Abstract

Background

Feather pecking is a serious behavioral disorder in chickens that has a considerable impact on animal welfare and poses an economic burden for poultry farming. To study the underlying genetics of feather pecking animals were divergently selected for feather pecking over 15 generations based on estimated breeding values for the behavior.

Methods and results

By characterizing the transcriptomes of whole brains isolated from high and low feather pecking chickens in response to light stimulation we discovered a putative dysregulation of micro RNA processing caused by a lack of Dicer1. This results in a prominent downregulation of the GABRB2 gene and other GABA receptor transcripts, which might cause a constant high level of excitation in the brains of high feather pecking chickens. Moreover, our results point towards an increase in immune system-related transcripts that may be caused by higher interferon concentrations due to Dicer1 downregulation.

Conclusion

Based on our results, we conclude that feather pecking in chickens and schizophrenia in humans have numerous common features. For instance, a Dicer1 dependent disruption of miRNA biogenesis and the lack of GABRB2 expression have been linked to schizophrenia pathogenesis. Furthermore, disturbed circadian rhythms and dysregulation of genes involved in the immune system are common features of both conditions.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s11033-021-07111-4.

Keywords: Feather pecking, GABA, Transcriptomics, Schizophrenia, Genome-wide association study

Introduction

Feather pecking (FP) in chickens is a damaging obsessive behavioral disorder with a genetic component [1]. Common features with obsessive compulsive disorder like involvement of immune mechanisms have been reported [2]. Furthermore, in previous studies, we identified putative enhancer RNAs that target schizophrenia-associated genes [3] as well as numerous genetic variants in genes that have been previously linked to schizophrenia, namely GABRB2, SPATS2L, ZEB2, and KCHN8 [4]. Hence, FP may be a potential model system for these conditions. A recent study reported major differences in the diurnal rhythm of gene expression between schizophrenia patients and healthy controls [5]. The study by Seney et al. revealed that healthy individuals and schizophrenia patients express two different sets of rhythmic transcripts and discovered an influence on GABAergic-related transcripts. This led us to reevaluate the brain transcriptome response of chickens divergently selected for high and low FP to light stimulation, a major trigger of FP behavior [6].

Material and methods

All experimental procedures were described in a previous study [3]. Briefly, White Leghorn strains were selected for over 15 generations based on estimated breeding values for feather pecking. Rearing and husbandry conditions have been described by Bennewitz et al. [7]. At the age of 27 weeks, 48 hens (12 full-sib pairs from each strain) were phenotyped according to established protocols. Observation of feather pecking behavior was done in 20-min sessions on four consecutive days by a minimum of six different trained observers. To prevent FP birds were kept under low light conditions. One bird from each full-sib pair kept under dark conditions was sacrificed and whole brains were immediately collected for RNA isolation. Chickens were CO2-stunned and sacrificed by ventral neck cutting. For light stimulation, the remaining birds were kept under increased light intensity (≥ 100 lx) for several hours. Upon initiation of FP behavior these birds we sacrificed as well and brains were collected for RNA isolation. For the detection of genetic variation between the two chicken lines animals were phenotyped in groups of 42 hens at the age of 32 weeks and observed in 20 min sessions by seven independent trained observers [4]. Phenotypic values were standardized to 420 min observation time followed by box-cox transformation as described by Iffland et al. [8]. Analysis pipelines of transcriptomic and genomic data are outlined in our previous studies [3, 4]. Briefly, Illumina short RNA sequencing reads were trimmed and filtered with trimmomatic, mapped to the chicken reference assembly GRCg6a with TopHat, differential expression analysis was performed with DEseq2, and gene set enrichment analysis with clusterProfiler. Variant calling from genomic data was performed according to the GATK best practice guidelines. SNP chip data were imputed with Beagle and GWAS was conducted with gcta.

