Introduction

Although the term nephrocardiology, or in some instances cardionephrology, has been sporadically used in the medical literature (1,2), its implication has been mainly limited to cardiorenal syndrome and cardiac complications of CKD. Moreover, it has not consistently implied the same denotation in its different appearances and, until recently, it had never been clearly described as a medical discipline with a defined scope (3,4).

Despite the importance of cardiorenal syndrome and cardiac complications of CKD, the interaction between nephrology and cardiovascular medicine is much broader and includes important subjects that are not well addressed in either of the two specialties (3). With the advancement of nephrology and cardiovascular medicine and the emergence of new diagnostic, monitoring, and therapeutic modalities that interact with the conditions related to the other specialty, “nephrocardiology” should be established as a subspecialty.

This article presents a brief overview of the evolution of cardiorenal syndrome, followed by definition of nephrocardiology and demonstration of its extent beyond cardiorenal syndrome and examples of its significance.

The Cardiorenal Syndrome

The understanding of cardiorenal syndrome has advanced remarkably in recent years. Classifying it into five categories based on acuteness versus chronicity and on its initiating point (heart versus kidney versus a systemic disease) (5) was an important step toward emphasizing the complexity of its pathogenesis compared with prior understanding. However, the practicality of that classification system was unclear, as there were no well-established cutoff points between normalcy and failure of heart or kidney function; neither was there a practical way to determine which organ system passed that nonexistent cutoff point first, so as to be considered the originator of the process. Furthermore, even if it was possible to recognize the starter of the cardiorenal syndrome’s complex network of events, the value of doing so in clinical practice was uncertain.

Therefore, the next step was taken with the introduction of a practical classification system (6), which instead of indicating the initiating organ, signified the “dominant” clinical presentation at any point in time. By classifying cardiorenal syndrome into the following seven categories, it specifies the clinical finding that needs to be “addressed first”: hemodynamic; uremic; vascular; neurohormonal (including electrolytes and acid-base disorders); anemia and iron metabolism; mineral metabolism; and malnutrition-inflammation-cachexia. This classification system can help clinicians streamline a patient’s care plans over the course of the illness and communicate their findings and management plans among themselves (7). By demonstrating the broadness and complexity of the pathophysiologic mechanisms and clinical presentations, this classification system also underscores the necessity of having a “nephrocardiologist,” with a comprehensive knowledge of both nephrological and cardiovascular aspects of cardiorenal syndrome and their complicated interconnection.

Interaction between Nephrology and Cardiovascular Medicine Beyond Cardiorenal Syndrome

To understand the extent of the interaction between nephrology and cardiovascular medicine, one should note that nephrology is not limited to “kidney diseases.” Many conditions such as electrolyte and acid-base disturbances, hypertension, and irregularities of water homeostasis are within the realm of nephrology, while they are not “kidney diseases.” Interestingly enough, those conditions have extensive multidirectional interactions with various cardiovascular diseases. Similarly, cardiovascular medicine is beyond “heart disease.” Therefore, in this definition of nephrocardiology, instead of kidney disease, “nephrology-related conditions” is used as a broader term. Similarly, it refers to “cardiovascular diseases” rather than heart diseases.

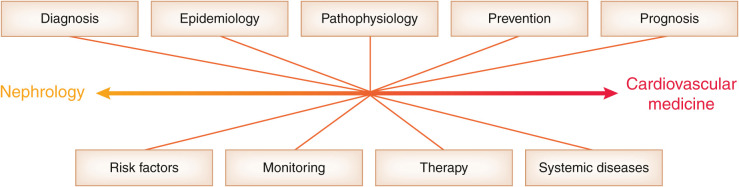

Furthermore, each of the two entities, nephrology-related conditions and cardiovascular diseases, can interact with the other from the standpoints of pathophysiology, epidemiology, risk factors, prevention, diagnosis, prognosis, monitoring, and therapy. Each of these aspects are further classified and elaborated as pillars of nephrocardiology (3). Additionally, nephrocardiology should also incorporate the relevant aspects of systemic diseases that cause both cardiovascular and nephrology-related conditions.

Therefore, nephrocardiology is defined as the study of the interaction between nephrology and cardiovascular medicine, which is the multidirectional interplay of cardiovascular diseases and nephrology-related conditions from the standpoints of pathophysiology, epidemiology, prevention, diagnosis, prognosis, monitoring, therapy, risk factors, and the systemic diseases that involve both nephrology-related conditions and cardiovascular diseases. Figure 1 demonstrates the elements of nephrocardiology according to this definition.

Figure 1.

The nine elements of the interaction between nephrology and cardiovascular medicine that compose the subject matter of nephrocardiology. Each of these elements can be viewed from different standpoints (see text for an explanation and examples).

Given the intertwined crosstalk between the two groups of conditions, any patient with a cardiovascular disease has one or more nephrology-related conditions and vice versa, which may be undiagnosed. These comorbidities require further study, and having specialists familiar with details of those interactions is crucial in complicated cases.

