Abstract

Accumulation of fibrillar amyloid β-protein (Aβ) in parenchymal plaques and in blood vessels of the brain, the latter condition known as cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA), are hallmark pathologies of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and related disorders. Cerebral amyloid deposits have been reported to accumulate various metals, most notably copper and zinc. Here we show that, in human AD, copper is preferentially accumulated in amyloid-containing brain blood vessels compared to parenchymal amyloid plaques. In light of this observation, we evaluated the effects of reducing copper levels in Tg2576 mice, a transgenic model of AD amyloid pathologies. The copper chelator, tetrathiomolybdate (TTM), was administered to twelve month old Tg2576 mice for a period of five months. Copper chelation treatment significantly reduced both CAA and parenchymal plaque load in Tg2576 mice. Further, copper chelation reduced parenchymal plaque copper content but had no effect on CAA copper levels in this model. These findings indicate that copper is associated with both CAA deposits and parenchymal amyloid plaques in humans, but less in Tg2576 mice. TTM only reduces copper levels in plaques in Tg2576 mice. Reducing copper levels in the brain may beneficially lower amyloid pathologies associated with AD.

Graphical Abstract

Multimodal imaging studies show that Aβ amyloid in brain vessels of Tg2576 mice (green) preferentially binds copper (red) – a pathology that can be reduced with copper chelators.

Introduction

Cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA) is a common cerebral small vessel disease that involves the accumulation of amyloid β-protein (Aβ) primarily in small- and medium-sized arteries and arterioles of the meninges and cerebral cortex as well as along the capillaries of the cerebral microvasculature1–4. CAA has been shown to be present, in varying degrees, in nearly 80% of elderly individuals5, 6. With the involvement of Aβ, it is not surprising that CAA is a very common vascular comorbidity in patients with Alzheimer’s disease (AD)3, 4. Independent of AD, CAA is a significant contributor to vascular-mediated cognitive impairment and dementia (VCID)2, 7. CAA can uniquely contribute to the cognitive decline in VCID and AD in several ways. For example, the accumulation of amyloid in cerebral blood vessels causes degeneration of cerebrovascular smooth muscle cells and microvascular pericytes8–10. Also, CAA promotes the increased expression and activation of certain proteolytic enzymes in cerebral vascular cells11–13. Together, these processes can lead to loss of vessel wall integrity and hemorrhage and/or chronic hypoperfusion and ischemic infarcts2, 14–18. Yet, the reasons why cerebral vascular amyloid develops and its contribution to downstream pathologies and VCID remain unclear.

Copper is an essential metal for normal brain development and function as it is an important co-factor for a number of enzymes and mitochondrial respiration19–21. Altered brain copper homeostasis has been considered to be a factor in the pathogenesis of AD, but little is understood about the specific mechanisms of action22. On one hand, there have been reports of low plasma copper levels in AD23, 24. Alternatively, other studies have reported elevated levels of plasma copper in AD25, 26. In particular, several studies have reported the accumulation of copper ions in amyloid plaque deposits of AD patients and in certain mouse models of parenchymal AD-like plaques27–30. Further, several single nucleotide polymorphisms in the copper transporter ATP7B gene are associated with a significant increase in the risk for the development of AD31–33. These findings suggest that copper accumulation in parenchymal amyloid plaques may be correlated with neurodegeneration and cognitive impairment.

Mechanistically, this hypothesis is supported by in vitro studies that demonstrated that copper binds to Aβ, presumably through three N-terminal histidine residues, resulting in a reduction of Cu2+ to Cu+34. Copper-bound Aβ has been shown to be more prone to aggregation35 and also reacts with oxygen to produce reactive oxygen species that can promote neurodegeneration and thus cause cognitive impairment36. Specifically, copper-binding to Aβ has been shown to result in hydroxyl radical formation and the production of hydrogen peroxide, which activate a pro-inflammatory response in the form of interleukin-1β and tumor necrosis factor-α, which further contributes to neurodegeneration37{Kitazawa, 2016 #1435}.

Collectively, these studies suggest that copper may play an important role in both the formation of amyloid plaques and in subsequent neuronal dysfunction and cognitive impairment. In contrast to previous work examining parenchymal amyloid plaques, comparatively little is known about the accumulation of copper in cerebral vascular amyloid deposits, which are associated with VCID.

Here we report that CAA deposits contain higher copper levels than parenchymal amyloid plaques in human AD brain. We then hypothesized that copper plays a role in promoting and/or stabilizing fibrillar amyloid deposition in CAA. Chronic treatment of Tg2576 mice, a model of AD-like amyloid pathologies, with the copper chelator TTM lowered the amount of both cerebral vascular amyloid and parenchymal plaque amyloid deposition. Further, TTM lowered the levels of copper present only in parenchymal plaques and had no effect on CAA copper levels. However, in Tg2576 mice, the copper level in parenchymal plaques was modestly higher than in CAA deposits, a finding distinct from human CAA. Nevertheless, the present findings show that copper is strongly associated with cerebral vascular amyloid and may play a role in amyloid formation and subsequent CAA pathologies.

