ABSTRACT

Background

The health benefits related to intake of whole grain foods are well established. Consumption of whole grains in the US population is low, and whole grain content can vary greatly depending upon the specific products that are purchased.

Objectives

To examine the proportion of products purchased by US households containing whole grain and refined grain ingredients using time-specific food composition data, and examine whether purchases differ between income, race or ethnicity, and household make-up.

Methods

Nationally representative Nielsen Homescan 2018 data were used. Each barcoded product captured in Nielsen Homescan 2018 was linked with ingredient information using commercial nutrition databases in a time-relevant manner. Packaged food products containing whole grain ingredients, refined grain ingredients, neither, or both were identified. The percentage of packaged food products containing whole grain and refined grain ingredients purchased by US households was determined overall, by demographic subgroup, and by food category.

Results

The proportion of packaged food purchases containing refined grain ingredients was significantly higher than whole grain ingredients (30.9% compared with 7.9%; P < 0.0001). Lower income households and households with children purchased a significantly higher proportion of products containing refined grain ingredients, with no nutritionally meaningful racial or ethnic differences observed. Concerningly, across all demographic subgroups >90% of bread purchases contained refined grain ingredients, and the 5 categories with the largest proportion of whole grain ingredients contributed to <20% of overall US household packaged food purchases.

Conclusions

US households are purchasing a significantly higher proportion of packaged food products containing refined grain ingredients than whole grain ingredients. Future policy changes are needed to provide incentives and information (e.g., front-of-pack labels) to aid in encouraging manufacturers to increase whole grain product offerings while decreasing refined grain offerings, and to encourage consumers to substitute away from refined grain products toward whole grain products.

Keywords: whole grains, refined grains, packaged foods, diet quality, food purchases

Introduction

The health benefits related to intake of whole grain foods are well established, including decreased risk of weight gain, cardiovascular diseases, type 2 diabetes, and some forms of cancer (1–3). Whole grain foods are defined as those that contain all the essential parts and intrinsic nutrients of the entire grain seed in their original proportions (4). Accordingly, 100% of the original kernel (i.e., the bran, germ, and endosperm) must be present to qualify as a whole grain. In the United States, a whole grain food product must contain ≥8 g whole grain per 30 g product to carry a whole grain claim (4). Total dietary fiber is associated with whole grains and their health benefits. Current US dietary guidelines recommend an increased intake of both dietary fiber and whole grain foods. However, overall consumption of whole grains in the US population is low (5), with research showing that US adults and children who consume less whole grain have lower diet quality, lower fiber intake, and less optimal nutrient intakes (5, 6). The most recent estimates indicate that, for most US children and adults, whole grain as a proportion of total grain intake continues to be consumed at levels well below recommendations (6), with only ∼15% of grain intake deriving from whole grain sources and the majority of grain intake deriving from refined grains (7). The Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2020–2025 recommend that ≥50% of total grain intake derive from whole grains, with ≤50% deriving from refined grains (8).

To date, the majority of research into whole grain intake in the US population is based on dietary surveys (e.g., NHANES) and is linked with nutrient information from the USDA food composition tables containing ∼7500 foods. Although useful, these tables are somewhat limited in scope and not updated annually and, thus, do not take into account the >400,000 different packaged foods purchased by US consumers annually that are rapidly changing due to product introduction and reformulation (9, 10). Hence, most studies to date that have examined whole grain intake in the US population have been limited by out-of-date product-specific food composition data. In fact, evidence shows that the biggest contributors to whole grain consumption in the US population are yeast bread/rolls and ready-to-eat cereals (11), and the whole grain and refined grain content of these types of foods can differ widely depending on the specific brand or product being purchased. In addition, the FDA has an approved list of added fiber ingredients that manufacturers can use to contribute toward the total dietary fiber declared in the Nutrition Facts Panel (12), and hence it is important to understand the types of products consumers are buying and to have an understanding of how many products being purchased by US consumers contain added fiber ingredients (as opposed to intrinsic fiber).

The objective of this study was to examine the proportion of products purchased in the US population containing whole grain and refined grain ingredients using time-specific food composition data. This study offers a unique opportunity to examine packaged food sources of whole grain purchases in the US population and compare how purchases differed among income groups, racial or ethnic groups, and by household composition (e.g., presence of children) in 2018. Food group sources of whole grains and refined grains were also examined.

Methods

Nielsen Homescan panel, 2018

The Nielsen Homescan panel is an ongoing nationally representative longitudinal survey in which participating households record all Universal Product Code (UPC) purchases on a daily basis using a handheld scanner (13, 14). In 2018, 61,367 households reported purchasing foods and beverages over a 1-y period with >448,000 different UPCs. Households also report sociodemographic and household information including gender, income, detailed age composition, education, and race (white, black, other) and ethnicity (Hispanic, non-Hispanic) of the head of the household. We combined the available race and ethnicity measures to identify when heads of the households were non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, or other non-Hispanic. Households included in Homescan are sampled and weighted to be nationally representative. The Homescan data set is used frequently by researchers to examine food consumption and purchasing patterns (15, 16). By using secondary deidentified Homescan data, we were exempted from institutional review board concerns.

