Abstract

Background

Diuretics are used to reduce blood pressure and oedema in non‐pregnant individuals. Formerly, they were used in pregnancy with the aim of preventing or delaying the development of pre‐eclampsia. This practice became controversial when concerns were raised that diuretics may further reduce plasma volume in women with pre‐eclampsia, thereby increasing the risk of adverse effects on the mother and baby, particularly fetal growth.

Objectives

To assess the effects of diuretics on prevention of pre‐eclampsia and its complications.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group's Trials Register (May 2010).

Selection criteria

Randomised trials evaluating the effects of diuretics for preventing pre‐eclampsia and its complications.

Data collection and analysis

Three review authors independently selected trials for inclusion and extracted data. We analysed and double checked data for accuracy.

Main results

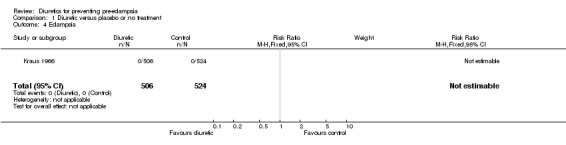

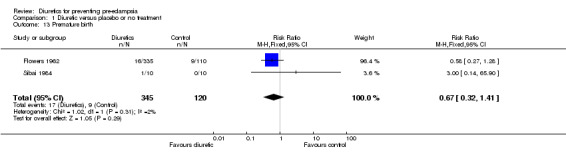

Five studies (1836 women) were included. All were of uncertain quality. The studies compared thiazide diuretics with either placebo or no intervention. There were no clear differences between the diuretic and control groups for any reported pregnancy outcomes including pre‐eclampsia (four trials, 1391 women; risk ratio (RR) 0.68, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.45 to 1.03), perinatal death (five trials,1836 women; RR 0.72, 95% CI 0.40 to 1.27), and preterm birth (two trials, 465 women; RR 0.67, 95% CI 0.32 to 1.41). There were no small‐for‐gestational‐age babies in the one trial that reported this outcome, and there was insufficient evidence to demonstrate any clear differences between the two groups for birthweight (one trial, 20 women; mean difference 139 grams, 95% CI ‐484.40 to 762.40).

Thiazide diuretics were associated with an increased risk of nausea and vomiting (two trials, 1217 women; RR 5.81, 95% CI 1.04 to 32.46), and women allocated diuretics were more likely to stop treatment due to side effects compared to those allocated placebo (two trials, 1217 women; RR 1.85, 95% CI 0.81 to 4.22).

Authors' conclusions

There is insufficient evidence to draw reliable conclusions about the effects of diuretics on prevention of pre‐eclampsia and its complications. However, from this review, no clear benefits have been found from the use of diuretics to prevent pre‐eclampsia. Taken together with the level of adverse effects found, the use of diuretics for the prevention of pre‐eclampsia and its complications cannot be recommended.

Keywords: Female, Humans, Pregnancy, Diuretics, Diuretics/therapeutic use, Pre-Eclampsia, Pre-Eclampsia/prevention & control, Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic

Plain language summary

Diuretics for preventing pre‐eclampsia

Not enough evidence for the use of diuretics for preventing pre‐eclampsia.

Pre‐eclampsia is a serious complication of pregnancy occurring in about 10% of women. It is identified by increased blood pressure and protein in the urine. Initially, women may not experience any symptoms. Constriction of blood vessels in the placenta, a feature of the disease, interferes with food and oxygen passing to the baby, thus slowing the baby's growth and sometimes it causes the baby to be born prematurely. Some women are affected by generalised swelling and, rarely, may have fits. Diuretic drugs cause people to excrete more urine and relax the blood vessels thus reducing the blood pressure. Because of these effects, it has been suggested that these drugs might prevent women from getting pre‐eclampsia. On this basis, these drugs began to be used in pregnancy; however, it was thought that they might interfere with the normal expansion in the blood volume during pregnancy and thus increase the risk of pre‐eclampsia. This review of five randomised controlled trials, involving 1836 women, sought to examine the evidence for diuretics for preventing pre‐eclampsia. All trials compared diuretics with either placebo or no treatment. However, only four trials (1391 women) reported on pre‐eclampsia. There were no significant differences in the outcomes except that diuretics were associated with more nausea and vomiting.

Background

Pre‐eclampsia is diagnosed on the basis of hypertension (raised blood pressure) with proteinuria (protein in the urine) after 20 weeks' gestation (Gifford 2000). This multi‐system disorder complicates between 2% and 8% of all pregnancies (WHO 1988). It is an important cause of maternal and perinatal death worldwide; 10% to 15% of maternal deaths in low‐ and middle‐income countries are associated with the hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (Duley 1992). In the United Kingdom, hypertensive disease of pregnancy remains the second cause of direct maternal deaths (NICE 2001). Even when death is avoided, there is the risk of serious morbidity associated with the disease. Mothers can suffer from eclampsia (seizures), renal failure (kidney damage), disseminated intravascular coagulation (blood clotting disorders), myocardial infarction (heart attacks), cerebro‐vascular accident (stroke), retinal detachment (blindness) and the HELLP syndrome (haemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, low platelets). The baby can have intrauterine growth restriction (fail to grow properly within the uterus) or be born prematurely resulting in complications such as hyaline membrane disease (immaturity of the lungs), intraventricular haemorrhages (brain haemorrhages), and necrotising enterocolitis (bleeding in the bowel). Although many women with pre‐eclampsia have no long‐term problems and give birth to healthy babies, any treatment that can prevent or ameliorate pre‐eclampsia will be of great benefit to pregnant women and their babies. Currently, the only cure for the disease is delivery of the baby and the placenta, but this leads to many babies being born prematurely and vulnerable to the problems described above. Further information on pre‐eclampsia can be found in the generic protocol on interventions for prevention of pre‐eclampsia and its consequences (Generic Protocol 05). This protocol, 'Interventions for preventing pre‐eclampsia and its consequences: generic protocol', was designed as an Health Technology Assessment proposal to assess several interventions for the prevention of pre‐eclampsia in a similar manner.

Several interventions have been suggested for prevention of pre‐eclampsia. Other Cochrane reviews cover calcium supplementation (Hofmeyr 2006), magnesium supplementation (Makrides 2001), energy and protein intake (Kramer 2003), salt intake (Duley 2005), antiplatelet agents (Duley 2003), and antioxidants (Rumbold 2005). Antiplatelet agents were found to have small to moderate benefits, and calcium supplementation appears to be beneficial for women at high risk of gestational hypertension and in communities with low dietary calcium intake. Supplementing women with antioxidants during pregnancy was not associated with a significant reduction in the risk of pre‐eclampsia.

Diuretics are commonly used to treat hypertension in non‐pregnant individuals. They were also formerly used in pregnancy to treat high blood pressure, and delay or prevent the onset of pre‐eclampsia. Historically, the rationale for their use in preventing pre‐eclampsia was based on the incorrect supposition that excess sodium (as salt) intake and retention caused the disease. As diuretics promote excretion of sodium and decrease oedema and blood pressure in non‐pregnant people, it was assumed that they would be beneficial in preventing pre‐eclampsia. In the 1960s, the prophylactic use of thiazide diuretics in pregnancy was advocated to protect the mother from pre‐eclampsia and reduce perinatal mortality and prematurity (Finnerty 1966). This practice became widespread, with up to 40% of pregnant women being given continuous diuretic therapy in pregnancy (Gray 1968). Women with essential hypertension are at increased risk of superimposed pre‐eclampsia, presenting as de novo proteinuria after 20 weeks' gestation. These women in particular were thought likely to benefit from diuretic therapy.

The use of diuretics in pregnancy became controversial with increasing evidence of the reduction of plasma volume (the non‐cellular part of the blood) in pre‐eclampsia (Hays 1985). Women who use diuretics from early pregnancy do not increase their plasma volume to the degree usual in normal pregnancy (Sibai 1984). There were theoretical concerns that diuretics might worsen the existing hypovolaemia (low blood plasma volume) in women with pre‐eclampsia, with adverse effects on the mother and fetus, particularly fetal growth (Gifford 2000). However, there is no firm clinical evidence that diuretics cause harm in pregnancy. Indeed, although the acute blood pressure lowering effect of thiazide diuretics is due to plasma volume contraction, over several weeks renal (kidney) compensatory mechanisms return plasma volume towards normal levels. Cardiac output returns to pretreatment levels, but total peripheral vascular (blood vessel) resistance remains low. The sustained blood pressure lowering effect of thiazide diuretics is thought to involve mobilisation of excess sodium from the arteriolar (blood vessel) wall, with widening of the vessel lumen (Mabie 1986). This might theoretically be of benefit in the pathological vasoconstriction (narrowing of blood vessels), which is an important characteristic of pre‐eclampsia.