Results

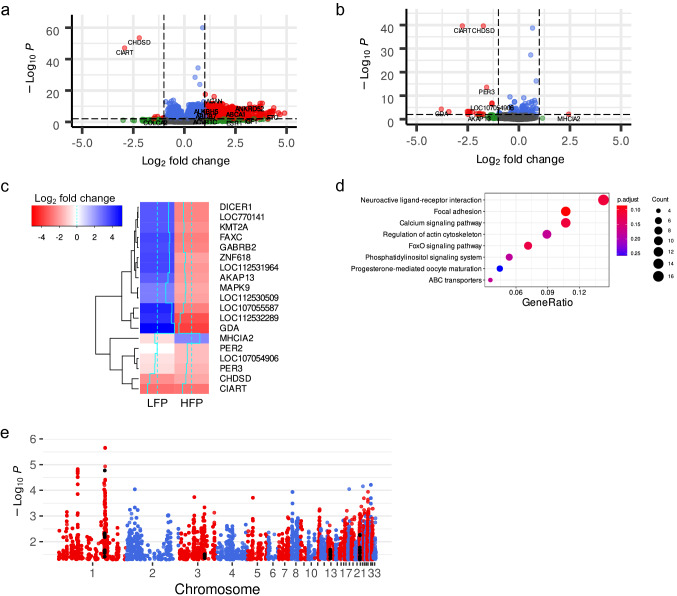

Low feather peckers (LFP) respond to light by upregulation of 714 and downregulation of 11 transcripts with 249 of these transcripts annotated as non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs). Surprisingly, high feather peckers (HFP) only show upregulation of one and downregulation of 18 transcripts (abs. log2 fold change > 1, adj. p-value < 0.01, Fig. 1a, b, Supplementary Information S1). To highlight the different directions of expression of a majority of these transcripts log2 fold changes of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) from the HFP group in comparison to the LFP group are shown in a heatmap (Fig. 1c). Significantly associated KEGG pathways after gene cluster analysis of DEGs in LFP brains in response to light compared to animals kept in the dark are shown in Fig. 1d to illustrate the loss of pathway activation in HFP (summary of results in Supplementary Information S2). Due to the low number of DEGs in HFP no gene cluster analysis could be performed. To identify genetic variation that might explain the strong difference between the two chicken lines a previously performed genome-wide association study (GWAS) [4] was repeated with a modified phenotype: feather pecks delivered box-cox transformed (Fig. 1e, Supplementary Information S3). We observed a strong peak on chromosome 1 that contains variants associated with GABRA5 and GABRG3. Furthermore, we discovered GWAS hits (p-value < 0.05) on several chromosomes in proximity to or within the genes GABRA1, GABRB2, GABRD, GABRG2, GABRG3, GABRR1, and GABRR2. The functionally most interesting variant among those is rs733309797 on chromosome 13 at position 8,186,801 (p-value = 0.044), which was predicted to be a splice region variant in the GABRB2 gene.

Fig. 1.

Volcano plots of differential gene expression in whole brains from a low feather pecking chickens and b high feather pecking chickens in response to a light stimulus. Grey dots represent transcripts that were not differentially expressed, green transcripts were above an absolute log2 fold change threshold of 1, blue transcripts were below an adjusted p-value of 0.01, and red transcripts were above an absolute log2 fold change threshold of 1 and were below an adjusted p-value of 0.01. Log2 fold change and adjusted p-values threshold are indicated by dashed lines. c Heatmap of log2 fold changes of genes differentially expressed in high feather peckers (HFP) in comparison to low feather peckers (LFP). d Gene cluster analysis results of KEGG pathways for genes differentially expressed in LFP in response to light. e Manhattan plot of GWAS hits with a p-value < 0.05 for the phenotype “feather pecks delivered cox-box transformed” performed on half-sibs convergently selected for feather pecking behavior. Variants in proximity to or located in genes coding for GABA receptors are shown in black

