Abstract

Salicylate hydroxylase (NahG) has a single redox site in which FAD is reduced by NADH, the O2 is activated by the reduced flavin, and salicylate undergoes an oxidative decarboxylation by a C(4a)-hydroperoxyflavin intermediate to give catechol. We report experimental results that show the contribution of individual pieces of the FAD cofactor to the observed enzymatic activity for turnover of the whole cofactor. A comparison of the kinetic parameters and products for the NahG-catalyzed reactions of FMN and riboflavin cofactor fragments reveal that the adenosine monophosphate (AMP) and ribitol phosphate pieces of FAD act to anchor the flavin to the enzyme and to direct the partitioning of the C(4a)-hydroperoxyflavin reaction intermediate towards hydroxylation of salicylate. The addition of AMP or ribitol phosphate pieces to solutions of the truncated flavins results in a partial restoration of the enzymatic activity lost upon truncation of FAD, and the pieces direct the reaction of the C(4a)-hydroperoxyflavin intermediate towards hydroxylation of salicylate.

Keywords: One-component flavoprotein monooxygenase, flavoenzyme, activation, oxidoreductases, biocatalysis

1. Introduction

Flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD) is found in about 75% of all flavoenzymes [1]. It contains an isoalloxazine ring that carries out the unique redox-type chemistry, and remote adenosine phosphoryl and ribitol phosphoryl groups that provide additional binding energy and specificity (Scheme 1). We are interested in defining the roles of the nonreacting pieces of FAD in catalysis of the reactions where FAD serves as a cofactor.

Scheme 1.

Flavin structures and rationale for FAD truncation into different pieces.

Oxidoreductases, which represent over 90% of all flavoproteins [1], use the isoalloxazine group to mediate one or two electron transfer reactions to O2 [2, 3]. We are working to understand the mechanism of action of salicylate hydroxylase (NahG). This enzyme is a one-component flavoprotein monooxygenase (FPMO) that belongs to group A according to phylogenetic classification [4, 5]. Catalysis involves the initial reaction between O2 and the reduced cofactor to form a labile C4a-hydroperoxyflavin oxygenating species (Scheme 2). In the absence of a hydroxyl group acceptor this intermediate decomposes to the oxidized flavin and H2O2 (uncoupled path). In the presence of salicylate the intermediate reacts with ipso hydroxylation to form the oxidized cofactor and a transient nonaromatic ring, which breaks down with loss of CO2 to give the monooxygenation reaction product catechol [3, 6]. The overall reaction is oxidative decarboxylation, where the flavin serves as oxidizing agent to generate the electrophilic oxygen involved in the electrophilic aromatic substitution for CO2 at salicylate (Scheme 2) [5, 7].

Scheme 2.

Steps and mechanism along the pathways catalyzed by salicylate hydroxylase (NahG) using FAD as prosthetic group: 1. decarboxylative oxidation of salicylate (coupled path); 2. formation of hydrogen peroxide from a FAD-hydroperoxide species (uncoupled path).

The C4a-hydroperoxiflavin features in many other transformations catalyzed by flavin-dependent monooxygenases. There are many important potential applications [5, 8–12] for the use of flavoenzymes to catalyze, for instance, the electrophilic aromatic hydroxylation at the ortho and para-position of substituted phenols [13], in decarboxylation, dehalogenation, and denitrification reactions [14–16]. Other uses include the electrophilic oxygenation of sulfur, selenium, boron, nitrogen, and phosphorus heteroatoms [10, 17], and stereoselective epoxidation of olefins [18, 19]. The C4a-hydroperoxiflavin may also feature a nucleophile peroxide moiety in Baeyer-Villiger reactions catalyzed by BVMOs [20, 21], and flavin N5-peroxide has been proposed as oxygen transferring species in some FMPOs [22], showing the great versatility and complexity of FPMO catalyzed reactions.

FAD contains a reactive functional tethered to an adenosyl group via a ribitol diphosphate (Scheme 1). There are at least three roles for the remote adenosine phosphoryl and ribitol phosphoryl tether for the flavin cofactor in reactions catalyzed by salicylate hydroxylase (NahG). (1) The binding energy of these groups may be used to stabilize the ground state Michaelis complex and anchor the flavin to this enzyme. (2) Effective catalysis by NahG requires the rapid reaction of the E•FADH•S complex to form the C4-ahydroperoxyflavin intermediate. This may be promoted by specificity in the expression of the binding energy for the adenosine phosphoryl and ribitol phosphoryl tether at the transition state for formation of the intermediate [23, 24]. (3) Effective catalysis by NahG requires the direction of the C4-ahydroperoxiflavin intermediate towards reaction with salicylate, and that the side reaction to form H2O2 be minimized. The binding energy from the adenosine phosphoryl and ribitol phosphoryl groups may be utilized to promote the productive reaction with salicylate, and to sequester the intermediate at a water-free enzyme active site.

We report the results of kinetic and product studies on the NahG-catalyzed reactions of the intact FAD cofactor and for the reactions of different combinations of FAD pieces. A comparison of the kinetic parameters for the NahG-catalyzed reactions of the whole FAD cofactor and for the cofactor pieces shows that the adenosine phosphate and ribitol phosphate pieces play a strong role in anchoring the flavin to this enzyme, and in directing the partitioning of C4a-hydroperoxyflavin reaction intermediate towards the hydroxylation of salicylate. The binding energy from the pieces is also utilized to activate NahG for catalysis of this reaction.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Materials

Flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD, disodium salt hydrate, > 95%), riboflavin 5′-monophosphate (FMN, sodium salt hydrate, 73–79% pure, < 6 % of free riboflavin and < 6% of riboflavin diphosphate), (−)-riboflavin (> 95%), adenosine 5′-monophosphate (AMP, disodium salt, >99 %), adenosine 5′-diphosphate (ADP, sodium salt, > 95 %), and β-nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide, reduced form (NADH, disodium salt, > 97 %) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich or Merck. Doubly de-ionized water with a conductivity of less than 17.3 μS cm was used to prepare all aqueous solutions. All other commercial chemicals were analytical grade and used without further purification.

2.2. Protein expression and purification

6xHis-NahG was overexpressed in E. coli Rosetta (DE3) competent cells (Novagen) from the recombinant expression vector pET28a(TEV)-nahg in the presence of 50 μg/mL kanamycin and 34 μg/mL chloramphenicol as described previously [7]. About 4.8 g of cell paste was obtained from one liter of growth media. Protein purification was carried out over a day at 4 °C and it is a slight modification of a previous method [7]. The frozen cell paste (~ 4.8 g) was resuspended in 30 mL of lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl buffer at pH 7.4, 1% w/v sucrose, 1% v/v Tween 20, 1% v/v glycerol, 0.25% w/v lysozyme) and cells were disrupted in an ice-water bath with three cycles of 30 s on/off sonication at 20kHz and 30% amplitude of a 750 W powered equipment. The lysate was clarified by centrifugation at 12,000 RPM for 30 min at 4 °C. The soluble fraction was immediately loaded onto a 10 mL Ni2+ affinity column (Chelating Sepharose Fast-Flow, GE Healthcare) connected to an ÄKTA start chromatography system (GE Healthcare). After sample loading, the column was washed with buffer A (50 mL, 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer at pH 7.4, 500 mM NaCl, 30 mM imidazole) and a linear gradient was applied using buffer A (100 mL) and buffer B (100 mL, 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer at pH 7.4, 500 mM NaCl, 500 mM imidazole) at 1.5 mL/min. Fractions containing the recombinant protein were pooled and buffer exchange was carried out with a HiPrep 26/10 Desalting (GE Healthcare) column using buffer C (60 mL, 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer at pH 7.4, 50 mM NaCl) at 1.5 mL/min. The resulting NahG samples were concentrated by ultrafiltration using Amicon® centrifugal filter units (10 kDa MWCO, GE Healthcare). The concentration of FAD that remains bound to protein throughout this purification was determined directly from the absorbance at 450 nm using ε = 11300 M−1 cm−1 for FAD [25]. The amount of FAD determined with this protocol agreed with absorbance measurements for solutions containing 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate for protein denaturation [26]. The total protein concentration was determined using the molar extinction coefficient of 76,890 M−1 cm−1 at 280 nm and correcting for the amount of protein bound FAD, using an extinction coefficient of 23,000 M−1 cm−1 for FAD at 280 nm. These measurements show that about 22 % of the total protein contains tightly bound FAD.

