ABSTRACT

Enzymatic degradation of collagen is of great industrial and environmental significance; however, little is known about thermophile-derived collagenolytic proteases. Here, we report a novel collagenolytic protease (TSS) from thermophilic Brevibacillus sp. WF146. The TSS precursor comprises a signal peptide, an N-terminal propeptide, a subtilisin-like catalytic domain, a β-jelly roll (βJR) domain, and a prepeptidase C-terminal (PPC) domain. The maturation of TSS involves a stepwise autoprocessing of the N-terminal propeptide and the PPC domain, and the βJR rather than the PPC domain is necessary for correct folding of the enzyme. Purified mature TSS displayed optimal activity at 70°C and pH 9.0, a half-life of 1.5 h at 75°C, and an increased thermostability as the NaCl concentration increased up to 4 M. TSS possesses an increased number of surface acidic residues and ion pairs, as well as four Ca2+-binding sites, which contribute to its high thermostability and halotolerance. At high temperatures, TSS exhibited high activity toward insoluble type I collagen and azocoll but showed a low gelatinolytic activity, with a strong preference for Arg and Gly at the P1 and P1’ positions, respectively. Both the βJR and PPC domains could bind but not swell collagen, and thus facilitate TSS-mediated collagenolysis via improving the accessibility of the enzyme to the substrate. Additionally, TSS has the ability to efficiently degrade fish scale collagen at high temperatures.

IMPORTANCE Proteolytic degradation of collagen at high temperatures has the advantages of increasing degradation efficiency and minimizing the risk of microbial contamination. Reports on thermostable collagenolytic proteases are limited, and their maturation and catalytic mechanisms remain to be elucidated. Our results demonstrate that the thermophile-derived TSS matures in an autocatalytic manner and represents one of the most thermostable collagenolytic proteases reported so far. At elevated temperatures, TSS prefers hydrolyzing insoluble heat-denatured collagen rather than gelatin, providing new insight into the mechanism of collagen degradation by thermostable collagenolytic proteases. Moreover, TSS has the potential to be used in recycling collagen-rich wastes such as fish scales.

KEYWORDS: collagenolytic protease, maturation, thermostability, halotolerance, β-jelly roll domain, PPC domain, fish scales

INTRODUCTION

Collagen is the most abundant protein in animals and widely distributed in various tissues such as skin, tendons, cartilage, bones, fish scales, and nematode cuticle (1, 2). Fibrillar collagens (e.g., types I, II, III, and XI) account for approximately 90% of mammal collagens and are assembled from collagen monomers, each comprising three intertwined polypeptide chains (e.g., two α1 and one α2 chains for type I collagen) of mainly repeating Gly-Xaa-Yaa triplets to form a right-hand triple helix (1). The triple helix is stabilized via interstrand hydrogen bonds, the stereoelectronic effects of hydroxylated prolines, intermolecular cross-links, and extensive hydration networks (3). Due to its tightly packed structure and insoluble nature, fibrillar collagen is highly resistant to proteolysis and can be efficiently hydrolyzed only by limited types of proteases such as mammalian matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and microbial collagenolytic proteases including true collagenases capable of degrading native collagens and other proteases with collagenolytic activities (4–6). Collagenolytic proteases of pathogens are important virulence factors via degrading extracellular matrix collagens of hosts, and those of environmental microbes play important roles in the global nitrogen cycling by hydrolyzing collagen-containing biomass (5). Microbial collagenolytic proteases have been widely used in food and meat industries, leather processing, medicine and cosmetic fields, cell preparation in the laboratory, etc., and enzymatic degradation is regarded as an eco-friendly approach for recycling collagen-rich wastes (6).

The extensively studied collagenases from Clostridium histolyticum (7–10) and Vibrio species (11–13) are metalloproteases of the M9 family. Additionally, several bacterial serine proteases belonging to the S8 (subtilisin) (14–17), S1 (chymotrypsin) (18), and S53 (sedolisin) (19) families, as well as some members of the U32 family without known catalytic type (20, 21), have been reported to be collagenolytic proteases. Most collagenolytic proteases contain a catalytic domain and at least one C-terminal domain, such as the collagen binding domain (CBD), the polycystic kidney disease (PKD) domain, the prepeptidase C-terminal (PPC) domain, the P-proprotein convertase domain (P_domain), and the β-jelly roll (βJR) domain (5). The CBDs of Clostridium collagenases (8) participate in collagen binding to facilitate collagen degradation by the catalytic domain. The PKD domain of collagenolytic protease MCP-01 from Pseudoalteromonas sp. SM9913 not only acts as a CBD but also swells insoluble collagen to improve the collagenolysis by the enzyme (15).

The degradation of collagen by thermostable collagenolytic proteases at high temperatures has the advantage of increasing the degradation efficiency because heat-denatured collagen is more susceptible to proteolysis and can minimize the risk of microbial contamination (22). To date, only a few thermophile-derived collagenolytic proteases have been characterized. The thermostable collagenolytic protease MO-1 from thermophilic Geobacillus collagenovorans MO-1 belongs to the subtilisin family and is active in a temperature range of 25–80°C, with an optimum at 60°C (23). The collagenolytic serine-carboxyl proteinase (kumamolisin-As) of thermoacidophilic Alicyclobacillus sendaiensis strain NTAP-1 is a member of the sedolisin family, and exhibits its optimum at 60°C and pH 3.9 (19). Despite lacking a CBD, kumamolisin-As possesses a substrate-binding groove with a preference for relaxed collagen molecule under high temperature and low pH condition (24). A collagenolytic serine protease from thermophilic Thermoactinomyces sp. 21E shows a high activity toward collagen at 60°C, but its gene remains unknown (25). Because heat treatment causes the conversion of collagen to gelatin, enzymatic degradation of collagen at high temperatures is considered to be related to the gelatinolytic activity of the enzyme (6). Indeed, the collagenolytic proteases from G. collagenovorans MO-1 and Thermoactinomyces sp. 21E exhibit higher gelatinolytic than collagenolytic activity (23, 25). However, MO-1 has a C-terminal CBD, implying that the binding of MO-1 to insoluble collagen substrates may contribute to collagen degradation by the enzyme (14). The mechanism of collagen degradation by thermophile-derived collagenolytic proteases remains to be elucidated.

Brevibacillus sp. WF146 is a thermophilic bacterium with an optimum growth temperature of approximately 58°C (26) and has the ability to utilize fish scale collagen (FSC) as carbon and nitrogen sources for growth (unpublished data). From strain WF146, an extracellular subtilisin-like protease (WF146 protease) (26–28) and an HtrA-like protease (HtrAw) (29) have been characterized. We have obtained a draft genome sequence of strain WF146 and identified another gene encoding an extracellular serine protease (named TSS) comprising a signal peptide, an N-terminal propeptide, a subtilisin-like catalytic domain, a βJR domain, and a PPC domain. In this study, recombinant TSS was produced in Escherichia coli, and its maturation was found to proceed in an autocatalytic manner. The mature TSS was characterized to be a novel thermostable and halotolerant protease with high collagenolytic but low gelatinolytic activity. The substrate preference of TSS, the ability of TSS in degrading fish scale collagen (FSC), as well as the roles of its βJR and PPC domains in enzyme folding and stability, collagen binding, and collagenolytic activity were investigated.

RESULTS

Bioinformatic analysis of TSS.

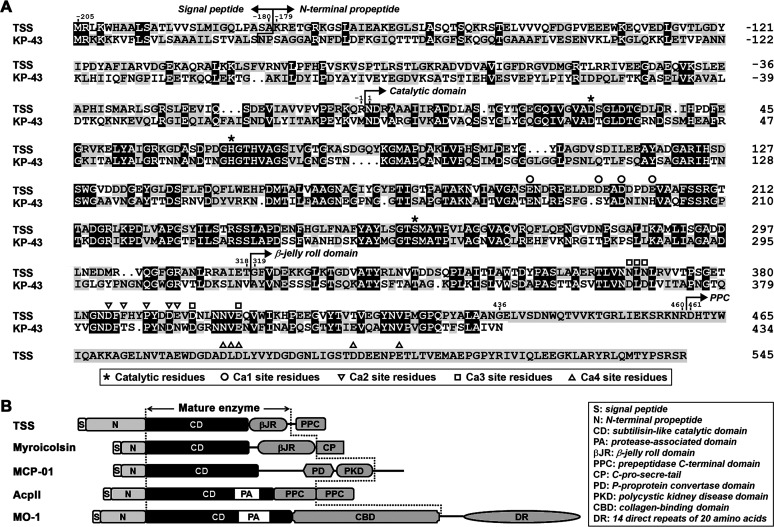

The open reading frame of TSS encodes a precursor (pre-TSS) of 750 amino acid residues. Sequence alignment analysis shows that pre-TSS comprises a signal peptide (Met−205 to Ala−180), an N-terminal propeptide (Lys−179 to Arg−1), a subtilisin-like catalytic domain (Asn1 to Thr318), a βJR domain (Gly319 to Gly436), a linker (Glu437 to Arg460), and a PPC domain (Asp461 to Arg545) (Fig. 1A). TSS shares low sequence identity (<20%) with reported subtilisin-like collagenolytic proteases including MO-1 (14), MCP-01 (15), AcpII (16), and myroicolsin (17) and has different domain organization (Fig. 1B).

FIG 1.

Primary structure and domain organization of TSS and its homologs. (A) Amino acid sequence alignment of TSS (OBR56241) with KP-43 (AB051423). The regions of the signal peptide, the N-terminal propeptide, the catalytic domain, the β-jelly roll domain, and the PPC domain are indicated. The catalytic residues and the Ca2+-binding residues (Ca1, Ca2, Ca3, and Ca4) are marked. (B) Comparison of the domain organization of TSS with those of characterized subtilisin-like collagenolytic proteases, including myroicolsin (AEC33275), MCP-01 (ABD14413), AcpII (AB505451), and MO-1 (AB260948). The regions of the mature enzymes are indicated (between the dashed lines).

