Abstract

The purpose of this exploratory analysis was to compare the impact of movement pattern training (MoveTrain) and standard strength and flexibility training (Standard) on muscle volume, strength and fatty infiltration in patients with hip-related groin pain (HRGP). We completed a secondary analysis of data collected during an assessor-blinded randomized control trial. Data were used from 27 patients with HRGP, 15–40 years, who were randomized into MoveTrain or Standard groups. Both groups participated in their training protocol (MoveTrain, n = 14 or Standard, n = 13) which included 10 supervised sessions over 12 weeks and a daily home exercise program. Outcome measures were collected at baseline and immediately after treatment. Magnetic resonance images data were used to determine muscle fat index (MFI) and muscle volume. A hand-held dynamometer was used to assess isometric hip abductor and extensor strength. The Standard group demonstrated a significant posttreatment increase in gluteus medius muscle volume compared to the MoveTrain group. Both groups demonstrated an increase in hip abductor strength and reduction in gluteus minimus and gluteus maximus MFI. The magnitude of change for all outcomes were modest.

Keywords: buttocks, fatty infiltration, hip-related groin pain, strength, volume

1 |. INTRODUCTION

Hip-related groin pain (HRGP) presents clinically in young adults with a gradual onset of moderate to severe groin pain. Individuals with HRGP are at higher risk for developing osteoarthritis (OA),1–3 ultimately leading to increased pain, economic burden, and decreased quality of life.4 Patients with HRGP have significant weakness in the gluteus medius (Gmed), gluteus minimus (Gmin) and gluteus maximus (Gmax),5–8 muscles that are important for the stability of the hip joint during dynamic tasks.9 Weakness is often related to muscle atrophy, but there is limited and conflicting evidence regarding hip muscle volume in this population.7,10 In our previous work,7 we noted that patients with HRGP displayed weaker, but larger hip abductors compared to asymptomatic participants, suggesting that pathways other than muscle atrophy may contribute to hip muscle weakness. Additionally, we know little about the specific effects of exercise on hip muscle structure and function among those with HRGP.

Fat accumulation within the muscle may increase volume while limiting the ability of contractile units to generate force.11 Currently, we do not know if fatty infiltration is greater among patients with HRGP compared to asymptomatic people, however a recent systematic review suggests that, in general, fatty infiltration is greater among patients with a health condition, such as soft tissue impairments, inflammatory disease and mobility impairments, compared to healthy individuals.12 Specific to musculoskeletal conditions, excessive fatty infiltration has been displayed in musculature of patients with cervical pain due to whiplash,13 low back pain,14 greater trochanteric pain syndrome15 and hip OA.3,16–19 Although the mechanism underlying each of these health conditions differ, it is possible the presence of chronic HRGP is associated with fat accumulation in the musculature surrounding the painful joint and therefore a potential target for treatment.

Fatty infiltration can be reduced with strength training,20–22 but this has not been explored in patients with HRGP. Previous treatment studies involving musculoskeletal conditions such as knee OA, postanterior cruciate ligament repair and HRGP, focusing on improving neuromuscular control and altering movement patterns during prescribed exercises, have reported improvements in movement quality,23–27 pain, and function,23,24,26 yet we know little about the effect of these exercises on muscle structure. In this project, we were able to leverage an existing dataset to investigate change in muscle volume and fatty infiltration among patients with HRGP participating in either strength training or movement pattern training.

We previously completed a randomized clinical trial (RCT) to compare movement pattern training (MoveTrain) to a standard strengthening and flexibility program (Standard) on patient-reported pain and function.28 Task-specific training, commonly used in the treatment of neurological conditions, uses repeated practice of functional tasks. MoveTrain incorporates task-specific training, targeting specific activities that each patient identifies as those activities in which they have difficulty performing due to their hip pain. In addition to task performance, MoveTrain includes instruction in how to modify movement patterns displayed during task performance, that are associated with the patient’s pain. As an example, a patient who reports difficulty with stair ambulation will practice going down a step while focusing on their quality of movement. One of the common impairments noted and modified during the step down is excessive hip adduction. While MoveTrain has been shown to improve movement quality, reduce pain and improve patient-reported function, there is conflicting evidence as to whether or not this training approach increases muscle strength24,26 and no evidence regarding its impact on muscle fatty infiltration.

The etiology of weakness and increased volume in the hip musculature of HRGP remains unknown, as does the impact of different exercise on these impairments. It is possible that muscle atrophy, increased fatty infiltration, and impaired neuromuscular control all play a role. This study was an exploratory analysis using data from a subset of patients who participated in our multicenter RCT to compare the treatment effects of MoveTrain to Standard. We collected magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) from patients recruited at one of the sites to assess change in muscle volume, strength, and fatty infiltration in patients with HRGP. We hypothesized that both groups would display increased muscle volume and strength, and decreased fatty infiltration after treatment. We, however, believed Standard would have significantly greater change than MoveTrain due to greater evidence supporting significant increases in muscle strength and volume29–31 and reduction of muscle fatty infiltration21,22 after progressive loading in other populations.

2 |. METHODS

2.1 |. Study design overview

This study is a secondary analysis using data from a pilot multicenter RCT comparing two interventions for patients with HRGP (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT02913222).28 The original RCT was designed with 23 participants per group to achieve 80% statistical power to detect a minimal effect size of 0.9 at posttreatment, and 46 participants were enrolled. The primary findings of the parent study have been reported.28 We received additional funding that allowed us to collect MRI for participants (n=30) at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis. MRI data were available from 27 of the 30 participants for our analysis. This study was approved by the Human Research Protection Office at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis and University of Pittsburg. All patients signed an informed consent statement before participation.

2.2 |. Participants

Participants were recruited from the community between January 2017 and February 2018, from volunteer research databases, advertisements through flyers and social media, and local physician and physical therapy clinics. Inclusion criteria included: (1) aged 15–40 years, (2) reported deep hip joint or anterior groin pain that could be reproduced with Flexion, Adduction, Internal Rotation test,32 (3) pain had to be present for at least 3 months and rate at least 3/10, and (4) report functional limitation represented by a modified Harris Hip Score <90. Exclusion criteria included: (1) previous hip surgery, fracture, infection, (2) pain related to high impact trauma, (3) diagnosis of Legg-Calve-Perthes Disease or slipped capital femoral epiphysis or inflammatory disease, (4) neurologic involvement affecting balance, (5) radiating pain, numbness or tingling into the thigh, (6) pregnancy, and (7) screening tests indicating pain is being referred pain from the spine.