2.3. Kinetic studies

The consumption of NADH was monitored on a Cary50 spectrophotometer using 1 cm quartz cuvettes. The initial velocity (v) for ≤ 10% of NADH consumption at 25 °C was calculated from v = Δ[NADH]/Δt. The NADH concentration was determined at 305 nm (ε = 2,295 M−1 cm−1), 340 nm (ε = 6,220 M−1 cm−1) and 375 nm (ε = 1,663 M−1 cm−1). The wavelength was chosen to ensure that the total absorbance of all dissolved chromophores was ≤ 1.2. Reactions (1 mL) were performed at pH 8.5 in 56 mM Hepes, 1.1 mM EDTA, and NaCl to give an ionic strength of 0.21 M. All reactants, except for salicylate, were incubated for 2 min at 25 °C prior to initiating the reaction by addition of salicylate (10 μL from a 15 mM stock solution prepared in the same reaction buffer) using an add-mixer device. This procedure eliminates an initial slow event when the reactions at low flavin concentrations are initiated by the addition of enzyme. The corresponding kinetic parameters for reactions in the presence of increasing concentrations of exogenous riboflavin, FMN, FAD, AMP or ADP were determined using Equation 1, where [L] is the concentration of the flavin or adenosyl nucleotide and (v/[E])o is the basal activity when [L] = 0 M.

| (1) |

The kinetic data under increasing concentrations of NADH using exogenous riboflavin, FMN, and FAD (Flv) as cofactors were fitted to Equation 2, in which kcatFlv and KmFlv are the corresponding kinetic parameters for NADH in the presence of the exogenous flavin whereas the kcatFAD and KmFAD correspond to the kinetic parameters for the NahG tightly bound to FAD (E•FAD). The molar fraction for E•FAD (χE•FAD) was estimated as 0.22 using spectrophotometry (see the section 2.2) and for the NahG bound to the exogenous flavins (χE•Flv) were estimated from the corresponding Km and flavin concentrations (see Table 2).

| (2) |

Table 2.

Kinetic data for the effect of different flavins on the NADH oxidation and the oxidative decarboxylation of salicylate catalyzed by NahG at pH 8.5, I = 0.21 M (NaCl), and 25 °C. Errors are standard deviations.a

| Flavin as variable | χE•NADH | Km (μM) | kcatap (s−1) | kcatb (s−1) | % Yield of H2O2c | kcp or kcp ′ d (s−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FAD | 0.88 | 0.53 ± 0.05 | 9.6 ±0.2 | 16.6 ± 0.3 | 9 ± 1 (7.6 ±0.9) | 15.1 ± 0.4 |

| FMN | 0.50 | 2.4 ± 0.5 | 2.8 ± 0.2 | 8.4 ± 0.5 | 57 ±1 (45 ± 1) | 3.6 ± 0.2 |

| FMN + AMP 75 μM | 0.69 | 0.80 ± 0.05 | 4.6 ± 0.1 | 10.2 ± 0.2 | 20 ± 1 (17 ±1) | 8.1 ± 0.2 |

| Riboflavin | 0.39 | 26 ± 3 | 1.8 ± 0.1 | 7.0 ± 0.3 | 97 ± 1 (77 ± 1) | 0.19 ± 0.07 |

| Riboflavin + AMP 150 μM | 0.47 | 15 ± 3 | 3.7 ±0.2 | 12.2 ± 0.7 | 39 ±1 (31 ± 1) | 7.5 ± 0.4 |

| Riboflavin + ADP 410 μM | 0.56 | 4 ± 1 | 4.3 ± 0.3 | 11.7 ± 0.8 | 27 ± 2 (22 ± 2) | 8.5 ± 0.6 |

[NADH] = 200 µM and [Salicylate] = 150 µM;

Estimated considering kcatap/χFlv•NADH•Sal, where χFlv•NADH•Sal = χE•Flv χE•NADH χE•Sal. The χE•Flv = 0.78 under saturation conditions (see the section 3.1). The χE•NADH and χE•Sal were estimated from the corresponding Km values for NADH (refer to Figure S2 and Table S1) and salicylate (Km = 28 µM) [7]. The kcat values are uncorrected in regard the extent of the uncoupled path;

Values in parenthesis are the observed % yield of H2O2 considering the contribution of the apo NahG copurified with the tightly bound FAD (see the section 2.4);

Estimated from kcat considering the extent of the coupled path. The kcp and kcp’ are apparent rates for the coupled path in absence and presence of the adenosyl nucleotides, respectively.

2.4. Extent of uncoupling reactions

The oxidation of 400 μM NADH was monitored by UV-Vis spectroscopy at 25 °C under aerobic conditions in the presence of 0.3 μM NahG, 400 μM salicylate and either 20 μM FAD, 115 μM riboflavin or 75 μM FMN in the absence or presence of adenosyl nucleotides, at pH 8.5 and ionic strength of 0.21 M, as described above for the kinetic experiments. Following the complete consumption of NADH, the peroxide concentrations from the uncoupled path were determined in duplicate as described in a previous work [7]. This method provides 100 % of uncoupled reaction using benzoate as a nonreactive substrate to stimulate the oxidation of NADH. The observed degree of uncoupling (%obs) using salicylate as substrate considers the contributions of the degree of uncoupling’s for the NahG tightly bound to FAD (%FAD) and bound to the exogenous flavins (%Flv). The %FAD measured for the reaction with the apo NahG copurified with the tightly bound FAD (χE•FAD = 0.22) is 3.9 ± 0.4 %. The %Flv was estimated using Equation 3.

| (3) |

2.5. Fluorometric titrations

Flavin and salicylate binding to NahG was monitored on a fluorometer fitted with a magnetic stirring mechanism and a Peltier single cell holder at 25 °C. Quartz cuvettes of 1 cm pathlength and 3 mL capacity were set at 90-degree angle to the xenon light source. The excitation wavelength was 292 nm. The NahG solutions were buffered at pH 8.5 with 56 mM Hepes, 1.1 mM EDTA, and NaCl to give an ionic strength of 0.21 M. Titrant aliquots in the same buffer were added to the enzyme solution, mixed, and measured. The fluorescence data was corrected for dilution, which was lower than 5%.

The fluorescence data at 340 nm (flavin) and 410 nm (salicylate) for increasing concentrations of riboflavin, FMN, FAD, AMP or salicylate were used to determine the binding constants (Kd) from the nonlinear least-squares fits with Equation 4, in which the molar fraction (χbound) of the bound NahG was calculated by Equation 5. The Fobs, Ffree, Fbound represent the fluorescence intensities, respectively, for the observed, free, and fully bound enzyme, and [L]o and [E]o are the total concentrations of the ligand and enzyme, respectively.

| (4) |

| (5) |

3. Results

3.1. Kinetic experiments

The NahG co-purifies with 22% of a tightly bound FAD cofactor, whose concentration determined from the absorbance at 450 nm was the same in the absence and presence of 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate for protein denaturation [26]. This enzyme shows a v/[E] of 2.5 ± 0.1 s−1, which represents 21 % of the activity measured under a large excess of extraneous FAD. Attempts to remove the tightly bound cofactor by extensive dialysis1 resulted in loss of enzyme activity following the addition of extraneous FAD. On the other hand, as shown in Figure S1 in the Supporting Information, incubation of the apo NahG for 2 minutes at 25 °C with 0.4 μM FAD gives a FAD complex that can be displaced by FMN. Longer incubations of 4 hours at 25 °C or 6 days at 4 °C give a fully bound holoenzyme that cannot be displaced by FMN, similar to results obtained for FAD exchange experiments with other one-component FPMOs [12, 27]. Therefore, all experiments with NahG contained 22% tightly bound FAD and the remainder exogenous flavin bind to an exchangeable site subject of slow and essentially irreversible protein conformational change.