Discussion

HFP exhibit a surprisingly low level of excitability to the light stimulus. An overall reduced variability of gene expression levels in whole brains of HFP was previously reported [9]. However, an even more remarkable difference between the two chicken lines was the direction of the log2 fold changes of DEGs in HFP (Fig. 1c). The majority of genes downregulated in HFP were upregulated in LFP in response to light. Since Dicer1 is among those genes we hypothesize that the processing of and consequently the signaling by miRNAs is disturbed in HFP birds. Among DEGs in LFP brains after light stimulation, we identified about one-third to be ncRNAs, which we already observed by comparing brain transcriptomes of HFP with LFP [3]. We assume that in HFP ncRNAs are not properly processed due to the absence of the Dicer1 protein. Similar observations were made in transcriptome analyses of post mortem human brains of schizophrenia patients [10]. The authors hypothesized that these “psychiatric ncRNAs” might have an impact on local splicing events leading to transcriptome dysregulation. However, in a more recent study, the authors suggested that a Dicer1 dependent disruption of miRNA biogenesis may play a role in schizophrenia pathogenesis [11].

GABRB2 is an ionotropic type A γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) receptor, which has been linked to schizophrenia in multiple studies (reviewed in [12]). Downregulation of multiple miRNAs has been shown to have an impact on GABRB2 protein levels in humans with internet gaming disorder [13]. Furthermore, it was recently shown in a murine knockout model that the lack of GABRB2 leads to various schizophrenia-like symptoms [14], which goes in line with our observations. We observed a downregulation of GABRB2 in HFP in response to light, which is considered a major trigger of FP behavior. We hypothesize that lower expression levels of GABRB2 in HFP brains (Fig. 1c) are caused by miRNA dysregulation, which ultimately leads to a disruption of GABA-mediated cellular ion influx. GABA is classified as the major inhibitory neurotransmitter, which might explain the low number of DE genes in the brains of HFP in response to light: A constant high level of excitation in neurons in the absence of inhibitory GABA signaling may not leave enough room for a response to be induced, even with the most basic stimuli. Furthermore, this high steady-state of excitation in HFP brains might provide an explanation for the behavior on the physiological level. In addition, the genes GABRA2, GABRB2, GABRE, and GABRG3 were upregulated in the LFP’s response to light (Fig. 1a), which further indicates that there is a lack of GABA receptor upregulation in HFP. In one of our previous studies, an intron variant in the GABRB2 gene was among the top variants associated with extreme FP [4]. This motivated us to repeat our GWAS on SNP chip genotypes imputed to whole-genome density of this half-sib population selected for high and low feather pecking [4] with a modified phenotype (feather pecks delivered box-cox transformed) as described by Iffland et al. [8]. Various variants associated with FP in the proximity to GABA receptors were discovered in that study with a medium density SNP chip based approach. We also discovered genetic variants located in or in close proximity to seven GABA receptor genes including GABRB2 in whole genome sequence density genotypes (Fig. 1e). This and the fact that GABRB2 is among the top candidates in our transcriptome studies and two independent GWAS approaches make GABAergic signaling one of the most promising research targets for future FP studies. It needs to be clarified in functional studies, whether GABA levels significantly differ in the two chicken lines and whether the administration of GABA leads to a reduction in feather pecking behavior. If our theory holds true further research should focus on the dissection of the genetics behind this GABA receptor dysregulation to develop new strategies in the breeding of egg-laying chickens to effectively select against the causative alleles.

The only upregulated gene in HFP after light stimulation was MHCIA2, which has a high similarity to human HLA-C (e-value = 9 × 10–69 as determined by NCBI protein BLAST). HLA-C is a risk factor for schizophrenia [15] that is interferon-inducible [16]. Since Dicer represses the interferon response [17], a lack of Dicer as observed in HFP may lead to activation of immune response genes—a connection that we and others previously established [3, 18, 19].