2.3 |. Interventions

After completion of baseline assessment, patients were randomized into either MoveTrain or Standard, using a variable block size.28 For randomization, patients were stratified by study site, sex, and Hip disability and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (HOOS) Symptoms subscale. Both groups participated in 10 supervised sessions over 12 weeks and completed a daily home exercise program (HEP).

MoveTrain intervention group focused on task-specific training that included repeated practice of daily tasks, such as sit to stand, stairs, and forward bending and patient-specific tasks, such as fitness, work or leisure-related tasks. During task performance, individuals were cued to reduce hip adduction, internal rotation and extreme hip and knee extension. Exercises for the HEP included practice of the same tasks practiced in the supervised sessions. The physical therapist progressed the HEP by adjusting the number of repetitions, increasing load or speed, removing visual and verbal cueing, or changing support surfaces once the patient was able to perform 25 repetitions without fatigue and with the movement modifications.

The Standard treatment focused on progressive lower extremity and trunk strengthening and lower extremity flexibility. Isolated strengthening exercises were performed for hip abductors, extensors, flexors, adductors, internal and external rotators as well as trunk musculature. Stretching was performed for hip flexors, plantarflexors, hamstrings and piriformis. All exercises were progressed by increasing repetitions performed or load once participants were able to complete three sets of 8–10 repetitions for lower extremity strengthening exercises, or three sets of 60 s for trunk strengthening exercises. Stretches were held for 30 s, for two to four repetitions. Detailed descriptions of interventions provided in MoveTrain and Standard has been previously published.28

2.4 |. Outcome variables

Outcomes were collected at baseline and after treatment completion. Patients completed self-report questionnaires to collect demographic information and patient-reported outcome measures including the HOOS33 and the University of California Los Angeles activity score.34 The hip to be studied was identified at baseline assessment as either the symptomatic hip, for those with unilateral pain, or the patient-identified most bothersome hip, for those with bilateral pain. All personnel participating in data collection and measurement were blinded to treatment group.

Hip extensor and abductor muscle strength was assessed using a microFET3 hand-held dynamometer (Hogan Health Industries). To assess hip extensor strength, the patient was positioned in prone with the hip in 30° flexion, 0° abduction/adduction and 0° internal/external rotation, and the knee in 0° flexion. To assess hip abductor strength, the patient was positioned in side lying with the hip in 0° flexion, 0° abduction/adduction and 0° internal/external rotation, and the knee 0° flexion. Isometric strength tests35 were performed using straps for resistance. For each test, the dynamometer was place on a predefined location on the limb and a strap that was attached to the dynamometer was secured to the table. The patient was then instructed to push into the dynamometer with the following cues, “I’m going to say ready and go, when you hear the word go, gradually build up your force until you are pushing as hard as you can.” Each participant was allowed one practice trial, then the force of the three maximal trials were averaged and used to calculate torque. All measurements were conducted by one clinician with over 23 years of experience.

Hip muscle volume and proportion of fat within the muscle was assessed using MRI. A research-dedicated 3.0-Tesla superconducting magnet (Siemens) was used to acquire images of the pelvis. Patients were positioned supine with their hips at 0° of flexion/abduction/rotation. A spine coil and a body matrix coil overlying the pelvis were used during imaging. Spacers and straps were used to secure coils and maintain lower extremity position during acquisition. Scout images were used to determine capture volume, followed by the 3D, T1 VIBE-DIXON sequence, centered at the pelvis, using the following parameters: slice thickness: 1.1mm, repetition time, 5.48ms; echo time, 2.45ms; field of view, 480mm; 480×480 matrix; total acquisition time being approximately 7min. Following acquisition, 3D distortion correction was performed and images saved to a secure server.

To optimize reliability of the measures, one research assistant completed all segmentations. Images were downloaded from the server to a desktop computer and imported into ITK-Snap 3.6 Software. The Gmed, Gmin, and Gmax were measured individually, every other slice, in the transverse plane using the software’s polygon and free-hand drawing tools to create a mask. Each muscle was measured from its initial appearance starting at the superior portion of the iliac crest to the superior aspect of the femoral head. Muscle borders distal to the superior border of the femoral head were difficult to distinguish,36 so a decision was made to anchor the distal segmentation at this point (Figure 1). An interpolation tool was used to merge the individually outlined muscle borders for more efficient full muscle volume measures. Each muscle was individually reviewed in frontal, transverse, and sagittal planes.

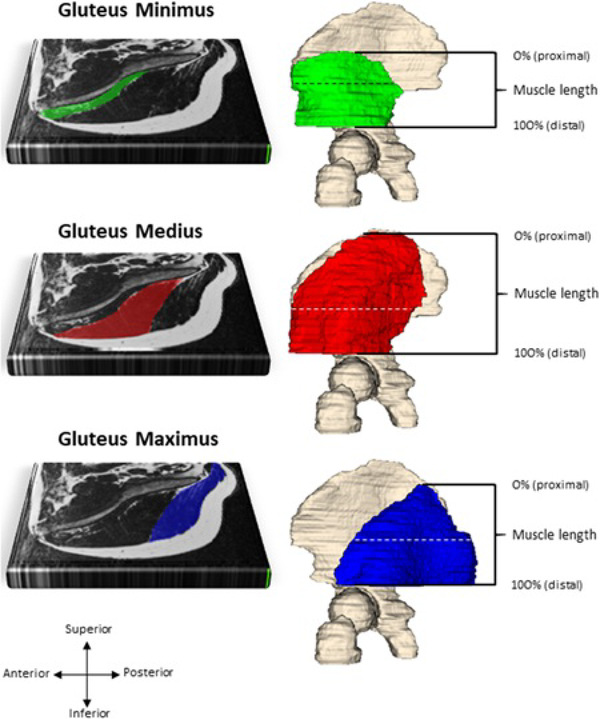

Figure 1.