Materials and Methods

Human AD brain tissues

Fresh frozen human AD brain tissue specimens containing both parenchymal plaques and cerebral vascular amyloid were obtained from the Neuropathology Core at University of California University of California, Irvine.

Animal experiments

All work with animals was approved by the University of Rhode Island and Stony Brook University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees and were conducted in conformity with the NIH Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Tg2576 mice were obtained from Jackson Laboratories at approximately three months of age and housed in a controlled room (22 ± 2°C) with a 12h reverse light-dark cycle. At twelve months of age cohorts of Tg2576 mice were administered drinking water containing 5% sucrose (control) or 10mg/ml ammonium tetrathiomolymbdate (TTM) (copper chelator) + 5% sucrose for a period of five months. All administrations were prepared fresh and replaced every third day. Weekly water consumption and monthly body weights were determined for each animal in the study.

Brain tissue collection and preparation

Mice were euthanized at the end of the study and perfused with cold-PBS, forebrains were removed and dissected through the mid-sagittal plane. One hemisphere was flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C. For immunohistochemical studies, the other hemisphere was immersion-fixed with 70% ethanol overnight and subjected to increasing sequential dehydration in ethanol, followed by xylene treatment and embedding in paraffin. Sagittal sections were cut through the entire hemisphere at 10 μm thickness using a Leica RM2135 microtome (Leica Microsystems Inc., Bannockburn, IL), placed in a flotation water bath at 40°C, and then mounted on Colorfrost/Plus slides (Fisher Scientific, Houston, TX).

X-ray fluorescence microscopy

For XFM studies, fresh frozen human AD brain tissue (n=3) and Tg2576 mouse brain tissue (n=3 treated with TTM, n=3 untreated) were sectioned at 20 μm and mounted on 4-μm-thick Ultralene film, which was affixed to a 1.5” diameter Delrin ring. The localization of amyloid was determined by staining the tissue sections with thioflavin S. Prior to XFM data collection, the protein density in the vessels was determined using Fourier transform infrared microspectroscopy (FTIRM). Since the vessels can be denser than the surrounding tissue, the protein density was used to normalize the XFM data when quantifying the metal content, thus avoiding an overestimate of the metal content within the vessels. FTIRM spectra were acquired using a Spectrum Spotlight FTIR microscope with 8 cm−1 spectral resolution over the mid-infrared spectral region (4000–800 cm−1). A 20 μm aperture was used with 64 scans per point. The relative protein content at each pixel was determined by integrating the Amide II protein peak from 1490 – 1580 cm−1 with a linear baseline from 1480 – 1800 cm−1. The area under this peak is directly proportional to the amount of protein in the specimen. The relative protein density was calculated as the Amide II area on/off the vessels.

The copper concentration within the vessels and plaques was determined using synchrotron XFM at beamline 13-ID-E at the Advanced Photon Source, Argonne National Laboratory and beamlines 4-BM and 5-ID at the National Synchrotron Light Source II, Brookhaven National Laboratory. The energy of the incident X-ray beam was 10 keV. The X-ray beam was focused to a 1–3 μm spot size using Kirkpatrick-Baez focusing mirrors. X-ray fluorescence was detected by a Si-drift detector oriented at a 90° angle from the incident beam. Energy dispersive spectra were collected at every pixel.

Quantitation of Aβ peptides

Total cerebral levels of Aβ40 and Aβ42 were determined by performing specific ELISAs on mouse forebrain tissue homogenates as described38, 39. In the sandwich ELISAs Aβ40 and Aβ42 were captured using their respective carboxyl-terminal specific antibodies mAb2G3 and mAb21F12 and biotinylated m3D6, specific for human Aβ, was used for detection. Each mouse brain homogenate was measured in triplicate and compared to linear standard curves generated with known concentrations of human Aβ using a Spectramax M2 plate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA).

Immunohistochemical analysis

Antigen retrieval was performed by treating the tissue sections with proteinase K (0.2 mg/ml) for 10 min at 22 °C. Primary rabbit polyclonal antibody to collagen type IV was used to visualize cerebral vessels (1:100; ThermoFisher, Rockford, IL). The primary antibody was detected with Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit secondary antibody (1:1000). Staining for fibrillar amyloid was performed using thioflavin S. Brain tissue sections were imaged and collected using an Olympus BX60 microscope with an attached Olympus Dp72 camera. Images were collected from every tenth section spanning the hemisphere.

Quantitative analysis of amyloid pathologies

Using NIH ImageJ software, the percent area occupied with positive stain was quantified. Percent area coverage of ThS+ parenchymal plaques and ThS+ amyloid on blood vessels in the cortical regions was determined.

Statistical Analysis

XFM, histological and immunochemical data were analyzed by t-test at the 0.05 significance level.

