Abstract

Background & Aims:

Functional luminal imaging probe (FLIP) Panometry can evaluate esophageal motility in response to sustained esophageal distension at the time of sedated endoscopy. This study aimed to describe a classification of esophageal motility using FLIP Panometry and evaluate it against high-resolution manometry (HRM) and Chicago Classification v4.0 (CCv4.0).

Methods:

539 adult patients that completed FLIP and HRM with a conclusive CCv4.0 diagnosis were included in the primary analysis. 35 asymptomatic volunteers (“controls”) and 148 patients with an inconclusive CCv4.0 diagnosis or systemic sclerosis were also described. Esophagogastric junction (EGJ) opening and the contractile response to distension (i.e. secondary peristalsis) were evaluated with 16-cm FLIP performed during sedated endoscopy and analyzed using a customize software program. HRM was classified according to CCv4.0.

Results:

In the primary analysis, 156 patients (29%) had normal motility on FLIP Panometry, defined by normal EGJ opening (NEO) and a normal or borderline contractile response; 95% of these patients had normal motility or ineffective esophageal motility on HRM. 202 patients (37%) had obstruction with weak contractile response, defined as reduced EGJ opening and absent contractile response or impaired/disordered contractile response, on FLIP Panometry; 92% of these patients had a disorder of EGJ outflow per CCv4.0.

Conclusions:

Classifying esophageal motility in response to sustained distension with FLIP Panometry parallels the swallow-associated motility evaluation provided with HRM and CCv4.0. Thus, FLIP Panometry provides a well-tolerated method that can complement, or in some cases be an alternative to HRM, for evaluating esophageal motility disorders.

Keywords: dysphagia, achalasia, spasm, impedance

Introduction

The functional luminal imaging probe (FLIP) utilizes impedance planimetry technology to measure lumen dimensions along the length of the esophagus and esophageal distensibility (i.e. the relationship of dimension with distensive pressure) during controlled volumetric distension. In 2014, a new technique was developed to assess esophageal motility using FLIP and a volume distention protocol: FLIP Panometry.1 By displaying the esophageal diameter changes along a space-time continuum with associated pressure utilizing FLIP Panometry, esophagogastric junction (EGJ) opening mechanics and the contractile response to distension, i.e. secondary peristalsis, can be assessed yielding an evaluation of esophageal motility.1, 2

Esophageal high-resolution manometry (HRM) is generally considered the primary method to detect esophageal motility disorders.3, 4 The FLIP Panometry evaluation of distension-induced esophageal motility offers a method to assess esophageal motility potentially akin to HRM, but as FLIP is performed during sedated endoscopy, it may offer a method to assess esophageal motility that is better tolerated by patients than the transnasal manometry catheter. Furthermore, the HRM evaluation of lower esophageal sphincter (LES) relaxation and peristalsis during swallowing may not be sufficient to fully characterize esophageal motility within the construct of the Chicago Classification (CC).5, 6 In fact, CC version 4.0 (CCv4.0) states that the manometric diagnosis of EGJ outflow obstruction (EGJOO) should be considered inconclusive and confirmed by further testing with either esophagram or FLIP prior to treatment.4, 7, 8 The esophageal response to distension that is assessed by FLIP Panometry (but not by the typical manometry study) is an important component of esophageal function that relates to esophageal opening dimensions (essential for esophageal bolus passage) and triggering of secondary peristalsis. Abnormalities of secondary peristalsis have been shown to be associated with both dysphagia and reflux pathology.9, 10 Thus, the assessment of the esophageal response to distension provided by FLIP may parallel and/or complement HRM in the evaluation of esophageal motility.11

We previously reported an evaluation of esophageal motility with FLIP Panometry in a study of 140 patients and 10 controls and demonstrated the relationship of the FLIP motility assessment with that obtained with HRM and the CC (version 3.0).2, 6 Subsequent evaluation and expanded experience with FLIP Panometry has led to refined methodology and analytic approaches for FLIP Panometry related to both evaluation of EGJ opening and the contractile response (CR) to distension.12, 13 The aim of this study was to describe an updated esophageal motility classification of FLIP Panometry and compare it to esophageal motility disorders as defined by HRM and CCv4.0 in asymptomatic controls and a large cohort of symptomatic patients.4

Methods

Subjects

Adult patients (age 18–89) presenting to the Esophageal Center of Northwestern for evaluation of esophageal symptoms between November 2012 and December 2019 who completed FLIP during upper endoscopy and HRM were prospectively evaluated and data maintained in an esophageal motility registry. Consecutive patients evaluated for primary esophageal motility disorders that completed FLIP during sedated endoscopy and a corresponding HRM were included. FLIP was commonly included with the endoscopic evaluation when patients were also being considered for manometry, thus as part of a comprehensive esophageal motility evaluation and/or when there was suspicion for an esophageal motility disorder. Additional clinical evaluation with timed barium esophagram (TBE) was obtained at the discretion of the primary treating gastroenterologist. No endoscopic or surgical treatment transpired between FLIP, HRM, or TBE. Patients with technically limited FLIP or HRM studies were excluded. Patients with previous foregut surgery (including previous pneumatic dilation) or esophageal mechanical obstructions including esophageal stricture, eosinophilic esophagitis, severe reflux esophagitis (Los Angeles-classification C or D), hiatal hernia > 3cm were excluded as these are potential causes of secondary esophageal motor abnormalities (Figure S1). Patients with inconclusive esophageal motility diagnoses based on HRM +/− TBE per CCv4.0 (Table S1) were excluded from the primary analysis (but are described separately) due to the associated clinical uncertainty that limited objective comparison with FLIP Panometry, as were patients with known systemic sclerosis.

Additionally, a cohort of healthy, asymptomatic adult volunteers (“controls”) were included. Informed consent was obtained for subject participation; control subjects were paid for their participation. The study protocol was approved by the Northwestern University Institutional Review Board. This cohort of patients and controls has been previously described.13, 14

FLIP Study Protocol

The FLIP study using 16-cm FLIP (EndoFLIP® EF-322N; Medtronic, Inc, Shoreview, MN) was performed during sedated endoscopy as previously described.2, 12, 15 Endoscopy performed in the left-lateral decubitus position was generally performed using conscious sedation with midazolam and fentanyl; all of the controls were studied using conscious sedation. Other medications, e.g. propofol, were also used with monitored anesthesia care at the discretion of the performing endoscopist in some cases. Although these medications used for endoscopic sedation can alter esophageal motility, the patterns of motility during the FLIP protocol are reproducible and have been shown to predict motility patterns during standard manometry performed without these medications.2, 15–17 With the endoscope withdrawn and after calibration to atmospheric pressure, the FLIP was placed transorally and positioned within the esophagus with 1–3 impedance sensors beyond the EGJ with this positioning maintained throughout the FLIP study. Stepwise 10-ml FLIP distensions beginning with 40 ml and increasing to target volume of 60 or 70 ml were then performed; each stepwise distension volume was maintained for 30–60 seconds.

