Abstract

Aims

No therapy has shown to reduce the risk of hospitalization for heart failure across the entire range of ejection fractions seen in clinical practice. We assessed the influence of ejection fraction on the effect of the sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor empagliflozin on heart failure outcomes.

Methods and results

A pooled analysis was performed on both the EMPEROR-Reduced and EMPEROR-Preserved trials (9718 patients; 4860 empagliflozin and 4858 placebo), and patients were grouped based on ejection fraction: <25% (n = 999), 25–34% (n = 2230), 35–44% (n = 1272), 45–54% (n = 2260), 55–64% (n = 2092), and ≥65% (n = 865). Outcomes assessed included (i) time to first hospitalization for heart failure or cardiovascular mortality, (ii) time to first heart failure hospitalization, (iii) total (first and recurrent) hospitalizations for heart failure, and (iv) health status assessed by the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ). The risk of cardiovascular death and hospitalization for heart failure declined progressively as ejection fraction increased from <25% to ≥65%. Empagliflozin reduced the risk of cardiovascular death or heart failure hospitalization, mainly by reducing heart failure hospitalizations. Empagliflozin reduced the risk of heart failure hospitalization by ≈30% in all ejection fraction subgroups, with an attenuated effect in patients with an ejection fraction ≥65%. Hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals were: ejection fraction <25%: 0.73 (0.55–0.96); ejection fraction 25–34%: 0.63 (0.50–0.78); ejection fraction 35–44%: 0.72 (0.52–0.98); ejection fraction 45–54%: 0.66 (0.50–0.86); ejection fraction 55–64%: 0.70 (0.53–0.92); and ejection fraction ≥65%: 1.05 (0.70–1.58). Other heart failure outcomes and measures, including KCCQ, showed a similar response pattern. Sex did not influence the responses to empagliflozin.

Conclusion

The magnitude of the effect of empagliflozin on heart failure outcomes was clinically meaningful and similar in patients with ejection fractions <25% to <65%, but was attenuated in patients with an ejection fraction ≥65%.

Key Question

How does ejection fraction influence the effects of empagliflozin in patients with heart failure and either a reduced or a preserved ejection fraction?

Key Finding

The magnitude of the effect of empagliflozin on heart failure outcomes and health status was similar in patients with ejection fractions <25% to <65%, but it was attenuated in patients with an ejection fraction ≥65%.

Take Home Message

The consistency of the response in patients with ejection fractions of <25% to <65% distinguishes the effects of empagliflozin from other drugs that have been evaluated across the full spectrum of ejection fractions in patients with heart failure.

Keywords: Heart failure, Ejection fraction, Empagliflozin, Sex, Hospitalization

Graphical Abstract

See the editorial comment for this article ‘Re-emergence of heart failure with a normal ejection fraction?’, by Toru Kondo and John J.V. McMurray, https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehab828.

Introduction

Heart failure has traditionally been categorized into two phenotypes based on the measurement of ejection fraction. Patients with an ejection fraction of 40% or less typically have heart failure due to loss of cardiomyocytes, which is accompanied by meaningful left ventricular dilatation and a biomarker profile that reflects cardiomyocyte injury and stretch.1 , 2 In contrast, patients with an ejection fraction >40% have heart failure that is accompanied by comorbidities (such as obesity) that do not lead to marked ventricular enlargement and are accompanied by a biomarker profile that reflects inflammation and fibrosis.1 , 2 Patients with an ejection fraction of 40% or less are commonly men, whereas those with an ejection fraction >40% are commonly women. Although patients with an ejection fraction of 40–50% are often referred to as having mid-range ejection fraction, these patients resemble those with a reduced ejection fraction with respect to their therapeutic responses.3

Large-scale clinical trials have shown that several neurohormonal antagonists can reduce the risk of cardiovascular death and hospitalization for heart failure in patients with an ejection fraction of 40% or less, but these drugs have not been consistently effective in patients with an ejection fraction >50%, although there has been considerably heterogeneity in the reported effect sizes based on ejection fraction.4–9 Beta-blockers, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists, and angiotensin receptor–neprilysin inhibitors appear to reduce the risk of heart failure hospitalizations in patients with an ejection fraction of 40–49%, but the magnitude of the benefits of all three drug classes is meaningfully reduced in patients with an ejection fraction of 50% or greater.3 , 10–12 In some analyses, a modest treatment effect with mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists and neprilysin inhibitors has been reported in patients with an ejection fraction of 50–55%, but only in women, and not in men.13 , 14

Sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors prevent heart failure hospitalization in high-risk patients with diabetes mellitus who largely did not have heart failure,15 and dapagliflozin and empagliflozin have been shown to reduce the risk of cardiovascular death or heart failure hospitalizations in patients with established heart failure who have an ejection fraction of 40% or less.16 , 17 Sotagliflozin was reported to reduce the risk of heart failure hospitalization in small subgroups of diabetic patients with heart failure who had an ejection fraction of 50% or greater.18 , 19 Empagliflozin has recently been shown to reduce the risk of cardiovascular death or heart failure hospitalizations in patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction in a large-scale definitively-powered trial.20 Yet, it is unclear whether the pattern of an attenuated response seen with many neurohormonal antagonists in patients with an ejection fraction >50% applies to sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors. To address this issue, we evaluated the magnitude of the effect of empagliflozin on heart failure hospitalizations across the full range of left ventricular ejection fractions by pooling the individual patient-level data from the EMPEROR-Reduced (Empagliflozin Outcomes Trial in Heart Failure and a Reduced Ejection Fraction) and EMPEROR-Preserved (Empagliflozin Outcomes Trial in Heart Failure and a Preserved Ejection Fraction) trials.

Methods

The EMPEROR-Reduced and the EMPEROR-Preserved trials were multicentre, randomized, double-blind, parallel-group, placebo-controlled trials that evaluated the efficacy of empagliflozin on outcomes in patients with heart failure.21 , 22 Both trials were carried out by a similar group of investigators using similar eligibility criteria and similar case report forms. Both trials were designed and overseen by the same Executive Committee; events were adjudicated by the same Endpoint Adjudication Committee; and the trials were overseen by the same independent Data Monitoring Committee. The primary difference between the two trials was the inclusion of patients with an ejection fraction of 40% or less in EMPEROR-Reduced and > 40% in EMPEROR-Preserved. The first two authors who had unrestricted access to the data prepared the first draft of the manuscript and edited it after review and input from all authors. The authors made the decision to submit the manuscript for publication and assume full responsibility for the accuracy and completeness of the analyses.