Results

Cerebral vascular amyloid contains elevated copper levels compared with parenchymal amyloid plaques in AD brain

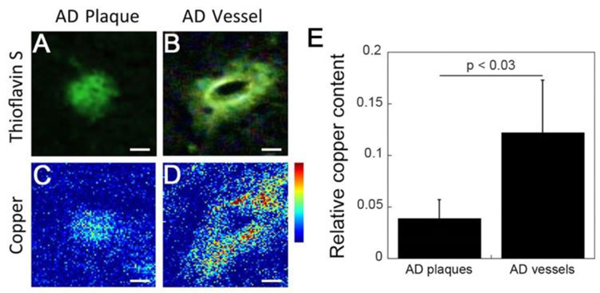

Previous studies have reported that amyloid plaques in human AD brain accumulate metal ions including iron, copper, and zinc 29, 30. Here we sought to determine whether cerebral vascular amyloid deposits similarly accumulate metal ions using the technique of x-ray fluorescence microscopy (XFM). Fig. 1A and 1B show representative thioflavin S stained images of fibrillar parenchymal amyloid plaques and fibrillar cerebral vascular amyloid deposits, respectively. Fig. 1C and 1D show the same deposits imaged for copper using XFM demonstrating the elevated levels of copper in the CAA deposits. Statistically, Fig. 1E shows that the copper content is ~3-fold higher in vascular amyloid deposits when compared to plaques in human AD brain tissue (p < 0.03). A similar trend was observed with the zinc content, which showed that zinc was 2–3 times higher in the CAA deposits compared to the amyloid plaques (data not shown).

Fig. 1.

Higher copper content in cerebral vascular amyloid deposits compared to parenchymal plaque amyloid deposits in the same AD brain tissue. Epifluorescence images of the thioflavin S staining and corresponding copper XFM images of parenchymal (A,C) and cerebral vascular (B,D) amyloid deposits from the same AD brain tissue. Scale bars = 5 μm. (E) Relative copper levels in the vascular amyloid deposits were ~3-fold higher than in parenchymal amyloid plaques. Data shown are mean ± S.D. of n = 5 for each type of amyloid deposit from the same tissues.

Administration of the copper chelator TTM to Tg2576 mice with AD-like amyloid pathologies

To investigate if copper levels impact CAA and amyloid plaque pathology in Tg2576 mice, we administered TTM through their drinking water starting at twelve months of age, a point where both cerebral vascular and parenchymal amyloid pathologies begin to emerge in this model40, 41 Tg2576 mice were administered drinking water containing either 5% sucrose + 10 mg/ml of the copper chelator TTM or 5% sucrose alone for a period of five months. Weekly water intake from each group of animals was not significantly different (control = 214 ± 91 vs TTM = 171 ± 60; p = 0.2). Likewise, both groups of Tg2576 mice started at similar weights (control = 32.2 ± 5.1 vs TTM = 29.7 ± 6.1: p = 0.3) and finished the study at similar weights (control = 39.1 ± 6.6 vs TTM = 33.5 ± 6.2; p = 0.06). Thus, administration of TTM had no adverse effect on the general health of the Tg2576 mice.

Copper chelation with TTM reduces cerebral vascular amyloid and parenchymal plaque load in Tg2576 mice

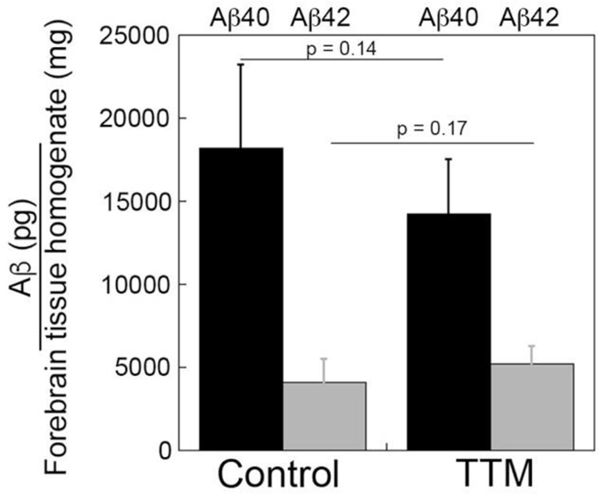

Accumulation and deposition of Aβ peptides in the brain is a key pathological feature of AD that is replicated in Tg2576 transgenic mice 40. Since we observed the presence of copper in cerebral amyloid deposits in human AD brain (Fig. 1), we investigated the effects of copper chelation on Aβ accumulation in Tg2576 mice. ELISA measurements for the total levels of forebrain Aβ40 and Aβ42 peptides revealed no significant difference between control and TTM-treated Tg2576 mice (Fig. 2). Although copper chelation treatment did not significantly affect the total cerebral accumulation of Aβ species we next evaluated the impact on compartmental deposition of amyloid in the brains of the Tg2576 mice.

Fig. 2.

ELISA analysis of cerebral Aβ40 and Aβ42 peptides in control and TTM-treated Tg2576 mice. The total levels of Aβ40 peptides (black bars) and Aβ42 peptides (gray bars) in the forebrains of control and TTM-treated Tg2576 mice were measured by ELISA as described under “Materials and Methods.” The data presented are the means ± S.D. of triplicate measurements of n = 5–6 mice per group.