FLIP Panometry Analysis

FLIP data were exported to a customized program (available open source at http://www.wklytics.com/nmgi) to generate FLIP Panometry plots for analysis as previously described to assess the esophageal contractile response to distension and to classify EGJ opening as summarized in Table 1 and Figure 1.12, 13 FLIP Panometry analysis was performed blinded to clinical characteristics, including HRM results.

Table 1. Evaluation of esophageal motility with FLIP Panometry.

The contractile response to distension was based on evaluation of the FLIP study protocol including from the 50ml to 70ml fill volume. Esophagogastric junction (EGJ) opening applied the EGJ-distensibility index (DI) from the 60ml FLIP fill volume and the maximum EGJ diameter from the 60ml or 70ml FLIP fill volume.

| FLIP Panometry Contractile Response Patterns | Definition |

|---|---|

|

Normal Contractile Response

NCR |

Repetitive Antegrade Contraction (RACs), defined by the RAC Rule of 6s (Ro6s): • ≥6 consecutive antegrade contractions of • ≥6 cm in axial length occurring at • 6+/−3 antegrade contractions per minute regular rate |

|

Borderline Contractile Response

BCR |

• Not meeting RAC Ro6s • Distinct antegrade contractions of at least 6-cm axial length present • Not SRCR |

|

Impaired/Disordered Contractile Response

IDCR |

• No distinct antegrade contractions • May have sporadic or chaotic contractions not meeting antegrade contractions • Not SRCR |

|

Absent Contractile Response

ACR |

• No contractile activity in the esophageal body |

|

Spastic-Reactive Contractile Response

SRCR |

• Presence of any of the following features: • Sustained occluding contractions or • Sustained lower esophageal sphincter (LES) contractions or • Repetitive retrograde contractions (RRCs), defined by at least 6 consecutive retrograde contractions occurring at a rate of > 9 contractions per minute |

| /// /// /// /// /// /// /// /// /// /// /// /// /// /// /// /// /// | |

| FLIP Panometry EGJ opening classification | |

| Reduced EGJ opening (REO) | • EGJ-DI <2.0 mm2/mmHg AND • Maximum EGJ diameter <12mm |

| Borderline-reduced EGJ opening (BrEO) | • EGJ-DI <2.0 mm2/mmHg OR • Maximum EGJ diameter <14 mm, • but not REO |

| Borderline-normal EGJ opening (BnEO) | • Maximum EGJ diameter 14–16 mm OR • EGJ-DI <2.0 mm2/mmHg and maximum EGJ diameter ≥16mm |

| Normal EGJ opening (NEO) | • EGJ-DI ≥2.0 mm2/mmHg AND • Maximum EGJ diameter ≥16mm |

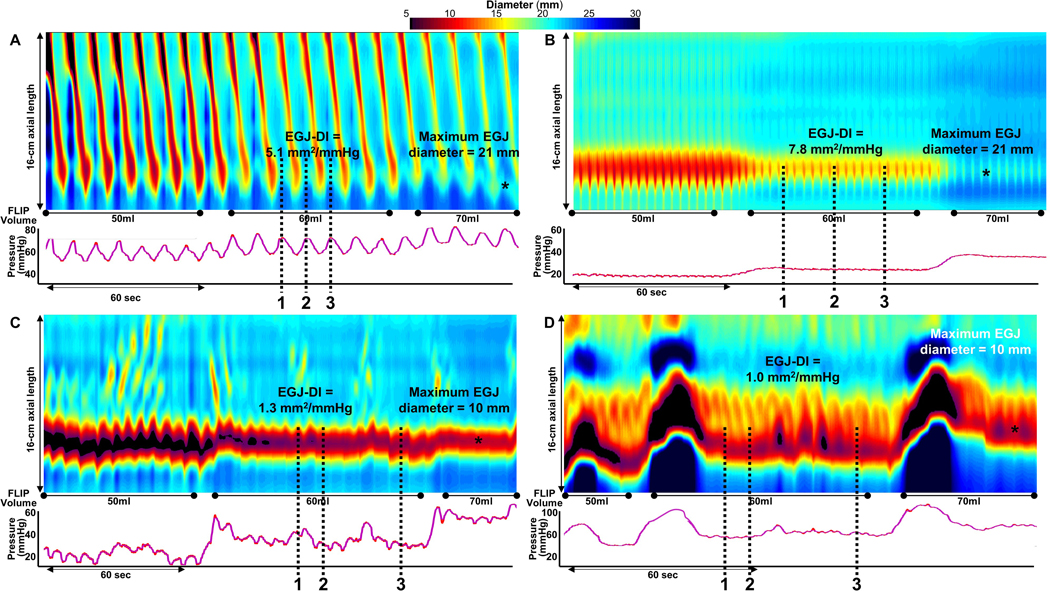

Figure 1. FLIP Panometry esophageal motility classifications.

FLIP Panometry contractile response patterns. FLIP Panometry output from four patients (A-D) is displayed as length (16-cm) x time x color-coded diameter FLIP topography (top panels) with corresponding FLIP pressure (bottom panel); the corresponding high-resolution manometry (HRM) findings are described, but not displayed. A displays a patient with a normal contractile response (CR) with repetitive antegrade contractions and normal esophagogastric junction (EGJ) opening (NEO); classified as normal FLIP Panometry. This patient had normal esophageal motility on high-resolution manometry (HRM). In B, there is an absent CR and NEO; classified as weak FLIP Panometry. This patient had an HRM with absent contractility. In C, there is an impaired-disordered CR and reduced EGJ opening (REO), classified as obstruction with weak CR. This patient had type II achalasia on HRM. In D, there is a spastic-reactive CR with sustained occluding contractions. This patient had type III achalasia on HRM. DI – distensibility index. Figure used with permission from the Esophageal Center of Northwestern.

