Abstract

Background and Objectives

The common and unique psychosocial stressors and adaptive coping strategies of people with young-onset dementia (PWDs) and their caregivers (CGs) are poorly understood. This meta-synthesis used the stress and coping framework to integrate and organize qualitative data on the common and unique psychosocial stressors and adaptive coping strategies employed by PWDs and CGs after a diagnosis of young-onset dementia (YOD).

Research Design and Methods

Five electronic databases were searched for qualitative articles from inception to January 2020. Qualitative data were extracted from included articles and synthesized across articles using taxonomic analysis.

Results

A total of 486 articles were obtained through the database and hand searches, and 322 articles were screened after the removal of duplicates. Sixty studies met eligibility criteria and are included in this meta-synthesis. Four themes emerged through meta-synthesis: (a) common psychosocial stressors experienced by both PWDs and CGs, (b) unique psychosocial stressors experienced by either PWDs or CGs, (c) common adaptive coping strategies employed by both PWDs and CGs, and (d) unique adaptive coping strategies employed by either PWDs or CGs. Within each meta-synthesis theme, subthemes pertaining to PWDs, CGs, and dyads (i.e., PWD and CG as a unit) emerged.

Discussion and Implications

The majority of stressors and adaptive coping strategies of PWDs and CGs were common, supporting the use of dyadic frameworks to understand the YOD experience. Findings directly inform the development of resiliency skills interventions to promote adaptive coping in the face of a YOD diagnosis for both PWDs and CGs.

Keywords: Caregiving, Dyads, Early-onset dementia, Stress and coping, Systematic review

Patients with a young-onset dementia (YOD)—defined by an age of onset younger than 65 years—commonly have atypical symptom profiles compared to late-onset dementia, including less frequent amnesia and more frequent executive dysfunction, aphasia, agnosia, mood and behavioral symptoms (e.g., personality changes, disinhibition, apathy), and sensorimotor symptoms as the illness progresses (Ducharme & Dickerson, 2015). Syndromic diagnoses in YOD include behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia (FTD), primary progressive aphasia, posterior cortical atrophy (PCA), and progressive dysexecutive syndromes (Bang et al., 2015; Mendez, 2019; Sapolsky et al., 2011; Wong et al., 2019). The etiologies of YOD include frontotemporal lobar degeneration, Alzheimer’s disease, Lewy body disease, other neurodegenerative diseases, and other uncommon neurologic diseases.

In part because the diseases-causing dementia are relatively rare in people younger than 65, the diagnostic journey is long and filled with uncertainty and distress. The YOD diagnosis serves as a serious and life-altering event for both persons with YOD (PWDs) and their informal caregivers (CGs) (Spreadbury & Kipps, 2019b). In addition to the lack of cure and impactful treatments, YOD strikes people in the prime of their lives, when most are still working, raising children, and are free from other health conditions. Quantitative systematic reviews indicate that emotional distress is common in CGs and many PWDs after diagnosis. Qualitative studies characterize the nuanced experiences of PWDs and CGs after diagnosis, including the psychosocial stressors faced such as functional limitations of PWDs, increased PWD dependency on CGs, disruptions in the PWD–CG relationship and their larger social support network structure, social isolation, and stigma (Spreadbury & Kipps, 2019b). In the setting of YOD, PWDs and CGs face a shortage of age-appropriate psychosocial resources to facilitate adaptive coping and to prevent emotional distress and CG burnout (Millenaar et al., 2016).

Quantitative studies focused primarily on CGs have shown that PWD and CG emotional distress and high CG burden are a function of avoidant coping strategies (Spreadbury & Kipps, 2019a). Several qualitative studies have described the ways in which PWDs and CGs engage in avoidant coping strategies in order to sidestep difficult conversations and challenging emotions and attempt to preserve normalcy in their lives. Some of these strategies include avoiding social contact and minimizing or hiding their diagnosis (Greenwood & Smith, 2016). These strategies may provide initial relief and protection from intense emotions, but can lead to isolation and disconnection between PWDs, CGs, and their larger social network. In contrast, some PWDs and CGs describe using more adaptive coping strategies, including accepting changing abilities, finding humor in their situation, focusing on meaningful activities and positive experiences, and finding new ways to connect with others (Clemerson et al., 2014). However, the high rates of emotional distress and CG burden across quantitative studies (Spreadbury & Kipps, 2019a) suggest that few PWDs and CGs are able to consistently and effectively engage in adaptive coping strategies.

The stress and coping framework (Biggs et al., 2017; Lazarus & Folkman, 1984) provides a context for organizing and understanding the experiences of PWDs and CGs when faced with YOD. Within this framework, stressors are situations perceived as challenging, threatening, or aversive, and coping strategies are the responses persons adopt to manage these stressors (Biggs et al., 2017). Adaptive coping strategies buffer the effect of stressors and lead to good emotional health and quality of life. Because serious medical illnesses like YOD profoundly impact both persons with the diagnosis and their primary CGs, stress and coping frameworks expanded to focus on the dyad (i.e., PWD and CG as a unit; Falconier & Kuhn, 2019). Consistent with dyadic stress and coping models, an individual’s stress and coping can impact not only their own emotional health, but also that of their partner. Within dyadic frameworks, both individual and dyadic coping strategies (i.e., PWD and CG enacted together) can mitigate the impact of stressors. Though a dyadic stress and coping framework has yet to be applied to the context of YOD, it could be used to understand (a) the stressors that PWDs and CGs experience individually and as a dyad, and (b) the adaptive coping strategies that PWDs and CGs can employ both individually and as a dyad to navigate the YOD diagnosis and associated challenges (Falconier & Kuhn, 2019).

With earlier and more confident diagnoses of YOD (Mayrhofer, Shora, et al., 2020) comes an important opportunity to engage dyads of PWDs and CGs in programs focused on teaching adaptive coping strategies. A necessary first step in developing such preventive dyadic interventions is to synthesize the qualitative literature on postdiagnosis psychosocial stressors and adaptive coping strategies of PWDs, CGs, and dyads. The question driving the present meta-synthesis is: What are the common (i.e., reported by both PWDs and CGs) and unique (i.e., specific to PWDs or CGs) psychosocial stressors and adaptive coping strategies of PWDs and their CGs after YOD diagnosis?

Method

Aim

We aimed to identify and synthesize qualitative studies examining the experiences of PWDs, CGs, and dyads in order to gain a deeper understanding of the stressors and adaptive coping strategies employed by each and to summarize the common and unique facets of their experiences to inform psychosocial resources for dyads of PWDs and CGs.

