Abstract

Background

Women with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) (WHIV) are at higher risk of adverse birth outcomes. Proposed mechanisms for the increased risk include placental arteriopathy (vasculopathy) and maternal vascular malperfusion (MVM) due to antiretroviral therapy and medical comorbid conditions. However, these features and their underlying pathophysiologic mechanisms have not been well characterized in WHIV.

Methods

We performed gross and histologic examination and immunohistochemistry staining for vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGF-A), a key angiogenic factor, on placentas from women with ≥1 MVM risk factors including: weight below the fifth percentile, histologic infarct or distal villous hypoplasia, nevirapine-based antiretroviral therapy, hypertension, and preeclampsia/eclampsia during pregnancy. We compared pathologic characteristics by maternal HIV serostatus.

Results

Twenty-seven of 41 (placentas 66%) assessed for VEGF-A were from WHIV. Mean maternal age was 27 years. Among WHIV, median CD4 T-cell count was 440/µL, and the HIV viral load was undetectable in 74%. Of VEGF-A–stained placentas, both decidua and villous endothelium tissue layers were present in 36 (88%). VEGF-A was detected in 31 of 36 (86%) with decidua present, and 39 of 40 (98%) with villous endothelium present. There were no differences in VEGF-A presence in any tissue type by maternal HIV serostatus (P = .28 to >.99). MVM was more common in placentas selected for VEGF-A staining (51 vs 8%; P < .001).

Conclusions

VEGF-A immunostaining was highly prevalent, and staining patterns did not differ by maternal HIV serostatus among those with MVM risk factors, indicating that the role of VEGF-A in placental vasculopathy may not differ by maternal HIV serostatus.

Keywords: Malperfusion, small for gestational age, intra-uterine growth restriction, Africa, resource-limited, pregnancy, pregnant, immunohistochemistry, histology, pathology

A well-developed placental vascular network is crucial to ensure efficient transport of nutrients, oxygenated blood, and waste between maternal and fetal circulation. Despite the critical importance of normal blood flow at the maternal-fetal interface, placental decidual arteriopathy (placental vasculopathy) has been incompletely characterized [1–4]. Decidual arteriopathy is a pathologic change occurring in decidual spiral arteries that has important potential consequences for fetal development. Decidual arteriopathy is associated with maternal metabolic and autoimmune disease, placental insufficiency, fetal growth restriction, and low birthweight, and shares some histologic features with coronary arterial atheromatous lesions [5]. Decidual arteriopathy is one abnormality seen in maternal vascular malperfusion (MVM), a placental injury pattern of the maternal decidual vessels related to altered uterine and intervillous blood flow [6].

Women with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) (WHIV) are at higher risk of placental vascular abnormalities, including arteriopathy and MVM due to side effects of specific classes of antiretroviral therapy (ART), and coexisting medical conditions [7]. However, few studies have focused on placental arteriopathy among WHIV, and data from women living in resource-limited settings are even more scarce. WHIV are also at increased risk of adverse birth outcomes including miscarriage, preterm labor, intrauterine growth restriction, and small-for-gestational-age neonates [8–10], all of which could result from, or be complicated by, decidual arteriopathy and MVM [6].

Angiogenic factors, including vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGF-A), play important roles in placental vascular development. One of several VEGF isoforms, VEGF-A is produced by placental cytotrophoblasts (stem cells of the trophoblast lineage) and Hofbauer cells (villous histiocytes) and promotes vasculogenesis during early pregnancy and angiogenesis throughout pregnancy [11]. VEGF-A exerts proangiogenic effects on associated transmembrane tyrosine kinase receptors, and its effects are inhibited when bound to soluble tyrosine kinase receptors, as occurs in hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, including preeclampsia and eclampsia [12]. Angiogenic factor imbalance can also lead to MVM [13], intrauterine hypoxia, miscarriage [14, 15], and adverse birth outcomes, including preterm delivery, low birthweight, and small-for-gestational age birth [10, 16]. However, patterns of VEGF-A expression and association with placental arteriopathy and MVM have not been described in WHIV or women living in sub-Saharan Africa.

