Abstract

Background

The burden of cardiovascular disease (CVD) is increasing in the aging population. However, little is known about CVD risk factors and outcomes for Asian American, Native Hawaiian, and Other Pacific Islander (NH/PI) older adults by disaggregated subgroups.

Methods

Data were from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services 2011–2015 Health Outcomes Survey, which started collecting expanded racial/ethnic data in 2011. Guided by Andersen and Newman’s theoretical framework, multivariable logistic regression analyses were conducted to examine the prevalence and determinants of CVD risk factors (obesity, diabetes, smoking status, hypertension) and CVD conditions (coronary artery disease [CAD], congestive heart failure [CHF], myocardial infarction [MI], other heart conditions, stroke) for 10 Asian American and NH/PI subgroups and White adults.

Results

Among the 639 862 respondents, including 26 853 Asian American and 4 926 NH/PI adults, 13% reported CAD, 7% reported CHF, 10% reported MI, 22% reported other heart conditions, and 7% reported stroke. CVD risk factors varied by Asian American and NH/PI subgroup. The prevalence of overweight, obesity, diabetes, and hypertension was higher among most Asian American and NH/PI subgroups than White adults. After adjustment, Native Hawaiians had significantly greater odds of reporting stroke than White adults.

Conclusions

More attention should focus on NH/PIs as a priority population based on the disproportionate burden of CVD risk factors compared with their White and Asian American counterparts. Future research should disaggregate racial/ethnic data to provide accurate depictions of CVD and investigate the development of CVD risk factors in Asian Americans and NH/PIs over the life course.

Keywords: Cardiovascular, Health disparities, Minority aging

The burden of cardiovascular disease (CVD) is increasing, and by 2035, projections estimate that more than 45% of the total U.S. population will have at least 1 CVD condition (1,2). CVD is the leading cause of mortality in the United States, including for adults aged 65 and older (3,4), and total costs associated with CVD are estimated to reach $1.1 trillion dollars in the next 15 years (2).

Prior research has demonstrated that Asian American adults have a greater proportionate mortality burden for hypertensive heart disease and cerebrovascular disease compared with White adults (5). Although White adults have experienced decreases in CVD mortality between 2003 and 2010, CVD mortality rates have actually increased for Asian Indian women and have not improved for other Asian American subgroups (5). Similarly, Iyer et al. reported variation in premature mortality (ie, death at younger age) due to CVD and longer years of life lost because of cerebrovascular disease in Asian American adults compared with White adults (6). For Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander (NH/PI) populations, research has reported higher prevalence of CVD morbidity and mortality than White and Asian American populations (7,8).

Asian Americans are the second fastest growing racial/ethnic population, with a projected increase of 201% between 2016 and 2060, and NH/PIs are projected to increase 146% during the same time period (9). Specific to adults aged 65 years and older, Asian Americans are the fastest growing population in the United States (10,11). Although much research combines Asian American and NH/PI, these groups represent 2 distinct racial categories (12) and collectively represent more than 40 communities and countries of origin that speak 100 different dialects and languages (13). Asian Americans typically arrived in the United States as immigrants or refugees (14). In contrast, Native Hawaiians are federally recognized as indigenous people (eg, similar to American Indians and Alaskan Natives), whereas Pacific Islanders have different political relationships with the United States (eg, citizens from the Federated States of Micronesia, Republic of the Marshall Islands, and Republic of Palau were admitted to the United States as nonimmigrants) (15). Asian American and NH/PI populations also have unique profiles of individual discrimination (eg, discriminatory experiences based on country of origin and political status) and institutional racism (eg, health policies for nonimmigrants) that impact health care utilization and access (16,17).

Despite the aforementioned differences, data for Asian American and NH/PI populations are typically reported as an aggregate or not reported. This reporting practice is still common 2 decades later, even after the Office of Management and Budget’s (OMB) standards were updated in 1997 to require more detailed federal reporting on racial/ethnic groups (12). For example, the American Heart Association (AHA) (18), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (4), and Healthy People 2020 (19) still report CVD data for Asian and NH/PI combined or as aggregate racial groups. Reporting the racial groups together results in misleading characterizations of health outcomes and masks any health differences and variation across Asian American and NH/PI subgroups. This subsequently affects the development of appropriate CVD guidelines, like the Pooled Cohort Equations for risk assessment of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) 20), and interventions for any identified health gaps.

The AHA issued a call to action for CVD research among Asian Americans in 2010, in response to the unequal distribution of CVD risk across Asian American subgroups (21) and a statement on ASCVD epidemiology and risk factors in South Asians (including individuals from Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, the Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka) in 2018 (22), whereas the AHA focus on NH/PI subgroups has been more minimal (18). Studies have reported higher rates of hypertension among Filipino adults than other Asian American subgroups, and higher total cholesterol among Japanese than Chinese adults (21,23). Research has demonstrated high prevalence of type 2 diabetes mellitus among South Asians, which is also worsened by high prevalence of metabolic syndrome (MetS) and insulin resistance (22). A recent study reported Filipinos had the highest current smoking rates than Chinese and Asian Indians, higher smoking rates among Asian men than women, and that more U.S.-born Filipinos were current smokers than foreign born (24). For NH/PIs, there is consensus in the literature that Native Hawaiians have among the highest rates of obesity, diabetes, smoking, hypertension, and high cholesterol, compared with Whites and other racial/ethnic groups (25). Differences across Asian American and NH/PI subgroups could be attributable to acculturation factors (eg, lifestyle changes) or political status (eg, nonimmigrants) that subsequently impact health behaviors and health care access (16,17). The impact of CVD risk factors also varies by Asian American and NH/PI subgroup. For example, body fat composition affects one’s risk of CVD and Asian Americans have higher percentages of body fat at lower mean and median body mass index (BMI) levels compared with Whites. Hence, traditional metrics like BMI may be misleading in the diagnoses of overweight and obesity among Asian Americans (26).

Few studies have examined CVD risk factors and CVD prevalence among Asian American and NH/PI older adults by ethnic group. This study describes the prevalence and determinants of CVD risk factors (obesity, diabetes, smoking, and hypertension) and self-reported CVD condition (coronary artery disease [CAD], congestive heart failure [CHF], myocardial infarction [MI], other heart conditions, and stroke) for 10 disaggregated Asian American and NH/PI subgroups and White adults enrolled in Medicare Advantage health plans. We also conducted subanalyses to examine the effect of language mainly spoken at home and English fluency on the association between race/ethnicity and CVD.

Method

Data came from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Health Outcomes Survey (HOS), a nationally representative survey of individuals enrolled in Medicare Advantage health plans. About one-third of Medicare beneficiaries are enrolled in Medicare Advantage plans (27). The HOS randomly samples individuals enrolled in Medicare Advantage organizations that have a minimum of 500 members (28). The HOS is a panel survey with baseline cohorts sampled annually, followed by a 2-year follow-up. Surveys written in English, Spanish, and Chinese are mailed to adults. Incomplete surveys and nonrespondents are contacted by phone up to 9 times in English or Spanish only. The HOS contains questions about health-related quality of life, chronic medical conditions, activities of daily living, instrumental activities of daily living, and health care effectiveness data and information set measures. The patient-reported HOS data are used for quality improvement activities and to monitor health plan performance (28).

We analyzed 5 baseline Medicare HOS Limited Data Sets (LDS) cohorts (2011–2015). The HOS began collecting expanded racial/ethnic data in 2011 and includes disaggregated data for 7 Asian American and 4 NH/PI categories. We included adults who were 65 years of age or older at baseline and self-identified as non-Hispanic Asian American, non-Hispanic NH/PI, or non-Hispanic White. We excluded respondents who were in hospice care, institutionalized, or had end-stage renal disease. We also excluded baseline surveys that were incomplete (ie, less than 79.5% of the survey was completed). The Oregon State University Institutional Review Board determined this study exempt from human subject research.

Dependent Variables

The dependent variables for this analysis included 5 dichotomous cardiovascular and stroke outcomes. Respondents were asked if a doctor ever diagnosed them with angina pectoris or CAD; CHF; MI or heart attack; other heart conditions, such as problems with heart valves or the rhythm of your heartbeat; and stroke.

