ABSTRACT

The objectives of this study were to determine coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccination hesitancy and influencing factors in China, while broadening the applicability of the Vaccine Hesitancy Scale (VHS). A cross-sectional survey was conducted in China from 4th to 26th February 2021. Convenience sampling method was adopted to recruit participants. A total of 2,361 residents filled out the questionnaire. Confirmatory factor analysis was used on the validation set to confirm the latent structure that resulted from the exploratory factor analysis, which was conducted on the construction set. Multiple linear regression model analyses were used to identify significant associations between the identified the revised version of VHS subscales and hypothesized explanatory variables. Two subscales were identified within the VHS through data analysis, including “lack of confidence in the need for vaccines” and “aversion to the risk of side effects.” The results indicated that the hesitancy of the participants in our sample was both driven the two mainly aspects. In addition, more than 40% of the participants expressed hesitation in half of the items in VHS. This study characterized COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in China, and identified disparities in vaccine hesitancy by socio-demographic groups and knowledge about the vaccine. Knowledge of the vaccine was statistically linked to respondents’ answers to the clustered ‘lack of confidence’ and ‘risks perception’ items. Our results characterize Chinese citizens’ COVID-19 vaccine concerns and will inform targeted health communications.

KEYWORDS: COVID-19 vaccine, vaccine hesitancy, vaccine hesitancy scale, vaccine confidence, vaccine risk

Background

The multi-faceted catastrophic consequences associated with the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) spread1 have intensified international efforts in developing an effective prevention method to keep outbreaks under control. Vaccine supplies are limiting in some countries despite many available vaccines. With the supply of vaccines increases, nations will soon be administering vaccines to their citizens on a massive scale.2 Therefore, an understanding of the acceptability of a COVID-19 vaccine is urgently warranted in order to prepare for effective promotion strategies.

Despite the demonstrated effectiveness of vaccination programs, there is evidence that in many parts of the world substantial numbers of people question the need to become vaccinated, follow alternative vaccination schedules, and delay or refuse vaccination. These phenomena are manifestations of “vaccine hesitancy,” defined by the WHO in 2015 as a delay in acceptance or refusal of vaccination despite availability of vaccination services.3,4 The World Health Organization (WHO) recognized people’s hesitancy and reluctance become vaccinated as one of the top ten threats to global health in 2019.3 Vaccine hesitancy is likely to be a key barrier for the global roll-out of a COVID-19 vaccine. It is therefore important that we understand these harmful dynamics so that we may promptly counter them and communicate the importance of vaccination.

There are multiple factors influencing vaccine hesitancy, including policies, systems, economy, culture, psychology and behavior, among others.5 As the first country to face the COVID-19 outbreak, the vaccine hesitancy of the Chinese population is noteworthy. The Chinese government has announced that the COVID-19 vaccine will be provided free of charge to the entire population6 yet several studies have shown that some Chinese people do not trust the COVID-19 vaccine.7–9 Vaccine hesitancy is a complex public health issue in China. In the last decade, vaccine scandals and a series of reports about the serious side-effects of vaccination have increased vaccination hesitancy and distrust of the national immunization programs.10 The Chinese government has announced that receiving the COVID-19 vaccine will not be mandatory for all citizens and consequently vaccine hesitancy could be a major barrier to vaccine take-up. Therefore, there is an urgent need to conduct a study to investigate the hesitancy status and influencing factors of COVID-19 vaccination among Chinese residents, which will provide valuable information for mass vaccination efforts in China and abroad.

Appropriate measurement of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy is also a critical challenge. In recent years, measuring vaccine hesitancy has become a key focus of studies in the vaccination field.11,12 Several measurement scales have been developed to characterize vaccine hesitancy.13–18 In 2015, the WHO-SAGE Working Group on Vaccine hesitancy developed the Vaccine Hesitancy Scale (VHS), which aims to unify existing research on the many determinants of vaccine hesitancy in a workable framework and to standardize the measurement of vaccine attitudes.19 The VHS allows the comparison of parental levels of vaccine hesitancy geographically and temporally, while also facilitating exploration of relationships between vaccine hesitancy and socio-demographic factors in order to identify priority groups. The VHS has been validated in both Canadian20 and Guatemalan12 samples. The results of the VHS were found to be consistent with those of other scales (e.g. Vaccine Conspiracy Belief Scale), attitudes toward human papillomavirus vaccination, and history of vaccine refusals. Shapiro et al.18 concluded that the VHS is valid for identification of vaccine hesitant parents, whereas Domek et al.12 reported problems with its practical use in low and middle-income settings. Both studies identified a two-factor structure within the 10-item instrument, with one representing ‘lack of confidence’ in vaccines and the other representing the ‘risk perceptions’ of vaccine side-effects.

