Abstract

Background and Objectives

This review investigates the contribution of discursive approaches to the study of ageism in working life. It looks back on the 50 years of research on ageism and the body of research produced by the discursive turn in social science and gerontology.

Research Design and Methods

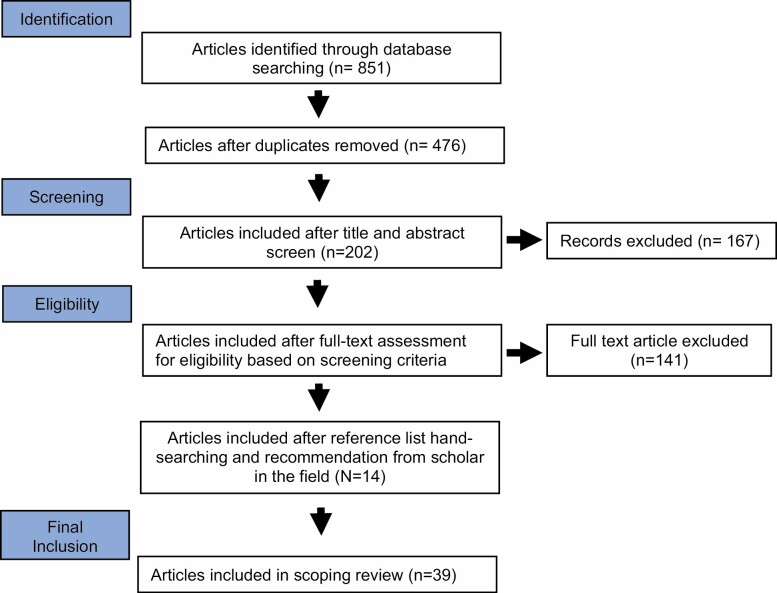

This study followed the 5-step scoping review protocol to define gaps in the knowledge on ageism in working life from a discursive perspective. About 851 papers were extracted from electronic databases and, according to inclusion and exclusion criteria, 39 papers were included in the final review.

Results

The selected articles were based on discursive approaches and included study participants along the full continuum of working life (workers, retirees, jobseekers, and students in training). Three main themes representing the focal point of research were identified, namely, experiences of ageism, social construction of age and ageism, and strategies to tackle (dilute) ageism.

Discussion and Implications

Discursive research provides undeniable insights into how participants experience ageism in working life, how ageism is constructed, and how workers create context-based strategies to counteract age stereotypes, prejudice, and discrimination. Discursive research on ageism in the working life needs further development about the variety of methods and data, the problematization of age-based labeling and grouping of workers, and a focus on the intersection between age and other social categories. Further research in these areas can deepen our understanding of how age and ageism are constructed and can inform policies about ways of disentangling them in working life.

Keywords: Aging policies, Discourses, Older–younger workers, Workforce

Background

This scoping review explores the contribution of discursive approaches to the analysis of ageism in working life. Robert N. Butler coined the concept of ageism in 1969, defining it as “prejudice by one age group towards other age groups” (Butler, 1969, p. 243). Fifty years later, ageism has gained primary importance in the field of gerontology, as well as in work-life studies (de Medeiros, 2019). Currently, ageism still goes unchallenged, compared to other forms of discrimination, and is socially accepted, both at explicit and implicit levels (Levy, 2017).

Ageism, as a concept, has expanded and a common agreement exists today that ageism is (a) directed toward all ages; (b) composed of affective, cognitive, and behavioral components, which can be distinguished between personal, institutional, and societal levels; and (c) either positive or negative (Palmore, 2015). The phenomenon has raised major attention in policy organizations, and in 2016, the World Health Organization (WHO, 2018, p. 295) instituted a campaign to fight ageism, defining it as “the stereotyping, prejudice and discrimination towards people on the basis of age.” Previous research shows that negative age attitudes influence individual daily life, for example, lowering the possibilities for social integration (Vitman et al., 2014). Ageism also affects national economies: it might cause an estimated loss of 63 billion USD per year to the U.S. health system (Levy et al., 2020). The cost of ageism is computable also for employers and employees and it was estimated that, in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development countries, the Gross Domestic Product would increase 3.5 trillion USD if the employment of persons aged older than 55 would increase (United Nations Economic Commission for Europe [UNECE], 2019).

Discursive Approaches to Ageism in Working Life

Over the past 50 years of research, the scientific literature on ageism has shifted in emphasis and approaches adopted. In the 1980s and early 1990s, the qualitative turn in social gerontology (Gubrium, 1992), rise of critical gerontology, and discursive turn in social science (Potter & Wetherell, 1987) contributed to the creation of a new corpus of research. On the one hand, the rise of critical approaches in gerontology challenged the mainstream practices of research and questioned the normative conceptualizations of the life course; the intersection of age, gender, and ethnicity; and the overreliance on quantitative analysis. On the other hand, the discursive turn encouraged social scientists to examine the role of language in the construction of social reality (Willig, 2003). Within this framework, discursive approach is an “umbrella term” that includes an extensive diversity of methods to analyze text and talk (Nikander, 2008). These approaches are often divided into macro and micro. Whereas macro approaches are interested in power relations and focus on the implications of discourses for subjective experiences (Willig, 2003), micro approaches examine how people use language in everyday life, not to “mirror” reality but to accomplish things (Potter & Wetherell, 1987). In this article, our focus is on both micro and macro approaches, as long as the study design reflects the understanding that the use of language, whether text or talk, plays an active part in the construction of reality. In the past few decades, the much broader, theoretically grounded qualitative turn in gerontology was rapidly followed by the diversification of strategies within the qualitative inquiry, discursive gerontology framing one such tradition. Not all discursive research is qualitative by nature and not all qualitative research is discursive by nature, quantitative data sets can also be used within this tradition. Mere focus on text and talk does not make a study discursive. The purpose of the discursive inquiry is firmly grounded in the theoretical assumption that language does not reflect reality but rather constructs it and is part and parcel of all meaning making in social interactions.

In aging research, there is a growing body of literature interested in the relational and discursive nature of ageism in the context of working life (Spedale, 2019). These types of approaches have received scant attention and still need formal recognition, especially compared with research that uses age as a mere chronological and background variable (Taylor et al., 2016).

Literature Reviews

Wide-ranging reviews have been published on ageism. Most of them are centered on variables and quantitative methods. Although some of these reviews have included qualitative studies, to the best of our knowledge, no review exists with a specific focus on discursive approaches in the field of ageism and working life. Summarizing the previous literature, Levy and Macdonald (2016) published an extensive review on ageism, while Nelson (2016) focused on ageism in health care and the workplace. Harris et al. (2018) analyzed stereotypes, prejudices, and discriminative behaviors associated with older workers. Regarding older workers’ retention, reviews exist on age diversity and team outcomes (Schneid et al., 2016); the ability, motivation, and opportunity to continue working (Pak et al., 2019); workplace interventions (Truxillo et al., 2015); and workplace health promotion for older workers (Poscia et al., 2016).

These studies demonstrate that ageism is present in the workforce, produces barriers in recruitment, career advancement, training opportunities, retirement decision, and in the relations between managers, or employers, and employees (Harris et al., 2018). Although the focus of research in this area is primarily on older workers, age discrimination is experienced along all life stages and is especially reported by employees younger than 35 and older than 55 years old (UNECE, 2019). Older workers have gained the most attention, as this age group is a policy target for the national goal of prolonging working life. In this context, ageism may hinder wide-ranging policy efforts by guiding the perception of specific age groups as problematic.

