Abstract

BACKGROUND:

In the WHI-HT trials (Women’s Health Initiative Hormone Therapy), treatment with oral conjugated equine estrogens and medroxyprogesterone acetate (CEE+MPA) resulted in increased risk of coronary heart disease (CHD), whereas oral conjugated equine estrogens (CEE) did not.

METHODS:

Four hundred eighty-one metabolites were measured at baseline and at 1-year in 503 and 431 participants in the WHI CEE and CEE+MPA trials, respectively. The effects of randomized HT on the metabolite profiles at 1-year was evaluated in linear models adjusting for baseline metabolite levels, age, body mass index, race, incident CHD, prevalent hypertension, and diabetes. Metabolites with discordant effects by HT type were evaluated for association with incident CHD in 944 participants (472 CHD cases) in the WHI-OS (Women’s Health Initiative Observational Study), with replication in an independent cohort of 980 men and women at high risk for cardiovascular disease.

RESULTS:

HT effects on the metabolome were profound; 62% of metabolites significantly changed with randomized CEE and 52% with CEE+MPA (false discovery rate–adjusted P value<0.05) in multivariable models. Concerted increases in abundance were seen within various metabolite classes including triacylglycerols, phosphatidylethanolamines, and phosphatidylcholines; decreases in abundance was observed for acylcarnitines, lysophosphatidylcholines, quaternary amines, and cholesteryl/ cholesteryl esters. Twelve metabolites had discordant effects by HT type and were associated with incident CHD in the WHI-OS; a metabolite score estimated in a Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator regression was associated with CHD risk with an odds ratio of 1.47 per SD increase (95% CI, 1.27–1.70, P<10−6). All twelve metabolites were altered in the CHD protective direction by CEE treatment. One metabolite (lysine) was significantly altered in the direction of increased CHD risk by CEE+MPA; the remaining 11 metabolites were not significantly changed by CEE+MPA. The CHD associations of a subset of 4 metabolites including C58:11 triacylglycerol, C54:9 triacylglycerol, C36:1 phosphatidylcholine and sucrose replicated in an independent dataset of 980 participants in the PREDIMED trial (Prevención con Dieta Mediterránea).

CONCLUSIONS:

Randomized treatment with oral HT resulted in large metabolome shifts that generally favored CEE alone over CEE+MPA in term of CHD risk. Discordant metabolite effects between HT regimens may partially mediate the differences in CHD risk between the 2 WHI-HT trials.

Keywords: cardiovascular disease, estrogens, heart disease, medroxyprogesterone acetate, metabolome, women

In the WHI-HT trials (Women’s Health Initiative Hormone Therapy), treatment with oral conjugated equine estrogens and medroxyprogesterone acetate (CEE+MPA) resulted in a 29% increased risk of coronary heart disease (CHD), whereas treatment with oral conjugated equine estrogens alone (CEE) was associated with a nonsignificant 9% reduction in CHD.1–3 During the randomized treatment, CEE+MPA also resulted in increased risk of invasive breast cancer, stroke, pulmonary embolism, dementia (in women aged ≥65 years), gallbladder disease, and urinary incontinence, whereas it reduced hip fractures, colorectal cancer, and diabetes.3 In the CEE alone trial, higher risk of stroke, reduced risk of hip fracture, and a trend toward decreased risk of breast cancer resulted with randomized therapy.3 Differences in the effects of these 2 HT regimens on metabolomic profiles is largely unknown and such differences might mediate differences in outcomes.

Metabolites in body fluids reflect multiple biochemical processes relevant to health and disease.4 Recent advances in metabolite profiling techniques (metabolomics) have enhanced our ability to measure a full profile of small-molecule metabolites, thus, providing a comprehensive picture of an individual’s metabolic status. Metabolite measures closely reflect the underlying molecular pathways governing various disease processes and thus enhance our understanding of the cause of complex disorders. Differences in HT effects on metabolomic profiles and their association with CHD may shed light on the determinants of the observed differences in CHD and other disease outcomes between the CEE+MPA and CEE clinical trials in the WHI.

We sought to characterize the effects of randomized HT on the metabolome and evaluate whether these changes might explain the differences in CHD outcomes between the 2 trials. We utilized 2 independent datasets from a metabolomics of CHD case-control study nested within the WHI.5 A total of 934 participants in the WHI-HT had metabolomic profiles measured at baseline and at year 1 following randomization and had no prior cardiovascular disease (CVD); metabolite changes were compared between the active HT versus placebo groups. Metabolites that demonstrated discordant effects of CEE and CEE+MPA treatments were further evaluated in a subset of 944 participants in the WHI-OS (Women’s Health Initiative Observational Study) for association with incident CHD risk and associations replicated among 647 participants randomized to the placebo arms of the WHI-HT trials. The metabolite-CHD associations identified in the WHI-OS were further tested for replicability in a metabolomics dataset nested within the PREDIMED trial (Prevención con Dieta Mediterránea).

METHODS

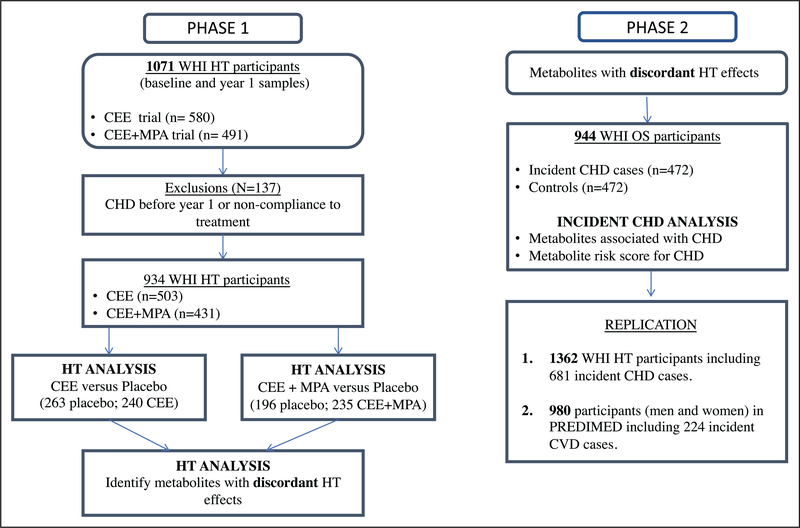

All participants in the WHI and PREDIMED cohorts provided written informed consent. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Mass General Brigham. The overview of the study design involving data from the WHI and PREDIMED cohorts is shown in Figure 1. The characteristics of the WHI participants are shown in Tables 1 and 2. The details of the materials and methods are described in the Data Supplement.

Figure 1. Study design evaluating metabolomic changes with hormone therapy (HT; phase 1) and with incident coronary heart disease (CHD) risk (phase 2).

