Abstract

Although existing measures of religiousness are sophisticated, no single approach has yet emerged as a standard. We review the measures of religiousness most commonly used in the religion and health literature with particular attention to their limitations, suggesting that vigilance is required to avoid over-generalization. After placing the development of these scales in historical context, we discuss measures of religious attendance, private religious practice and intrinsic/extrinsic religious motivation. We also discuss measures of religious coping, well-being, belief, affiliation, maturity, history and experience. We also address the current trend in favor of multidimensional and functional measures of religiousness. We conclude with a critique of the standard, “context-free” approach aimed at measuring “religiousness-in-general”, suggesting that future work might more fruitfully focus on developing ways to measure religiousness in specific, theologically relevant contexts.

The last fifteen years mark an explosion in research examining religion, spirituality and health (Mills, 2002). What once was considered fringe pseudoscience has developed increasing sophistication and momentum as an emerging field in several disciplines including medicine, sociology and psychology (Koenig, McCullough, & Larson, 2001). Critics have challenged both the rigor of the science and the overall propriety of religion as a subject for health research and practice. (Lawrence, 2002; Sloan & Bagiella, 2002; Sloan, Bagiella, & Powell, 1999; Sloan et al., 2000). However, the best evidence to date suggests that weekly religious attendance is associated with longer life (McCullough, Hoyt, Larson, Koenig, & Thoresen, 2000; Strawbridge, Cohen, Shema, & Kaplan, 1997), lower physical disability (Idler & Kasl, 1997), faster recovery from depression (Koenig, George, & Peterson, 1998), and greater life satisfaction (Levin, Chatters, & Taylor, 1995). Furthermore, the magnitude of these associations is clinically relevant. For example, the 2–3 year increase in life expectancy associated with regular religious attendance is on par with the 3–5 year increase in life expectancy associated with regular physical exercise (Hall, 2006). There is growing consensus that the associations between health and religious practice constitute a valid and important field of scientific research (Contrada et al., 2003; Koenig et al., 2001; Powell, Shahabi & Thoreson, 2003; Thoresen & Harris, 2002;Wink & Dillon, 2003).

Unfortunately, as critics note, there is a tendency to overstate conclusions without nuance: Narrowly specific studies measuring associations between a limited health outcome and a particular aspect of religious practice are sometimes interpreted to mean that religion “in general” is good (or bad) for health (Shuman & Meador, 2003). This tendency for blunt interpretation is due in no small part to the fact that there is no clear consensus on how best to measure “religiousness” or “spirituality.” As with any empirical endeavor, meaningful findings depend on precise and accurate measurement, but as noted by Slater, Hall and Edwards (2001), the operative definitions of “religiousness” or “spirituality” are frequently imprecise and consensus regarding those definitions remains elusive. Furthermore, significant disagreement persists regarding the several different root-theories that ground varying approaches to measuring religiousness within and across the disciplines of psychology, sociology, theology and medicine. Consequently, the tools for measuring religiousness are of mixed quality, and the development of precise and acute measures of religiousness and spirituality remains a vexing problem (Fetzer/NIA, 1999a; Larson, Swyers, & McCullough, 1997).

Perhaps precisely because consensus remains elusive regarding definitions and theories, there are now over 100 psychometric instruments available to tap various dimensions of religiousness. Hill and Hood (1999) compiled a thorough, if somewhat overwhelming, compendium of many of these measures, and although it is not widely available, it remains the most complete resource for those interested in religious measurement. However, there is no comprehensive, concise, easily accessible review of religious measurement published in the medical, psychological or sociological literature that can equip readers unfamiliar with these measures to accurately interpret research findings based on these instruments. We aim to fill this gap. After placing the development of religious measurement in historical context, we turn to a review of the measures of religiousness most commonly found in the literature regarding religion and health, paying particular attention to their limitations. This review should also be useful to established researchers who now wish to add an assessment of religiousness to their existing protocols. Finally, and in addition to the review, we critique the standard, “context-free” approach that measures “religiousness-in-general” and argue that a better way forward might examine religiousness in specific, theologically relevant contexts.

The perspectives and opinions regarding these measures are admittedly biased, but they are informed by a deep knowledge of the existing research on religion and health. This is not a systematic review aimed at detailed discussion of the psychometrics of each instrument, though we do reference the literature in which such detailed description and analysis can be found. Rather, we focus on the measures most commonly used in the emerging literature regarding religion and health, and we list representative research for each measure, pointing to resources that might be useful for those interested in deeper reading. We offer this review as a tool for those unfamiliar with the field who desire a concise overview of the most common instruments with particular attention to their strengths and weaknesses.

RELIGIOUS MEASUREMENT IN HISTORICAL CONTEXT

The scientific study of religion traces its roots to the end of the 19th century with the seminal works of William James (1902) and Max Weber (1922) who helped develop both the psychology and the sociology of religion. However, the first substantial measurement tools were developed by the next generation of researchers in the post-war era. Most notable of these are the work of Allport & Ross (1950, 1967), King & Hunt (1967), Hood (1975), and Glock & Stark (1966). Although the research of this era is rich and sophisticated, parts of the discussion are influenced by cultural assumptions that perceived religion as either irrelevant (Rozin, 2001) or possibly pathological (Freud, 1927), and this limits its utility in the current context.

Research in religiousness receded in the 1970s, perhaps as a result of the secularizing cultural shifts in American society, but interest revived in the 1980s and 90s led by, among others, Gorsuch (1984), Gorsuch & McPherson, 1989), Pargament (1997), Levin (1994), Koenig et al. (1997), and Larson (1997). Emmons and Paloutzian (2003) offer a careful and helpful history of recent approaches to measurement in the psychology of religion, noting the recent trend toward investigating the positive psychology of various “virtues” like forgiveness or gratitude. Additionally, there has been a trend in favor of measuring “spirituality” rather than religiousness (Hatch, Burg, Naberhaus, & Hellmich, 1998; Underwood & Teresi, 2002). As described in another helpful review (Zinnbauer et al., 1999) religiousness is increasingly criticized as exclusive and overly concerned with “outward” practice, and this critique is partly motivated by the specter of coercive prosyletism such as the Spanish Inquisition, the 16th century European wars of religion or the Holocaust. On the other hand, “spirituality” is raised up as a “broader concept” that embraces all religious traditions in a more universal experience of transcendent “belief in a power apart from our own existence” (Hatch et al., 1998). However, the focus on spirituality as distinct from religiousness remains controversial (Thoresen, 1998; Zinnbauer, Pargament, & Scott, 1999), and as noted by Slater, Hall and Edwards (2001), operative definitions of both religiousness and spirituality differ between researchers and across disciplines, and the reader will observe that in the course of this review, the definitions of these terms shift in subtle ways to reflect the usage of the measures we describe.

Despite the increasing interest in measures of spirituality, the majority of measures used in health research focus on religiousness, and there have been two basic approaches in developing the most commonly used measures, one theoretical and the other empirical. The first and most common approach is theory-driven where instruments are designed to measure a theoretical aspect of religiousness such as “orthodoxy” (Hunsberger, 1989), “liberalism” (Stellway, 1973), or “prejudice” (Allport & Ross, 1967). The scope of these theories varies considerably, but most are narrowly focused on the theoretician’s area of particular interest, and the quality of the measure depends on the quality of the guiding theory. Accurate interpretation of the data generated from such theoretically driven measures requires substantial familiarity with the underlying theory on which they are based. Unfortunately, these measures are sometimes applied to medical or mental health research without adequate description of their theoretical foundations, and as such, it is very difficult for readers to judiciously interpret the significance of the findings reported.

