Abstract

Background

This study aimed to explore the underlying mechanism of puerarin against rotavirus (RV), based on network pharmacology analysis and experimental study in vitro.

Methods

The cytopathic effect inhibition assay with different concentrations of puerarin at different times of infection in vitro was applied to evaluate the effect of puerarin against human RV G1P[8] Wa strain (HRV Wa). Subsequently, the potential targets of puerarin and RV-related genes were obtained from online databases. Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment analyses of the major target genes were also performed. Furthermore, the major targets and signaling pathway related to RV infection were verified at the molecular level via Western blot, quantitative real-time reverse transcription PCR (RT-qPCR), and Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) tests.

Results

Our results suggest that puerarin had a certain inhibitory effect on viral replication and proliferation. The network pharmacology analysis showed that a total of 436 puerarin corresponding target and 497 RV-related targets were acquired from the online databases. The core targets of puerarin against RV, such as Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4), tumor necrosis factor (TNF), and caspase 3 (CASP3), were identified from the protein-protein interaction (PPI) network. The KEGG analysis indicated that the TLR signaling pathway was one of the crucial mechanisms of puerarin against RV. In particular, puerarin could inhibit the expression of key factors of the TLR4/nuclear factor kappa-B (NF-κB) signaling pathway in HRV-infected Caco-2 cells and regulate the levels of cellular inflammatory factors.

Conclusions

Based on the network pharmacology analysis and experimental study, the study showed that puerarin not only had an anti-RV effect, but could also modulate the inflammatory response induced by RV infection via the TLR4/NF-κB signaling pathway. This study reveals the potential of puerarin in the treatment of RV infection, suggesting that it might be a promising therapeutic agent.

Keywords: Human RV G1P[8] Wa strain (HRV Wa), puerarin, network pharmacology, Toll-like receptor 4/nuclear factor kappa-B signaling pathway (TLR4/NF-κB signaling pathway)

Introduction

Rotavirus (RV) is a double-stranded unenveloped RNA virus of the Reoviridae family, with a diameter of 75 nm and a “wheel-like” appearance. The RV genome is composed of 11 double-stranded RNA segments, encoding six structural proteins and six non-structural proteins (1). RV is transmitted via the fecal-oral route, which can attack mature intestinal epithelial cells and destroy the complex intestinal ecosystem. The intestinal epithelium is shed and destroyed, and the migration of RV from the crypts to the cilia is accelerated, resulting in a temporary loss of intestinal absorption capacity, and severe watery diarrhea occurs when RV is colonized in the intestine (2). Although its infection rate dropped after vaccination began, RV is still common worldwide and is considered to be one of the major pathogens causing intestinal inflammation in infants and many young children (3,4). Every year, over 200 million children younger than 5 years old are infected with RV, resulting in more than 200,000 deaths worldwide (5). At present, RV infection-induced acute gastroenteritis is a common cause of pediatric hospitalization in developed and developing countries, and poses a huge economic burden (6,7). There is currently no specific treatment for RV. The main treatment for RV-induced gastroenteritis is to prevent or correct severe dehydration and metabolic disorders through rehydration, electrolyte supplementation, and nutritional support (8). In addition, probiotics, zinc, and other biological compounds can also relieve clinical symptoms such as diarrhea (9,10).

Chinese herbs have advantages in the treatment of viral infectious diseases. The root of Pueraria lobata (Willd) Ohwi is a kind of medicinal and edible Chinese herb. It was first recorded in Shennong’s Classic of Materia Medica about 1800 years ago, as a medicinal herb that can strengthen the Yang Qi (energy) of the spleen and stomach, and relieve diarrhea. The root of Pueraria lobata is often used in the clinical treatment of RV gastroenteritis. Puerarin, an isoflavone compound, is the main component of the root of Pueraria lobata. It has a variety of pharmacological properties, including anti-inflammatory (11), antioxidative (12), anti-tumor, and circulation-improving effects (13,14). In addition, studies have shown that puerarin has antiviral effects, including epidemic diarrhea viruses and the influenza virus (15,16). However, there remains a lack of relevant reports demonstrating the antiviral effect of puerarin against RV.

Network pharmacology is a novel research method that integrates the general ideas of systems biology and computer technology. The systematic and collaborative characteristics of network pharmacology are similar to the theory of traditional Chinese medicine (17). Due to the multi-target and multi-channel characteristics of Chinese herbal medicine, its mechanism of action is difficult to fully explain. Network pharmacology provides new ideas and scientific support for the research of complex systems of Chinese herbal medicine, and has been widely used in the discovery of active compounds, interpretation of the overall mechanism of action, as well as analysis of drug combination and prescription compatibility. Puerarin has a variety of therapeutic effects, and there are many literatures on the mechanism of puerarin action based on network pharmacology. However, the anti-RV effect of puerarin has not been studied, so we used network pharmacology to analyze the anti-RV effect of puerarin and further carried out experimental verification. The complex molecular correlation of targets and pathways for puerarin against RV was comprehensively and systematically analyzed via the construction of puerarin-RV-target and target-pathway networks.

In this study, we evaluated the anti-RV effect of puerarin, and then determined the potential targets and pathways of puerarin against RV via network pharmacology analysis. Subsequently, an in vitro Caco-2 cell model infected with the human RV G1P[8] was established to verify the potential mechanisms of puerarin against RV. We present the following article in accordance with the MDAR reporting checklist (available at https://dx.doi.org/10.21037/atm-21-6089).

Methods

Reagents and antibodies

Puerarin (purity ≥98%) (Shanghai Yuanye Biotechnology Co., Ltd. Shanghai, China) was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and diluted in Dulbecco’s-modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM, Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA). The concentration of DMSO in the culture medium was less than 0.02%. The DMEM + DMSO solution was applied as the parallel solvent control. TRIzol, fetal bovine serum (FBS), and 100 U/mL penicillin-streptomycin mixture were purchased from ExCell Bio Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) was obtained from Dojindo Laboratories (Kumamoto, Japan). The reverse transcription kits were obtained from Takara Biological Engineering Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China). The bicinchoninic acid protein assay kits and electrochemiluminescence (ECL) reagent were purchased from Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China). Antibodies against Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4), myeloid differentiation primary response 88(MyD88), tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor 6 (TRAF6), nuclear factor kappa-B p65 (p65) and posphorylation p65 (p-p65), and secondary antibodies were obtained from Abcam (Cambridge, UK). Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits for tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, interferon-γ (IFN-γ), interleukin1β (IL-1β), and IL-6 were purchased from Boster Biological Technology Co., Ltd. (Wuhan, China).

Cells and virus

Caco-2 cells obtained from the Cell Bank of Type Culture Collection of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai, China) were grown in DMEM containing 10% FBS (Gibco, USA) and antibiotics (100 U/mL penicillin and 100 mg/mL streptomycin) at 37 °C in 5% CO2. The human RV G1P[8] Wa strain (HRV Wa) was originally obtained from the Institute of Viral Disease Control and Prevention of the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. HRV Wa pre-activated with trypsin was inoculated on Caco-2 cells at a constant temperature of 37 °C in 5% CO2. The 50% tissue culture infective dose (TCID50) was determined by the Reed-Muench method (TCID50 =10−4.39/100 µL) (18).

When the cytopathic effect (CPE) exceeded 90%, the culture was stopped. The virus culture was frozen and thawed three times, and centrifuged at 1,000 rpm for 10 minutes. The supernatant was then taken and stored at −80 °C for later use.