Another observation that caught our attention was the significant downregulation of the core circadian rhythm genes PER2 and PER3 [20] in HFP in response to light (Fig. 1c). Evidence that disturbances in circadian rhythms trigger severe psychiatric disease has been accumulating [21]. Various studies reported disturbed circadian rhythms in schizophrenia patients or model systems in connection to PER2 and PER3 expression or gene polymorphisms [22–25]. PER3 in particular was linked to attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder [26, 27], which would comply with a hyperactivity disorder model of FP as proposed by Kjaer [28]. The brain transcriptome response of LFP to the light stimulus leads to an upregulation of numerous KEGG pathways (Fig. 1d), all of which have been linked to the circadian clock [29–36]. In HFP we observe a complete loss of gene activation regarding these KEGG pathways, which we conclude to be the result of the previously mentioned high level of constant neuronal excitation. If the neurons of HFP are on a constant high level of excitation the brain most likely does not respond to even basic stimuli.

Conclusion

We currently believe that downregulation of Dicer1 leads to a decrease in miRNA production and further downstream to downregulation of GABRB2 and a lack of upregulation of GABRA2, GABRE, and GABRG3. This could result in high steady-state levels of neuronal excitation in HFP. Furthermore, Dicer1 is a repressor of the interferon response and its downregulation might lead to higher interferon concentrations. Interferons are major signaling proteins that activate various immune response pathways which might explain the previously described increase in immune system-related genes in HFP. The functional validation of these findings could lead to the genetic dissection of feather pecking and build the basis for breeding against this damaging behavior. However, additional validation of these findings needs to be addressed in commercial flocks of egg laying chickens to exclude that these findings are limited to chickens selected for high feather pecking behavior. Due to the manifold commonalities with human psychiatric disorders, especially schizophrenia, chickens that have been selected for FP behavior over multiple generations might serve as a representative model for these conditions.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary Information S1: Differentially expressed genes in brains of low feather pecking and high feather pecking hens after light stimulation (abs. log2 fold change >1, adj. p-value < 0.01). (XLSX 73 kb)

Supplementary Information S2: ClusterProfiler KEGG pathway analysis results of differentially expressed genes from brains of low feather pecking hens after light stimulation. (XLSX 5 kb)

Supplementary Information S3: Genomic variants from genome wide association study of low and high feather peckers with the phenotype “feather pecks delivered box-cox transformed” (p-value < 0.05). (XLSX 18757 kb)

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge support by the Open Access Publication Funds of the Göttingen University.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: JT, JB; Methodology: CFG, JT; Formal analysis and investigation: CFG; Writing—original draft preparation: CFG; Writing—review and editing: JT, JB; Funding acquisition: JT, JB; Resources: JT, JB; Supervision: JT.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. The study was funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG) under file numbers TE622/4-2 and BE3703/8-2. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript. Publication fee was covered by the Open Access Publication Funds of the Göttingen University.

Data availability

All methods applied here have been outlined in previous studies [3, 4]. The raw RNA sequencing data has been deposited at the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (BioProject ID PRJNA656654) and the raw whole genome sequencing data as well (BioProject ID PRJNA664592).

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare to have no competing interests of any kind.

Ethical approval

The research protocol was approved by the German Ethical Commission of Animal Welfare of the Provincial Government of Baden-Wuerttemberg, Germany (code: HOH 35/15 PG, date of approval: April 25, 2017).