Objective

Looking back at 50 years of research since the term ageism was introduced, and focusing on the growing interest in ageism as a relational and discursive phenomenon, the aim of this review is to highlight the contribution of discursive studies and to discuss potential gaps in knowledge and directions for future research in the field of ageism and working life. The review focuses on work-related studies, as discursive approaches have been previously utilized in this area and they have proven able to problematize open questions, such as the social construction of older workers as a group, the hidden ideologies in the labor market, and the strategies that workers use in everyday lives to counteract ageism.

Research Design and Methods

This scoping review follows Arksey and O’Malley’s (2005) protocol (see Supplemetary Material for Prisma Checklist). This typology was chosen because it allows for the investigation of gaps in knowledge in a field of research that is not clearly established. The review strictly follows the five-step framework, which comprises the following: (a) defining the study purpose, (b) study identification, (c) screening process, (d) data extraction, and (e) summarizing the retrieved data. After the completion of the screening process, a qualitative thematic analysis (Levac et al., 2010) of the selected paper was carried out to examine ways in which overarching topics were conceptualized. This review follows an established protocol and discussions regarding review methodology are beyond the scope of the study.

Step 1: Study Purpose

The guiding research question was: What are the contributions of discursive approaches to the literature on ageism in the working life, since the coinage of the term in 1969, and what insights are provided by different types of discursive approaches? Through this work, we acknowledge the ability of this approach to enhance our understanding of participants’ experience, meaning making, and negotiation strategies regarding age stereotypes in working life. Through a comprehensive synthesis, we show possible further directions for research and gaps in knowledge. According to the scoping review protocol, our research question was open and the process data driven. Moreover, the open issue of defining ageism (Palmore, 2015) led the reviewers to analyze which definitions are utilized by researchers.

Step 2: Study Identification

To identify the relevant papers for our review, terms related to ageism and discursive perspective were used to search seven electronic databases (PsycINFO, Web of Science, Social Science Premium Collection, Sage Journals, Wiley Journals, Academic Ultimate Search [EBSCO], and Scopus). The keywords used were as follows: (Ageism OR Agism OR Ageis* OR Agis*) AND (discours* OR communication* OR “social interaction*” OR narrative*). The search string linked to the discursive approach was intended to capture types of discourses and not to retrieve specific methodology and/or methods at this stage. The decision of using only “ageism” as a search term, and not its synonyms, was made to retrieve only papers that clearly contribute to the knowledge around this specific concept and not related phenomena, such as social exclusion or age discrimination. Moreover, no search terms were defined regarding “working life,” but this was used as an inclusion criterion in the next step to ensure that no relevant paper was missed. Likewise, no limitation was defined regarding the participants’ age, hence the review does not focus solely on older workers but addresses ageism across all stages of working life.

The databases were selected with the help of an information specialist as relevant for contributions in the field of Social Sciences. The search was carried out in March 2019. A record of all the results in each database was kept allowing the reproduction of the review strategy. During the process, the reviewers consulted senior experts and information specialists to optimize the quality of the search method.

Step 3: Screening Process

First, an agreement on the general inclusion and exclusion criteria was reached by the reviewers (Table 1). This helped define the relevant studies for the first step of the screening based on titles and abstracts. Contributions were included if they were published in English in peer-reviewed, international journals and available electronically in full text. The papers chosen focused on working life, including all types of transitions—from study to work, work to retirement, work to unemployment, unemployment to reeducation, and unemployment to employment/self-employment. All work settings were accepted and papers were included in case they analyzed work-related experiences, practices, and contexts. Therefore, health care settings were also included as one type of workplace where ageism unfolds, along with companies, job centers, recruitment agencies, and educational environments. The review focuses on 50 years of research hence the time limit for publication year and data collection was set to 1969, the coinage year of the term ageism (Butler, 1969). Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed-method papers on the text and spoken communication were included if they demonstrated the adoption of discursive study design and a discursive understanding of language.

Table 1.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

| Written in English | Review |

| Peer-reviewed articles | Intervention study |

| Discursive approach | Self-reflection/biography |

| Data source not older than 1969 | No focus on ageism |

| Papers published after 1969 | |

| Focus on working life |

However, the screening process quickly ran into problematic cases due to the variety of definitions of “discourse” and “discursive approach.” For example, some authors consider the methodology of interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA) part of discursive approaches (McKinlay & McVittie, 2009) because it is utilized to study not only subjective experiences but also the construction of shared meanings and social reality (Smith, 1996; Starks & Trinidad, 2007). Hence, to make the review inclusive rather than exclusive, studies that represented IPA were accepted.

An objective screening was used, as shown in Figure 1: Retrieved papers were screened separately by two reviewers, while the third one resolved conflict when an agreement was not reached. First, the reviewers screened papers by the title and abstract: of 851 papers, 202 passed this step. Second, the reviewers screened the full texts, and a resulting 25 papers were selected. Third, an independent screening process of the references was conducted from the final group of selected papers. The reference lists of the retrieved papers were screened to ensure that all papers of interest were included. Fourth, senior scholars were consulted for recommendations on missing papers. After the third and fourth steps, 14 papers were added. The papers added through hand-screening of references suggest that, within gerontology, discursive approaches are used by a rather small-scale group of authors who tend to cross-reference each other. The addition of papers from experts demonstrates the challenge to pinpoint discursive studies within literature databases via electronic search. Given that defining discourses has proven problematic in the empirical and theoretical literature within the discursive tradition, the same problem is reflected by challenges in the review process at hand. We trust, however, that the final steps taken as an integral part of the scoping review protocol endure its comprehensiveness.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the screening process.

Finally, 39 articles were included. Discussions were held throughout the process to ensure a common understanding, and senior scholars were involved to examine complex scenarios. The reviewers used Covidence (www.covidence.org) as software to facilitate the screening process.

Step 4: Data Extraction

A template was defined through which data were extracted from selected papers. A descriptive-analytic method was chosen to report and collect standard information of the selected studies. The data were charted through the Excel database program, including the following attributes: authors, year of publication, study location, study population, aim of the study, research design, and main results. Per the protocol, a trial extraction was conducted by all reviewers on three randomly selected papers. This procedure ensures the clarity of the template and a common understanding of the categories. Then, the contributions were evenly divided among the reviewers, and each extracted data independently. Once the procedure was complete, reviewers compared results and discussed incongruences.

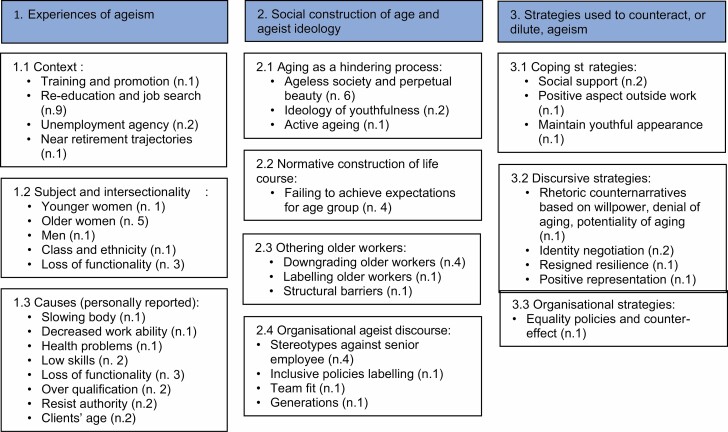

Step 5: Collocation, Summarizing, and Synthesis

Once the final group of papers was defined, a qualitative thematic analysis of the paper was performed, according to the scoping review protocol (Levac et al., 2010). Here, the analysis employed a data-driven approach to answer the research questions presented, similar to other published scoping reviews (Grenier et al., 2019; Harris et al., 2018). The aim of the present review is to highlight and discuss the contribution of discursive studies to ageism in working life, to highlight the main contents, and to demonstrate the gaps in the knowledge, with no interest in comparing evidence and results. Therefore, papers were not submitted to quality evaluation. The researchers used an iterative approach to perform the analysis. Each of them reviewed one third of the papers and developed categories and themes. The themes were presented and discussed, then presented to a senior expert, after which divergences were debated and final themes defined (Figure 2). Once the reviewers reached an agreement, they reviewed together all the papers to assure the representativeness of the themes. As given in Table 2, papers can include more than one theme. The thematic analysis was the foundation for suggesting gaps in the knowledge, implications, and future lines of research. This method aligns with the qualitative thematic analysis proposed by the protocol (Levac et al., 2010).