Our study aims to contribute to the VHS in two ways. First, we broaden the applicability of the VHS by focusing on vaccine hesitancy within the respondents themselves, rather than an exclusive focus on parental attitudes regarding childhood vaccines. As argued by Martin and Petrie,21 existing vaccine hesitancy scales focus either on particular subpopulations (e.g. parents or particular target-groups) or specific vaccines (e.g. HPV) but a single measure of general attitudes to vaccination may be the most efficient way to identify individuals with vaccine-related concerns. To broaden the scope of the VHS, we made modifications to the perspective and wording of the original scale, while retaining its conceptual meaning. Second, using this revised version, we examined COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among a convenience sample of the Chinese population and investigated the association between vaccine hesitancy and various respondent characteristics.

Methods

Ethics statement

This study protocol was approved by the institutional review board of Tongji Medical College of Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, China. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. Respondents were informed that their participation was voluntary, and consent was implied on the completion of the questionnaire.

Study participants and survey design

A cross-sectional survey was conducted in China from 4th to 26th February 2021. Convenience sampling strategy was adopted to recruit participants; the research team used WeChat (the most popular social media platform in China) to advertise and circulate the survey link to their network members. Network members were requested to distribute the survey invitation to all their contacts. Respondents were stratified according to the eastern (Beijing, Tianjin, Hebei, Liaoning, Shanghai, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Fujian, Shandong, Guangdong and Hainan), central (Shanxi, Jilin, Heilongjiang, Anhui, Jiangxi, Henan, Hubei, and Hunan) and western (Chongqing, Sichuan, Guizhou, Yunnan, Tibet, Shaanxi, Gansu, Qinghai, Ningxia, Xinjiang, Inner Mongolia, and Guangxi) regions of China. Participants were informed that their participation was voluntary, and consent was implied through their completion of the questionnaire. The inclusion criteria were as follows: 1) Chinese citizens who were at least 18 years old; 2) able to comprehend and read Chinese.

Instruments

The survey consisted of questions that assessed 1) demographic background, 2) knowledge of the COVID-19 and the COVID-19 vaccine, and 3) the vaccine hesitancy scale. Demographic information, including gender, age, highest educational level attained, religion, and employment status were collected. The knowledge of the COVID-19 and the COVID-19 vaccine assessed participants’ experiences, perceptions, and attitudes toward the COVID-19 vaccine.

We leveraged to send the hyperlink of the online questionnaire that was designed using “Survey Star (wjx.cn)” to participants. Survey Star can clearly record the number of questionnaires sent out and the completion of the participants. We calculate the response rate based on the system record. In addition, the WeChat account of each participant was connected to the Survey Star, and each WeChat account could only fill the questionnaire once to avoid repeated filling.

Vaccine hesitancy scale

Participants were asked to answer ten questions related to their confidence in COVID-19 vaccines on a five point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = neither agree nor disagree, 4 = agree, 5 = strongly agree). Three questions (questions five, nine and ten) were phrased negatively. In the original VHS, these ten items were intended to measure parents’ attitudes toward childhood vaccination and were phrased as such. We adapted these ten items to the first-person perspective so that they could be asked to anyone, without reference to children. For instance, the first item was changed from “Childhood vaccines are important for my child’s health” to “COVID-19 vaccines are important for my health.” Two authors (X.S. and J.F.) rephrased the items independently and in case of difference, it was jointly discussed which version was closest to the original meaning.

Statistical methods

To study the latent dimensions of the VHS, the dataset was randomly and evenly split into a construction and a validation set.20 Exploratory factor analysis was conducted on the construction set. Factors were extracted using varimax rotation. Subsequently, a confirmatory factor analysis was used on the validation set to confirm the latent structure that resulted from the exploratory factor analysis. Multiple regression analyses were used to identify significant associations between the identified VHS subscales and hypothesized explanatory variables. The analyses for this paper were generated using SAS software, Version 9.4 of the SAS System for Windows.

Results

Descriptive statistics

A total of 2,453 residents received the questionnaire. The response rate was 96.24% with 21 participants not responding and 71 questionnaires not completed. The remaining 2,361 complete questionnaires were used in our analysis.

Table 1 reports the socio-demographic characteristics of the 2,361 respondents. The mean age was 29.72 years (SD = 6.94) and majority of respondents were female (60.10%). Among the respondents, 421 (17.83%), 1470 (62.26%), and 470 (19.91%) were from eastern, central, and western China, respectively. Most respondents (89.24%) report having attained a bachelor’s degree or higher. More than half of the participants (57.05%) were unemployed.

Table 1.