Primary Independent Variable

The primary independent variable was self-reported race/ethnicity. We posit that membership in these groups signifies differences in predisposing characteristics, enabling resources, and need characteristics that influence CVD risk factors and disease patterns. We conceptualize race/ethnicity to represent culture, socioeconomic position, political status, and discriminatory experiences that may affect access and quality of health care services and, ultimately, health status (29).

Respondents were asked to self-identify if they were of Hispanic or Latino origin or descent and their race. Individuals who said no to being from Hispanic or Latino origin were categorized as being non-Hispanic. The 11 racial/ethnic categories were as follows: Asian Indian, Chinese, Filipino, Japanese, Korean, Vietnamese, Other Asian, Multiple-race Asian, Native Hawaiian, Other Pacific Islander, and White. Most racial/ethnic groups were non-Hispanic except for Multiple-race Asian, who included respondents who self-identified as an Asian group and another racial/ethnic group. Native Hawaiian included all respondents who self-identified as Native Hawaiian, even if they chose another racial/ethnic group. Other Pacific Islander included individuals who identified as Guamanian, Samoan, or Pacific Islander. White adults were included in the analyses as the referent group because prior literature has demonstrated White groups fare better across health indicators, including health care access and health care quality (30), and they represented the largest proportion of the MHOS sample.

Covariates Selection

Our analyses and selection of the model covariates were informed by Andersen and Newman’s model of health services utilization, which we hypothesized would explain differences in health care access and barriers to health care (31). The 3 main factors of this model include predisposing characteristics such as race/ethnicity and age, enabling resources such as income and health insurance, and need characteristics such as perceived and evaluated health status or contextual factors. Predisposing characteristics are antecedent to an outcome and representative of an individual’s social standing that enables or impedes their use of enabling resources. Need characteristics are individual’s perceived and actual need for health services, and contextual factors that influence an individual’s need, like the availability of health services. We posit that predisposing characteristics, enabling resources, and need characteristics impact health behaviors, and thus use of and barriers to health care services related to treatment and management of CVD risk factors and CVD conditions. We selected covariates a priori based on known associations with CVD risk factors and CVD conditions (32) and health disparities among racial/ethnic minority groups (33).

Predisposing characteristics included respondents’ sex, age (continuous variable), education attainment, and marital status. Enabling resources included household income and enrollment in Medicare/Medicaid. Individual need factors included BMI, diabetes, hypertension, and current smoking status. Asian-specific BMI thresholds (overweight = 23–27.5 kg/m2 and obese ≥ 27.5 kg/m2) were applied for Asian American subgroups, except for Multiple-race Asian respondents, based on recommendations from the World Health Organization (WHO) for more clinically relevant BMI thresholds for Asian populations (34). Respondents were asked if a doctor ever diagnosed them with diabetes or hypertension. Current smoking status was categorized as smoking every day, smoking some days, not smoking at all, and do not know. Contextual need factors included geographic region of the Medicare Advantage organization, whether a proxy had completed the survey, and survey administration year. Geographic region was based on the CMS regional offices that each represents Medicare Advantage organizations from several states. We included the geographic region to adjust for potential differences in health organizations by location. The survey year was included to account for biases in survey administration and different HOS survey versions.

Statistical Analysis

All analyses were conducted with RStudio, version 1.1.453 (35). We describe the prevalence of baseline predisposing, enabling, and need characteristics of the full sample by overall racial group and by disaggregated Asian American and NH/PI subgroups. We compared CVD risk factors and CVD conditions by disaggregated race/ethnicity and sex using 1-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) for continuous variables and chi-square test for categorical variables. All study variables compared disaggregated Asian American and NH/PI subgroups to White adults (referent group). We fit logistic regression models to examine the association between racial/ethnic group and CVD condition, stratified by sex. We present results stratified by sex based on prior research demonstrating sex differences in the prevalence of CVD and differences related to CVD prevention, diagnosis, and treatment (36). For each CVD condition, we fit an unadjusted model, model adjusting for age, and full model all of the covariates. We present odds radios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs), and a p value of less than .05 was considered a statistically significant relationship for the estimates by characteristics and in the multivariate logistic regression models.

We conducted subanalyses to explore the moderating effect of language mainly spoken at home and English proficiency on the association between race/ethnicity and CVD. Respondents were asked how well they spoke English in 2013 and 2014 and the language mainly spoken at home starting in 2015. We hypothesized that Asian American and NH/PI respondents who did not speak English at home or who had low levels of English language proficiency would be less likely to use health care services. Language mainly spoken at home and English proficiency were not included in the overall analyses.

Results

Predisposing, Enabling, and Contextual Need Factors of CVD

The final analytic sample included 639 862 Medicare Advantage enrollees from 416 plans (Table 1). The study variables were all significantly different across Asian American and NH/PI subgroups compared with White adults. All Asian American and NH/PI subgroups except for Japanese reported greater proportion of not graduating from high school, earning an income less than $10,000, and having more Medicare/Medicaid coverage than White adults. With the exception of Asian Indian and Other Pacific Islander adults, Asian American and Native Hawaiian respondents were located in the San Francisco region and all Asian and NH/PI subgroups were more likely to report having a proxy complete the survey than White adults.

Table 1.

Predisposing, Enabling, and Need Characteristics of Cardiovascular Disease, by Total Sample and Racial/Ethnic Group, Medicare Health Outcomes Survey, 2011–2015

| Characteristic | Total Sample | White | All Asian* | Asian Indian | Chinese | Filipino | Japanese | Korean | Vietnamese | Other Asian | Multiple-Race Asian | All NH/PI‡ | Native Hawaiian | Other PI | p Value§ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | 639 862 | 608 083 | 23 435 | 2 858 | 6 251 | 5 610 | 3 582 | 1 714 | 2 026 | 1 394 | 3 418 | 4 926 | 2 237 | 2 689 | |

| Predisposing characteristics | |||||||||||||||

| Female, % | 56.6 | 56.7 | 53.6 | 40.3 | 50.8 | 64.6 | 60.5 | 49.6 | 44.7 | 49.2 | 55.2 | 60.9 | 62.9 | 59.3 | <.001 |

| Mean age (SD), y | 74.3 (7.0) | 74.4 (7.0) | 74.2 (7.0) | 72.2 (5.8) | 74.5 (7.1) | 74.8 (6.7) | 76.8 (8.1) | 72.6 (5.9) | 72.1 (5.6) | 73.2 (6.4) | 73.7 (6.7) | 73.1 (6.3) | 73.0 (5.9) | 73.1 (6.6) | <.001 |

| Age group, y | |||||||||||||||

| 65–69 | 30.6 | 30.6 | 31.1 | 40.0 | 30.9 | 25.5 | 24.5 | 35.5 | 40.1 | 34.8 | 33.1 | 36.2 | 34.6 | 37.5 | |

| 70–74 | 27.0 | 27.0 | 27.7 | 31.5 | 25.3 | 28.8 | 21.0 | 33.5 | 31.3 | 30.6 | 28.0 | 29.5 | 31.6 | 27.9 | |

| 75–79 | 19.2 | 19.2 | 19.2 | 16.8 | 19.5 | 22.2 | 17.2 | 18.6 | 17.8 | 18.5 | 18.8 | 18.1 | 18.7 | 17.7 | |

| 80–84 | 13.2 | 13.3 | 12.7 | 7.9 | 14.5 | 14.1 | 17.5 | 7.5 | 8.1 | 9.5 | 12.3 | 10.1 | 10.4 | 9.9 | |

| >85 | 9.9 | 10.0 | 9.4 | 3.9 | 9.9 | 9.5 | 19.7 | 4.8 | 2.7 | 6.5 | 7.8 | 6.0 | 4.8 | 7.1 | <.001 |

| Education, % | |||||||||||||||

| Less than high school | 14.4 | 13.7 | 27.9 | 22.2 | 36.2 | 29.4 | 10.0 | 15.3 | 41.0 | 38.6 | 28.7 | 41.1 | 22.0 | 57.1 | |

