Highlights

-

•

Social inequalities in health increased especially during lockdown.

-

•

Homeless persons felt neglected as lockdown was designed for those with stable housing.

-

•

Access to an emergency shelter had positive impacts on homeless persons.

-

•

Sudden implementation of lockdown reminded prior violent or traumatic circumstances.

-

•

Crisis communication should be adapted to improve adherence to preventive measures.

Keywords: Lockdown, COVID-19, Social health inequalities, Homeless, Migrants

Abstract

Social inequalities tended to increase in the context of the pandemic, particularly in relation to the measures taken to manage and reduce the risk of COVID-19. When lockdown measures required the general population “to stay home”, what were homeless people expected to do? The ECHO study is a cross-sectional, descriptive study with a convergent mixed-method design. Data were collected across shelters in France both during and immediately following the lockdown (April – June 2020). This article presents the study’s qualitative findings, with a focus on understanding both the experiences and perceptions among these populations of the measures taken to limit the COVID-19 infection. A total of 26 semi-directed individual interviews were conducted across seven shelters in both Lyon (42%) and Paris (58%). Data were analysed using thematic content analysis with partial blinded coding. Four key themes were identified: 1- Reactions to the introduction of lockdown: a sudden implementation reminiscent of prior violent or traumatic circumstances amongst participants, 2- Accommodation during lockdown: participants’ conflicting visions of the shelter, 3- Influence of the media and public communication: an abundant flow of information impacting participant’s wellbeing and representations on the pandemic, and 4- The individual impact of lockdown: perceived health and limitations to daily life activities. The most vulnerable populations have borne the heaviest burden during the pandemic. It is therefore crucial that we improve both the availability of information, and the health literacy of, all groups within the national population.

1. Introduction

The spread of COVID-19 resulted in a health crisis which prompted the World Health Organization to declare a global pandemic on March 11, 2020 (Organisation Mondiale de la Santé (OMS), 2020). French public authorities took measures in order to protect the health of the population. The initial lockdown in France prohibited all individuals residing on national territory from leaving their homes, except for specific reasons (e.g. professional activity) justified by an exit permit. People who did not respect these rules were subject to fines.

Prior research found that social inequalities during pandemics created an unevenly distributed risk of disease in the population (Dubost, 2020, Kluge et al., 2020) based on these three modalities: 1. the probability of being exposed to the virus (e.g. overcrowding of accommodation, ability to work from home); 2. the probability of contracting the virus, if exposed (e.g. host immunity, age, comorbidities); and 3. the probability of obtaining prompt and effective treatment after contracting the disease (e.g. knowledge of the healthcare system, logistical obstacles) (Blumenshine et al., 2008). In addition to these three levels, sources of socioeconomic or ethnic disparities can further exacerbate differential rates of illness or death (Blumenshine et al., 2008). The COVID-19 pandemic saw inequalities increased even further when numerous preventive measures were introduced, the most significant of which being the lockdown (Dubost, 2020, Kluge et al., 2020). The first Global Evidence Review on Health and Migration (GEHM) mapped how the needs of ethnic minorities have been addressed across countries during the pandemic, including potential discriminatory practices (World Health Organization, 2021). This report emphasized the importance of integrated approaches regarding migration and public health policies, particularly for providing equal access to health care, regardless of ethnicity.

The most vulnerable populations had no choice but to live in inadequate and overcrowded conditions, thus simultaneously increasing their exposure to health hazards whilst impeding their ability to isolate themselves or respect preventive measures (Kluge et al., 2020, Baktavatsalou and Thibault, 2020). Moreover, the lack of available resources and access to basic sanitary protection or preventive information increased inequalities in this context (Kluge et al., 2020). Lockdown measures also required the public to stay at home - a paradoxical demand for homeless populations

To help the most disadvantaged and vulnerable populations, several measures were implemented upon the principle of providing unconditional shelter. For example, annual winter shelters were maintained for longer, the validity period of residence permits was extended, and, noteworthily, accommodation centres in hotels or empty buildings were opened. People who were usually excluded from such care and assistance and therefore poorly captured by public statistics (Baronnet et al., 2015) have here been made visible.

This article is based on the ECHO study (Longchamps et al., 2021), a cross-sectional, descriptive study with a convergent mixed-method design (Creswell and Plano, 2020), aiming to assess the knowledge, perceptions and practices related to the COVID-19 pandemic among people living in shelters. The following report is based on qualitative data collected in seven emergency shelters in the regions of Paris and Lyon.