CEE indicates conjugated equine estrogen; CVD, cardiovascular disease; MPA, medroxyprogesterone acetate; PREDIMED, Prevención con Dieta Mediterránea; WHI-HT, Women’s Health Initiative HT; and WHI-OS, Women’s Health Initiative Observational Study.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Participants in the WHI-OS and the WHI-HT Trials

| Characteristic | WHI-HT (CEE vs placebo) | WHI-HT (CEE+MPA vs placebo) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo (n=263) | CEE (n=240) | P value* | Placebo (n=196) | CEE+MPA (n=235) | P value* | |

| Age, y, mean (SD) | 66.09 (6.95) | 67.18 (6.47) | 0.07 | 66.41 (7.21) | 66.54 (7.36) | 0.86 |

| BMI, kg/m2, mean (SD) | 29.90 (5.95) | 30.14 (5.64) | 0.64 | 28.69 (5.88) | 28.40 (5.87) | 0.61 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mean (SD) | 134.73 (18.78) | 134.13 (17.59) | 0.71 | 132.49 (17.79) | 131.17 (19.09) | 0.46 |

| Race (%) | 0.05 | |||||

| Black | 20.15% | 10.83% | 0.0005 | 6.12% | 6.38% | |

| Hispanic/Latino | 4.18% | 0.83% | 0% | 2.98% | ||

| Other | 0.76% | 0% | 2.55% | 0.85% | ||

| White (not of Hispanic origin) | 74.14% | 88.33% | 91.33% | 89.79% | ||

| Current smoking, % | 15.21% | 13.33% | 0.31 | 13.27% | 14.89% | 0.75 |

| Prevalent diabetes, % | 19.01% | 15.83% | 0.41 | 12.76% | 12.77% | 1.00 |

| Prevalent hypertension, % | 49.81% | 51.25% | 0.93 | 43.37% | 40.43% | 0.46 |

| Incident deaths, % | ||||||

| All-cause | 50.19% | 49.58% | 0.94 | 50% | 47.23% | 0.63 |

| CVD | 30.80% | 26.67% | 0.34 | 22.96% | 24.26% | 0.82 |

| Incident CHD (%) | 48.67% | 50.83% | 0.68 | 49.49% | 50.64% | 0.85 |

BMI indicates body mass index; CEE, conjugated equine estrogen; CHD, coronary heart disease; CVD, cardiovascular disease; MPA, medroxyprogesterone acetate; WHI-HT, Women’s Health Initiative Hormone Therapy; and WHI-OS, WHI Observational Study.

P values comparing active treatment to placebo for continuous variables were from 2 sample t tests. P values for categorical variables were from Chi square tests with Monte Carlo simulated p values.

Table 2.

Baseline Characteristics of 944 Participants in the WHI-OS

| WHI-OS (N=944) | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| CHD cases n=472 | Controls n=472 | ||

| Age, y | 68 (7) | 67 (7) | 0.51 |

| Race | 1.00 | ||

| White | 348 (73%) | 348 (73%) | |

| Black | 69 (15%) | 69 (15%) | |

| Other | 55 (12%) | 55 (12%) | |

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 135 (19) | 130 (18) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes | 78 (17%) | 25 (5%) | <0.001 |

| BMI, m2/kg | 29 (6) | 27 (6) | 0.001 |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL | 231 (47) | 232 (47) | 0.51 |

| HDL cholesterol, mg/dL | 51 (16) | 57 (17) | <0.001 |

| Smoking status | 0.016 | ||

| Current | 48 (10%) | 28 (6%) | |

| Former | 209 (44%) | 243 (51%) | |

| Never | 215 (46%) | 201 (43%) | |

| Aspirin use | 116 (25%) | 98 (21%) | 0.16 |

| Statin use | 42 (9%) | 39 (8%) | 0.72 |

| Antihypertensive use | 144 (31%) | 91 (19%) | <0.001 |

| Antihyperglycemic use | 47 (10%) | 13 (3%) | <0.001 |

N(%) or mean (SD). BMI indicates body mass index; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; and WHI-OS, WHI Observational Study.

The data included in this study are subject to human subject protections and cannot be made freely available. Metabolite data from the WHI analyzed in this study are available from the dbGaP database under dbGaP accession no. phs001334. v1.p3.22. All other WHI data described in the article, codebook, and analytic code is available by request/research proposal at Women’s Health Initiative (www.whi.org).

RESULTS

Study Population

Metabolite values at baseline and 1 year were measured for 934 women, including 503 in the CEE trial (240 active, 263 placebo) and 431 in the CEE+MPA trial (235 active, 196 placebo). CHD case/control distributions were similar in both trials (by design), as were age, body mass index, systolic blood pressure distributions and the prevalence of current smokers (Table 1). The CEE trial had a higher proportion of African Americans and higher prevalence of diabetes than the CEE+MPA (Table 1).

HT Effects on the Metabolome

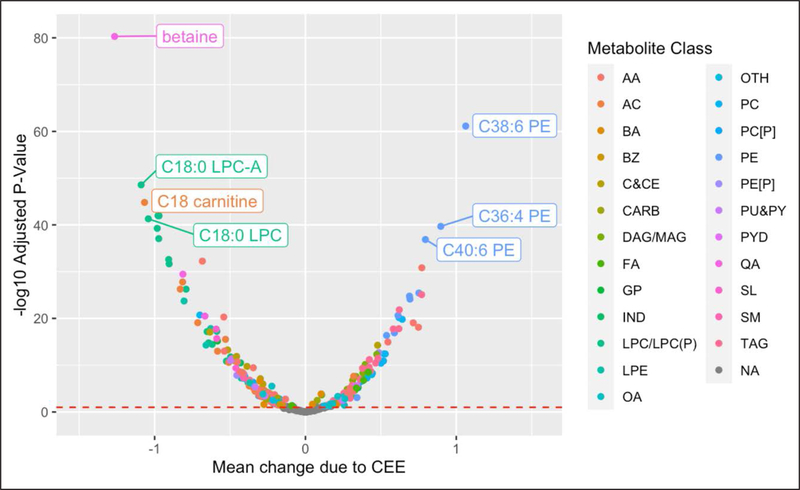

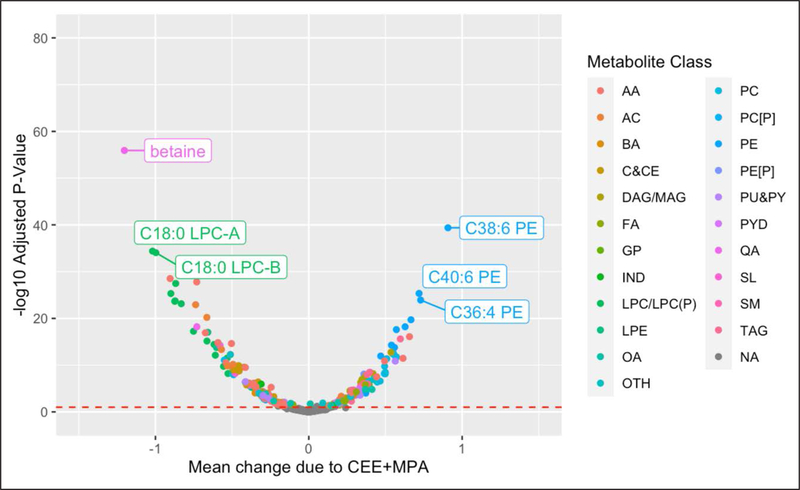

HT effects on the metabolome were profound. In the CEE trial, 298 of 481 (62%) metabolites were significantly altered (false discovery rate [FDR] adjusted P<0.05) by treatment after adjustment for metabolite levels at baseline, age, body mass index, CHD case/ control status, race, prevalent diabetes, and hypertension with 162 metabolites decreasing and 136 increasing with CEE treatment (Figure 2, Table I in the Data Supplement). In the CEE+MPA trial, 249 of 481 (52%) metabolites were significantly altered (FDR-adjusted P<0.05) by treatment, after adjustment for the same set of confounders, with 132 decreasing and 117 increasing with CEE+MPA treatment (Figure 3, Table II in the Data Supplement). There was no evidence of an interaction between the effects of each HT with baseline age (see Statistical Analysis section on page 7 of the Data Supplement).6

Figure 2. Mean change in relative abundance due to conjugated equine estrogen (CEE) when compared to placebo vs statistical significance.