There have also been case reports of maternal side effects of diuretics in pregnancy including hypokalaemia (low potassium levels), hyponatraemia (low sodium levels), decreased carbohydrate tolerance (increased tendency to diabetes), and pancreatitis. Jaundice and thrombocytopaenia (low platelet levels) have been reported in newborn babies exposed to diuretics in the uterus. It has been suggested that risks of serious side effects may have been overstated due to selected case reporting (Collins 1985).

A non‐systematic review of randomised trials of diuretics in pregnancy in nearly 7000 women appeared to show evidence of prevention of pre‐eclampsia (Collins 1985). This significant effect persisted when trials using oedema (which would be decreased by diuretics) as a diagnostic criteria for pre‐eclampsia were excluded. This might suggest a true decrease in the incidence of pre‐eclampsia with diuretics. However, the authors were concerned that the definitions of pre‐eclampsia used depended heavily on an increase in blood pressure. The apparent prevention of pre‐eclampsia might thus be due solely to diuretics lowering the blood pressure, and not be a true effect. The overall perinatal mortality was not reduced. This early example of a review with pooled analysis stated that many thousands of women would need to be included to assess effects of treatment on rare outcomes such as perinatal mortality (Collins 1985). Our review is primarily interested in the prevention of pre‐eclampsia using diuretics as some confusion remains over this question. A systematic review of the data is needed to address this.

Objectives

The objective of this review was to ascertain if the use of diuretics in pregnancy prevents the onset of pre‐eclampsia. This included both pre‐eclampsia arising in previously normotensive women (with normal blood pressure) and superimposed pre‐eclampsia arising in a woman with chronic hypertension (pre‐existing high blood pressure). The secondary objective of the review was to assess the level of complications and side effects associated with the use of diuretics.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomised controlled trials of diuretics to prevent the development of pre‐eclampsia. We excluded quasi‐randomised trials given their potential for bias.

Types of participants

We included pregnant women, both at high and low risk of pre‐eclampsia but without pre‐eclampsia at trial entry, randomised to treatment with diuretic or another agent, or both. The trials therefore have some heterogeneity in terms of their sample of the pregnant population.

Types of interventions

Prophylactic administration of diuretics of any group (thiazide, loop, etc) during pregnancy when used in order to prevent pre‐eclampsia were included. The treatment with antihypertensives was given before the onset of pre‐eclampsia. We specifically excluded trials investigating treatment of established pre‐eclampsia.

We included the following comparisons:

diuretics versus placebo or no treatment;

diuretics versus other antihypertensive agents.

We excluded trials evaluating diuretics combined with other interventions for prevention of pre‐eclampsia.

Types of outcome measures

Maternal

(a) The development of pre‐eclampsia. The review applied the standard definition of pre‐eclampsia:

in women who are normotensive, this was defined according to Gifford 2000;

in women who are already hypertensive this was defined as the onset of de novo proteinuria after 20 weeks' gestation.

Trials that used acceptable variations of these definitions, or that did not define their outcomes, were still included, and we described definitions, where available, in the table of Characteristics of included studies. (b) Severe morbidity including eclampsia, liver or renal failure, haemolysis, elevated liver enzymes and low platelets syndrome, disseminated intravascular coagulation, stroke and pulmonary oedema. (c) Placental abruption (separation of the placenta from the uterus). (d) Mode of delivery. (e) Maternal death. (f) Adverse drug‐related outcomes.

Fetal

(a) Gestation at delivery. (b) Preterm birth. (c) Birthweight. (d) Small‐for‐gestational age. (e) Admission to special care nursery. (f) Neonatal complications including need for ventilation, number of days ventilated, respiratory distress syndrome (immaturity of the lungs), necrotising enterocolitis (bleeding in the bowel), and intraventricular haemorrhage (brain haemorrhages). (g) Death in baby, including stillbirth, perinatal death, and neonatal death. (h) Adverse drug‐related outcomes.

While we sought all the above outcomes, only those with data appear in the analysis table. Any data not prespecified by the review authors, but reported by the authors, has been clearly labelled as 'not prespecified'.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group's Trials Register by contacting the Trials Search Co‐ordinator (May 2010).

The Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register is maintained by the Trials Search Co‐ordinator and contains trials identified from:

quarterly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL);

weekly searches of MEDLINE;

handsearches of 30 journals and the proceedings of major conferences;

weekly current awareness alerts for a further 44 journals plus monthly BioMed Central email alerts.

Details of the search strategies for CENTRAL and MEDLINE, the list of handsearched journals and conference proceedings, and the list of journals reviewed via the current awareness service can be found in the ‘Specialized Register’ section within the editorial information about the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group.

Trials identified through the searching activities described above are each assigned to a review topic (or topics). The Trials Search Co‐ordinator searches the register for each review using the topic list rather than keywords.

For details of additional searching carried out for the previous version of the review, see:Appendix 1.

We did not apply any language restrictions.

Data collection and analysis

For the methods used when assessing the trials identified in the previous version of this review, seeAppendix 2.

For this update, two review authors independently assessed the new trials for inclusion (Bambas 1971; Urdapilleta 1967) as well as the report already awaiting classification (Landesman 1965). We excluded both the new trials from the review ‐ seeCharacteristics of excluded studies for the reasons for exclusion. We require more information about the Landesman 1965 trial before we can make an assessment.

If new trials are included in future updates, we will use the methods described in Appendix 3.

Results

Description of studies

Details for each included trial can be found in the table of 'Characteristics of included studies'.

This review includes five studies involving 1836 women. All were single centre trials, conducted in the USA.

Participants were both primiparous and multiparous women, randomised at gestations ranging from the first to the third trimester. In two studies, almost all women were black (Fallis 1964; Kraus 1966). Two trials included women with normal blood pressure only (Fallis 1964; Weseley 1962); one trial included women with chronic hypertension only (Sibai 1984); and two trials did not report on blood pressure at trial entry, but it is likely that they included both women with normal and high blood pressure (Flowers 1962; Kraus 1966). Two trials excluded women with proteinuria (Fallis 1964; Weseley 1962) while the remaining trials did not report on proteinuria at trial entry. One trial included women based on presence of excessive weight gain or oedema (Weseley 1962).

Interventions were thiazide diuretics in all studies. Chlorothiazide was used in three studies (Flowers 1962; Kraus 1966; Weseley 1962) (dose 50 mg to 750 mg daily), hydrochlorothiazide in one study (Fallis 1964) and unspecified thiazide diuretics in the remaining study (Sibai 1984). Diuretics were compared with placebo in four studies, and against no treatment in one study (Sibai 1984). Treatment continued until delivery for most. Compliance rates were good for two studies (Fallis 1964; Flowers 1962) but were not reported for the remaining studies. Restricted salt intake was advised in all five studies, although there was a wide range (salt intake of 1.8 g per day up to 5 g per day).

All included trials reported on pre‐eclampsia. Three of the five studies (Fallis 1964; Kraus 1966; Weseley 1962) defined pre‐eclampsia as a systolic blood pressure of at least 140 mm Hg or a rise by more than 30 mm Hg or a diastolic blood pressure of at least 90 mm Hg or a rise by more than 15 mm Hg, with or without proteinuria, or oedema after 24 weeks' gestation. As the definition of pre‐eclampsia no longer includes oedema or a change in blood pressure from the baseline, the number of women reported to have developed pre‐eclampsia is likely to be an overestimate. One study (Flowers 1962) defined pre‐eclampsia as a systolic blood pressure at least 140 mm Hg or diastolic at least 90 mm Hg in previously normotensive women or an appreciable change in blood pressure in women with chronic hypertension. We have reported the data for this outcome in the study by Flowers, as hypertension and not pre‐eclampsia. For the remaining study (Sibai 1984), superimposed pre‐eclampsia was not defined. Perinatal death, for most trials, included stillbirths and neonatal deaths.

