Abstract

Objective:

To assess the odds of a psychiatric or neurodevelopmental diagnosis among youth with a diagnosis of gender dysphoria compared to matched controls in a large electronic health record dataset from six pediatric health systems, PEDSnet. We hypothesized that youth with gender dysphoria would have higher odds of having psychiatric and neurodevelopmental diagnoses than controls.

Study design:

All youth with a diagnosis of gender dysphoria (n=4,173 age at last visit 16.2 ± 3.4) and at least one outpatient encounter were extracted from the PEDSnet database and propensity-score matched on 8 variables to controls without gender dysphoria (n=16,648, age at last visit 16.2 ± 4.8) using multivariable logistic regression. The odds of having psychiatric and neurodevelopmental diagnoses were examined using generalized estimating equations.

Results:

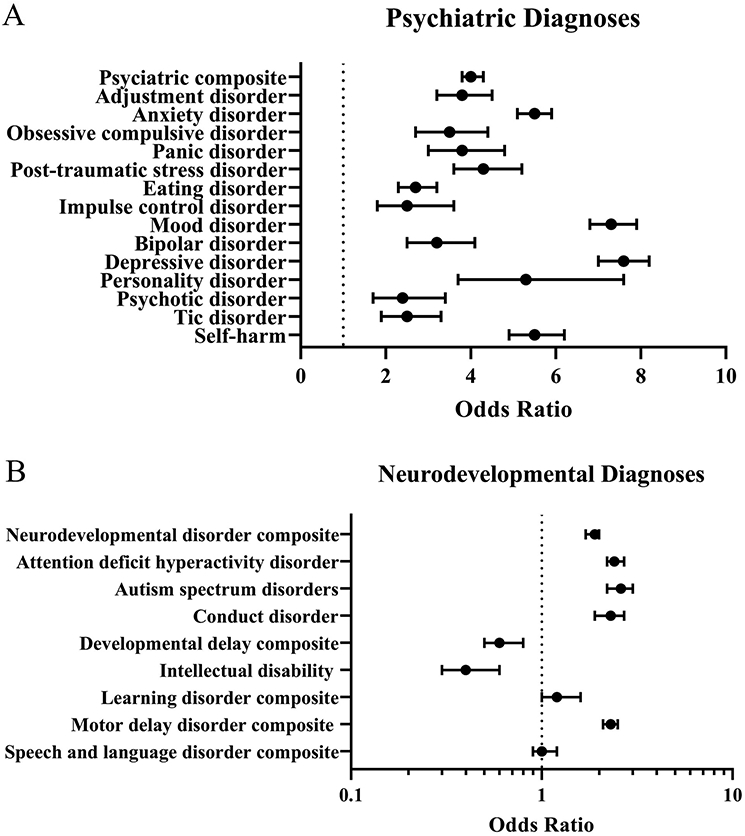

Youth with gender dysphoria had higher odds of psychiatric (OR: 4.0 [95% CI: 3.8, 4.3] p<0.0001) and neurodevelopmental diagnoses (1.9 [1.7, 2.0], p<0.0001). Youth with gender dysphoria were more likely to have a diagnosis across all psychiatric disorder sub-categories, with particularly high odds of mood disorder (7.3 [6.8, 7.9], p<0.0001) and anxiety (5.5 [5.1, 5.9], p<0.0001). Youth with gender dysphoria had a greater odds of autism spectrum disorder (2.6, [2.2, 3.0], p<0.0001).

Conclusions:

Youth with gender dysphoria at large pediatric health systems have greater odds of psychiatric and several neurodevelopmental diagnoses compared to youth without gender dysphoria. Further studies are needed to evaluate changes in mental health over time with access to gender affirming care.

Keywords: gender dysphoria, transgender, psychiatric, neurodevelopment, depression, anxiety, ADHD, autism, mood disorder, eating disorder

There is a growing population of transgender and gender diverse (TGD) youth in the United States (U.S.).1 Up to 1.8% of youth identify as transgender.2, 3 Gender diverse describes individuals with a variety of gender identities across the gender spectrum, including those who identify as transgender. Gender dysphoria, which describes the distress associated with a conflict between gender identity and anatomy or sex, is a listed diagnosis in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 5th edition (DSM-5).4 With an increase in TGD youth who seek affirming care to align their bodies with their gender identities,1 healthcare providers must be aware of behavioral health disparities within this population. Medical care that respects the gender identity of the patient is recommended by many organizations, including the American Academy of Pediatrics,5 Endocrine Society,6 and American Psychological Association.7

Studies evaluating behavioral health outcomes among TGD youth have most frequently demonstrated disproportionate experiences of anxiety,8-10 depression,9-12 suicidality,3, 8-10, 13 self-harm,8-11 and substance use problems.3 Large surveys in the US have shown that 40% of adults14 and 35% of youth3 have attempted suicide, a rate six to nine times the general population. Studies have also shown an increased prevalence of autism spectrum disorder (ASD)12, 15, 16 and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) among TGD youth.16 There is limited research on other behavioral health diagnoses such as obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD),12 post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), personality disorders, bipolar disorder,12 tic disorder, and psychotic disorders12 among TGD youth.