Cell viability assay

The viability of Caco-2 cells incubated with puerarin was determined using CCK-8 assays. Caco-2 cells (4×104 cells/well) were inoculated in 96-well plates and incubated for 24 h at 37 °C in 5% CO2. Puerarin at different concentrations (10, 20, 40, 80, 160, 320, 640, 1,280, and 2,560 µM) was then added to the wells. Three wells were set for each concentration, and the normal cell control was set simultaneously. After 24 h of treatment, CCK-8 (10 µL/well) was added, and the cells were incubated for an additional 2 h. The absorbance at 450 nm was detected using a microplate reader(Sigma, USA). The 50% cytotoxic concentration (CC50) of puerarin was calculated using a previously described method (19).

Antiviral effects of puerarin

To evaluate the antiviral effect of puerarin against HRV Wa, non-toxic concentrations of puerarin were used to treat Caco-2 cells, and virus-inhibition experiments were performed for different times of virus infection (19). Briefly, for the pre‑treatment with puerarin prior to HRV Wa infection, the cells were treated with different concentrations of puerarin for 2 h. Next, the supernatant was replaced by medium containing 100 TCID50/mL HRV Wa. After 2 h of infection, the supernatant was removed, and the cells were the cultured at 37 °C in 5% CO2 for another 24 h. For the co‑treatment with puerarin and HRV Wa (100 TCID50/mL), the virus solution was treated with puerarin of different concentrations at 4 °C for 6 h, and the mixture was then used to inoculate Caco-2 cells. After incubation at 37 °C for 2 h, the mixture was removed, and the cells were cultured with maintenance medium for another 24 h.

For the post‑treatment with puerarin after 100 TCID50/ml HRV Wa infection, Caco-2 cells were inoculated with virus solution. After adsorption at 37 °C for 2 h, the supernatant was discarded, and puerarin at different concentrations was subsequently added to the culture for another 24 h. Finally, ten microliters of CCK-8 were added into each well for 2 h, and the absorbance at 450 nm was detected using a microplate reader. The drug selectivity index (SI) was calculated based on the ratio of the CC50 to 50% effective concentration (EC50) of the test drug. All experiments were performed in triplicate.

Network pharmacology analysis

Structural information on puerarin was obtained from the NCBI PubChem database (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) (20), a public database of the biological properties and chemical structures of small molecules. The potential targets of puerarin were collected from the following target prediction databases: the traditional Chinese medicine systems pharmacology (TCMSP) Database (http://lsp.nwsuaf.edu.cn/tcmsp.php), the Swiss Target Prediction Database (http://www.swisstargetprediction.ch/), the STITCH Database (http://stitch.embl.de/), and the PharmMapper Database (https://lilab.ecust.edu.cn/pharmmapper/index.php). The targets of RV were obtained from the following three databases: the Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM) Database (http://omim.org/) (21), the DisGeNET database (https://www.disgenet.org/), and the GeneCards Human Genes database (https://www.genecards.org/). The keywords searched were “rotavirus infection” and “rotavirus”. The UniProt database (https://www.uniprot.org/) (22) was adopted to convert the protein names of target genes into their corresponding gene symbols. The targets of RV and puerarin were mapped using Venny 2.1 (http://bioinfogp.cnb.csic.es/tools/venny/index.html) to acquire their common targets.

The protein-protein interaction (PPI) network is a complex network expressing the interactions among target genes. The common targets of puerarin and RV were imported into the STRING database (https://string-db.org/) (23) to generate a file of the interaction relationships among targets, which was then imported into the Cytoscape database (24) for visual processing. The functional annotation of the target genes was analyzed using DAVID 6.8 (https://david.ncifcrf.gov/home.jsp) (25), an annotated database for understanding the biological significance of a large number of genes. In addition, the species and background were set as “Homo sapiens” in KEGG pathway analysis.

Real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) analysis

The total RNA of Caco-2 cells was extracted with TRIzol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The concentration of the extracted RNA was determined using an ultra-microspectrophotometer (ExCell MINIDROP), and the quality of the RNA was determined by nucleic acid electrophoresis. The RNA was subsequently reverse transcribed to cDNA using a reverse transcription kit (Takara, China). Real-time PCR was performed using the SYBR Green qPCR Master Mix (2×) (ExCell, Shanghai, China) and a Light Cycler 480 II (Roche, Indianapolis, USA). Briefly, the reaction system was prepared as follows: 2 µL of cDNA template, the forward primer and reverse primer at 1 µL each, 12.5 µL of SYBR Green qPCR Master Mix (2×), and 8.5 µL of ddH2O. The RT-qPCR procedure was as follows: 10 min at 95 °C (pre-denaturation), 40 cycles at 95 °C for 20 s, 58 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 20 s (circular reaction). Table 1 displays the sequences of primers. The mRNA levels were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCT method and normalized to β-actin.

Table 1. Primer sequence for RT-qPCR.

| Target | Forward (5´ to 3´) | Reverse (5´ to 3´) |

|---|---|---|

| TLR4 | AGGTTTCCATAAAAGCCGAAAG | CAATGAAGATGATACCAGCACG |

| MyD88 | CGCCGCCTGTCTCTGTTCTTG | GGTCCGCTTGTGTCTCCAGTTG |

| TRAF6 | GCAGAGAAGGCGGAAGCAGTG | TGGTAGAGGACGGACACAGACAC |

| β-actin | CCCATCTATGAGGGTTACGC | TTTAATGTCACGCACGATTTC |

RT-qPCR, real-time reverse transcription PCR; TLR4, Toll-like receptor 4.

Western blot analysis

The expression of key proteins of the TLR4/NF-κB signaling pathway was quantified by western blot. Total protein was extracted from Caco-2 cells, and the protein concentration was measured using the BCA method. The protein samples were separated by 12% SDS-PAGE and then transferred to a 0.2 µm PVDF membrane (Millipore, USA) (19). The membrane was washed three times with TBST for 1 min each time, blocked with 5% skim milk powder at 25 °C for 3 h, and incubated with the following primary antibodies at 4 °C overnight: anti-TLR4 (2 µg/mL), anti-MyD88 (1:750), anti-TRAF6 (1:5,000), anti-p65 (1:1,000), anti-phospho-p65 (1:1,000), and β-actin (1:5,000). The membranes were washed five times with TBST for 10 min each time and incubated with secondary antibody at 25 °C for 1 h. Subsequently, after washing the membrane five times with TBST, ECL reagent was used to detect the protein signals, and the Image J software (NIH, USA) was used to analyze the optical density of the bands.

ELISA

Caco-2 cells were inoculated with HRV Wa. After adsorption at 37 °C for 2 h, the supernatant of the RV Wa strain was discarded and the cells were washed with PBS. Normal cells and RV-infected cells were set as controls, and 0.1% DMSO was added. Puerarin at different concentrations was added to the other groups, with three duplicate wells in each group. After the cells were cultured in 5 % CO2 at 37 °C for 24 h, the supernatant of cells was collected. The levels of TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, and IFN-γ in each group were assessed using an ELISA kit, according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Statistical analysis

All data were shown as mean ± standard deviation (SD). one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to analyze the experimental results via the SPSS statistics v22.0 software (IBM, USA), followed by a least-significant-difference (LSD) test for multiple comparisons. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Inhibitory effects of puerarin on HRV Wa in vitro