Gluteus minimus (green), gluteus medius (red) and gluteus maximus (blue) segmentation represented on one transverse slice, at the level of the horizontal dashed line. Fat within a muscle is illustrated by the white striations. Muscle lengths were normalized across participants from 0% (proximal) to 100% (distal)

To assess intra-rater reliability, the research assistant determined muscle volume on 10 participants on two separate occasions, greater than 3 months apart. Test-retest reliability was excellent (Intraclass Correlation (ICC3,1 [95% confidence interval]=0.99 [0.99, 0.99]), SE of measurement (3.4cm3).

A muscle fat index (MFI) was calculated to represent the proportion of fat within a muscle. The DIXON sequence enables collection of data required for the analysis of phase related to the precessional differences in fat and water.37 For each participant, NIFTI files (Neuroimaging Informatics Technology Initiative) were generated for fat-only images, water-only images, and the masks, and loaded into the R statistical software package (version 4.0.2). The ‘neurobase’ R package (version 1.29.0) was used to extract pixel intensity values from the fat only images and the water only images, using the regions of interests that were defined in the masks for each muscle. These values were then used to calculate the MFI using the following equation, as has been done previously.38–40

To be able to analyze fat across the entire length of the muscle (from proximal to distal, see Figure 1), muscle length was normalized so that 0% represented the most proximal slice and 100% represented the most distal slice. Mean MFI within every slice was then represented at every 1% of muscle length using spline interpolation. Previous research indicates that GMin and GMed consist of structurally and functionally unique segments.41 Therefore, GMin and GMed were segmented into two (anterior, posterior) and three (anterior, middle, and posterior) portions respectively, by dividing the muscle equally along a line drawn in the coronal plane. GMax was not partitioned.

2.5 |. Statistical approach

Muscle strength and volume data collected at pretreatment and posttreatment were analyzed with a repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA). Where assumptions were violated, a nonparametric ANOVA was used. Statistical nonparametric mapping (SnPM) was used to test if differences in muscle fat proportions (MFI) over time, depended on group allocation (open-source spm1d code [SPM spm1d version 0.4; http://www.spm1d.org]).42,43 Analysis using SnPM calculates the scalar output statistic, or “t” statistic for each 1% of muscle length. Differences in MFI can then be determined between groups, or time, over the entire length of the muscle using one test and can also identify the location that these differences occur within the muscle. This technique is more advantageous than selecting random cross sections of muscle to analyze, and testing multiple levels with separate statistical tests, which would ultimately increase the likelihood of a Type 1 error. A nonparametric mixed-ANOVA was performed within the SnPM framework using Python 2.7 using Canopy 2.1.9 (Enthought Inc.). Significant interaction effects were followed up with nonparametric paired t tests, stratified by group. In the absence of interaction effects, main effects of group (independent) or time (repeated) were reported. Effect sizes (ES) were determined by dividing the t-statistic by the square root of the sample size. ES of 0.2, 0.5, and 0.8 were considered small, moderate, and large respectively.44 An alpha of .05 was considered the threshold for significance.

3 |. RESULTS

Thirty participants were enrolled at the (Facility blinded for review) site. MRI was not available for one participant who did not tolerate the MRI, and MRI data for two participants were excluded due to poor quality scans. Of the remaining 27, 14 participants were randomized to MoveTrain, and 13 were randomized to Standard. Demographics are provided in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Demographics and baseline characteristics

| Variable | By Treatment Group | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| MoveTrain n = 14 |

Standard n = 13 |

P Value | |

|

| |||

| Sex, n (%) | |||

| Male | 6 (43%) | 5 (38%) | |

| Female | 8 (57%) | 8 (62%) | .201* |

|

| |||

| Age (year), mean ± SD | 27.4 ± 4.9 | 29.2 ± 5.4 | .391† |

|

| |||

| Measured BMI (kg/m2), mean ± SD | 23.6 ± 3.2 | 25.3 ± 6.8 | .399† |

|

| |||

| UCLA*, median (range) | 10 (4 to 10) | 10 (4 to 10) | .756§ |

|

| |||

| HOOSPain,** mean ± SD | 71.61 ±11.59 | 74.42± 8.79 | .486§ |

|

| |||

| HOOSSymptoms,** mean ± SD | 66.43± 16.10 | 71.15 ±10.44 | .378§ |

|

| |||

| HOOSADL,** mean ± SD | 84.77±11.52 | 89.14±6.99 | .249§ |

|

| |||

| HOOSSport,** mean ± SD | 62.05±18.74 | 71.15±14.52 | .176§ |

|

| |||

| HOOSQOL,** mean ± SD | 57.59±13.69 | 54.33±14.52 | .533§ |

Abbreviations: SD, standard deviation; MoveTrain, movement pattern training group; UCLA, University of California Los Angeles Activity Score; HOOS, Hip disability and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score; ADL, activities of daily living; Sport, sport and recreation; QOL, quality of life

Chi-Square test was performed.

Independent-samples t tests were used.

Patients are asked to rate their activity level over the previous 6 months. 10=regularly participates in impact sports; 1=wholly inactive, dependent on others.

The Mann-Whitney U test was performed.

HOOS subscale scores range from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating higher levels of physical function.

3.1 |. Muscle volume changes

Table 2 provides summary data for muscle volume and strength. There was a significant interaction effect of group by time for Gmed volume (p=.043). Those in the Standard group demonstrated a greater increase in Gmed volume compared to the MoveTrain group. There was no significant interaction effect for Gmax, however, there was a main effect for group (p=.045). Those in the Standard group demonstrated a less volume compared to MoveTrain. There were no significant interactions or main effects for Gmin volume.

TABLE 2.