Mean change due to HT (x axis) and statistical significance (y axis) estimated in linear models with metabolite levels at year 1 on the natural logarithm scale as the outcome (Y) and treatment indicator (CEE vs placebo) as the exposure while adjusting for metabolite levels at baseline, age, body mass index, coronary heart disease case-control status, race, prevalent diabetes and hypertension. AA indicates amino acid; AC, acylcarnitine; BA, bile acid; BZ, benzene and derivatives; C&CE, cholestyrl or cholesteryl ester; CARB, carbohydrates and conjugates; DAG or MAG, di(Mono)acyl glycerol; FA, fatty acid; GP, glycerophopholipid; IND, indole and indole derivatives; LPC or LPC(P), lysophosphatidylcholine or lysophosphatidylcholine plasmalogen; LPE, lysophosphatidyl ethanolamine; OA, other organic acid; OTH, other; PC [P], phosphatidylcholine plasmalogen; PC, phosphatidylcholine; PE, phosphatidyl ethanolamine; PE[P], phosphatidyl ethanolamine plasmalogen; PU&PY, purines and pyrimidines; PYD, pyridines and derivatives; QA, quaternary amine; SL, other sphingolipid; SM, sphingomyelin; and TAG, triacylglycerol.

Figure 3. Mean change in relative abundance due to conjugated equine estrogen+medroxyprogesterone acetate (CEE+MPA) when compared with placebo vs statistical significance.

Mean change due to HT (x axis) and statistical significance (y axis) estimated in linear models with metabolite levels at Year 1 on the natural logarithm scale as the outcome (Y) and treatment indicator (CEE vs placebo) as the exposure, while adjusting for metabolite levels at baseline, age, body mass index, coronary heart disease case-control status, race, prevalent diabetes, and hypertension. AA indicates amino acid; AC, acylcarnitine; BA, bile acid; BZ, benzene and derivatives; C&CE, cholestyrl or cholesteryl ester; CARB, carbohydrates and conjugates; DAG or MAG, di(mono)acyl glycerol; FA, fatty acid; GP, glycerophopholipid; IND, indole and indole derivatives; LPC or LPC(P), lysophosphatidylcholine or lysophosphatidylcholine plasmalogen; LPE, lysophosphatidyl ethanolamine; OA, other organic acid; OTH, other; PC [P], phosphatidylcholine plasmalogen; PC, phosphatidylcholine; PE, phosphatidyl ethanolamine; PE[P], phosphatidyl ethanolamine plasmalogen; PU&PY, purines and pyrimidines; PYD, pyridines and derivatives; QA, quaternary amine; SL, other sphingolipid; SM, sphingomyelin; and TAG, triacylglycerol.

HT resulted in a large magnitude of change in many metabolites, including 5 with >1 SD change with CEE and 2 for CEE+MPA (Figures 2 through 3). Metabolites with a decrease of >1 SD included betaine, C18:0 carnitine, C18:0 lysophosphatidylcholine-A, C18:0 lysophosphatidylcholine with CEE, and betaine and C18:0 lysophosphatidylcholine-A with CEE+MPA. The average increase in levels of C38:6 phosphatidylethanolamine with CEE was >1 SD.

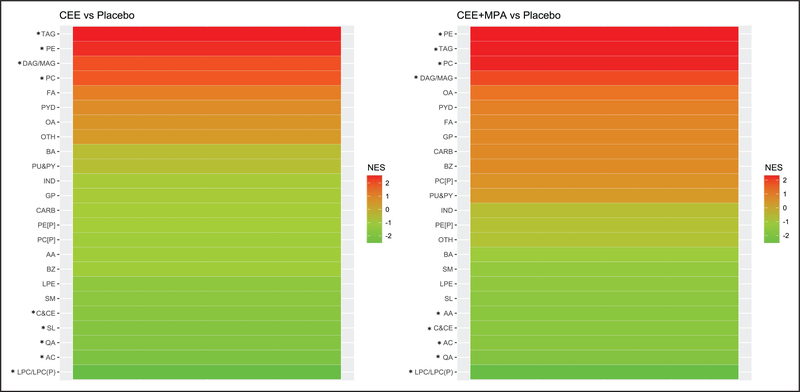

Metabolites that were altered with active HT were from many metabolite classes (Figures I through III in the Data Supplement). Evidence of concerted changes due to active HT relative to placebo within each of 24 metabolite classes was evaluated by Metabolite Set Enrichment Analysis, where the threshold for statistical significance was an FDR-adjusted P<0.05. As shown in Figure 4, CEE treatment resulted in positive enrichment of metabolites belonging to triacylglycerol, diacylglycerol/monoacylglycerol, phosphatidylcholine and phosphatidylethanolamine classes, and significant negative enrichment of metabolites belonging to lysophosphatidylcholine/ lysophosphatidylcholine plasmalogen, acylcarnitine, quaternary amine, other sphingolipid, and cholestyrl or cholesteryl ester classes. Similar changes were seen with CEE+MPA treatment, with additional negative enrichment of amino acids (AA), and lack of Metabolite Set Enrichment Analysis enrichment in other sphingolipids.

Figure 4. Metabolite classes enriched for metabolites showing concerted changes by active hormone therapy (HT) relative to placebo.

NES denotes the normalized enrichment score from Metabolite set enrichment analysis. A positive (negative) enrichment score corresponds to coordinated increases (decreases) in abundance of the metabolites in the active HT arm relative to placebo. AA indicates amino acid; AC, acylcarnitine; BA, bile acid; BZ, benzene and derivatives; C&CE, cholestyrl or cholesteryl ester; CARB, carbohydrates and conjugates; DAG or MAG, di(mono)acyl glycerol; FA, fatty acid; GP, glycerophopholipid; IND, indole and indole derivatives; LPC or LPC(P), lysophosphatidylcholine or lysophosphatidylcholine plasmalogen; LPE, lysophosphatidyl ethanolamine; OA, other organic acid; OTH, other; PC [P], phosphatidylcholine plasmalogen; PC, phosphatidylcholine; PE, phosphatidyl ethanolamine; PE[P], phosphatidyl ethanolamine plasmalogen; PU&PY, purines and pyrimidines; PYR, pyridines and derivatives; QA, quaternary amine; SL, other sphingolipid; SM, sphingomyelin; and TAG, triacylglycerol. *Metabolite classes with significant enrichment (false discovery rate adjusted P<0.05).

When class changes in abundance were examined, between 45% and 83% of the metabolites belonging to the lipid classes triacylglycerols, diacylglycerols/monoacylglycerols, phosphatidylcholines, and phosphatidylethanolamines increased in abundance with CEE relative to placebo; conversely, between 57% and 87% of all metabolites within the classes of lysophosphatidylcholines or lysophosphatidylcholine plasmalogens, acylcarnitines, quaternary amines, other sphingolipids, and cholestyrl or cholesteryl esters decreased in abundance with CEE relative to placebo (Figure I in the Data Supplement). Similar trends were seen with CEE+MPA treatment (Figure II in the Data Supplement) but with smaller proportions of significant changes within several metabolite classes.

