Abstract

Objective

We aimed to describe opioid prescribing practices after obstetric delivery and to evaluate how these practices compare with national opioid prescribing guidelines.

Methods

A closed survey was developed, evaluated for validity and reliability, and distributed by email to obstetrician members of the Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada (SOGC) in December 2018. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize respondent demographics, pharmaceutical pain management strategies, and opioid prescribing practices. Logistic regression was used to measure associations between respondent characteristics and high-risk opioid prescribing practices (e.g., prescribing >50 mg morphine equivalent dose per day, prescribing >5 days, not screening for substance/opioid use disorder before prescribing).

Results

Our survey had high content validity (content validity index 0.89; 95% CI 0.78–1.00) and adequate reliability (Kappa 0.70; 95% CI 0.63–0.84 and intraclass correlation coefficient 0.70; 95% CI 0.67–0.81). Of the 1019 SOGC members reached, 243 initiated the survey (response rate, 24%). Among respondents, 235 (92%) completed the survey. Among opioid prescribers, 47% reported at least 1 high-risk opioid prescribing practice, the most frequent being a lack of substance/opioid use disorder screening. In the adjusted logistic regression model, being in practice more than 20 years (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 0.53; 95% CI 0.29–0.93) and practising in a non-central area of Canada (aOR 0.49; 95% CI 0.28–0.84) reduced the odds of high-risk prescribing.

Conclusion

Further research on barriers to screening are needed to support and enhance safer opioid prescribing practices among Canadian obstetricians.

Keywords: pain management, opioids, delivery, obstetrics, addiction, substance use

INTRODUCTION

Canada continues to experience a public health crisis related to opioid-related morbidity and mortality.1 Among opioid-naive patients, prescription of opioid analgesics after minor surgery is associated with an increased risk of long-term use compared with patients treated with non-opioid analgesics.2 In Canada, between 2018 and 2019, the most common inpatient surgery and reason for hospitalization were cesarean delivery and obstetric delivery, respectively.3 Data from the United States revealed that prescribing of opioids after cesarean delivery was associated with one in 300 women persistently using opioids at 1 year postpartum.4 In addition, a higher dose (>112.5 mg morphine equivalents dose per day [MED/day]) was associated with a 30% relative increase in persistent use compared to doses under 112.5 mg MED/day.4 Another U.S. study demonstrated that the amount of opioids prescribed after cesarean delivery generally exceeded the amount used by women, leading to leftover medication5 at risk for diversion.6, 7, 8, 9

Part of the response to the opioid epidemic has been the development of opioid-prescribing guidelines,10, 11 which aim to curb overprescribing, limit excess opioids available for diversion, and reduce harms associated with opioid use. Guidelines have predominantly focused on chronic pain,9 but the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) guideline offers specific recommendations for acute or postoperative pain that are applicable to procedures such as cesarean delivery. Based on studies linking high-risk prescribing with adverse outcomes, the CDC and Canadian guidelines emphasize (1) prescribing less than 50 mg MED/day; (2) providing short prescription durations (3–7 days); and (3) applying universal screening for substance use disorders (SUD) and opioid use disorders (OUD) before prescribing opioids.10, 11, 12

U.S. surveys of obstetrician gynaecologists have found great geographic variability in prescribing of opioids after obstetric delivery.13 Other studies have investigated provider characteristics associated with screening for substance use among pregnant women, but there are minimal data on characteristics associated with high-risk opioid-prescribing practices.14 Understanding whether certain prescribers (e.g., from specific geographic areas, practice types [academic vs. community], and age groups) are more or less likely to have high-risk prescribing behaviours could help guide educational or support interventions, but data are lacking in the Canadian context.

To address this knowledge gap, we conducted a survey of obstetrician members of the Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada (SOCG). Our aim was to describe opioid-prescribing practices at patient discharge from the hospital after vaginal and cesarean delivery and to assess for high-risk prescribing practices as defined by Canadian and CDC guidelines.10, 11 Our secondary aim was to evaluate physician characteristics associated with high-risk opioid-prescribing practices.

METHODS

Survey Development

A 22-item closed-ended questionnaire (online Appendix A) was developed with input from obstetric medicine, obstetrics-gynaecology, maternal-fetal medicine, addiction medicine, and survey method experts (M.H., E.M., N.D., S.G., A.E.-M., and C.L.). The survey solicited information in four areas: (1) prescriber demographic characteristics; (2) pharmaceutical pain management strategies; (3) SUD and OUD screening and opioid-prescribing safety practices; and (4) self-reported perceptions of the role of opioids in post-delivery care (online Appendix B, tables of survey elements and measures). Adaptive answering was used for sections two and three of the survey.