Statistical description of study samples

| Variables | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Total | 2361 (100) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 942(39.90) |

| Female | 1419 (61.10) |

| Age group, y | |

| 18–44 | 1845 (78.14) |

| 45–59 | 369 (15.63) |

| >60 | 111(4.70) |

| Highest educational level | |

| Primary school or below | 68 (2.88) |

| middle school | 186 (7.88) |

| College degree or above | 2107 (89.24) |

| Region | |

| Eastern China | 421 (17.83) |

| Central China | 1470 (62.26) |

| Western China | 470 (19.91) |

| Employment status | |

| Employed | 1014 (42.95) |

| Unemployed | 1347 (57.05) |

| Relative or friend has received a COVID-19 vaccine | |

| Yes | 589 (24.95) |

| No | 1772 (75.05) |

| The primary way to get information about the COVID-19 vaccine | |

| Traditional Media (Television, Radio and Newspapers) | 1361 (57.65) |

| Emerging media (Weibo, WeChat and Interent news) | 1000 (42.35) |

| Have paid attention to the policy, process and location of COVID-19 vaccination | |

| Yes | 1818 (77.00) |

| No | 543 (23.00) |

| Have paid attention to the suitable and contraindicated population of COVID-19 vaccination | |

| Yes | 654 (27.83) |

| No | 1704 (72.17) |

| Have paid attention to the development progress of COVID-19 vaccination | |

| Yes | 1238 (52.44) |

| No | 1123 (47.56) |

| The COVID-19 has a large impact on your life | |

| Strongly disagree | 620 (26.26) |

| Disagree | 964 (40.83) |

| Not sure | 562 (23.80) |

| Agree | 124 (5.25) |

| Strongly agree | 91 (3.85) |

| Work exposure to COVID-19 at greater risk of infection | |

| Strongly disagree | 92 (3.90) |

| Disagree | 633 (26.81) |

| Not sure | 1073 (45.45) |

| Agree | 321 (13.60) |

| Strongly agree | 242 (10.25) |

| Support free vaccination for all people | |

| Strongly disagree | 606 (25.67) |

| Disagree | 945 (40.03) |

| Not sure | 640 (27.11) |

| Agree | 120 (5.08) |

| Strongly agree | 50 (2.12) |

Hesitancy score

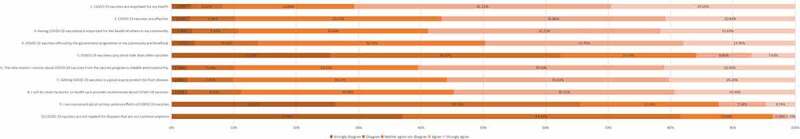

One in ten respondents either disagreed or were undecided about whether “COVID-19 vaccines are effective” (Question 2) and nearly one in five respondents did not fully reject the claim that “COVID-19 vaccines carry more risks than other vaccines” (Question 5). A much smaller proportion of respondents clearly opposed, ranging from 10.71% disagreeing that “vaccines are important for the health of others in my community” (Question 3). A majority of the respondents also disagreed with the statements “I am concerned about serious adverse effects of vaccines” (Question 9) and “Vaccines are not needed for diseases that are not common anymore” (Question 10). Items 5, 9 and 10 show an even distribution around “neither agree nor disagree,” standing in contrast the other seven items which showed a strongly skewed distribution toward “strongly agree” (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Distribution of answers to the 10 items of the vaccine hesitancy scale.

“Strongly disagree” and “disagree” were the expressions of vaccine hesitancy in question 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 7 and 8; while “Strongly agree” and “agree” were the expressions of hesitancy in question 5, 9 and 10. The aggregate levels of hesitancy over the ten items in the sample were calculated, depending on the definition of what counts as being ‘hesitant.’ If we consider the middle category ‘neither agree nor disagree’ as an expression of hesitancy, then 18.49% of the respondents made a vaccine hesitant choice (Question 10) among the 10 items, while 50.26% of the respondents reported hesitancy (Question 4). More than 40% of the participants expressed hesitation in half of the questions (questions 2,3,4,7 and 8). If we do not include the middle category in our definition of hesitancy, then much lower percentages become labeled as hesitant. Less than 10% of participants expressed hesitation in only three questions (questions 1, 9 and 10).

Internal structure of the modified VHS

For the ten items, we identified a two-factor structure with eigenvalues (i.e. the amount of variance in all the VHS survey items that is accounted for by that factor) of 5.34 for the ‘lack of confidence’ factor and 2.33 for the ‘risks perception’ factor, see Table 2. Together, these factors explained 76.72% of the total variance in the 10 survey items. Confirmatory factor analysis was performed for both the entire scale and the two-dimensional solutions, and clearly showed best goodness-of-fit for the 10-item version with two factors (RMSEA = 0.031, CFI = 0.939, TLI = 0.919). Thus, a two-factor structure, consisting of a ‘lack of confidence’ part with 7 items, and a ‘risks perception’ part with 3 items, showed best psychometric characteristics of the VHS. On a scale from 1 to 5 (with 5 maximal hesitancy), the average respondent scored 3.66 (SD = 0.12) for the lack of confidence factor and 2.15 (SD = 0.26) for risks, suggesting that the hesitancy of the average person in our sample was driven both by a lack of confidence in vaccines and the perception that vaccines are risky.