Patient population

The study designs for both trials have been described in detail previously. In brief, participants were men or women, aged 18 years or older, with New York Heart Association functional class II–IV symptoms for at least 3 months. The eligibility values for N-terminal prohormone B-type natriuretic peptide varied with the ejection fraction (i.e. >300 pg/mL if the ejection fraction was >40%; ≥600 pg/mL if the ejection fraction was ≤30% or if patients had been hospitalized for heart failure within 12 months; ≥1000 pg/mL if the ejection fraction was 31–35%; and ≥2500 pg/mL if the ejection fraction was 36–40%). In patients with atrial fibrillation, these thresholds were doubled in EMPEROR-Reduced and tripled in EMPEROR-Preserved. The exclusion criteria in both trials were similar.

In both trials, patients were randomized double‐blind in a 1:1 ratio to receive either placebo or empagliflozin 10 mg daily, in addition to their usual therapy for heart failure. Randomization was stratified by geographical region, diabetes status, and estimated glomerular filtration rate (<60 or ≥60 mL/min/1.73 m2). Ejection fraction <50% or ≥50% was an additional stratification variable in EMPEROR-Preserved. Following randomization, patients were evaluated at planned study visits, which occurred at the same time points in the two trials. All randomized patients were followed for the occurrence of primary and secondary heart failure outcomes for the entire duration of each trial, whether or not patients continued to take their study medication. The pre-specified subgroups analyses were ≤30% and 31–40% in EMPEROR-Reduced and 41–49%, 50–59%, and ≥60% in EMPEROR-Preserved. However, in the current paper, patients were divided (post hoc) based on their ejection fraction into six groups—<25%, 25–34%, 35–44%, 45–54%, 55–64%, and ≥65%—in order to permit a more granular analysis of the influence of the effect of empagliflozin on heart failure outcomes.

Outcomes

Five heart failure outcomes were prospectively assessed: (i) the primary endpoint of time to heart failure hospitalization or cardiovascular death; (ii) time to first heart failure hospitalization and (iii) time to cardiovascular death (the components of the primary endpoint); (iv) total (first and recurrent) heart failure hospitalization (the first secondary endpoint); and (v) the change in Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire clinical summary score (KCCQ-CSS) at 52 weeks.

Statistical analysis

Baseline patient characteristics and differences among them were assessed using descriptive statistics. Continuous data are presented as mean (standard deviation) or median (interquartile range). Time-to-event analyses were performed using Cox proportional hazards models controlling for age, sex, estimated glomerular filtration rate, region, and diabetes status. Total (first and recurrent) heart failure hospitalizations were evaluated using the joint frailty model, where it was modelled together with cardiovascular death as a competing risk, adjusting for the same covariates as the Cox model. Hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals were calculated for the effect of empagliflozin vs. placebo on the primary and secondary heart failure outcomes in each of the six subgroups: <25%, 25–34%, 35–44%, 45–54%, 55–64%, and ≥65%. We also evaluated the effect of pre-treatment ejection fraction (as a continuous variable) on the effects of empagliflozin assuming a linear relationship or using cubic splines, including trial and the same covariates noted above. For implementation of continuous models for recurrent events (linear and splines), a negative binomial model was used. Changes in KCCQ at 52 weeks were analysed by mixed repeated-measures model that included age and baseline estimated glomerular filtration rate as linear covariates and baseline KCCQ-CSS by visit, visit by treatment, sex, region, individual last projected visit based on dates of randomization and trial closure, and baseline diabetes status as fixed effects.23 All P-values are two-sided, and all statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4.

Results

Between April 2017 and April 2020, 9718 patients with heart failure were randomized to placebo or empagliflozin in the EMPEROR-Reduced (n = 3730) and EMPEROR-Preserved (n = 5988) trials. Approximately half of the patients had a history of diabetes, and half had an estimated glomerular filtration rate <60 mL/min/1.73 m2. A total of 57 patients (0.6%) had unknown vital status at the end of the two trials (29 in the placebo group and 28 in the empagliflozin group). The median duration of follow-up was 21 months.

Baseline patient characteristics

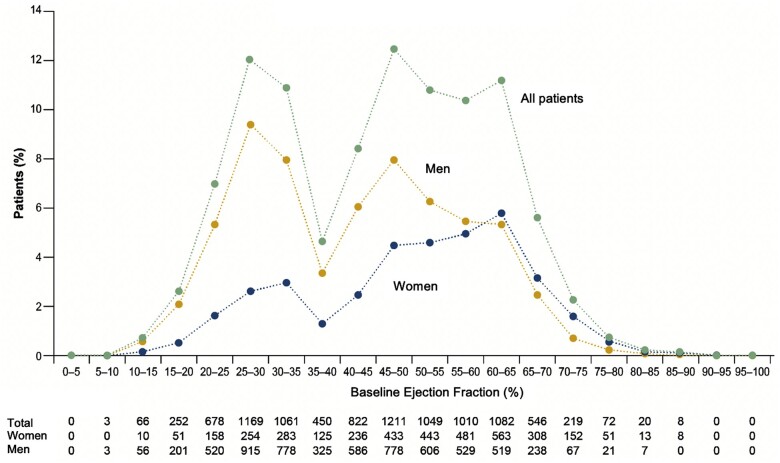

A total of 9718 patients (4860 empagliflozin; 4858 placebo) were divided into six groups based on ejection fraction: <25% (n = 999), 25–34% (n = 2230), 35–44% (n = 1272), 45–54% (n = 2260), 55–64% (n = 2092), and ≥65% (n = 865) (Table 1 and Figure 1). With increasing left ventricular ejection fraction, patients were more likely to be older and female and to have impaired renal function and lower levels of natriuretic peptides, a lower prevalence of ischaemic heart disease but a higher prevalence of atrial fibrillation, and a lower utilization of inhibitors of the renin–angiotensin system, beta-blockers, and mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics, by ejection fraction

| Characteristics | Left ventricular ejection fraction |

P-values | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <25% (n = 999) | 25–34% (n = 2230) | 35–44% (n = 1272) | 45–54% (n = 2260) | 55–64% (n = 2092) | ≥65% (n = 865) | ||

| Age, years, mean ± SD | 65 ± 11 | 67 ± 11 | 69 ± 10 | 71 ± 9 | 73 ± 9 | 74 ± 9 | <0.001 |

| Women, n (%) | 219 (22) | 537 (24) | 361 (28) | 876 (39) | 1044 (50) | 532 (62) | <0.001 |

| Race, n (%) | |||||||

| American Indian/Alaskan Native | 16 (2) | 18 (1) | 42 (3) | 89 (4) | 50 (2) | 18 (2) | <0.001 |