Twenty‐eight studies were excluded for various reasons. Details of each excluded study can be found in the table of Characteristics of excluded studies.

Risk of bias in included studies

The quality of all five studies was unclear because there was inadequate reporting of methods used for randomisation and allocation concealment. Four studies were double blinded while one was not blinded (Sibai 1984). Follow up for two studies was complete (Sibai 1984; Weseley 1962) but the remaining three studies had losses to follow up ranging from 8% to 14%.

Effects of interventions

Pre‐eclampsia

After excluding the study by Flowers 1962, where the outcome measured was not considered to be pre‐eclampsia, four trials (1391 women) reported on pre‐eclampsia. There was insufficient evidence to demonstrate any clear differences between the two groups in the risk ratio of pre‐eclampsia (risk ratio (RR) 0.68, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.45 to 1.03). While the summary statistic implies a trend towards a reduction in pre‐eclampsia, the trials showed a high level of heterogeneity at 43% and it was the small study by Fallis 1964 that contributed most to the summary statistic.

Caesarean section

There was no clear difference between the diuretic and control groups in the risk of caesarean section (one trial, 20 women; RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.26 to 3.81).

Adverse drug related outcomes

Diuretics were associated with an increased risk of maternal side effects compared to placebo (one trial, 519 women; RR 8.70, 95% CI 1.19 to 63.60).

Women allocated diuretics were more likely to stop treatment due to side effects compared to those allocated placebo (two trials, 1217 women; RR 1.85, 95% CI 0.81 to 4.22). This was due to unacceptable nausea and vomiting in the diuretics group (two trials, 1217 women; RR 5.81, 95% CI 1.04 to 32.46). Other reasons for stopping treatment included pruritis and rash, weakness or dizziness, and diuresis but there was no clear difference between the groups in the risk of stopping treatment due to these side effects.

Death in child

There was no clear difference between the diuretic and control groups in the risk ratio of perinatal death (five trials, 1836 women, 22 versus 26 deaths; RR 0.72, 95% CI 0.40 to 1.27). The findings were the same when the perinatal deaths were split into stillbirths (five trials, 1836 women; RR 0.60, 95% CI 0.27 to 1.34) and neonatal death (four trials, 1816 women; RR 0.88, 95% CI 0.40 to 1.97).

Premature birth and gestation at delivery

There was insufficient evidence to demonstrate any clear differences between the two groups in the risk of preterm birth (two trials, 465 women; RR 0.67, 95% CI 0.32 to 1.41) or gestation at delivery (one trial, 20 women; mean difference (MD) 0.70 week, 95% CI ‐0.71 to 2.11).

Small‐for‐gestational age and birthweight

There were no small‐for‐gestational‐age babies in the one trial that reported this outcome, and there was insufficient evidence to demonstrate any clear differences between the two groups in birthweight (one trial, 20 women; MD 139 grams, 95% CI ‐484.40 to 762.40).

Other outcomes (not prespecified)

There were no statistically significant differences between the two groups for any other outcomes including hypertension (two trials, 1475 women; RR 0.85, 95% CI 0.68 to 1.08); severe pre‐eclampsia (two trials, 1297 women; RR 1.56, 95% CI 0.26 to 9.17); use of antihypertensive drugs (one trial, 20 women; RR 2.00, 95% CI 0.21 to 18.69); postmaturity (one trial, 20 women; RR 7.00, 95% CI 0.41 to 120.16) and low Apgar scores (one trial, 20 women; RR 3.00, 95% CI 0.14 to 65.90). There were no reported cases of eclampsia (one trial, 1030 women), or neonatal thrombocytopenia (one trial, 1030 women).

Discussion

Diuretics have been widely used in the past to prevent or delay development of pre‐eclampsia. Despite this, few well‐controlled trials have evaluated the potential effects of this intervention. Indeed, the most recent randomised controlled trial we found was reported 22 years ago. Five trials were included in this review. All trials compared diuretics with either placebo or no treatment. At present, there is insufficient evidence to provide reliable conclusions about the effects of diuretics on prevention of pre‐eclampsia and its complications. The use of diuretics was associated with an increased risk of nausea and vomiting, and this was sufficiently severe to lead to the stopping of treatment in some women. However, there is little information on other side‐effects.

The sample size in the trials was small and, even when taken together, the numbers were insufficient to provide any reliable information on clinically important maternal and perinatal outcomes. The quality of all five trials was unclear because of inadequate reporting of methods used for randomisation and allocation concealment, so any results must be interpreted with caution. A number of trials included in a previous review on this topic (Collins 1985) have been excluded from this review because they were quasi‐randomised trials and had a high potential for bias (Campbell 1975; Cuadros 1964; Menzies 1964; Tervila 1971). There was no statistically significant heterogeneity among the trials for any of the reported outcomes.

It was not possible to accurately classify one particular study (Landesman 1965). Indications from within the paper are that it was a controlled clinical trial with two comparison groups, but it could not be ascertained with absolute certainty whether it was a randomised trial. Attempts were made to contact the authors but to date these have not been successful. Because of its size, this study has the potential to significantly alter the results and, therefore, the conclusions of the review. We have left this reference in the studies awaiting assessment category and would welcome any information about this study that would tell us if it was a true randomised controlled trial.

The effects of diuretics on pre‐eclampsia remain unclear not only because of small numbers, but also because of confusion in terminology. The definition of pre‐eclampsia for most trials included hypertension and oedema or proteinuria. Hypertension was defined either as an absolute rise or a relative rise from baseline values. As oedema is no longer considered an important indicator of pre‐eclampsia, and a relative rise in blood pressure is not used to define hypertension, it is likely that the number of women diagnosed with pre‐eclampsia in the trials is an over‐estimation. Data on development of proteinuria were not available from trials. Even if a surrogate outcome such as severe pre‐eclampsia was used, the effects of diuretics remain unclear.

The use of thiazide diuretics was associated with an increased risk of nausea and vomiting and, in two trials, more women in the diuretics group stopped medication due to side effects compared to placebo. Serious maternal side effects, such as pancreatitis, were not reported in any of the trials. Although more women on diuretics developed hypokalemia (serum potassium less than 3.5 mEq/L) in the one trial that reported this outcome for all women (Kraus 1966), the potassium level did not fall below 3 mEq/L. Neonatal jaundice was reported in one trial (Flowers 1962), but these data have not been included in the review as 60% of participants were excluded from the analysis, and so there is a high potential for bias. No cases of neonatal thrombocytopenia occurred in the one trial that reported this outcome (Kraus 1966). The effects of diuretics on other potential risks such as fetal growth restriction are unclear as there are insufficient data for any reliable conclusions.

As no clear benefits of diuretics have been demonstrated, and the possibility of adverse effects remains, currently available evidence does not support the use of diuretics for preventing pre‐eclampsia and its complications.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

There is insufficient evidence to draw reliable conclusions about the effects of diuretics for prevention of pre‐eclampsia. In addition, the incidence of side effects, particularly vomiting, was higher in the group receiving the diuretics. Therefore, at present, diuretics should not be recommended for this purpose in clinical practice.

Implications for research.

As pre‐eclampsia is associated with reduced plasma volume, the use of diuretics for prevention of pre‐eclampsia, based on their ability to reduce oedema and increase sodium excretion, does not appear to be justified. The conclusions of this review presently suggest that further randomised trials to evaluate the effects of diuretics are justified only if it is thought that other effects of diuretics, such as lowering of blood pressure, and inducing vasodilatation provide reasonable theoretical grounds for preventing pre‐eclampsia. Further trials may also be helpful for women with essential hypertension who are receiving diuretics prior to pregnancy, to provide them with reliable advice about the effects of continuing diuretic therapy during pregnancy. Such randomised trials should be well controlled, with adequate sample size. In view of the apparent increase in risk of nausea and vomiting with thiazide diuretics, if further trials are carried out, strategies to reduce this risk such as using a lower dose or alternative agents should be explored.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 31 May 2011 | New search has been performed | Two reports from an updated search excluded (Bambas 1971; Urdapilleta 1967). |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 4, 2003 Review first published: Issue 1, 2007

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 October 2009 | Amended | Search updated. Two reports added to Studies awaiting classification (Bambas 1971; Urdapilleta 1967). |

| 15 May 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Jennifer Batey for translating Bambas 1971.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Search strategy

Authors searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (The Cochrane Library 2005, Issue 2) using this search strategy

#1 PREGNANCY*:ME #2 PREGNANCY‐COMPLICATIONS*:ME #3 PREGNAN* #4 HYPERTENSION:ME #5 HYPERTENS* #6 (TOXAEMI* near PREGNAN*) #7 (TOXEMI* near PREGNAN*) #8 PRE‐ECLAMPSIA:ME #9 PRE‐ECLAMP* #10 PREECLAMP* #11 (PRE next ECLAMP*) #12 ECLAMP* #13 DIURETICS*:ME #14 DIURETIC* #15 ((#1 or #2) or #3) #16 (#4 or #5) #17 ((((((#6 or #7) or #8) or #9) or #10) or #11) or #12) #18 (#13 or #14) #19 (#15 and #16) #20 ((#19 or #15) or #17) #21 (#20 and #18)

Authors also searched EMBASE (2002 to April 2005) using the search strategy listed in the generic protocol (Generic Protocol 05).

