ABSTRACT

Background

Parental involvement has been shown to favorably affect childhood weight-management interventions, but whether these interventions influence parental diet and cardiometabolic health outcomes is unclear.

Objectives

The aim was to evaluate whether a 1-y family-based childhood weight-management intervention altered parental nutrient biomarker concentrations and cardiometabolic risk factors (CMRFs).

Methods

Secondary analysis from a randomized-controlled, parallel-arm clinical trial (NCT00851201). Families were recruited from a largely Hispanic population and assigned to either standard care (SC; American Academy of Pediatrics overweight/obesity recommendations) or SC + enhanced program (SC+EP; targeted diet/physical activity strategies, skill building, and monthly support sessions). Nutrient biomarkers (plasma carotenoids and fat-soluble vitamins, RBC fatty acid profiles) and CMRFs (BMI, blood pressure, glucose, insulin, lipid profile, inflammatory and endothelial dysfunction markers, adipokines) were measured in archived samples collected from parents of participating children at baseline and end of the 1-y intervention.

Results

Parents in both groups (SC = 106 and SC+EP = 99) had significant reductions in trans fatty acid (–14%) and increases in MUFA (2%), PUFA n–6 (ɷ-6) (2%), PUFA n–3 (7%), and β-carotene (20%) concentrations, indicative of lower partially hydrogenated fat and higher vegetable oil, fish, and fruit/vegetable intake, respectively. Significant reductions in high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP; –21%) TNF-α (–19%), IL-6 (–19%), and triglycerides (–6%) were also observed in both groups. An additional significant improvement in serum insulin concentrations (–6%) was observed in the SC+EP parents. However, no major reductions in BMI or blood pressure and significant unfavorable trajectories in LDL-cholesterol and endothelial dysfunction markers [P-selectin, soluble intercellular adhesion molecule (sICAM), thrombomodulin] were observed. Higher carotenoid, MUFA, and PUFA (n–6 and n–3) and lower SFA and trans fatty acid concentrations were associated with improvements in circulating glucose and lipid measures, inflammatory markers, and adipokines.

Conclusions

The benefits of a family-based childhood weight-management intervention can spill over to parents, resulting in apparent healthier dietary shifts that are associated with modest improvements in some CMRFs.

Keywords: childhood obesity, parent spill-over, family-based intervention, fatty acids, carotenoids, nutrient biomarkers, cardiometabolic risk factors

The benefits of a family-based lifestyle intervention focused on children with overweight and obesity can spill over to parents, improving diet quality and some cardiometabolic risk factors.

Introduction

Childhood overweight/obesity is a major public health problem in the United States and is associated with adverse health outcomes throughout the life span (1). Current recommended strategies to prevent/treat excess weight gain during childhood include a combination of dietary modification, increased physical activity, and behavioral therapy (2–5). The majority of childhood weight-management interventions have been implemented in school and community settings with modest success (6–9). More recently, focus has shifted to the family/home environment, since parental involvement has been shown to be a key mediator in the effectiveness of childhood obesity interventions, especially in young children (10–16). These family-based interventions have sought to involve parents in various ways, ranging from solely targeting them as “agents of change” in their child's weight loss (17, 18) to participating in educational modules that support fostering a home environment that promotes healthy dietary habits, increases physical activity, and reduces sedentary behaviors (19–31).

Using the latter approach, we have documented that providing targeted family-based behavioral counseling as part of standard care (American Academy of Pediatrics overweight/obesity recommendations) (31) can help children with overweight/obesity adopt healthier eating patterns that are associated with modest improvements in BMI z score (BMI score standardized for age and sex) and several cardiometabolic risk factors (CMRFs) (30). The majority of parents who participated in this intervention were female (94% mothers) and nearly all of them (92%) had a BMI that classified them as being in the overweight or obese categories. This is consistent with the observation that children with BMI z scores over the 85% percentile tend to have home environments where either one or both parents are overweight/obese (23). Interestingly, maternal rather than paternal weight status (23) and nutrient intake (27) are stronger predictors of their child's dietary intake and weight status. This finding suggests that overall family lifestyle is predominantly driven by maternal outcomes (32, 33). Yet, very few family-oriented interventions (13, 19, 20, 22, 25, 27, 28, 34) have measured parental diet and their relation to health outcomes. Given the high prevalence of children as well as adults with obesity, a family-centered weight-management intervention that has beneficial effects for both the children and parents could have a significant public health impact (35, 36). Thus, the goal of the present study was to investigate whether a family-based weight-management intervention influenced parental nutrient intake patterns as well as CMRFs. We hypothesized that adoption of the lifestyle recommendations by the parents of the participating children would be reflected in circulating nutrient biomarker concentrations and lead to an improvement in their CMRF profile.

Methods

Study subjects and design

Detailed descriptions of the family-based management trial (NCT00851201 registered on clinicaltrials.gov), including design, intervention, and primary outcomes in the children, have been previously published (30, 31). This study focused on the parents (n = 205) of participating children (aged 7–12 y with baseline BMI z score ≥85th percentile) who had an archived fasting plasma, serum, and RBC sample at both baseline and end of the 1-y intervention. All study procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Albert Einstein College of Medicine. Approval to analyze de-identified samples and data was obtained from Tufts University/Tufts Medical Center Institutional Review Board.

Briefly, the study was a 2-arm, randomized, controlled, parallel-group trial comparing standard care alone (SC) with SC + enhanced program (SC + EP), and was conducted in a pediatric primary clinical care urban setting at Jacobi Medical Center (Bronx, NY). The SC intervention was based on the American Academy of Pediatrics’ evidence-based recommendations (37) and included an initial comprehensive visit to assess weight-related issues and to engage both the children and parents/guardians in developing intervention goals collaboratively. The pediatricians utilized the 35-item Pediatric Symptom Checklist to screen for emotional and behavioral dysfunction (38, 39) and the 5-item Habits questionnaire to assess dietary, physical activity, and sedentary behaviors (40) and made referrals to a registered dietitian. The Habits questionnaire addressed meals (e.g., eating as a family and avoid eating while watching TV), fruit and vegetable intake (e.g., increasing serving, excluding juices), beverage intake (e.g., decreasing sugar-sweetened beverages, choosing 1%-fat milk and water), fast food (e.g., decreasing frequency, avoiding super-sizing, and choosing healthier options), and physical activity/sedentary behavior (e.g., increasing moderate and vigorous physical activity and decreasing screen time). Families also received a dietary booklet targeting behaviors associated with excess body weight (soda, sugary beverages, junk food, fast foods) as well as the federal 2005 Dietary Guidelines, recipes, physical activity booklet (listing recreational facilities, tips to reduce TV viewing, and engage in 60 to 90 min of vigorous activity per day), and a monthly newsletter (tips for healthy living). During the quarterly follow-up pediatrician visits, the collaborative goals identified at the initial visit were reviewed and reiterated. The pediatricians who provided the SC to both study groups were blinded to treatment allocation.

The EP added a behavioral change component (8 weekly skill-building core sessions, each 1.5 to 2 h in duration), and subsequent monthly post-core support sessions focused on improving dietary behaviors and increasing engagement in physical activities provided by bilingual multidisciplinary staff. As described previously (31), the skill-building core sessions included alternating in-person groups and parent phone consultations. The in-person core group sessions consisted of food preparation or other skill activity for parents and children, followed by a physical activity session for the children and discussion session for parents to enhance parenting and problem-solving skills related to the themes covered in the joint family sessions. The monthly post-core support sessions consisted of engagement activities that were designed to provide ongoing support to parents/guardians and children during the intervention program. A group “meet up” approach was used to provide families with the opportunity to “check in” with EP multidisciplinary staff. Post-core session themes included “boot camp” circuit training, holiday themes with active games, and outing/field trips to a local park or within the campus grounds. Development of the EP components was guided by evidence-based recommendations and interventions and clinical experience in the target communities. Motivational enhancement based on motivation interviewing principles was used to engage both parent and child to evoke “their” reasons for changing unhealthy lifestyle behaviors. All intervention components were available in Spanish and English. The newsletter (provided to both groups) included healthful versions of Latinx recipes and featured information regarding popular Latin American fruits and vegetables sold in the local farmers’ market sponsored by the health system. Likewise, the physical activity sessions included popular Latin American dance steps.

Outcome variables and assessment

Nutrient biomarkers

Dietary and endogenous metabolism biomarkers were measured in fasting plasma and RBC samples collected from the parents both pre- and post-intervention. Dietary biomarkers included plasma carotenoid concentrations (pigmented fruit and vegetable intake) (41); fat-soluble vitamins A, D, E, and K (animal foods, fortified foods, supplements, and/or vegetable oils) (42); and RBC fatty acid profiles including linoleic [18:2n–6] and α-linolenic [18:3n–3] (vegetable oils) (43); eicosapentaenoic [EPA, 20:5n–3], docosapentaenoic [DPA, 22:5n–3], and docosahexaenoic [DHA, 22:6n-3] (fish) (44); pentadecanoic [15:0] (products containing dairy fat) (45); and trans fatty acids (ruminant/partially hydrogenated fat) (46). Endogenously synthesized SFA, MUFA, and PUFA n–6 profiles were also measured, and desaturase enzyme indices estimated to reflect de novo lipogenesis (DNL) (47).

HPLC was used to determine plasma carotenoid (lutein, zeaxanthin, cryptoxanthin, β-carotene, and lycopene) including vitamin A and vitamin E, (48) as well as vitamin K concentrations (49), as previously described. Vitamin D (25-hydroxyvitamin D) was measured using a commercially available kit (DiaSorin). The respective intra-assay and inter-assay CVs were 4% and 3.9% for carotenoids and 9% and 10% for vitamin D. For vitamin K, 2 pooled plasma samples were run as low (CV: 12%) and high (CV: 8%) controls with every batch. RBC fatty acid profiles were quantified using an established GC method (50–52). The inter-assay CVs ranged from 0.5% to 4.3% for fatty acids with concentrations >5 mol%, 1.8–7.1% for fatty acids between 1 and 5 mol%, and 2.8–11.1% for fatty acids <1 mol%. Desaturase enzyme activities were calculated as product to precursor ratios of individual fatty acids and included the following: stearoyl-CoA-desaturase [SCD1; palmitoleic (16:1n–7)/palmitic (16:0) and SCD2; oleic (18:1n–9)/ stearic (18:0)], delta-6-desaturase (D6D; dihomo-gamma-linolenic (20:3n–6)/linoleic (18:2n–6), and delta-5-desaturase (D5D; arachidonic (20:4n–6)/20:3n-6 (47).