| Asian | 181 (18) | 382 (17) | 210 (17) | 251 (11) | 297 (14) | 175 (20) | |

| Black | 85 (9) | 140 (6) | 74 (6) | 101 (4) | 78 (4) | 37 (4) | |

| White | 676 (68) | 1610 (72) | 906 (71) | 1750 (77) | 1620 (77) | 609 (70) | |

| Other/mixed | 25 (3) | 46 (2) | 32 (3) | 69 (3) | 45 (2) | 26 (3) | |

| Missing | 16 (2) | 34 (2) | 8 (1) | 0 | 2 (0.1) | 0 | |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |||||||

| Not Hispanic/Latino | 635 (64) | 1380 (62) | 832 (65) | 1711 (76) | 1615 (77) | 632 (73) | <0.001 |

| Hispanic/Latino | 327 (33) | 753 (34) | 415 (33) | 549 (24) | 476 (23) | 233 (27) | |

| Missing | 37 (4) | 97 (4) | 25 (2) | 0 | 1 (<0.1) | 0 | |

| Geographical regions | |||||||

| North America | 140 (14) | 219 (10) | 111 (9) | 224 (10) | 329 (16) | 121 (14) | <0.001 |

| Latin America | 337 (34) | 797 (36) | 433 (34) | 558 (25) | 462 (22) | 214 (25) | |

| Europe | 347 (35) | 835 (37) | 486 (38) | 1145 (51) | 921 (44) | 308 (36) | |

| Asia | 133 (13) | 271 (12) | 169 (13) | 190 (8) | 254 (12) | 162 (19) | |

| Other | 42 (4) | 108 (5) | 73 (6) | 143 (6) | 126 (6) | 60 (7) | |

| NYHA class II, n (%) | 695 (70) | 1714 (77) | 1024 (81) | 1841 (81) | 1714 (82) | 695 (80) | <0.001 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 27.7 ± 5.4 | 28.0 ± 5.4 | 28.5 ± 5.5 | 29.8 ± 5.7 | 30.2 ± 6.0 | 29.9 ± 6.2 | <0.001 |

| Heart rate, b.p.m. | 73 ± 11 | 71 ± 12 | 71 ± 12 | 71 ± 12 | 70 ± 12 | 70 ± 12 | <0.001 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 118 ± 14 | 123 ± 16 | 128 ± 16 | 132 ± 16 | 133 ± 16 | 132 ± 16 | <0.001 |

| NT-proBNP, pg/mL, median (IQR) | 2144 (1255– 4046) | 1726 (1027– 3144) | 1465 (743– 2813) | 993 (523– 1772) | 967 (480– 1689) | 885 (466– 1607) | <0.001 |

| Ischaemic aetiology, n (%) | 491 (49) | 1186 (53) | 663 (52) | 980 (43) | 568 (27) | 158 (18) | <0.001 |

| Hospitalization for heart failure within 12 months, n (%) | 344 (34) | 594 (27) | 408 (32) | 540 (24) | 464 (22) | 170 (20) | <0.001 |

| Atrial fibrillation, n (%) | 364 (36) | 802 (36) | 504 (40) | 1133 (50) | 1179 (56) | 444 (51) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 509 (51) | 1095 (49) | 645 (51) | 1165 (52) | 988 (47) | 392 (45) | 0.019 |

| eGFR, mL/min/1.73 m2, mean ± SD | 63 ± 22 | 62 ± 22 | 62 ± 21 | 62 ± 20 | 59 ± 20 | 59 ± 19 | <0.001 |

| eGFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m2, n (%) | 458 (46) | 1069 (48) | 616 (48) | 1087 (48) | 1099 (53) | 458 (53) | <0.001 |

| Heart failure medications, n (%) | |||||||

| Renin–angiotensin system inhibitor | 900 (90) | 1971 (88) | 1089 (86) | 1895 (84) | 1609 (77) | 661 (76) | <0.001 |

| Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist | 767 (77) | 1579 (71) | 711 (56) | 922 (41) | 662 (32) | 264 (31) | <0.001 |

| Beta-blocker | 934 (93) | 2119 (95) | 1184 (93) | 2009 (89) | 1751 (84) | 703 (81) | <0.001 |

| Diuretics (other than MRA) | 891 (89) | 1922 (86) | 1049 (82) | 1800 (80) | 1719 (82) | 676 (78) | <0.001 |

eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; IQR, interquartile range; NT-proBNP, N-terminal prohormone B-type natriuretic peptide; NYHA, New York Heart Association; SD, standard deviation.

Figure 1.

Distribution of left ventricular ejection fraction in the pooled analysis. Shown are the distributions overall, and separately, in men and women. The distribution reflects decision to limit the recruitment of patients with ejection fraction of 31–40%.

Left ventricular ejection fraction and outcomes in the placebo group

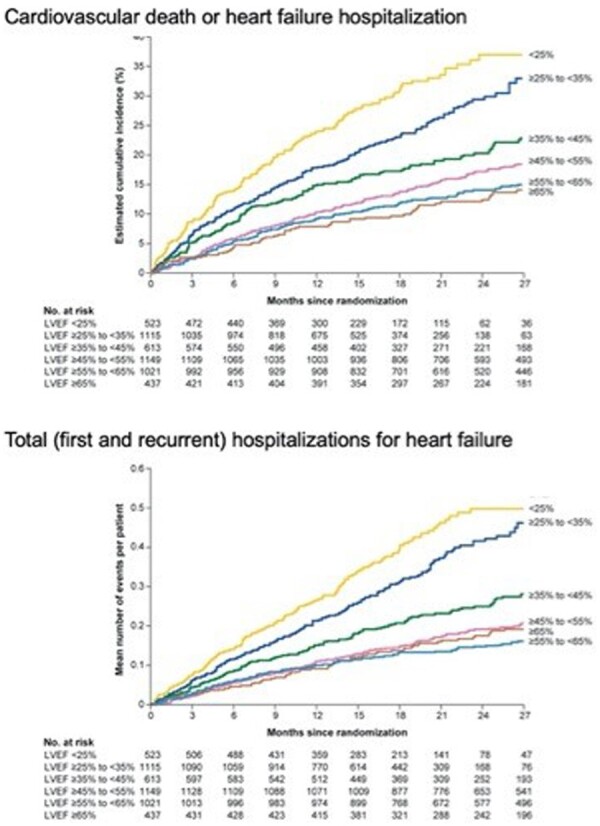

Table 2 shows the total number and proportion of events and incidence rates for the three major heart failure outcomes across the six ejection fraction subgroups in patients treated with placebo. The incidence of the primary endpoint (cardiovascular death or hospitalization for heart failure) and the rate of total (first and recurrent) hospitalizations for heart failure progressively decreased as ejection fraction increased (P-trend <0.001 for all outcomes) (Figure 2).

Table 2.

