Abstract

Endosomal microautophagy (eMI) is a type of microautophagy that allows for the selective uptake and degradation of cytosolic proteins in late endosome/multi-vesicular bodies (LE/MVB). This process starts with the recognition of a pentapeptide amino acid KFERQ-like targeting motif in the substrate protein by the hsc70 chaperone, which then enables binding and subsequent uptake of the protein into the LE/MVB compartment. The recognition of a KFERQ-like motif by hsc70 is the same initial step in chaperone-mediated autophagy (CMA), a form of selective autophagy that degrades the hsc70-targeted proteins in lysosomes in a LAMP-2A dependent manner. This shared step, originally identified for CMA, makes it now necessary to differentiate between the two pathways. Here, we detail biochemical and imaging-based methods to track eMI activity in vitro with isolated LE/MVBs and in cells in culture using fluorescent reporters and highlight approaches to distinguish whether a protein is a substrate of eMI or CMA.

Keywords: autophagy, chaperones, late endosomes, multi-vesicular bodies, organelle isolation, proteostasis, protein degradation, protein targeting

Introduction

Protein homeostasis (proteostasis) is essential to maintaining a well-functioning proteome. Failure of proteostasis network components, namely chaperones and proteolytic systems, has been shown to contribute to proteotoxicity in aging (Kaushik & Cuervo, 2015) and in a variety of protein conformational disorders, including neurodegenerative diseases (Nixon, 2013; Menzies, Fleming et al., 2017; Scrivo, Bourdenx, Pampliega & Cuervo, 2018). Autophagy, which refers to endolysosomal degradation of intracellular components, is an essential player in cellular proteostasis. Several types of autophagy co-exist in most cells, including macroautophagy, which degrades cytosolic contents sequestered through the formation of an autophagosome and subsequent fusion with a lysosome, the organelle with the highest proteolytic activity in the cell (Feng, He, Yao & Klionsky, 2014). Chaperone-mediated autophagy (CMA) is another form of autophagy that allows for the selective degradation of individual cytosolic proteins based on the recognition of a pentapeptide, KFERQ-like motif in their sequence by the heat shock cognate 71kDa protein (hsc70) (Tekirdag & Cuervo, 2018). The unique feature of CMA is its dependence on a receptor protein at the lysosomal membrane, the lysosome-associated membrane protein type 2A (Cuervo & Dice, 1996) which mediates direct translocation of the substrate protein across the lysosomal membrane (Bandyopadhyay, Kaushik, Varticovski & Cuervo, 2008). A third way in which degradation of autophagic cargo can be attained is through its internalization via invaginations of the membranes of organelles in the endolysosome system, which then seal into small vesicles and pinch off from the membrane for luminal degradation (Ahlberg & Glaumann, 1985). This process, generically known as microautophagy, can degrade organelles (eg. peroxisomes, ER, nucleus) (Sakai, Koller et al., 1998; Bo Otto & Thumm, 2020; Schafer, Schessner et al., 2020), protein complexes such as the proteasome (Li & Hochstrasser, 2020) and single proteins (Sahu, Kaushik et al., 2011; Mejlvang, Olsvik et al., 2018) giving rise to different microautophagy sub-types.

In this work, we focus on the methods to analyze one sub-type of microautophagy that mediates degradation of cytosolic proteins in late endosome/multi-vesicular bodies (LE/MVB), which is known as endosomal microautophagy (eMI) (Sahu, Kaushik et al., 2011). eMI can take place “in bulk” or selectively upon binding of hsc70, like in CMA, to the KFERQ-like motif in the sequence of the substrate protein; however, instead of lysosomes, substrates are shuttled to LE/MVB through direct binding of hsc70 to phosphatidylserine residues on the LE/MVB membrane (Morozova, Clement et al., 2016). Members of the endosomal sorting complexes required for transport (ESCRT) machinery, including Vps4 and Tsg101, then assemble around this area and form an invagination of the membrane to internalize the substrate inside intraluminal vesicles (ILV) (Sahu, Kaushik et al., 2011). eMI substrates may be degraded in the LE/MVB itself, or upon their fusion with a lysosome. Although other types of eMI (independent of hsc70) are activated early in the response to nutrient deprivation (Mejlvang, Olsvik et al., 2018), hsc70-dependent eMI, the focus of this work, is not upregulated in those conditions (Sahu, Kaushik et al., 2011) and instead, eMI activity gradually decreases as starvation persists (Krause et al., in preparation). This response in mammals is in clear contrast with the induction of eMI by starvation in flies, a model system where eMI has also been described (Mukherjee, Patel et al., 2016). Genotoxic and oxidative stress also upregulates eMI in flies (Mesquita, Glenn & Jenny, 2020), although in these cases, the dependence on hsc70 is only partial, making it important to differentiate between hsc70-dependent and hsc70-independent types of eMI. Studies in flies support a role for hsc70-dependent eMI in synapse remodeling through selective degradation of synaptic proteins involved in neurotransmitter release (Uytterhoeven, Lauwers et al., 2015). In mammals, eMI has been shown to contribute to the physiological degradation of neurodegeneration-related proteins such as tau, but not of the pathogenic forms of this protein, which instead interfere with eMI activity (Caballero, Wang et al., 2018). Blockage of eMI in this context occurs at different steps (binding, internalization or degradation) depending on the pathogenic tau variant (Caballero, Wang et al., 2018), thus highlighting the importance of using methods that can separately analyze each of these steps in eMI. In this work, we describe methods to assess the activity and different steps of hsc70-dependent eMI activity in mammals using isolated LE/MVBs from rodents and mammalian cultured cells. Since KFERQ-containing proteins identified by hsc70 can undergo degradation by both eMI and CMA, we have also included a section detailing criteria to determine whether a given protein is undergoing degradation by eMI or CMA.

1. Biochemical procedures for assessment of eMI activity in mammals

The protocols outlined in this section detail a method to isolate the LE/MVB compartment from mouse liver tissue using discontinuous Percoll® density gradient centrifugation (modified from (Castellino & Germain, 1995)) and two procedures that can be used to compare eMI activity across conditions: 1) analysis of differences in LE/MVB association and degradation of endogenous eMI substrates and 2) reconstitution of eMI in vitro with previously characterized eMI substrates (Sahu, Kaushik et al., 2011).