Search Strategy and Screening

Our meta-synthesis conforms with PRISMA guidelines (Moher et al., 2009), and is registered on PROSPERO (CRD42020164802). We searched five electronic databases (PubMed, PsychINFO, CINAHL, MEDLINE, and Scopus) from inception until January 2020. The search strategy comprised three key concepts derived from our overarching aim: YOD diagnosis, qualitative research, and PWD or CG experiences (Supplementary Table 1). We used a three-stage screening approach to article selection, in which we (a) screened article titles for relevance, (b) applied inclusion and exclusion criteria (Table 1) to abstracts and full-text articles, and (c) discussed inclusion of articles among the study team where disagreement occurred between two reviewers. A detailed description of the search and screening procedure can be found in the Supplementary Materials.

Table 1.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

| 1. Article is written in English | 1. Article does not concern primary data collection (e.g., opinion article or literature) |

| 2. Published in a peer-reviewed academic journal | 2. Used quantitative methodology only for data collection and analysis |

| 3. Concerns original research and primary data collection | 3. Concerns patients or informal caregivers to patients with a diagnosis of later-onset dementia (patients aged 65 and older) or a non-YOD diagnosis |

| 4. Used any type of qualitative methods for data collection or qualitative analysis of data (including mixed-methods) | 4. Not relevant to the experiences, challenges, needs, or coping strategies of patients and/or caregivers, or concerning the pre-diagnosis period |

| 5. Concerns patients or informal caregivers to patients with a diagnosis of YOD (patients aged 65 and under) | |

| 6. Relevant to the experiences, challenges, needs, or coping strategies of patients and/or caregivers in the postdiagnosis period |

Note: YOD = young-onset dementia.

Quality Appraisal

We assessed the methodological and reporting quality of all included studies using the 10-item Critical Appraisal Skills Program (CASP) (Critical Skills Appraisal Programme, 2018) The CASP comprises 10 criteria related to methodological and reporting quality of qualitative studies, including (a) clarity and appropriateness of objective and aims, (b) appropriateness of qualitative methodology, (c) study design, (d) sampling method, (e) data collection, (f) reflexivity of researchers, (g) ethics, (h) data analysis, (i) rigor of findings, and (j) significance of the research. Each criterion is rated using a three-category scale of No (1 point), Can’t tell (2 points), and Yes (3 points), resulting in summed overall quality scores for each article ranging from 10 to 30. Two independent reviewers rated every included article and met to discuss disagreements in quality ratings to reach consensus. Overall, included studies were of good quality (M = 25.75; range = 19–30). Table 2 depicts the overall distribution of quality ratings for all criteria appraised.

Table 2.

CASP Checklist Rating of Included Studies

| Criteria | Met criteria (3) | Somewhat met criteria (2) | Did not meet criteria (1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Was there a clear statement of the aims of the research? | 48 | 11 | 1 |

| 2. Is a qualitative methodology appropriate? | 60 | 0 | 0 |

| 3. Was the research design appropriate to address the aims of the research? | 41 | 18 | 1 |

| 4. Was the recruitment strategy appropriate to the aims of the research? | 21 | 26 | 13 |

| 5. Were the data collected in a way that addressed the research issue? | 41 | 18 | 1 |

| 6. Has the relationship between researcher and participants been adequately considered? | 7 | 15 | 38 |

| 7. Have ethical issues been taken into consideration? | 44 | 14 | 2 |

| 8. Was the data analysis sufficiently rigorous? | 46 | 9 | 5 |

| 9. Is there a clear statement of findings? | 49 | 10 | 1 |

| 10. How valuable is the research? | 53 | 4 | 3 |

Note: CASP = Critical Appraisal Skills Programme.

Data Extraction Process

Two reviewers read the full text of every article included in the analysis, and independently extracted findings within predefined domains of interest based on our research questions (i.e., (a) psychosocial stressors and (b) adaptive coping strategies, as relevant for (a) PWDs, (b) CGs, and (c) within the dyadic PWD–CG relationship). The two reviewers discussed discrepancies to reach agreement and consolidate findings.

Data Synthesis

We carried out data analysis using the analytical framework of meta-synthesis, in which findings are integrated across studies to offer novel interpretations of the evidence (Walsh & Downe, 2005). We compiled and organized findings within the domains of interest that structured the data extraction process to create taxonomies of findings to facilitate taxonomic analysis. We developed two initial taxonomies of findings pertaining to (a) psychosocial stressors and (b) adaptive coping strategies, with findings organized separately for PWDs and CGs. Two reviewers (S. Bannon and M. Reichman) iteratively revised the taxonomies to collapse highly similar findings to reduce redundancy and promote concise wording without loss of granularity. As the final stage of our analysis, we examined the taxonomies of findings for PWDs and CGs side-by-side to elucidate the common stressors and coping strategies, and those that are distinct.

Findings

Characteristics of Studies

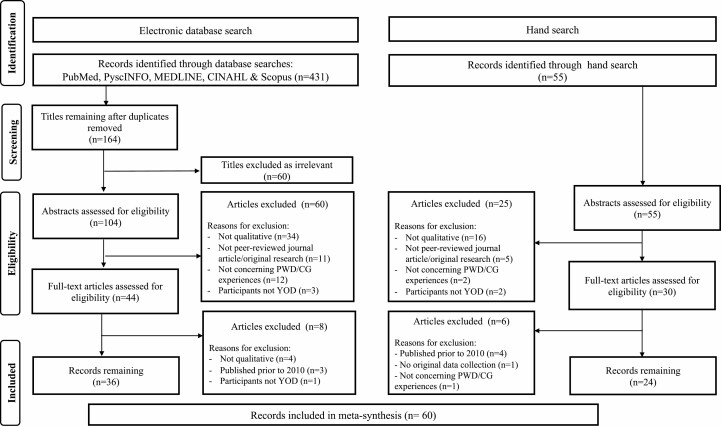

Figure 1 presents a PRISMA flow chart of the study search and selection process. Our meta-synthesis included 60 articles after the full-text inclusion screen. Supplementary Table 4 displays the participant and study characteristics of all articles included in our review. Included studies were conducted in a number of countries, including the United Kingdom (N = 17), Norway (N = 11), multiple European countries (N = 9), France (N = 6), Canada (N = 6), Australia (N = 5), United States (N = 3), South America (N = 3), as well as Hong Kong and Israel (N = 1 for each). The mean sample size across studies was 25.6 (SD = 36.0, range = 1–233). Methods of data collection predominantly included semistructured interviews of either PWDs (N = 26) or CGs (N = 29). Few (N = 3) studies included dyads of PWD and CGs interviewed together. In addition, some studies included interviews of other individuals (i.e., individual non-CG family members, professional care providers for PWDs) (N = 13) or focus groups (N = 8) including a combination of PWDs, CGs, other family members, and professional care providers for PWDs.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram.