Esophageal body contractility was identified by a transient decrease in the luminal diameter of at least 3 cm axial length; distinct antegrade contractions spanned at least 6cm in axial length. Studies were reviewed for specific features and patterns of contractility that were then applied to assign a contractile response (CR) pattern (Table 1).12, 13 Repetitive antegrade contractions (RACs) or repetitive retrograde contractions (RRCs) involved contractions of similar directionality that occurred consecutively at a consistent time interval and meeting rate criteria (Table 1).12, 13 The spastic-reactive CR was defined by presence of any of several abnormal (i.e. not observed in asymptomatic controls) FLIP Panometry features (Table 1): RRCs, sustained LES contraction, or sustained occluding contractions. Sustained LES contraction was defined by a transient reduction in diameter attributed to the LES (i.e. not associated with respiration and crural contraction) that was independent of antegrade contractions, lasted longer than 5 seconds, and was associated with an increase in FLIP pressure.12 Sustained occluding contraction was defined as a non-propagating, occluding contraction of the esophageal body that occurred in continuity with the EGJ, persisted for >10 seconds, and was associated with a FLIP pressure increase >35 mmHg.12, 18 As previously described, the CR patterns were reviewed by multiple raters with majority agreement applied for analysis.13

The analysis of EGJ opening applied the EGJ distensibility index (DI) at the 60ml FLIP fill volume and the maximum EGJ diameter that was achieved during the 60ml or 70ml fill volume (Table 1 and Figure 1) as previously described.12 Areas at the EGJ that were affected by dry catheter artifact (i.e. artifact that impacts diameter measurement when occlusion of the FLIP balloon disrupts the electrical current utilized for the impedance planimetry technology) and the first 5 seconds after achieving the 60ml and 70ml fill volume (to avoid incorporation of active-filling effects) were omitted from the EGJ analysis.12 The EGJ-DI (EGJ-midline cross-sectional area divided by pressure) was then measured at the peaks of EGJ-opening (greatest diameters) during the 60ml FLIP fill volume, which was dependent on the presence or absence of antegrade contractions (Figure 1); the median of three EGJ-DI values was applied for analysis. The EGJ-DI was not calculated if the applied FLIP pressure was <15mm Hg; in these cases (9 patients from this cohort), the maximum EGJ-diameter was applied independently for analysis. EGJ opening was then classified as reduced EGJ opening (REO), borderline-reduced EGJ opening (BrEO), borderline-normal EGJ opening (BnEO) or normal EGJ opening (NEO), Table 1.

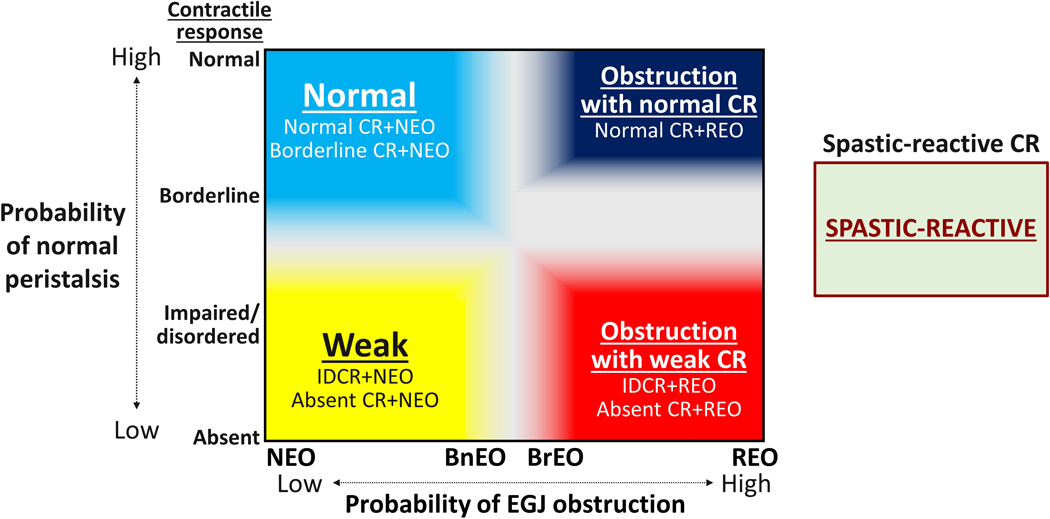

The CR pattern and classification of EGJ opening were applied to assign a FLIP Panometry motility classification (Figure 2). Because features of the spastic-reactive pattern (Table 1) potentially involved either a contractile response of the LES or a manifestation of obstruction, a spastic-reactive motility classification was assigned independently of the EGJ opening classification.12 FLIP Panometry motility classifications were otherwise applied related to combined findings of EGJ opening and contractile response to distension (Figure 2). An inconclusive motility classification was applied for FLIP findings that were associated with potential for clinical uncertainty.

Figure 2. FLIP Panometry classification of esophageal motility.

A combination of the FLIP Panometry contractile response pattern and esophagogastric junction (EGJ) opening classification was applied to classify esophageal motility. Findings associated with clinical uncertainty (i.e. gray zones) were classified as inconclusive. REO – reduced EGJ opening. BrEO – borderline reduced EGJ opening. BnEO – borderline normal EGJ opening. NEO – normal EGJ opening. CR – contractile response. IDCR – impaired/disordered CR. Figure used with permission from the Esophageal Center of Northwestern.

HRM protocol and analysis

After a minimum 6-hour fast, HRM studies were completed using a 4.2-mm outer diameter solid-state assembly with 36 circumferential pressure sensors at 1-cm intervals (Medtronic Inc, Shoreview, MN). The HRM assembly was placed transnasally and positioned to record from the hypopharynx to the stomach with approximately three intragastric pressure sensors. After a 2-minute baseline recording (during which the basal EGJ pressure was measured during end expiration), the HRM protocol was performed with ten, 5-ml liquid swallows in a supine position and with five 5-ml liquid swallows in an upright, seated position.5

Manometry studies were analyzed according to the CCv4.0 and independent of FLIP results, Table S1.4 The IRP, was measured for the 10 supine swallows and 5 upright swallows; median values for each position were applied. A median IRP of >15 mmHg was considered abnormal for supine swallows; a median IRP of >12 mmHg was considered abnormal for upright swallows.4 TBE, was applied when available to patients with an HRM classification of EGJOO to reach an assignment of ‘conclusive’ EGJOO independent of FLIP (Table S1).4, 19, 20 TBE was performed in the upright position and involved drinking 200-mL of low density barium sulfate and images obtained at 1 and 5 minutes; a 12.5-mm barium tablet was also ingested if liquid barium cleared. A TBE was considered abnormal (and thus EGJOO was ‘conclusive) if there was a column height >5cm at 5 minutes or if a column height >5cm at 1 minute in addition to impaction of the 12.5mm barium tablet (i.e. tablet was unable to pass from the esophagus).21

Statistical Analysis

Results were reported as mean (standard deviation; SD), or median (interquartile range; IQR) depending on data distribution. Groups were compared using Chi-square test for categorical variables and ANOVA/t-tests or Kruskal-Wallis/Mann-Whitney U for continuous variables, depending on data distribution. Statistical significance was considered at a two-tailed p-value < 0.05. Post-hoc comparison testing, as appropriate, was completed using a Bonferroni correction.

