ABSTRACT

Several COVID-19 vaccines have been developed in unprecedented time by research centers and pharmaceutical companies. This study aimed to determine COVID-19 vaccine acceptance and hesitancy rates and investigated the factors that influence vaccine acceptance and hesitancy. A cross-sectional research was conducted among adults in Saudi Arabia between January and March 2021 to determine willingness to receive a COVID-19 vaccine. A self-administered questionnaire was designed to explore the participants’ COVID-19 vaccine acceptance and hesitancy. Categorical variables are described by frequency and percentage. A cross-tabulation analysis using the chi-squared test was performed to find associations between sociodemographic characteristics and vaccine acceptance and hesitancy. Logistic regression analysis was performed for variables that were found to be significant by the chi-squared test. A descriptive analysis of the 531 participants showed that 61.8% were willing to get the COVID-19 vaccine, while 38.2% were not. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy was higher among women (44.9%), those 34–49 years of age (47.9%), those who were married (41.9%), employed (39.7%), had lower educational attainment (40%), and urban dwellers (40.8%). The main reason for COVID-19 vaccine acceptance was to protect oneself and others, while concerns about vaccine safety were the main reason for vaccine hesitancy. Statically significant associations were found between vaccine acceptance and age (p = .002) and gender (p = .03). Our study revealed a high prevalence of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy (38.2%). Several sociodemographic characteristics were related to hesitancy, which may hinder the promotion of vaccine uptake. Public health campaigns is recommended to promote COVID-19 vaccine uptake.

KEYWORDS: COVID-19 vaccine, vaccine uptake, vaccine acceptance, vaccine hesitancy, herd immunity

Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is a respiratory disease caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). This virus emerged in Wuhan, China in late December 20191 and rapidly spread worldwide; it was first detected in Saudi Arabia on March 2, 2020. In January 2020, the WHO declared the outbreak of COVID-19 as a pandemic.2 This pandemic has had a profound effect on health, the economy, and social life. In response to this global threat, many scientists are working to develop safe and effective vaccines, as no specific treatments have yet been approved. Fortunately, vaccines have recently been developed by pharmaceutical companies in an effort to alleviate the pandemic. However, the success of a COVID-19 vaccination program and the ability to attain herd immunity through vaccination will depend on the public’s willingness to be vaccinated, and from past experience, vaccine uptake can be a greater challenge than developing the vaccine.3 The time required to develop a COVID-19 vaccine was much shorter than previous vaccine development programs. This short duration has led to suspicion from antivaccination movements across the world.4 Furthermore, misinformation circulating on social media regarding the new vaccines has caused widespread fear of the vaccines in many populations. This has resulted in a significant variation in how the vaccines are perceived, as many see it as a relief and are looking forward to getting the COVID-19 vaccine, while a sizable proportion of the population is hesitant to be vaccinated. Vaccine hesitancy has become more common and has resulted in massive dissemination of infection.5 Furthermore, vaccine hesitancy has been identified by the WHO as one of the top ten threats to global health and is defined as a range of attitudes toward vaccination, from profound suspicion about vaccine efficacy, safety, and appropriateness to other minor concerns.6,7 Several COVID-19 vaccines have been developed by research centers and pharmaceutical companies. As these vaccines become available, research is needed to identify the determinants of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance and hesitancy to promote vaccine acceptance because vaccine acceptance has remained a critical issue for health policymakers. Several studies have identified factors that may influence vaccine acceptance and hesitancy and, therefore, vaccination decision-making. These factors include sociodemographic characteristics such as age, race, socioeconomic status, and geographic location,8–10 as well as other factors such as susceptibility to disease, expected severity, vaccine safety and efficacy, and trust in the vaccine.11–15 A recent study found that 11% of the participants viewed vaccines as more dangerous than the diseases they are designed to prevent.16 Worldwide, vaccine hesitancy, misperceptions, and misinformation present significant barriers to achieving vaccine coverage and the attainment of herd immunity.17,18 Herd immunity is achieved only when a sufficient proportion of the population becomes immune to a pathogen. Herd immunity is considered a primary goal of vaccination in addition to the direct immunity provided to vaccinated individuals.19 Hesitancy toward COVID-19 vaccines is understandable, as they were developed in a short period of time and approved under emergency use protocols; this has increased the public’s anxiety and worry, and could affect vaccine acceptance.4 Furthermore, misinformation disseminated by various media might substantially reduce people’s willingness to receive a COVID-19 vaccine.20 While there is considerable anticipation of COVID-19 vaccines, there is still no information about the determinants of vaccine acceptance and hesitancy in the Saudi Arabian population. This study aimed to assess key sociodemographic characteristics of vaccine hesitancy, determine the acceptance and hesitancy rates, and identify determinants influencing vaccine acceptance and hesitancy. Accordingly, recommendations should be made to positively influence people’s vaccination decisions by enhancing trust and vaccine acceptance to ensure high vaccination coverage in order to attain herd immunity. The findings of this study may help the government and ministry of health formulate strategies to implement mass vaccination programs for COVID-19 in Saudi Arabia.