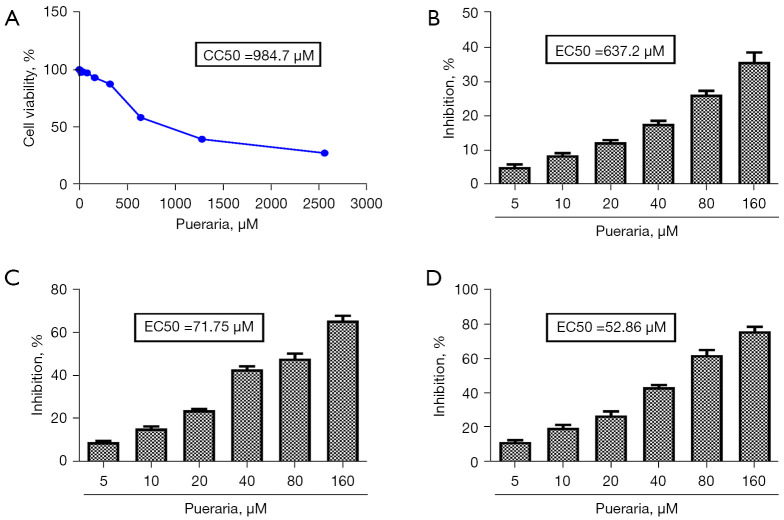

The CC50 of puerarin toward Caco-2 cells was 984.7 µM (Figure 1A). As the concentration of puerarin increased, the cell viability of Caco-2 cells gradually decreased. When the concentration of puerarin exceeded 160 µM, the cell survival rate was less than 90%, so the maximum concentration we chose for subsequent experiments was 160 µM (Figure 1A). When the Caco-2 cells were pre-treated with puerarin for 2 h, the EC50 of puerarin was 637.2 µM (Figure 1B) and the SI was 1.55. In the co-treatment experiment, the EC50 of puerarin was 71.75 µM (Figure 1C) and the SI was 13.72. Moreover, the EC50 of puerarin was 52.86 µM (Figure 1D) and the SI was 18.63 in the post-treatment experiment. These results showed that puerarin exerted an anti-RV effect mainly by inhibiting viral replication and proliferation. Furthermore, the antiviral effect of puerarin increased with the increasing concentration. As the antiviral effect of puerarin in the post-treatment experiment was superior to that in the other two experiments, puerarin treatment after HRV Wa infection was used in the following experiments.

Figure 1.

The inhibition rate of puerarin on HRV Wa inoculated at different stages in vitro. (A) The viability of Caco-2 cells incubated with puerarin was determined using CCK-8 assays. The inhibition of puerarin on HRV Wa in Caco-2 cells at pre-treatment (B), co-treatment (C), and post-treatment (D). All data were presented as the mean ± SD of three individual experiments. HRV Wa, human RV G1P[8] Wa strain; CCK-8, Cell Counting Kit-8.

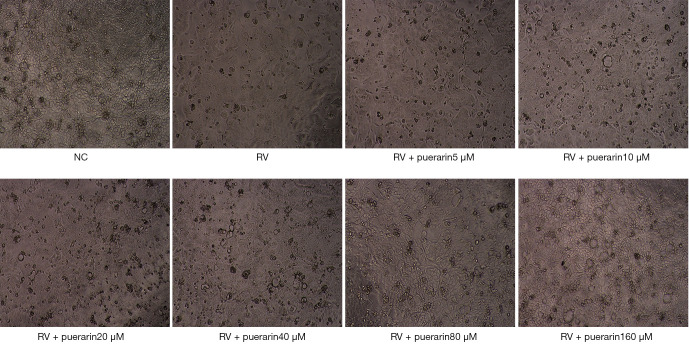

Two hours after the RV infection, the effect of puerarin on the pathological changes of virus-infected Caco-2 cells was observed under the microscope (Figure 2). Caco-2 cells in the normal control (NC) group were oval, uniform in shape, and tightly connected, with clear cell edges and fast growth. Caco-2 cells in the RV group showed an uneven morphology with vacuoles, enlarged intercellular spaces, blurred edges, and slow growth. Some cells were not firmly attached to the wall, and the number of dead cells and amount of cell debris increased. The pathological changes caused by HRV Wa were reduced when puerarin was applied to the Caco-2 cells. As the concentration of puerarin increased, the number of dead cells and cell vacuoles decreased, and the edges of the cells became clearer and more tightly connected.

Figure 2.

The effect of puerarin (5, 10, 20, 40, 80, and 160 µM) on the pathological changes of HRV Wa-infected Caco-2 cells in the post-treatment experiment (40×). HRV Wa, human RV G1P[8] Wa strain; NC, normal control; RV, rotavirus.