Survey Validation

The questionnaire items and format were pilot tested for clarity and face validity via a narrative expert review by a panel of five obstetricians at the McGill University Health Centre. In addition, we completed a formal quantitative content validation analysis using the Content Validity Index15 with the aid of six external expert reviewers, including two addiction specialists (S.Y., P.B.), a family physician with expertise in addiction and obstetrics (J.L.), two general obstetricians (S.G., C.T.), and a survey methods expert (M.C.). Items were removed or modified if rated poorly in the Content Validity Index analysis. All changes were reviewed and consensus was reached by authors.

We then evaluated test-retest reliability. Fourteen volunteer obstetricians completed the survey in its entirety twice, with a median of 4.5 days (range 0–26 days) between the first and second assessment. Reliability was evaluated using the Kappa agreement statistic for categorical variables and intraclass correlation coefficient for continuous variables.16 Our survey had high content validity (content validity index 0.89; 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.78–1.00)17 and adequate reliability (Kappa 0.70 [95% CI 0.63–0.84]; intraclass correlation coefficient 0.70 [95% CI 0.67–0.81]).18

Study Population and Survey Dissemination

The survey sampling frame consisted of physicians who listed their speciality as “obstetrics” in SOGC records. The survey was conducted in partnership with the SOGC, and SOCG staff approved the survey and were responsible for survey distribution to protect the confidentiality of SOGC members. The survey was distributed to obstetrician SOGC members by email in December 2018 using SimpleSurvey,19,20 a Canadian-hosted secure online software. Three follow-up emails from the SOGC, in accordance with Dillman’s evidence-based survey approach,20,21 were sent to non-respondents at 1-month intervals, and all members were again invited via email to participate during the annual 2019 SOGC meeting in May 2019. As indicated in our invitation letter, provision of informed consent was implicit in completing the survey (online Appendix C). Internet protocol (IP) addresses were not collected but were automatically tracked by the survey software and used to prevent duplicate entries. Individual participant anonymity was maintained. The project was approved by the McGill University Health Centre Research Ethics Board.

Analysis

All responses to survey elements were used in cases of both complete and incomplete questionnaires. The response rate was calculated as the number of participants who completed the first page of the survey divided by the number who opened the email invitation (clicked on the email or downloaded the email to a device [e.g., phone or computer]). This denominator was chosen because some email addresses in SOGC records are outdated or have email sent to junk folders. Therefore, we limited the denominator to those who “opened” the email because this was our only measure of whether the invitation to participate was received. The completion rate was calculated as the number of participants who completed the last page of the survey divided by the number who started the questionnaire.

Our main outcome variable, high-risk opioid prescribing, was defined as (1) prescribing more than 50 mg MED/day; (2) prescribing opioids routinely for a duration of more than 5 days; or (3) not always screening for SUD and OUD before prescribing opioids.10, 11, 12 Opioid prescribers were defined as responders who selected that they routinely prescribed opioids for analgesia at patient discharge after vaginal and/or cesarean delivery (see Question 1, Section 2 in online Appendix A). Non–opioid prescribers were respondents who did not report routinely prescribing opioids for analgesia at patient discharge after obstetric delivery. Non–opioid prescribers reported using only non-opioid analgesics such as acetaminophen or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (see Question 1, Section 2 in online Appendix A). Other secondary outcomes included opioid prescription safety measures, defined as splitting prescription dispensation, writing a prescription expiry date, and using the hospital’s pre-printed or automated opioid discharge protocol; and perceptions of the role of opioids in post-delivery care, defined as responders’ agreement that opioids are an important aspect of post-delivery care, that opioids prescribed for pain do not carry addiction risk, that an opioid postpartum prescription tool aid would be beneficial, and that they have high comfort in opioid prescribing.

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize characteristics of responders and the outcome variables. To assess our secondary aim, we used logistic regression to estimate the association between responder characteristics (responder sex, years in practice, site of practice, practice in an urban or rural area, geographic region of practice, type of practice, and number of deliveries per year) previously found or hypothesized based on clinical knowledge to be associated with high-risk opioid prescribing. The multivariable model was adjusted for geographic region and the number of years in practice because these characteristics have been shown to affect postpartum opioid-prescribing patterns.13, 22, 23, 24 All analyses were conducted using R statistical software (RStudio, version 3.5.1).