Examples of Nephrocardiology Topics

Additional examples of the nine elements of nephrocardiology are given below, which further demonstrate the complex and multidirectional interconnection between nephrology and cardiovascular medicine.

Pathophysiology.

Pathogenesis of sudden cardiac death can be different in patients with CKD compared with those without CKD (8), and pathophysiology of ischemic heart disease in CKD includes endothelial dysfunction, coronary artery medial calcification, ventricular remodeling, anemia, and inflammation, in addition to atherosclerosis, which is the primary pathogenesis in most patients without CKD.

Epidemiology.

Prevalence of pulmonary hypertension, arrhythmias, and ischemic heart and vascular diseases is higher in CKD, AKI has a higher incidence in patients with heart failure, and patients with CKD experience complications of ischemic heart disease at younger ages.

Prevention.

Prophylactic anticoagulation is challenging when atrial fibrillation and CKD coexist, statins and coronary interventions have limited prophylactic benefits in patients with advanced CKD, sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors have prophylactic impact on both the cardiovascular system and the kidney, and individualized AKI prophylactic measures should be considered before cardiovascular procedures that involve application of intravascular contrast material.

Diagnosis.

Diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction is challenging in the presence of CKD because of its atypical symptoms, elevated baseline serum troponin levels, and the concern about using diagnostic intravascular contrast agents.

Prognosis.

Glomerular filtration rate and proteinuria are prognostic indices for cardiovascular disease, and hyponatremia is a prognostic factor in heart failure.

Monitoring.

Monitoring of kidney function, acid-base status, and serum electrolytes is necessary following percutaneous cardiovascular procedures. Furthermore, in patients with heart failure, arrhythmias, and certain congenital cardiovascular anomalies, closer monitoring of volume status, electrolytes, and electrocardiography is indicated during and in between dialysis sessions. As another example, serum potassium and kidney function should be monitored after initiation and dose escalation of renin-angiotensin-aldosterone blocking agents.

Therapy.

Hemodialysis treatment is complicated in patients with ventricular assist devices (9). Hemodialysis is also associated with cardiovascular complications, such as myocardial stunning (10), and its arteriovenous fistula can exacerbate heart failure. Implantation of heart failure devices, cardiac transplantation, and percutaneous cardiovascular therapeutic procedures impact kidney function and may cause kidney failure. On the flip side, percutaneous vascular intervention may facilitate the management of renovascular diseases.

Risk factors.

There are common risk factors between cardiovascular diseases and nephrology-related conditions, such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, and obesity, while there are cardiovascular risk factors specific to CKD, e.g., uremic toxins, hyperphosphatemia, elevated fibroblast growth factor-23, and hyperparathyroidism.

Systemic diseases.

These include conditions that involve the kidney and cardiovascular system, such as autoimmune diseases, amyloidosis, Fabry’s disease, and ciliopathies.

A comprehensive explanation and examples of different aspects of the interplay between nephrology and cardiovascular medicine is presented elsewhere (3).

Conclusion

The interaction between nephrology and cardiovascular medicine, nephrocardiology, is broad, complex, and clinically important and includes subtleties that are not routinely discussed in either nephrology or cardiovascular medicine. Any nephrologist or cardiologist should be familiar with those topics, and a “nephrocardiologist” must master them. Nephrocardiologists should also lead additional research to further discover the extent of those interactions and to establish the optimal clinical approaches to those complexities.

Disclosures

The author has nothing to disclose.

Funding

None.

Acknowledgments

The content of this article reflects the personal experience and views of the author(s) and should not be considered medical advice or recommendation. The content does not reflect the views or opinions of the American Society of Nephrology (ASN) or CJASN. Responsibility for the information and views expressed herein lies entirely with the author(s).

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

References

- 1.Herzog CA: Congestive heart failure and chronic kidney disease: The cardiorenal/nephrocardiology connection. J Am Coll Cardiol 73: 2701–2704, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rangaswami J, Soman S, McCullough PA: Key updates in cardio-nephrology from 2018: Springboard to a bright future. Rev Cardiovasc Med 19: 113–116, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hatamizadeh P: Introduction to nephrocardiology. Cardiol Clin 39: 295–306, 2021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hatamizadeh P: Time to recognize nephrocardiology as a discipline. Cardiol Clin 39: xiii, 2021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ronco C, Haapio M, House AA, Anavekar N, Bellomo R: Cardiorenal syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol 52: 1527–1539, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hatamizadeh P, Fonarow GC, Budoff MJ, Darabian S, Kovesdy CP, Kalantar-Zadeh K: Cardiorenal syndrome: Pathophysiology and potential targets for clinical management. Nat Rev Nephrol 9: 99–111, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hatamizadeh P: Cardiorenal syndrome: An important subject in nephrocardiology. Cardiol Clin 39: 455–469, 2021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Makar MS, Pun PH: Sudden cardiac death among hemodialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis 69: 684–695, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roehm B, Vest AR, Weiner DE: Left ventricular assist devices, kidney disease, and dialysis. Am J Kidney Dis 71: 257–266, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McIntyre CW: Effects of hemodialysis on cardiac function. Kidney Int 76: 371–375, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]