Figure 2.

Description of themes.

Table 2.

Descriptive Characteristics of Included Studies (N = 39)

| Research design | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First author (year), country | Setting and participants (age, if reported) | Method of generating data | Approach/method of analysis | Themes |

| Allen (2006), the United States | Headquarters of a U.S. manufacturing company; 39 (all women) IT employees, 30 to older than 40 years | Focus group | Descriptive approach and revealed causal mapping (RCM) | 1 |

| Ben-Harush (2017), Israel | Health care setting; 20 physicians, 5 nurses, 4 social workers | Focus group | Thematic analysis | |

| Berger (2006), Canada | Employment office; 30 unemployed individuals actively searching for jobs; 45–65 years old | Semi-structured interviews | Symbolic interactionist perspective | 1, 2, and 3 |

| Billings (2006), the United Kingdom | Health care setting; 57 staff members and volunteers been working with older people for at least 3 months | Focus group | Thematic analysis | 1 |

| Bowman (2017), Australia | 80 unemployed or underemployed people with different occupations (blue and white collar), 45–73 years old | Interviews | Narrative approach | 1 |

| Brodmerkel (2019), Australia | Creative advertising agencies, 32 workers, 32–53 years old | In-depth interviews | Discursive approach | 1, 2, and 3 |

| Crăciun (2018), Germany | 23 unemployed Russian and Turkish immigrants, 40–62 years old | Episodic interviews | Thematic analysis | 1 |

| Dixon (2012), the United States | 60 workers with different occupations, 19–65 years old | Active interviews | Hermeneutic phenomenology and thematic analysis | 2 |

| Faure (2015), France | 140 recruiters, mean 41 years old | Mixed method, written statements about job applicants | Discursive psychology | 2 |

| George (1998), the United Kingdom | Educational setting; 11 women training to be teachers, 33–50 years old | Interviews | Thematic analysis | 1 |

| Gould (2015), Canada | Educational setting; 20 nursing students (third year) | Focus group | Thematic analysis | 2 |

| Granleese (2006), the United Kingdom | Academia; 48 academics aged younger than 30 to older than 50 years | In-depth interviews | Content and interpretative phenomenological analysis | 1 |

| Grima (2011), France | Several sites of the same company in the field of production of studies; 12 managers and 40 employees, older than 45 years | Biographical narrative interviews | Case study on organizations and descriptive analysis | 1 and 3 |

| Handy (2007), New Zealand | Recruitment agency; 12 unemployed women and 5 recruiters, 50–55 years old | Interviews | Feminist studies and thematic analysis | 1 and 2 |

| Herdman (2002), Hong Kong, China | Health care setting; 96 nursing students, 19–22 years; 9 professional nurses, 24–36 years old | Mixed method, interviews | Content analysis and discourse analysis | 3 |

| Higashi (2012), the United States | Health care setting; 10 teams of physicians-in-training | Semi-structured interviews, group discussion, participant observation, and auto-ethnography | Narrative analysis | 1 and 2 |

| Kanagasabai (2016), India | Print media and TV company; 17 (all women) journalists in their 20s, 30s, and 40s | Interviews | Feminist studies and descriptive approach | 1 |

| Klein (2010), Canada | Health care settings; 16 occupational therapists, 2–28 years of work experience | Focused written questions and semi-structured interviews | Thematic analysis and constant comparative analysis | 1 |

| Laliberte-Rudman (2009), Canada | 72 newspaper articles on work and retirement | Textual material | Critical discourse analysis | 2 |

| (Laliberte-Rudman 2015a), Canada | 30 workers and retirees, 45–83 years old | Interviews | Narrative analysis | 2 |

| Laliberte-Rudman (2015b), Canada | 17 retirees, mean age 58.6 years | Two-step narrative interviews | Critical narrative analysis | 1 and 3 |

| Maguire (1995), the United Kingdom | Educational setting; 7 older women working in education | Unstructured interviews (5) and written accounts (2) | Descriptive approach | 1 |

| Maguire (2001), the United Kingdom | Educational setting; 7 women teachers, 49–65 years old | Biographical narrative, in-depth interviews | Descriptive approach | 1 |

| McMullin (2001), Canada | Garment industry; 79 individuals, retired, displaced and employed workers, age not defined | Focus group | Thematic and categories analysis | 1 |

| McVittie (2003), the United Kingdom | 12 human resources managers or recruitment managers of 23 medium to large enterprises operating on a U.K.-wide basis, in their 20s–50s | Semi-structured interviews | Discourse analysis | 2 |

| McVittie (2008), the United Kingdom | Employment office; 15 unemployed or nonemployed people, aged older than 40 years | Interviews | Discursive psychology | 1 and 2 |

| Moore (2009), the United Kingdom | 33 workers (all women) or unemployed, older than 50 years | Interviews | Intersectional and narrative approach | 1 |

| Niemistö (2016), Finland | 9 Finnish companies in growth sectors; 53 workers at different levels | Survey and interviews, qualitative fieldwork | Case studies, discursive approach | 2 |

| Noonan (2005), the United States | 37 workers or actively seeking jobs; 56–77 years old | Interviews | Thematic content analysis | 1 |

| Ojala (2016), Finland | 23 working-class men, 50–70 years old | Sequential thematic personal interviews | Discourse and membership categorization analysis | 2 |

| Phillipson (2019), the United Kingdom | Local government and train operating company; 82 participants, including human resources professionals, line managers, and older employees (aged 50 to older than 65 years) | Documentary evidence, focus group, semi-structured interviews | Case study approach, thematic analysis | 3 |

| Porcellato (2010), the United Kingdom | 56 economically active and inactive people, whether voluntarily or involuntarily, older than 50 years | Semi-structured interviews | Thematic analysis | 1 and 2 |

| Quintrell (2007), the United Kingdom | Educational setting; 30 teacher trainees, older than 35 years | In-depth and semi-structured interviews and questionnaire | Thematic analysis | 1 |

| Riach (2007), the United Kingdom | 8 articles and promotional texts of one company’s recruitment campaign | Textual material | Critical discourse analysis, interpretative repertoire analysis | 2 and 3 |

| Romaioli (2019), Italy | 78 economically active and inactive adults, 18–85 years old | Episodic interviews | Narrative and content analysis | 2 and 3 |

| Samra (2015), the United Kingdom | Health care setting; 25 medical students and doctors | In-depth and semi-structured interviews | Thematic analysis | 1 and 2 |

| Spedale (2014), the United Kingdom | Employment tribunal’s final judgment statement on age discrimination case | Textual material | Critical discourse analysis | 2 |

| Spedale (2019), the United Kingdom | 1 male teacher in late career life | Interview | Intersectional approach and deconstruction analysis | 2 |

| Yang (2012), South Korea | 34 workers (bridge workers) and nonworkers (permanent retirees), 50–70 years old | Semi-structured and in-depth interviews | Descriptive approach | 1 and 2 |

Results

Descriptive Summary

Thirty-six papers used a qualitative design, and three used mixed methods. The data sources were as follows: verbal communication (36) and textual material (3). In the articles using spoken communication, the most prevalent method of data collection was interviewing single participants (24 studies), while among the articles using textual material, one paper analyzed a collection of articles and promotional texts, one used newspaper articles, and one investigated a tribunal judgment report. Table 2 presents a description of the selected papers. Although we focused on discursive studies, there was a significant variation in the methods of analysis adopted in the papers. The methods of analysis ranged from descriptive content analysis and thematic analysis to detailed analysis of membership categorization.