Summary of results for hip muscle volume and strength.

| Variable | Pretreatment Mean ± SD |

Posttreatment Mean ± SD |

Within-Group Change* Mean ± SD |

Effect of time P Value† |

Effect of group P Value† |

Interaction of group by time P Value† |

Interaction of group by time Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Hip muscle volume (cm 3 ) ‡ | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Gluteus Minimus | .712 | .826 | .733 | .07 | |||

| MoveTrain (n=14) | 84.7 ± 23.3 | 84.7 ± 21.1 | 0.0 ± 7.9 (0%) | ||||

| Standard (n=13) | 82.4 ± 18.5 | 83.4 ± 21.8 | 1.0 ± 6.3 (1%) | ||||

|

| |||||||

| Gluteus Medius | NR | NR | .043 | .43 | |||

| MoveTrain (n=14) | 294.0 ± 62.1 | 297.1 ± 62.0 | 3.1 ± 7.3 (1%) | ||||

| Standard (n=13) | 266.8 ± 48.2 | 276.4 ± 46.1 | 9.6 ± 8.6 (4%) | ||||

|

| |||||||

| Gluteus Maximus | .789 | .045 | .741 | .07 | |||

| MoveTrain (n=14) | 324.1 ± 80.2 | 324.5 ± 73.1 | 0.3 ± 32.4 (0%) | ||||

| Standard (n=12)¶ | 267.4 ± 61.3 | 264.3 ± 67.2 | −3.0 ± 13.3 (1%) | ||||

|

| |||||||

| Hip muscle strength (Nm) | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Abductors, torque | .023§ | .476§ | .579§ | .11 | |||

| MoveTrain (n=14) | 96.7 ± 41.2 | 110.5 ± 46.7 | 13.8 ± 23.0 (14%) | ||||

| Standard (n=13) | 86.9 ± 42.8 | 99.8 ± 34.9 | 12.8 ± 27.2 (15%) | ||||

|

| |||||||

| Extensors, torque | .356 | .770 | .987 | .11 | |||

| MoveTrain (n=14) | 129.3 ± 52.6 | 135.1 ± 62.9 | 5.7 ± 34.7 (4%) | ||||

| Standard (n=13) | 123.3 ± 53.1 | 129.2 ± 48.2 | 5.9 ± 29.2 (5%) | ||||

Abbreviations: MoveTrain, movement pattern training; NR, not reported due to presence of interaction effect

Change is calculated by subtracting the pretest value from the posttreatment value.

Unless otherwise indicated, p value by analysis of variance.

Muscle torque (Nm) was calculated by using the mean force of three trials x moment arm of the external resistance provided.

Data for one participant was not included in the analysis due to artefact noted in the image for gluteus maximus.

P value by non-parametric analysis of variance.

3.2 |. Strength changes

There was no significant interaction effect of group by time (p=.579) for hip abductor strength, however there was a significant main effect of time (p=.023). This suggests that both groups displayed increased hip abductor strength after the training program, but there were no differences between the groups. There were no significant interactions or main effects for hip extensor strength.

3.3 |. MFI changes

3.3.1 |. Gluteus minimus

3.3.1.1. Anterior

There was no significant interaction effect of group by time and there was no significant main effect of group. This suggests that change over time did not depend on group allocation. There was a significant main effect of time (p=.003), with MFI reducing in both groups over time (Figure 2). This occurred within two proximal clusters along the length of the muscle (proximal to distal; 5%–9% length, p=.003, ES=0.59–0.74; 18%–30% length, p=.008, ES=0.58–0.74).

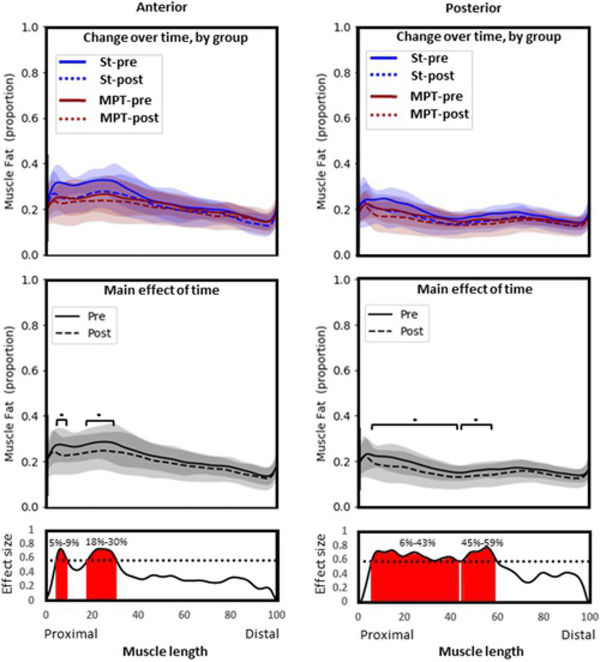

Figure 2.

Gluteus minimus. Group means and SD for proportion of fat along the length of the muscle (0%–100% = proximal to distal). Top panel: Comparison between groups over time. Middle panel: Comparison over time with groups combined (main effect of time). Bottom panel: Statistical nonparametric map describing differences in fat proportion before (solid line) and after (dashed line) exercise therapy, regardless of group allocation. Red shading indicates location along the length of the muscle where statistical significance is reached (p<.05*). MPT, movement pattern training group; pre, pretreatment values, post, posttreatment values; St, standard group

3.3.1.2. Posterior

Change in fat infiltration over time did not depend on group allocation, and there was no significant main effect of group. When groups were combined, there was a reduction in MFI over time (main effect of time, p=.001). This occurred at two clusters along the proximal portion of the muscle (proximal to distal; 6%–43% length, p=.001, ES=0.58–0.74; 45%–59% length, p=.002, ES=0.59–0.78).