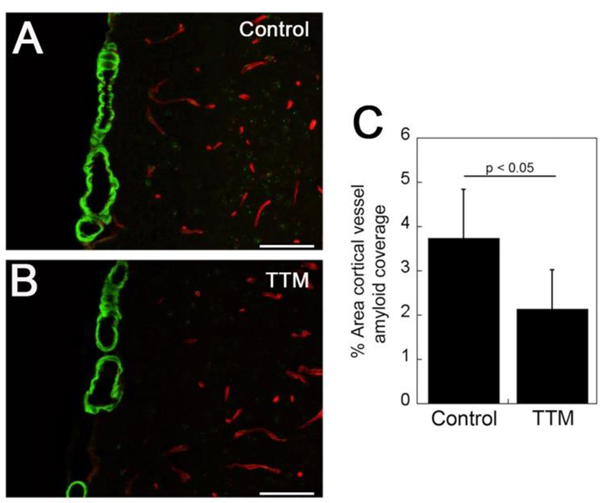

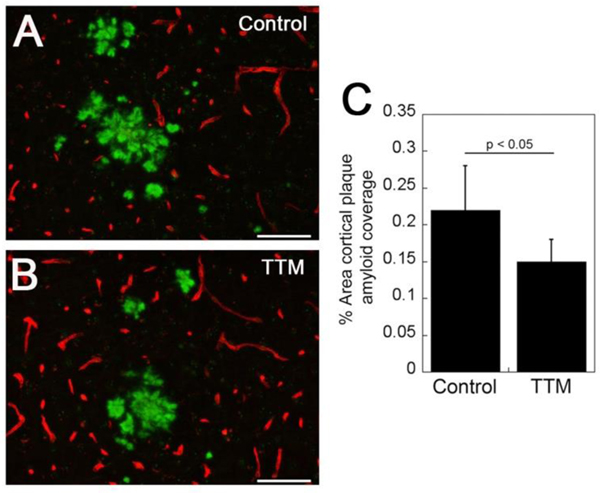

Staining for fibrillar amyloid deposition using thioflavin S revealed the presence of cortical CAA, mainly in the surface meningeal vessels. Morphologically there was no discernible difference between the appearance of CAA in the control and TTM-treated Tg2576 mice (Fig. 3A and 3B, respectively). However, quantifying the amount of cortical CAA revealed a significant reduction (p < 0.05) in the amount of vessel coverage with amyloid in the TTM-treated Tg2576 mice (Fig. 3C). Similarly, staining for fibrillar amyloid showed the presence of parenchymal plaques in both control and TTM-treated Tg2576 mice (Fig. 4A and 4B, respectively). Again, there was no apparent difference in the morphology of the fibrillar amyloid plaques. Yet, similar to the findings with CAA, there was a significant reduction (p < 0.05) in percentage of cortical area occupied by fibrillar amyloid plaques (Fig. 4C). Together, these findings indicate that copper chelation with TTM treatment reduced the amount of both fibrillar CAA and parenchymal plaque amyloid deposition in Tg2576 mice.

Fig. 3.

TTM treatment reduces CAA load in Tg2576 mice. Brain sections from control (A) and TTM-treated (B) Tg2576 mice were stained for fibrillar amyloid using thioflavin-S (green) and immunolabeled for collagen type IV to identify cerebral blood vessels (red). Scale bars = 50 μM. (C) Quantitation of cortical vascular thioflavin-S positive amyloid load in control and TTM-treated Tg2576 mice. Data shown are mean ± S.D. of n = 5 Tg2576 mice per group.

Fig. 4.

TTM treatment reduces cortical amyloid plaque load in Tg2576 mice. Brain sections from control (A) and TTM-treated (B) Tg2576 mice were stained for fibrillar amyloid using thioflavin-S (green) and immunolabeled for collagen type IV to identify cerebral blood vessels (red). Scale bars = 50 μM. (C) Quantitation of cortical thioflavin-S positive amyloid plaque load in control and TTM-treated Tg2576 mice. Data shown are mean ± S.D. of n = 5 Tg2576 mice per group.

Copper chelation with TTM reduces copper content of parenchymal amyloid plaques but not of CAA in Tg2576 mice

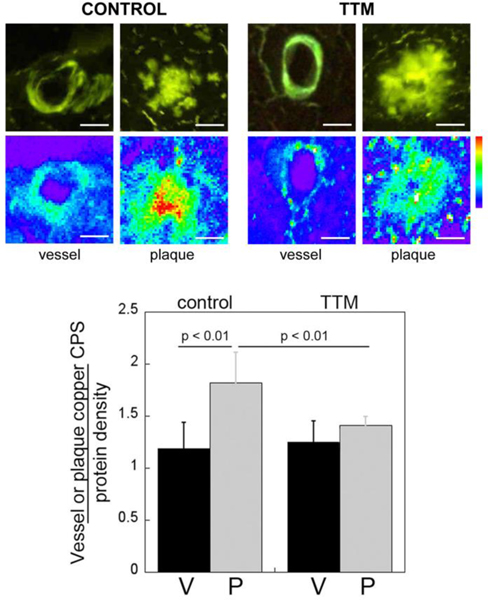

Since copper chelation treatment lowered both CAA and parenchymal plaque load in the Tg2576 mice, we next determined if this treatment also changed the copper content in these distinct cerebral amyloid lesions. We performed XFM on CAA and parenchymal amyloid plaque deposits in control and TTM-treated Tg2576 mice that were identified by staining with thioflavin S (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

TTM treatment reduces cortical amyloid plaque copper levels in Tg2576 mice. Brain sections from control and TTM-treated Tg2576 mice were stained with thioflavin S to identify fibrillar amyloid deposits in cerebral vessels (V) and parenchymal amyloid plaques (P). The relative copper levels in these deposits were determined using XFM and tissue density was normalized using FTIR microspectroscopy. All Cu images are shown on the same intensity scale. Histograms shown are mean ± S.D. of n = 5 Tg2576 mice per group.