Linkage of UPC food products with Nutrition Facts Panel data and ingredient information

Each UPC captured in Nielsen Homescan 2018 was matched with Nutrition Facts Panel data and ingredient information (when available) using commercial nutrition databases (i.e., Gladson, Label Insight, Product Launch Analytics, USDA National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference, and Mintel Global New Products Database) in a time-relevant manner. These commercial databases contain national brands and private label items at the barcode level, and data are updated regularly as new products enter the market. Further details regarding matching these commercial datasets have been published previously (9). Homescan does not include bulk items without barcodes, thus foods and beverages without a barcode or a Nutrition Facts Panel were excluded (e.g., unpackaged fresh fruits and vegetables, fresh meats, loose bread and bakery products without a barcode).

Food categories examined

Packaged products in the Homescan data are not categorized in a nutritionally relevant manner. Thus, the Global Food Research Program team of registered dietitians reviewed the Homescan purchases to create a nutritionally meaningful food grouping system. All major food categories in this categorization system were included in the current study, but beverages were excluded because they do not contribute to grain intake. Detailed food group information is presented in Table 1. Of note is that grain-based flours were included in the “Ingredients” category, and sandwiches and pizzas were included in the “Mixed dishes” category.

TABLE 1.

Category definitions

| Category | Included products |

|---|---|

| Baby formula and food | Infant and toddler formula and foods/snacks |

| Bread | Bread rolls, loaves, flatbread, bagels, English muffins, biscuits |

| Cereal | Ready-to-eat and hot breakfast cereals |

| Dairy foods | Yogurt, cream, cheese |

| Fruits and vegetables | Fruit, vegetables, legumes |

| Grain-based desserts and snacks (GBDS) | Cookies, brownies, cakes, pies, donuts, pastries, muffins, pancakes, waffles, crepes, sweet rolls |

| Grains | Pasta, rice, quinoa, polenta |

| Ingredients | Salt, spices, seasonings, sugar and sweeteners, fats and oils, flour and breading |

| Mixed dishes | Soup, salads, sandwiches, pizza, ready meals |

| Other desserts and sweets | Ice cream and frozen dairy desserts, puddings, cheesecake, sorbet/popsicles, jell-o, jam/jelly, pie filling, dessert syrups/toppings, frosting, confectionery |

| Protein foods | Meat, poultry, seafood, eggs, plant-based alternatives |

| Sauces, condiments, dressings, dips | Salad dressings, marinades, mayonnaise, pasta/pizza sauces, table sauces, condiments, dips, salsa, gravy, simmer sauces |

| Snacks | Nuts, nut butters, bars, crackers/crispbread, chips, popcorn, snack mixes, fruit snacks, pretzels, rice cakes, extruded snacks |

Identification of whole grain, refined grain, and fiber-containing ingredients

Most US government regulations regarding “whole grain” refer to calling a product whole grain, not individual ingredients. However, various references exist that provide guidance as to what would constitute a whole grain ingredient in the United States. As such, for the purposes of this project, the standard definition of whole grains as “those which consist of the entire grain, including all of the bran, germ, and endosperm” was used as a starting point to determine whether ingredients were considered whole grain. The US Wholegrains Council provides a list of general food types that are considered whole grain, which we included in our definition of whole grain ingredients. In addition, US government guidance documents, including FDA Draft Guidance on Whole Grain Label Statements (2006), FDA Standards of Identity for Whole Grain Products, and the USDA requirements for Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC)–eligible foods (7 CFR Part 246.10), were used to identify additional ingredients that would be considered whole grain. Ultimately, if it was unclear if an ingredient was whole or refined grain, it was assumed to be refined. For example, unless corn was listed as “whole grain corn” it was not considered a whole grain ingredient. Manual examination of individual product ingredient lists was performed when there was any concern about whether or not a specific ingredient should or should not be considered whole grain. Products without ingredient lists were categorized as “unknown grain status.” Supplemental Table 1 lists the search terms used to define both whole grain and refined grain ingredients.

Added fiber ingredients were identified using search terms defined by the FDA: beta-glucan soluble fiber, inulin, psyllium husk, cellulose, guar gum, pectin, locust bean gum, and hydroxypropyl methylcellulose.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc.) using Nielsen projection weights. The weight of foods purchased overall, by demographic subgroup and by food group, was determined overall and for: 1) refined grains; 2) whole grains; 3) both refined and whole grains; 4) neither refined nor whole grains; or 5) unknown grain status. These were further examined by splitting the percentage purchased into products with and without added fiber ingredients. The carbohydrate-to-fiber ratio was also determined by dividing the purchases of total carbohydrate (grams) by fiber purchases (grams). A carbohydrate:fiber ratio <10:1 is proposed by the AHA as a proxy for whole grain content because it is approximately equal to the carbohydrate-to-fiber content of whole wheat flour and aims to identify healthier carbohydrate-rich foods (17, 18). Differences among population subgroups were examined through t tests using household projection weights provided by Nielsen. Bonferroni multiple comparison adjustment was applied and a P value < 0.0001 was considered significant.