To address this gap in knowledge, we carried out a secondary study of decidual arteriopathy among a large cohort of WHIV and HIV-uninfected women presenting for delivery in Uganda. Our goal was to compare the prevalence of MVM by maternal HIV serostatus and VEGF-A expression patterns in a subset of 44 placentas with risk factors for or histopathologic signs of decidual arteriopathy. We hypothesized that VEGF-A expression and MVM would be more prevalent in placentas from WHIV.

METHODS

Participant Recruitment

Between September 2017 and February 2018, pregnant participants were recruited from Mbarara Regional Referral Hospital (MRRH) in southwestern Uganda into a prospective cohort study of chronic placental inflammation among [17]. MRRH serves a semirural catchment population of approximately 9 million people and reports nearly 10 000 deliveries annually. All women presenting to MRRH for delivery were screened for enrollment and were eligible if they were in early-stage labor, aged ≥18 years, and reachable by phone after discharge for follow-up; if they spoke English or the local language, Runyankole; and if they had a single-gestation pregnancy. WHIV were eligible only if they met these criteria and also reported taking ART within the last 30 days.

Eligible WHIV were enrolled consecutively, and HIV-uninfected comparators were selected as the next eligible woman presenting for delivery after each enrolled woman in the WHIV group. After enrollment of 150 total participants, HIV-uninfected women were enrolled selectively to balance gestational age and parity by HIV serostatus. The study was approved by the institutional ethics review boards at Mbarara University of Science and Technology (MUST; no. 11/03-17), Partners Healthcare (no. 2017P001319/MGH), and the Uganda National Council of Science and Technology (no. HS/2255). All participants gave written informed consent to participate.

Data Collection

After enrollment, a structured face-to-face questionnaire was administered to collect sociodemographic information, and obstetric and medical history. Gestational age was calculated using participant report of last normal menstrual period, or chart documentation if participant report was missing. Data were entered into a Research Electronic Capture (REDCap) database [18].

Sample Collection and Placental Gross Pathology and Histology

Maternal whole blood was collected and tested for HIV (Determine HIV 1/2; Abbott) (in HIV-uninfected women only). CD4 count and HIV viral load were measured for WHIV if results within the last 6 months were not available. The placenta was delivered after birth into a clean plastic bucket and transferred to a sterile field. Complete gross pathologic examination was performed by research assistants trained by an experienced perinatal pathologist (D. J. R.), and samples of membrane roll, full-thickness placental parenchyma (at least 2 samples, including 1 from the placental center and 1 from the periphery), umbilical cord, and grossly identified placental lesions were formalin fixed.

Placental samples were transferred to the MUST Pathology Laboratory, adjacent to MRRH, for routine processing, paraffin embedding, sectioning at 5 µm, and hematoxylin-eosin staining. Slides were mounted with DPX mountant and sent to an expert perinatal pathologist (D. J. R.), who performed all histopathologic analysis, blinded to maternal HIV serostatus. Membrane rolls, umbilical cords, and parenchyma were scored for abruption, infarcts, MVM, fetal vascular malperfusion, and arteriopathy, using Amsterdam consensus [1] nosology. Due to funding constraints, a subset of placentas, 44 of 352 (13%), was selected for VEGF-A immunostaining based on having ≥1 of the following features of or risk factors for MVM, in the current pregnancy: placental weight below the fifth percentile (<300 g at term; n = 16), placental infarct (n = 13), receipt of nevirapine for HIV treatment (n = 9), diagnosis of preeclampsia or eclampsia (n = 2), placental histology showing diffuse distal villous hypoplasia (n = 3) or abruption (n = 1), and hypertension (n = 2) [19–21]. Two of 44 cases (.5%) met >1 selection criterion.