2. Materials and methods

The qualitative phase of this study was conducted using semi-structured interviews in Lyon (n = 3) and Paris (n = 4) following the end of the first lockdown in France (May 10th to June 10th 2020). The target population consisted of individuals living in shelters with the following inclusion criteria: 18 years old or over; without cognitive impairments; and with a basic level of French or English. The estimated sample size to reach data saturation was set at 30 participants, as supported by previous literature (Pires, 1997).

Interviews were conducted either in French or English by two researchers (LC, ACC) at participants’ shelters, in an environment conducive to confidentiality. Based on prior literature on healthcare access and the living conditions of vulnerable populations (Graetz et al., 2017, Winters et al., 2018, Vandentorren et al., 2016, La, 2009, Cognet et al., 2012), an interview guide was designed with the aim of exploring one’s attitude and representations regarding the lockdown (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Interview guide.

| No. | Question |

|---|---|

| 1 | How did you arrive at this shelter? |

| 2 | How did you learn about the lockdown? |

| 3 | What does it mean to you to be in lockdown? |

| 4 | What is it like to live on the streets now? How has the lockdown impacted your life? |

| 5 | What is the purpose of the lockdown? |

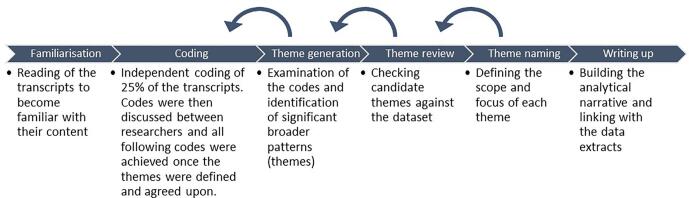

All interviews were recorded and fully transcribed. Transcripts were analysed based on an inductive thematic approach (Bardin and Chapitre, 2013, Braun et al., 2019) using NVivo© (release 1.3 535) software. The analysis process consisted of six steps (cf. Fig. 1): familiarisation, coding, theme generation, reviewing, naming, and writing up (Allard-Poesi, 2003, Negura, 2006). Once familiar with the data, blinded coding of 25% of the transcripts was undertaken by two researchers (LC, SD) in order to classify the initial codes and achieve inter-coder reliability (Allard-Poesi, 2003). We obtained an intercoder reliability rate of 93% (Saubesty, 2006) which, based on the agreement rate of Huberman and Miles (Miles and Huberman, 2003), represents a satisfactory reliability. The researchers discussed these codes and reached consensus. The first researcher (LC) then coded the rest of the transcripts based on these codes. A constant comparative method (Creswell and Plano, 2020) guided the development of themes derived from the data. These themes were then discussed and agreed to by LC and SD. Data saturation was attained with conclusive categories identified from the coded data (Braun et al., 2019).

Fig. 1.

Thematic analysis steps.

The protocol for this study was validated by the Research Ethics Committee of the University of Paris (CER-2020-41). Oral consent was systematically collected before all interviews and all transcripts were anonymized.

3. Results

Twenty-six homeless individuals participated in our study, 11 of whom were residing in emergency shelters in the Lyon region and 15 in the Paris region. Interviews lasted on average 24 min, and three quarters of them (n = 19) were conducted in French. Study participants were mainly male (n = 19), born abroad (n = 19), did not have a job at the beginning of lockdown (n = 22) and were on average 31 years of age (ranging 19–50 years). One quarter of participants (n = 7) were seeking asylum at the time of the study, whilst five had refugee status and five were undocumented migrants. When lockdown was announced in March 2020, the majority of study participants were living on the street (n = 15). Table 2 presents the demographic characteristics of the study population.

Table 2.

Participants characteristics for the ECHO study group, collected during the first COVID-19 lockdown in France, during Spring 2020.

| Total cohort | |

|---|---|

| Sex | (n = 26) |

| Male | 73% (19) |

| Female | 27% (7) |

| Age (years) | |

| 18–29 | 46% (12) |

| 30–49 | 31% (8) |

| 50+ | 23% (6) |

| Region of birth | |

| France | 27% (7) |

| Africa | 31% (8) |

| Asia | 31% (8) |

| Other | 12% (3) |

| Administrative status | |

| French or residence permit holder | 35% (9) |

| Asylum seeker | 27% (7) |

| Refugee | 19% (5) |

| Undocumented migrant | 19% (5) |

| Accomodation prior to lockdown | |

| Street/squat | 58% (15) |

| Shelter | 19% (5) |

| Friends/family | 23% (6) |

| Employment status prior to lockdown | |

| Unemployed | 85% (22) |

| Employed | 15% (4) |

Our thematic content analysis identified four key themes: 1- Reactions to the introduction of lockdown, 2- Accommodation during lockdown, 3-Influence of the media and public communication, and 4- The individual impact of lockdown.