Network pharmacology results

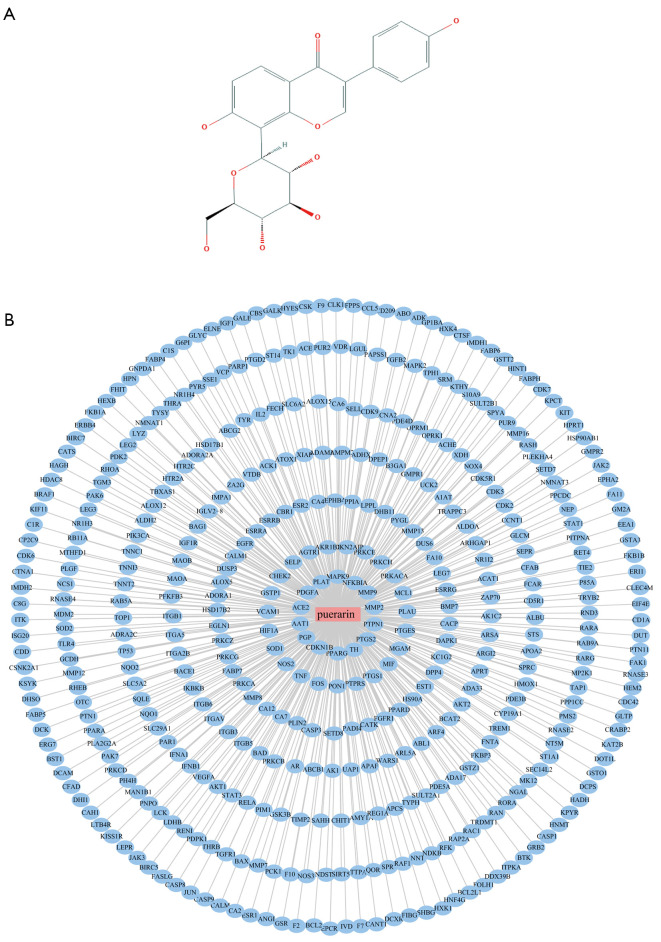

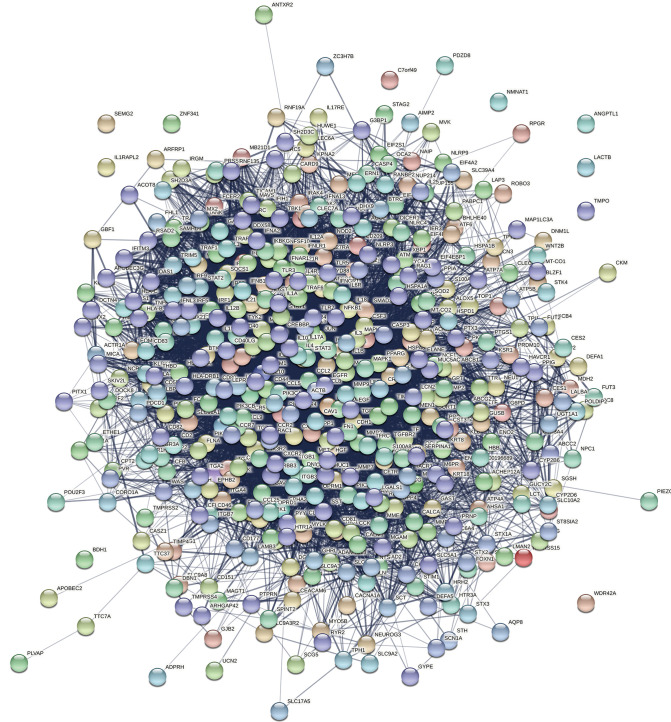

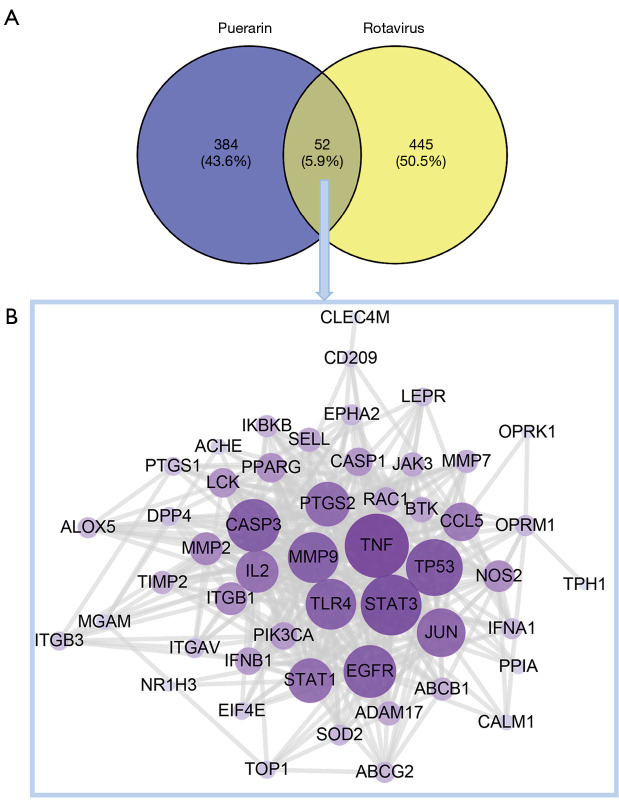

Puerarin is a flavonoid extracted from the root of Pueraria lobata (Willd) Ohwi, and its two-dimensional structure is shown in Figure 3A. A total of 436 corresponding target genes were identified via the Swiss Target Prediction, STITCH, and the PharmMapper databases, which were used to construct a PPI network consisting of 437 nodes (Figure 3B). After merging and removing duplicate projects, a total of 497 RV-related targets were acquired from the OMIM, GeneCards, and DisGeNET databases (Figure 4). After target mapping, 52 overlapped targets were obtained as the related targets of puerarin against RV (Figure 5A and Table 2). These 52 targets were analyzed by STRING and visualized with Cytoscape 3.7.2. We removed the target NMNAT1, as it had no interaction with other targets, and finally obtained a PPI network with 51 targets and 384 edges (Figure 5B).

Figure 3.

The PPI network of the puerarin. (A) The 2D structure of puerarin. (B) 436 candidate targets of puerarin were identified to establish the PPI network. The blue nodes represent the target protein of puerarin. PPI, protein-protein interaction.

Figure 4.

The corresponding targets of RV. RV, rotavirus.

Figure 5.

The collective targets of puerarin and RV were identified. (A) The Venn diagram of the overlapped and specific targets among puerarin and RV. (B) The PPI network of puerarin-RV. RV, rotavirus; PPI, protein-protein interaction.

Table 2. Targets of puerarin in the treatment of RV.

| No | Target name | Gene name | UniProt ID |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Interferon alpha-1 | IFNA1 | P01562 |

| 2 | Integrin beta-1 | ITGB1 | P05556 |

| 3 | Tyrosine-protein kinase JAK3 | JAK3 | P52333 |

| 4 | Disintegrin and metalloproteinase domain-containing protein 17 | ADAM17 | P78536 |

| 5 | Integrin alpha-V | ITGAV | P06756 |

| 6 | Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 | STAT3 | P40763 |

| 7 | Caspase-1 | CASP1 | P29466 |

| 8 | Tryptophan 5-hydroxylase 1 | TPH1 | P17752 |

| 9 | Prostaglandin G/H synthase 2 | PTGS2 | P35354 |

| 10 | Metalloproteinase inhibitor 2 | TIMP2 | P16035 |

| 11 | Integrin beta-3 | ITGB3 | P05106 |

| 12 | C-type lectin domain family 4 member M | CLEC4M | Q9H2X3 |

| 13 | Prostaglandin G/H synthase 1 | PTGS1 | P23219 |

| 14 | Peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase A | PPIA | P62937 |

| 15 | Interferon beta 1 | IFNB1 | P01574 |

| 16 | Transcription factor AP-1 | JUN | P05412 |

| 17 | Calmodulin-1 | CALM1 | P0DP23 |

| 18 | Acetylcholinesterase | ACHE | P22303 |

| 19 | Signal transducer and activator of transcription 1-alpha/beta | STAT1 | P42224 |

| 20 | Caspase-3 | CASP3 | P42574 |

| 21 | Matrix metalloproteinase-9 | MMP9 | P14780 |

| 22 | Matrix metalloproteinase-2 | MMP2 | P08253 |

| 23 | Maltase-glucoamylase | MGAM | O43451 |

| 24 | Ras-related C3 botulinum toxin substrate 1 | RAC1 | P63000 |

| 25 | ATP-binding cassette sub-family G member 2 | ABCG2 | Q9UNQ0 |

| 26 | Matrix metalloproteinase-7 | MMP7 | P09237 |

| 27 | Nitric oxide synthase 2 | NOS2 | P35228 |

| 28 | Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E type 2 | EIF4E2 | O60573 |

| 29 | Superoxide dismutase 2 | SOD2 | P04179 |

| 30 | Arachidonate 5-lipoxygenase | ALOX5 | P09917 |

| 31 | Nicotinamide/nicotinic acid mononucleotide adenylyltransferase 1 | NMNAT1 | Q9HAN9 |

| 32 | Nuclear receptor subfamily 1 group H member 3 | NR1H3 | Q13133 |

| 33 | Ephrin type-A receptor 2 | EPHA2 | P29317 |

| 34 | L-selectin | SELL | P14151 |

| 35 | Epidermal growth factor receptor | EGFR | P00533 |

| 36 | Inhibitor of nuclear factor kappa-B kinase subunit beta | IKBKB | O14920 |

| 37 | Dipeptidyl peptidase 4 | DPP4 | P27487 |

| 38 | Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase catalytic subunit alpha isoform | PIK3CA | P42336 |

| 39 | Interleukin-2 | IL2 | P60568 |

| 40 | Kappa-type opioid receptor 1 | OPRK1 | P41145 |

| 41 | Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma | PPARG | P37231 |

| 42 | ATP-dependent translocase ABCB1 | ABCB1 | P08183 |

| 43 | Tyrosine-protein kinase BTK | BTK | Q06187 |

| 44 | Mu-type opioid receptor 1 | OPRM1 | P35372 |

| 45 | Toll-like receptor 4 | TLR4 | O00206 |

| 46 | CD209 antigen | CD209 | Q9NNX6 |

| 47 | Leptin receptor | LEPR | P48357 |

| 48 | C-C motif chemokine 5 | CCL5 | P13501 |

| 49 | Cellular tumor antigen p53 | TP53 | P04637 |

| 50 | Tumor necrosis factor | TNF | P01375 |

| 51 | Tyrosine-protein kinase Lck | LCK | P06239 |

| 52 | DNA topoisomerase 1 | TOP1 | P11387 |

RV, rotavirus.

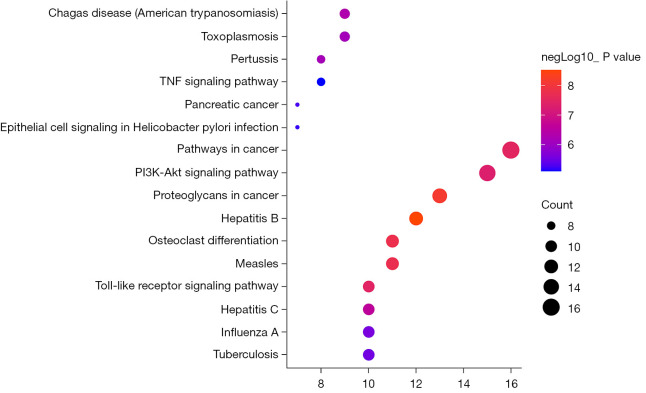

The color and size of the node are proportional to the degree value of the target. The hub targets, which might play a crucial role in RV infection, were TLR4, TNF, caspase 3 (CASP3), endothelial growth factor receptor (EGFR), and IL-2. Among these targets, TLR4 is involved in biological processes such as inflammation, and the immune response. KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of the 51 candidate targets was performed to elucidate the specific mechanism of the effect of puerarin against RV. Subsequently, a total of 85 pathways were acquired, 52 of which were statistically significant (P<0.01). As shown in Figure 6, the inhibition of RV by puerarin may be mainly related to the TLR, TNF, and Phosphatidylinositol 3 kinase/protein kinase B (PI3K/Akt) signaling pathways.