| High school graduate/GED | 34.8 | 35.4 | 20.7 | 13.4 | 18.7 | 15.8 | 35.9 | 21.2 | 25.7 | 17.1 | 24.3 | 32.2 | 43.4 | 22.7 | |

| Some college | 26.5 | 27.0 | 16.9 | 11.8 | 14.0 | 16.1 | 26.9 | 15.7 | 20.4 | 14.6 | 20.8 | 17.7 | 24.1 | 12.2 | |

| College degree or more | 24.3 | 24.0 | 34.5 | 52.6 | 31.1 | 38.7 | 27.2 | 47.9 | 12.9 | 29.8 | 26.2 | 9.0 | 10.3 | 8.0 | <.001 |

| Married, % | 58.6 | 58.6 | 64.4 | 76.5 | 69.0 | 57.7 | 51.2 | 73.6 | 71.0 | 59.6 | 54.9 | 41.2 | 40.4 | 41.8 | <.001 |

| Enabling resources | |||||||||||||||

| Income, % | |||||||||||||||

| Less than $10 000 | 8.1 | 7.4 | 19.8 | 19.2 | 23.2 | 21.6 | 6.7 | 17.4 | 25.0 | 26.2 | 22.8 | 27.1 | 18.7 | 34.1 | |

| $10 000–19 999 | 17.7 | 17.6 | 20.6 | 16.5 | 25.0 | 18.1 | 12.7 | 22.5 | 33.4 | 18.3 | 18.5 | 19.8 | 18.8 | 20.6 | |

| $20 000–29 999 | 17.4 | 17.7 | 10.9 | 10.0 | 10.3 | 10.0 | 12.7 | 13.4 | 12.0 | 9.5 | 12.3 | 11.0 | 12.1 | 10.2 | |

| $30 000–49 999 | 23.0 | 23.5 | 15.3 | 15.2 | 12.3 | 14.9 | 21.6 | 19.5 | 11.0 | 15.1 | 14.7 | 11.9 | 14.7 | 9.5 | |

| $50 000 or more | 23.5 | 23.9 | 19.0 | 26.2 | 16.7 | 14.6 | 32.1 | 20.6 | 6.9 | 15.1 | 14.4 | 10.9 | 17.5 | 5.5 | |

| Do not know | 10.2 | 9.9 | 14.5 | 13.0 | 12.5 | 20.8 | 14.2 | 6.6 | 11.7 | 15.7 | 17.3 | 19.3 | 18.1 | 20.3 | |

| Medicare/Medicaid, % | 12.3 | 10.8 | 39.6 | 38.7 | 42.2 | 46.8 | 8.5 | 29.5 | 66.1 | 54.4 | 39.8 | 45.7 | 32.6 | 56.6 | <.001 |

| Contextual need factors | |||||||||||||||

| CMS office, %‖ | |||||||||||||||

| Atlanta | 14.1 | 14.4 | 6.0 | 15.0 | 4.1 | 3.0 | 1.8 | 13.1 | 6.9 | 8.9 | 11.2 | 9.2 | 1.9 | 15.4 | |

| Boston | 6.4 | 6.6 | 3.0 | 4.5 | 4.2 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 2.6 | 7.1 | 3.6 | 3.4 | 4.2 | 0.5† | 7.3 | |

| Chicago | 20.8 | 21.6 | 7.2 | 14.1 | 4.2 | 5.6 | 2.3 | 6.2 | 10.5 | 21.7 | 7.6 | 3.6 | 1.5 | 5.3 | |

| Dallas | 9.4 | 9.6 | 5.4 | 13.1 | 3.6 | 3.0 | 1.5 | 3.0 | 14.6 | 7.5 | 8.0 | 4.2 | 2.0 | 6.0 | |

| Denver | 4.7 | 4.8 | 1.2 | 0.8† | 1.0 | 0.3† | 2.7 | 2.0 | 1.3 | 2.4 | 2.2 | 2.1 | 1.6 | 2.5 | |

| Kansas City | 6.0 | 6.2 | 1.7 | 1.6 | 1.1 | 1.8 | 2.3 | 1.3† | 2.2 | 1.4† | 2.3 | 1.9 | 3.0 | 1.1 | |

| New York | 7.9 | 7.7 | 9.9 | 26.1 | 11.9 | 6.8 | 1.3 | 12.0 | 1.3 | 13.1 | 11.5 | 17.2 | 1.7 | 30.0 | |

| Philadelphia | 8.7 | 8.9 | 4.3 | 8.5 | 2.8 | 2.1 | 1.5 | 12.3 | 6.9 | 4.6 | 4.2 | 2.9 | 0.8 | 4.7 | |

| San Francisco | 12.6 | 10.4 | 55.7 | 13.4 | 62.7 | 72.0 | 79.0 | 39.0 | 38.6 | 30.3 | 44.7 | 51.5 | 84.8 | 23.8 | |

| Seattle | 9.7 | 9.8 | 5.6 | 2.8 | 4.6 | 4.5 | 7.0 | 8.6 | 10.6 | 6.6 | 4.8 | 3.1 | 2.1 | 4.0 | <.001 |

| Survey completed by, % | |||||||||||||||

| Person addressed | 91.6 | 92.5 | 73.3 | 79.3 | 69.2 | 75.9 | 85.0 | 69.2 | 62.0 | 59.0 | 81.1 | 75.1 | 90.0 | 62.2 | |

| Family member | 7.6 | 6.9 | 23.5 | 19.7 | 25.8 | 22.2 | 12.9 | 26.7 | 34.0 | 34.9 | 17.0 | 19.9 | 8.3 | 30.0 | |

| Friend or caregiver | 0.8 | 0.6 | 3.2 | 1.0 | 5.0 | 1.9 | 2.1 | 4.1 | 4.1 | 6.2 | 1.9 | 5.0 | 1.7 | 7.9 | <.001 |

Notes: CMS = Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services; GED = General Equivalency Diploma; NH/PI = Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander; PI = Pacific Islander. “—” are displayed for cells with less than 11 respondents following the CMS cell size suppression policy and “†” for cells with less than 25 respondents.

*All Asian category includes Asian Indian, Chinese, Filipino, Japanese, Korean, Vietnamese, and Other Asian.

‡All NH/PI category includes Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islander.

§We performed ANOVA and chi-square tests to compare disaggregated Asian American and NH/PI subgroups with White adults (referent group).

‖The CMS regional offices are the state and local representation for Medicare Advantage plans and represent several states. The Atlanta region serves Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Tennessee. The Boston region serves Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. The Chicago region serves Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Minnesota, Ohio, and Wisconsin. The Dallas region serves Arkansas, Louisiana, New Mexico, Oklahoma, and Texas. The Denver region serves Colorado, Montana, North Dakota, South Dakota, Utah, and Wyoming. The Kansas City region serves Iowa, Kansas, Missouri, and Nebraska. The New York region serves New Jersey, New York, Puerto Rico, and the Virgin Islands. The Philadelphia region serves Delaware, District of Columbia, Maryland, Pennsylvania, Virginia, and West Virginia. The San Francisco region serves Arizona, California, Hawaii, Nevada, and Pacific Territories. The Seattle region serves Alaska, Idaho, Oregon, and Washington.

Individual Need Characteristics

Among the total sample, 46% were overweight, 26% had diabetes, and 67% had hypertension (Supplementary Table 1). Most Asian American adults reported greater prevalence of being overweight (except for Vietnamese and Multiple-race Asian), diabetes (except for Multiple-race Asian), and hypertension (except for Asian Indian, Chinese, Japanese, Korean, Other Asian, and Multiple-race Asian) but lower prevalence of smoking compared with White adults (Supplementary Table 1). Compared with Asian American men, Asian American women reported lower proportions of being overweight, diabetes, and smoking but higher proportions of hypertension (Table 2). Among Asian American men, Filipino men reported the highest prevalence of being overweight and obese and hypertension; Asian Indian men had greatest prevalence of diabetes; and Multiple-race Asian men had the highest prevalence of smoking. Among Asian American women, Asian Indian women reported the highest prevalence of being overweight and obese and diabetes; Filipino women had greatest prevalence of hypertension; and Multiple-race Asian women had the highest prevalence of smoking (Table 2).

