Abstract

A total of 80 Candida isolates representing 14 species were examined for their respective responses to an in vitro hemolytic test. A modification of a previously described plate assay system where the yeasts are incubated on glucose (3%)-enriched sheep blood agar in a carbon dioxide (5%)-rich environment for 48 h was used to evaluate the hemolytic activity. A group of eight Candida species which included Candida albicans (15 isolates), C. dubliniensis (2), C. kefyr (2), C. krusei (4), C. zeylanoides (1), C. glabrata (34), C. tropicalis (5), and C. lusitaniae (2) demonstrated both alpha and beta hemolysis at 48 h postinoculation. Only alpha hemolysis was detectable in four Candida species, viz., C. famata (3), C. guilliermondii (4), C. rugosa (1), and C. utilis (1), while C. parapsilosis (5) and C. pelliculosa (1) failed to demonstrate any hemolytic activity after incubation for 48 h or longer. This is the first study to demonstrate the variable expression profiles of hemolysins by different Candida species.

Candida species have the ability to produce a variety of hydrolytic enzymes, such as proteases, lipases, phospholipases, esterases, and phosphatases (4, 11, 13). These enzymes have received much attention in the past, as they are known to mediate candidal pathogenesis, particularly by facilitating the hyphal invasion especially seen in disseminated candidiasis (6). While there have been a number of detailed studies on some of these hydrolytic enzymes, such as proteases, lipases, and phospholipases (8, 9, 14), little is known of the hemolytic activity exhibited by different Candida species. Recently, Manns et al. (10) described an elegant yet simple plate assay method for observing the hemolytic activity of Candida albicans. We have modified this method to evaluate the hemolytic activity of different Candida species obtained from a variety of clinical sources and to compare qualitatively and quantitatively the species-specific differences in hemolysin production.

A total of 80 Candida isolates representing 14 different Candida species obtained from clinical sources in different geographic locales were selected from strains deposited at the Candida Culture Collection of the Oral Bio-Sciences Laboratory, Faculty of Dentistry, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong (Table 1). For global comparison of data, a single reference laboratory strain each of C. albicans ATCC 90028, C. glabrata ATCC 2001, and C. parapsilosis ATCC 22019 (American Type Culture Collection, Rockville, Md.) were also included. The identity of all organisms was reconfirmed by the germ tube test, and the commercially available API 20C Aux identification kit (Analytical Profile Index; BioMerieux SA, Marcy l'Etoile, France) (13). Stock cultures were maintained at −40°C. After recovery these were maintained on Sabouraud dextrose agar (Oxoid Ltd, Basingstoke, Hampshire, England, United Kingdom) and stored at 4 to 6°C during the experimental period. Purity of cultures was ensured by regular random identification of isolates by techniques described above. In addition to the yeast strains, one strain each of Streptococcus pyogenes (Lancefield group A) and Streptococcus sanguis, which induce beta and alpha hemolysis, respectively, were used as positive controls.

TABLE 1.

Hemolytic activity of 14 different Candida species isolated from human sourcesa

| Species | No. of isolates tested | No. of isolates with hemolysin pattern (hemolysis index,a mean ± SD); groupb

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alpha | Beta | Gamma (none) | ||

| C. albicans | 15 | 15 (1.718 ± 0.164); A | ||

| C. glabrata | 34 | 34 (1.376 ± 0.052); B | ||

| C. dubliniensis | 2 | 2 (1.695 ± 0.077); A | ||

| C. kefyr | 2 | 2 (1.705 ± 0.120); A | ||

| C. lusitaniae | 2 | 2 (1.285 ± 0.163); B | ||

| C. krusei | 4 | 4 (1.243 ± 0.126); B | ||

| C. tropicalis | 5 | 5 (1.654 ± 0.094); A | ||

| C. zeylanoides | 1 | 1 (2.237) | ||

| C. famata | 3 | 3 | ||

| C. guilliermondii | 4 | 4 | ||

| C. rugosa | 1 | 1 | ||

| C. utilis | 1 | 1 | ||

| C. parapsilosis | 5 | 5 | ||

| C. pelliculosa | 1 | 1 | ||

Hemolysis index: the diameter of the translucent radial zone of hemolysis divided by the diameter of the colony size.