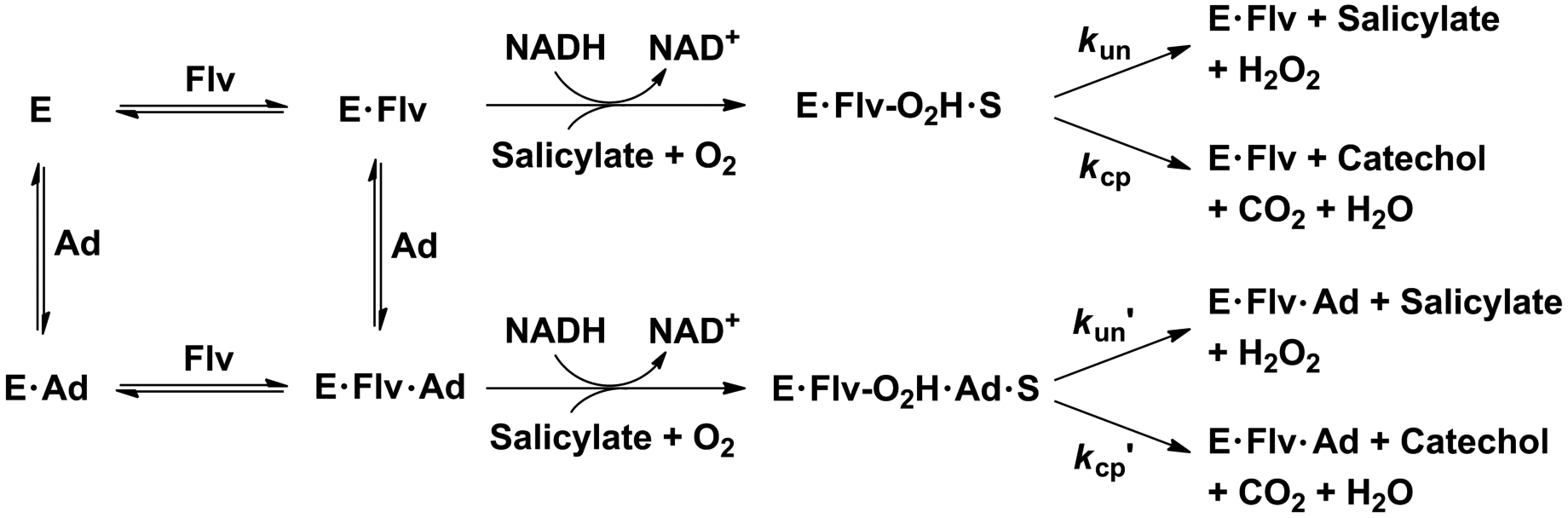

Scheme 3 depicts a panorama showing different species and pathways over the flavin (Flv) truncation and adenosyl nucleotide (Ad) activation for NahG. Figure 1 shows the effect of increasing the concentration of the adenosyl nucleotides on the reaction velocities (v/[E]) in excess of whole and truncated flavins. The reactions with FMN and riboflavin are accelerated by the addition of the adenosyl nucleotides showing hyperbolic profiles fitted to Equation 1 using the Michaelis-Menten constants (Km) and the apparent catalytic rate constant (kcatap) reported in Table 1. The adenosyl nucleotides have fairly small Km values in the micromolar range and show similar kcatap values when AMP and ADP are added to the reactions with FMN and riboflavin, respectively. These systems show the nearest structural features of FAD and provide greater activation in regard to the truncated flavins. It was shown in a control experiment that the value of v/[E] = 11.2 ± 0.1 s−1 for reactions at saturating [FAD] does not change upon addition of adenosyl nucleotides.

Scheme 3.

Pathways for the unactivated and adenosyl nucleotide-activated NahG-catalyzed reactions of truncated flavins (Flv), where kun and kcp are apparent rate constants for reactions of the salicylate•hydroperoxyflavin complex to yield H2O2, and catechol and CO2, respectively.

Figure 1.

Kinetic profiles for (a) AMP and (b) ADP activation of NahG-catalyzed oxidation of NADH (200 μM) in the presence of salicylate (150 μM) and riboflavin (■), FMN (●), or FAD (▲), at pH 8.5, I = 0.21 M (NaCl), and 25 °C. The solid lines show the fits of the data to Eq. 1 using the kinetic parameters reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Kinetic data for the effect of different adenosyl nucleotides on the oxidative decarboxylation of salicylate catalyzed by NahG bound to different flavins at pH 8.5, I = 0.21 M (NaCl), and 25 °C. Errors are standard deviations.

| Adenosyl nucleotides as variable | Km (μM) | kcatap(s−1) |

|---|---|---|

| FMN 25 μM + AMP | 22 ± 6 | 3.0 ± 0.2 |

| Riboflavin 80 μM + AMP | 13 ± 3 | 1.7 ± 0.1 |

| Riboflavin 80 μM + ADP | 45 ±10 | 3.2 ± 0.2 |

Figure 2 shows the effect of increasing the concentration of whole and truncated flavins on the v/[E] for reactions in absence and presence of the adenosyl nucleotides. A modest activity is observed for reactions in the absence of added cofactor, due to the presence of the tightly bound FAD copurified with salicylate hydroxylase. The limiting value of (v/[E])max determined at saturating cofactor concentrations decreases from 11.7 s−1 for FAD to 5.2 and 4.1 s−1 with FMN and riboflavin, respectively. This is accompanied by an increase in the Michaelis constant Km for the flavin.

Figure 2.

Kinetic profiles for exogenous (a) riboflavin, (b) FMN, and (c) FAD mediating the catalyzed oxidation of NADH (200 μM) by NahG in the presence of salicylate (150 μM) and in absence (■) and presence of AMP (○) and ADP (△) at pH 8.5, I = 0.21 M (NaCl), and 25 °C. Data fits were according to Eq. 1 and the kinetic parameters in Table 2.

The fits of the data from Figure 2 to the Michaelis-Menten equation give the values of the Michaelis constant Km and the apparent catalytic rate constant (kcatap) reported in Table 2. It was shown in control experiments that the value of v/[E] for reactions at saturating [FAD] does not change upon addition of activating adenosyl nucleotides. The value of kcatap includes the contribution of the coupled and uncoupled reaction pathways (Scheme 2) and underestimates the true value of kcat because the enzyme is not fully saturated by salicylate (Km = 28 μM) [7] and NADH (Km = 27 μM). The Michaelis-Menten parameters for NahG-catalyzed oxidation of NADH, determined for reactions in the absence and presence of the whole and truncated exogenous flavins, and in the absence and presence of the adenosyl nucleotides are shown in Figure S2 and Table S1 in the Supporting Information. Correction of kcatap = 9.6 s−1 for the partial saturation by NADH (χE•NADH = 0.88), salicylate (χE•Sal = 0.84) and the exogenous FAD (χE•Flv = 0.78) gives the true kcat = 16.6 s−1 for the FAD catalyzed reaction. This value is 4.7-fold higher than a previous determination reported by Costa et al. under the same conditions [7], but is close to the value of kcat = 21s−1 reported for the salicylate hydroxylase from P. putida S-1 [28].

Table 2 shows that the value of Km for the NahG-catalyzed reaction of FMN decreases from 2.4 μM for the unactivated reaction to 0.80 μM for the reaction activated by 75 μM AMP, while the Km for riboflavin decreases from 26 μM for the unactivated reaction to 15 μM and 4 μM for reactions in the presence of 150 μM AMP and 410 μM ADP activators, respectively.

3.4. Extent of uncoupling reactions

The C(4a)-hydroperoxyflavin intermediate, formed in the reaction of reduced FAD with dioxygen, partitions between productive hydroxylation of salicylate and nonproductive formation of hydrogen peroxide [29, 30]. Benzoate anion, a stable substrate analog, activates NahG for catalysis of cofactor oxidation to form hydrogen peroxide. The estimated yields of H2O2 from this reaction, determined by analyses of the H2O2 product, are 100 ± 2 % for FAD, 99 ± 3 % for FMN, and 100 ± 3 % for riboflavin. Table 2 shows that the partitioning of the C(4a)-hydroperoxyflavin intermediate in the presence of salicylate gives a 91% catechol/9% H2O2 ratio of product yields. Truncation of the cofactor has the effect of directing partitioning of the intermediate towards formation of H2O2 in the reactions of FMN (43% catechol/57% H2O2) and riboflavin (3% catechol/97% H2O2). The AMP and ADP activators redirect the reaction of the intermediate towards hydroxylation of salicylate. For example, product yields of (80% catechol/20% H2O2) and (61% catechol/39% H2O2) were determined, respectively, for the reaction of FMN and riboflavin in the presence of saturating [AMP]; and, a yield of (73% catechol/27% H2O2) was determined for hydroxylation of riboflavin in the presence of saturating [ADP].