Materials

Conical polypropylene centrifuge tubes (15ml and 50ml)

Pipet-aid and serological pipettes

1.5ml microcentrifuge tubes

Bulb plastic Pasteur pipettes

Round-tip glass Pasteur pipette (generated by flaming regular glass Pasteur pipettes)

Open-top thin-wall Ultra-clear centrifuge tubes (Beckman Coulter, Catalog # 344059)

Open-top thick-wall polypropylene 38.5ml centrifuge tubes (Beckman Coulter, Catalog # 355642)

Plastic Syringes (1ml) with 25-gauge needle

Micropipettes (0.2-10μl, 1-20μl, 20-200μl, 100-1000μl) and tips

Plastic funnel and gauze pads

Equipment

Ultracentrifuge eg. Beckman Coulter XPN-90 ultracentrifuge

Teflon pestle and 55ml Glass homogenizer (Wheaton)

Benchtop centrifuge with refrigeration eg. Beckman-Coulter Allegra 64R with rotors F0630 and F2402H

Beckman Coulter SW41 Ti rotor

Benchtop vacuum outlet and tubing

Reagents

Homogenization buffer: 0.25M sucrose; 1mM EDTA in ddH2O, pH 7.4. Prepare fresh and keep at 4°C.

Sucrose cushion solution: 2.5M sucrose; 20mM HEPES in ddH2O, pH 7.4. Store at −20°C

MOPS-Sucrose: 0.25M sucrose; 10mM MOPS in ddH2O, pH 7.3. Prepare fresh and keep at 4°C.

Percoll® density gradient media liquid (suspension) (GE Healthcare)

Purified recombinant human tau 2N4R (Rpeptide, Catalog # t-1001-2) or purified native rabbit GAPDH (Fitzgerald, 30R-AG005).

Protease inhibitor cocktail (x10 for final concentration of 100 μM leupeptin, 100 μM AEBSF, 10 μM pepstatin and 1 mM EDTA in ddH2O). Store at −20°C in small aliquots.

Phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (EMD Millipore, Catalog # 524625)

Leupeptin hemisulfate (Sigma, Catalog # L5793)

Sterile 0.9% saline

Ponceau S stain: Ponceau S (Sigma, Catalog # P3504), 0.1% (w/v) in 1% acetic acid (v/v) (Romero-Calvo, Ocon et al., 2010)

1.1. Isolation of LE/MVB from mouse liver

Dissect mouse liver and place in 20ml of homogenization buffer in 50ml conical tube on ice. Wash liver twice with ice cold homogenization buffer to remove traces of blood (See Note 1).

Decant homogenization buffer and use scissors to mince the liver into small pieces. After mincing, add 3ml of homogenization buffer to the minced liver.

Transfer the minced liver to a 55ml glass homogenizer. Homogenize using a Teflon pestle at maximum speed for 10-12 strokes. (See Note 2)

Filter the homogenized liver through a funnel with double gauze into a 38.5ml centrifuge tube.

Save a small aliquot of homogenate (50μl) in a microcentrifuge tube on ice with protease and phosphatase inhibitors added to a 1x concentration.

Centrifuge the liver homogenate at 2000xg for 5 minutes at 4°C in a benchtop centrifuge.

Collect the resulting post-nuclear supernatant (PNS) and transfer into a 15ml conical tube. (See Notes 3, 4)

To generate the first Percoll® gradient, add 1ml of the sucrose cushion solution to the bottom of a thin-walled ultraclear centrifuge tube secured on ice. Then, add 9mL of 27% Percoll® in homogenization buffer (6.57ml of homogenization buffer and 2.43ml of Percoll®). Keep the gradient tube on ice and, at the top of the gradient, layer the PNS from the prior step (approximately 2ml that are brought to a final of 2.5ml with homogenization buffer).

Place the tubes in the ultracentrifuge buckets of an SW41 Ti rotor and spin at 33000xg for 1 hour and 5 minutes at 4°C using an acceleration setting of 170rpm/3min and deacceleration setting of 170rpm/4min.

At the end of the first ultracentrifuge spin, the band on top of the 27% Percoll® gradient corresponds to a mixture of Golgi, early endosomes, and late endosomes. Use a glass Pasteur pipette connected to a vacuum outlet to remove the extra homogenization buffer from the top of this band. Remove this top band with a plastic Pasteur pipette (approximately 1 ml) and place into a 15ml conical tube. Dilute this top band to 2.5ml with homogenization buffer. (See Note 5)

To generate the second Percoll® gradient, add 1ml of the sucrose cushion solution to the bottom of a thin-walled ultraclear centrifuge tube secured on ice. Then, add 9ml of 10% Percoll® in homogenization buffer (900 μl of Percoll® in 8.1 ml of homogenization buffer) and layer at the top of the gradient the 2.5 ml of sample diluted from the prior gradient.

Place the tubes in the ultracentrifuge buckets of an SW41 Ti rotor and spin at 33000xg for 1 hour and 5 minutes at 4°C. Use the same acceleration and deacceleration settings as in step 9.

At the end of the second ultracentrifuge spin, the bottom band above the 2.5M sucrose layer contains the late endosome fraction. Use a glass Pasteur pipette connected to a vacuum outlet to remove the layers of the gradient until reaching the late endosome band. Transfer the late endosome band (approximately 1 ml) into a clean thin-walled ultraclear tube. (See Note 6)

After collecting the late endosomes in the clean thin-walled ultraclear tubes, fill the tubes with homogenization buffer and centrifuge the samples using an SW41 Ti rotor at 100000xg for 17 minutes at 4°C. Use maximal acceleration and deacceleration.

Use a glass Pasteur pipette connected to a vacuum outlet to remove the homogenization buffer from the first wash. Resuspend the late endosome pellet mechanically with a blunted round-tip glass Pasteur pipette using single direction short strokes against the wall of the bottom of the ultraclear tube and then fill with homogenization buffer to the top. Repeat the washing spin from step 14.

After the second washing step, remove the homogenization buffer, resuspend the late endosome pellet with a round-tip glass Pasteur pipette and add 0.5ml of homogenization buffer to transfer the late endosome suspension to a 1.5ml microcentrifuge tube.