Methods

Study design and setting

A web-based cross-sectional study was conducted among a representative sample of adults in Saudi Arabia between January and March 2021 to determine willingness to undergo COVID-19 vaccination. The online survey was conducted using the Survey Monkey platform.

Study population

The study population was recruited from throughout the country. All participants, irrespective of gender, nationality, educational level, or occupation, were included in the study. People less than 18 years old, visitors and nonresidents, and those who failed to answer all questions of the online survey were excluded from the study. People without internet access and those who did not have the required technical skills (and no facilitator) could not participate in this study.

Sample size

The sample size was calculated using the single population proportion formula:

where Zα/2 = 1.96 at a 95% confidence interval, p = 50% (as there is no previous published study in this study area), and d = 5%, which is the marginal error. Based on these values, the minimum sample size was 384 participants; however, we collected 531 samples.

2.4. Data collection techniques and methods

Sociodemographic characteristics and information on COVID-19 vaccine acceptance and hesitancy were collected from the participants. Due to the inability to conduct in-person interviews because of the pandemic, the data was collected through an online self-administered questionnaire using the Survey Monkey platform. Invitations to participate in the study, hosted by Google forms, were distributed on the WhatsApp communication platform, because the majority of the Saudi Arabian population uses this platform, regardless of age. The questionnaire was designed to assess key sociodemographic characteristics and explore the participants’ acceptance and hesitancy of COVID-19 vaccines. We used a modified questionnaire, and the contents and clarity were verified by public health experts at our institute. The questionnaire was pre-tested and then updated according to the pre-tester’s feedback. The survey was voluntary, and the participants were asked to agree to participate in the study before they answered any questions. The collected information will remain confidential.

Measures

Other than sociodemographic information, the following issues were assessed: Seasonal influenza vaccination status in the past season. Refusal to vaccinate themselves or their children in the past because they believed that the vaccination was useless or dangerous. Willingness to be vaccinated against COVID-19. Participants who responded that they would be willing were asked the following multiple-choice question: What is (are) the factor(s) that make you willing to get the vaccine? Participants who responded no were asked the following multiple-choice question: What is (are) the factor(s) that make you unwilling to get the vaccine? Participants were also asked if they thought the vaccine should be compulsory for everyone.

Data analysis

The data were analyzed using SPSS Statistics, version 25.0. Categorical variables are described by frequencies and percentages. A cross-tabulation analysis was performed to compare the determinants of vaccine acceptance and vaccine hesitancy with sociodemographic characteristics using the chi-squared test. Logistic regression analysis was performed for variables that were significant with the chi-squared test to assess their effect in a multivariate model and to determine independent predictors. A p-value of ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethical consideration

Ethical approval was waived by the Institutional Review Board of our institute since the research did not involve human subjects or animals.