Group A vs. group B: P < 0.05; statistics not performed for the single isolate of C. zeylanoides; alpha hemolysis could not be quantified.

Hemolysin production was evaluated using a modification of the plate assay described by Manns et al. (10). In brief, the isolates were recovered from distilled water stored at −40°C. A loopful of the stock culture was streaked onto Sabouraud dextrose agar and incubated at 37°C for 18 h. The resultant cultures were harvested and washed with sterile saline, and a yeast suspension with an inoculum size of 108 cells/ml was prepared using hemocytometric counts (12). Ten microliters of this suspension was spot inoculated on a sugar-enriched sheep blood agar medium so as to yield a circular inoculation site of about 5 mm in diameter. The latter medium was prepared by adding 7 ml of fresh sheep blood (Hemostat, Dixon, Calif.) to 100 ml of Sabouraud dextrose agar supplemented with 3% glucose (final concentration, wt/vol; Merck, Darmstadt, Germany). The final pH of the medium so prepared was 5.6 ± 0.2. The plates were incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 48 h. The presence of a distinct translucent halo around the inoculum site, viewed with transmitted light, indicated positive hemolytic activity. The diameters of the zones of lysis and the colony were measured with the aid of a computerized image analysis system (Quantimet 500 Qwin; Leica, Cambridge, United Kingdom) (18), and this ratio (equal to or larger than 1) was used as a hemolytic index to represent the intensity of the hemolysin production by different Candida species. The assay was conducted in quadruplicate on two separate occasions for each yeast isolate tested.

An additional experiment was performed to determine the effect of the glucose supplement on the hemolysin production by incubating a total of 12 hemolysin-positive yeasts in glucose-free blood agar medium.

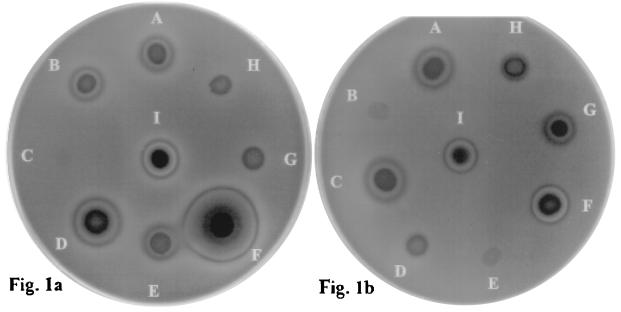

At 48 h postinoculation, two different types of hemolysis could be observed circumscribing the yeast “colony” when viewed with transmitted light (Fig. 1). The first was a totally translucent ring identical to beta hemolysis produced by the control strain of beta-hemolytic S. pyogenes, and the second was a greenish-black halo comparable to alpha-hemolysis observed with the control strain of S. sanguis. Hence, the terms alpha hemolysis and beta hemolysis were used as descriptive terms to indicate incomplete and complete hemolysis, respectively, associated with the Candida strains tested.

FIG. 1.

Photographs depicting the hemolysis of sheep blood agar (supplemented with 3% glucose) induced by 14 different Candida species. Panel a shows C. albicans (A), C. glabrata (B), C. parapsilosis (C), C. tropicalis (D), C. lusitaniae (E), C. zeylanoides (F), C. guilliermondii (G), and C. famata (H). Panel b shows C. kefyr (A), C. pelliculosa (B), C. dubliniensis (C), C. utilis (D), C. parapsilosis (E), C. albicans (F), C. krusei (G), and C. rugosa (H). A reference strain of C. albicans (ATCC90028) served as a positive control (I).

At 24 h postinoculation, only alpha hemolysis was observed surrounding the inoculum sites with all strains of the Candida spp. C. albicans, C. dubliniensis, C. kefyr, C. krusei, C. zeylanoides, C. glabrata, C. tropicalis, and C. lusitaniae. However, after further incubation for 48 h the zone of hemolysis enlarged and showed dual zones, i.e., an internal zone of beta hemolysis surrounded by a peripheral zone of alpha hemolysis (Fig. 1).