Placental VEGF-A Immunostaining

In the MUST pathology laboratory, new sections were cut from the selected placental paraffin blocks and were deparaffinized with xylene and alcohol and hydrated in distilled water, using a manual protocol. Sections were heated in the Bio SB TintoRetriever Pressure Cooker, using 1× citrate buffer (Bio SB), and were cooled and then blocked for 10 minutes with Dako peroxidase (Agilent). Slides were then buffered in Tris solution for 3 minutes before incubation with monoclonal anti-rabbit VEGF-A, diluted 1:100 (Abcam) in Dako primary antibody diluent (Agilent) for 60 minutes at room temperature. Slides were rinsed with Tris buffer and incubated with Dako HRP-labeled anti-rabbit secondary antibody (Agilent) for 30 minutes.

Slides were rinsed with Tris buffer and incubated with Dako 3,3-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride hydrate chromogen for 10 minutes (Agilent), rinsed in distilled water, and counterstained with hematoxylin for 1 minute, followed by tap water and alcohol dehydration using an automatic stainer. Slides were mounted with DPX mountant and sent to D. J. R. for interpretation. VEGF-A staining intensity was graded separately for maternal decidua, maternal endothelium, and fetal tissues on a semiquantitative scale, graded as absent (0) weak (1+; 5% of stained cells), moderate (1+ to 2+; 10%–25% of stained cells), strong (2+; 25%–50% of stained cells), or very strong (3+; >50% of stained cells). Transmitted light images were taken using a 10×/0.25 or 40×/0.65 N Plan objective of an Olympus BX41 microscope and an Olympus DP27 microscope-mounted camera. Images were acquired using Olympus CellSens software (CellSens Entry 2.2) and optimized with Adobe Photoshop software (Adobe CS5).

Sample Size and Data Analysis

Sample size for the parent study was calculated to determine the difference in prevalence of chronic placental inflammation by maternal HIV serostatus (primary parent study aim). No sample size calculation was performed for this secondary analysis, and all placentas having ≥1 risk factor for or feature of MVM were selected for staining. Demographic characteristics, outcomes, and placental characteristics were compared between women whose placentas were selected for VEGF-A immunostaining and those not stained, using Student t or Wilcoxon rank sum tests for continuous variables and χ 2 or Fisher exact tests for categorical variables as appropriate, with differences considered statistically significant at P < .05. Summary statistics were used to characterize placental pathology findings, and differences in placental immunostaining characteristics by maternal HIV serostatus were assessed using Fisher exact tests. All analyses were performed using Stata software (version 16.0; StataCorp).

RESULTS

Enrollment and Cohort Characteristics

Over 6 months, 1940 women were screened for the parent cohort. Of 1489 who were eligible, 176 WHIV and 176 HIV-uninfected women were enrolled (Supplementary Figure). The mean cohort age (standard deviation) was 27 (6) years and was the same for women whose placentas were VEGF-A immunostained and those whose were not (P = .83). Parity was similar in immunostained and unstained groups (2.9 vs 2.7; P = .49), but gestational age was significantly lower in the VEGF-A immunostained group (38 vs 39 weeks; P < .001) (Table 1). The median CD4 T-cell count among WHIV was 440/µL, and 74% had an undetectable HIV viral load within the last 6 months. The most common ART regimens were tenofovir-lamivudine-efavirenz (n = 113 [76%]) and zidovudine-lamivudine/-efavirenz (n = 11 [7%]) among WHIV whose placentas were not immunostained and tenofovir-lamivudine-efavirenz (n = 15 [56%]) and lamivudine-stavudine-nevirapine (n = 2 [7%]) among those whose placentas were VEGF-A immunostained.

Table 1.

