Abstract

To develop improved automated subtyping approaches for Listeria monocytogenes, we characterized the discriminatory power of different restriction enzymes for ribotyping. When 15 different restriction enzymes were used for automated ribotyping of 16 selected L. monocytogenes isolates, the restriction enzymes EcoRI, PvuII, and XhoI showed high discriminatory ability (Simpson's index of discrimination > 0.900) and produced complete and reproducible restriction cut patterns. These three enzymes were thus evaluated for their ability to differentiate among isolates representing the two major serotype 4b epidemic clones, those having ribotype reference pattern DUP-1038 (51 isolates) and those having pattern DUP-1042 (20 isolates). Among these isolates, PvuII provided the highest discrimination for a single enzyme (nine different subtypes; index of discrimination = 0.518). A combination of PvuII and XhoI showed the highest discriminatory ability (index of discrimination = 0.590) for these isolates. A group of 44 DUP-1038 isolates and a group of 12 DUP-1042 isolates were identical to each other even when the combined data for all three enzymes were used. We conclude that automated ribotyping using different enzymes allows improved discrimination of L. monocytogenes isolates, including epidemic serotype 4b strains. We furthermore confirm that most of the isolates representing the genotypes linked to the two major epidemic L. monocytogenes clonal groups form two genetically homogeneous groups.

Listeria monocytogenes is a pathogen that causes a severe human food-borne disease (26). Molecular subtyping provides a crucial tool for the detection of human listeriosis outbreaks and single-source clusters, which are often difficult to detect by classical epidemiological methods without molecular subtyping-based surveillance data. Clinical characteristics of human listeriosis complicating the detection and tracking of outbreaks include a long incubation period (1 to 90 days) in comparison to that of many other food-borne diseases. L. monocytogenes has also been shown to persist in food plants and thus can lead to prolonged contamination of food products, which may be distributed over a wide geographic range. As a consequence, this organism may cause widespread multistate and possibly multicountry outbreaks, with relatively few related cases in each geographic area. Rapid and standardized subtyping methods for L. monocytogenes are thus particularly important for effective detection of human listeriosis outbreaks.

Various methods can be used to distinguish L. monocytogenes subtypes. Traditional subtyping methods include serotyping (34) and phage typing (23, 24). Serotyping is of restricted value because most human clinical L. monocytogenes isolates belong to only 3 (1/2a, 1/2b, and 4b) of the 13 serotypes known for this species (11, 22, 32, 33). Worldwide, most sporadic human cases and most outbreaks have reportedly been caused by L. monocytogenes serotype 4b (11, 30), including one of the more recent outbreaks in the United States (9, 10). Most of these epidemic isolates can be grouped into two closely related homogeneous groups (so-called “epidemic clones”) represented by two multilocus enzyme electrophoresis types and two ribotypes (14, 20, 27, 29, 37). These observations indicate that sensitive strain discrimination among serotype 4b strains is particularly crucial for surveillance and monitoring of human listeriosis cases.

The use of several subtyping methods, including multilocus enzyme electrophoresis, total DNA restriction endonuclease analysis, ribotyping, pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE), and random amplified polymorphic DNA analysis, for sensitive subtyping of L. monocytogenes has been explored by various groups (15). Many molecular typing methods offer the advantage of high discriminating ability and typeability and do not require specialized reagents such as typing sera and bacteriophages. PFGE using one or more enzymes is a commonly used and apparently highly discriminatory molecular subtyping method for L. monocytogenes (15). Major limitations of most molecular typing methods include a lack of standardization, a need for highly skilled technical staff, and significant hands-on time required for performance. Automation may allow laboratories to apply molecular typing more broadly. The RiboPrinter microbial characterization system (Qualicon Inc., Wilmington, Del.) is a completely automated subtyping system based on the principle of ribotyping (16). This system automates and standardizes all process steps required for ribotyping, from cell lysis to image analysis, and provides subtyping results within 8 h. While setup of an automated ribotyping laboratory requires considerable capital investment, for laboratories subtyping >1,500 isolates/year, costs on a per-isolate basis may be lower than for other, more labor-intensive subtyping methods (39).