Triacylglycerols demonstrated large changes with HT, where 50 of the 71 triacylglycerols measured (70%) were altered with CEE, and 40 by CEE+MPA (56%). With CEE, levels increased in 46 triacylglycerols, with a mean change of 0.31 SD units; levels decreased in 4 triacylglycerols with a mean change of −0.29 SD units. With CEE+MPA, 37 triacylglycerols increased with a mean change of 0.28 SD and 3 decreased with a mean change of −0.24 SD units (Figure III in the Data Supplement). Triacylglycerols that changed due to active HT included those with carbon chain lengths between 42 and 54 and with >5 double bonds; as well as triacylglycerols with longer carbon chain lengths between 56 and 60, but with high degree of unsaturation (5–12 double bonds).

Discordant Metabolome Effects Between HT Regimens

Although there was considerable overlap in the metabolite changes between CEE and CEE+MPA, there was also evidence of specific effects by HT type (Figures I and II in the Data Supplement). Among 71 triacylglycerols, 17% significantly changed with CEE but not with CEE+MPA; in contrast, only 2.8% of triacylglycerols significantly changed with CEE+MPA but not with CEE. Of 26 acylcarnitines, 27% significantly changed in abundance with CEE but not with CEE+MPA; in contrast, no changes among acylcarnitines were observed that were exclusive to CEE+MPA. Similarly, among 34 phosphatidylcholines, 24% significantly changed with CEE but not with CEE+MPA; however, none changed exclusively with CEE+MPA. In general, the number of metabolites significantly changing due to active HT was larger in the CEE trial than in the CEE+MPA trial. A resampling analysis confirmed that the observation of a fewer number of changes in the metabolome by CEE+MPA when compared to CEE was not entirely driven by sample size differences between trials (see Statistical Analysis on page 8 of the Data Supplement).

Tables 3 and 4 present the 22 metabolites with evidence of discordant effects by HT type—for each of these metabolites, a test of the equality of the CEE and CEE+MPA effects was rejected at a P value threshold of 0.05. Lysine was significantly altered by both CEE and CEE+MPA, but in opposite directions with an increase in levels with CEE and a decrease in levels due to CEE+MPA. Nineteen metabolites were changed by CEE but not CEE+MPA. Increased levels CEE relative to placebo were observed for 7 triacylglycerols (C54:9, C54:7, C56:9, C56:8, C56:7, C56:6, C58:11), 2 phosphatidylcholine plasmalogens (C38:7, C38:6), and glycocholate. CEE treatment resulted in decreased abundance for C36:1 phosphatidylcholine plasmalogen, C18:0 sphingomyelin, 2 carnitines (C7 and C18:1-OH), creatinine, fumarate/maleate, malate, sucrose, and hydroxyphenyacetate (Table 4). Only 2 metabolites were changed by CEE+MPA but not CEE; 7-methyl guanine increased with CEE+MPA, whereas levels of NMMA decreased with CEE+MPA (Table 4). The missing value distribution and coefficient of variation estimates for this subset of 22 metabolites is shown in Table 3 in the Data Supplement.

Table 3.

Direction of Change Among Metabolites With Discordant HT Effects, by Treatment Arm in the CEE and CEE+MPA WHI-HT Trials

| CEE+MPA vs placebo | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Decrease | No evidence for change | Increase | Total | |

| CEE vs placebo | ||||

| Decrease | 0 | 9* | 0 | 9 |

| No evidence for change | 1* | 0 | 1* | 2 |

| Increase | 1* | 10* | 0 | 11 |

| Total | 2 | 19 | 1 | 22 |

CEE indicates conjugated equine estrogen; HT, hormone therapy; MPA, medroxyprogesterone acetate; and WHI-HT, Women’s Health Initiative Hormone Therapy.

Corresponds to metabolites classified as having discordant HT effects.

Table 4.

Twenty-Two Metabolites With Differential Effects When Comparing CEE Alone to CEE+MPA

| Metabolite | CEE vs placebo | CEE+MPA vs placebo | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HT* | P value | FDR-adjusted P value | CEE effect† | P value | FDR-adjusted P value | CEE+MPA effect† | Difference in HT effect‡ | |

| C36:1 PC plasmalogen | CEE | 1.84×10−5 | 2.55×10−5 | −0.31 (−0.44 to −0.17) | 2.29×10−1 | 1.77×10−1 | −0.10 (−0.25 to 0.06) | −0.21 (−0.42 to 0.00) |

| C38:7 PC plasmalogen | CEE | 3.61×10−3 | 3.15×10−3 | 0.19 (0.06 to 0.31) | 7.62×10−1 | 4.46×10−1 | −0.02 (−0.16 to 0.12) | 0.21 (0.02 to 0.40) |

| C38:6 PC plasmalogen–A | CEE | 9.16×10−3 | 7.23×10−3 | 0.18 (0.05 to 0.32) | 4.49×10−1 | 3.00×10−1 | −0.06 (−0.21 to 0.09) | 0.24 (0.04 to 0.45) |

| C18:0 SM | CEE | 4.58×10−8 | 8.89×10−8 | −0.41 (−0.55 to −0.27) | 6.93×10−2 | 6.82×10−2 | −0.15 (−0.31 to 0.01) | −0.26 (−0.48 to −0.05) |

| C54:9 TAG | CEE | 9.90×10−4 | 9.60×10−4 | 0.23 (0.09 to 0.36) | 6.74×10−1 | 4.05×10−1 | −0.04 (−0.20 to 0.13) | 0.26 (0.05 to 0.47) |

| C54:7 TAG | CEE | 2.80×10−2 | 1.96×10−2 | 0.15 (0.02 to 0.29) | 3.39×10−1 | 2.37×10−1 | −0.07 (−0.22 to 0.08) | 0.23 (0.02 to 0.43) |

| C56:9 TAG | CEE | 1.70×10−4 | 1.94×10−4 | 0.27 (0.13 to 0.40) | 9.29×10−1 | 5.10×10−1 | −0.01 (−0.16 to 0.14) | 0.27 (0.07 to 0.48) |

| C56:8 TAG | CEE | 9.43×10−6 | 1.36×10−5 | 0.31 (0.18 to 0.45) | 3.12×10−1 | 2.24×10−1 | 0.08 (−0.07 to 0.23) | 0.24 (0.03 to 0.44) |

| C56:7 TAG | CEE | 4.51×10−4 | 4.75×10−4 | 0.24 (0.11 to 0.37) | 7.00×10−1 | 4.18×10−1 | 0.03 (−0.12 to 0.18) | 0.21 (0.01 to 0.41) |

| C56:6 TAG | CEE | 9.47×10−5 | 1.16×10−4 | 0.26 (0.13 to 0.39) | 4.37×10−1 | 2.94×10−1 | 0.05 (−0.08 to 0.19) | 0.21 (0.02 to 0.40) |

| C58:11 TAG | CEE | 1.88×10−6 | 3.03×10−6 | 0.31 (0.18 to 0.44) | 6.97×10−1 | 4.17×10−1 | 0.03 (−0.13 to 0.19) | 0.28 (0.08 to 0.48) |

| 7-methylguanine | CEE+MPA | 3.54×10−1 | 1.78×10−01 | −0.07 (−0.21 to 0.07) | 1.55×10−2 | 1.90×10−2 | 0.20 (0.04 to 0.36) | −0.27 (−0.48 to −0.05) |

| C7 carnitine | CEE | 5.77×10−6 | 8.59×10−6 | −0.35 (−0.50 to −0.20) | 1.32×10−1 | 1.14×10−1 | −0.12 (−0.27 to 0.03) | −0.23 (−0.44 to −0.02) |