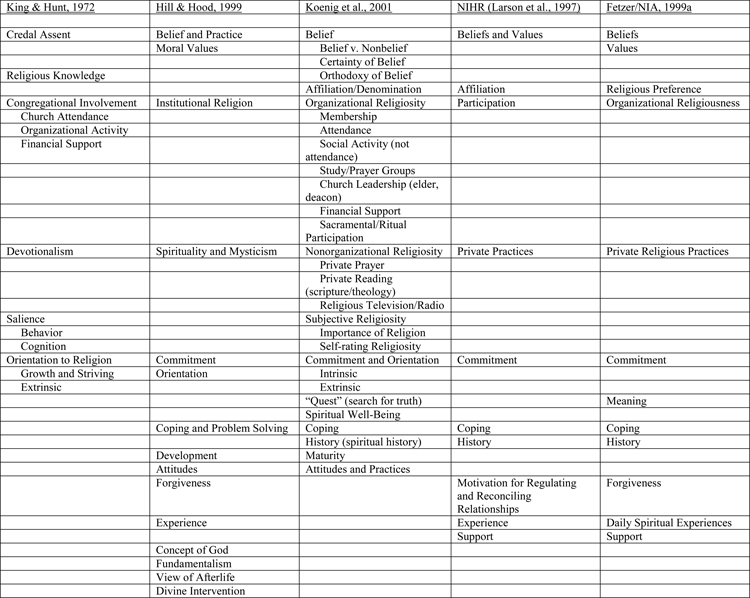

In an attempt to avoid the inherent subjectivity of theory driven measurement, King and Hunt (1967) pioneered the second focus of religious measurement by attempting to generate the theory directly from empirical observation. Using factor analysis of large numbers of religiously oriented questions, King and Hunt identified several dimensions of religiousness. Although the definition of relevant dimensions has changed slightly over time, most dimensions have stabilized through repeated analysis (King, 1966; King & Hunt, 1967, 1969, 1972, 1975). In fact, from both theoretical and empirical perspectives, it is now widely accepted that religiousness is a multidimensional concept, and although there remains considerable variety in the number and nature of those dimensions (see Figure 1), there is significant consensus on some (Fetzer/NIA, 1999a; Hill & Hood, 1999; King & Hunt, 1972; Koenig et al., 2001; Larson et al., 1997).

Figure 1:

Comparing Domains of Religiousness

Notes: Domains of religiousness from each scheme are arranged for easy comparison.

The majority of measures have been developed in an American context, and as such, there is a bias toward generally Christian and specifically Protestant patterns of religious practice, yet viewed as a whole, the existing theoretical and empirical instruments cover a broad scope of religious domains with impressive depth and sophistication. There are frequently several different instruments available for measuring any given domain. The array of available tools is sufficiently complete that Gorsuch (1984) argued that most future research can rely on existing instruments rather than developing new tools. Hill and Pargament (2003) were more cautious, recognizing that there are relevant aspects of religiousness for which no adequate measure exists, but they also worry that the development of religious measurement is becoming a research goal in and of itself independent of any downstream research agenda. They note that many of the existing measures are rarely used beyond the immediate context of their initial development and validation, and as such, they caution against developing new measures unless they are absolutely necessary for answering a research question of compelling clinical or theoretical relevance.

It is important to note that none of the early work on measuring religiousness was focused on health outcomes. Rather, most of the existing scales were developed to answer a specific question from a distinctly psychological, sociological or theological perspective. The application of these measures in medical research is most often post-hoc, and some investigators worry that the underlying theoretical constructs are not appropriate in the medical context. For example, most of the measures of religiousness have been developed in isolation from any theory of how the influence of religiousness might be causally linked to various health outcomes, and as such, they may not be sufficiently precise or powerful for meaningful research in health outcomes (Gorsuch, 1984, 1990). However, in the last ten years, several measures of religiousness have been developed for specifically medical settings (Fetzer/NIA, 1999a; Hays, Meador, Branch, & George, 2001; Holland et al., 1998; Kass, Friedman, Leserman, Zuttermeister, & Benson, 1991; Koenig et al., 1997; Peterman, Fitchett, Brady, Hernandez, & Cella, 2002). These newer instruments include functional measures of religiousness that seek to quantify those specific aspects of religiousness like “coping” or “support” that may mediate the purported “effect” of religiousness on health (Hill & Pargament, 2003). Such functional measures of religiousness are developed to test possible pathways for the causal influence of religiousness on various health outcomes. They are also more narrowly defined such that should an effect be demonstrated, it would be easier to develop an intervention that would supply the necessary kind of “coping”, “support” or other mediating process, even if it were divorced from its original religious context.

Despite such progress, it remains challenging to quantify aspects of human experience as broad and diffuse as religiousness. As Feinstein (2002) notes, medicine generally prefers “an exact answer to a diverted question rather than an imprecise or approximate answer to the direct question,” (p. 202) giving examples of how “the search for a suitable definition of excellent clinicians has often been diverted to the demand that they pass an appropriate certifying examination” (p. 202) Similar diversion marks the measurement of “quality of care” that focuses on the conveniently tallied managerial activities performed by physicians rather than the more nebulous virtues of caring such as empathy, concern and compassion that are not conveniently quantified. Religiousness is perhaps even more difficult to quantify, and it is not clear if any existing instrument captures the direct question of interest: Namely, “Are you religious, and if so, in what way?” Shuman and Meador (2003) note that empirical measures of religiousness run the risk of distorting their subject to such an extent that the phenomena they measure are no longer recognizable as religious in an theologically “faithful” sense, and to use such “faithless” measures may generate more confusion than clarity in the research regarding faith and health. The empirical, statistically driven approach to measuring religiousness cannot replace solid, theologically informed theory.

Precisely because it is so challenging to measure something as complex as religiousness, there is lively debate regarding the application and interpretation of these measures in medical research (Shuman & Meador, 2003; Sloan & Bagiella, 2002; Sloan et al., 2000; Zinnbauer et al., 1999). At the same time that Sloan et al (2000) argue that physicians should not engage the religious lives of their patients, Matthews (1998) suggests that refusing to do so approaches malpractice. Both Sloan and Matthews base their conclusion in the available data, but they dramatically disagree regarding the interpretation of that data. In order to properly interpret the data regarding the associations between religion and health, it is imperative that readers of this literature attend to the ways in which various measures of religiousness both capture and distort the religiousness they measure. The following review describes some of the more common approaches to measuring religiousness in an attempt to clarify what these instruments do and do not measure.

REVIEW OF EXISTING MEASURES

Religious Attendance and Participation in Organized Religious Activities

By far the most common measure of religiousness is self-reported attendance at religious services. This question is often classified as a measurement of “organizational religiousness” which concerns participation in institutional worship (church, mosque, temple) and involves a social valence. It is most often used as a single item question such as “How often do you attend Sunday worship services?” (Glock & Stark, 1966) but there have been several multi-item instruments tapping participation in bible studies, financial support of religious institutions and frequency of various activities like corporate prayer, singing, taking the sacraments or saying the liturgy (Fetzer/NIA, 1999a). Given its ease of use, single item measurements of religious attendance are perhaps the most prevalent in epidemiological data, and for reasons that are not entirely clear, these single item measures generate some of the best and strongest evidence for an association between religiousness and longer life (McCullough, Hoyt, Larson, Koenig, & Thoresen, 2000; Strawbridge, Cohen, Shema, & Kaplan, 1997), lower disability (Idler & Kasl, 1997), faster recovery from depression (Koenig, George, & Peterson, 1998) and improved sense of satisfaction (Levin, Chatters, & Taylor, 1995). Although Hummer, et al (1999) demonstrate some evidence of a dose-response relationship between increasing frequency of religious attendance (dose) and longer life (response), the associations are most consistently apparent when dichotomized to those who attend religious services less than once a week and those who attend once a week or more (Koenig et al., 2001; McCullough et al., 2000).

Despite the consistency of the epidemiological findings, there is continuing debate regarding what weekly attendance actually signifies. It obviously measures some sense of commitment to religious practice, and in the North American context, this most often implies some form of Christianity. However, attendance at organized religious events may simply function as a proxy for more “secular” pathways of healthy living such as social networks, belief structure, or the search for meaning. For example, the positive associations between religious attendance and health may be explained by the social connections established and maintained through religious communities, and for this reason, early studies tried to control for social involvement (eg. Strawbridge et al., 1997). Others have suggested that some of the association between attendance and health may be the result of a selection bias where, by virtue of the fact that only healthy people are able to get out of bed to go to church, religious attendance may simply be a measure of health (Levin & Vanderpool, 1987). However, Idler and Kasl controlled for baseline physical disability in their exemplary studies demonstrating that an observed association between religious attendance and longer life was independent of baseline physical disability (Idler & Kasl, 1997a, 1997b).

