ABSTRACT

Breast cancer, the most frequent disease amongst women worldwide, accounts for the highest cancer-related mortality rate. Triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) subtype encompasses ~15% of all breast cancers and lack estrogen, progesterone, and HER2 receptors. Although risk factors for breast cancer are well-known, factors underpinning breast cancer onset and progression remain unknown. Recent studies suggest the plausible role of oncoviruses including human papillomaviruses (HPVs), Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), and mouse mammary tumor virus (MMTV) in breast cancer pathogenesis. However, the role of these oncoviruses in TNBC is still unclear. In the current study, we explored the status of high-risk HPVs, EBV, and MMTV in a well-defined TNBC cohort from Croatia in comparison to 16 normal/non TNBC samples (controls) using polymerase chain reaction assay. We found high-risk HPVs and EBV present in 37/70 (53%) and 25/70 (36%) of the cases, respectively. The most common HPV types are 52, 45, 31, 58 and 68. We found 16% of the samples positive for co-presence of high-risk HPVs and EBV. Moreover, our data revealed that 5/70 (7%) samples are positive for MMTV. In addition, only 2/70 (3%) samples had co-presence of HPVs, EBV, and MMTV without any significant association with the clinicopathological variables. While, 6/16 (37.5%) controls were positive for HPV (p = .4), EBV was absent in all controls (0/16, 0%) (p = .01). In addition, we did not find the co-presence of the oncoviruses in the controls (p > .05). Nevertheless, further investigations are essential to understand the underlying mechanisms of multiple-oncogenic viruses’ interaction in breast carcinogenesis, especially TNBC.

KEYWORDS: Triple-negative breast cancer, Epstein–Barr virus, human papillomavirus, mouse mammary tumor virus

Introduction

Breast cancer is the second most common cancer worldwide, and it affects more than two million women accounting for around half a million deaths annually.1 Breast cancer is classified into four molecular subtypes (Luminal A, Luminal B, HER2+ and triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC);2,3 of which the TNBC subtype accounts for around 12–17% of all breast cancer cases.4 TNBC is one of the most aggressive subtypes4,5 and lacks hormonal expression of estrogen and progesterone (ER and PR) as well as HER-2/neu receptor.6 In addition, TNBC frequently affects younger patients and is characterized by high tumor grade, advanced stage, and higher Ki-67 proliferative index.7,8

Along with environmental and genetic factors, it is estimated that around 20% of human cancers are associated with infectious agents, including oncoviruses, especially high-risk human papillomaviruses (HPVs), Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), mouse mammary tumor virus (MMTV) and human mammary tumor virus (HMTV) which can be plausibly involved in the onset and progression of different types of human carcinomas.9–13

HPV, a small epitheliotropic, non-enveloped, double-stranded DNA virus, infects the epithelial cells (epidermal or mucosal) and can prompt neoplastic transformation (both benign and malignant) of infected cells.14,15 The HPV genome consists of eight open reading frames (ORFs) and is divided into three functional elements (the early (E), and late (L) regions, and a long control region (LCR)).16 While the L region encodes the structural proteins (L1-L2) and is involved in virus assembly,16 the high-risk HPV early proteins (E5, E6, and E7) act as oncogenes and modulate molecular mechanisms of infected cells, including the deregulation of epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) biomarkers.17,18 Indeed, various studies have reported the etiological role of HPVs in head and neck,19 cervical,20 bladder,21 and breast22 carcinomas.

Likewise, EBV, a double-stranded DNA gamma-herpes virus, infects 90% of the adult population.23,24 The EBV genome spans over 184-kbp and encodes over 85 genes including viral oncogenes such as six EBV-encoded nuclear antigens (EBNA1, −2, −3A, −3B, −3 C and -LP) and latent membrane proteins (LMP1, −2A, and −2B) in addition to numerous noncoding RNAs (EBERs and miRNAs).24 EBV infection is involved in the onset of various epithelial carcinomas, comprising nasopharyngeal (NPC), breast, cervical, and gastric cancer.25 EBNA1 and LMP1 are considered oncogenic proteins of EBV that can induce cellular proliferation and motility, inhibit apoptosis and, enhance cell invasion and angiogenesis.26,27

On the other hand, the mouse mammary tumor virus (MMTV) belongs to the Betaretroviridae family28 and is presently considered a frequent etiologic causal factor for T-cell lymphomas and breast cancer in mice.29,30 Earlier studies identified homologous antigens and sequences to MMTV, known as MMTV-like sequences in human biological samples, including breast milk,31 saliva,32 and peripheral blood lymphoid cells.33 Similar to the role of MMTV in the onset of tumors (lymphomas, renal adenocarcinoma, salivary gland, and mammary tumors) in mice,34 MMTV-like virus was detected in biliary cirrhosis as well as in various human cancers, including lymphoma, endometrial, liver, ovary, prostate, skin, lung and breast.12,13 However, the role of MMTV in these cancers is not clearly defined yet.

Earlier investigations have indicated the presence/co-presence of high-risk HPVs, EBV, and MMTV-like virus in human breast cancer worldwide.35–38 However, a few studies failed to detect the presence of these oncoviruses in human breast cancer as well as normal mammary tissues.39–41 Based on previous reports depicting the role of HPVs, EBV, and MMTV-like virus in the initiation of various cancers, comprising breast,19,30,36–38,42–45 we explored the presence/co-presence of high-risk HPVs, EBV, and MMTV-like virus in TNBC samples in Croatian women.

Materials and methods

Sample collection and DNA extraction

The study included 72 formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue samples initially diagnosed as TNBC at the Ljudevit Jurak Clinical Department of Pathology and Cytology, Sestre milosrdnice University Hospital Center, Zagreb, Croatia.

All cases were negative for estrogen receptor (ER; clone EP1, Dako), progesterone receptor (PR; clone 636, Dako), and HER-2/neu receptor (Hercep Test, monoclonal Rabbit, anti-Human; HER2 protein, Dako). ER, PR and HER-2/neu were scored using the ASCO/CAP guidelines.46,47 The tumors were graded following the Nottingham Histologic Score system .48

In addition, fourteen normal/benign breast tissues from another breast cohort were used for comparison.49 For the study, all cases were de-identified and patients’ information anonymized. A local ethical committee (institutional review board) of the Sestre Milosrdnice University Hospital Center approved the study (number of approval: EP-13659/21-11).

Before molecular assays, all cases were re-reviewed by a board-certified pathologist (S.V.) to confirm the diagnosis and select appropriate FFPEs for PCR assays.

DNA was extracted from FFPE tissue samples using the Thermo Scientific GeneJET FFPE DNA Purification Kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (ThermoFisher Scientific, USA) and as previously described.36 Briefly, FFPE sections underwent enzymatic digestion using 200 µl of digestion buffer followed by lysing and release of genomic DNA using Proteinase K solution (20 µl); the DNA was de-crosslinked by heat incubation (90°C) for 40 min. The supernatant containing DNA was obtained from the solution and mixed with 200 µl binding buffer followed by the addition of ethanol (96%); the lysate was loaded onto the purification column, then, adsorbed DNA was washed (wash Buffers 1 and 2) to eliminate contaminants and finally eluted with elution buffer (60 µl).

Polymerase chain reaction analysis

Purified genomic DNA from each sample was analyzed for HPVs, EBV, and MMTV-like virus by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using specific primers for high-risk HPV types: 16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, 66 and 68 as well as EBNA1, EBNA2 (Forward primer: 5′-AGGGATGCCTGGACACAAGA-3′ and Reverse primer: 5′-TTGTGACAGAGGTGACAAAA-3′) and LMP1 of EBV as previously described.50,51 In addition, PCR was performed for MMTV (Forward primer: 5′-GATGGTATGAAGCAGGATGG-3′ and Reverse primer: 5′-CCTCTTTTCTCTATATCTATTAGCTGAGGTAATC-3′). GAPDH was used as an internal control. All the primers and analyses were performed as previously described.49 In each experiment, negative control (instead of DNA, nuclease-free water) and positive control (HPV: HeLa cell line for L1 region52 and normal oral epithelial (NOE) cell line expressing E6/E7 of HPV type 16 for E6/E7 region;53 EBV: Diluted DNA plasmids for EBNA1, EBNA2, and LMP1 of EBV; MMTV-like virus: MDA-MB-23154) were used.

