Abstract

The corpora lutea (CL) are endocrine glands that form in the ovary after ovulation and secrete the steroid hormone, progesterone (P4). P4 plays a critical role in estrous and menstrual cycles, implantation, and pregnancy. The incomplete rodent estrous cycle stably lasts 4–5 days and its morphological features can be distinguished during each estrous cycle stage. In rat ovaries, there are two main types of CL: newly formed ones due to the current ovulation (new CL), and CL remaining from prior estrous cycles (old CL). In the luteal regression process, CL were almost fully regressed after four estrous cycles in Sprague-Dawley rats. P4 secretion from CL in rodents is regulated by the balance between synthesis and catabolism. In general, luteal toxicity should be evaluated by considering antemortem and postmortem data. Daily vaginal smear observations provided useful information on luteal toxicity. In histopathological examinations, not only the ovaries and CL but also other related tissues and organs including the uterus, vagina, mammary gland, and adrenal glands, must be carefully examined for exploring luteal changes. In this review, histological and functional characteristics of CL in rats are summarized, and representative luteal toxicity changes are presented for improved luteal toxicity evaluation in preclinical toxicity research.

Keywords: corpora lutea, luteal toxicity, ovary, progesterone, rat

Introduction

The function of female reproductive organs is regulated across estrous cycle by the hypothalamic–pituitary–gonadal axis through complex feedback loops. These feedback systems can be perturbed by ovarian toxicants accompanied by abnormal hormone secretion, disrupted estrous or menstrual cycles, or identifiable histopathological changes in the reproductive tract; detailed histopathological evaluations can help establish their underlying mechanisms1. Understanding the morphology and function of these structures can help clarify the mechanisms pertaining to ovarian toxicants.

The ovary has two distinct functional components required for estrous cyclicity: the follicles and corpora lutea (CL). The follicles play a critical role in ovulation2, while CL are an endocrine gland that forms after ovulation3. The CL have several unique features. The first is their temporal nature: CL have a limited lifespan in many species, depending on the fate of the oocyte released by the preceding ovulatory follicle2. Second, they synthesize and secrete progesterone (P4). P4 has numerous biological effects on the reproductive tract, including facilitating implantation in the uterine endometrium and supporting the uterine environment to sustain pregnancy2. Third, there is a marked species diversity in the mechanisms that evolved for controlling the structure and function of CL. In primates and domestic animals, CL develop and function for a finite interval (approximately 2 weeks) during the ovarian cycle. However, rodents do not form truly functional CL during the incomplete estrous cycle unless mating results in pregnancy or pseudopregnancy2.

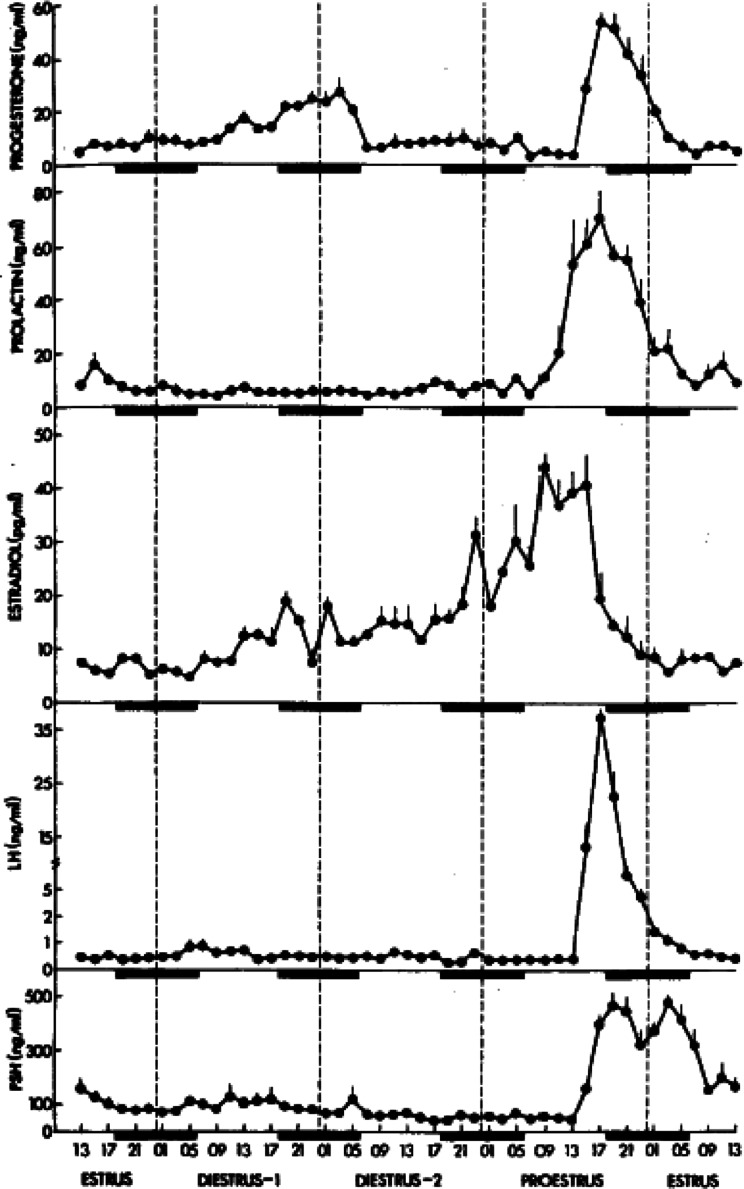

Rodents are generally used for ovarian toxicity evaluations. The incomplete rodent estrous cycle stably lasts 4 to 5 days and is clearly distinguished by its morphological features during each estrous cycle stage4. In addition, cyclic changes in the levels of reproductive hormones, such as P4, estradiol-17β, follicle-stimulating hormone, luteinizing hormone (LH), and prolactin (PRL), are common (Fig. 1), and each estrous stage can be recognized in vaginal smear observations5, 6, 7. Although some aspects of reproductive regulatory mechanisms differ between rodents and humans, an understanding of these differences will allow the assessment of the risk of human ovarian toxicity.

Fig. 1.

Time-course changes in reproductive hormone levels; progesterone (P4), prolactin (PRL), estradiol, luteinizing hormone (LH), and follicle-stimulating hormone. The rat estrous cycle is subdivided into four subsequent phases, proestrus, estrus, metestrus/diestrus 1, and diestrus/diestrus 2. Reproduced with permission from the Oxford University Press; taken from Smith et al. Endocrinology. 96: 219–226. 1975.