3.3.2 |. Gluteus medius

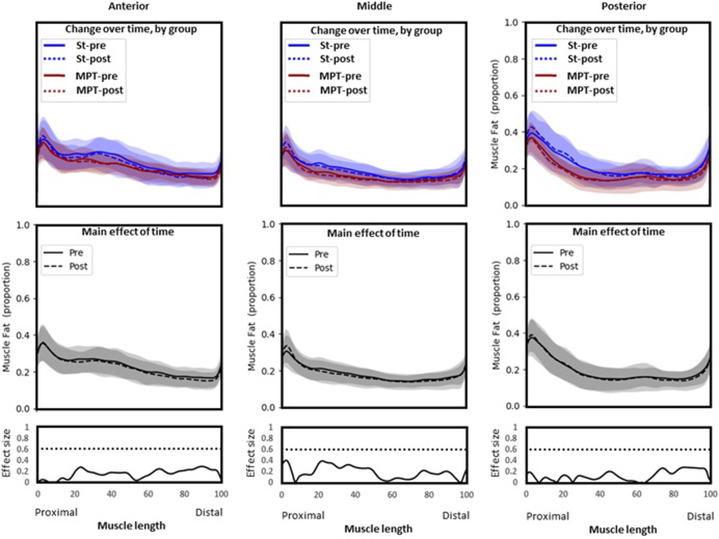

There were no significant interaction or main effects for any segment of GMed (Figure 3). This suggests that the proportion of fat did not change over time and was not different between groups.

Figure 3.

Gluteus Medius. Group means and SD for proportion of fat along the length of the muscle (0%–100% = proximal to distal). Top panel: Comparison between groups over time. Middle panel: Comparison over time with groups combined (main effect of time). Bottom panel: Statistical non-parametric map describing differences in fat proportion before (solid line) and after (dashed line) exercise therapy, regardless of group allocation. There were no significant interactions or main effects for any segment of Gmed. MPT, movement pattern training group; pre, pretreatment values, post, posttreatment values; St, standard group

3.3.3 |. Gluteus maximus

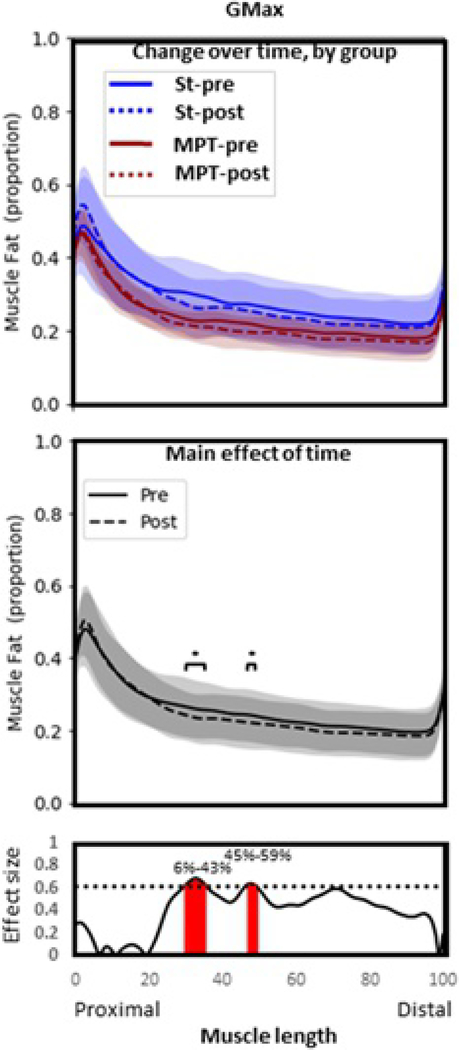

There was no significant interaction effect or main effect of group, suggesting that the response of GMax adiposity over time did not depend on group allocation (Figure 4). There was a significant reduction of adiposity over time, regardless of group (main effect of time, p=.02). This occurred at two clusters along the length of GMax (proximal to distal; 30%–35% length, p=.010, ES=0.63–0.69; 47%–49% length, p=.018, ES=0.93–0.64).

Figure 4.

Gluteus maximus. Group means and SD for proportion of fat along the length of the muscle (0%–100% = proximal to distal). Top panel: Comparison between groups over time. Middle panel: Comparison over time with groups combined (main effect of time). Bottom panel: statistical nonparametric map describing differences in fat proportion before (solid line) and after (dashed line) exercise therapy, regardless of group allocation. Red shading indicates location along the length of the muscle where statistical significance is reached (p<.05). MPT, movement pattern training group; pre, pretreatment values, post, posttreatment values; St, standard group

4 |. DISCUSSION

We noted posttreatment changes in structure and function of the hip musculature among patients with HRGP participating in movement pattern training and a standard program of strengthening and flexibility, however the changes were not uniform across the two treatment groups and the changes were modest. These findings suggest that both training programs may have positive effects on muscle, however more research is needed to determine the type and dosage of specific exercise or activity that would result in the greatest change.

4.1 |. Muscle strength and volume

Both groups demonstrated significantly increased hip abductor strength, but no change in hip extensor strength. Hip abductor strength increased by 14% (MoveTrain) and 15% (Standard), strength gains that are within the range of strength improvements reported in previous studies.45–48 Among patients with HRGP, primarily femoroacetabular impingement, strength improvements of 2%–23% have been reported for hip abductors and 3%–27% for hip extensors.45–48 We hypothesized that Standard would have significantly greater gains in strength based on greater evidence supporting muscle strength increases after progressive loading.29–31 Additionally, participants in MoveTrain were required to perform all activities with specific movement modifications, which we hypothesized would slow overall activity progression and potentially limit the impact on muscle structure. Surprisingly, abductor strength gains were similar in both groups. It is possible, that increased strength in MoveTrain group may be related to increased neural drive as a result of the task specific training.