Incidence rates for major outcomes in the placebo arm, by ejection fraction

| Left ventricular ejection fraction |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <25% (n = 523) | 25–34% (n = 1115) | 35–44% (n = 613) | 45–54% (n = 1149) | 55–64% (n = 1021) | ≥65 (n = 437) | P-values for trend | |

| Heart failure hospitalization or cardiovascular death | |||||||

| Patients with events, n (%) | 154 (29.4) | 255 (22.9) | 128 (20.9) | 215 (18.7) | 161 (15.8) | 60 (13.7) | |

| Incidence rate (95% CI) | 25.3 (21.5–29.5) | 19.1 (16.9–21.5) | 12.8 (10.7–15.1) | 9.5 (8.3–10.8) | 8.0 (6.8–9.2) | 7.0 (5.4–8.9) | |

| Hazard ratio (95% CI) | Referent | 0.75 (0.61–0.91) | 0.54 (0.42–0.68) | 0.42 (0.34–0.52) | 0.34 (0.27–0.42) | 0.29 (0.21–0.39) | <0.001 |

| First heart failure hospitalization | |||||||

| Patients with events, n (%) | 113 (21.6) | 192 (17.2) | 87 (14.2) | 139 (12.1) | 118 (11.6) | 45 (10.3) | |

| Incidence rate (95% CI) | 18.6 (15.3–22.2) | 14.4 (12.4–16.5) | 8.7 (7.0–10.6) | 6.1 (5.2–7.2) | 5.8 (4.8–6.9) | 5.3 (3.9–6.9) | |

| Hazard ratio (95% CI) | Referent | 0.77 (0.61–0.97) | 0.53 (0.40–0.71) | 0.40 (0.31–0.52) | 0.36 (0.28–0.47) | 0.31 (0.22–0.45) | <0.001 |

| Total (first and recurrent) heart failure hospitalizations | |||||||

| Total hospitalizations, n | 179 | 313 | 143 | 218 | 161 | 80 | |

| Hazard ratio (95% CI) | Referent | 0.75 (0.56–1.01) | 0.49 (0.35–0.69) | 0.36 (0.26–0.49) | 0.26 (0.18–0.36) | 0.29 (0.19–0.43) | <0.001 |

CI, confidence interval.

Figure 2.

Cumulative incidence curves for time to cardiovascular death or heart failure hospitalization (top panel) and recurrent heart failure hospitalization (bottom panel) in the placebo group, according to ejection fraction subgroup. Shown are subgroups based on ejection fractions of <25%, 25–34%, 35–44%, 45–54%, 55–64%, and 65% or greater. There was an inverse relationship between baseline ejection fraction and the risk for serious heart failure outcomes.