In this review, the histological and functional characteristics of CL in rats are summarized, and representative luteal toxicity changes are presented for improving luteal toxicity evaluation in preclinical toxicity research.

Key factors in luteinization after ovulation

Ovulation and subsequent luteinization represent a complicated cascade of molecular events2, 8. During ovulation, progesterone receptor (PR) and cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) are key mediators8. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ) is a target of PR regulation in preovulatory follicles and controls ovulation9. Luteinization is comprised of two major processes: 1) termination of proliferation with rapid hypertrophy and differentiation of steroidogenic follicular cells (granulosa cells and theca cells) into luteal cells, and 2) the rapid growth of blood vessels (angiogenesis) into the previous granulosa layer of the follicle2. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), angiopoietins, and platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) play critical roles in luteal angiogenesis2, 10.

Histological characteristics of CL in rats

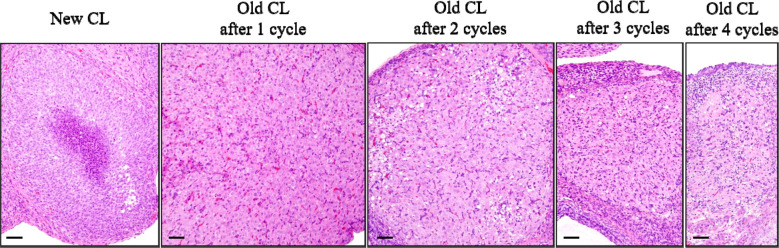

In rat ovaries, multiple types of CL are generated, which then regress over several estrous cycles. There are two main types of CL: those that are newly formed by the current ovulation (new CL), and CL remaining from prior estrous cycles (old CL)4, 11. The histological characteristics of new CL and old CL are well described in the literature4, 12, 13. Briefly, new CL during the estrus to diestrus stages are characterized by basophilic cytoplasm. At the diestrus stage, the new CL attain their largest size with polygonal and finely vacuolated luteal cells. At the proestrus stage, the basophilic CL become eosinophilic and begin luteolysis, characterized by apoptosis of individual luteal cells, and vacuolation may be observed in these CL12. Old CL were also eosinophilic. However, they showed decreased cytoplasmic vacuolation and increased fibrous tissue composition compared to the new CL. During the luteal regression process, CL almost fully regressed after four estrous cycles in Sprague-Dawley (SD) rats14 (Fig. 2). However, luteal regression begins approximately two or more stages later in Wistar Hannover (WH) rats13; therefore, the regression is slower in WH rats than in SD rats.

Fig. 2.

Time-course histological changes of luteal regression. New corpora lutea (CL) were composed of luteal cells with a small amount of basophilic cytoplasm. Old CL, after 1 cycle, reached maximum size and were characterized by luteal cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and distinct cell borders, as well as indistinct interstitial cells. Old CL after 2 cycles were smaller than Old CL after 1 cycle, had conspicuous interstitium, and luteal cell borders were slightly indistinct. Old CL after 3 cycles had more conspicuous interstitium and were smaller than Old CL after 2 cycles. After 4 cycles of new formation, CL almost completely regressed. Bars represent 50 µm. Modified from Taketa et al. Toxicol Pathol. 39: 372–380. 2011.

P4 secretion during the incomplete estrous cycle in rats

Rodents have two discrete time points in the estrous cycle during which P4 increases. The first occurs in the afternoon of the proestrus stage, and the second occurs from the metestrus to diestrus stages6, 15 (Fig. 1). Preovulatory P4 is secreted at the proestrus stage by Graafian follicles, depending on LH. In metestrus and diestrus, P4 is secreted from CL, but independently of LH. The luteal secretion of P4 from the metestrus to the diestrus stages reaches peak values at midnight of metestrus before falling to basal levels as a result of luteolysis5. The drop-off in P4 marks the beginning of the functional regression of CL.

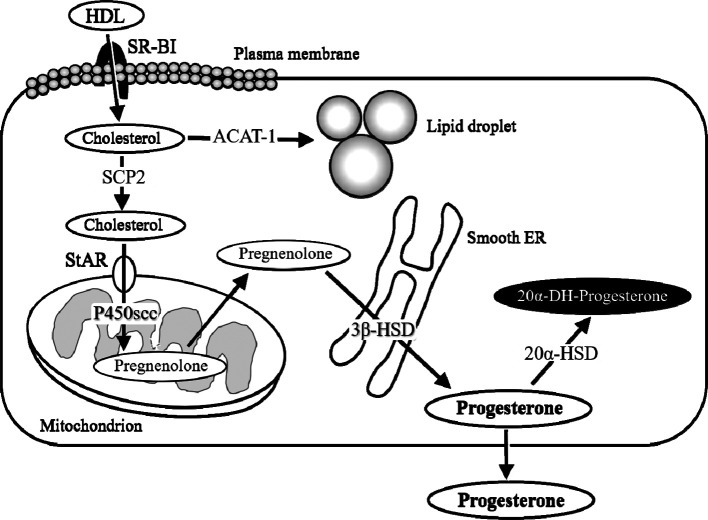

P4 biosynthesis in the rat CL

P4 biosynthesis in CL is divided into the following steps: uptake, synthesis, and transport of cholesterol, and the processing of cholesterol into P4, as summarized in Fig. 3. Cholesterol is preferentially obtained from circulatory high- and low-density lipoproteins (HDL and LDL, respectively); HDL is the main source of cholesterol for CL in rodents16, 17. Scavenger receptor class B type I (SR-BI) is considered an authentic HDL receptor that mediates the selective uptake of HDL-derived cholesterol esters18. After uptake, the storage and turnover of free cholesterol in lipid droplets are processed through acyl-coenzyme A-cholesterol acyl transferase-catalyzed cholesterol ester formation2. Intracellular transport of hydrophobic free cholesterol appears to be actively directed by various proteins, including sterol carrier proteins2. These cholesterol esters are transported to the outer mitochondrial membrane and then to the inner mitochondrial membrane by several proteins, including steroidogenic acute regulatory protein (StAR)19. Once cholesterol reaches the inner mitochondrial membrane, its transformation into P4 begins. In this step, mitochondrial P450 cholesterol side-chain cleavage (P450scc) and 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (3β-HSD), located in the smooth endoplasmic reticulum, play major roles20, 21.

Fig. 3.