Among characterized proteases, TSS exhibits the highest sequence identity (49% for catalytic domain and 44% for βJR domain) with the oxidatively stable alkaline serine protease KP-43 (30), although the latter lacks a PPC domain (Fig. 1A). KP-43 contains three Ca2+-binding sites (Ca1, Ca2, and Ca3), and most of the ligand residues at the three sites are conserved in TSS (Fig. 1A). Additionally, the PPC domain of TSS also contains a putative Ca2+-binding site (Ca4), of which the ligand residues are identical to those of the Ca3 site of KP-43 (Fig. 1A). Despite their sequence similarity, TSS differs from KP-43 in that TSS has a high content (16.4%) of acidic amino acid residues (Asp and Glu), and thus a low isoelectric point (pI) value of 4.38, while KP-43 has a pI value of 8.78. A homology modeling of TSS with mature KP-43 (comprising the catalytic and βJR domains) as the template revealed that most of the acidic residues of TSS are distributed on the enzyme surface (Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Meanwhile, 24 predicted ion pairs (5 salt bridges and 19 long-range ion pairs) were found in the catalytic and βJR domains of TSS, while 17 ion pairs (7 salt bridges and 10 long-range ion pairs) were found in mature KP-43 (Table S1). Most predicted ion pairs are located on the enzyme surface (21 for TSS and 14 for KP-43), and the other three (for each enzyme) reside at the interface between the catalytic and βJR domains (Table S1).

The maturation of TSS involves a stepwise autoprocessing of the N-terminal propeptide and the PPC domain.

In order to investigate the maturation process of TSS, the recombinant proform of this enzyme (pro-TSS) and its active-site variants (pro-S257A and pro-S257C), the C-terminal truncation variants (ΔP and ΔP’), the N-terminal propeptide deletion variant (ΔN), and the N-terminal propeptide (rN) were constructed (Fig. 2A) and produced in E. coli. A major band with an apparent molecular weight (AMW) of 78 kDa was detected in the total cellular protein (TCP) fraction of E. coli expressing pro-TSS, while pro-S257A was produced as a protein with an AMW of 100 kDa (Fig. 2B, upper panel). Meanwhile, both the 100- and 78-kDa products could be detected by immunoblot with antibody against His-tag (Fig. 2B, lower panel), which was fused at the C-terminus of pro-TSS or pro-S257A (Fig. 2A). When produced in E. coli, ΔN or its active-site variant (ΔN/S257A) was hardly detected by SDS-PAGE analysis but could be detected by anti-His-tag antibodies, showing an AMW of 78 kDa (Fig. 2B). These results suggest that the 78-kDa product of pro-TSS is derived from the proform by autoprocessing the N-terminal propeptide. It was noticed that the production of the 78-kDa ΔN or ΔN/S257A was accompanied by the appearance of many products with smaller AMWs (Fig. 2B), implying that in the absence of the N-terminal propeptide, ΔN or ΔN/S257A is unable to fold properly and susceptible to degradation by host proteases.

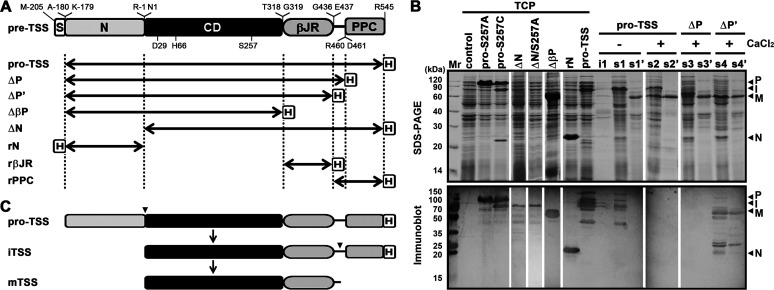

FIG 2.

Maturation process of TSS and its variants. (A) Schematic representation of the primary structure of TSS precursor (pre-TSS) and its derivatives. The signal peptide (S), the N-terminal propeptide (N), the catalytic domain (CD), the βJR and PPC domains, and the fused His-tag (H) are indicated. The locations of the active-site residues (D29, H66, and S257) and the N- and C-terminal residues of each region are shown. Double-headed arrows represent the regions of the recombinant variants of pre-TSS. (B) Production and processing of recombinant proteins. The total cellular protein (TCP) of E. coli harboring a blank vector (control) or producing a recombinant protein was subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblot analyses. The E. coli cells producing pro-TSS, ΔP, and ΔP’ were lysed by sonication in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) with (+) or without (−) 10 mM CaCl2. The insoluble (i1) and soluble (s1, s2, s3, and s4) fractions of the cell lysates, as well as the heat-treated (60°C, 15 min) soluble fractions (s1’, s2’, s3’, and s4’), were subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblot analyses. The bands corresponding to the proform (P), the intermediate (I), the mature form (M), and the N-terminal propeptide (N) are indicated. (C) Schematic view of the maturation process of TSS. Arrowheads indicate the autoprocessing sites.

It is well known that replacing the catalytic Ser residue with Cys greatly reduces enzymatic activity of subtilisins but does not eliminate their autoprocessing activities, such that the maturation process is blocked subsequent to the first cleavage of the N-terminal propeptide and the cleaved propeptide is not further degraded by the mature domain (27, 30). Therefore, we constructed the pro-S257C mutant to further verify that the autoprocessing event occurred in pro-TSS. In the case of pro-S257C, in addition to the 100- and 78-kDa products, a 22-kDa product was detected in the TCP fraction by SDS-PAGE but not by anti-His-tag antibodies (Fig. 2B), confirming that the 100-kDa proform is converted to the 78-kDa product by autoprocessing of the 22-kDa N-terminal propeptide. The size of the cleaved N-terminal propeptide (22 kDa) of pro-S257C was slightly smaller than that of rN (23 kDa) (Fig. 2B), most likely due to the presence of an additional His-tag in rN.

The 78-kDa product of pro-TSS was present in the soluble cellular fraction after cell disruption in a buffer without CaCl2, and a subsequent heat treatment at 60°C led to the conversion of the 78-kDa product into a 58-kDa product incapable of being detected by anti-His-tag antibodies (Fig. 2B, lanes s1 and s1’). When cell disruption was performed in a buffer with 10 mM CaCl2, both the 78- and 58-kDa products were detected in the soluble cellular fraction, and the 78-kDa protein was also converted to the 58-kDa product after the heat treatment (Fig. 2B, lanes s2 and s2’). These results imply that the C-terminal part of the 78-kDa product undergoes a further autoprocessing event, which could be accelerated by CaCl2. The C-terminal truncation variants ΔP and ΔP’ (Fig. 2A) were employed to probe the C-terminal cleavage site. After heat treatment of the soluble cellular fraction, a 58-kDa protein represented the major product in the sample of either ΔP or ΔP’ by SDS-PAGE analysis (Fig. 2B, lanes s3’ and s4’), suggesting that the PPC domain is not essential for cleavage of the N-terminal propeptide. Notably, the 58-kDa product of ΔP’ but not that of ΔP could be detected by anti-His-tag antibodies (Fig. 2B, lanes s3’ and s4’), indicating that the C-terminal processing occurs within the linker between the βJR and PPC domains (Fig. 2A), although the exact cleavage site(s) remains to be determined.

It is evident that the generation of the 58-kDa product, particularly in the heat-treated samples, was accompanied by the degradation of host proteins (Fig. 2B, lanes s1’, s2’, s3’, and s4’), suggesting that the 58-kDa product is the active mature form of the enzyme. It seemed that the active mature form also mediated the cleavage of the fused His-tag in the 78-kDa product of pro-TSS and the N-terminal propeptide-cleaved product of ΔP (∼ 61 kDa), which could not be detected by anti-His-tag antibodies (Fig. 2B, lanes s2 and s3). In addition, the immunoblot analysis also revealed some bands with AMWs larger than 100 kDa and smaller than 78 or 58 kDa (Fig. 2B), probably representing the aggregation forms and the degradation products of the enzyme.

The above results demonstrate that the N-terminal propeptide of pro-TSS is autoprocessed to yield the intermediate (iTSS), of which the PPC domain is then autoprocessed to generate the mature form (mTSS) comprising the catalytic and βJR domains (Fig. 2C). It is worth mentioning that the AMWs of pro-TSS (100 kDa), iTSS (78 kDa), and mTSS (58 kDa) are higher than their predicted molecular weights (79, 59, and 47 kDa, respectively), which is a common feature of proteins with a high content of acidic residues (31).

TSS is a Ca2+-dependent thermophilic alkaline protease with high halotolerance.

Purified mTSS was denatured by trichloroacetic acid (TCA) treatment and then subjected to SDS-PAGE analysis. As shown in Fig. 3A, in addition to the 58-kDa mTSS, two minor bands with AMWs of ∼34 and ∼25 kDa were also present in the purified sample (lane 1), and the two bands became more evident in the 5-fold concentrated sample (lane 2). When the concentrated sample was subjected to SDS-PAGE without TCA pre-treatment, mTSS displayed an AMW of 22 kDa and exhibited proteolytic activity in a gelatin overlay assay; meanwhile, the 34- and 25-kDa bands disappeared (Fig. 3A, lanes 3 and 5). The 58- and 22-kDa bands represent the denatured and folded forms of mTSS, respectively, and the compact folded form migrates faster than the denatured form during electrophoresis in the gel. For the 34- and 25-kDa bands, they are most likely the self-cleaved products of mTSS and may form a nicked enzyme in a folded state similar to intact mTSS under non-denaturing conditions.

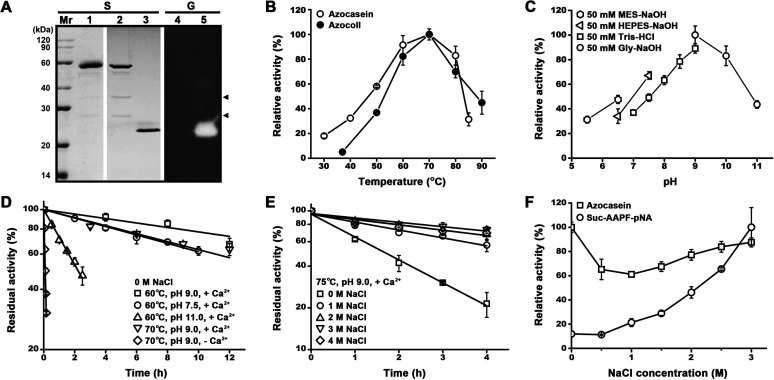

FIG 3.