Results

Overall results

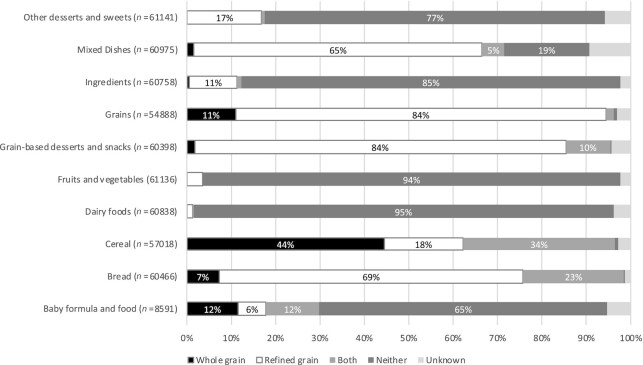

Overall, 7.9% of packaged food purchases contained whole grain ingredients, 30.9% contained refined grain ingredients, and 61.6% did not contain any grain-based ingredients (Supplemental Table 2). The proportion of purchases containing refined grain ingredients was significantly higher than whole grain ingredients (P < 0.0001). Considering purchases that contained only refined grain ingredients, 71% contained added fiber. There were similar observations for products with only whole grain ingredients, with 74% containing added fiber. The “Cereal” category had the largest proportion of purchases containing whole grain ingredients (79%; Figure 1). However, the “Cereal” category contributed to only 3% of overall packaged food purchases (Supplemental Table 3). Grain-based desserts and snacks represented 6% of overall household packaged food purchases and included the highest proportion of products containing refined grain ingredients (94%)—84% with refined grains only, and 10% with both refined and whole grain ingredients. Interestingly, only 30% of bread purchases contained whole grain ingredients, with 91% containing refined grain ingredients. The only category with a higher proportion of purchases containing whole grain ingredients compared with refined grain ingredients was “Baby formula and food” (12% whole grain only and 6% refined grain only). Importantly, the 5 categories with the largest proportion of whole grain ingredients contributed to only 19% of overall packaged food purchases. By contrast, the 5 categories with the largest proportion of refined grain ingredients contributed to 34% of packaged food purchases (Supplemental Table 3). The carbohydrate:fiber ratio was high overall (16.7), with no significant differences observed between demographic subgroups.

FIGURE 1.

Proportion of whole grain and refined grain products purchased by US households in 2018, in selected food categories. University of North Carolina (UNC) calculation based in part on data reported by NielsenIQ through its Homescan Services for all food categories including beverages for 2018 across the US market (14). Authors’ calculations based in part on data reported by NielsenIQ through its Homescan Services for all food categories including beverages for 2018 across the US market (14).

All demographic subgroups purchased a significantly higher proportion of products with only refined grain ingredients compared with only whole grain ingredients (P < 0.0001 for all; Supplemental Table 2). Overall, there were small but significant differences between subgroups observed.