A schema of the progesterone (P4) biosynthesis process in the luteal cells. High-density lipoprotein (HDL) is the main source of cholesterol for CL in rodents. Scavenger receptor class B type I (SR-BI) is the authentic HDL receptor mediating the selective uptake of HDL-derived cholesterol esters. After uptake, the storage and turnover of free cholesterol in lipid droplets is processed through acyl coenzyme A-cholesterol acyl transferase (ACAT-1)-catalyzed cholesterol ester formation. Intracellular transport of hydrophobic, free cholesterol appears to be actively directed by proteins including sterol carrier proteins (SCP2). The cholesterol esters are transported to the outer mitochondrial membrane and then to the inner membrane by proteins including steroidogenic acute regulatory protein (StAR). Once the cholesterol reaches the inner mitochondrial membrane, mitochondrial P450 cholesterol side-chain cleavage (P450scc) transforms cholesterol into pregnenolone and 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (3β-HSD) in the smooth endoplasmic reticulum (ER), and transforms pregnenolone into P4. In CL with functional regression, 20α-hyroxysteroid dehydrogenase (20α-HSD) catabolizes P4 into the inactive progestin, 20α-dihydroprogesterone (20α-DHP).

P4 secretion from CL in rodents is regulated by a balance between synthesis and catabolism. It depends not only on the amount of P4 synthesized by the luteal cells but also on the expression of the enzyme 20α-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (20α-HSD), which catabolizes P4 into the inactive progestin, 20α-dihydroprogesterone (20α-DHP). Once 20α-HSD is expressed in CL as the initial step in functional luteolysis, P4 secretion is reduced, and 20α-DHP becomes the major steroid secreted by luteal cells22.

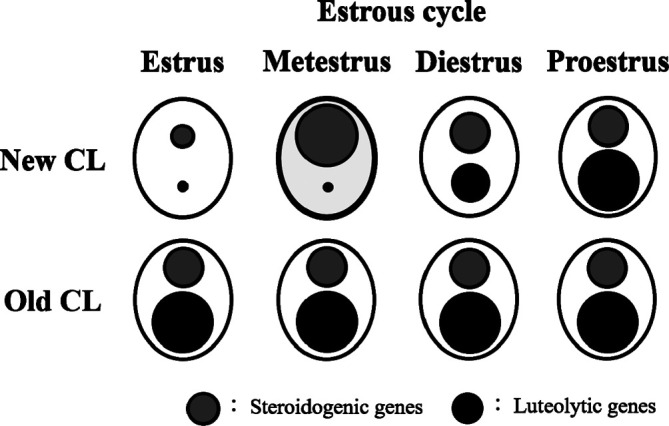

The steroidogenic and luteolytic gene expression in the new CL dramatically changes during the estrous cycle. An overview of luteal gene expression during the estrous cycle is shown in Fig. 423. The new CL at the metestrus stage, which can secrete P4, show notably high steroidogenic (e.g., SR-BI, StAR, P450scc, and 3β-HSD) and low luteolytic gene (e.g., 20α-HSD and PGF2α-R) levels23. Luteolytic genes in the new CL were remarkably low at the estrus and metestrus stages, and gradually increase thereafter23. In the old CL, relatively high steroidogenic and markedly high luteolytic gene levels were consistently maintained throughout the estrous cycle23.

Fig. 4.

Overview of steroidogenic and luteolytic gene levels in new and old CL across the estrous cycle in rats. The sizes of the circles represent the levels of steroidogenic genes (gray circles) and luteolytic genes (black circles). The new CL at metestrus (bold line), which have the capacity for P4 secretion, showed notably high steroidogenic gene and low luteolytic gene levels. Luteolytic genes in the new CL were remarkably low at estrus and metestrus, and gradually increased thereafter. In the old CL, relatively high steroidogenic and markedly high luteolytic gene levels were consistently retained throughout the estrous cycle. Reproduced with permission from the Elsevier; taken from Taketa et al. Exp Toxicol Pathol. 64: 775–782. 2012.

Roles of PRL in luteal function in rodents

In rodents, PRL plays a crucial role in both luteal activation and luteolysis. PRL directly stimulates luteal P4 production by upregulating steroidogenic enzymes such as 3β-HSD and preventing P4 degradation by inhibiting 20α-HSD expression2. In contrast, PRL induces luteolysis. A proestrus preovulatory PRL surge induces luteal cell apoptosis by activating the Fas pathway and functional regression of CL and facilitating the recruitment of monocytes/macrophages into CL24. Therefore, PRL-activating agents may induce a luteotrophic effect, whereas PRL-inhibiting agents may disrupt the luteal regression process.

Functional and structural regression of the rat CL

Luteal regression is divided into functional and structural regressions. The decrease in P4 is a marker of functional regression of CL in rodents. Structural regression occurs after the initial decline in P4 and is morphologically observed as luteal cell apoptosis24. In functional regression, several factors, including prostaglandin F2 alpha (PGF2α) and LH, have been implicated in the downregulation of luteal P4 production25, 26. PGF2α stimulates the expression and activity of 20α-HSD27. Meanwhile, several signals, including PRL, PGF2α, tumor necrosis factor-alpha, and Fas ligand, have been implicated in the induction of cell death that is required for the structural regression of CL24, 28, 29, 30.

Practical approaches for the evaluation of luteal toxicity in rats

In general, luteal toxicity should be evaluated by considering antemortem data including clinical signs, body weight, food consumption, and clinical pathology, as well as postmortem data including gross pathology, organ weight, and histopathological examination of the female reproductive organs and other related organs such as the pituitary, mammary, and adrenal glands. The age of rats should be considered for the evaluation because age significantly impacts the histological appearance of the female reproductive system and can be challenging in distinguishing test article-related changes from normal developmental or senescent changes31. For the examination of live animals, daily vaginal smear observation is recommended because estrous cycle disruption is one of the most sensitive parameters for detecting ovarian/luteal toxicity and can be useful for determining the mode of toxicity1. Test article-related effects on CL are sometimes recognized as changes in size, color, or organ weight during necropsy. In histopathological examinations, since the ovary has a complicated structure, the bilateral ovary should be transversely dissected with a maximum cut surface to accurately detect luteal changes. Other female reproductive organs, including the uterus and vagina, must be carefully examined for identifying the estrous cycle, and a connection should be made with the ovarian/luteal changes. The mammary gland is an important tissue related to luteal toxicity. Since PRL plays critical roles in both the mammary gland and CL, if the luteal changes are accompanied by mammary gland changes, the relationship of PRL should be considered for determining its toxicity. The adrenal glands are also important tissues in luteal toxicity because CL and adrenal cortex are the main tissues involved in steroid hormone synthesis. If direct toxicity in the adrenal cortex is observed, CL should be carefully evaluated considering their effect on steroidogenesis and vice versa. Since angiogenesis is a critical process for luteinization, CL should be carefully evaluated if any changes resulting from anti-angiogenesis are suspected in various organs/tissues (e.g., epiphyseal growth plate thickening, adrenocortical necrosis/hemorrhage, and incisor tooth dental dysplasia)10, 32. When test article-related histopathological changes in CL are observed, it is important to determine whether the changes are caused by a direct effect or by other associated factors. For example, a decrease in the number of CL can be induced not only by an inhibitory effect of a test article on ovulation or luteal function but also by nonspecific stress following severe anorexia due to the toxicity of a test article12, 33, 34.