Enzymatic property of TSS. (A) SDS-PAGE and gelatin overlay assay of purified mTSS. The purified enzyme sample (lane 1) and the 5-fold concentrated enzyme samples (lanes 2 to 5) before (lanes 3 and 5) or after (lanes 1, 2, and 4) TCA treatment were subjected to SDS-PAGE (S), followed by gelatin overlay assay (G). An equal amount of protein was loaded in each lane. Arrowheads indicate the self-cleaved products of mTSS. (B) Temperature dependence of enzyme activity. The enzyme activity against azocasein or azocoll was determined in buffer B (50 mM Gly-NaOH, 10 mM CaCl2, pH 9.0) at the indicated temperatures. Relative activity was calculated with the highest level of activity observed at 70°C defined as 100%. (C) pH dependence of enzyme activity. The azocaseinolytic activity was determined at 60°C in the buffers (containing 10 mM CaCl2) with different pH values as indicated. Relative activity was calculated with the highest level of activity observed at pH 9.0 defined as 100%. (D, E) Thermostability of the enzyme. The enzyme (2.5 μg/mL) was incubated at different temperatures in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) or 50 mM Gly-NaOH (pH 9.0 or 11.0) containing 10 mM CaCl2 and 0–4 M NaCl as indicated, and then subjected to azocaseinolytic activity assay at 60°C. The residual activity is expressed as a percentage of the initial activity. (F) Salinity dependence of enzyme activity. The proteolytic activity against azocasein or suc-AAPF-pNA was determined at 60°C in buffer B containing 0–3 M NaCl as indicated. Relative activity was calculated with the highest level of activity observed at 0 M (for azocasein) or 3 M (for suc-AAPF-pNA) NaCl defined as 100%. The values are expressed as means ± SDs from three independent experiments.

The optimal temperature for the activity of mTSS against azocasein or azocoll was determined to be 70°C (Fig. 3B). Using azocasein as a substrate, mTSS displayed pH optimum of 9.0 (Fig. 3C). In the presence of 10 mM CaCl2 at pH 9.0, mTSS retained more than 80% or 70% of the original activity after 8 h of incubation at 60°C or 70°C (Fig. 3D), and showed a half-life of 1.5 h at 75°C (Fig. 3E). At pH 11.0 and pH 7.5, the enzyme was also highly stable at 60°C in the presence of CaCl2, with half-lives of 2 h and more than 12 h, respectively (Fig. 3D). In contrast, in the absence of CaCl2 the half-life of mTSS decreased to 6 min at 70°C and pH 9.0 (Fig. 3D). When the residue Glu187 of the Ca1 site in the catalytic domain was replaced by Ala, the resulting variant E187A was completely inactivated after incubation at 70°C for 3 h, while mTSS retained 82.5% of the original activity under the same condition (Fig. 4D). These results suggest that TSS is a Ca2+-dependent thermostable alkaline protease.

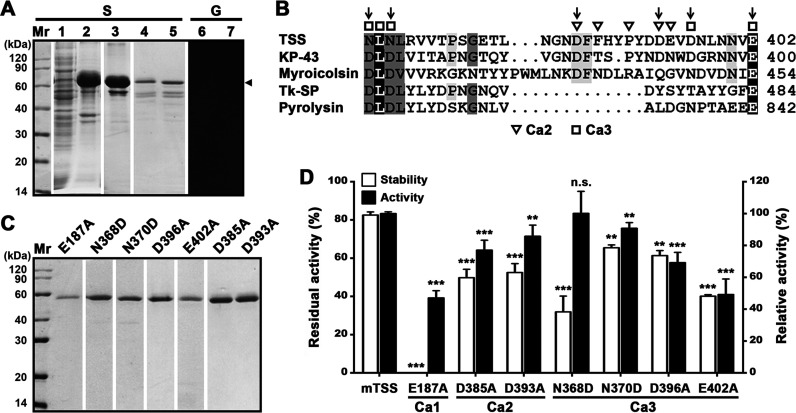

FIG 4.

Effects of the βJR domain and the Ca2+-binding sites on folding, stability, and activity of TSS. (A) Production and renaturation of ΔβP. The soluble (lane 1) and insoluble (lane 2) fractions of the cell lysate of E. coli producing ΔβP were separated by centrifugation. The recombinant ΔβP in the insoluble fraction was solubilized in 8 M urea and purified (lane 3), followed by renaturation to recover soluble ΔβP (lanes 4 to 7). The samples before (lanes 5 and 7) or after (lanes 1 to 4, and 6) TCA treatment were subjected to SDS-PAGE (S), followed by gelatin overlay assay (G). An arrowhead indicates the position of ΔβP on the gel. (B) Alignment of amino acid sequence around the Ca2+-binding sites (Ca2 and Ca3) in the βJR domain of TSS with those of KP-43 (AB051423), myroicolsin (AEC33275), Tk-SP subtilisin (Q5JIZ5), and pyrolysin (AAB09761). The residues serving as Ca2+-binding ligands are marked. Vertical arrows indicate the residues chosen for mutational analysis. (C) SDS-PAGE analysis of purified mature forms of the variants. (D) Comparison of the activities and thermostabilities of mTSS and its Ca2+-binding site variants. The azocaseinolytic activities were determined at 60°C in buffer B, and the relative activity was calculated with the activity of mTSS defined as 100%. For thermostability assay, the enzyme (2.5 μg/mL) was incubated at 70°C in buffer B for 3 h and then subjected to azocaseinolytic activity assay at 60°C. The residual activity is expressed as a percentage of the initial activity. The values are expressed as means ± SDs from three independent experiments (**, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; n.s., no significance).

Similar to haloarchaeal proteins, TSS contains a high content of acidic amino acid residues and has a low pI value, leading us to investigate the effects of high salinity on its stability and activity. After 4 h of incubation with 1–4 M NaCl at 75°C, mTSS retained approximately 60–80% of the original activity, which is much higher than that in the absence of NaCl (∼20%) (Fig. 3E), indicating that NaCl could enhance its thermostability remarkably. The salinity dependence of mTSS activity was determined in the presence of 0–3 M NaCl. Interestingly, the salt-dependence of azocaseinolytic activity of mTSS displayed an inverted bell-shape curve, i.e., the activity showed an initial decrease followed by an increase, with a minimum at 1 M NaCl (Fig. 3F). When N-succinyl-Ala-Ala-Pro-Phe-p-nitroanilide (suc-AAPF-pNA) was used as the substrate, the activity of mTSS continuously increased with rising salinity up to 3 M (Fig. 3F). These results suggest that TSS is highly halotolerant and its activity depends on both salinity and substrate type.

The βJR domain contributes to the folding, stability, and activity of TSS.

The PPC domain deletion variants (ΔP and ΔP’) could be produced as soluble forms and processed to active forms (Fig. 2), indicating that the PPC domain is not necessary for the folding, maturation, and activity of TSS. In contrast, the variant ΔβP, which lacks both the βJR and PPC domains (Fig. 2A), was present in the insoluble cellular fraction of E. coli (Fig. 4A, lanes 1 and 2). When solubilized in 8 M urea and purified, only a minor amount of soluble ΔβP could be recovered after renaturation (Fig. 4A, lanes 3 and 4). The soluble ΔβP displayed a larger AMW (65 kDa) than that of mTSS (58 kDa) comprising the catalytic and βJR domains (Fig. 4A and Fig. 3A), implying that the N-terminal propeptide has not been processed from ΔβP. Moreover, the ΔβP samples with and without pre-treatment by TCA displayed the same AMW and did not exhibit proteolytic activity by gelatin overlay assay (Fig. 4A, lanes 4–7), unlike the βJR domain-containing mTSS, which displayed different AMWs before and after TCA treatment (Fig. 3A). These results suggest that the βJR domain is required for correct folding of an active TSS.

To probe the roles of the βJR domain in stability and activity of TSS, we site-specifically mutated six residues at the Ca2 (Asp385 and Asp393) and Ca3 (Asn368, Asn370, Asp396, and Glu402) sites. (Fig. 4B). The thermostabilities and activities of purified variants (Fig. 4C) were examined. After heat treatment at 70°C for 3 h, the residual activities of the variants D385A, D393A, D396A, and E402A were significantly lower than that of mTSS; meanwhile, the four variants showed a decrease in azocaseinolytic activity (Fig. 4D). These results suggest that the Ca2 and Ca3 sites in the βJR domain contribute to the thermostability and activity of TSS.

The Ca3 site of TSS is conserved in the βJR domains (as in KP-43, myroicolsin, and Tk-SP subtilisin) and the PPC domain (as in pyrolysin) of some homologous proteases; however, two conserved Asp residues in this Ca2+-binding site of these homologous proteases are replaced by Asn residues (Asn368 and Asn370) in TSS (Fig. 4B). When the residue Asn368 or Asn370 of TSS was replaced by Asp, the resulting variant N368D or N370D showed a decrease in thermostability (Fig. 4D), implying that the introduction of a negatively charged carboxyl group into the Ca3 site destabilizes TSS.

TSS possesses high collagenolytic but low gelatinolytic activity at high temperatures.

Using azocoll, type I collagen, azocasein, and casein as the substrates, the activity of mTSS was compared with that of C. histolyticum collagenase (ChC). At 37°C, mTSS exhibited lower activity against azocoll (Fig. 5A) and type I collagen than ChC (Fig. 5B). When the temperature was increased from 37°C to 60°C, the activity of mTSS increased sharply by approximately 20- and 118-fold for azocoll (Fig. 5A) and type I collagen (Fig. 5B), respectively. In contrast, the activity of ChC against the two substrates decreased as temperature was increased from 37°C to 60°C (Fig. 5A and B), most likely due to the destabilization of the mesophilic ChC at elevated temperatures.

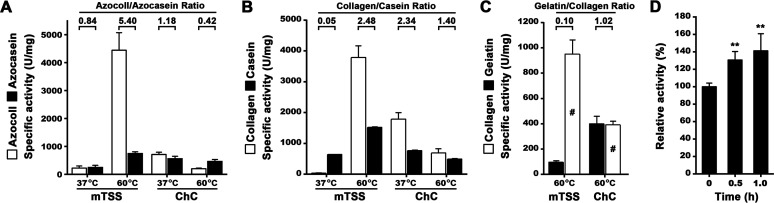

FIG 5.