Table 2.

Rotated EFA factor loading pattern and CFA standardized regression weights for 10-item scale

| EFA loadings (N = 2361) |

CFA Standardized regression weights (N = 2361) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VHS factor 1: lack of confidence | VHS factor 2: risks | VHS factor 1: lack of confidence | VHS factor 2: risks | |

| Q1. COVID-19 vaccines are important for my health. | 0.828 | −0.063 | 0.791 | NA |

| Q2. COVID-19 vaccines are effective. | 0.896 | −0.014 | 0.872 | NA |

| Q3.Having COVID-19 vaccinated is important for the health of others in my community. | 0.868 | −0.01 | 0.84 | NA |

| Q4.COVID-19 vaccines offered by the government programme in my community are beneficial. | 0.878 | 0.001 | 0.855 | NA |

| Q5. COVID-19 vaccines carry more risks than other vaccines. | −0.018 | 0.882 | NA | 0.865 |

| Q6.The information I receive about the COVID-19 vaccines from the vaccine program is reliable and trustworthy. | 0.883 | −0.011 | 0.868 | NA |

| Q7.Getting the COVID-19 vaccines is a good way to protect me from disease. | 0.883 | 0.016 | 0.861 | NA |

| Q8.I will do what my doctor or health care provider recommends about the COVID-19 vaccines. | 0.877 | 0.023 | 0.808 | NA |

| Q9.I am concerned about serious adverse effects of the COVID-19 vaccines. | −0.001 | 0.914 | NA | 0.917 |

| Q10.COVID-19 vaccines are not needed for diseases that are not common anymore. | −0.006 | 0.844 | NA | 0.723 |

EFA = Exploratory Factor Analysis, CFA = Confirmatory Factor Analysis, VHS = Vaccine Hesitancy Scale.

Using regression analysis for the two VHS subscales, we found several variables that were statistically linked to respondents’ answers to the items pertaining to the ‘lack of confidence’ and ‘risks perception’ constructs (see Table 3). For the first construct, “Work exposure to the COVID-19 at greater risk of infection” and “have paid attention to the policy, process and location of the COVID-19 vaccination” are the major contributing factors to the lack of confidence in the vaccine. Regarding the second construct, gender, age, employment status, “relative or friend has received a COVID-19 vaccine,” “the primary way to get information about the COVID-19 vaccine,” “have paid attention to the suitable and contraindicated population of COVID-19 vaccination” and “have paid attention to the development of the COVID-19 vaccine” are the major factors contributing to the risk perception of the COVID-19 vaccine.

Table 3.

Associated factors with the lack of confidence in the need for the COVID-19 vaccine and aversion to the risk of side effects

| Variables | VHS factor 1: lack of confidence |

VHS factor 2: risks |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unstandardized Coefficients |

Standardized Coefficients |

p | 95%CI | Unstandardized Coefficients |

Standardized Coefficients |

p | 95%CI | |||

| β | SE | β | β | SE | β | |||||

| Constant | 24.129 | 1.084 | – | <.001 | 22.005 ~ 26.252 | 6.279 | 0.486 | – | <.001 | 5.326 ~ 7.232 |

| Gender (Ref: Male) | ||||||||||

| Female | 0.39 | 0.254 | 0.032 | 0.125 | −0.108 ~ 0.888 | −0.297 | 0.114 | −0.053 | 0.009 | −0.520 ~ −0.073 |

| Age group, y (Ref: 18–44) | ||||||||||

| 45–59 | 0.205 | 0.346 | 0.012 | 0.554 | −0.473 ~ 0.882 | −0.095 | 0.155 | −0.013 | 0.541 | −0.399 ~ 0.209 |

| >60 | 0.291 | 0.53 | 0.012 | 0.582 | −0.747 ~ 1.329 | 0.643 | 0.238 | 0.057 | 0.007 | 0.177 ~ 1.108 |

| Highest educational level (Ref: Primary school or below) | ||||||||||

| middle school | 1.507 | 0.864 | 0.067 | 0.081 | −0.186 ~ 3.199 | −0.757 | 0.388 | −0.075 | 0.051 | −1.517 ~ 0.003 |

| College degree or above | 0.36 | 0.753 | 0.018 | 0.633 | −1.116 ~ 1.835 | −0.542 | 0.338 | −0.062 | 0.109 | −1.204 ~ 0.121 |

| Region (Ref: Eastern China) | ||||||||||

| Central China | −0.42 | 0.343 | −0.034 | 0.22 | −1.092 ~ 0.251 | −0.153 | 0.154 | −0.027 | 0.319 | −0.455 ~ 0.148 |