The values of kcat determined for the reactions of FAD and the truncated cofactors are equal to the sum of the apparent rate constants for partitioning of the C(4a)-hydroperoxyflavin intermediate to form catechol (kcp) and hydrogen peroxide (kun). These rates can be estimated for salicylate hydroxylase from the product ratios and kcat values as the ipso-substitution at salicylate is rate-limiting according to free-energy relationships [7] and catechol shows a 250-fold weaker binding than salicylate implicating poor product inhibition [31]. In agreement with these observations, stopped-flow kinetic experiments for salicylate hydroxylase showed similar kcat and kcp values using salicylate as substrate [28, 32]. Table 2 shows the apparent rates for the coupled path in the absence (kcp) and presence (kcp’) of the adenosyl nucleotides as estimated from product ratios and kcat values. The value of kcp by the whole FAD cofactor, 15.1 s−1, is 4.2 and 78-fold larger than for the unactivated reactions of truncated FMN and riboflavin cofactors, respectively. Addition of AMP activator to the unactivated NahG-catalyzed reaction of FMN causes a nearly 2.2-fold increase in kcp = 3.6 s−1, while addition of AMP or ADP activators cause 39 and 45-fold increases, respectively, in kcp = 0.19 s−1 for the unactivated reaction of riboflavin.

3.5. Fluorometric titrations

Flavin, AMP, and salicylate binding to NahG were monitored under different conditions (Table 3). Figure S3 shows the fluorescence data over increasing concentrations of FMN and FAD showing quenching at 340 nm for the characteristic emission of the tryptophan residues in the protein. Non-linear fitting to Equation 4 gives Kd values of 2.2 ± 0.2 μM and 0.036 ± 0.008 μM for FMN and FAD, respectively. This value for FAD is in the range reported in a previous determination (Kd = 0.002 μM) [7] and for the salicylate hydroxylase from P. putida S-1 (Kd = 0.045 μM) [31]. Addition of 150 μM AMP (Figure S3) or 5 μM salicylate (Figure S4) does not change the Kd for FMN. The corresponding studies over increasing concentration of riboflavin are depicted in Figure S5 and shows modest saturation up to 43 μM either in the absence and presence of 150 μM AMP or 410 μM ADP. Aggregation is well known to occur under high concentrations of riboflavin and may be associated to changes in spectral properties [33], which may preclude the Kd determination for this flavin using fluorometry. Titration of the E•FMN complex with increasing concentrations of AMP also produces fluorescence quenching at 340 nm (Figure S6). The data fitted to Equation 4 gives a Kd of 13 ± 1 μM, which is similar to the Km of 22 μM estimated using kinetics (Table 1).

Table 3.

Dissociation constants (Kd) for NahG complexes with different ligands as measured using fluorometric titration at pH 8.5, I = 0.21 M (NaCl), and 25 °C. Errors are standard deviations.

| System | Kd (μM) |

|---|---|

| FAD | 0.036 ± 0.008 |

| FMN | 2.2 ± 0.2 |

| FMN in the presence of 150 μM AMP | 2.8 ± 0.4 |

| FMN in the presence of 5 μM salicylate | 3.7 ± 0.5 |

| AMP in the presence of 20 μM FMN | 13 ± 1 |

| Salicylate | 0.28 ± 0.03 |

| Salicylate in the presence of 14 μM FAD | 0.38 ± 0.02 |

The salicylate binding to NahG was evaluated in the absence and presence of exogenous FAD (Figure S7). Excitation of salicylate at 292 nm gives the emission at 410 nm associated with the intramolecular proton transfer in the excited state (ESIPT) from the ortho-phenol to the carboxylic acid moiety [34]. The fluorescence data over increasing concentrations of salicylate in the presence of exogenous FAD was fitted to Equation 4 to give a Kd of 0.38 ± 0.02 μM, which is similar to a previous determination under the same conditions (Kd of 0.22 μM) [7] and that determined in the absence of exogenous FAD (Kd = 0.28 ± 0.03 μM). This data shows no improvement in salicylate binding but a considerable increase of fluorescence intensity in the presence of FAD.

4. Discussion

The value of Km = 0.53 μM for reaction with exogenous FAD is close to the value of Km = 0.15 μM determined in an earlier study using the same reaction conditions [7]. The v/[E] of 2.5 s−1 for the salicylate hydroxylase copurified with a tightly bound FAD represents 21 % of the activity measured under large concentrations of FAD to saturate NahG (≫ Km). This fraction matches the amount of tightly bound FAD copurified with the enzyme and implicates that its activity in vitro may be recomposed to the same level. This observation is similar to an earlier report using the same enzyme purified from a pseudomonad [25], and contrasts with FAD concentrations near to the Km. In this case, we observe some reversibility and longer periods of incubation to tightly bind FAD. This is consistent with an stepwise process in flavin binding, where the rapid formation of a relatively weak complex is followed by a slow, essentially irreversible protein conformational change, as has been observed for the flavodoxin from Azotobacter vinelandii [35]. Previous fluorometric studies with the oxidized FAD report Kd values in the range of 2–45 nM [7, 31, 36]. Herein, we have estimated a Kd of 36 ± 8 nM using fluorometry (Table 3). This complex is expected to be about 5-orders of magnitude stronger with the reduced FAD as reported by electrochemical studies with the salicylate hydroxylase from P. cepacia [36].

4.1. Effect of flavin truncation

We have found that in addition to FAD, FMN and riboflavin also show good activity as cofactors in NahG-catalyzed reactions. The broad specificity of salicylate hydroxylase for truncated forms of FAD has not previously been noted for other one-component flavoprotein monooxygenases (FPMOs). For instance, the strict requirement for FAD has been reported to 6-hydroxynicotinate 3-monooxygenase from P. fluorescens TN5 [37], 3-hydroxybenzoate 6-hydroxylase from P. cepacia [38], 4-aminobenzoate hydroxylase from Agaricus bisporus [39], 4-hydroxybenzoate hydroxylase from P. fluorescens [40], and salicylate hydroxylase from P. putida S-1 [41], which utilize a tightly bound FAD prosthetic group [12, 27]. By comparison, two-component FPMOs use FAD, FMN, or both, depending on the protein catalyst; and, catalyze the monooxygenase reaction and subsequent regeneration of the reduced flavin at separate enzyme binding sites [12, 27, 42]. In other words, catalysis by two-component FPMOs requires migration of the flavin between protein binding sites, while one-component FPMOs carry out the reductase and monooxygenase reactions at a single site. The observation of activity for riboflavin in the reactions catalyzed by other FPMOs is rare.

The contribution of the adenosine monophosphate and ribitol phosphate pieces to the activity of the whole cofactor FAD has been estimated by comparing the enzyme activities for catalysis of the whole cofactor and for catalysis of the reactions FMN and riboflavin fragments (Figure 2 and Table 2). These pieces contribute as follows to the activity of the whole substrate.

Deletion of the AMP moiety from FAD results in a 4.5-fold increase in Km for the reaction of the truncated FMN cofactor, and deletion of the ADP moiety results in a 49-fold increase in Km for the reaction of the truncated riboflavin cofactor (Table 2). These data provide evidence that AMP and ADP pieces contribute with 0.9 and 2.3 kcal/mol, respectively, to the Gibbs free binding energy of the whole cofactor FAD. These contributions are small in comparison to the expected intrinsic nucleotide binding energies.