RESULTS

Of the 1410 SOGC members listing obstetrics as their specialty who received an invitation to participate, 391 did not open the email invitation, leaving an effective sample size of 1019. A total of 243 completed the first section of the survey, yielding a 24% response rate. The survey was fully completed by 92% of respondents (n = 223). Table 1 summarizes respondent characteristics. Respondents were mostly female (78%), in practice for less than 20 years (70%), general obstetricians (86%), and practicing in larger academic centres in central Canada (Ontario, Québec, and Nunavut) (65%). More respondents with the following characteristics routinely prescribed opioids at patient discharge post-delivery: those in practice for less than 20 years (73% vs. 69%), those practicing in centres serving smaller populations (39% vs. 31%) with fewer deliveries (58% vs. 54%), maternal-fetal medicine obstetricians (16% vs. 11%), and those practicing in central Canada (75% vs. 48%).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics in non-opioid and opioid prescribers

| No. (%) of respondents | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Total sample; n=243 | Non–opioid prescribersa; n=89b | Opioid prescribers; n= 146 | |

| Characteristics | |||

| Sex | |||

| Female | 190 (78) | 70 (79) | 113 (77) |

| Male | 52 (21) | 18 (20) | 33 (23) |

| Missing | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 |

| Years in practice | |||

| ≤20 | 171 (70) | 61 (69) | 106 (73) |

| >20 | 72 (30) | 28 (31) | 40 (27) |

| Site of practice | |||

| Academic affiliation | 208 (86) | 76 (85) | 126 (86) |

| No academic affiliation | 35 (14) | 13 (15) | 20 (14) |

| Urban or rural practice | |||

| Population <99,999 | 85 (35) | 28 (31) | 57 (39) |

| Population >100,000 | 158 (65) | 61 (69) | 89 (61) |

| Canadian geographic region of practice | |||

| Centralc | 159 (65) | 43 (48) | 109 (75) |

| Non-centrald | 84 (35) | 46 (52) | 37 (25) |

| Type of practice | |||

| General obstetrics | 209 (86) | 79 (89) | 123 (84) |

| Maternal-fetal medicine | 34 (14) | 10 (11) | 23 (16) |

| Average no. of deliveries per year | |||

| ≤3000 | 139 (57) | 48 (54) | 85 (58) |

| >3000 | 104 (43) | 41 (46) | 61 (42) |

| Screening and opioid prescribing safety practices | |||

| Frequency of assessing patients for a history of OUD/SUD | |||

| Always | 59 (24) | 19 (21) | 40 (27) |

| Sometimes | 97 (40) | 38 (43) | 59 (40) |

| Rarely | 53 (22) | 22 (25) | 31 (21) |

| Never | 16 (7) | 8 (9) | 8 (6) |

| Missing | 18 (7) | 2 (2) | 8 (6) |

| Frequency of altering opioid prescription if participants identified an active or historical OUD/SUDe | |||

| Always | 113 (47) | 43 (48) | 70 (48) |

| Sometimes | 88 (36) | 28 (32) | 60 (41) |

| Rarely | 9 (4) | 6 (7) | 3 (2) |

| Never | 3 (1) | 3 (3) | 0 (0) |

| Missing | 30 (12) | 9 (10) | 13 (9) |

| Frequency of referral for further assessment and treatment if an active SUD is identified | |||

| Always | 97 (40) | 38 (43) | 59 (40) |

| Sometimes | 83 (34) | 34 (38) | 49 (34) |

| Rarely | 22 (9) | 4 (5) | 18 (12) |

| Never | 7 (3) | 3 (3) | 4 (3) |

| Missing | 34 (14) | 10 (11) | 16 (11) |

Non-opioid prescribers were defined as responders who did not report prescribing opioids routinely for analgesia at patient discharge after vaginal and/or cesarean delivery.

Eight participants did not indicate their opioid-prescribing practices.

Includes Québec, Ontario, and Nunavut.

Includes New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, Newfoundland and Labrador, British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Yukon, and Northwest Territories.

Sixteen participants reported never screening for OUD/SUD before prescribing opioids; therefore, adaptive answering meant these respondents did not see this question and are counted as missing.

OUD: opioid use disorder; SUD: substance use disorder.