Empagliflozin and heart failure outcomes according to ejection fraction and sex

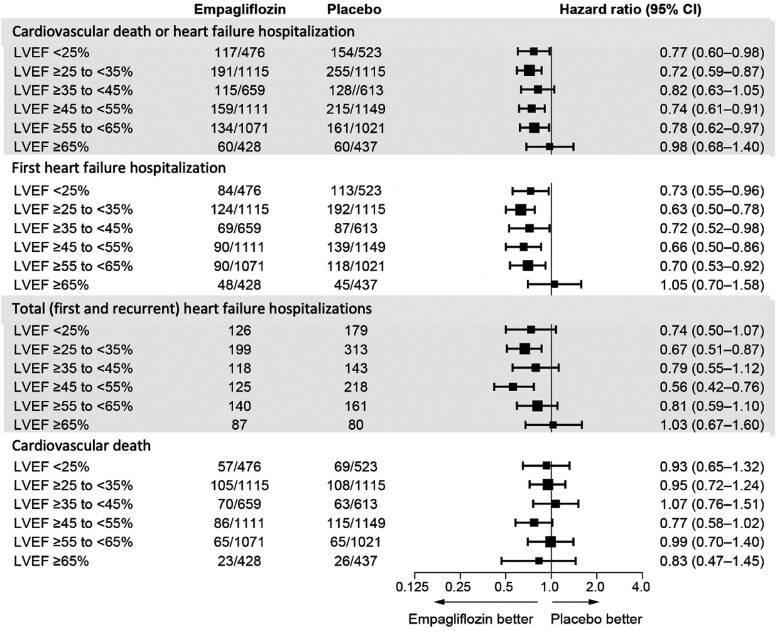

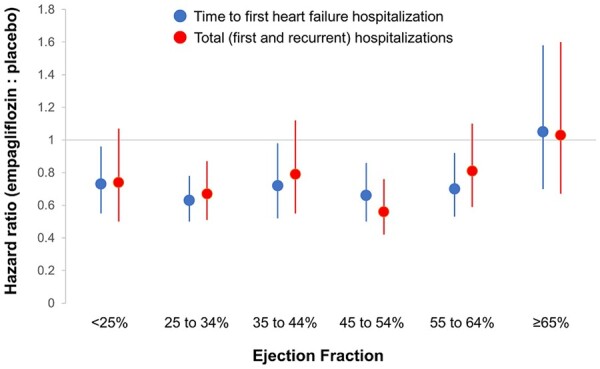

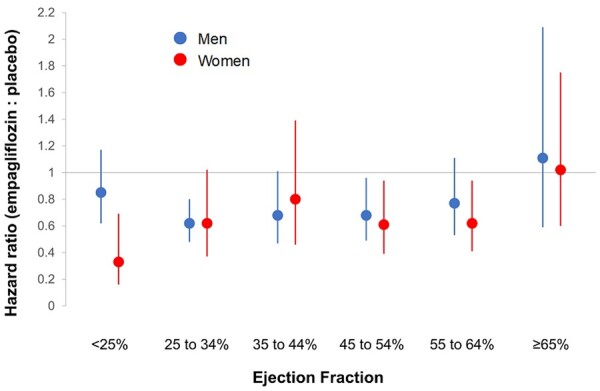

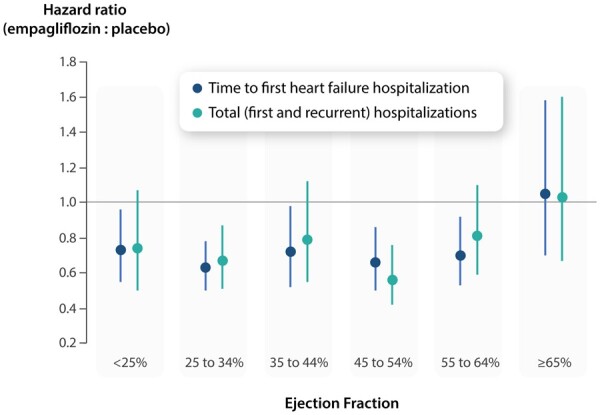

Empagliflozin reduced the risk of heart failure hospitalization or cardiovascular death primarily by an effect on heart failure hospitalization.19 Empagliflozin reduced the risk of a first heart failure hospitalization to a similar degree (∼25–35%) in the patients in each of the ejection fraction subgroups, with an attenuated response in patients with ejection fraction ≥65%; hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals: ejection fraction <25%: 0.73 (0.55–0.96); ejection fraction 25–34%: 0.63 (0.50–0.78); ejection fraction 35–44%: 0.72 (0.52–0.98); ejection fraction 45–54%: 0.66 (0.50–0.86); ejection fraction 55–64%: 0.70 (0.53–0.92); and ejection fraction ≥65%: 1.05 (0.70–1.58) (Figures 3 and 4 and Table 3). A similar pattern of effects was seen for other outcomes that included the occurrence of hospitalization for heart failure and when ejection fraction subgroups were defined by mid-range values not ending in a ‘0’ or ‘5’ (to minimize measurement reporting bias commonly seen in clinical practice) (see Supplementary material online, Table S1). When compared with placebo, the effect of empagliflozin on KCCQ scores at 52 weeks ranged from 1.5 to 3.0 for most subgroups from ejection fractions <25% to 55–64%, but was 0.26 in patients with an ejection fraction ≥65%. Among patients with an ejection fraction ≥25%, the pattern of influence of ejection fraction on the effects of empagliflozin on heart failure outcomes were similar in men and women (Figure 5 and Table 4).

Figure 3.

Effect of empagliflozin on heart failure outcomes in six ejection fraction subgroups. Shown are hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals for four major cardiovascular outcomes in six ejection fraction subgroups. For all outcomes except for total heart failure hospitalizations, the numbers indicate patients with an event in the numerator and patients at risk in the denominator. For total (first and recurrent heart failure hospitalizations), the numbers indicate the total number of events. LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction.

Figure 4.

Effect of empagliflozin on heart failure hospitalizations in six ejection fraction subgroups. Shown are hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals for the effect on time to first heart failure hospitalization (in blue) and total heart failure hospitalizations (in red).

Table 3.

Efficacy of empagliflozin on heart failure outcomes and health status, by ejection fraction

| Left ventricular ejection fraction |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <25% |

25–34% |

35–44% |

45–54% |

55–64% |

≥65 |

|||||||

| Placebo (n = 523) | Empa (n = 476) | Placebo (n = 1115) | Empa (n = 1115) | Placebo (n = 613) | Empa (n = 659) | Placebo (n = 1149) | Empa (n = 1111) | Placebo (n = 1021) | Empa (n = 1071) | Placebo (n = 437) | Empa (n = 428) | |

| Heart failure hospitalization or cardiovascular death | 0.77 (0.60–0.98) | 0.72 (0.59–0.87) | 0.82 (0.63–1.05) | 0.74 (0.61–0.91) | 0.78 (0.62–0.97) | 0.98 (0.68–1.40) | ||||||

| First heart failure hospitalization | 0.73 (0.55–0.96) | 0.63 (0.50–0.78) | 0.72 (0.52–0.98) | 0.66 (0.50–0.86) | 0.70 (0.53–0.92) | 1.05 (0.70–1.58) | ||||||

| Total heart failure hospitalizations | 0.74 (0.50–1.07) | 0.67 (0.51–0.87) | 0.79 (0.55–1.12) | 0.56 (0.42–0.76) | 0.81 (0.59–1.10) | 1.03 (0.67–1.60) | ||||||

| KCCQ clinical summary score at 52 weeks | 3.01 (0.68–5.33) | 0.92 (–0.62 to 2.46) | 1.82 (–0.16 to 3.81) | 1.59 (0.16–3.01) | 1.95 (0.48–3.41) | 0.26 (–2.01 to 2.52) | ||||||

The number of patients with available KCCQ scores at baseline and at 52 weeks in the placebo and empagliflozin groups, respectively, are as follows: ejection fraction <25% (338, 319), ejection fraction 25–34% (743, 744), ejection fraction 35–44% (444, 482), ejection fraction 46–54% (928, 906), ejection fraction 55–64% (854, 898), and ejection fraction ≥65% (368, 363). For all variables, the data shown are hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals; however, for the KCCQ scores, the data represent absolute differences and 95% confidence intervals.

Empa, empagliflozin; KCCQ, Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire.

Figure 5.

Effect of empagliflozin on time to first heart failure hospitalization in six ejection fraction subgroups, according to sex. Shown are hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals for the effect in men (in blue) and in women (in red).

Table 4.

Efficacy of empagliflozin on heart failure outcomes, by ejection fraction and sex

| Left ventricular ejection fraction |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <25% |

25–34% |

35–44% |

45–54% |

55–64% |

≥65 |

|||||||

| Placebo (n = 124) | Empa (n = 95) | Placebo (n = 271) | Empa (n = 266) | Placebo (n = 174) | Empa (n = 187) | Placebo (n = 452) | Empa (n = 424) | Placebo (n = 497) | Empa (n = 547) | Placebo (n = 276) | Empa (n = 256) | |

| Women | ||||||||||||

| Heart failure hospitalization or cardiovascular death | 0.39 (0.21–0.71) | 0.63 (0.41–0.97) | 0.76 (0.48–1.20) | 0.73 (0.52–1.02) | 0.78 (0.55–1.09) | 0.85 (0.53–1.37) | ||||||

| First heart failure hospitalization | 0.33 (0.16–0.69) | 0.62 (0.37–1.02) | 0.80 (0.46–1.39) | 0.61 (0.39–0.94) | 0.62 (0.41–0.94) | 1.02 (0.60–1.75) | ||||||

| Total heart failure hospitalizations | 0.49 (0.22–1.11) | 0.70 (0.40–1.24) | 0.98 (0.49–1.95) | 0.53 (0.32–0.86) | 0.70 (0.44–1.11) | 0.89 (0.50–1.59) | ||||||

| Placebo (n=399) | Empa (n=381) | Placebo (n=844) | Empa (n=849) | Placebo (n=439) | Empa (n=472) | Placebo (n=697) | Empa (n=687) | Placebo (n=524) | Empa (n=524) | Placebo (n=161) | Empa (n=172) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | ||||||||||||

| Heart failure hospitalization or cardiovascular death | 0.90 (0.69–1.18) | 0.74 (0.60–0.91) | 0.85 (0.63–1.15) | 0.75 (0.58–0.98) | 0.78 (0.57–1.06) | 1.19 (0.69–2.06) | ||||||

| First heart failure hospitalization | 0.85 (0.62–1.17) | 0.62 (0.48–0.80) | 0.68 (0.47–1.01) | 0.68 (0.49–0.96) | 0.77 (0.53–1.11) | 1.11 (0.59–2.09) | ||||||

| Total heart failure hospitalizations | 0.85 (0.56–1.30) | 0.65 (0.48–0.89) | 0.72 (0.47–1.10) | 0.59 (0.41–0.86) | 0.92 (0.60–1.40) | 1.26 (0.64–2.48) | ||||||

The data shown are hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals.