Figure 6.

KEGG pathway analysis of the common targets between puerarin and RV. KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes; RV, rotavirus.

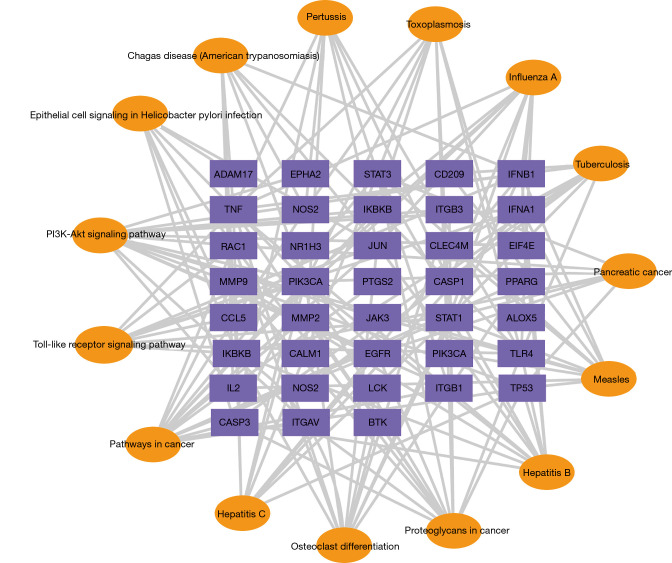

In order to further illustrate the relationship between the crucial KEGG pathways and the corresponding targets, we constructed a target-pathway network, according to the P value. As shown in Figure 7, the TLR signaling pathway was mainly related to targets such as TLR4, TNF, inhibitor of nuclear factor kappa B kinase subunit B (IKBKB), IFNB1, and IFNA1. Therefore, in the following in vitro experiments, we focused on the TLR4 signaling pathway to study the anti-RV mechanism of puerarin.

Figure 7.

Targets-pathways network. The top 15 with lower P value are shown. The target genes of puerarin-RV are shown as a purple node, and the pathways are marked with yellow nodes. RV, rotavirus.

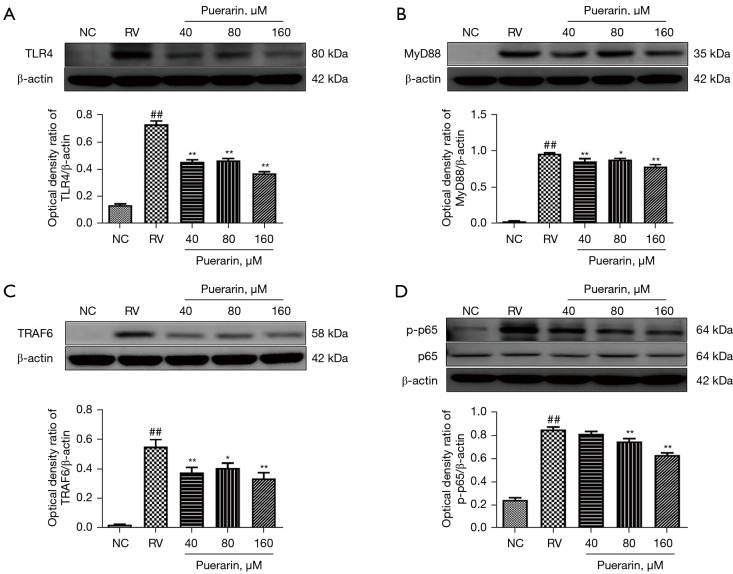

Effect of puerarin on the TLR4/NF-κB signaling pathway

In previous experiments, within the range of puerarin concentration ≤160 µM, the anti-RV effect of puerarin increased with the increase of concentration. Therefore, the concentrations of 40, 80, and 160 µM were used for the subsequent experiments. In order to further evaluate the effects of puerarin on the TLR4/NF-κB signaling pathway in RV-infected Caco-2 cells, the expression of key genes and proteins was measured by western blot and RT-qPCR. The results showed that the protein expression of TLR4, MyD88, TRAF6, and p-p65 significantly increased in Caco-2 cells infected with HRV Wa. However, upon post-treatment with puerarin at different concentrations for 24 h, the expression of these proteins decreased (P<0.05). Moreover, the decrease was the most notable for puerarin at 160 µM (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Puerarin decreased the expression of key proteins in the TLR4/NF-κB signaling pathway in HRV Wa-infected Caco-2 cells. The protein expression of TLR4, MyD88, TRAF6, p65, and p-p65 in Caco-2 cells was measured by western blot, and the bands were quantitatively analyzed (A-D). Significant differences between groups were indicated as ##, P<0.01 vs. NC group; *, P<0.05, **, P<0.01 vs. RV group, n=3. TLR4, Toll-like receptor 4; NF-κB, nuclear factor kappa-B; HRV Wa, human RV G1P[8] Wa strain; NC, normal control; RV, rotavirus.

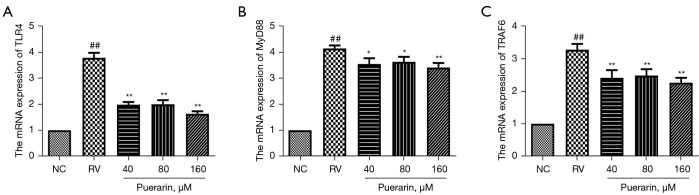

Similar results at the mRNA levels were observed by RT-qPCR. As shown in Figure 9, the mRNA expression of TLR4, MyD88, and TRAF6 was significantly upregulated in Caco-2 cells infected with HRV Wa (P<0.05). After treatment with puerarin for 24 h, the mRNA expression of TLR4, MyD88, and TRAF6, in HRV Wa-infected Caco-2 cells decreased considerably (P<0.05).

Figure 9.

Puerarin decreased the mRNA expression of the TLR4, MyD88, and TRAF6, in HRV Wa-infected Caco-2 cells. The mRNA expression of the TLR4, MyD88, and TRAF6 in Caco-2 cells was detected by RT-qPCR analysis (A-C). Significant differences between groups were indicated as ##, P<0.01 vs. NC group; *, P<0.05; **, P<0.01 vs. RV group, n=3. TLR4, Toll-like receptor 4; HRV Wa, human RV G1P[8] Wa strain; RT-qPCR, real-time reverse transcription PCR; NC, normal control; RV, rotavirus.