A total of nine Candida isolates belonging to C. famata, C. guilliermondii, C. rugosa, and C. utilis exhibited only a zone of alpha hemolysis despite prolonged inoculation (i.e., 72 h). On the contrary, all tested isolates of C. parapsilosis and a single isolate of C. peliculosa exhibited neither alpha nor beta hemolysis despite 72 h of incubation (Table 1).

As opposed to the hemolytic patterns described above for glucose-supplemented media, in experiments with glucose-free sheep blood agar, all tested strains except those of C. parapsilosis and C. pelliculosa exhibited only alpha hemolysis. The last two species produced neither alpha nor beta hemolysis.

In order to obtain quantitative data we attempted to measure the diameters of hemolytic zones relative to the inoculum size using an image analysis system. However, clear-cut zones were perceptible only in relation to beta-hemolytic activity. The margins of alpha hemolysis were rather diffuse, and hence the diameters of the latter zones were not accurately quantifiable by either naked eye estimation or the image analysis system.

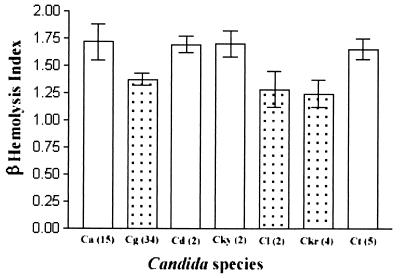

The quantitative data indicated that the beta-hemolytic activities of C. albicans, C. dubliniensis, C. kefyr, and C. tropicalis were significantly higher than those of C. glabrata, C. krusei, and C. lusitaniae (P < 0.05) (Fig. 2 and Table 1). Although C. zeylanoides showed a much higher beta-hemolytic activity than all other tested species, this result was equivocal as only a single strain was examined (Table 1). Further, there was no significant intraspecies differences in the beta-hemolytic activity among isolates belonging to C. albicans and C. glabrata. Similar statistics could not be performed for the remaining species due to the small number of isolates tested in each species.

FIG. 2.

Histogram depicting the beta-hemolytic activity of seven different Candida species (the diameter of the translucent radial zone of hemolysis divided by the diameter of the colony size). C. albicans (Ca), C. dubliniensis (Cd), C. kefyr (Cky), and C. tropicalis (Ct) exhibited a significantly higher beta-hemolytic activity than C. glabrata (Cg), C. lusitaniae (Cl), and C. krusei (Ckr) (P < 0.05); bar represents ± 1 standard deviation. The number of strains in each species is indicated in parenthesis. (A beta hemolysis positive species, C. zeylanoides, is not shown here since only a single strain of this species was investigated.)

The ability of pathogenic organisms to acquire elemental iron has been shown to be of pivotal importance in their survival and ability to establish infection within the mammalian host (3, 17). Since there is essentially no free iron in the human host, most pathogens acquire this indirectly from commonly available iron-containing compounds such as hemoglobin (2). In order to do so, however, the pathogen should be equipped with a mechanism that destroys the heme moiety and enables it to extract the elemental iron. The enzymes mediating such activity are broadly classified as hemolysins.

A complement-mediated hemolysis induced by C. albicans was reported by Manns et al. in 1994 (10), but a perusal of the literature revealed no other reports on the hemolytic activity of non-albicans species of Candida. In the present study, we conclusively demonstrate, both qualitatively and quantitatively the hemolytic activity in a wide spectrum of Candida species belonging to 14 genera. The hemolysis so induced could be categorized according to the conventional microbiologic nomenclature as either complete (beta), incomplete (alpha), or no hemolysis (gamma). Thus the terms alpha and beta hemolysis used here to describe the different patterns of hemolysis in Candida species can only be regarded as descriptive, since the exact nature of these variants and the underlying mechanisms are yet to be explored in full.