| Western China | −0.253 | 0.405 | −0.017 | 0.532 | −1.046 ~ 0.541 | 0.073 | 0.182 | 0.011 | 0.687 | −0.283 ~ 0.429 |

| Employment status (Ref: Employed) | ||||||||||

| Unemployed | −0.399 | 0.261 | −0.033 | 0.127 | −0.911 ~ 0.113 | −0.257 | 0.117 | −0.047 | 0.029 | −0.486 ~ −0.027 |

| Relative or friend has received a COVID-19 vaccine (Ref: Yes) | ||||||||||

| No | −0.268 | 0.287 | −0.019 | 0.35 | −0.830 ~ 0.294 | 0.354 | 0.129 | 0.056 | 0.006 | 0.102 ~ 0.607 |

| The primary way to get information about the COVID-19 vaccine (Ref: Traditional Media) | ||||||||||

| Emerging media | 0.094 | 0.311 | 0.008 | 0.762 | −0.515 ~ 0.704 | 0.454 | 0.14 | 0.083 | 0.001 | 0.180 ~ 0.728 |

| Have paid attention to the policy, process and location of COVID-19 vaccination (Ref: Yes) | ||||||||||

| No | −0.779 | 0.298 | −0.054 | 0.009 | −1.364 ~ −0.195 | 0.214 | 0.134 | 0.033 | 0.11 | −0.048 ~ 0.476 |

| Have paid attention to the suitable and contraindicated population of COVID-19 vaccination (Ref: Yes) | ||||||||||

| No | −0.13 | 0.284 | −0.01 | 0.647 | −0.688 ~ 0.427 | 0.482 | 0.128 | 0.08 | <0.001 | 0.232 ~ 0.732 |

| Have paid attention to the development progress of COVID-19 vaccination (Ref: Yes) | ||||||||||

| No | −0.589 | 0.309 | −0.049 | 0.057 | −1.194 ~ 0.016 | −0.319 | 0.139 | −0.059 | 0.021 | −0.591 ~ −0.048 |

| The COVID-19 have a large impact on your life (Ref: Strongly disagree) | ||||||||||

| Disagree | −0.011 | 0.311 | −0.001 | 0.972 | −0.621 ~ 0.599 | 0.017 | 0.14 | 0.003 | 0.903 | −0.257 ~ 0.291 |

| Not sure | −0.345 | 0.352 | −0.024 | 0.327 | −1.035 ~ 0.345 | 0.214 | 0.158 | 0.034 | 0.176 | −0.096 ~ 0.523 |

| Agree | 0.764 | 0.594 | 0.028 | 0.198 | −0.399 ~ 1.927 | 0.359 | 0.266 | 0.03 | 0.178 | −0.163 ~ 0.882 |

| Strongly agree | 0.175 | 0.678 | 0.006 | 0.796 | −1.154 ~ 1.505 | 0.305 | 0.304 | 0.022 | 0.317 | −0.292 ~ 0.902 |

| Work exposure to COVID-19 at greater risk of infection (Ref: Strongly disagree) | ||||||||||

| Disagree | 1.529 | 0.676 | 0.112 | 0.024 | 0.204 ~ 2.853 | 0.162 | 0.303 | 0.026 | 0.594 | −0.433 ~ 0.756 |

| Not sure | 2.084 | 0.66 | 0.172 | 0.002 | 0.790 ~ 3.378 | 0.278 | 0.296 | 0.051 | 0.349 | −0.303 ~ 0.858 |

| Agree | 2.283 | 0.717 | 0.13 | 0.001 | 0.878 ~ 3.688 | 0.284 | 0.322 | 0.036 | 0.377 | −0.346 ~ 0.915 |

| Strongly agree | 2.253 | 0.741 | 0.113 | 0.002 | 0.800 ~ 3.706 | 0.05 | 0.333 | 0.006 | 0.882 | −0.603 ~ 0.702 |

| Support free vaccination for all people (Ref: Strongly disagree) | ||||||||||

| Disagree | −0.12 | 0.313 | −0.01 | 0.702 | −0.734 ~ 0.494 | 0.088 | 0.141 | 0.016 | 0.532 | −0.188 ~ 0.364 |

| Not sure | 0.438 | 0.341 | 0.032 | 0.199 | −0.230 ~ 1.106 | 0.21 | 0.153 | 0.034 | 0.17 | −0.090 ~ 0.510 |

| Agree | 2.309 | 0.601 | 0.084 | <0.001 | 1.132 ~ 3.486 | 0.253 | 0.27 | 0.02 | 0.349 | −0.276 ~ 0.781 |

| Strongly agree | −0.814 | 0.887 | −0.019 | 0.359 | −2.553 ~ 0.924 | 0.077 | 0.398 | 0.004 | 0.846 | −0.703 ~ 0.858 |

VHS = Vaccine Hesitancy Scale

Discussion

Our study based on a cross-sectional survey of Chinese citizens characterized COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and its influencing factors in China while simultaneously broadening the applicability of the VHS.