Truncation of the FAD cofactor causes the ratio of product yields to decrease from 91% catechol/9% H2O2for the reaction of FAD, to (43% catechol/57% H2O2) and (3% catechol/97% H2O2), respectively, for the reactions of the FMN and riboflavin cofactors. This shows that binding of the AMP and ADP nucleotide fragments assists in protecting the C(4a)-hydroperoxyflavin intermediate from unproductive decomposition into oxidized flavin and H2O2.

The AMP and ADP pieces at FAD result in 4.2-fold and 78-fold increases, respectively, for FMN and riboflavin apparent rates (kcp) for partitioning of the C(4a)-hydroperoxyflavin intermediate to form catechol. These data provide evidence that AMP and ADP pieces contribute with 0.9 and 2.6 kcal/mol, respectively, to the Gibbs free energy of activation of the E•FAD•S complex. In contrast, FMN and riboflavin cofactors cause similar 2-fold and 2.4-fold decreases, respectively, in the value of kcat for FAD, so that major of the effect of these pieces in the redox processes is on the hydroxylation of the substrate.

4.2. Activation by exogenous adenosyl nucleotides

The full cofactor is required for observation of optimal activity, but we observed that a small portion of the total intrinsic binding energy of the adenosyl nucleotide group is used to activate the flavin moiety. Recovers are best with AMP and ADP, which may be regarded as decoy molecules to the reactions with FMN and riboflavin, respectively, and occur even in absence of a strong connection between these pieces. Reports for other flavoenzymes are scarce but point out similar conclusions. Vanillyl-alcohol oxidase displays similar affinity for FAD and ADP, suggesting that the ADP moiety plays a major role in cofactor recognition [43, 44]. Inorganic phosphate accelerates and stabilize the formation of the E•Riboflavin complex of the flavodoxin FMN-dependent from D. vulgaris [45]. The contribution of FMN fragments in the E•FMN complex of the flavodoxin FMN-dependent from Anabaena sp. has been estimated to be greatest for the phosphate fragment (7 kcal/mol) in relation to the isoalloxazine ring (5–6 kcal/mol) and ribityl moiety (~1 kcal/mol) [46]. Other examples include the use of remote nonreacting parts to drive conformational changes that activate the reaction in flexible proteins [24]. A notable case is phosphite dianion activation to the reactions of phosphodianion-truncated substrates of orotidine 5’-monophophate decarboxylase (OMPDC) [47], triosephosphate isomerase (TIM) [48], and glycerol phosphate dehydrogenase (GPDH) [49]. Other examples include the coenzyme A fragment of acetyl-CoA [50, 51], the ADP-ribose fragment of NAD/NADH [52], the pyrophosphate and tripolyphosphate fragments of ADP and ATP, respectively [53].

In the best scenarios, addition of AMP to the reaction with FMN causes a 3-fold decrease on the Km for FMN and a value only 1.5-fold above in relation to FAD. The effect of AMP and ADP to the reaction with riboflavin decreases the Km by 1.7 and 6.5-fold, respectively, but provide a Km value 8-fold higher than FAD (Table 2). These observations reveal the greater effect of the ribitol phosphate group in regard to the adenosine monophosphate group to activate the capture of FAD into the E•FAD complexes along the reaction path. These recoveries largely direct the partitioning towards the substrate hydroxylation, what indicates that the adenosyl nucleotide moieties may have an indirect structural role that prevents the C(4a)-hydroperoxyflavin from solvent-induced breakdown into H2O2 and the oxidized flavins [54]. A likely scenario has been suggested by one reviewer to explain this observation. Evidence from NMR studies indicate that substrate binding lower the solvent accessibility of the isoalloxazine ring of the flavin [55] and, therefore, the adenosyl nucleotides could improve substrate binding and prevent the partitioning towards H2O2 formation. The stronger fluorescence intensity for salicylate in the presence of FAD (Figure S7) also supports the lower solvent accessibility but similar Kd values for salicylate in absence and presence of FAD are more consistent with the substrate binding not being affected by the flavin. Similarly, the binding affinity for FMN does not change in the presence of salicylate or AMP whereas AMP shows a strong affinity by the enzyme (Table 3). These observations are evidence of independent sites at the protein for the adenosyl nucleotide, flavin, and substrate binding. Therefore, independent binding sites but distinct kinetic effects of the adenosyl nucleotides to direct the partitioning towards substrate hydroxylation is an indication that these adenosyl nucleotides may tune dynamical events that lead the C4a-hydroperoxyflavin from a solvent excluded protein environment to a more solvent exposed state as reported by others [56, 57]. An interesting example is observed to the arabino-FAD reconstituted 4HBH, in which the isoalloxazine group adopts preferably an “out” solvent exposed conformation related to greater amounts of uncoupling reaction in regard to the native FAD bound enzyme [57].

Similar to the above effects on Km, addition of AMP to reactions using riboflavin and FMN recover 39 and 2.2-fold of enzyme turnover, respectively, whereas a 45-fold activation was observed for the riboflavin reaction using ADP (Table 2). These observations are in agreement to previous studies that implicates the interaction between the adenosine phosphate and the side chain of a highly conserved Arg (R111 in NahG) in the isoalloxazine redox chemistry in most FPMOs [27, 54, 56, 58–60]. It shall be noted that the absence of inhibition or activation over increasing concentrations of ADP and AMP to the reaction catalyzed using FAD as cofactor (Figure 1) is strong evidence that the adenosyl nucleotides have no apparent competition with the NADH binding site despite of sharing the same adenosyl moieties.

4.3. Additivity of binding energies

The Kd value for the oxidized FMN corresponds to 7.7 kcal/mol of the total binding energy of the FAD-enzyme complex. Estimation of this value from Kd gives a total binding energy of about 10 kcal/mol for the bound oxidized FAD. Therefore, the estimated binding energy for the AMP moiety in FAD is only 2.3 kcal/mol. Intriguingly, the Kd for AMP corresponds to a Gibbs free energy of 6.7 kcal/mol, suggesting that most of the activation by the adenosyl nucleotides occurs in the steps following binding of the oxidized flavin. Next, we rationalize the meaning of this large difference.

In most cases, the product of binding constants of the individual component pieces in a bigger molecule are larger than observed to the whole (e.g. A and B parts in A-B), so KAB/KAKB > 1 as result of the entropic cost to bring the two pieces together [23]. The ratios for the binding affinities (1/Kd) in K FAD/KFMNKAMP is 7.9 × 10−4 M corresponding to an entropic barrier for binding of about 4 kcal/mol for FAD in relation to the pieces. This entropic barrier for FAD binding suggests a stepwise mechanism, in which the path between the weakly and the tightly bound catalytic active states show some strain not observed for binding of the pieces. However, as observed in Table 2, addition of AMP or salicylate does not affect the Kd for FMN suggesting independent binding sites with no apparent remote capacity of the adenosyl nucleotide or the substrate to improve binding of the flavin moiety in FAD.