To analyze qualitative data, studies primarily used thematic analysis (N = 24), interpretative phenomenological analysis (N = 10), or grounded theory (N = 7). Approximately half (48%) of the studies reported on time elapsed since YOD diagnosis for participants. Out of these studies (N = 29), 40% reported that individuals were diagnosed on average more than 1 year before study participation. Two studies included both individuals with YOD and later-onset dementia (>65) yet presented findings separately for each group. In addition, some studies focused on specific subtypes of YOD, such as FTD (N = 20) and PCA (N = 6). CGs included spouses (N = 25), children (N = 16), and other family members (N = 2).

Synthesized Findings

Based on the integration of qualitative findings across the reviewed literature, we identified four meta-synthesis themes: (a) common psychosocial stressors experienced by both PWDs and CGs, (b) unique psychosocial stressors experienced by either PWDs or CGs, (c) common adaptive coping strategies of PWDs and CGs, and (d) unique adaptive coping strategies of PWDs or CGs. Tables 3 and 4 and Supplementary Tables 2 and 3 present the subthemes and specific findings associated with each theme along with the literature supporting each finding. Stressors and adaptive coping strategies that pertain to PWDs and CGs as a unit or to the PWD–CG relationship (i.e., dyadic) are denoted in the tables with an asterisk.

Table 3.

Common Stressors of Persons With YOD and Their Informal Caregivers After Diagnosis

Notes: CG = caregiver; PWD = person with dementia; YOD = young-onset dementia.

aFindings that are dyadic in nature, or related to the relationship between PWD and CG.

Table 4.

Common Adaptive Coping Strategies of Persons With YOD and Their Informal Caregivers After Diagnosis

Notes: CG = caregiver; PWD = person with dementia; YOD = young-onset dementia.

aFindings that are dyadic in nature, or related to the relationship between PWD and CG.

Theme 1: Common Stressors of Persons With YOD and Informal CGs

Our review elucidated the various forms of psychosocial stressors that are common among PWDs and CGs (Table 3). We organized common stressors into the following subthemes: (a) initial impact of the diagnosis, (b) YOD symptoms and illness progression, (c) disruptions in family or social relationships, (d) changes and strain in couples’ relationship, and (e) barriers to coping together as a couple. PWDs and CGs both experienced intense negative emotions of anger, grief, despair, and hopelessness (Castaño, 2020; Johannessen et al., 2018, 2019; Thorsen et al., 2020) related to the diagnosis and experienced the diagnosis as turning life “upside down” (Aslett et al., 2019; Hutchinson et al., 2020; Kilty et al., 2019; Pang & Lee, 2019). Both PWDs and CGs faced considerable difficulty accepting the progressive and ultimately terminal nature of the illness being diagnosed (Castaño, 2020; García-Toro et al., 2020; Johannessen et al., 2017; Pang & Lee, 2019), and endorsed challenges associated with obtaining information and understanding the expected disease trajectory (Aslett et al., 2019; García-Toro et al., 2020; Stamou et al., 2020; Werner et al., 2020). When considering the age of onset of symptoms and gravity of the diagnosis, many PWDs and CGs felt they “had a lot of future plans that [they] had to let go” (Millenaar et al., 2018), sometimes exacerbated by the feeling they were only just entering their “golden years” (Harding et al., 2018).

In terms of the symptom progression, both PWDs and CGs experienced the deterioration in the cognitive and behavioral abilities of the PWD as a stressor (Busted et al., 2020; Castaño, 2020; Johannessen et al., 2018; Thorsen et al., 2020). Both PWDs and CGs described the experience of observing potential signs of deterioration as stressful both due to the uncertainty of the future illness progression (Busted et al., 2020; Carone et al., 2016; Holthe et al., 2018; Pang & Lee, 2019) and the unpredictability of the day-to-day symptom presentation (Aslett et al., 2019; Busted et al., 2020; Castaño, 2020; García-Toro et al., 2020), as “difficulties were not reliably ever-present” (Harding et al., 2018) and the “fluctuation in good and bad days” was experienced as a “roller coaster” (Castaño, 2020). PWDs and CGs also both experienced stressors related to social relationships and support, including feelings of loneliness (García-Toro et al., 2020; Hutchinson et al., 2020; Thorsen et al., 2020; Werner et al., 2020) and social isolation (Busted et al., 2020; Evans, 2019; Hutchinson et al. 2020; Werner et al., 2020). For both members of the couple, “the social circle [was] kept at a distance” (Wawrziczny, Antoine, et al., 2016). Within dyads, PWDs and CGs faced changing roles and responsibilities, increasing relationship strain (Hutchinson et al., 2020; Pipon-Young et al., 2012) and a sense of disconnection (Oyebode et al., 2013; Wawrziczny, Antoine, et al., 2016). Relationship strain and disconnection were exacerbated by difficulties with communication (Aslett et al., 2019; Larochette et al., 2019; Pang & Lee, 2019; Stamou et al., 2020), discrepancies in recollections of experiences (Harding et al., 2018), disagreements over abilities and treatment needs of the PWD (Aslett et al., 2019; Harding et al., 2018; Johannessen et al., 2017; Wawrziczny, Pasquier, et al., 2016), and difficulty navigating both persons’ needs for independence (Aslett et al., 2019; Harding et al., 2018; Johannessen et al., 2017; Wawrziczny, Antoine, et al., 2016).

Theme 2: Unique Stressors of Persons With YOD and Informal CGs

We also identified a number of unique psychosocial stressors that are organized into the following subthemes: (a) initial impact of the diagnosis, (b) YOD symptoms and illness progression, (c) disruptions in family or social relationships, (d) loss, (e) increasing dependence and caregiving burden, and (f) navigating an uncertain future (Supplementary Table 2). For PWDs, many unique psychosocial stressors pertained to their firsthand experience of YOD, including confrontation with their mortality after receiving a diagnosis (Castaño, 2020; Clemerson et al., 2014; Johannessen & Möller, 2013), the devastation of losing the ability to communicate (Busted et al., 2020; Nichols et al., 2013), and feelings of uselessness and lack of purpose (Evans, 2019; Hutchinson et al., 2020; Johannessen et al., 2018, 2019). Feelings of uselessness and the “expanding experience of losing control” were reported as often provoking a sense of “existential anxiety” (Johannessen et al., 2018) for PWDs. For CGs, unique psychosocial stressors largely pertained to their experience of caregiving, including burden related to feeling constant worry for the PWD’s well-being (Arntzen et al., 2016; Cations et al., 2017; Flensner & Rudolfsson, 2018; Wawrziczny et al., 2017b) and the need to assume the full head of household responsibilities (Bakker et al., 2010; Gelman & Rhames, 2020; Oyebode et al., 2013). These increasing and shifting responsibilities sometimes led to feelings of “divided loyalties, and guilt” (Kilty et al., 2019), and gave rise to additional challenges finding personal time and engaging in self-care (Aslett et al., 2019; García-Toro et al., 2020; Hutchinson et al., 2020; Larochette et al., 2019).