PCR was performed using the Invitrogen Platinum II Hot-Start Green PCR Master Mix (2X) (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Briefly, HPV and EBV genes were amplified for an initial denaturation at 94°C for 2 min followed by 40 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, annealing at temperatures ranging from 50°C to 62°C for 30 s depending on each primer’s melting temperature as previously described,50,51 and 72°C for 30 s. In parallel, EBNA2 and MMTV-like virus genes were amplified for an initial denaturation at 94°C for 2 min followed by 40 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 54°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 30 s. The samples were finally incubated for 10 min at 72°C for a final extension. The PCR product from each exon was resolved using 1.5% agarose gel electrophoresis.

The samples expressing all three oncoproteins, EBNA1, EBNA2, and LMP1, were taken into consideration to determine EBV positivity in our cohort.

Statistical analysis

GraphPad Prism software (version 8.4.3) was used to carry out all the statistical and plotting of graphs. To assess the significance of HPVs, EBV, and MMTV-like virus associations with clinicopathological data (Nottingham histological grade, tumor stage, and lymph node involvement) in correlation with the presence/co-presence of these oncoviruses, we utilized Chi-square (χ2) test with Yates’ correction and Fisher’s exact test. The results were considered statistically significant if p-values were ≤0.05 in two-tailed tests.

Results

Clinicopathological characteristics of the cohort

The clinicopathological characteristics of the TNBC cohort are summarized in Table 1. The mean age of all patients is 62.4 years (standard deviation (SD), ±14.7 years).

Table 1.

Clinicopathological characteristics of patients with triple-negative breast cancer (n = 70)

| Characteristic | Categories | Number (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ≤50 | 18 (25%) |

| >50 | 53 (74%) | |

| Unknown | 1 (1%) | |

| Nottingham Histological Grade | I | 0 (0%) |

| II | 11 (16%) | |

| III | 59 (84%) | |

| Tumor (pT) Stage | pT1 | 22 (31%) |

| pT2 | 34 (49%) | |

| pT3 | 4 (6%) | |

| pT4 | 9 (13%) | |

| Unknown | 1 (1%) | |

| Lymph Node (pN) status | Positive | 21 (30%) |

| Negative | 49 (70%) |

The status of high-risk HPVs, EBV, and MMTV and their association with clinicopathological characteristics

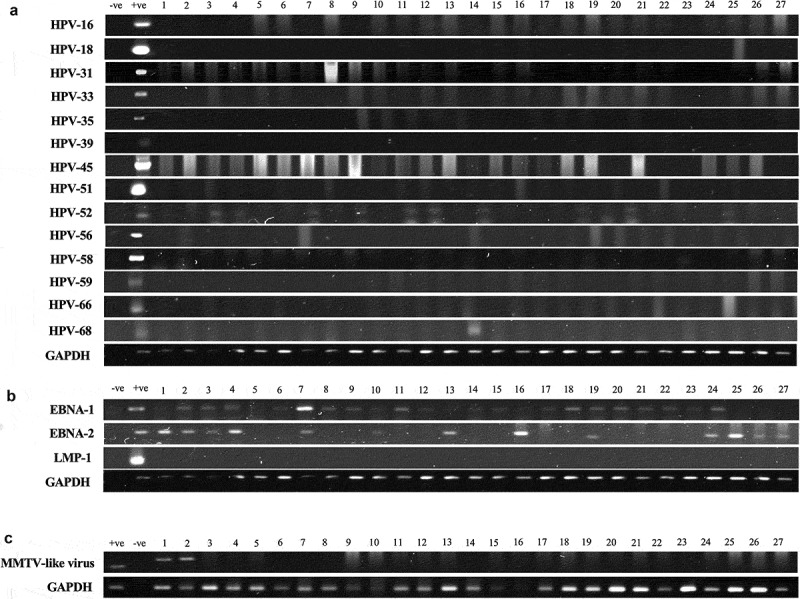

After closer examination of the 72 samples used for PCR assessment of high-risk HPVs, EBV, and MMTV-like viruses (Figure 1), we found that two samples were not TNBC but malignant phyllodes tumor and fibrocystic disease of the breast. These samples along with 14 normal/benign breast tissue samples were compared with the TNBC samples.

Figure 1.

(a–c). Representative PCR reactions for (a) high-risk HPV-subtypes, (b) EBV (EBNA1, EBNA2 and LMP1) and (c) MMTV-like virus in 27 different samples of TNBC. GAPDH was used as an internal control. GAPDH was run common for both HPV and EBV. Respective positive (+ve) and negative (-ve) controls were used as described in the materials and methods section; L- GeneRuler 100 bp DNA Ladder (ThermoFisher Scientific, USA).

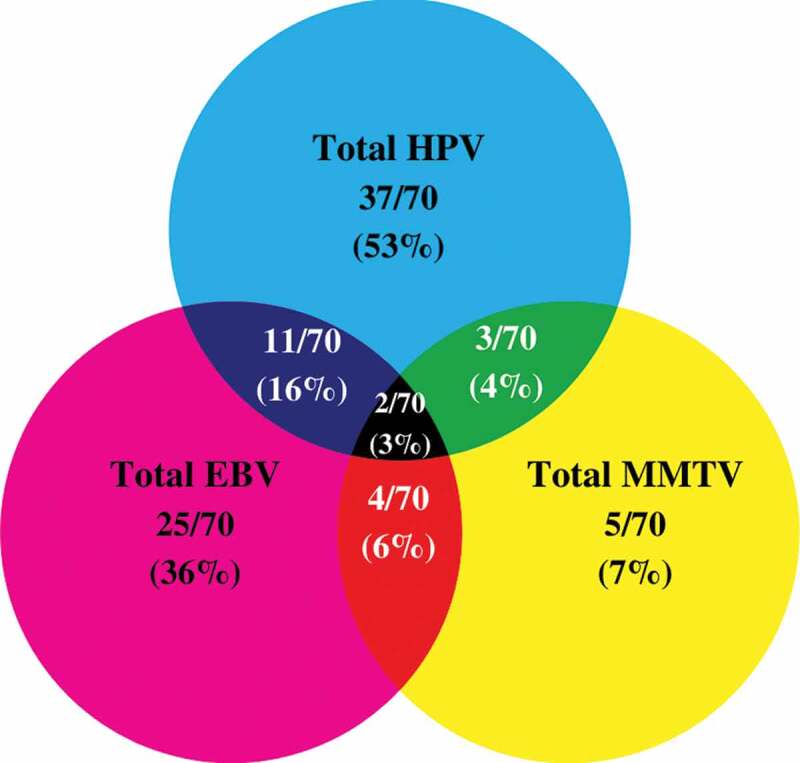

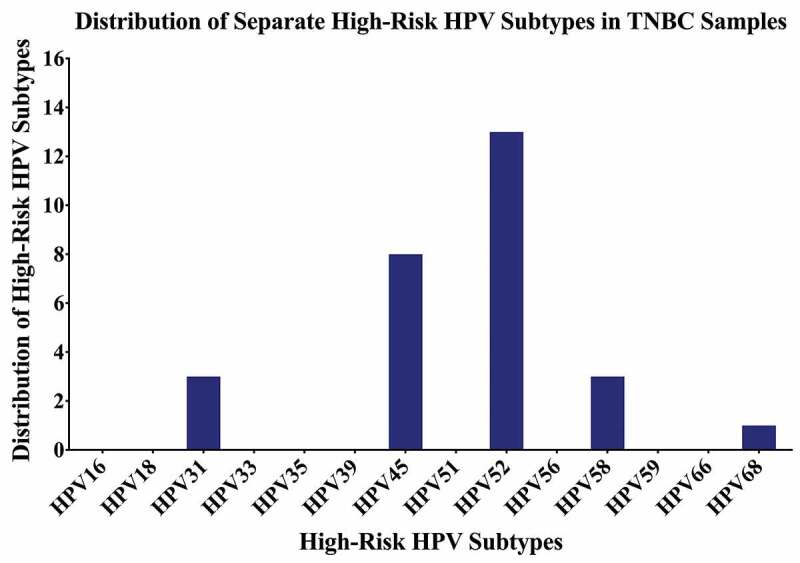

Thirty-seven of the remaining 70 TNBC samples in our cohort are positive for high-risk HPVs (52.8%) (Figure 2 and Table 2); the most commonly present high-risk HPVs are HPV52 (18%) followed by HPV45 (11%), HPV31, and HPV58 (4%, each) and HPV68 (1%) (Figure 3). Notably, HPV types 16, 18, 33, 39, 51, 56, 59, and 66 were not detected in our cohort (Figure 3). Furthermore, our data revealed that while only 27/70 (39%) of the cases are positive for only one HPV subtype, 10/70 (14%) cases are positive for two HPV subtypes.