We aimed to evaluate the odds of a psychiatric or neurodevelopmental diagnosis or specific psychiatric or neurodevelopmental diagnoses among TGD youth with a diagnosis of gender dysphoria compared to matched controls using propensity score matching in the PEDSnet database. Propensity score matching can reduce the bias in estimation of treatment effects in observational studies when treatment assignment is related to patient characteristics.17 The advantage of matching on propensity score rather than individual covariates is that matching can occur on a larger number of covariates without sacrificing degrees of freedom.18 We hypothesized that youth with gender dysphoria would have higher odds of behavioral health diagnoses than matched controls.

Methods

Data for this analysis were obtained from PEDSnet (https://pedsnet.org/), a pediatric Learning Health System and a clinical research network in PCORnet, the National Patient Centered Clinical Research Network, an initiative funded by the Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI), with a Common Data Model. Six pediatric health systems participated in this PEDSnet dataset, collectively including over 6 million children: Children’s Hospital Colorado, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Nemours Children’s Health System, Nationwide Children’s Hospital, St. Louis Children’s Hospital, and Seattle Children’s Hospital. Clinical data are available from the electronic health record (EHR) of these health systems from 2009 onward for patients with an in-person encounter with a provider. All youth (age range 3.4-28.5 years at last visit) with a diagnosis of gender dysphoria (by PEDSnet concept ID, Online Table 3 includes codes extracted from the EHR problem list or diagnosis code from any encounter) and at least one outpatient visit from 2009-2019 were extracted from the PEDSnet database in November 2019. Gender dysphoria is a diagnosis in the DSM-5 which was released in 2013,4 and Gender Identity Disorder was the prior related diagnosis in the 4th edition of the DSM.19 In hospital systems, other diagnosis codes are often used based on the International Classification of Diseases or ICD system. Cases with a diagnosis of gender dysphoria were selected based on one of 32 PEDSnet Concept IDs (Online Table 3). A random sample of 197,042 patients with at least one outpatient visit in the same time period who did not have a diagnosis of gender dysphoria were used as a pool of controls. To ensure these controls were representative of the general PEDSnet population, we evaluated the prevalence of well characterized pediatric diagnoses (asthma, type 1 diabetes, and acute lymphoid leukemia) to ensure the prevalence in the controls was similar to PEDSnet as a whole. We chose one outpatient visit as a criterion for cases and controls to not oversample from those who were only seen in the health systems for urgent/emergent care.

Outcomes

Composite diagnoses were created for psychiatric diagnoses and neurodevelopmental diagnoses based on SNOMED clinical terms concept terminology (medical term codes, Online Table 4). These served as the two primary outcomes for the study with sub-diagnoses serving as secondary outcomes. SNOMED codes are used in U.S. Federal Government systems for exchange of electronic clinical health information (www.snomed.org). PEDSnet concept IDs were mapped to Athena Ancestor Tables (developed by Observational Health Data Sciences and Informatics, Columbia University). Athena is the application that contains standardized vocabularies used in PEDSnet. Gender dysphoria falls under the ancestor code of “mental disorder” within the SNOMED system; therefore, the diagnosis of gender dysphoria was specifically excluded from the psychiatric diagnoses composite. Within the neurodevelopmental disorder diagnoses composite, additional composites were made for motor delay, developmental delay, speech and language disorders, and learning disorders. Similarly, a self-harm composite comprised of all codes reflective of self-injurious behavior and suicidality was made. If n was <10 in any cell, that cell was omitted.