Demographic, Medical, and Placental Characteristics in a Cohort of Women Presenting in Labor to Mbarara Regional Referral Hospital, Uganda, by Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor A Staining

| Characteristic | Women (or Newborns), No. (%)a | P Valueb | |

|---|---|---|---|

| VEGF-A Staining (n = 41 [12%]) | No Staining (n = 311 [88%]) | ||

| Demographic | |||

| Age category. y | .29 | ||

| ≤19 | 3 (7) | 26 (8) | |

| 20–34 | 29 (70) | 245 (79) | |

| ≥35 | 9 (22) | 40 (13) | |

| Resides in Mbarara District | 24 (59) | 203 (65) | .40 |

| Married | 35 (85) | 282 (91) | .29 |

| Completed more than primary school education | 24 (59) | 183 (59) | .97 |

| Monthly income, median (IQR), $ c | 25 (14–53) | 42 (28–83) | .04 |

| Formal employment outside home | 15 (37) | 112 (36) | .94 |

| Obstetric and medical | |||

| HIV seropositive | 27 (66) | 149 (48) | .03 |

| Gestational age at delivery, mean (SD), wk | 38 (2.6) | 39 (1.7) | <.001 |

| Preterm delivery (<37 wk) | 2 (5) | 3 (1) | .1 |

| Parity including current delivery | .49 | ||

| 1 (Primiparous) | 10 (24) | 77 (25) | |

| 2–4 (Multiparous) | 21 (51) | 132 (42) | |

| ≥4 (Grand multiparous) | 10 (24) | 102 (33) | |

| Antenatal care during current pregnancy | |||

| ≥4 antenatal care visits | 25 (61) | 198 (64) | .74 |

| Iron supplementation | 29 (71) | 184 (59) | .15 |

| Folic acid supplementation | 14 (34) | 137 (44) | .23 |

| Combination iron/folic acid | 32 (78) | 210 (68) | .17 |

| Malaria prophylaxis with IPTp or TMP/SMXd | 39 (95) | 297 (96) | .91 |

| Time in labor, median (IQR), h | 12 (9, 18) | 14 (8, 24) | .33 |

| Cesarean delivery | 13 (32) | 101 (32) | .92 |

| Referred to MRRH for care | 7 (17) | 49 (16) | .84 |

| 5-min Apgar score <7 | 0 (0) | 8 (3) | .32 |

| Duration of hospitalization for delivery, mean (SD), d | 2.2 (2) | 2.2 (3) | .99 |

| Birthweight category, kg | .003 | ||

| <2.5 | 6 (15) | 10 (3) | |

| 2.5–3.5 | 32 (78) | 233 (76) | |

| 3.6–4.0 | 2 (5) | 57 (19) | |

| >4.0 | 1 (2) | 8 (3) | |

| Pathology | |||

| Placental measurements, mean (SD) | |||

| Trimmed placental weight in grams (mean, SD) | 394 (116) | 466 (96) | <.001 |

| Greatest placental diameter, cm | 19 (2) | 20 (2) | <.001 |

| Greatest placental thickness, cm | 1.6 (0.5) | 1.7 (0.6) | .90 |

| Umbilical cord length, cm | 41 (14) | 40 (17) | .72 |

| Cord coiling indexe | 0.16 (0.08) | 0.18 (0.07) | .04 |

| Histologic abruption | 0 (0) | 1 (0.3) | 1.0 |

| Placental infarct(s) | 13 (32) | 0 (0) | <.001 |

| Diffuse distal villous hypoplasia | 3 (7) | 0 (0) | .001 |

| Decidual arteriopathy | 0 (0) | 1 (0.3) | .89 |

| Fetal vascular malperfusion | 4 (13) | 37 (11) | .76 |

| Maternal vascular malperfusion | 20 (51) | 23 (8) | <.001 |

| Chronic villitis | 2 (7) | 39 (12) | .48 |

| Villitis of unknown cause | 2 (8) | 24 (8) | .51 |

| Acute chorioamnionitis | 7 (17) | 92 (30) | .09 |

Abbreviations: HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; IPTp, intermittent preventive treatment in pregnancy; IQR, interquartile range; MRRH, Mbarara Regional Referral Hospital; SD, standard deviation; TMP/SMX, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole; VEGF-A, vascular endothelial growth factor A.