3.1. Reactions to the introduction of lockdown

For study participants, the sudden announcement and implementation of lockdown came like a bolt of lightning. Several participants reported prior experiences of lockdown in reference to violent or traumatic circumstances, such as war or periods of mourning. At first, before obtaining accommodation, lockdown measures led to a worsening of participants’ living conditions. Examples of this include difficulties in relation to:

-

-

freedom of movement, due to police checks and the need to present exit permits;

-

-

income, linked to obstacles surrounding both employment and begging;

-

-

maintaining isolation and social distancing due to crowded living conditions and lack of accommodation;

-

-

protecting oneself from COVID-19 due to precarious living conditions and an absence of face masks, hydroalcoholic gel and hygienic conditions;

-

-

accessing food, due to the closing of humanitarian associations; and accessing healthcare.

“I already have nowhere to shower, eat, running behind [homeless] assistance teams, I eat the same thing all the time, so there you go, I couldn't confine myself. Where was I going to confine myself? So, we were confined outside, anyway? We were confined on the street? Rain, shine, snow, dust, we were outside, we had nowhere to go.” Man, 32 years old, Ivorian, translated from French

When participants were finally granted access to a shelter, this was perceived as an opportunity to protect themselves against COVID-19, to improve their health, and to provide physical and mental rest and stability. Nevertheless, placement by the public accommodation guidance services (i.e. “Service intégré d'accueil et d'orientation”), in combination with lockdown measures, took participants away from their informal networks of mutual aid.

3.2. Accommodation during lockdown

Lockdown is an individual as well as a collective protective measure against COVID-19. Depending on one’s experience and point of view, lockdown could be interpreted as a measure with both positive and negative implications: which could lead to an ambivalent feeling among some participants. On one hand, lockdown was perceived by half of the participants as a time of mutual assistance between individuals and society, requiring compliance with sanitary policies. For participants who benefited from a shelter early on, lockdown was perceived as a sign of consideration from the government. Lockdown was therefore seen as a necessary measure, which was readily accepted and observed by these participants.

On the other hand, some interviewees expressed incomprehension and distrust towards the measures introduced by the government. Lockdown was perceived as unrealistic in relation to their living conditions. Indeed, for people who experienced most of their lockdown living on the street, this period represented both a risk to their health and a deprivation of freedom. According to them, the government did not support them during the pandemic which reinforced feelings of mistrust towards the government and its actions

“The epidemic only does damage to those who are on the street. Those who know they have apartments, you go home, you confine yourself. But us, we had no choice, we had to stay in a small room all together“ Man, 20 years old, Guinea, translated from French

3.3. Influences of the media and public communication

The abundant flow of information on COVID-19, diffused across various forms of media (mainly television and social networks), also appeared to impact participants’ well-being. Daily reports covering the increasing number of new cases and deaths, as well as the absence of information on the management of the pandemic and COVID-19 itself, provoked fear and anxiety amongst study participants.

“Always new information on TV, in fact we don't know who to believe and who to listen to. It's good to be informed, but there is too much information and we do not understand which is true, which is false.” Woman, 19 years old, French, translated from French

According to those interviewed, communication from the government contributed to the perception of COVID-19 as being a particularly dangerous and contagious disease. Participants referred to the pandemic as a global war against a common enemy. The perceived danger of COVID-19 was accentuated further by the strict measures put in place.

“I said “How are we going to do it? How are we going to eat?” One week. One week was a struggle, I felt like it was the end of the world, especially in the evening. […] I did not understand what was going on, the police they said to me “Go home!” and I was thinking of going back to the village, to my country. I thought there is a war, they don't want us, I don't know! I didn't even know what the police wanted. “Go home!”. But I don't have a home. […] I thought it was the end of the world.” Man, 33 years old, Algeria, translated from French

3.4. The individual impact of lockdown

Lastly, lockdown measures appeared to hinder participants’ daily life through administrative and economic difficulties. This is particularly relevant to the study population, as these procedures are often imperative for acquiring a more favourable administrative status or degree of medical coverage.