Firstly, despite a large majority of our sample showing favorable views toward the COVID-19 vaccination and a trust in its benefits, a substantial proportion of respondents expressed hesitancy toward the COVID-19 vaccination. More than 10% of participants expressed hesitation in seven items and more than 40% of the participants expressed hesitation in half of the items if we consider the response “neither agree nor disagree” an expression of hesitancy. The average respondent scored 3.66 (SD = 0.12) for the lack of confidence factor and 2.15 (SD = 0.26) for risks, indicating that both the “lack of confidence” and “risk perceptions” were reasons for the COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. KwokL et al.22 found that less than two-thirds of nurses intended to receive the COVID-19 vaccine when it becomes available in China and Fisher et al.23reported that approximately 30% adults were not sure they would accept vaccination. Therefore, vaccine hesitancy must be taken into consideration in the deployment of the COVID-19 vaccine.

Secondly, there are several factors influencing respondents’ hesitation about the COVID-19 vaccine. Those who reported that they “have paid attention to the policy, process and location of the COVID-19 vaccination” show greater confidence in the vaccine, which suggests that confidence in the vaccine may arise from one being more well-informed. In addition, participants who report “work exposure to the COVID-19 at greater risk of infection” were also more likely to show confidence in the vaccine. This is an interesting finding, with one possible explanation being that respondents at greater risk of infection would expect the vaccine to be more effective, thus increasing their confidence in the vaccine. A similar study conducted by Lin et al in China also showed that participants in a service occupation expressed higher vaccination intentions.8

Moreover, there are many factors that influence residents’ risk perception associated with the COVID-19. For example, men, the elderly and employed people were more likely to perceive the COVID-19 vaccine as risky. Those affirming the statements “relative or friend has received a COVID-19 vaccine” and “have paid attention to the suitable and contraindicated population of the COVID-19 vaccination” show an attenuated perception of risk, perhaps through increased knowledge of the COVID-19 vaccine. In Chinese participants, Mo et al.24 also reported that there was a positive association between greater knowledge about the COVID-19 vaccine and vaccination. In contrast, our respondents who report having paid attention to the development process of the COVID-19 vaccine which may lead residents to believe that the COVID-19 vaccine is a higher risk. When compared to the long development period of a typical vaccine, the accelerated the COVID-19 vaccine development effort may have lead the some members of the public to be less confident in the vaccine. Finally, our study found that “the primary way to get information about the COVID-19 vaccine was emerging media” could effectively reduce residents’ risks perception associated with the COVID-19 vaccine, suggesting that emerging media will play a more important role in the dissemination of vaccine information.

Thirdly, this study has broadened the applicability of the VHS. A standardized, validated and well-understood survey is an important instrument to counter vaccine hesitancy, but more research is needed for the VHS to be able to fulfill this purpose. Shapiro et al.20 identified two factors within the VHS, with a ‘lack of confidence’ underlying seven items and two items pointing at aversion for risks of vaccine-induced side effects. Both factors explained 67% of the variance observed in the ten items. Domek et al.12 had used a similar methodology and also identified two similar underlying constructs related to vaccine confidence and risks, explaining 76% of variation. Shapiro et al.20reported summary scores (on a scale from 1 to 5, with 5 maximal hesitancy) for the two factors of 3.07 for risks and 1.98 for lack of confidence. The similarity in findings suggests that our modified version of the VHS is usable as a substitute for the original scale for parents.

However, there are several aspects of the VHS that require attention. Besides lacking confidence and fearing side-effects, hesitancy may also be explained by various barriers to vaccination, religious or philosophical objections against vaccination, different time preferences (as side effects in the present need to be balanced against future benefits) and fear of needles among other considerations.25,26 International uptake of the VHS to examine vaccine hesitancy also warrants examination of measurement invariance of the survey items across cultures. We would also like to highlight the influential role that the middle response category on the Likert scale ‘neither agree nor disagree’ played in the results. Our results differed notably depending on whether this response was included or excluded in our definition of hesitancy. Some researchers have suggested that a neutral response should be located apart from the other response categories, because the mere position of this ballot can play an important role.27

Strengths and limitations

The study had some strengths. Firstly, we used a cross-sectional sample of the Chinese population, and the sample’s responses pointed at the aspects of the COVID-19 vaccination about which people were most hesitant (risks) and which pieces of information were most likely to be effective in countering anti-vaccine sentiments. Moreover, we explored a more generalized version of the VHS and found similar results as a comparable study in other countries using the more focused parental VHS.

