Abstract

Objectives

We investigated whether spousal caregivers’ greater perception of being appreciated by their partner for their help was associated with caregivers’ better mental health and whether caregivers’ higher role overload was related to their poorer mental health. We further evaluated whether spousal caregivers’ greater perceived gratitude buffered the association between their role overload and mental health.

Methods

We examined 306 spousal caregivers of older adults with chronic illness or disability, drawn from the 2011 National Health and Aging Trends Study and National Study of Caregiving. We defined mental health as better psychological well-being and less psychological distress (i.e., fewer depressive and anxiety symptoms). Hierarchical regression models were estimated to test hypotheses.

Results

Greater perceived gratitude was associated with better psychological well-being, and higher role overload was related to poorer psychological well-being and greater psychological distress. In addition, greater perceived gratitude buffered the associations between role overload and anxiety symptoms as well as psychological well-being.

Discussion

Findings suggest that spousal caregivers’ role overload may be a strong risk factor for their poorer mental health, especially when caregivers feel less appreciated by their partner. Couple-oriented interventions to improve spousal caregivers’ mental health could be aimed at reducing their role overload and enhancing perceived gratitude.

Keywords: Appreciation, Caregiving, Marriage, Well-being

Individuals who receive benefits from another person often feel gratitude toward the benefactor (Emmons, 2008). Although spousal caregivers help their partner with various tasks, little is known about whether spousal caregivers’ perception of being appreciated by their partner for their help relates to their own mental health. According to the find-remind-and-bind theory, gratitude helps to bind the people in the relationship closer together (Algoe, 2012). Indeed, one’s felt or expressed gratitude toward his/her partner related to the partner’s greater relationship connection and satisfaction (Algoe et al., 2010; Gordon et al., 2011), which is linked to lower depressive symptoms and better life satisfaction (Beach et al., 2003; Carr et al., 2014). Furthermore, expressed gratitude increased prosocial behaviors of the benefactor by enhancing the feeling of being valued by others (Grant & Gino, 2010). Given the positive effects of gratitude on personal and relational well-being, we hypothesized that spousal caregivers’ greater perceived gratitude was associated with their better mental health.

We also focused on spousal caregivers’ role overload, a subjective caregiving stressor that represents caregivers’ appraisals of the extent to which the care demands are depleting their time and energy (Pearlin et al., 1990). Role overload specifically taps caregivers’ feelings of having more to do than they can handle, whereas caregiver burden encompasses broader caregiving stressors in various domains including health and finances (Zarit et al., 1986). According to the stress process model (Pearlin et al., 1990), caregivers’ higher role overload contributes to their poorer mental health via increased intrapsychic strains (i.e., low mastery). The association between role overload and depressive symptoms was found in spousal caregivers of Alzheimer’s patients (Mausbach et al., 2012) and informal caregivers of functionally disabled older adults, including those with dementia (Yates et al., 1999). It remains unclear whether role overload is also a risk factor for poor mental health among spousal caregivers of older adults without dementia. Considering that stressors for caregivers may vary by the care recipient’s health conditions (Bertrand et al., 2006), this study examined whether higher role overload is associated with poorer mental health among spousal caregivers of older adults without dementia. In line with the stress process model (Pearlin et al., 1990), we hypothesized that spousal caregivers’ higher role overload was associated with their poorer mental health.

According to the stress process model, caregivers’ psychosocial resources attenuate the impact of caregiving stressors on health (Pearlin et al., 1990). Perceived gratitude may be an important psychosocial resource for spousal caregivers, given that spouses who feel appreciated may feel valued and satisfied with their relationship (Algoe et al., 2010; Gordon et al., 2011; Grant & Gino, 2010) rather than focus on their role overload. Thus, we hypothesized that greater perceived gratitude attenuated the negative association between role overload and mental health. We operationalized mental health as greater psychological well-being and less psychological distress (i.e., depressive and anxiety symptoms).

Method

Participants

This study used data from the 2011 National Health and Aging Trends Study (NHATS) and National Study of Caregiving (NSOC). If participants reported in NHATS that their spouse or cohabiting partner helped them with mobility, self-care, and/or household chores in the past month, we included them as spousal caregivers in the sample (N = 422). Of these, we excluded six who did not reside with their partner, 70 who cared for their partner with dementia, and 40 who had missing data on at least one analytic variable. Thus, the analytic sample consisted of 306 spousal caregivers with complete data on study variables who care for their partner without dementia (see Supplementary Table 1 for demographic information and scores on study variables). This study was reviewed by the Pennsylvania State University Institutional Review Board (IRB # STUDY00016565).

