Abstract

Streptococcus pyogenes causes at least 750 million infections and more than 500,000 deaths each year. No vaccine is currently available for S. pyogenes and the use of human challenge models offer unique and exciting opportunities to interrogate the immune response to infectious diseases. Here, we use high-dimensional flow cytometric analysis and multiplex cytokine and chemokine assays to study serial blood and saliva samples collected during the early immune response in human participants following challenge with S. pyogenes. We find an immune signature of experimental human pharyngitis characterised by: 1) elevation of serum IL-1Ra, IL-6, IFN-γ, IP-10 and IL-18; 2) increases in peripheral blood innate dendritic cell and monocyte populations; 3) reduced circulation of B cells and CD4+ T cell subsets (Th1, Th17, Treg, TFH) during the acute phase; and 4) activation of unconventional T cell subsets, γδTCR + Vδ2+ T cells and MAIT cells. These findings demonstrate that S. pyogenes infection generates a robust early immune response, which may be important for host protection. Together, these data will help advance research to establish correlates of immune protection and focus the evaluation of vaccines.

Subject terms: Bacterial infection, Mucosal immunology

Streptococcus pyogenes causes ~750 million infections and more than 500,000 deaths each year. In this study, human volunteers were challenged with S. pyogenes and participants that developed pharyngitis had elevated levels of cytokines, and increased migration and activation of immune cells.

Introduction

Streptococcus pyogenes is a human-restricted pathogen with a profound and persistent global burden of disease1. It is a ubiquitous human pathogen and is responsible for more than 500,000 deaths each year2,3. Acute pharyngitis is the most common of all clinical syndromes due to S. pyogenes4. The diverse clinical spectrum of S. pyogenes also includes severe diseases including scarlet fever, cellulitis, necrotising fasciitis, toxic shock syndrome and post-infectious glomerulonephritis, acute rheumatic fever, and its sequelae rheumatic heart disease1. No vaccine is currently available for S. pyogenes and greater efforts are required to develop new vaccines or therapeutics to prevent serious disease and death caused by this bacterium.

Critical knowledge gaps have hindered S. pyogenes vaccine development5. Understanding the human immune response to S. pyogenes and identifying correlates of protection could accelerate the development of effective vaccines6. Animal models and in vitro studies are limited in their capacity to replicate the full clinical spectrum of human diseases caused by S. pyogenes7. Previous experimental human challenge studies were carried out decades ago, prior to the sophisticated immunological technologies available today8–10. As well as providing a platform for evaluation of candidate vaccines, a human-challenge model of S. pyogenes infection offers the unique opportunity to interrogate the dynamic host immune response to infection using samples collected before, during, and after development of disease. Human-challenge models have been established for other infectious pathogens such as Vibrio cholerae, Salmonella Typhi and Paratyphi, Streptococcus pneumoniae, respiratory syncytial virus and malaria, and have enormous potential to successfully guide vaccine development11–15. Recently, a new human-challenge model of S. pyogenes pharyngitis in healthy adults was established in an initial dose-finding clinical trial, after an extensive effort to select and characterise a challenge strain and develop a study protocol to protect participants and promote the model’s clinical relevance16–18.

In this study, we undertook comprehensive immune profiling of the early human immune response in 25 healthy adults from this initial trial who were challenged with S. pyogenes, 19 of whom subsequently developed acute symptomatic pharyngitis17. We focused our studies on the acute immune response, prior to treating participants with antibiotics to cure disease. We used high-dimensional flow cytometry and serum and saliva cytokine and chemokine analyses to identify an immune signature associated with acute pharyngitis, that will aid in the development of a future vaccine for S. pyogenes.