Pellet the late endosomes by spinning at 25000xg for 5 minutes at 4°C.

Remove the homogenization buffer and resuspend the late endosomes using a round-tip glass Pasteur pipette as in step 15. Add the desired amount of MOPS-Sucrose to preserve the late endosomes for functional studies (See Notes 7, 8) (Figure 1).

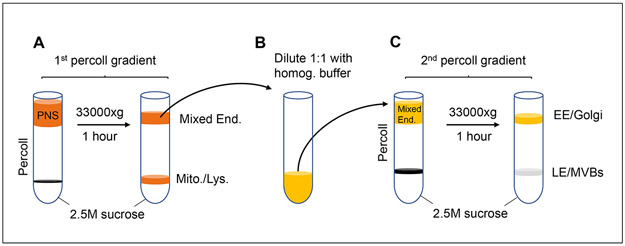

Figure 1: Scheme of late endosome/multi-vesicular bodies (LE/MVBs) isolation.

Isolation of LE/MVB is attained after tissue homogenization by differential centrifugation to obtain a post-nuclear supernatant (PNS) that is further fractionated by sequential centrifugation through discontinuous density Percoll® and sucrose gradients as depicted. Briefly, the PNS is fist layered on top of a 2.5M sucrose cushion and 27% Percoll® layer gradient and centrifuged to eliminate mitochondria and lysosomes through the Percoll® layer (A). The remaining organelles collected at the top of the gradient are then diluted in homogenization buffer (B) and layered on top of a second 2.5M sucrose cushion/10% Percoll® layer gradient. Upon centrifugation, LE/MVB migrate through the 10% Percoll® layer and can be collected at the interface of the sucrose/Percoll® layers, whereas early endosomes (EE) and Golgi fractions remain at the top of the gradient (C).

1.2. Detection of endogenous eMI substrates in isolated LE/MVBs

-

1.

Four hours before euthanasia, inject mice intraperitoneally mice with 30mg/kg of leupeptin dissolved in 0.9% saline or 0.9% saline alone as a control. Leupeptin will prevent degradation inside lysosomes and late endosomes (Moulis & Vindis, 2017).

-

2.

Perform an LE/MVB isolation as in protocol 1.1.

-

3.

Prepare equal amounts of total protein per sample for immunoblot (25-75 μg per lane, depending if detection is intended for endogenous resident proteins or for substrates, respectively). Process samples for standard reducing SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) followed by wet electrotransfer onto a nitrocellulose membrane (Laemmli, 1970; Smith, 1984; Towbin, Staehelin & Gordon, 1992).

-

4.

Before blocking, perform Ponceau staining of the membrane to normalize the immunoblot for single proteins to the total protein loaded for each sample (Romero-Calvo, Ocon et al., 2010).

-

5.

Perform membrane blocking and incubation with primary and secondary antibodies following published protocols on immunoblotting (Smith, 1984) (See Note 9).

-

7a.

To compare eMI activity across conditions, the most informative procedure is to quantify eMI flux of known substrates directly in LE/MVBs (which will discard degradation by other autophagic pathway). To do this, perform immunoblot for established KFERQ-containing eMI substrates (i.e. GAPDH) and after densitometric analysis, first normalize the intensity of the eMI substrate to the total protein loaded per lane based on the Ponceau stain. Use the normalized values to calculate the increase in levels of the eMI substrate in LE/MVB from leupeptin injected animals compared to the average intensity of the same protein in all saline injected samples. Comparison of flux of known eMI substrates in LE/MVBs among conditions will help establish whether there are changes in eMI activity (See Note 10).

-

7b.

To quantify possible eMI degradation of a given protein, similar flux analysis as described above (in 7a) can be performed for any protein of interest. If the protein of interest is more abundant in LE/MVB from leupeptin injected animals than from saline injected animals (ratio>1.2), it suggests that this protein is degraded in LE/MVBs and may be an eMI substrate (See Notes 11, 12).

1.3. In vitro reconstitution of eMI with isolated LE/MVBs

eMI activity can be assessed in isolation of other cellular processes using the LE/MVB fraction obtained from rodent tissue in protocol 1.1 (Sahu, Kaushik et al., 2011).

Right after isolation, quantify the total amount of protein isolated in each LE/MVB fraction to ensure equal amounts of LE/MVB are used per tube (an average of 20μg of total LE/MVB protein per tube are used for reconstitution assays) (See Note 13).

To assess eMI activity, isolated LE/MVBs will be presented with an excess of purified protein of a known eMI substrate. Tau (Caballero, Wang et al., 2018) and GAPDH (Sahu, Kaushik et al., 2011) are well-established eMI substrates suitable for use in this experiment. Lyophilized purified protein should be dissolved in ddH2O to a concentration of 1 μg/μl and stored at −20°C in single use aliquots. The working solution (2.5 ng/μl) is prepared from this stock using MOPS-sucrose buffer at the moment of the experiment (See Note 14).

This experiment measures the binding of the substrate protein to LE/MVBs when protein degradation has not been inhibited in the isolated organelles, and association of a substrate to LE/MVBs, when proteolysis in the lumen has been inhibited by pre-incubation of the isolated LE/MVB with protease inhibitors. To ensure optimal inhibition of proteases, LE/MVBs should be incubated with a 10x protease inhibitor cocktail for 10 minutes on ice and LE/MVBs dedicated to measure binding should be incubated in the same conditions, but replacing protease inhibitors with an equivalent amount of MOPS-sucrose buffer (See Note 15, 16).

Tubes containing 25 ng of the substrate protein (10μl of the 2.5ng/μl working solution) in a volume of MOPS-sucrose enough to bring the final volume to 30μL when the LE/MVB will be added can be prepared beforehand during the incubation on ice of the LE/MVB.

Add 20μg of LE/MVB to each experimental tube containing the eMI substrate protein and quickly spin down the tubes at a low speed to ensure mixing of all tube contents at the bottom of the tube.

Incubate the tubes at 37°C for 30 minutes.

Immediately after the incubation, spin the tubes down in a benchtop centrifuge at 25000xg for 5 minutes at 4°C.

Remove the supernatant, being careful to not disturb the LE/MVB pellet and add 200μl of MOPS-sucrose against the tube wall for a second wash, repeating the spin in step 8.