Appendix 2. Methods used to assess reports included in previous versions of this review

The following methods were used to assess Fallis 1964; Flowers 1962; Kraus 1966; Sibai 1984; Weseley 1962.

We conducted the review following the procedures outlined in Higgins 2005.

Selection of studies

Two review authors independently and unblinded performed the assessment of trials for inclusion in the review. We resolved any differences of opinion regarding trials for inclusion by discussion. We consulted a third review author if differences could not be resolved.

Assessment of study quality

We assessed all trials for methodological quality using the criteria listed in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2005), with a grade allocated to each trial on the basis of allocation concealment. We scored allocation concealment as (A) adequate concealment of allocation: such as telephone randomisation and the use of consecutively numbered sealed opaque envelopes; or (B) unclear whether adequate concealment of allocation: such as list or table used, sealed envelopes, or study does not report any concealment approach; or (C) inadequate concealment of allocation: such as open list of random number tables, use of case record numbers, dates of birth or days of the week. We excluded quasi‐randomised trials. If there were unexplained imbalances between groups, we excluded these outcomes (or the trial).

In addition, we assigned quality scores to each trial for blinding of outcome assessment and completeness of follow up as follows.

For blinding of assessment of outcome: (A) double‐blind, neither investigator nor participant knew or were likely to guess the allocated treatment; (B) single‐blind, either the investigator or the participant knew the allocation. Or, the trial is described as double‐blind but side‐effects of one or other treatment mean that it is likely that for a significant proportion (at least 20%) of participants the allocation could be correctly identified; (C) no blinding, both investigator and participant knew (or were likely to guess) the allocated treatment; (D) unclear.

Attrition bias: (A) less than 5% of participants excluded; (B) 5.1% to 9.9% of participants excluded; (C) 10% to 19.9% of participants excluded. If 20% or more of participants were excluded, we excluded the data for that outcome.

Data extraction and data entry

Two authors independently extracted data and cross checked these data with the third author. We resolved any discrepancies by discussion. We extracted the data onto 'hard‐copy' data sheets, entered the data into the Review Manager computer software (RevMan 2002), and checked them for accuracy.

Statistical analyses

We carried out statistical analyses using RevMan 2002. We presented results as summary relative risk for dichotomous data, and as weighted mean difference for continuous data, with 95% confidence intervals. We used the I2 statistic to assess heterogeneity between trials. In the absence of significant heterogeneity, results were pooled using a fixed‐effect model. If substantial heterogeneity is detected in future updates (I2 more than 50%), possible causes will be explored and subgroup analyses may be performed. Heterogeneity that was not explained by subgroup analyses was modelled using random‐effects analysis, where appropriate.

Subgroup analyses

We will carry out subgroup analyses based on parity, ethnicity and presence of essential hypertension once more data are available.

Appendix 3. Methods to be used in future updates

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

At least two review authors will independently assess for inclusion all the potential studies we identify as a result of the search strategy. We will resolve any disagreement through discussion or, if required, we will consult a third person.

Data extraction and management

We will design a form to extract data. For eligible studies, at least two review authors will extract the data using the agreed form. We will resolve discrepancies through discussion or, if required, we will consult a third person. We will enter data into Review Manager software (RevMan 2008) and check for accuracy.

When information regarding any of the above is unclear, we will attempt to contact authors of the original reports to provide further details.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors will independently assess risk of bias for each study using the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2008). We will resolve any disagreement by discussion or by involving a third assessor.

(1) Sequence generation (checking for possible selection bias)

We will describe for each included study the method used to generate the allocation sequence in sufficient detail to allow an assessment of whether it should produce comparable groups.

We will assess the method as:

adequate (any truly random process, e.g. random number table; computer random number generator),

inadequate (any non‐random process, e.g. odd or even date of birth; hospital or clinic record number) or,

unclear.

(2) Allocation concealment (checking for possible selection bias)

We will describe for each included study the method used to conceal the allocation sequence and determine whether intervention allocation could have been foreseen in advance of, or during recruitment, or changed after assignment.

We will assess the methods as:

adequate (e.g. telephone or central randomisation; consecutively numbered sealed opaque envelopes);

inadequate (open random allocation; unsealed or non‐opaque envelopes, alternation; date of birth);

unclear.

(3) Blinding (checking for possible performance bias)

We will describe for each included study the methods used, if any, to blind study participants and personnel from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We will consider that studies are at low risk of bias if they were blinded, or if we judge that the lack of blinding could not have affected the results. We will assess blinding separately for different outcomes or classes of outcomes.

We will assess the methods as:

adequate, inadequate or unclear for participants;

adequate, inadequate or unclear for personnel;

adequate, inadequate or unclear for outcome assessors.

(4) Incomplete outcome data (checking for possible attrition bias through withdrawals, dropouts, protocol deviations)

We will describe for each included study, and for each outcome or class of outcomes, the completeness of data including attrition and exclusions from the analysis. We will state whether attrition and exclusions were reported, the numbers included in the analysis at each stage (compared with the total randomised participants), reasons for attrition or exclusion where reported, and whether missing data were balanced across groups or were related to outcomes. Where sufficient information is reported, or can be supplied by the trial authors, we will re‐include missing data in the analyses which we undertake. We will assess methods as:

adequate;

inadequate;

unclear.

(5) Selective reporting bias

We will describe for each included study how we investigated the possibility of selective outcome reporting bias and what we found.

We will assess the methods as:

adequate (where it is clear that all of the study’s pre‐specified outcomes and all expected outcomes of interest to the review have been reported);

inadequate (where not all the study’s pre‐specified outcomes have been reported; one or more reported primary outcomes were not pre‐specified; outcomes of interest are reported incompletely and so cannot be used; study fails to include results of a key outcome that would have been expected to have been reported);

unclear.

(6) Other sources of bias

We will describe for each included study any important concerns we have about other possible sources of bias.

We will assess whether each study was free of other problems that could put it at risk of bias:

yes;

no;

unclear.

(7) Overall risk of bias

We will make explicit judgements about whether studies are at high risk of bias, according to the criteria given in the Handbook (Higgins 2008). With reference to (1) to (6) above, we will assess the likely magnitude and direction of the bias and whether we consider it is likely to impact on the findings. We will explore the impact of the level of bias through undertaking sensitivity analyses ‐ see 'Sensitivity analysis'.

Measures of treatment effect

Dichotomous data

For dichotomous data, we will present results as summary risk ratio with 95% confidence intervals.

Continuous data

For continuous data, we will use the mean difference if outcomes are measured in the same way between trials. We will use the standardised mean difference to combine trials that measure the same outcome, but use different methods.

Dealing with missing data

For included studies, we will note levels of attrition. We will explore the impact of including studies with high levels of missing data in the overall assessment of treatment effect by using sensitivity analysis.

For all outcomes, we will carry out analyses, as far as possible, on an intention‐to‐treat basis, i.e. we will attempt to include all participants randomised to each group in the analyses, and all participants will be analysed in the group to which they were allocated, regardless of whether or not they received the allocated intervention. The denominator for each outcome in each trial will be the number randomised minus any participants whose outcomes are known to be missing.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We will assess statistical heterogeneity in each meta‐analysis using the T², I² and Chi² statistics. We will regard heterogeneity as substantial if T² is greater than zero and either I² is greater than 30% or there is a low P‐value (< 0.10) in the Chi² test for heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

If there are 10 or more studies in the meta‐analysis we will investigate reporting biases (such as publication bias) using funnel plots. We will assess funnel plot asymmetry visually, and use formal tests for funnel plot asymmetry. For continuous outcomes we will use the test proposed by Egger 1997, and for dichotomous outcomes we will use the test proposed by Harbord 2006. If asymmetry is detected in any of these tests or is suggested by a visual assessment, we will perform exploratory analyses to investigate it.