Statistical analysis

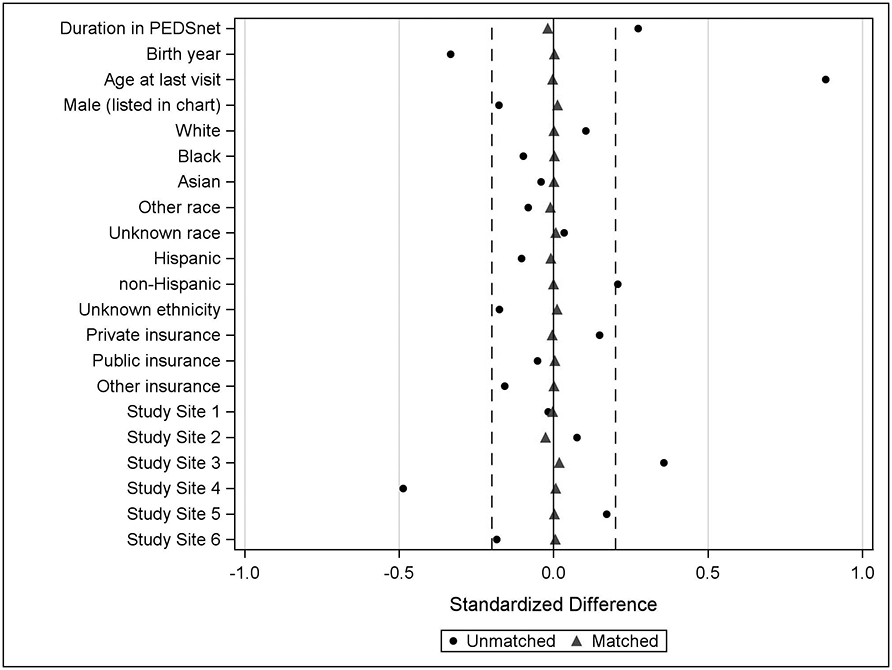

Propensity scores were generated for cases (individuals with a gender dysphoria) via multivariable logistic regression and used to match every 1 case to 4 controls.20 Forty-four cases were a 1:3 match as there was not an available fourth match. The propensity score was defined as the probability of having gender dysphoria given the following characteristics: sex listed in the chart (based on other analyses not shown here, this represents sex assigned at birth in most cases), year of birth, age at last medical visit, PEDSnet site, race, ethnicity, payer status (public/private/none), and duration in the PEDSnet database (time between first and last encounter). Individuals with an unknown sex were omitted (3 cases, 6 controls) as this caused model instability. Cases and controls were matched on the predicted probability of having the diagnosis (gender dysphoria) using a greedy match algorithm and a caliper of width 0.1.21 The balance of covariates between the cases and control groups (i.e., the similarity of the covariate distributions) was evaluated as a reduction in standardized mean difference, using a decision criterion of < 0.20 to indicate that a covariate was balanced (Figure 1).22 Variable missingness was handled by the widely accepted approach of including missing as another category for the variable.23

Figure 1: Standardized differences in population baseline characteristics in youth with gender dysphoria vs. controls before and after matching.

Dotted lines are at 0.2.

Differences in outcomes of interest between cases and controls were examined using generalized estimating equations, which accounted for potential correlation between the cases and matched controls.24 Sex listed in the chart was included as interaction term in the regression model to evaluate whether the associations between diagnoses and case/control status differed by sex (a p-value cutoff of <0.05 was used for interaction terms). Descriptive statistics including the prevalence of outcomes in the cases versus control groups, as well as odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were computed. A conservative p-value of <0.0025 was considered significant given the multiple comparisons for secondary outcomes. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

Demographics of youth with gender dysphoria (n=4,173) and matched controls without gender dysphoria (n=16,668) are in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographics of individuals with gender dysphoria and matched controls

| Gender Dysphoria n=4,173 |

Controls n=16,648 |

|

|---|---|---|

| Sex listed in chart | ||

| Female | 2,766 (66.3) | 11,130 (66.9) |

| Male | 1,407 (33.7) | 5,518 (33.1) |

| Race | ||

| White | 3,027 (72.5) | 12,065 (72.5) |

| Black | 257 (6.2) | 1,016 (6.1) |

| Asian | 98 (2.3) | 387 (2.3) |

| Other | 390 (9.3) | 1,610 (9.7) |

| Unknown | 401 (9.6) | 1,570 (9.4) |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Non-Hispanic | 3,538 (84.8) | 14,121 (84.8) |

| Hispanic | 354 (8.5) | 1,452 (8.7) |

| Unknown | 281 (6.7) | 1,075 (6.5) |

| Insurance type | ||

| Private | 2,530 (60.6) | 10,127 (60.8) |

| Public | 1,287 (30.8) | 5,105 (30.7) |

| Other | 253 (6.1) | 898 (5.4) |

| Unknown | 103 (2.5) | 518 (3.1) |

| Age at first visit (years) | 9.4 ± 5.8 | 9.4 ± 6.0 |

| Age at last visit (years) | 16.2 ± 3.4 | 16.2 ± 4.8 |

| Duration in PEDSnet (years) | 6.7 ± 5.4 | 6.8 ± 5.6 |

| Visit with a behavioral health or neurodevelopmental provider | 2,776 (66.5) | 4,759 (28.6) |

| Age at first GD diagnosis (years) | 15.0 (13.0, 16.0) | --- |

| Age at last GD diagnosis (years) | 16.0 (14.0, 17.0) | --- |

Data are shown as n (%), mean ± standard deviation or median (25th, 75th%ile). Age at first visit refers to the age at the first visit in PEDSnet (not necessarily a visit related to GD). Age at first or last diagnosis refers to a diagnosis of gender dysphoria (GD) in the chart.

Overall, 2,557 (61.3%) of youth with a diagnosis of gender dysphoria and 4,701 (28.2%) of matched controls had a psychiatric diagnosis in their EHR. Youth with a diagnosis of gender dysphoria had higher odds of a psychiatric diagnosis overall (OR: 4.0 [95% CI: 3.8, 4.3], p<0.0001) and higher odds of all specific psychiatric diagnoses with OR ranging from 2.4 to 7.6 (Table 2, Figure 2a) compared to controls. Youth with gender dysphoria also had higher odds of self-harm (p<0.0001, Table 2).

Table 2.