Interestingly, we found that the copper content in parenchymal amyloid plaques was significantly higher (p < 0.01) than the cerebral vascular amyloid deposits in Tg2576 mice, which was the opposite of what was observed in human AD brain tissue (Fig. 1). TTM treatment significantly lowered (p < 0.01) the copper content of parenchymal amyloid plaques but had no effect on reducing the copper content of CAA deposits. At the end of TTM treatment, the copper content of vascular and parenchymal amyloid deposits was essentially the same. These findings indicate that although TTM treatment similarly reduces CAA and parenchymal plaque load it only lowers copper content in the parenchymal amyloid plaques in Tg2576 mice.

Discussion

CAA is a common cerebral small vessel disease of the elderly and a prominent comorbidity of AD that promotes and exacerbates VCID, yet our understanding of the condition remains limited. Both CAA and AD are characterized by the accumulation of fibrillar Aβ in the brain vessels and parenchyma, respectively. In human AD, metal ions including iron, copper, and zinc have been shown to co-localize with the parenchymal plaques 29, 30. But while the parenchymal plaques in AD have been studied extensively, little is known about metal-ion accumulation in amyloid-containing brain vessels in AD. Here we examined the cerebral vascular amyloid in human AD and found that the copper content was ~3-fold higher than the parenchymal plaques and >10-fold higher than surrounding brain tissue. This finding supports the hypothesis of an environment for toxic redox chemistry in the vessel walls, leading to pro-inflammatory responses that may play a role in the degeneration of cerebrovascular cells, which can lead to loss of vessel wall integrity and subsequent CAA pathologies37, 42.

In contrast to human AD, the PSAPP and 5XFAD mouse models of AD show little or no metal accumulation in the parenchymal plaques 27, 28. Results presented here for the Tg2576 mouse model show similar results. Given the similarly low copper levels in parenchymal plaques from all mouse models, and the observations that mouse models also show much less neuronal loss than humans, it has been suggested that copper binding to Aβ plaques generates redox-initiated toxic species that contribute to neurodegeneration.

Unlike previous work that focused only on parenchymal plaques, this is the first study to examine both parenchymal plaques and vascular amyloid in the same animals. Results show that, for the Tg2576 mouse model, the copper-binding in both plaques and vessels is considerably lower than what has been observed in humans and, surprisingly, parenchymal plaques have a slightly higher copper content than the vascular amyloid. Studies on vascular and parenchymal amyloid have shown that the primary Aβ species in the vasculature is Aβ40, whereas the parenchymal plaques contain primarily Aβ42 3, 4. Further, recent studies have shown that in vascular amyloid the fibrils possess an anti-parallel configuration that is distinct from the parallel fibril orientation observed in parenchymal plaques. Thus, we suggest that peptide length and/or structural differences between vascular and parenchymal Aβ fibrils may affect copper-binding.

Given the potential role of copper in CAA pathogenesis, we assessed whether copper chelation treatment would alleviate the amyloid burden in the brain vasculature and parenchyma of Tg2576 mice. We found that copper chelation treatment had no significant effect on the levels of cerebral Aβ40 or Aβ42 (Fig. 2). It has been shown that copper binds to the amyloid precursor protein (APP) 43 and causes a reduction of Cu(II) to Cu(I) 44. Further binding of copper to APP can also modulate APP processing by γ-secretase and Aβ peptide production 45, 46. However, our finding of no significant effect of copper chelation on A peptide levels in Tg2576 mouse brain suggests that this treatment is not appreciably impacting APP processing and Aβ production.

Copper also binds to the Aβ peptide directly 47–51 where three histidine residues control the redox activity of the copper ion 52. Moreover, when bound to Aβ fibrils, copper redox chemistry can lead to the formation of hydrogen peroxide and generation of reactive oxygen species 37 and treatment with TTM has been shown to invoke anti-inflammatory responses53. In contrast to the ELISA measures of total cerebral Aβ40 and Aβ42 levels we show that the fibrillar vascular Aβ deposits and plaque burdens were both significantly reduced with copper chelation in the Tg2576 mice. This could suggest that copper plays a role in the formation and/or stabilization of the Aβ fibrils and, when copper is lowered, this results in reduced amyloid burden.