Results

Human-challenge model of S. pyogenes pharyngitis

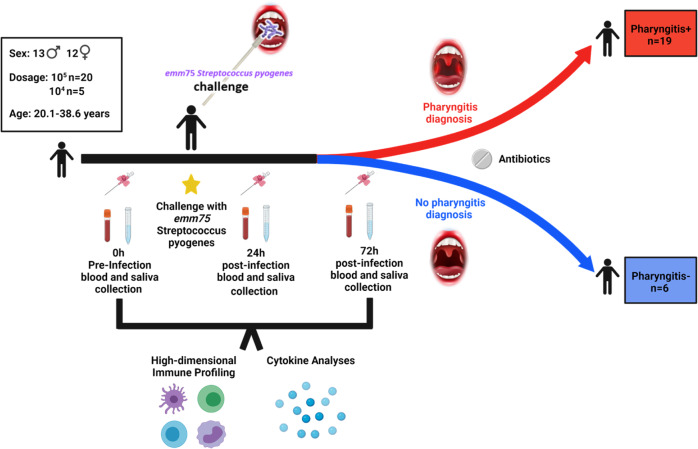

As reported previously, 25 healthy adult participants (12♀, 13♂, mean age 27.6 years) were enrolled and challenged with emm75 S. pyogenes applied by swab directly to the oropharynx (Fig. 1)17. Of the 25 participants, 20 were challenged from single-dose vials containing 1.72 × 105 CFU of emm75 S. pyogenes, while the remaining 5 were challenged with 1.62 × 104 CFU. After challenge, 18 participants met pre-defined clinical and microbiologic criteria for S. pyogenes pharyngitis (P+). Subsequent review of clinical, microbiological and immunological results found a protocol deviation affecting an additional volunteer (participant 057) who was previously described as ‘likely pharyngitis’ in the previous paper and considered in the P+ group here17. Six participants did not develop pharyngitis (P−) (Fig. 1)17. Pharyngitis was generally diagnosed between 36 and 72 h (h) after challenge. All participants were treated with antibiotics, either at the time of diagnosis (P+) or ~120 h after challenge in those without pharyngitis. Pharyngeal colonisation by the challenge strain was measured by quantitative PCR19, and a cycle threshold (CT)-value >35 was classified as no pharyngeal colonisation with S. pyogenes. All 19 P+ participants reported CT-values indicative of pharyngeal colonisation (median 21.24 at the timepoint of pharyngitis diagnosis, IQR 20.61–22.64) while only one P− participant exhibited a CT-value of <35 at any timepoint17.

Fig. 1. Human challenge with Streptococcuspyogenes.

Schematic of Streptococcus pyogenes human-challenge model. Details participant demographics, timepoints, outcomes and analyses performed. Figure created with BioRender.com.

Distinct cytokine and chemokine profiles are associated with S. pyogenes pharyngitis

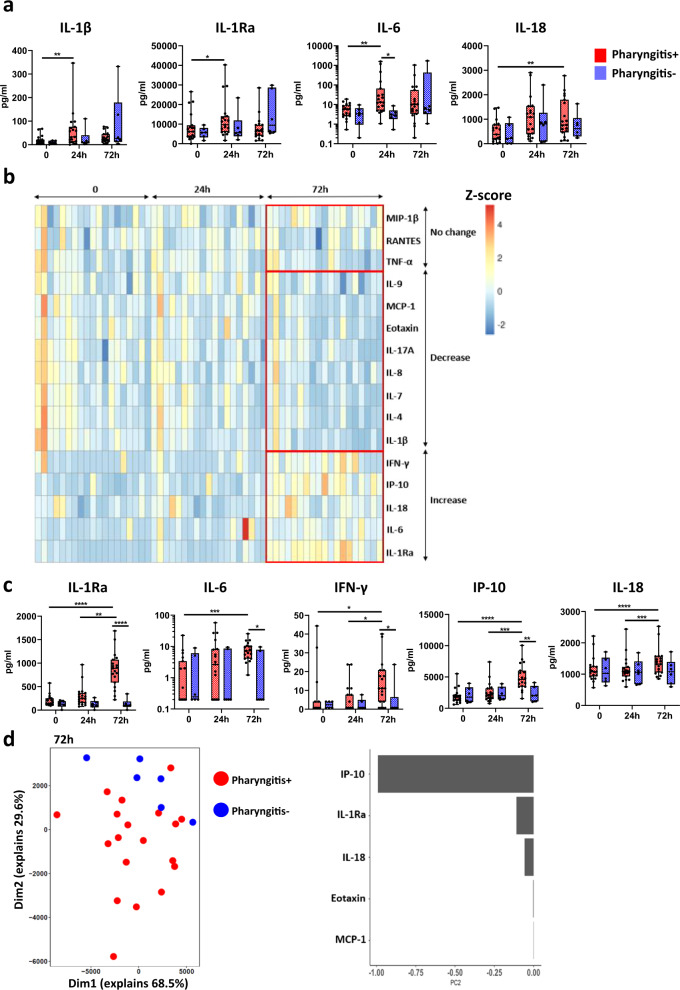

We previously demonstrated that IFN-γ and IL-6 were increased in the serum of P+ compared to P− participants by 48 h17. To gain a greater understanding of the soluble factors involved in the acute immune response to S. pyogenes challenge, we used multiplex assays to assess a larger panel of cytokines and chemokines in the saliva and serum of participants. Following challenge, saliva IL-1β, IL-1Ra and IL-6 were all increased at 24 h and IL-18 was also increased at 72 h in P+ participants (Fig. 2a). Most other soluble factors in the saliva did not change over time in the P+ participants (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Fig. 2. Distinct cytokine profiles in participants that developed pharyngitis.

a Saliva cytokines and chemokines at timepoint 0 h (pre-infection) 24 h post-infection (24 h) and 72 h post-infection (72 h) between pharyngitis positive (n = 19, red) and negative (n = 6, blue) participants. b Heatmap summary of serum cytokines and chemokines analysed with normalized Z-score. c Serum cytokines and chemokines that had increased during infection. d Unsupervised PCA analysis of serum cytokines and chemokines between pharyngitis positive and negative participants at 72 h post-infection and the top 5 factors contributing to differences. Data presented as boxplots show median ± IQR with min–max whiskers. A Friedman’s test was used to compare responses over time in P+ and P− groups, while a Mann–Whitney U-test was performed to compare differences between P+ and P− groups. All tests performed were two-tailed and a p-value <0.05 was considered significant; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