Puerarin modulated the inflammation of HRV Wa-infected cells

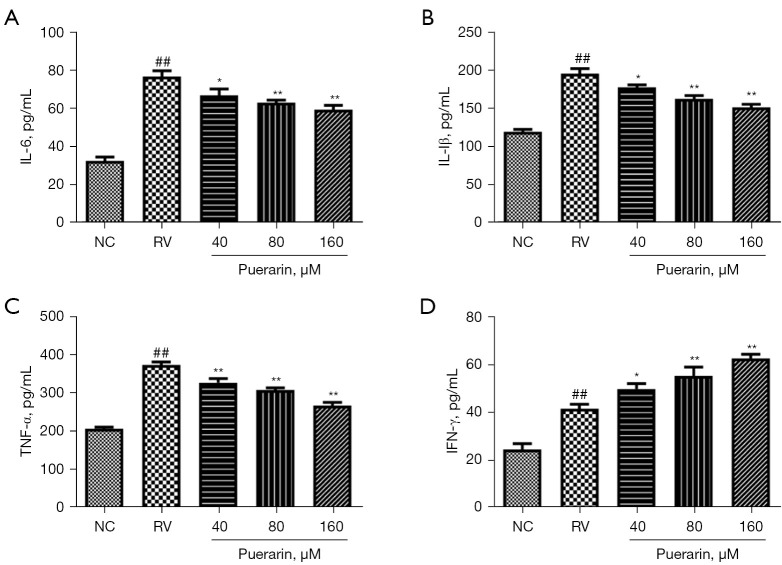

It is well known that RV infection could cause a strong inflammatory response. In order to further assess the effect of puerarin on the inflammatory response induced by RV infection, we detected the levels of IL-6, IL-1β, TNF-α, and IFN-γ by ELISA (Figure 10). The levels of IL-6, IL-1β, TNF-α, and IFN-γ in the RV Wa-infected cells were significantly higher than those in the NC group (P<0.05). The levels of IL-6, IL-1β, and TNF-α sharply decreased after puerarin treatment, while the level of IFN-γ increased further (P<0.05).

Figure 10.

Puerarin modulated the inflammation of HRV Wa-infected cells. The levels of the IL-6, IL-1β, TNF-α, and IFN-γ in virus-infected cells were detected by ELISA (A-D). Significant differences between groups were indicated as ##, P<0.01 vs. NC group; *, P<0.05; **, P<0.01 vs. RV group, n=3. HRV Wa, human RV G1P[8] Wa strain; IL-1β, interleukin1β; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor-α; IFN-γ, interferon-γ; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; NC, normal control; RV, rotavirus.

Discussion

HRV Wa is a common standard strain in RV research (26,27), with strong virulence and good stability (28). According to the antigenicity of the structural proteins, VP4 and VP7 of RV, RV has been genotyped as the G and P genotypes, respectively (29). At least 37 G and 50 P genotypes of human and animal RVs have been distinguished (30). The most common combination of G and P genotypes of human RVs is G1P[8], G2P[4], G3P[8], G4P[8], and G9P[8], among which G1P[8] is the most prevalent worldwide (31). Caco-2 cells are similar to human intestinal epithelial cells in both structure and function, and are commonly used in in vitro experiments of RV infection (32). Therefore, we studied the anti-RV effect of puerarin on Caco-2 cells infected with the HRV G1P[8] Wa strain in vitro. First, we investigated CC50 to study the toxicity of puerarin on Caco-2 cells, and the result was 984.7 µM, indicating that puerarin had low cytotoxicity. Next, the influence of puerarin (within the safe concentration range) on HRV Wa was measured before, during, and after RV infection in vitro. The results showed that puerarin could significantly inhibit HRV Wa at different stages of viral infection and reduce the cytopathic changes. Moreover, as the concentration of puerarin increased, the inhibitory effect on RV was enhanced. It is worth noting that the antiviral effect of post-treatment with puerarin was better than that of pre- and co-treatment, so post-treatment with puerarin was used in the subsequent experiments.

Compared with the previous research methods, network pharmacology confirms to the characteristics of the “overall concept” of traditional Chinese medicine, and provides new perspectives for the discovery of bioactive substances, mechanism research, quality control and many other fields. Considering the multi-component, multi-path, and multi-target features of Chinese herbal medicine, the network pharmacological method was used to further uncover the potential mechanisms of puerarin against RV. A total of 436 corresponding target genes of puerarin and 497 RV-related targets were identified, and finally 52 potential targets for the treatment of RV were obtained. These targets, such as TLR4, TNF, Interleukin, and CASP3, are involved in many biological processes, such as inflammation, the immune response, and cell proliferation and apoptosis. KEGG enrichment analysis indicated that the TLR signaling pathway was a significant pathway of puerarin against RV. Moreover, puerarin not only had anti-RV effects, but also exhibited therapeutic effects on hepatitis B, measles, hepatitis C, influenza A, and other viral infections, demonstrating its broad-spectrum antiviral effects. As an emerging technology, network pharmacology has been widely used in the research of drug action mechanism, new drug development and other fields, but there are still some problems, such as weak function of database software, high cost of database development and maintenance, error in target prediction and need to be verified by experiment. Therefore, we carried out subsequent experimental verification.

As pattern-recognition receptors, TLRs are the first line of defense against pathogenic microorganisms (32). When pathogens invade the human immune system, TLRs can specifically recognize the related molecules that disrupt the immune balance, trigger the host immune response, and establish a barrier against the invasion of pathogens (33). The TLR signaling pathway triggers a signal cascade reaction via interaction with at least five different adaptor proteins (including MyD88 and TRIF), thus producing a variety of pro-inflammatory cytokines and immune regulatory factors (34,35). At least 10 functional TLRs (TLR1-TLR10) have been identified in humans (36). TLR4 is overexpressed or abnormally activated by binding to viral ligands, which ultimately leads intestinal epithelial cells and immune cells to produce a large number of pro-inflammatory molecules, such as chemokines, interferons, and interleukins (37). The TLR4 mRNA levels in the small intestines of RV-infected neonatal rats have been shown to be significantly higher than those of TLR3, TLR5, TLR7, and TLR9 (33). In addition, the expression of the TLR4 mRNA increases in a time-dependent manner in RV-infected HT-29 cells (38).

MyD88 is a key part of the innate immune response that limits RV infection and diarrhea, which plays a crucial role in the initial stage of RV infection (39). The overexpression of TLR4 activates MyD88, MyD88 continues to conduct the signal downward, leading to the activation of NF-κB and the synthesis and release of inflammatory cytokines, thus inducing the inflammatory process of the organism (40,41). When MyD88 is knocked out, the infectivity of RV is enhanced, the transmission of colon and blood is accelerated, which aggravates the diarrhea symptoms of mice-infected RV (39). TRAF6 is a ubiquitin ligase, which is essential in NF-κB activation downstream of TLRs (42), and is a key adapter molecule linking MyD88 and NF-κB. When TRAF6 is activated, the inflammation cascade is also activated, causing the release of substantial inflammatory factors (such as IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α), which lead to tissue damage and organ dysfunction (43,44). In a previous study, the expression of the mRNA and protein of TLR4, MyD88, and TRAF6 was shown to increase significantly in the colon tissue of RV-infected suckling mice (45). Therefore, it is necessary to effectively disrupt the TRAF6-mediated cascade reaction to alleviate the inflammatory response caused by RV infection.

NF-κB could be activated by multiple families of viruses, including the dsRNA virus. Generally, NF-κB is inactive in the cytoplasm by binding to Inhibitor of nuclear factor kappa B (IκB). After viral invasion, IκB kinase leads to the release of NF-κB dimers (46). The dimer NF-κB enters the nucleus in phosphorylated form, thereby further regulating the immune and inflammatory responses and protecting the host from viral invasion (47). P65 is one of the most transcriptionally active dimers in the NF-κB transcription factor family (48). The transcriptional activation domain, which is necessary to actively regulate gene expression, only exists in phosphorylated p65 (49). Inhibition of p65 phosphorylation can negatively regulate NF-κB activation, thereby inhibiting the host inflammatory response. Similar to the above studies, the mRNA and protein expression of TLR4, MyD88, and TRAF6 in RV-infected cells significantly increased in our study. However, the upregulation effect was markedly reversed by different concentrations of puerarin for 24 h. In addition, puerarin could effectively reduce the overexpression of p-p65 protein induced by RV infection.