Even though the amyloid burden is lowered in both the vessels and plaques, the level of copper-binding in the amyloid that still forms is similarly low with or without the copper chelator. The only exception is the parenchymal plaques, which have a slightly higher level of copper-binding that is lowered by TTM. It is possible that the higher burden of parenchymal plaque amyloid compared to vascular amyloid in the Tg2576 mice provides more of a reservoir to bind copper in the brain. Alternatively, since parenchymal plaques are primarily composed of Aβ42 3, 4, this could suggest that, in Tg2576 mice, copper may preferentially bind Aβ42 fibrils compared to Aβ40 fibrils and, when copper is lowered, results in decreased copper binding in the parenchymal plaques. On the other hand, the inability of TTM to lower copper content in vascular amyloid may reflect stronger binding to these particular amyloid fibrils that were recently shown to possess a distinct anti-parallel structure 41.

In summary, we find that copper binding to CAA vessels is significantly higher than parenchymal plaques in human AD brain. Toxic redox chemistry associated with this higher level of copper in the vessels may contribute to degeneration of cerebral vascular cells and subsequent loss of vessel wall integrity. In contrast, the Tg2576 mouse model of AD showed much lower levels of copper binding to amyloid in both the brain vessels and parenchymal plaques. Moreover, treatment with TTM had little effect on the copper content in the vessels or plaques in this model. Interestingly, however, TTM was shown to significantly reduce the amount of fibrillar amyloid in both the CAA vessels and parenchymal plaques. These findings suggest that chelation of copper in the Tg2576 mouse model may affect amyloid fibril formation and/or stabilization. However, in the CAA deposits and parenchymal plaques that still form, the copper content is considerably lower than the human condition, in agreement with earlier studies from other mouse models of AD. Together, this supports the hypothesis that redox chemistry associated with copper binding to Aβ results in the production of toxic species that contribute to cellular degeneration and these pathological processes are not robust in mouse models of AD.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIH grant NS094201 to WEVN and LMM. Antibody reagents for the Aβ ELISA were generously provided by Lilly Research Laboratories, Indianapolis, IN. Portions of this work were performed at GeoSoilEnviroCARS (The University of Chicago, Sector 13), Advanced Photon Source (APS), Argonne National Laboratory. GeoSoilEnviroCARS is supported by the National Science Foundation - Earth Sciences (EAR - 1634415) and Department of Energy- GeoSciences (DE-FG02–94ER14466). This research used resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science User Facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC02–06CH11357. This research also used beamlines 5-ID (SRX) and 4-BM (XFM) of the National Synchrotron Light Source II, a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science User Facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Brookhaven National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-SC0012704.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts to declare.