Figure 2.

Venn Diagram depicting single and multiple infections with HPV, EBV, and/or MMTV-like virus in Croatian triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) samples (n = 70).

Table 2.

Presence of single infection with HPV, EBV, or MMTV-like virus in 70 samples of TNBC

| Single infection | ||

|---|---|---|

| HPV+ | EBV+ | MMTV-like virus+ |

| 53% | 36% | 7% |

Figure 3.

Distribution of each high-risk HPV subtype in Croatian triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) samples. PCR analysis included 70 TNBC samples revealing that the most frequent HPV subtypes are HPV52, HPV45, HPV31, HPV58, and HPV68.

On the other hand, our data revealed that 25/70 of the samples are positive for EBV (36%) (Figure 2 and Table 2); of these 25 cases, EBNA1, EBNA2, and LMP1 of EBV are individually present in 55/70 (78%), 31/70 (44%) and 0/70 (0%) of the TNBC cases, respectively. Additionally, normal/non TNBC samples exhibited positivity for high-risk HPVs (6/16, 37.5%), the most frequent HPV subtypes present in normal/non TNBC samples include HPV52 (6/16, 37.5%) and HPV58 (1/16, 6.3%) (one case co-expressed HPV52 and HPV58); no significant difference was observed in HPV-positivity between normal/non-TNBC and TNBC samples (p = .4). In addition, PCR analysis showed that EBV (EBNA1, EBNA2 and LMP1) was absent in all normal/non TNBC samples (0/16, 0%). However, it is important to highlight a significant difference in EBV-positivity between normal/non-TNBC and TNBC samples (p = .01). More significantly, our data revealed the co-presence of high-risk HPVs and EBV in 16% (11/70) of TNBC cases (Figure 2); however, we did not find any significant correlation between EBV and various HPV types. Moreover, co-presence of high-risk HPVs and EBV was not detected in normal/non-TNBC samples (0/16, 0%); there was no significant difference between normal/non-TNBC and TNBC samples (p = .2).

In parallel, we found 5/70 (7%) of the TNBC cases to be positive for MMTV-like virus (Figure 2 and Table 2) with no presence in normal/non-TNBC samples (0/16, 0%) (p = .6). In addition, 3/70 (4%) and 4/70 (6%) showed co-presence of HPV and MMTV-like virus as well as EBV and MMTV-like virus, respectively. Only two TNBC cases (3%) co-expressed all three oncoviruses (Figure 2). On the other hand, while, we did not find the co-presence of HPV and MMTV-like virus (0/16, 0%), EBV and MMTV-like virus (0/16, 0%) and HPV, EBV and MMTV-like virus (0/16, 0%) in normal/non TNBC samples, there was no significance between normal/non-TNBC and TNBC samples (p = .9, each, respectively).

However, we did not find significant associations between the clinicopathological parameters (tumor grade, tumor stage, and lymph node involvement) and the presence/co-presence of high-risk HPVs, EBV, and MMTV-like virus.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study on the presence/co-presence of high-risk HPVs, EBV, and MMTV-like virus in TNBC from Croatia. Our study revealed that 53% of the samples are positive for these oncoviruses. Numerous studies have reported the presence of high-risk HPVs in human breast cancer patients, including TNBC worldwide, with prevalence ranging from 4% to 86% (Table 3a).22,55–59

Table 3.

(a) Prevalence of HPV in TNBC patients in different populations. (b) Prevalence of EBV in TNBC patients in different populations

| Country | Year | HPV (%) | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (a) | ||||

| Qatar | 2020 | 3/10 (30%) | 36 | |

| Morocco | 2018 | 4/9 (44%) | 70 | |

| Spain | 2017 | 11/24 (9%) | 63 | |

| India | 2017 | 37/67 (55%) | 69 | |

| Australia | 2015 | 1/2 (50%) | 68 | |

| Spain | 2015 | 0/16 (0%) | 120 | |

| Venezuela | 2015 | 2/2 (100%) | 59 | |

| Algeria | 2014 | 5/25 (20%) | 95 | |

| Italy | 2014 | 6/40 (15%) | 67 | |

| (b) | ||||

| Qatar | 2020 | 4/10 (40%) | 36 | |

| France | 2015 | 8/38 (21%) | 94 | |

| Algeria | 2014 | 6/25 (24%) | 95 | |

Our data are similar to studies performed in a large cohort (>1000 samples) of cervical cancer patients from Croatia; the studies have reported HPV prevalence ranging from 43% to 64%.60–62 Moreover, a study by Sabo et al. demonstrated that 31.5% of the samples had only a single HPV infection while the prevalence of multiple HPV infections was 10%;60 this is in line with our data that revealed 38% of the cases were positive for only one HPV subtype and 16% of the cases positive for two HPV subtypes. Similar to our data, HPV prevalence in breast cancer in Spanish women was 52%,63 while in Italian women, the prevalence was 25%.64 On the other hand, in the UK, HPV prevalence of 42% was reported in breast cancer;65 in Germany, HPV prevalence in breast cancer was 86%.66 On the other hand, in the Italian TNBC cases, HPVs were detected in 15% of the samples,67 while only 9% of the TNBC cases in Spain were positive for HPVs.63 This discrepancy can be attributed to the smaller cohort in the Italian and Spanish studies. Concordant with our data, studies from Australia, India, and Morocco reported HPVs prevalence of 50%,68 55%,69 and 44%70 in TNBC samples, respectively. Nevertheless, our recent study in Qatar found HPV positivity in 30% of TNBC cases.36

Indeed, one of the key findings in our study is the predominance of HPV genotypes 52 and 45 followed by 31, 58, and 68 in TNBC samples from Croatian women. It is important to emphasize that HPV types 16 and 18 are the most frequently expressed genotypes in cancers worldwide;57,58,71,72 in Croatia as well, the most prevalent subtype in cervical cancer was HPV16 (44%), followed by HPV18 (39%), HPV51 (18%), HPV31 (11%), HPV33 (8%), and HPV45 (3%).73 Another study in cervical cancer by Sabol et al., found HPV16 as the most prevalent type (61%), followed by HPV18 (10%), HPV31 (4%), HPV33 (4%), HPV35 (2%), HPV45 (6%), HPV52 (3%) and HPV58 (2%).60 However, in our study, we did not detect HPV types 16 and 18 in our cohort from Croatia. A study in China also failed to detect HPV16 and 18 in breast cancer samples.74 However, in breast cancer samples from Australia, HPV18 was detected as the most prevalent subtype in breast cancer specimens.68 This variation in HPV prevalence and genotype distribution can be attributed to geographical location, sample size, type of cancer, and methodological differences.58,75 Interestingly, HPV52 phylogenetically resembles HPV31 (HPV16 species)76 and is the most common HPV-type detected in our samples. Likewise, HPV58 is phylogenetically close to HPV33 (HPV16 species)76 and was the third most common subtype detected in our cohort. On the other hand, HPV45 (HPV18 species)76 was the second most common HPV subtype detected in samples of Croatian women. Due to their comparative high prevalence, HPVs 52, 45 and 58 need special consideration regarding the eventual cross-protection by HPV-vaccines as proven for HPV31, 33 and 45.77 On the other hand, and based on the fact that E6/E7 oncoproteins of high-risk HPVs can convert noninvasive and non-metastatic breast cancer cells into invasive and metastatic ones,78 we believe that more studies with a larger number of samples is necessary to determine the association between the presence of HPVs and tumor phenotype.