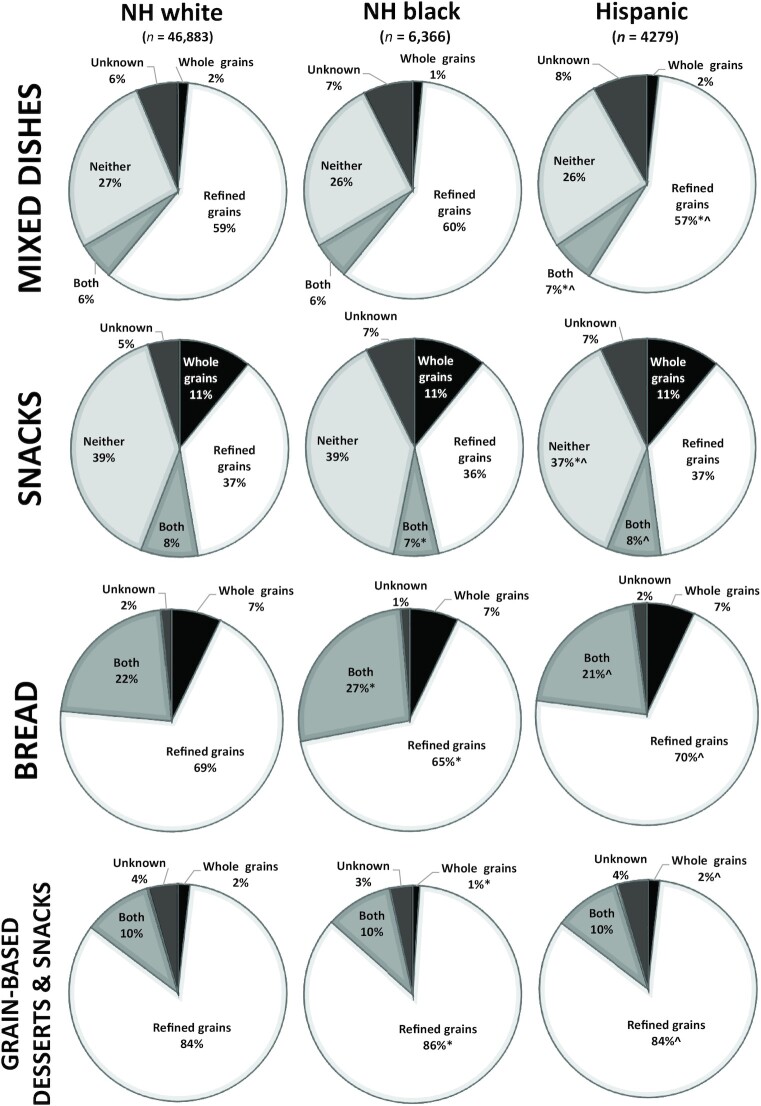

Racial or ethnic differences

Hispanic households purchased a significantly higher proportion of products with whole grains compared with non-Hispanic black households (8.2% compared with 7.5%; P < 0.0001), and non-Hispanic black households purchased a significantly lower proportion of products with refined grains compared with non-Hispanic white households (30.0% compared with 31.1%; P < 0.0001). Non-Hispanic black households purchased a significantly higher proportion of “Cereal” products containing only refined grain ingredients (29%) compared with non-Hispanic white (16%) and Hispanic (17%) households (Supplemental Figure 1). Each racial or ethnic group purchased the same proportion of “Bread” and “Snacks” products containing only whole grain ingredients (7% and 11%, respectively) (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Proportion of purchases by racial or ethnic group and grain status in selected food categories. University of North Carolina calculation based in part on data reported by NielsenIQ through its Homescan Services for all food categories including beverages for 2018 across the US market (14). Authors’ calculations based in part on data reported by NielsenIQ through its Homescan Services for all food categories including beverages for 2018 across the US market (14). *Different from non-Hispanic white (P < 0.0001); ^different from non-Hispanic black (P < 0.0001). NH, non-Hispanic.

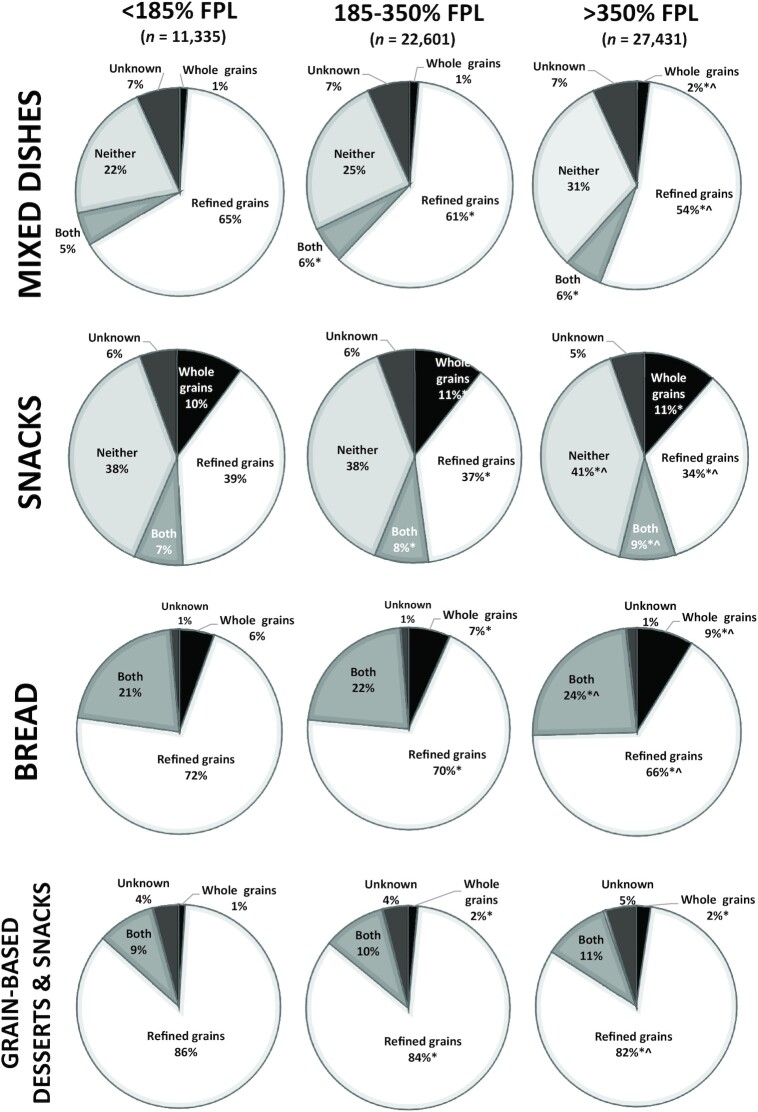

Household income differences

Overall, the highest income group purchased a significantly lower proportion of products with refined grain ingredients (28.6%) compared with the lowest income group (33.4%) and middle income group (32.0%) (P < 0.0001 for all; Supplemental Table 2). The highest income group purchased a significantly higher proportion of “Cereal” products containing only whole grain ingredients (48%) compared with the lowest income (40%) and middle income (43%) groups, and a lower proportion of purchases containing only refined grain ingredients (15% compared to 21% and 18%, respectively; Supplemental Figure 2). The highest income group also purchased a significantly lower proportion of “Bread” products containing only refined grain ingredients (66%) compared with the lowest income group (72%) and middle income group (70%) (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Proportion of purchases by income level and grain status in selected food categories. University of North Carolina (UNC) calculation based in part on data reported by NielsenIQ through its Homescan Services for all food categories including beverages for 2018 across the US market (14). Authors’ calculations based in part on data reported by NielsenIQ through its Homescan Services for all food categories including beverages for 2018 across the US market (14). *Different from <185% FPL (P < 0.0001); ^different from 185–350% FPL (P < 0.0001). FPL, Federal Poverty Level.