For the mode of toxicity analysis, measurement of serum/plasma hormone levels, gene/protein expression analysis, special staining, or immunohistochemical analysis can provide pivotal information on a case-by-case or step-by-step basis10, 35. Since CL is controlled by the upstream hypothalamic–pituitary system, it is often difficult to explain the mode of toxicity in vivo. In such cases, in vitro evaluation approaches using primary cell or tissue cultures, independent of the effects of associated organs or hormones, may be informative36, 37.

Representative luteal toxicological lesions in rats

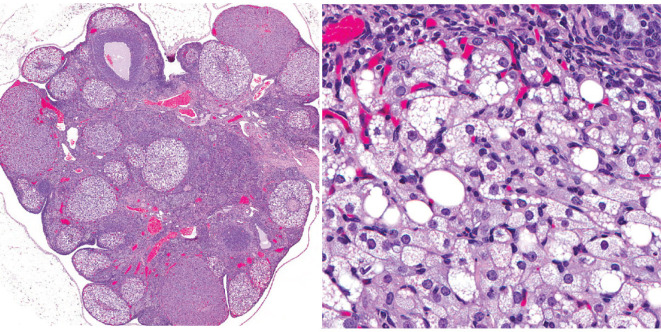

Hypertrophy, CL

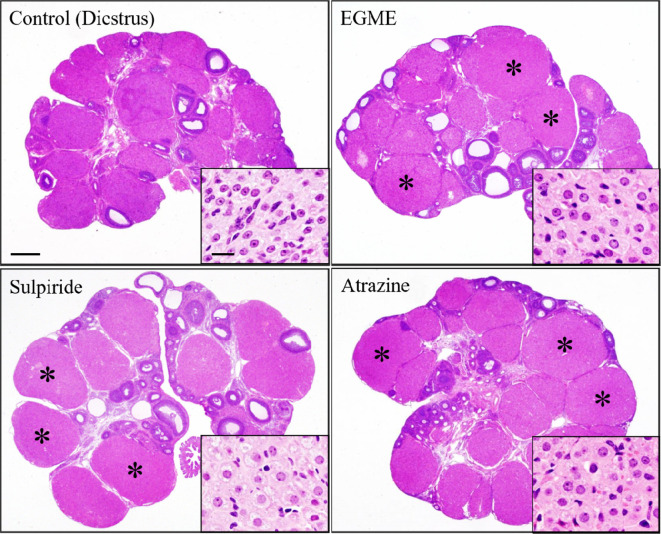

Hypertrophy of CL (Fig. 5) is histologically characterized by a large CL compared with that of the most recent diestrus stage and enlarged luteal cells with lightly abundant basophilic or eosinophilic cytoplasm. Hypertrophic luteal cells sometimes contain intracytoplasmic fine vacuoles.

Fig. 5.

Luteal cell hypertrophy induced by 2-week administration of ethylene glycol monomethyl ether (EGME), sulpiride, or atrazine. Luteal cells become hypertrophied with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm following EGME, sulpiride, or atrazine treatment compared to respective control CL at diestrus stage. Asterisks indicate hypertrophied CL. Bars represent 500 µm, and bars in the inset images represent 20 µm. Reproduced with permission from the Oxford University Press; taken from Taketa et al. Toxicol Sci. 121: 267–278. 2011.

There are two main causes of this change: 1) direct activation of steroidogenesis in luteal cells and 2) luteal cell activation with hyperprolactinemia. First, ethylene glycol monomethyl ether (EGME) and atrazine induce luteal hypertrophy following repeated administration35, 36, 38. EGME is used in various industrial products, such as detergents. EGME and its active metabolite, 2-methoxy acetic acid, induce hypersecretion of P4 from luteal cells both in vivo and in vitro35, 36, 37. Atrazine is a chlorotriazine herbicide, that is a potent endocrine disruptor that alters the central nervous system regulation of the reproductive system in mammals39. This change is histologically characterized by hypertrophy of both the new and old CL. The serum P4 level increased, accompanied by histopathological vaginal mucinous degeneration.

Second, D2 antagonists such as sulpiride, which is clinically used as an atypical antipsychotic drug, induce luteal cell hypertrophy35. In rats, D2 antagonists block the inhibitory effect of dopamine on PRL release, which results in the preservation of functional CL and produces a pseudopregnant state40. In this change, ovary weight may be increased. Not all CL are affected, but only new CL are activated and show hypertrophy with increased serum PRL levels. Since hyperprolactinemia is the cause of this change, lobuloalveolar hyperplasia in the mammary gland is also histologically observed. In the vagina, mucification was observed due to an increase in P4 levels.

Vacuolation, CL

Histopathologically, microvesicular or macrovesicular cytoplasmic vacuolation of luteal cells in CL, other than CL of the most recent ovulation at diestrus/proestrus has been observed. The affected luteal cells may become enlarged without clear degeneration or single-cell necrosis.

Vacuolation of luteal cells (Fig. 6) can occur due to the inhibition of steroid synthesis, which leads to lipid accumulation within the cells12. Vacuolation of CL accompanied by vacuolation of the adrenal glands has been described in anthracycline compounds41. Luteal cells can also be affected in cases of phospholipidosis, of which foamy cytoplasmic vacuolation can be indicative12. Since luteal cell vacuolation is typically observed as part of the degeneration seen at the proestrus stage, vacuolation of the luteal cells is thought to be diagnosed in the case of increased numbers of vacuolated CL or vacuolations observed in CL at stages other than the proestrus stage.

Fig. 6.