“I am still looking forward to the outcomes or the consequences of my asylum application and unfortunately the coronavirus has affected it; you know it's a global challenge affecting the world and particularly my asylum application” Man, 35 years old, Afghanistan, in English

For most of the participants, daily activities were limited to: taking care of one’s children and personal health, shopping for basic necessities, and cleaning. Restrictions concerning activities appeared to be associated with a strong sense of boredom amongst participants. Shopping also became more difficult in relation to social distancing and fears of being contaminated by others.

In the shelters, life was adapted in accordance with the new sanitary regulations. Some interviewees avoided using the shelter’s common spaces, whilst others took advantage of the opportunity to socialise with other residents. In general, participants reported complying with preventive sanitary measures (wearing masks, washing hands, etc.).

“I have never seen such a virus in the world, because since I was 18 years old, I have heard of Ebola, AIDS, and other diseases, yet they have never closed places of worship”. Man, 20 years old, Guinea, translated from French

Lockdown also appeared to have a significant impact on participants’ perceived health status. This was particularly noticeable with regard to participants’ mental health, which was worsened by fears of illness, stress, and lack of motivation. Two interviewees declared having attempted suicide during the lockdown period.

“When we were not well, I couldn't find any solution, so I mentally told myself that I wasn't going to get out of it anymore, which you shouldn’t say yourself in such case, it gets worse and worse, I saw that darkness, I couldn't find the light.” Man, 19 years old, France translated from French

Regarding physical health, other negative impacts such as malnutrition, sleep disturbances, and migraines were also reported. Two people suffering from nutritional pathologies said that their disorders were aggravated during this period. The uncertainty surrounding their return to the street was reported as a real concern by several interviewees.

Nevertheless, several participants expressed that their current shelter allowed them to rest without the burden of having to look for a stable place to eat or sleep. Such accommodation provided a setting with not just regular mealtimes and access to proper hygiene facilities, but also privacy, in the form of personal, defined spaces, and a place to sleep. Moreover, any associated social and medical support, particularly in relation to COVID-19, was appreciated by the respondents and contributed to feelings of support and security.

4. Discussion

In this qualitative study conducted across homeless shelters during the first stages of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, we found that people in precarious situations perceived a worsening of living conditions due to lockdown. This was manifested in many ways, such as changes to participants’ freedom of movement, and access to accommodation, public administration, food, and hygiene. The perception of lockdown also varied amongst those interviewed. For some participants, the introduction of lockdown was reminiscent of their previous exposure to violent contexts, like war. It was also felt to be inconsistent and unsuitable to the living conditions of homeless persons. As a result, lockdown appeared to generate among these participants mistrust towards the authorities. For others, it represented a form of security and protection against COVID-19. The information received during this period also appeared to impact participants’ well-being. Reports on the number of deaths, or a lack of information in general, were a source of worry for the interviewees.

Differential impacts of lockdown were reported between participants, in relation to: deteriorating health (mainly mental health); delayed administrative procedures; financial difficulties; and difficulties shopping for basic necessities. However, social distancing and lockdown measures were considered effective and easy to comply with as long as accommodation was provided. The promise of unconditional shelter also positively impacted participants by providing a secure, restful environment with access to healthy food, hygiene, privacy and both medical and social support.

5. Strengths and limits of the study

The ECHO study is, to our knowledge, one of the first studies to investigate perceptions of the COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown amongst vulnerable populations living in homeless shelters in France. Conducting interviews in English allowed us to include persons with a wide range of sociodemographic characteristics, particularly those recently arriving in France. Data saturation was achieved according to the principle of theoretical sufficiency – developed by Glaser and Strauss (Glaser and Strauss, 2010)- therefore our results provided significant insight on this population in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Although our study represents a unique data source, including homeless and migrant participants often underrepresented in research, it is not without its limitations. Firstly, the limited sample size – although consistent with the literature (Pires, 1997) – cannot guarantee that all profiles within these groups are represented in our results. Participants were only recruited from shelters, thereby excluding all those still living on the streets and potentially excluding the most precarious population. However, during this first lockdown, the French government had an active policy of sheltering all homeless persons, as a preventive measure against the propagation of COVID-19. Overall, 58% of our sample were living on the streets before lockdown, thus indicating that these participants might be more comparable to the general homeless population than the usual population living in shelter. Finally, ECHO’s data collection was cross-sectional, limiting our understanding of the impact of COVID-19 to a specific moment in time. The representations and attitudes towards the pandemic and its related policies in this population may have since evolved.