Of note, some researchers now suggest that earlier attempts to control for all these possible pathways may have been somewhat overzealous, obscuring important pathways through with the association between religiousness and health is mediated (Strawbridge, 2003). For example, it may be that religious communities order and nurture social support in unique ways, and it may be that it is precisely this kind of uniquely “religious” social support that mediates the observed associations between religious attendance and health outcomes. If the statistical analysis probing these associations controls away the contribution of social support, that analysis may in fact obscure the most important association between religious attendance and health outcomes. Consequently, there is growing consensus that future studies should make a clear distinction between confounding variables and explanatory variables. After controlling for appropriate confounders (age, race, sex), explanatory variables such as social support or coping strategies can be explored using mediation analysis or structural equation modeling to better elucidate the nature of influence of religious attendance on health. However, for reasons not completely understood, the increasingly sophisticated measurements of religiousness often yield weaker associations than the single-item assessment of religious attendance (McCullough et al., 2000). Religious attendance appears to measure something unique, independent and real, but it remains difficult to interpret.

Private Religiousness and Global Self-Assessments

Sometimes called “nonorganizational religiousness,” Private Religiousness taps those practices pursued independent from organized religious groups and includes private prayer, meditation or personal scripture study (Fetzer/NIA, 1999a; Lenski, 1965; Stark & Glock, 1968). These questions are phrased to detect the frequency of each activity ranging from never to several times a day, and they are analyzed both independently and grouped together as a composite measure of a single factor. Another common approach to measuring religiousness is the use of global self-assessments of religiousness or spirituality (Koenig, George, Meador, Blazer, & Dyck, 1994; Putney & Middleton, 1961). An example would be “To what extent do you consider yourself a religious person?” rated on a four point scale from “very religious” to “not religious at all” (Fetzer/NIA, 1999a) and psychometric properties for this question have been validated in the General Social Survey (Fetzer/NIA, 1999b). Although there is obvious face validity to these questions, compared to the data based on religious attendance, the existing health-related findings associated with private religious practice and global self-assessments of religiousness have been only weakly and inconsistently correlated with health outcomes1 (Koenig et al., 2001). It is not precisely clear why this might be, but there are several possible explanations. First, private activities might not tap the strong social networks organized around religious communities that are likely to be one of the strongest explanations for the associations between religion and health (George, Ellison, & Larson, 2002). Second, if the association between religiousness and health is built over time through extended exposure and practice, it may be “too little, too late” when people suddenly turn to private religious practice at the end of their life or in periods of health crises. Therefore, although there is evidence that private religiousness becomes more important as people age and become less able to physically attend corporate worship (Koenig et al., 2001), the relative brevity of exposure may weaken any expected association between private religiousness and health. Finally, precisely because private activities are private and do not require participation in observable organizations, such private activities may be over-reported by respondents.

We suggest that the primary weakness of both private religiousness and global self-assessments is their inherent subjectivity. The questions tapping these domains are often framed in non-specific terms, allowing respondents to define for themselves what they will report as “religious practice”, and this subjective definition is often free from any sense of accountability to the normative standards of organized religious groups. For example, one question from the Duke Religion Index (DUREL) states “How often do you spend time in private religious activities, such as prayer, meditation or Bible study” (Koenig et al., 1997). Although suggestive, these questions leave open the definition of “private religious activity.” Such privately defined religiousness may accurately describe the practice of our increasingly individualized American culture, but the subjectivity of the definition makes the concept diffuse, and therefore findings are difficult to interpret or generalize beyond the individual respondent. In order to interpret the meaning of these types of instruments, the question “Are you a religious person?” must be followed by some assessment of “In what way?” Unfortunately, most existing research does not take this crucial next step, and systematic attempts to do so are methodologically challenging.

Religious Motivation/Orientation: Intrinsic and Extrinsic

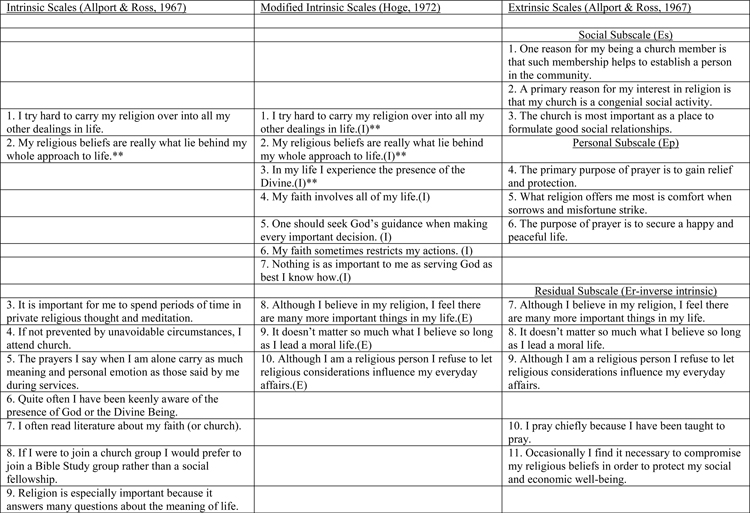

The distinction between intrinsic and extrinsic religiousness continues to be as controversial as it is influential. First proposed in the 1950s, Gordon Allport’s concept of intrinsic and extrinsic religion has shaped most subsequent empirical research in the psychology of religion (Kirkpatrick & Hood, 1990). Inspired to understand how religion is distorted by racial prejudice, Allport worked extensively on refining a distinction between “extrinsic” religion that is “used” for instrumental purposes (such as securing a construction contract through “religious” contacts) and “intrinsic” religion that is lived and practiced for its own sake rather than as a means to some ulterior motive. Although his writings manifest much deeper subtlety, the I/E distinction has been adopted and advanced in the simplified shorthand of “lived” versus “used” religion (Kirkpatrick & Hood, 1990). Because the I/E concept and scales are so commonly used in the literature of faith and health, it is worth considering the specific items that make up these scales: Figure 2 displays Allport and Ross’ (1967) items for measuring intrinsic and extrinsic religiousness along with a modified instrument for intrinsic religiousness developed by Hoge (1972) and adapted for use in the Duke Religion Index (Koenig et al., 1997). The extrinsic subscale is arranged according to Kirkpatrick’s (1989) factor analysis that identified three types of items that correspond with distinct aspects of “extrinsic” religiousness. The Es factor taps social motivations for religious activity. The Ep factor measures religious motivation rooted in personal gain, and the Er factor loads negatively on Allport and Ross’ intrinsic subscale suggesting that these items are really “reverse-scored” measures of intrinsic religiousness.

Figure 2:

Comparing Intrinsic and Extrinsic Religiousness

Notes: Original items are arranged to make comparison easier. The Intrinsic and Extrinsic items on Hoge’s scale are denoted as (I) or (E). The extrinsic items from Allport & Ross’ scale are arranged according to Kirkpatrick’s (1989) factor analysis.

Please note that the first two questions in both Intrinsic scales are identical. Note also that the Extrinsic questions in Hoge’s scale are identical to three items from Allport and Ross’ scale. Although questions 3–9 are unique to Allport & Ross’ intrinsic scale, they all score in an inverse relationship with the first three items on Kirkpatrick’s (1989) “Residual” subscale of extrinsic items (bottom third column).

**These three items were chosen for the Duke Religion Index because they are the highest loading items according to a principal factor analysis of 458 consecutively admitted medical patients (Koenig et al., 1997).

Despite its wide influence, the I/E distinction drew intense criticism from its initial proposal. Kirkpatrick and Hood (1990, 1991) describe this controversy in a thorough and probing review to include discussion of the continuing controversy regarding the absence of conceptual clarity in the definitions of intrinsic and extrinsic religious orientation. They also review the critique of Gorsuch (1984) who argues that because Allport and Ross’ scales contain several dimensions such as attitude, value or behavior, it is impossible to use these scales when investigating the interrelationships between such domains. They also review the problems inherent in the relative valuation of “good” intrinsic motivation compared to “bad” extrinsic motivation, pointing out that although not always obvious, the I/E model is value-laden, and precisely because those values are frequently obscured, the interpretation of I/E religious motivation is often distorted (Kirkaptrick & Hood, 1990; Zinnbauer et al., 1999). Others note that analysis of the factor structure of the scales raises questions about whether religious orientation ought to be measured using a single item (Gorsuch & McPherson, 1989), one scale (Gorsuch & McFarland, 1972; Hoge, 1972), or several scales (Kirkpatrick, 1989). Finally, although the I/E distinction has been applied to non-Protestant settings (Bernt, 1989; Fehring, Miller, & Shaw, 1997; Genia & Shaw, 1991), Cohen, Hall, Koenig and Meador (2005) have argued that the I/E distinction is culturally constrained by the individualism specific to the American Protestant context, and consequently, it may not be capable of accurately assessing normative religious motivation in more communitarian religious traditions like Roman Catholicism or Judaism.