Empa, empagliflozin.

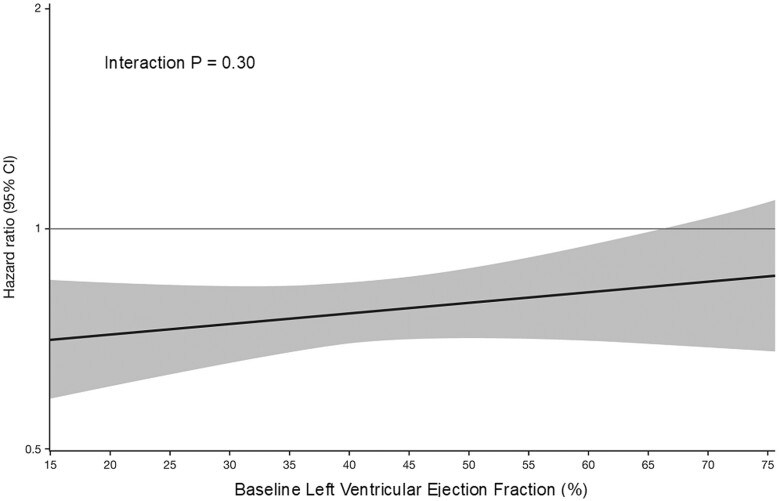

Analyses of the influence of ejection fraction on the effect of empagliflozin, assessed as a continuous variable and assuming a linear relationship, showed no significant influence on the effect of the drug for the primary endpoint, the first secondary endpoint, or on cardiovascular death (Figure 6 and Supplementary material online, Figures S1 and S2). When analysed by cubic splines, the influence of ejection fraction on heart failure outcomes mirrored the pattern seen in the analysis of subgroups, with an attenuated response at higher ejection fractions (see Supplementary material online, Figures S3–S5).

Figure 6.

Influence of ejection fraction on the effect of empagliflozin on time to cardiovascular death or hospitalization for heart failure. Ejection fraction is analysed as a continuous variable, based on the assumption that the relationship is linear. Analysis of the influence of ejection fraction using cubic splines yielded a pattern similar to that observed in our six subgroups, showing a consistent risk reduction in patients with an ejection fraction <65% and an attenuated effect at the highest ejection fractions (see Supplementary material online, Figures S3–S5). Shaded areas represent 95% confidence intervals.

Discussion

In this pooled analysis of the EMPEROR-Preserved and EMPEROR-Reduced trials involving 9718 patients with heart failure, we found that empagliflozin reduced the risk of heart failure hospitalizations across a broad range of ejection fractions. Specifically, empagliflozin reduced both the time to first hospitalizations for heart failure and the total (first and recurrent) hospitalizations for heart failure to a similar degree (by 25–35%) in patients with ejection fractions ranging from <25% to <65%. A benefit of empagliflozin was not apparent only in patients in the highest ejection fraction subgroup, i.e. those with an ejection fraction of ≥65% (Graphical Abstract). The pattern of effects was similar in men and women. Examination of the effects of empagliflozin on health status by the KCCQ-CSS showed a pattern of the influence of ejection fraction that was strikingly consistent with the pattern of the influence of ejection fraction on the effect of the drug on heart failure outcomes.

Structured Graphical Abstract.

Influence of ejection fraction on the magnitude of the effect of empagliflozin on heart failure outcomes.

These findings should be considered in the context of the reported results with neurohormonal antagonists. In trials with candesartan (an angiotensin receptor blocker), spironolactone (a mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist), and sacubitril/valsartan (an angiotensin receptor–neprilysin inhibitor), investigators have reported a linear relationship between ejection fraction and the magnitude of the treatment effect.10–12 For each of these drugs, the most marked risk reduction was seen in patients with an ejection fraction of 30% or less; an intermediate risk reduction was seen in patients with an ejection fraction >30% to <50%; and there was minimal or no risk reduction in patients with an ejection fraction >50–55%. In contrast to these findings, ejection fraction did not influence the magnitude of the response to empagliflozin in most patients with heart failure, with a similar relative risk reduction for hospitalizations for heart failure in patients with an ejection fraction <30%, 40–50%, or >50 to <65%. Furthermore, whereas sex has been reported to influence the response to spironolactone and sacubitril/valsartan,13 , 14 the response to empagliflozin in the EMPEROR-Reduced and EMPEROR-Preserved trials did not differ between men and women, and we did not observe a significant treatment-by-sex-by ejection fraction interaction.

It should be noted that we were able to discern a pattern of a consistent effect of empagliflozin in most patients coupled with an attenuated response on heart failure hospitalization at the highest ejection fraction only when we performed a post hoc analysis that was more granular than the approach we had originally planned. Our finding of an attenuated response in patients with an ejection fraction of 65% or greater is supported not only by the pattern of the effects of empagliflozin on heart failure outcomes but also by the pattern of the effects of the drug on health status as assessed by KCCQ-CSS. Furthermore, our observations are consistent with the finding of an attenuated response on total hospitalizations for heart failure in patients with an ejection fraction ≥60% when our analysis was carried out according to pre-specified subgroups.24 We would not have been able to discern these subgroup effects if we had relied only on the assessment of ejection fraction as a continuous variable and if we had calculated P-values assuming linearity. We did not observe a significant linear relationship between ejection fraction and the effect of empagliflozin on our primary endpoint, whether the analysis was focused on the patients in EMPEROR-Preserved (P = 0.43), or on the patients in the entire pooled analysis (P = 0.30) (Figure 6 and Supplementary material online, Figures S1 and S2).8 However, any assessment of the relationship between ejection fraction as a continuous variable that is predicated on linearity is based on potentially unwarranted assumptions about the shape of the relationship between ejection fraction and empagliflozin response, and these approaches are often unable to discern meaningful and valid outlier responses in a small subgroup. Analysis of the influence of ejection fraction using cubic splines yielded a pattern similar to that observed in our six subgroups, showing a consistent risk reduction in patients with an ejection fraction <65% and an attenuated effect at the highest ejection fractions (see Supplementary material online, Figures S3–S5).