Representative images of vacuolation in luteal cells. The experimental detail is unknown. Reproduced with permission of the Japanese Society of Toxicologic Pathology from Dixson et al. Nonproliferative and proliferative lesions of the rat and mouse female reproductive system. J Toxicol Pathol. 27: 1S–107S. 2014.

Degeneration/Necrosis, CL

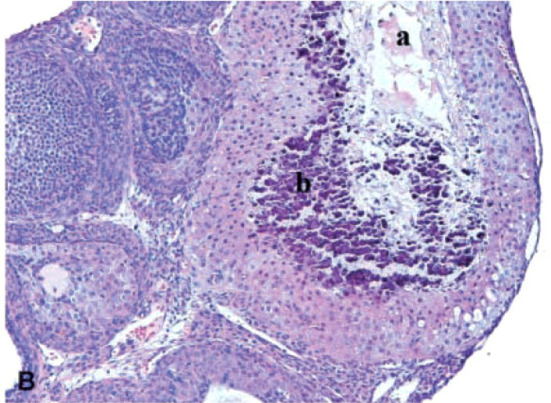

In this change, massive degeneration or coagulative central necrosis of the luteal cells was noted in CL (Fig. 7). Hyaline changes or mineralization may occasionally be seen32. Although apparent degeneration of the luteal cells is normally observed in CL of the most recent ovulation during proestrus in SD rats, treatment-related degeneration or necrosis of CL is observed in both new and old CL. It should be noted that WH rats normally show necrotic areas with or without foamy macrophage accumulation in old CL13. Therefore, it is sometimes difficult to distinguish whether the change is treatment-related in WH rats.

Fig. 7.

Degeneration/necrosis of CL in the ovaries of rats treated with sunitinib, a potent inhibitor of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), stem cell factor receptor (KIT), FMS-like tyrosine kinase-3 (FLT3), and rearranged during transfection (RET) receptors, at 6 mg/kg/day for up to 6 months (×200 magnification). Note necrosis (a) and mineralization (b). Reproduced with permission from the SAGE Publications; taken from Patyna et al. Toxicol Pathol. 36: 905–916. 2008.

VEGF receptor inhibitors induce this change10, 32. In the process of luteinization from the avascular Graafian follicle, dramatic vascularization (angiogenesis) is observed in new CL, and one of the principal growth factors driving this process is VEGF, whose cognate receptor is expressed on endothelial cells10. Therefore, the lesion is thought to be due to concomitant vessel regression and reduced vascular perfusion in CL.

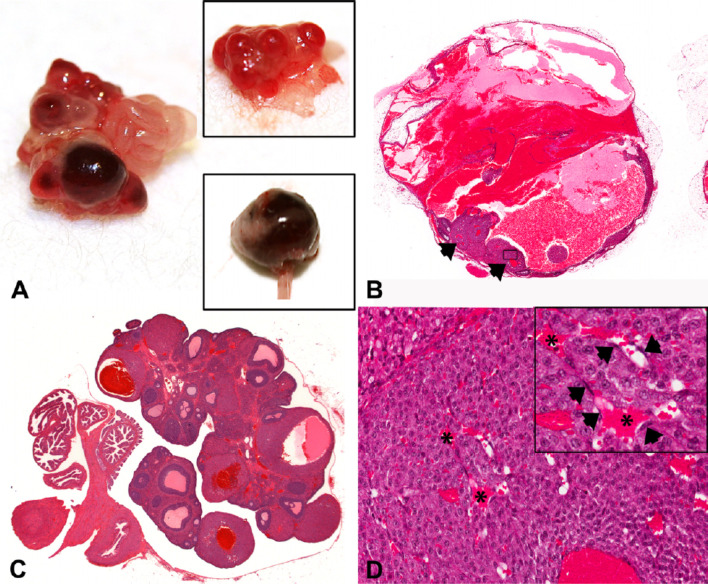

Hemorrhagic cystic degeneration, CL

The change is grossly observed as nodular enlargement of the ovary, characterized by abnormal multilocular areas of red discoloration10. Histologically, they show degeneration, compression, necrosis, and rupture of CL with loss of the ovarian cortex and hemorrhage into the interstitial space (Fig. 8)10. In less severely affected cases, the changes are characterized by single-cell necrosis of the luteal cells, which develop into cystic dilatation and enlargement with hemorrhaging into the central lumen. In the new CL, the earliest morphological change was the dilatation of fine walled capillaries or sinusoids10.

Fig. 8.

Images of hemorrhagic cystic degeneration of CL. (A) Gross photograph of an ovary from a nude rat treated with platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR) a and b inhibitors compared to a control ovary (upper inset). The ovary was enlarged, with abnormal nodular areas of red discoloration. The lower inset shows a severely enlarged ovary. (B and C) Sub-gross images from WH rats treated with PDGFR a and b inhibitors showing severe (B) and minimal (C) cystic hemorrhagic dilatation/degeneration of CL. In (B), the ovary was severely dilated with hemorrhage. Residual abnormal CL are present (arrowheads) with areas of hemorrhage in the central lumen. In (C), CL were abnormal, with dilated and hemorrhagic central cavities. (D) Higher power photomicrograph of Fig. 1B (boxed area: original magnification ×20) showing an abnormal CL with several dilated sinusoids (*). Note the absence of interstitial cells (pericytes/endothelium) (arrowheads) throughout CL. Reproduced with permission from the SAGE Publications; taken from Hall et al. Toxicol Pathol. 44: 98–111. 2016.

This change is induced by platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR) inhibitors10. In the significant angiogenesis during luteinization, PDGF and VEGF, whose cognate receptor is expressed on pericytes10, are critical factors. The lesion is likely due to increased vessel fragility resulting from endothelial proliferation and active pericyte recruitment and attachment, as these types of vessels are hyperpermeable10.