| C18:1-OH carnitine | CEE | 7.22×10−3 | 5.98×10−3 | −0.22 (−0.38 to −0.06) | 5.15×10−1 | 3.37×10−1 | 0.05 (−0.11 to 0.22) | −0.27 (−0.50 to −0.05) |

| Creatinine | CEE | 1.90×10−3 | 1.73×10−3 | −0.19 (−0.31 to −0.07) | 9.40×10−1 | 5.13×10−1 | 0.00 (−0.11 to 0.12) | −0.20 (−0.36 to −0.03) |

| Glycocholate | CEE | 2.77×10−2 | 1.94×10−2 | 0.21 (0.02 to 0.39) | 1.30×10−1 | 1.13×10−1 | −0.14 (−0.32 to 0.04) | 0.35 (0.09 to 0.60) |

| Lysine | CEE | 4.29×10−5 | 5.59×10−5 | 0.31 (0.16 to 0.46) | 3.15×10−2 | 3.57×10−2 | −0.18 (−0.35 to −0.02) | 0.50 (0.27 to 0.72) |

| CEE+MPA | ||||||||

| NMMA | CEE+MPA | 1.28×10−1 | 7.43×10−2 | 0.11 (−0.03 to 0.26) | 3.81×10−2 | 4.20×10−2 | −0.18 (−0.35 to −0.01) | 0.29 (0.07 to 0.52) |

| Fumarate/maleate | CEE | 1.85×10−6 | 3.00×10−6 | −0.34 (−0.48 to −0.20) | 6.59×10−2 | 6.54×10−2 | 0.15 (−0.01 to 0.30) | −0.49 (−0.70 to −0.28) |

| Malate | CEE | 9.33×10−3 | 7.33×10−3 | −0.18 (−0.31 to −0.04) | 1.26×10−1 | 1.09×10−1 | 0.12 (−0.03 to 0.28) | −0.30 (−0.51 to −0.09) |

| Sucrose | CEE | 1.48×10−3 | 1.38×10−3 | −0.25 (−0.41 to −0.10) | 2.54×10−1 | 1.91×10−1 | 0.09 (−0.07,0.26) | −0.35 (−0.57 to −0.12) |

| Hydroxyphenylacetate | CEE | 2.49×10−2 | 1.76×10−2 | −0.17 (−0.31 to −0.02) | 2.93×10−1 | 2.13×10−1 | 0.08 (−0.07 to 0.23) | −0.25 (−0.46 to −0.04) |

CEE indicates conjugated equine estrogen; FDR, false discovery rate; HT, hormone therapy; MPA, medroxyprogesterone acetate; NMMA, N-methylmalonamic acid; PC, phosphatidylcholines; SM, sphingomyelin; and TAG, triacylglycerol.

HT denotes the treatment arm (relative to placebo) where a significant difference in metabolite levels was observed.

Treatment effect is the average difference due to active treatment (active treatment minus placebo) at year 1, in natural logarithm transformed, standardized units.

Difference in HT effect is calculated as the average change due to CEE minus the average change due to CEE+MPA.

Associations of Metabolites With Discordant Effects Between HT Regimens With Incident CHD Risk

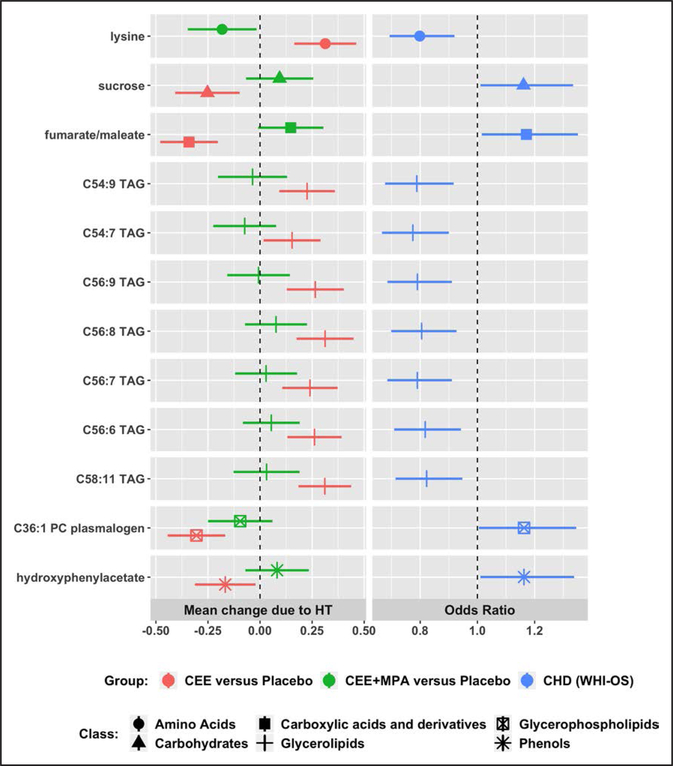

The 22 discordant metabolites were evaluated for association with incident CHD risk in an independent WHI-OS dataset with 472 incident CHD cases (median time to event of 5.8 years) and 472 frequency-matched controls (5). Table 2 shows the characteristics of the participants in the WHI-OS dataset. Twelve metabolites were associated with CHD risk (FDR-adjusted P<0.05), after adjusting for matching and traditional CHD risk factors including age, race, hysterectomy status, WHI enrollment time period, smoking, systolic blood pressure, diabetes, total and HDL (high-density lipoprotein) cholesterol, use of aspirin, antihyperglycemic drugs, and antihypertensive drugs (Table 5, Figure 5). All 12 metabolites were altered in the CHD protective direction by CEE treatment, including 7 triacylglycerols (C54:9, C 54:7, C 56:9, C56:8, C56:7, C 56:6, C 58:11), C36:1 phosphatidylcholine plasmalogen, lysine, fumarate/maleate, sucrose, and hydroxyphenylacetate. Lysine was significantly altered in the direction of increased CHD risk by CEE+MPA; the remaining 11 metabolites were not significantly changed by CEE+MPA (Table 5, Figure 5).

Table 5.

Metabolites With Discordant Treatment Effects in the WHI-HT and their associated Incident CHD Risk Profile in the WHI-OS

| Metabolite | Direction of change with CEE | Direction of change with CEE+MPA* | Incident CHD† association OR (95% CI); P value | HT effect with respect to CHD risk | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C36:1 PC plasmalogen | Decrease | Inconclusive | 1.16 (1.01–1.35); P=0.04 | CEE protective | CEE+MPA inconclusive |

| C54:9 TAG | Increase | Inconclusive | 0.79 (0.68–0.92); P=0.002 | CEE protective | CEE+MPA inconclusive |

| C54:7 TAG | Increase | Inconclusive | 0.77 (0.67–0.90); P=0.001 | CEE protective | CEE+MPA inconclusive |

| C56:9 TAG | Increase | Inconclusive | 0.79 (0.69–0.91); P=0.001 | CEE protective | CEE+MPA inconclusive |

| C56:8 TAG | Increase | Inconclusive | 0.81 (0.70–0.93); P=0.002 | CEE protective | CEE+MPA inconclusive |

| C56:7 TAG | Increase | Inconclusive | 0.79 (0.69–0.91); P=0.001 | CEE protective | CEE+MPA inconclusive |

| C56:6 TAG | Increase | Inconclusive | 0.82 (0.71–0.94); P=0.005 | CEE protective | CEE+MPA inconclusive |

| C58:11 TAG | Increase | Inconclusive | 0.82 (0.71–0.95); P=0.007 | CEE protective | CEE+MPA inconclusive |

| Lysine | Increase | Decrease | 0.80 (0.69–0.92); P=0.002 | CEE protective | CEE+MPA increased risk |

| Fumarate/maleate | Decrease | Inconclusive | 1.17 (1.02–1.35); P=0.03 | CEE protective | CEE+MPA inconclusive |

| Sucrose | Decrease | Inconclusive | 1.16 (1.01–1.33); P=0.03 | CEE protective | CEE+MPA inconclusive |

| Hydroxyphenylacetate | Decrease | Inconclusive | 1.16 (1.01–1.34); P=0.03 | CEE protective | CEE+MPA inconclusive |