A significant and almost universal early innate response of receptor cells to viral infection is the release of IFNs, which play a key role in viral clearance and limiting transmission (50). Previous studies have shown that when RV invades, IFNs are triggered by the induction of viral dsRNA or the stimulation of receptors in nearby infected cells. However, RV can inhibit the immune response of IFNs through different mechanisms, so the ability of endogenous IFNs to restrict RV replication is insufficient (51). IFN-γ is the only IFN-II with antiviral activity. Previous studies have shown that IFN-γ specifically induced by HRV is mainly present in the ileum of HRV-infected Gn pigs. When VirHRV attacked, the degree of diarrhea of Gn pigs was negatively correlated with the IFN-γ produced in the intestine, suggesting the protective immune effect of IFN-γ (52). We found that when the Caco-2 cells infected with RV were treated with puerarin, the level of IFN-γ increased significantly, indicating that puerarin induced an increase in IFN-γ and exerted an antiviral effect. The inflammatory response is the most crucial defense mechanism of a host to viruses and other pathogens. The overexpression of pro-inflammatory factors such as IL-6, IL-1β, and TNF-α is often related to the activation of NF-κB during viral replication (53). A previous study showed that the peak levels of IL-6 and TNF-α in the sera of RV-infected piglets were essentially coincident with the peak diarrhea scores, and the level of IL-6 increased 1.5–8 times in the early stage (54). Also, the level of the TNF-α mRNA have been shown to increase significantly in the small intestines and spleens of piglets inoculated with RV (55). Fermented Pueraria lobata extract reduces the levels of IL-1β, TNF-α, and IL-6, and restores the gastrointestinal barrier function in mice (56). Therefore, we studied the effect of puerarin on the expression of inflammatory factors in RV-infected cells. The results revealed that the levels of IL-6, IL-1β, and IFN-γ in the RV Wa-infected Caco-2 cells increased significantly. After treatment with puerarin, the levels of TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 obviously decreased, while the level of IFN-γ further increased. We inferred that the anti-RV effect of puerarin might be related to the inhibition of the TLR4/NF-κB signaling pathway, thereby reducing the levels of inflammatory factors and increasing the level of interferon.

Conclusions

In summary, our results indicated that puerarin exerted an anti-RV effect mainly by inhibiting viral replication and proliferation. In addition, puerarin could modulate the inflammatory response induced by RV via the TLR4/NF-κB signaling pathway. Although these findings cannot fully explain the mechanism of puerarin on RV, they provide a basis for further research. This study reveals the potential of puerarin in the treatment of RV infection, suggesting that it might be a promising therapeutic agent.

Supplementary

The article’s supplementary files as

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the support from the Youth research and innovation team of Shandong University of Traditional Chinese Medicine.

Funding: This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81704038, 81904128); the Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province, China (No. ZR2020MH355); the Post-doctoral Innovation Plan of Shandong Province, China (No. 202003069).

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the MDAR reporting checklist. Available at https://dx.doi.org/10.21037/atm-21-6089

Data Sharing Statement: Available at https://dx.doi.org/10.21037/atm-21-6089

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://dx.doi.org/10.21037/atm-21-6089). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

(English Language Editor: A. Kassem)