Nonetheless the following limitations should be borne in mind. Firstly, our sample was relatively large compared to other studies but our study was still limited in its ability to identify the defining characteristics of the COVID-19 vaccine skeptics as well as their regional clustering. Some socio-economic characteristics that might have been of interest to better understand the COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy, for example ethnicity and religion, were not included in the questionnaire. In addition, the sample was a convenience sample and not nationally representative. Secondly, despite scales which used standardized questions and Likert scales such as the VHS being easier to analyze, they also masked respondent heterogeneity. Future studies should complement scales with other methods such as interviews that can probe deeper into a respondent’s underlying motivations. Notwithstanding the demographic groups that the present study identifies as being more likely to report vaccine-hesitant attitudes, further research is needed to identify the particular population groups in which vaccine hesitancy is most typical. It is also recommended to add other scales (e.g. the Vaccination Confidence Scale) or questions measuring attitudes to the COVID-19 vaccination or actual vaccination behavior to enable more in-depth validity testing.

Conclusions

As several COVID-19 vaccines begin being administered to humans, throughout the world vaccine hesitation continues to be a growing public health concern. Identifying and dealing with the COVID-19 vaccine hesitation could provide a reference for the COVID-19 immunization. The average respondent scored 3.66 (SD = 0.12) for the ‘lack of confidence’ factor and 2.15 (SD = 0.26) for ‘risks’ factor, and knowledge of the COVID-19 and the COVID-19 vaccine were associated with respondents’ intentions to receive the vaccine. Therefore, appropriate interventions are recommended to alter peoples’ hesitation about the COVID-19 vaccines and ultimately ensure the success of the pandemic prevention and control efforts. Specifically, national authorities need to provide accurate and timely publicity and education on the basis of ensuring adequate supplies of the COVID-19 vaccines, which could improve the residents’ willingness and confidence. It is necessary to adopt comprehensive measures and monitor residents’ hesitation of the COVID-19 vaccines over time in order to effectively promote the vaccinationc. In addition, the residents need to be actively informed about vaccines to reduce unnecessary fears about vaccine risks.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the participants in this study.

Funding Statement

This study was supported by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities [2020kfyXJJS059].

Authors’ contributions

X.S. and H.D. conceived and designed the study. J.F. and H.J. participated in the acquisition of data. X.S. and H.D. analyzed the data. J.F., R.D. and Z.L. gave advice on methodology. X.S. drafted the manuscript. H.D., H.J., R.D., Y.G., and C.L. revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. Y.G. is the guarantor of this work and had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for its integrity and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study protocol was approved by the institutional review board of Tongji Medical College of Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, China.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Data availability statement

Data may be made available by contacting the corresponding author.