Remove the washing solution and add 20μl of MOPS-sucrose with protease inhibitors to resuspend the LE/MVB pellet. Add 1x Laemmli loading buffer with protease inhibitors and subject samples to standard SDS-PAGE.

To be able to quantify the percentage of added eMI substrate (input) bound and internalized by LE/MVB, an equivalent amount of the input protein should be run in the same gel by preparing a tube with 25ng of exogenous substrate and, after adding 1x Laemmli loading buffer, processing it for standard SDS-PAGE in the same gel (Laemmli, 1970; Towbin, Staehelin et al., 1992).

Transfer the SDS-PAGE gel with the experimental samples and the input sample to a nitrocellulose membrane (Towbin, Staehelin et al., 1992) and develop the membrane using an antibody targeting the added exogenous substrate

After densitometric quantification of the membrane, calculate the percentage of the “input” protein detectable in the pelleted LE/MVB in each experimental condition. The percentage of input protein detected in LE/MVB not incubated with protease inhibitors indicates the amount of substrate binding that has occurred and in LE/MVB pre-incubated with protease inhibitors indicates the overall amount of substrate associated to the LE/MVBs (See Note 17).

To calculate the amount of substrate protein that has been taken up and degraded by the LE/MVBs, subtract the amount of protein bound to the LE/MVB from the amount of protein associated to the LE/MVBs (See Note 18) (Figure 2).

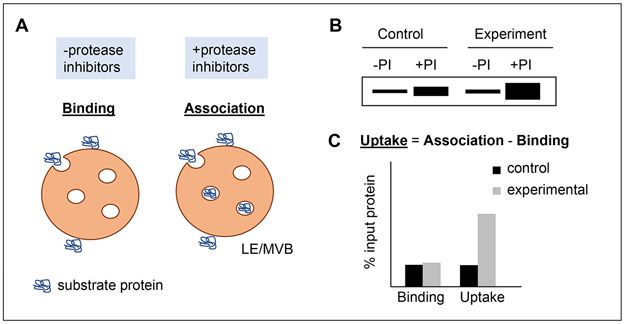

Figure 2: in vitro reconstitution of eMI with isolated LE/MVBs.

A. Scheme of the reconstitution of the different steps of eMI in vitro by presenting purified substrate protein to LE/MVBs pre-incubated or not with protease inhibitors (PI). In the case of LE/MVB not incubated with protease inhibitors, the substrate protein binds to their membranes and it is degraded upon internalization. When LE/MVBs are recovered by centrifugation at the end of the incubation, only membrane-bound protein remains, allowing for measurement of substrate binding. In the case of LE/MVBs incubated with PI, the internalized protein remains undegraded and can be used to measure total substrate association with the LE/MVBs. Binding: protein at the membrane. Association: protein bound to the membrane and internalized. B, C. Theoretical example of the immunoblot pattern (B) and quantification (C) of eMI flux using LE/MVB from a control and an experimental condition and incubating them with the substrate protein. eMI degradation is calculated by subtracting substrate binding (−PI condition) from substrate association (+PI condition), which are both expressed as the percentage of input protein used in the incubation.

Notes

It is possible to isolate LE/MVB from cultured cells as described in (Sahu, Kaushik et al., 2011). Although the large amount of starting material provided by animal organs results in a higher yield of LE/MVBs. Although it is technically possible to isolate LE/MVBs from frozen tissue (our group has had success isolating functional LE/MVBs from frozen human brain tissue), the yield and integrity of the organelles is substantially better in fresh tissue, which becomes important for efficacy of the in vitro reconstitution assays .

Homogenization should be done either in a cold room or by placing the glass homogenizer in an ice bucket during the tissue disruption.

All steps handling samples with isolated organelles in protocol 1.1 should be done with plastic bulb Pasteur pipettes to avoid shear stress on the organelle membranes.

A small sample (50-100μL) of the PNS can be saved to obtain cytosol as the supernatant resulting from centrifugation of PNS at 100000xg for 1 hour at 4°C in a fixed angle rotor.

At the end of the first gradient, the bottom band at the interface of the 27% Percoll® layer and the sucrose cushion contains a mixture of lysosomes and mitochondria. This band can be collected by transferring to a 38.5ml centrifuge tube and washing in 18ml of homogenization buffer. The samples should then be centrifuged at 37000xg for 15 minutes at 4°C. Samples can then be resuspended in the desired volume of homogenization buffer and kept with protease and phosphatase inhibitors.

At the end of the second gradient, the top band contains a mixture of early endosomes, recycling endosomes, and Golgi.

LE/MVBs can also be saved as a pellet and stored at −80°C for long term storage.

For studies comparing different experimental conditions, the efficiency of the isolation and purity of the fractions should be analyzed in all samples. For that purpose, it is important to keep track of the original total homogenate volume and exact volumes in which fractions are resuspended. The efficiency of the isolation can be monitored by calculating the percentage of markers for late endosomes present in the homogenate recovered in the isolated fraction, for example by densitometric quantification of immunoblots using known late endosome marker proteins, such as LAMP-1 and Rab7. Purity should be confirmed by checking for absence of contaminating organelles using representative markers in the same immunoblots. Possible contaminant organelles are mitochondria, peroxisomes and secondary lysosomes. Cytosolic contamination is minimized through the multiple washes of the recovered fractions.

To determine the efficacy of leupeptin injection, it is advisable to include positive controls of known lysosomal substrates such as changes in the level of LC3-II by immunoblot (LC3 flux) in homogenates of tissues from leupeptin and saline injected animals (Moulis & Vindis, 2017).

Because the LE/MVB compartment has a lower proteolytic capacity than lysosomes, the basal fold change in levels of eMI substrates like GAPDH in LE/MVBs after leupeptin injection will be approximately 1.2-fold higher than saline injected controls. Increases or decreases in this fold will inform on changes in eMI activity. Additional studies (see below) will be required to determine the specific type of eMI responsible for the observed change in overall eMI activity.

To further discriminate between proteins present in LE/MVBs for degradation from those constitutively in this compartment, the stability of the protein of interest can be tested in LE/MVBs isolated from uninjected animals by incubating them at 37 °C in the presence and absence of protease inhibitors. A reduction in levels of the protein of interest in LE/MVBs at the end of the incubation that is prevented by incubation with protease inhibitors would suggest that the protein is degraded by the LE/MVB and may be an eMI substrate.