Data synthesis

We will carry out statistical analysis using the Review Manager software (RevMan 2008). We will use fixed‐effect meta‐analysis for combining data where it is reasonable to assume that studies are estimating the same underlying treatment effect: i.e. where trials are examining the same intervention, and the trials’ populations and methods are judged sufficiently similar. If there is clinical heterogeneity sufficient to expect that the underlying treatment effects differ between trials, or if substantial statistical heterogeneity is detected, we will use random‐effects meta‐analysis to produce an overall summary if an average treatment effect across trials is considered clinically meaningful. The random‐effects summary will be treated as the average range of possible treatment effects and we will discuss the clinical implications of treatment effects differing between trials. If the average treatment effect is not clinically meaningful we will not combine trials.

If we use random‐effects analyses, the results will be presented as the average treatment effect with its 95% confidence interval, and the estimates of T² and I².

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

If we identify substantial heterogeneity, we will investigate it using subgroup analyses and sensitivity analyses. We will consider whether an overall summary is meaningful and, if it is, use random‐effects analysis to produce it.

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Diuretic versus placebo or no treatment.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Pre‐eclampsia | 4 | 1391 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.68 [0.45, 1.03] |

| 2 Hypertension (new or worsening) | 2 | 1475 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.85 [0.68, 1.08] |

| 3 Severe pre‐eclampsia | 2 | 1297 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.56 [0.26, 9.17] |

| 4 Eclampsia | 1 | 1030 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 5 Caesarean section | 1 | 20 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.0 [0.26, 3.81] |

| 6 Use of antihypertensive drugs | 1 | 20 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.0 [0.21, 18.69] |

| 7 Maternal side‐effects | 1 | 519 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 8.70 [1.19, 63.60] |

| 8 Intervention stopped due to side‐effects | 2 | 1217 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.85 [0.81, 4.22] |

| 9 Intervention stopped due to side‐effects (by side‐effect) | 2 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 9.1 Nausea and vomiting | 2 | 1217 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 5.81 [1.04, 32.46] |

| 9.2 Pruritis or rash | 1 | 1139 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.50 [0.05, 5.53] |

| 9.3 Weakness or dizziness | 1 | 1139 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.01 [0.25, 4.00] |

| 9.4 Diuresis | 1 | 1139 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.01 [0.18, 22.11] |

| 10 Perinatal death | 5 | 1836 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.72 [0.40, 1.27] |

| 11 Stillbirth | 5 | 1836 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.60 [0.27, 1.34] |

| 12 Neonatal death | 4 | 1816 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.88 [0.40, 1.97] |

| 13 Premature birth | 2 | 465 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.67 [0.32, 1.41] |

| 14 Small‐for‐gestational age | 1 | 20 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 15 Birthweight | 1 | 20 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 139.0 [‐484.40, 762.40] |

| 16 Gestation at birth | 1 | 20 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.70 [‐0.71, 2.11] |

| 17 Postmaturity greater than 42 weeks | 1 | 20 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 7.0 [0.41, 120.16] |

| 18 Apgar score at 5 minutes less than 7 | 1 | 20 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.0 [0.14, 65.90] |

| 19 Neonatal thrombocytopenia | 1 | 1030 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Diuretic versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 1 Pre‐eclampsia.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Diuretic versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 2 Hypertension (new or worsening).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Diuretic versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 3 Severe pre‐eclampsia.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Diuretic versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 4 Eclampsia.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Diuretic versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 5 Caesarean section.

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Diuretic versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 6 Use of antihypertensive drugs.

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Diuretic versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 7 Maternal side‐effects.

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Diuretic versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 8 Intervention stopped due to side‐effects.

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Diuretic versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 9 Intervention stopped due to side‐effects (by side‐effect).

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Diuretic versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 10 Perinatal death.

1.11. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Diuretic versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 11 Stillbirth.

1.12. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Diuretic versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 12 Neonatal death.

1.13. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Diuretic versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 13 Premature birth.

1.14. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Diuretic versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 14 Small‐for‐gestational age.

1.15. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Diuretic versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 15 Birthweight.

1.16. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Diuretic versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 16 Gestation at birth.

1.17. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Diuretic versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 17 Postmaturity greater than 42 weeks.

1.18. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Diuretic versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 18 Apgar score at 5 minutes less than 7.

1.19. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Diuretic versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 19 Neonatal thrombocytopenia.

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Fallis 1964.

| Methods | Randomisation: participants "randomly assigned" to one of two groups. No further information. Allocation concealment: not reported. Blinding: double blind. Completeness of follow up: 6 women (7.5%) excluded from analyses, all from the active group (1 lost to follow up, 1 undelivered at study completion, 4 unable to take medication due to side effects). | |

| Participants | 80 primigravid women at less than 27 weeks' gestation with dBP < 90 and no proteinuria or oedema. | |

| Interventions | Exp: hydrochlorothiazide 50 mg daily. Control: placebo. All medication was taken until delivery. | |

| Outcomes | Woman: pre‐eclampsia (sBP > 140 or rise by > 30 mm Hg or dBP > 90 or rise by > 15 mmHg, with or without proteinuria, or oedema after 24 weeks); medication stopped due to side‐effects; biochemical outcome. Baby: stillbirth; neonatal death. |

|

| Notes | Compliance: > 80% for all participants except 2 who took > 50% of pills. Diet: all new participants given instruction on salt‐restricted diet. Race: 97.5% women randomised were black. For analysis, 100% were black. Single centre. |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Blinding? All outcomes | Low risk | Although blinding was mentioned, no details of the method were given. |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | High risk | All exclusions were in the active arm of the trial. |

| Free of selective reporting? | Low risk | |

| Free of other bias? | High risk | All participants were from one ethnic group, therefore generalisability of the results to a wider population is problematic. |

Flowers 1962.

| Methods | Randomisation: treatment given "at random" to four groups. No further information. Allocation concealment: sealed envelopes with a code known only to the hospital pharmacist. Blinding: double blind. Completeness of follow up: 74 women (14%) excluded from analyses because of excess weight gain/oedema, poor compliance, insufficient data, or intolerance to side effects. Losses from each group: placebo: 18%; diuretic 250 mg: 20%; diuretic 500 mg: 12%; diuretic 750 mg: 5%. | |

| Participants | 519 primiparous and multiparous women, up to 30 weeks' gestation. | |

| Interventions | Exp 1: 134 participants received chlorothiazide 250 mg daily. Exp 2: 141 participants received chlorothiazide 500 mg daily. Exp 3: 110 participants received chlorothiazide 750 mg daily. Control: 134 participants received placebo. All medication was taken until delivery. | |

| Outcomes | Woman: toxaemia (defined as sBP >/= 140 or dBP >/= 90 x 2 in previously normotensive women or appreciable change in BP in women with chronic hypertension); changes in maternal weight (mean) and blood pressure (mean); side effects; intervention stopped due to side effects; biochemical outcomes. Baby: perinatal mortality (fetal deaths and neonatal deaths up to 28 days of life in infants weighing > 1 kg); premature birth (not defined); neonatal jaundice (60% participants excluded for this outcome, so we have not reported it in the review). |

|

| Notes | Compliance: > 80% for 60%‐69% women in all 4 groups. There was a wide variation in compliance in the remaining 30%‐40% of participants in each group. Diet: all participants advised a low sodium diet (1800 mg sodium) at antenatal booking visit. Statistical analysis has been done using two groups only: women in all 3 diuretic arms have been combined and compared with placebo. Single centre. |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | Sealed envelopes were used with the sequence determined by the Pharmacy department. |

| Blinding? All outcomes | Low risk | |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | High risk | There were varying levels of loss to follow up across the groups ranging from 5 to 20%. |

| Free of selective reporting? | Unclear risk | Women in the three treatment arms received different doses of diuretics. In the analysis they were all combined into one group. |

