | |

| 1 (24) | 17 | 0 | 33 | 0 |

| 2 (48) | 31 | 6 | 62b | 12c |

| 3 (72) | 37d | 12 | 73 | 23 |

| 4 (96) | 46 | 23 | 90 | 42 |

| 5 (120) | 47 | 27 | 92 | 52 |

| 6 (144) | NDe | 32 | ND | 62 |

| 7 (168) | ND | 38 | ND | 73 |

| 8 (192) | ND | 42 | ND | 81 |

| 9 (216) | ND | 47 | ND | 90 |

| ≥10 (≥244) | ND | 51 | ND | 98 |

Among 273 specimens tested during the 1999 enterovirus season, 51 (19%) were resolved as true positives by Ag-CCA and TC-CPE. The date to tube culture isolation was tabulated from the date of culture (IFA) confirmation. Approximately 10 specimens required subpassage, thereby delaying the TC isolation final report by ∼24 h.

Sensitivity (after 48 h), 62%; specificity, 100%; PPV, 100%; NPV, 93%.

Sensitivity (after 48 h), 12%; specificity, 100%; PPV, 100% NPV, 85%.

Specimens negative after 24 or 48 h only were tested for an additional 3 days by Ag-CCA. After 120 h, Ag-CCA sensitivity and specificity were and 98%, respectively.

ND, not done.

Improved enterovirus detection rates with Ag-CCA will occur following daily testing regimens of replicate RhMk shell vials at 48, 72, 96, or longer periods (Table 3). However, the reading of shell vials at 72 or 96 h would extend turnaround time and, in turn, reduce the clinical relevancy of the test. Technologist work hours, furthermore, would increase because of the daily processing and reading of enterovirus centrifugation culture vials. Notwithstanding, the laboratorian and infectious diseases specialist must jointly address the significance of extended AG-CCA incubation periods (to improve assay sensitivity), turnaround time, and cost effectiveness in relation to the critical issue of patient care and management.

By utilizing conventional cell culture technology, an isolation rate greater than 98% (final results reported after culture confirmation) was achieved on or after an incubation period of 10 days (Table 3). Among the 51 positive (field or clinical) specimens identified in this study, the mean time to CPE or culture confirmation was 5.5 days (range, 2 to 18 days). Several specimens required subpassage, thereby extending computer finalized reporting times. No pattern was identified between viral serotypes and isolation or detection rates among the enterovirus strains within our patient population (data not shown).

Several researchers have recently attempted to address the efficacy of the Ag-CCA system as a methodology to improve enterovirus detection in the clinical setting. Klespies et al. (4) using a MAb blend of clones 2E11 and 9D5 (Chemicon), reported a 93% detection rate among frozen clinical specimens 64- to 72-h post-shell vial inoculation; Isolation in TCs occurred at a rate of 51% during the same period. Both MRC-5 and RhMK shell vials, as well as TCs, prepared in house, were used within 5 days of seeding. Bourlet and coworkers (1) reported a sensitivity of 77.8% 18 h postinoculation among virion extracts from 180 frozen stool specimens, using freshly seeded (≤4 days old) HEL (human fibroblast) or KB (nasopharyngeal carcinoma) cells in 96-well plate centrifugation cultures. Van Doornum and De Jong (12), using refrigerated (4°C) stool and CSF, reported an enterovirus detection rate of 57% after 2 to 3 days in freshly seeded shell vial cultures. As indicated above, two studies utilized frozen specimens, while all three used in-house-prepared culture systems. The high enterovirus detection rates reported by Bourlet et al. (1) and Klespies et al. (4), as well as that reported to a lesser extent by Van Doornum and De Jong (12), might not be reflective of what may occur in the routine clinical setting when using commercially supplied cell cultures and field specimens containing reduced enterovirus titers (viz., RS versus stool extracts) (5). The testing protocol described in the present study (i.e., the testing of freshly collected swab specimens and the use of commercially prepared shell or “dram vial” cultures) most closely represents that which is commonly performed in the clinical virology or microbiology laboratory setting.

Immunoreagent 2E11 has been suggested to cross-react with reovirus type 3 (REO 3), hepatitis A virus (HAV), and some strains of astroviruses, as well as, to a much lesser extent, rhinoviruses (13; Pan-Enterovirus 2E11 package insert, Chemicon International, Inc.). Except for rhinovirus, growth of REO 3, HAV, and astrovirus in RhMk cells would not be expected. As observed in the current study, furthermore, background staining, perhaps reflecting the presence of exogenous low-level non-enterovirus antigen, failed to produce the characteristic (enterovirus) immunofluorescent signal described earlier (Fig. 1). As reported in the present work, the development of the enterovirus CPE coupled with immunofluorescent antibody (IFA) confirmation subsequent to Ag-CCA strongly suggests the validity of the Ag-CCA–immunoreagent 2E11 assay as an applicable technology for rapid enterovirus detection in the general patient population.