It is possible to identify differences in the pool of substrates that are degraded by eMI using comparative proteomics between two conditions (i.e. LE/MVB from resting and stress-induced animals).

To maintain equivalent final volumes and substrate protein to LE/MVB ratios in the tubes for eMI transport, it is useful to dilute all LE/MVB samples to the same concentration.

Purified proteins that can only be obtained in solution or suspension instead of as lyophilized powder need to be dialyzed right before use against MOPS-sucrose to remove salts and bring the solution to isotonicity with LE/MVB.

The MOPS-sucrose buffer used for functional LE/MVB experiments should be made fresh within 2-3 days of the planned experiment to ensure optimal results and stored at 4 °C.

This protocol does not require the addition of exogenous hsc70 because isolated LE/MVBs retain the membrane-bound hsc70 that is utilized for substrate binding/internalization when reconstituting eMI in vitro. In fact, hsc70 added to the assay displaces the already bound hsc70 making it possible to inhibit eMI by the addition of mutant forms of hsc70 protein to the assay, as shown in (Morozova, Clement et al., 2016). We have not found differences in the efficacy of binding and internalization of substrate proteins in the presence or absence of ATP, which make us suspect that part of the membrane bound hsc70 is already bound to ATP and that ATP binding, but not hydrolysis, is required for the role of hsc70 in eMI. The contribution of in-bulk eMI in this experimental setting (measured as internalization of non-KFERQ containing proteins such as cyclophilin) is negligible (less than 1% of that observed with KFERQ-containing substrates).

In those instances in which it becomes important to differentiate between substrate proteins bound to the LE membrane from the ones internalized but still in the lumen of ILVs and consequently not degraded, LE/MVBs can be treated with trypsin, which will degrade proteins bound to the cytosolic side of the LE membrane but not those that are inside the LE lumen (Bandyopadhyay, Sridhar et al., 2010). Controls of the efficiency of full trypsinization without disruption of the LE membrane include immunoblot for luminal proteins such as LAMP-1 or cathepsin (that should remain trypsin-insensitive) and for membrane-bound proteins such as Vps4 or Rab7 (that should be fully degraded upon trypsinization).

Due to the fact that LE/MVBs are in suspension, which increases possible experimental variability when pipetting between tubes, it is recommended that binding and uptake experiments be done in triplicate for each condition from the same LE/MVB batch and values averaged as a single experiment.

2. Image-based procedures for assessment of eMI activity in cultured cells

The following section describes methods that allow for the dynamic measurement of eMI flux in living cells, which is the gold-standard for the study of autophagy pathways. Thus far, the protocols described have focused only on selective KFERQ-dependent eMI, but this section will also describe a tool to study in bulk, non-selective eMI. The fluorescent reporter used to measure both types of eMI utilizes a split-fluorescent protein system that works as a coincidence detector: when both protein fragments are sequestered in an ILV of an MVB, they will associate together and produce a fluorescent signal (Uytterhoeven, Lauwers et al., 2015; Caballero, Wang et al., 2018). In the case of selective eMI, both fragments of this split fluorescent protein have a KFERQ motif tag for recognition by hsc70 while for in bulk eMI, there is no attached targeting motif (Uytterhoeven, Lauwers et al., 2015; Caballero, Wang et al., 2018).

Materials

15ml polypropylene conical tubes

10cm polystyrene cell culture plates

1.5ml microcentrifuge tubes

Glass slides

Coverslips

6-well polystyrene cell culture plates

Equipment

Cell culture chamber incubator (37°C, 5% CO2).

Cell culture laminar flow hood safety level II

Bench top refrigerated centrifuge with swinging bucket rotor (eg. Eppendorf 5804 centrifuge with swinging bucket rotor and adaptors for 15ml conical tubes)

Hemocytometer

Fluorescence microscope with 40x and 63x objectives and filters for DAPI (excitation filter 375/28 nm, barrier filter 460/60 nm) and FITC (excitation filter 480/30 nm, barrier filter 535/45 nm)

Reagents

0.05% Trypsin-EDTA (Invitrogen, Catalog #25300062)

Cell culture media supplemented with serum and antibiotics as recommended for the cell type of choice. Store at 4°C.

10mg/ml polybrene (American Bio, Catalog # AB01643-00001). Store at −20°C.

Lentiviral particles containing Split Venus reporter constructs (Caballero, Wang et al., 2018). Store at −80°C.

NIH3T3 cells, or preferred cell line

DAPI Fluoromount-G (Southern Biotech, Catalog # 0100-20)

Lentiviral particles containing shRNA for Vps4A and Vps4B. Store at −80°C.

Etoposide (Sigma, Catalog # E1383)

Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO)

4% paraformaldehyde (PFA). Store at 4°C.

1X phosphate buffered saline (PBS), pH 7.4.

Ammonium Chloride (NH4Cl)

Leupeptin hemisulfate (Fisher, Catalog # BP2662)

2.1. Generation of cells stably expressing eMI reporters

Plate 50000 cells per well in a 6-well plate the day before planned lentiviral transduction. Please note that the transduction conditions described her are optimized for NIH3T3 cells grown in DMEM with 10% New Born Calf Serum and 1% penicillin/streptomycin.

On the day of the lentiviral transduction, prepare in a 1.5ml microcentrifuge tube a 2x polybrene mixture by adding 0.5ml cell culture medium and 1μL of the 10mg/ml polybrene stock solution.

Aspirate the media from the cells and add the 0.5ml media/polybrene mixture to the cells, followed by 0.5ml of the lentiviral particle suspension.

Twenty-four hours after the transduction, add 1ml of full media to the cells without removing the lentiviral supernatant.

After 48-72 hours of transduction, the cells can be tryspsinized and passaged at the usual dilution ratio. The original vector does not contain antibiotic resistance. If cell selection is needed (in cases of low transduction efficiency), an additional plasmid conferring resistance to an antibiotic of choice (i.e. puromycin) can be co-packed in the lentiviral particle to co-transduce cells with both plasmids. The antibiotic of choice can then be added to the culture media right after trypsinization to maximize the number of transduced cells.