For some subthemes, similar psychosocial stressors were experienced by PWDs and CGs, though for different reasons. For example, both PWDs and CGs experienced tremendous loss as a result of YOD. PWDs’ description of the experience of loss largely surrounded the loss of their identity (Busted et al., 2020; Castaño, 2020; Rabanal et al., 2018; Thorsen et al., 2020), work (Evans, 2019; Hutchinson et al., 2020; Johannessen et al., 2019; Mayrhofer, Mathie, et al., 2020), energy (Johannessen et al., 2018, 2019; Oyebode et al., 2013), and spirit (Johannessen & Möller, 2013; Pang & Lee, 2019; Thorsen et al., 2020), contributing to a “slow and painful loss of self” (Busted et al., 2020). For CGs, the experience of loss predominantly concerned the loss of a meaningful relationship with the PWD (Aslett et al., 2019; García-Toro et al., 2020; Gelman & Rhames, 2020; Millenaar et al., 2018). CGs described experiencing a number of painful losses in their relationship with the PWD, including loss of intimacy (Hoppe, 2018; Kimura et al., 2015; Oyebode et al., 2013; Roach et al., 2014) and meaningful conversation (Aslett et al., 2019; Nichols et al., 2013; Pang & Lee, 2019), leading CGs to feel that they had completely “lost their [partner] as an intimate person, parent of their children, a friend and partner in work and everyday life” (Wawrziczny et al., 2017b).

Theme 3: Common Adaptive Coping Strategies Used by Persons With YOD and Informal CGs to Manage Psychosocial Stressors

In addition to common psychosocial stressors, we also observed that many adaptive coping strategies were common among PWDs and CGs (Table 4). We organized the common coping strategies into the following subthemes: (a) avoidance and denial, (b) acceptance, (c) present focus, (d) individual and collaborative problem-solving, (e) social support, (f) cultivating positive emotions, (g) meaning making, (h) adaptive communication, and (i) interpersonal connection. Though most subthemes related to coping were described as adaptive, both PWDs and CGs described engaging in avoidance and denial as coping strategies, with some helpful and some harmful consequences.

Coping strategies related to avoidance and denial included using euphemisms to downplay the diagnosis (e.g., “memory problems”; Johannessen et al., 2018), concealing the diagnosis from friends and acquaintances (Castaño, 2020; Hutchinson et al., 2020; Johannessen et al., 2019; Werner et al., 2020), not thinking about the diagnosis (García-Toro et al., 2020; Hutchinson et al., 2016; Larochette et al., 2019; Svanberg et al., 2010), and detaching from one’s emotions regarding the diagnosis (García-Toro et al., 2020; Larochette et al., 2019; Lockeridge & Simpson, 2013; Svanberg et al., 2010). PWDs and CGs were motivated to adopt avoidant strategies in order to preserve normalcy and protect against stigma, “to be seen as ‘normal’, to be able to relate to others as usual, and diminish the impact of the disease” (Johannessen et al., 2018). The studies that examined PWDs and CGs together as a dyad also revealed how avoidance and concealment can be adopted by a dyad together, such as through avoiding discussing the diagnosis with each other (Lockeridge & Simpson, 2013; Wawrziczny, Pasquier, et al., 2016), or concealing the reality of YOD symptoms (Wawrziczny, Pasquier, et al., 2016) from each other. While avoidance and denial were cited as helpful in some contexts, many PWDs and CGs realized that these strategies served as barriers to adaptive coping, receipt of services, and planning for the future (Wawrziczny, Pasquier, et al., 2016). For many PWDs and CGs, acceptance and willingness to be open with friends and family were essential to cultivate in order to receive critical social support (Busted et al., 2020; Metcalfe et al., 2019; Thorsen et al., 2020; Werner et al., 2020).

PWDs and CGs described many other overlapping adaptive strategies for coping with the various challenges associated with YOD, including taking time to process one’s negative feelings and grief (Ducharme et al., 2013; Flensner & Rudolfsson, 2018; Johannessen & Möller, 2013; Van Rickstal et al., 2019), finding acceptance of the diagnosis (Castaño, 2020; García-Toro et al., 2020; Johannessen et al., 2019; Pang & Lee, 2019), taking a day-by-day approach (Busted et al., 2020; Castaño, 2020; Johannessen et al., 2019; Van Rickstal et al., 2019), and practicing gratitude and positivity (García-Toro et al., 2020; Larochette et al., 2019; Metcalfe et al., 2019; Thorsen et al., 2020). Studies examining PWDs and CGs together also identified dyadic adaptive coping strategies, including adopting a teamwork approach to problem-solving (Harding et al., 2018; Holthe et al., 2018; Wawrziczny et al., 2017b; Wawrziczny, Pasquier, et al., 2016), such as with respect to the “joint project of preserving a normal everyday life” (Holthe et al., 2018). A successful teamwork approach was facilitated by open communication (Stamou et al., 2020; Van Rickstal et al., 2019; Wawrziczny, Antoine, et al., 2016), willingness to adapt communication strategies to the PWD’s changing abilities (García-Toro et al., 2020; Kinney et al., 2011; Stamou et al., 2020), and a strong sense of togetherness (Flensner & Rudolfsson, 2018; Johannessen et al., 2016; Pang & Lee, 2019; Roach et al., 2016).

Theme 4: Unique Adaptive Coping Strategies Used by Persons With YOD and Informal CGs to Manage Psychosocial Stressors

We organized unique adaptive coping strategies into the following subthemes: (a) acceptance, (b) problem-solving, (c) cultivating positive emotions, (d) meaning making, and (e) social support/communication (Supplementary Table 3). PWDs emphasized the importance of preserving their autonomy (Busted et al., 2020; Clemerson et al., 2014; Evans, 2019; Johannessen et al., 2019) in terms of decision-making and engaging in activities that help them feel a sense of usefulness to others (Castaño, 2020; Sakamoto et al., 2017; Stamou et al., 2020; van Vliet et al., 2017). For example, participating in research studies or advocacy was often reported as a manner for PWDs to voice their story and seek recognition of “their continued presence as fellow human beings in society” (Sakamoto et al., 2017). For CGs, unique coping strategies related to the challenge of navigating the PWD’s deterioration, including remembering the illness as the reason for any problematic behaviors (Bakker et al., 2010; Hutchinson et al., 2016; Millenaar et al., 2018; Nichols et al., 2013) and learning how to avoid provoking irritation in the PWD (Harding et al., 2018; Johannessen et al., 2017; Svanberg et al., 2010; Wawrziczny, Pasquier, et al., 2016). CGs reported some strategies for cultivating patience and compassion toward PWDs, including “reminiscing about old memories” and “directing the focus of [interactions] to pleasant topics that lacked conflict” (Nichols et al., 2013). Finally, CGs emphasized the importance of finding breaks from caregiving (Flensner & Rudolfsson, 2018; Johannessen et al., 2017; Larochette et al., 2019; Wawrziczny et al., 2017b), especially in order to solicit social and emotional support.