Both manual and automated ribotyping methods have been widely used for subtyping of bacterial isolates (1, 2, 13, 14, 16, 19), detection and tracking of human and animal listeriosis cases and outbreaks (9, 36, 38), and tracking of L. monocytogenes contamination patterns in food processing plants (28). While the restriction enzymes EcoRI and PvuII have been used most commonly for ribotyping (13, 14), other restriction enzymes have also been used (2, 19). Some previous studies indicated that single-enzyme ribotyping may be less discriminatory than some other subtyping methods, particularly for L. monocytogenes serotype 1/2b and 4b strains (4, 35).

To develop improved automated subtyping approaches for L. monocytogenes, we characterized the discriminatory power of different restriction enzymes for automated ribotyping. We also specifically explored the use of ribotyping with different restriction enzymes to improve discrimination of isolates representing the two epidemic L. monocytogenes serotype 4b clonal groups.

Automated ribotyping.

Ribotyping was performed using the RiboPrinter microbial characterization system. Briefly, overnight bacterial cells were picked from brain heart infusion agar plates, suspended in sample buffer, inactivated by a heat kill step, and treated with lytic enzymes to release the DNA. The DNA was cut with a restriction enzyme, and the fragments were electrophoretically separated and simultaneously transferred to a membrane. A DNA probe for the Escherichia coli rrnB operon was then hybridized to the genomic DNA on the membrane. The genetic fingerprint was visualized and captured using a chemiluminescent detection system and a charge-coupled device camera. Analysis software automatically characterized and identified the digitalized image. Characterization consists of combining patterns within a specific similarity range to form a dynamic ribogroup that reflects the genetic relatedness of the isolates (6).

To allow the use of restriction enzymes requiring different time-temperature combinations for optimum performance (Table 1), the RiboPrinter system software has been modified to allow different digestion times (20 and 120 min) and temperatures (37 and 60°C). All restriction enzymes were obtained from New England Biolabs (Cambridge, Mass.).

TABLE 1.

Digestion time, incubation temperature, and discriminatory ability of 15 restriction enzymes used for characterization of 16 L. monocytogenes isolates

| Enzyme | Incubation temp (°C) | Digestion time (min) | No. of ribotypes among 16 isolates | SID |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PvuII | 37 | 20 | 15 | 0.992 |

| EcoRI | 37 | 20 | 12 | 0.950 |

| BstEII | 60 | 120 | 10 | 0.925 |

| BanI | 37 | 120 | 10 | 0.917 |

| XhoI | 37 | 120 | 10 | 0.900 |

| BglII | 37 | 120 | 8 | 0.883 |

| EagI | 37 | 120 | 9 | 0.883 |

| AseI | 37 | 120 | 7 | 0.817 |

| HincII | 37 | 120 | 5 | 0.792 |

| PstI | 37 | 120 | 6 | 0.617 |

| NcoI | 37 | 120 | 4 | 0.617 |

| XbaI | 37 | 120 | 1 | 0 |

| BsoBI | 60 | 120 | NDa | ND |

| ClaI | 37 | 120 | ND | ND |

| StyI | 37 | 120 | ND | ND |

ND, not determined. The enzymes BsoBI, ClaI, and StyI showed incomplete digests with spurious and variable high-molecular-weight bands, which did not allow assignment of distinct ribotypes.

Subtyping results with automated ribotyping using 15 restriction enzymes.

In an initial screening, 15 restriction enzymes were tested for their ability to discriminate 16 L. monocytogenes isolates. These isolates had previously been shown to represent 16 distinct EcoRI ribotypes through the use of manual ribotyping (7), which allowed for longer gel run times and better band separation. These initial isolates represented the EcoRI ribotypes dd 0647, dd 0653, dd 3581, dd 1049, dd 1288, dd 7674, dd 7730, dd 7745, dd 0566, dd 1070, dd 6439, dd 6481, dd 1966, dd 6296, dd 7696, and dd 6323 (7).