References

- [1].Banerjee G, Carare R, Cordonnier C, Greenberg SM, Schneider JA, Smith EE, Buchem MV, Grond JV, Verbeek MM, Werring DJ: The increasing impact of cerebral amyloid angiopathy: essential new insights for clinical practice. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2017, 88:982–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Auriel E, Greenberg SM: The pathophysiology and clinical presentation of cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Curr Atheroscler Rep 2012, 14:343–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Attems J, Jellinger K, Thal DR, Van Nostrand W: Review: sporadic cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 2011, 37:75–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Rensink AA, de Waal RM, Kremer B, Verbeek MM: Pathogenesis of cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Brain Res Brain Res Rev 2003, 43:207–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Boyle PA, Yu L, Nag S, Leurgans S, Wilson RS, Bennett DA, Schneider JA: Cerebral amyloid angiopathy and cognitive outcomes in community-based older persons. Neurology 2015, 85:1930–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Arvanitakis Z, Leurgans SE, Wang Z, Wilson RS, Bennett DA, Schneider JA: Cerebral amyloid angiopathy pathology and cognitive domains in older persons. Ann Neurol 2011, 69:320–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Greenberg SM, Gurol ME, Rosand J, Smith EE: Amyloid angiopathy-related vascular cognitive impairment. Stroke 2004, 35:2616–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Kawai M, Kalaria RN, Cras P, Siedlak SL, Velasco ME, Shelton ER, Chan HW, Greenberg BD, Perry G: Degeneration of vascular muscle cells in cerebral amyloid angiopathy of Alzheimer disease. Brain Res 1993, 623:142–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Davis-Salinas J, Saporito-Irwin SM, Cotman CW, Van Nostrand WE: Amyloid beta-protein induces its own production in cultured degenerating cerebrovascular smooth muscle cells. J Neurochem 1995, 65:931–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Verbeek MM, de Waal RM, Schipper JJ, Van Nostrand WE: Rapid degeneration of cultured human brain pericytes by amyloid beta protein. J Neurochem 1997, 68:1135–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Van Nostrand WE, Porter M: Plasmin cleavage of the amyloid beta-protein: alteration of secondary structure and stimulation of tissue plasminogen activator activity. Biochemistry 1999, 38:11570–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Davis J, Wagner MR, Zhang W, Xu F, Van Nostrand WE: Amyloid beta-protein stimulates the expression of urokinase-type plasminogen activator (uPA) and its receptor (uPAR) in human cerebrovascular smooth muscle cells. J Biol Chem 2003, 278:19054–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Jung SS, Zhang W, Van Nostrand WE: Pathogenic A beta induces the expression and activation of matrix metalloproteinase-2 in human cerebrovascular smooth muscle cells. J Neurochem 2003, 85:1208–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Okamoto Y, Yamamoto T, Kalaria RN, Senzaki H, Maki T, Hase Y, Kitamura A, Washida K, Yamada M, Ito H, Tomimoto H, Takahashi R, Ihara M: Cerebral hypoperfusion accelerates cerebral amyloid angiopathy and promotes cortical microinfarcts. Acta Neuropathol 2012, 123:381–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Samarasekera N, Smith C, Al-Shahi Salman R: The association between cerebral amyloid angiopathy and intracerebral haemorrhage: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2012, 83:275–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Chung YA O JH, Kim JY, Kim KJ, Ahn KJ: Hypoperfusion and ischemia in cerebral amyloid angiopathy documented by 99mTc-ECD brain perfusion SPECT. J Nucl Med 2009, 50:1969–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Kimberly WT, Gilson A, Rost NS, Rosand J, Viswanathan A, Smith EE, Greenberg SM: Silent ischemic infarcts are associated with hemorrhage burden in cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Neurology 2009, 72:1230–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Thanvi B, Robinson T: Sporadic cerebral amyloid angiopathy--an important cause of cerebral haemorrhage in older people. Age Ageing 2006, 35:565–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Skjorringe T, Moller LB, Moos T: Impairment of interrelated iron- and copper homeostatic mechanisms in brain contributes to the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative disorders. Front Pharmacol 2012, 3:169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Lutsenko S, Bhattacharjee A, Hubbard AL: Copper handling machinery of the brain. Metallomics 2010, 2:596–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Gaggelli E, Kozlowski H, Valensin D, Valensin G: Copper homeostasis and neurodegenerative disorders (Alzheimer’s, prion, and Parkinson’s diseases and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis). Chem Rev 2006, 106:1995–2044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Quinn JF, Crane S, Harris C, Wadsworth TL: Copper in Alzheimer’s disease: too much or too little? Expert Rev Neurother 2009, 9:631–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Brewer GJ, Kanzer SH, Zimmerman EA, Celmins DF, Heckman SM, Dick R: Copper and ceruloplasmin abnormalities in Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen 2010, 25:490–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Vural H, Demirin H, Kara Y, Eren I, Delibas N: Alterations of plasma magnesium, copper, zinc, iron and selenium concentrations and some related erythrocyte antioxidant enzyme activities in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. J Trace Elem Med Biol 2010, 24:169–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Arnal N, Cristalli DO, de Alaniz MJ, Marra CA: Clinical utility of copper, ceruloplasmin, and metallothionein plasma determinations in human neurodegenerative patients and their first-degree relatives. Brain Res 2010, 1319:118–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Squitti R, Barbati G, Rossi L, Ventriglia M, Dal Forno G, Cesaretti S, Moffa F, Caridi I, Cassetta E, Pasqualetti P, Calabrese L, Lupoi D, Rossini PM: Excess of nonceruloplasmin serum copper in AD correlates with MMSE, CSF [beta]-amyloid, and h-tau. Neurology 2006, 67:76–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Bourassa MW, Leskovjan AC, Tappero RV, Farquhar ER, Colton CA, Van Nostrand WE, Miller LM: Elevated copper in the amyloid plaques and iron in the cortex are observed in mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease that exhibit neurodegeneration. Biomed Spectrosc Imaging 2013, 2:129–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Leskovjan AC, Lanzirotti A, Miller LM: Amyloid