Results

Subjects

539 patients, mean (SD) age 53 (17) years, 56% female were included in the primary analysis (Table 2). The majority (91%) of patients underwent motility evaluation for dysphagia. 399 patients completed FLIP and HRM on the same day; the remainder had median (IQR) 1.5 (0.5 – 3.3) month interval between studies. Among these patients, the most frequent HRM classifications included achalasia (subtypes I, II, or III) in 224 patients (42%) and normal esophageal motility in 217 patients (40%).

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics by FLIP Panometry Motility classification.

| FLIP Panometry Motility Classification | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||

| Total patient cohort | Normal | Weak | Obstruction with weak contractile response | Spastic-reactive | Inconclusive | |

|

| ||||||

| N / n (%) | 539 | 156 (29) | 28 (5) | 202 (37) | 57 (11) | 96 (18) |

|

| ||||||

| Age, mean (SD), years * | 53 (17) | 45 (15) | 55 (17) | 55 (17) | 58 (15) | 54 (16) |

|

| ||||||

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

|

| ||||||

| Gender, female * | 299 (56) | 112 (72) | 17 (61) | 84 (42) | 30 (53) | 56 (58) |

|

| ||||||

| Indication | ||||||

| Dysphagia a | 488 (91) | 128 (82) | 20 (71) | 201 (99) | 54 (95) | 85 (89) |

| Reflux symptoms | 34 (6) | 20 (13) | 6 (21) | 0 | 1 (2) | 7 (7) |

| Chest pain | 12 (2) | 8 (5) | 1 (4) | 1 (1) | 1 (2) | 1 (1) |

| Other | 5 (1) | 0 | 1 (4) | 0 | 1 (2) | 3 (3) |

|

| ||||||

| Endoscopy findings * | ||||||

| Erosive esophagitis; | ||||||

| Los Angeles Grade A / B | 18(3)/16(3) | 7 (5) / 8 (5) | 1 (4) / 3 (11) | 1 (1) / 0 | 1 (2) / 1 (2) | 8 (9) / 4 (4) |

| Non-obstructing ring | 10 (2) | 7 (5) | 1 (4) | 0 | 1 (2) | 1 (1) |

| Diverticulum | 16 (3) | 2 (1) | 0 | 7 (4) | 5 (9) | 2 (2) |

|

| ||||||

| HRM - CCv4.0 * | ||||||

| Type I achalasia | 55 (10) | 1 (1) | 0 | 43 (21) | 1 (2) | 10 (10) |

| Type II achalasia | 129 (23) | 0 | 0 | 103 (51) | 12 (21) | 14 (15) |

| Type III achalasia | 40 (7) | 0 | 0 | 23 (11) | 11 (19) | 6 (6) |

| EGJ outflow obstruction | 19 (4) | 0 | 0 | 16 (8) | 2 (4) | 1 (1) |

| Hypercontractile | 13 (2) | 1 (1) | 0 | 2 (1) | 6 (11) | 4 (4) |

| Distal esophageal spasm | 12 (2) | 3 (2) | 0 | 2 (1) | 3 (5) | 4 (4) |

| Absent contractility | 10 (2) | 2 (1) | 5 (18) | 0 | 0 | 3 (3) |

| IEM | 44 (8) | 13 (8) | 7 (25) | 5 (3) | 5 (9) | 14 (15) |

| Normal motility | 217 (40) | 136 (87) | 16 (57) | 8 (4) | 17 (30) | 40 (42) |

|

| ||||||

| HRM-EGJ-morphology * | ||||||

| Type I (no hiatal hernia) | 436 (81) | 119 (77) | 21 (75) | 180 (89) | 41 (72) | 75 (78) |

| Type II-III (hiatal hernia) | 102 (19) | 36 (23) | 7 (25) | 22 (11) | 16 (28) | 21 (22) |

P<0.001 on comparison between FLIP Panometry motility classifications.

Dysphagia +/− reflux symptoms or chest pain.

HRM – high resolution manometry; CCv4 – Chicago Classification version 4.0; EGJ - esophagogastric junction; IEM – ineffective esophageal motility.

Additionally, 35 controls, mean (SD) age 30 (6) years, 71% female were included. HRM classifications among the controls were normal motility in 32 (91%) and IEM in 3 (9%). There were also 132 patients with inconclusive HRM/CCv4.0 diagnoses, mean (SD) age 60 (15) years, 61% female (Table 3) and 16 patients with systemic sclerosis, mean (SD) age 50 (15) years, 88% female; Figure S1.

Table 3. FLIP Panometry motility classifications among patients with inconclusive Chicago Classification v4.0 (CCv4.0)/high-resolution manometry.

Patients with esophagogastric junction (EGJ) outflow obstruction (EGJOO) are described further by reason for inconclusive assignment.

| Inconclusive CCv4.0 Diagnosis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||

| Achalasia | EGJOO: Borderline TBEa | EGJOO: Normal TBE | EGJOO: Did not complete TBE | Hypercontractile esophagus or DES | |

|

| |||||

| n (%) | 7 (5) | 28 (19) | 28 (19) | 64 (43) | 5 (3) |

|

| |||||

| Age, mean (SD), years | 63 (9) | 54 (15) | 59 (15) | 61 (14) | 64 (19) |

|

| |||||

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

|

| |||||

| Gender, female | 6 (86) | 13 (46) | 23 (82) | 35 (55) | 3 (60) |

|

| |||||

| FLIP Panometry Motility Classification | |||||

| Normal | 0 | 2 (7) | 10 (36) | 8 (13) | 1 (20) |

| Weak | 0 | 1 (4) | 6 (21) | 3 (5) | 0 |

| Obstruction with weak | 5 (71) | 10 (36) | 3 (11) | 20 (31) | 0 |

| Spastic Reactive | 0 | 8 (29) | 1 (4) | 9 (14) | 2 (40) |

| Inconclusive | 2 (29) | 7 (25) | 8 (29) | 24 (38) | 2 (40) |

Timed barium esophagram (TBE) column height >5cm at 1 minute or impaction of barium tablet, but not conclusively abnormal TBE (i.e. 5-minute column height >5cm or 1-minute column height >5cm and impaction of tablet).

DES – distal esophageal spasm.

No adverse events occurred related to the FLIP study.

FLIP Panometry evaluation of asymptomatic controls

All of the controls had an EGJ-DI >3.0mm2/mmHg and maximum EGJ diameter >16mm yielding an EGJ classification of NEO. All of the controls had antegrade contractions: 31 (89%) had normal CR and 4 (11%) had borderline CR. Of the 3 controls with IEM on HRM, two had a normal CR and one had borderline CR. All of the controls had a FLIP Panometry motility classification of normal motility.