Likewise, in human breast cancer, the presence of EBV is detected in 30–50% of breast cancer cases, including TNBC worldwide (Table 3b).79–83 Our study indicated the individual presence of EBNA1, EBNA2, and LMP1 of EBV in 55/70 (78%), 31/70 (44%) and 0/70 (0%) of the TNBC cases, respectively. A probable explanation for the discrepant expression of the EBV variants can be that EBV infects rare tumor cells after neoplastic transformation has occurred. In addition, when latent state infection switches to lytic state infection, EBV-infected cells may be negative for EBERs. Previously, discrepancies in EBV variants were reported in breast cancer samples84–89 and can be explained by the diverse roles of EBNA and LMP genes. During latent phases of EBV, there is different expression of the genes. While, during latency 0, no EBNA protein is expressed, during latency I and II, only EBNA1 is expressed. However, during latency III, all six EBNAs are expressed.90,91 Furthermore, the absence of LMP1 and the co-presence of both EBNA1 and EBNA2 in our cohort can be explained by the fact that in EBV-infected cells, in the latent phase, EBNA and LMP1 are expressed in a cancer-specific manner.92 While, in Burkitt lymphomas, EBNA and EBERs (controlled pattern of viral gene expression: latency 1) is expressed, in Hodgkin lymphomas, diffused large B cell lymphomas and EBV-positive gastric and nasopharyngeal carcinomas, all 10 EBV latent gene products (uncontrolled pattern of viral gene expression: latency II and III) are expressed.92 Regardless of the latency pattern, virtually all EBV-associated malignancies express EBNA and EBERs.92 Moreover, since PCR is a sensitive technique, the absence of LMP1 in all samples in our opinion is the result of the discrepant expression of EBV gene products in our cohort and not due to lytic state infection.

A previous IHC study reported EBV prevalence of 43% in all breast cancer cases, of which 49% were triple-negative.93 Quantitative PCR analysis showed EBV positivity in 32.5% of breast cancer cases in French women; however, EBV-positive cases were more prevalent in TNBC (21%).94 Additionally, an Algerian study reported EBV presence in 24% of the examined TNBC cases,95 while in Qatar, EBV prevalence was detected in 40% of TNBC samples.36 On the other hand, in Eritrea, PCR analysis revealed EBV in 28% of breast cancer cases.96 We herein report that EBV is present in approximately 36% of TNBC cases in Croatian women. Therefore, our data indicate that the prevalence of EBV in TNBC tissues in Croatia is similar to the incidence present worldwide, including in the European region.

On the other hand, although, MMTV-like virus gene was detected in human breast cancer in varying proportions worldwide, ranging from 0% to 74% of cases41 (Table 4), studies analyzing the role of MMTV-like virus gene in TNBC samples are rare.

Table 4.

Prevalence of MMTV-like virus in breast cancer in different populations

| Country | Year | MMTV-like virus (%) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| China | 2021 | 21/119 (18%) | 97 |

| Brazil | 2020 | 41/217 (19%) (Tissue samples) 17/32 (53%) (Blood samples) |

98 |

| Morocco | 2014 | 24/42 (57%) | 99 |

| United Kingdom | 2012 | 39/50 (78%) | 79 |

| Tunisia | 2008 | 17/122 (14%) | 100 |

| China | 2006 | 22/131 (17%) | 101 |

| Tunisia | 2004 | 28/38 (74%) | 102 |

| Australia | 2003 | 19/45 (42%) | 103 |

| Vietnam | 2003 | 1/120 (1%) | 103 |

| Argentina | 2002 | 23/74 (31%) | 104 |

| USA | 2000 | 27/73 (31%) | 105 |

| Italy | 1999 | 26/69 (38%) | 106 |

| USA | 1995 | 121/314 (39%) (660-bp) 60/151 (40%) (250-bp) |

107 |

In the present study, we found that the MMTV-like virus gene is present in only 7% of TNBC samples from the Croatian cohort, similar to findings from a Brazilian TNBC cohort (4%).98 Moreover, MMTV-like virus was detected in 19%, 17%, and 14% of breast cancer samples in Brazilian,98 Chinese,101 and Tunisian100 populations. Another study by Liu et al.108 isolated a complete provirus from human breast cancer samples, while a study by Lawson et al.45 detected MMTV-like antigens and sequences in benign lesions that developed to breast cancer in women during later years. MMTV-like virus gene was detected in 38% of human breast cancers but not in normal breast tissues.109 A similar prevalence rate was reported by Ford et al. in breast cancer samples from Australia and Vietnam.103 Etkind et al. performed PCR analysis using stringent hybridization techniques and detected MMTV-like virus gene in 37% of the human breast tumors.105 However, other studies detected a higher presence of MMTV-like virus in breast cancer. In Morocco, the MMTV-like virus gene was detected in 57% of all breast cancer subtypes with no specific association with hormonal status.99 Another investigation from Egypt by Loutfy et al.110 detected a higher prevalence rate of MMTV-like virus in both sporadic and germline breast cancer cases. In sporadic breast cancer, MMTV-like virus was present in 76% of the cases, while, 70% of hereditary breast cancer samples were positive for this oncovirus.110 However, a study in China found contrasting prevalence of MMTV-like virus in breast cancer samples from Northern and Southern China; while MMTV-like virus was present in 23% of the North Chinese women with breast cancer, in South Chinese women MMTV-like virus was prevalent in only 6% of the cases.97 Furthermore, the study demonstrated the discrepant MMTV-like virus prevalence to be dependent on the worldwide distribution of M. domesticus, M. musculus and M. Castaneus mice; thus indicating the presence of house mice as a vital underlying environmental factor elucidating the geographical variation in the prevalence of human breast cancer.97 On the contrary, studies failed to detect MMTV-like sequences in tumor tissue samples.111,112 These discrepancies can be attributed to technical, methodological, or epidemiological variations among studies.41

Intriguingly, based on previous works, including ours, high-risk HPVs and EBV co-presence can play an essential role in the onset and progression of different cancers, including oral, colorectal, cervical, and breast.22,42–44,113,114 In concordance, in our present investigation, we report that 16% of TNBC cases from Croatian women are co-infected with both HPVs and EBV; the presence of HPVs and EBV has been considered as a risk factor for TNBC.115 Moreover, in this study, we found that the co-presence of the three oncoviruses (HPV, EBV, and MMT-like virus) in only 3% of our TNBC cohort. However, similar to other studies, in this study, we did not find any association between the presence/co-presence of HPVs, EBV, and MMTV-like virus and clinicopathological characteristics.94,116 However, de Sousa Pereira et al. found a correlation between MMTV-like virus and clinicopathological features in Luminal B and HER2-positive samples,98 thus indicating that MMTV-like presence may display subtype-specific effects in breast cancer. Thus, further studies are needed to evaluate the role of the MMTV-like virus in a larger breast cancer cohort.

In our previous studies, we have demonstrated that oncoproteins of HPVs (E5 and E6/E7) and EBV (LMP1 and/or EBNA1) can interact and cooperate in the initiation and/or progression of human oral and breast carcinomas via the EMT event;17 thus indicating a similar mechanism in the pathogenesis of human breast malignancy. Moreover, several studies have pointed out the plausible role of MMTV-like virus in the onset and progression of breast cancer by stimulating IFN signaling and APOBEC-mediated mutagenesis in breast cancer, thus, allowing genomic instability and tumor development.117–119 Based on the role of HPVs, EBV, and MMTV-like virus in the pathogenesis of breast cancer, we suggest that oncoproteins of HPVs can interact with those of EBV (LMP1 and/or EBNA1) as well as MMTV-like virus resulting in the onset and progression of different types of cancers including breast.25,44,51

The current study has several limitations. Firstly, we lacked an appropriate control group for the study (e.g., reduction mammoplasty samples); however, using the same methodology, we recently reported the prevalence of high-risk HPVs and EBV in breast cancer samples from Lebanon.49 Secondly, since we did not have complete access to TNBC tissue samples, we could apply only one method (PCR-based) for HPV, EBV, and MMTV-like virus assessment. Of note, our previous studies exploring HPV and EBV in different types of cancers using PCR and IHC yielded comparable results.36,43,44,49,51

Conclusions

Although the sample size used in the current study is relatively small, it indicates the presence/co-presence of the three oncoviruses in very few cases without any correlation with the studied clinicopathological parameters. Thus, we believe that future investigations with a larger cohort from different geographic locations are needed to confirm the co-presence of these oncoviruses in breast cancer to elucidate the exact role of their cooperation in breast carcinogenesis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Mrs. A. Kassab for her critical reading of the manuscript.