Results

Characteristics of the participants

A total of 531 adults participated in this study. The majority of respondents were men (317; 59.7%), Saudi (522; 98.3%), urban dwellers (387; 72.9%), within the age group of 34–49 years (217; 40.9%), had achieved a university-level or postgraduate education (434; 81.8%), employed (390; 73.5%), married (342; 64.4%), and from middle-income households (257; 48.4%) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study population (n = 531)

| Sociodemographic characteristics | N (%) |

|---|---|

|

Age group (years) 18–33 34–49 ≥ 50 Gender Male Female Educational level Graduate/postgraduate Secondary Intermediate/primary Employment status Employed Unemployed Student Monthly household income in SAR Less than 10,000 10,000–20,000 20,000 or more Marital status Married Single Other Residency Urban Rural Nationality Saudi Non-Saudi |

209 (39.4) 217 (40.9) 105 (19.8) 317 (59.7) 214 (40.3) 434 (81.8) 87 (16.4) 10 (1.9) 390 (73.5) 23 (4.3) 118 (22.2) 256 (48.2) 257 (48.4) 18 (3.4) 342 (64.4) 184 (34.7) 5 (0.9) 387 (72.9) 144 (27.1) 522 (98.3) 9 (1.7) |

SAR: Saudi Arabian Riyal.

The following sociodemographic characteristics were associated with relatively high vaccine hesitancy: female gender, 34–49 years old, lower educational attainment, employed, married, and urban dwellers (Table 2).

Table 2.

Association between sociodemographic characteristics and COVID-19 vaccine acceptance/hesitancy

| Sociodemographic characteristics | Yes (%) | No (%) |

|---|---|---|

|

Age group (years) 18–33 34–49 ≥ 50 Gender Male Female Educational level Graduate/postgraduate Secondary Intermediate/primary Employment status Employed Unemployed Student Monthly household income in SAR Less than 10,000 10,000–20,000 20,000 or more Marital status Married Single Other Residency Urban Rural Nationality Saudi 522 Non-Saudi 9 |

145 (69.4%) 113 (52.1%) 66 (62.9%) 206 (65.0%) 118 (55.1%) 264 (60.8%) 55 (63.2%) 6 (60%) 235 (60.3%) 17 (73.9%) 72 (61.0%) 164 (64.1%) 148 (57.6%) 12 (66.7%) 208 (59.3%) 120 (65.2%) 5 (100%) 229 (59.2%) 95 (66.0%) 317 (60.8%) 6 (66.7%) |

64 (30.6%) 104 (47.9%) 39 (37.1%) 111 (35.0%) 96 (44.9%) 170 (39.2%) 32 (36.8%) 4 (40%) 155 (39.7%) 6 (26.1%) 46 (39.0%) 92 (35.9%) 109 (42.4%) 6 (33.3%) 143 (40.7%) 64 (34.8%) 0 (0%) 158 (40.8%) 49 (34.0) 204 (39.2%) 3 (33.3%) |

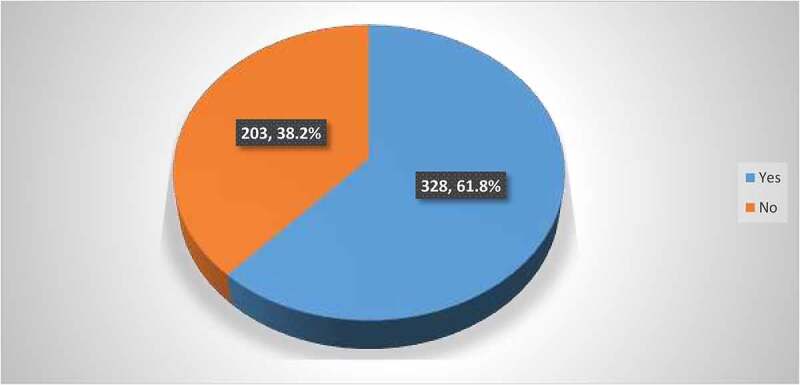

COVID-19 vaccine acceptance and hesitancy

Approximately two-thirds of the respondents (328; 61.8%) stated that they were interested in getting vaccinated against COVID-19, while 203 (38.2%) respondents stated that they do not want to get vaccinated (Figure 1). A minority of respondents (96; 18%) reported having received the seasonal influenza vaccine in the past season. Only 58 (10.9%) of the participants reported that they had refused vaccination in general for themselves or their child because they believed that vaccines are futile or hazardous. More than a third of the respondents (235; 44.3%) thought that the COVID-19 vaccine should be compulsory for everyone.