FLIP Panometry evaluation of patients

Among the patient cohort, the FLIP Panometry classifications of EGJ opening included 187 patients (35%) with NEO, 57 (11%) patients with BnEO, 54 patients (10%) with BrEO), and 241 patients with REO (45%), Table S2. 99.5% of patients with NEO had normal EGJ outflow per HRM/CCv4.0 and 85.9% of patients with REO had a disorder of EGJ outflow per HRM/CCv4.0 (Table S2)

FLIP Panometry CR patterns included 94 patients with normal CR (17%), 97 patients with borderline CR (18%), 119 patients with impaired/disordered CR (22%), 172 patients with absent CR (32%), and 57 patients with spastic-reactive CR (11%). None of the patients with achalasia had NCR.

Classification of FLIP Panometry motility in patients

The associations of FLIP Panometry EGJ opening and CR pattern with HRM/CCv4.0 diagnosis are shown in Figures 3 and 4. Among the patient cohort, the FLIP Panometry classifications of esophageal motility (defined in Figure 2) were of normal motility (NEO with normal CR or borderline CR) in 29%, weak motility (NEO with absent CR or impaired/disordered CR) in 5%, obstruction with weak CR (REO with absent CR or impaired/disordered CR) in 37% and spastic-reactive in 11%; Table 2. 18% of the cohort (96 patients) had an inconclusive FLIP Panometry motility classification (BrEO, BnEO, or REO with borderline CR). No patients in this cohort evaluated for primary esophageal motility disorders (i.e. with presence of overt mechanical esophageal obstruction as an exclusion criterion) had a FLIP Panometry motility classification of obstruction with normal CR (REO and normal CR). Differences in clinical characteristics among the FLIP Panometry motility classifications included less frequent indication of dysphagia (and more frequent indication of reflux symptoms) in classifications of normal and weak than in obstruction with weak CR. Mild reflux esophagitis (Los Angeles grade A or B) was also more frequently observed in normal or weak FLIP Panometry than in obstruction with weak CR. Hiatal hernia (on HRM) was least frequently observed in obstruction with weak CR.

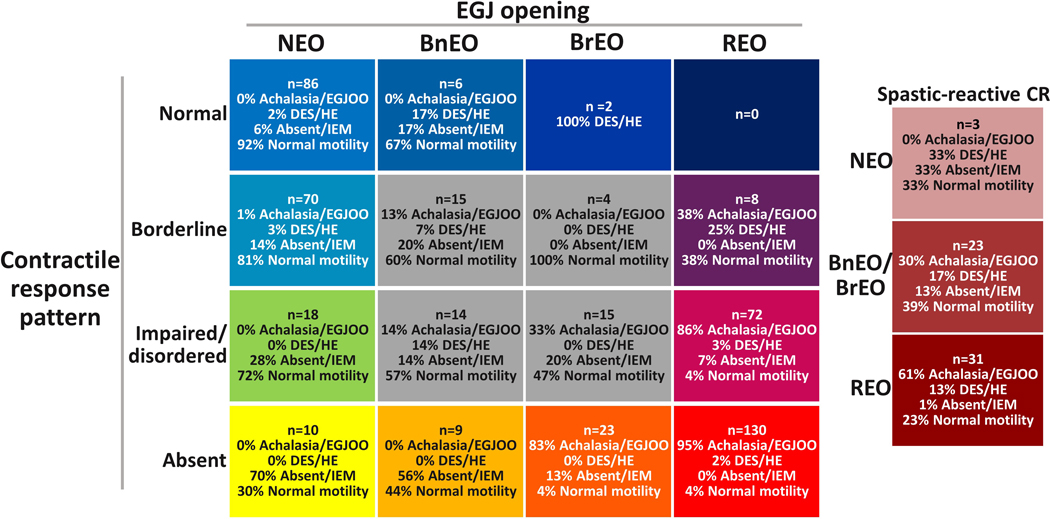

Figure 3. Association between FLIP Panometry findings and Chicago Classification v4.0 (CCv4.0) high-resolution manometry (HRM) diagnoses.

The number of patients (n) and associated diagnoses per CCv4.0 are shown in each box. EGJ – esophagogastric junction; EGJOO - EGJ outflow obstruction. DES – distal esophageal spasm. HE – hypercontractile esophagus. IEM – ineffective esophageal motility. REO – reduced EGJ opening. BrEO – borderline reduced EGJ opening. BnEO – borderline normal EGJ opening. NEO – normal EGJ opening. CR – contractile response. Figure used with permission from the Esophageal Center of Northwestern.

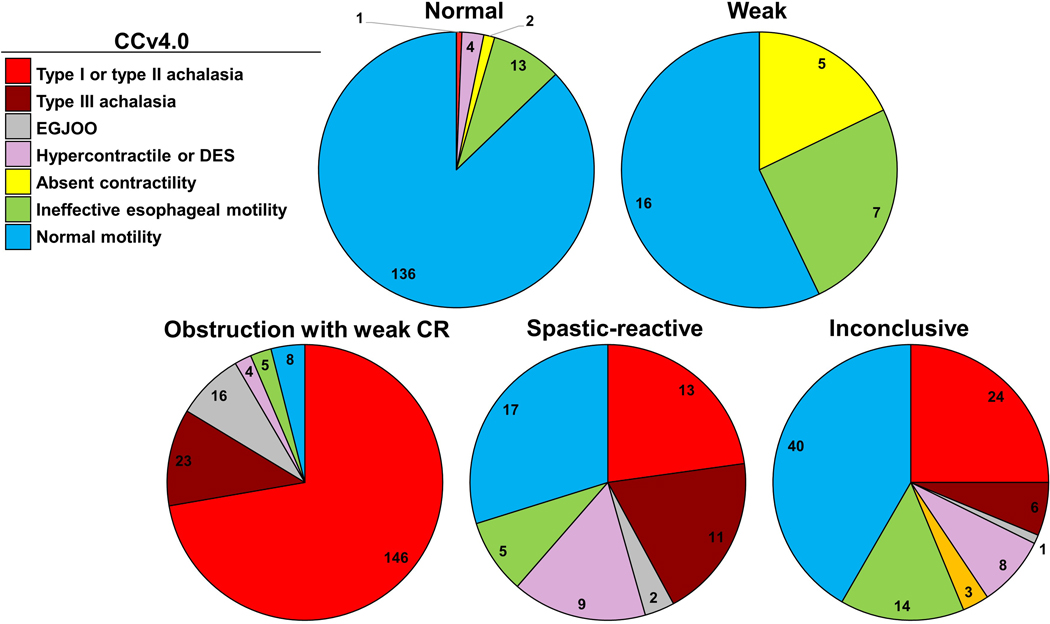

Figure 4. Chicago Classification version 4.0 (CCv4.0) diagnoses among FLIP Panometry motility classifications.

Each pie chart represents a FLIP Panometry motility classification with proportions of conclusive CCv4.0 diagnoses (which are grouped by similar features for display purposes). Data labels represent number of patients. EGJOO - EGJ outflow obstruction. DES – distal esophageal spasm. CR – contractile response. Figure used with permission from the Esophageal Center of Northwestern.