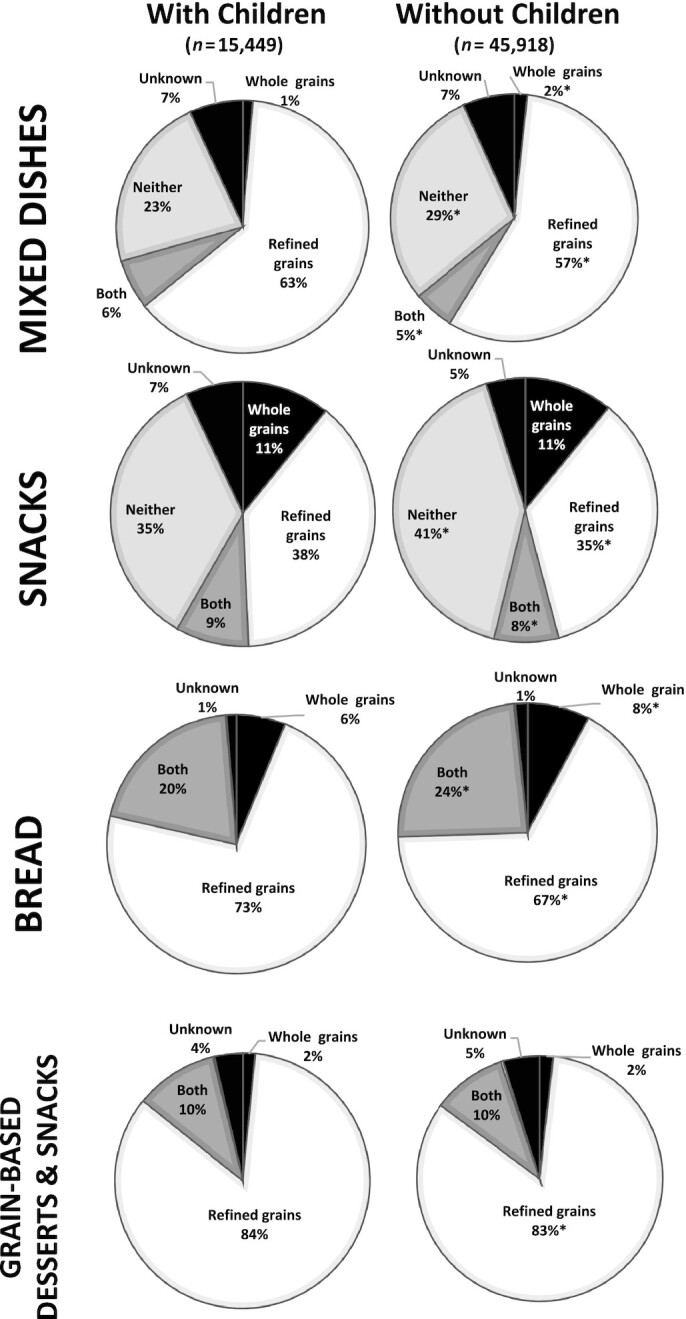

Household type differences

Households with children purchased a significantly higher proportion of products containing only refined grain ingredients compared with households without children (28.3% compared with 25.2%; P < 0.0001). Households with children purchased a significantly lower proportion of “Cereal” products with only whole grain ingredients (39%) compared with households without children (47%), but a higher proportion of “Cereal” products containing both whole grain and refined grain ingredients (40% compared with 31%; Supplemental Figure 3). Households with children also purchased a higher proportion of “Bread” products with only refined grain ingredients (73%) compared with households without children (67%; Figure 4).

FIGURE 4.

Proportion of purchases by household type and grain status in selected food categories. University of North Carolina (UNC) calculation based in part on data reported by NielsenIQ through its Homescan Services for all food categories including beverages for 2018 across the US market (14). Authors’ calculations based in part on data reported by NielsenIQ through its Homescan Services for all food categories including beverages for 2018 across the US market (14). *Different from households with children (P < 0.0001).

Discussion

In this study using nationally representative data on US households’ packaged food purchases in 2018, although 34% of packaged food purchases contained grain-based ingredients, the vast majority of foods contained only refined grain ingredients (77%), 9% contained only whole grain ingredients, and the remaining 14% contained a combination of refined and whole grain ingredients. Importantly, the 5 categories with the largest proportion of whole grain ingredients contributed to only 19% of overall food purchases. By contrast, one-third (34%) of purchases consisted of the 5 food categories with the largest proportion of refined grain ingredients. The “Cereal” category had the highest proportion of whole grain ingredients, with “Grain-based desserts and snacks” the highest proportion of refined grain ingredients. Concerningly, 69% of “Bread” products contained only refined grain ingredients, with 23% containing both refined grain and whole grain ingredients, and 7% containing only whole grain ingredients. With research suggesting that bread products are a major source of dietary fiber in the US population (19), it is therefore likely that fiber intake from bread products derives primarily from added fiber sources rather than whole grain sources (20). Some research has suggested that texture of whole grain bread products can be a reason consumers lean toward refined grain products, and so it could be that innovative refined grain products with added fiber can help support an increased intake in dietary fiber in the US population (21). However, there is still debate as to whether added fiber ingredients achieve the same health benefits as intrinsic fiber found in whole grains (22). Although packaged food products with added fiber can help increase fiber intake (21), it is still likely in the best interest of population health to encourage the consumption of whole grain products over refined grain products even if they contain added fiber, because the intact plant cell wall from intrinsic fiber also contains micronutrients and phytochemicals and can confer benefits beyond those conferred by fiber isolates (22).