Cardiometabolic risk factors

Available CMRF data for the parents from the primary clinical trial (31) and ancillary study (30) were divided into 7 broad categories: BMI, blood pressure (systolic and diastolic), glucose metabolism (fasting glucose and insulin), lipid profile [total cholesterol (TC), LDL cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, triglycerides (TGs)], markers of inflammation [high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP), TNF-α, IL-6], vascular adhesion [E-selectin, P-selectin, soluble intercellular adhesion molecule (sICAM)] and coagulation (thrombomodulin), and adipokines (leptin and adiponectin).

Fasting TC, LDL cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, TGs, insulin, and glucose were assessed using standard methods, as described for the primary study (31). Serum TNF-α, IL-6, E-selectin, P-selectin, sICAM, thrombomodulin, leptin and adiponectin concentrations were measured using commercially available multiplex assays (electro-chemiluminescence detection sandwich immunoassay: V-PLEX Human Cytokine Assays; V-PLEX Human Biomarker Assays; Human Metabolic Assays) from Meso Scale Discovery using a Meso Scale Discovery SECTOR Imager 2400. Serum hsCRP was measured by solid-phase, 2-site chemiluminescent immunometric assay using the IMMULITE 2000 (Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics). All CMRFs were measured in the fasted state.

Study sample

Sample size estimates for the primary clinical trial that provided the samples for the present study have been reported previously (31). For the 321 children in the primary trial, there were 287 parents after accounting for siblings, with 205 parents having an archived blood sample to perform the nutrient biomarker and CMRFs reported in the present study. With this given sample size of 106 in SC and 99 in SC + EP groups, there was 80% power to detect between-group differences of 0.39 SD with a 2-sided type I error rate of 5%. Additionally, to account for multiple comparisons, with a type I error rate = 0.005 under a conservative Bonferroni adjustment with 80% power, the minimum detectable standardized effect size was 0.52 SD.

Statistical analysis

The analysis was based on an intention-to-treat approach. Data from each parent were analyzed as per their initial assignment in the primary clinical trial to the SC or SC + EP group. Only parents with nutrient biomarkers and CMRF data at both baseline and 1-y were included in the analysis. Data were checked to identify and resolve reasons for missing values, inconsistencies, and out-of-range values.

Descriptive analyses of baseline characteristics of the SC and SC + EP groups were summarized using medians (IQR) or proportions. Nutrient biomarkers and CMRF data at baseline and 1-y were summarized for each group using geometric means and SD estimated from log-transformed values.

Differences in nutrient biomarker and CMRFs, as dependent variables, were assessed using a mixed-effects random intercept linear model with group, time, and group × time interaction as fixed effects. Participant was included as a random effect within the model and P values presented from the corresponding F-test for each fixed effect. Robust SEs were used to account for possible model misspecification. Dependent variables were log-transformed to facilitate reporting differences as mean % difference (95% CIs) and were calculated from back-transformed model-based least-square means as {2.72ᴧ[LSMEANS(1 y − baseline)] – 1} × 100%. Additionally, given the lack of intervention effect, least-square means for 1-y change in outcomes were reported from the mixed-effects model to represent pooled results across all parents among combined groups.

Spearman's ρ correlation between 1-y change in CMRFs with 1-y change in nutrient biomarkers was presented for each outcome pair. Correlation estimates were adjusted for sex, age, group, and baseline CMRFs (and additionally adjusted for baseline BMI for correlations not with BMI). Sex differences were not presented due to the small number of fathers in the sample (7 males in the SC and 6 males in the SC + EP group). All statistical analyses were performed with SAS software (version 9.4; SAS Institute, Inc.). Significance level was set at P < 0.05.

Results

Baseline characteristics

The baseline characteristics of the parents are listed in Table 1. Their ages ranged between 23 and 68 y and 93% were women (mothers). The mean BMI (kg/m2) was 33.0, with 7% being classified as normal weight, 27% in the overweight category, and 66% in the obese category. The majority of the parents in both groups had normal fasting glucose concentrations (85%) and blood pressure (67%), but approximately 20% met either the stage 1 or 2 hypertension classification (53). Approximately 70% of the parents self-identified as Hispanic/Latino, approximately 50% had less than a high school education, and over 70% reported an annual income less than $30,000.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of the parents at baseline1

| Variables | SC (n = 106) | SC + EP (n = 99) |

|---|---|---|

| Age,2 y | 37 (32–42) | 38 (33–43) |

| Sex, females/males, n/n | 99/7 | 93/6 |

| BMI,3 kg/m2 | 33.5 (6.9) | 32.5 (7.0) |

| BMI classification, n (%) | ||

| Normal weight (<25) | 2 (2%) | 10 (10%) |

| Overweight (≥25 to <30) | 25 (24%) | 30 (30%) |

| Obesity (≥30) | 76 (74%) | 59 (60%) |

| Blood pressure classification, n (%) | ||

| Normal (<120/<80 mmHg) | 63 (61%) | 71 (72%) |

| Elevated (120–129/<80 mmHg) | 20 (19%) | 11 (11%) |

| Stage 1 hypertension (130–139/80–80 mmHg) | 9 (9%) | 9 (9%) |

| Stage 2 hypertension (≥140/≥90 mmHg) | 12 (11%) | 8 (8%) |

| Fasting plasma glucose, n (%) | ||

| <100 mg/dL | 64 (60%) | 69 (70%) |

| 100–125 mg/dL | 24 (23%) | 19 (19%) |

| ≥125 mg/dL | 18 (17%) | 11 (11%) |

| Education, % | ||

| No formal schooling | 1.8% | 1.0% |

| Grades 1–11 | 50.0% | 54.5% |

| High school/GED | 29.3% | 20.2% |

| Some college/technical school certificate | 9.5% | 15.2% |

| Associate's/Bachelor's degree | 9.4% | 9.1% |

| Race/ethnicity, % | ||

| Hispanic/Latino | 70.8% | 78.8% |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 20.7% | 14.1% |

| White, Asian, and multiracial | 8.5% | 7.1% |

| Occupation, % | ||

| Homemaker | 56.6% | 52.5% |

| Employed full time | 12.3% | 12.1% |

| Employed part time | 20.8% | 21.2% |

| Unemployed/retired | 10.3% | 14.1% |

| Income, % | ||

| $0–$9999 | 39.6% | 37.4% |

| $10,000–$29,999 | 34.9% | 35.4% |

| $30,000 or above | 5.6% | 10.1% |

| Prefer not to answer | 19.8% | 17.2% |

| Marital status, % | ||

| Married/living as married | 59.4% | 54.6% |

| Widowed | 2.8% | 1.0% |

| Divorced/separated | 18.9% | 14.2% |

| Never married | 15.1% | 24.2% |

| Prefer not to answer | 3.8% | 6.1% |

EP, enhanced program; GED, general educational development; SC, standard care.

Median (IQR)

Mean (SD)

Nutrient biomarkers

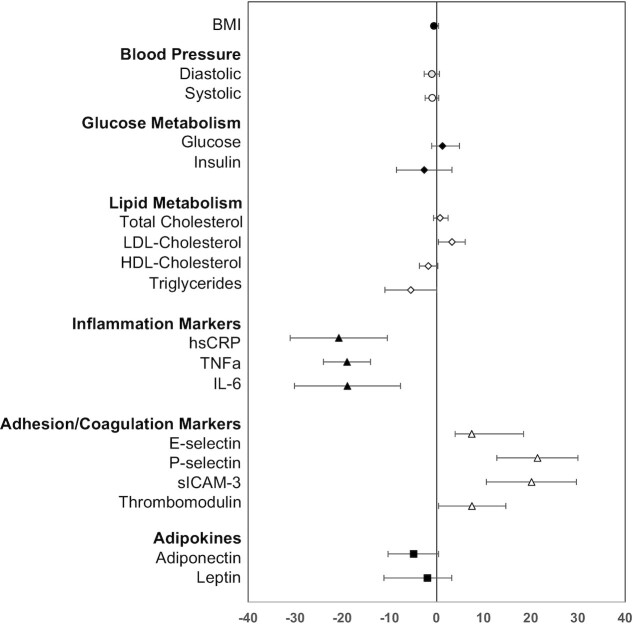

No significant effect of the intervention (group effect) was observed between parents in either the SC or SC + EP groups (Table 2). However, significant differences were observed in several nutrient biomarkers at the end of the 1-y intervention (time effect) in both groups. Thus, nutrient biomarker data from parents in both groups were combined and the pooled change over 1-y is summarized in Figure 1. Results indicate a significant increase in plasma concentrations of β-carotene (20%; predominantly yellow/orange fruits and vegetables) and lycopene (7%; predominantly tomatoes and derived products). There was a significant decrease in vitamin D (–7%) and vitamin E (–14%) concentrations. No significant changes were observed in plasma vitamin A or K concentrations. Among the fatty acids, total SFA was significantly decreased in both groups (–3%), primarily due to lower proportions of palmitic (–9%), with compensatory higher proportions of the minor SFAs (2% to 20% for myristic [14:0], stearic, arachidic [20:0], and lignoceric [24:0]). MUFAs significantly increased, especially those in the DNL pathway (6% to 18% for palmitoleic, hypogeic [16:1n–9], gondoic [20:1n–9], and nervonic [24:1n–9]). Total PUFA n–6, gamma-linolenic [18:3n–6], eicosadienoic [20:2n–6], dihomo-gamma-linolenic, arachidonic, and adrenic [22:4n–6] were significantly increased (2% to 13%), with the exception of docosapentaenoic [22:5n–6], which was significantly decreased (−18%). All PUFA n–3, including alpha-linolenic (15%) from vegetable oils and EPA, DPA, and DHA (6% to 11%) from fish and seafood, were significantly increased in the parents. Conversely, all trans-fatty acids, indicators of ruminant fat (palmitelaidic [16:1n–7 t], trans-7-hexadecenoic [16:1n–9 t], trans-vaccenic [18:1n–7 t], linoelaidic [18:2 t], conjugated linolenic acid (CLA)], and partially hydrogenated fat typically found in traditional margarines, commercially prepared fried foods, and savory snacks (elaidic [18:1n–9 t], petroselinic [18:1n–10 to 12 t]) were significantly decreased (–10% to –18%). Desaturase enzyme activity indices, SCD1 (8%) and D6D (12%) were significantly increased, while SCD2 (–2%) and D5D (–9%) were significantly decreased.