Measures

Perceived gratitude

Spousal caregivers’ perceived gratitude was measured with one item: “How much does the care recipient appreciate what you do for him/her?” The item was rated from 1 (a lot) to 4 (not at all) and reverse coded, with higher scores indicating greater perceived gratitude (M = 3.83, SD = 0.56).

Role overload

Spousal caregivers’ role overload was assessed with three items derived from the Role Overload scale (Pearlin et al., 1990). The following items were rated from 1 (very much) to 3 (not so much): “You are exhausted when you go to bed at night,” “You have more things to do than you can handle,” and “You don’t have time for yourself.” These items were reverse coded and averaged, with higher scores indicating higher role overload (α = 0.74; M = 1.52, SD = 0.58).

Mental health

Spousal caregivers’ depressive and anxiety symptoms were measured with the two-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-2; Kroenke et al., 2009) and the two-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder scale (GAD-2; Kroenke et al., 2009), respectively. Both scales were modified in NSOC to examine the past 1-month period rather than a 2-week period. Items were rated from 1 (not at all) to 4 (nearly every day) and averaged within each scale, with higher scores indicating greater depressive (α = 0.61; M = 1.52, SD = 0.66) and anxiety symptoms (α = 0.58; M = 1.51, SD = 0.67). The reliability coefficients in this study were lower than those reported in a general population study (PHQ-2’s α = 0.78, GAD-2’s α = 0.75; Löwe et al., 2010), but comparable to that reported in a study of older adults (PHQ-2’s α = 0.57; Mogle et al., 2020) that also modified the original questionnaire to examine the past 1-month period.

Spousal caregivers’ psychological well-being was assessed with the three items derived from the Ryff Scales of Psychological Well-Being (Ryff, 1989; Ryff et al., 1995). The following items were rated from 1 (agree strongly) to 4 (disagree strongly): “My life has meaning and purpose,” “In general, I feel confident and good about myself,” and “I like my living situation very much.” These items were reverse coded and averaged, with a higher score indicating better psychological well-being (α = 0.69; M = 3.59, SD = 0.55).

Covariates

Covariates included caregivers’ age (in years), sex (0 = male, 1 = female), educational attainment (1 = no schooling completed to 9 = masters, professional, or doctoral degree), and duration of relationship (in years). We also controlled for caregivers’ self-rated health measured with one item (1 = excellent to 5 = poor), which was reverse coded. Furthermore, we covaried for caregivers’ assistance with their partner’s activities of daily living (range = 0–5) and instrumental activities of daily living (range = 0–6) to account for the effect of objective caregiving stressors on mental health (Pearlin et al., 1990).

Statistical Analysis

We tested our hypotheses using hierarchical regression models. Covariates, predictors, and an interaction term (Perceived Gratitude × Role Overload) were entered in each step. All continuous predictors and covariates were grand-mean centered. For significant interactions, simple slopes were estimated at the 10th and 90th percentiles of grand-mean centered perceived gratitude, representing high and low perceived gratitude, respectively. We included the NSOC sampling analytic weight in the regression models to adjust for different probabilities of sample selection and responding to NSOC (Kasper et al., 2016). We also accounted for clustering and stratification of NSOC’s sample design to compute standard errors appropriately. Due to the skewness of three outcome variables that ranged from −1.79 to 1.37, we repeated the regression analyses with square-root transformed outcome variables. All the effects of interest did not differ substantially; thus, we report nontransformed results to ease interpretation.