Although we did not identify a significant linear relationship between ejection fraction and the effect of empagliflozin on our primary endpoint, it should be noted that the PARAGON-HF investigators readily discerned a linear relationship between ejection fraction and the effect of neprilysin inhibition on the primary endpoint of the study,9 with a significant stepwise decrement in the response to sacubitril/valsartan as ejection fraction increased. This significant stepwise decrement was observed whether the analysis was confined only to patients with a preserved ejection fraction or when the analysis included the full spectrum of ejection fractions in patients with heart failure.12 , 25 , 26 As shown in the current analysis, this stepwise decrement in effect size (particularly among patients with ejection fractions of 45–65%) was not observed in the EMPEROR-Preserved trial, thus explaining why the influence of ejection fraction on the primary endpoint was significant in PARAGON-HF but not in EMPEROR-Preserved.

The current analysis should be distinguished from an analysis that we recently performed to compare the effect of empagliflozin in the EMPEROR-Preserved trial to the effect of sacubitril/valsartan in the PARAGON-HF trial.27 To carry out a fair and unbiased side-by-side examination, we re-analysed the treatment effects on heart failure outcomes in the EMPEROR-Preserved trial using ejection fraction cut-points of 42.5%, 52.5%, and 62.5% because the PARAGON-HF investigators had utilized these subgroups, and we specifically sought to have our analyses conform to theirs. We noted that the effect of both sacubitril/valsartan and empagliflozin became attenuated at ejection fraction > 62.5%, but the effect size of empagliflozin was larger than that of sacubitril/valsartan in patients with an ejection fraction from 42.5 to 62.5%. The analyses reported in the current paper were not carried out to achieve a comparative analysis in a focused group of patients but were performed to characterize the influence of ejection fraction on the response to empagliflozin across the entire spectrum with a reduced and preserved ejection fraction.

Our finding of an attenuated effect of empagliflozin on heart failure outcomes in patients with an ejection fraction of 65% and greater requires further study. This subgroup represented <10% of the entire patient population and the total number of events. As a result, our estimates for this subgroup are necessarily imprecise, and additional studies in this subgroup are needed to clarify the true effect of empagliflozin. Nevertheless, our data suggest that this subgroup has a high prevalence of atrial fibrillation and low levels of natriuretic peptides, levels that were only modestly higher than the thresholds that we specified for inclusion in the two trials, which were predicated on the fact that natriuretic peptides are increased in patients with atrial fibrillation in the absence of heart failure. Additionally, our data indicate that this subgroup represented a group of predominantly elderly hypertensive women who had a low incidence of hospitalizations for heart failure during the course of follow-up. All these features are strikingly similar to those reported by Solomon et al. in patients with an ejection fraction > 62.5% in the PARAGON-HF trial.12 These observations raise the possibility that many of the patients in the subgroup with an ejection fraction of 65% or greater may have had symptoms of dyspnoea that were less related to heart failure but more attributable to an atrial arrhythmia or other conditions that are common in elderly women. Wehner et al. have recently reported that patients with heart failure and an ejection fraction of 65% or greater represent an unusual subgroup.28

Our findings should be interpreted in light of certain strengths and limitations. We performed an individual patient-level pooled analyses of two trials with the same drug that were designed and executed in a nearly identical manner, except for the inclusion criteria for ejection fraction. However, the assessment of ejection fraction is subject to considerable measurement variability, particularly since measurements were performed locally by investigative sites and not in a central core laboratory. Furthermore, since reports in other trials had noted an attenuated treatment effect at ejection fraction thresholds of 50%, 55%, or 60%, we defined our ejection fraction subgroups post hoc in order to permit a more granular analysis that had been originally planned. It should be noted that we limited the enrolment of patients with an ejection fraction of 31–40% by requiring exceptionally high natriuretic peptide thresholds for their participation. To minimize the degree to which this unrepresentative subgroup might skew our results, we defined thresholds for our analyses so that our ejection fraction subgroups would not be aligned with our enrolment criteria. Importantly, since prior investigators examined responses across the broad range of ejection fractions in subgroups separated by ejection fraction units of 10,12 we followed the same approach in the current paper. Our results were similar whether we defined ejection fraction subgroups by cut-points ending in ‘0’ or ‘5%’ or used mid-range values to minimize measurement reporting bias, and they were supported by the analysis of ejection fraction as a continuous variable using cubic splines (see Supplementary material online, Figures S3–S5).

In conclusion, our findings demonstrate an effect of empagliflozin to reduce the risk of heart failure hospitalizations in most patients with heart failure, whether their ejection fractions are ≤40% or >40%.

Funding

Funding for the EMPEROR trials was provided by Boehringer Ingelheim and Eli Lilly and Company.

Conflict of interest: J.B. reports personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, during the conduct of the study; personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, personal fees from Cardior, CVRx, Foundry, G3 Pharma, Imbria, Impulse Dynamics, Innolife, Janssen, LivaNova, Luitpold, Medtronic, Merck, Novartis, NovoNordisk, Relypsa, Roche, Sanofi, Sequana Medical, V-Wave, and Vifor, outside the submitted work. M.P. reports personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, during the conduct of the study; personal fees from AbbVie, Actavis, Amgen, Amarin, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, Casana, CSL Behring, Cytokinetics, Johnson & Johnson, Eli Lily & Company, Moderna, Novartis, ParatusRx, Pfizer, Relypsa, Salamandra, Synthetic Biologics, and Theravance, outside the submitted work. G.F. reports personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, during the conduct of the study; personal fees from Medtronic, Vifor, Servier, Novartis, Bayer, Amgen, and Boehringer Ingelheim, outside the submitted work. J.P.F. reports personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, during the conduct of the study; personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, outside the submitted work. C.Z., J.S., and M.B. are employees of Boehringer Ingelheim. S.J.P. reports personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, during the conduct of the study; personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, outside the submitted work. F.Z. reports personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, during the conduct of the study; personal fees from Janssen, Novartis, Boston Scientific, Amgen, CVRx, AstraZeneca, Vifor Fresenius, Cardior, Cereno Pharmaceutical, Applied Therapeutics, Merck, Bayer, and Cellprothera, other support from CVCT and Cardiorenal, outside the submitted work. S.D.A. reports personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, during the conduct of the study; grants and personal fees from Abbott Vascular, Vifor, personal fees from Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Brahms GmbH, Cardiac Dimensions, Cordio, Novartis, and Servier, outside the submitted work.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Javed Butler, Department of Medicine, University of Mississippi School of Medicine, Jackson, MS, USA.

Milton Packer, Baylor Heart and Vascular Institute, 621 North Hall Street, Dallas, TX 75226, USA.

Gerasimos Filippatos, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens School of Medicine, Athens University Hospital Attikon, Chaidari, Greece.

Joao Pedro Ferreira, Université de Lorraine, Inserm INI-CRCT, CHRU, Nancy, France.

Cordula Zeller, Boehringer Ingelheim Pharma GmbH & Co. KG, Biberach, Germany.

Janet Schnee, Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Ridgefield, CT, USA.