Table 2.

Prevalence of Cardiovascular Disease Risk Factors, by Total Sample, Sex, and Racial/Ethnic Group, Medicare Health Outcomes Survey, 2011–2015

| Individual Need Factors | Total Sample | White | All Asian* | Asian Indian | Chinese | Filipino | Japanese | Korean | Vietnamese | Other Asian | Multiple-Race Asian | All NH/PI‡ | Native Hawaiian | Other PI | p Value§ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men, no. | 278 082 | 263 744 | 10 878 | 1 706 | 3 077 | 1 987 | 1 416 | 864 | 1 120 | 708 | 1 534 | 1 926 | 831 | 1 095 | |

| BMI, mean (SD), kg/m2 | 27.9 (5.0) | 28.1 (5.0) | 24.6 (3.8) | 25.1 (5.0) | 23.9 (3.4) | 25.3 (4.0) | 25.4 (4.4) | 24.2 (3.3) | 23.4 (3.4) | 25.5 (4.0) | 26.2 (5.0) | 28.5 (5.9) | 29.1 (6.3) | 28.1 (5.6) | <.001 |

| BMI group, %* | |||||||||||||||

| Normal | 25.0 | 24.7 | 29.7 | 25.5 | 35.5 | 22.6 | 25.3 | 31.8 | 40.2 | 25.1 | 39.6 | 25.1 | 22.9 | 26.8 | |

| Underweight | 1.0 | 0.9 | 3.3 | 2.5 | 4.3 | 2.8 | 2.2 | 3.5 | 5.1 | 1.9 | 2.9 | 1.5 | 1.6 | 1.5 | |

| Overweight | 46.2 | 46.1 | 49.7 | 51.1 | 48.0 | 52.8 | 49.2 | 52.8 | 46.0 | 47.5 | 41.9 | 40.4 | 37.7 | 42.5 | |

| Obese | 27.8 | 28.3 | 17.3 | 20.9 | 12.2 | 21.9 | 23.2 | 11.9 | 8.7 | 25.5 | 15.6 | 33.0 | 37.8 | 29.3 | <.001 |

| Diabetes, % | 26.0 | 25.5 | 34.1 | 44.2 | 28.2 | 40.1 | 29.9 | 28.2 | 31.3 | 39.3 | 37.4 | 41.5 | 37.0 | 44.7 | <.001 |

| Hypertension, % | 63.6 | 63.5 | 64.4 | 62.3 | 61.8 | 72.6 | 63.9 | 52.1 | 70.3 | 63.8 | 66.0 | 71.2 | 70.7 | 71.6 | <.001 |

| Smoking, % | |||||||||||||||

| Not at all | 89.4 | 89.4 | 91.1 | 93.8 | 90.8 | 91.0 | 91.0 | 90.6 | 88.9 | 90.9 | 88.1 | 85.6 | 87.5 | 84.2 | |

| Every day | 7.0 | 7.1 | 5.1 | 3.4 | 5.8 | 5.3 | 6.1 | 4.4 | 4.8 | 5.1 | 5.8 | 7.1 | 7.2 | 7.1 | |

| Some days | 3.1 | 3.1 | 2.6 | 1.9 | 2.3 | 2.9 | 2.6 | 3.3 | 3.9 | 2.4† | 4.9 | 5.1 | 4.1 | 5.9 | |

| Do not know | 0.4 | 0.4 | 1.1 | 0.9† | 1.1 | 0.9† | — | 1.7† | 2.4 | — | 1.1† | 2.1 | — | 2.8 | <.001 |

| Women, no. | 371 408 | 353 332 | 12 913 | 1 194 | 3 248 | 3 747 | 2 219 | 870 | 928 | 707 | 1 990 | 3 173 | 1 316 | 1 857 | |

| BMI, mean (SD), kg/m2 | 27.6 (6.2) | 27.7 (6.2) | 24.0 (4.4) | 26.0 (4.8) | 23.3 (3.9) | 24.7 (4.4) | 23.4 (4.4) | 23.4 (3.8) | 23.1 (3.8) | 25.2 (5.0) | 26.4 (5.7) | 28.9 (6.8) | 29.0 (7.1) | 28.9 (6.5) | <.001 |

| BMI group, %‖ | |||||||||||||||

| Normal | 35.0 | 34.9 | 37.6 | 23.8 | 44.0 | 31.7 | 42.1 | 42.6 | 45.3 | 32.7 | 43.2 | 27.6 | 28.3 | 26.9 | |

| Underweight | 2.6 | 2.4 | 6.3 | 3.1 | 7.8 | 4.5 | 9.7 | 6.4 | 7.8 | 2.3 | 3.0 | 1.8 | 2.1 | 1.5 | |

| Overweight | 33.4 | 33.2 | 39.0 | 40.7 | 36.4 | 44.2 | 33.3 | 39.7 | 35.9 | 41.0 | 32.3 | 33.5 | 33.1 | 33.9 | |

| Obese | 29.1 | 29.5 | 17.1 | 32.4 | 11.8 | 19.6 | 14.9 | 11.3 | 10.9 | 24.0 | 21.6 | 37.1 | 36.5 | 37.7 | <.001 |

| Diabetes, % | 20.9 | 20.4 | 29.8 | 37.7 | 26.2 | 34.4 | 24.1 | 23.1 | 29.6 | 35.3 | 35.6 | 38.8 | 35.9 | 41.3 | <.001 |

| Hypertension, % | 64.3 | 64.1 | 67.1 | 65.9 | 63.4 | 78.1 | 60.9 | 54.4 | 67.2 | 63.9 | 70.6 | 75.1 | 74.8 | 75.3 | <.001 |

| Smoking, % | |||||||||||||||

| No at all | 91.1 | 90.9 | 96.2 | 98.0 | 97.9 | 95.5 | 94.1 | 95.0 | 96.3 | 96.6 | 92.0 | 88.3 | 84.8 | 91.4 | |

| Every day | 5.9 | 6.1 | 1.7 | — | 0.6† | 1.9 | 4.0 | 2.6† | — | — | 4.1 | 6.4 | 9.5 | 3.6 | |

| Some days | 2.6 | 2.6 | 1.0 | — | 0.4† | 1.6 | 1.3 | — | — | — | 2.6 | 3.8 | 5.1 | 2.5 | |

| Do not know | 0.4 | 0.3 | 1.1 | 1.3† | 1.0 | 1.0 | — | — | 2.5† | 1.8† | 1.3† | 1.5 | — | 2.5 | <.001 |

Notes: BMI = body mass index; CVD = cardiovascular disease; NH/PI = Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander; PI = Pacific Islander. “—” are displayed for cells with less than 11 respondents following the CMS cell size suppression policy and “†” for cells with less than 25 respondents.

*All Asian category includes Asian Indian, Chinese, Filipino, Japanese, Korean, Vietnamese, and Other Asian.

‡All NH/PI category includes Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islander.

§We performed ANOVA and chi-square tests to compare disaggregated Asian American and NH/PI subgroups to White adults (referent group).

‖Asian-specific BMI thresholds (normal = 18.5 to <23 kg/m2, overweight = 23 to 27.5 kg/m2, obese ≥ 27.5 kg/m2) were applied to Asian Indian, Chinese, Filipino, Japanese, Korean, Vietnamese, and Other Asian.

NH/PI adults reported greater prevalence of obesity, diabetes (except compared with Asian Indian), hypertension (except compared to Filipino), and smoking everyday compared with White and Asian American adults (Supplementary Table 1). Among NH/PI adults, Other Pacific Islander men and women reported higher proportions of being overweight and obese, diabetes, and hypertension, whereas Native Hawaiian men and women reported higher proportions of smoking. Compared with White and Asian American men, NH/PI men reported greater prevalence of obesity, diabetes (except compared with Asian Indian), hypertension (except compared with Filipino), and smoking (except compared with Japanese; Table 2). NH/PI women reported greater prevalence of obesity and hypertension but lower prevalence of diabetes and smoking than NH/PI men.