Our results indicated that, within our study population, the COVID-19 pandemic was perceived as a major health hazard. Participants referred to the pandemic as a global war. The arrival of an unknown virus can explain anxiety and stress, ultimately creating a feeling of powerlessness and fear (Venuleo et al., 2020). Surprisingly, the perceived danger of COVID-19was accentuated by the exceptional measures taken to address the virus. Whilst lockdown was defined by the interviewees as a useful form of protection and security against the pandemic, they described several significant, negative changes to their daily life. In accordance with these findings, Venuleo et al. (2020) found that the measures taken to manage the pandemic severely impacted the general population's living habits, e.g. visiting friends or taking children to school, cumulatively leading to psychological difficulties. In our study as in the general population, feelings of security were also associated with shelter (Bourdeau-Lepage, 2020).

Since the onset of this unprecedented health crisis, accommodation has become “the frontline defence against coronavirus” (Pierre, 2020). Lockdown and unconditional shelter positively changed the perception of lockdown within our study population. Indeed, the quality of accommodation (size, outdoor space, etc.) influenced participants’ quality of life during this period (Bourdeau-Lepage, 2020). However, in general, emergency shelter provided a greater quality of protection, privacy, food, sleep and hygiene (Pierre, 2020).

There are several important factors supporting the duty to shelter this population. Firstly, the safeguarding of the individuals themselves, but beyond that, it is in the collective interest of public health. Failure to protect vulnerable populations represents a risk for everyone. In the face of a pandemic, neglecting the most vulnerable not only endangers them, but also other segments of society. These are two crucial reasons for sheltering the homeless during a pandemic (La and Hirsch, 2020).

In the French general population, life satisfaction deteriorated during lockdown with increasing rates of anxiety, depression or sleep disorders among the most isolated (Yen-Hao Chu et al., 2020, France, 2021, Ohlbrecht and Jellen, 2021). The health crisis had a significant psychological impact, aggravating emotional distress (Yen-Hao Chu et al., 2020). Our study population reported unsatisfactory fulfilment of their basic needs (food, hygiene, accommodation) and high rates of mental disorders before being offered a shelter (Vandentorren et al., 2016, Scarlett et al., 2021). Similarly, the ApartTogether survey (Spiritus-Beerden et al., 2021) highlighted that the mental health of refugees and migrants in Europe during the pandemic was significantly impacted, with increased levels of discrimination and daily life stressors. Other authors demonstrated that the situation before lockdown impacted one’s experience of lockdown (France, 2021, Ohlbrecht and Jellen, 2021). People with fewer resources appeared to struggle more to adapt to lockdown measures. Moreover, depending on one’s socioeconomic background, the consequences and impacts of the health crisis are felt differently, with those who are disadvantaged being more severely affected (France, 2021, Ohlbrecht and Jellen, 2021, World Health Organisation, 2021). According to the French National Academy of Medicine there is a growing association between precariousness and COVID-19, as the socioeconomic conditions of vulnerable populations prevented them from fully protecting themselves during the lockdown (Académie nationale de médecine, Académie nationale de pharmacie, 2021).

Malnutrition and food insecurity are major problems for homeless populations (Vandentorren et al., 2016). Tarasuk et al. (2009) indicated that the predominant strategy used to address these problems among young homeless persons is the use of food-distributing charities and associations. However, during the first lockdown in France, social services were limited (Dubost, 2020, Pierre, 2020) making access to food difficult for their usual beneficiaries. This is in line with the results from the ECHO epidemiological study, which showed that 39% of participants had difficulties feeding themselves due to disruptions in the food-distributing networks and a lack of money (Longchamps et al., 2021).

Similarly, income obtained through begging also suffered from shop and restaurant closures, alongside restrictions to social activities in public spaces. The quantitative results of the ECHO study indicated that, among participants who were employed before the pandemic, more than half (54.4%) became unemployed (without income) during the first lockdown (Longchamps et al., 2021). During this lockdown, the fulfilment of basic needs (Healy, 2016) such as access to clean water, food, hygiene, rest, healthcare, mental health support and access to technology were problematic (France, 2021).