Figure 1.

Willingness to be vaccinated against COVID-19 (n = 531).

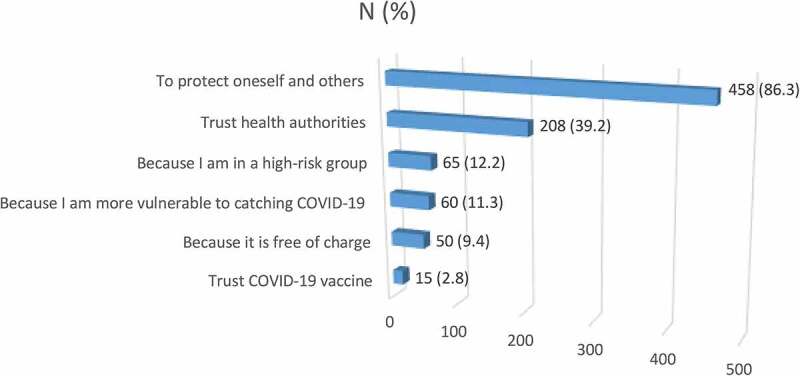

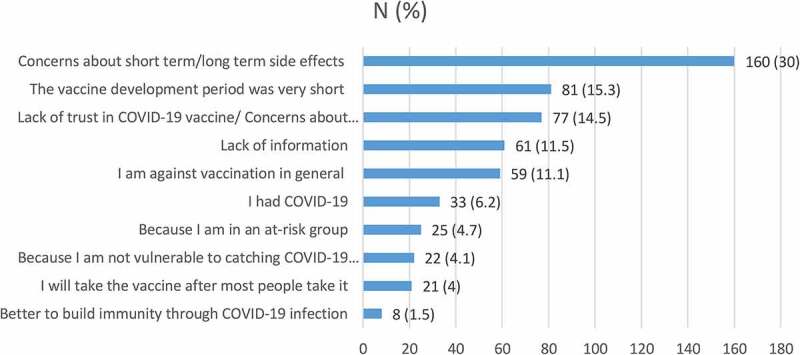

Factors associated with COVID-19 vaccine acceptance and hesitancy

The main reason for COVID-19 vaccine acceptance was to protect oneself and others (458; 86.3%), while trusting the vaccine was the last reason (15; 2.8%) (Figure 2). Almost one-third of the respondents were not interested in the COVID-19 vaccine due to their concerns about vaccine safety. Other reasons for not accepting the COVID-19 vaccine shown in Figure 3. The present study found statically significant associations between vaccine acceptance and age and gender, with p-values of 0.002 and 0.03, respectively. Overall, 69.4% of 18–33-year-olds were willing to be vaccinated against COVID-19, in comparison to 52.1% and 62.9% of 34–49-year-olds and those over 50, respectively. Regarding gender, 65.0% of men were willing to be vaccinated against COVID-19, in comparison to 55.1% of women. The binary logistic regression analysis found no predictive variables for vaccine acceptance or hesitancy.

Figure 2.

Reasons for accepting the COVID-19 vaccine (n = 531). (Participant could choose more than one option).

Figure 3.

Reasons for COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy (n = 531). (Participant could choose more than one option).