Prevalence and odds ratios of behavioral health diagnoses in those with gender dysphoria vs. controls

| Gender dysphoria n=4,173 (%) |

Controls n=16,648 (%) |

OR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Psychiatric Diagnoses | 2,557 (61.3) | 4,701 (28.2) | 4.0 (3.8, 4.3) * |

| Adjustment disorder | 286 (6.9) | 315 (1.9) | 3.8 (3.2, 4.5)* |

| Anxiety disorder | 1,767 (42.3) | 1,976 (11.9) | 5.5 (5.1, 5.9)* |

| Obsessive compulsive disorder | 139 (3.3) | 164 (1.0) | 3.5 (2.7, 4.4)* |

| Panic disorder | 141 (3.4) | 151 (0.9) | 3.8 (3.0, 4.8)* |

| Post-traumatic stress disorder | 233 (5.6) | 226 (1.4) | 4.3 (3.6, 5.2)* |

| Eating disorder | 246 (5.9) | 381 (2.3) | 2.7 (2.3, 3.2)* |

| Impulse control disorder | 51 (1.2) | 81 (0.5) | 2.5 (1.8, 3.6)* |

| Mood disorder | 1,956 (46.9) | 1,797 (10.8) | 7.3 (6.8, 7.9)* |

| Bipolar disorder | 126 (3.0) | 160 (1.0) | 3.2 (2.5, 4.1)* |

| Depressive disorder | 1,846 (44.2) | 1,577 (9.5) | 7.6 (7.0, 8.2)* |

| Personality disorder | 70 (1.7) | 53 (0.3) | 5.3 (3.7, 7.6)* |

| Psychotic disorder | 54 (1.3) | 90 (0.5) | 2.4 (1.7, 3.4)* |

| Tic disorder | 95 (2.3) | 153 (0.9) | 2.5 (1.9, 3.3)* |

| Self-Harm | 690 (16.5) | 579 (3.5) | 5.5 (4.9, 6.2)* |

| Neurodevelopmental Diagnoses | 1,075 (25.8) | 2,595 (15.6) | 1.9 (1.7, 2.0) * |

| Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder | 749 (17.9) | 1,377 (8.3) | 2.4 (2.2, 2.7)* |

| Autism spectrum disorder | 249 (6.0) | 404 (2.4) | 2.6 (2.2, 3.0)* |

| Conduct disorder | 222 (5.3) | 398 (2.4) | 2.3 (1.9, 2.7)* |

| Developmental delay | 74 (1.8) | 493 (3.0) | 0.6 (0.5, 0.8)* |

| Intellectual disability | 26 (0.6) | 276 (1.7) | 0.4 (0.3, 0.6)* |

| Learning disorder | 93 (2.2) | 301 (1.8) | 1.2 (1.0, 1.6) |

| Motor delay | 769 (18.4) | 1,516 (9.1) | 2.3 (2.1, 2.5)* |

| Speech/language disorder composite | 214 (5.1) | 822 (4.9) | 1.0 (0.9, 1.2) |

Data are shown as n (%); the odds ratios; 95% confidence intervals are in the final column

p<0.0001. Indented diagnoses are subgroups of those above.

Figure 2: Odds of psychiatric or neurodevelopmental diagnoses among youth with gender dysphoria compared to matched controls.

The forest plots show the odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals of psychiatric disorders (A) and neurodevelopmental disorders (B) among youth with gender dysphoria compared to controls. Higher odds ratios (>1) indicate that youth with gender dysphoria are more likely to have the listed diagnosis. Lower odds ratios (<1) indicate that youth with gender dysphoria are less likely to have the listed diagnosis. Obsessive compulsive disorder, panic disorder and post-traumatic disorder are sub-categories of anxiety disorder. Depressive disorder and bipolar disorder are sub-categories of mood disorder.

A total of 1,075 (25.8%) of the youth diagnosed with gender dysphoria and 2,595 (15.6%) of the matched controls had a neurodevelopmental disorder diagnosis (Table 2, Figure 2b). Youth diagnosed with gender dysphoria had higher odds of a neurodevelopmental disorder (1.9 [95% CI: 1.7, 2.0], p<0.0001) compared to controls. Individuals with gender dysphoria had higher odds of ADHD (2.4 [95% CI: 2.2, 2.7], p<0.0001) and ASD (2.6 [95% CI: 2.2, 3.0], p<0.0001) than controls. However, youth with gender dysphoria had lower odds of developmental delay and intellectual disability diagnoses, and no differences in the odds of learning and speech disorders.

When sex listed in the chart was included as an interaction term, there were no differences in the directionality of the odds of psychiatric or neurodevelopmental diagnoses. However, there were several significant interactions by sex listed in the chart for a psychiatric diagnosis (p<0.0001), neurodevelopmental disorder (p=0.01), ADHD (p<0.0001), eating disorder (p<0.0001), and motor delay (p<0.0001). Individuals with gender dysphoria and male sex listed in the chart had higher odds of a psychiatric diagnosis than males without gender dysphoria (2.8 [95% CI: 2.5, 3.2], p<0.0001); individuals with gender dysphoria and female sex listed in the chart also had higher odds of a psychiatric diagnosis than females without gender dysphoria (4.9 [95% CI: 4.5, 5.3], p<0.0001). Individuals with gender dysphoria and male sex listed in the chart had higher odds of a neurodevelopmental diagnosis than males without gender dysphoria (1.7 [95% CI: 1.5, 1.9], p<0.0001); individuals with gender dysphoria and female sex listed in the chart also had higher odds of a neurodevelopmental diagnosis than females without gender dysphoria (2.1 [95% CI: 1.9, 2.3], p<0.0001). Individuals with gender dysphoria and male sex listed in the chart had higher odds of eating disorder than males without gender dysphoria (4.6 [95% CI: 3.2, 6.5], p<0.0001); individuals with gender dysphoria and female sex listed in the chart also had higher odds of eating disorder than females without gender dysphoria (2.3 [95% CI: 1.9, 2.8], p<0.0001). Individuals with gender dysphoria and male sex listed in the chart had higher odds of motor delay than males without gender dysphoria (1.8 [95% CI: 1.6, 2.1], p<0.0001); individuals with gender dysphoria and female sex listed in the chart also had higher odds of motor delay than females without gender dysphoria (2.7 [95% CI: 2.4, 3.0], p<0.0001).