Comparison of the activities of mTSS and ChC. (A, B, C) Specific activities of mTSS and ChC toward different substrates. The enzyme activities were determined at 37°C or 60°C in buffer B (for mTSS) or buffer C (50 mM Tris-HCl, 1 mM CaCl2, pH 7.5; for ChC) and were used for calculation of the azocoll/azocasein, collagen/casein, and gelatin/collagen ratios. The activities of the enzymes against type I collagen were determined by either water-soluble peptides quantification (B) or acid-soluble peptides quantification (C, indicated by “#”), as described in Materials and Methods. (D) Degradation of heat-treated type I collagen. Type I collagen was heat treated at 60°C in buffer B for different time periods, recovered by centrifugation, and then used as the substrate for measuring the activity of mTSS at 60°C in buffer B. The values are expressed as means ± SDs from three independent experiments (**, P < 0.01).

The activity ratios of mTSS and ChC for different substrates, namely, the azocoll/azocasein and collagen/casein ratios, were determined to compare the substrate preferences of the two enzymes at different temperatures. As shown in Fig. 5A and B, the azocoll/azocasein and collagen/casein ratios of mTSS at 60°C (5.40 and 2.48) were much higher than those at 37°C (0.84 and 0.05), indicating that thermal denaturation of collagenous substrates greatly facilitates their degradation by TSS. In the case of ChC, it showed lower azocoll/azocasein and collagen/casein ratios at 60°C (0.42 and 1.40) than at 37°C (1.18 and 2.34) (Fig. 5A and B), confirming that this enzyme acts as a native collagen-preferring collagenase. Moreover, the azocoll/azocasein and collagen/casein ratios of mTSS at 60°C were higher than those of ChC (5.40 versus 0.42 and 2.48 versus 1.40) (Fig. 5A and B), suggesting that in contrast to ChC, TSS prefers to hydrolyze denatured collagenous substrates at elevated temperatures. Consistent with this, TSS showed an increased activity toward heat-treated compared to untreated type I collagen (Fig. 5D).

To investigate whether the observed high collagenolytic activity of TSS at elevated temperatures is mainly due to its gelatinolytic activity, the activities of mTSS toward type I collagen and gelatin were determined at 60°C and compared with those of ChC. For comparison purpose, here the collagenolytic reaction, as in the gelatinolytic reaction, was terminated by TCA treatment, and the acid-soluble peptides were quantified for activity determination. Intriguingly, mTSS exhibited approximately 10-fold lower gelatinolytic than collagenolytic activity, while ChC showed similar levels of gelatinolytic and collagenolytic activities (Fig. 5C). As a result, the gelatin/collagen ratio of mTSS was only 9.8% that of ChC (0.10 versus 1.02) (Fig. 5C). These results demonstrate that the high collagenolytic activity of TSS results from its preference for heat-denatured collagen rather than a high gelatinolytic activity. Additionally, the collagenolytic activity of mTSS measured at 60°C by acid-soluble peptides quantification (950 U/mg, Fig. 5C) was approximately 25% of that by water-soluble peptides quantification (3782 U/mg, Fig. 5B). In contrast, under the same conditions, the collagenolytic activity of ChC measured by acid-soluble peptides quantification (391 U/mg, Fig. 5C) was approximately 56% of that by water-soluble peptides quantification (694 U/mg, Fig. 5B). These data show that the hydrolyzed collagen peptides by TSS are more easily precipitated with TCA than those by ChC, reflecting a different catalytic behavior toward collagen between the two enzymes.

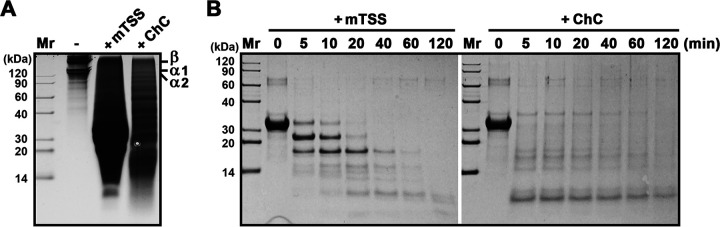

The digestion patterns of type I collagen and β-casein by mTSS were compared with those by ChC. When type I collagen was incubated alone at 60°C for 1 h, only a small number of α1, α2, and β (dimer) chains of collagen could be detected in the soluble fraction; in contrast, a large amount of collagen degradation products cleaved by mTSS or ChC were released into the soluble fraction (Fig. 6A). Evidently, the digestion pattern of type I collagen by mTSS was different from that by ChC (Fig. 6A). Meanwhile, the digestion pattern of β-casein by mTSS and ChC were also different (Fig. 6B). These results confirm that mTSS and ChC differ in their substrate cleavage specificity.

FIG 6.

Digestion patterns of type I collagen and β-casein by mTSS and ChC. (A) Digestion of type I collagen. The reaction was carried out at 60°C for 1 h in buffer B (for mTSS) or buffer C (for ChC) containing 3 mg/mL of type I collagen in the absence (−) or presence (+) of 1 μg/mL mTSS or 4 μg/mL ChC, and then the soluble fractions were subjected to tricine-SDS-PAGE analysis. The positions on the gel of α1, α2, and β (dimer) chains of collagen are indicated. (B) Digestion of β-casein. The reaction was carried out at 60°C for different time periods in buffer B (for mTSS) or buffer C (for ChC) containing 0.1 mg/mL of β-casein in the absence (−) or presence (+) of 0.07 μg/mL mTSS or ChC, and then the reaction mixtures were subjected to tricine-SDS-PAGE analysis.

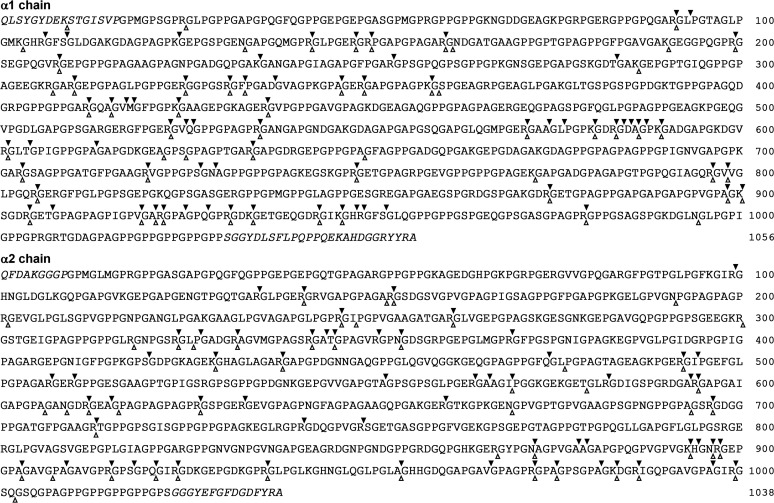

We next investigated the cleavage sites of insoluble and thermally solubilized type I collagen by mTSS at 60°C. By LC-MS/MS analysis of the digestion products, 130 and 83 peptides released from the insoluble and solubilized type I collagens, respectively, were identified (Tables S2 to S5), suggesting that the insoluble substrate is digested more efficiently than the solubilized substrate by mTSS. Accordingly, a total of 133 and 100 cleavage sites were determined in the insoluble and solubilized collagens, respectively (Fig. 7). For the two forms of substrates, 76 cleavage sites are shared by them, while 57 and 24 sites are present only in insoluble and solubilized substrates, respectively (Fig. 7), reflecting a similar but not identical digestion pattern of the two substrates by mTSS. In insoluble collagen, the P1 position is mainly occupied by Arg (∼50%), Ala (∼15%), and Lys (∼9%), and the P1’ position is almost strictly occupied by Gly (∼78%); in solubilized collagen, Arg and Gly are also the most common residues at the P1 (54%) and P1’ (77%) positions, respectively (Table 1). Moreover, type I collagen contains a total of 85 Arg-Gly peptide bonds, of which ∼71% and ∼56% in its insoluble and solubilized forms, respectively, are cleaved by mTSS (Fig. 7). These results suggest that TSS preferably acts on Xaa-Gly and Arg-Xaa (particularly Arg-Gly) peptide bonds of collagen.

FIG 7.

The cleavage sites of α1 and α2 chains of type I collagen by TSS at 60°C. The solid and hollow arrowheads indicate the cleavage sites of insoluble and solubilized type I collagen, respectively. The italicized sections indicate the N- and C-telopeptides.

TABLE 1.

Residue frequency at the P1 and P1’ sites of the α1 and α2 chains of insoluble and solubilized type I collagens cleaved by TSS

| Amino acid | Insoluble collagen |

Solubilized collagen |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 |

Total | P1’ |

Total | P1 |

Total | P1’ |

Total | |||||

| α1 | α2 | α1 | α2 | α1 | α2 | α1 | α2 | |||||

| Arg | 33 | 33 | 66 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 31 | 23 | 54 | 1 | 3 | 4 |

| Ala | 8 | 12 | 20 | 2 | 4 | 6 | 5 | 6 | 11 | 2 | 2 | |

| Lys | 9 | 3 | 12 | 10 | 3 | 13 | ||||||

| Val | 4 | 1 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | |||

| Ser | 3 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | ||

| Asn | 1 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Thr | 3 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||

| Gln | 2 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | |||||

| Gly | 2 | 2 | 57 | 47 | 104 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 44 | 33 | 77 | |

| Asp | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Leu | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| Ile | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| His | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Phe | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| Pro | 1 | 1 | 5 | 2 | 7 | 2 | 5 | 7 | ||||

| Met | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| Total | 72 | 61 | 133 | 72 | 61 | 133 | 53 | 47 | 100 | 53 | 47 | 100 |

Both the βJR and PPC domains of TSS have collagen-binding capacity but do not swell insoluble collagen.