Of the tested Candida species, C. albicans, C. dubliniensis, C. kefyr, C. krusei, C. zeylanoides, C. glabrata, C. tropicalis, and C. lusitaniae demonstrated both alpha and beta hemolysis. However, beta-hemolytic activity in these species was seen only after 48 h followed by alpha hemolysis on 24 h of incubation, whereas C. famata, C. guilliermondii, C. rugosa, and C. utilis demonstrated only alpha-hemolytic activity despite prolonged inoculation. These observations appear to suggest that alpha- and beta-hemolytic activity may be a result of two or more different hemolytic factors sequentially produced by the yeasts. Thus, it is tempting to hypothesize that the erythrocytes are destroyed by a two-stage mechanism. First would be a partial destruction due to an alpha-hemolytic factor(s) generated by the relatively young colonies of Candida. Thus, the metabolic end products of the first stage may serve as a catalyst to induce the secretion of a secondary hemolytic factor(s), beta hemolysin, leading to complete destruction of hemoglobin. This hypothesis accommodates our observations related to both the alpha- and beta-hemolytic species of Candida, since some species may be devoid of an enzymatic pathway necessary to accomplish complete hemolytic activity.

The nature of the alpha-hemolytic factor(s) in microorganisms is poorly understood. Hemolysins are known to be key virulence factors contributing to the pathogenesis of common bacterial infections due to staphylococci and streptococci. In a recent study, Barnard and Stinson (1) demonstrated that the alpha-hemolytic factor in Streptococcus gordonii is hydrogen peroxide. Although C. albicans is capable of generating hydrogen peroxide (5), it is unclear whether the latter is responsible for alpha hemolysis observed in the present study. Further studies are needed to determine whether hydrogen peroxide can also be produced by non-albicans Candida species which exhibited alpha hemolysis and to examine the possible relationship, if any, between these two parameters.

Although Manns et al. (10) described a translucent complete hemolytic ring induced by C. albicans, identical to the beta hemolysis observed by us, yet again there is no biochemical information on the beta-hemolytic factors released by Candida species. It may be questioned whether the hemolytic activity observed is true hemolysis or is a product of extracellular phospholipases of Candida species. This is unlikely to be the case, since only 26.4% of the 34 C. glabrata isolates used in the present study were phospholipase positive when tested by an in vitro egg yolk agar assay (unpublished data). Watanabe et al. (15) have proposed that the beta hemolysin in C. albicans is probably a cell wall mannoprotein. However, our observations cast doubt on this hypothesis, since 6 of 14 Candida species we tested were unable to produce beta hemolysis, although mannoprotein is a universal component of the Candida cell wall. One possible explanation for these disparate observations is likely to be the variation in the cell wall mannoprotein content among different Candida species. Furthermore, when the hemolytic assay was performed using a glucose-free medium, only alpha hemolysis was observed with the previously beta-hemolytic Candida species. Thus, it appears that the absence of glucose in the medium may have altered the sugar moiety of the mannoprotein in some manner leading to the loss of beta-hemolytic activity.

Although we have compared quantitatively the relative zone sizes of beta hemolysis among Candida species and the data showed that C. albicans, C. dubliniensis, C. kefyr, and C. tropicalis exhibited significantly higher beta-hemolytic activities than other species, it should be borne in mind that there may exist species-specific hemolysins that may vary in their molecular size and thus affect the diffusion rate. Further studies are warranted to evaluate these molecular differences, if any, in Candida hemolysins.

C. albicans is a dimorphic yeast and exists in both the hyphal and the blastoconidial phases, depending on the growth medium and conditions. Previous workers have reported that hemolysin is produced by C. albicans only when it is in the hyphal form and not in the blastoconidial form (16). We doubt whether the hyphal form is a prerequisite for hemolysin production, since both alpha and beta hemolysis were observed with all strains of C. glabrata, considered a hyphae-negative species (7).

The modified plate assay described in the present report is simple, reproducible, and sensitive and is a relatively fast screening method for assessing the hemolytic activity of Candida species. In clinical terms, it could be of interest to evaluate the relationship between the virulence and the degree of hemolysin production among pathogenic and commensal isolates of Candida using this method. Such studies are in progress in our laboratories.