Kraus 1966.

| Methods | Randomisation: "randomised investigation". No further information. Allocation concealment: not reported. Blinding: double blind. Completeness of follow up: 109 women (9.5%) excluded from analyses due to poor compliance with treatment (19 of these due to side effects). Women delivering before 28 weeks or at another hospital were also excluded. | |

| Participants | 1139 nulliparous and multiparous women between 20‐24 weeks' gestation. Excluded: women with ITP, diabetes, or sickle cell disease. |

|

| Interventions | Exp: chlorothiazide 50 mg daily. Control: placebo. Treatment continued until delivery (average 17 weeks). | |

| Outcomes | Woman: pre‐eclampsia (BP > 140 or rise by > 30 mm Hg or dBP > 90 or rise by > 15 mm Hg, with or without proteinuria, or oedema after 24 weeks); hypertension; weight gain, eclampsia; severe pre‐eclampsia; use of additional thiazide diuretic; side effects; biochemical outcomes. Baby: perinatal mortality (stillbirth and neonatal death); birthweight (average). |

|

| Notes | Compliance: participants with poor compliance excluded from study. No further information. Diet: advice given regarding salt intake (3 g to 5 g) and calories (1800 kcal). Race: 93% women non‐white. Single centre. |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | Not reported by researchers. |

| Blinding? All outcomes | Low risk | Stated as double blind. |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | Low risk | Some women delivered at another hospital and so were excluded from the analysis. |

| Free of selective reporting? | High risk | Participants with poor compliance (9.5%) or who delivered before 28 weeks were excluded from the analysis. Poor compliance was reported as due to side effects. |

Sibai 1984.

| Methods | Randomisation: participants "randomly assigned" to one of two groups. No further information. Allocation concealment: not reported. Blinding: none. Completeness of follow up: complete. | |

| Participants | 20 women in first trimester of pregnancy, with long‐term mild to moderate chronic hypertension (dBP 90‐110), who were receiving thiazide diuretics prior to pregnancy. All women were on diuretic therapy at trial entry. | |

| Interventions | Exp: women advised to continue thiazide diuretic throughout pregnancy. Control: women advised to stop diuretic therapy immediately. |

|

| Outcomes | Woman: superimposed pre‐eclampsia (not defined); caesarean section; use of additional antihypertensive drug; maternal weight gain (mean); mean arterial BP; plasma volume; placental weight; biochemical outcomes. Baby: gestational age (mean); birthweight (mean); IUGR; SGA; prematurity (< 37 weeks); perinatal death; Apgar score; postmaturity. |

|

| Notes | Compliance: not reported. Diet: advised restricted salt intake (2 g) and to avoid addition of salt to diet. Single centre. |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | No reported in the trial paper. |

| Blinding? All outcomes | High risk | |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | Low risk | Follow up was complete for all women. |

| Free of selective reporting? | Low risk | |

Weseley 1962.

| Methods | Randomisation: participants "assigned randomly" to two groups. No further information. Allocation concealment: not reported. Blinding: double blind. Completeness of follow up: complete. | |

| Participants | 267 women in second or third trimester, with weight gain 5 pounds or more in 2 weeks or showing increasing oedema of extremities. Excluded: women with hypertension or proteinuria or those who received prenatal care in a different hospital. |

|

| Interventions | Exp: 2 groups, both received chlorothiazide 500 mg x 2 tablets daily. Control: 2 groups, both received placebo. |

|

| Outcomes | Woman: pre‐eclampsia (sBP > 140 or rise by > 30 mm Hg or dBP > 90 or rise by > 15 mm Hg, with or without proteinuria, or oedema after 24 weeks); severe pre‐eclampsia (not defined). Baby: perinatal mortality. |

|

| Notes | Compliance: not reported. Diet: salt restricted. No other information. Single centre. |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | Unclear. |

| Blinding? All outcomes | Low risk | |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | High risk | Follow up was complete. |

| Free of selective reporting? | Low risk | |

BP: blood pressure dBP: diastolic blood pressure Exp: experimental ITP: idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura IUGR: intrauterine growth restriction sBP: systolic blood pressure SGA: small‐for‐gestational age

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Arias 1979 | Intervention was antihypertensive drugs plus diuretics. Methods: "allocated randomly". No further information. Participants: 58 women with mild hypertension prior to 20 weeks' gestation. Interventions: antihypertensive medication (methyldopa or hydralazine, or both) plus hydrochlorothiazide versus no treatment. Outcomes: premature labour, premature rupture of membranes, progressive hypertension, pre‐eclampsia, caesarean section, perinatal death, SGA, birthweight, fetal distress, Apgar scores, neonatal morbidity. |

| Bambas 1971 | Intervention was a comparison of drug combinations for the treatment of "gestosis". Methods: No evidence of any randomisation. No information on allocation methods used. Particiapants: 80 women with "gestosis" ‐ hypertension and oedema in late pregnancy. Interventions: Each group was given a combination of drugs in a single tablet one of which was a diuretic. The combination was the alpha blocker dihydroergocristine, reserpine and clopamide. Dietry advice and salt restriction was also used. Outcomes: Control of blood pressure by categorisation of the level of diastolic pressure, birthweight and Apgar scores. |

| Blake 1991 | Intervention was antihypertensive drugs mainly, but some participants received diuretics in addition. Methods: consecutively numbered sealed envelopes. Participants: 36 women at less than 38 weeks' gestation with non‐proteinuric hypertension. Interventions: antihypertensive drug (atenolol or methyldopa) or, if blood pressure was not controlled, atenolol plus methyldopa with or without bedrofluazide, versus standard hospital practice. Outcomes: changes in blood pressure, proteinuria, perinatal deaths, birthweight, gestational age at delivery, Apgar score. |

| Campbell 1975 | Quasi‐randomised study. Methods: first participant identified allocated to treatment based on case note number, the remaining were then allocated by rotation to the three groups. Participants: 153 women with weight gain more than 570 g per week between 20‐30 weeks' gestation. Interventions: three groups. Cyclopenthiazide versus low carbohydrate diet versus control. Outcomes: pre‐eclampsia, maternal weight change, small‐for‐gestational‐age babies, biochemical and physiological outcomes. |

| Christianson 1976 | Not a randomised trial. Methods: observational study. Participants: 4035 pregnant women over an 8 year period. Interventions: diuretics versus no diuretic. Outcomes: pregnancy outcome, birthweight, gestation at delivery, perinatal mortality. |

| Cuadros 1964 | Quasi‐randomised study. Methods: participants assigned to one of two groups on a rotational basis. Numbers not balanced: difference of 25%. Participants: 1771 women at least 30 weeks' gestation. Intervention: bendroflumethiazide versus placebo. Outcomes: maternal weight gain, pre‐eclampsia, side effects, perinatal death, premature labour, postmaturity, hydramnios, congenital anomalies, biochemical outcomes. |

| Finnerty 1966 | Quasi‐randomised study. Not intention‐to‐treat analysis. It was not possible to restore participants to the correct groups. Methods: participants divided alternately into two groups. Participants in the treatment arm who did not take medicines (201 women) were transferred to control group. Participants: 3083 women 17 years age or under with normal early pregnancy. Interventions: chlorothiazide or chlorthalidone versus no thiazides. Outcomes: toxaemia, perinatal deaths, prematurity. |

| Gray 1968 | Not a randomised trial. Methods: review article. |

| Hayashi 1963 | Not a randomised study. Methods: observational study. Participants: cases were pregnant women with fluid retention, pre‐eclampsia, or hypertensive disease with or without superimposed toxaemia. Controls were women with other obstetric problems. Interventions: 8 groups comparing the effects of hydrodiuril, reserpine, or various diets, alone or in combination with each other. Outcomes: changes in blood pressure and weight, proteinuria, urine output, biochemical outcomes. |

| Hester 1987 | Trial stopped early due to adverse effects. No data available as data were destroyed. Methods: no information available. Participants: women at 32 weeks' gestation. Interventions: furosemide versus placebo. Outcomes: pre‐eclampsia. |