Despite these critiques, the I/E paradigm is not without its champions. Masters (1991) offers a rebuttal to Kirkpatrick and Hood’s (1990) critical review, arguing that despite its weaknesses, the I/E paradigm provides continuing heuristic and theoretical value and should not be abandoned. Most of the critiques of the I/E paradigm focus on problems with the extrinsic subscale, and when used independently, there is wider consensus that the intrinsic subscale taps a valid and important aspect of religiousness, particularly in the American Protestant context where the intrinsic subscale is remarkably successful at identifying normative religious commitment and motivation. The continuing strength of the intrinsic subscale is supported by robust associations with various health outcomes (Koenig, et al., 1998; Watson et al., 2002) as well as validation in Muslim and Buddhist populations outside the United States (Tapanya, Nicki, & Jarusawad, 1997; Thorson, 1998; Watson et al., 2002). However, as noted above, it remains uncertain that the distinction between intrinsic and extrinsic religious motivation means the same thing to Thai Buddhists, Iranian Muslims or American Protestants. Buddhists and Muslims may have some capacity to read their own context into the I/E distinction, but the theory grew out of the Protestant worldview, and is likely most appropriate to this setting.

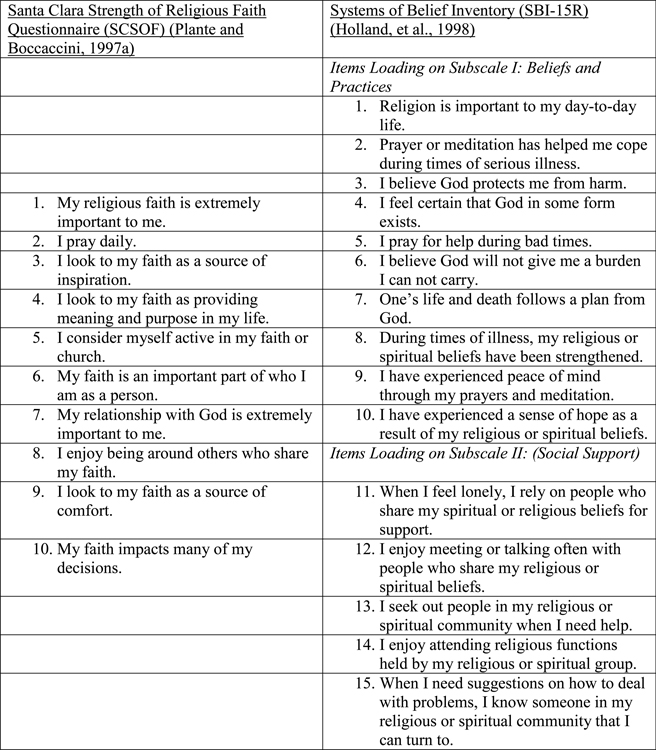

Given its wide use and fruitful findings in the study of religion and health, it is not likely that researchers will completely discard the I/E paradigm even though it is increasingly clear that theoretical and psychometric defects make it difficult to interpret the meaning of research based on these scales. Kirkpatrick and Hood (1990) argue that rather than continuing to tinker with the existing, flawed paradigm, researchers should develop stronger theories of religious motivation, belief and behavior. One promising development in this direction is Plante and Boccaccini’s (1997a, 1997b) 10-item Santa Clara Strength of Religious Faith Questionnaire (SCSOF) designed to measure the “strength” of religious faith regardless of denomination or affiliation (see Figure 3). Although Plante and Boccaccini explicitly place their work in the context of previous Intrinsic/Extrinsic religious theory, their scale attempts to clarify the theory by focusing on the unidimensional construct of “strength of faith.” The unidimensional construct was confirmed through factor analysis (Lewis, Shelvin, McGuckin, & Navratil, 2001), and tests of convergent validity demonstrate a strong correlation between the SCSOF and both intrinsic and extrinsic religiousness, but the patterns of correlation across other related measures of religiousness suggest that the SCSOF taps a dimension of religiousness both distinct and more unidimensionally cohesive than intrinsic or extrinsic religiousness.

Figure 3:

Promising New Scales: SCSOF and SBI-15R

Multi-Dimensional Measures of Religiousness

If nothing else, the controversy over the I/E distinction demonstrates some of the challenges associated with developing a comprehensive theoretical model for measuring religiousness. As noted earlier, King and Hunt attempted to derive their theory empirically using factor analysis of large numbers of religiously oriented questions to identify several dimensions of religiousness with established psychometric properties (King, 1966; King & Hunt, 1967, 1969, 1972, 1975). Subsequent research has focused on either isolating these dimensions with separate instruments, or alternatively, combining them into a composite scale. This multidimensional approach is now widely accepted even though there is no consensus on the number or definition of the relevant dimensions (Fetzer/NIA, 1999a; Hill & Hood, 1999; King & Hunt, 1972; Koenig et al., 2001; Larson et al., 1997). Figure 1 compares five different multidimensional constructs, and although there are common themes, the emphasis of each construct is significantly different.

King and Hunt’s scales have over sixty question items, making them impractically long for certain kinds of clinical research. In an attempt to make a clinically useful multidimensional instrument, Koenig, et al. (1997) developed the five item Duke Religion Index (DUREL) that assesses religious attendance (one item), private religious practice (one item), and intrinsic religiousness (three items, noted by asterisks in the second column of Figure 2). The initial psychometric properties were confirmed in a population of oncology patients (Sherman et al., 2000), and its ease of use is manifest in several recent studies that demonstrate correlations between DUREL scores and various health outcomes such as lower post ischemia adverse cardiac events (Krucoff et al., 2001), lower death anxiety (Roff, Butkeviciene, & Klemmack, 2002) and optimism in the setting of a cancer diagnosis (Sherman et al., 2001). However, its three dimensions cannot be combined into a single global measure of religiousness suitable for dividing samples into religious and non-religious groups.

In cooperation with the National Institute on Aging, the Fetzer Institute convened a working group of experts in 1995 to examine conceptual and methodological challenges in the measurement of religiousness. Twelve dimensions of religiousness were defined by expert consensus (see figure 1), and both long and short-form instruments were developed for each dimension. From these independent instruments, 38 items were assembled into a single, multi-dimensional survey validated in a sample of 1445 subjects from the 1998 General Social Survey. The psychometric properties are reported by the Fetzer/NIA working group (1999b) and Idler et al ( 2003). Although not yet widely used in medical research, the Fetzer/NIA Multidimensional Measurement of Religiousness/Spirituality may emerge as the new standard because it has such unprecedented validation in a population based survey. However, it is important to note that the 12 dimensions tapped by these 38 questions must be analyzed independently. Like the DUREL, the Fetzer/NIA multidimensional measure cannot be summed into a single global assessment.

Finally, the Spiritual Beliefs Inventory (SBI-15R) hybridizes the theoretical and empirical approaches to religious measurement in an attempt to add a spiritual domain to existing measures of quality-of-life (Holland et al., 1998). The authors started with a theoretical four-dimensional model of spiritual and religious belief and practice: 1) religious practices and rituals; 2) relationship to a superior being; 3) social support from a community sharing similar beliefs; 4) a sense of meaning derived from an existential perspective. They then developed 54 questions probing these four dimensions, administered them to large samples and used factor analysis to narrow their theory to two dimensions (social support and beliefs & practices) measured by only 15 items (see Figure 3). The original test population included both lay people and members of monastic orders, and summed together as a single global, but multidimensional assessment of religiousness, the scores accurately discriminated between these two groups with predictably different levels of religiousness. It has subsequently been validated in both German (Albani et al., 2002) and Hebrew translations, and in Israel it can discriminate between orthodox, religious nationalist, and secular Jewish populations (Baider, Holland, Russak, & De-Nour, 2001). Given it proven capacity to discriminate between religiously diverse subjects within a mixed sample, this measure deserves particular attention for future health research.

Functional Measures of Religiousness

Thus far, we have focused on measures that capture a global sense of religiousness in and of itself, discriminating between the “religious” and the “non-religious.” However, as noted in the historical overview, Hill and Pargament (2003) commend a recent trend that delineates concepts and measures of religiousness that would be functionally related to health. These measures are designed to assess various proposed pathways that might mediate the influence of religion on health, and examples include measures of religious well-being (Hungelmann, Kenkel-Rossi, Klassen, & Stollenwerk, 1996; Moberg, 1984; Paloutzian & Ellison, 1982), coping (Pargament, Koenig, & Perez, 2000), problem-solving (Pargament et al., 1988), support (Fiala, Bjorck, & Gorsuch, 2002; Krause, 1999), and struggle (Exline, Yali, & Sanderson, 2000; Pargament, 2001). Frequently, these measures attempt to assess the specifically religious aspects of previously established root-theories such as psychological attachment, motivation, strain or social interaction. Given the challenges involved in measuring global assessments of religiousness, the narrower focus of these measures may prove helpful in untangling the various positive and negative associations between religiousness and health.