4.4. Recognition of the pieces

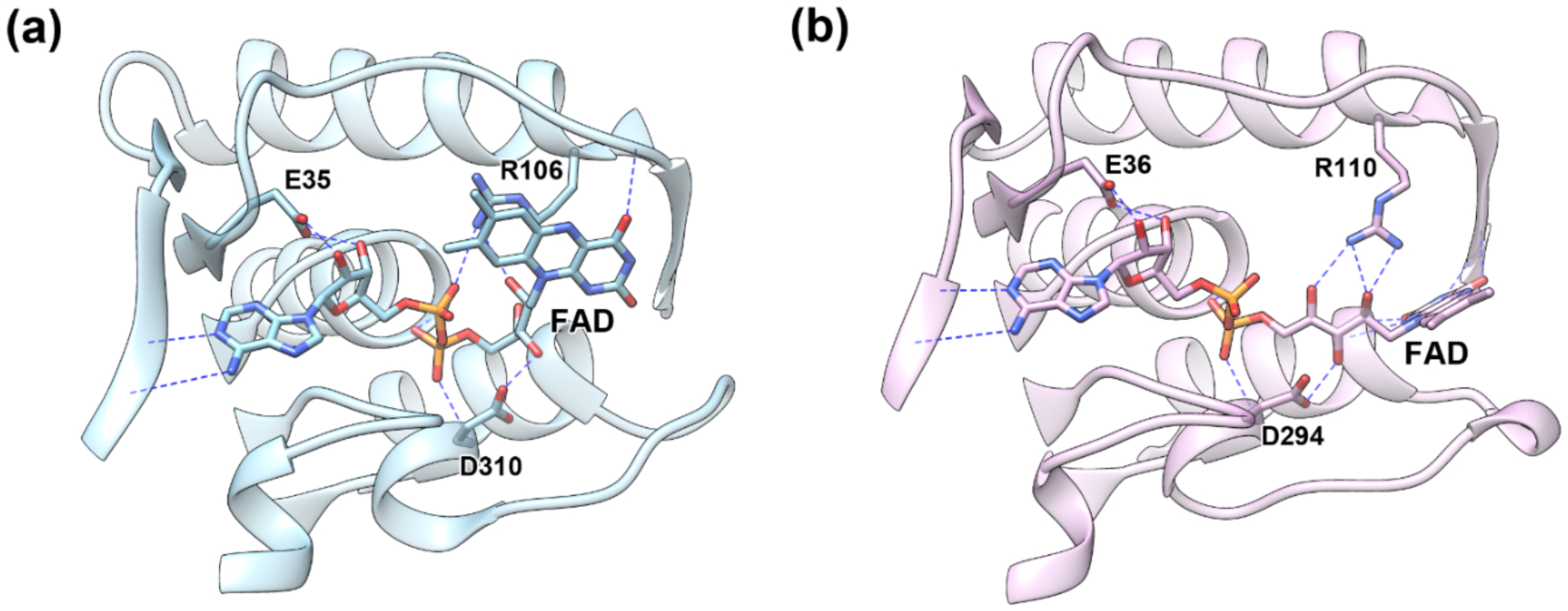

A large set of crystallographic structures for one-component FPMOs has been accumulated since the first report in 1979 for this group of enzymes [61], including the salicylate hydroxylase from P. putida G7 (PDB entry 6BZ5) [7] and S-1 (PDB entry 5EVY) [62], 4-hydroxybenzoate hydroxylase (4HBH, PDB entry 1K0L) [58] and flavin-containing monooxygenase (PhzS, PDB entry 2RGJ) from Pseudomonas aeruginosa [63], and 3-hydroxybenzoate 6-hydroxylase from Rhodococcus jostii RHA1 (3HB6H, PDB entry 4BJZ) [64]. Figure 3 shows a superimposition of representative structures, which offer a view of the interactions during flavin binding and catalysis. Recognition of the adenosyl nucleotide moiety of FAD occurs in a conserved dinucleotide binding domain (Rossmann fold) [12, 27], while the isoalloxazine group swings at the ribityl hinge between two different positions [56, 65] - “in” and “out” - involved in the redox chemistry of the flavin [54, 57–60, 66]. The “out” position is implicated in the reduction of the isoalloxazine group by NAD(P)H [28, 42], whereas the “in” position is related to oxidative processes that culminate in the formation of the C4a-hydroperoxiflavin and substrate hydroxylation. We next discuss what interactions allow NahG to discriminate between FAD and the truncated flavins providing the remote activation by the adenosyl nucleotides pieces.

Figure 3.

Homologs flavoproteins showing different conformational states at the FAD binding cleft: (a) “out” and (b) “in” states for FAD bound homologs showing the corresponding loop in PhzS from Pseudomonas aeruginosa (PDB entry 3C96) and 3HB6H from Rhodococcus jostii (PDB entry 4BJZ) in different positions, respectively.

Deletion of the ribitol phosphoryl group from FMN gives riboflavin and results in lost interactions between the backbone NH groups of residues S18 and D314 and affords greater Km values (11-fold) and degree of uncoupling by about 50%. Deletion of a more remote adenosine monophosphoryl group from FAD yields FMN and greater Km values (6-fold) and degree of uncoupling by about 48%. This AMP piece contributes with about 2.3 kcal/mol of the total binding energy for binding the oxidized FAD, which is underestimated by a 4 kcal/mol entropic barrier for FAD binding. These effects are consistent with strong interactions in the adenosine binding site, including hydrogen bond interactions between backbone atoms of K131 and the adenine ring, the ribose hydroxyl groups and the side chain of E38, and the adenosine phosphoryl group and the side chain of R111 when an “out” conformation prevails. It is reasonable that missing interactions with R111 result in an imbalance between the “in” and “out” conformations that provides larger degrees of uncoupling and lower apparent rates for substrate hydroxylation. Breakdown of the C4a-hydroperoxiflavin towards the oxidized flavin and H2O2 occurs typically in a solvent exposed environment afforded by the “out” conformation or by diffusion of the flavin into the bulky solution [58, 59]. Crystallography studies with arabino-FAD reconstituted 4HBH have shown that the isoalloxazine group adopts preferably the “out” conformation which is related to faster flavin reduction by NADPH but also higher amounts of uncoupling reaction in regard to the native FAD bound enzyme [57]. These observations suggest that the adenosyl nucleotide moieties in FAD may play an important role in flavin dynamics.

In agreement with the role of R111 in the isoalloxazine group dynamics between the “in” and “out” conformations, addition of AMP or ADP to reactions using riboflavin as cofactor recover about 2.2 kcal/mol of enzyme turnover for the hydroxylation rate of the substrate in relation to the 2.6 kcal/mol effect caused by truncation of FAD into riboflavin. Addition of AMP to the reaction using FMN recover 0.5 kcal/mol of the 0.9 kcal/mol due to the truncation of FAD into FMN. However, these contributions represent only a fraction of the 15.8 kcal/mol Gibbs free energy of activation for the whole FAD cofactor, suggesting that most of the activation remains in the ribitol and in the isoalloxazine group. Dissection of these pieces’ contribution needs further evaluation.

5. Conclusions

Because flavin binding and catalysis in most one-component FPMOs depends on highly dynamical events, several reactants and steps, key interactions are required to attain all pieces in the active-site in the proper orientation. FAD truncation into FMN and riboflavin weakens binding and the NahG capacity to productively promote the salicylate oxygenation from the C4a-hydroperoxyflavin intermediate, which disproportionate through the uncoupled path more promptly in the order FAD < FMN < Riboflavin. Addition of the nucleotides AMP and ADP to the reaction with the truncated flavins recovers the extent and rate of the coupled path to levels comparable to the reaction using FAD. Over these events, the entropic barrier for binding the individual component pieces is comparatively small in regard to FAD. In the holo enzyme complex, the adenosine monophosphoryl group contributes to drive FAD into a stiff and active form for tight interactions. Finally, new potential tools for biocatalytic applications of flavoproteins have been examined, an interesting example includes the use of NAD(P)H analogs to carry out the flavin reduction [67]. The advantage of adding remote adenosyl nucleotides to truncated flavins adds a new asset for application of one-component FPMOs, for instance, to substitute the costly FAD by cheaper options like riboflavin and to consider less labor-intensive approaches to get synthetic cofactor analogs. A likely advantage may be the use of synthetic flavins to tune the redox potential [68, 69] and allow different capabilities to flavoenzymes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment.

We acknowledge INCT-Catalysis, FAPEMIG, and the National Institutes of Health Grants GM134881 for financial support of this work. We are also grateful to Capes (Brazil) for a scholarship to MSP.

ABBREVIATIONS:

- NahG

salicylate hydroxylase with 6xHis N-terminal tag

- FAD

Flavin adenine dinucleotide

- FMN

riboflavin 5′-monophosphate

- AMP

adenosine 5′-monophosphate

- ADP

adenosine 5′-diphosphate

- NADH

β-nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide, reduced form

ENZYMES

- Salicylate hydroxylase (NahG)

EC 1.14.13.1

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest. The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material. Kinetic profiles for incubation studies with FAD. Michaelis-Menten parameters for NADH. Fluorometric titration data used to estimate the Kd values in Table 3. Data for every kinetic profile in Figures 1 and 2.

NahG 2 mg/mL was dialyzed against Tris hydrochloride 50 mM (pH 7.5) at 4 °C with 6 buffer exchanges over a period of 48 hours. Cellulose membrane dialysis tubing with 14 K MWCO were used. Typical ratios between protein and dialysis buffer solutions were 1/1000.