US households with children purchased a slightly higher proportion of products with refined grains both overall and in key food categories such as “Bread,” “Cereals,” and “Snacks” compared with households without children. Households with children were also found to report a higher proportion of refined grain purchases containing added fiber. This supports previous research showing that whole grain intakes and fiber intakes in US children are below recommendations (1, 20), whereas refined grain consumption is excessively high (23). An important consideration when examining results for households with children is that children can consume ≤2 daily meals at school (24). Research from the School Health Policies and Practices Study indicates that almost all schools offer whole grains at breakfast and lunch, and that it is more common in high schools than elementary schools (24). Although not purchase related, school meal nutrition policies can support improvements in dietary intake by exposing children to foods with more whole grains. Although the current school lunch and breakfast program rules specify that half of the weekly grains in the school lunch and breakfast menu be whole grain–rich (25), these policies could potentially go even further and require that a larger share of products contain only whole grain ingredients (e.g., whole grain breads and cereals) and restrict refined grain ingredients in an effort to provide foods that contribute to US children and adolescents meeting the dietary recommendation for whole grain intake. For example, a new study has shown that although the whole grain component of the Healthy Eating Index (HEI) appears to have increased over time for children, not much improvement in the refined grain component of the HEI was seen over the same time period (23), supporting the notion that more could be done in school settings to help reduce refined grain intake and further increase whole grain intake in children.

The current study found that the highest income group purchased the largest proportion of whole grains and lowest proportion of refined grains compared with lower income groups, supporting previous research showing that higher income households generally have higher overall diet quality (26) and that high-income groups are more likely to meet whole grain intake recommendations (27). The HEI 2015 applied to NHANES 2015–2016 supports this finding, with the highest income group having a higher HEI component score for whole grains and refined grains (3.2/10 and 7/10, respectively) compared with the lowest income group (2.6/10 and 5.7/10, respectively) (26). Similarly, the Food Acquisition and Purchase Survey, conducted by the USDA, also provides insight into whole grain and refined grain purchases by households. Results from this survey reflect the present findings, that higher income households generally have healthier eating scores, and have a higher proportion of purchases containing refined grain compared with whole grain ingredients (28). These findings highlight the need to identify programs or policies to support US households to purchase foods containing whole grains and substitute away from refined grains. Low-income households and individuals might need assistance to be able to access whole grain options more than ever given the economic impacts from the COVID-19 pandemic.

In 2009, the USDA's WIC implemented revisions to the composition and quantities of WIC-provided foods. New whole grain products such as whole-wheat bread and allowable substitutes were added to encourage increased intake of whole grains and fiber in WIC participants. As a result of the WIC revisions, purchases of 100% whole grain bread tripled from 8% to 24% of all bread purchases (29), showing the positive effect that policy changes can have on whole grain purchases.

In the future, it could be worthwhile investigating whether additional changes such as requiring all bread purchases contain whole grains or including incentives could help ensure further increases in whole grain intake in lower income households. It has been well documented that WIC food package revisions are associated with healthier food purchases in WIC-participating households compared with low-income nonparticipating households, and thus future package revisions might further encourage lower income families to make healthier food purchases (30). Including whole grain items to be eligible under WIC's Cash Value Benefit, which is currently limited to fruits and vegetables with no added sugar, added sodium, or added fat, should be considered. Similar approaches could be taken with the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), which serves almost 1 in 7 Americans. Research has indicated that <5% of SNAP participants meet whole grain intake recommendations (31), but that SNAP participants would be in favor of policies that facilitate purchases of healthful foods and limit purchases of unhealthful foods (32). SNAP incentive programs and pilots that to date are limited to fruits and vegetables could be expanded to include whole grain items, such as whole grain breads and cereals, to help improve financial access for and increase whole grain purchases in lower income households.

Interestingly, major differences between racial or ethnic groups were not observed in overall household purchases of whole grains. Whole grain intake research using NHANES has previously shown that non-Hispanic whites consume more whole grains than non-Hispanic blacks and Hispanics, and have also been shown to have higher dietary quality overall (33). The HEI 2015 results also showed similar results among racial or ethnic groups (34); however, <1% of all racial or ethnic groups have been shown to meet whole grain intake recommendations overall (27) and this, coupled with the current study showing a low overall proportion of purchases containing whole grains, could be why significant differences between racial or ethnic groups were not observed. However, when delving into food group sources of whole grains some interesting racial or ethnic differences were found, with non-Hispanic black households purchasing a higher proportion of “Cereal” and “Grain-based desserts and snacks” products with refined grain ingredients and a lower proportion with whole grain ingredients compared with non-Hispanic white households.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine purchases and food sources of whole grain and refined grain ingredients in US households using the most currently available household purchase data. However, this research is not without limitations. One challenge in using Homescan data is that estimates of household purchases might not be comparable with per capita intake from dietary intake surveys (e.g., NHANES). For example, in a given household all purchases of products containing whole grain ingredients could be consumed by a single member of the household, rather than being consumed by all household members. Homescan also does not capture whole grain purchases from fast-food chains and other restaurants, which could have resulted in an underestimate of purchases in the present study, although few fast-food chains provide whole grain products. In addition, only packaged foods were included in the current study. Fresh fruits and vegetables, loose bread and bakery products, and other nonpackaged foods are not included.

In conclusion, US households are purchasing a significantly higher proportion of packaged food products containing refined grain ingredients than whole grain ingredients. Although racial or ethnic differences were minimal, significant differences based on household composition and income level were relevant. Concerningly, >90% of bread products purchased contained refined grain ingredients. Future policy changes such as requiring schools to increase the minimum share of bread products containing whole grain ingredients, added incentives for participants in WIC and SNAP to purchase products with whole grain ingredients, and potentially including a front-of-pack label for products containing refined grain ingredients (35, 36) could all help support increases in whole grain purchases and concurrent decreases in refined grain purchases by US households.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the UNC Global Food Research Program team of registered dietitians and Research Associates (Bridget Hollingsworth, Jessica Ostrowski, and Julie Wandell) for their support in identifying whole grain and refined grain ingredients.