Discussion

We conducted the first meta-synthesis (60 qualitative studies) to comprehensively characterize both common and unique stressors and adaptive coping strategies of PWDs and CGs. Results illustrate the many complex psychosocial stressors experienced by both PWDs and CGs following a YOD diagnosis, and accordingly support the importance of developing psychosocial resources for PWDs and CGs with YOD diagnoses. Our meta-synthesis findings reveal that both PWDs and CGs experience intense negative emotions after diagnosis, challenges navigating the PWD’s progressive symptoms, and feelings of loneliness and stigmatization. A large body of quantitative research has demonstrated the negative impacts of these stressors on both PWDs and CGs (Cations et al., 2017; Spreadbury & Kipps, 2019a).

We also found a wealth of data to support the fact that both PWDs and CGs have the ability to engage in adaptive coping strategies to help manage the stressors they experience following YOD diagnosis. This evidence thus supports the feasibility of the development of dyadic interventions to support the PWD and CG as a unit. Our meta-synthesis findings reveal that adaptive coping strategies including finding acceptance, seeking social support, cultivating gratitude and optimism, and problem-solving are helpful for both PWDs and CGs. Our finding that these coping strategies are used by PWDs themselves is particularly important, given that the majority of support resources for YOD are geared toward CGs, with limited psychosocial interventions focusing on the positive adjustment and coping of PWDs. This review’s nuanced presentation of the common and unique stressors and coping strategies for PWDs and CGs can directly inform dyadic interventions aimed at teaching skills to decrease emotional distress, improve adjustment to the uncertain symptom trajectory, and optimize quality of life for both PWD and CGs.

Although our review highlights that CGs and PWD can both engage in adaptive coping, the high rates of emotional distress and CG burden observed in this population (Spreadbury & Kipps, 2019a) suggest that the coping strategies adopted by some PWDs and CGs are not sufficiently enabling them to manage the immense psychosocial stressors they face. There are many barriers to adjustment and adaptive coping that must be surmounted, including cognitive and behavioral challenges in PWDs, the ever-changing circumstances resulting from the progressive decline of PWDs, time and resource constraints for CGs, and the overall disruption in family structure and responsibilities that are brought on by YOD diagnoses (Millenaar et al., 2016; Spreadbury & Kipps, 2019b). Psychosocial interventions provided for PWDs and CGs early after diagnosis have the potential to aid PWDs and CGs in overcoming these barriers to develop adaptive coping skills to facilitate adjustment and decrease emotional distress and CG burden throughout the course of the illness progression.

Given that the majority of stressors and coping strategies identified across studies were common to both PWDs and CGs, our findings suggest that a dyadic framework may be the best approach to psychosocial interventions in this population. Dyadic interventions where PWDs and CGs participate together allow for adaptive coping skills to be taught to both members of the dyad at the same time, which is efficient and cost-effective. Further, such approaches allow skills related specifically to the relationship (e.g., interpersonal effectiveness, communication skills, and collaborative problem-solving) to be taught to both members of the dyad simultaneously. These skills are necessary for PWDs and CGs to navigate challenging conversations related to care planning and financial and legal decision-making, and to cope with the PWD’s progression of symptoms and loss of independent function. Because some stressors are experienced uniquely by PWDs and CGs, a dyadic intervention can also promote understanding and empathy within dyads, to support the maintenance of partnership over the course of the YOD experience. Dyadic interventions delivered early after diagnoses when PWDs still have the ability to meaningfully participate have the potential to dramatically improve quality of life in PWD–CG dyads.

Limitations

Our meta-synthesis was limited by the available qualitative literature, and not all findings may be transferable to the experiences of diverse groups of PWDs and CGs living with YOD. Study samples were predominantly White, and the subthemes identified herein may not fully represent the stressors and coping strategies of more diverse groups of PWDs and CGs. Further, very few (N = 3) studies employed a dyadic approach to studying PWD and CG experiences. This implies the need for more studies that focus on dyadic adjustment to YOD.

Implications and Directions for Future Research

The psychosocial stressors and adaptive coping strategies identified in our review can be used to develop psychosocial interventions to support dyads in adjusting to YOD diagnoses and navigating stress and distress in the postdiagnosis period. Stress and coping frameworks have been employed to understand how patients with chronic and life-limiting neurological illnesses (e.g., late-onset dementia, stroke, moderate–severe traumatic brain injury) and their informal CGs cope with persistent challenges. Though such approaches have yet to be used with PWDs and CGs with YOD, they have served as the basis of evidence-based dyadic interventions that prevent emotional distress in both members of dyads (Badr et al., 2019; Bannon et al., 2020; Moon & Adams, 2013; Vranceanu et al., 2020).

In order to support the development of dyadic psychosocial interventions for YOD, additional high-quality qualitative research is needed to better understand: (a) dyadic patterns of stress and coping in the initial postdiagnosis period and adjustment to diagnosis over time, (b) ways in which PWDs and CGs identify and engage in adaptive coping strategies for specific psychosocial stressors, (c) PWD and CG needs and preferences for psychosocial interventions, (d) barriers and facilitators to participation in psychosocial interventions, and (e) individual and dyadic factors that may contribute to the feasibility, acceptability, and utility of psychosocial interventions in YOD. Future studies should also be careful to provide sufficient demographic and descriptive details regarding included participants and to prioritize recruitment and enrollment of individuals from diverse backgrounds.

Conclusion

This meta-synthesis integrated available qualitative evidence on the psychosocial stressors and adaptive coping strategies of PWDs and CGs after a diagnosis of YOD and presented the integrated findings in a novel manner to highlight stressors and coping strategies that are both common and unique among PWDs and CGs. Through our use of the stress and coping framework as well as our dyadic lens, this meta-synthesis generated invaluable data to inform future research and clinical interventions for PWD-CG dyads navigating YOD.

Supplementary Material

Funding

This study was funded by grants 5R21 NR017979 and 3R21 NR01797902-S1 from National Institute of Nursing Research and National Institute of Aging to Ana-Maria Vranceanu.