However, there is reason to be cautious of functional measures of religiousness because they risk distorting the religiousness they measure in ways that would undermine the functional pathway they aim to study. To pursue religion because it is “good for your health” distorts religious self-understanding by subordinating the ultimate good (God) to a proximal good (health). Without doubt, some people do “get religion” hoping to “get better”, but most normative religious practice is motivated to be faithful rather than efficacious. To the extent that functional measures of religiousness are aimed at identifying the ways in which religion is “effective,” they may lose track of the necessary “faithfulness” responsible for any observed association between religion and health. That is to say that if research eventually proved beyond all doubt that some aspect of religiousness were good for health, there is no reason to expect that people motivated to become religious “for the health benefits” would eventually enjoy the proposed “benefit” because the religious practice so motivated would not be faithful in the way in which the association between religious practice and better health was originally observed. Furthermore, as Philip Rieff (1966) argues, American churches have adopted a predominantly therapeutic model of ministry, and as such, even the current, normative notions of faithful practice are captive to the assumption that religious practice should be therapeutically effective. Shuman and Meador (2003) argue persuasively that the therapeutic model of ministry is more informed by secular understandings than by religious self-understanding, and as such, much of the recent attempt to ascertain if “religion is good for your health” unwittingly conspires in a larger trend by which therapeutic imperatives distort faithful religious belief and practice beyond recognition. As Sulmasy (1997) suggests, the reason to learn about the religious practice of patients is not so much because “it works,” but because that practice is important to the patient. Functional approaches to religious measurement will likely elucidate important findings, but an exclusive focus of function may divert attention away from other, potentially more important ways in which religion is relevant to health and healthcare.

Religious Well-Being

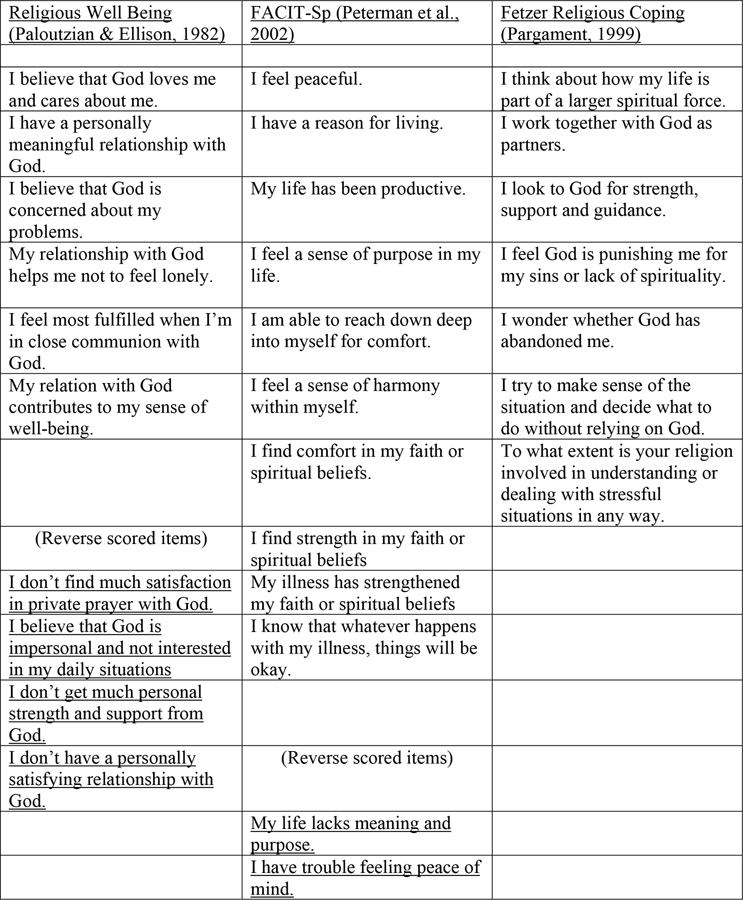

By far the most commonly used measurement in this category is religious well-being (Hill & Hood, 1999). The 20-item Spiritual Well-Being Scale (Paloutzian & Ellison, 1982) attempts to discriminate between “Religious Well-Being” (RWB) and “Existential Well-Being” (EWB). The EWB subscale taps general notions of purpose, satisfaction or experience such as “I feel that life is a positive experience” or “I feel good about my future.” Alternatively, each item on the RWB subscale contains the word “God” and taps specific religious meanings such as “My relationship with God helps me not to feel lonely” or “I believe God loves me and cares about me” (see Figure 4). By analyzing the RWB subscale independently, this instrument attempts to isolate the specifically religious component of a larger, secular theory of well-being, and RWB has been associated with some specific mental health outcomes such as increased hope and positive mood states (Fehring et al., 1997) or lower depression (Tsuang, Williams, Simpson, & Lyons, 2002). The more recent Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy—Spiritual Well-Being (FACIT-Sp) is designed to measure the spiritual aspect of quality-of-life (Brady, Peterman, Fitchett, Mo, & Cella, 1999; Peterman et al., 2002), and there has been some initial enthusiasm for this scale, but as can be seen in Figure 4, the FACIT-Sp includes items that are similar to both the RWB and EWB subscales, and as a result, it is not capable of discriminating between religious and non-religious aspects of well-being.

Figure 4:

Functional Scales

Although these measures are widely used, it is not clear if they tap something specifically “religious” or if they simply measure aspects of positive existential psychology like “deep inner peace” or “connection to all of life.” Koenig et al. (2001) suggest that measures of spiritual well-being assesses generally positive emotional states without tapping anything distinctly spiritual or religious, and to explore this possibility, Peterman et. al. (2002) compared FACIT-Sp scores with various mood states and found that the FACIT-Sp tapped a dimension distinct from mood that focuses on the human desire for meaning, purpose, inner strength and comfort. In a similar vein, Tsuang, et. al. (2007) studied a sample of 690 twins (345 twin pairs) and found that both SWB and EWB correlate with lower lifetime risks of depression and substance abuse along with increased health related quality of life (SF-36). However, in a hierarchical logistic regression, they found that EWB was the only significant predictor of these outcomes in the full model that included SWB as a covariate. These findings support the conclusion that although measures of spiritual or religious well being claim to measure a distinctly spiritual or religious phenomenon, they in fact measure a more generic and secular sense of meaning, purpose, strength and comfort. Although all of the RWB items and some of the FACIT-Sp items make explicit reference to God or some aspect of “the divine” (see Figure 4), we suggest that the items are phrased such that they primarily capture the more generic focus of each question, be it comfort, strength, peace or purpose. Religion is often relevant to the ways in which humans organize and shape their understanding of meaning and purpose, but the search for meaning and purpose need not necessarily be an explicitly religious endeavor, and in fact, meaning and purpose can be defined and sought without any reference to the divine. The roles of meaning and purpose in both health and healthcare are an important and perhaps neglected area of research, but it is not clear that the existing scales of spiritual well-being measure anything distinctly religious or spiritual, and as such, we are cautious of research using these measures are to examine the associations between religion and health.