Among the 156 patients with normal motility on FLIP Panometry, 95% had a CCv4.0 classification of normal motility (87%) or IEM (8%); Table 2 and Figure 4. One patient with normal motility on FLIP had type I achalasia based on strict application of CCv4.0 – the IRP values were borderline (median supine IRP 17mmHg, median upright IRP 12mmHg) and a peristaltic wave was observed after a dry swallow and after multiple rapid swallows on HRM. Among the 28 patients with weak FLIP Panometry, 57% had normal motility on HRM, while the remainder had absent contractility or IEM.

Of the 202 patients with obstruction with weak CR, 92% had a CCv4.0 disorder of EGJ outflow (achalasia or EGJOO) and 84% had achalasia (subtypes I, II, or III); Table 2. There were 13 patients (7% of 202) with normal motility or IEM on HRM and obstruction with weak CR on FLIP Panometry: 7 completed TBE, 2 of which had 5 minute column heights >5cm and 2 others had lesser degrees of barium retention (5 minute column of 3cm and 2 minute column of 16cm that cleared by 5 minutes), the other 3 TBEs were normal. Additionally, 7 (54%) of these patients had a hiatal hernia.

A spastic-reactive FLIP Panometry was observed in 11/40 (28%) type III achalasia, 4/13 (31%) hypercontractile esophagus, and 3/12 (25%) distal esophageal spasm. Of the 22 patients with normal motility or IEM on HRM and spastic-reactive FLIP Panometry, two had an epiphrenic diverticulum, 11 (50%) had a hiatal hernia, and 8 completed TBE: 2/8 TBEs had barium retention at 1 minutes that cleared by 2 minutes and passage of the barium tablet. The other 6/8 TBEs were normal.

Among the inconclusive FLIP Panometry motility classification, 30 patients (31%) had achalasia: 26 (87%) of those 30 patients had BrEO or REO, while 4 (13%) had BnEO (Figure 3). Further, 83% (19/23 patients) with BrEO and absent CR had achalasia while zero patients with BnEO and absent CR had achalasia (Figure 3). There were 48 patients with BrEO or BnEO and borderline CR or impaired/disordered CR, 19% (n=9) had achalasia and 58% (n=28) had normal motility on HRM.

FLIP Panometry findings in patients with inconclusive CCv4.0 diagnoses and systemic sclerosis

Patients with inconclusive HRM/CCv4.0 diagnoses are described in Table 3. Of the 120 patients with inconclusive EGJOO, 64 (53%) did not complete a TBE. Among the inconclusive EGJOO that did complete TBE, 10/13 patients (77%) with FLIP Panometry of obstruction with weak CR had ‘borderline’ TBE abnormalities (i.e. column height >5cm at 1 minute or impaction of barium tablet, but not a conclusively abnormal TBE with 5-minute column height >5cm or 1-minute column height >5cm and impaction of tablet), while 3/13 (23%) had a normal TBE. Further, 10/12 patients (83%) with a FLIP Panometry classification of normal motility had a normal TBE, while 2/12 (17%) had borderline TBE abnormalities. 39 of 120 (33%) patients with inconclusive-EGJOO per CCv4.0 had an inconclusive FLIP Panometry classification.

Among 16 patients with systemic sclerosis, FLIP Panometry was normal motility in 6 patients (38%), weak in 8 (50%) patients, and inconclusive in 2 (13%) patients. Included were two patients that had absent contractility with elevated IRP (i.e. type I achalasia per strict application of CCv4.0) that had NEO and weak FLIP Panometry; neither of these patients were treated clinically as achalasia.

Discussion

Our findings based on this study of a prospective cohort of 539 symptomatic patients and 35 asymptomatic healthy controls support that FLIP Panometry can effectively classify esophageal motility in a way that parallels the motility evaluation with HRM and CCv4.0. A classification of normal motility on FLIP Panometry (NEO with normal CR or borderline CR) included 95% of patients with an HRM/CCv4.0 diagnosis of normal motility (87%) or IEM (8%). On the other hand, a classification of obstruction with weak CR on FLIP Panometry (REO with absent CR or impaired/disordered CR) included 92% of patients with a HRM/CCv4.0 diagnosis of a disorder of achalasia or conclusive EGJ outflow obstruction. Therefore, FLIP Panometry findings can be applied during an index endoscopy to accurately classify esophageal motility. Additionally, the FLIP Panometry findings can bolster a preexisting motility evaluation to support or clarify the overall clinical impression, especially if initial motility (HRM) results were inconclusive. In either scenario, the FLIP Panometry evaluation of esophageal motility can facilitate clinical diagnosis to direct management or triage for additional clinical evaluation.

The initial descriptions of esophageal motility with FLIP Panometry reported the association between FLIP Panometry and HRM classification according to the CC version 3.0.2, 22 The present study reported an update to the FLIP Panometry esophageal motility classification to reflect advances over the past several years, such as the dual-metric EGJ opening assessment and updates to the FLIP Panometry CR patterns (e.g. RAC Rule-of-6s; sustained occluding contractions; Table 1).12, 13, 18, 23, 24 Further, a limitation of our initial assessments of the FLIP Panometry motility classification was the reliance on HRM classifications that, beyond achalasia, may not reflect conclusive and/or clinically relevant diagnoses.4, 6 The present study, however, applied the recently updated CCv4.0 that addressed those limitations.4 A notable update in CCv4.0 includes the recognition that the HRM impression may be inconclusive and testing beyond HRM (TBE or FLIP) may be necessary to clarify the clinical impression. For this study, we applied strict CCv4.0 criteria independent of FLIP to reach conclusive clinical motility diagnosis. This included utilizing TBE to reach a conclusive classification when the HRM was classified as EGJOO. Overall, the clinical relevance of the FLIP Panometry classification scheme was evident with its ability to both detect patients with achalasia as well as demonstrate a low probability of major motor disorders among patients classified as normal motility on FLIP Panometry.