TABLE 2.

Nutrient biomarker concentrations and desaturase enzyme activities at baseline and end of the 1-y intervention by study group1

| SC | SC + EP | P 2 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biomarkers | Baseline3 | 1-y3 | Mean percent difference4 | Baseline3 | 1-y3 | Mean percent difference4 | Group | Time | Group × time |

| Carotenoids, μg/dL | |||||||||

| Lutein | 10.0 (5.6) | 10.3 (5.7) | 2.8 [–4.0, 10.0] | 11.1 (6.4) | 10.4 (5.9) | –6.7 [–13.8, 0.98] | 0.319 | 0.427 | 0.069 |

| Zeaxanthin | 3.4 (2.1) | 3.5 (2.0) | 4.5 [–2.9, 12.5] | 3.7 (2.4) | 3.7 (2.2) | 0.1 [–7.5, 8.3] | 0.319 | 0.412 | 0.426 |

| Cryptoxanthin | 9.1 (12.7) | 10.3 (14.0) | 12.8 [1.6, 25.4] | 10.8 (15.5) | 10.2 (16.0) | –5.9 [–16.2, 5.7] | 0.483 | 0.448 | 0.023 |

| β-Carotene | 15.3 (25.8) | 19.3 (32.7) | 26.3 [12.9, 41.3] | 16.6 (18.8) | 19.6 (22.6) | 17.8 [3.4, 34.1] | 0.652 | <0.001 | 0.422 |

| trans-Lycopene | 17.6 (11.3) | 18.7 (13.7) | 6.4 [-3.4, 17.2] | 20.4 (11.3) | 19.6 (11.8) | 4.2 [–13.8, 6.4] | 0.114 | 0.792 | 0.148 |

| Fat-soluble vitamins | |||||||||

| Vitamin A, μg/dL | 48.4 (14.9) | 47.2 (12.7) | –2.5 [–6.0, 1.1] | 46.5 (12.0) | 44.8 (11.5) | –3.5 [–8.5, 1.8] | 0.154 | 0.064 | 0.757 |

| Vitamin D, ng/mL | 17.9 (8.9) | 17.2 (7.2) | –4.8 [–11.9, 2.9] | 18.5 (9.6) | 16.9 (7.0) | –8.2 [–15.1, –0.8] | 0.915 | 0.017 | 0.513 |

| Vitamin E, μg/dL | 184 (120) | 168 (122) | –8.8 [–17.1, 0.3] | 188 (128) | 158 (121) | –16.3 [–24.8, –6.8] | 0.783 | <0.001 | 0.241 |

| Vitamin K, nM/L | 0.54 (0.69) | 0.55 (0.63) | 0.8 [–13.7, 17.7] | 0.54 (0.58) | 0.49 (0.52) | –8.1 [–22.1, 8.5] | 0.533 | 0.508 | 0.424 |

| Fatty acids, mol% | |||||||||

| SFAs | 41.1 (1.9) | 39.8 (2.0) | –3.3 [–4.4, –2.2] | 41.1 (2.1) | 39.8 (1.7) | –3.4 [–4.5, –2.2] | 0.934 | <.001 | 0.938 |

| 12:0 | 0.13 (0.12) | 0.12 (0.14) | –3.6 [–21.3, 18.0] | 0.14 (0.13) | 0.12 (0.12) | –10.8 [–25.2, 6.3] | 0.415 | 0.266 | 0.569 |

| 14:0 | 0.43 (0.16) | 0.53 (0.20) | 24.0 [14.5, 34.3] | 0.46 (0.18) | 0.56 (0.19) | 21.7 [12.3, 31.9] | 0.138 | <.001 | 0.746 |

| 15:0 | 0.35 (0.08) | 0.38 (0.11) | 10.8 [3.5, 18.6] | 0.36 (0.09) | 0.38 (0.14) | 7.1 [–1.3, 16.2] | 0.750 | 0.002 | 0.529 |

| 16:0 | 22.2 (2.1) | 20.1 (1.8) | –9.2 [–11.1, –7.2] | 22.1 (2.3) | 20.1 (1.6) | –8.9 [–10.8, –7.0] | 0.732 | <.001 | 0.86 |

| 18:0 | 16.2 (1.1) | 16.6 (1.1) | 2.4 [1.0, 3.8] | 16.2 (1.2) | 16.6 (1.1) | 2.4 [1.0, 3.8] | 0.873 | <.001 | 0.965 |

| 20:0 | 0.16 (0.03) | 0.19 (0.05) | 20.1 [14.5, 25.9] | 0.17 (0.03) | 0.20 (0.05) | 18.8 [12.8, 25.2] | 0.245 | <.001 | 0.772 |

| 22:0 | 0.46 (0.09) | 0.49 (0.11) | 8.3 [3.1, 13.7] | 0.46 (0.10) | 0.49 (0.11) | 5.3 [–0.3, 11.2] | 0.956 | <.001 | 0.453 |

| 24:0 | 1.07 (0.23) | 1.13 (0.31) | 5.6 [–0.1, 11.7] | 1.09 (0.24) | 1.15 (0.30) | 4.9 [–1.0, 11.1] | 0.398 | 0.012 | 0.869 |

| MUFAs | 16.3 (1.6) | 16.48 (1.5) | 1.5 [–0.3, 3.3] | 16.2 (1.5) | 16.5 (1.4) | 1.9 [0.1, 3.7] | 0.868 | 0.010 | 0.748 |

| 16:1n–7 | 0.49 (0.21) | 0.55 (0.21) | 11.9 [5.6, 18.5] | 0.50 (0.21) | 0.57 (0.28) | 13.3 [5.8, 21.4] | 0.54 | <0.001 | 0.772 |

| 16:1n–9 | 0.1 (0.03) | 0.12 (0.03) | 19.5 [12.5, 26.8] | 0.11 (0.03) | 0.13 (0.03) | 19.2 [11.9, 26.9] | 0.389 | <0.001 | 0.955 |

| 18:1n–7 | 1.72 (0.66) | 1.81 (0.77) | 5.5 [–3.4, 15.2] | 1.77 (0.73) | 1.71 (0.71) | –3.4 [–12.7, 6.8] | 0.736 | 0.784 | 0.192 |

| 18:1n–9 | 12.39 (1.3) | 12.32 (1.1) | –0.5 [–2.2, 1.2] | 12.2 (1.3) | 12.4 (1.2) | 1.3 [–0.3, 3.0] | 0.83 | 0.517 | 0.125 |

| 20:1n–9 | 0.21 (0.05) | 0.24 (0.06) | 16.4 [11.3, 21.7] | 0.20 (0.05) | 0.24 (0.05) | 14.9 [10.7, 19.3] | 0.751 | <0.001 | 0.659 |

| 22:1n–9 | 0.046 (0.02) | 0.049 (0.02) | 5.4 [–3.9, 15.7] | 0.05 (0.02) | 0.05 (0.02) | 3.5 [–5.9, 13.9] | 0.923 | 0.197 | 0.791 |

| 24:1n–9 | 1.12 (0.23) | 1.19 (0.28) | 6.2 [0.8, 11.9] | 1.10 (0.23) | 1.16 (0.26) | 5.8 [0.0, 12.0] | 0.421 | 0.003 | 0.922 |

| PUFA n–6 | 34.9 (2.4) | 35.7 (2.8) | 2.1 [0.9, 3.3] | 35.2 (2.3) | 36.0 (2.1) | 2.3 [1.2, 3.4] | 0.299 | <0.001 | 0.834 |

| 18:2n–6 | 13.7 (1.6) | 13.7 (1.7) | –0.1 [–1.7, 1.7] | 14.1 (2.2) | 13.9 (1.9) | –1.0 [–3.0, 1.0] | 0.187 | 0.444 | 0.459 |

| 18:3n–6 | 0.07 (0.04) | 0.08 (0.04) | 6.8 [–2.2, 16.6] | 0.07 (0.04) | 0.08 (0.05) | 17.8 [5.9, 31.0] | 0.671 | 0.001 | 0.163 |

| 20:2n–6 | 0.33 (0.08) | 0.38 (0.08) | 14.1 [11.1, 17.2] | 0.34 (0.08) | 0.39 (0.08) | 12.6 [9.3, 16.0] | 0.271 | <0.001 | 0.509 |

| 20:3n–6 | 1.86 (0.57) | 2.08 (0.58) | 12.0 [7.8, 16.4] | 1.86 (0.49) | 2.07 (0.52) | 11.5 [7.1, 16.0] | 0.956 | <0.001 | 0.858 |

| 20:4n–6 | 14.5 (1.3) | 14.8 (1.5) | 1.8 [0.1, 3.6] | 14.3 (1.7) | 14.7 (1.5) | 3.5 [1.5, 5.5] | 0.423 | <0.001 | 0.213 |

| 22:2n–6 | 0.072 (0.03) | 0.073 (0.04) | 1.9 [–10.1, 15.5] | 0.08 (0.04) | 0.07 (0.05) | –6.6 [–18.8, 7.4] | 0.289 | 0.601 | 0.362 |

| 22:4n–6 | 3.17 (0.69) | 3.54 (0.77) | 11.4 [8.2, 14.8] | 3.25 (0.70) | 3.61 (0.68) | 10.9 [7.3, 14.6] | 0.402 | <0.001 | 0.828 |

| 22:5n–6 | 0.97 (0.33) | 0.79 (0.29) | –18.6 [–24.5, –12.3] | 0.92 (0.34) | 0.80 (0.33) | –13.2 [–20.1, –5.7] | 0.595 | <0.001 | 0.258 |

| PUFA n–3 | 6.34 (1.5) | 6.77 (1.7) | 6.7% [3.5, 10.0] | 6.06 (1.5) | 6.51 (1.6) | 7.4 [3.7, 11.3] | 0.171 | <0.001 | 0.775 |

| 18:3n–3 | 0.19 (0.06) | 0.22 (0.07) | 18.0 [10.5, 25.9] | 0.19 (0.07) | 0.22 (0.07) | 15.2 [8.2, 22.7] | 0.464 | <0.001 | 0.609 |