To conclude, the findings reported here for the first time indicate that many Candida species exhibit various abilities to produce one or more types of hemolysins, the nature of which is ill understood at present. Of the common pathogenic species, C. albicans and C. dubliniensis appear to be the most prolific producers of hemolysins, in keeping with the foremost position they occupy in the hierarchy of virulence amongst Candida species. Further studies are urgently needed to investigate the nature of the hemolytic factors secreted by Candida, their utility in diagnostic terms and, last but not the least, their putative effects in the human host.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Research Grants Council (RGC) of Hong Kong and the Committee for Research and Conference Grants (CRCG), of the University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong.

We thank A. Ellepola, S. Anil, R. Dassanayake, and G. Tang for their valuable discussions and Becky Cheung for her excellent technical support.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barnard J P, Stinson M W. The alpha-hemolysin of Streptococcus gordonii is hydrogen peroxide. Infect Immun. 1996;64:3853–3857. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.9.3853-3857.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Belanger M, Begin C, Jacques M. Lipopolysaccharides of Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae bind pig hemoglobin. Infect Immun. 1995;63:656–662. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.2.656-662.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bullen J J. The significance of iron in infection. Rev Infect Dis. 1981;3:1127–1138. doi: 10.1093/clinids/3.6.1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cutler J E. Putative virulence factors of Candida albicans. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1991;45:187–218. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.45.100191.001155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Danley D L, Hilger A E, Winkel C A. Generation of hydrogen peroxide by Candida albicans and influence on murine polymorphonuclear leukocyte activity. Infect Immun. 1983;40:97–102. doi: 10.1128/iai.40.1.97-102.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fallon K, Bausch K, Noonan J, Huguenel E, Tamburini P. Role of aspartic proteases in disseminated Candida albicans infection in mice. Infect Immun. 1997;65:551–556. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.2.551-556.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fidel P L, Jr, Vazquez J A, Sobel J D. Candida glabrata: review of epidemiology, pathogenesis, and clinical disease with comparison to C. albicans. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1999;12:80–96. doi: 10.1128/cmr.12.1.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hube B, Turver C J, Odds F C, Eiffert H, Boulnois G J, Kochel H, Ruchel R. Identification, cloning and characterization of the gene for the secretory aspartate protease of Candida albicans. Mycoses. 1991;34(Suppl. 1):59–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee G C, Tang S J, Sun K H, Shaw J F. Analysis of the gene family encoding lipases in Candida rugosa by competitive reverse transcription-PCR. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:3888–3895. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.9.3888-3895.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Manns J M, Mosser D M, Buckley H R. Production of a hemolytic factor by Candida albicans. Infect Immun. 1994;62:5154–5156. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.11.5154-5156.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Odds F C. Candida and candidosis: a review and bibliography. 2nd ed. London, United Kingdom: Bailliere Tindall; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Samaranayake L P, MacFarlane T W. The adhesion of the yeast Candida albicans to epithelial cells of human origin in vitro. Arch Oral Biol. 1981;26:815–820. doi: 10.1016/0003-9969(81)90178-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Samaranayake L P, MacFarlane T W. Oral candidosis. Bristol, United Kindom: Wright; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Takahashi M, Banno Y, Nozawa Y. Secreted Candida albicans phospholipases: purification and characterization of two forms of lysophospholipase-transacylase. J Med Vet Mycol. 1991;29:193–204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Watanabe T, Takano M, Murakami M, Tanaka H, Matsuhisa A, Nakao N, Mikami T, Suzuki M, Matsumoto T. Characterization of a haemolytic factor from Candida albicans. Microbiology. 1999;145:689–694. doi: 10.1099/13500872-145-3-689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Watanabe T, Takano M, Murakami M, Tanaka H, Matsuhisa A, Nakao N, Mikami T, Suzuki M, Matsumoto T. Hemoglobin is utilized by Candida albicans in the hyphal form but not yeast form. Biochem Biophys Res Commun: 1997;232:350–353. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.6247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weinberg E D. Iron and infection. Microbiol Rev. 1978;42:45–66. doi: 10.1128/mr.42.1.45-66.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu T, Samaranayake L P, Cao B Y, Wang J. In-vitro proteinase production by oral Candida albicans isolates from individuals with and without HIV infection and its attenuation by antimycotic agents. J Med Microbiol. 1996;44:311–316. doi: 10.1099/00222615-44-4-311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]