The Standard group showed a significantly greater increase in Gmed volume after treatment compared to the MoveTrain group, however, changes in both groups were small. Additionally, little change occurred in the Gmin and Gmax volume. We were unable to find previous studies reporting the effect of exercise on hip muscle volume. Related to other lower extremity muscles, the Gmed volume increase noted in Standard (4%) was within the range of values previously reported among healthy participants after completing a strengthening program targeting thigh musculature.29,30,49 Quadriceps or hamstring muscles displayed a 2%–10% increase in muscle size (thickness or volume) after high-intensity resistance training.29,30,49

There are several possible explanations for our modest findings related to strength and volume. The small changes may due to dosage. The resistance added to exercise was determined by patient performance and their ability to perform exercises without any increase in hip joint pain. The population in our study was symptomatic, so the load added was most likely below the suggested intensity of 60%–70% of 1 repetition maximum to induce muscle hypertrophy in a healthy person.50 While there are many challenges associated with overloading a painful joint, it is possible the avoidance of increased pain during exercise performance contributed to insufficient loading. We compared our exercise protocol to those studies reporting greater strength gains for hip abduction and extension.46,47 In the previous studies and ours, the duration of treatment was 12 weeks and the method of progressing the exercises for each patient were similar. There were a few differences. In our study, patients participated in one supervised session and HEP (daily performance). In the studies by Kemp et al.47 and Casartelli et al,6 patients participated in two supervised sessions and HEP (two times per week). The additional supervised session in the previous studies may have resulted in greater overall adherence to exercise performance. Additionally, our study was designed to assess the effect of each specific treatment, MoveTrain and Standard, therefore exercises were limited to the activities and exercises specific to each treatment arm. The previous studies incorporated multiple treatment strategies, including manual therapy techniques, hip-specific strengthening, trunk strengthening, postural balance, and neuromuscular control that include pelvic control during performance of tasks. Therefore, it is difficult to directly compare treatment approaches across the three studies.

Acute joint effusion and pain have been shown to reduce quadriceps and gluteal muscle strength through arthrogenic inhibition in the knee and hip, respectively.51,52 We reviewed the images collected and noted that none of our patients displayed joint effusions based on the Scoring Hip Osteoarthritis with MRI (SHOMRI)53 definition; this lack of joint effusions may be due to the pain chronicity among our patients. We are unsure why there were no changes in muscle volume in the Gmin or Gmax in either group, however it may be related to the change in MFI in each muscle. We noted a decrease in MFI among the Gmin and Gmax, which suggests that some muscle hypertrophy may have occurred, yet the effect on overall volume may be blunted by the reduction in the presence of fat.

4.2 |. Muscle fat index

After treatment, the MFI was significantly reduced across groups in Gmax and Gmin, but not Gmed. There is evidence to suggest greater fatty infiltration in Gmax and Gmin in chronic hip conditions compared to matched peers.15,16,54 It is possible that Gmax and Gmin may have had a high percentage of MFI at baseline, thus predisposing the muscles to greater changes in MFI. Conversely, increased Gmed fatty infiltration seems to occur later in the disease progression. Individuals with advanced OA present with significantly reduced Gmed volume (12%–14%)17,55 and increased fatty infiltration.16–18 Several studies15,19 have found no difference in fatty infiltration in Gmed among patients with greater trochanteric pain syndrome and mild to moderate OA when compared to controls. The population within our study was relatively early in the disease progression, compared to those with advanced OA, which may explain the absence of change in Gmed MFI.

Just as the changes in MFI was not uniform across Gmed, Gmin and Gmax, the distribution of MFI varied within the muscles. Future studies assessing impact of MFI within HRGP should consider analysis of the hip abductors proximal to the acetabulum as those areas were shown to have the greatest change in MFI within our cohort.

4.3 |. Limitations

We did not compare baseline gluteal volume, strength or MFI to asymptomatic people therefore we cannot state if the findings among our patients with HRGP were abnormal. Our previous work suggests that patients with HRGP have weak musculature5 and may actually have larger muscle compared to asymptomatic individuals.7

We are unsure why patients randomized to the Standard group demonstrated less (not significant) Gmed volume at baseline compared to those in the MoveTrain group. There was one more male patient in MoveTrain than in Standard, which may explain the difference. Males in our study did demonstrate greater Gmed volume compared to females (baseline values: 329.7+50 vs. 247.3+30.0, p=<.0001). Greater body mass has been shown to be associated with larger muscle size,56 therefore, normalizing muscle volume by body mass may have controlled for this baseline difference. There is no standard approach in reporting muscle size. Given our main interest was to determine muscle changes with treatment, we decided a priori not to normalize muscle volume or strength. We performed a post hoc sensitivity analysis using the Gmed volume normalized to body mass, to determine if baseline differences or study results would differ. The overall study conclusions were unchanged. With inspection of patient characteristics at baseline, groups were similar in age, body mass index, activity level, and in their patient-reported outcome measures. Although HOOS values were lower in the MoveTrain group compared to Standard, the between group differences were not greater than reported minimal clinically important differences.57 Randomization is performed to minimize bias among the treatment groups, however it cannot guarantee that all study variables will be equal in both groups. A larger sample may be needed to better represent the patient population.

Recent consensus statements58–60 have recommended the Hip and Groin Outcome Score and the International Hip Outcome Tool instruments to assess hip-specific function in this patient population. Our study was designed using pilot data collected before the publication of these recommendations, therefore we used the HOOS instrument, which is one of the most commonly used instruments for this patient population. It should be noted the published recommendations are based on surgical literature; the best patient-reported outcome measures for nonoperative treatment yet to be determined.58 Finally, we did not perform interrater reliability of our muscle volume measures. For this exploratory study, we elected to have one examiner complete all segmentations to minimize measurement error, therefore we assessed intrarater reliability only.

Movement pattern training or a program of strength/flexibility training may be effective at improving hip abductor strength and reducing fatty infiltration in the gluteal musculature among those with HRGP, however, the changes noted in this study were modest. Future studies are needed to better understand the etiology of strength changes and the impact of muscle volume and fatty infiltration on treatment outcomes for those with HRGP.

Statement of Clinical Significance:

Movement pattern training or a program of strength/flexibility training may be effective at improving hipabductor strength and reducing fatty infiltration in the gluteal musculature among those with HRGP. Further research is needed to betterunderstand etiology of strength changes and impact of muscle volume and MFI in HRGP and the effect of exercise on muscle structure andfunction.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to acknowledge Megan Burgess, Visnja King, Suzanne Kuebler, Joseph Mancino and Dave Wortman for providing treatment during the trial; Allyn Bove, Kathy Brown, Martha Hessler and Darrah Snozek their assistance with trial procedures and data collection.