| 20:5n–3 | 0.41 (0.21) | 0.43 (0.26) | 7.1 [0.3, 14.5] | 0.37 (0.21) | 0.42 (0.24) | 15.8 [8.0, 24.2] | 0.29 | <0.001 | 0.112 |

| 22:5n–3 | 2.03 (0.33) | 2.17 (0.41) | 6.9 [3.5, 10.4] | 2.03 (0.43) | 2.20 (0.41) | 8.3 [4.0, 12.7] | 0.817 | <0.001 | 0.631 |

| 22:6n–3 | 3.59 (1.2) | 3.79 (1.3) | 5.7 [1.9, 9.6] | 3.33 (1.1) | 3.54 (1.1) | 6.1 [1.7, 10.7] | 0.08 | <0.001 | 0.883 |

| trans-Fatty acids | 0.99 (0.25) | 0.88 (0.27) | –11.7 [–16.4, –6.7] | 1.00 (0.29) | 0.86 (0.27) | –14.5 [–18.6, –10.3] | 0.899 | <0.001 | 0.382 |

| 16:1n–7t | 0.084 (0.03) | 0.076 (0.02) | –8.9 [–13.6, –4.0] | 0.08 (0.02) | 0.07 (0.02) | –10.4 [–14.8, –5.8] | 0.874 | <0.001 | 0.653 |

| 16:1n–9t | 0.03 (0.01) | 0.02 (0.01) | –13.7 [–19.6, –7.4] | 0.03 (0.01) | 0.02 (0.01) | –16.1 [–22.0, –9.7] | 0.809 | <0.001 | 0.594 |

| 18:1n–7t | 0.16 (0.06) | 0.15 (0.07) | –7.3 [–15.0, 1.0%] | 0.18 (0.06) | 0.14 (0.07) | –19.2 [–26.6, –11.0] | 0.829 | <0.001 | 0.038 |

| 18:1n–9t | 0.3 (0.11) | 0.26 (0.10) | –14.0 [–18.7, –9.1] | 0.31 (0.12) | 0.26 (0.11) | –15.6 [–19.9, –11.1] | 0.974 | <0.001 | 0.627 |

| 18:1n–10–12t | 0.20 (0.08) | 0.17 (0.08) | –14.2 [–21.6, –6.1] | 0.20 (0.09) | 0.16 (0.07) | –18.0 [–25.5, –9.7] | 0.427 | <0.001 | 0.502 |

| 18:2t | 0.11 (0.06) | 0.10 (0.05) | –11.3 [–21.3, –0.1] | 0.11 (0.05) | 0.10 (0.06) | –10.5 [–20.7, 0.9] | 0.995 | 0.008 | 0.921 |

| 18:2CLA | 0.07 (0.03) | 0.07 (0.03) | –9.9 [–15.9, –3.4] | 0.08(0.03) | 0.07(0.03) | –9.2 [–15.2, –2.8] | 0.724 | <0.001 | 0.885 |

| Desaturase activity5 | |||||||||

| SCD1 (16:1n–7/16:0) | 0.02 (0.01) | 0.02 (0.01) | 7.1 [1.1, 13.4] | 0.02 (0.01) | 0.02 (0.01) | 8.8 [1.9, 16.3] | 0.513 | <0.001 | 0.713 |

| SCD2 (18:1n–9/18:0) | 0.77 (0.11) | 0.74 (0.09) | –2.9 [–5.2, –0.5] | 0.76 (0.12) | 0.75 (0.10) | –1.0 [–3.6, 1.6] | 0.817 | 0.03 | 0.299 |

| D6D (20:3n–6/18:2n–6) | 0.14 (0.04) | 0.15 (0.04) | 12.1 [7.4, 16.9] | 0.13 (0.03) | 0.15 (0.03) | 12.6 [7.5, 17.9] | 0.414 | <0.001 | 0.876 |

| D5D (20:4n–6/20:3n–6) | 7.80 (2.62) | 7.09 (2.13) | –9.1 [–12.7, –5.4] | 7.66 (2.63) | 7.11 (2.27) | –7.2 [–11.0, –3.2] | 0.832 | <0.001 | 0.473 |

Number of parents with both baseline and 1-y values: carotenoids (106 in SC and 99 in SC + EP); fat-soluble vitamins (91–106 in SC and 95–99 in SC + EP); fatty acids and desaturase activity (106 in SC and 99 in SC + EP). CLA, conjugated linolenic acid; D5D, delta-5-desaturase; D6D, delta-6-desaturase; EP, enhanced program; SC, standard care; SCD, stearoyl Co-A desaturase.

F-tests on fixed effects of study group, time, and group by time interaction from a mixed-effects random intercept linear model.

Values are geometric means (SD); SD was estimated from log-transformed values and based on equations described in Quan et al (54).

Values are % mean difference [95% CI], calculated from model-based least-square means as {2.72^[LSMEANS(1 y − baseline)] − 1} × 100%.

Values are calculated as fatty acid product:precursor ratios.

FIGURE 1.

Pooled 1-y change in nutrient biomarker concentrations and desaturase enzyme activities. For each individual nutrient biomarker, the mean % difference is plotted as the symbol and the 95% CIs displayed as the bars. The mean % difference value and 95% CIs were derived from least-square means calculated from a mixed-effects random intercept model with time (baseline or 1-y) as a fixed effect and a random intercept for subject correlations. A separate model was fitted for each log-transformed outcome. n = 205 and included parents in the SC and SC + EP groups with both a baseline and 1-y nutrient biomarker value. CLA, conjugated linolenic acid; D5D, delta-5-desaturase; D6D, delta-6-desaturase; EP, enhanced program; SC, standard care; SCD, stearoyl Co-A desaturase.

Cardiometabolic risk factors

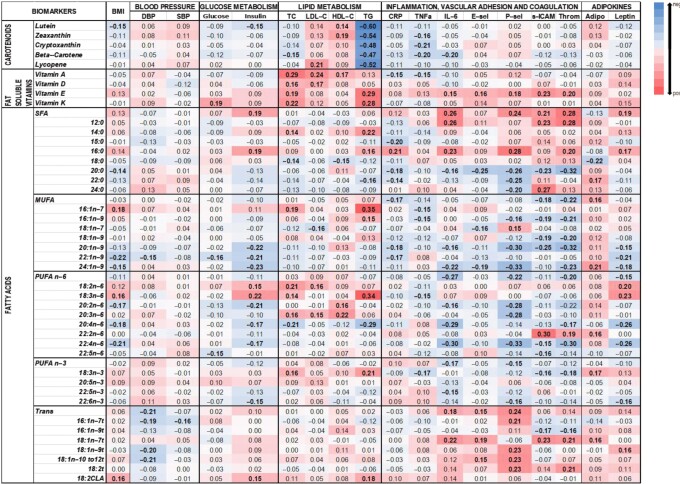

At the end of the 1-y intervention period, parents in both groups had significant decreases in circulating markers of inflammation (hsCRP, TNF-α, and IL-6) and increases in LDL-cholesterol, P-selectin, sICAM, and thrombomodulin concentrations (Table 3). Parents in the SC + EP group had additional significant decreases in insulin concentrations compared with parents in the SC group. No significant changes were observed in BMI, blood pressure, or glucose, TC and HDL-cholesterol, and adipokine concentrations. When both groups of parents were combined (Figure 2), significant improvements in TGs (–6%), hsCRP (–21%), TNF-α (–19%), and IL-6 (–19%) concentrations were observed. However, significant unfavorable increases in LDL cholesterol (3%), P-selectin (21%), sICAM (20%), and thrombomodulin (–8%) were also observed.

TABLE 3.

Cardiometabolic risk factors at baseline and end of the 1-y intervention by study group1

| SC | SC + EP | P 2 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiometabolic risk factors | Baseline3 | 1-y3 | Mean percent difference4 | Baseline3 | 1-y3 | Mean percent difference4 | Group | Time | Group × time |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 33.0 (6.2) | 32.9 (6.0) | –0.4 [–1.7, 0.9] | 31.8 (6.5) | 31.6 (6.8) | –0.7 [–2.1, 0.7] | 0.176 | 0.233 | 0.738 |

| Blood pressure, mmHg | |||||||||

| Diastolic | 67.3 (8.8) | 66.8 (8.9) | –0.8 [–2.9, 1.3] | 66.5 (8.8) | 65.6 (8.4) | –1.2 [–3.5, 1.1] | 0.158 | 0.200 | 0.786 |

| Systolic | 115.7 (14.9) | 114.9 (13.2) | –0.7 [-2.6, 1.2] | 114.6 (16.4) | 113.2 (14.2) | –1.1 [–3.3, 1.1] | 0.170 | 0.206 | 0.779 |

| Glucose metabolism | |||||||||

| Glucose, mg/dL | 103.4 (31.7) | 103.8 (46.3) | 0.3 [–5.7, 6.8] | 98.8 (26.6) | 101.1(27.3) | 2.3 [–1.0, 5.7] | 0.348 | 0.469 | 0.593 |

| Insulin, μU/mL | 19.19 (9.91) | 19.23 (10.3) | 0.2 [–8.0, 9.1] | 17.5 (9.39) | 16.5 (9.68) | –5.5 [–12.8, 2.4] | 0.030 | 0.357 | 0.328 |

| Lipid metabolism, mg/dL | |||||||||

| Total cholesterol | 179.2 (39.1) | 181.4 (35.2) | 1.2 [–1.8, 4.4] | 184.0 (39.8) | 184.2 (34.2) | 0.2 [–2.6, 3.1] | 0.472 | 0.499 | 0.636 |

| LDL cholesterol | 104.0 (35.1) | 106.9 (32.1) | 2.9 [–1.4, 7.5] | 107.0 (32.0) | 111.1 (28.9) | 3.7 [0.0, 7.6] | 0.270 | 0.024 | 0.801 |

| HDL cholesterol | 48.6 (10.7) | 48.4 (11.3) | 0.5 [–3.1, 2.2] | 48.9 (11.8) | 47.4 (10.4) | –3.1 [–5.7, –0.4] | 0.781 | 0.062 | 0.168 |

| Triglycerides | 115.2 (81.9) | 108.5 (70.0) | –5.8 [–12.8, 1.8] | 113.6 (87.4) | 107.7 (73.4) | –4.9 [–12.0, 2.9] | 0.776 | 0.051 | 0.862 |