Previous literature has identified inequalities surrounding communication during pandemics, affecting linguistic minorities and socially excluded, precarious populations most severely (Yen-Hao Chu et al., 2020). This unequal access to information creates mistrust due to inconsistent or a lack of information (Yen-Hao Chu et al., 2020). This may cause stress, anxiety and apprehension in the face of a pandemic. Some control measures, such as exit permits and police checks, were perceived as coercive, thus contributing to greater feelings of mistrust (Yen-Hao Chu et al., 2020). A strict lockdown without prior public consultation and engagement may have also increased feelings of suspicion towards governing bodies (Yen-Hao Chu et al., 2020). Moreover, emergency shelters were often perceived as unsuitable for the proper implementation of lockdown measures, resulting in participants perciving that lockdown protected the “rich” better, i.e. those with stable housing. Homeless populations may have felt unaccounted for by these rapid decisions made by public authorities.

According to these interviews, the four factors that prevented the most disadvantaged from protecting themselves were: lack of shelter, lack of protection, disruption to daily needs and misinformation. Our results are in line with other surveys showing increased anxiety, fatigue, and a lower sense of security and life satisfaction among lower socioeconomic groups (Ohlbrecht and Jellen, 2021, Bourdeau-Lepage, 2020).

The COVID-19 pandemic is not just a sanitary problem, but rather a social phenomenon (Ohlbrecht and Jellen, 2021). However, despite the health crisis, positive repercussions can be seen through increases in mutual aid, solidarity, and subsequently people’s trust in one another (Ohlbrecht and Jellen, 2021).

6. Conclusion

The most vulnerable populations have borne the heaviest burden during national responses to the COVID-19 pandemic. At a larger scale, the GEHM highlighted the compound factors that led to disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on refugees and migrants (World Health Organization, 2021). The preventive measures that were implemented in response to this immediate crisis appeared to be difficult for homeless populations to comply with. Study participants felt neglected by the authorities as the implemented measures were felt to be designed for those with stable housing. Nonetheless, the COVID-19 response was perceived as having a positive impact by some participants, with lockdown providing much-needed shelter and respite. Finally, this study showed an increase in social inequalities with serious consequences for the most vulnerable (Dubost, 2020).

The protection of the entire national population, especially the most vulnerable, is a real challenge for controlling health crises. The spread of infection amongst unprotected populations is harder to contain (Pierre, 2020). Increases to both the availability of information and health literacy are essential to reduce health inequalities, two crucial social determinants of health (Ataguba and Ataguba, 2020). Communication surrounding the COVID-19 pandemic must take into account socio-economic inequalities and pre-existing vulnerabilities (World Health Organization, 2021, Ataguba and Ataguba, 2020). To improve adherence to preventive measures amongst the most vulnerable populations, policymakers should base measures on equity so that they are accessible to all. Following WHO plead, the governments should also ensure that ethnic minorities are included in these policies (World Health Organization, 2021). Our study results highlight the importance of proportionate universalism in order to address social inequalities in health (Marmot and Bell, 2012). Further research is required to assess the long-term impact of these pandemic control measures, including the introduction of COVID-19 vaccines.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Lisa Crouzet: Writing – original draft. Honor Scarlett: Writing – review & editing. Anne-Claire Colleville: Investigation. Lionel Pourtau: Project administration. Maria Melchior: Supervision, Writing – review & editing. Simon Ducarroz: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

Firstly, we would like to thank the participants who agreed to take part in this study. We also thank the non-governmental organisations involved in this study: Habitat et Humanisme, Aurore, the French Red-Cross, Empreintes, Groupe SOS, La Rose des vents, SIAO 67, and their managers, social workers and volunteers for their kind participation. Finally, thank you to the other members of the ECHO team.

Sources of funding

This work was supported by the French National Research Agency (ANR, grant no. ANR-20-COV9-0005-01, project ECHO) and the European Commission Horizon 2020 H2020-SC1-PHE-CORONAVIRUS-2020-2 call (project PERISCOPE, grant no. 101016233).

References

- Organisation Mondiale de la Santé (OMS), 2020. COVID-19 – Chronologie de l’action de l’OMS [Internet]. who.int. 2020 [cited 2020 Nov 17]. Available from: https://www.who.int/fr/news/item/27-04-2020-who-timeline---covid-19.

- Dubost, C., 2020. Les inégalités sociales face à l’épidémie de Covid-19. DREES/OSAM/BESP. 2020 Jul;(n°62):40.