| Hudson 1961 | Quasi‐randomised study. Both groups received diuretics (cross‐over trial). Methods: participants divided alternately into two groups in order of admission. Cross‐over trial. Participants: 10 women less that 38 weeks' gestation with oedema with or without other signs of pre‐eclampsia. Intervention: chlorothiazide first then hydrochlorothiazide for three days each versus hydrochlorothiazide first then chlorothiazide for three days each. Outcomes: maternal weight changes, progression of pre‐eclampsia, stillbirth, biochemical outcomes. |

| Leather 1968 | Participants included women with established pre‐eclampsia prior to trial entry (42%). Methods: "allocated at random" to two groups. No further information. Participants: 100 women after 20 weeks' gestation with pre‐existent or new hypertension with (42%) or without proteinuria. Interventions: bendrofluazide plus methyldopa versus standard care. Outcomes: changes in blood pressure, proteinuria, length of gestation, birthweight, perinatal mortality, Apgar score, biochemical outcomes. |

| Lindheimer 1974 | Not a randomised trial. Methods: editorial. |

| MacGillivray 1980 | Not a randomised trial. Methods: observational study. Participants: pregnant women with normal blood pressure, non‐proteinuric hypertension, and pre‐eclampsia. Interventions: clopamide, spironolactone, thiazide or control. Outcomes: maternal weight gain, pre‐eclampsia, birthweight, biochemical outcomes. |

| Mackay 1969a | Both groups received diuretics (cross‐over trial). Participants included women with established pre‐eclampsia prior to trial entry. Methods: "randomly assigned" to two groups. No further information. Cross‐over trial. Participants: 24 women with hypertension, excessive weight gain or pre‐eclampsia. Interventions: methyl‐sulphamoyl benzamide for 1 week followed by placebo for 1 week and then methylchlothiazide in week 3 and placebo in week 4. Second group received medications in reverse order. Outcomes: maternal weight change, blood pressure, urine volume, adverse effects, biochemical outcomes. |

| Mackay 1969b | Both groups received diuretics (cross‐over trial). Participants included women with established pre‐eclampsia prior to trial entry. No clinical outcomes reported. Methods: 'randomly assigned' to two groups. No further information. Participants: 22 women at least 3 weeks prior to full term, hospitalised for hypertension or pre‐eclampsia. Interventions: spironolactone on days 2‐5, Aldactone‐A plus methylchlothiazide on days 9‐12, then methylchlothiazide alone on days 16‐19. Participants in second group received the medication in reverse order. Outcomes: urinary volume, biochemical outcomes. |

| Menzies 1964 | Quasi‐randomised study. Participants included some women with established pre‐eclampsia at trial entry. Methods: participants divided into two groups based on whether an odd or even number was obtained after adding the last digit of case‐sheet number to last digit of participant's age. Participants: 105 women after 24 weeks' gestation with hypertension, ankle oedema or weight gain at least 4 pounds in 2 weeks. 8 women also had albuminuria. Interventions: chlorothiazide versus phenobarbitone, low salt diet and rest at home. Outcomes: admission to hospital for pre‐eclampsia, eclampsia, maternal mortality, perinatal mortality, weight changes, anaemia, adverse effects. |

| Pannullo 1962 | Unclear if randomised trial. Both groups received diuretic therapy in different doses. Methods: two groups. Methods not stated. Participants: 200 women with oedema, toxaemia, or symptoms of mild pre‐eclampsia. Interventions: methyclothiazide 2.5 mg versus 5 mg daily for 7 days. Outcomes: changes in maternal weight, oedema, and blood pressure, side effects. |

| Prema 1982 | Quasi‐randomised study. Physiological study. Likely that participants included women with established pre‐eclampsia at trial entry. Methods: cases divided alternately into two groups. Participants: 179 women in the third trimester with pregnancy oedema or PIH (not defined but likely pre‐eclampsia). Intervention: furosemide for 3 days versus no diuretic. All women had bed rest and women with PIH also received sedatives. Outcomes: changes in body weight, oedema, urine output, blood pressure, and biochemical outcomes. |

| Riva 1978 | Not a randomised trial. Physiological study. Methods: observational study. Participants: 12 gestotic women. No controls. Interventions: furosemide for a maximum of 5 days. Outcomes: plasma levels of furosemide, rate of diuresis. |

| Sandoval 1967 | Not certain if study is a randomised trial. Physiological study. No data for clinical outcomes reported. Methods: two groups of participants with comparable degree of toxaemia. No further information. Participants: women with toxaemia of pregnancy. Numbers not stated. Interventions: furosemide versus chlorothiazide, sedatives, and potassium for 48 hours. Outcomes: glomerular filtration rate. |

| Schnieden 1955 | Quasi‐randomised study. Methods: participants divided alternately into two groups in order of admission. Participants: 50 women at more than 20 weeks' gestation with weight gain more than 6 pounds in one month. Interventions: four arm study. Acetazolamide plus either a low or moderately low sodium diet versus placebo plus either a low or moderately low sodium diet. Outcomes: development of dBP > 90 mm Hg, albuminuria or oedema, maternal weight change, urine output, biochemical outcomes. |

| Spellacy 1975 | No clinical outcomes reported (physiological study). Methods: "randomly assigned" to one of three groups. No further information. Participants: 75 women between 30‐40 weeks' gestation with early mild signs of impending toxaemia. Interventions: Diuril versus Dilantin versus no drug for one week between two glucose tolerance tests. Outcomes: blood glucose and plasma insulin. |

| Tatum 1961 | Quasi‐randomised study. Methods: participants assigned to two groups on a rotational basis. Participants: women at 28 or more weeks' gestation. Total numbers in each group unclear. Interventions: hydrochlorothiazide versus placebo. Outcomes: changes in maternal weight, blood pressure, oedema, proteinuria, side effects, perinatal deaths, prematurity, biochemical outcomes. |

| Tervila 1971 | Quasi‐randomised study. Not intention‐to‐treat analysis. Methods: participants divided alternately into two groups. Participants who did not take tablets were excluded from study. Participants: 245 primigravidae women at 16 weeks' gestation Interventions: chlorthalidone versus placebo. Outcomes: changes in maternal weight, oedema, blood pressure, proteinuria, side effects, perinatal deaths, birthweight, Apgar score, biochemical and haematological outcomes. |

| Urdapilleta 1967 | Abstract of a study examining the effects of ethacrynic acid in the treatment of "toxaemia". Methods: Not a randomised trial. Participants: Women with established "toxaemia"; numbers not stated. Interventions: Ethacrynic acid plus dietary calorie and salt restriction. Outcomes: Sodium output and serum electrolytes. |

| Walker 1966 | Data cannot be analysed as presented. Data presented as outcomes per cycle of treatment. Some participants had more than one cycle so were counted more than once for outcomes. Some participants were allocated to a different intervention if another treatment cycle was needed. Methods: 'divided at random' into 3 groups. No further information. One or two weeks of treatment regarded as 'one trial'. Same participants re‐entered into trial if symptoms recurred after initial improvement. Some of these patients were re‐assigned to a different intervention. Participants: 85 women in the third trimester with weight gain 5 pounds in previous week or >/= 8 pounds in previous 2 weeks or moderate to severe dependent oedema or weekly weight gain >/= 3 pounds and significant dependent oedema. Interventions: methylchlothiazide versus methylchlothiazide plus low salt diet versus placebo plus low salt diet. Treatment regimen was stopped if satisfactory reduction in weight or oedema. Outcomes: changes in maternal weight and blood pressure, side effects. |

| Zuspan 1960 | Not certain if the study is a randomised trial. 32% of women excluded from analysis due to loss to follow up. Methods: three groups. Methods not stated. Participants: 490 pregnant women. Interventions: hydrochlorothiazide versus dihydrotrichlorothiazide versus placebo. Outcomes: maternal weight loss, adverse effects, urine output, biochemical outcomes. |

BP: blood pressure dBP: diastolic blood pressure PIH: pregnancy‐induced hypertension sBP: systolic blood pressure SGA: small‐for‐gestational age

Characteristics of studies awaiting assessment [ordered by study ID]

Landesman 1965.

| Methods | Two centre trial: Caracas, Venezuela and New York, USA. The indications are that this is a trial but no information is given on randomisation or concealment. The study was testing the ability of Chlorthalidone to prevent the development of pre‐eclampsia. |

| Participants | Two groups of pregnant women between 28 and 32 weeks' gestation. |

| Interventions | 1370 were given Chlorthalidone and 1336 placebo. |

| Outcomes | The outcomes were the incidence of "toxaemia", number of cases of mild pre‐eclampsia, severe pre‐eclampsia, eclampsia, super‐imposed pre‐eclampsia and the number of infant deaths. |

| Notes | The results show no statistically significant differences in the rates of toxaemia (pre‐eclampsia). If the study were a randomised trial then the results could be added to the meta‐analysis but presently further information is required. |

Contributions of authors

David Churchill, Shireen Meher and Catharine Rhodes wrote the original review, with advice from Gareth Beevers. In this update, David Churchill and Catharine Rhodes assessed the new studies and Gareth Beevers and Shireen Meher advised on the revised manuscript. David Churchill is the guarantor of the review.