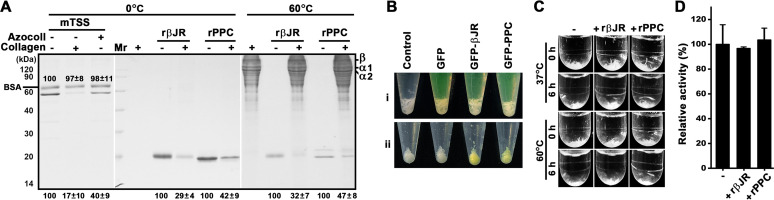

The binding capacities of mTSS for insoluble type I collagen and azocoll were investigated at 0°C to prevent substrate breakdown as much as possible (14). As shown in Fig. 8A, most mTSS molecules bound to type I collagen or azocoll were precipitated with the substrates, while approximately 17% (for type I collagen) or 40% (for azocoll) of mTSS molecules remained in the supernatant. As a control, bovine serum albumin (BSA) did not exhibit significant collagen-binding capacity under the same condition (Fig. 8A). Purified recombinant βJR (rβJR) and PPC (rPPC) domains (Fig. 2A) are able to bind to type I collagen at both 0°C and 60°C, although partial solubilization of the substrate occurred at 60°C (Fig. 8A). Green fluorescent protein (GFP)-fused βJR (GFP-βJR) and PPC (GFP-PPC) were also constructed (Fig. S2). In contrast to the GFP-treated type I collagen, the GFP-βJR- or GFP-PPC-treated type I collagen showed yellow-green color (Fig. 8B), confirming the collagen-binding ability of the βJR and PPC domains. We next investigated whether rβJR and rPPC have collagen-swelling ability. It was found that the volume of type I collagen was not changed significantly after treatment with rβJR or rPPC at either 37°C or 60°C (Fig. 8C), implying the two domains could not swell the substrate. Moreover, the activity of mTSS against rβJR- or rPPC-treated type I collagen was not improved as compared with that against untreated type I collagen (Fig. 8D).

FIG 8.

The collagen-binding and collagen-swelling capacities of TSS and its βJR and PPC domains. (A) Collagen-binding capacity. The proteins (10 μg/mL) were incubated at 0°C or 60°C for 1 h in 100 μL of buffer B in the absence (−) or presence (+) of 3 mg of type I collagen or azocoll. In some cases, BSA (10 μg/mL) was added into the binding mixture as a control. After centrifugation, the supernatants were subjected to SDS-PAGE analysis. The loading volume of the sample incubated at 60°C was one-fourth of that incubated at 0°C. Numbers within or at the bottom of the gels are the densitometric ratios of each band compared with that of the control lane (in the absence of the substrate). The bands of α1, α2, and β chains of collagen are indicated. (B) Observation of the collagen-binding ability of GFP, GFP-βJR, and GFP-PPC. Type I collagen (3 mg) was suspended in 600 μL of buffer B without (control) or with 15 μM each protein (i) and then incubated at 60°C for 1 h with shaking. After centrifugation, the insoluble fraction was washed with buffer B three times and then photographically recorded (ii). (C) Collagen-swelling capacity. Type I collagen (3 mg) was suspended in 1 mL buffer B without (−) or with (+) 20 μg/mL of rβJR or rPPC. Before (0 h) or after incubation at 37°C or 60°C for 6 h with shaking, the samples were photographically recorded. (D) Activities of mTSS against rβJR- or rPPC-treated type I collagen. Type I collagen was heated at 60°C in the absence (−) or presence (+) of rβJR or rPPC as described in (B), recovered by centrifugation, and then used as the substrate for measuring the activity of mTSS at 60°C in buffer B. The values are expressed as means ± SDs from three independent experiments (A, C).

Degradation of FSC by TSS.

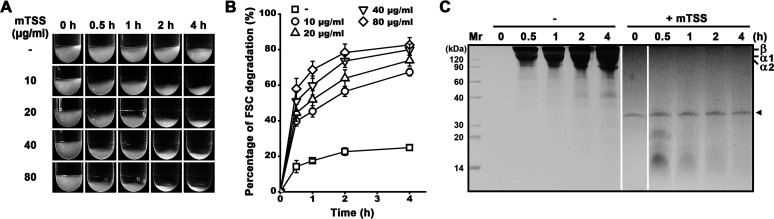

FSC was prepared from scales of grass carp as dried powder (Fig. S3). Like the case of type I collagen from bovine Achilles tendon (Fig. 6A), FSC could be partially solubilized at 60°C, as evidenced by the gradual reduction of FSC volume (Fig. 9A), the increase of the number of soluble peptides (Fig. 9B), and the emergence of α1, α2, and β chains in the soluble fraction with the extension of the incubation time (Fig. 9C). In the presence of mTSS, the volume of insoluble FSC decreased more profoundly than that in the absence of mTSS, and the FSC degradation was accelerated with the increase of mTSS concentration (Fig. 9A and B). Within 4 h, approximately 67, 74, 80, and 83% of FSC could be degraded into soluble peptides by 10, 20, 40, and 80 μg/mL of mTSS, respectively (Fig. 8B). Moreover, the α1, α2, and β chains of FSC were readily degraded into smaller peptides, most of which have migrated out of the gel (Fig. 9C). These results suggest that TSS is an efficient degrader of FSC at high temperatures.

FIG 9.

Degradation of FSC by TSS. Washed FSC powder (60 mg) was incubated in 3 mL of buffer B at 60°C with shaking in the absence (−) or presence of 10–80 μg/mL of mTSS. At different time intervals, images of FSC were photographically recorded (A), the number of soluble peptides released from FSC was quantified to calculate the percentage of FSC degradation (B), and the soluble fractions of the samples in the absence (−) or presence (+) of 10 μg/mL of mTSS were subjected to tricine-SDS-PAGE without TCA pre-treatment (C). The values are expressed as means ± SDs from three independent experiments (B). Note: mTSS showed an AMW of 35 kDa by tricine-SDS-PAGE analysis (C, indicated by an arrowhead), which is higher than that (22 kDa) by SDS-PAGE analysis using Tris-glycine buffer system (Fig. 3A).

DISCUSSION

Maturation.

The characterization of the mature forms of the reported subtilisin-like collagenolytic proteases including MO-1 (14), MCP-01 (32), Myroicolsin (17), and AcpII (16) reveals that their N-terminal propeptides and C-terminal domains or regions have been cleaved off; however, the maturation mechanisms of these enzymes remain to be elucidated. Here we demonstrate that the N-terminal propeptide and the C-terminal PPC domain of TSS are autocatalytically processed in a stepwise manner, yielding the mature form mTSS comprising the subtilisin-like catalytic domain and the βJR domain. Additionally, because the PPC domain is not essential for the autoprocessing of the N-terminal propeptide, as observed in ΔP and ΔP’, we do not exclude the possibility that the PPC domains in some pro-TSS molecules could be processed prior to the N-terminal propeptide by an active enzyme that matures earlier. The N-terminal propeptides of subtilisin-like proteases usually act as an intramolecular chaperone to assist in the folding of its cognate mature domain (33), although no requirement of the N-terminal propeptide for correct folding of the enzyme has been reported for some proteases such as Tk-SP (34). For TSS, its N-terminal propeptide deletion variant is susceptible to proteolysis, suggesting that the lack of the N-terminal propeptide affects the folding of the enzyme. Notably, TSS differs from known subtilisin-like collagenolytic proteases in the roles of the C-terminal domains in enzyme folding and maturation. For instance, the deletion of the C-terminal PD and PKD domains of MCP-01 does not prevent the folding of the enzyme into an active form (35). Similar to MCP-01, an AcpII variant that lacks the two PPC domains at the C-terminus is able to fold into an active form (16). In the case of TSS, the βJR domain but not the PPC domain is necessary for the folding and maturation of the enzyme. It appears that the C-terminal domains of subtilisin-like collagenolytic proteases play different roles in enzyme folding and maturation.

Thermostability.

With regard to thermostability, TSS is comparable to the collagenolytic protease from Thermoactinomyces sp. 21E, which is one of the most thermostable collagenolytic proteases reported so far (25); both of them retain approximately 80% of the original activity after incubation at 75°C for 30 min. Although TSS is most closely related to KP-43 in terms of the amino acid sequence and domain organization of the mature form, it is more thermostable than the latter (36). Most of the ligand residues of the Ca1, Ca2, and Ca3 sites of KP-43 are conserved in TSS, and all of the three Ca2+-binding sites contribute to the thermostability of TSS. One significant difference between the Ca3 sites of KP-43 and TSS is that Asp367 and Asp369 in KP-43 are replaced by Asn368 and Asn370 in TSS (Fig. 4B). In KP-43, the side chain oxygen atoms (Oδ1) of Asp367 and Asp369 are ligands for Ca2+ (37). The substitution of Asn368 or Asn370 of TSS with Asp destabilizes the enzyme. Given that the TSS Ca3 site binds Ca2+ in the same way as the KP-43 Ca3 site, the side chain oxygen atoms (Oδ1) of Asn368 and Asn370 in TSS could act as Ca2+-binding ligands. Although the replacement of Asn368 or Asn370 of TSS with Asp does not eliminate the Ca2+-binding ligands, the introduction of the negatively charged carboxyl group of Asp may increase unfavorable electrostatic repulsion at this site, leading to the destabilization of the enzyme. Interestingly, the thermostability of pyrolysin could be improved by Asn substitutions at Asp818 and Asp820 of the Ca2 site in the PPC domain (corresponding to Asn368 and Asn370 of the Ca3 site of TSS), most likely due to the elimination of unfavorable electrostatic repulsion at this Ca2+-binding site (38). In this context, the elimination of unfavorable electrostatic repulsion by using uncharged Asn instead of Asp as the Ca2+-binding residues appears to be one of the strategies for thermostabilization of TSS.

Solvent-accessible ion pairs have been identified as important contributors to protein thermostability (39, 40), and the proteins from thermophiles have more ion pairs, particularly long-range ion pairs, than those from mesophiles (41). Similarly, more surface long-range ion pairs are predicted for TSS than for KP-43, probably representing an important stabilizing factor of TSS at high temperatures. In support of this, we observed that TSS showed a decrease in thermostability as pH value increases from 9.0 to 11.0. Because basic amino acid residues tend to be deprotonated at high pH values, it is reasonable that the ion-pair interactions for stabilizing TSS would be attenuated, leading to a decrease in thermostability.

Halotolerance.

TSS exhibits increased thermostability with the increase of NaCl concentration up to 4 M. Such a high halotolerance has not been reported for other thermophile-derived collagenolytic proteases (19, 23, 25). Recently, we found that high-concentration NaCl improves the thermostability of the subtilisin-like protease Als (42). Although TSS and Als share low amino acid sequence identity (17%), both enzymes have an excess of solvent-accessible acidic residues. It is well known that solvent-accessible acidic residues contribute to the formation of a strong hydration shell for maintaining structural stability of haloarchaeal enzymes under high salinity conditions (43). Both TSS and Als seem to employ the same strategy as halophilic enzymes from haloarchaea to resist high salt concentrations. Nevertheless, TSS and Als are halotolerant rather than halophilic enzymes, since they are also highly stable in the absence of NaCl. Halophilic enzymes tend to lose their structural integrities under low salinity conditions due to strong electrostatic repulsion force exerted by acidic residues (43). Compared with its homologues from haloarchaea, both TSS and Als (42) possess an increased number of surface ion pairs, which may compensate for the destabilizing effect of electrostatic repulsion by negatively charged residues at low salt concentrations.