This work was supported by the following grants: the Orthopaedic Research Grant from the Foundation for Physical Therapy Research; R21HD086644 and NIH T32HD007434 from the National Center for Medical Rehabilitation Research, National Institute of Child Health and Human Development; Washington University Institute of Clinical and Translational Sciences grant UL1TR002345 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Additional support was provided by Program in Physical Therapy at Washington University School of Medicine, Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) Grant [UL1 TR000448] and Siteman Comprehensive Cancer Center and NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA091842

Funding Information

National Cancer Institute : P30 CA091842

National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences : UL1 TR000448 : UL1TR002345

National Center for Medical Rehabilitation Research : R21HD086644 : T32HD007434

Foundation for Physical Therapy : Orthopaedic Research Grant

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors declare that there are no conflict of interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Harris-Hayes M, Royer NK. Relationship of acetabular dysplasia and femoroacetabular impingement to hip osteoarthritis: a focused review. PM R.2011;3:1055–1067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McCarthy JC, Noble PC, Schuck MR, Wright J, Lee J. The Otto E. Aufranc Award: the role of labral lesions to development of early degenerative hip disease. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001;393:25–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Agricola R, Heijboer MP, Bierma-Zeinstra SM, Verhaar JA, Weinans H, Waarsing JH. Cam impingement causes osteoarthritis of the hip: a nationwide prospective cohort study (CHECK). Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72:918–923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bitton R. The economic burden of osteoarthritis. Am J Manag Care. 2009;15:S230–S235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harris-Hayes M, Mueller MJ, Sahrmann SA, et al. Persons with chronic hip joint pain exhibit reduced hip muscle strength. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2014;44:890–898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Casartelli NC, Maffiuletti NA, Item-Glatthorn JF, et al. Hip muscle weakness in patients with symptomatic femoroacetabular impingement. Osteoarth Cartil. 2011;19:816–821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mastenbrook MJ, Commean PK, Hillen TJ, et al. Hip abductor muscle volume and strength differences between women with chronic hip joint pain and asymptomatic controls. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2017;47:923–930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kierkegaard S, Mechlenburg I, Lund B, Søballe K, Dalgas U. Impaired hip muscle strength in patients with femoroacetabular impingement syndrome. J Sci Med Sport. 2017;20:1062–1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Neumann D. Kinesiology of the Musculoskeletal System: Foundations for Rehabilitation. St. Louis: Mosby Inc; 2010:511–513. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Malloy P, Stone AV, Kunze KN, Neal WH, Beck EC, Nho SJ. Patients with unilateral femoroacetabular impingement syndrome have asymmetrical hip muscle cross-sectional area and compensatory muscle changes associated with preoperative pain level. Arthroscopy. 2019;35:1445–1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rahemi H, Nigam N, Wakeling JM. The effect of intramuscular fat on skeletal muscle mechanics: implications for the elderly and obese. J R Soc Interface. 2015;12:20150365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jiang Z, Marriott K, Maly MR. Impact of inter- and intramuscular fat on muscle architecture and capacity. Crit Rev Biomed Eng. 2019;47:515–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elliott JM, O’Leary S, Sterling M, Hendrikz J, Pedler A, Jull G. Magnetic resonance imaging findings of fatty infiltrate in the cervical flexors in chronic whiplash. Spine. 2010;35:948–954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sions JM, Elliott JM, Pohlig RT, Hicks GE. Trunk muscle characteristics of the multifidi, erector spinae, psoas, and quadratus lumborum in older adults with and without chronic low back pain. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2017;47:173–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cowan RM, Semciw AI, Pizzari T, et al. Muscle size and quality of the gluteal muscles and tensor fasciae latae in women with greater trochanteric pain syndrome. Clin Anat. 2020;33:1082–1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kovalak E, Özdemir H, Ermutlu C, Obut A. Assessment of hip abductors by MRI after total hip arthroplasty and effect of fatty atrophy on functional outcome. Acta Orthop Traumatol Turc. 2018;52:196–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Momose T, Inaba Y, Choe H, Kobayashi N, Tezuka T, Saito T. CT-based analysis of muscle volume and degeneration of gluteus medius in patients with unilateral hip osteoarthritis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2017;18:457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rasch A, Bystrom AH, Dalen N, Berg H. Reduced muscle radiological density, cross-sectional area, and strength of major hip and knee muscles in 22 patients with hip osteoarthritis. Acta Orthop. 2007;78:505–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zacharias A, Pizzari T, English DJ, Kapakoulakis T, Green RA. Hip abductor muscle volume in hip osteoarthritis and matched controls. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2016;24:1727–1735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yoshiko A, Tomita A, Ando R, et al. Effects of 10-week walking and walking with home-based resistance training on muscle quality, muscle size, and physical functional tests in healthy older individuals. Eur Rev Aging Phys Act. 2018;15:13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.O’Leary S, Jull G, Van Wyk L, Pedler A, Elliott J. Morphological changes in the cervical muscles of women with chronic whiplash can be modified with exercise-A pilot study. Muscle Nerve. 2015;52:772–779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goodpaster BH, Chomentowski P, Ward BK, et al. Effects of physical activity on strength and skeletal muscle fat infiltration in older adults: a randomized controlled trial. J Appl Physiol. 2008;105:1498–1503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Preece SJ, Jones RK, Brown CA, Cacciatore TW, Jones AK. Reductions in co-contraction following neuromuscular re-education in people with knee osteoarthritis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2016;17:372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Preece SJ, Cacciatore TW, Jones RK. Reductions in co-contraction during a sit-to-stand movement in people with knee osteoarthritis following neuromuscular re-education. Osteoarth Cartil. 2017;25:S121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nagelli C, Di Stasi S, Tatarski R, et al. Neuromuscular training improves self-reported function and single-leg landing hip biomechanics in athletes after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Orthop J Sports Med. 2020;8:2325967120959347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harris-Hayes M, Steger-May K, van Dillen LR, et al. Reduced hip adduction is associated with improved function after movement-pattern training in young people with chronic hip joint pain, Randomized controlled trial. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2018;48:316–324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Di Stasi S, Myer GD, Hewett TE. Neuromuscular training to target deficits associated with second anterior cruciate ligament injury. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2013;43:777–792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harris-Hayes M, Steger-May K, Bove AM, et al. Movement pattern training compared with standard strengthening and flexibility among patients with hip-related groin pain: results of a pilot multicentre randomised clinical trial. BMJ Open Sport Exerc Med. 2020;6:e000707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Franchi MV, Longo S, Mallinson J, et al. Muscle thickness correlates to muscle cross-sectional area in the assessment of strength training-induced hypertrophy. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2018;28:846–853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bottaro M, Veloso J, Wagner D, Gentil P. Resistance training for strength and muscle thickness: Effect of number of sets and muscle group trained. Sci Sports. 2011;26:259–264. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Suetta C, Magnusson SP, Rosted A, et al. Resistance training in the early postoperative phase reduces hospitalization and leads to muscle hypertrophy in elderly hip surgery patients—a controlled, randomized study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:2016–2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reiman MP, Thorborg K. Clinical examination and physical assessment of hip joint-related pain in athletes. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2014;9:737–755. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nilsdotter A, Bremander A. Measures of hip function and symptoms: Harris Hip Score (HHS), Hip Disability and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (HOOS), Oxford Hip Score (OHS), Lequesne Index of Severity for Osteoarthritis of the Hip (LISOH), and American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons (AAOS) Hip and Knee Questionnaire. Arthritis Care Res. 2011;63:S200–S207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Naal FD, Impellizzeri FM, Leunig M. Which is the best activity rating scale for patients undergoing total joint arthroplasty?Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467:958–965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stratford PW, Balsor BE. A comparison of make and break tests using a hand-held dynamometer and the Kin-Com. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1994;19:28–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Flack NA, Nicholson HD, Woodley SJ. The anatomy of the hip abductor muscles. Clin Anat. 2014;27:241–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Smith AC, Knikou M, Yelick KL, et al. MRI measures of fat infiltration in the lower extremities following motor incomplete spinal cord injury: reliability and potential implications for muscle activation. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc. 2016;2016:5451–5456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Elliott JM, Smith AC, Hoggarth MA, et al. Muscle fat infiltration following whiplash: a computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging comparison. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0234061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Marcon M, Berger N, Manoliu A, et al. Normative values for volume and fat content of the hip abductor muscles and their dependence on side, age and gender in a healthy population. Skeletal Radiol. 2016;45:465–474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Weber KA, Smith AC, Wasielewski M, et al. Deep learning convolutional neural networks for the automatic quantification of muscle fat infiltration following whiplash injury. Sci Rep. 2019;9:7973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Semciw AI, Pizzari T, Murley GS, Green RA. Gluteus medius: an intramuscular EMG investigation of anterior, middle and posterior segments during gait. J Electromyogr Kinesiol. 2013;23:858–864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zacharias A, Pizzari T, Semciw AI, English DJ, Kapakoulakis T, Green RA. Gluteus medius and minimus activity during stepping tasks: Comparisons between people with hip osteoarthritis and matched control participants. Gait Posture. 2020;80:339–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pataky TC. One-dimensional statistical parametric mapping in Python. Comput Methods Biomech Biomed Engin. 2012;15:295–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Guenther JR, Cochrane CK, Crossley KM, Gilbart MK, Hunt MA. A Pre-operative exercise intervention can be safely delivered to people with femoroacetabular impingement and improve clinical and biomechanical outcomes. Physiother Can. 2017;69:204–211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Casartelli NC, Bizzini M, Maffiuletti NA, et al. Exercise therapy for the management of femoroacetabular impingement syndrome: Preliminary results of clinical responsiveness. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2019;71:1074–1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kemp JL, Coburn SL, Jones DM, Crossley KM. The Physiotherapy for Femoroacetabular Impingement Rehabilitation STudy (physioFIRST): a pilot randomized controlled trial. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2018;48:307–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Harris-Hayes M, Czuppon S, Van Dillen LR, et al. Movement-pattern training to improve function in people with chronic hip joint pain: a feasibility randomized clinical trial. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2016;46:452–461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Abe T, DeHoyos DV, Pollock ML, Garzarella L. Time course for strength and muscle thickness changes following upper and lower body resistance training in men and women. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2000;81:174–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Riebe D, Ehrman JK, Liguori G, et al. 2018. ACSM’s Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription. 10 ed. Wolters Kluwer Health. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Freeman S, Mascia A, McGill S. Arthrogenic neuromuscular inhibition: a foundational investigation of existence in the hip joint. Clin Biomech. 2013;28:171–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Palmieri-Smith RM, Villwock M, Downie B, Hecht G, Zernicke R. Pain and effusion and quadriceps activation and strength. J Athl Train. 2013;48:186–191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lee S, Nardo L, Kumar D, et al. Scoring hip osteoarthritis with MRI (SHOMRI): a whole joint osteoarthritis evaluation system. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2015;41:1549–1557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zacharias A, Green RA, Semciw A, English DJ, Kapakoulakis T, Pizzari T. Atrophy of hip abductor muscles is related to clinical severity in a hip osteoarthritis population. Clin Anat. 2018;31:507–513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Grimaldi A, Richardson C, Stanton W, Durbridge G, Donnelly W, Hides J. The association between degenerative hip joint pathology and size of the gluteus medius, gluteus minimus and piriformis muscles. Man Ther. 2009;14:605–610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nuzzo JL, Mayer JM. Body mass normalisation for ultrasound measurements of lumbar multifidus and abdominal muscle size. Man Ther. 2013;18:237–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kemp JL, Collins NJ, Roos EM, Crossley KM. Psychometric properties of patient-reported outcome measures for hip arthroscopic surgery. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41:2065–2073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Impellizzeri FM, Jones DM, Griffin D, et al. Patient-reported outcome measures for hip-related pain: a review of the available evidence and a consensus statement from the International Hip-related Pain Research Network, Zurich 2018. Br J Sports Med. 2020;54:848–857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Griffin DR, Dickenson EJ, O’Donnell J, et al. The Warwick Agreement on femoroacetabular impingement syndrome (FAI syndrome): an international consensus statement. Br J Sports Med. 2016;50:1169–1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Enseki K, Harris-Hayes M, White DM, et al. Nonarthritic hip joint pain. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2014;44:A1–A32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]