Conflict of Interest

A.-M. Vranceanu reports serving on the Scientific Advisory Board for the Calm application outside of the submitted work. She also reports research support from NIH, NF-Midwest, NF-Texas, NF-Northeast, and royalties from Oxford University Press. B. C. Dickerson reports research support from NIH, Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation, consulting for Acadia, Arkuda, Axovant, Lilly, Biogen, Merck, Novartis, Wave LifeSciences, editorial duties with payment for Elsevier (Neuroimage: Clinical and Cortex), and royalties from Oxford University Press and Cambridge University Press. All other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Arntzen, C., Holthe, T., & Jentoft, R. (2016). Tracing the successful incorporation of assistive technology into everyday life for younger people with dementia and family carers. Dementia, 15(4), 646–662. doi: 10.1177/1471301214532263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aslett, H. J., Huws, J. C., Woods, R. T., & Kelly-Rhind, J. (2019). “This is Killing me Inside”: The impact of having a parent with young-onset dementia. Dementia, 18(3), 1089–1107. doi: 10.1177/1471301217702977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badr, H., Bakhshaie, J., & Chhabria, K. (2019). Dyadic interventions for cancer survivors and caregivers: State of the science and new directions. Seminars in Oncology Nursing, 35(4), 337–341. doi: 10.1016/j.soncn.2019.06.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakker, C., de Vugt, M. E., Vernooij-Dassen, M., van Vliet, D., Verhey, F. R., & Koopmans, R. T. (2010). Needs in early onset dementia: A qualitative case from the NeedYD study. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Dementias, 25(8), 634–640. doi: 10.1177/1533317510385811 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bang, J., Spina, S., & Miller, B. L. (2015). Frontotemporal dementia. Lancet, 386(10004), 1672–1682. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00461-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bannon, S., Lester, E. G., Gates, M. V., McCurley, J., Lin, A., Rosand, J., & Vranceanu, A. M. (2020). Recovering together: Building resiliency in dyads of stroke patients and their caregivers at risk for chronic emotional distress; A feasibility study. Pilot and Feasibility Studies, 6(1), 75. doi: 10.1186/s40814-020-00615-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biggs, A., Brough, P., & Drummond, S. (2017). Lazarus and Folkman’s psychological stress and coping theory. In C. L. Cooper & J. C. Quick (Eds.), The handbook of stress and health: A guide to research and practice (pp. 351–364). Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Busted, L. M., Nielsen, D. S., & Birkelund, R. (2020). “Sometimes it feels like thinking in syrup”—The experience of losing sense of self in those with young onset dementia. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being, 15(1), 1734277. doi: 10.1080/17482631.2020.1734277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carone, L., Tischler, V., & Dening, T. (2016). Football and dementia: A qualitative investigation of a community based sports group for men with early onset dementia. Dementia, 15(6), 1358–1376. doi: 10.1177/1471301214560239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castaño, E. (2020). Discourse analysis as a tool for uncovering the lived experience of dementia: Metaphor framing and well-being in early-onset dementia narratives. Discourse & Communication, 14(2), 115–132. doi: 10.1177/1750481319890385 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cations, M., Withall, A., Horsfall, R., Denham, N., White, F., Trollor, J., Loy, C., Brodaty, H., Sachdev, P., Gonski, P., Demirkol, A., Cumming, R. G., & Draper, B. (2017). Why aren’t people with young onset dementia and their supporters using formal services? Results from the INSPIRED study. PLoS ONE, 12(7), e0180935. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0180935 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clemerson, G., Walsh, S., & Isaac, C. (2014). Towards living well with young onset dementia: An exploration of coping from the perspective of those diagnosed. Dementia, 13(4), 451–466. doi: 10.1177/1471301212474149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Critical Skills Appraisal Programme . (2018). CASP qualitative checklist. https://casp-uk.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/CASP-Qualitative-Checklist-2018_fillable_form.pdf