References

- [1].Macheroux P, Kappes B, Ealick SE, Flavogenomics – a genomic and structural view of flavin-dependent proteins, FEBS J 278(15) (2011) 2625–2634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Massey V, Activation of molecular oxygen by flavins and flavoproteins, J. Biol. Chem 269(36) (1994) 22459–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Romero E, Gómez Castellanos JR, Gadda G, Fraaije MW, Mattevi A, Same substrate, many reactions: Oxygen activation in flavoenzymes, Chem. Rev 118(4) (2018) 1742–1769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Westphal AH, Tischler D, van Berkel WJH, Natural diversity of FAD-dependent 4-hydroxybenzoate hydroxylases, Arch. Biochem. Biophys 702 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Paul CE, Eggerichs D, Westphal AH, Tischler D, van Berkel WJH, Flavoprotein monooxygenases: Versatile biocatalysts, Biotechnol. Adv (2021) 107712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Bruice TC, Mechanisms of flavin catalysis, Acc. Chem. Res 13(8) (1980) 256–262. [Google Scholar]

- [7].Costa DMA, Gomez SV, de Araujo SS, Pereira MS, Alves RB, Favaro DC, Hengge AC, Nagem RAP, Brandao TAS, Catalytic mechanism for the conversion of salicylate into catechol by the flavin-dependent monooxygenase salicylate hydroxylase, Int. J. Biol. Macromol 129 (2019) 588–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Dong J, Fernández-Fueyo E, Hollmann F, Paul CE, Pesic M, Schmidt S, Wang Y, Younes S, Zhang W, Biocatalytic oxidation reactions: A chemist’s perspective, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 57(30) (2018) 9238–9261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Holtmann D, Fraaije MW, Arends IW, Opperman DJ, Hollmann F, The taming of oxygen: biocatalytic oxyfunctionalisations, Chem. Comm 50(87) (2014) 13180–13200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Rioz-Martínez A, Kopacz M, De Gonzalo G, Pazmino DET, Gotor V, Fraaije MW, Exploring the biocatalytic scope of a bacterial flavin-containing monooxygenase, Org. Biomol. Chem 9(5) (2011) 1337–1341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Pazmino DT, Winkler M, Glieder A, Fraaije M, Monooxygenases as biocatalysts: classification, mechanistic aspects and biotechnological applications, J. Biotechnol 146(1) (2010) 9–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].van Berkel WJH, Kamerbeek NM, Fraaije MW, Flavoprotein monooxygenases, a diverse class of oxidative biocatalysts, J. Biotechnol 124(4) (2006) 670–689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Meyer A, Held M, Schmid A, Kohler HPE, Witholt B, Synthesis of 3-tert-butylcatechol by an engineered monooxygenase, Biotechnol. Bioeng 81(5) (2003) 518–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Osborne RL, Raner GM, Hager LP, Dawson JH, C-fumago chloroperoxidase is also a dehaloperoxidase: Oxidative dehalogenation of halophenols, J. Am. Chem. Soc 128(4) (2006) 1036–1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Zhao H, Chen D, Li Y, Cai B, Overexpression, purification and characterization of a new salicylate hydroxylase from naphthalene-degrading Pseudomonas sp. strain ND6, Microbiol. Res 160(3) (2005) 307–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].van Pee KH, Unversucht S, Biological dehalogenation and halogenation reactions, Chemosphere 52(2) (2003) 299–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Jensen CN, Cartwright J, Ward J, Hart S, Turkenburg JP, Ali ST, Allen MJ, Grogan G, A flavoprotein monooxygenase that catalyses a Baeyer-Villiger reaction and thioether oxidation using NADH as the nicotinamide cofactor, ChemBioChem 13(6) (2012) 872–878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Sucharitakul J, Tongsook C, Pakotiprapha D, van Berkel WJH, Chaiyen P, The Reaction Kinetics of 3-Hydroxybenzoate 6-Hydroxylase from Rhodococcus jostii RHA1 Provide an Understanding of the para-Hydroxylation Enzyme Catalytic Cycle, J. Biol. Chem 288(49) (2013) 35210–35221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Gross R, Buehler K, Schmid A, Engineered catalytic biofilms for continuous large scale production of n-octanol and (S)-styrene oxide, Biotechnol. Bioeng 110(2) (2013) 424–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Pazmino DET, Dudek HM, Fraaije MW, Baeyer-Villiger monooxygenases: recent advances and future challenges, Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol 14(2) (2010) 138–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Bisagni S, Summers B, Kara S, Hatti-Kaul R, Grogan G, Mamo G, Hollmann F, Exploring the Substrate Specificity and Enantioselectivity of a Baeyer-Villiger Monooxygenase from Dietzia sp. D5: Oxidation of Sulfides and Aldehydes, Top. Catal 57(5) (2014) 366–375. [Google Scholar]

- [22].Toplak M, Matthews A, Teufel R, The devil is in the details: The chemical basis and mechanistic versatility of flavoprotein monooxygenases, Arch. Biochem. Biophys 698 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Jencks WP, On the attribution and additivity of binding energies, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 78(7) (1981) 4046–4050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Richard JP, Protein flexibility and stiffness enable efficient enzymatic catalysis, J. Am. Chem. Soc 141(8) (2019) 3320–3331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Yamamoto S, Katagiri M, Maeno H, Hayaishi O, Salicylate Hydroxylase, a Monooxygenase Requiring Flavin Adenine Dinucleotide: I. Purification and General Properties, J. Biol. Chem 240(8) (1965) 3408–3413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Entsch B, Palfey BA, Ballou DP, Massey V, Catalytic Function of Tyrosine Residues in p-Hydroxybenzoate Hydroxylase as Determined by the Study of Site-Directed Mutants, J. Biol. Chem 266(26) (1991) 17341–17349. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Chenprakhon P, Wongnate T, Chaiyen P, Monooxygenation of aromatic compounds by flavin-dependent monooxygenases, Protein Sci 28(1) (2019) 8–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Takemori S, Nakamura M, Suzuki K, Katagiri M, Nakamura T, Mechanism of the salicylate hydroxylase reaction. V. Kinetic analyses, Biochim. Biophys. Acta 284(2) (1972) 382–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].White-Stevens RH, Kamin H, Studies of a flavoprotein, salicylate hydroxylase. I. Preparation, properties, and the uncoupling of oxygen reduction from hydroxylation, J. Biol. Chem 247(8) (1972) 2358–2370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].White-Stevens RH, Kamin H, Uncoupling of oxygen activation from hydroxylation in a bacterial salicylate hydroxylase, Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 38(5) (1970) 882–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Suzuki K, Takemori S, Katagiri M, Mechanism of the salicylate hydroxylase reaction. IV. Fluorometric analysis of the complex formation, Biochim. Biophys. Acta 191(1) (1969) 77–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Wang L-H, Tu S-C, The kinetic mechanism of salicylate hydroxylase as studied by initial rate measurement, rapid reaction kinetics, and isotope effects, J. Biol. Chem 259(17) (1984) 10682–10688. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Astanov S, Sharipov MZ, Fayzullaev AR, Kurtaliev EN, Nizomov N, Spectroscopic study of photo and thermal destruction of riboflavin, J. Mol. Struct 1071 (2014) 133–138. [Google Scholar]