In summary, the data from our study not only suggest a superiority of enterovirus Ag-CCA to cell culture regarding turnaround time, but identify the efficacy of reagent 2E11 under field conditions. In consideration of assay sensitivity and the important clinical relevancy of test turnaround time, an AG-CCA (shell vial) postinoculation incubation period of 48 h is suggested. Nevertheless, some laboratorians may choose to extend Ag-CCA incubation times to provide improved positivity rates (e.g., 90% sensitivity after 4 days). Finally, primary RhMk and MRC-5 cultures should be retained in the laboratory's cell culture armamentarium. These cell types may not only detect enteroviruses missed by Ag-CCA, but permit the establishment of a culture collection for subsequent evaluation testing or, should the need arise, for investigation of interactions on the virus-cell level.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We appreciate the excellent technical assistance of Leon H. Falk, Madhavi Lotlikar, and Mark Bornfreund. We also appreciate H. P. Lipson's proofreading the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bourlet T, Gharbi J, Omar S, Aouni M, Pozzetto B. Comparison of a rapid culture method combining an immunoperoxidase test and a group specific anti-VP1 monoclonal antibody with conventional virus isolation techniques for routine detection of enteroviruses in stools. J Med Virol. 1998;54:204–209. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9071(199803)54:3<204::aid-jmv11>3.0.co;2-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chonmaitree T, Ford C, Sanders C, Lucia H L. Comparison of cell cultures for rapid isolation of enteroviruses. J Clin Microbiol. 1988;26:2576–2580. doi: 10.1128/jcm.26.12.2576-2580.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Engler H D, Preuss J. Laboratory diagnostics of respiratory virus infections in 24 hours by utilizing shell vial cultures. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:2165–2167. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.8.2165-2167.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Klespies S L, Cebula D E, Kelley C L, Galehouse D, Maurer C C. Detection of enteroviruses from clinical specimens by spin amplification shell vial culture and monoclonal antibody assay. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:1465–1467. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.6.1465-1467.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koneman E W, Allen S D, Janda W M, Schreckenberger P C, Washington C W., Jr . Color atlas and textbook of diagnostic microbiology. 5th ed. New York, N.Y: Lippincott; 1997. pp. 1177–1293. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lipson S M, Costello P, Agins B D, Forlenza S, Szabo K. Enhanced detection of cytomegalovirus in shell vial culture monolayers by pre-inoculation treatment of urine to low-speed centrifugation. Curr Microbiol. 1990;20:39–42. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lipson S M. Neutralization test for the identification and typing of viral isolates. In: Isenberg H D, editor. Clinical microbiology procedures handbook. Vol. 2. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1992. pp. 8.14.1–8.14.8. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rotbart H A. Pleconaril treatment of enterovirus and rhinovirus infections. Infect Med. 2000;17:488–494. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith T F. Picornaviruses. In: Howard B J, Keiser J F, Smith T F, Weissfeld A S, Tilton R C, editors. Clinical and pathogenic microbiology. St. Louis, Mo: Mosby; 1994. pp. 801–805. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Strongin W. Sensitivity, specificity, and predictive value of diagnostics test: definitions and clinical applications. In: Lennette E H, editor. Laboratory diagnosis of viral infections. New York, N.Y: Marcel Dekker, Inc; 1992. pp. 211–219. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Trabelsi A, Grattard F, Nejmeddine M, Aouni M, Bourlet T, Pozzetto B. Evaluation of an enterovirus group-specific anti-VP1 monoclonal antibody, 5-D8/1, in comparison with neutralization and PCR for rapid identification of enteroviruses in cell culture. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:2454–2457. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.9.2454-2457.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Van Doornum G J J, De Jong J C. Rapid shell vial culture technique for detection of enteroviruses and adenoviruses in fecal specimens: comparison with conventional virus isolation method. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:2865–2868. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.10.2865-2868.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yagi S, Schnurr D, Lin J. Spectrum of monoclonal antibodies to coxsackievirus B-3 includes type- and group-specific antibodies. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:2498–2501. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.9.2498-2501.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Young P P, Buller R, Storch G A. Evaluation of a commercial DNA enzyme immunoassay for detection of enterovirus reverse transcription-PCR products analyzed from cerebrospinal fluid specimens. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:4260–4261. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.11.4260-4261.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]