Sources of support

Internal sources

The University of Liverpool, UK.

External sources

Health Technology Assessment, UK.

Declarations of interest

None known.

New search for studies and content updated (no change to conclusions)

References

References to studies included in this review

Fallis 1964 {published data only}

- Fallis NE, Plauche WC, Mosey LM, Langford HG. Thiazide vs placebo in prophylaxis of toxemia of pregnancy in primigravid patients. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 1964;88:502‐4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Flowers 1962 {published data only}

- Crosland DM, Flowers CE. Chlorothiazide and its relationship to neonatal jaundice. Obstetrics & Gynecology 1963;22:500‐4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flowers CE, Grizzle JE, Easterling WE, Bonner OB. Chlorthiazide as a prophylaxis against toxemia of pregnancy. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 1962;84:919‐29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kraus 1966 {published data only}

- Kraus GW, Marchese JR, Yen SSC. Prophylactic use of hydrochlorothiazide in pregnancy. JAMA 1966;198:128‐32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Sibai 1984 {published data only}

- Sibai BM, Grossman RA, Grossman HG. Effects of diuretics on plasma volume in pregnancies with long‐term hypertension. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 1984;150:831‐5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Weseley 1962 {published data only}

- Weseley AC, Douglas GW. Continuous use of chlorothiazide for prevention of toxemia of pregnancy. Obstetrics & Gynecology 1962;19:355‐8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to studies excluded from this review

Arias 1979 {published data only}

- Arias F, Zamora J. Antihypertensive treatment and pregnancy outcome in patients with mild chronic hypertension. Obstetrics & Gynecology 1979;53:489‐94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Bambas 1971 {published data only}

- Bambas W. Ambulatory treatment of late gestosis with Briserin [Zur ambulanten Behandlung der Spatgestose mit Briserin.]. Therapie der Gegenwart 1971;110:525‐36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Blake 1991 {published data only}

- Blake S, Macdonald D. The prevention of the maternal manifestations of pre‐eclampsia by intensive antihypertensive treatment. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 1991;98:244‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Campbell 1975 {published and unpublished data}

- Blumenthal I. Diet and diuretics in pregnancy and subsequent growth of offspring. BMJ 1976;2:733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell DM, MacGillivray I. The effect of a low calorie diet or a thiazide diuretic on the incidence of pre‐eclampsia and on birthweight. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 1975;82:572‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Christianson 1976 {published data only}

- Christianson R, Page EW. Diuretic drugs and pregnancy. Obstetrics & Gynecology 1976;48(6):647‐52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Cuadros 1964 {published data only}

- Cuadros A, Tatum HJ. The prophylactic and therapeutic use of bendroflumethiazide in pregnancy. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 1964;89:891‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Finnerty 1966 {published data only}

- Finnerty FA, Bepko FJ. Lowering the perinatal mortality and the prematurity rate. The value of prophylactic thiazides in juveniles. JAMA 1966;195:429‐32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Gray 1968 {published data only}

- Gray MJ. Use and abuse of thiazides in pregnancy. Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology 1968;11(2):568‐78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hayashi 1963 {published data only}

- Hayashi TT, Phitaksphraiwan P, Willson JR. Effects of diet and diuretic agents in pregnancy toxemias. Obstetrics & Gynecology 1963;22:327‐34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hester 1987 {unpublished data only}

- Hester LL. The effects of a diuretic (furosemide) in preventing pre‐eclampsia. Personal communication 1987.

Hudson 1961 {published data only}

- Hudson CN. A trial of two oral diuretics and bed rest on urinary electrolyte excretion in oedema of pregnancy. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology of the British Commonwealth 1961;63:68‐73. [Google Scholar]

Leather 1968 {published data only}

- Leather HM, Humphrey DM, Baker P, Chadd MA. A controlled trial of hypotensive agents in hypertension in pregnancy. Lancet 1968;2:488‐90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lindheimer 1974 {published data only}

- Lindheimer MD, Katz AI. Sodium and diuretics in pregnancy. Obstetrics & Gynecology 1974;44(3):434‐9. [Google Scholar]

MacGillivray 1980 {published data only}

- MacGillivray I, Campbell DM. The relevance of hypertension and oedema in pregnancy. Clinical and Experimental Hypertension 1980;2(5):897‐914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Mackay 1969a {published data only}

- Mackay EV, Khoo SK. Clinical and laboratory study of a new diuretic agent (Vectren) in pregnancy. A comparison with a diuretic agent in current use (Enduron). Medical Journal of Australia 1969;1:607‐12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Mackay 1969b {published data only}

- Mackay EV, Khoo SK, Adsett G, Zymanska S. A clinical study of the effects of an aldosterone antagonist (Aldactone‐A) and a thiazide diuretic (Enduron) in pregnancy. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 1969;9:188‐95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Menzies 1964 {published data only}

- Menzies DN. Controlled trial of chlorothiazide in treatment of early pre‐eclampsia. BMJ 1964;1:739‐42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Pannullo 1962 {published data only}

- Pannullo JN. Methyclothiazide in pregnancy. Journal of the Medical Society of New Jersey 1962;59:514‐6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Prema 1982 {published data only}

- Prema K, Ramalakshmi BA, Babu S. Diuretic therapy in pregnancy induced hypertension and pregnancy edema. Indian Journal of Medical Research 1982;75:545‐53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Riva 1978 {published data only}

- Riva E, Farina P, Tognoni G, Bottino S, Orrico C, Pardi G. Pharmacokinetics of furosemide in gestosis of pregnancy. European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 1978;14:361‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Sandoval 1967 {published data only}

- Sandoval JB, Perez FR. Study of glomerular filtration in toxemia of pregnancy. Modifications with the use of furosemid (lasix) [abstract]. 5th World Congress of Gynecology and Obstetrics; 1967; Sydney, Australia. 1967:891.

Schnieden 1955 {published data only}

- Schnieden H. Outpatient trial of acetazoleamide in prevention of pre‐eclamptic toxaemia. Lancet 1955;2:1223‐5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Spellacy 1975 {published data only}

- Spellacy WN, Cohn JE, Buhi WC, Birk SA. Effects of diuril and dilantin on blood glucose and insulin levels in late pregnancy. Obstetrics & Gynecology 1975;45:159‐62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Tatum 1961 {published data only}

- Tatum HJ, Waterman EA. The prophylactic and therapeutic use of thiazides in pregnancy. GP 1961;24:101‐5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Tervila 1971 {published data only}

- Tervila L, Vartiainen E. The effects and side effects of diuretics in the prophylaxis of toxaemia of pregnancy. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica 1971;50:351‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Urdapilleta 1967 {published data only}

- Urdapilleta JD, Robles HD, Roman MV, Diaz AP. Ethacrynic acid in the treatment of toxemia of pregnancy [abstract]. 5th World Congress of Gynecology and Obstetrics; 1967; Sydney, Australia. 1967:892.

Walker 1966 {published data only}

- Walker JL. Methylclothiazide in excessive weight gain and edema of pregnancy. Obstetrics & Gynecology 1966;27:247‐51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Zuspan 1960 {published data only}

- Zuspan FP, Bell JD, Barnes AC. Balance‐ward and double‐blind diuretic studies during pregnancy. Obstetrics & Gynecology 1960;16:543‐9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to studies awaiting assessment

Landesman 1965 {published data only}

- Landesman R, Aguero O, Wilson K, Russa R, Campbell W, Penaloza O. The prophylactic use of chlorthalidone, a sulfonamide diuretic in pregnancy. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology of the British Commonwealth 1965;72:1004‐10. [Google Scholar]

Additional references

Collins 1985