Religious Coping

The other widely used functional measure of religiousness focuses on the various ways people “use” religiousness to cope with psychological, social and physical stress (Koenig et al., 1992; Pargament, 1999). Pargament is the leading researcher in this field, and initially described three styles of religious problem solving (Pargament et al., 1988). The “Self-Directing” style views problem solving as the responsibility of the individual, and God’s influence is viewed as providing the freedom and resources for individuals to direct their own lives. The “Deferring” style transfers the responsibility of problem solving to God rather than expecting individuals to actively to solve their own problems. The third “Collaborative” style views God as a partner with whom the individual works to together to solve problems. Growing out of this theory, Pargament et al. (1990) proposed six specific religious coping strategies developed from research within a sample of 586 subjects representatively drawn from 10 mid western churches from a range of Protestant and Catholic denominations. Rather than measuring religiousness in terms of beliefs, orientations (intrinsic/extrinsic) or behaviors (attendance, private religious practice), Pargament measures how religiousness functions as a response to a specific event or stressor. Through a principle factors analysis of this sample’s response to questions tapping 31 different religious coping activities, Pargament observed six distinct strategies that accounted for nearly all the variance in the sample. He calls the first strategy Spiritually Based Coping, and it that taps a loving, intimate partnership with God throughout the coping process in the form of emotional reassurance, positive framing of problems, accepting limits of personal control, and guidance in problem solving. The second strategy (Good Deeds) taps ways in which the individual shifts attention away from the stressful life event to a focus on living a better, more integrated, faithful or observant religious life. The third strategy (Discontent) copes with stress by expressing both doubt regarding the faith as well as anger and distance from God or the church. The fourth strategy, Interpersonal Religious Support, seeks material, social and emotional support from the clergy and members of the religious community. The fifth strategy (Plead) copes with stress through prayers for a miracle and bargaining with God. The final strategy, Religious Avoidance, includes activities that divert attention away from the life stressor through religiously oriented activities like reading the Bible or focusing on the afterlife.

Over the last 15 years, Pargament has expanded and refined his tools for religious coping, and an extensive review is available elsewhere (Pargament, 1997). Working with researchers interested in religion and health, Pargament et al. (2000) later developed a 105 item scale that assesses 21 religious coping methods (RCOPE), and an abbreviated 21 item Brief RCOPE (Pargament, Smith, Koenig, & Perez, 1998) has been used in several studies examining religion and health to include studies of both mortality (Pargament, Koenig, Tarakeshwar, & Hahn, 2001) and multiple measures of physical and mental health such as depression, self-reported health, ASA classification, Activities of Daily Living, and Quality of Life (Koenig, Pargament, & Nielsen, 1998). Furthermore, seven of these items (listed in Figure 4) are included in the Fetzer/NIA multidimensional measure and were administered as part of the General Social Survey resulting in unprecedented validation in a representative, population based sample (Pargament, 1999). There has also been some success in adapting the approach to non-Christian contexts with initial validation in Hindu samples (Tarakeshwar, Pargament, & Mahoney, 2003). Unlike measures of spiritual well-being, Pargament’s measures of religious coping maintain obvious face validity for assessing distinctly religious phenomena, and his research explores the religious component of coping that is conceptually related to larger, root theories of coping, but empirically distinct from purely secular coping strategies (Koenig, Pargament, & Nielsen, 1998). However, as we have already argued with any functional measure of religiousness, we caution readers interpreting the data regarding religious coping to be circumspect of the therapeutic implications of these findings.

Dimensions of Religiousness less Frequently Measured

The measures of religiousness reviewed above account for the majority of studies investigating the associations between health and religiousness, but this review is not comprehensive. Many diverse approaches to measurement have been developed by theologians, sociologists and psychologists. What follows is only a sampling of the less common dimensions of religiousness that may be relevant to the study of health. They are chosen to provide an understanding of different approaches to religious measurement, along with their attendant strengths and weaknesses.

Quest Scales.

Several measures have been developed to complement intrinsic and extrinsic religious motivation by focusing more on the process of religiousness than the result (Batson, 1976; Batson & Raynor-Price, 1983; Batson & Schoenrade, 1991a, 1991b; Batson & Ventis, 1982). These scales focus on those people who honestly face “existential questions in their complexity, while at the same time resisting clear-cut, pat answers” (Batson & Schoenrade, 1991a). Items include “I value my religious doubts and uncertainties” and “Questions are far more central to my religious experience than are answers.” In many ways, the concept of Quest, developed in the 1980s and 90s, is similar to the newer concept of “spirituality” in that both aim at a broader concept that transcends the exclusive practices of specific religious traditions. However, in so doing, measures of Quest run the same risk as measures of Spiritual Well-Being in that they may not end up measuring anything recognizably or distinctly religious. Furthermore, although Quest is theoretically related to and derived from the more predominant I/E distinction (Hill & Hood, 1999; Hood & Morris, 1985), it is not clear that it solves any of the previously mentioned problems with I/E motivation. For these reasons, we suspect that Quest scales will remain of only historical interest, and findings using Quest in the context of health research should be interpreted with awareness of the limitations discussed above regarding measures of both spiritual well being and I/E religiousness.

Beliefs and Values.

Much of the early work measuring religiousness attempted to quantify religious beliefs and values. Hill and Hood review more than thirty such scales (Hill & Hood, 1999), but none are these are widely used because they are either so vague as to measure only general human beliefs or so specific that they cannot be used outside a narrow religious context. For example, many of these scales probe belief in “life after death”, but this concept is not defined with sufficient precision to distinguish the Christian doctrine of bodily resurrection from either the Buddhist notion of reincarnation or from a more ethereal “afterlife” where a disembodied human soul continues to live in an exclusively “spiritual” plane of existence. Furthermore, by our assessment, most of these scales are theologically flawed, confusing and combining diverse theological concepts in ways that confound any conclusions they might draw. For example, the Religious Belief Scale (Martin & Nichols, 1962, 1967) contains several true/false questions such as “religious faith is better than logic for solving life’s important problems” or “the Bible is full of errors, misconceptions and contradictions.” From a theologically informed perspective, these questions present false dichotomies, and it may not be possible for faithful persons to answer them sincerely. Newer scales are more sophisticated (Idler, 1999a, 1999b), but interpretation remains complex because values and beliefs differ according the context of specific religious communities (Cohen, Siegel & Rozin, 2003; Cohen, Hall, Koenig and Meador, 2005).

Affiliation.

Religious affiliation is the one widely accepted attempt to address the specific context of religious belief and practice. It is usually assessed by asking the respondent to identify their philosophical, religious or denominational tradition. Some of the earliest work in health outcomes investigates differences between religious groups like the Amish (Hamman, Barancik, & Lilienfeld, 1981), Mormons (Enstrom, 1975), or Seventh Day Adventists (Wydner, Lemon, & Bross, 1959). The strict behavioral codes of these groups regarding alcohol, tobacco, sexuality and diet have clear and demonstrable health implications. However, within the largely Christian context of North America, denominational taxonomies employed by measures like the Fetzer/NIA are of limited value because the theological and historical conflicts from which denominations emerged are increasingly obscure or irrelevant to the life and practice of those individuals who belong to the denomination (Wuthnow, 1993). For example, an evangelical Methodist will likely share more in common with an evangelical Baptist than with the liberal or charismatic parishioners who sit in the next pew at the same Methodist church. Jensen (1998) illustrated this point by interviewing Indian Hindus and American Baptists about moral issues. He found that across cultures and religions “progressives” shared more with each other than they shared with “orthodox” members of the same culture or religion. Because denominationalism is a dying concept in the post-Christendom era, any successful assessment of religious context must move beyond denominational categories to reflect more accurately the theologically relevant traditions that constitute the contemporary religious landscape.

Maturity.

Religious maturity attempts to capture how religiousness develops over time. The seminal work of psychologist James Fowler (1981) argues that like cognitive or ethical development, faith “matures” in stages similar to other life-processes. Several scales are available to assess religious maturity (Benson, Donahue, & Erickson, 1993; Boivin, 1999; Dudley & Cruise, 1990; Hill & Hood, 1999; Stevenson, 1999), but unfortunately, they are limited for three reasons. First, like the I/E distinction, the very notion of “maturity” is value-laden, suggesting that some patterns of religious expression are better than others. Second, the categories of religious maturity are almost identical to secular psychological definitions of maturity, and although convergence of theories is often an indication of strength, in this case we suggest that psychological theory has trumped any theological self-definition of maturity. Measures of religious maturity are not likely to add any significant new knowledge to the secular psychological theory. Finally, most maturity scales are not widely applicable because their scope is focused narrowly on specific religious traditions, thereby making them unsuitable for use in more diverse samples (Hill & Hood, 1999).

History.