plaques in PSAPP mice bind less metal than plaques in human Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroimage 2009, 47:1215–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Miller LM, Wang Q, Telivala TP, Smith RJ, Lanzirotti A, Miklossy J: Synchrotron-based infrared and X-ray imaging shows focalized accumulation of Cu and Zn co-localized with beta-amyloid deposits in Alzheimer’s disease. J Struct Biol 2006, 155:30–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Lovell MA, Robertson JD, Teesdale WJ, Campbell JL, Markesbery WR: Copper, iron and zinc in Alzheimer’s disease senile plaques. J Neurol Sci 1998, 158:47–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Squitti R, Ventriglia M, Gennarelli M, Colabufo NA, El Idrissi IG, Bucossi S, Mariani S, Rongioletti M, Zanetti O, Congiu C, Rossini PM, Bonvicini C: Non-Ceruloplasmin Copper Distincts Subtypes in Alzheimer’s Disease: a Genetic Study of ATP7B Frequency. Mol Neurobiol 2017, 54:671–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Squitti R, Siotto M, Arciello M, Rossi L: Non-ceruloplasmin bound copper and ATP7B gene variants in Alzheimer’s disease. Metallomics 2016, 8:863–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Squitti R, Polimanti R, Siotto M, Bucossi S, Ventriglia M, Mariani S, Vernieri F, Scrascia F, Trotta L, Rossini PM: ATP7B variants as modulators of copper dyshomeostasis in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuromolecular Med 2013, 15:515–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Streltsov VA, Titmuss SJ, Epa VC, Barnham KJ, Masters CL, Varghese JN: The structure of the amyloid-beta peptide high-affinity copper II binding site in Alzheimer disease. Biophys J 2008, 95:3447–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Huang X, Atwood CS, Moir RD, Hartshorn MA, Tanzi RE, Bush AI: Trace metal contamination initiates the apparent auto-aggregation, amyloidosis, and oligomerization of Alzheimer’s Abeta peptides. J Biol Inorg Chem 2004, 9:954–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Eskici G, Axelsen PH: Copper and oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. Biochemistry 2012, 51:6289–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Mayes J, Tinker-Mill C, Kolosov O, Zhang H, Tabner BJ, Allsop D: beta-amyloid fibrils in Alzheimer disease are not inert when bound to copper ions but can degrade hydrogen peroxide and generate reactive oxygen species. J Biol Chem 2014, 289:12052–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Johnson-Wood K, Lee M, Motter R, Hu K, Gordon G, Barbour R, Khan K, Gordon M, Tan H, Games D, Lieberburg I, Schenk D, Seubert P, McConlogue L: Amyloid precursor protein processing and A beta42 deposition in a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1997, 94:1550–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].DeMattos RB, O’Dell MA, Parsadanian M, Taylor JW, Harmony JA, Bales KR, Paul SM, Aronow BJ, Holtzman DM: Clusterin promotes amyloid plaque formation and is critical for neuritic toxicity in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2002, 99:10843–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Hsiao K, Chapman P, Nilsen S, Eckman C, Harigaya Y, Younkin S, Yang F, Cole G: Correlative memory deficits, Abeta elevation, and amyloid plaques in transgenic mice. Science 1996, 274:99–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Xu F, Fu Z, Dass S, Kotarba AE, Davis J, Smith SO, Van Nostrand WE: Cerebral vascular amyloid seeds drive amyloid beta-protein fibril assembly with a distinct anti-parallel structure. Nat Commun 2016, 7:13527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Kitazawa M, Hsu HW, Medeiros R: Copper Exposure Perturbs Brain Inflammatory Responses and Impairs Clearance of Amyloid-Beta. Toxicol Sci 2016, 152:194–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Hesse L, Beher D, Masters CL, Multhaup G: The beta A4 amyloid precursor protein binding to copper. FEBS Lett 1994, 349:109–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Multhaup G, Schlicksupp A, Hesse L, Beher D, Ruppert T, Masters CL, Beyreuther K: The amyloid precursor protein of Alzheimer’s disease in the reduction of copper(II) to copper(I). Science 1996, 271:1406–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Noda Y, Asada M, Kubota M, Maesako M, Watanabe K, Uemura M, Kihara T, Shimohama S, Takahashi R, Kinoshita A, Uemura K: Copper enhances APP dimerization and promotes Abeta production. Neurosci Lett 2013, 547:10–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Gerber H, Wu F, Dimitrov M, Garcia Osuna GM, Fraering PC: Zinc and Copper Differentially Modulate Amyloid Precursor Protein Processing by gamma-Secretase and Amyloid-beta Peptide Production. J Biol Chem 2017, 292:3751–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Kowalik-Jankowska T, Ruta-Dolejsz M, Wisniewska K, Lankiewicz L: Coordination of copper(II) ions by the 11–20 and 11–28 fragments of human and mouse beta-amyloid peptide. J Inorg Biochem 2002, 92:1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Barnham KJ, McKinstry WJ, Multhaup G, Galatis D, Morton CJ, Curtain CC, Williamson NA, White AR, Hinds MG, Norton RS, Beyreuther K, Masters CL, Parker MW, Cappai R: Structure of the Alzheimer’s disease amyloid precursor protein copper binding domain. A regulator of neuronal copper homeostasis. J Biol Chem 2003, 278:17401–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Syme CD, Nadal RC, Rigby SE, Viles JH: Copper binding to the amyloid-beta (Abeta) peptide associated with Alzheimer’s disease: folding, coordination geometry, pH dependence, stoichiometry, and affinity of Abeta-(1–28): insights from a range of complementary spectroscopic techniques. J Biol Chem 2004, 279:18169–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Tougu V, Karafin A, Palumaa P: Binding of zinc(II) and copper(II) to the full-length Alzheimer’s amyloid-beta peptide. J Neurochem 2008, 104:1249–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Hatcher LQ, Hong L, Bush WD, Carducci T, Simon JD: Quantification of the binding constant of copper(II) to the amyloid-beta peptide. J Phys Chem B 2008, 112:8160–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Nakamura M, Shishido N, Nunomura A, Smith MA, Perry G, Hayashi Y, Nakayama K, Hayashi T: Three histidine residues of amyloid-beta peptide control the redox activity of copper and iron. Biochemistry 2007, 46:12737–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Wang Z, Zhang YH, Guo C, Gao HL, Zhong ML, Huang TT, Liu NN, Guo RF, Lan T, Zhang W, Wang ZY, Zhao P: Tetrathiomolybdate Treatment Leads to the Suppression of Inflammatory Responses through the TRAF6/NFkappaB Pathway in LPS-Stimulated BV-2 Microglia. Front Aging Neurosci 2018, 10:9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]