Results

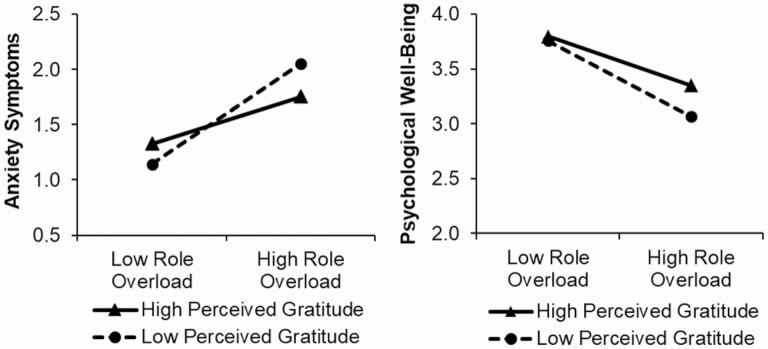

As given in Table 1, greater perceived gratitude was associated with better psychological well-being (β = 0.18, p = .01), but not with depressive (β = −0.06, p = .20) or anxiety symptoms (β = −0.09, p = .16), partially supporting our first hypothesis. Consistent with our second hypothesis, higher role overload was associated with more depressive (β = 0.30, p < .001) and anxiety symptoms (β = 0.35, p < .001) as well as lower psychological well-being (β = −0.40, p < .001). In partial support of our third hypothesis, perceived gratitude moderated the effect of role overload on anxiety symptoms (β = −0.20, p = .001) and psychological well-being (β = 0.12, p = .03), but not on depressive symptoms (β = −0.06, p = .26). Simple slopes analyses showed that the associations between role overload and anxiety symptoms were significant among both caregivers with low and high perceived gratitude, but the magnitude of the association was greater among caregivers with low perceived gratitude (B = 0.68, p < .001) than those with high perceived gratitude (B = 0.32, p < .001; Figure 1). Similarly, the associations between role overload and psychological well-being were significant among both caregivers with low and high perceived gratitude, but the magnitude of the association was greater among caregivers with low perceived gratitude (B = −0.52, p < .001) than those with high perceived gratitude (B = −0.34, p < .001; Figure 1). The effect sizes of the interaction term for anxiety symptoms (f2 = 0.05) and psychological well-being (f2 = 0.02) were small.

Table 1.

Associations Between Spousal Caregivers’ Perceived Gratitude, Role Overload, and Mental Health

| Depressive symptoms | Anxiety symptoms | Psychological well-being | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor | β (SE) | ∆R2 | β (SE) | ∆R2 | β (SE) | ∆R2 | |

| Step 1 | Intercept | — (0.04)*** | 0.15 | — (0.04)*** | 0.16 | — (0.03)*** | 0.19 |

| CG sex (female) | 0.18 (0.06)*** | 0.27 (0.07)*** | −0.16 (0.07)* | ||||

| CG age (years) | −0.02 (0.00) | 0.04 (0.01) | 0.04 (0.00) | ||||

| CG educational attainment | 0.01 (0.02) | 0.08 (0.01) | −0.08 (0.02) | ||||

| CG years married/in relationship | 0.03 (0.00) | −0.01 (0.00) | −0.14 (0.00)** | ||||

| CG self-rated health | −0.22 (0.04)** | −0.28 (0.03)*** | 0.26 (0.04)** | ||||

| CG ADL assistance | 0.17 (0.03)* | 0.07 (0.02) | −0.22 (0.03)* | ||||

| CG IADL assistance | 0.10 (0.03) | 0.04 (0.02) | −0.05 (0.02) | ||||

| Step 2 | CG role overload | 0.30 (0.08)*** | 0.07 | 0.35 (0.07)*** | 0.10 | −0.40 (0.08)*** | 0.15 |

| CG perceived gratitude | −0.06 (0.06) | −0.09 (0.09) | 0.18 (0.08)* | ||||

| Step 3 | CG role overload × CG perceived gratitude | −0.06 (0.09) | 0.00 | −0.20 (0.10)** | 0.03 | 0.12 (0.09)* | 0.01 |

| Total R2 | 0.22 | 0.30 | 0.35 |

Notes: CG = caregiver; ADL = activities of daily living; IADL = independent activities of daily living. All models were survey-adjusted and weighted. Estimates are presented from each step of the model.

*p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

Figure 1.

The moderating effect of spousal caregivers’ perceived gratitude on the association between their role overload and mental health. Notes: Spousal caregivers’ role overload was plotted along the x-axes, and their mental health outcomes were plotted along the y-axes. The values of low and high role overload were −0.52 and 0.81, which were 10th and 90th percentiles of grand-mean centered role overload, respectively. Similarly, the values of spousal caregivers’ low and high perceived gratitude were −0.83 and 0.17, which were 10th and 90th percentiles of grand-mean centered perceived gratitude, respectively. Each grand-mean centered covariate equaled zero and caregiver sex was fixed at its mean.