Discussion

We show that youth in PEDSnet with a documented diagnosis of gender dysphoria have higher odds of having behavioral health diagnoses than rigorously matched controls.

Many of the largest datasets evaluating behavioral health outcomes focus on adults and have utilized a survey design.14 The 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey found that 39% of adults experienced serious psychological distress in the month prior to the survey and 40% had attempted suicide in their lifetime, outcomes associated with stigma and discrimination.14 Secondary analyses of the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, a national U.S. survey, show that transgender adults did not have higher odds of reporting poor mental health in the prior month. However, those who identified as gender non-conforming reported worse physical and mental health than cisgender25 or binary transgender adults.26 The Youth Risk Behavior Survey found that 35% of transgender youth had attempted suicide in the last year and also found a high prevalence of violence, victimization, and substance use.3 In comparison with the above studies, the PEDSnet cohort had a lower prevalence of self-harm compared to these surveys; 16% of PEDSnet youth with gender dysphoria had diagnoses in their medical record for self-injurious behavior, suicidal thoughts or attempts. The lower prevalence of self-harm or suicidal ideation may be secondary to omission of these diagnoses from their EHR or they may be more likely than TGD youth in the general population to have access to gender affirming care and resources.

There was a high prevalence of behavioral health diagnoses in this cohort, with 61% of those with gender dysphoria having at least one psychiatric diagnosis, the highest being a mood or anxiety disorder. Berecra-Culqui and colleagues investigated the mental health of >1,000 TGD individuals (745 transmasculine, 588 transfeminine) in the Kaiser Permanente STRONG Cohort (California and Georgia), compared to cisgender controls utilizing documented diagnostic codes from EHR data.8 They found that TGD children and adolescents (age 3-17) had a high prevalence of psychiatric and neurodevelopmental conditions and a higher risk of these conditions than control youth.8 Our findings support previous studies suggesting TGD youth disproportionately experience depression, anxiety, suicidality, and self-harm when compared to cisgender individuals. This study also shows an increased prevalence of obsessive-compulsive disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, disordered eating, personality disorders, bipolar disorder, tic disorder, and psychotic disorders.9, 12, 27, 28

Poor behavioral health outcomes should be conceptualized largely as the result of complex and layered socio-cultural and political factors that impact TGD youth.7, 29 Risk factors that are likely to impact overall mental health for TGD individuals include minority stress (e.g., victimization, discrimination),3, 30 gender dysphoria and appearance congruence,31 feelings of isolation, inadequate family support,32 emotional/social isolation,33 lack of autonomy over decision making,33 barriers to accessing gender affirming care,33-35 employment discrimination,33 and limited financial resources.33 In the Youth Risk Behavior Survey, TGD youth were two to six times more likely to be victimized, including experiencing sexual dating violence, experiencing physical dating violence, being bullied at school, being electronically bullied, feeling unsafe during travel to or from school, and being forced to have sexual intercourse.3 However, protective factors such as social support,28, 36 parental support/affirmation of gender identity,37, 38 higher self-esteem,36 resiliency,36, 39 and access to affirming care34, 40, 41 have been associated with higher levels of wellbeing and lower mental health distress. Access to gender-affirming interventions, including hormone therapy and surgery, has been shown to improve gender dysphoria, psychological symptoms and quality of life in small samples.28 A meta-analysis of 28 studies showed that hormonal interventions likely improve gender dysphoria, psychological functioning and quality of life, but due to understandable ethical concerns, most of these studies have lacked controls.28 Another study showed that those who are older at presentation have worse mental health than those who presented to care at a younger age.42 Studies have addressed the role that complex factors such as minority stress and resilience play in determining health outcomes.39 As gender care centers across the country experience an increase in the number of youth seeking gender-affirming care to align their bodies with their gender identities,1 research efforts should continue to explore the impact of this care on TGD youth’s mental health.

We provide evidence for higher rates of various neurodevelopmental diagnoses among youth with gender dysphoria.8, 43-47 A meta-analysis found that the prevalence of ASD among those with gender dysphoria ranged from 6% to 68% depending on the methodology of the study.16 The prevalence within PEDSnet is at the lower end of this range, but still represents more than twice the odds of ASD in controls. Other studies that utilized chart review had a similar prevalence to the findings in this study,48 whereas others that assessed social short-comings on the Social Responsiveness Scale had higher prevalence rates.43, 49 Warrier and colleagues used five cross-sectional datasets with matched controls to investigate relative rates of ASD, and found that TGD individuals were 3.0 to 6.4 times more likely to be diagnosed with ASD than their cisgender counterparts.12 In this PEDSnet sample, youth with gender dysphoria were 2.6 times more likely to have a diagnosis of ASD than their matched cisgender counterparts, which was similar to the risk in the Kaiser STRONG cohort for children.8 In the STRONG cohort, there were differences by sex assigned at birth in ASD prevalence in the adolescents,8 a difference we did not find (odds were similar based on sex in the chart). The exact link between gender dysphoria and ASD is not known, but factors contributing may include: symptom overlap between the two diagnoses, misclassification due to symptom overlap, children with ASD may be more likely to express their gender identity and dysphoria, or they may be more likely to be referred to care to be diagnosed with either gender dysphoria or ASD.50