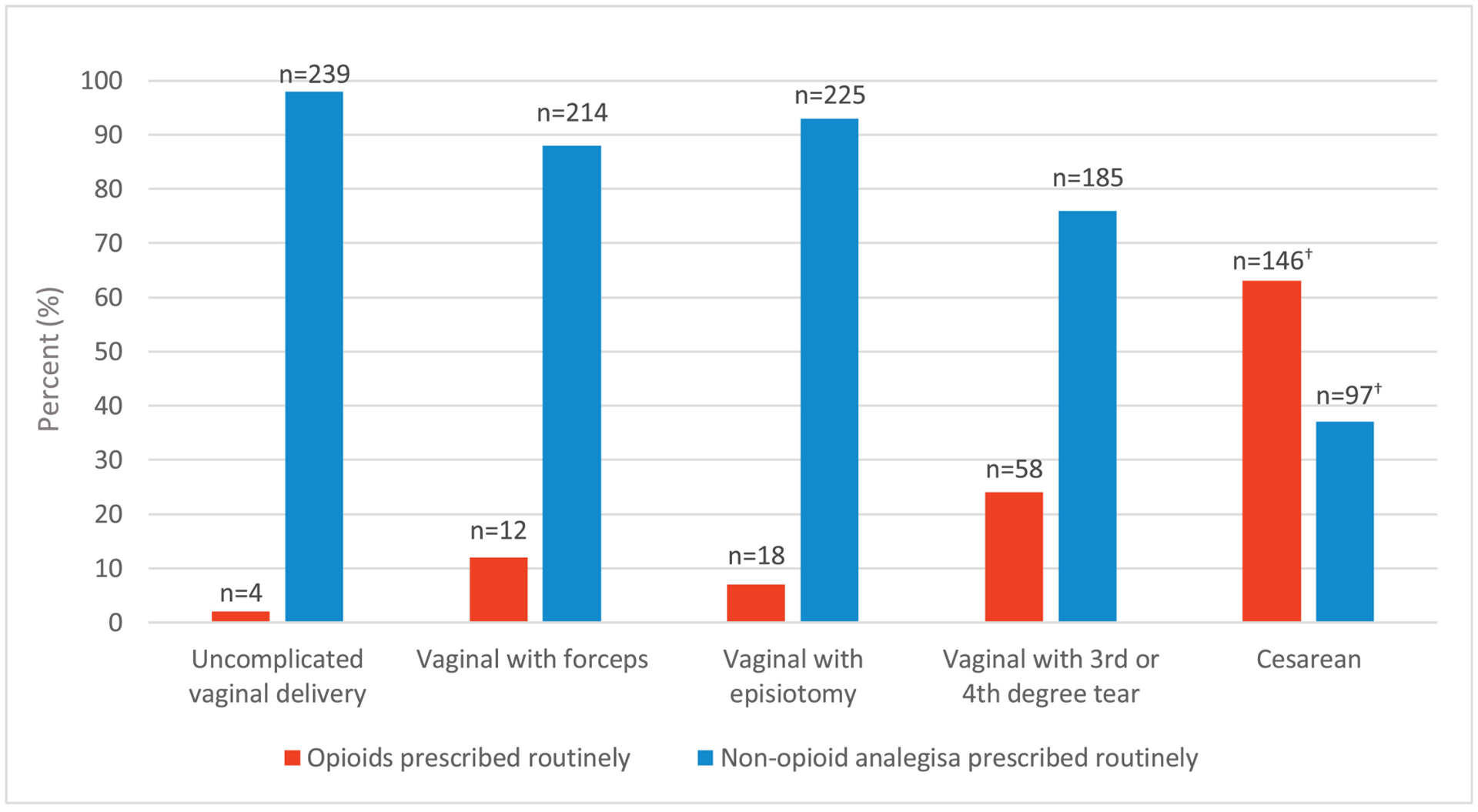

We found that 37% of respondents did not routinely prescribe opioids post-delivery. Among opioid prescribers, few reported routinely prescribing opioids after uncomplicated vaginal delivery (Figure 1). However, among deliveries with increasing degrees of complication (forceps, episiotomy, or third- or fourth-degree tear) and cesarean deliveries, opioid-prescribing rates increased (Figure 1). The median prescription dose and duration after complicated vaginal delivery and cesarean delivery were 30 mg MED/day (interquartile range [IQR] 20.0–49.5) for 4.5 days (IQR 3–5.75) and 30 mg MED/day (IQR 24.8–43.8) for 4 days (IQR 3–5.75), respectively. However, detailed durations and amounts were missing for 23% of opioid prescribers.

Figure 1.

Opioid versus non-opioid analgesia prescribing at discharge according to mode of delivery (n = 243).1

1Categories are not mutually exclusive, but all those who prescribed opioids for cesarean births also did so for vaginal delivery subtypes

2Missing 8 observations

Only 24% of all respondents always completed OUD/SUD screening before prescribing opioids. Slightly fewer opioid prescribers referred patients identified as having an OUD for further treatment than did non-prescribers. Less than 15% of respondents routinely used prescription safety techniques, including writing a prescription expiry date, splitting prescription dispensation, or using a pre-printed/automated opioid discharge protocol. Perceptions of the role of opioids in post-delivery care differed between opioid prescribers and non-prescribers. Fifty-two percent of prescribers versus 14% of non-prescribers believed opioid analgesia was an important aspect of care. Similarly, a greater number of opioid prescribers (94% vs. 73%) felt comfortable prescribing opioids in this setting. Fifty-three versus 41% of prescribers versus non-prescribers believed that there was a risk for addiction, and more prescribers (59% vs. 47%) desired an online tool to address how to prescribe opioids postpartum (Table 2).

Table 2.