Prevalence of CVD Conditions

Among the total sample, 13% reported CAD; 7% reported CHF; 10% reported MI; 22% reported other heart conditions; and 7% reported stroke (Supplementary Table 2). Compared with White men, Asian American men reported lower proportions of CAD (except for Asian Indian men), CHF (except for Multiple-race men), MI, other heart conditions, and stroke (except for Filipino and Multiple-race Asian men; Table 3). Among Asian American men, Asian Indian men reported CAD and MI most often, whereas Multiple-race Asian men reported CHF, other heart conditions, and stroke most often. Compared with White women, Asian American women reported lower prevalence of CVD conditions and stroke except for Vietnamese and Multiple-race Asian women. Vietnamese ”Vietnamese women” reported stroke more often than did White women, whereas Multiple-race Asian women reported CAD, CHF, and stroke more often. Among Asian American women, Multiple-race Asian women reported the greatest prevalence of all CVD conditions and stroke.

Table 3.

Prevalence of Cardiovascular Disease Conditions and Stroke, by Total Sample, Sex, and Racial/Ethnic Group, Medicare Health Outcomes Survey, 2011–2015

| CVD Condition or Stroke | Total Sample | White | All Asian* | Asian Indian | Chinese | Filipino | Japanese | Korean | Vietnamese | Other Asian | Multiple- Race Asian | All NH/PI† | Native Hawaiian | Other PI | p Value‡ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men, no. | 278 082 | 269 686 | 11 175 | 1 750 | 3 143 | 2 057 | 1 452 | 894 | 1 150 | 729 | 1 612 | 2 033 | 763 | 1 270 | |

| CAD, % | 18.4 | 18.7 | 12.1 | 19.3 | 10.9 | 11.6 | 11.0 | 8.6 | 8.5 | 12.8 | 16.3 | 16.4 | 17.2 | 15.7 | <.001 |

| CHF, % | 8.4 | 8.5 | 5.3 | 6.2 | 4.3 | 6.4 | 4.8 | 3.9 | 5.8 | 6.9 | 10.6 | 13.6 | 14.1 | 13.1 | <.001 |

| MI, % | 13.5 | 13.8 | 7.2 | 11.7 | 5.0 | 7.6 | 8.3 | 4.4 | 5.7 | 9.0 | 10.8 | 13.8 | 15.3 | 12.7 | <.001 |

| Other heart, % | 23.3 | 23.7 | 14.8 | 15.5 | 15.1 | 15.3 | 15.9 | 10.3 | 13.7 | 15.0 | 18.9 | 22.6 | 24.8 | 20.9 | <.001 |

| Stroke, % | 7.7 | 7.7 | 7.1 | 7.6 | 6.0 | 9.7 | 6.7 | 4.2 | 7.5 | 7.5 | 10.0 | 12.5 | 12.4 | 12.7 | <.001 |

| Women, no. | 371 408 | 353 332 | 12 913 | 1 194 | 3 248 | 3 747 | 2 219 | 870 | 928 | 707 | 1 990 | 3 173 | 1 316 | 1 857 | |

| CAD, % | 9.5 | 9.7 | 6.6 | 8.6 | 7.4 | 7.2 | 4.3 | 3.7 | 7.2 | 6.8 | 9.9 | 11.4 | 10.2 | 12.4 | <.001 |

| CHF, % | 6.2 | 6.4 | 4.0 | 4.7 | 2.7 | 4.9 | 2.8 | 3.0 | 6.1 | 6.0 | 7.2 | 9.7 | 9.2 | 10.2 | <.001 |

| MI, % | 6.2 | 6.3 | 3.4 | 5.1 | 3.2 | 3.4 | 3.4 | 2.1 | 3.6 | 3.7 | 6.0 | 7.5 | 8.5 | 6.6 | <.001 |

| Other heart, % | 20.1 | 20.3 | 14.3 | 12.6 | 15.3 | 15.5 | 14.3 | 9.5 | 13.5 | 13.7 | 18.3 | 18.9 | 18.9 | 19.0 | <.001 |

| Stroke, % | 6.9 | 6.9 | 5.7 | 5.2 | 4.8 | 5.5 | 6.8 | 5.2 | 7.8 | 5.6 | 8.6 | 9.4 | 11.9 | 7.2 | <.001 |

Notes: CAD = coronary artery disease; CHF = congestive heart failure; CVD = cardiovascular disease; MI = myocardial infarction; NH/PI = Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander; PI = Pacific Islander.

*All Asian category includes Asian Indian, Chinese, Filipino, Japanese, Korean, Vietnamese, and Other Asian.

†All NH/PI category includes Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islander.

‡We performed chi-square tests to compare disaggregated Asian American and NH/PI groups.

Native Hawaiian men reported the higher proportions CHF, MI, other heart conditions and stroke compared with White men, whereas Other Pacific Islander men reported greater proportions of CHF and stroke. NH/PI women reported higher proportions of CAD, CHF, MI, other heart conditions, and stroke than did White women.

Association Between Race/Ethnicity and CVD Conditions

In the adjusted analyses, Asian American and NH/PIs in aggregate had lower odds of all conditions compared with White adults (Supplementary Table 3). When data were further disaggregated by subgroups, Native Hawaiian adults had significantly greater odds of reporting stroke than White adults (Supplementary Table 4), which would have otherwise been masked if subgroup data were not available or investigated.

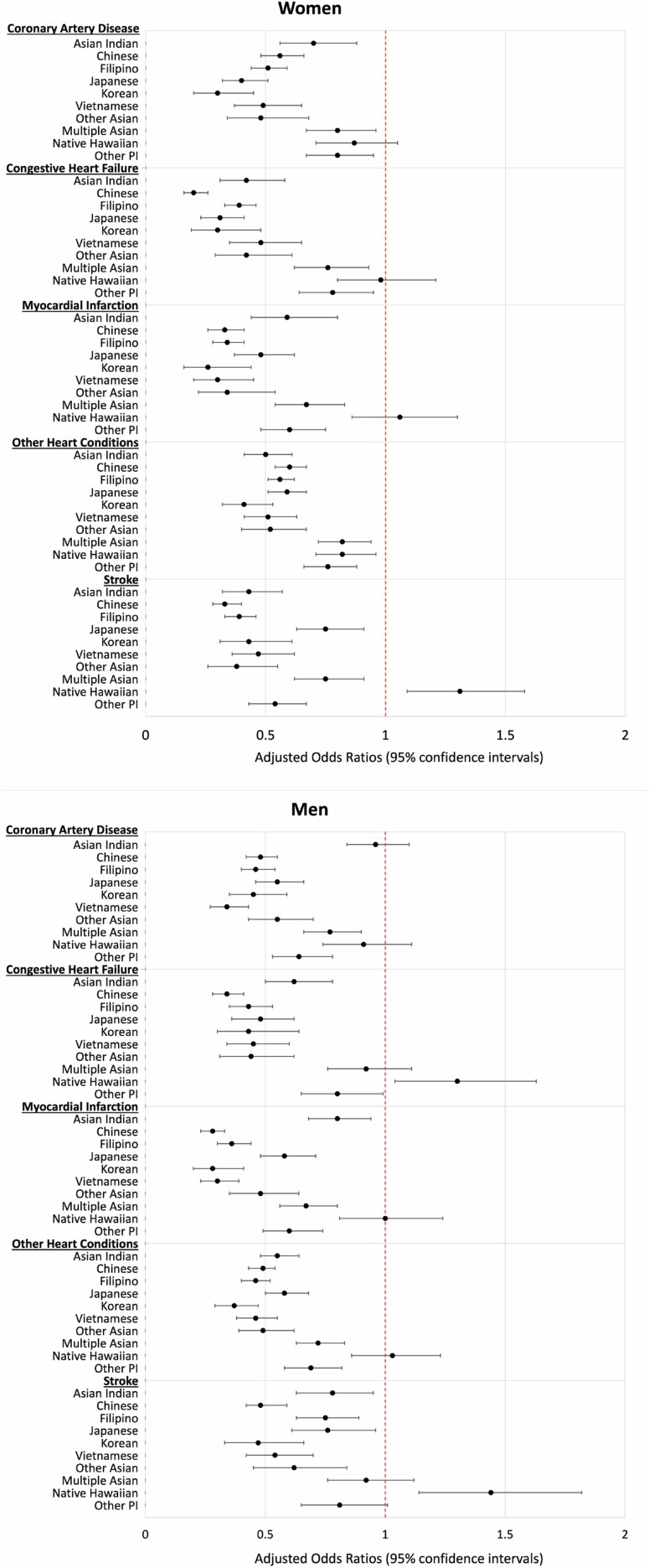

When results were stratified by sex, Asian American subgroups still had lower odds of all CVD conditions and stroke compared with their White counterparts (Figure 1 and Supplementary Table 5). There were mixed results among NH/PI men and women. Compared with White men, Native Hawaiian men had significantly greater odds of CHF and stroke, whereas Other Pacific Islander men had significantly lower odds of all CVD conditions and stroke. Native Hawaiian women had significantly lower odds of other heart conditions but greater odds of stroke than White women, and Other Pacific Islander women had significantly lower odds of all CVD conditions and stroke.