ADHD has also been evaluated among youth with gender dysphoria in cross-sectional analyses with prevalence estimates ranging from 4 to 20%.16 The prevalence in the Kaiser STRONG cohort was similar to that in this PEDSnet cohort with both studies showing higher odds of ADHD diagnoses than controls.8 TGD youth in the STRONG cohort also had increased risk of conduct disorder, ADHD and eating disorders.8

Our study has several limitations. Our de-identified data did not permit verification of any of these diagnoses against details in the medical record or evaluation of diagnostic measures used to assign these diagnoses. Gender dysphoria codes, as well as our outcome codes, could only be extracted from the problem list and billing diagnoses. Data from the past medical history are not available in PEDSnet, so some individuals may have been missed simply because diagnoses were only listed in the note or medical history, or omitted from the medical record entirely. Furthermore, as this is an EHR-based database, any codes of interest that were incorrectly entered or omitted would potentially change the outcomes. Since guidelines51 recommend psychosocial assessment prior to initiation of hormone therapy and/or surgery, there are likely more opportunities for youth with gender dysphoria to receive a behavioral health diagnosis compared to control youth. A higher percentage of youth in PEDSnet with gender dysphoria saw a behavioral health or neurodevelopmental provider compared to controls. We were not able to evaluate the timing of the outcome of interest relevant to the timing of the diagnosis of gender dysphoria. As this is a secondary data analysis, we do not know if those who received a diagnosis of gender dysphoria truly met the DSM-5 criteria at diagnosis. This group of youth with gender dysphoria may not be fully representative of TGD youth in the US, as many may not be seeking care at large, pediatric health systems or may not have received a diagnosis of gender dysphoria. Additionally, many TGD youth may not openly share their gender identity with their healthcare providers and/or may experience barriers to receiving gender affirming health care, and thus may never receive a diagnosis of gender dysphoria. Furthermore, TGD youth may not seek care out of fear of discrimination form healthcare providers, or because they do not desire medical interventions to affirm their gender identity. PEDSnet represents a clinical sample, not a population sample, and many youth living in rural areas have decreased access to gender-affirming care.52 Finally, our secondary data analysis did not permit evaluation of degree of parental and community support, or other protective factors. However, we did match on several important demographic factors including age, race, ethnicity, insurance status, and site.

Utilizing EHR data to further investigate the high prevalence of behavioral health diagnoses in youth with gender dysphoria provides novel opportunities for important future work including changes in behavioral health over time and before and after gender affirming care is initiated. There are other large, longitudinal studies in progress evaluating treatment and outcomes for TGD youth,53 however, prospective cohorts may be biased by willingness to consent to participate in the cohort and limit the ability to utilize control groups. EHR databases may also provide important insights into the type of care delivered and to whom, with attention to access to care by race and ethnicity, location and insurance status. Despite data showing non-white adult populations have a higher prevalence of transgender-identified individuals, over 70% of this sample was white and 60% had private insurance, observations that highlight the characteristics of cohort with gender dysphoria who access care at large pediatric health centers. These data are similar to those seen in prior studies which suggest TGD youth do not reflect the demographics of the broader TGD population.54 Several sites use an EHR smart form that captures gender identity, sex assigned at birth and pronouns, along with other relevant fields that will be used in future studies.

Future studies are needed for further delineation of risk factors for poor mental health outcomes and for evaluation of protective factors, as well as the impact of gender affirming care on youth mental health and wellbeing.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

We would like to thank the PEDSnet Data Coordinating Center for their support in the data acquisition and all PEDSnet site contributors. We would also like to thank the team at the Adult and Child Consortium for Health Outcomes Research and Delivery Science (ACCORDS) including prior analysts Jacob Thomas, Bridget Mosley and Angela Moss, who worked on data cleaning and the early analyses and Elizabeth Juarez-Colunga who helped develop the initial analysis plan. Ben Bear, MSW at Nemours read and commented on this paper. Nadia Dowshen is supported by the Stoneleigh Foundation.

Funding/Support:

This work was supported in part by NIH/NICHD K23HD092588 and R03HD102773 (SD), NIH/NICHD K12HD057022 (NN), Doris Duke Foundation (SD, NN), the Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute (RI-CRN-2020-007) (FSC) and the Seattle Children’s Institute Career Development Award (GS). Contents are the authors’ sole responsibility and do not necessarily represent views of the funders. The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study.

Abbreviations:

- ASD

autism spectrum disorder

- TGD

transgender and gender diverse

- U.S.