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Rodenburg TB, Buitenhuis AJ, Ask B, et al. Heritability of feather pecking and open-field response of laying hens at two different ages. Poult Sci. 2003;82:861–867. doi: 10.1093/ps/82.6.861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brunberg E, Jensen P, Isaksson A, et al. Feather pecking behavior in laying hens: hypothalamic gene expression in birds performing and receiving pecks. Poult Sci. 2011;90:1145–1152. doi: 10.3382/ps.2010-00961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Falker-Gieske C, Mott A, Preuß S, et al. Analysis of the brain transcriptome in lines of laying hens divergently selected for feather pecking. BMC Genomics. 2020 doi: 10.1186/s12864-020-07002-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Falker-Gieske C, Iffland H, Preuß S, et al. Meta-analyses of genome wide association studies in lines of laying hens divergently selected for feather pecking using imputed sequence level genotypes. BMC Genet. 2020 doi: 10.1186/s12863-020-00920-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Seney ML, Cahill K, Enwright JF, et al. Diurnal rhythms in gene expression in the prefrontal cortex in schizophrenia. Nat Commun. 2019 doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-11335-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Riber AB, Guzman DA. Effects of dark brooders on behavior and fearfulness in layers. Animals (Basel) 2016 doi: 10.3390/ani6010003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bennewitz J, Bögelein S, Stratz P, et al. Genetic parameters for feather pecking and aggressive behavior in a large F2-cross of laying hens using generalized linear mixed models. Poult Sci. 2014;93:810–817. doi: 10.3382/ps.2013-03638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iffland H, Wellmann R, Preuß S, et al. A novel model to explain extreme feather pecking behavior in laying hens. Behav Genet. 2020;50:41–50. doi: 10.1007/s10519-019-09971-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hughes AL, Buitenhuis AJ. Reduced variance of gene expression at numerous loci in a population of chickens selected for high feather pecking. Poult Sci. 2010;89:1858–1869. doi: 10.3382/ps.2010-00827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gandal MJ, Zhang P, Hadjimichael E, et al. Transcriptome-wide isoform-level dysregulation in ASD, schizophrenia, and bipolar disorder. Science. 2018 doi: 10.1126/science.aat8127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rey R, Suaud-Chagny M-F, Dorey J-M, et al. Widespread transcriptional disruption of the microRNA biogenesis machinery in brain and peripheral tissues of individuals with schizophrenia. Transl Psychiatry. 2020 doi: 10.1038/s41398-020-01052-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tsang SY, Ullah A, Xue H. GABRB2 in neuropsychiatric disorders: genetic associations and functional evidences. CPSP. 2019;8:166–176. doi: 10.2174/2211556008666190926115813. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee M, Cho H, Jung SH, et al. Circulating MicroRNA expression levels associated with internet gaming disorder. Front Psychiatry. 2018 doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yeung RK, Xiang Z-H, Tsang S-Y, et al. Gabrb2-knockout mice displayed schizophrenia-like and comorbid phenotypes with interneuron-astrocyte-microglia dysregulation. Transl Psychiatry. 2018;8:128. doi: 10.1038/s41398-018-0176-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.(2012) Genome-wide association study implicates HLA-C*01:02 as a risk factor at the major histocompatibility complex locus in schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry 72:620–628. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.05.035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Campbell IL, Bizilj K, Colman PG, et al. Interferon-gamma induces the expression of HLA-A, B, C but not HLA-DR on human pancreatic beta-cells. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1986;62:1101–1109. doi: 10.1210/jcem-62-6-1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gurung C, Fendereski M, Sapkota K, et al. Dicer represses the interferon response and the double-stranded RNA-activated protein kinase pathway in mouse embryonic stem cells. J Biol Chem. 2021;296:100264. doi: 10.1016/j.jbc.2021.100264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Parmentier HK, Rodenburg TB, de Vries Reilingh G, et al. Does enhancement of specific immune responses predispose laying hens for feather pecking? Poult Sci. 2009;88:536–542. doi: 10.3382/ps.2008-00424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van der Eijk JAJ, Verwoolde MB, de Vries Reilingh G, et al. Chicken lines divergently selected on feather pecking differ in immune characteristics. Physiol Behav. 2019;212:112680. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2019.112680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hardin PE, Hall JC, Rosbash M. Feedback of the Drosophila period gene product on circadian cycling of its messenger RNA levels. Nature. 1990;343:536–540. doi: 10.1038/343536a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Karatsoreos IN. Links between circadian rhythms and psychiatric disease. Front Behav Neurosci. 2014 doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2014.00162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moons T, Claes S, Martens GJM, et al. Clock genes and body composition in patients with schizophrenia under treatment with antipsychotic drugs. Schizophr Res. 2011;125:187–193. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2010.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu JJ, Sudic Hukic D, Forsell Y, et al. Depression-associated ARNTL and PER2 genetic variants in psychotic disorders. Chronobiol Int. 2015;32:579–584. doi: 10.3109/07420528.2015.1012588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sun H-Q, Li S-X, Chen F-B, et al. Diurnal neurobiological alterations after exposure to clozapine in first-episode schizophrenia patients. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2016;64:108–116. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2015.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Johansson A-S, Owe-Larsson B, Hetta J, et al. Altered circadian clock gene expression in patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2016;174:17–23. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2016.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Faltraco F, Palm D, Uzoni A, et al. Dopamine adjusts the circadian gene expression of Per2 and Per3 in human dermal fibroblasts from ADHD patients. J Neural Transm. 2021;128:1135–1145. doi: 10.1007/s00702-021-02374-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Palm D, Uzoni A, Simon F, et al. Norepinephrine influences the circadian clock in human dermal fibroblasts from study participants with a diagnosis of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. J Neural Transm. 2021;128:1147–1157. doi: 10.1007/s00702-021-02376-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kjaer JB. Feather pecking in domestic fowl is genetically related to locomotor activity levels: implications for a hyperactivity disorder model of feather pecking. Behav Genet. 2009;39:564–570. doi: 10.1007/s10519-009-9280-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xiao B, Chen T-M, Zhong Y. Possible molecular mechanism underlying cadmium-induced circadian rhythms disruption in zebrafish. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2016;481:201–205. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.10.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Niehaus GD, Ervin E, Patel A, et al. Circadian variation in cell-adhesion molecule expression by normal human leukocytes. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2002;80:935–940. doi: 10.1139/y02-121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lundkvist GB, Kwak Y, Davis EK, et al. A calcium flux is required for circadian rhythm generation in mammalian pacemaker neurons. J Neurosci. 2005;25:7682–7686. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2211-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xiong X, Li W, Nam J et al (2021) Integrin signaling via actin cytoskeleton activates MRTF/SRF to entrain circadian clock. 9