Funding Statement

The current study was supported by the grants from Qatar University: QUCP-CMED-2019-1 and QUCG-CMED-20/21-2.

Supplemental data

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed on the publisher’s website at https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2021.1975452.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- 1.Ferlay J, Colombet M, Soerjomataram I, Mathers C, Parkin DM, Piñeros M, Znaor A, Bray F.. Estimating the global cancer incidence and mortality in 2018: GLOBOCAN sources and methods. Int J Cancer. 2019;144(8):1941–53. doi: 10.1002/ijc.31937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Perou CM, Sørlie T, Eisen MB, van de Rijn M, Jeffrey SS, Rees CA, Pollack JR, Ross DT, Johnsen H, Akslen LA, et al. Molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature. 2000;406(6797):747–52. doi: 10.1038/35021093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sorlie T, Tibshirani R, Parker J, Hastie T, Marron JS, Nobel A, Deng S, Johnsen H, Pesich R, Geisler S, et al. Repeated observation of breast tumor subtypes in independent gene expression data sets. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(14):8418–23. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0932692100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Foulkes WD, Smith IE, Reis-Filho JS.. Triple-negative breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(20):1938–48. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1001389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Slamon DJ, Clark GM, Wong SG, Levin WJ, Ullrich A, McGuire WL. Human breast cancer: correlation of relapse and survival with amplification of the HER-2/neu oncogene. Science. 1987;235(4785):177–82. doi: 10.1126/science.3798106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Putti TC, El-Rehim DM, Rakha EA, Paish CE, Lee AH, Pinder SE, Ellis IO. Estrogen receptor-negative breast carcinomas: a review of morphology and immunophenotypical analysis. Mod Pathol. 2005;18(1):26–35. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Irvin WJ Jr., Carey LA. What is triple-negative breast cancer? Eur J Cancer. 2008;44(18):2799–805. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.09.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stockmans G, Deraedt K, Wildiers H, Moerman P, Paridaens R. Triple-negative breast cancer. Curr Opin Oncol. 2008;20(6):614–20. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0b013e328312efba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Venuti A, Badaracco G, Rizzo C, Mafera B, Rahimi S, Vigili M. Presence of HPV in head and neck tumours: high prevalence in tonsillar localization. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2004;23:561–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ragin CC, Taioli E. Survival of squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck in relation to human papillomavirus infection: review and meta-analysis. Int J Cancer. 2007;121(8):1813–20. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shi Y, Peng SL, Yang LF, Chen X, Tao YG, Cao Y. Co-infection of Epstein-Barr virus and human papillomavirus in human tumorigenesis. Chin J Cancer. 2016;35(1):16. doi: 10.1186/s40880-016-0079-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deligdisch L, Marin T, Lee AT, Etkind P, Holland JF, Melana S, Pogo BGT, Deligdisch L, Marin T, Lee AT, et al. Human mammary tumor virus (HMTV) in endometrial carcinoma. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2013;23(8):1423–28. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0b013e3182980fc5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johal H, Faedo M, Faltas J, Lau A, Mousina R, Cozzi P, deFazio A, Rawlinson WD. DNA of mouse mammary tumor virus-like virus is present in human tumors influenced by hormones. J Med Virol. 2010;82(6):1044–50. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tulay P, Serakinci N. The route to HPV-associated neoplastic transformation: a review of the literature. Crit Rev Eukaryot Gene Expr. 2016;26(1):27–39. doi: 10.1615/CritRevEukaryotGeneExpr.v26.i1.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ferreira AR, Ramalho AC, Marques M, Ribeiro D. The interplay between antiviral signalling and carcinogenesis in human papillomavirus infections. Cancers (Basel). 2020;12(3):646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moody CA, Laimins LA. Human papillomavirus oncoproteins: pathways to transformation. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10(8):550–60. doi: 10.1038/nrc2886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Al Moustafa AE. E5 and E6/E7 of high-risk HPVs cooperate to enhance cancer progression through EMT initiation. Cell Adh Migr. 2015;9(5):392–93. doi: 10.1080/19336918.2015.1042197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen X, Bode AM, Dong Z, Cao Y. The epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) is regulated by oncoviruses in cancer. Faseb J. 2016;30(9):3001–10. doi: 10.1096/fj.201600388R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Al-Thawadi H, Gupta I, Jabeen A, Skenderi F, Aboulkassim T, Yasmeen A, Malki MI, Batist G, Vranic S, Al Moustafa A-E, et al. Co-presence of human papillomaviruses and Epstein–Barr virus is linked with advanced tumor stage: a tissue microarray study in head and neck cancer patients. Cancer Cell Int. 2020;20(1):361. doi: 10.1186/s12935-020-01348-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schiffman M, Castle PE, Jeronimo J, Rodriguez AC, Wacholder S. Human papillomavirus and cervical cancer. Lancet. 2007;370(9590):890–907. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61416-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li N, Yang L, Zhang Y, Zhao P, Zheng T, Dai M. Human papillomavirus infection and bladder cancer risk: a meta-analysis. J Infect Dis. 2011;204(2):217–23. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Akil N, Yasmeen A, Kassab A, Ghabreau L, Darnel AD, Al Moustafa A-E. High-risk human papillomavirus infections in breast cancer in Syrian women and their association with Id-1 expression: a tissue microarray study. Br J Cancer. 2008;99(3):404–07. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bedri S, Sultan AA, Alkhalaf M, Al Moustafa A-E, Vranic S. Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) status in colorectal cancer: a mini review. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2019;15(3):603–10. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2018.1543525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Young LS, Arrand JR, Murray PG. EBV gene expression and regulation. In: Arvin AC-FG, Mocarski E, et al., editors. Human herpesviruses: biology, therapy, and immunoprophylaxis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cyprian FS, Al-Farsi HF, Vranic S, Akhtar S, Al Moustafa AE. Epstein-Barr virus and human papillomaviruses interactions and their roles in the initiation of epithelial-mesenchymal transition and cancer progression. Front Oncol. 2018;8:111. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2018.00111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shimakage M, Horii K, Tempaku A, Kakudo K, Shirasaka T, Sasagawa T. Association of Epstein-Barr virus with oral cancers. Hum Pathol. 2002;33(6):608–14. doi: 10.1053/hupa.2002.129786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Boudreault S, Armero VES, Scott MS, Perreault J-P, Bisaillon M. The Epstein-Barr virus EBNA1 protein modulates the alternative splicing of cellular genes. Virol J. 2019;16(1):29. doi: 10.1186/s12985-019-1137-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bittner JJ. Some possible effects of nursing on the mammary gland tumor incidence in mice. Science. 1936;84(2172):162. doi: 10.1126/science.84.2172.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mason A. Is there a breast cancer virus? Ochsner J. 2000;2:36–39. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lawson JS, Günzburg WH, Whitaker NJ. Viruses and human breast cancer. Future Microbiol. 2006;1(1):33–51. doi: 10.2217/17460913.1.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nartey T, Moran H, Marin T, Arcaro KF, Anderton DL, Etkind P, Holland JF, Melana SM, Pogo BGT. Human mammary tumor virus (HMTV) sequences in human milk. Infect Agent Cancer. 2014;9(1):20. doi: 10.1186/1750-9378-9-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mazzanti CM, Lessi F, Armogida I, Zavaglia K, Franceschi S, Al Hamad M, Roncella M, Ghilli M, Boldrini A, Aretini P, et al. Human saliva as route of inter-human infection for mouse mammary tumor virus. Oncotarget. 2015;6(21):18355–63. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.4567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lushnikova AA, Kriukova IN, Malivanova TF, Makhov PB, Polevaia EB. Correlation between expression of antigen immunologically related to gp52 MMTV and transcription of homologous ENV MMTV DNA sequences in peripheral blood lymphocytes from breast cancer patients. Mol Gen Mikrobiol Virusol. 1998:33–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dudley JP, Golovkina TV, Ross SR. Lessons learned from mouse mammary tumor virus in animal models. ILAR J. 2016;57(1):12–23. doi: 10.1093/ilar/ilv044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Al Moustafa A-E, Al-Awadhi R, Missaoui N, Adam I, Durusoy R, Ghabreau L, Akil N, Ahmed HG, Yasmeen A, Alsbeih G, et al. Human papillomaviruses-related cancers. Presence and prevention strategies in the Middle east and north African regions. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2014;10(7):1812–21. doi: 10.4161/hv.28742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gupta I, Jabeen A, Al-Sarraf R, Farghaly H, Vranic S, Sultan AA, Al Moustafa A-E, Al-Thawadi H. The co-presence of high-risk human papillomaviruses and Epstein-Barr virus is linked with tumor grade and stage in Qatari women with breast cancer. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2021;17(4):982–89. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2020.1802977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Al Hamad M, Matalka I, Al Zoubi MS, Armogida I, Khasawneh R, Al-Husaini M, et al. Human mammary tumor virus, human papilloma virus, and Epstein-Barr virus infection are associated with sporadic breast cancer metastasis. Breast Cancer: Basic Clin Res. 2020;14:1178223420976388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lawson JS, Heng B. Viruses and breast cancer. Cancers. 2010;2(2):752–72. doi: 10.3390/cancers2020752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.De Cremoux P, Thioux M, Lebigot I, Sigal-Zafrani B, Salmon R, Sastre-Garau X. No evidence of human papillomavirus DNA sequences in invasive breast carcinoma. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008;109(1):55–58. doi: 10.1007/s10549-007-9626-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Herrmann K, Niedobitek G. Lack of evidence for an association of Epstein–Barr virus infection with breast carcinoma. Breast Cancer Res. 2002;5(1):R13. doi: 10.1186/bcr561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Amarante MK, de Sousa Pereira N, Vitiello GAF, Watanabe MAE. Involvement of a mouse mammary tumor virus (MMTV) homologue in human breast cancer: evidence for, against and possible causes of controversies. Microb Pathog. 2019;130:283–94. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2019.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Al Moustafa A-E, Al-Antary N, Aboulkassim T, Akil N, Batist G, Yasmeen A. Co-prevalence of Epstein-Barr virus and high-risk human papillomaviruses in Syrian women with breast cancer. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2016;12:1936–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Al-Thawadi H, Ghabreau L, Aboulkassim T, Yasmeen A, Vranic S, Batist G, Al Moustafa A-E. Co-incidence of Epstein–Barr virus and high-risk human papillomaviruses in cervical cancer of Syrian women. Front Oncol. 2018;8:250. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2018.00250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Malki MI, Gupta I, Fernandes Q, Aboulkassim T, Yasmeen A, Vranic S, Al Moustafa A-E, Al-Thawadi HA. Co-presence of Epstein–Barr virus and high-risk human papillomaviruses in Syrian colorectal cancer samples. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2020;16(10):2403–07. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2020.1726680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lawson JS, Glenn WK. Evidence for a causal role by mouse mammary tumour-like virus in human breast cancer. NPJ Breast Cancer. 2019;5(1):40. doi: 10.1038/s41523-019-0136-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Allison KH, Hammond MEH, Dowsett M, McKernin SE, Carey LA, Fitzgibbons PL, Hayes DF, Lakhani SR, Chavez-MacGregor M, Perlmutter J, et al. Estrogen and progesterone receptor testing in breast cancer: ASCO/CAP guideline update. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(12):1346–66. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.02309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wolff AC, Hammond MEH, Allison KH, Harvey BE, Mangu PB, Bartlett JMS, Bilous M, Ellis IO, Fitzgibbons P, Hanna W, et al. Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 testing in breast cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology/College of American Pathologists clinical practice guideline focused update. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2018;142(11):1364–82. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2018-0902-SA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Elston CW, Ellis IO. Pathological prognostic factors in breast cancer. I. The value of histological grade in breast cancer: experience from a large study with long-term follow-up. Histopathology. 1991;19(5):403–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.1991.tb00229.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nagi K, Gupta I, Jurdi N, Jabeen A, Yasmeen A, Batist G, Vranic S, Al-Moustafa A-E. High-risk human papillomaviruses and Epstein–Barr virus in breast cancer in Lebanese women and their association with tumor grade: a molecular and tissue microarray study. Cancer Cell Int. 2021;21(1):308. doi: 10.1186/s12935-021-02009-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gupta I, Nasrallah GK, Sharma A, Jabeen A, Smatti MK, Al-Thawadi HA, Sultan AA, Alkhalaf M, Vranic S, Moustafa AEA, et al. Co-prevalence of human Papillomaviruses (HPV) and Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) in healthy blood donors from diverse nationalities in Qatar. Cancer Cell Int. 2020;20(1):107. doi: 10.1186/s12935-020-01190-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gupta I, Al Farsi H, Jabeen A, Skenderi F, Al-Thawadi H, AlAhmad YM, Abdelhafez I, Al Moustafa A-E, Vranic S. High-risk human papillomaviruses and Epstein–Barr virus in colorectal cancer and their association with clinicopathological status. Pathogens. 2020;9(6):452. doi: 10.3390/pathogens9060452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Xiao C-Y, Fu -B-B, Li Z-Y, Mushtaq G, Kamal MA, Li J-H, Tang G-C, Xiao -S-S. Observations on the expression of human papillomavirus major capsid protein in HeLa cells. Cancer Cell Int. 2015;15(1):53. doi: 10.1186/s12935-015-0206-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Al Moustafa A-E, Foulkes WD, Benlimame N, Wong A, Yen L, Bergeron J, Batist G, Alpert L, Alaoui-Jamali MA. E6/E7 proteins of HPV type 16 and ErbB-2 cooperate to induce neoplastic transformation of primary normal oral epithelial cells. Oncogene. 2004;23(2):350–58. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.May FE, Westley BR. Characterization of sequences related to the mouse mammary tumor virus that are specific to MCF-7 breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 1989;49:3879–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Heng B, Glenn WK, Ye Y, Tran B, Delprado W, Lutze-Mann L, Whitaker NJ, Lawson JS. Human papilloma virus is associated with breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 2009;101(8):1345–50. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Khodabandehlou N, Mostafaei S, Etemadi A, Ghasemi A, Payandeh M, Hadifar S, Norooznezhad AH, Kazemnejad A, Moghoofei M. Human papilloma virus and breast cancer: the role of inflammation and viral expressed proteins. BMC Cancer. 2019;19(1):61. doi: 10.1186/s12885-019-5286-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Herrera-Goepfert R, Vela-Chávez T, Carrillo-García A, Lizano-Soberón M, Amador-Molina A, Oñate-Ocaña LF, Hallmann RSR. High-risk human papillomavirus (HPV) DNA sequences in metaplastic breast carcinomas of Mexican women. BMC Cancer. 2013;13(1):445. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-13-445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Khan NA, Castillo A, Koriyama C, Kijima Y, Umekita Y, Ohi Y, Higashi M, Sagara Y, Yoshinaka H, Tsuji T, et al. Human papillomavirus detected in female breast carcinomas in Japan. Br J Cancer. 2008;99(3):408–14. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fernandes A, Bianchi G, Feltri AP, Pérez M, Correnti M. Presence of human papillomavirus in breast cancer and its association with prognostic factors. Ecancermedicalscience. 