| Inflammatory markers | |||||||||

| hsCRP, mg/L | 4.06 (20.4) | 3.64 (18.9) | –10.3 [–22.0, 3.2] | 3.86 (10.2) | 2.82 (9.41) | –26.9 [–37.0, –15.2] | 0.343 | <0.001 | 0.049 |

| TNF-ɑ, pg/mL | 4.82 (1.52) | 3.85 (1.44) | –20.1 [–25.4, –14.4] | 4.75 (1.71) | 4.08 (1.57) | –14.2 [–20.2, –7.8] | 0.63 | <0.001 | 0.164 |

| IL-6, pg/mL | 1.35 (2.86) | 1.12 (1.99) | –16.9 [–28.9, –3.0] | 1.17 (1.95) | 0.97 (1.27) | –17.6 [–30.0, –3.0] | 0.291 | 0.001 | 0.946 |

| Vascular adhesion and coagulation markers | |||||||||

| E-selectin, pg/mL | 4.12 (4.18) | 4.31 (3.92) | 3.7 [–9.7, 19.2] | 4.19 (6.06) | 4.68 (4.41) | 12.1 [–5.4, 32.9] | 0.564 | 0.176 | 0.485 |

| P-selectin, pg/mL | 37.4 (24.9) | 45.9 (28.4) | 23.1 [9.7, 38.2] | 36.5 (24.1) | 45.0 (26.1) | 24.6 [9.6, 41.7] | 0.887 | <0.001 | 0.891 |

| sICAM-3, ng/mL | 0.51 (0.38) | 0.57 (0.29) | 15.3 [0.8, 31.9] | 0.49 (0.36) | 0.64 (0.29) | 30.3 [13.8, 49.1] | 0.419 | <0.001 | 0.207 |

| Thrombomodulin, ng/mL | 1.76 (0.87) | 1.83 (0.72) | 4.6 [–4.8, 14.8] | 1.64 (0.85) | 1.84 (0.68) | 11.4 [0.0, 24.2] | 0.466 | 0.037 | 0.382 |

| Adipokines | |||||||||

| Adiponectin, mg/mL | 87.3 (48.4) | 84.1 (48.5) | –4.0 [–11.0, 3.6] | 89.4 (52.1) | 84.4 (47.1) | –5.7 [–12.6, 1.7] | 0.778 | 0.069 | 0.738 |

| Leptin, ng/mL | 25.6 (33.0) | 24.7 (34.1) | –3.4 [–14.1, 8.7] | 18.7 (34.4) | 18.5 (47.0) | –1.3 [–14.5, 13.9] | 0.015 | 0.613 | 0.823 |

Number of parents with both baseline and 1-y values: BMI (99 in SC and 94 in SC + EP); blood pressure (100 in SC and 94 in SC + EP); glucose metabolism, lipid profile, and hsCRP (103–106 in SC and 97–99 in SC + EP); other inflammatory, vascular adhesion, and coagulation markers and adipokines (98–99 in SC and 92–93 in SC + EP). EP, enhanced program; hsCRP, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein; SC, standard care; sICAM-3, soluble intercellular adhesion molecule 3.

F-tests on fixed effects of study group, time, and group by time interaction from a mixed-effects random intercept linear model.

Values are geometric means (SD); SD was estimated from log-transformed values.

Values are mean % difference [95% CI], calculated from model-based least-square means.

FIGURE 2.

Pooled 1-y change in CMRFs. For each individual CMRF, the mean % difference is plotted as the symbol and the 95% CIs displayed as the bars. The mean % difference value and 95% CIs are derived from least-square means calculated from a mixed-effects random intercept model with time (baseline or 1-y) as a fixed effect and a random intercept for subject correlations. A separate model is fitted for each log-transformed outcome. Numbers of parents in the SC and SC + EP groups with both a baseline and 1-y values were as follows: BMI (n = 193); blood pressure (n = 194); glucose metabolism (n = 205); lipid profile (n = 205); inflammatory, vascular adhesion, coagulation markers, and adipokines (n = 192). CMRF, cardiometabolic risk factor; EP, enhanced program; hsCRP, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein; SC, standard care; sICAM-3, soluble intercellular adhesion molecule 3.

Correlation between nutrient biomarkers and CMRFs

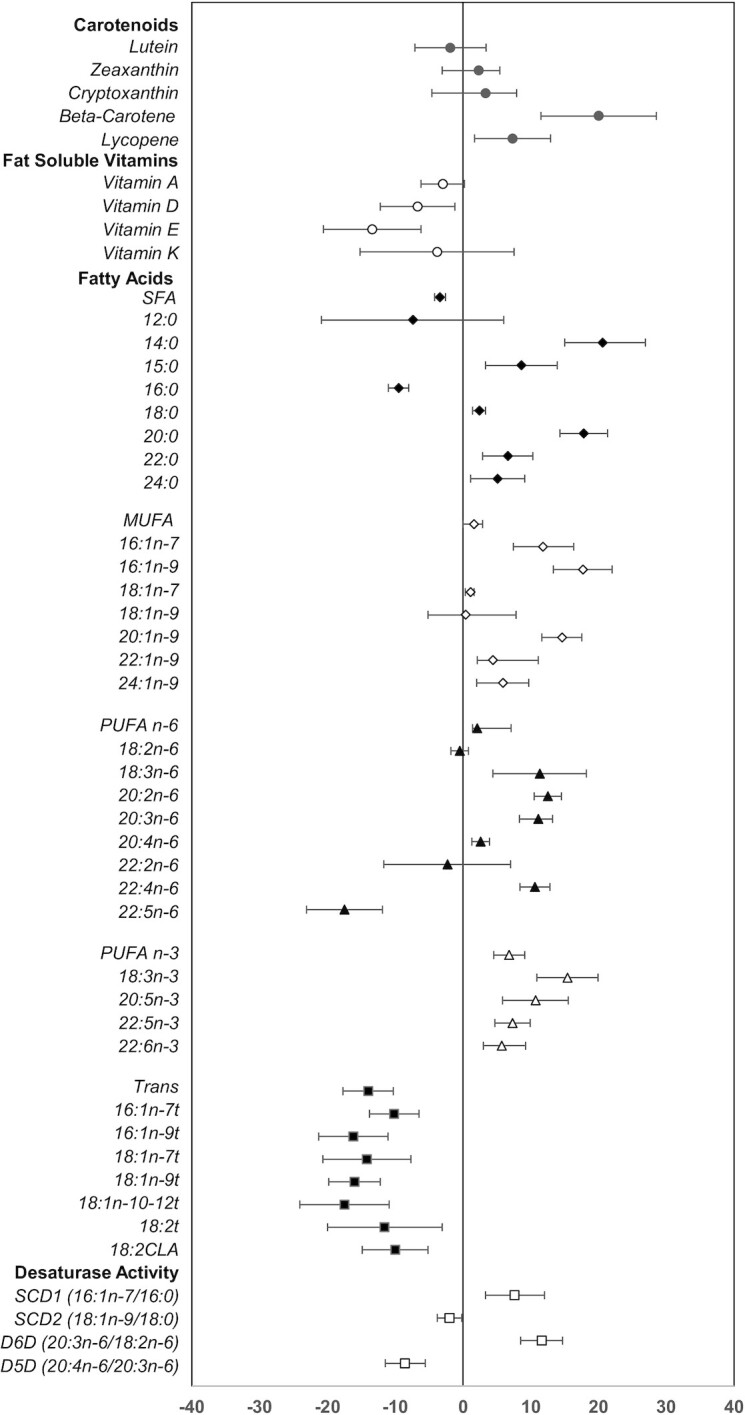

A heatmap of Spearman correlations between the change in nutrient biomarkers and change in CMRFs over the 1-y intervention period is presented in Figure 3.

FIGURE 3.

Heatmap of the correlation between nutrient biomarkers, desaturase enzyme activities, and CMRFs. The correlation between 1-y change in CMRFs with 1-y change in nutrient biomarkers for each outcome pair was estimated using Spearman ρ correlation, adjusted for sex, age, group, and baseline CMRFs (and additionally adjusted for baseline BMI for correlations not with BMI). Blue indicates a negative association, whereas redindicates a positive association, with the darkness of each color corresponding to the magnitude of the “r” value, with significant values (P < 0.05) in bold. The number of parents included ranged from 193 to 205. Adipo, adiponectin; CLA, conjugated linolenic acid; CMRF, cardiometabolic risk factor; CRP, C-reactive protein; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; E-sel, E-selectin; HDL-C, HDL cholesterol; LDL-C, LDL cholesterol; P-sel, P-selectin; SBP, systolic blood pressure; sICAM, soluble intercellular adhesion molecule; TC, total cholesterol; TG, triglyceride; Throm, thrombomodulin.

Carotenoids

The changes in plasma carotenoid concentrations (adjusted by TG concentrations) were generally associated with an improvement in CMRFs, including an inverse association with BMI (lutein), insulin (lutein), TGs (all), TNF-α (zeaxanthin, cryptoxanthin, and β-carotene), and IL-6 (β-carotene), and a positive association with HDL-cholesterol concentrations (lutein and zeaxanthin). An exception was lycopene (found in tomatoes and derived products), which was positively associated with LDL-cholesterol concentrations.

Fat-soluble vitamins

Positive associations were observed between the fat-soluble vitamins and glucose (vitamin K), TC (all), LDL-cholesterol (vitamins A and D), HDL-cholesterol (vitamin A), and TG (vitamins E and K) concentrations. Vitamin E also showed a positive association with inflammatory (IL-6), vascular adhesion (E-selectin, P-selectin, sICAM), and coagulation (thrombomodulin) markers. In contrast, vitamin A was negatively associated with hsCRP and TNF-α concentrations.

RBC fatty acids

Among the SFAs, associations with CMRFs varied by fatty acid type. Total SFAs, lauric [12:0], myristic, and palmitic were positively associated with insulin, TC, TG, hsCRP, IL-6, P-selectin, sICAM, thrombomodulin, and adiponectin concentrations. Longer-chain SFAs (stearic to lignoceric) were generally inversely associated with BMI (arachidic), TC and HDL cholesterol (stearic), hsCRP (arachidic and behenic), IL-6 (arachidic), E-selectin (arachidic), P-selectin (arachidic, behenic, and lignoceric), sICAM (arachidic), and thrombomodulin (arachidic). Leptin concentrations were negatively associated with stearic but positively associated with behenic. The odd-chain fatty acid pentadecanoic (biomarker of dairy fat) was inversely associated with hsCRP.