CEE indicates conjugated equine estrogen; CHD, coronary heart disease; FDR, false discovery rate; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; HT, hormone therapy; MPA, medroxyprogesterone acetate; OR, odds ratio; PC, phosphatidylcholine; TAG, triacylglycerol; WHI-HT, Women’s Health Initiative HT; and WHI-OS, WHI Observational Study.

‘Inconclusive’ when a hypothesis test comparing metabolite abundance in the active HT arm to the placebo arm failed to reject the null hypothesis (FDR-adjusted P>0.05).

CHD model in the WHI-OS adjusted for age, hysterectomy, time period of enrollment, ethnicity, hypertension treatment, diabetes treatment, aspirin, statin use, systolic blood pressure, total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, diabetes, smoking. All 12 metabolites met a threshold of FDR-adjusted P<0.05 for association with CHD risk.

Figure 5. Twelve metabolites with discordant hormone therapy (HT) effects in the WHI-HT (Women’s Health Initiative HT) and associated with coronary heart disease (CHD) risk in the WHI-OS (WHI Observational Study).

MPA indicates medroxyprogesterone acetate; PC, phosphatidylcholine; and TAG, triacylglycerol.

From the 12 metabolites, a sparse metabolite fingerprint associated with CHD risk was identified in a Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator logistic regression model that included 2 triacylglycerols (C54:9, C56:9), lysine, fumarate/maleate, sucrose, and hydroxyphenylacetate (Table IV in the Data Supplement). The regression coefficients estimated in the Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator regression were used to calculate a metabolite score. The metabolite score was significantly associated with incident CHD risk (P<10−6) after adjustment for matching and CHD risk factors, with an odds ratio (OR) of 1.47 (95% CI, 1.27–1.70) per SD increase in the score. There was no evidence of an interaction of the metabolite score with age in predicting CHD risk (P=0.20).

As a validation, the metabolite score at baseline was evaluated for association with incident CHD risk in 1362 participants (681 incident CHD cases) in the active and placebo arms of the 2 WHI-HT trials. The OR for CHD per SD increase in the metabolite score was 1.23 (95% CI: 1.09–1.38, P<0.001), after adjustment for traditional CHD risk factors. When the analysis was restricted to 647 participants (322 incident CHD cases) in the placebo arms of the 2 WHI-HT trials, the OR for CHD per SD increase in the metabolite score was 1.19 (95% CI: 1.00–1.42, P=0.06), after adjustment for traditional CHD risk factors.

The metabolite-CHD associations identified in the WHI-OS were tested for replicability in the PREDIMED study. Eleven of the 12 metabolites (with the exception of hydroxyphenylacetate) were available for evaluation in the PREDIMED study. Each metabolite was evaluated for association with a combined CVD end point of incident myocardial infarction, stroke, and CHD death (224 cases, mean follow up of 4.8 years). Baseline characteristics of the PREDIMED study are shown in Table V in the Data Supplement. For the combined CVD outcome in men and women, 3 metabolites replicated in risk factor adjusted models (P<0.05), including fumarate/maleate (OR, 1.37 [95% CI, 1.15–1.62]), sucrose (OR, 1.33 [95% CI, 1.13–1.56]), and C58:11 triacylglycerol (OR, 0.84 [95% CI, 0.71–0.99]); C36:1 phosphatidylcholine was marginally significant (P<0.1), with an OR of 1.17 (95% CI, 0.98–1.40; Table 6). Additionally, C58:11 triacylglycerol showed evidence of an interaction effect with sex (P-interaction=0.03). Among females (n=530), C58:11 triacylglycerol was inversely associated with CVD risk (P=0.02, OR, 0.71 [95% CI, 0.54–0.94]; Table 6).

Table 6.

Association of 11 Metabolites With Incident Total CVD Among Men and Women in PREDIMED (n=980)

| Metabolite | All CVD* (N=980; n=224 cases) | CVD men only* (N=450; n=136 cases) | CVD women only* (N=530; n=88 cases) | Interaction by sex | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds ratio (95% CI) | P value | Odds ratio (95% CI) | P value | Odds ratio (95% CI) | P value | P value | |

| Fumarate/maleate | 1.37 (1.15–1.62) | 0.00035 | 1.39 (1.11–1.75) | 0.006 | 1.35 (1.03–1.77) | 0.03 | 0.86 |

| Sucrose | 1.33 (1.13–1.56) | 0.00076 | 1.37 (1.08–1.75) | 0.01 | 1.27 (1.01–1.61) | 0.04 | 0.93 |

| C58:11 TAG | 0.84 (0.71–0.99) | 0.035 | 0.86 (0.69–1.07) | 0.17 | 0.79 (0.61–1.02) | 0.07 | 0.43 |

| C36:1 PC | 1.17 (0.98–1.40) | 0.079 | 1.09 (0.86–1.38) | 0.48 | 1.27 (0.96–1.69) | 0.09 | 0.91 |

| C56:6 TAG | 0.89 (0.76–1.05) | 0.17 | 0.90 (0.72–1.13) | 0.38 | 0.86 (0.68–1.10) | 0.23 | 0.85 |

| C56:9 TAG | 0.87 (0.74–1.03) | 0.11 | 0.89 (0.72–1.10) | 0.29 | 0.84 (0.64–1.08) | 0.18 | 0.59 |

| C54:9 TAG | 0.90 (0.78–1.05) | 0.19 | 0.99 (0.82–1.19) | 0.89 | 0.71 (0.54–0.94) | 0.02 | 0.03 |

| C56:8 TAG | 0.92 (0.78–1.09) | 0.32 | 0.93 (0.75–1.15) | 0.50 | 0.89 (0.68–1.15) | 0.37 | 0.72 |

| C56:7 TAG | 0.95 (0.80–1.13) | 0.57 | 0.94 (0.75–1.17) | 0.59 | 0.94 (0.72–1.23) | 0.65 | 0.82 |

| Lysine | 1.05 (0.89–1.23) | 0.55 | 1.00 (0.81–1.23) | 0.96 | 1.13 (0.87–1.48) | 0.35 | 0.47 |

| C54:7 TAG | 0.95 (0.80–1.13) | 0.58 | 0.94 (0.76–1.17) | 0.59 | 0.93 (0.70–1.24) | 0.63 | 0.91 |

CVD indicates cardiovascular disease; PC, phosphatidylcholines; PREDIMED, Prevención con Dieta Mediterránea; and TAG, triacylglycerol.

Adjusted for baseline age, sex, intervention group, systolic blood pressure, total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, diabetes status, smoking, statin use.