Despite the time limit for publication was set to 1969 as an inclusion criterion, studies were published relatively recently: 15 of 39 studies were published after 2015, 7 in 2010–2015, 11 in 2005–2010, and the remaining 6 in 1995–2005. The publication dates are consistent with the discursive turn that happened in the early 1990s in social science and gerontology. Most of the studies were developed in Western world regions: Europe, 21 (of which 15 were in the United Kingdom); Canada, 7; the United States, 4; Australia, 2; Hong Kong, 1; India, 1; Israel, 1; New Zealand, 1; and South Korea, 1.

The organizational contexts vary from health settings, to private companies, to public job centers. The age of participants selected varied greatly (see details in Table 2). In 16 of 39 studies, participants were selected on the basis of age to represent the older workers’ group. Age thresholds varied greatly among these studies, with a range between 40 and 80 years old. The fact that most papers were not just about older workers is coherent with the definition of ageism (to be noted that all participants were older than 18 years). Nevertheless, the amount of papers interested in setting an age limit shows how the field is still primarily oriented toward older workers.

In the following sections, the main findings of the analysis are presented: first, an outline of how the term ageism is defined in the accepted papers is provided, followed by the results of the qualitative thematic analysis.

Definitions of Ageism

Definitions of ageism easily influence researchers’ perspective, which is especially important when dealing with discursive approaches, as reflecting the meaning-making process of social phenomena. The definitions presented in the papers are given in Table 3, warning that not all authors explicate it. Synthesizing the definitions of ageism also contributes to the open discussion on the phenomenon, which is still largely subject to disagreement.

Table 3.

Definition of Ageism

| Ageism (n. 6) | Prejudice of one age group towards another. |

| Tripartite ageism (n. 1) | Stereotypes, prejudice and discriminatory behaviors on the basis of age. |

| Gendered ageism (n. 9) | Age and gender are regarded as systems that interact to shape life situations in ways that often discriminate against women. |

| New ageism (n. 4) | Discursive strategy in policies that, while promoting inclusion of older people, tend to marginalize and categorize them. |

| New ageism (n. 1) | The shift from fear of aging toward fear of aging with disability, stressing the fear of functionality loss often associated with aging. |

| Social ageism (n. 1) | Systematic stereotyping leading to age discrimination. |

| Organizational ageism (n. 1) | A less visible form of gendered ageism that is linked with the different features of generations in the work context and management’s difficulties to acknowledge them. |

Note: 17 papers of 39 do not present a clear definition of ageism.

Butler’s (1969) original definition of ageism was cited in 6 of 39 papers (Bowman et al., 2017; Grima, 2011; Higashi et al., 2012; Laliberte-Rudman, 2015b; McMullin & Marshall, 2001; Ojala et al., 2016). However, even when the researchers did not specifically cite Butler, they often defined ageism as stereotypical beliefs and discriminating behavior based on age (Brodmerkel & Barker, 2019; Faure & Ndobo, 2015). The tripartite definition of ageism promoted by the WHO (2018), comprises “stereotypes, prejudice and discriminatory behaviors on the base of age,” was utilized only by Ben-Harush et al. (2017, p. 40).

Nine papers focused on gendered ageism (Granleese & Sayer, 2006; Handy & Davy, 2007; Kanagasabai, 2016; Maguire, 1995, 2001; Moore, 2009; Niemistö et al., 2016; Ojala et al., 2016; Spedale et al., 2014). This term was introduced to prevent the discursive dominance of ageism over sexism in the analysis of stereotypes toward women (Spedale et al., 2014). It is noteworthy that only one paper refers to gendered ageism by analyzing a specifically male perspective (Ojala et al., 2016). Niemistö et al. (2016) define the concept in the organizational context and call it “organizational ageism”—one of the less visible forms of gendered ageism that is linked with the different features of generations in the work context and management’s difficulties to acknowledge them.

New ageism is another extension of the ageism concept (Laliberte-Rudman, 2015a; Laliberte-Rudman & Molke, 2009; McVittie et al., 2003; Riach, 2007), which is utilized with two different meanings. First, it refers to a discursive strategy of marginalization based on age that increases inequality under the apparent cover of egalitarianism (McVittie et al., 2003). Under this concept, authors show that diversity policies, which are produced to promote older workers’ inclusion, have a side effect of categorizing and separating this age group from others, highlighting its perceived homogeneity and negative common features. Second, (Laliberte-Rudman 2015a) described new ageism as the shift from fear of aging toward fear of aging with disability, stressing the fear of functionality loss often associated with aging.

Qualitative Thematic Analysis

The analysis revealed three main themes, which are as follows: (a) experiences of ageism, (b) social construction of age and ageist ideologies, and (c) strategies to counteract (dilute) ageism. Each paper presents one or more of these themes, as given in Table 2. A representation of themes and subcontents is shown in Figure 2.

Experiences of ageism

This theme includes papers where researchers give voice to participants to describe their experiences of stereotypical treatment and discrimination because of their age. These studies document how ageism takes place in participants’ accounts of their everyday working life. The subcontents included in this theme are context, subjects and intersectionality, and causes accounted by participants (individual meaning-making process).

Context

Thirteen studies reported that workers experience ageism in various contexts, including access to training and promotion opportunities compared with younger colleagues (Grima, 2011) and reeducation and job search (Brodmerkel & Barker, 2019; George & Maguire, 1998; Maguire, 2001; McVittie et al., 2008; Moore, 2009; Noonan, 2005; Porcellato et al., 2010; Quintrell & Maguire, 2007; Yang, 2012). Two studies specifically looked at the environment of the unemployment agency (Berger, 2006; Handy & Davy, 2007) and one focused on the occupational possibilities near retirement age (Laliberte-Rudman, 2015b).

Subjects and intersectionality

Women’s experiences receive major attention in the selected papers because the intersection between gender and age increases the vulnerability of the group to stereotypes, prejudices, and discrimination. Experiences of ageism are reported by women of all ages: Young women report being perceived as incompetent by male colleagues in information technology jobs (Allen et al., 2006), while older women sustain that looks and unattractiveness represent a major reason for discrimination (Granleese & Sayer, 2006, Handy & Davy, 2007; Kanagasabai, 2016; Maguire, 1995; Moore, 2009). Regarding male experience, Ojala et al. (2016) analyzed how men are not totally immune to ageism, but rather, experiences and interpretations of ageism are structured by the interactional context in question. Acts and expressions interpreted as discriminative in one context become defused in others, for example, in family contexts, positive ageism represents a naturalized order of things within intergenerational relations. The intersectional perspective on ageism highlights that, besides age and gender, class and ethnicity also influence people’s working lives (Bowman et al., 2017; Moore, 2009). In health care settings, the intersection of ageism and loss of functionality is referred by participants as an incentive to stereotypical treatment (Billings, 2006; Higashi et al., 2012; Samra et al., 2015).

Causes

In the work-life accounts, research participants often explain ageism with reference to their personal attributes, such as slowing bodies (Bowman et al., 2017), decreased work ability (McMullin & Marshall, 2001), increased health problems (Crăciun et al., 2018), and low skills and ability to learn new things (Crăciun et al., 2018; McMullin & Marshall, 2001). Beyond these negative attributes, research participants have explained ageism in relation to their overqualification and the expensiveness that comes with experience (Brodmerkel & Barker, 2019; Noonan, 2005) or expertise that enables them to resist management’s authorities (Bowman et al., 2017; Moore, 2009).