- Kluge H.H.P., Jakab Z., Bartovic J., D'Anna V., Severoni S. Refugee and migrant health in the COVID-19 response. Lancet Lond. Engl. 2020;395(10232):1237–1239. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30791-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumenshine, P, Reingold, A, Egerter, S, Mockenhaupt, R, Braveman, P, Marks, J., 2008. Pandemic Infl uenza Planning in the United States from a Health Disparities Perspective. 2008;14(n°5):709–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization, 2021. Refugees and migrants in times of COVID-19: mapping trends of public health and migration policies and practices [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2021 [cited 2022 Feb 1]. (Global evidence review on health and migration (GEHM)). Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/341843. [PubMed]

- Baktavatsalou, R, Thibault, P., 2020. Covid-19 - Les conditions de confinement à Mayotte: La précarité des conditions de vie rend difficile le respect des mesures de confinement. INSEE Anal [Internet]. 2020 May;n°23. Available from: http://www.epsilon.insee.fr/jspui/bitstream/1/129005/1/my_ina_23.pdf.

- Baronnet J., Kertudo P., Faucheux-Leroy S. La pauvreté et l’exclusion sociale de certains publics mal appréhendés par la statistique publique. Rech Soc. 2015;215(3):4. [Google Scholar]

- Longchamps, C, Ducarroz, S, Crouzet, L, El Aarbaoui, T, Allaire, C, Colleville, AC, et al., 2021. Connaissances, attitudes et pratiques liées à l’épidémie de Covid-19 et son impact chez les personnes en situation de précarité vivant en centre d’hébergement en France : premiers résultats de l’étude ECHO. Bull Epidémiol Hebd [Internet]. 2021 Jan 12 [cited 2021 Jan 20];Covid-19(N°1). Available from: http://beh.santepubliquefrance.fr/beh/2021/Cov_1/2021_Cov_1_1.html.

- Creswell, J., Plano Clark, V., 2020. Designing and conducting mixed methods research. Sage Publications, 3e édition. 457 p.

- Pires A., 1997. Échantillonnage et recherche qualitative : essai théorique et méthodologique;88.

- Graetz V., Rechel B., Groot W., Norredam M., Pavlova M. Utilization of health care services by migrants in Europe-a systematic literature review. Br. Med. Bull. 2017;121(1):5–18. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldw057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winters M., Rechel B., de Jong L., Pavlova M. A systematic review on the use of healthcare services by undocumented migrants in Europe. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2018;18(1):30. doi: 10.1186/s12913-018-2838-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandentorren S., Le Méner E., Oppenchaim N., Arnaud A., Jangal C., Caum C., Vuillermoz C., Martin-Fernandez J., Lioret S., Roze M., Le Strat Y., Guyavarch E. Characteristics and health of homeless families: the ENFAMS survey in the Paris region, France 2013. Eur. J. Public Health. 2016;26(1):71–76. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckv187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La I.D. santé des migrants et des minorités ethniques en Europe: Les recherches en cours. Hommes Migr. 2009;1282:136–150. [Google Scholar]

- Cognet M., Hamel C., Moisy M. Santé des migrants en France : l’effet des discriminations liées à l’origine et au sexe. Rev. Eur. Migr. Int. 2012;28(2):11–34. [Google Scholar]

- Bardin L., Chapitre I.I. Définition et rapport avec les autres sciences. Quadrige. 2013:30–51. [Google Scholar]

- Braun V., Clarke V., Hayfield N., Terry G. In: Handbook of Research Methods in Health Social Sciences. Liamputtong P., editor. Springer Singapore; Singapore: 2019. Thematic Analysis; pp. 843–860. 10.1007/978-981-10-5251-4_103. [Google Scholar]

- Allard-Poesi, F. Coder les données, 2003. In: Conduire un projet de recherche, une perspective qualitative [Internet]. Y. Giordano. EMS; 2003. p. 245–90. (Conduire un projet de recherche, une perspective qualitative). Available from: https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01495063.

- Negura L. L’analyse de contenu dans l’étude des représentations sociales. SociologieS [Internet]. 2006 Oct 22 [cited 2021 Jan 4]; Available from: http://journals.openedition.org/sociologies/993.

- Saubesty, C., 2006. Quels apports du codage des données qualitatives ? In Annecy, Genève. p. 25.

- Miles M., Huberman A. Analyse des données qualitatives. De Boeck Supérieur. 2003:630 p. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser, B.G., Strauss, A.L., 2010. The discovery of grounded theory: strategies for qualitative research. 5. paperback print. New Brunswick: Aldine Transaction; 2010. 271 p.