Among the MUFAs, hypogenic, palmitoleic, and cis-vaccenic, which are synthesized from carbohydrates via the DNL pathway, were positively associated with BMI, TC, TG, and P-selectin concentrations. Conversely, the n–9 fatty acid concentrations were negatively associated with BMI (erucic [22:1n–9] and nervonic), diastolic blood pressure (erucic), glucose (erucic), insulin and leptin (gondoic [20:1n–9], erucic, and nervonic), hsCRP (gondoic, erucic), IL-6 and P-selectin (gondoic, nervonic), and sICAM and thrombomodulin (oleic, gondoic). Total MUFAs, predominantly driven by nervonic were positively associated with adiponectin concentrations.

Among the n–6 class of fatty acids, total PUFA n–6, eicosadienoic, arachidonic, adrenic, and docosapentaenoic were negatively associated with several CMRFs including BMI, glucose, insulin, TC, TGs, IL-6, P-selectin, sICAM, thrombomodulin, and leptin. Interestingly, DHA was positively associated with sICAM, thrombomodulin, and adiponectin. Positive associations were also observed between linoleic and gamma-linolenic and BMI, insulin, TC and LDL-cholesterol, TG, and leptin concentrations.

The plant-derived n–3 PUFAs (alpha-linolenic) were positively associated with TC, TGs, and adiponectin and negatively associated with TNF-α, sICAM, and thrombomodulin. Among the marine-derived PUFAs, DHA and DPA but not EPA were negatively associated with insulin, P-selectin, and leptin.

The majority of the trans fatty acids were positively associated with inflammatory, vascular adhesion, and coagulation markers, as well as leptin. Surprisingly, they were negatively associated with blood pressure. CLA was the only trans fatty acid that showed a weak but significant positive association with BMI.

Desaturase enzyme indices

SCD1 was positively associated with BMI, TC, and TGs. SCD2 was also positively associated with TC, TGs, and adiponectin but negatively associated with sICAM and thrombomodulin concentrations. D6D was positively associated with HDL cholesterol and negatively with P-selectin. Conversely, D5D was negatively associated with the lipid profile and positively with P-selectin.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this study is the first to evaluate whether a 1-y family-based childhood weight-management intervention influenced parental nutrient patterns and cardiometabolic health outcomes. Results suggest an improvement in diet quality, as indicated by an increase in biomarkers of fruits and vegetables (carotenoids), dairy (pentadecanoic), vegetable oils (alpha-linolenic), and fish (EPA, DPA, DHA), and a decrease in biomarkers of ruminant and partially hydrogenated fat (trans fatty acids). Additionally, there were modest yet significant favorable improvements in 4 (TGs, hsCRP, TNF-α, and IL-6) of the 18 CMRFs measured at the end of the 1-y intervention. These improvements were weakly to moderately correlated with the shifts in nutrient patterns. However, we did not observe a significant reduction in BMI. Furthermore, the intervention did not slow the unfavorable trajectories observed in LDL cholesterol and markers of endothelial dysfunction (P-selectin, sICAM, and thrombomodulin). For the most part, changes in nutrient biomarkers and CMRFs in the parents were independent of the intervention group, suggesting limited added benefit of the enhanced program component. Nonetheless, these results document that SC alone, based on the American Academy of Pediatrics’ evidence-based recommendations that target lifestyle behaviors associated with excess body weight in children, can result in beneficial dietary and cardiometabolic health benefits in their parents when implemented within the context of a family-based clinical setting.

There is limited research on change in parental diet quality as part of family-based weight-management interventions (13). This is partly due to the challenges and inherent limitations associated with capturing dietary intake using subjective assessment tools (24-h recall, food-frequency questionnaires, food diaries) (55). To overcome this, we chose to objectively measure selected nutrients that reflected some of the dietary components of the intervention. We observed higher β-carotene and lycopene concentrations in the parents at the end of the intervention. This suggests increased consumption of foods such as carrots, tomato-based dishes, and fresh or canned fruits (apples, cherries, oranges). Of note, assessment of the dietary intake of the children in this study highlighted a “pizza and pasta”–based pattern, which was associated with their parents/guardian being born in the mainland United States and having a higher educational level (56). This highlights the important of parental acculturation status in influencing dietary behaviors of the family. The lower concentrations of the predominantly diet-derived trans fatty acids observed suggest that the parents in our study adhered to the lower fried foods/savory snack recommendations. Also noted were lower proportions of total SFAs and higher production of fatty acids in the DNL pathway. The lower SFA intake is most likely due to a combination of a lower intake of palmitic, which is the major dietary SFA in the diet, as well as increased endogenous desaturation to palmitoleic and conversion to downstream MUFA metabolites, as supported by the observation of higher SCD1 and lower SCD2 activities. The higher PUFA n–6 downstream metabolites observed reflect endogenous synthesis from linoleic via D6D. Additionally, the increase in diet-derived long-chain PUFA n–3 intake from both plant (alpha-linolenic) and marine (EPA, DPA, DHA) sources could account for the lower D5D activities, given the competition between PUFA n–6 and n–3 for D5D (47).

While it is difficult to contextualize our nutrient data given the dearth of comparable research, we identified a few studies that assessed dietary components using self-administered tools in parents participating in family-based intervention programs. Two studies, the High 5 for Preschool Kids (H5-KIDS) program, a home-based intervention to teach parents how to ensure a positive fruit-vegetable environment for their preschool child (25), and the Stoplight/Traffic-light Diet Treatment (20) both reported increases in fruit-vegetable servings in participating parents, which, in the latter study, was at the expense of high-fat/high-sugar foods. Among the 3 studies that reported dietary total fat intake of participating parents, 1 study (28) achieved significant reductions in total fat intake and to a smaller extent for sugar and complex carbohydrate intake following family dietary coaching to improve nutritional intake and weight control, while the other (19) observed a significant decrease in total fat and sodium intake, but only in non-Hispanic and not in Mexican-American families who participated in a family-based cardiovascular disease risk-reduction intervention. The third study (57) explored the efficacy of a 12-wk, culturally specific, obesity-prevention program in low-income, inner-city African-American girls and their mothers and showed significant differences between the treatment and control mothers for daily SFA intake and percentage of calories from fat. These data, including the present results, suggest that parent involvement in family-based interventions with a specific dietary component, whether indirect (targeting their child's dietary intake) or direct (targeting both parent and child), can result in modest shifts in their dietary behaviors.

An unexpected finding in this study was the decrease in concentrations of fat-soluble vitamins, most notably for vitamins D and E. These vitamins are transported in the circulation via TG-rich particles; however, similar results were still observed after correcting for TG concentrations. It is possible that an overall decrease in intake of fortified foods, such as cereals, and fried foods prepared with vegetable oils, major dietary sources of vitamins D and E, respectively, could account for this observation. Alternatively, evidence also suggests that, in the presence of obesity, there is a tendency for higher incorporation and storage of fat-soluble vitamins, especially in adipose tissue, which results in lower circulating concentrations (58).

Most family-based studies are designed to assess whether parent involvement enhanced the effectiveness of interventions that aimed to change their child's weight, with a few studies (20, 26, 29, 34, 59) also targeting parental weight. However, these latter studies had mixed results. Some studies (20, 26) that targeted weight loss as an outcome in both parents and children reported better success in parents. However, another family-based exploratory community study in low-income Latino mothers and daughters did not show any significant differences in BMI in mother–daughter dyads in the experimental versus control group, after adjusting for baseline BMI as a covariate (34). Among school- and community-based childhood weight-management programs, 1 study observed a spillover intervention effect on parents, resulting in a significant decrease in BMI (59), while the other study did not (29). We also did not observe a significant reduction in parental BMI, although there was a downward trend after adjustment for baseline variables. Nevertheless, we observed improvements in several obesity-related CMRFs, notably systemic inflammation markers and insulin and TG concentrations. Additionally, these favorable changes in CMRFs were associated with the changes in nutrient profiles. Whereas inverse associations between carotenoids and CMRFs (58) and positive associations between fatty acids, including trans fatty acids, and inflammation/endothelial dysfunction (60–62) have been previously documented in overweight and obese adults, our findings provide preliminary evidence that the shifts toward healthier eating patterns can extend beyond changes in BMI and improve cardiometabolic health outcomes, within a family-based childhood obesity intervention.

Excess body weight has also been associated with lower adiponectin and higher leptin concentrations (63). The absolute concentrations of these adipokines were not significantly altered by the intervention, and this is most likely due to the lack of an effect on BMI, as their concentrations tend to correlate with fat mass. However, the positive associations observed between both adipokines and several of the endogenously synthesized SFAs, MUFAs, and PUFA n–6 fatty acids at the end of the 1-y intervention suggest a potential modulatory effect that warrants further investigation (64).

Of note, there were unfavorable increases in LDL-cholesterol concentrations at the end of the study. This could reflect increased transfer of TGs from VLDL to LDL, as supported by the concomitant lowering of TG concentrations observed. Also observed were increases in concentrations of P-selectin, sICAM, and thrombomodulin, suggestive of endothelial injury (65), which may already be present in this group of parents with overweight and obesity, the trajectories of which the dietary components targeted in our intervention were unable to slow or reverse.

Strengths of this study include the randomized design, drawing on the social-ecological framework to develop intervention components and the principles of social cognitive theory, and social marketing to address the interaction of behavioral, environmental, and personal factors; collaborative goal-setting to empower families; and an expanded dataset of overweight- and obesity-related CMRF variables, in an underserved, high-obesity risk group of largely Hispanic mothers who participated in their child's weight-management intervention. Given the extremely low participation of fathers in our study, we were limited in our ability to analyze an intervention effect on paternal diet. Second, the clinical trial was not designed to address parental adherence to the lifestyle intervention per se. Consequently, the parental dietary and physical activity assessments were limited. We chose to utilize an objective biomarker approach, focusing on selected nutrients, since self-report dietary intake, especially in populations with overweight and obesity, has been associated with under- and overreporting of certain food groups (66, 67). However, there are a limited number of validated nutrients of dietary intake and none that capture total energy intake/balance, sugar-sweetened beverage intake, or quantity of the food consumed. Third, the possibility cannot be ruled out that the changes observed in CMRFs could potentially be mediated by increased physical activity levels of the parents and not solely related to modification of dietary behaviors. Finally, the majority of the changes in nutrient concentrations and CMRFs were observed in both groups of parents, which was contrary to our original hypothesis, and suggests limited added benefit of the enhanced module. While this could be because the dietary guidance/tools were provided to all participating families as part of SC and reinforced during the quarterly visits by the highly specialized study pediatricians and research staff, it is possible that other components, such as intensity of contacts, adherence, and/or resource sharing between groups, may have contributed to these observations.