Figure 1.

Adjusted odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals of self-reported cardiovascular disease type and stroke, by sex and racial/ethnic group, Medicare Health Outcomes Survey, 2011–2015.

Association Between CVD Risk Factors and CVD Conditions

We also examined the association between CVD risk factors and CVD conditions and stroke. In the adjusted model, diagnoses of hypertension and diabetes and smoking every day and somedays were positively associated with all CVD conditions and stroke. BMI was associated with CAD, CHF, and MI, such that underweight, overweight, and obese individuals had significantly greater risk of CVD than normal weight individuals. The statistical significance varied for the associations between BMI and other heart conditions and stroke. For instance, underweight and obese adults had greater risk and overweight adults had lower risk of other heart conditions than did normal weight individuals. For stroke, underweight adults had significantly greater risk of stroke than normal weight adults, whereas overweight and obese adults had significantly lower risk of stroke.

Association of Language Spoken and English Proficiency With CVD Conditions

With the exception of Japanese adults, the majority of Asian American subgroups did not speak English at home, with the prevalence ranging from 8% in Japanese to 85% in Vietnamese adults. Among Asian American subgroups, low English proficiency (ie, speaking English well or not at all) ranged from 9% among Japanese to 72% among Vietnamese adults. The majority of Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander adults spoke English at home and were proficient in English. In the analyses adjusting for all covariates, English proficiency and main language spoken at home did not change the relationship between race/ethnicity and CVD conditions and stroke.

Discussion

Our study focused on the CVD risk factors and CVD conditions for Asian American and NH/PI older adults to better characterize health of these racial/ethnic minority groups in the United States. The HOS data have expanded Asian American and NH/PI racial/ethnic categories, which allowed us to examine CVD risk factors and CVD conditions for disaggregated Asian American and NH/PI subgroups. We used Andersen and Newman’s conceptual framework to frame our research assumptions around the racialized experiences of Asian American and NH/PI older adults to understand the factors influencing CVD health care utilization (31).

We found that NH/PI adults experienced a greater burden of obesity, diabetes, hypertension, and smoking compared with White and Asian American adults, which is also supported by prior research (37,38). The disproportionate CVD burden can partially be explained by the long history of colonization and structural racism that has resulted in the perpetual disenfranchisement of NH/PI communities, overrepresentation of NH/PIs in hazardous environments, suboptimal access to health care, and low socioeconomic status (16,25,39). We were able to disaggregate the NH/PI racial category and observed variation across the NH/PI subgroups, emphasizing the need to collect and report disaggregated racial/ethnic data when possible. For instance, we found that 15% of Native Hawaiian women reported smoking every day or some days compared with Other Pacific Islander women (6%) and 45% of Other Pacific Islander men reported diabetes compared with 37% of Native Hawaiian men. Prior research has reported that CVD mortality was 4 times higher among Native Hawaiians with diabetes than Native Hawaiians without diabetes (7), highlighting the importance of focusing on NH/PI adults as a priority population. Structural racism and the accumulation of socioeconomic disadvantages are pervasive in the NH/PI community and mitigating these disparities will require culturally concordant health interventions, as well as racial/ethnic data to critically inform and evaluate evidence-based practices. An innovative example of a culturally appropriate CVD-risk management program for Native Hawaiians is the Kā-HOLO (Hula Optimizing Lifestyle Options) Project that uses hula intervention, hypertension education, and hypertension self-management course to increase physical activity and reduce hypertension risk (40). This study has a robust 2-arm randomized controlled trial with a wait-list control experimental design that centers the intervention on Native Hawaiian culture and community, increases the adoption and sustainability, and administers culturally relevant measures (eg, Native Hawaiian Cultural Identity Scale, Spirituality Questionnaire, and Awareness of Connectedness Scale) that could mediate hypertension control (40).

Our study demonstrates high prevalence of overweight (except for Vietnamese and Multiple-race Asian) and diabetes (except for Multiple-race Asian), among Asian Americans and hypertension among Filipino adults, compared with White adults and substantial variation in the prevalence of CVD risk factors across Asian American and NH/PI subgroups. For example, our findings that Filipino men and women had greatest prevalence of overweight and obesity and hypertension compared with other Asian American subgroups (26,41) and that all Asian American groups had higher prevalence of diabetes compared with White adults (26) are consistent with prior research. A possible explanation for our high prevalence of overweight and obesity is that we used the WHO recommended thresholds for overweight and obesity for Asian American subgroups. Previous research reported that more than half of Chinese, Filipino, Japanese, Korean, and South Asian adults were overweight or obese using the Asian-specific BMI criteria (26). We also found that diabetes rates were higher among Vietnamese, Koreans, Filipinos, and South Asians in the lower BMI thresholds (BMI = 23–24.9 kg/m2) compared with White adults (26). This suggests that the prevalence of diabetes and prediabetes among our sample could be underdiagnosed. Early detection of CVD risk factors through preventative screening and routine care, as well as identifying relevant sociocultural and behavioral levers, could highlight the differences in CVD outcomes and screening practices among Asian and NH/PI subgroups and guide which high-risk groups to focus health promotion activities.

Our CVD prevalence were similar (42) or higher (8,23,43) than previous studies. Our finding that Native Hawaiian adults are more likely to report stroke than White adults is consistent with prior research (8), whereas the finding that lower odds of reporting CVD conditions among Asian American subgroups than among White adults is conflicting with prior research (21,43,44). One explanation for this could be that our data were limited to larger categories of CVD conditions. For instance, Japanese adults were found to have greater risk of subarachnoid hemorrhage than White adults, whereas Filipino adults had greater incidence of intracerebral hemorrhagic stroke (44), and high prevalence of ASCVD among South Asian adults (22). Some other reasons for these observed differences include our study focus on older adults, a national sample (versus California sample), adults enrolled in Medicare Advantage organizations (vs Kaiser Permanente Northern California system), and use of self-report data (vs International Classification of Diseases codes from electronic health records) (7,8,42,43). Lower CVD risk may also be explained by unmeasured protective individual- or contextual-level enabling factors, such as family support or community cohesion, which may improve the resources available to access health care. It is also worth noting that Multiple-race Asian adults in our sample generally reported high prevalence of CVD risk factors and CVD conditions compared with other Asian American subgroups, which may warrant further investigation into the health of multiracial populations.

Compared with White adults, we found that more Asian American and NH/PI adults reported having less than a high school degree, income less than $10 000, and Medicare/Medicaid. This finding is consistent with previous studies that refute the model minority stereotype (ie, Asian Americans are wealthier and attained more education compared with racial/ethnic minority groups) (45). In relation to our theoretical model, we expect that an individual with lower social status (lower education attainment) would also have less access to enabling resources (income and insurance) to prevent or treat health issues (CVD risk factors). This pathway could partially explain the distinct patterning of CVD risk factors and CVD conditions by racial/ethnic groups. There is strong evidence that socioeconomic factors adversely affect health outcomes, underscoring the need to better address the social determinants of health underlying the high prevalence of CVD risk factors in Asian American and NH/PI subgroups (46). The variation of predisposing factors by ethnic group could also indicate the heterogeneity in immigration and acculturation experiences.