References

- 1.Ye Q, Wang B, Mao J, Fu J, Shang S, Shu Q, Zhang T.. Epidemiological analysis of COVID-19 and practical experience from China. J Med Virol. 2020;92(7):755–69. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thanh LT, Andreadakis Z, Kumar A, Gómez RR, Tollefsen S, Saville M, The MS.. COVID-19 vaccine development landscape. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2020;19(5):305–06. doi: 10.1038/d41573-020-00073-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peng ZB, Wang DY, Yang J, Yang P, Zhang YY, Chen J, Chen T, Zheng YM, Zheng JD, Jiang SQ, et al. Current situation and related policies on the implementation and promotion of influenza vaccination, in China. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi. 2018;39(8):1045–50. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.0254-6450.2018.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dubé E, Gagnon D, Nickels E, Jeram S, Schuster M. Mapping vaccine hesitancy–country-specific characteristics of a global phenomenon. VACCINE. 2014;32(49):6649–54. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.09.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Du F, Chantler T, Francis MR, Sun FY, Zhang X, Han K, Rodewald L, Yu H, Tu S, Larson H, et al. The determinants of vaccine hesitancy in China: a cross-sectional study following the Changchun Changsheng vaccine incident. Vaccine. 2020;38(47):7464–71. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.09.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhou Y, Tang J, Zhang J, Wu Q. Impact of the coronavirus disease 2019 epidemic and a free influenza vaccine strategy on the willingness of residents to receive influenza vaccines in Shanghai, China. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2021:1–4. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2020.1871571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu R, Zhang Y, Nicholas S, Leng A, Maitland E, Wang J. COVID-19 vaccination willingness among Chinese adults under the free vaccination policy. Vaccines. 2021;9(3):292. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9030292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lin Y, Hu Z, Zhao Q, Alias H, Danaee M, Wong LP. Understanding COVID-19 vaccine demand and hesitancy: a nationwide online survey in China. PLOS Neglect Trop D. 2020;14(12):e8961. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0008961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang C, Han B, Zhao T, Liu H, Liu B, Chen L, Xie M, Liu J, Zheng H, Zhang S, et al. Vaccination willingness, vaccine hesitancy, and estimated coverage at the first round of COVID-19 vaccination in China: a national cross-sectional study. Vaccine. 2021;39(21):2833–42. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.04.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang R, Penders B, Horstman K. Addressing vaccine hesitancy in China: a scoping review of chinese scholarship. Vaccines (Basel). 2019;8:1. doi: 10.3390/vaccines8010002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Orr C, Beck AF. Measuring vaccine hesitancy in a minority community. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2017;56(8):784–88. doi: 10.1177/0009922816687328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Domek GJ, O’Leary ST, Bull S, Bronsert M, Contreras-Roldan IL, Bolaños VG, Kempe A, Asturias EJ. Measuring vaccine hesitancy: field testing the WHO SAGE Working Group on Vaccine Hesitancy survey tool in Guatemala. VACCINE. 2018;36(35):5273–81. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.07.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McRee AL, Brewer NT, Reiter PL, Gottlieb SL, Smith JS. The Carolina HPV immunization attitudes and beliefs scale (CHIAS): scale development and associations with intentions to vaccinate. SEX TRANSM DIS. 2010;37(4):234–39. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181c37e15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Opel DJ, Mangione-Smith R, Taylor JA, Korfiatis C, Wiese C, Catz S, Martin DP. Development of a survey to identify vaccine-hesitant parents: the parent attitudes about childhood vaccines survey. Hum Vaccin. 2011;7(4):419–25. doi: 10.4161/hv.7.4.14120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brown KF, Shanley R, Cowley NA, van Wijgerden J, Toff P, Falconer M, Ramsay M, Hudson MJ, Green J, Vincent CA, et al. Attitudinal and demographic predictors of measles, mumps and rubella (MMR) vaccine acceptance: development and validation of an evidence-based measurement instrument. VACCINE. 2011;29(8):1700–09. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zingg A, Siegrist M. Measuring people’s knowledge about vaccination: developing a one-dimensional scale. VACCINE. 2012;30(25):3771–77. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gilkey MB, Magnus BE, Reiter PL, McRee AL, Dempsey AF, Brewer NT. The vaccination confidence scale: a brief measure of parents’ vaccination beliefs. VACCINE. 2014;32(47):6259–65. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shapiro GK, Holding A, Perez S, Amsel R, Rosberger Z. Validation of the vaccine conspiracy beliefs scale. Papillomavirus Res. 2016;2:167–72. doi: 10.1016/j.pvr.2016.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Larson HJ, Jarrett C, Schulz WS, Chaudhuri M, Zhou Y, Dube E, Schuster M, MacDonald NE, Wilson R. Measuring vaccine hesitancy: the development of a survey tool. VACCINE. 2015;33(34):4165–75. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shapiro GK, Tatar O, Dube E, Amsel R, Knauper B, Naz A, Perez S, Rosberger Z. The vaccine hesitancy scale: psychometric properties and validation. VACCINE. 2018;36(5):660–67. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.12.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martin LR, Petrie KJ. Understanding the dimensions of anti-vaccination attitudes: the vaccination attitudes examination (VAX) scale. Ann Behav Med. 2017;51(5):652–60. doi: 10.1007/s12160-017-9888-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kwok KO, Li KK, Wei WI, Tang A, Wong S, Lee SS. Editor’s Choice: influenza vaccine uptake, COVID-19 vaccination intention and vaccine hesitancy among nurses: a survey. INT J NURS STUD. 2021;114:103854. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2020.103854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fisher KA, Bloomstone SJ, Walder J, Crawford S, Fouayzi H, Mazor KM. Attitudes toward a potential SARS-CoV-2 vaccine: a survey of U.S. adults. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173(12):964–73. doi: 10.7326/M20-3569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mo PK, Luo S, Wang S, Zhao J, Zhang G, Li L, Li L, Xie L, Lau J. Intention to receive the COVID-19 vaccination in China: application of the diffusion of innovations theory and the moderating role of openness to experience. Vaccines (Basel). 2021;9(2). doi: 10.3390/vaccines9020129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Luyten J, Vandevelde A, Van Damme P, Beutels P. Vaccination policy and ethical challenges posed by herd immunity, suboptimal uptake and subgroup targeting. Public Health Eth-UK. 2011;4(3):280–91. doi: 10.1093/phe/phr032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Luyten J, Desmet P, Dorgali V, Hens N, Beutels P. Kicking against the pricks: vaccine sceptics have a different social orientation. Eur J Public Health. 2014;24(2):310–14. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckt080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nadler JT, Weston R, Voyles EC. Stuck in the middle: the use and interpretation of mid-points in items on questionnaires. J Gen Psychol. 2015;142(2):71–89. doi: 10.1080/00221309.2014.994590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data may be made available by contacting the corresponding author.