References

- 1.Gómez-Rial J, Rivero-Calle I, Salas A, et al. Rotavirus and autoimmunity. J Infect 2020;81:183-9. 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.04.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Luchs A, Timenetsky Mdo C. Group A rotavirus gastroenteritis: post-vaccine era, genotypes and zoonotic transmission. Einstein (Sao Paulo) 2016;14:278-87. 10.1590/S1679-45082016RB3582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tacharoenmuang R, Komoto S, Guntapong R, et al. High prevalence of equine-like G3P8 rotavirus in children and adults with acute gastroenteritis in Thailand. J Med Virol 2020;92:174-86. 10.1002/jmv.25591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tarris G, de Rougemont A, Charkaoui M, et al. Enteric Viruses and Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Viruses 2021;13:104. 10.3390/v13010104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aliabadi N, Antoni S, Mwenda JM, et al. Global impact of rotavirus vaccine introduction on rotavirus hospitalisations among children under 5 years of age, 2008-16: findings from the Global Rotavirus Surveillance Network. Lancet Glob Health 2019;7:e893-903. 10.1016/S2214-109X(19)30207-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kawase M, Hoshina T, Yoneda T, et al. The changes of the epidemiology and clinical characteristics of rotavirus gastroenteritis-associated convulsion after the introduction of rotavirus vaccine. J Infect Chemother 2020;26:206-10. 10.1016/j.jiac.2019.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leino T, Baum U, Scott P, et al. Impact of five years of rotavirus vaccination in Finland - And the associated cost savings in secondary healthcare. Vaccine 2017;35:5611-7. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.08.052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Posovszky C, Buderus S, Classen M, et al. Acute Infectious Gastroenteritis in Infancy and Childhood. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2020;117:615-24. 10.3238/arztebl.2020.0615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parashar UD, Nelson EA, Kang G. Diagnosis, management, and prevention of rotavirus gastroenteritis in children. BMJ 2013;347:f7204. 10.1136/bmj.f7204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sarker SA, Jäkel M, Sultana S, et al. Anti-rotavirus protein reduces stool output in infants with diarrhea: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Gastroenterology 2013;145:740-748.e8. 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.06.053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wu Y, Li Y, Ruan Z, et al. Puerarin Rebuilding the Mucus Layer and Regulating Mucin-Utilizing Bacteria to Relieve Ulcerative Colitis. J Agric Food Chem 2020;68:11402-11. 10.1021/acs.jafc.0c04119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li M, Yuan D, Liu Y, et al. Dietary Puerarin Supplementation Alleviates Oxidative Stress in the Small Intestines of Diquat-Challenged Piglets. Animals (Basel) 2020;10:631. 10.3390/ani10040631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.He L, Wang T, Chen BW, et al. Puerarin inhibits apoptosis and inflammation in myocardial cells via PPARα expression in rats with chronic heart failure. Exp Ther Med 2019;18:3347-56. 10.3892/etm.2019.7984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xu H, Hu M, Liu M, et al. Nano-puerarin regulates tumor microenvironment and facilitates chemo- and immunotherapy in murine triple negative breast cancer model. Biomaterials 2020;235:119769. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2020.119769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang H, Liao D, Zhou G, et al. Antiviral activities of resveratrol against rotavirus in vitro and in vivo. Phytomedicine 2020;77:153230. 10.1016/j.phymed.2020.153230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu M, Zhang Q, Yi D, et al. Quantitative Proteomic Analysis Reveals Antiviral and Anti-inflammatory Effects of Puerarin in Piglets Infected With Porcine Epidemic Diarrhea Virus. Front Immunol 2020;11:169. 10.3389/fimmu.2020.00169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kibble M, Saarinen N, Tang J, et al. Network pharmacology applications to map the unexplored target space and therapeutic potential of natural products. Nat Prod Rep 2015;32:1249-66. 10.1039/C5NP00005J [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mosmann T. Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J Immunol Methods 1983;65:55-63. 10.1016/0022-1759(83)90303-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ma Q, Huang W, Zhao J, et al. Liu Shen Wan inhibits influenza a virus and excessive virus-induced inflammatory response via suppression of TLR4/NF-κB signaling pathway in vitro and in vivo. J Ethnopharmacol 2020;252:112584. 10.1016/j.jep.2020.112584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang Y, Bryant SH, Cheng T, et al. PubChem BioAssay: 2017 update. Nucleic Acids Res 2017;45:D955-63. 10.1093/nar/gkw1118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Amberger JS, Bocchini CA, Schiettecatte F, et al. OMIM.org: Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM®), an online catalog of human genes and genetic disorders. Nucleic Acids Res 2015;43:D789-98. 10.1093/nar/gku1205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.UniProt Consortium . UniProt: a worldwide hub of protein knowledge. Nucleic Acids Res 2019;47:D506-15. 10.1093/nar/gky1049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Szklarczyk D, Gable AL, Lyon D, et al. STRING v11: protein-protein association networks with increased coverage, supporting functional discovery in genome-wide experimental datasets. Nucleic Acids Res 2019; 47:D607-13. 10.1093/nar/gky1131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Otasek D, Morris JH, Bouças J, et al. Cytoscape Automation: empowering workflow-based network analysis. Genome Biol 2019;20:185. 10.1186/s13059-019-1758-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huang da W , Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat Protoc 2009;4:44-57. 10.1038/nprot.2008.211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vlasova AN, Shao L, Kandasamy S, et al. Escherichia coli Nissle 1917 protects gnotobiotic pigs against human rotavirus by modulating pDC and NK-cell responses. Eur J Immunol 2016;46:2426-37. 10.1002/eji.201646498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guo Y, Candelero-Rueda RA, Saif LJ, et al. Infection of porcine small intestinal enteroids with human and pig rotavirus A strains reveals contrasting roles for histo-blood group antigens and terminal sialic acids. PLoS Pathog 2021;17:e1009237. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1009237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Munlela B, João ED, Donato CM, et al. Whole Genome Characterization and Evolutionary Analysis of G1P8 Rotavirus A Strains during the Pre- and Post-Vaccine Periods in Mozambique (2012-2017). Pathogens 2020;9:1026. 10.3390/pathogens9121026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Novikova NA, Sashina TA, Epifanova NV, et al. Long-term monitoring of G1P[8] rotaviruses circulating without vaccine pressure in Nizhny Novgorod, Russia, 1984-2019. Arch Virol 2020;165:865-75. 10.1007/s00705-020-04553-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rojas M, Dias HG, Gonçalves JLS, et al. Genetic diversity and zoonotic potential of rotavirus A strains in the southern Andean highlands, Peru. Transbound Emerg Dis 2019;66:1718-26. 10.1111/tbed.13207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Patton JT. Rotavirus diversity and evolution in the post-vaccine world. Discov Med 2012;13:85-97. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hagbom M, De Faria FM, Winberg ME, et al. Neurotrophic Factors Protect the Intestinal Barrier from Rotavirus Insult in Mice. mBio 2020;11:02834-19. 10.1128/mBio.02834-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Azagra-Boronat I, Massot-Cladera M, Knipping K, et al. Oligosaccharides Modulate Rotavirus-Associated Dysbiosis and TLR Gene Expression in Neonatal Rats. Cells 2019;8:876. 10.3390/cells8080876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hurst J, von Landenberg P. Toll-like receptors and autoimmunity. Autoimmun Rev 2008;7:204-8. 10.1016/j.autrev.2007.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cario E. Toll-like receptors in inflammatory bowel diseases: a decade later. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2010;16:1583-97. 10.1002/ibd.21282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vijay K. Toll-like receptors in immunity and inflammatory diseases: Past, present, and future. Int Immunopharmacol 2018;59:391-412. 10.1016/j.intimp.2018.03.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gay NJ, Symmons MF, Gangloff M, et al. Assembly and localization of Toll-like receptor signalling complexes. Nat Rev Immunol 2014;14:546-58. 10.1038/nri3713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xu J, Yang Y, Wang C, et al. Rotavirus and coxsackievirus infection activated different profiles of toll-like receptors and chemokines in intestinal epithelial cells. Inflamm Res 2009;58:585-92. 10.1007/s00011-009-0022-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Uchiyama R, Chassaing B, Zhang B, et al. MyD88-mediated TLR signaling protects against acute rotavirus infection while inflammasome cytokines direct Ab response. Innate Immun 2015;21:416-28. 10.1177/1753425914547435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ciesielska A, Matyjek M, Kwiatkowska K. TLR4 and CD14 trafficking and its influence on LPS-induced pro-inflammatory signaling. Cell Mol Life Sci 2021; 78:1233-61. 10.1007/s00018-020-03656-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li C, Ai G, Wang Y, et al. Oxyberberine, a novel gut microbiota-mediated metabolite of berberine, possesses superior anti-colitis effect: Impact on intestinal epithelial barrier, gut microbiota profile and TLR4-MyD88-NF-κB pathway. Pharmacol Res 2020;152:104603. 10.1016/j.phrs.2019.104603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.He X, Zheng Y, Liu S, et al. MiR-146a protects small intestine against ischemia/reperfusion injury by down-regulating TLR4/TRAF6/NF-κB pathway. J Cell Physiol 2018;233:2476-88. 10.1002/jcp.26124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hu L, Xu J, Xie X, et al. Oligomerization-primed coiled-coil domain interaction with Ubc13 confers processivity to TRAF6 ubiquitin ligase activity. Nat Commun 2017;8:814. 10.1038/s41467-017-01290-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Roh KH, Lee Y, Yoon JH, et al. TRAF6-mediated ubiquitination of MST1/STK4 attenuates the TLR4-NF-κB signaling pathway in macrophages. Cell Mol Life Sci 2021;78:2315-28. 10.1007/s00018-020-03650-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chen X, Liu L, Chen W, et al. Ziyuglycoside II Inhibits Rotavirus Induced Diarrhea Possibly via TLR4/NF-κB Pathways. Biol Pharm Bull 2020;43:932-7. 10.1248/bpb.b19-00771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang W, Zhang R, Wang T, et al. Selenium inhibits LPS-induced pro-inflammatory gene expression by modulating MAPK and NF-κB signaling pathways in mouse mammary epithelial cells in primary culture. Inflammation 2014;37:478-85. 10.1007/s10753-013-9761-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Oeckinghaus A, Hayden MS, Ghosh S. Crosstalk in NF-κB signaling pathways. Nat Immunol 2011;12:695-708. 10.1038/ni.2065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dorrington MG, Fraser IDC. NF-κB Signaling in Macrophages: Dynamics, Crosstalk, and Signal Integration. Front Immunol 2019;10:705. 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hayden MS, Ghosh S. Shared principles in NF-kappaB signaling. Cell 2008;132:344-62. 10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Villena J, Vizoso-Pinto MG, Kitazawa H. Intestinal Innate Antiviral Immunity and Immunobiotics: Beneficial Effects against Rotavirus Infection. Front Immunol 2016;7:563. 10.3389/fimmu.2016.00563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sherry B. Rotavirus and reovirus modulation of the interferon response. J Interferon Cytokine Res 2009;29:559-67. 10.1089/jir.2009.0072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yuan L, Wen K, Azevedo MS, et al. Virus-specific intestinal IFN-gamma producing T cell responses induced by human rotavirus infection and vaccines are correlated with protection against rotavirus diarrhea in gnotobiotic pigs. Vaccine 2008;26:3322-31. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.03.085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhang Q, Yu K, Cao Y, et al. miR-125b promotes the NF-κB-mediated inflammatory response in NAFLD via directly targeting TNFAIP3. Life Sci 2021;270:119071. 10.1016/j.lfs.2021.119071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kim JH, Kim K, Kim W. Genipin inhibits rotavirus-induced diarrhea by suppressing viral replication and regulating inflammatory responses. Sci Rep 2020;10:15836. 10.1038/s41598-020-72968-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Alfajaro MM, Kim HJ, Park JG, et al. Anti-rotaviral effects of Glycyrrhiza uralensis extract in piglets with rotavirus diarrhea. Virol J 2012;9:310. 10.1186/1743-422X-9-310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Choi S, Woo JK, Jang YS, et al. Fermented Pueraria Lobata extract ameliorates dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis by reducing pro-inflammatory cytokines and recovering intestinal barrier function. Lab Anim Res 2016;32:151-9. 10.5625/lar.2016.32.3.151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The article’s supplementary files as