- Dourado, M. C. N., Laks, J., Kimura, N. R., Baptista, M. a. T., Barca, M. L., Engedal, K., Tveit, B., & Johannessen, A. (2018). Young-onset Alzheimer dementia: A comparison of Brazilian and Norwegian carers’ experiences and needs for assistance. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 33(6), 824–831. doi: 10.1002/gps.4717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ducharme, S., & Dickerson, B. C. (2015). The neuropsychiatric examination of the young-onset dementias. The Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 38(2), 249–264. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2015.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ducharme, F., Kergoat, M. J., Antoine, P., Pasquier, F., & Coulombe, R. (2013). The unique experience of spouses in early-onset dementia. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Dementias, 28(6), 634–641. doi: 10.1177/1533317513494443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ducharme, F., Kergoat, M. J., Coulombe, R., Lévesque, L., Antoine, P., & Pasquier, F. (2014). Unmet support needs of early-onset dementia family caregivers: A mixed-design study. BMC Nursing, 13(1), 49. doi: 10.1186/s12912-014-0049-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans, D. (2019). An exploration of the impact of younger-onset dementia on employment. Dementia, 18(1), 262–281. doi: 10.1177/1471301216668661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falconier, M. K., & Kuhn, R. (2019). Dyadic coping in couples: A conceptual integration and a review of the empirical literature. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 571. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00571 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flensner, G., & Rudolfsson, G. (2018). A pathway towards reconciliation and wellbeing. Nordisk Sygeplejeforskning, 8(02), 136–149. doi: 10.18261/issn.1892-2686-2018-02-05 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Flynn, R., & Mulcahy, H. (2013). Early-onset dementia: The impact on family care-givers. British Journal of Community Nursing, 18(12), 598–606. doi: 10.12968/bjcn.2013.18.12.598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Toro, M., Sánchez-Gómez, M. C., Madrigal Zapata, L., & Lopera, F. J. (2020). “In the flesh”: Narratives of family caregivers at risk of early-onset familial Alzheimer’s disease. Dementia, 19(5), 1474–1491. doi: 10.1177/1471301218801501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelman, C., & Rhames, K. (2020). “I have to be both mother and father”: The impact of young-onset dementia on the partner’s parenting and the children’s experience. Dementia, 19(3), 676–690. doi: 10.1177/1471301218783542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giebel, C., Eastham, C., Cannon, J., Wilson, J., Wilson, J., & Pearson, A. (2020). Evaluating a young-onset dementia service from two sides of the coin: Staff and service user perspectives. BMC Health Services Research, 20(187). doi: 10.1186/s12913-020-5027-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood, N., & Smith, R. (2016). The experiences of people with young-onset dementia: A meta-ethnographic review of the qualitative literature. Maturitas, 92, 102–109. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2016.07.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding, E., Sullivan, M. P., Woodbridge, R., Yong, K. X. X., McIntyre, A., Gilhooly, M. L., Gilhooly, K. J., & Crutch, S. J. (2018). “Because my brain isn’t as active as it should be, my eyes don’t always see”: A qualitative exploration of the stress process for those living with posterior cortical atrophy. BMJ Open, 8(2), e018663. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewitt, P., Watts, C., Hussey, J., Power, K., & Williams, T. (2013). Does a structured gardening programme improve well-being in young-onset dementia? A preliminary study. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 76(8), 355–361. doi: 10.4276/030802213X13757040168270 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Holthe, T., Jentoft, R., Arntzen, C., & Thorsen, K. (2018). Benefits and burdens: Family caregivers’ experiences of assistive technology (AT) in everyday life with persons with young-onset dementia (YOD). Disability and Rehabilitation. Assistive Technology, 13(8), 754–762. doi: 10.1080/17483107.2017.1373151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoppe, S. (2018). A sorrow shared is a sorrow halved: The search for empathetic understanding of family members of a person with early-onset dementia. Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry, 42(1), 180–201. doi: 10.1007/s11013-017-9549-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchinson, K., Roberts, C., Kurrle, S., & Daly, M. (2016). The emotional well-being of young people having a parent with younger onset dementia. Dementia, 15(4), 609–628. doi: 10.1177/1471301214532111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchinson, K., Roberts, C., Roach, P., & Kurrle, S. (2020). Co-creation of a family-focused service model living with younger onset dementia. Dementia, 19(4), 1029–1050. doi: 10.1177/1471301218793477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jentoft, R., Holthe, T., & Arntzen, C. (2014). The use of assistive technology in the everyday lives of young people living with dementia and their caregivers. Can a simple remote control make a difference? International Psychogeriatrics, 26(12), 2011–2021. doi: 10.1017/S1041610214001069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johannessen, A., Engedal, K., Haugen, P. K., Dourado, M. C. N., & Thorsen, K. (2018). “To be, or not to be”: Experiencing deterioration among people with young-onset dementia living alone. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being, 13(1), 1490620. doi: 10.1080/17482631.2018.1490620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johannessen, A., Engedal, K., Haugen, P. K., Dourado, M. C., & Thorsen, K. (2019). Coping with transitions in life: A four-year longitudinal narrative study of single younger people with dementia. Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare, 12, 479–492. doi: 10.2147/JMDH.S208424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johannessen, A., Engedal, K., & Thorsen, K. (2016). Family carers of people with young-onset dementia: Their experiences with the supporter service. Geriatrics, 1(4). doi: 10.3390/geriatrics1040028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johannessen, A., Helvik, A. S., Engedal, K., & Thorsen, K. (2017). Experiences and needs of spouses of persons with young-onset frontotemporal lobe dementia during the progression of the disease. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 31(4), 779–788. doi: 10.1111/scs.12397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johannessen, A., & Möller, A. (2013). Experiences of persons with early-onset dementia in everyday life: A qualitative study. Dementia, 12(4), 410–424. doi: 10.1177/1471301211430647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilty, C., Boland, P., Goodwin, J., & de Róiste, Á. (2019). Caring for people with young onset dementia: An interpretative phenomenological analysis of family caregivers’ experiences. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing and Mental Health Services, 57(11), 37–44. doi: 10.3928/02793695-20190821-02 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura, N. R. S., Maffioletti, V. L. R., Santos, R. L., Baptista, M. A. T., & Dourado, M. C. N. (2015). Psychosocial impact of early onset dementia among caregivers. Trends in Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, 37(4), 213–219. doi: 10.1590/2237-6089-2015-0038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinney, J. M., Kart, C. S., & Reddecliff, L. (2011). ‘That’s me, the Goother’: Evaluation of a program for individuals with early-onset dementia. Dementia, 10(3), 361–377. doi: 10.1177/1471301211407806 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Larochette, C., Wawrziczny, E., Papo, D., Pasquier, F., & Antoine, P. (2019). An acceptance, role transition, and couple dynamics-based program for caregivers: A qualitative study of the experience of spouses of persons with young-onset dementia. Dementia. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1177/1471301219854643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. Springer Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Lockeridge, S., & Simpson, J. (2013). The experience of caring for a partner with young onset dementia: How younger carers cope. Dementia, 12(5), 635–651. doi: 10.1177/1471301212440873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayrhofer, A. M., Mathie, E., McKeown, J., Goodman, C., Irvine, L., Hall, N., & Walker, M. (2020). Young onset dementia: Public involvement in co-designing community-based support. Dementia, 19(4), 1051–1066. doi: 10.1177/1471301218793463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayrhofer, A. M., Shora, S., Tibbs, M. A., Russell, S., Littlechild, B., & Goodman, C. (2020). Living with young onset dementia: Reflections on recent developments, current discourse, and implications for policy and practice. Ageing & Society, 1–9. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X20000422 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mendez, M. F. (2019). Early-onset Alzheimer disease and its variants. Continuum, 25(1), 34–51. doi: 10.1212/CON.0000000000000687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metcalfe, A., Jones, B., Mayer, J., Gage, H., Oyebode, J., Boucault, S., Aloui, S., Schwertel, U., Böhm, M., Tezenas du Montcel, S., Lebbah, S., De Mendonça, A., De Vugt, M., Graff, C., Jansen, S., Hergueta, T., Dubois, B., & Kurz, A. (2019). Online information and support for carers of people with young-onset dementia: A multi-site randomised controlled pilot study. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 34(10), 1455–1464. doi: 10.1002/gps.5154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millenaar, J. K., Bakker, C., Koopmans, R. T. C. M., Verhey, F. R. J., Kurz, A., & de Vugt, M. E.. (2016). The care needs and experiences with the use of services of people with young-onset dementia and their caregivers: A systematic review. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 31(12), 1261–1276. doi: 10.1002/gps.4502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millenaar, J. K., Bakker, C., van Vliet, D., Koopmans, R. T. C. M., Kurz, A., Verhey, F. R. J., & de Vugt, M. E. (2018). Exploring perspectives of young onset dementia caregivers with high versus low unmet needs. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 33(2), 340–347. doi: 10.1002/gps.4749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millenaar, J. K., van Vliet, D., Bakker, C., Vernooij-Dassen, M. J., Koopmans, R. T., Verhey, F. R., & de Vugt, M. E. (2014). The experiences and needs of children living with a parent with young onset dementia: Results from the NeedYD study. International Psychogeriatrics, 26(12), 2001–2010. doi: 10.1017/S1041610213001890 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G., & Group, T. P. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine, 6(7), e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moon, H., & Adams, K. B. (2013). The effectiveness of dyadic interventions for people with dementia and their caregivers. Dementia, 12(6), 821–839. doi: 10.1177/1471301212447026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols, K. R., Fam, D., Cook, C., Pearce, M., Elliot, G., Baago, S., Rockwood, K., & Chow, T. W. (2013). When dementia is in the house: Needs assessment survey for young caregivers. The Canadian Journal of Neurological Sciences, 40(1), 21–28. doi: 10.1017/s0317167100012907 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oyebode, J. R., Bradley, P., & Allen, J. L. (2013). Relatives’ experiences of frontal-variant frontotemporal dementia. Qualitative Health Research, 23(2), 156–166. doi: 10.1177/1049732312466294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pang, R. C., & Lee, D. T. (2019). Finding positives in caregiving: The unique experiences of Chinese spousal caregivers of persons with young-onset dementia. Dementia, 18(5), 1615–1628. doi: 10.1177/1471301217724026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pipon-Young, F. E., Lee, K. M., Jones, F., & Guss, R. (2012). I’m not all gone, I can still speak: The experiences of younger people with dementia. An action research study. Dementia, 11(5), 597–616. doi: 10.1177/1471301211421087 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rabanal, L. I., Chatwin, J., Walker, A., O’Sullivan, M., & Williamson, T. (2018). Understanding the needs and experiences of people with young onset dementia: A qualitative study. BMJ Open, 8(10), e021166. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-021166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie, L., Tolson, D., & Danson, M. (2018). Dementia in the workplace case study research: Understanding the experiences of individuals, colleagues and managers. Ageing & Society, 38(10), 2146–2175. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X17000563 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roach, P., & Drummond, N. (2014). ‘It’s nice to have something to do’: Early-onset dementia and maintaining purposeful activity. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 21(10), 889–895. doi: 10.1111/jpm.12154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roach, P., Drummond, N., & Keady, J. (2016). ‘Nobody would say that it is Alzheimer’s or dementia at this age’: Family adjustment following a diagnosis of early-onset dementia. Journal of Aging Studies, 36, 26–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jaging.2015.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roach, P., Keady, J., Bee, P., & Williams, S. (2014). ‘We can’t keep going on like this’: Identifying family storylines in young onset dementia. Ageing & Society, 34(8), 1397–1426. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X13000202 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson, J., & Evans, D. (2015). Evaluation of a workplace engagement project for people with younger onset dementia. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 24(15–16), 2331–2339. doi: 10.1111/jocn.12852 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rostad, D., Hellzén, O., & Enmarker, I. (2013). The meaning of being young with dementia and living at home. Nursing Reports, 3(1), e3. doi: 10.4081/nursrep.2013.e3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sakamoto, M. L., Moore, S. L., & Johnson, S. T. (2017). “I’m Still Here”: Personhood and the early-onset dementia experience. Journal of Gerontological Nursing, 43(5), 12–17. doi: 10.3928/00989134-20170309-01 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sapolsky, D., Domoto-Reilly, K., Negreira, A., Brickhouse, M., McGinnis, S., & Dickerson, B. C. (2011). Monitoring progression of primary progressive aphasia: Current approaches and future directions. Neurodegenerative Disease Management, 1(1), 43–55. doi: 10.2217/nmt.11.2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Spreadbury, J. H., & Kipps, C. M. (2019a). Measuring younger onset dementia: A comprehensive literature search of the quantitative psychosocial research. Dementia, 18(1), 135–156. doi: 10.1177/1471301216661427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spreadbury, J. H., & Kipps, C. (2019b). Measuring younger onset dementia: What the qualitative literature reveals about the ‘lived experience’ for patients and caregivers. Dementia, 18(2), 579–598. doi: 10.1177/1471301216684401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stamou, V., Fontaine, J. L., O’Malley, M., Jones, B., Gage, H., Parkes, J., Carter, J., & Oyebode, J. (2020). The nature of positive post-diagnostic support as experienced by people with young onset dementia. Aging & Mental Health, 1–9. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2020.1727854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svanberg, E., Stott, J., & Spector, A. (2010). ‘Just helping’: Children living with a parent with young onset dementia. Aging & Mental Health, 14(6), 740–751. doi: 10.1080/13607861003713174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorsen, K., Dourado, M. C. N., & Johannessen, A. (2020). Developing dementia: The existential experience of the quality of life with young-onset dementia—A longitudinal case study. Dementia, 19(3), 878–893. doi: 10.1177/1471301218789990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Rickstal, R., De Vleminck, A., Aldridge, M. D., Morrison, S. R., Koopmans, R. T., van der Steen, J. T., Engelborghs, S., & Van den Block, L. (2019). Limited engagement in, yet clear preferences for advance care planning in young-onset dementia: An exploratory interview-study with family caregivers. Palliative Medicine, 33(9), 1166–1175. doi: 10.1177/0269216319864777 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Vliet, D., Persoon, A., Bakker, C., Koopmans, R. T. C. M., de Vugt, M. E., Bielderman, A., & Gerritsen, D. L. (2017). Feeling useful and engaged in daily life: Exploring the experiences of people with young-onset dementia. International Psychogeriatrics, 29(11), 1889–1898. doi: 10.1017/S1041610217001314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vranceanu, A. M., Bannon, S., Mace, R., Lester, E., Meyers, E., Gates, M., Popok, P., Lin, A., Salgueiro, D., Tehan, T., Macklin, E., & Rosand, J. (2020). Feasibility and efficacy of a resiliency intervention for the prevention of chronic emotional distress among survivor-caregiver dyads admitted to the neuroscience intensive care unit: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Network Open, 3(10), e2020807. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.20807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh, D., & Downe, S. (2005). Meta-synthesis method for qualitative research: A literature review. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 50(2), 204–211. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03380.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wawrziczny, E., Antoine, P., Ducharme, F., Kergoat, M. J., & Pasquier, F. (2016). Couples’ experiences with early-onset dementia: An interpretative phenomenological analysis of dyadic dynamics. Dementia, 15(5), 1082–1099. doi: 10.1177/1471301214554720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wawrziczny, E., Pasquier, F., Ducharme, F., Kergoat, M. J., & Antoine, P. (2016). From “needing to know” to “needing not to know more”: An interpretative phenomenological analysis of couples’ experiences with early-onset Alzheimer’s disease. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 30(4), 695–703. doi: 10.1111/scs.12290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wawrziczny, E., Pasquier, F., Ducharme, F., Kergoat, M. J., & Antoine, P. (2017a). Do spouse caregivers of persons with early- and late-onset dementia cope differently? A comparative study. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 69, 162–168. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2016.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wawrziczny, E., Pasquier, F., Ducharme, F., Kergoat, M. J., & Antoine, P. (2017b). Do spouse caregivers of young and older persons with dementia have different needs? A comparative study. Psychogeriatrics, 17(5), 282–291. doi: 10.1111/psyg.12234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner, P., Shpigelman, C. N., & Raviv Turgeman, L. (2020). Family caregivers’ and professionals’ stigmatic experiences with persons with early-onset dementia: A qualitative study. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 34(1), 52–61. doi: 10.1111/scs.12704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong, B., Lucente, D. E., MacLean, J., Padmanabhan, J., Quimby, M., Brandt, K. D., Putcha, D., Sherman, J., Frosch, M. P., McGinnis, S., & Dickerson, B. C. (2019). Diagnostic evaluation and monitoring of patients with posterior cortical atrophy. Neurodegenerative Disease Management, 9(4), 217–239. doi: 10.2217/nmt-2018-0052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.