United States

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: NN previously consulted for Antares Pharma, Inc and Neurocrine Biosciences. The other authors have indicated that they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

References

- [1].Skordis N, Butler G, de Vries MC, Main K, Hannema SE. ESPE and PES International Survey of Centers and Clinicians Delivering Specialist Care for Children and Adolescents with Gender Dysphoria. Horm Res Paediatr. 2018;90:326–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Herman JL, Flores AR., Brown TNT., Wilson BDM., & Conron KJ . Age of individuals who identify as transgender in the United States. . Los Angeles, CA: The Williams Institute. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- [3].Johns MM, Lowry R, Andrzejewski J, Barrios LC, Demissie Z, McManus T, et al. Transgender Identity and Experiences of Violence Victimization, Substance Use, Suicide Risk, and Sexual Risk Behaviors Among High School Students - 19 States and Large Urban School Districts, 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68:67–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Association AP. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5®): American Psychiatric Pub; 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Rafferty J. Ensuring Comprehensive Care and Support for Transgender and Gender-Diverse Children and Adolescents. Pediatrics. 2018;142:e20182162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Hembree WC, Cohen-Kettenis PT, Gooren L, Hannema SE, Meyer WJ, Murad MH, et al. Endocrine Treatment of Gender-Dysphoric/Gender-Incongruent Persons: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017;102:3869–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Association AP. Guidelines for psychological practice with transgender and gender nonconforming people. American Psychologist. 2015;70:832–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Becerra-Culqui TA, Liu Y, Nash R, Cromwell L, Flanders WD, Getahun D, et al. Mental Health of Transgender and Gender Nonconforming Youth Compared With Their Peers. Pediatrics. 2018;141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Connolly MD, Zervos MJ, Barone CJ 2nd, Johnson CC, Joseph CL. The Mental Health of Transgender Youth: Advances in Understanding. J Adolesc Health. 2016;59:489–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Reisner SL, Vetters R, Leclerc M, Zaslow S, Wolfrum S, Shumer D, et al. Mental health of transgender youth in care at an adolescent urban community health center: a matched retrospective cohort study. J Adolesc Health. 2015;56:274–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Almeida J, Johnson RM, Corliss HL, Molnar BE, Azrael D. Emotional distress among LGBT youth: the influence of perceived discrimination based on sexual orientation. J Youth Adolesc. 2009;38:1001–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Warrier V, Greenberg DM, Weir E, Buckingham C, Smith P, Lai MC, et al. Elevated rates of autism, other neurodevelopmental and psychiatric diagnoses, and autistic traits in transgender and gender-diverse individuals. Nat Commun. 2020;11:3959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Grossman AH, D'Augelli AR. Transgender youth and life-threatening behaviors. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2007;37:527–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].James SE, Herman JL., Rankin S., Keisling M., Mottet L., & Anafi M. The Report of the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey. Washington, DC: National Center for Transgender Equality. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- [15].Glidden D, Bouman WP, Jones BA, Arcelus J. Gender Dysphoria and Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Sex Med Rev. 2016;4:3–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Thrower E, Bretherton I, Pang KC, Zajac JD, Cheung AS. Prevalence of autism spectrum disorder and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder amongst individuals with gender dysphoria: a systematic review. Journal of autism and developmental disorders. 2020;50:695–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Austin PC, Grootendorst P, Anderson GM. A comparison of the ability of different propensity score models to balance measured variables between treated and untreated subjects: a Monte Carlo study. Stat Med. 2007;26:734–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].D'Agostino RB Jr. Propensity score methods for bias reduction in the comparison of a treatment to a non-randomized control group. Stat Med. 1998;17:2265–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].American Psychiatric Association A. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-IV): Washington, DC: American psychiatric association Washington; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- [20].Imbens GW, Rubin DB. Causal inference in statistics, social, and biomedical sciences: Cambridge University Press; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- [21].Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB. Constructing a control group using multivariate matched sampling methods that incorporate the propensity score. The American Statistician. 1985;39:33–8. [Google Scholar]

- [22].Austin PC. Balance diagnostics for comparing the distribution of baseline covariates between treatment groups in propensity-score matched samples. Statistics in medicine. 2009;28:3083–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB. Reducing bias in observational studies using subclassification on the propensity score. Journal of the American statistical Association. 1984;79:516–24. [Google Scholar]

- [24].Austin PC. The performance of different propensity score methods for estimating marginal odds ratios. Statistics in medicine. 2007;26:3078–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Nokoff NJ, Scarbro S, Juarez-Colunga E, Moreau KL, Kempe A. Health and Cardiometabolic Disease in Transgender Adults in the United States: Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System 2015. J Endocr Soc. 2018;2:349–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Streed CG Jr, McCarthy EP, Haas JS. Self-reported physical and mental health of gender nonconforming transgender adults in the United States. LGBT health. 2018;5:443–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Guss CE, Williams DN, Reisner SL, Austin SB, Katz-Wise SL. Disordered Weight Management Behaviors, Nonprescription Steroid Use, and Weight Perception in Transgender Youth. J Adolesc Health. 2017;60:17–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Watson RJ, Veale JF, Saewyc EM. Disordered eating behaviors among transgender youth: Probability profiles from risk and protective factors. Int J Eat Disord. 2017;50:515–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Hendricks ML, Testa RJ. A conceptual framework for clinical work with transgender and gender nonconforming clients: An adaptation of the Minority Stress Model. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2012;43:460–7. [Google Scholar]