Discussion

This finding of the positive association between perceived gratitude and psychological well-being is in line with previous research showing that individuals who perceived their partners’ gratitude as more responsive showed greater improvement in their psychological well-being over time (Algoe & Zhaoyang, 2016). However, we found no association between perceived gratitude and psychological distress. This may be explained by the fact that positive social interactions relate to psychological well-being rather than distress among older adults (Finch et al., 1989). Given that perceiving gratitude is a positive social interaction in general (Algoe, 2012), spousal caregivers who perceive greater gratitude may have better psychological well-being but not necessarily feel fewer depressive or anxiety symptoms than those who perceive less gratitude.

We also found that higher role overload was associated with more psychological distress and poorer psychological well-being, supporting the stress process model (Pearlin et al., 1990). These findings extend existing studies of caregivers of older adults with Alzheimer’s disease or functional disability (Mausbach et al., 2012; Yates et al., 1999), indicating that role overload is a risk factor for poorer mental health among spousal caregivers of older adults with chronic health conditions other than dementia. Our findings also suggest that spousal caregivers’ role overload—rather than perceived gratitude—may have more pervasive impacts on their mental health, considering its more consistent and stronger associations with all three outcomes.

Yet, the impact of role overload on psychological well-being was attenuated by perceived gratitude. This finding is in line with the evidence that spousal caregivers’ help was related to their greater positive affect when caregivers perceived that their help increased the partner’s well-being (Monin et al., 2017). We also found that perceived gratitude buffered the impact of role overload on anxiety symptoms, but not on depressive symptoms. One explanation is that perceived gratitude may elevate caregiving mastery, which more strongly mitigates the effect of caregiving stressors on anxiety symptoms than on depressive symptoms (Pioli, 2010). The effect sizes of interactions were small. Still, given that spousal caregivers help their partner in everyday life, the effect of perceived gratitude may accumulate over time and have a clinical impact on caregiver mental health.

Several limitations of this study should be noted. First, causal associations cannot be determined in this cross-sectional study. Second, caregivers’ race was not assessed in the 2011 NSOC, and thus we were unable to account for potential racial differences in spousal caregivers’ mental health. Third, most spousal caregivers in this study chose the most positive answer option (i.e., a lot) when rating how much their partner appreciates their help, which suggests that a ceiling effect might have occurred. Furthermore, our sample reported high psychological well-being and low psychological distress on average. Therefore, our findings may not generalize to spousal caregivers who do not feel appreciated or are more distressed. Fourth, the role overload items were not specific to caregiving, and thus caregivers’ overload might occur from other responsibilities (e.g., work). Fifth, reliability coefficients for the anxiety and depressive symptoms measures were low. Thus, our findings should be replicated with more reliable measures of psychological distress. Last, we did not examine the mechanisms through which perceived gratitude is related to psychological well-being. Future research might investigate potential mediators (e.g., marital satisfaction or caregiving mastery) that explain how perceived gratitude influences psychological well-being.

Despite these limitations, to our best knowledge, this study is the first to examine the effects of caregivers’ perceived gratitude and role overload on their mental health, controlling for the effects of each other. If replicated, our findings suggest that spousal caregivers’ role overload may be a strong risk factor for their poorer mental health, especially when caregivers feel less appreciated by their partner. Couple-oriented interventions to improve spousal caregivers’ mental health could be aimed at reducing their role overload and enhancing perceived gratitude.

Supplementary Material

Funding

The preparation of this manuscript was supported by the National Institute on Aging (R01 AG063241, R03 AG067006).

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

Data Availability

Information on obtaining the data utilized in this study is described at https://nhats.org/researcher/data-access. Analytic methods will be provided upon request to the first author. This study was not preregistered.