Martina Brueckmann, Boehringer Ingelheim International GmbH, Ingelheim, Germany and Faculty of Medicine Mannheim, University of Heidelberg, Mannheim, Germany.

Stuart J Pocock, Department of Medical Statistics, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, London, UK.

Faiez Zannad, Université de Lorraine, Inserm INI-CRCT, CHRU, Nancy, France.

Stefan D Anker, Department of Cardiology (CVK), Berlin Institute of Health Center for Regenerative Therapies (BCRT), German Centre for Cardiovascular Research (DZHK) partner site Berlin, Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Berlin, Germany.

References

- 1. Tromp J, Khan MA, Klip IT et al. Biomarker profiles in heart failure patients with preserved and reduced ejection fraction. J Am Heart Assoc 2017;6:e003989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kanagala P, Arnold JR, Singh A et al. Characterizing heart failure with preserved and reduced ejection fraction: an imaging and plasma biomarker approach. PLoS One 2020;15:e0232280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Butler J, Anker SD, Packer M. Redefining heart failure with a reduced ejection fraction. JAMA 2019;322:1761–1762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Maggioni AP, Anand I, Gottlieb SO, Latini R, Tognoni G, Cohn JN; Val-HeFT Investigators (Valsartan Heart Failure Trial). Effects of valsartan on morbidity and mortality in patients with heart failure not receiving angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors. J Am Coll Cardiol 2002;40:1414–1421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Yusuf S, Pfeffer MA, Swedberg K et al. ; CHARM Investigators and Committees. Effects of candesartan in patients with chronic heart failure and preserved left-ventricular ejection fraction: the CHARM-Preserved Trial. Lancet 2003;362:777–781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pitt B, Zannad F, Remme WJ et al. The effect of spironolactone on morbidity and mortality in patients with severe heart failure. Randomized Aldactone Evaluation Study Investigators. N Engl J Med 1999;341:709–717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pitt B, Pfeffer MA, Assmann SF et al. ; TOPCAT Investigators. Spironolactone for heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. N Engl J Med 2014;370:1383–1392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. McMurray JJ, Packer M, Desai AS et al. ; PARADIGM-HF Investigators and Committees. Angiotensin-neprilysin inhibition versus enalapril in heart failure. N Engl J Med 2014;371:993–1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Solomon SD, McMurray JJV, Anand IS et al. ; PARAGON-HF Investigators and Committees. Angiotensin-neprilysin inhibition in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. N Engl J Med 2019;381:1609–1620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lund LH, Claggett B, Liu J et al. Heart failure with mid-range ejection fraction in CHARM: characteristics, outcomes and effect of candesartan across the entire ejection fraction spectrum. Eur J Heart Fail 2018;20:1230–1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Solomon SD, Claggett B, Lewis EF et al. Influence of ejection fraction on outcomes and efficacy of spironolactone in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Eur Heart J 2016;37:455–462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Solomon SD, Vaduganathan M, L Claggett B et al. Sacubitril/valsartan across the spectrum of ejection fraction in heart failure. Circulation 2020;141:352–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. McMurray JJV, Jackson AM, Lam CSP et al. Effects of sacubitril-valsartan versus valsartan in women compared with men with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction: insights from PARAGON-HF. Circulation 2020;141:338–351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Merrill M, Sweitzer NK, Lindenfeld J, Kao DP. Sex differences in outcomes and responses to spironolactone in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: a secondary analysis of TOPCAT trial. JACC Heart Fail 2019;7:228–238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. McGuire DK, Shih WJ, Cosentino F et al. Association of SGLT2 inhibitors with cardiovascular and kidney outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis. JAMA Cardiol 2021;6:148–158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. McMurray JJV, Solomon SD, Inzucchi SE et al. ; DAPA-HF Trial Committees and Investigators. Dapagliflozin in patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction. N Engl J Med 2019;381:1995–2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Packer M, Anker SD, Butler J et al. ; EMPEROR-Reduced Trial Investigators. Cardiovascular and renal outcomes with empagliflozin in heart failure. N Engl J Med 2020;383:1413–1424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bhatt DL, Szarek M, Steg PG et al. ; SOLOIST-WHF Trial Investigators. Sotagliflozin in patients with diabetes and recent worsening heart failure. N Engl J Med 2021;384:117–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bhatt DL, Szarek M, Pitt B et al. ; SCORED Investigators. Sotagliflozin in patients with diabetes and chronic kidney disease. N Engl J Med 2021;384:129–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Anker SD, Butler J, Filippatos G et al. ; EMPEROR-Preserved Trial Investigators. Empagliflozin and cardiovascular outcomes in heart failure with a preserved ejection fraction. N Engl J Med 2021;385:1451–1461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Anker SD, Butler J, Filippatos GS et al. ; EMPEROR-Preserved Trial Committees and Investigators. Evaluation of the effects of sodium–glucose co-transporter 2 inhibition with empagliflozin on morbidity and mortality in patients with chronic heart failure and a preserved ejection fraction: rationale for and design of the EMPEROR-Preserved Trial. Eur J Heart Fail 2019;21:1279–1287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Packer M, Butler J, Filippatos GS et al. ; the EMPEROR‐Reduced Trial Committees and Investigators. Evaluation of the effect of sodium–glucose co-transporter 2 inhibition with empagliflozin on morbidity and mortality of patients with chronic heart failure and a reduced ejection fraction: rationale for and design of the EMPEROR-Reduced trial. Eur J Heart Fail 2019;21:1270–1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Butler J, Anker SD, Filippatos G et al. ; the EMPEROR-Reduced Trial Committees and Investigators. Empagliflozin and health-related quality of life outcomes in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: the EMPEROR-Reduced trial. Eur Heart J 2021;42:1203–1212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Packer M, Butler J, Zannad F et al. ; for the EMPEROR-Preserved Trial Study Group. Effect of empagliflozin on worsening heart failure events in patients with heart failure and a preserved ejection fraction: the EMPEROR-Preserved trial. Circulation 2021;144:1284–1294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Dewan P, Jackson A, Lam CSP et al. Interactions between left ventricular ejection fraction, sex and effect of neurohumoral modulators in heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail 2020;22:898–901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lam CSP, Solomon SD. Classification of heart failure according to ejection fraction: JACC Review Topic of the Week. J Am Coll Cardiol 2021;77:3217–3225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Packer M, Zannad F, Anker SD. Heart failure and a preserved ejection fraction: a side-by-side examination of the PARAGON-HF and EMPEROR-Preserved trials. Circulation 2021;144:1193–1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wehner GJ, Jing L, Haggerty CM et al. Routinely reported ejection fraction and mortality in clinical practice: where does the nadir of risk lie? Eur Heart J 2020;41:1249–1257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.