Working life experiences of ageism are not only related to workers’ age but also the age of the clients that professionals encounter. In health care settings, professionals report a shared stereotypical perception of older patients as low value, difficult, and boring. This results in professionals working with older people experiencing structural ageism in resource allocation among patient groups (Klein & Liu, 2010; Samra et al., 2015).

Social construction of age and ageist ideologies

Discourses and ideologies regarding age are collaboratively constructed in our society, and they become tangible in social interaction. In this section, the included papers are synthesized regarding the type of construction researchers provide about age, workers, and ageism in society. The grounding of this theme is in the social constructionist perspective (Burr, 2015), through which age—and consequently, ageism—is understood as socially constructed through discourses and social interactions. The contents included in this theme represent different types of ideologies and social construction regarding ageism in the working life: aging as a hindering process, the normative construction of the life course, the “othering” of older workers, and the organizational ageist discourses.

Aging as a hindering process

Numerous papers claim that ageism derives from the social construction of aging as a hindering process and the obsession of our society to be ageless and aspire for perpetual youthfulness and beauty (Brodmerkel & Barker, 2019; Laliberte-Rudman, 2015a; Laliberte-Rudman & Molke, 2009; Romaioli & Contarello, 2019; Spedale, 2019; Spedale et al., 2014). Spedale et al.’s (2014) analysis of an age discrimination case law report from a U.K. tribunal showed that youth ideologies are reified in the workplace and used to justify rejuvenation discourses and practices. Handy and Davy (2007) showed that the internalized ideology of youthfulness sustains female recruiters’ fear of growing old and provokes repulsion toward older jobseekers. Through a discourse analysis of recruiters’ accounts, Faure and Ndobo (2015) found that, if professionals rate applicants similarly on a scale, their discourses unfold gender- and age-based discrimination, although these phenomena are overtly condemned. Through an analysis of Canadian newspaper articles, Laliberte-Rudman and Molke (2009) showed that governmental policies related to “active aging” contribute to the idea that older persons need to be perpetually active and healthy; this will help meet neoliberal governments’ economic need. In health care settings, negative beliefs about age influence career trajectories of nurses, doctors, and therapists, who become reluctant to specialize in gerontology (Gould et al., 2015; Higashi et al., 2012; Samra et al., 2015).

Normative construction of life course

Another societal discourse that fosters a negative attribution of aging is the normative construction of the life course and the connected fear of failing to meet the career stages that society has established for each social group. Failing to achieve the expectations associated with each age group (education, work, family, and retirement) or trying to deviate from a fixed pattern (e.g., starting education in older age) engenders feelings of self-exclusion, marginalization, and negative self-identity (Berger, 2006; Dixon, 2012; McVittie et al., 2008; Romaioli & Contarello, 2019).

“Othering” older workers

The social construction of the normative life course contributes to the construction of older workers as a specific category, “othered” from alternative age and work groups. Older workers who have lost their jobs face greater difficulties in reentering the job market because they deviate from the traditional career path that assumes an uninterrupted progression until retirement. To facilitate the transition from unemployment to employment, job centers’ professionals group and label older workers, attributing to them features that would make them, supposedly, more appreciable by employers. According to Berger (2006), older workers are depicted as calm, elastic, and loyal. These features match the types of positions available for them in the present job market, which are entry-level soft jobs that require no expertise. This characterization is used strategically to downgrade older workers to these types of jobs; however, it contradicts common stereotypes related to older people, who are usually described as inelastic and not prone to change (Berger, 2006; Handy & Davy, 2007; Laliberte-Rudman & Molke, 2009; Riach, 2007). In unemployment center practices, professionals reify negative stereotypes when they create separate training for seniors (Berger, 2006). Through the discursive strategies of depicting older workers as calm, flexible, and loyal, organizations and institutions justify the downgrading of precarious jobs in late career stages. Therefore, ageism creates structural constraints for older people, reducing their actions and choices within labor markets (Yang, 2012). This analysis sustains that labor force policies, especially in the Western world, are generally constructed for healthy, White, middle-class men, which problematizes the intersections of age with gender, disability, and social class.

Organizational ageist discourses

In organizations, ageist ideologies are reified in the systematic preference of younger groups in training and promotion, as discussed in the previous section. This imbalance reinforces the discourse proposed by management that senior employees are less creative and physically and cognitively unable to keep up with firms’ dynamics (Brodmerkel & Barker, 2019; Faure & Ndobo, 2015; Porcellato et al., 2010; Yang, 2012). Even when organizations have inclusive policies in place, these can be used to “other” older workers (McVittie et al., 2003). In recruitment, the preference for younger workers is justified by the “team fit” discourse, through which older workers are denied access to jobs because they would not fit the young climate of organizations (Riach, 2007). The social meaning and construction of age and generations in the work context were analyzed by Niemistö et al. (2016). It was found that workers use different discourses to talk about age and generations at work: older workers emphasize physical hindrance due to age, retirement trajectories, missing generations within the workplace and age gaps, and organizational silence about age diversity. Inside the studied organizations, age was collectively constructed with both positive (experience) and negative (embodied physical difficulties) features. Likewise, generations were mental states built both on personal experiences and collective features of memory as organizational groups.

Strategies used to counteract, or dilute, ageism

This theme synthesizes the strategies that individuals, as well as organizations, implement to counteract ageism. In the previous themes, structural barriers and societal ageism were addressed while here, we emphasize the negotiation that might happen at a more intrapersonal and interpersonal level. Nevertheless, systemic ageism is present, and personal strategies take place within a workplace that enables or hinders them. The micro and macro levels are not mutually exclusive; on the contrary, discursive approaches are always context based and influenced by the societal discourse and ideologies, presented in Theme 2. The contents analyzed in the included papers comprised the following: coping strategies that participants proposed as their solution to fight ageism; discursive strategies used in interaction, through which participants negotiated ageism and rejected negative attribution in talk; and organizational strategies that addressed the phenomenon.

Coping strategies

The main coping resource reported by research participants is social support (Berger, 2006; Grima, 2011). Grima (2011) shows that older employees use social support to increase the sense of membership to the work community and personal value. Unemployed adults use social support outside work, from family or unemployment classes, as a resource to fight ageism: It reduces the stress associated with the loss of a job and social contacts (Berger, 2006). Hence, the author suggests that the creation of support groups is strategic for unemployment offices. In their everyday work, older workers claim to use three different strategies—accepting the discrimination and focusing on positive aspects of life outside work, overtly fighting the discrimination in the workplace, and valuing their contribution to the organization (Grima, 2011). Another coping strategy reported by research participants is maintaining a youthful appearance (Brodmerkel & Barker, 2019).

Discursive strategies

Regarding discursive strategies, Romaioli and Contarello (2019) mentioned rhetorical strategies used by people at different ages to counteract the detrimental narrative of being “too old for.” They described three counter-narratives based on willpower, denial of aging, and discovering the potentiality of aging. Through these measures, dominant discourses on ageism may be adapted, negotiated, or resisted. In the employment center, negotiating a new identity is another strategy to counteract ageism used by people when they perceive that they are getting older or others label them as such. Berger (2006) shows that, when faced with age stereotypes in retiring, older workers either maintain their work identity and reinforce its value or tend to shift toward a new identity, that of retirees. Laliberte-Rudman (2015b) looked at how older people position themselves regarding their age and noted that internalizing ageism changes older workers’ relation to work, facilitating labor market detachment. These studies highlight how identity negotiation might be affected by internalized and subconscious ageist attitudes, which are reinforced by the institutions.

Brodmerkel and Barker (2019) studied older workers in the advertising industry and found that, to combat ageism in the field, older workers developed “resigned resilience.” Older workers continued to try to make a living in the advertising industry while acknowledging the ageist structures of their field. Employing discursive strategies, they positioned themselves as having “mature strategic experience” compared with the youthful creativeness of younger workers.