Cells will not display fluorescence except for sites where the two venus protein fragments coincide. To check for transduction efficiency, it is advisable to maximize chances of coincidence of both fragments in LE/MVB by upregulating eMI activity. To do this, grow cells in cell culture dishes with coverslips and treat one coverslip with 1μM etoposide, a known KFERQ-selective eMI activator, for 12 hours and another coverslip with DMSO as a control (Mesquita, Glenn et al., 2020). After the treatment, fix the cells for 20 min in 4% PFA and mount the coverslips on a glass slide with DAPI Fluoromount-G to provide a nuclear stain. When observing samples under the microscope, use a 488nm laser in a confocal microscope or the FITC channel (480/30nm excitation filter) in a fluorescence microscope to visualize Venus fluorescence. As etoposide is a known activator of KFERQ-selective eMI, there should be more eMI activity, observable by an increased number of Venus fluorescent puncta per cell, in cells treated with etoposide (See Notes 1 and 2).

2.2. Assessing KFERQ-selective and in bulk eMI in reporter-expressing cells

When assessing KFERQ-selective or in-bulk eMI activity in cells expressing either the KFERQ-split-Venus or split-Venus reporters, respectively, it is essential to include positive and negative controls. For positive controls, activation of KFERQ-selective eMI can be attained with etoposide (as described in section 2.1). A required negative control for both KFERQ-selective and in-bulk eMI is to knockdown Vps4 expression using shRNA targeting both the Vps4A and Vps4B isoforms (Sahu, Kaushik et al., 2011) which should ablate both eMI processes (See Notes 3 and 4).

When conducting experiments with these reporters, it is possible to assess the binding/internalization of the reporter to the LE/MVB separately from its degradation in that compartment with a combination of 20mM ammonium chloride and 100μM leupeptin treatment (N/L) (Caballero, Wang et al., 2018). Each treatment condition should be performed with and without N/L to perform this type of analysis (See Note 5).

Duration of treatments and experimental conditions should be modified according to the specific experimental question, but as a reference, we typically apply treatments for 16 hours and measure cumulative eMI at the end of the incubation, although this can vary based on the chosen stressor. The N/L should be added for the duration of the treatment to account for changes in degradation during the intervention. However, if needed, early and late changes in eMI degradation can be studied by changing the time at which the N/L treatment is added or the duration of treatment.

At the end of the treatments, remove the media and wash the cells several times with 1xPBS before fixing with 4% PFA for 20 minutes. Apply DAPI Fluoromount-G medium before imaging using a fluorescence microscope.

The most informative measure of eMI activity is the number of Venus fluorescent puncta per cell that can be calculated in at least 10 fields per condition (or > 100 cells). This can be done using different software package for image analysis, including the particle count tool of the free NIH Image J or Fiji softwares (Schindelin, Arganda-Carreras et al., 2012; Schneider, Rasband & Eliceiri, 2012).

To calculate the amount of degradation through eMI in response to a given intervention, compare the number of puncta per cell between the stressor with and without the N/L treatment. To do this, subtract the average puncta per cell from the condition without N/L from the average puncta per cell from the condition with N/L. (See Note 6) (Figure 3).

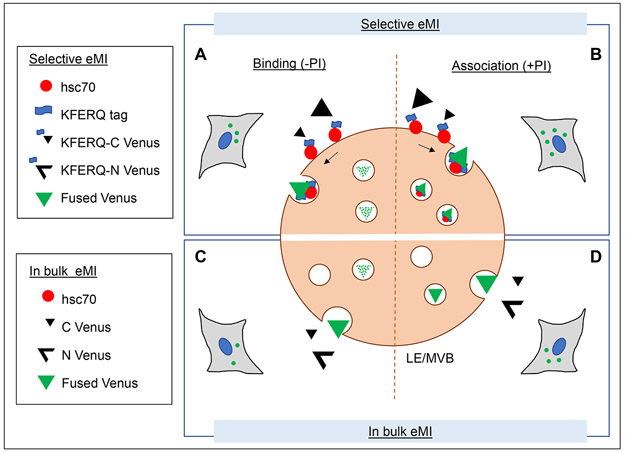

Figure 3: Use of split venus-based reporters for monitoring selective and in-bulk eMI in cultured cells.

A, B: Selective eMI can be measured in cultured cells using a split venus construct where both N and C termini of the venus protein are tagged with a KFERQ sequence (Caballero, Wang et al., 2018). Upon recognition by hsc70, each terminus is separately targeted to late endosomes/multi-vesicular bodies (LE/MVB). When they both coincide inside of the same intraluminal vesicle, venus fluorescence is reconstituted (A). To determine the amount of venus protein degraded by selective eMI in a period of time, cells can be treated with endolysosomal protease inhibitors (PI) to prevent degradation of the internalized fluorescent protein (B). Flux is calculated as the difference of venus fluorescent puncta between cells supplemented (B) or not (A) with PI. C, D: In bulk eMI is measured in cultured cells using a similar split venus construct that lacks the KFERQ-tags in the N and C terminus venus protein fragments. Both fragments are captured when in proximity of a forming invagination in the membrane of LE/MVBs. Binding and internalization are less efficient than for selective eMI, but flux can be calculated in the same way: by comparing the number of venus fluorescent puncta in cells supplemented (D) or not (C) with protease inhibitors.

Notes

If the split-Venus reporter exhibits low fluorescent signal, it may be helpful to perform a qPCR or SDS-PAGE gel to determine if the two fragments of the Venus protein are expressed at similar levels. High differences in the expression ratio can cause difficulty in visualization of the reporter.

Because the Split-Venus reporter is used to measure a low-frequency event, namely two fragments of the Venus protein being targeted to the same ILV via eMI, the signal can be quite low, making it necessary in some instances to impose stressor treatments to determine transduction efficiency, such as the addition of etoposide described in 2.1.

Vps4 is an essential component of selective and in-bulk eMI, as it is responsible for the closure and scission of ILVs into the MVB. There are two isoforms of Vps4, Vps4A and Vps4B, which can compensate for one another, making it necessary to knock down both isoforms to completely block eMI.