With the increase of salt concentration, the azocaseinolytic activity of TSS showed a trend of initial decrease followed by an increase, which could be interpreted as a combination of multiple processes. First, the increase of salinity would weaken electrostatic interactions in TSS, and thus may confer certain structural flexibility favorable for the catalytic hydrolysis of peptide bonds by the enzyme. This is supported by the fact that the activity of the enzyme against suc-AAPF-pNA continuously increased with rising salinity. Secondly, the salinity variation may influence the interactions between the substrate and the enzyme. Our data suggest that the βJR domain of TSS has the ability to bind collagen and also contributes to the azocaseinolytic activity of the enzyme. The βJR domain is situated far away from the active-site cleft of the catalytic domain (Fig. S1) and could provide additional binding sites only for a large protein substrate such as azocasein but not for a small substrate such as suc-AAPF-pNA. The increase of salinity would influence electrostatic and hydrophobic interactions in TSS and induce structural adjustment, which may affect the interaction of the enzyme (particularly the βJR domain) with azocasein for catalysis. Thirdly, the difference in salt-dependent catalytic behaviors of TSS toward azocasein and suc-AAPF-pNA may be related to salt-induced substrate conformation change, which is more evident in proteins than in peptides (44). The conformation change in azocasein would have influences on its binding to and catalysis by TSS, depending on salt concentration.

Collagenolytic activity.

The hydrolysis of collagen substrates by TSS is highly temperature-dependent, exhibiting high collagenolytic activity at high temperatures (e.g., 60–70°C) but a very low activity against type I collagen or azocoll at 37°C. This reflects not only the thermophilic nature of TSS but also its preference for heat-denatured rather than native collagen. It is considered that heat treatment leads to the conversion of collagen to gelatin, thus enzymatic degradation of collagen at high temperatures is mainly due to the gelatinolytic activity of the enzyme (6). However, TSS exhibits high collagenolytic but low gelatinolytic activity, with a very low gelatin/collagen ratio compared to ChC, suggesting that the high collagenolytic activity of TSS does not mainly result from its gelatinolytic activity. Additionally, TSS differs from ChC in their type I collagen- and β-casein-hydrolyzing patterns, implying that substrate cleavage specificity contributes to their differences in gelatinolytic activity. The collagenase PrtC from Porphyromonas gingivalis could hydrolyze heat-treated collagen but not gelatin at temperatures below 37°C; however, the collagenolytic mechanism of this enzyme remains unclear (20). The preference of TSS for insoluble heat-denatured collagen is obviously related to its collagen-binding ability, which would increase the local enzyme concentration around the substrate to facilitate collagen degradation. In contrast, soluble collagens are uniformly distributed in the solution and are unlikely to locally concentrate TSS as aggregated and insoluble collagens, so they are less efficiently degraded by the enzyme. This is supported by the evidence that more TSS-cleaved peptides are released from insoluble collagen than from thermally solubilized collagen. Meanwhile, the digestion patterns of the insoluble and solubilized collagens by TSS are similar but not the same, implying that the structural difference between the two forms of collagen has an effect on their degradation by the enzyme.

Bacterial collagenolytic proteases usually have a preference for certain peptide bonds of collagen, depending on the substrate state and the enzyme type. For native collagen, Clostridium and Vibrio collagenases (5), MCP-01 (45), and myroicolsin (17) have a strong preference for Gly at the P1’ position and a relatively broad preference for the amino acids at the P1 position. For denatured collagen, myroicolsin strictly prefers Lys and Arg at the P1 position and strongly prefers Gly at the P1’ position at 50°C (17); kumamolisin-As shows a very strong preference for Arg at the P1 position and a non-strict preference for aromatic or bulky aliphatic amino acids (Phe, Ile, Tyr, and Trp) at the P1’ position at 60°C (24). It is evident that, for all reported bacterial collagenolytic proteases except kumamolisin-As, the mostly preferred amino acid at the P1’ position is Gly, which is the most abundant amino acid in collagen. Meanwhile, in denatured collagen the peptide bonds with P1 basic residues are exposed and sensitive to collagenolytic proteases such as myroicolsin (17) and kumamolisin-As (24). In the case of TSS, it not only preferably acts on Xaa-Gly and Arg-Xaa (particularly Arg-Gly) peptide bonds of heat-denatured collagen, but also efficiently hydrolyzes the peptide bonds with P1 position occupied by Ala, which is also one of the most abundant amino acids in collagen, thereby endowing the enzyme with high collagenolytic activity at high temperatures.

The PKD domain of MCP-01 (15) and the PPC domains of several proteases from psychrotolerant/mesophilic bacteria (46) not only bind but also swell insoluble collagen, thereby facilitating substrate hydrolysis by the enzyme. In contrast, the binding of the βJR and PPC domains of thermophile-derived TSS to collagen does not result in collagen swelling, and TSS does not show improved activity on βJR- or PPC-treated collagen. We postulate that, as TSS prefers to hydrolyze collagen at high temperatures under which condition the substrate will be thermally denatured, a collagen-swelling domain seems to be unnecessary. The PPC domain of TSS is present in the proform and the maturation intermediate but not the mature form; therefore, it does not directly participate in the collagen binding of the mature form. Nevertheless, we cannot exclude the possibility that the PPC domain could mediate the binding of the proform and the intermediate to collagen, and thus increase the local enzyme concentration to facilitate enzymatic hydrolysis of the substrate.

Hydrolyzed collagen peptides have been widely applied in food, feed, pharmaceutical, and cosmetic industries, and the use of FSC-derived peptides are of renewed interests due to the safety and religious concerns of their mammalian counterparts (2, 47). By virtue of its high thermostability and collagenolytic activity, TSS could efficiently degrade FSC into small peptides at high temperatures and thus has the potential to be used for the preparation of functional peptides from fish scales.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

Restriction enzymes and Fast PFU DNA polymerase were purchased from ThermoFisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA). T4 DNA ligase was from TransGen Biotech (Beijing, China). Azocasein, casein, gelatin (from porcine skin), suc-AAPF-pNA, type I collagen (from bovine achilles tendon), azocoll (from bovine skin), and C. histolyticum collagenase were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA).

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

Brevibacillus sp. WF146 (CCTCC AB209297) was grown at 55°C in Luria–Bertani (LB) medium and used for extraction of genomic DNA as described previously (29). E. coli DH5α and E. coli BL21(DE3) were used for cloning and expression, respectively, and were grown at 37°C in LB medium supplemented with kanamycin (30 μg/mL) as needed.

Plasmid construction and mutagenesis.

The plasmid pET26b (Novagen, Madison, WI, USA) was used as the vector for expression of recombinant proteins in E. coli BL21(DE3). The primer sequences and the primer pairs used for PCR are listed in Tables S6 and S7, respectively. The gene encoding the proform of TSS (pro-TSS) was amplified by PCR from the genomic DNA of strain WF146 and inserted into the Nde I-Xho I site of pET-26b to construct the plasmid pET26b-pro-TSS. The DNA sequences encoding the C-terminal truncation variants (ΔP, ΔP’, and ΔβP), the N-terminal propeptide deletion variant (ΔN), and the N-terminal propeptide (rN), βJR (rβJR), and PPC (rPPC) domains of TSS were amplified from pET26b-pro-TSS by PCR and inserted into the vector pET-26b to construct the expression plasmids for the target proteins. Using pET26b-pro-TSS or pET26bΔN (Table S7) as the template, the expression plasmids for the active-site (pro-S257A, pro-S257C, and ΔN/S257A) and the Ca2+-binding-site variants (E187A, N368D, N370D, D385A, D393A, D396A, and E402A) of pro-TSS were constructed by the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis (SDM) method (48) using the mutagenesis primer pairs listed in Table S7. The GFP gene was amplified from the plasmid pAD123 (49) and inserted into pET26b to construct the expression plasmid for GFP. The DNA fragments encoding GFP and the βJR domain or PPC domain were subcloned into pET26b using Ready-To-Use Seamless Cloning Kit (Sangon Biotech, Shanghai, China) according to the manufacturer’s protocol, yielding the expression plasmids for the fusion proteins GFP-βJR and GFP-PPC. The sequences of all recombinant plasmids were confirmed using DNA sequencing.

Expression, activation, purification, and renaturation.

E. coli BL21(DE3) cells containing recombinant plasmids were cultured at 37°C until the optical density at 600 nm (OD600) reached ∼ 0.7. Production of recombinant proteins were induced by the addition of 0.4 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) and continued cultivation at 30°C for 4 h. Cells were harvested, suspended in buffer A (50 mM Tris-HCl, 10 mM CaCl2, pH 7.5), and disrupted by sonication on ice. The soluble and insoluble cellular fractions were separated by centrifuging the cell lysate at 13,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. The soluble cellular fraction containing pro-TSS or its Ca2+-binding-site variant was incubated at 60°C for 15 min to activate the enzyme, followed by centrifugation at 13,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. The resulting supernatant was then subjected to fractional salting-out with (NH4)2SO4 (50–80%), followed by ion-exchange chromatography on a buffer A-equilibrated DEAE-Sepharose Fast Flow (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences, Uppsala, Sweden) column to purify the mature enzyme. The recombinant protein with a fused His-tag (rβJR, rPPC, GFP, GFP-βJR, or GFP-PPC) in the soluble cellular fraction was purified by affinity chromatography on a Ni2+-charged Chelating Sepharose Fast Flow (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences) column equilibrated with buffer A. Purified protein samples eluted from the ion exchange and the affinity chromatography columns were dialyzed against buffer B (50 mM Gly-NaOH, 10 mM CaCl2, pH 9.0) overnight at 4°C. The protein solution was concentrated with an Amicon Ultra-15 3K centrifugal filter (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) as needed. The protein concentrations of the purified protein samples were determined using the Bradford method (50) with BSA as a standard.