Effects of HT on Triacylglycerols and Incident CHD Risk

Of the 50 triacylglycerols changing in abundance with CEE, 22 were altered in the CHD protective direction after adjustment for all confounders—all were observed to significantly increase with CEE and had inverse associations with CHD risk in the WHI-OS (FDR-adjusted P<0.05). None were altered in the direction of increased CHD risk with CEE (Table VI in the Data Supplement). Of the 40 triacylglycerols altered with CEE+MPA, 15 were in the CHD protective direction; none were altered in the direction of increased CHD risk with CEE+MPA (Table VII in the Data Supplement). Triacylglycerols with a higher degree of unsaturation were more likely to be changed in the CHD protective direction by CEE (OR, 1.95 corresponding to a unit increase in unsaturation [95% CI, 1.42–2.90], P=0.0002; Figure IV in the Data Supplement); no significant effect was observed for carbon chain length (P =0.12). Both degree of unsaturation and carbon chain length were not predictors of direction of change due to CEE+MPA (P>0.15).

DISCUSSION

Our study evaluated the impact of randomized HT treatment on metabolite levels and found substantial changes with both CEE and CEE+MPA compared with placebo. Overall, 62% of the metabolites significantly changed with randomized CEE and 52% significantly changed with CEE+MPA at 1 year in the active treatment groups compared with placebo (FDR-adjusted P<0.05), after adjustment for metabolite score at baseline, age, body mass index, CHD case/control status, race, prevalent diabetes, and hypertension. These changes were seen across a wide range of metabolite classes including triacylglycerols, AAs, phosphatidylcholines, and acylcarnitines.

Detailed data on the impact of HT on the metabolome have been limited. In a recent cross-sectional analysis in the Cancer Prevention II Nutrition Cohort, a large number of metabolites were observed to have differential abundance between HT users and nonusers, with 35% of metabolites significantly associated with estrogen-only use and 28% associated with estrogen plus progestin use.7 In particular, levels of numerous lipids, acylcarnitines and AAs differed between HT users and nonusers. However, this study was cross-sectional, not randomized, and had only a single metabolomic measure.

In the WHI-HT trials, treatment with CEE+MPA resulted in increased risk of CHD; however, these increased risks were not observed in the CEE arm.1,2 Twenty-two metabolites had significantly discordant effects between CEE and CEE+MPA, of which 12 were also associated with risk of incident CHD in an independent dataset of 944 participants nested within the WHI-OS cohort. Of these, 4 metabolites were associated with total CVD risk in the PREDIMED study in risk factor adjusted models, with an additional metabolite (C54:9 triacylglycerol) that replicated only within the subgroup of women.

A CHD metabolite score comprised of a sparse set of 6 discordant metabolites was associated with a 47% increased risk of CHD per SD in the WHI-OS and was replicated in a separate set of women in the WHI-HT placebo arms. Consistent with the WHI-HT findings of no observed CHD risk with CEE, all 6 metabolites were changed in the CHD protective direction by CEE and 1 metabolite (lysine) was changed in the direction of increased CHD risk by CEE+MPA.

HT is known to cause increases in triglycerides and 2 triacylglycerols (C56:9, C54:9) were included in our CHD metabolite risk score. In our study, 65% of triacylglycerol increased with CEE and 52% increased with CEE+MPA. When we compared the effect of the 2 HT regimens, we identified 7 triacylglycerols (C54:9, C54:7, C56:9, C56:8, C56:7, C56:6, C58:11) that were increased with CEE but not with CEE+MPA (Table 4). Higher levels of all 7 triacylglycerols were associated with reduced risk of CHD after adjustment for a full set of risk factors (FDR-adjusted P<0.05; Figure 5). Additionally, C54:9 triacylglycerol had a significant interaction effect with sex in the PREDIMED study, with a significant inverse association with CVD observed only in the subgroup of women (Table 6). In contrast, another nonoverlapping set of triacylglycerols and diacylglycerols with a lower double bond content (0–3), were associated with CHD in our prior work in the WHI.5

Changes in AAs were prominent with HT. The AA lysine was the strongest component of the CHD metabolite score, with higher levels associated with reduced CHD risk. Lysine levels were increased with CEE and decreased with CEE+MPA (FDR-adjusted P<0.05). Prior literature on the association of branched-chain AAs including leucine, lysine, and valine with CHD is complex. Several cohort studies have shown that higher levels of branched-chain AAs are associated with higher risk of CHD and other cardiometabolic disorders.8–11 In contrast, studies in human and animal models have demonstrated that higher dietary intake of branched-chain AAs is associated with cardiovascular benefits.12,13 Several previous studies have also found sex differences in the relationship between branched-chain AAs and insulin resistance with stronger evidence for the relationship in men.14,15 Thus, changes in AAs with CEE versus CEE+MPA may partially explain the observed differences in CHD risk.

Fumarate or fumaric acid is a dicarboxylic acid and a precursor to L-malate in the Krebs tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle. Recent literature points to fumarate as a carcinogenic metabolite.16 In our study, higher levels of fumarate were associated with increased CHD and fumarate levels were lowered by CEE in the CHD protective direction, with no corresponding change for CEE+MPA. High levels of fumarate were also associated with increased CVD risk in the PREDIMED study (Table 6).

The CHD metabolite score also included sucrose and hydroxyphenylacetate, where higher levels of each was associated with increased CHD risk. It is well established that added sugars such as sucrose in diet are associated with insulin resistance and increased CVD risk.17 Hydroxyphenylacetate is a phenol that was significantly associated with long-term cardiovascular mortality among 291 Black men in the Health ABC study (Health, Aging, and Body Composition; univariable hazard ratio of 1.39 [95% CI, 1.12–1.74] per SD increase). Moreover, in the Health ABC study, hydroxyphenylacetate was observed to be significantly increased among participants in the unhealthy category of the Healthy Aging Index relative to those in the optimal category.18

This study has several strengths including analysis of 2 randomized HT regimens in well-characterized populations and a broad metabolomics platform. However, this study is limited by the 2 specific HT regimens used, at specific doses. It is unclear how route of administration (ie, oral versus transdermal), formulation of estrogen or progestin, and dose might affect the observed associations. We cannot rule out that some changes in the effects of metabolites with type of HT may have been due to underlying differences in the populations of women with and without hysterectomy. Moreover, the participants in the WHI-HT trials were an average of 66 to 67 years of age at the time of randomization and relatively distant from the average age of menopause, but age at baseline did not modify the results.

In summary, HT treatment resulted in significant changes in metabolites, across a wide range of metabolite classes. Although a majority of metabolite changes were consistent between both treatment arms, there was evidence of fewer changes in metabolite profiles with CEE+MPA than CEE alone. In terms of associations with CHD risk, discordant effects by HT type on metabolites generally favored CEE alone. Differences in the effects of HT on metabolomic profiles may partially mediate the observed disease associations in the WHI-HT trials.

Future research in younger cohorts and with other formulations and doses of HT would further shed light on the HT-related effects on the metabolome and potential implications for CHD risk. Differential effects by HT type were also observed for invasive breast cancer, stroke and other chronic conditions. Future research could identify HT-related metabolomic changes that may partially explain the observed disparities in disease associations between HT regimens.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Dr Rexrode, R. Balasubramanian, and Dr Paynter conceived and designed the study. Drs Clish and Demler acquired and prepared the data for analysis. R. Balasubramanian, Drs Demler, Guasch-Ferré, R. Sheehan, Drs Paynter, Salas-Salvadó, Hu, and Rexrode analyzed and interpreted the results. R. Balasubramanian and Dr Rexrode drafted the article. Drs Manson, Martínez-Gonzalez, and Liu performed critical revisions of the article. All authors have discussed the results and reviewed the final article. Metabolite data analyzed in this study have been deposited in and are available from the dbGaP database under dbGaP accession no. phs001334. v1.p3.22. All other WHI (Women’s Health Initiative) data described in the article, codebook, and analytic code is available by request/research proposal at WHI (www.whi.org).