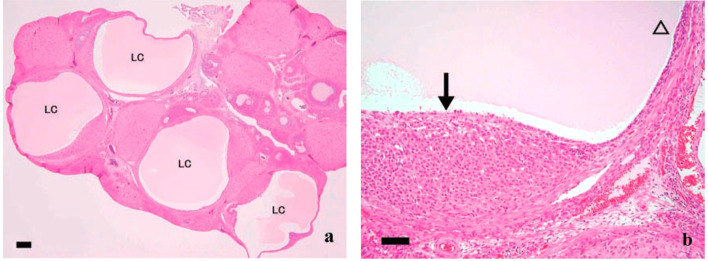

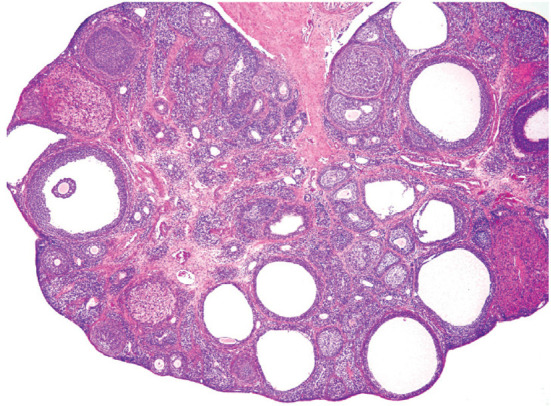

Cyst, luteal

A luteal cyst (Fig. 9) develops after the follicle has ovulated and fluid or blood accumulates within the follicle, causing it to expand and transform into a luteinized cyst12. The cyst is completely lined by several layers of polygonal luteal cells with abundant eosinophilic and finely vacuolated cytoplasm. An unovulated oocyte may occasionally be observed within the cavity. The cyst was generally larger than the normal CL.

Fig. 9.

Luteal cyst in rats treated with mifepristone, which is the synthetic steroid with antiprogesterone and antiglucocorticoid activities. (a) Multiple fluid-filled luteal cysts (LC) were observed. Bars show 200 µm. (b) Large cyst lined by thin (open arrowhead) and massive (arrows) luteinized cell layers. Bars show 50 µm. From Tamura et al. J Toxicol Sci. 34: SP31–42. 2009.

PR and COX-2 induced by the LH surge in cumulus cells affect the function and formation of the cumulus cell-enclosed oocyte complex in the ovulatory process8. PR or COX-2 inhibitors such as mifepristone and indomethacin induce luteal cysts in rats42, 43. These cysts are thought to be associated with anti-progesterone activity or COX-2 inhibition during the ovulatory process, resulting in incomplete luteinization.

Unovulated oocyte, CL

This lesion was characterized by old CL-containing oocyte in the central part of CL (Fig. 10). The unovulated oocyte in CL showed degeneration similar to that in atretic follicles. PR and COX-2 play critical roles in the ovulatory process, as mentioned above8. PR or COX-2 null mice show an unovulated CL phenotype8; therefore, PR antagonists and COX-2 inhibitors may induce these lesions. PPARα/γ agonists induce this change in rats44. Since PPARγ has important roles in PR regulation in the granulosa cells of the preovulatory follicles and controls ovulation9, the state of PPARγ activation is thought to induce the luteinization of the pseudo-ovulated follicle. Accompanied by this change, “follicle, luteinized”, “luteinized, nonovulatory follicle”, or “luteinized unruptured follicle” can also be observed with the same mechanism of action12.

Fig. 10.

Image of unovulated CL. CL-retained oocytes (arrows) were observed in the ovaries of rats treated with peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α/γ (PPARα/γ) dual agonist for 4 weeks. From Sato et al. J Toxicol Sci. 34: SP137–SP146. 2009.

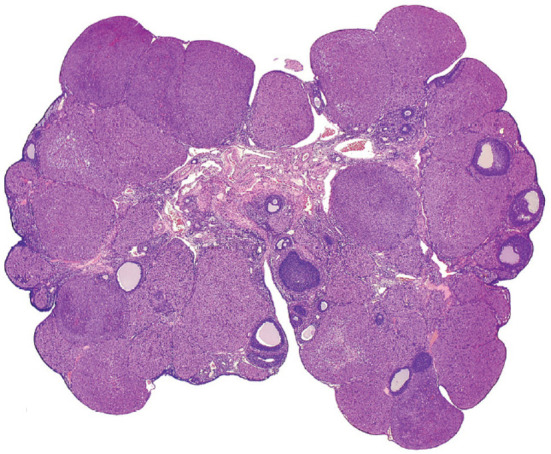

Increased number, CL

The histological feature of this change was an increased number of CL, but with normal size (Fig. 11). Additionally, the ovary weight may be increased. This is caused by decreased PRL release, resulting in inhibition of the preovulatory PRL surge, which is an important event in structural luteolysis, and decreased luteolysis is observed during late proestrus without estrous cycle disruption. Thus, the number of non-degenerating CL increased with each successive cycle, both new and old CL were observed, and the number of old CL increased.

Fig. 11.

Representative image of increased number of CL. The experimental detail is unknown. Reproduced with permission of the Japanese Society of Toxicologic Pathology from Dixson et al. Nonproliferative and proliferative lesions of the rat and mouse female reproductive system. J Toxicol Pathol. 27: 1S–107S. 2014.

D2 agonists, such as bromocriptine, inhibit PRL secretion, including the preovulatory PRL surge, and induce an increased number of CL in rats45. This can also result from superovulation caused by increased ovulation per cycle. PMSG or hCG induces superovulation and can lead to this change46.

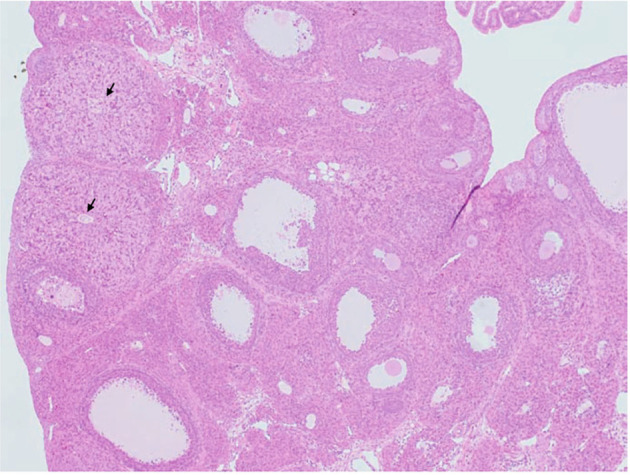

Decreased number/absent, CL

The diagnostic features of this lesion are a decreased number or a complete lack of new and/or old CL (Fig. 12). Concomitant changes in ovarian morphology vary depending on the cause of the disruption in ovulation and the duration without ovulation. A decreased number of old CL indicates a lack of normal estrous cycling over the past 3 to 4 weeks12. A lower number of new CL, but the presence of old CL, indicates that ovulation or estrous cycling has been interrupted within the past 1 to 3 cycles12.

Fig. 12.

Representative image of decreased number or absent CL. The experimental detail is unknown. Follicular cysts were also observed in the ovary. Reproduced with permission of the Japanese Society of Toxicologic Pathology from Dixson et al. Nonproliferative and proliferative lesions of the rat and mouse female reproductive systems. J Toxicol Pathol. 27: 1S–107S. 2014.