- 33.Zheng X, Yang Z, Yue Z, et al. FOXO and insulin signaling regulate sensitivity of the circadian clock to oxidative stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2007;104:15899–15904. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701599104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ko ML, Jian K, Shi L, et al. Phosphatidylinositol 3 kinase-Akt signaling serves as a circadian output in the retina. J Neurochem. 2009;108:1607–1620. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.05931.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang P, Sun Q, Wan R, et al. Progesterone affects the transcription of genes in the circadian rhythm signaling and hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axes and changes the sex ratio in crucian carp (Carassius auratus) Environ Toxicol Pharmacol. 2020;77:103378. doi: 10.1016/j.etap.2020.103378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vagnerová K, Ergang P, Soták M, et al. Diurnal expression of ABC and SLC transporters in jejunum is modulated by adrenalectomy. Comp Biochem Physiol C. 2019;226:108607. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpc.2019.108607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Information S1: Differentially expressed genes in brains of low feather pecking and high feather pecking hens after light stimulation (abs. log2 fold change >1, adj. p-value < 0.01). (XLSX 73 kb)

Supplementary Information S2: ClusterProfiler KEGG pathway analysis results of differentially expressed genes from brains of low feather pecking hens after light stimulation. (XLSX 5 kb)

Supplementary Information S3: Genomic variants from genome wide association study of low and high feather peckers with the phenotype “feather pecks delivered box-cox transformed” (p-value < 0.05). (XLSX 18757 kb)

Data Availability Statement

All methods applied here have been outlined in previous studies [3, 4]. The raw RNA sequencing data has been deposited at the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (BioProject ID PRJNA656654) and the raw whole genome sequencing data as well (BioProject ID PRJNA664592).