People who work with older people also use strategies to dilute ageism. Herdman (2002) showed that nursing students can challenge ageist discourses by portraying themselves and their career choices in ways that value positive features associated with aging and the value of working with older patients.

Organizational strategies

Organizations develop strategies to counteract ageism in the workplace. In contrast, equality policies can have a detrimental effect as they may increase managers’ fear of behaving inappropriately toward older workers, and therefore, enhance their exclusion (Phillipson et al., 2019), sustaining and reifying ageist ideologies. Managers can be too afraid of acting in the wrong way toward older workers, not enacting the values of respect and inclusion; as a result, they prefer to avoid managing such employees.

Discussion and Implications

This scoping review set out to synthesize the distinct contributions made by discursive studies on ageism in working life. The analysis pronouncedly highlighted the selected approach’s ability to advance knowledge in the field of ageism and the gaps in the knowledge on two levels, namely, topic and research approach.

Despite some existing reviews published on ageism and work, this is the first, to the best of our knowledge, to zoom in on the specificity of discursive approaches along the continuum of working life. Most studies in the field of ageism in the workforce have given major attention to quantitative research and older workers. Within the tradition of discursive research, the papers selected provide additional and innovative information on the construction of age and ageism as a social category and how this construction is embedded in the social practices within and outside the workplace. The discursive investigation unfolds the hidden ideologies in working life which constituted the grassroot of ageism; these ideologies connect the organizational level to the societal one, demonstrating the interlinks among micro, meso, and macro levels. This connection is especially visible in Theme 2, while the reification of ideologies and discourses is visible in Themes 1 and 3, in the application to experiences and strategies. Theme 1 is more descriptive, but, compared to previous reviews, still interestingly emphasizes the portrayal of ageism solely as perceived by workers, highlighting the importance of giving voice to participants. Thanks to this point of view, this study brings to light how workers create a justification for ageism and how they give both external and internal attribution to age discrimination, demonstrating the impact of internalization of ageism also in the labor market. Compared to other reviews, this study demonstrates how work-based relations and discourses engender ageism and its reproduction at a personal as well as organizational level and how discourse is rooted in societal ideologies. This finding is valid both for younger and older workers; in fact, it is supported by the diversity of participants’ age, underscoring that ageism affects all persons. Moreover, chronologically old as well as young participants use the discursive strategies, presented in Theme 3. This finding shows that age and ageism are contextual, and feeling old or young is not defined by year of birth but is a part of personal identity, which is fluid and influenced by social relations, environments, and actions. Persons do things with words, they can do ageism as well as undo and challenge it: These dynamics can be studied mainly through discursive approaches, as this review highlights.

Implications

The included papers are part of a stream of research that supports a shift in analyzing the phenomenon of ageism and provides novel insight into policymaking. On the one hand, the mainstream literature often considers older workers as an assigned category based on chronological age and a group victim of a perpetual process of discrimination enacted by employers. On the other hand, the discursive approach carefully unpacks the dynamic connection between age and identity, looking at how workers reject or negotiate age-based labels. In this field, researchers view ageism as enacted in the social process—how it is created, maintained, and reproduced in interactions, considering the use of age and its meaning in the work context (Spedale, 2019).

The review showed that workers, of all ages, adapt to ageist discourses available in society. These are rooted in a youthfulness ideology and reinforced by a normative life course (Romaioli & Contarello, 2019). This study highlighted how some policies that aim at fighting ageism fail in their mission because they originate from the same ideology which they want to combat (Laliberte-Rudman, 2015a, 2015b; Laliberte-Rudman & Molke, 2009). In working life, persons are labeled as older or younger when they enter a certain chronological age. This labeling attaches a predefined identity to a single person and thus reinforces negative age self-stereotypes.

This review yields views on how negative attitudes attached to age are both enforced and challenged in and through situated interactions. The analysis of discourses sheds light on the negotiation of positive age identity in the work context and shows how persons can respond to ageism in their everyday lives, freeing themselves from the normalized life stages and focusing on the positive aspects of aging. The contribution of the discursive approach is to highlight how persons do and undo ageism in situ, with no intention of neglecting macro- and meso-dynamics, while bridging macro and micro approaches in gerontology (Nikander, 2009). The results will inform policymakers and practitioners that counteracting ageism in the everyday accounts of working life is possible, but it is important to create an enabling environment that does not exclude people based on their age and that deconstructs the ideology that depicts aging as negative. To achieve this goal, further research is needed that engages in different approaches and methods. In the next section, future directions for research are outlined.

Gaps in the Knowledge

Our review shows that the field clearly needs to continue tackling the notion of ageism in novel and inventive ways while remaining reflective on the choice of methodology and limitations therein. We identified areas that we suggest need improvement, which are as follows: studies on intersectionality beyond female gender and age; heterogeneity of age groups, from young workers to different subgroups in older workers; definitions of ageism; and deconstruction of the ageist ideology. Studies focusing on the first theme, “experiences of ageism,” report the ability of discursive studies to give voice to participants and unfold the situated dynamics of individually encountered aspects of ageism in working life. One aspect that clearly needs further research is intersectionality, including a wide range of social categories. Whereas the double jeopardy of age and gender faced by women has been extensively analyzed, male perceptions of ageism in the workforce form the core of just one paper in this review (Ojala et al., 2016). While social dimensions such as ethnicity, culture, class, ability, functionality, and their intersection with age and gender do, to a degree, feature in the selection of papers studied here, future research could enhance our understanding of the diverse and increasingly aging workforce.

One further point concerns the clear need for a more detailed problematization of the category age itself. It is noteworthy that even when the approach is discursive, very few papers deconstruct the category “older workers” itself (Spedale, 2019). Various authors, following the standard research process, sample their participants based on chronological age, labeling the ones older than 50 years old as older workers. This is congruent with the literature and policies on old age in the workforce (starting at 50 or 55 years old), but it does not allow us to understand how organizations or individuals construct this categorization. Subsequently, there is a lack of research on ageism and younger workers, or even more, studies that investigate age along its continuum. This is incoherent and inconsistent with the definition of ageism—a phenomenon directed toward all age groups—but it is consistent with previous critiques about the conceptualization of older people as an open-ended category in gerontology (Bytheway, 2005). Hence, further studies in this vein could tap into the complexity of the phenomenon of ageism on different levels (individual, group, organization, and society) and elucidate its different features (cognitive, affective, and behavioral).

Within research methods, the main gap we identified was the lack of diversity in data generation and analysis in the discursive field. The accepted papers predominantly utilized interviews (24 of 39 papers). Hence, inside the discursive perspective, there is clearly room for research based on a wider range of data, such as naturally occurring encounters (recordings, video recordings, and textual material) or quantitative discursive studies. For example, the analysis of talk in interaction would enhance the understanding of ageism not as a natural category but as accomplished in situated social communications (Krekula et al., 2018). This approach has received recognition in the study of age and aging (Aronsson, 1997; Krekula et al., 2018; Thomas et al., 2014), but empirical studies on ageism in everyday work encounters are still rare.

From a methodological standpoint, there is a clear absence of longitudinal studies. Although qualitative longitudinal data sets are not traditionally approached from a discursive perspective, this is an open direction for further research. It has already been highlighted that investigations based on longitudinal studies are needed to understand how ageism can be experienced in transitions in later life (Bytheway, 2005; Harris et al., 2018; Levy & Macdonald, 2016).