Vps4 is involved in many essential cellular processes, making its complete knockdown lethal. We have found that a partial knockdown (of about 40-60%) allows for cells to survive, but still has an impact on eMI activity as measured by the split venus reporter system (Sahu, Kaushik et al., 2011). Partial knockdown can be achieved using a combination of pooled Vps4A and Vps4B shRNAs at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 25. Further details and reference numbers for the shRNA from the Sigma MISSION© shRNA library used against Vps4A and Vps4B can be found in (Sahu, Kaushik et al., 2011).

Aliquots of leupeptin may be frozen and reused, but the NH4Cl solution should be made fresh for each experiment.

For cell types that are difficult to transduce or transfect with reporter constructs, there are alternative, albeit less informative and direct, means of assessing eMI activity in a cell culture model. For example, changes in the abundance of endogenous eMI substrates, such as GAPDH, in LE/MVB (stained with Rab7) upon blockage of intracellular proteolysis with N/L can provide a proxy for how much eMI is occurring in a cell as discussed in (Sahu, Kaushik et al., 2011)

3. Criteria to identify a protein as potential eMI substrate

As described in the introduction section, substrate proteins for both CMA and eMI are recognized by the same chaperone, hsc70, based on the same type of protein motif, a KFERQ-like motif. However, the mechanisms for internalization of substrates in the degradative organelles and the molecular effectors and regulators of eMI and CMA are different. Building on these differences, we include below a check list of features and assays that can be used to determine if degradation of a protein at a given time occurs through eMI or CMA (Table 1). Methods to assess whether a protein is a CMA substrate have been described in detail in the references included in the table, as well as in (Kaushik & Cuervo, 2009; Juste & Cuervo, 2019)

Table 1.

Practical criteria to discriminate between eMI and CMA degradation

| Criteria | Method | Ref | eMI | CMA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KFERQ-like motif | Present in sequence | Sequence analysis using free KFERQ finder software | (Kirchner, Bourdenx et al., 2019) | Yes | Yes |

| Necessary for degradation | Impact of motif disruption by mutagenesis on endolysosomal levels and intracellular flux | (Chiang, Terlecky, Plant & Dice, 1989; Sahu, Kaushik et al., 2011) | Yes | Yes | |

| Sufficient for degradation | No | Yes | |||

| Interacts with | Hsc70 | Binding to GST-hsc70 | (Chiang, Terlecky et al., 1989; Sahu, Kaushik et al., 2011) | Yes | Yes |

| Immunoprecipitation with hsc70 | |||||

| LAMP-2A | Immunoprecipitation with LAMP-2A | (Cuervo & Dice, 1996) | No | Yes | |

| Panning in immobilized lysosomes | |||||

| Intracellular location | Detected in LE/MVB | IF colocalization Vps4/LAMP-1 | (Sahu, Kaushik et al., 2011; Caballero, Wang et al., 2018) | Yes | No |

| IB isolated LE/MVB | |||||

| Detected in CMA active lysosomes | IF colocalization LAMP-2A/hsc70 | (Cuervo, Dice & Knecht, 1997) | No | Yes | |

| IB isolated CMA active lysosomes | |||||

| Degradation dependent on | endolysosomal proteolysis | IF and IB of intracellular levels upon N/L treatment | (Cuervo & Dice, 1996; Cuervo, Dice et al., 1997; Sahu, Kaushik et al., 2011) | Yes | Yes |

| LAMP-2A | IF and IB of intracellular levels upon LAMP-2A knock-down | (Cuervo & Dice, 1996) | No | Yes | |

| ESCRT complexes | IF and IB of intracellular levels upon Vps4A/B, Tg101 or Alix knock-down | (Sahu, Kaushik et al., 2011; Morozova, Clement et al., 2016) | Yes | No | |

| Hsc70 | IF and IB of intracellular levels upon hsc70 knock-down | (Chiang, Terlecky et al., 1989; Cuervo, Dice et al., 1997; Sahu, Kaushik et al., 2011) | Yes | Yes | |

| Hsc70 able to bind PS | IF and IB of intracellular levels upon expression of PS-binding mutant hsc70 | (Sahu, Kaushik et al., 2011; Morozova, Clement et al., 2016) | Yes | No | |

| Nutritional status | Protein lysosomal flux increased by prolonged (>10h) nutrient deprivation | (Cuervo & Dice, 1996; Cuervo, Dice et al., 1997; Sahu, Kaushik et al., 2011) | No | Yes | |

| Translocation | into LE/MVBs | In vitro eMI with isolated LE/MVB | (Sahu, Kaushik et al., 2011; Caballero, Wang et al., 2018) | Yes | No |

| into lysosomes | In vitro CMA with isolated CMA active lysosomes | (Cuervo, Dice et al., 1997) | No | Yes | |

Abbreviations: IF immunofluorescence; IB immunoblot; PS phosphatidylserine

Notes:

Due to compensation among different autophagy pathways (Tekirdag & Cuervo, 2018), blockage of eMI or CMA may not increase the intracellular abundance of KFERQ-like containing proteins as they can be rerouted and efficiently degraded by the other autophagic pathway (Caballero, Wang et al., 2018) However, failure of each of these pathways still has functional consequences because of the different timing and regulation of each of them.

Concluding Remarks

The different forms of autophagy all play an essential role in the maintenance of cellular proteostasis and clearance of toxic protein products from cells. The growing evidence of malfunctioning of different autophagic pathways in aging and in common age-related diseases (Kaushik & Cuervo, 2015) and the disease-specific ways in which each of the autophagic pathways is affected (Nixon, 2013; Menzies, Fleming et al., 2017; Scrivo, Bourdenx et al., 2018) justify current efforts for the development of quantitative procedures to monitor each autophagic pathway and their different steps. A deeper understanding of how these pathways are regulated and interconnected will make their therapeutic targeting possible. Detailed protocols, like the ones provided here, should make the tracking of eMI accessible to a broad group of investigators with interests in autophagy, proteostasis and associated disease conditions.

Acknowledgements.

We thank all of the members of our laboratory for their feedback and contribution to develop and improve many of the methods described in this manuscript. Work in our laboratory is supported by National Institutes of Health grants AG054108, AG021904, AG017617 and AG038072, AG031782, NS100717, the JPB Foundation, the Rainwater Charitable Foundation, the Glenn Foundation and the Backus Foundation and the generous support of Robert and Renee Belfer. GK was supported by a T32-GM007288 from NIGMS and a T32-GM007491 from NIGMS.