Perceptions of the role of opioids in post-delivery care and addiction risk

| No. (%) of respondents | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total sample; n=224a | Non–opioid prescribers; n=86 | Opioid prescribers; n=138 | |||||||

| Perception | Agreeb | Neutral | Disagreeb | Agree | Neutral | Disagree | Agree | Neutral | Disagree |

| Opioid analgesia is an important aspect of post-delivery pain managementb | 84 (37) | 37 (17) | 102 (4) | 12 (14) | 10 (12) | 64 (74) | 72 (52) | 28 (20) | 38 (28) |

| I feel comfortable prescribing opioids when appropriate for pain post-deliveryb | 192 (86) | 19 (8) | 13 (6) | 63 (73) | 13 (15) | 10 (8) | 129 (94) | 6 (4) | 3 (2) |

| I believe that when opioids are prescribed to treat pain, it is unlikely that patients will develop opioid dependencyb | 108 (48) | 37 (16) | 79 (36) | 35 (41) | 15 (17) | 36 (42) | 73 (53) | 22 (16) | 43 (31) |

| I feel that an online tool on how to prescribe opioids postpartum would be helpful for my practiceb | 121 (54) | 66 (30) | 37 (16) | 40 (47) | 26 (30) | 20 (23) | 81 (59) | 40 (29) | 17 (12) |

Nineteen missing observations (including the eight people who did not indicate their opioid-prescribing patterns).

Level of agreement: collapsed from strongly agree, agree, neutral, disagree, and strongly disagree to agree (strongly agree + agree), neutral, and disagree (disagree + strongly disagree).