- [34].Kovi PJ, Miller CL, Schulman SG, Biprotonic versus intramolecular phototautomerism of salicylic acid and some of its methylated derivatives in the lowest excited singlet state, Anal. Chim. Acta 61(1) (1972) 7–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Bollen YJ, Westphal AH, Lindhoud S, van Berkel WJH, van Mierlo CPM, Distant residues mediate picomolar binding affinity of a protein cofactor, Nat. Commun 3(1) (2012) 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Einarsdottir GH, Stankovich MT, Tu SC, Studies of electron-transfer properties of salicylate hydroxylase from Pseudomonas cepacia and effects of salicylate and benzoate binding, Biochemistry 27(9) (1988) 3277–3285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Nakano H, Wieser M, Hurh B, Kawai T, Yoshida T, Yamane T, Nagasawa T, Purification, characterization and gene cloning of 6-hydroxynicotinate 3-monooxygenase from Pseudomonas fluorescens TN5, Eur. J. Biochem 260(1) (1999) 120–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Wang LH, Hamzah RY, Yu Y, Tu SC, Pseudomonas cepacia 3-hydroxybenzoate 6-hydroxylase: induction, purification, and characterization, Biochemistry 26(4) (1987) 1099–1104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Tsuji H, Ogawa T, Bando N, Sasaoka K, Purification and properties of 4-aminobenzoate hydroxylase, a new monooxygenase from Agaricus bisporus, J. Biol. Chem 261(28) (1986) 13203–13209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Howell LG, Spector T, Massey V, Purification and properties of p-hydroxybenzoate hydroxylase from Pseudomonas fluorescens, J. Biol. Chem 247(13) (1972) 4340–4350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Katagiri M, Yamamoto S, Hayaishi O, Flavin Adenine Dinucleotide Requirement for Enzymic Hydroxylation and Decarboxylation of Salicylic Acid, J. Biol. Chem 237(7) (1962) PC2413–PC2414. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Huijbers MME, Montersino S, Westphal AH, Tischler D, van Berkel WJH, Flavin dependent monooxygenases, Arch. Biochem. Biophys 544 (2014) 2–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Fraaije MW, van den Heuvel RHH, van Berkel WJH, Mattevi A, Structural analysis of flavinylation in vanillyl-alcohol oxidase, J. Biol. Chem 275(49) (2000) 38654–38658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Jin J, Mazon H, van den Heuvel RHH, Heck AJ, Janssen DB, Fraaije MW, Covalent flavinylation of vanillyl-alcohol oxidase is an autocatalytic process, Febs J 275(20) (2008) 5191–5200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Pueyo JJ, Curley GP, Mayhew SG, Kinetics and thermodynamics of the binding of riboflavin, riboflavin 5’-phosphate and riboflavin 3’,5’-bisphosphate by apoflavodoxins, Biochem. J 313 (1996) 855–861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Lostao A, El Harrous M, Daoudi F, Romero A, Parody-Morreale A, Sancho J, Dissecting the energetics of the apoflavodoxin-FMN complex, J. Biol. Chem 275(13) (2000) 9518–9526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Richard JP, Amyes TL, Reyes AC, Orotidine 5’-Monophosphate Decarboxylase: Probing the Limits of the Possible for Enzyme Catalysis, Acc. Chem. Res 51(4) (2018) 960–969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Amyes TL, Richard JP, Enzymatic catalysis of proton transfer at carbon: activation of triosephosphate isomerase by phosphite dianion, Biochemistry 46(19) (2007) 5841–5854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Tsang W-Y, Amyes TL, Richard JP, A substrate in pieces: Allosteric activation of glycerol 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (NAD+) by phosphite dianion, Biochemistry 47(16) (2008) 4575–4582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Fierke CA, Jencks WP, Two functional domains of coenzyme A activate catalysis by coenzyme A transferase. Pantetheine and adenosine 3’-phosphate 5’-diphosphate, J. Biol. Chem 261(17) (1986) 7603–7606. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Whitty A, Fierke CA, Jencks WP, Role of binding energy with coenzyme A in catalysis by 3-oxoacid coenzyme A transferase, Biochemistry 34(37) (1995) 11678–11689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Plapp BV, Charlier HA Jr, Ramaswamy S, Mechanistic implications from structures of yeast alcohol dehydrogenase complexed with coenzyme and an alcohol, Arch. Biochem. Biophys 591 (2016) 35–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Kerns SJ, Agafonov RV, Cho Y-J, Pontiggia F, Otten R, Pachov DV, Kutter S, Phung LA, Murphy PN, Thai V, The energy landscape of adenylate kinase during catalysis, Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol 22(2) (2015) 124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Ballou DP, Entsch B, Cole LJ, Dynamics involved in catalysis by single-component and two-component flavin-dependent aromatic hydroxylases, Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 338(1) (2005) 590–598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Vervoort J, van Berkel WJH, Muller F, Moonen CTW, NMR-Studies on para-Hydroxybenzoate Hydroxylase from Pseudomonas fluorescens and Salicylate Hydroxylase from Pseudomonas putida, Eur. J. Biochem 200(3) (1991) 731–738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Gatti DL, Palfey BA, Lah MS, Entsch B, Massey V, Ballou DP, Ludwig ML, The mobile flavin of 4-OH benzoate hydroxylase, Science 266(5182) (1994) 110–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].van Berkel WJH, Eppink MHM, Schreuder HA, Crystal-Structure of p-Hydroxybenzoate Hydroxylase Reconstituted with the Modified Fad Present in Alcohol Oxidase from Methylotrophic Yeasts: Evidence for an Arabinoflavin, Protein Sci 3(12) (1994) 2245–2253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Wang J, Ortiz-Maldonado M, Entsch B, Massey V, Ballou D, Gatti DL, Protein and ligand dynamics in 4-hydroxybenzoate hydroxylase, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 99(2) (2002) 608–613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Manenda MS, Picard M-È, Zhang L, Cyr N, Zhu X, Barma J, Pascal JM, Couture M, Zhang C, Shi R, Structural analyses of the Group A flavin-dependent monooxygenase PieE reveal a sliding FAD cofactor conformation bridging OUT and IN conformations, J. Biol. Chem 295(14) (2020) 4709–4722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Entsch B, Cole LJ, Ballou DP, Protein dynamics and electrostatics in the function of p-hydroxybenzoate hydroxylase, Arch. Biochem. Biophys 433(1) (2005) 297–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Wierenga RK, Dejong RJ, Kalk KH, Hol WGJ, Drenth J, Crystal Structure of p-Hydroxybenzoate Hydroxylase, J. Mol. Biol 131(1) (1979) 55–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Uemura T, Kita A, Watanabe Y, Adachi M, Kuroki R, Morimoto Y, The catalytic mechanism of decarboxylative hydroxylation of salicylate hydroxylase revealed by crystal structure analysis at 2.5 Å resolution, Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 469(2) (2016) 158–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Greenhagen BT, Shi K, Robinson H, Gamage S, Bera AK, Ladner JE, Parsons JF, Crystal structure of the pyocyanin biosynthetic protein PhzS, Biochemistry 47(19) (2008) 5281–5289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Montersino S, Orru R, Barendregt A, Westphal AH, van Duijn E, Mattevi A, van Berkel WJ, Crystal structure of 3-hydroxybenzoate 6-hydroxylase uncovers lipid-assisted flavoprotein strategy for regioselective aromatic hydroxylation, J. Biol. Chem 288(36) (2013) 26235–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Schreuder HA, Mattevi A, Obmolova G, Kalk KH, Hol WGJ, Vanderbolt FJT, van Berkel WJH, Crystal-Structures of Wild-Type p-Hydroxybenzoate Hydroxylase Complexed with 4-Aminobenzoate, 2,4-Dihydroxybenzoate, and 2-Hydroxy-4-Aminobenzoate and of the Tyr222Ala Mutant Complexed with 2-Hydroxy-4-Aminobenzoate. Evidence for a Proton Channel and a New Binding Mode of the Flavin Ring, Biochemistry 33(33) (1994) 10161–10170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Entsch B, van Berkel WJH, Structure and Mechanism of p-Hydroxybenzoate Hydroxylase, Faseb J 9(7) (1995) 476–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Guarneri A, Westphal AH, Leertouwer J, Lunsonga J, Franssen MCR, Opperman DJ, Hollmann F, van Berkel WJH, Paul CE, Flavoenzyme-mediated Regioselective Aromatic Hydroxylation with Coenzyme Biomimetics, ChemCatChem 12(5) (2020) 1368–1375. [Google Scholar]

- [68].Ortiz-Maldonado M, Ballou DP, Massey V, Use of free energy relationships to probe the individual steps of hydroxylation of p-hydroxybenzoate hydroxylase: Studies with a series of 8-substituted flavins, Biochemistry 38(25) (1999) 8124–8137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Ortiz-Maldonado M, Gatti D, Ballou DP, Massey V, Structure-function correlations of the reaction of reduced nicotinamide analogues with p-hydroxybenzoate hydroxylase substituted with a series of 8-substituted flavins, Biochemistry 38(50) (1999) 16636–16647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.