References

- Ahlberg J & Glaumann H. (1985). Uptake--microautophagy--and degradation of exogenous proteins by isolated rat liver lysosomes. Effects of pH, ATP, and inhibitors of proteolysis. Exp Mol Pathol, 42, 78–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandyopadhyay U, Kaushik S, Varticovski L & Cuervo AM. (2008). The chaperone-mediated autophagy receptor organizes in dynamic protein complexes at the lysosomal membrane. Mol Cell Biol, 28, (18), 5747–5763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandyopadhyay U, Sridhar S, Kaushik S, Kiffin R & Cuervo AM. (2010). Identification of regulators of chaperone-mediated autophagy. Mol Cell, 39, (4), 535–547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bo Otto F & Thumm M. (2020). Nucleophagy-Implications for Microautophagy and Health. Int J Mol Sci, 21, (12). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caballero B & Wang Y & Diaz A & Tasset I & Juste YR & Stiller B, et al. (2018). Interplay of pathogenic forms of human tau with different autophagic pathways. Aging Cell, 17, (1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castellino F & Germain RN. (1995). Extensive trafficking of MHC class II-invariant chain complexes in the endocytic pathway and appearance of peptide-loaded class II in multiple compartments. Immunity, 2, (1), 73–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang HL, Terlecky SR, Plant CP & Dice JF. (1989). A role for a 70-kilodalton heat shock protein in lysosomal degradation of intracellular proteins. Science, 246, (4928), 382–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuervo AM & Dice JF. (1996). A receptor for the selective uptake and degradation of proteins by lysosomes. Science, 273, 501–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuervo AM, Dice JF & Knecht E. (1997). A population of rat liver lysosomes responsible for the selective uptake and degradation of cytosolic proteins. J Biol Chem, 272, (9), 5606–5615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Y, He D, Yao Z & Klionsky DJ. (2014). The machinery of macroautophagy. Cell Res, 24, (1), 24–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juste YR & Cuervo AM. (2019). Analysis of Chaperone-Mediated Autophagy. Methods Mol Biol, 1880, 703–727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaushik S & Cuervo AM. (2009). Methods to monitor chaperone-mediated autophagy. Methods Enzymol, 452, 297–324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaushik S & Cuervo AM. (2015). Proteostasis and aging. Nat Med, 21, (12), 1406–1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirchner P & Bourdenx M & Madrigal-Matute J & Tiano S & Diaz A & Bartholdy BA, et al. (2019). Proteome-wide analysis of chaperone-mediated autophagy targeting motifs. PLoS Biol, 17, (5), e3000301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli UK. (1970). Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature, 227, (5259), 680–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J & Hochstrasser M. (2020). Microautophagy regulates proteasome homeostasis. Curr Genet, 66, (4), 683–687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mejlvang J & Olsvik H & Svenning S & Bruun JA & Abudu YP & Larsen KB, et al. (2018). Starvation induces rapid degradation of selective autophagy receptors by endosomal microautophagy. J Cell Biol, 217, (10), 3640–3655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menzies FM & Fleming A &Caricasole A & Bento CF & Andrews SP & Ashkenazi A, et al. (2017). Autophagy and Neurodegeneration: Pathogenic Mechanisms and Therapeutic Opportunities. Neuron, 93, (5), 1015–1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesquita A, Glenn J & Jenny A. (2020). Differential activation of eMI by distinct forms of cellular stress. Autophagy, 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morozova K & Clement CC & Kaushik S & Stiller B & Arias E & Ahmad A, et al. (2016). Structural and Biological Interaction of hsc-70 Protein with Phosphatidylserine in Endosomal Microautophagy. J Biol Chem, 291, (35), 18096–18106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moulis M & Vindis C. (2017). Methods for Measuring Autophagy in Mice. Cells, 6, (2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee A, Patel B, Koga H, Cuervo AM & Jenny A. (2016). Selective endosomal microautophagy is starvation-inducible in Drosophila. Autophagy, 12, (11), 1984–1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nixon RA. (2013). The role of autophagy in neurodegenerative disease. Nat Med, 19, (8), 983–997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero-Calvo I & Ocon B & Martinez-Moya P & Suarez MD & Zarzuelo A & Martinez-Augustin O, et al. (2010). Reversible Ponceau staining as a loading control alternative to actin in Western blots. Anal Biochem, 401, (2), 318–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahu R & Kaushik S & Clement CC & Cannizzo ES & Scharf B & Follenzi A, et al. (2011). Microautophagy of cytosolic proteins by late endosomes. Dev Cell, 20, (1), 131–139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakai Y, Koller A, Rangell LK, Keller GA & Subramani S. (1998). Peroxisome degradation by microautophagy in Pichia pastoris: identification of specific steps and morphological intermediates. J Cell Biol, 141, (3), 625–636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer JA & Schessner JP & Bircham PW & Tsuji T & Funaya C & Pajonk O, et al. (2020). ESCRT machinery mediates selective microautophagy of endoplasmic reticulum in yeast. EMBO J, 39, (2), e102586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schindelin J & Arganda-Carreras I & Frise E & Kaynig V & Longair M & Pietzsch T, et al. (2012). Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat Methods, 9, (7), 676–682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider CA, Rasband WS & Eliceiri KW. (2012). NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat Methods, 9, (7), 671–675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scrivo A, Bourdenx M, Pampliega O & Cuervo AM. (2018). Selective autophagy as a potential therapeutic target for neurodegenerative disorders. Lancet Neurol. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith BJ. (1984). SDS Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis of Proteins. Methods Mol Biol, 1, 41–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tekirdag K & Cuervo AM. (2018). Chaperone-mediated autophagy and endosomal microautophagy: Joint by a chaperone. J Biol Chem, 293, (15), 5414–5424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Towbin H, Staehelin T & Gordon J. (1992). Electrophoretic transfer of proteins from polyacrylamide gels to nitrocellulose sheets: procedure and some applications. 1979. Biotechnology, 24, 145–149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uytterhoeven V & Lauwers E & Maes I & Miskiewicz K & Melo MN & Swerts J, et al. (2015). Hsc70-4 Deforms Membranes to Promote Synaptic Protein Turnover by Endosomal Microautophagy. Neuron, 88, (4), 735–748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]