aData represent no. (%) of women (or infants) unless otherwise specified. Of 352 participants, 44 (13%) had placentas were selected for VEGF-A immunostaining based on having ≥1 of the following features of or risk factors for maternal vascular malperfusion: placental weight below the fifth percentile, placental infarct, receipt of nevirapine for HIV treatment, preeclampsia or eclampsia during the current pregnancy, placental histology showing diffuse distal villous hypoplasia, and hypertension during the current pregnancy; 2 of 44 met >1 selection criterion.

bTests of association between cohort characteristics and HIV serostatus were performed using χ 2, Wilcoxon rank sum, and t tests.

cReported by participant in Ugandan shillings, converted to US dollars using exchange rate for study start date (1 March 2017: $1 = 3600 Ugandan shillings);

dIPTp with either sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine or dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine, or routine prophylaxis with TMP/SMX in participants living with HIV.

eThe cord coiling index was calculated as the number of coils divided by the umbilical cord length in centimeters.

Outcomes, Placental Gross Pathology, Histopathology

Birthweight was significantly lower in the VEGF-A group (2.9 vs 3.2 kg in unstained group), as were trimmed placental weight (394 vs 466 g respectively) and diameter (19 vs 20 cm) (all P < .001) (Table 1). The prevalence of MVM was significantly higher in placentas meeting criteria for VEGF-A staining (51% vs 8% in placentas not meeting criteria; P < .001) but did not differ by maternal HIV serostatus (19% WHIV vs 17%; HIV-uninfected P = .68).