Similar to the approach taken by the CCv4.0 in recognizing that a confident clinical diagnosis may not be achieved with a single motility test, an inconclusive classification was applied to FLIP Panometry motility findings to reflect situations in which additional testing (e.g. HRM and/or TBE) should be obtained. An inconclusive FLIP Panometry classification was reached in 18% of this cohort; also noting that 19% of patients had an inconclusive HRM/CCv4.0 (Figure S1). However, there still appeared to be predictive value provided by the FLIP Panometry findings that may be inconclusive in isolation (Figure 3). For example, FLIP Panometry with absent CR and BrEO would be supportive (even if not independently conclusive) for achalasia. Along these lines, while the FLIP Panometry spastic-reactive classification was frequently observed in patients with abnormal diagnoses per CCv4.0, there was heterogeneity of CCv4.0 motility diagnoses, as well as a potential relationship to hiatal hernia. Thus, while the spastic-reactive classification represents an abnormal esophageal response to distension, these patients should be further evaluated with HRM and/or esophagram (Figure 5). This may facilitate tailoring of myotomy, e.g. if type III achalasia is identified, or demonstrate abnormal anatomy with related LES reactivity.12

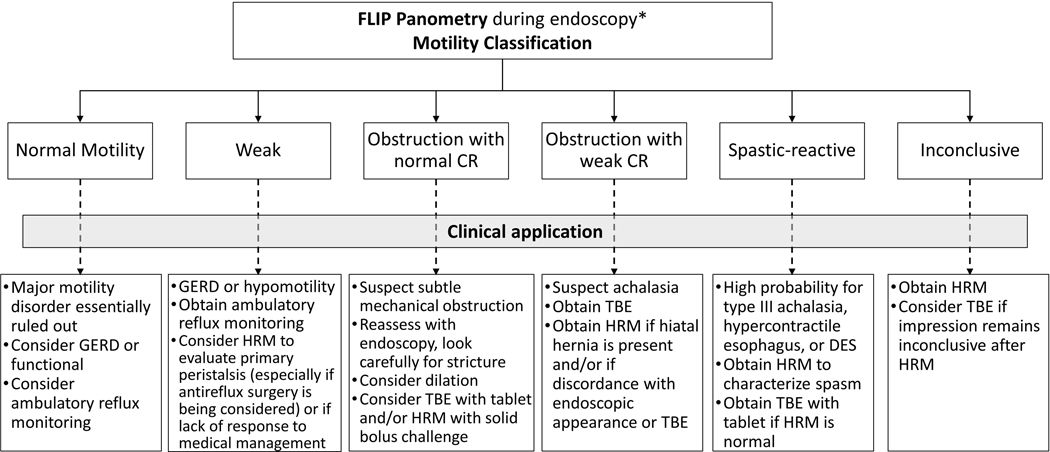

Figure 5. Clinical application of FLIP Panometry findings.

*The FLIP Panometry motility classification is intended for clinical scenarios in which findings associated with secondary esophageal motor abnormalities, such as large hiatal hernia, stricture, or previous foregut surgery, are excluded based on endoscopy and clinical history. GERD – gastroesophageal reflux disease. HRM – high resolution manometry. TBE – timed barium esophagram. DES – distal esophageal spasm. CR – contractile response.

Ultimately, FLIP Panometry findings should be clinically applied in the context of existing clinical data (e.g. endoscopic findings, clinical presentation, TBE). In scenarios in which a high pretest probability for a clinical diagnosis exists, a single confirmatory test with FLIP Panometry (or HRM) may be sufficient to treat if a clinical diagnosis can be confidently achieved (Figure 5). Thus, with a FLIP Panometry of normal motility and a low probability for major motor disorder, or a FLIP Panometry with obstruction with weak CR and a supportive TBE, targeted treatment could be pursued without needing HRM. However, if diagnostic uncertainty exists after an initial diagnostic evaluation, e.g. FLIP Panometry findings that are discordant with other data (e.g. endoscopic appearance of EGJ), additional clinical correlation with complementary tests (HRM and esophagram) should be pursued. While improvement in the predictive capabilities of the FLIP Panometry findings is anticipated from ongoing work, such as applying probabilistic modeling using machine learning techniques, the presently reported classification scheme provides guidance for application of the FLIP Panometry motility evaluation in the current paradigm. This classification scheme may also provide a framework for research labels to facilitate future studies, hopefully across multiple centers.

The uncertainty associated with inconclusive CCv4.0 classifications limited the utilization of these studies as this comparison study required conclusive diagnoses from which to objectively evaluate the FLIP Panometry motility classification. However, FLIP Panometry appeared to track with TBE findings (when available) among these patients. Ultimately, future study to further evaluate the application of FLIP Panometry to patients with inconclusive HRM classifications remains needed and is a focus of ongoing work. Further, although concordance between motility assessments with FLIP Panometry and HRM was the dominant observation, discordance between the two tests was also observed. Because FLIP and HRM evaluate different components of esophageal function (i.e. esophageal response to distension versus esophageal response to swallows), discordance between FLIP Panometry and HRM should at times be expected, just as differences in primary and secondary peristalsis on manometry were observed in previous studies.9, 10 In some cases, FLIP Panometry appeared to detect abnormalities that were not detected by HRM/CCv4.0, such as patients with normal motility on HRM but abnormal FLIP Panometry and significant retention on TBE or epiphrenic diverticula. Ultimately, in some scenarios (such as those with borderline or equivocal findings) HRM and FLIP will likely be best applied as complementary studies and there may be diagnostic value in both concordant and discordant findings. Discordant findings, however, may require arbitration with TBE.

While this study carries strengths related to application of a rigorous evaluation utilizing CCv4.0 on a large cohort of comprehensively evaluated patients, as well as asymptomatic controls, there are some limitations as well. The composition of the patient cohort reflects a referral bias (quaternary referral center for esophageal motility disorders), and there is potential for a selection bias related to when FLIP was utilized. Thus patients with achalasia are overrepresented in the study cohort that also predominantly includes patients evaluated with dysphagia. While this may somewhat limit direct generalizability of these results to other clinical practices, an achalasia diagnosis represents the most important outcome of an esophageal motility evaluation thus making description of FLIP Panometry findings extremely valuable. Future studies to evaluate the FLIP Panometry motility evaluation among other patient cohorts (e.g. GERD patients) remains warranted to further establish the role of FLIP in these other patient populations. Additionally, while this study focused on establishing a classification scheme to facilitate future studies and clinical application, this work did not assess for longitudinal clinical outcomes or treatment response – such work remains needed and is also the focus of ongoing work, particularly related to patients with inconclusive HRM diagnoses such as EGJOO.

In conclusion, evaluation of esophageal motility via FLIP Panometry accurately identified esophageal motility disorders, including achalasia. Because FLIP Panometry is performed at the time of the sedated endoscopy, this assessment can be applied to improve the diagnostic yield of endoscopy and direct immediate intervention (such as dilation), or direct need for additional complementary evaluation, such as if FLIP Panometry is inconclusive (Figure 5). FLIP Panometry may offer a viable alternative to HRM when patients have normal FLIP exams or if they are unable to tolerate catheter placement. FLIP Panometry reflects a novel technology and its analysis paradigm will continue to evolve based on expanded experience and future investigation, akin to HRM and the Chicago Classification updates. Future development of machine learning applications in particular, such as those that are incorporated into real-time analysis software, will be beneficial to provide clinical decision support at the time of the clinical encounter. Overall, this study demonstrates the clinical utility of the evaluation of esophageal motility via FLIP Panometry and further supports its value for the diagnosis of esophageal motility disorders.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Grant support: This work was supported by P01 DK117824 (JEP) from the Public Health service and American College of Gastroenterology Junior Faculty Development Award (DAC).