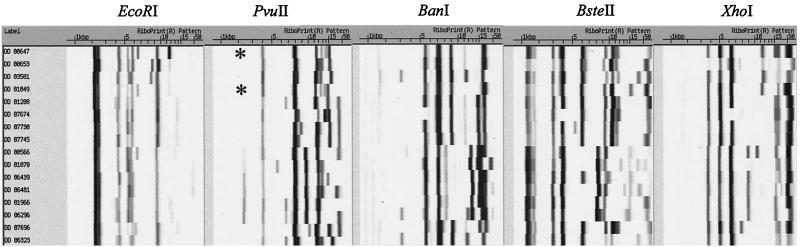

Three of the enzymes tested (BsoBI, ClaI, and StyI) consistently produced incomplete digests under the conditions used. Thus, patterns were not reproducible and these enzymes are not recommended for automated ribotyping of L. monocytogenes using the digestion conditions outlined in Table 1. With the remaining 12 restriction enzymes, we were able to differentiate between 1 and 15 different ribotypes (Table 1). The suitability of ribotyping for differentiation of strains was quantitated using Simpson's index of discrimination (SID) (18). The numerical value of this index indicates the discriminatory power of a given typing method by estimating the probability that two unrelated strains are differentiated by this method. As the numerical index approaches the maximum value of 1 (representing 100% discriminatory ability of a method), the probability increases that a given method will be able to discriminate between two unrelated strains. The five restriction enzymes with the highest discriminatory ability (SID ≥ 0.900) were PvuII, EcoRI, BstEII, BanI, and XhoI (Fig. 1). PvuII was the most discriminatory enzyme, yielding 15 different ribotypes. A combination of PvuII ribotypes with ribotypes created by either XhoI, BstEII, AseI, BanI, or BglIII allowed discrimination of all 16 isolates. No other combination of two restriction enzymes allowed discrimination of all 16 isolates. While this is the first study reporting comparison of a large number of restriction enzymes for subtyping of L. monocytogenes, our results are in general agreement with other studies. For example, Gendel and Ulaszek (13) showed that PvuII ribotyping discriminated more subtypes among a collection of 72 smoked salmon isolates than EcoRI ribotyping did. In earlier studies, EcoRI ribotyping was shown to be more discriminatory and suitable for L. monocytogenes subtyping than HindIII or HaeIII ribotyping (2, 19).

FIG. 1.

Ribotypes obtained with enzymes EcoRI, PvuII, BstEII, BanI, and XhoI for 16 genotypically distinctive L. monocytogenes isolates. The two isolates with indistinguishable PvuII ribotypes are marked with asterisks.

Discrimination of epidemic serotype 4b-associated genotypes using ribotyping with three selected restriction enzymes.

Sensitive subtyping of L. monocytogenes serotypes 4b and 1/2b is of particular importance, as these two serotypes form a distinctive subset (lineage) that is responsible for the majority of human listeriosis cases (22, 33, 37). Within the lineage containing serotype 1/2b and 4b strains, two distinct clonal groups show particular prevalence among human listeriosis cases and outbreaks (29, 37). Isolates representing one clonal group have previously been characterized as ribotype reference pattern DUP-1038 and ribotype dd 0647 (37). This clonal group was linked to human listeriosis outbreaks in France (8), Nova Scotia, Canada (31), Switzerland (3), and Los Angeles, Calif. (21). A second clonal group (ribotype reference pattern DUP-1042, ribotype dd 0653 [37]) has been linked to human listeriosis outbreaks in Boston (17), Massachusetts (12), and the United Kingdom (25). Reference patterns DUP-1042 and DUP-1038 each represent a group of closely related EcoRI ribotypes. These reference patterns were created by averaging individual closely related ribotype patterns obtained for multiple isolates. For example, DUP-1042 was previously shown to contain at least two closely related EcoRI ribotypes (dd 3581 and dd 0653) (7).