A list of WHI investigators is available online at https://www.whi.org/researchers/Documents%20%20Write%20a%20Paper/WHI%20Investigator%20Short%20List.pdf.

Sources of Funding

Metabolomic analysis in the WHI (Women’s Health Initiative) was funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health (NIH), US Department of Health and Human Services through contract HHSN268201300008C. This work was also partly supported by the by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute 5K01HL135342 awarded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the NIH to Dr Demler. This work was also partly supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute 1R01HL122241 awarded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the NIH to R. Balasubramanian. The WHI program is funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, NIH, US Department of Health and Human Services through contracts HHSN268201600018C, HHSN268201600001C, HHSN268201600002C, HHSN268201600003C, and HHSN268201600004C. The PREDIMED (Prevención con Dieta Mediterránea) metabolomics studies were funded by NIH grants R01 HL118264 and R01 DK102896. The PREDIMED trial was funded by the Spanish Ministry of Health (Instituto de Salud Carlos III, The PREDIMED Network grant RD 06/0045, 2006-13, coordinated by Dr Martínez-González; and a previous network grant RTIC-G03/140, 2003-05, coordinated R. Estruch). Dr Salas-Salvadó acknowledges the financial support by ICREA under the Catalan Institution for Research and Advanced Studies Academia program. Dr Guasch-Ferré is supported by the American Diabetes Association grant no. 1-18-PMF-029.

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- AA

aminoacid

- CEE

conjugated equine estrogens

- CHD

coronary heart disease

- CVD

cardiovascular disease

- FDR

false discovery rate

- Health ABC

Health, Aging, and Body Composition

- HT

hormone therapy

- MPA

medroxyprogesterone acetate

- OR

odds ratio

- PREDIMED

Prevención con Dieta Mediterránea

- WHI-HT

Women’s Health Initiative Hormone Therapy

- WHI-OS

Women’s Health Initiative Observational Study

Footnotes

The Data Supplement is available at https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/suppl/10.1161/CIRCGEN.119.002977.

Disclosures

None.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rossouw JE, Anderson GL, Prentice RL, LaCroix AZ, Kooperberg C, Stefanick ML, Jackson RD, Beresford SA, Howard BV, Johnson KC, et al. ; Writing Group for the Women’s Health Initiative Investigators. Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: principal results from the women’s health initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288:321–333. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.3.321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson GL, Limacher M, Assaf AR, Bassford T, Beresford SA, Black H, Bonds D, Brunner R, Brzyski R, Caan B, et al. ; Women’s Health Initiative Steering Committee. Effects of conjugated equine estrogen in postmenopausal women with hysterectomy: the women’s health initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;291:1701–1712. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.14.1701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Manson JE, Chlebowski RT, Stefanick ML, Aragaki AK, Rossouw JE, Prentice RL, Anderson G, Howard BV, Thomson CA, LaCroix AZ, et al. Menopausal hormone therapy and health outcomes during the intervention and extended poststopping phases of the women’s health initiative randomized trials. JAMA. 2013;310:1353–1368. doi: 10.1001/ jama.2013.278040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ala-Korpela M, Kangas AJ, Soininen P. Quantitative high-throughput metabolomics: a new era in epidemiology and genetics. Genome Med. 2012;4:36. doi: 10.1186/gm335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Paynter NP, Balasubramanian R, Giulianini F, Wang DD, Tinker LF, Gopal S, Deik AA, Bullock K, Pierce KA, Scott J, et al. metabolic predictors of incident coronary heart disease in women. Circulation. 2018;137:841–853. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.029468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rossouw JE, Prentice RL, Manson JE, Wu L, Barad D, Barnabei VM, Ko M, LaCroix AZ, Margolis KL, Stefanick ML. Postmenopausal hormone therapy and risk of cardiovascular disease by age and years since menopause. JAMA. 2007;297:1465–1477. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.13.1465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stevens VL, Wang Y, Carter BD, Gaudet MM, Gapstur SM. Serum metabolomic profiles associated with postmenopausal hormone use. Metabolomics. 2018;14:97. doi: 10.1007/s11306–018-1393–1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shah SH, Kraus WE, Newgard CB. Metabolomic profiling for the identification of novel biomarkers and mechanisms related to common cardiovascular diseases: form and function. Circulation. 2012;126:1110–1120. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.060368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheng J, Joyce A, Yates K, Aouizerat B, Sanyal AJ. Metabolomic profiling to identify predictors of response to vitamin E for non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). PLoS One. 2012;7:e44106. doi: 10.1371/ journal.pone.0044106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ruiz-Canela M, Toledo E, Clish CB, Hruby A, Liang L, Salas-Salvadó J, Razquin C, Corella D, Estruch R, Ros E, et al. Plasma branched-chain amino acids and incident cardiovascular disease in the PREDIMED trial. Clin Chem. 2016;62:582–592. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2015.251710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tobias DK, Lawler PR, Harada PH, Demler OV, Ridker PM, Manson JE, Cheng S, Mora S. Circulating branched-chain amino acids and incident cardiovascular disease in a prospective cohort of US women. Circ Genom Precis Med. 2018;11:e002157. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGEN.118.002157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jennings A, MacGregor A, Welch A, Chowienczyk P, Spector T, Cassidy A. Amino acid intakes are inversely associated with arterial stiffness and central blood pressure in women. J Nutr. 2015;145:2130–2138. doi: 10.3945/jn.115.214700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baum JI, O’Connor JC, Seyler JE, Anthony TG, Freund GG, Layman DK. Leucine reduces the duration of insulin-induced PI 3-kinase activity in rat skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2005;288:E86–E91. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00272.2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Würtz P, Mäkinen VP, Soininen P, Kangas AJ, Tukiainen T, Kettunen J, Savolainen MJ, Tammelin T, Viikari JS, Rönnemaa T, et al. Metabolic signatures of insulin resistance in 7,098 young adults. Diabetes. 2012;61:1372–1380. doi: 10.2337/db11–1355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhao X, Han Q, Liu Y, Sun C, Gang X, Wang G. The relationship between branched-chain amino acid related metabolomic signature and insulin resistance: a systematic review. J Diabetes Res. 2016;2016:2794591. doi: 10.1155/2016/2794591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sciacovelli M, Gonçalves E, Johnson TI, Zecchini VR, da Costa AS, Gaude E, Drubbel AV, Theobald SJ, Abbo SR, Tran MG, et al. Fumarate is an epigenetic modifier that elicits epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. Nature. 2016;537:544–547. doi: 10.1038/nature19353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Malik VS, Hu FB. Sugar-sweetened beverages and cardiometabolic health: an update of the evidence. Nutrients. 2019;11:1840. doi: 10.3390/ nu11081840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yeri A, Murphy RA, Marron MM, Clish C, Harris TB, Lewis GD, Newman AB, Murthy VL, Shah RV. Metabolite profiles of healthy aging index are associated with cardiovascular disease in African Americans: the health, aging, and body composition study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2019;74:68–72. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glx232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.