Footnotes

Disclosures:

JEP, PJK, and Northwestern University hold shared intellectual property rights and ownership surrounding FLIP Panometry systems, methods, and apparatus with Medtronic Inc.

DAC: Medtronic (Speaking, Consulting); Phathom Pharmaceuticals (Consulting)

CPG: Medtronic, Diversatek, Ironwood, IsoThrive, Quintiles (consulting); Takeda (Speaking)

AK: Medtronic (Speaking, Consulting)

RY: Medtronic (consultant; Institutional), Ironwood Pharmaceuticals (consultant; Institutional), Phathom Pharmaceuticals (consultant; Institutional); Ironwood Pharmaceuticals (Research Support); RJS Mediagnostix (Advisory Board with stock options)

JOC: Medtronic (consulting); Alnylam (consulting); Sanofi (consulting)

JMG: Medtronic (Speaking, Consulting), Abbott (Speaking), Biogaia (Speaking)

PK: Phathom Pharmaceuticals (Consulting)

VK: Exact Sciences (Advisory Board); Lucid (Research); Medtronic (Consulting)

SJS: Interpace Diagnostics (Consulting), Cernostics (Consulting), Phathom Pharmaceuticals (Consulting), ISOThrive (Consulting), and Ironwood Pharmaceuticals (Consulting); UpToDate (royalties).

MV: Medtronic (consultant), Diversatek (research support)

PJK: Ironwood (Consulting); Reckitt Benckiser (Consulting)

JEP: Sandhill Scientific/Diversatek (Consulting, Speaking, Grant), Takeda (Speaking), Astra Zeneca (Speaking), Medtronic (Speaking,Consulting, Patent, License), Torax (Speaking, Consulting), Ironwood (Consulting)

JChen, RVC, ASJ, KL, FHSS, JEPrescott; AJB; END; WK: none

References

- 1.Carlson DA, Lin Z, Rogers MC, Lin CY, Kahrilas PJ, Pandolfino JE. Utilizing functional lumen imaging probe topography to evaluate esophageal contractility during volumetric distention: a pilot study. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2015;27(7):981–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carlson DA, Kahrilas PJ, Lin Z, et al. Evaluation of Esophageal Motility Utilizing the Functional Lumen Imaging Probe. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111(12):1726–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gyawali CP, Carlson DA, Chen JW, Patel A, Wong RJ, Yadlapati RH. ACG Clinical Guidelines: Clinical Use of Esophageal Physiologic Testing. Am J Gastroenterol. 2020;115(9):1412–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yadlapati R, Kahrilas PJ, Fox MR, et al. Esophageal motility disorders on high-resolution manometry: Chicago classification version 4.0((c)). Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2021;33(1):e14058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pandolfino JE, Ghosh SK, Rice J, Clarke JO, Kwiatek MA, Kahrilas PJ. Classifying esophageal motility by pressure topography characteristics: a study of 400 patients and 75 controls. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103(1):27–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kahrilas PJ, Bredenoord AJ, Fox M, et al. The Chicago Classification of esophageal motility disorders, v3.0. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2015;27(2):160–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Hoeij FB, Smout AJ, Bredenoord AJ. Characterization of idiopathic esophagogastric junction outflow obstruction. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2015;27(9):1310–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schupack D, Katzka DA, Geno DM, Ravi K. The clinical significance of esophagogastric junction outflow obstruction and hypercontractile esophagus in high resolution esophageal manometry. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2017;29(10):1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schoeman MN, Holloway RH. Secondary oesophageal peristalsis in patients with non-obstructive dysphagia. Gut. 1994;35(11):1523–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schoeman MN, Holloway RH. Integrity and characteristics of secondary oesophageal peristalsis in patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Gut. 1995;36(4):499–504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Savarino E, di Pietro M, Bredenoord AJ, et al. Use of the Functional Lumen Imaging Probe in Clinical Esophagology. Am J Gastroenterol. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Carlson DA, Baumann AJ, Donnan EN, Krause A, Kou W, Pandolfino JE. Evaluating esophageal motility beyond primary peristalsis: Assessing esophagogastric junction opening mechanics and secondary peristalsis in patients with normal manometry. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2021:e14116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Carlson D, Baumann AJ, Prescott J, et al. Validation of secondary peristalsis classification using FLIP Panometry in 741 subjects undergoing manometry. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2021: epub Jun 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Carlson DA, Prescott JE, Baumann AJ, et al. Validation of clinically relevant thresholds of esophagogastric junction obstruction using FLIP Panometry. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021; epub Jun 30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Carlson DA, Kou W, Lin Z, et al. Normal Values of Esophageal Distensibility and Distension-Induced Contractility Measured by Functional Luminal Imaging Probe Panometry. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;17(4):674–81 e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kraichely RE, Arora AS, Murray JA. Opiate-induced oesophageal dysmotility. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;31(5):601–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mittal RK, Frank EB, Lange RC, McCallum RW. Effects of morphine and naloxone on esophageal motility and gastric emptying in man. Dig Dis Sci. 1986;31(9):936–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carlson DA, Kou W, Rooney KP, et al. Achalasia subtypes can be identified with functional luminal imaging probe (FLIP) panometry using a supervised machine learning process. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2020:e13932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.de Oliveira JM, Birgisson S, Doinoff C, et al. Timed barium swallow: a simple technique for evaluating esophageal emptying in patients with achalasia. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1997;169(2):473–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bredenoord AJ, Babaei A, Carlson D, et al. Esophagogastric junction outflow obstruction: Technical Note. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2021;epub June 12. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Blonski W, Kumar A, Feldman J, Richter JE. Timed Barium Swallow: Diagnostic Role and Predictive Value in Untreated Achalasia, Esophagogastric Junction Outflow Obstruction, and Non-Achalasia Dysphagia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113(2):196–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carlson DA, Gyawali CP, Kahrilas PJ, et al. Esophageal motility classification can be established at the time of endoscopy: a study evaluating real-time functional luminal imaging probe panometry. Gastrointest Endosc. 2019;90(6):915–23 e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baumann AJ, Donnan EN, Triggs JR, et al. Normal Functional Luminal Imaging Probe Panometry Findings Associate With Lack of Major Esophageal Motility Disorder on High-Resolution Manometry. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;19(2):259–68 e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carlson DA, Kou W, Pandolfino JE. The rhythm and rate of distension-induced esophageal contractility: A physiomarker of esophageal function. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2020:e13794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.