2015;9:548. doi: 10.3332/ecancer.2015.548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sabol I, Milutin Gašperov N, Matovina M, Božinović K, Grubišić G, Fistonić I, Belci D, Alemany L, Džebro S, Dominis M, et al. Cervical HPV type-specific pre-vaccination prevalence and age distribution in Croatia. PLOS ONE. 2017;12(7):e0180480. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0180480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Grce M, Husnjak K, Magdić L, Ilijas M, Zlacki M, Lepusić D, Lukač J, Hodek B, Grizelj V, Kurjak A, et al. Detection and typing of human papillomaviruses by polymerase chain reaction in cervical scrapes of Croatian women with abnormal cytology. Eur J Epidemiol. 1997;13(6):645–51. doi: 10.1023/A:1007323405069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Grce M, Husnjak K, Bozikov J, Magdić L, Zlacki M, Lukac J, et al. Evaluation of genital human papillomavirus infections by polymerase chain reaction among Croatian women. Anticancer Res. 2001;21:579–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Delgado-García S, Martínez-Escoriza J-C, Alba A, Martín-Bayón T-A, Ballester-Galiana H, Peiró G, Caballero P, Ponce-Lorenzo J. Presence of human papillomavirus DNA in breast cancer: a Spanish case-control study. BMC Cancer. 2017;17(1):320. doi: 10.1186/s12885-017-3308-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Frega A, Lorenzon L, Bononi M, De Cesare A, Ciardi A, Lombardi D, et al. Evaluation of E6 and E7 mRNA expression in HPV DNA positive breast cancer. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2012;33:164–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Salman NA, Davies G, Majidy F, Shakir F, Akinrinade H, Perumal D, Ashrafi GH. Association of high risk human papillomavirus and breast cancer: a UK based study. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):43591. doi: 10.1038/srep43591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.de Villiers E-M, Sandstrom RE, zur Hausen H, Buck CE. Presence of papillomavirus sequences in condylomatous lesions of the mamillae and in invasive carcinoma of the breast. Breast Cancer Res. 2004;7(1):R1–R11. doi: 10.1186/bcr940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Piana AF, Sotgiu G, Muroni MR, Cossu-Rocca P, Castiglia P, De Miglio MR. HPV infection and triple-negative breast cancers: an Italian case-control study. Virol J. 2014;11(1):190. doi: 10.1186/s12985-014-0190-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lawson JS, Glenn WK, Salyakina D, Delprado W, Clay R, Antonsson A, Heng B, Miyauchi S, Tran DD, Ngan CC, et al. Human papilloma viruses and breast cancer. Front Oncol. 2015;5:277. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2015.00277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Islam S, Dasgupta H, Roychowdhury A, Bhattacharya R, Mukherjee N, Roy A, Mandal GK, Alam N, Biswas J, Mandal S, et al. Study of association and molecular analysis of human papillomavirus in breast cancer of Indian patients: clinical and prognostic implication. PLOS ONE. 2017;12(2):e0172760. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0172760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Habyarimana T, Attaleb M, Mazarati JB, Bakri Y, El Mzibri M. Detection of human papillomavirus DNA in tumors from Rwandese breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer. 2018;25(2):127–33. doi: 10.1007/s12282-018-0831-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Pajtler M, Audy-Jurković S, Kardum-Skelin I, Mahovlić V, Mozetic-Vrdoljak D, Ovanin-Rakić A. Organisation of cervical cytology screening in Croatia: past, present and future. Coll Antropol. 2007;31:47–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kovacevic G, Milosevic V, Knezevic P, Knezevic A, Knezevic I, Radovanov J, Nikolic N, Patic A, Petrovic V, Hrnjakovic Cvjetkovic I, et al. Prevalence of oncogenic Human papillomavirus and genetic diversity in the L1 gene of HPV16 HPV 18 HPV31 and HPV33 found in women from Vojvodina Province Serbia. Biologicals. 2019;58:57–63. doi: 10.1016/j.biologicals.2019.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bruni L, Albero G, Serrano B, Mena M, Gómez D, Muñoz J, et al. ICO/IARC information centre on HPV and cancer (HPV information centre). human papillomavirus and related diseases in Croatia. HPV Information Centre; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Yu Y, Morimoto T, Sasa M, Okazaki K, Harada Y, Fujiwara T, Irie Y, Takahashi E-I, Tanigami A, Izumi K, et al. Human papillomavirus type 33 DNA in breast cancer in Chinese. Breast Cancer. 2000;7(1):33–36. doi: 10.1007/BF02967185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wang T, Chang P, Wang L, Yao Q, Guo W, Chen J, Yan T, Cao C. The role of human papillomavirus infection in breast cancer. Med Oncol. 2012;29(1):48–55. doi: 10.1007/s12032-010-9812-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bernard H-U, Burk RD, Chen Z, Van Doorslaer K, zur Hausen H, de Villiers E-M. Classification of papillomaviruses (PVs) based on 189 PV types and proposal of taxonomic amendments. Virology. 2010;401(1):70–79. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2010.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Harper DM. Currently approved prophylactic HPV vaccines. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2009;8(12):1663–79. doi: 10.1586/erv.09.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Yasmeen A, Bismar TA, Kandouz M, Foulkes WD, Desprez P-Y, Al Moustafa A-E. E6/E7 of HPV type 16 promotes cell invasion and metastasis of human breast cancer cells. Cell Cycle. 2007;6(16):2038–42. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.16.4555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Glenn WK, Heng B, Delprado W, Iacopetta B, Whitaker NJ, Lawson JS, Mahieux R. Epstein-Barr virus, human papillomavirus and mouse mammary tumour virus as multiple viruses in breast cancer. PLoS One. 2012;7(11):e48788. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0048788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Joshi D, Quadri M, Gangane N, Joshi R, Gangane N, Kashanchi F. Association of Epstein Barr virus infection (EBV) with breast cancer in rural Indian women. PLoS One. 2009;4(12):e8180. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lorenzetti MA, De Matteo E, Gass H, Martinez Vazquez P, Lara J, Gonzalez P, Preciado MV, Chabay PA. Characterization of Epstein Barr virus latency pattern in Argentine breast carcinoma. PLoS One. 2010;5(10):e13603. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Fawzy S, Sallam M, Awad NM. Detection of Epstein–Barr virus in breast carcinoma in Egyptian women. Clin Biochem. 2008;41(7–8):486–92. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2007.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Xue SA, Lampert IA, Haldane JS, Bridger JE, Griffin BE. Epstein–Barr virus gene expression in human breast cancer: protagonist or passenger? Br J Cancer. 2003;89(1):113–19. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Zekri ARN, Bahnassy AA, Mohamed WS, El-Kassem FA, El-Khalidi SJ, Hafez MM, Hassan ZK. Epstein-Barr virus and breast cancer: epidemiological and Molecular study on Egyptian and Iraqi women. J Egypt Natl Canc Inst. 2012;24(3):123–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jnci.2012.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Iezzoni JC, Gaffey MJ, Weiss LM. The role of Epstein-Barr virus in lymphoepithelioma-like carcinomas. Am J Clin Pathol. 1995;103(3):308–15. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/103.3.308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Chu J-S, Chen -C-C, Chang K-J. In situ detection of Epstein–Barr virus in breast cancer. Cancer Lett. 1998;124(1):53–57. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3835(97)00449-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Labrecque LG, Barnes DM, Fentiman IS, Griffin BE. Epstein-Barr virus in epithelial cell tumors: a breast cancer study. Cancer Res. 1995;55:39–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Luqmani Y, Shousha S. Presence of Epstein-Barr-virus in breast-carcinoma. Int J Oncol. 1995;6:899–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Bonnet M, Guinebretiere J-M, Kremmer E, Grunewald V, Benhamou E, Contesso G, Joab I. Detection of Epstein-Barr virus in invasive breast cancers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91(16):1376–81. doi: 10.1093/jnci/91.16.1376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ayee R, Ofori MEO, Wright E, Quaye O. Epstein Barr virus associated lymphomas and epithelia cancers in humans. J Cancer. 