It should be noted that a decreased number of CL can be induced not only by an inhibitory effect of a test article on ovulation or luteal function, but also by nonspecific stress subsequent to severe anorexia due to the toxicity of a test article33, 34.

Accompanied by this change, a decrease in the number of large follicles and/or an increase in atretic follicles may be observed. These are common features when estrous cyclicity is disrupted, and this morphological lesion is observed in senescent ovaries. Therefore, “atrophy, ovary” or “age-related atrophy” are thought to be the appropriate diagnoses when the ovary shows a totally atrophic histology with decreases in the number of CL and large antral follicles and an increase in the number of atretic follicles.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no potential conflicts of interest with respect to this article.

Acknowledgments

I sincerely thank Dr. Midori Yoshida (Food Safety Commission, Cabinet Office of Japan) and Dr. Jyoji Yamate (Emeritus Professor, Veterinary Pathology, Osaka Prefecture University) for their helpful suggestions regarding my research in this article. I also thank Enago for English language review.

References

- 1.Sanbuissho A, Yoshida M, Hisada S, Sagami F, Kudo S, Kumazawa T, Ube M, Komatsu S, and Ohno Y. Collaborative work on evaluation of ovarian toxicity by repeated-dose and fertility studies in female rats. J Toxicol Sci. 34(Suppl 1): SP1–SP22. 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stouffer RL. Structure, function, and regulation of the corpus luteum. In: Knobil and Neill’s Physiology of Reproduction, 3rd ed. JD Neill (ed). Elsevier Academic Press, San Diego. 475–526. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rothchild I. The regulation of the mammalian corpus luteum. Recent Prog Horm Res. 37: 183–298. 1981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yoshida M, Sanbuissyo A, Hisada S, Takahashi M, Ohno Y, and Nishikawa A. Morphological characterization of the ovary under normal cycling in rats and its viewpoints of ovarian toxicity detection. J Toxicol Sci. 34(Suppl 1): SP189–SP197. 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaneko S, Sato N, Sato K, and Hashimoto I. Changes in plasma progesterone, estradiol, follicle-stimulating hormone and luteinizing hormone during diestrus and ovulation in rats with 5-day estrous cycles: effect of antibody against progesterone. Biol Reprod. 34: 488–494. 1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith MS, Freeman ME, and Neill JD. The control of progesterone secretion during the estrous cycle and early pseudopregnancy in the rat: prolactin, gonadotropin and steroid levels associated with rescue of the corpus luteum of pseudopregnancy. Endocrinology. 96: 219–226. 1975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Watanabe G, Taya K, and Sasamoto S. Dynamics of ovarian inhibin secretion during the oestrous cycle of the rat. J Endocrinol. 126: 151–157. 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Espey LL, and Richards JS. Ovulation. In: Knobil and Neill’s Physiology of Reproduction, 3rd ed. JD Neill (ed). Elsevier Academic Press, San Diego. 475–526. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim J, Sato M, Li Q, Lydon JP, Demayo FJ, Bagchi IC, and Bagchi MK. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma is a target of progesterone regulation in the preovulatory follicles and controls ovulation in mice. Mol Cell Biol. 28: 1770–1782. 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hall AP, Ashton S, Horner J, Wilson Z, Reens J, Richmond GHP, Barry ST, and Wedge SR. PDGFR inhibition results in pericyte depletion and hemorrhage into the corpus luteum of the rat ovary. Toxicol Pathol. 44: 98–111. 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bowen JM, and Keyes PL. Repeated exposure to prolactin is required to induce luteal regression in the hypophysectomized rat. Biol Reprod. 63: 1179–1184. 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dixon D, Alison R, Bach U, Colman K, Foley GL, Harleman JH, Haworth R, Herbert R, Heuser A, Long G, Mirsky M, Regan K, Van Esch E, Westwood FR, Vidal J, and Yoshida M. Nonproliferative and proliferative lesions of the rat and mouse female reproductive system. J Toxicol Pathol. 27(Suppl): 1S–107S. 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sato J, Hashimoto S, Doi T, Yamada N, and Tsuchitani M. Histological characteristics of the regression of corpora lutea in wistar hannover rats: the comparisons with sprague-dawley rats. J Toxicol Pathol. 27: 107–113. 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Taketa Y, Inomata A, Hosokawa S, Sonoda J, Hayakawa K, Nakano K, Momozawa Y, Yamate J, Yoshida M, Aoki T, and Tsukidate K. Histopathological characteristics of luteal hypertrophy induced by ethylene glycol monomethyl ether with a comparison to normal luteal morphology in rats. Toxicol Pathol. 39: 372–380. 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tébar M, Ruiz A, Gaytán F, and Sánchez-Criado JE. Follicular and luteal progesterone play different roles synchronizing pituitary and ovarian events in the 4-day cyclic rat. Biol Reprod. 53: 1183–1189. 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bruot BC, Wiest WG, and Collins DC. Effect of low density and high density lipoproteins on progesterone secretion by dispersed corpora luteal cells from rats treated with aminopyrazolo-(3,4-d)pyrimidine. Endocrinology. 110: 1572–1578. 1982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schuler LA, Langenberg KK, Gwynne JT, and Strauss JF, 3rd . High density lipoprotein utilization by dispersed rat luteal cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 664: 583–601. 1981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Acton S, Rigotti A, Landschulz KT, Xu S, Hobbs HH, and Krieger M. Identification of scavenger receptor SR-BI as a high density lipoprotein receptor. Science. 271: 518–520. 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stocco DM. StAR protein and the regulation of steroid hormone biosynthesis. Annu Rev Physiol. 63: 193–213. 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oonk RB, Krasnow JS, Beattie WG, and Richards JS. Cyclic AMP-dependent and -independent regulation of cholesterol side chain cleavage cytochrome P-450 (P-450scc) in rat ovarian granulosa cells and corpora lutea. cDNA and deduced amino acid sequence of rat P-450scc. J Biol Chem. 264: 21934–21942. 1989. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peng L, Arensburg J, Orly J, and Payne AH. The murine 3beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (3beta-HSD) gene family: a postulated role for 3beta-HSD VI during early pregnancy. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 187: 213–221. 