The insoluble cellular fraction of E. coli BL21(DE3) cells producing ΔβP was dissolved in buffer A containing 8 M urea and incubated at 30°C for 1h. After centrifugation at 13,000 × g for 10 min, the supernatant was subjected to affinity chromatography as mentioned above, except that 8 M urea was included in the binding, washing, and elution buffers. The elution fraction containing ΔβP was dialyzed against buffer A at 4°C overnight to allow for protein renaturation.

SDS-PAGE, immunoblot analysis, and activity staining.

SDS-PAGE was performed using 12% polyacrylamide gel using Tris-glycine buffer system. In some cases, Tris-tricine buffer was used for tricine-SDS-PAGE analysis. To prevent self-degradation of the protease during sample preparation and electrophoresis, protein samples were precipitated with 20% (wt/vol) TCA, washed with acetone before being subjected to SDS-PAGE analysis. The anti-His-tag monoclonal antibody (1:10,000, Novagen) and the goat anti-mouse IgG secondary antibody (1:5000, Abbkine, China) were used for immunoblot analysis, as described previously (51). For protease activity staining, the samples without TCA treatment were mixed with the loading buffer and then subjected to a gelatin overlay assay as described by Blumentals et al. (52), except that the proteolytic reaction was carried out at 60°C for 3 h in buffer B.

Enzymatic activity assays.

Unless otherwise indicated, the azocaseinolytic, caseinolytic, or gelatinolytic activity of the enzyme was assayed at 60°C for 30 min in 600 μL of reaction mixture containing 300 μL of properly diluted enzyme sample and 0.25% (wt/vol) azocasein, 1.0% (wt/vol) casein, or 0.5% gelatin in buffer B. The reaction was terminated by the addition of 600 μL 40% TCA. After standing at room temperature (∼25°C) for 15 min, the mixture was centrifuged at 13,000 × g for 10 min to recover the supernatant. For enzymatic hydrolysate of azocasein, the absorbance of the supernatant was measured at 335 nm (A335) in a 1-cm light-path cell. One unit of azocaseinolytic activity was defined as the amount of enzyme required to increase the A335 value by 0.01 unit/min under the conditions described above. The acid-soluble peptides of the hydrolysate of casein or gelatin were quantified by Lowry’s method (53). One unit of caseinolytic or gelatinolytic activity was defined as the amount of enzyme that produced acid-soluble peptides equivalent to 1 nmol tyrosine per minute.

The proteolytic activity of TSS against suc-AAPF-pNA (0.2 mM) was measured at 60°C in buffer B. The activity was recorded by monitoring the initial velocity of suc-AAPF-pNA hydrolysis at 410 nm in a thermostated spectrophotometer (SP752; Shanghai Spectrum Instruments Co. Ltd, China). This velocity was calculated based on an extinction coefficient for p-nitroaniline (pNA) of 8,480 M−1cm−1 at 410 nm (54). One unit of enzyme activity was defined as the amount of enzyme that produced 1 μmol of pNA/min under the assay conditions.

The proteolytic activity of TSS against azocoll or type I collagen was measured as follows. The substrates were washed three times using buffer B with shaking at 37°C. Unless otherwise indicated, the activity assay was carried out at 60°C for 30 min with shaking in 600 μL of reaction mixture containing 3 mg of the substrate and properly diluted enzyme sample in buffer B. To quantify water-soluble peptides released from the substrates, the reaction was terminated by cooling on ice, followed by centrifugation of the mixture at 13,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C to recover the supernatant. In some cases, the reaction was terminated by the addition of 600 μL of 40% TCA, and the mixture was maintained at room temperature for 15 min, followed by centrifugation to recover the supernatant for quantification of acid-soluble peptides released from the substrates. For the supernatant of the enzymatic hydrolysate of azocoll, the absorbance was measured in a 1-cm light-path cell at 540 nm (A540). One unit of enzyme activity against azocoll was defined as the amount of enzyme required to increase the A540 value by 0.01 unit/min under the assay conditions. The soluble peptides released from type I collagen by the enzyme were quantified by Lowry’s method (53). One unit of collagenolytic activity was defined as the amount of enzyme that produced soluble peptides equivalent to 1 nmol tyrosine per minute (16).

The proteolytic activity of ChC against azocasein, casein, gelatin, azocoll, or type I collagen was measured as described above, except that buffer B was replaced by buffer C (50 mM Tris-HCl, 1 mM CaCl2, pH 7.5).

Determination of the cleavage sites of insoluble and thermally solubilized type I collagen by TSS.

To prepare solubilized collagen, insoluble type I collagen was incubated in buffer B at 60°C for 2 h. After centrifugation at 13,000 × g for 10 min, the supernatant was recovered and then concentrated with an Amicon Ultra-15 3K centrifugal filter. The insoluble and thermally solubilized type I collagens (1 mg/mL) were hydrolyzed with mTSS (1 μg/mL) in buffer B at 60°C for 1 h with shaking, and the reaction was terminated by cooling on ice, followed by centrifugation of the mixture at 13,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C to recover the supernatant. The cleaved peptides in the supernatant were determined by nano LC-MS/MS using an Easy-nanoLC system coupled online with the Q Exactive-HF mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific, San Jose, CA). The peptide sequences were identified using Proteome Discoverer 2.5 software (Thermo Scientific) with no-enzyme chosen as the enzyme. Dynamic modifications included were oxidation at methionine, phosphorylation at serine and threonine, and hydroxylation at proline and lysine.

Collagen-binding and collagen-swelling assays.

Insoluble type I collagen and azocoll were used as the substrates for the binding assay according to the method of Itoi et al. (14) with modifications. Briefly, 3 mg type I collagen or azocoll was washed with buffer B three times and then suspended in 100 μL buffer B containing 10 μg/mL target protein, followed by incubation at 0°C or 60°C for 1 h. Subsequently, the mixture was centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 5 min at 4°C, and the resulting supernatant was subjected to SDS-PAGE analysis. Protein bands were quantified by measuring band intensity using ImageJ software (NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA). For the collagen-binding assay of GFP-βJR or GFP-PPC, the protein (15 μM) was mixed with type I collagen (3 mg) in 600 μL buffer B, and the mixture was incubated at 60°C for 1 h with shaking. After centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 5 min at 4°C, the insoluble fraction was recovered, washed with buffer B three times, and then photographically recorded. Collagen-swelling assay was performed according to the method of Huang et al. (46) with modifications. Briefly, 3 mg of washed type I collagen was suspended in 1 mL buffer B containing 20 μg/mL target protein and then incubated at 37°C or 60°C for 6 h with shaking, followed by photographic recording.

Preparation and degradation of FSC.

Scales of grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idellus) collected from a local market were washed with tap water, air dried, and cut into pieces (∼ 3 × 5 mm2). Non-collagenous proteins and pigment of fish scales were removed by alkaline treatment according to the method of Matmaroh et al. (55) with some modifications. Briefly, the scale pieces were suspended in 0.1 M Na2CO3 at the ratio of 1:10 (wt/vol) with continuous stirring for 18 h, with Na2CO3 solution changed at 6 h intervals. The scale pieces were then washed with chilled distilled water until the wash water reached neutral pH. Subsequently, the decalcification of the scale pieces was carried out according to the method of Wang et al. (56) with some modifications. Briefly, the scale pieces were suspended in 0.5 M citric acid at the ratio of 1:10 (wt/vol) with continuous stirring for 1 h, followed by washing with chilled distilled water until a neutral pH was reached. The decalcified scale pieces were then dried at 50°C for 24 h, crushed in a mixing blender, and sieved to produce a 40-mesh FSC powder.

The FSC powder (60 mg) was washed three times using buffer B with shaking at 37°C, suspended in 3 mL buffer B containing different concentrations of mTSS as indicated, and then incubated at 60°C with shaking. At different time intervals, the reaction was terminated by cooling on ice, and the supernatant of the reaction mixture was collected by centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. The absorbance of the supernatant was measured in a 1-cm light path cell at 280 nm (A280). The A280 value of the reaction mixture, in which 20 mg FSC was completely degraded at 37°C by an excess amount of ChC in 3 mL buffer C, was also determined and used for calculating the amount of degradation products of FSC in the supernatant of the reaction mixture.

Homology modeling and ion pair prediction.

The structure model of TSS was generated using SWISS-MODEL (http://swissmodel.expasy.org) (57), with KP-43 (PDB code 1WMF) (37) as the template. For ion pair prediction, the distance between two oppositely charged atoms were measured using DeepView/Swiss-PdbViewer version 4.1 (https://spdbv.vital-it.ch). The distance limits were chosen to be 4.0 Å and 8.0 Å to find salt bridges (58) and long-range ion pairs (41), respectively.

Data availability.

The draft genome sequence of Brevibacillus sp. WF146 has been deposited in GenBank under the accession number PRJNA319752. The GenBank accession number of TSS is OBR56241.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Xiaolu Zhao and Wenda Huang (Wuhan University, China) for their help with LC-MS/MS analysis, and we thank Fei Gan (Wuhan University, China) for helpful discussion and critical reading of the manuscript.

This work was supported in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant numbers 31770072 and 31470185).

We have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available online only.

Contributor Information

Xiao-Feng Tang, Email: tangxf@whu.edu.cn.

Bing Tang, Email: tangb@whu.edu.cn.