Whereas most measures of religiousness are only cross-sectional, point-estimates at one moment in time, measures of religious history attempt to quantify the cumulative exposure to religion over time. The best available and validated scale is the SHS-4 which inquires about religious practice at various times including childhood and middle age (Hays et al., 2001). For example: “When I was child, religion was a natural part of my life;” and “When I was 50, I was very involved in the church.” It also taps global assessments of life-long religious involvement such as “Overall, my religious life has helped me to persevere” or “At times, my religious life has caused me stress.” Alternatively, the Fetzer/NIA working group has developed a 23 item scale of religious history that assesses religiousness in each of the first seven decades of life: childhood, teenage, twenties, thirties, etc. (George, 1999). Such longitudinal assessments of religious history over time are an essential step forward, but as of yet, few studies have incorporated these measures in healthcare research. Furthermore, patterns of religious practice in the American context are changing such that people are much less likely to participate in the same religious tradition or denomination from cradle to grave. For example, some Roman Catholics become Episcopalians in reaction to the authoritarian structure of the Magisterium while at the same time, some Evangelicals convert to Roman Catholicism or Orthodoxy in search of a tradition with deeper roots in history and a more stable sense of order. The possible shifts in religious practice across a lifetime are growing both more complex and numerous, and although it is essential for research to measure the exposure to religion over time, none of the existing measures account for the ways in which the nature of religious participation may be qualitatively distinct at different stages of life (Hill and Pargament, 2003).

Experience.

Finally, several measures have assessed mysticism and religious experience (Hall & Edwards, 1996; Hood, 1975; Hood et al., 2001; Kass et al., 1991; Saur & Suar, 1993). This broad group of measures focuses on the numinous experience of transcendent presence. Rather than focusing on the content of religious doctrine, these scales try to measure religiousness through the experience of the divine. For example, Underwood and Teresi’s (2002) Daily Spiritual Experience Scale has been validated in three populations including the General Social Survey, and it assesses nine dimensions including wholeness, strength, connection with the transcendent, awe, and mercy and include items like “I experience a connection to all of life,” “I feel deep inner peace or harmony,” “I feel God’s love for me, directly or through others,” and “I am spiritually touched by the beauty of creation.” However, the nature of mystical experience is inherently private and unique, and consequently, it is difficult to construct an instrument that encompasses the nearly limitless range of experience that has been called religious or spiritual. As a result, and like the previously discussed measures of private religious practice, the items on these scales are often phrased such that each respondent subjectively interprets what each question might mean, and this flexibility makes it difficult to define precisely what the instruments measure. Religious experience is an important part of religiousness, but normative definitions of religiousness based exclusively on experience tend to be so subjectively privatized that they are difficult to generalize to or interpret within larger populations precisely because there is no agreement on the definition of what they measure.

CRITIQUE

Two recent commentaries have critiqued the current approaches to religious measurement. As discussed earlier, Slater, Hall, and Edwards (2001) note how the existing research on religious measurement is plagued by imprecise definitions of key concepts like religiousness or spirituality, and consensus regarding these concepts remains elusive. They also note that the designs of many measures are subject to ceiling effects that limit the variability within samples. They also note that in many populations, religious identity and behavior still enjoy social privilege and desirability, and for this reason, there may be a bias to over-report religious belief and practice. To illustrate this bias, they discuss the notion of “illusory spiritual health” that describes a subset of any population who appear “healthy” on self-report measures of religiousness, but in fact, when assessed clinically are found to be religiously or spiritually “distressed”. This suggests that self-perception of religiousness does not always correspond to the ways in which people act in relationship, and this discrepancy may confound research findings.

Hill and Pargament (2003) echo these observations as they make four recommendations for future work. First, they note that most measures rely on self-report, and they encourage the development of more objective alternatives such as unobtrusive observational techniques assessing religious practice. Second, they recommend the development of new measures of religious or spiritual outcomes such as faithfulness, peace, forgiveness, gratitude or “closeness to God”, and through these tools, they anticipate research programs aimed at distinguishing spiritual health from physical health. Although the goals of spiritual and physical health often coincide, they note that some people are willing to purchase spiritual health at the price of physical health. The lives of saints and martyrs provide rich examples of these kinds of choices, and research regarding religion and health should be prepared to measure the kinds of religious virtues for which people are willing to make significant sacrifice. Third, Hill and Paragment commend the few measures of spiritual history and development like the SHS-4, but as discussed earlier, they agree that more is needed to assess the aspects of spiritual change, transformation and even conversion. Finally, they note the need for more contextually sensitive measures of religiousness, noting that most existing measures assume a largely white, male, middle-class, Christian context, and joining Levin and Vanderpool (1987) they suggest that measures of religiousness must be expanded to accommodate the religious practice of different races, cultures and religions. We agree, but suggest that the problem goes even deeper.

Context is Critical

Although the empirical stream of religious measurement has developed and supported a multidimensional model of religiousness that resists global assessments, much of the research on religion and health assumes that “religiousness-in-general” actually exists. As such, it attempts to measure the intensity of religiousness (belief, experience, strength, value, etc) in order to locate people on a continuum between “very religious” and “not religious,” and having done so, the research then attempts to determine if religiousness-in-general is associated with a specific health outcome. This approach lumps together in the same group all people of intense religiousness without regard to the particulars that distinguish intensely religious Jews, Christians, and Buddhists. The theoretical assumption driving this work is that it does not matter so much what you believe as long as you do believe.

The assumption that belief is important independent of its content may explain some of the rising preference for the concept of “spirituality” as more inclusive and universal than “religiousness”. In this fairly recent distinction in definition, spirituality concerns the form, but not the content of belief, and consequently it is more individualistic and less socially organized. As summarized in the Fetzer/NIA report:

Religiousness has specific behavioral, social, doctrinal, and denominational characteristics because it involves a system of worship and doctrine that is shared within a group. Spirituality is concerned with the transcendent, addressing ultimate questions about life’s meaning, with the assumption that there is more to life than what we see or fully understand. Spirituality can call us beyond self to concern and compassion for others. While religions aim to foster and nourish the spiritual life—and spirituality is often a salient aspect of religious participation—it is possible to adopt the outward forms of religious worship and doctrine without having a strong relationship to the transcendent. (Fetzer/NIA, 1999a)

In other words, it is possible to be spiritual yet not religious, religious yet not spiritual.

By this definition, spirituality claims to be an almost universal human experience, and this universality should both improve the scientific goal of generalization and avoid the pitfalls of using research to pit religions against each other as more or less “healthy”. As discussed earlier, the measures of spirituality are frequently phrased in such a way that a Secular Humanist might score as “highly spiritual” because the items tap her deep commitment to her humanist philosophy and worldview. This approach has been described as content free (Kirkpatrick & Hood, 1990), functional (Gorsuch, 1984), or process (Hood & Morris, 1985), but we prefer context-free because it is not so much that such “spirituality” is devoid of content (by no means), but that it is often perceived to be freed from any wider context of belief, worldview or community in which it is historically rooted.

Unfortunately, context-free approaches to measuring religiousness-in-general or spirituality-in-general are vulnerable to over-generalization. As Kirkpatrick and Hood (1990) have suggested, it may be misleading to examine only “how” people believe without also considering “what” they believe, and Moberg (2002) argues that all measures of religiousness or spirituality designed for universal use will, by definition, embody a reductionism that constrains their capacity to detect the religious or spiritual phenomena of interest. While recognizing that all empirical research requires judicious abstraction and generalization, Moberg suggests that without close attention to the particularity of specific faith traditions, “universal” measures of spirituality override distinctive norms and contribute to the loss of verifiable knowledge.

This tension between generalizability and specificity is familiar to all health care researchers and clinicians. Although it is commonly taught in medical school that beta-blockers are effective medications for controlling blood pressure. However this knowledge about a class of drugs is not based on data testing the administration of beta-blockers in-general. Although it would be possible to administer a random assortment of beta-blockers to the study population, the well designed research on which the prescription of beta blockade is based tests specific compounds from the wider family (e.g. metoprolol). Conclusions about the wider class of beta-blockers may be drawn from subsequent meta-analysis of individual studies of specific compounds, but such specific studies must always precede the wider generalization. Likewise, we suggest that it is methodologically impossible to measure religiousness or spirituality “in-general” apart from the context of a particular spirituality or religion. Studying religion or spirituality “in-general” is like trying to perform a meta-analysis before collecting the necessary specific data.

This does not mean that spirituality is a useless concept. Most, if not all, humans do have a “life of the spirit” that yearns for meaning, value, purpose and community, and this search for meaning and value is what is often meant by contemporary notions of “spirituality”. This generic spirituality concerns the needs and aspirations of the human spirit, and as such, the subject of spirituality is critical to any complete notion of human nature. Indeed, all of the great religious traditions address the reality of the human life of the spirit with its needs for meaning, value and purpose—spirituality is an essential part of any adequate definition of religion. However, the recognition that people are all “spiritual” in their human search for meaning is like recognizing that all languages use similar patterns of grammar and syntax. There is much to learn from the study of linguistics, but the dry text of linguistic theory can never replace the living verse of Shakespeare. Language does not exist “in-general” because it is always encountered in particular forms, and therefore linguistics cannot constitute a universal language. Likewise, “spirituality” may be a sort of linguistics for faith, but any given “spirituality” is always expressed through the context of particular practices, and although there are many similarities shared between faith traditions, “spirituality” will never be a universal language of faith (Hall, Koenig, & Meador, 2004).