In conclusion, this study documents a beneficial outcome of a family-based childhood weight-management intervention delivered within a primary care setting on parental nutrient patterns, which were associated with favorable changes in selected CMRFs, despite non-significant changes in BMI. These findings have significant public health implications since improving diet quality and health outcomes in a parent with overweight or obesity using the same guidelines that targeted their child could potentially result in a major cost–benefit of family-based interventions, which merits further investigation.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We acknowledge the assistance of Jean Galluccio, BS, and Gayle Petty, MBA, in the Cardiovascular Nutrition and Nutrition Evaluation Laboratories for the dietary biomarkers and CMRF analyses. We acknowledge Chia-Fang Tsai, MS, in the HNRCA Biostatistics and Data Management Core Unit for assistance with statistical programming. The authors’ responsibilities were as follows—NRM, AHL, and JW-R: contributed to designing and conducting the present study; JW-R, AEG-P, PMD, MG, and YM-R: contributed to designing and conducting the primary intervention; XX and KB: assumed responsibility for data analysis; NRM: wrote the manuscript, with editing from AHL, JW-R, AEG-P, PMD, XX, KB, MG, and YM-R; and all authors: read and approved the final manuscript.

Notes

Supported by research program grants from the National Institutes of Health (NIH R01 HL101236), National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK R18 DK075981), New York Regional Center for Diabetes Translational Research (DK111022), and the US Department of Agriculture under agreement no. 58-1950-4-401.

Author disclosures: The authors report no conflicts of interest. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of authors and do not necessarily reflect the view of the US Department of Agriculture.

Abbreviations used: CLA, conjugated linolenic acid; CMRF, cardiometabolic risk factor; D5D, delta-5-desaturase; D6D, delta-6-desaturase; DNL, de novo lipogenesis; EP, enhanced program; hsCRP, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein; SC, standard care; SCD, stearoyl Co-A desaturase; sICAM, soluble intercellular adhesion molecule; TC, total cholesterol; TG, triglyceride.

Contributor Information

Nirupa R Matthan, Email: nirupa.matthan@tufts.edu, Cardiovascular Nutrition Laboratory, Jean Mayer USDA Human Nutrition Research Center on Aging at Tufts University, Boston, MA, USA.

Kathryn Barger, Biostatistics and Data Management Core Unit, Jean Mayer USDA Human Nutrition Research Center on Aging at Tufts University, Boston, MA, USA.

Judith Wylie-Rosett, Department of Epidemiology and Population Health, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, NY, USA.

Xiaonan Xue, Department of Epidemiology and Population Health, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, NY, USA.

Adriana E Groisman-Perelstein, Department of Pediatrics, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Jacobi Medical Center, Bronx, NY, USA.

Pamela M Diamantis, Department of Pediatrics, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Jacobi Medical Center, Bronx, NY, USA.

Mindy Ginsberg, Department of Epidemiology and Population Health, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, NY, USA.

Yasmin Mossavar-Rahmani, Department of Epidemiology and Population Health, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, NY, USA.

Alice H Lichtenstein, Cardiovascular Nutrition Laboratory, Jean Mayer USDA Human Nutrition Research Center on Aging at Tufts University, Boston, MA, USA.

Data Availability

Data described in the manuscript, code book, and analytic code will be made available upon request. Data sharing will require a signed agreement that addresses expenses for data transfer and protects participant confidentiality by exchanging de-identified data in protected formats.

References

- 1. Fryar CD, Carroll MD, Afful J. Prevalence of overweight, obesity, and severe obesity among children and adolescents aged 2–19 years: United States, 1963–1965 Through 2017–2018. [Internet]. Atlanta (GA): CDC. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hestat/obesity-child-17-18/obesity-child.htm(accessed 14 September 2021). [Google Scholar]