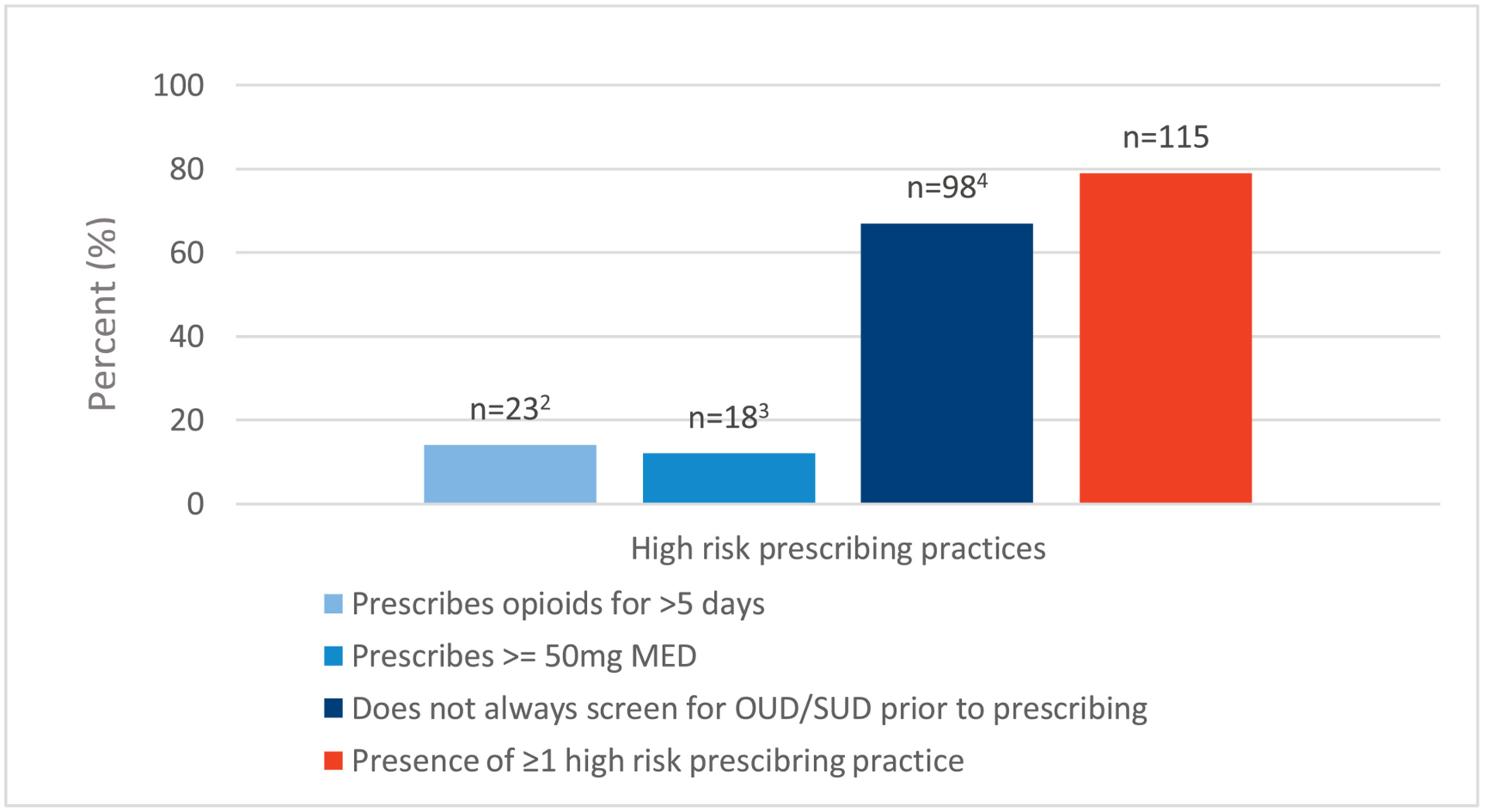

Among opioid prescribers, 47% of respondents reported at least one high-risk opioid-prescribing behaviour (Figure 2), the most frequent being a lack of screening for OUD/SUD before prescribing (79%) (Figure 2). In the unadjusted and adjusted logistic regression model, being in practice for more than 20 years (adjusted odds ratio 0.53; 95% CI 0.29–0.93) and practicing in non-central areas of Canada (adjusted odds ratio 0.49; 95% CI 0.28–0.84) reduced the odds of high-risk prescribing (Table 3).

Figure 2.

High-risk opioid prescribing practices among opioid prescribers (n = 146).1

mg; milligrams, MED; morphine equivalent dose, OUD; opioid use disorder, SUD; substance use disorder

1Categories are not mutually exclusive

2Missing 8 observations

3Missing 13 observations

4Missing 33 observations

Table 3.

Prescriber characteristics associated with odds of high-risk opioid-prescribing practices postpartum for all types of deliveries (n = 243)

| Prescriber characteristics | No. respondents with high-risk prescribing, no./n (%) | Crude odds ratio (95% CI) | Adjusted odds ratioa (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sexb | |||

| Female | 92/190 (48) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| Male | 23/52 (44) | 0.8 (0.45–1.56) | 1.2 (0.60–2.45) |

| Years in practice | |||

| ≤20 | 89/171 (52) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| >20 | 26/72 (36) | 0.5 (0.29–0.91) | 0.5 (0.29–0.93) |

| Site of practice | |||

| Academic affiliation | 99/208 (48) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| No academic affiliation | 16/35 (45) | 0.9 (0.45–1.90) | 0.9 (0.42–1.85) |

| Urban or rural practice | |||

| Population <99999 | 44/85 (52) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| Population >100000 | 71/158 (45) | 0.8 (0.45–1.29) | 0.8 (0.44–1.32) |

| Canadian geographic region of practice | |||

| Centralc | 85/159 (53) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| Non-centrald | 30/84 (36) | 0.5 (0.28–0.83) | 0.5 (0.28–0.84) |

| Type of practice | |||

| General obstetrics | 99/209 (47) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| Maternal-fetal medicine | 16/34 (47) | 1.0 (0.47–2.04) | 1.1 (0.51–2.37) |

| Average no. of deliveries/y | |||

| ≤3000 | 65/139 (47) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| >3000 | 50/104 (48) | 1.1 (0.63–1.75) | 1.1 (0.67–1.93) |

Adjusted for Canadian geographic region of practice and years in practice.

One missing observation for sex; thus, the total sample for this variable is 242.

Includes Québec, Ontario, and Nunavut.

Includes New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, Newfoundland and Labrador, British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Yukon, and Northwest Territories.

CI: confidence interval.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, our survey study is the first to capture national Canadian obstetrician opioid-prescribing practices at patient discharge post-delivery. We found that only 24% of all respondents always completed OUD/SUD screening before prescribing opioids. Thirty-seven percent of respondents did not report routinely prescribing opioids at discharge post-delivery, and perceptions of the role of opioids in post-delivery care differed between opioid prescribers and non-prescribers. Among opioid prescribers, 47% of obstetricians had high-risk practices according to U.S. and Canadian guidelines, and being in practice for more than 20 years and practicing outside of central Canada were associated with reduced odds of high-risk prescribing. We also found that few respondents reported using prescription safety techniques.

U.S. studies have also revealed geographic variability in postpartum opioid-prescribing practices. Becker et al.,13 using national claims data from insured women in the United States, found a wide degree of variation in use of prescription opioids after uncomplicated vaginal deliveries (range 9.5%–46.8%); southern states had the highest rate of use, and the lowest rates were noted in the northeast and mid-Atlantic states. A survey study by Baruch et al.22 evaluating opioid prescribing practices among U.S. obstetrics/gynaecology residents found that training in the western United States was associated with prescribing more opioids postpartum.

Without patient-level data, it is impossible to determine whether the geographic variation noted in our study reflects differences in the patient population or prescriber behaviour linked to social norms of safe prescribing practices, which have been shown elsewhere to influence individual physician prescribing.23, 25 Although the number of years in practice has been associated with risky opioid-prescribing behaviours in other populations,24 there are limited data in the postpartum population.22 Our findings, in which longer duration of practice (>20 years) was associated with a reduction in high-risk prescribing, may be attributed to academic training beginning in the 1980s, after which there was a heightened focus on pain management paired with more liberal opioid prescribing.26 Further study assessing the role of provider training and social norms on opioid prescribing postpartum are needed.