Limitations

This scoping review has carefully followed a systematic step-by-step approach, but some limitations need to be acknowledged. First, the definition of search terms, which are always limited as is the nature of a scoping review, sets an initial barrier to the certainty of retrieving all the relevant contributions. Accordingly, the screening of reference and consultation with senior experts are a fundamental integrative step that helped to include relevant literature. Second, the choice of databases sets an objective limitation on the retrieval of published papers. Third, the inclusion of only electronically accessible papers in English is a constraint for the review regarding the publication date, as older publications may not be uploaded in electronic databases, and the country of origin, as relevant papers may have been published in languages other than English. Nevertheless, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first review focusing on the discursive approach in the field of ageism and working life. The retrieved papers clearly show the substantial contribution of the discursive turn in social science and of the cultural turn in gerontology (Twigg & Martin, 2015), as well as the ability of the included approaches to expand the understanding of the nuances of ageism while challenging some of the mainstream conceptualizations.

In conclusion, ageism research has clearly flourished since the coinage of the term, and the discursive turn helped produce a notable shift in approaches, data sets, and analytic stances. Numerous research areas, topics, and fresh research designs remain to be developed and taken up. Further problematization of age, its intersectional aspects, and the difference between chronological and socially constructed age—young or old—remains a beneficial framework that yields nuanced knowledge on the everyday conceptualization and meaning making related to age and ageism in the work context.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The writing assistance by Laura D. Allen, EU H2020 MSCA-ITN EuroAgeism early-stage researcher and PhD student at Bar-Ilan University, is greatly appreciated.

Funding

This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement No. 764632.

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

References

- Allen, M. W., Armstrong, D. J., Riemenschneider, C. K., & Reid, M. F. (2006). Making sense of the barriers women face in the information technology work force: Standpoint theory, self-disclosure, and causal maps. Sex Roles, 54(11–12), 831–844. doi: 10.1007/s11199-006-9049-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. doi: 10.1080/1364557032000119616 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aronsson, K. (1997). Age in social interaction. On constructivist epistemologies and the social psychology of language. International Journal of Applied Linguistics, 7(1), 49–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1473-4192.1997 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Harush, A., Shiovitz-Ezra, S., Doron, I., Alon, S., Leibovitz, A., Golander, H., Haron, Y., & Ayalon, L. (2017). Ageism among physicians, nurses, and social workers: Findings from a qualitative study. European Journal of Ageing, 14(1), 39–48. doi: 10.1007/s10433-016-0389-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger, E. D. (2006), “Aging” identities: Degradation and negotiation in the search for employment. Journal of Ageing Studies, 20(4), 303–316. doi: 10.1016/j.jaging.2005.11.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Billings, J. (2006). Staff perceptions of ageist practice in the clinical setting: Practice development project. Quality in Ageing and Older Adults, 7(2), 33–45. doi: 10.1108/14717794200600012 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bowman, D., McGann, M., Kimberley, H., & Biggs, S. (2017). “Rusty, invisible and threatening”: Ageing, capital and employability. Work, Employment and Society, 31(3), 465–482. doi: 10.1177/0950017016645732 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brodmerkel, S., & Barker, R. (2019). Hitting the “glass wall”: Investigating everyday ageism in the advertising industry. The Sociological Review, 67(6), 1383–1399. doi: 10.1177/0038026119837147 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Burr, V. (2015). Social constructionism. Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9781315715421 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Butler, R. N. (1969). Age-ism: Another form of bigotry. The Gerontologist, 9(4, Pt 1), 243–246. doi: 10.1093/geront/9.4_part_1.243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bytheway, B. (2005). Ageism and age categorization. Journal of Social Issues, 61(2), 361–374. [Google Scholar]

- Crăciun, I. C., Rasche, S., Flick, U., & Hirseland, A. (2018). Too old to work: Views on reemployment in older unemployed immigrants in Germany. Ageing International, 44(3), 234–249. doi: 10.1007/s12126-018-9328-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon, J. (2012). Communicating (St)ageism. Research on Aging, 34(6), 654–669. doi: 10.1177/0164027512450036 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Faure, A., & Ndobo, A. (2015). On gender-based and age-based discrimination: When the social ingraining and acceptability of non-discriminatory norms matter. Revue internationale de psychologie sociale, 28(4),7–43. doi: 10.7202/1020944ar [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- George, R., & Maguire, M. (1998). Older women training to teach. Gender and Education, 10(4), 417–430. doi: 10.1080/09540259820844 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gould, O. N., Dupuis-Blanchard, S., & MacLennan, A. (2015). Canadian nursing students and the care of older patients: How is geriatric nursing perceived? Journal of Applied Gerontology, 34(6), 797–814. doi: 10.1177/0733464813500585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granleese, J., & Sayer, G. (2006). Gendered ageism and “lookism”: A triple jeopardy for female academics. Women in Management Review, 21(6), 500–517. doi: 10.1108/09649420610683480 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grenier, A., Hatzifilalithis, S., Laliberte-Rudman, D., Kobayashi, K., Marier, P., Phillipson, C. (2019). Precarity and aging: A scoping review. The Gerontologist, 60(8), e620–e632. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnz135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grima, F. (2011). The influence of age management policies on older employee work relationship with their company. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 22(6), 1312–1332. doi: 10.1080/09585192.2011.559101 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gubrium, J. F. (1992). Qualitative research comes of age in gerontology. The Gerontologist, 32(5), 581–582. doi: 10.1093/geront/32.5.581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handy, J., & Davy. D. (2007). Gendered ageism: Older women’s experiences of employment agency practices. Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources, 45(1), 85–99. doi: 10.1177/1038411107073606 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Harris, K., Krygsman, S., Waschenko, J., & Laliberte Rudman, D. (2018). Ageism and the older worker: A scoping review. The Gerontologist, 58(2), e1–e14. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnw194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herdman, E. (2002). Challenging the discourses of nursing ageism. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 39(1), 105–114. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7489(00)00122-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higashi, R. T., Tillack, A. A., Steinman, M., Harper, M., & Johnston, C. B. (2012). Elder care as “frustrating” and “boring”: Understanding the persistence of negative attitudes toward older patients among physicians-in-training. Journal of Aging Studies, 26(4), 476–483. doi: 10.1016/j.jaging.2012.06.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanagasabai, N. (2016). In the silences of a newsroom: Age, generation, and sexism in the Indian television newsroom. Feminist Media Studies, 16(4), 663–677. doi: 10.1080/14680777.2016.1193296 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Klein, J., & Liu, L. (2010). Ageism in current practice: Experiences of occupational therapists. Physical and Occupational Therapy in Geriatrics, 28(4), 334–347. doi: 10.3109/02703181.2010.532904 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Krekula, C., Nikander, P., & Wilińska, M. (2018). Multiple marginalizations based on age: Gendered ageism and beyond. In Ayalon L. & Tesch-Römer C. (Eds.), Contemporary perspectives on ageism (pp. 33–50). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Laliberte-Rudman, D. (2015a). Embodying positive aging and neoliberal rationality: Talking about the aging body within narratives of retirement. Journal of Aging Studies, 34, 10–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jaging.2015.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laliberte-Rudman, D. (2015b). Situating occupation in social relations of power: Occupational possibilities, ageism and the retirement “choice.” South African Journal of Occupational Therapy, 45(1), 27–33. doi: 10.17159/2310-3833/2015/v45no1a5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Laliberte-Rudman, D., & Molke, D. (2009). Forever productive: The discursive shaping of later life workers in contemporary Canadian newspapers. Work (Reading, Mass.), 32(4), 377–389. doi: 10.3233/WOR-2009-0850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levac, D., Colquhoun, H., & O’Brien, K. K. (2010). Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implementation Science, 5, 69. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-5-69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy, B. R. (2017). Age-stereotype paradox: Opportunity for social change. The Gerontologist, 57(S2), S118–S126. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnx059 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Levy, S. R., & Macdonald, J. L. (2016). Progress on understanding ageism. Journal of Social Issues, 72(1), 5–25. doi:10.11117josi.12153 [Google Scholar]