2020;11(7):1737–50. doi: 10.7150/jca.37282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kieff EDRA. Epstein-Barr virus and its replication. In: Knipe DMHP, editor. Fields Virology. Philadelphia (USA): Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007. p. 2603–54. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Ambinder R, Weiss L. Association of Epstein-Barr virus with Hodgkin’s disease. In: Mauch P, Armitage J, Diehl V, Hoppe R, Weiss L, editors. Hodgkin’s disease. Philadelphia (USA): Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1999. p. 79–98. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Ballard A. Epstein-Barr virus is associated with aggressive subtypes of invasive ductal carcinoma of breast (Her2+/ER- and triple negative) and with nuclear Expression of NF?B p50. Arch Breast Cancer. 2018;5:68–75. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Mazouni C, Fina F, Romain S, Ouafik L, Bonnier P, Martin P-M. Outcome of Epstein-Barr virus-associated primary breast cancer. Mol Clin Oncol. 2015;3(2):295–98. doi: 10.3892/mco.2014.459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Corbex M, Bouzbid S, Traverse-Glehen A, Aouras H, McKay-Chopin S, Carreira C, Lankar A, Tommasino M, Gheit T, et al. Prevalence of papillomaviruses, polyomaviruses, and herpesviruses in triple-negative and inflammatory breast tumors from Algeria compared with other types of breast cancer tumors. PLOS ONE. 2014;9(12):e114559. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0114559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Fessahaye G, Elhassan AM, Elamin EM, Adam AAM, Ghebremedhin A, Ibrahim ME. Association of Epstein - Barr virus and breast cancer in Eritrea. Infect Agent Cancer. 2017;12(1):62. doi: 10.1186/s13027-017-0173-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Wang F-L, Zhang X-L, Yang M, Lin J, Yue Y-F, Li Y-D, Wang X, Shu Q, Jin H-C. Prevalence and characteristics of mouse mammary tumor virus-like virus associated breast cancer in China. Infect Agent Cancer. 2021;16(1):47. doi: 10.1186/s13027-021-00383-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.de Sousa Pereira N, Akelinghton Freire Vitiello G, Karina Banin-Hirata B, Scantamburlo Alves Fernandes G, José Sparça Salles M, Karine Amarante M, Angelica Ehara Watanabe M. Mouse Mammary Tumor Virus (MMTV)-like env sequence in Brazilian breast cancer samples: implications in clinicopathological parameters in molecular subtypes. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(24):9496. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17249496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Slaoui M, El Mzibri M, Razine R, Qmichou Z, Attaleb M, Amrani M. Detection of MMTV-Like sequences in Moroccan breast cancer cases. Infect Agent Cancer. 2014;9(1):37. doi: 10.1186/1750-9378-9-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Hachana M, Trimeche M, Ziadi S, Amara K, Gaddas N, Mokni M, Korbi S. Prevalence and characteristics of the MMTV-like associated breast carcinomas in Tunisia. Cancer Lett. 2008;271(2):222–30. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Luo T, Wu XT, Zhang MM, Qian K. Study of mouse mammary tumor virus-like gene sequences expressing in breast tumors of Chinese women. Sichuan Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban. 2006;37:51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Levine PH, Pogo BGT, Klouj A, Coronel S, Woodson K, Melana SM, Mourali N, Holland JF. Increasing evidence for a human breast carcinoma virus with geographic differences. Cancer. 2004;101(4):721–26. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Ford CE, Tran D, Deng Y, Ta VT, Rawlinson WD, Lawson JS. Mouse mammary tumor virus-like gene sequences in breast tumors of Australian and Vietnamese women. Clin. Cancer Res 2003;9:1118–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Melana SM, Picconi MA, Rossi C, Mural J, Alonio LV, Teyssié A, et al. Detection of murine mammary tumor virus (MMTV) env gene-like sequences in breast cancer from Argentine patients. Medicina (B Aires). 2002;62:323–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Etkind P, Du J, Khan A, Pillitteri J, Wiernik PH. Mouse mammary tumor virus-like ENV gene sequences in human breast tumors and in a lymphoma of a breast cancer patient. Clin. Cancer Res 2000;6:1273–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Pogo BG-T, Melana SM, Holland JF, Mandeli JF, Pilotti S, Casalini P, et al. Sequences homologous to the mouse mammary tumor virus env gene in human breast carcinoma correlate with overexpression of laminin receptor. Clin. Cancer Res 1999;5:2108–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Wang Y, Holland JF, Bleiweiss IJ, Melana S, Liu X, Pelisson I, et al. Detection of mammary tumor virus ENV gene-like sequences in human breast cancer. Cancer Res. 1995;55:5173–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Liu B, Wang Y, Melana SM, Pelisson I, Najfeld V, Holland JF, et al. Identification of a Proviral Structure in Human Breast Cancer. Cancer Res. 2001;61:1754–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Wang Y, Pelisson I, Melana SM, Go V, Holland JF, Pogo BG. MMTV-like env gene sequences in human breast cancer. Arch Virol. 2001;146(1):171–80. doi: 10.1007/s007050170201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Loutfy S, Abdallah Z, Shaalan M, Moneer M, Karam A, Moneer M, Sayed IM, Abd El-Hafeez AA, Ghosh P, Zekri ARN, et al. Prevalence of MMTV-like ENV sequences and its association with BRCA1/2 genes mutations among Egyptian breast cancer patients. Cancer Manag Res. 2021;13:2835–48. doi: 10.2147/CMAR.S294584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Fukuoka H, Moriuchi M, Yano H, Nagayasu T, Moriuchi H. No association of mouse mammary tumor virus-related retrovirus with Japanese cases of breast cancer. J Med Virol. 2008;80(8):1447–51. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Ahangar Oskouee M, Shahmahmoodi S, Jalilvand S, Mahmoodi M, Ziaee AA, Esmaeili HA, Mokhtari-Azad T, Yousefi M, Mollaei-Kandelous Y, Nategh R, et al. No evidence of mammary tumor virus env gene-like sequences among Iranian women with breast cancer. Intervirology. 2014;57(6):353–56. doi: 10.1159/000366280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Al Moustafa A-E, Chen D, Ghabreau L, Akil N. Association between human papillomavirus and Epstein-Barr virus infections in human oral carcinogenesis. Med Hypotheses. 2009;73(2):184–86. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2009.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Lawson JS, Glenn WK. Multiple oncogenic viruses are present in human breast tissues before development of virus associated breast cancer. Infect Agent Cancer. 2017;12(1):55. doi: 10.1186/s13027-017-0165-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Horakova D, Bouchalova K, Cwiertka K, Stepanek L, Vlckova J, Kollarova H. Risks and protective factors for triple negative breast cancer with a focus on micronutrients and infections. Biomed Pap Med Fac Univ Palacky Olomouc Czech Repub. 2018;162(2):83–89. doi: 10.5507/bp.2018.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Wang F, Hou J, Shen Q, Yue Y, Xie F, Wang X, et al. Mouse mammary tumor virus-like virus infection and the risk of human breast cancer: a meta-analysis. Am J Transl Res. 2014;6:248–66. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Varn FS, Schaafsma E, Wang Y, Cheng C. Genomic characterization of six virus-associated cancers identifies changes in the tumor immune microenvironment and altered genetic programs. Cancer Res. 2018;78(22):6413–23. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-18-1342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Nik-Zainal S, Alexandrov Ludmil B, Wedge David C, Van Loo P, Greenman Christopher D, Raine K, Jones D, Hinton J, Marshall J, Stebbings L, et al. Mutational processes molding the genomes of 21 breast cancers. Cell. 2012;149(5):979–93. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.04.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Smid M, Rodríguez-González FG, Sieuwerts AM, Salgado R, Prager-Van der Smissen WJC, Vlugt-Daane M, Van Galen A, Nik-Zainal S, Staaf J, Brinkman AB, et al. Breast cancer genome and transcriptome integration implicates specific mutational signatures with immune cell infiltration. Nat Commun. 2016;7(1):12910. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Vernet-Tomas M, Mena M, Alemany L, Bravo I, De Sanjosé S, Nicolau P, et al. Human papillomavirus and breast cancer: no evidence of association in a Spanish set of cases. Anticancer Res. 2015;35:851–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.