Studies have shown that a history of SUD or OUD increases the risk of opioid misuse in patients with chronic pain27, 28 and increases the risk of chronic opioid use in opioid-naive patients.29 However, we, like others,30 found that many obstetricians in our sample did not systematically screen for history of SUD and OUD before prescribing opioids. In a recent U.S. survey of American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists members, 79% reported screening for substance use during pregnancy,14 and findings from the same study population showed that less than 50% recommended medications for OUD, 60% referred for treatment or specialty care, and 22% would feel comfortable starting treatment with buprenorphine or methadone.31 One narrative review found that time constraints, lack of adequate screening tools and protocols to address substance use in pregnancy, patient-provider relationships, and perceptions of alcohol or other drug use during pregnancy were provider-reported barriers to substance use screening in pregnant women.30

We similarly found low rates of prescription safety procedures such as pre-printed or standardized opioid prescriptions at discharge, which have been shown to enhance the uptake of prescription safety practices, including screening, more generally.32 Framing screening as a part of the informed consent process so that patients can be aware of specific harms and benefits with regard to opioid treatment may also be a tool to increase screening frequency. Shared decision-making between patient and provider before prescribing opioids has been shown in pregnant women to decrease opioid prescription amounts and enhance patient satisfaction.33 Further qualitative and quantitative studies exploring barriers to screening in the Canadian context are needed to understand the low screening rates found in our study.

Our survey study had some limitations. Our response rate was only 24%, risking selection bias. However, this rate is in keeping with those in other web-based surveys of physicians, an inherently difficult group to study.34 To protect the confidentiality of SOGC members, demographic data on non-responders was not shared with our study team; therefore, we are unable to compare demographic characteristics between respondents and those who did not participate. Some respondents did not answer all questions, with rates of missing data as high as 23% on some items. There were also few respondents from non-central provinces/territories, limiting our geographic variability analysis and the generalizability of our results to these geographic regions. Our small sample size and missing data also limit the precision of our statistical results. As with all self-report survey studies, responses may have been influenced by social desirability bias.

CONCLUSION

In a national sample of Canadian obstetricians, many obstetricians reported high-risk prescribing behaviours. In particular, screening for SUD and OUD before prescribing opioids was limited, and prescription safety procedures were underutilized. Further research exploring barriers to screening in the Canadian context are needed to develop a tailored response to support and enhance safer opioid prescribing post-delivery. Future research with patient and prescription data is also needed to understand the regional variations and variations related to prescriber years in practice in the self-reported opioid-prescribing patterns found in our study so that targeted educational tools may be developed for this population.

Supplementary Material

ACKOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Dr. Robert Gagnon, Dr. Karen Wou, Dr. Paul Fournier, Dr. Cleve Ziegler, and Dr. Vincent Ponette for their help with assessing face validity by conducting a narrative review of the questionnaire. They thank Dr. Sam Young, Dr. Camille Tétreault, Dr. Paxton Bach, and Dr. Jennifer Leavitt for their assistance with the quantitative survey validation. They thank Dr. Harrison Banner, Dr. Katrina Ciraldo, Dr. Moria de Valence, Dr. Paul Fournier, Dr. Jo-Anne Hammond, Dr. Wendy Hooper, Dr. Sarah Kredentser, Dr. Lindsay Mackay, Dr. Leah Mawhinney, Dr. Justin McGinnis, Dr. Cristina Mitric, Dr. Arora Nisha, Dr. NadineSauve, and Dr. Evan Tannenbaum for their assistance with establishing survey reliability.