The authors’ responsibilities were as follows—EKD, SWN, and BP: designed and conducted the research; DRM: analyzed data; EKD: drafted the paper; EKD, DRM, SWN, and BP: had joint primary responsibility for final content; and all authors: read and approved the final manuscript.

Notes

Funding for this work comes primarily from Arnold Ventures with additional support from the Carolina Population Center NIH grant P2C HD050924.

Supplemental Tables 1–3 and Supplemental Figures 1–3 are available from the “Supplementary data” link in the online posting of the article and from the same link in the online table of contents at https://academic.oup.com/jn/.

Author disclosures: The authors report no conflicts of interest.

The conclusions drawn from the data are those of The University of North Carolina (UNC) and do not reflect the views of NielsenIQ. NielsenIQ is not responsible for and had no role in, and was not involved in, analyzing and preparing the results reported herein.

Abbreviations used: HEI, Healthy Eating Index; SNAP, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program; UNC, University of North Carolina; UPC, Universal Product Code; WIC, Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children.

Contributor Information

Elizabeth K Dunford, Department of Nutrition, Gillings Global School of Public Health, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC, USA; Food Policy Division, The George Institute for Global Health, University of New South Wales, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia.

Donna R Miles, Department of Nutrition, Gillings Global School of Public Health, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC, USA; Carolina Population Center, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC, USA.

Barry Popkin, Department of Nutrition, Gillings Global School of Public Health, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC, USA; Carolina Population Center, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC, USA.

Shu Wen Ng, Department of Nutrition, Gillings Global School of Public Health, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC, USA; Carolina Population Center, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC, USA.

Data Availability

Data described in the manuscript, code book, and analytic code will not be made available because of the proprietary nature of the household purchase data (we have a data use agreement for licensing the use of the NielsenIQ data that prohibits us from sharing the data).

References

- 1. Reicks M, Jonnalagadda S, Albertson AM, Joshi N. Total dietary fiber intakes in the US population are related to whole grain consumption: results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2009 to 2010. Nutr Res. 2014;34(3):226–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Aune D, Keum N, Giovannucci E, Fadnes LT, Boffetta P, Greenwood DC, Tonstad S, Vatten LJ, Riboli E, Norat T. Whole grain consumption and risk of cardiovascular disease, cancer, and all cause and cause specific mortality: systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies. BMJ. 2016;353:i2716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hu Y, Ding M, Sampson L, Willett WC, Manson JE, Wang M, Rosner B, Hu FB, Sun Q. Intake of whole grain foods and risk of type 2 diabetes: results from three prospective cohort studies. BMJ. 2020;370:m2206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wholegrains Council . What's a whole grain? A refined grain?[Internet]. 2021; [cited 2021 Jul 15]. Available from: https://wholegrainscouncil.org/whole-grains-101/whats-whole-grain-refined-grain.

- 5. O'Neil CE, Nicklas TA, Zanovec M, Cho S. Whole-grain consumption is associated with diet quality and nutrient intake in adults: the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1999–2004. J Am Diet Assoc. 2010;110(10):1461–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Albertson AM, Reicks M, Joshi N, Gugger CK. Whole grain consumption trends and associations with body weight measures in the United States: results from the cross sectional National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2001–2012. Nutr J. 2015;15(1):8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ahluwalia N, Herrick KA, Terry AL, Hughes JP. Contribution of whole grains to total grains intake among adults aged 20 and over: United States, 2013–2016. NCHS Data Brief, no. 341. Hyattsville (MD): National Center for Health Statistics; 2019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. US Department of Agriculture and US Department of Health and Human Services . Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2020–2025. [Internet]. 2021; [cited 2021 Sep 16]. Available from: https://www.dietaryguidelines.gov/sites/default/files/2020-12/Dietary_Guidelines_for_Americans_2020-2025.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Poti JM, Yoon E, Hollingsworth B, Ostrowski J, Wandell J, Miles DR, Popkin BM. Development of a food composition database to monitor changes in packaged foods and beverages. J Food Compos Anal. 2017;64(1):18–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Slining MM, Yoon EF, Davis J, Hollingsworth B, Miles D, Ng SW. An approach to monitor food and nutrition from “Factory to fork”. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2015;115(1):40–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Meynier A, Chanson-Rollé A, Riou E. Main factors influencing whole grain consumption in children and adults—a narrative review. Nutrients. 2020;12(8):2217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gordon D. FDA approval of added fiber as dietary fiber. Curr Dev Nutr. 2020;4(Suppl 2):632. [Google Scholar]

- 13. The Nielsen Company . Retail measurement. [Internet]. 2021[cited September 2021]. Available from: http://www.nielsen.com/us/en/nielsen-solutions/nielsen-measurement/nielsen-retail-measurement.html.

- 14. NielsenIQ . Homescan. [Internet]. 2021; [cited September 2021]. Available from: https://nielseniq.com/global/en/solutions/homescan.