- 2. Barlow SE. Expert committee recommendations regarding the prevention, assessment, and treatment of child and adolescent overweight and obesity: summary report. Pediatrics. 2007;120:S164–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Davis MM, Gance-Cleveland B, Hassink S, Johnson R, Paradis G, Resnicow K. Recommendations for prevention of childhood obesity. Pediatrics. 2007;120(Suppl 4):S229–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Koplan JP, Liverman CT, Kraak VI, Wisham SL. Progress in preventing childhood obesity: how do we measure up?. Washington (DC): National Academy Press, Institute of Medicine; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Styne DM, Arslanian SA, Connor EL, Farooqi IS, Murad MH, Silverstein JH, Yanovski JA. Pediatric obesity—assessment, treatment, and prevention: an Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017;102(3):709–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kropski JA, Keckley PH, Jensen GL. School-based obesity prevention programs: an evidence-based review. Obesity. 2008;16(5):1009–18.. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/oby.2008.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Shaya FT, Flores D, Gbarayor CM, Wang J. School-based obesity interventions: a literature review. J Sch Health. 2008;78(4):189–96.. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2008.00285.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kenney EL, Wintner S, Lee RM, Austin SB. Obesity prevention interventions in US public schools: are schools using programs that promote weight stigma. Prev Chron Dis. 2017;14:160605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Blondin K, Crawford P, Orta-Aleman D, Randel-Schreiber H, Strochlic R, Webb K, Woodward-Lpoz G. School-based interventions for promtoing nutrition and physical activity & preventing obesity: overview of studies and findings [Internet]. Nutrition Policy Institute for the California Department of Public Health; 2017. Available from:https://ucanr.edu/sites/NewNutritionPolicyInstitute/files/317758.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Berge JM, Everts JC. Family-based interventions targeting childhood obesity: a meta-analysis. Childhood Obesity. 2011;7(2):110–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Black AP, D'Onise K, McDermott R, Vally H, O'Dea K. How effective are family-based and institutional nutrition interventions in improving children's diet and health? A systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2017;17(1):818, doi: 10.1186/s12889-017-4795-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Danford CA, Schultz CM, Marvicsin D. Parental roles in the development of obesity in children: challenges and opportunities. Res Rep Biol. 2015;6:39–53. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hingle MD, O'Connor TM, Dave JM, Baranowski T. Parental involvement in interventions to improve child dietary intake: a systematic review. Prev Med. 2010;51(2):103–11.. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2010.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lindsay AC, Sussner KM, Kim J, Gortmaker S. The role of parents in preventing childhood obesity. Future Child. 2006;16(1):169–86.. doi: 10.1353/foc.2006.0006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mehdizadeh A, Nematy M, Vatanparast H, Khadem-Rezaiyan M, Emadzadeh M. Impact of parent engagement in childhood obesity prevention interventions on anthropometric indices among preschool children: a systematic review. Childhood Obesity. 2020;16(1):3–19.. doi: 10.1089/chi.2019.0103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wood AC, Blissett JM, Brunstrom JM, Carnell S, Faith MS, Fisher JO, Hayman LL, Khalsa AS, Hughes SO, Miller ALet al. . Caregiver influences on eating behaviors in young children: a scientific statement from the american heart association. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9(10):e014520. doi: 10.1161/jaha.119.014520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Golan M, Fainaru M, Weizman A. Role of behaviour modification in the treatment of childhood obesity with the parents as the exclusive agents of change. Int J Obesity Rel Metab Disord. 1998;22(12):1217–24.. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0800749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Golan M, Kaufman V, Shahar DR. Childhood obesity treatment: targeting parents exclusively v. parents and children. Br J Nutr. 2006;95(5):1008–15.. doi: 10.1079/bjn20061757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Nader PR, Sallis JF, Patterson TL, Abramson IS, Rupp JW, Senn KL, Atkins CJ, Roppe BE, Morris JA, Wallace JPet al. . A family approach to cardiovascular risk reduction: results from the San Diego Family Health Project. Health Educ Q. 1989;16(2):229–44.. doi: 10.1177/109019818901600207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Epstein LH, Gordy CC, Raynor HA, Beddome M, Kilanowski CK, Paluch R. Increasing fruit and vegetable intake and decreasing fat and sugar intake in families at risk for childhood obesity. Obes Res. 2001;9(3):171–8.. doi: 10.1038/oby.2001.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Epstein LH, Paluch RA, Raynor HA. Sex differences in obese children and siblings in family-based obesity treatment. Obes Res. 2001;9(12):746–53.. doi: 10.1038/oby.2001.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Epstein LH, Wing RR, Koeske R, Valoski A. Effects of diet plus exercise on weight change in parents and children. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1984;52(3):429–37.. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.52.3.429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gray LA, Hernandez Alava M, Kelly MP, Campbell MJ. Family lifestyle dynamics and childhood obesity: evidence from the millennium cohort study. BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):500. doi: 10.1186/s12889-018-5398-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gunnarsdottir T, Njardvik U, Olafsdottir AS, Craighead LW, Bjarnason R. The role of parental motivation in family-based treatment for childhood obesity. Obesity. 2011;19(8):1654–62.. doi: 10.1038/oby.2011.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Haire-Joshu D, Elliott MB, Caito NM, Hessler K, Nanney MS, Hale N, Boehmer TK, Kreuter M, Brownson RC. High 5 for Kids: the impact of a home visiting program on fruit and vegetable intake of parents and their preschool children. Prev Med. 2008;47(1):77–82.. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2008.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Krystia O, Ambrose T, Darlington G, Ma DWL, Buchholz AC, Haines J. A randomized home-based childhood obesity prevention pilot intervention has favourable effects on parental body composition: preliminary evidence from the Guelph Family Health Study. BMC Obesity. 2019;6(1):10. doi: 10.1186/s40608-019-0231-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Oliveria SA, Ellison RC, Moore LL, Gillman MW, Garrahie EJ, Singer MR. Parent-child relationships in nutrient intake: the Framingham Children's Study. Am J Clin Nutr. 1992;56(3):593–8.. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/56.3.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Paineau DL, Beaufils F, Boulier A, Cassuto DA, Chwalow J, Combris P, Couet C, Jouret B, Lafay L, Laville Met al. . Family dietary coaching to improve nutritional intakes and body weight control: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2008;162(1):34–43.. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2007.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Robertson W, Fleming J, Kamal A, Hamborg T, Khan KA, Griffiths F, Stewart-Brown S, Stallard N, Petrou S, Simkiss Det al. . Randomised controlled trial evaluating the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of ‘Families for Health’, a family-based childhood obesity treatment intervention delivered in a community setting for ages 6 to 11 years. Health Technol Assess (Rockv). 2017;21(1):1–180.. doi: 10.3310/hta21010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Matthan NR, Wylie-Rosett J, Xue X, Gao Q, Groisman-Perelstein AE, Diamantis PM, Ginsberg M, Mossavar-Rahmani Y, Barger K, Lichtenstein AH. Effect of a family-based intervention on nutrient biomarkers, desaturase enzyme activities, and cardiometabolic risk factors in children with overweight and obesity. Curr Dev Nutr. 2020;4(1):nzz138. doi: 10.1093/cdn/nzz138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wylie-Rosett J, Groisman-Perelstein AE, Diamantis PM, Jimenez CC, Shankar V, Conlon BA, Mossavar-Rahmani Y, Isasi CR, Martin SN, Ginsberg Met al. . Embedding weight management into safety-net pediatric primary care: randomized controlled trial. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Activity. 2018;15(1):12. doi: 10.1186/s12966-017-0639-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Dhana K, Haines J, Liu G, Zhang C, Wang X, Field AE, Chavarro JE, Sun Q. Association between maternal adherence to healthy lifestyle practices and risk of obesity in offspring: results from two prospective cohort studies of mother-child pairs in the United States. BMJ. 2018;362:k2486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Fuemmeler BF, Lovelady CA, Zucker NL, Østbye T. Parental obesity moderates the relationship between childhood appetitive traits and weight. Obesity. 2013;21(4):815–23.. doi: 10.1002/oby.20144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Olvera N, Bush JA, Sharma SV, Knox BB, Scherer RL, Butte NF. BOUNCE: a community-based mother–daughter healthy lifestyle intervention for low-income Latino families. Obesity. 2010;18(S1):S102–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Epstein LH, Paluch RA, Wrotniak BH, Daniel TO, Kilanowski C, Wilfley D, Finkelstein E. Cost-effectiveness of family-based group treatment for child and parental obesity. Childhood Obesity. 2014;10(2):114–21.. doi: 10.1089/chi.2013.0123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Goldfield GS, Epstein LH, Kilanowski CK, Paluch RA, Kogut-Bossler B. Cost-effectiveness of group and mixed family-based treatment for childhood obesity. Int J Obesity Rel Metab Disord. 2001;25(12):1843–9.. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Spear BA, Barlow SE, Ervin C, Ludwig DS, Saelens BE, Schetzina KE, Taveras EM. Recommendations for treatment of child and adolescent overweight and obesity. Pediatrics. 2007;120(Suppl 4):S254–88.. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2329F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Jellinek MS, Murphy JM. The recognition of psychosocial disorders in pediatric office practice: the current status of the pediatric symptom checklist. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 1990;11(5):273–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Murphy JM, Reede J, Jellinek MS, Bishop SJ. Screening for psychosocial dysfunction in inner-city children: further validation of the Pediatric Symptom Checklist. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1992;31(6):1105–11.. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199211000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wright ND, Groisman-Perelstein AE, Wylie-Rosett J, Vernon N, Diamantis PM, Isasi CR. A lifestyle assessment and intervention tool for pediatric weight management: the HABITS questionnaire. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2011;24(1):96–100.. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-277X.2010.01126.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Al-Delaimy WK, Ferrari P, Slimani N, Pala V, Johansson I, Nilsson S, Mattisson I, Wirfalt E, Galasso R, Palli Det al. . Plasma carotenoids as biomarkers of intake of fruits and vegetables: individual-level correlations in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC). Eur J Clin Nutr. 2005;59(12):1387–96.. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Johnson EJ, Mohn ES. Fat-soluble vitamins. World Rev Nutr Diet. 2015;111:38–44.. doi: 10.1159/000362295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Katan MB, van Birgelen A, Deslypere JP, Penders M, van Staveren WA. Biological markers of dietary intake, with emphasis on fatty acids. Ann Nutr Metab. 1991;35(5):249–52.. doi: 10.1159/000177653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Arab L. Biomarkers of fat and fatty acid intake. J Nutr. 2003;133(3):925S–32S.. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.3.925S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Venn-Watson S, Lumpkin R, Dennis EA. Efficacy of dietary odd-chain saturated fatty acid pentadecanoic acid parallels broad associated health benefits in humans: could it be essential?. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):8161. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-64960-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Yeak ZW, Chuah KA, Tan CH, Ezhumalai M, Chinna K, Sundram K, Karupaiah T. Providing comprehensive dietary fatty acid profiling from saturates to polyunsaturates with the Malaysia Lipid Study-Food Frequency Questionnaire: validation using the triads approach. Nutrients. 2020;13(1):120. doi: 10.3390/nu13010120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Vessby B, Gustafsson IB, Tengblad S, Berglund L. Indices of fatty acid desaturase activity in healthy human subjects: effects of different types of dietary fat. Br J Nutr. 2013;110(5):871–9.. doi: 10.1017/s0007114512005934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Yeum KJ, Booth SL, Sadowski JA, Liu C, Tang G, Krinsky NI, Russell RM. Human plasma carotenoid response to the ingestion of controlled diets high in fruits and vegetables. Am J Clin Nutr. 1996;64(4):594–602.. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/64.4.594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Davidson KW, Sadowski JA. Determination of vitamin K compounds in plasma or serum by high-performance liquid chromatography using postcolumn chemical reduction and fluorimetric detection. Methods Enzymol. 1997;282:408–21.. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(97)82124-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Djoussé L, Matthan NR, Lichtenstein AH, Gaziano JM. Red blood cell membrane concentration of cis-palmitoleic and cis-vaccenic acids and risk of coronary heart disease. Am J Cardiol. 2012;110(4):539–44.. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2012.04.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Matsumoto C, Matthan NR, Lichtenstein AH, Gaziano JM, Djoussé L. Red blood cell MUFAs and risk of coronary artery disease in the Physicians' Health Study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2013;98(3):749–54.. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.113.059964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Matthan NR, Ip B, Resteghini N, Ausman LM, Lichtenstein AH. Long-term fatty acid stability in human serum cholesteryl ester, triglyceride, and phospholipid fractions. J Lipid Res. 2010;51(9):2826–32.. doi: 10.1194/jlr.D007534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, Casey DE, Collins KJ, Himmelfarb CD, DePalma SM, Gidding S, Jamerson KA, Jones DWet al. . 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Hypertension. 2018;71(6):e13–e115.. doi: 10.1161/HYP.0000000000000065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Quan H, Zhang J.. Estimate of standard deviation for a log-transformed variable using arithmetric means and standard deviations. Statistics in Medicine. 2003;22(17):2723–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Ravelli MN, Schoeller DA. Traditional self-reported dietary instruments are prone to inaccuracies and new approaches are needed. Front Nutr. 2020;7:90. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2020.00090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Assassi P, Selwyn BJ, Lounsbury D, Chan W, Harrell M, Wylie-Rosett J. Baseline dietary patterns of children enrolled in an urban family weight management study: associations with demographic characteristics. Child Adolesc Obesity. 2021;4(1):37–59.. doi: 10.1080/2574254X.2020.1863741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Stolley MR, Fitzgibbon ML. Effects of an obesity prevention program on the eating behavior of African American mothers and daughters. Health Educ Behav. 1997;24(2):152–64.. doi: 10.1177/109019819702400204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Harari A, Coster ACF, Jenkins A, Xu A, Greenfield JR, Harats D, Shaish A, Samocha-Bonet D. Obesity and insulin resistance are inversely associated with serum and adipose tissue carotenoid concentrations in adults. J Nutr. 2020;150(1):38–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Coffield E, Nihiser AJ, Sherry B, Economos CD. Shape up Somerville: change in parent body mass indexes during a child-targeted, community-based environmental change intervention. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(2):e83–9.. doi: 10.2105/ajph.2014.302361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Giardina S, Sala-Vila A, Hernández-Alonso P, Calvo C, Salas-Salvadó J, Bulló M. Carbohydrate quality and quantity affects the composition of the red blood cell fatty acid membrane in overweight and obese individuals. Clin Nutr. 2018;37(2):481–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Harvey KA, Arnold T, Rasool T, Antalis C, Miller SJ, Siddiqui RA. trans-Fatty acids induce pro-inflammatory responses and endothelial cell dysfunction. Br J Nutr. 2008;99(4):723–31.. doi: 10.1017/s0007114507842772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Jauregibeitia I, Portune K, Gaztambide S, Rica I, Tueros I, Velasco O, Grau G, Martín A, Castaño L, Larocca AVet al. . Molecular differences based on erythrocyte fatty acid profile to personalize dietary strategies between adults and children with obesity. Metabolites. 2021;11(1):43. doi: 10.3390/metabo11010043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Frühbeck G, Catalán V, Rodríguez A, Gómez-Ambrosi J. Adiponectin-leptin ratio: a promising index to estimate adipose tissue dysfunction. Relation with obesity-associated cardiometabolic risk. Adipocyte. 2018;7(1):57–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Stern JH, Rutkowski JM, Scherer PE. Adiponectin, leptin, and fatty acids in the maintenance of metabolic homeostasis through adipose tissue crosstalk. Cell Metab. 2016;23(5):770–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Koenen M, Hill MA, Cohen P, Sowers JR. Obesity, adipose tissue and vascular dysfunction. Circ Res. 2021;128(7):951–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Kretsch MJ, Fong AK, Green MW. Behavioral and body size correlates of energy intake underreporting by obese and normal-weight women. J Am Diet Assoc. 1999;99(3):300–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Mertz W, Tsui JC, Judd JT, Reiser S, Hallfrisch J, Morris ER, Steele PD, Lashley E. What are people really eating? The relation between energy intake derived from estimated diet records and intake determined to maintain body weight. Am J Clin Nutr. 1991;54(2):291–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data described in the manuscript, code book, and analytic code will be made available upon request. Data sharing will require a signed agreement that addresses expenses for data transfer and protects participant confidentiality by exchanging de-identified data in protected formats.