Haruyuki Atomi, Kyoto University.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bella J. 2016. Collagen structure: new tricks from a very old dog. Biochem J 473:1001–1025. 10.1042/BJ20151169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu D, Nikoo M, Boran G, Zhou P, Regenstein JM. 2015. Collagen and gelatin. Annu Rev Food Sci Technol 6:527–557. 10.1146/annurev-food-031414-111800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shoulders MD, Raines RT. 2009. Collagen structure and stability. Annu Rev Biochem 78:929–958. 10.1146/annurev.biochem.77.032207.120833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fields GB. 2013. Interstitial collagen catabolism. J Biol Chem 288:8785–8793. 10.1074/jbc.R113.451211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang YZ, Ran LY, Li CY, Chen XL. 2015. Diversity, structures, and collagen-degrading mechanisms of bacterial collagenolytic proteases. Appl Environ Microbiol 81:6098–6107. 10.1128/AEM.00883-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Duarte AS, Correia A, Esteves AC. 2016. Bacterial collagenases—a review. Crit Rev Microbiol 42:106–126. 10.3109/1040841X.2014.904270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bond MD, Van Wart HE. 1984. Characterization of the individual collagenases from Clostridium histolyticum. Biochemistry 23:3085–3091. 10.1021/bi00308a036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Philominathan ST, Koide T, Hamada K, Yasui H, Seifert S, Matsushita O, Sakon J. 2009. Unidirectional binding of clostridial collagenase to triple helical substrates. J Biol Chem 284:10868–10876. 10.1074/jbc.M807684200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ohbayashi N, Yamagata N, Goto M, Watanabe K, Yamagata Y, Murayama K. 2012. Enhancement of the structural stability of full-length clostridial collagenase by calcium ions. Appl Environ Microbiol 78:5839–5844. 10.1128/AEM.00808-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eckhard U, Schonauer E, Brandstetter H. 2013. Structural basis for activity regulation and substrate preference of clostridial collagenases G, H, and T. J Biol Chem 288:20184–20194. 10.1074/jbc.M112.448548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Takeuchi H, Shibano Y, Morihara K, Fukushima J, Inami S, Keil B, Gilles AM, Kawamoto S, Okuda K. 1992. Structural gene and complete amino acid sequence of Vibrio alginolyticus collagenase. Biochem J 281:703–708. 10.1042/bj2810703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim SK, Yang JY, Cha J. 2002. Cloning and sequence analysis of a novel metalloprotease gene from Vibrio parahaemolyticus 04. Gene 283:277–286. 10.1016/s0378-1119(01)00882-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee JH, Ahn SH, Lee EM, Jeong SH, Kim YO, Lee SJ, Kong IS. 2005. The FAXWXXT motif in the carboxyl terminus of Vibrio mimicus metalloprotease is involved in binding to collagen. FEBS Lett 579:2507–2513. 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.03.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Itoi Y, Horinaka M, Tsujimoto Y, Matsui H, Watanabe K. 2006. Characteristic features in the structure and collagen-binding ability of a thermophilic collagenolytic protease from the thermophile Geobacillus collagenovorans MO-1. J Bacteriol 188:6572–6579. 10.1128/JB.00767-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang YK, Zhao GY, Li Y, Chen XL, Xie BB, Su HN, Lv YH, He HL, Liu H, Hu J, Zhou BC, Zhang YZ. 2010. Mechanistic insight into the function of the C-terminal PKD domain of the collagenolytic serine protease deseasin MCP-01 from deep sea Pseudoalteromonas sp. SM9913: binding of the PKD domain to collagen results in collagen swelling but does not unwind the collagen triple helix. J Biol Chem 285:14285–14291. 10.1074/jbc.M109.087023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kurata A, Uchimura K, Kobayashi T, Horikoshi K. 2010. Collagenolytic subtilisin-like protease from the deep-sea bacterium Alkalimonas collagenimarina AC40T. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 86:589–598. 10.1007/s00253-009-2324-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ran LY, Su HN, Zhou MY, Wang L, Chen XL, Xie BB, Song XY, Shi M, Qin QL, Pang XH, Zhou BC, Zhang YZ, Zhang XY. 2014. Characterization of a novel subtilisin-like protease myroicolsin from deep sea bacterium Myroides profundi D25 and molecular insight into its collagenolytic mechanism. J Biol Chem 289:6041–6053. 10.1074/jbc.M113.513861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Uesugi Y, Arima J, Usuki H, Iwabuchi M, Hatanaka T. 2008. Two bacterial collagenolytic serine proteases have different topological specificities. Biochim Biophys Acta 1784:716–726. 10.1016/j.bbapap.2008.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tsuruoka N, Nakayama T, Ashida M, Hemmi H, Nakao M, Minakata H, Oyama H, Oda K, Nishino T. 2003. Collagenolytic serine-carboxyl proteinase from Alicyclobacillus sendaiensis strain NTAP-1: purification, characterization, gene cloning, and heterologous expression. Appl Environ Microbiol 69:162–169. 10.1128/AEM.69.1.162-169.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kato T, Takahashi N, Kuramitsu HK. 1992. Sequence analysis and characterization of the Porphyromonas gingivalis prtC gene, which expresses a novel collagenase activity. J Bacteriol 174:3889–3895. 10.1128/jb.174.12.3889-3895.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bhattacharya S, Bhattacharya S, Gachhui R, Hazra S, Mukherjee J. 2019. U32 collagenase from Pseudoalteromonas agarivorans NW4327: activity, structure, substrate interactions and molecular dynamics simulations. Int J Biol Macromol 124:635–650. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.11.206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Suzuki Y, Tsujimoto Y, Matsui H, Watanabe K. 2006. Decomposition of extremely hard-to-degrade animal proteins by thermophilic bacteria. J Biosci Bioeng 102:73–81. 10.1263/jbb.102.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Okamoto M, Yonejima Y, Tsujimoto Y, Suzuki Y, Watanabe K. 2001. A thermostable collagenolytic protease with a very large molecular mass produced by thermophilic Bacillus sp. strain MO-1. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 57:103–108. 10.1007/s002530100731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wlodawer A, Li M, Gustchina A, Tsuruoka N, Ashida M, Minakata H, Oyama H, Oda K, Nishino T, Nakayama T. 2004. Crystallographic and biochemical investigations of kumamolisin-As, a serine-carboxyl peptidase with collagenase activity. J Biol Chem 279:21500–21510. 10.1074/jbc.M401141200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Petrova DH, Shishkov SA, Vlahov SS. 2006. Novel thermostable serine collagenase from Thermoactinomyces sp 21E: purification and some properties. J Basic Microbiol 46:275–285. 10.1002/jobm.200510063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wu J, Bian Y, Tang B, Chen XD, Shen P, Peng ZR. 2004. Cloning and analysis of WF146 protease, a novel thermophilic subtilisin-like protease with four inserted surface loops. FEMS Microbiol Lett 230:251–258. 10.1016/S0378-1097(03)00914-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhu H, Xu BL, Liang XL, Yang YR, Tang XF, Tang B. 2013. Molecular basis for auto- and hetero-catalytic maturation of a thermostable subtilase from thermophilic Bacillus sp. WF146. J Biol Chem 288:34826–34838. 10.1074/jbc.M113.498774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xu BL, Dai MH, Chen YH, Meng DH, Wang YS, Fang N, Tang XF, Tang B. 2015. Improving the thermostability and activity of a thermophilic subtilase by incorporating structural elements of its psychrophilic counterpart. Appl Environ Microbiol 81:6302–6313. 10.1128/AEM.01478-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhu F, Yang X, Wu Y, Wang YS, Tang X-F, Tang B. 2017. Release of an HtrA-like protease from the cell surface of thermophilic Brevibacillus sp. WF146 via substrate-induced autoprocessing of the N-terminal membrane anchor. Front Microbiol 8:481. 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tanaka S, Saito K, Chon H, Matsumura H, Koga Y, Takano K, Kanaya S. 2007. Crystal structure of unautoprocessed precursor of subtilisin from a hyperthermophilic archaeon: evidence for Ca2+-induced folding. J Biol Chem 282:8246–8255. 10.1074/jbc.M610137200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Madern D, Ebel C, Zaccai G. 2000. Halophilic adaptation of enzymes. Extremophiles 4:91–98. 10.1007/s007920050142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen XL, Xie BB, Lu JT, He HL, Zhang YZ. 2007. A novel type of subtilase from the psychrotolerant bacterium Pseudoalteromonas sp. SM9913: catalytic and structural properties of deseasin MCP-01. Microbiology (Reading) 153:2116–2125. 10.1099/mic.0.2007/006056-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shinde U, Thomas G. 2011. Insights from bacterial subtilases into the mechanisms of intramolecular chaperone-mediated activation of furin. Methods Mol Biol 768:59–106. 10.1007/978-1-61779-204-5_4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Foophow T, Tanaka S, Koga Y, Takano K, Kanaya S. 2010. Subtilisin-like serine protease from hyperthermophilic archaeon Thermococcus kodakaraensis with N- and C-terminal propeptides. Protein Eng Des Sel 23:347–355. 10.1093/protein/gzp092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhao GY, Chen XL, Zhao HL, Xie BB, Zhou BC, Zhang YZ. 2008. Hydrolysis of insoluble collagen by deseasin MCP-01 from deep-sea Pseudoalteromonas sp. SM9913: collagenolytic characters, collagen-binding ability of C-terminal polycystic kidney disease domain, and implication for its novel role in deep-sea sedimentary particulate organic nitrogen degradation. J Biol Chem 283:36100–36107. 10.1074/jbc.M804438200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Okuda M, Ozawa T, Tohata M, Sato T, Saeki K, Ozaki K. 2013. A single mutation within a Ca2+ binding loop increases proteolytic activity, thermal stability, and surfactant stability. Biochim Biophys Acta 1834:634–641. 10.1016/j.bbapap.2012.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nonaka T, Fujihashi M, Kita A, Saeki K, Ito S, Horikoshi K, Miki K. 2004. The crystal structure of an oxidatively stable subtilisin-like alkaline serine protease, KP-43, with a C-terminal β-barrel domain. J Biol Chem 279:47344–47351. 10.1074/jbc.M409089200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zeng J, Gao X, Dai Z, Tang B, Tang XF. 2014. Effects of metal ions on stability and activity of hyperthermophilic pyrolysin and further stabilization of this enzyme by modification of a Ca2+-binding site. Appl Environ Microbiol 80:2763–2772. 10.1128/AEM.00006-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Voorhorst WG, Warner A, de Vos WM, Siezen RJ. 1997. Homology modelling of two subtilisin-like proteases from the hyperthermophilic archaea Pyrococcus furiosus and Thermococcus stetteri. Protein Eng 10:905–914. 10.1093/protein/10.8.905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Karshikoff A, Nilsson L, Ladenstein R. 2015. Rigidity versus flexibility: the dilemma of understanding protein thermal stability. FEBS J 282:3899–3917. 10.1111/febs.13343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Szilagyi A, Zavodszky P. 2000. Structural differences between mesophilic, moderately thermophilic and extremely thermophilic protein subunits: results of a comprehensive survey. Structure 8:493–504. 10.1016/S0969-2126(00)00133-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ding Y, Yang Y, Ren Y, Xia J, Liu F, Li Y, Tang XF, Tang B. 2020. Extracellular production, characterization, and engineering of a polyextremotolerant subtilisin-like protease from feather-degrading Thermoactinomyces vulgaris strain CDF. Front Microbiol 11:605771. 10.3389/fmicb.2020.605771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]