REFERENCES

- 1.Special Advisory Committee on the Epidemic of Opioid Overdoses. National report: apparent opioid-related deaths in Canada (January 2016 to September 2019) web-based report. Public Health Agency of Canada; 2019. Available at: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/healthy-living/national-report-apparent-opioid-related-deaths-released-march-2018.html. Accessed December 6, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alam A, Gomes T, Zheng H, et al. Long-term analgesic use after low-risk surgery: a retrospective cohort study. Arch Intern Med 2012;172:425–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Canadian Institute for Health Information. Inpatient hospitalizations, surgeries and childbirth indicators in 2018–2019. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Institute for Health Information; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bateman BT, Franklin JM, Bykov K, et al. Persistent opioid use following cesarean delivery: patterns and predictors among opioid-naive women. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2016;215:353.. e1–.e18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bateman BT, Cole NM, Maeda A, et al. Patterns of opioid prescription and use after cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol 2017;130:29–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Inciardi JA, Surratt HL, Cicero TJ, et al. Prescription opioid abuse and diversion in an urban community: the results of an ultrarapid assessment. Pain Med 2009;10:537–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kennedy-Hendricks A, Gielen A, McDonald E, et al. Medication sharing, storage, and disposal practices for opioid medications among US adults. JAMA Intern Med 2016;176:1027–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fischer B, Argento E. Prescription opioid related misuse, harms, diversion and interventions in Canada: a review. Pain Physician 2012;15(3 Suppl): ES191–203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abuse S. and Mental Health Services Administration. Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: results from the 2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (HHS Publication No. PEP19–5068, NSDUH Series H-54). Rockville, MD: Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Busse JW, Craigie S, Juurlink DN, et al. Guideline for opioid therapy and chronic noncancer pain. CMAJ 2017;189:E659–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dowell DHT, Chou R. CDC guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain — United States. MMWR Recomm Rep 2016;65(No. RR-1):1–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoots BE, Xu L, Kariisa M, et al. 2018 Annual surveillance report of drug- related risks and outcomes—United States. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Becker NV, Gibbins KJ, Perrone J, et al. Geographic variation in postpartum prescription opioid use: Opportunities to improve maternal safety. Drug Alcohol Depend 2018;188:288–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ko JY, Tong VT, Haight SC, et al. Obstetrician–gynecologists’ practices and attitudes on substance use screening during pregnancy. J Perinatol 2020;40:422–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rubio DM, Berg-Weger M, Tebb SS, et al. Objectifying content validity: conducting a content validity study in social work research. Soc Work Res 2003;27:94–104. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hallgren KA. Computing inter-rater reliability for observational data: an overview and tutorial. Tutor Quant Methods Psychol 2012;8:23–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shi J, Mo X, Sun Z. Content validity index in scale development. Zhong Nan Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban 2012;37:152–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McHugh ML. Interrater reliability: the Kappa statistic. Biochem Med 2012;22:276–82. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.SimpleSurvey. SimpleSurvey: Canada’s online survey software. Outsidesoft Solutions Inc. Proudly Canadian; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cook DA, Wittich CM, Daniels WL, et al. Incentive and reminder strategies to improve response rate for internet-based physician surveys: a randomized experiment. J Med Int Res 2016;18:e244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dillman DA. Mail and internet surveys: the tailored design method—2007 update with new internet, visual, and mixed-mode guide. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baruch AD, Morgan DM, Dalton VK, et al. Opioid prescribing patterns by obstetrics and gynecology residents in the United States. Subst Use Misuse 2018;53:70–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McDonald DC, Carlson K, Izrael D. Geographic variation in opioid prescribing in the U.S. J Pain 2012;13:988–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dhalla IA, Mamdani MM, Gomes T, et al. Clustering of opioid prescribing and opioid-related mortality among family physicians in Ontario. Can Fam Physician 2011;57:e92–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cabral C, Lucas PJ, Ingram J, et al. “It’s safer to …” parent consulting and clinician antibiotic prescribing decisions for children with respiratory tract infections: an analysis across four qualitative studies. Soc Sci Med 2015;136–7:156–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tompkins DA, Hobelmann JG, Compton P. Providing chronic pain management in the “Fifth Vital Sign” era: historical and treatment perspectives on a modern-day medical dilemma. Drug Alcohol Depend 2017;173:S11–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hylan TR, Von Korff M, Saunders K, et al. Automated prediction of risk for problem opioid use in a primary care setting. J Pain 2015;16:380–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Banta-Green CJ, Merrill JO, Doyle SR, et al. Opioid use behaviors, mental health and pain–development of a typology of chronic pain patients. Drug Alcohol Depend 2009;104:34–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sun EC, Darnall BD, Baker LC, et al. Incidence of and risk factors for chronic opioid use among opioid-naive patients in the postoperative period. JAMA Intern Med 2016;176:1286–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oni HT, Buultjens M, Abdel-Latif ME, et al. Barriers to screening pregnant women for alcohol or other drugs: a narrative synthesis. Women Birth 2019;32:479–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ko JY, Tong VT, Haight SC, et al. Obstetrician–gynecologists’ practice patterns related to opioid use during pregnancy and postpartum—United States, 2017. J Perinatol 2020;40:412–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ehringer G, Duffy B. Advances in patient safety promoting best practice and safety through preprinted physician orders. In: Henriksen K, Battles JB, Keyes MA, Grady ML, editors. Advances in Patient Safety: New Directions and Alternative Approaches, 2, Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Prabhu M, McQuaid-Hanson E, Hopp S, et al. A shared decision-making intervention to guide opioid prescribing after cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol 2017;130:42–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cunningham CT, Quan H, Hemmelgarn B, et al. Exploring physician specialist response rates to web-based surveys. BMC Med Res Methodol 2015;15:32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.