Discussion

Vaccination is the most effective public health method for infection prevention. However, vaccine hesitancy compromises its effectiveness, and for many years, vaccine uptake has been more challenging than vaccine development.21 The present study investigated COVID-19 vaccine acceptance and hesitancy and identified associated determinants among a representative sample in Saudi Arabia. This study was conducted after several COVID-19 vaccines had been developed. Regarding sociodemographic characteristics, the following groups expressed a lower intention to receive a COVID-19 vaccine: age 34–49 years, female gender, married, lower education attainment, employed, middle income, and urban dwellers. Interestingly, people who were employed, middle-aged, and urban dwellers expressed higher levels of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and lower vaccine acceptance; these findings are contrary to previous reports.22,23 This might be due to people’s recent perceptions of having a reduced risk of COVID-19 infection and severity. Furthermore, a considerable proportion of participants thought that non-medical factors, such as social and political pressures, led to the unprecedented rapid approval of the vaccines without obtaining safety and efficacy assurance.24 It is hoped that social media can positively impact vaccine uptake by disseminating accurate and evidence-based information about the vaccines. In this study, 61.8% of the 531 respondents reported that they would be willing to get vaccinated against COVID-19, while 38.2% reported COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. In our study, the percentage of people willing to get a COVID-19 vaccine was lower than COVID-19 vaccine acceptance rates found in other studies, which have ranged from 62% to 82%.25–29 However, our findings are higher than the rates reported by Fisher and colleagues.22 This variation could be due to the timing of the studies, as most of the previous surveys were conducted during the peak level of the pandemic and lockdown; thus, the respondents were more willing to get vaccinated. Unfortunately, in our study, the percentage of participants who were willing to get a COVID-19 vaccine is insufficient to attain herd immunity. At least 70% of the population needs to be vaccinated according to a pooled R0 estimate of 3.32 and assuming the vaccine has optimal effectiveness.30 Intensive work will be needed to convince hesitant people in order to reach this percentage and attain herd immunity. The present study revealed that the main reasons for accepting the COVID-19 vaccine were to protect oneself and others and trust in the Saudi health authorities. This finding is consistent with those of other recent studies.25,26,31 Regarding the main reasons for COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy, approximately one-third (30%) stated they were concerned about potential side effects and safety, followed by the rapid vaccine development and a lack of trust in the vaccine’s efficacy. These findings are comparable to those of previous reports.22,25,27 These results might be owing to the short duration that was needed to develop the vaccines, which generated suspicion from the world’s antivaccination movements. Therefore, transparent information regarding vaccine development, particularly their safety and efficacy, should be available to the community to ensure widespread immunization, because trust in the vaccine is an essential factor of vaccine uptake.32 Our study revealed the frustrating finding that only 18% of the respondents reported receiving the influenza vaccine during the past flu season. This percentage is lower than in a recent study that reported influenza vaccine uptake of 45%.33 However, a positive finding was that only 10.9% of the participants had previously refused other vaccines for themselves or their children because they believed vaccines to be ineffective or dangerous.

This study had some limitations. The inclusion of participants may have been affected by the questionnaire’s distribution through WhatsApp, as this may have missed people with lower educational levels and socioeconomic circumstances. Furthermore, the participant sample may not be representative of the entire country. This possibility of bias limits the generalizability of the results.

In conclusions, while the developed vaccines are a promising solution to this pandemic, widespread acceptance of vaccines is important. Our study revealed a high prevalence of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy (38.2%). Several sociodemographic factors were found to be associated with COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. Understanding the determinants of vaccine hesitancy will be vital for successful vaccination programs. Misinformation about the new vaccines that is disseminated via social media has heightened fear across many populations; this should be counteracted by transparent communication about vaccine development, safety, and efficacy, as a considerable proportion of the respondents indicated that their main reason for not accepting the vaccine is a lack of information about these issues. The media should be responsible and avoid disseminating any inaccurate information that could cause negative perceptions of the COVID-19 vaccines among the general public. The Saudi government and health authorities have made a considerable effort to make COVID-19 vaccines available, accessible, and at no cost. At present, people can schedule a vaccination appointment through the online COVID-19 vaccine portal. Vaccine accessibility and availability are among the most critical indicators of a vaccination program’s success because they positively affect actual vaccination uptake. Public health campaigns and vaccine acceptance and promotional messaging among hesitant groups by policymakers and public health workers are recommended to promote COVID-19 vaccine uptake.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the participants of the research study. We also would like to thank the administration and staff of the College of Medicine University of Bisha, particularly the Community Medicine Department for their continuous support.