VEGF-A Immunostaining

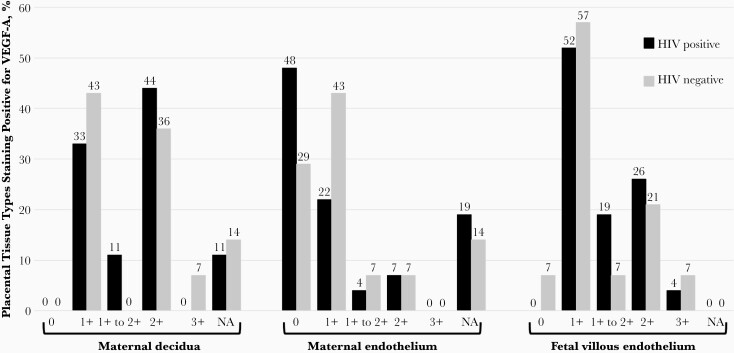

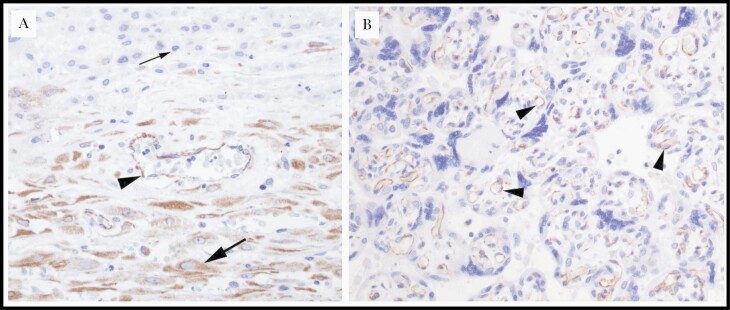

Owing to insufficient reagent, 3 of 44 placentas (1%, 1 with abruption and 2 associated with nevirapine use) initially selected for immunostaining were not stained, for a final stained sample size of 41 placentas. VEGF-A staining quality was fully interpretable in 34 of 41 placentas (83%). Owing to damaged or incomplete tissue planes, maternal endothelium was not assessable for 7 of 41 placentas (17%) and maternal decidua not assessable for 5 of 41 (12%), but the fetal villous endothelium was assessable for all 41 placentas (100%). VEGF-A was seen in the maternal decidua in all 36 assessable cases (100%), and in the fetal villous endothelium in 40 of 41 (98%) (Figure 1). VEGF-A was seen in the maternal endothelium of 9 (43%) placentas from of WHIV and 8 (67%) placentas from HIV-uninfected women (P = .28, Figures 1 and 2). Placental tissue staining location did not differ by HIV status for any of the tissue regions examined (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGF-A) immunohistochemistry staining of 41 placentas by maternal human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) serostatus (HIV positive [n = 27] or HIV negative [n = 14]), selected from a cohort of women presenting in labor in Uganda. Tissue VEGF-A staining was rated as 0 (absent), 1+ (weak; 5% of stained cells), 1+ to 2+ (moderate; 10%–25% of stained cells), 2+ (strong; 25%–50% of stained cells), 3+ (very strong; >50% stained cells), or not assessable (NA; tissue damaged or not present in sample).

Figure 2.

Representative histologic images of vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGF-A)–immunostained placental samples from women living with human immunodeficiency virus in Uganda. A, Placental membrane roll demonstrating positive VEGF-A staining in maternal endothelium (arrowhead) and decidua (large arrow) and negative staining in the extravillous trophoblast of the chorion laeve (small arrow) (original magnification ×40). B, Placental parenchyma demonstrating positive VEGF-A staining in chorionic villi and villous (fetal) endothelium (arrowheads) (original magnification ×40).

Discussion

In this subset of VEGF-A immunostained placentas selected from a cohort of WHIV and HIV-uninfected women in Uganda, VEGF-A expression was highly prevalent in the maternal decidua and fetal endothelium and less prevalent in the maternal endothelium. We found no association between maternal HIV serostatus and the presence or grade of VEGF-A in any placental tissue location, which was highly expressed overall. We had hypothesized that VEGF-A expression would be more prevalent in placentas from WHIV, based on previously published associations between ART use and adverse birth outcomes among WHIV in resource-limited settings that could be mediated by increased VEGF-A expression [22, 23]. Furthermore, VEGF-A has been demonstrated to be a biomarker for placental abnormalities in hypertensive disorders including preeclampsia or eclampsia [24–27] and fetal growth restriction [28]. However, in this cohort of WHIV taking ART, VEGF-A expression (location and staining intensity) was similar by maternal HIV serostatus. The similarity in VEGF-A expression by maternal HIV serostatus could be due to relatively good immune reconstitution and the high proportion with suppressed HIV viral load (74%) among WHIV in this cohort, or to pathophysiologic similarities in MVM and VEGF-A expression between WHIV and HIV-uninfected women.

To our knowledge, no other published studies have reported on placental VEGF-A immunostaining, but among a group of pregnant WHIV in eastern Uganda no differences in plasma angiogenic factor levels were seen by maternal ART group, though there was no HIV-uninfected comparison group, and VEGF-A was largely undetectable [16]. Our findings should be confirmed in other populations, but they suggest that among women receiving ART, imbalances in placental VEGF-A expression may not be an important contributor to adverse birth outcomes among WHIV. In our prior work, we demonstrated that chronic placental inflammation did not differ by maternal HIV serostatus and is also unlikely to be a main contributor to adverse birth outcomes among WHIV [17]. Thus, the placental origins of adverse pregnancy and birth outcomes among WHIV remain unclear, and further research is needed to examine a more diverse array of maternal cellular markers and their downstream effects on placental angiogenesis, arteriopathy, function, antibody transfer, placental arteriopathy, and childbirth outcomes.

Our study has several strengths, including comprehensive characterization of placentas, with gross and histologic placental examination, and immunohistochemistry. Our descriptive study adds to the limited understanding of placental effects on outcomes, especially among WHIV and women living in resource-limited settings. However, the small sample size (n = 41) limits our ability to detect differences between groups, and cohort enrollment at a single Ugandan referral hospital limits the generalizability of our findings, because the women enrolled may not be representative of most women. Furthermore, owing to resource constraints we did not stain placentas without MVM evidence or risk factors or measure soluble VEGF decay receptors, such as soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1 (sFlt1), or other placental growth factors. Future studies on placental arteriopathy should investigate other vascular markers and include a comparison group without risk factors for arteriopathy.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at The Journal of Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Notes

Acknowledgments. The authors are grateful to the cohort participants and to the Mbarara Regional Referral Hospital Maternity staff, Mbarara University of Science and Technology, MUST Pathology Laboratory, and Mbarara Regional Referral Hospital Immune Suppression Syndrome (ISS) Clinic for their partnership in this research.