- 15. Ng SW, Slining MM, Popkin BM. The healthy weight commitment foundation pledge: calories sold from U.S. consumer packaged goods, 2007–2012. Am J Prev Med. 2014;47(4):508–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Dunford EK, Miles DR, Ng SW, Popkin B. Types and amounts of nonnutritive sweeteners purchased by US households: a comparison of 2002 and 2018 Nielsen Homescan purchases. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2020;120(10):1662–71.e10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Liu J, Rehm CD, Shi P, McKeown NM, Mozaffarian D, Micha R. A comparison of different practical indices for assessing carbohydrate quality among carbohydrate-rich processed products in the US. PLoS One. 2020;15(5):e0231572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mozaffarian RS, Lee RM, Kennedy MA, Ludwig DS, Mozaffarian D, Gortmaker SL. Identifying whole grain foods: a comparison of different approaches for selecting more healthful whole grain products. Public Health Nutr. 2013;16(12):2255–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. McGill CR, Birkett A, Fulgonii III VL. Healthy eating index-2010 and food groups consumed by US adults who meet or exceed fiber intake recommendations NHANES 2001-2010. Food Nutr Res. 2016;60(1):29977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kranz S, Dodd KW, Juan WY, Johnson LK, Jahns L. Whole grains contribute only a small proportion of dietary fiber to the U.S. diet. Nutrients. 2017;9(2):153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Barrett EM, Foster SI, Beck EJ. Whole grain and high-fibre grain foods: how do knowledge, perceptions and attitudes affect food choice?. Appetite. 2020;149:104630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Augustin LSA, Aas A-M, Astrup A, Atkinson FS, Baer-Sinnott S, Barclay AW, Brand-Miller JC, Brighenti F, Bullo M, Buyken AE et al. Dietary fibre consensus from the International Carbohydrate Quality Consortium (ICQC). Nutrients. 2020;12(9):2553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Liu J, Micha R, Li Y, Mozaffarian D. Trends in food sources and diet quality among US children and adults, 2003–2018. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(4):e215262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Merlo C, Brener N, Kann L, McManus T, Harris D, Mugavero K. School-level practices to increase availability of fruits, vegetables, and whole grains, and reduce sodium in school meals—United States, 2000, 2006, and 2014. MMWR. 2015;64(33):905–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. United States Department of Agriculture . Final rule: child nutrition program flexibilities for milk, whole grains, and sodium requirements. [Internet]. December 12, 2018; [cited September 2021]. Available from: https://www.fns.usda.gov/cn/fr-121218.

- 26. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service, Center for Nutrition Policy and Promotion . Average Healthy Eating Index-2015 scores for Americans by poverty income ratio (PIR). What we eat in America, NHANES 2015–2016. 2020 [Internet]. Available from: https://fns-prod.azureedge.net/sites/default/files/media/file/FinalE_Draft_HEI_web_table_by_PIR_jf_citation_rev.pdf (accessed 2021 September 16).

- 27. Kirkpatrick SI, Dodd KW, Reedy J, Krebs-Smith SM. Income and race/ethnicity are associated with adherence to food-based dietary guidance among US adults and children. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012;112(5):624–35.e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Brewster PJ, Durward CM, Hurdle JF, Stoddard GJ, Guenther PM. The grocery purchase quality index-2016 performs similarly to the healthy eating index-2015 in a national survey of household food purchases. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2019;119(1):45–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Andreyeva T, Luedicke J. Federal food package revisions: effects on purchases of whole-grain products. Am J Prev Med. 2013;45(4):422–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ng SW, Hollingsworth BA, Busey EA, Wandell JL, Miles DR, Poti JM. Federal nutrition program revisions impact low-income households' food purchases. Am J Prev Med. 2018;54(3):403–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Jun S, Thuppal SV, Maulding MK, Eicher-Miller HA, Savaiano DA, Bailey RL. Poor dietary guidelines compliance among low-income women eligible for supplemental nutrition assistance program-education (SNAP-Ed). Nutrients. 2018;10(3):327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Leung CW, Musicus AA, Willett WC, Rimm EB. Improving the nutritional impact of the supplemental nutrition assistance program: perspectives from the participants. Am J Prev Med. 2017;52(2):S193–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hiza HA, Casavale KO, Guenther PM, Davis CA. Diet quality of Americans differs by age, sex, race/ethnicity, income, and education level. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2013;113(2):297–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service, Center for Nutrition Policy and Promotion . Average healthy eating index-2015 scores for Americans by race/ethnicity, ages 2 years and older. What we eat in America, NHANES 2015–2016. 2020 [Internet]. Available from: https://fns-prod.azureedge.net/sites/default/files/media/file/FinalE_Draft_HEI_web_table_by_Race_Ethnicity_jf_citation_rev.pdf (accessed 2021 September 16).

- 35. Taillie LS, Popkin BM, Ng SW, Murukutla N. Experimental studies of front-of-package nutrient warning labels on sugar-sweetened beverages and ultra-processed foods: a scoping review. Nutrients. 2020;12(2):569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Taillie LS, Bercholz M, Colchero MA, Popkin B, Reyes M, Corvalán C. Changes in food purchases after the Chilean policies on food labelling, marketing, and sales in schools: a before and after study. Lancet Planet Health. 2021;5(8):e526–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data described in the manuscript, code book, and analytic code will not be made available because of the proprietary nature of the household purchase data (we have a data use agreement for licensing the use of the NielsenIQ data that prohibits us from sharing the data).