- Venuleo C., Marinaci T., Gennaro A., Palmieri A. The meaning of living in the time of COVID-19. a large sample narrative inquiry. Front. Psychol. 2020 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.577077. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.577077/full [cited 2021 Jan 6];11. Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourdeau-Lepage, L., 2020. Le confinement et ses effets sur le quotidien : Premiers résultats bruts des 1e et 2e semaines de confinement en France. HAL [Internet]; Available from: https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-02650456/.

- Fondation Abbé Pierre, 2020. FEANTSA. 5e regard sur le mal-logement en Europe [Internet]. 2020 Jul. Report No.: 05. Available from: https://www.feantsa.org/public/user/Resources/resources/Rapport_Europe_2020_FR.pdf.

- La P.L. In: Pandémie 2020: éthique, société, politique. Hirsch E., editor. Les éditions du Cerf; Paris: 2020. gestion de mise à l’abri des personnes à la rue face à l’épidémie de Covid. [Google Scholar]

- Yen-Hao Chu I., Alam P., Larson H.J., Lin L. Social consequences of mass quarantine during epidemics: a systematic review with implications for the COVID-19 response. J. Travel Med. 2020;13 doi: 10.1093/jtm/taaa192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santé Publique France, 2021. Covid-19 : une enquête pour suivre l’évolution des comportements et de la santé mentale pendant l’épidémie [Internet]. https://www.santepubliquefrance.fr. 2020 [cited 2021 Jan 6]. Available from: /etudes-et-enquetes/covid-19-une-enquête-pour-suivre-l’évolution-des-comportements-et-de-la-sante-mentale-pendant-l-epidemie.

- Ohlbrecht H., Jellen J. Unequal tensions: the effects of the coronavirus pandemic in light of subjective health and social inequality dimensions in Germany. Eur. Soc. 2021;23(sup1):S905–S922. [Google Scholar]

- Scarlett H., Davisse-Paturet C., Longchamps C., Aarbaoui T.E., Allaire C., Colleville A.-C., Convence-Arulthas M., Crouzet L., Ducarroz S., Melchior M. Depression during the COVID-19 pandemic amongst residents of homeless shelters in France. J. Affect Disord. Rep. 2021;6:100243. doi: 10.1016/j.jadr.2021.100243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiritus-Beerden E., Verelst A.n., Devlieger I., Langer Primdahl N., Botelho Guedes F., Chiarenza A., De Maesschalck S., Durbeej N., Garrido R., Gaspar de Matos M., Ioannidi E., Murphy R., Oulahal R., Osman F., Padilla B., Paloma V., Shehadeh A., Sturm G., van den Muijsenbergh M., Vasilikou K., Watters C., Willems S., Skovdal M., Derluyn I. Mental health of refugees and migrants during the COVID-19 pandemic: the role of experienced discrimination and daily stressors. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2021;18(12):6354. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18126354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organisation, 2021. COVID-19 Strategy update [Internet]. [cited 2021 Jul 29]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/covid-19-strategy-update.

- Académie nationale de médecine, Académie nationale de pharmacie, 2021. La précarité: un risque majoré de Covid-19 [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2021 Jun 29]. Available from: http://www.academie-medecine.fr/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/20.6.21-Covid-et-Pr%C3%A9carit%C3%A9.pdf.

- Tarasuk V., Dachner N., Poland B., Gaetz S. Food deprivation is integral to the “hand to mouth” existence of homeless youths in Toronto. Public Health Nutr. 2009;12(9):1437–1442. doi: 10.1017/S1368980008004291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Healy K. A theory of human motivation by Abraham H. Maslow (1942) Br. J. Psychiatry. 2016;208(4):313. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.115.179622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santé Publique France, 2021. Populations en grande précarité et Covid‑19: partage des connaissances pour améliorer la prévention et les actions [Internet]. [cited 2021 Jul 29]. Available from: https://www.santepubliquefrance.fr/les-actualites/2021/populations-en-grande-precarite-et-covid-19-partage-des-connaissances-pour-ameliorer-la-prevention-et-les-actions.

- Ataguba O.A., Ataguba J.E. Social determinants of health: the role of effective communication in the COVID-19 pandemic in developing countries. Glob Health Action. 2020;13(1):1788263. doi: 10.1080/16549716.2020.1788263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marmot M., Bell R. Fair society, healthy lives. Public Health. 2012;126:S4–S10. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2012.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]