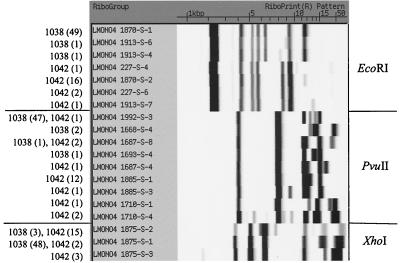

We used 71 L. monocytogenes isolates from humans, food, and other sources, representing the two major serotype 4b epidemic clones of L. monocytogenes, to further evaluate the discriminatory power of automated ribotyping using different restriction enzymes. Specifically, 51 and 20 of these isolates had previously been characterized as the EcoRI ribotype reference patterns DUP-1038 and DUP-1042, respectively. From the five restriction enzymes that allowed the most sensitive discrimination (SID ≥ 0.900) in our initial experiments on 16 diverse isolates, three enzymes (PvuII, EcoRI, and XhoI) were used to determine their ability to differentiate among these isolates. Restriction enzymes BanI and BstEII were not included because they produced weak low-molecular-weight bands, which often required manual refinement for accurate analysis. Enzymes PvuII, EcoRI, and XhoI produced more distinct patterns amenable to automated analysis and differentiation. Automated ribotyping with PvuII provided the highest discrimination (SID = 0.518) (Table 2) among these groups of closely related isolates. Combined analysis of ribotype patterns obtained with two enzymes allowed a significant increase in discriminatory power, and a combination of PvuII and XhoI data allowed for the highest discriminatory ability (Table 2). Forty-four of the 51 DUP-1038 as well as 12 of the 20 DUP-1042 isolates gave identical patterns with all three enzymes. Figure 2 shows the ribotype patterns obtained for the DUP-1038 and DUP-1042 isolates. DUP-1038 and DUP-1042 showed distinct ribotype patterns, and careful examination of EcoRI ribotype patterns allowed differentiation of four different ribotypes among DUP-1042 isolates and three different ribotypes among DUP-1038 isolates. The three DUP-1038 ribotypes differed by the presence or absence of weak bands in the 8- to 10-kb range, while the four DUP-1042 isolates differed by the presence or absence of weak bands in the 10- to 13-kb range. PvuII ribotype patterns, on the other hand, generally showed much more distinct differences in banding patterns.

TABLE 2.

Subtype discrimination among epidemic clones DUP-1038 (n = 51) and DUP-1042 (n = 20) by ribotyping with different restriction enzymes

| Enzyme or enzyme combination | Total no. of subtypes | SID | No. of subtypes

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DUP-1038 | DUP-1042 | |||

| PvuII | 9 | 0.518 | 4 | 7 |

| EcoRI | 7 | 0.478 | 3 | 4 |

| XhoI | 3 | 0.444 | 2 | 3 |

| PvuII/EcoRI | 13 | 0.538 | 4 | 9 |

| PvuII/XhoI | 11 | 0.590 | 5 | 7 |

| EcoRI/XhoI | 11 | 0.551 | 4 | 7 |

| PvuII/EcoRI/XhoI | 14 | 0.591 | 5 | 9 |

FIG. 2.

Ribotype patterns obtained with enzymes EcoRI, PvuII, and XhoI among all DUP-1038 and DUP-1042 isolates included in this study. The number of isolates within each ribotype (separated by DUP-1038 and DUP-1042 isolates) is indicated on the left.

Although considered a highly discriminatory subtyping method for L. monocytogenes (15), even PFGE with three different restriction enzymes often appears not to discriminate within these clonal groups, including among isolates from temporally and/or geographically distinct outbreaks. For example, isolates from the 1983 listeriosis outbreak in Massachusetts and isolates from the 1987–1989 outbreak in England were indistinguishable by PFGE using the restriction enzymes AscI, ApaI, and SmaI. Similarly, the same enzymes could not differentiate isolates from the outbreak in Los Angeles in 1985 and from the outbreak in Vaud, Switzerland, from 1983 to 1987 (5). Our results are thus consistent with previous results, which show the highly clonal nature of the serotype 4b clonal groups (5, 29). Sensitive subtyping of these isolates represents a significant challenge and may require novel, possibly genomics-based, approaches.

Conclusions.

Our results show that hierarchical ribotyping using different enzymes allows improved discrimination of L. monocytogenes isolates, including strains in the epidemic serotype 4b clonal groups. While surveillance and epidemiological investigations of human listeriosis cases may profit considerably from subtyping using multiple enzymes and automated ribotyping, currently more labor-intensive and possibly less standardized additional typing methods may be necessary to further discriminate strains in these clonal groups.

Acknowledgments

Some of the material described in this paper is based upon work supported by the USDA National Research Initiative under award no. 99-35201-8074 to M. Wiedmann.