Supplement sponsorship. This supplement is sponsored by the Harvard University Center for AIDS Research.

Disclaimer. The sponsors had no role in study design, data collection, analysis or interpretation, writing of the report, or decision to submit the article for publication. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of Harvard Catalyst, Harvard University and its affiliated academic healthcare centers, the National Institutes of Health, or other funders.

Financial support. This work was supported by the Harvard University Center for AIDS Research and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health (grant P30AI060354 to L. M. B.), Harvard Catalyst, the Harvard Clinical and Translational Science Center (KL2/Catalyst Medical Research Investigator Training award KL2TR002542 to L. M. B.), the Charles H. Hood Foundation (L. M. B.), the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (career development award K23AI138856 to L. M. B. and midcareer mentoring award K24AI141036 to I. V. B.), the American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene (Burroughs Wellcome Fellowship to L. M. B.), the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (career development award K23HD097300 to A. A. B.), and the Massachusetts General Hospital Executive Committee on Research through the Center for Diversity and Inclusion (career development award to A. A. B.).

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: No reported conflicts. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

Contributor Information

Lisa M Bebell, Division of Infectious Diseases, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts, USA; MassGeneral Global Health, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts, USA; Medical Practice Evaluation Center of Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts, USA.

Kalynn Parks, Department of Nutritional Sciences, Pennsylvania State University, University Park, Pennsylvania, USA.

Mylinh H Le, Medical Practice Evaluation Center of Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts, USA.

Joseph Ngonzi, Mbarara University of Science and Technology, Mbarara, Uganda.

Julian Adong, Mbarara University of Science and Technology, Mbarara, Uganda.

Adeline A Boatin, MassGeneral Global Health, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts, USA; Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts, USA.

Ingrid V Bassett, Division of Infectious Diseases, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts, USA; Medical Practice Evaluation Center of Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts, USA.

Mark J Siedner, Division of Infectious Diseases, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts, USA; MassGeneral Global Health, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts, USA; Medical Practice Evaluation Center of Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts, USA.

Alison D Gernand, Department of Nutritional Sciences, Pennsylvania State University, University Park, Pennsylvania, USA.

Drucilla J Roberts, Department of Pathology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts, USA.