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stocco CO, Zhong L, Sugimoto Y, Ichikawa A, Lau LF, and Gibori G. Prostaglandin F2alpha-induced expression of 20alpha-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase involves the transcription factor NUR77. J Biol Chem. 275: 37202–37211. 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Taketa Y, Yoshida M, Inoue K, Takahashi M, Sakamoto Y, Watanabe G, Taya K, Yamate J, and Nishikawa A. The newly formed corpora lutea of normal cycling rats exhibit drastic changes in steroidogenic and luteolytic gene expressions. Exp Toxicol Pathol. 64: 775–782. 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stocco C, Telleria C, and Gibori G. The molecular control of corpus luteum formation, function, and regression. Endocr Rev. 28: 117–149. 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pharriss BB, and Wyngarden LJ. The effect of prostaglandin F 2alpha on the progestogen content of ovaries from pseudopregnant rats. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 130: 92–94. 1969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Plas-Roser S, Muller B, and Aron C. Estradiol involvement in the luteolytic action of LH during the estrous cycle in the rat. Exp Clin Endocrinol. 92: 145–153. 1988. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stocco C, Callegari E, and Gibori G. Opposite effect of prolactin and prostaglandin F(2 alpha) on the expression of luteal genes as revealed by rat cDNA expression array. Endocrinology. 142: 4158–4161. 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gaytán F, Morales C, Bellido C, Aguilar R, Millán Y, Martín De Las Mulas J, and Sánchez-Criado JE. Progesterone on an oestrogen background enhances prolactin-induced apoptosis in regressing corpora lutea in the cyclic rat: possible involvement of luteal endothelial cell progesterone receptors. J Endocrinol. 165: 715–724. 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roughton SA, Lareu RR, Bittles AH, and Dharmarajan AM. Fas and Fas ligand messenger ribonucleic acid and protein expression in the rat corpus luteum during apoptosis-mediated luteolysis. Biol Reprod. 60: 797–804. 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yadav VK, Lakshmi G, and Medhamurthy R. Prostaglandin F2alpha-mediated activation of apoptotic signaling cascades in the corpus luteum during apoptosis: involvement of caspase-activated DNase. J Biol Chem. 280: 10357–10367. 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vidal JD. The impact of age on the female reproductive system: a pathologist’s perspective. Toxicol Pathol. 45: 206–215. 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Patyna S, Arrigoni C, Terron A, Kim TW, Heward JK, Vonderfecht SL, Denlinger R, Turnquist SE, and Evering W. Nonclinical safety evaluation of sunitinib: a potent inhibitor of VEGF, PDGF, KIT, FLT3, and RET receptors. Toxicol Pathol. 36: 905–916. 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chapin RE, Gulati DK, Barnes LH, and Teague JL. The effects of feed restriction on reproductive function in Sprague-Dawley rats. Fundam Appl Toxicol. 20: 23–29. 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hayashi S, Taketa Y, Inoue K, Takahashi M, Matsuo S, Irie K, Watanabe G, and Yoshida M. Effects of pyperonyl butoxide on the female reproductive tract in rats. J Toxicol Sci. 38: 891–902. 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Taketa Y, Yoshida M, Inoue K, Takahashi M, Sakamoto Y, Watanabe G, Taya K, Yamate J, and Nishikawa A. Differential stimulation pathways of progesterone secretion from newly formed corpora lutea in rats treated with ethylene glycol monomethyl ether, sulpiride, or atrazine. Toxicol Sci. 121: 267–278. 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Davis BJ, Almekinder JL, Flagler N, Travlos G, Wilson R, and Maronpot RR. Ovarian luteal cell toxicity of ethylene glycol monomethyl ether and methoxy acetic acid in vivo and in vitro. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 142: 328–337. 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Almekinder JL, Lennard DE, Walmer DK, and Davis BJ. Toxicity of methoxyacetic acid in cultured human luteal cells. Fundam Appl Toxicol. 38: 191–194. 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Taketa Y, Inoue K, Takahashi M, Yamate J, and Yoshida M. Differential morphological effects in rat corpora lutea among ethylene glycol monomethyl ether, atrazine, and bromocriptine. Toxicol Pathol. 41: 736–743. 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cooper RL, Laws SC, Das PC, Narotsky MG, Goldman JM, Lee Tyrey E, and Stoker TE. Atrazine and reproductive function: mode and mechanism of action studies. Birth Defects Res B Dev Reprod Toxicol. 80: 98–112. 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rehm S, Stanislaus DJ, and Wier PJ. Identification of drug-induced hyper- or hypoprolactinemia in the female rat based on general and reproductive toxicity study parameters. Birth Defects Res B Dev Reprod Toxicol. 80: 253–257. 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Comereski CR, Peden WM, Davidson TJ, Warner GL, Hirth RS, and Frantz JD. BR96-doxorubicin conjugate (BMS-182248) versus doxorubicin: a comparative toxicity assessment in rats. Toxicol Pathol. 22: 473–488. 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tamura T, Yokoi R, Okuhara Y, Harada C, Terashima Y, Hayashi M, Nagasawa T, Onozato T, Kobayashi K, Kuroda J, and Kusama H. Collaborative work on evaluation of ovarian toxicity. 2) Two- or four-week repeated dose studies and fertility study of mifepristone in female rats. J Toxicol Sci. 34(Suppl 1): SP31–SP42. 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tsubota K, Kushima K, Yamauchi K, Matsuo S, Saegusa T, Ito S, Fujiwara M, Matsumoto M, Nakatsuji S, Seki J, and Oishi Y. Collaborative work on evaluation of ovarian toxicity. 12) Effects of 2- or 4-week repeated dose studies and fertility study of indomethacin in female rats. J Toxicol Sci. 34(Suppl 1): SP129–SP136. 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sato N, Uchida K, Nakajima M, Watanabe A, and Kohira T. Collaborative work on evaluation of ovarian toxicity. 13) Two- or four-week repeated dose studies and fertility study of PPAR alpha/gamma dual agonist in female rats. J Toxicol Sci. 34(Suppl 1): SP137–SP146. 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kumazawa T, Nakajima A, Ishiguro T, Jiuxin Z, Tanaharu T, Nishitani H, Inoue Y, Harada S, Hayasaka I, and Tagawa Y. Collaborative work on evaluation of ovarian toxicity. 15) Two- or four-week repeated-dose studies and fertility study of bromocriptine in female rats. J Toxicol Sci. 34(Suppl 1): SP157–SP165. 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Löseke A, and Spanel-Borowski K. Simple or repeated induction of superovulation: a study on ovulation rates and microvessel corrosion casts in ovaries of golden hamsters. Ann Anat. 178: 5–14. 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]