Authorship contributions

AIOY and AMA contributed equally to proposal development, conception, design, data analysis, drafting, editing, and approving the final manuscript. WJHA, MMMA, TKAA, WFHH, TAAA, KAZA, AAAB contributed equally to proposal development, conception, collection, and data analysis and approving of the final manuscript.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

References

- 1.Guan WJ, Ni ZY, Hu Y, Liang WH, Ou CQ, He JX, Liu L, Shan H, Lei C-L, Hui DSC et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020. Apr 30;382(18):1708–20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization . Rolling updates on coronavirus disease (COVID-19); 2020. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/events-as-they-happen.

- 3.Schoch-Spana M, Brunson EK, Long R, Ruth A, Ravi SJ, Trotochaud M, Borio L, Brewer J, Buccina J, Connell N, et al. The public’s role in COVID-19 vaccination: human-centered recommendations to enhance pandemic vaccine awareness, access, and acceptance in the United States. Vaccine. 2020. Oct 29. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.10.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fadda M, Albanese E, Suggs LS.. When a COVID-19 vaccine is ready, will we all be ready for it?. Int J Public Health. 2020;65:711–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kata A. Anti-vaccine activists, Web 2.0, and the postmodern paradigm–An overview of tactics and tropes used online by the anti-vaccination movement. Vaccine. 2012. May 28;30(25):3778–89. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.11.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.MacDonald NE. Vaccine hesitancy: definition, scope and determinants. Vaccine. 2015. Aug 14;33(34):4161–64. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Siciliani L, Wild C, McKee M, Kringos D, Barry MM, Barros PP, De Maeseneer J, Murauskiene L, Ricciardi W. Strengthening vaccination programmes and health systems in the European Union: a framework for action. Health Policy. 2020. May 1;124(5):511–18. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2020.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abbas KM, Kang GJ, Chen D, Werre SR, Marathe A. Demographics, perceptions, and socioeconomic factors affecting influenza vaccination among adults in the United States. PeerJ. 2018. Jul;13(6):e5171. doi: 10.7717/peerj.5171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Almario CV, May FP, Maxwell AE, Ren W, Ponce NA, Spiegel BM. Persistent racial and ethnic disparities in flu vaccination coverage: results from a population-based study. Am J Infect Control. 2016. Sep 1;44(9):1004–09. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2016.03.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Galarce EM, Minsky S, Viswanath K. Socioeconomic status, demographics, beliefs and A (H1N1) vaccine uptake in the United States. Vaccine. 2011. Jul 18;29(32):5284–89. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bish A, Yardley L, Nicoll A, Michie S. Factors associated with uptake of vaccination against pandemic influenza: a systematic review. Vaccine. 2011. Sep 2;29(38):6472–84. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.06.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brewer NT, Chapman GB, Gibbons FX, Gerrard M, McCaul KD, Weinstein ND. Meta-analysis of the relationship between risk perception and health behavior: the example of vaccination. Health Psychol. 2007. Mar;26(2):136. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.26.2.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Glanz K, Rimer BK, Viswanath K, editors. Health behavior and health education: theory, research, and practice. San Francisco: John Wiley & Sons; 2008. Aug 28. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gerend MA, Shepherd JE. Predicting human papillomavirus vaccine uptake in young adult women: comparing the health belief model and theory of planned behavior. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2012. Oct 1;44(2):171–80. doi: 10.1007/s12160-012-9366-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang ZJ. Predicting young adults’ intentions to get the H1N1 vaccine: an integrated model. J Health Commun. 2015. Jan 2;20(1):69–79. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2014.904023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reinhart R. Fewer in US continue to see vaccines as important. Gallup. 