Spirituality as such does not exist on its own, and neither does religiousness-in-general, because both are always ordered toward some end. Christian spirituality is ordered toward and takes shape in the particular God revealed in the man Jesus. Muslim spirituality is ordered toward and takes shape in the particular God revealed by Mohammed. Humanist spirituality is ordered toward and takes shape in relationship to the “transcendent” revealed through the human spirit. In fact, if Bellah, et al.(1985) are correct, “spirituality” does not define something more universal, but precisely the opposite: millions of religions with only one member.

One person we interviewed has actually named her religion (she calls it her ‘faith’) after herself. This suggests the logical possibility of over 220 million American religions, one for each of us. Sheila Larson is a young nurse who has received a good deal of therapy and who describes her faith as “Sheilaism.” “I believe in God. I’m not a religious fanatic. I can’t remember the last time I went to church. My faith has carried me a long way. It’s Sheilaism. Just my own little voice...It’s just try to love yourself and be gentle with yourself. you know, I guess, take care of each other. I think He would want us to take care of each other.” (Bellah, Madsen, Sullivan, Swidler, & Tipton, 1985)

Few people are quite as bold as Sheila in naming their own religion, but this example of private spirituality exposes how it functions as a religion with only one member. Unfortunately, a “religion of one” is like a private language: It can mediate private experience, but without agreement on the terms of that language, it is powerless to share such experience with others. Although it may be fruitful to continue investigating the similarities between faith traditions, we know of no historical examples of generic “spirituality” surviving outside the context of specific religious faiths, and we contend that the field of religious measurement will not reach consensus regarding theory and definition until it recognizes the essential task of defining and assessing the specific context of any particular expression of religiousness or spirituality.

Establishing the Specific Context

Although recent studies embody a preference for context-free approaches to religious measurement, many of the earliest attempts to measure religiousness pursued the alternate strategy of developing a unique instrument for each specific religious context (Hill & Hood, 1999) and this strategy has been used more recently to develop scales specific populations like Latina Christians (Pena & Frehill, 1998) or American Hindus (Tarakeshwar et al., 2003). These measures do appear to tap some of the distinctive aspects of particular faith traditions, and we applaud these attempts. However, the expansion of such a paradigm for measurement would require a proliferation of measures specific to relevant faith traditions for each dimension of religiousness, and this would likely be unmanageable.

An alternative approach to measuring context-specific religiousness builds on the observation that the best context-free measures of religiousness are phrased in such a way that respondents can load their own particular context onto the scale. For example, the SBI-15 is validated in both American Christian (Holland et al., 1998) and Israeli Jewish (Baider et al., 2001) populations because the respondents can read their own religious contexts into the questions. Such studies can generate powerful, context-specific findings as long as the study population is religiously homogenous, and in fact, some of the best research addresses the problem of context by limiting the study sample to a single religious denomination (Krause, Ellison, Shaw, Marcum, & Boardman, 2001; Krause, Ellison, & Wulff, 1999; Krause, Tarakeshwar, Ellison, & Wulff, 2001).

However, the specificity of context-free measures starts to break down when applied to populations drawn from more than one faith tradition. For example, the monastic Christians and Orthodox Jews in the SBI-15 studies had similar scores (34 ± 7.5 and 29 ± 2.0 respectively) and if the populations were mixed, these very different religious contexts would be indistinguishable. The existing context-free measures of religiousness may be applied fruitfully to religiously mixed populations, but before doing so, there needs to be some way to sort respondents into appropriate groups that share theologically similar perspectives.

To date, the only attempts to sort people into similar theological contexts have relied on self-reported religious affiliation. Although it is possible to build models that examine the effects of the statistical interaction between denominational affiliation and the score on a context-free measure of religiousness, most studies treat religious affiliation as an independent dimension of religiousness, and few researchers attempt to analyze their primary outcomes according to the context of a specific religious affiliation. Furthermore, as we have already suggested, denominational taxonomies do not accurately reflect the relevant contours of the religious landscape (Wuthnow, 1993) where liberalism, secularism and other ideological worldviews are perhaps more theologically relevant than denominational tradition (Jensen, 1998). It remains to be seen if researchers can define the theologically relevant categories of faith context, but we contend that the future of religious measurement depends on such difficult work.

Once the theologically relevant categories of faith context are defined, it will be necessary to devise strategies for sorting respondents into these theologically relevant categories. By so doing, the scores on context free measures of religiousness can be analyzed according to the relevant contexts and thereby yield more interesting and meaningful findings. However, the process of sorting respondents into relevant categories will be complicated by the fact that people are not always self-consciously aware of the assumptions that make up their worldview (religious or otherwise). Therefore, any strategy for sorting subjects into relevant faith categories will likely require some aspect of observational techniques that might complement self-reported affiliation (Hall, 2002). For example, we are currently developing a sorting strategy that ask respondents a limited sequence of open ended questions regarding their concept of God, prayer and worldview. The responses to these questions are then recorded, transcribed and subjected to a form of narrative content analysis aimed at sorting subjects into similar faith traditions based on the way they speak about God, prayer and their worldview. Pilot data supports a proof of concept for this strategy (Hall, Koenig and Meador, forthcoming), and after defining theologically relevant categories, it appears to be at least possible that in the future, this approach could be combined with context free measures of religiousness to better examine the emerging data regarding religion and health.

Conclusion

Having reviewed the most common measures of religiousness as well as a representative sample of the breadth of approaches to this challenging task, it is evident that despite significant progress, much remains to be done. Measuring religiousness is complex and no single approach has yet emerged as a standard. Furthermore, interpreting these measures requires vigilance to avoid over-generalization. In particular, most existing measures of religiousness are limited by their attempt to quantify religiousness “in-general”. This context-free approach is methodologically flawed for the same reason that clinical trials cannot measure the effect of diuretics “in-general”. Future work might fruitfully focus on developing ways to sort respondents categorically into the context of theologically relevant traditions. By administering existing context-free measures of religiousness within the specific context of such traditions, the study of faith and health may generate more interesting and meaningful findings.

Acknowledgments

At several points in this manuscript we reference Koenig et al.’s (2001) Handbook of Religion and Health to support broad claims regarding the available evidence in the literature on religion and health. The Handbook provides detailed summaries of hundreds of articles, and is a good place for anyone to start with an interest in a particular area of health research. It also provides comprehensive references for deeper reading of the primary sources.

Footnotes

At several points in this manuscript we reference Koenig, et al’s (2001) Handbook of Religion and Health to support broad claims regarding the available evidence in the literature of the religion and health. The Handbook provides detailed summaries of hundreds of articles, and is a good place for anyone to start with an interest in a particular area of health research. It also provides comprehensive references for deeper reading of the primary sources.

References

- Albani C, Bailer H, Blaser G, Geyer M, Brahler E, & Grulke N (2002). [Religious and spiritual beliefs - validation of the German version of the “Systems of Belief Inventory” (SBI-15R-D) by Holland et al. in a population-based sample]. Psychotherapie, [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baider L, Holland JC, Russak SM, & De-Nour AK (2001). The system of belief inventory (SBI-15): a validation study in Israel. Psycho-Oncology, 10, 534–540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batson CD (1976). Religion as prosocial: Agent or double-agent? Journal for the Scientific Psychosomatik, Medizinische Psychologie, 52, 306–313. [Google Scholar]

- Allport G (1950). The individual and his religion: A psychological interpretation. New York: Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Allport G, & Ross J (1967). Personal religious orientation and prejudice. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 5, 432–443.Study of Religion, 15, 29–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batson CD, & Raynor-Price L (1983). Religious orientation and complexity of thought about existential concerns. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 22, 38–50. [Google Scholar]

- Batson CD, & Schoenrade P (1991a). Measuring religion as quest: 1. Validity concerns. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 30, 416–429. [Google Scholar]

- Batson CD, & Schoenrade P (1991b). Measuring religion as quest: 2. Reliability concerns. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 30, 430–447. [Google Scholar]

- Batson CD, & Ventis WL (1982). The religious experience. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]