We thank Elizabeth Mangiaterra of Qualicon Inc. for technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Allersberger F, Fritschel S J. Use of automated ribotyping of Austrian Listeria monocytogenes isolates to support epidemiological typing. J Microbiol Methods. 1999;35:237–244. doi: 10.1016/s0167-7012(99)00025-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baloga A O, Harlander S K. Comparison of methods for discrimination between strains of Listeria monocytogenes from epidemiological surveys. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1991;57:2324–2331. doi: 10.1128/aem.57.8.2324-2331.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bille J. Foodborne listeriosis: proceedings of a symposium on September 7, 1988, in Wiesbaden, FRG. Hamburg, Germany: Technomic Publishing Co., Inc.; 1990. Anatomy of a foodborne listeriosis outbreak; pp. 39–46. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bille J, Rocourt J. W.H.O. International Multicenter Listeria monocytogenes Subtyping Study: rationale and setup of the study. Int J Food Microbiol. 1996;32:251–262. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1605(96)01140-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brosch R, Brett M, Catimel B, Luchansky J B, Ojeniyi B, Rocourt J. Genomic fingerprinting of 80 strains from the WHO multicenter international typing study of Listeria monocytogenes via pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) Int J Food Microbiol. 1996;32:343–355. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1605(96)01147-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bruce J. Automated system rapidly identifies and characterizes microorganisms in food. Food Technol. 1996;50:77–81. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bruce J L, Hubner R J, Cole E M, McDowell C I, Webster J A. Sets of EcoRI fragments containing ribosomal RNA sequences are conserved among different strains of Listeria monocytogenes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:5229–5233. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.11.5229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carbonelle B, Cottin J, Parvery F, Chambreuil G, Kouyoumdjian S, Le Lirzin M, Cordier G, Vincent F. Epidemie de listeriose dans l'ouest de la France (1975–1976) Rev Epidemiol Sante Publique. 1978;26:451–467. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Multistate outbreak of listeriosis—United States, 1998. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1998;47:1085–1086. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Update: multistate outbreak of listeriosis—United States, 1988–1999. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1999;47:1117–1118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Farber J M, Peterkin P I. Listeria monocytogenes, a food-borne pathogen. Microbiol Rev. 1991;55:476–511. doi: 10.1128/mr.55.3.476-511.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fleming D W, Cochi S L, MacDonald K L, Brondum J, Hayes P S, Plikaytis B D, Holmes M B, Audurier A, Broome C V, Reingold A L. Pasteurized milk as a vehicle of infection in an outbreak of listeriosis. N Engl J Med. 1985;312:404–407. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198502143120704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gendel S M, Ulaszek J. Ribotype analysis of strain distribution in Listeria monocytogenes. J Food Prot. 2000;63:179–185. doi: 10.4315/0362-028x-63.2.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Graves L M, Swaminathan B, Reeves M W, Hunter S B, Weaver R E, Plikaytis B D, Schuchat A. Comparison of ribotyping and multilocus enzyme electrophoresis for subtyping of Listeria monocytogenes isolates. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:2936–2943. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.12.2936-2943.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Graves L M, Swaminathan B, Hunter S B. Subtyping Listeria monocytogenes. In: Ryser E T, Marth E H, editors. Listeria, listeriosis, and food safety. New York, N.Y: Marcel Dekker, Inc; 1999. pp. 279–297. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grimont F, Grimont P A D. Ribosomal ribonucleic acid gene restriction patterns as potential taxonomic tools. Ann Inst Pasteur/Microbiol (Paris) 1986;137B:165–175. doi: 10.1016/s0769-2609(86)80105-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ho J L, Shands K N, Friedland G, Eckind P, Fraser D W. An outbreak of type 4b Listeria monocytogenes infection involving patients from eight Boston hospitals. Arch Intern Med. 1986;146:520–524. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hunter P R, Gaston M A. Numerical index of the discriminatory ability of typing systems: an application of Simpson's index of diversity. J Clin Microbiol. 1988;26:2465–2466. doi: 10.1128/jcm.26.11.2465-2466.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jacquet C, Bille J, Rocourt J. Typing Listeria monocytogenes by restriction polymorphism of the ribosomal ribonucleic acid gene region. Zenbl Bakteriol. 1992;276:356–365. doi: 10.1016/s0934-8840(11)80542-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jacquet C, Catimel B, Brosch R, Buchrieser C, Dehaumont P, Goulet V, Lepoutre A, Veit P, Rocourt J. Investigations related to the epidemic strain involved in the French listeriosis outbreak in 1992. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:2242–2246. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.6.2242-2246.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Linnan M J, Mascola L, Lou X D, Goulet V, May S, Salminen C, Hird D W, Yonekora M L, Hayes P, Weaver R, Audurier A, Plikaytis B D, Fannin S L, Kleks A, Broome C V. Epidemic listeriosis associated with Mexican-style cheese. N Engl J Med. 1988;319:823–828. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198809293191303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McLauchlin J. Distribution of serovars of Listeria monocytogenes isolated from different categories of patients with listeriosis. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1990;9:210–213. doi: 10.1007/BF01963840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McLauchlin J, Audurier A, Taylor A G. The evaluation of a phage typing system for Listeria monocytogenes for use in epidemiological studies. J Med Microbiol. 1986;22:357–365. doi: 10.1099/00222615-22-4-357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McLauchlin J, Audurier A, Taylor A G. Aspects of the epidemiology of human Listeria monocytogenes infections in Britain 1967–1984; the use of serotyping and phage typing. J Med Microbiol. 1986;22:367–377. doi: 10.1099/00222615-22-4-367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McLauchlin J, Hall S M, Velani S K, Gilbert R J. Human listeriosis and pâté: a possible association. Br Med J. 1991;303:773–775. doi: 10.1136/bmj.303.6805.773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mead P, Slutsker L, Dietz V, McCaig L F, Bresee J S, Shapiro C, Griffin P M, Tauxe R V. Food-related illness and death in the United States. Emerg Infect Dis. 1999;5:607–625. doi: 10.3201/eid0505.990502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nørrung B, Skovgaard N. Application of multilocus enzyme electrophoresis in studies of the epidemiology of Listeria monocytogenes in Denmark. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:2817–2822. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.9.2817-2822.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Norton D M, McCarney M A, Gall K L, Scarlett J M, Boor K J, Wiedmann M. Molecular studies on the ecology of Listeria monocytogenes in the smoked fish processing industry. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2001;67:198–205. doi: 10.1128/AEM.67.1.198-205.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Piffaretti J-C, Kressebuch H, Aeschenbacher M, Bille J, Bannerman E, Musser J M, Selander R K, Rocourt J. Genetic characterization of clones of the bacterium Listeria monocytogenes causing epidemic disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:3818–3822. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.10.3818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rocourt J. Foodborne listeriosis: proceedings of a symposium on September 7, 1988, in Wiesbaden, FRG. Hamburg, Germany: Technomic Publishing Co., Inc.; 1988. Identification and typing of listeria; pp. 19–37. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schlech W F, III, Lavigne P M, Bortolussi R A, Allen A C, Haldane E V, Wort A J, Hightower A W, Johnson S E, King S H, Nicholls E S, Broome C V. Epidemic listeriosis—evidence for transmission by food. N Engl J Med. 1983;308:203–206. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198301273080407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schuchat A, Swaminathan B, Broome C V. Epidemiology of human listeriosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1991;4:169–183. doi: 10.1128/cmr.4.2.169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schwartz B, Hexter D, Broome C V, Hightower A W, Hirschhorn R B, Porter J D, Hayes P S, Bibbs W F, Lorber B, Faris D G. Investigation of an outbreak of listeriosis: new hypotheses for the etiology of epidemic Listeria monocytogenes infections. J Infect Dis. 1989;159:680–685. doi: 10.1093/infdis/159.4.680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Seeliger H P R, Hohne K. Serotyping of Listeria monocytogenes and related species. Methods Microbiol. 1979;13:31–49. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Swaminathan B, Hunter S B, Desmarchelier P M, Gerner-Smidt P, Graves L M, Harlander S, Hubner R, Jacquet C, Pedersen B, Reineccius K, Ridley A, Saunders N A, Webster J A. WHO-sponsored international collaborative study to evaluate methods for subtyping Listeria monocytogenes: restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis using ribotyping and Southern hybridization with two probes derived from L. monocytogenes chromosome. Int J Food Microbiol. 1996;32:263–278. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1605(96)01141-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wiedmann M, Czajka J, Bsat N, Bodis M, Smith M C, Divers T J, Batt C A. Diagnosis and epidemiological association of Listeria monocytogenes strains in two outbreaks of listerial encephalitis in small ruminants. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:991–996. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.4.991-996.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wiedmann M, Bruce J L, Keating C, Johnson A E, McDonough P L, Batt C A. Ribotypes and virulence gene polymorphisms suggest three distinct Listeria monocytogenes lineages with differences in pathogenic potential. Infect Immun. 1997;65:2707–2716. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.7.2707-2716.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wiedmann M, Mobini S, Cole J R, Jr, Watson C K, Jeffers G, Boor K J. Molecular investigation of a listeriosis outbreak in goats caused by an unusual strain of Listeria monocytogenes. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1999;215:369–371. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wiedmann M, Weilmeier D, Dineen S S, Ralyea R, Boor K J. Molecular and phenotypic characterization of Pseudomonas spp. isolated from milk. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2000;66:2085–2095. doi: 10.1128/aem.66.5.2085-2095.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]