References

- 1. Khong TY, Mooney EE, Ariel I, et al. Sampling and definitions of placental lesions: Amsterdam placental workshop group consensus statement. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2016; 140:698–713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Redline RW, Patterson P. Patterns of placental injury: correlations with gestational age, placental weight, and clinical diagnoses. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1994; 118:698–701. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hecht JL, Zsengeller ZK, Spiel M, Karumanchi SA, Rosen S. Revisiting decidual vasculopathy. Placenta 2016; 42:37–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chan JS, Heller DS, Baergen RN. Decidual vasculopathy: placental location and association with ischemic lesions. Pediatr Dev Pathol 2017; 20:44–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Avagliano L, Monari F, Po’ G, et al. The burden of placental histopathology in stillbirths associated with maternal obesity. Am J Clin Pathol 2020; 154:225–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ernst LM. Maternal vascular malperfusion of the placental bed. APMIS 2018; 126:551–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kalk E, Schubert P, Bettinger JA, et al. Placental pathology in HIV infection at term: a comparison with HIV-uninfected women. Trop Med Int Health 2017; 22:604–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Evans C, Humphrey JH, Ntozini R, Prendergast AJ. HIV-exposed uninfected infants in Zimbabwe: insights into health outcomes in the pre-antiretroviral therapy era. Front Immunol 2016; 7:190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dauby N, Goetghebuer T, Kollmann TR, Levy J, Marchant A. Uninfected but not unaffected: chronic maternal infections during pregnancy, fetal immunity, and susceptibility to postnatal infections. Lancet Infect Dis 2012; 12:330–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Obimbo MM, Zhou Y, McMaster MT, et al. Placental structure in preterm birth among HIV-positive versus HIV-negative women in Kenya. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2019; 80:94–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wang Y, Zhao S. Vascular biology of the placenta. San Rafael, CA: Morgan & Claypool Life Sciences, 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Maynard SE, Min JY, Merchan J, et al. Excess placental soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1 (sFlt1) may contribute to endothelial dysfunction, hypertension, and proteinuria in preeclampsia. J Clin Invest 2003; 111:649–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chehroudi C, Kim H, Wright TE, Collier AC. Dysregulation of inflammatory cytokines and inhibition of VEGFA in the human umbilical cord are associated with negative pregnancy outcomes. Placenta 2019; 87:16–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Krukier II, Pogorelova TN. Production of vascular endothelial growth factor and endothelin in the placenta and umbilical cord during normal and complicated pregnancy. Bull Exp Biol Med 2006; 141:216–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sajjadi MS, Ghandil P, Shahbazian N, Saberi A. Association of vascular endothelial growth factor A polymorphisms and aberrant expression of connexin 43 and VEGFA with idiopathic recurrent spontaneous miscarriage. J Obstet Gynaecol Res 2020; 46:369–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Conroy AL, McDonald CR, Gamble JL, et al. Altered angiogenesis as a common mechanism underlying preterm birth, small for gestational age, and stillbirth in women living with HIV. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2017; 217:684.e1-. e17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bebell LM, Siedner MJ, Ngonzi J, et al. Brief report: chronic placental inflammation among women living with HIV in Uganda. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2020; 85:320–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 2009; 42:377–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zash RJ, Roberts M, Souda DJ, et al. Placental evidence of maternal vascular malperfusion among HIV-infected women. Presented at: Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; March 4-7, 2018;Boston, MA. Abstract 834. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rotshenker-Olshinka K, Michaeli J, Srebnik N, et al. Recurrent intrauterine growth restriction: characteristic placental histopathological features and association with prenatal vascular Doppler. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2019; 300:1583–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wright E, Audette MC, Ye XY, et al. Maternal vascular malperfusion and adverse perinatal outcomes in low-risk nulliparous women. Obstet Gynecol 2017; 130:1112–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chen JY, Ribaudo HJ, Souda S, et al. Highly active antiretroviral therapy and adverse birth outcomes among HIV-infected women in Botswana. J Infect Dis 2012; 206:1695–705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ejigu Y, Magnus JH, Sundby J, Magnus MC. Pregnancy outcome among HIV-infected women on different antiretroviral therapies in Ethiopia: a cohort study. BMJ Open 2019; 9:e027344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bhavina K, Radhika J, Pandian SS. VEGF and eNOS expression in umbilical cord from pregnancy complicated by hypertensive disorder with different severity. Biomed Res Int 2014; 2014:982159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bustamante Helfrich B, Chilukuri N, He H, et al. Maternal vascular malperfusion of the placental bed associated with hypertensive disorders in the Boston birth cohort. Placenta 2017; 52:106–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wathén KA, Tuutti E, Stenman UH, et al. Maternal serum-soluble vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-1 in early pregnancy ending in preeclampsia or intrauterine growth retardation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2006; 91:180–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Johnson KM, Zash R, Haviland MJ, et al. Hypertensive disease in pregnancy in Botswana: prevalence and impact on perinatal outcomes. Pregnancy Hypertens 2016; 6:418–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Spinillo A, Gardella B, Adamo L, Muscettola G, Fiandrino G, Cesari S. Pathologic placental lesions in early and late fetal growth restriction. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2019; 98:1585–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.