Our subanalyses on the moderating effects of language mainly spoken at home and English proficiency showed little evidence that language proficiency impacts CVD health, which is consistent with the mixed associations between acculturation measures and health outcomes (14). Collecting acculturation information such as year of entry into the United States, country of origin, or English proficiency could improve our understanding of health behaviors, the drivers of better or worse CVD in disaggregated Asian American and NH/PI subgroups, particularly among high-risk groups. Understanding the mechanisms in which acculturation and racism might be functioning in CVD disparities would shift the focus toward addressing social determinants of health, like limited health care access and culturally insensitive clinical interactions.

When interpreting our results, this study has several limitations that should be noted. First, as a cross-sectional analysis, we are unable to determine the causal mechanisms that may explain the variation in associations among race/ethnicity and CVD. Second, the HOS are self-reported data and subject to recall bias and were limited in the survey administration and follow-up languages. The HOS does not have detailed information about the type of CVD diagnoses, when CVD events happened or how long individuals have been diagnosed with CVD risk factors or CVD conditions. For example, some Asian American subgroups have greater incidence of subarachnoid and intracerebral hemorrhagic stroke than Whites, but the details of stroke were confined to yes or no (21). Third, our findings might be underestimating the prevalence of CVD risk factors and outcomes, particularly among immigrants and noncitizens, non-Chinese or non-English proficient respondents, and older adults not enrolled in Medicare. The focus on older adults may be excluding individuals less than 65 years old who have CVD and have biases toward individuals who survived into older age and were healthy enough to answer the survey. South Asians have been found to develop CHD before the age of 40 and were of younger age at hospitalization for heart failure (48). We were unable to control for traditional or lifestyle risk factors, such as diet and physical inactivity. For instance, low or insufficient levels of physical activity have been reported in Asian American and NH/PI subgroups compared with Whites (21,25). The HOS physical activity questions are framed around communication with a provider about physical exercise and not frequency or intensity of physical exercise. Fourth, we had to combine data for the other Pacific Islander groups due to small sample sizes. We acknowledge that there is variation across Asian American and NH/PI subgroups and that these data are not reflective of the heterogeneity of CVD for other Asian American (eg, Bangladeshi) and NH/PI (eg, Chamorro) subgroups. However, we were able to describe CVD risk factors and CVD among a large and diverse sample of Asian American and NH/PI community-dwelling older adults. Lastly, the HOS asks about language mainly spoken at home and how well respondents speak English, but these questions were not consistently asked for all survey years. The HOS also does not collect information on acculturation or experiences of racism. We included whether a proxy completed the survey to account for ability to complete the survey due to possible language limitations or health status. However, these variables may not fully account for comprehension of survey questions and understanding of CVD conditions (47,49). Despite these limitations, our study provides crucial insights into the associations among disaggregated Asian American and NH/PI subgroups and CVD. Future research should oversample and disaggregate racial/ethnic group information whenever possible to provide accurate depictions of health and ensure ability to test research hypotheses. For recruitment and oversampling of hard-to-reach populations, the protocols utilized for the NH/PI National Health Interview Survey are an example of how national surveys might employ strategies for sampling and increasing response rates (50).

The current study describes the burden of CVD risk factors and CVD prevalence among Asian American and NH/PI older adults and identifies subgroups at high risk for CVD. More attention should be focused on NH/PI groups as a priority population based on our finding that NH/PI adults were more likely to report CVD risk factors and CVD conditions compared with their White and Asian American counterparts. Our findings are underscored by the disproportionate impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on Asian American (51) and NH/PI (52) populations. Factors such as older age and underlying chronic conditions (53) are also strongly associated with increased severity of COVID-19 illness, which makes Asian American and NH/PI older adults at high risk for CVD, a particularly vulnerable population. The solutions to achieve health equity for Asian American and NH/PI older adults are complex and will require health promotion and interventions efforts that are culturally and linguistically relevant and address the multilevel social determinants of health.

Funding

L.N.Ð. was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) National Institute on Aging (NIA) Award Number R36AG060132 at Oregon State University. L.N.Ð. is supported by National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD) Award Number U54MD000538, and the preparation of this manuscript was supported in part by NIA Award Number 5P30AG059302, U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Award Numbers NU38OT2020001477, CFDA number 93.421 and 1NH23IP922639-01-00, CFDA number 93.185. K.H. was supported by the Jo Anne Leonard Petersen fund in Gerontology and Family Studies. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH or CDC.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Sheryl Thorburn for her careful review of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

References

- 1. Bell SP, Saraf AA. Epidemiology of multimorbidity in older adults with cardiovascular disease. Clin Geriatr Med. 2016;32(2):215–226. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2016.01.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Khavjou O, Phelps D, Leib A.. Projections of Cardiovascular Disease Prevalence and Costs: 2015–2035. RTI International; 2016. http://www.heart.org/idc/groups/heart-public/@wcm/@adv/documents/downloadable/ucm_491513.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Vital signs: avoidable deaths from heart disease, stroke, and hypertensive disease - United States, 2001-2010. MMWR. 2013;62(35):721–727. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Heron M. Deaths: Leading Causes for 2017. National Center for Health Statistics; 2019:77. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr68/nvsr68_06-508.pdf [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Jose PO, Frank AT, Kapphahn KI, et al. Cardiovascular disease mortality in Asian Americans. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64(23):2486–2494. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.08.048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Iyer Divya G, Shah Nilay S, Hastings Katherine G, et al. Years of potential life lost because of cardiovascular disease in Asian-American Subgroups, 2003–2012. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8(7):e010744. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.118.010744 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Aluli NE, Reyes PW, Brady SK, et al. All-cause and CVD mortality in Native Hawaiians. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2010;89(1):65–71. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2010.03.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Aluli NE, Reyes PW, Tsark JU. Cardiovascular disease disparities in native Hawaiians. J Cardiometab Syndr. 2007;2(4):250–253. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-4564.2007.07560.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Projected Race and Hispanic Origin: Main Projections Series for the United States, 2017-2060. Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau, Population Division. https://www2.census.gov/programs-surveys/popproj/tables/2017/2017-summary-tables/np2017-t4.xlsxhttps://www2.census.gov/programs-surveys/popproj/tables/2017/2017-summary-tables/np2017-t4.xlsx [Google Scholar]

- 10. He W, Goodkind D, Kowal P; U.S. Census Bureau . An Aging World: 2015. U.S. Government Publishing Office; 2016:175. [Google Scholar]

- 11. National Asian Pacific Center on Aging. Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders in the United States Aged 65 Years and Older: Population, Nativity, and Language. National Asian Pacific Center on Aging; 2013. http://napca.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/65+-population-report-FINAL.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 12. Office of Management and Budget. Revisions to the Standards for the Classification of FederalData on Race and Ethnicity. Office of the Federal Register, National Archives and Records Administration; 1997;62(210):58782–58790. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-1997-10-30/pdf/97-28653.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 13. Islam NS, Khan S, Kwon S, Jang D, Ro M, Trinh-Shevrin C. Methodological issues in the collection, analysis, and reporting of granular data in Asian American populations: historical challenges and potential solutions. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2010;21(4):1354–1381. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2010.0939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zhang YL, Tsai JL. The assessment of acculturation, enculturation, and culture in Asian-American samples. In: Benuto L, Thaler N, Leany B, eds. Guide to psychological assessment with Asians. New York, NY: Springer; 2014. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-0796-0_6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Asian & Pacific Islander American Health Forum. Health Care for COFA Citizens. Factsheet.2019. https://www.apiahf.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/2018.08.02_Health-Care-for-COFA-Citizens_Factsheet-V.4.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 16. Baumhofer NK, Yamane C. 19. Multilevel racism and native Hawaiian health. In: Ford CL, Griffith DM, Bruce MA, Gilbert KL, eds. Racism: Science & Tools for the Public Health Professional. American Public Health Association; 2019;375– 392. doi: 10.2105/9780875533049ch19 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gee GC, Sangalang CC, Morey BN, Hing AK. The global and historical nature of racism and health among Asian Americans. In: Ford CL, Griffith DM, Bruce MA, Gilbert KL, eds. Racism: Science & Tools for the Public Health Professional. Published online January 2019;393–412. https://ajph.aphapublications.org/doi/abs/10.2105/9780875533049ch20 [Google Scholar]