References

- Algoe, S. B. (2012). Find, remind, and bind: The functions of gratitude in everyday relationships. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 6(6), 455–469. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-9004.2012.00439.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Algoe, S. B., Gable, S. L., & Maisel, N. C. (2010). It’s the little things: Everyday gratitude as a booster shot for romantic relationships. Personal Relationships, 17(2), 217–233. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6811.2010.01273.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Algoe, S. B., & Zhaoyang, R. (2016). Positive psychology in context: Effects of expressing gratitude in ongoing relationships depend on perceptions of enactor responsiveness. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 11(4), 399–415. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2015.1117131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beach, S. R. H., Katz, J., Kim, S., & Brody, G. H. (2003). Prospective effects of marital satisfaction on depressive symptoms in established marriages: A dyadic model. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 20(3), 355–371. doi: 10.1177/0265407503020003005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand, R. M., Fredman, L., & Saczynski, J. (2006). Are all caregivers created equal? Stress in caregivers to adults with and without dementia. Journal of Aging and Health, 18(4), 534–551. doi: 10.1177/0898264306289620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr, D., Freedman, V. A., Cornman, J. C., & Schwarz, N. (2014). Happy marriage, happy life? Marital quality and subjective well-being in later life. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 76(5), 930–948. doi: 10.1111/jomf.12133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emmons, R. A. (2008). Gratitude, subjective well-being, and the brain. In Eid M. & Larsen R. J. (Eds.), The science of subjective well-being (pp. 469–492). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Finch, J. F., Okun, M. A., Barrera, M.Jr, Zautra, A. J., & Reich, J. W. (1989). Positive and negative social ties among older adults: Measurement models and the prediction of psychological distress and well-being. American Journal of Community Psychology, 17(5), 585–605. doi: 10.1007/BF00922637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon, C. L., Arnette, R. A. M., & Smith, R. E. (2011). Have you thanked your spouse today? Felt and expressed gratitude among married couples. Personality and Individual Differences, 50(3), 339–343. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2010.10.012 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grant, A. M., & Gino, F. (2010). A little thanks goes a long way: Explaining why gratitude expressions motivate prosocial behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 98(6), 946–955. doi: 10.1037/a0017935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasper, J. D., Freedman, V. A., & Spillman, B. (2016). National study of caregiving user guide.Johns Hopkins University School of Public Health.https://nhats.org/sites/default/files/2021-01/NSOC%20USER%20GUIDE%20Revised%2012_12_17.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., Williams, J. B., & Löwe, B. (2009). An ultra-brief screening scale for anxiety and depression: The PHQ-4. Psychosomatics, 50(6), 613–621. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.50.6.613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Löwe, B., Wahl, I., Rose, M., Spitzer, C., Glaesmer, H., Wingenfeld, K., Schneider, A., & Brähler, E. (2010). A 4-item measure of depression and anxiety: Validation and standardization of the Patient Health Questionnaire-4 (PHQ-4) in the general population. Journal of Affective Disorders, 122(1–2), 86–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.06.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mausbach, B. T., Roepke, S. K., Chattillion, E. A., Harmell, A. L., Moore, R., Romero-Moreno, R., Bowie, C. R., & Grant, I. (2012). Multiple mediators of the relations between caregiving stress and depressive symptoms. Aging & Mental Health, 16(1), 27–38. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2011.615738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mogle, J., Hill, N. L., Bhargava, S., Bell, T. R., & Bhang, I. (2020). Memory complaints and depressive symptoms over time: A construct-level replication analysis. BMC Geriatrics, 20(1), 57. doi: 10.1186/s12877-020-1451-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monin, J. K., Poulin, M. J., Brown, S. L., & Langa, K. M. (2017). Spouses’ daily feelings of appreciation and self-reported well-being. Health Psychology, 36(12), 1135–1139. doi: 10.1037/hea0000527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin, L. I., Mullan, J. T., Semple, S. J., & Skaff, M. M. (1990). Caregiving and the stress process: An overview of concepts and their measures. The Gerontologist, 30(5), 583–594. doi: 10.1093/geront/30.5.583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pioli, M. F. (2010). Global and caregiving mastery as moderators in the caregiving stress process. Aging & Mental Health, 14(5), 603–612. doi: 10.1080/13607860903586193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryff, C. D. (1989). Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57(6), 1069–1081. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.57.6.1069 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ryff, C. D., & Keyes, C. L. (1995). The structure of psychological well-being revisited. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69(4), 719–727. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.69.4.719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yates, M. E., Tennstedt, S., & Chang, B. H. (1999). Contributors to and mediators of psychological well-being for informal caregivers. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 54(1), 12–22. doi: 10.1093/geronb/54b.1.p12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarit, S. H., Todd, P. A., & Zarit, J. M. (1986). Subjective burden of husbands and wives as caregivers: A longitudinal study. The Gerontologist, 26(3), 260–266. doi: 10.1093/geront/26.3.260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Information on obtaining the data utilized in this study is described at https://nhats.org/researcher/data-access. Analytic methods will be provided upon request to the first author. This study was not preregistered.