- Levy, B. R., Slade, M., Chang, E., Kannoth, S., & Wang, S. Y. (2020). Ageism amplifies cost and prevalence of health conditions. The Gerontologist, 60(1), 174–181. doi: 10.1093/geront/gny131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maguire, M. (1995). Women, age, and education in the United Kingdom. Women’s Studies International Forum, 18(5–6), 559–571. doi: 10.1016/0277-5395(95)80093-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maguire, M. (2001). Beating time?: The resistance, reproduction and representation of older women in teacher education (UK). International Journal of Inclusive Education, 5(2–3), 225–236. doi: 10.1080/13603110010020831 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McKinlay, A., & McVittie, C. (2009). Social psychology and discourse. Wiley. doi: 10.1002/9781444303094 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McMullin, J. A., & Marshall, V. W. (2001). Ageism, age relations, and garment industry work in Montreal. The Gerontologist, 41(1), 111–122. doi: 10.1093/geront/41.1.111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McVittie, C., McKinlay, A., & Widdicombe, S. (2003). Committed to (un)equal opportunities?: “New ageism” and the older worker. British Journal of Social Psychology, 42(4), 595–612. doi: 10.1348/014466603322595293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McVittie, C., McKinlay, A., & Widdicombe, S. (2008). Passive and active non-employment: Age, employment and the identities of older non-working people. Journal of Aging Studies, 22(3), 248–255. doi: 10.1016/j.jaging.2007.04.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- de Medeiros, K. (2019). Confronting ageism: Perspectives from age studies and the social sciences. The Gerontologist, 59(4), 799–800. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnz042 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moore, S. (2009). “No matter what I did I would still end up in the same position”: Age as a factor defining older women’s experience of labour market participation. Work, Employment and Society, 23(4), 655–671. doi: 10.1177/0950017009344871 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, T. D. (2016). The age of ageism. Journal of Social Issues, 72(1), 191–198. doi: 10.1111/josi.12162 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Niemistö, C., Hearn, J., & Jyrkinen, M. (2016). Age and generations in everyday organisational life: Neglected intersections in studying organisations. International Journal of Work Innovation, 1(4), 353–374. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-58813-1_11 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nikander, P. (2008). Constructionism and discourse analysis. In Holstein J. A. & Gubrium J. F. (Eds.), Handbook of constructionist research (pp. 413–428). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nikander, P. (2009). Doing change and continuity: Age identity and the micro–macro divide. Ageing and Society, 29(6), 863–881. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X09008873 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Noonan, A. E. (2005). “At this point now”: Older workers’ reflection on their current employment experiences. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 61(3), 211–241. doi: 10.2190/38CX-C90V-0K37-VLJA [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ojala, H., Pietilä, I., & Nikander, P. (2016). Immune to ageism? Men’s perceptions of age-based discrimination in everyday contexts. Journal of Aging Studies, 39, 44–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jaging.2016.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pak, K., Kooij, D. T., De Lange, A. H., & Van Veldhoven, M. J. (2019). Human resource management and the ability, motivation and opportunity to continue working: A review of quantitative studies. Human Resource Management Review, 29(3), 336–352. doi: 10.1016/j.hrmr.2018.07.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Palmore, E. (2015). Ageism comes of age. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 70(6), 873–875. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbv079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillipson, C., Shepherd, S., Robinson, M., & Vickerstaff, S. (2019). Uncertain futures: Organisational influences on the transition from work to retirement. Social Policy and Society, 18(3), 335–350. doi: 10.1017/S1474746418000180 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Porcellato, L., Carmichael, F., Hulme, C., Ingham, B., Prashar, A. (2010). Giving older workers a voice: Constraints on employment of older people in the North West of England. Work, Employment and Society, 24(1), 85–103. doi: 10.1177/0950017009353659 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Poscia, A., Moscato, U., La Milia, D. I., Milovanovic, S., Stojanovic, J., Borghini, A., Collamati, A., Ricciardi, W., Magnavita, N. (2016). Workplace health promotion for older workers: A systematic literature review. BMC Health Services Research, 16(5), 329, 416–428. doi: 10.1186/s12913-016-1518-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potter, J., & Wetherell, M. (1987). Discourse and social psychology: Beyond attitudes and behaviour. Sage. doi: 10.4324/9780203422311-24 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Quintrell, M., & Maguire, M. (2007). Older and wiser, or just at the end of the line? The perceptions of mature trainee teachers. Westminster Studies in Education, 23(1), 19–30. doi: 10.1080/0140672000230103 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Riach, K. (2007). “Othering” older worker identity in recruitment. Human Relations, 60(11), 1701–1726. doi: 10.1177/0018726707084305 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Romaioli, D., & Contarello, A. (2019). “I’m too Old for …” looking into a self-sabotage rhetoric and its counter-narratives in an Italian setting. Journal of Aging Studies, 48, 25–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jaging.2018.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samra, R., Griffiths, A., Cox, T., Conroy, S., Gordon, A., & Gladman, J. R. F. (2015). Medial student’s and doctors’ attitudes towards older patients and their care in hospital settings: A conceptualization. Age and Aging, 44, 776–783. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afv082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneid, M., Isidor, R., Steinmetz, H., & Kabst, R. (2016). Age diversity and team outcomes: A quantitative review. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 31(1), 2–17. doi: 10.1108/jmp-07-2012-0228 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smith, J. A. (1996). Beyond the divide between cognition and discourse: Using interpretative phenomenological analysis in health psychology. Psychology and Health, 11, 261–271. doi: 10.1080/08870449608400256 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Spedale, S. (2019). Deconstructing the “older worker”: Exploring the complexities of subject positioning at the intersection of multiple discourses. Organization, 26(1), 38–54. doi: 10.1177/1350508418768072 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Spedale, S., Coupland, C., & Tempest, S. (2014). Gendered ageism and organizational routines at work: The case of day-parting in television broadcasting. Organization Studies, 35(11), 1585–1604. doi: 10.1177/0170840614550733 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Starks, H., & Trinidad, S. B. (2007). Choose your method: A comparison of phenomenology, discourse analysis, and grounded theory. Qualitative Health Research, 17(10), 1372–1380. doi: 10.1177/1049732307307031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, P., Loretto, W., Marshall, V., Earl, C., & Phillipson, C. (2016). The older worker: Identifying a critical research agenda. Social Policy and Society, 15(4), 675–689. doi: 10.1017/s1474746416000221 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, R., Hardy, C., Cutcher, L., & Ainsworth, S. (2014). What’s age got to do with it? On the critical analysis of age and organizations. Organization Studies, 35(11), 1569–1584. doi: 10.1177/0170840614554363 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Truxillo, D. M., Cadiz, D. M., & Hammer, L. B. (2015). Supporting the aging workforce: A review and recommendations for workplace intervention research. Annual Review of Organisational Psychology and Organisational Behaviour, 2(1), 351–381. doi: 10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-032414-111435 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Twigg, J., & Martin, W. (2015). The challenge of cultural gerontology. The Gerontologist, 55(3), 353–359. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnu061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United Nation Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE) . (2019). Combating ageism in the world of work. United Nations. [Google Scholar]

- Vitman, A., Iecovich, E., & Alfasi, N. (2014). Ageism and social integration of older adults in their neighborhoods in Israel. The Gerontologist, 54(2), 177–189. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnt008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willig, C. (2003). Discourse analysis. Qualitative psychology: A practical guide to research methods (pp. 160–186), Vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO) . (2018). A global campaign to combat ageism. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 96, 299–300. doi: 10.2471/BLT.17.202424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y. (2012). Is adjustment to retirement an individual responsibility? Socio-contextual conditions and options available to retired persons: The Korean perspective. Ageing and Society, 32(2), 177–195. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X11000183 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.