- 18. Virani SS, Alonso A, Benjamin EJ, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics – 2020 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2020;141(9):e139–e596. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Healthy People 2020. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion.https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/heart-disease-and-stroke/national-snapshot

- 20. Rodriguez F, Chung S, Blum MR, Coulet A, Basu S, Palaniappan LP. Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk prediction in disaggregated Asian and Hispanic subgroups using electronic health records. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8(14):e011874. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.118.011874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Palaniappan LP, Araneta MRG, Assimes TL, et al. Call to action: cardiovascular disease in Asian Americans: a science advisory from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2010;122(12):1242–1252. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3181f22af4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Volgman AS, Palaniappan LS, Aggarwal NT, et al. Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease in South Asians in the United States: epidemiology, risk factors, and treatments: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2018;138(1):e1–e34. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Adia AC, Nazareno J, Operario D, Ponce NA. Health Conditions, Outcomes, and Service Access Among Filipino, Vietnamese, Chinese, Japanese, and Korean Adults in California, 2011–2017. Am J Public Health. 2020;110(4):520–526 doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2019.305523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rao M, Bar L, Yu Y, et al. Disaggregating Asian American cigarette and alternative tobacco product use: results from the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) 2006–2018. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. Published online April 28, 2021. doi: 10.1007/s40615-021-01024-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mau MK, Sinclair K, Saito EP, Baumhofer KN, Kaholokula JK. Cardiometabolic health disparities in native Hawaiians and other Pacific Islanders. Epidemiol Rev. 2009;31:113–129. doi: 10.1093/ajerev/mxp004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Jih J, Mukherjea A, Vittinghoff E, et al. Using appropriate body mass index cut points for overweight and obesity among Asian Americans. Prev Med. 2014;65:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.04.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Jacobson G, Damico A, Neuman T, Gold M.. Medicare Advantage 2017 Spotlight: Enrollment Market Update. Kaiser Family Foundation; 2017:23. http://files.kff.org/attachment/Issue-Brief-Medicare-Advantage-2017-Spotlight-Enrollment-Market-Update [Google Scholar]

- 28. National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA). HEDIS 2015, Volume 6: Specifications for the Medicare Health Outcomes Survey. NCQA Publication. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Williams DR, Lawrence JA, Davis BA. Racism and health: evidence and needed research. Annu Rev Public Health. 2019;40:105–125. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040218-043750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Chaves K, Wilson N, Gray D, Barton B, Bonnett D, Azam I.. 2018 National Healthcare Quality and Disparities Report. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2019:222. Accessed June 4, 2021. https://www.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/wysiwyg/research/findings/nhqrdr/2018qdr.pdf [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Andersen R, Newman JF. Societal and individual determinants of medical care utilization in the United States. Milbank Q. 2005;83(4). doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2005.00428.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Eaton CB. Traditional and emerging risk factors for cardiovascular disease. Prim Care. 2005;32(4):963–976, vii. doi: 10.1016/j.pop.2005.09.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kaplan GA, Keil JE. Socioeconomic factors and cardiovascular disease: a review of the literature. Circulation. 1993;88(4 Pt 1):1973–1998. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.88.4.1973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. WHO Expert Consultation. Appropriate body-mass index for Asian populations and its implications for policy and intervention strategies. Lancet. 2004;363(9403):157–163. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)15268-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. RStudio Team. RStudio: Integrated Development Environment for R. RStudio, Inc; 2016. http://www.rstudio.com/. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Garcia M, Mulvagh SL, Merz CN, Buring JE, Manson JE. Cardiovascular disease in women: clinical perspectives. Circ Res. 2016;118(8):1273–1293. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.307547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Uchima O, Wu YY, Browne C, Braun KL. Disparities in diabetes prevalence among Native Hawaiians/Other Pacific Islanders and Asians in Hawai’i. Prev Chronic Dis. 2019;16:E22. doi: 10.5888/pcd16.180187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lucas JW, Benson V.. Tables of Summary Health Statistics for the U.S. Population: 2018 National Health Interview Survey. National Center for Health Statistics; 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/SHS/tables.htm [Google Scholar]

- 39. Morey BN, Tulua A, Tanjasiri SP, et al. Structural racism and its effects on native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders in the United States: issues of health equity, census undercounting, and voter disenfranchisement. AAPI Nexus: Policy Pract Community. 2020;17(1–2). https://www.aapinexus.org/2020/11/24/structural-racism-and-its-effects-on-native-hawaiians-and-pacific-islanders/ [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kaholokula JK, Look MA, Wills TA, et al. Kā-HOLO Project: a protocol for a randomized controlled trial of a native cultural dance program for cardiovascular disease prevention in Native Hawaiians. BMC Public Health. 2017;17(1):321. doi: 10.1186/s12889-017-4246-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Zhao B, Jose PO, Pu J, et al. Racial/ethnic differences in hypertension prevalence, treatment, and control for outpatients in northern California 2010–2012. Am J Hypertens. 2015;28(5):631–639. doi: 10.1093/ajh/hpu189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Mayeda ER, Glymour MM, Quesenberry CP Jr, Whitmer RA. Heterogeneity in 14-year dementia incidence between Asian American subgroups. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2017;31(3):181–186. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0000000000000189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Holland AT, Wong EC, Lauderdale DS, Palaniappan LP. Spectrum of cardiovascular diseases in Asian-American racial/ethnic subgroups. Ann Epidemiol. 2011;21(8):608–614. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2011.04.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Klatsky AL, Friedman GD, Sidney S, Kipp H, Kubo A, Armstrong MA. Risk of hemorrhagic stroke in Asian American ethnic groups. Neuroepidemiology. 2005;25(1):26–31. doi: 10.1159/000085310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. National Asian Pacific Center on Aging. Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders in the United States Aged 65 Years and Older: Economic Indicators. Vol. 8. National Asian Pacific Center on Aging; 2013. Accessed August 12, 2018. https://napca.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/economic-indicators-FINAL.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 46. Havranek EP, Mujahid MS, Barr DA, et al. Social determinants of risk and outcomes for cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 2015;132(9):873–898. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Nguyen TT, Liao Y, Gildengorin G, Tsoh J, Bui-Tong N, McPhee SJ. Cardiovascular risk factors and knowledge of symptoms among Vietnamese Americans. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(2):238–243. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0889-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Gupta M, Singh N, Verma S. South Asians and cardiovascular risk: what clinicians should know. Circulation. 2006;113(25):e924–e929. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.583815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Felix H, Narcisse M-R, Rowland B, Long CR, Bursac Z, McElfish PA. Level of recommended heart attack knowledge among native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander adults in the United States. Hawaii J Med Public Health. 2019;78(2):61–65. Accessed February 20, 2020. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6369889/ [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Galinsky AM, Simile C, Zelaya CE, Norris T, Panapasa SV. Surveying strategies for hard-to-survey populations: lessons from the Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander National Health Interview Survey. Am J Public Health. 2019;109(10):1384–1391. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2019.305217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Yan BW, Hwang AL, Ng F, Chu JN, Tsoh JY, Nguyen TT. Death toll of COVID-19 on Asian Americans: disparities revealed. J Gen Intern Med. 2021;1–5. doi: 10.1007/s11606-021-07003-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Kaholokula JK, Samoa RA, Miyamoto RES, Palafox N, Daniels S-A. COVID-19 special column: COVID-19 hits Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander communities the hardest. Hawaii J Health Soc Welf. 2020;79(5):144–146. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Yang J, Zheng Y, Gou X, et al. Prevalence of comorbidities and its effects in patients infected with SARS-CoV-2: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;94:91–95. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.03.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.