2020. January;14:2020. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Larson HJ, Jarrett C, Eckersberger E, Smith DM, Paterson P. Understanding vaccine hesitancy around vaccines and vaccination from a global perspective: a systematic review of published literature, 2007–2012. Vaccine. 2014. Apr 17;32(19):2150–59. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.01.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lane S, MacDonald NE, Marti M, Dumolard L. Vaccine hesitancy around the globe: analysis of three years of WHO/UNICEF joint reporting form data-2015–2017. Vaccine. 2018. Jun 18;36(26):3861–67. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.03.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fine P, Eames K, Heymann DL. “Herd immunity”: a rough guide. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:911–16. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir007. PMID: 21427399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cornwall W. Officials gird for a war on vaccine misinformation. Science. 2020;369:14–19. doi: 10.1126/science.369.6499.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Piltch-Loeb R, DiClemente R. The vaccine uptake continuum: applying social science theory to shift vaccine hesitancy. Vaccines. 2020. Mar;8(1):76. doi: 10.3390/vaccines8010076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fisher KA, Bloomstone SJ, Walder J, Crawford S, Fouayzi H, Mazor KM. Attitudes toward a potential SARS-CoV-2 vaccine: a survey of US adults. Ann Inter Me. 2020. Dec 15;173(12):964–73. doi: 10.7326/M20-3569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leng A, Maitland E, Wang S, Nicholas S, Liu R, Wang J. Individual preferences for COVID-19 vaccination in China. Vaccine. 2020. Dec 5;39(2):247–54. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Newsroom KF Poll: most Americans worry political pressure will lead to premature approval of a COVID-19 vaccine. Half Say They Would Not Get a Free Vaccine Approved Before Election Day; 2020; San Francisco, CA, USA: KFF; Kaiser Family Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Padhi BK, Al-Mohaithef M. Determinants of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance in Saudi Arabia: a web-based national survey. medRxiv. 2020. Jan 1:13;1657–1663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harapan H, Wagner AL, Yufika A, Winardi W, Anwar S, Gan AK, Setiawan AM, Rajamoorthy Y, Sofyan H, Mudatsir M. Acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine in southeast Asia: a cross-sectional study in Indonesia. Front Public Health. 2020;8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Neumann-Bohme S, Varghese NE, Sabat I, Barros PP, Brouwer W, van Exel J, Schreyogg J, Stargardt T. Once we have it, will we use it? A European survey on willingness to be vaccinated against COVID-19. The Eur J Health Economic. 2020;1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lazarus JV, Ratzan SC, Palayew A, Gostin LO, Larson HJ, Rabin K, Kimball S, El-Mohandes A. A global survey of potential acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine. Nat Med. 2020. Oct;20:1–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Khubchandani J, Sharma S, Price JH, Wiblishauser MJ, Sharma M, Webb FJCOVID-19. Vaccination hesitancy in the United States: a rapid national assessment. Journal of Community Health. 2021. Jan;3:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alimohamadi Y, Taghdir M, Sepandi M. Estimate of the basic reproduction number for COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Preventive Med Public Health. 2020. May;53(3):151. doi: 10.3961/jpmph.20.076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bell S, Clarke R, Mounier-Jack S, Walker JL, Parents’ PP. guardians’ views on the acceptability of a future COVID-19 vaccine: a multi-methods study in England. Vaccine. 2020. Nov 17;38(49):7789–98. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.10.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Larson HJ, Clarke RM, Jarrett C, Eckersberger E, Levine Z, Schulz WS, Paterson P. Measuring trust in vaccination: a systematic review. Human Vaccines Immunotherap. 2018. Jul 3;14(7):1599–609. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2018.1459252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Annual Influenza Vaccination Coverage Estimates for the United States. FluVaxView. 2019. June 7. [Google Scholar]