- [30].Chodzen G, Hidalgo MA, Chen D, Garofalo R. Minority stress factors associated with depression and anxiety among transgender and gender-nonconforming youth. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2019;64:467–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Kozee HB, Tylka TL, Bauerband LA. Measuring transgender individuals’ comfort with gender identity and appearance: Development and validation of the Transgender Congruence Scale. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2012;36:179–96. [Google Scholar]

- [32].Durwood L, McLaughlin KA, Olson KR. Mental Health and Self-Worth in Socially Transitioned Transgender Youth. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2017;56:116–23 e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Singh AA, Meng SE, Hansen AW. “I am my own gender”: Resilience strategies of trans youth. Journal of Counseling & Development. 2014;92:208–18. [Google Scholar]

- [34].Turban JL, King D, Carswell JM, Keuroghlian AS. Pubertal Suppression for Transgender Youth and Risk of Suicidal Ideation. Pediatrics. 2020;145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Rider GN, McMorris BJ, Gower AL, Coleman E, Eisenberg ME. Health and Care Utilization of Transgender and Gender Nonconforming Youth: A Population-Based Study. Pediatrics. 2018;141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Grossman AH, D'augelli AR, Frank JA. Aspects of psychological resilience among transgender youth. Journal of LGBT youth. 2011;8:103–15. [Google Scholar]

- [37].Simons L, Schrager SM, Clark LF, Belzer M, Olson J. Parental support and mental health among transgender adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2013;53:791–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Olson KR, Durwood L, DeMeules M, McLaughlin KA. Mental Health of Transgender Children Who Are Supported in Their Identities. Pediatrics. 2016;137:e20153223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Delozier AM, Kamody RC, Rodgers S, Chen D. Health Disparities in Transgender and Gender Expansive Adolescents: A Topical Review From a Minority Stress Framework. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2020;45:842–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Turban JL, King D, Carswell JM, Keuroghlian AS. Pubertal Suppression for Transgender Youth and Risk of Suicidal Ideation. Pediatrics. 2020;145:e20191725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].van der Miesen AIR, Steensma TD, de Vries ALC, Bos H, Popma A. Psychological Functioning in Transgender Adolescents Before and After Gender-Affirmative Care Compared With Cisgender General Population Peers. J Adolesc Health. 2020;66:699–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Sorbara JC, Chiniara LN, Thompson S, Palmert MR. Mental Health and Timing of Gender-Affirming Care. Pediatrics. 2020:e20193600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Skagerberg E, Di Ceglie D, Carmichael P. Brief Report: Autistic Features in Children and Adolescents with Gender Dysphoria. J Autism Dev Disord. 2015;45:2628–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Hisle-Gorman E, Landis CA, Susi A, Schvey NA, Gorman GH, Nylund CM, et al. Gender Dysphoria in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. LGBT Health. 2019;6:95–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Strang JF, Kenworthy L, Dominska A, Sokoloff J, Kenealy LE, Berl M, et al. Increased gender variance in autism spectrum disorders and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Arch Sex Behav. 2014;43:1525–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].van der Miesen AIR, de Vries ALC, Steensma TD, Hartman CA. Autistic Symptoms in Children and Adolescents with Gender Dysphoria. J Autism Dev Disord. 2018;48:1537–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].de Vries AL, Noens IL, Cohen-Kettenis PT, van Berckelaer-Onnes IA, Doreleijers TA. Autism spectrum disorders in gender dysphoric children and adolescents. J Autism Dev Disord. 2010;40:930–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Heylens G, Aspeslagh L, Dierickx J, Baetens K, Van Hoorde B, De Cuypere G, et al. The Co-occurrence of Gender Dysphoria and Autism Spectrum Disorder in Adults: An Analysis of Cross-Sectional and Clinical Chart Data. J Autism Dev Disord. 2018;48:2217–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Akgül GY, Ayaz AB, Yildirim B, Fis NP. Autistic Traits and Executive Functions in Children and Adolescents With Gender Dysphoria. J Sex Marital Ther. 2018;44:619–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Shumer DE, Reisner SL, Edwards-Leeper L, Tishelman A. Evaluation of Asperger Syndrome in Youth Presenting to a Gender Dysphoria Clinic. LGBT Health. 2016;3:387–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Coleman E, Bockting W, Botzer M, Cohen-Kettenis P, DeCuypere G, Feldman J, et al. Standards of care for the health of transsexual, transgender, and gender-nonconforming people, version 7. International Journal of Transgenderism. 2012;13:165–232. [Google Scholar]

- [52].Reirden DH, Glover JJ. Maximizing Resources: Ensuring Standard of Care for a Transgender Child in a Rural Setting. Am J Bioeth. 2019;19:66–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Olson-Kennedy J, Chan YM, Garofalo R, Spack N, Chen D, Clark L, et al. Impact of Early Medical Treatment for Transgender Youth: Protocol for the Longitudinal, Observational Trans Youth Care Study. JMIR Res Protoc. 2019;8:e14434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Flores AR, Brown TN, Herman J. Race and ethnicity of adults who identify as transgender in the United States: Williams Institute, UCLA School of Law Los Angeles, CA; 2016. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.