Analysis of the serum of P+ participants also revealed increases in IL-1Ra, IL-6, IFN-γ and IL-18, with the greatest differences observed at 72 h, consistent with a delay in the kinetics of the immune response from the site of infection to the blood (Fig. 2b, c). Notably, levels of the chemokine IP-10 (CXCL10) were also greatly increased following challenge with S. pyogenes (Fig. 2b, c). IP-10 can directly kill S. pyogenes which suggests elevated IP-10 may promote protective immunity by enhancing bacterial clearance20. In most cases, the levels of these soluble factors were significantly higher at 72 h in P+ compared to P− participants (Fig. 2b, c). A reduction in IL-1β, IL-4, IL-7, IL-8, IL-9, IL-17A, eotaxin, and MCP-1 was also observed at 72 h in the serum of P+ participants, while levels of RANTES, TNF-α and MIP-1β did not change (Fig. 2b and Supplementary 2). Unsupervised principal component analysis (PCA) confirmed the differences observed between P+ and P− participants at 72 h, with IP-10, IL-1Ra and IL-18 the largest contributors in the early immune response to S. pyogenes (Fig. 2d). Overall, these data identify changes in chemokine and cytokine expression associated with the development of acute pharyngitis.

Cellular signature to experimental human S. pyogenes pharyngitis

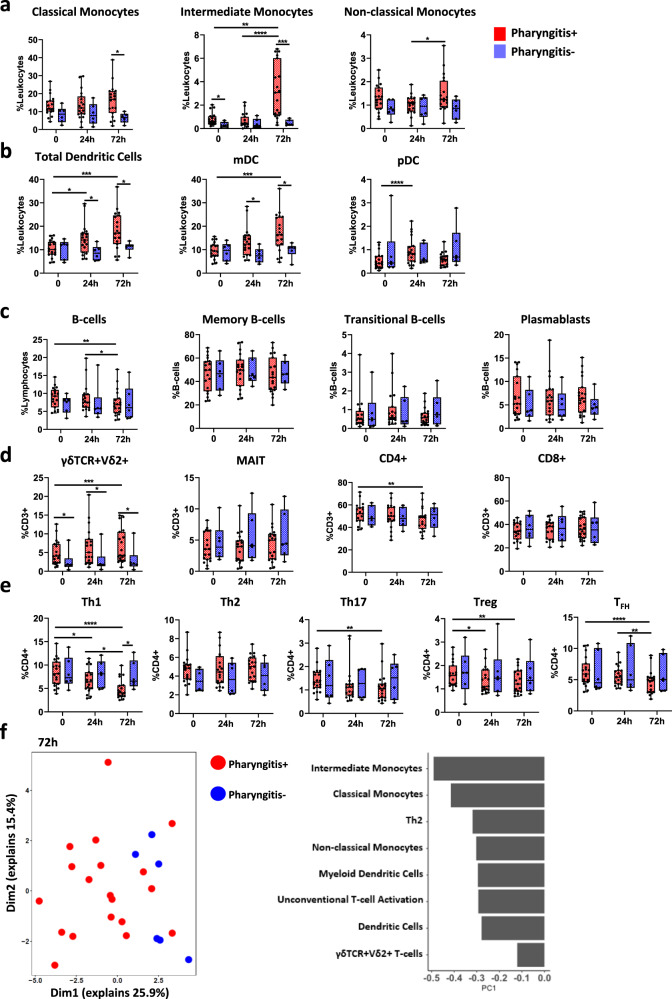

Flow cytometry was used to characterise 43 immune cell populations, including innate cells, T cells and B cells in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) (Supplementary Figs. 3–5). Innate cells, such as intermediate and non-classical monocytes increased over time in P+ participants but not in P− participants, and classical monocytes were significantly elevated in P+ participants at 72 h compared to P− participants (Fig. 3a). Total dendritic cells and myeloid dendritic cells increased over time and were higher in P+ participants compared to P− participants, while plasmacytoid dendritic cells in P+ participants increased at 24 h (Fig. 3b). A decrease in CD56bright natural killer (NK) cells occurred from 24 to 72 h, and a rise of perforin expression at 72 h was also observed, although no other major changes in NK cell populations were observed between P+ and P− participants (Supplementary Fig. 6a). In response to S. pyogenes, monocytes and dendritic cells are crucial to phagocytosis, pro-inflammatory cytokine secretion, neutrophil recruitment and T cell activation7,21. In mice, depletion of myeloid dendritic cells resulted in uncontrolled dissemination of S. pyogenes22. Taken together, our results suggest monocytes and dendritic cells play a key role in experimental human S. pyogenes pharyngitis.

Fig. 3. Unique cellular profiles in participants that developed pharyngitis.

a Differences in monocyte subsets at timepoint 0 h (pre-infection) 24 h post-infection (24 h) and 72 h post-infection (72 h) between pharyngitis positive (n = 19, red) and negative (n = 6, blue) participants. b Dendritic cell subsets. c B cells and B-cell subsets. d γδTCR + Vδ2+ T cells, MAIT cells, CD4+ T cells and CD8+ T cells. e CD4+ T cell subsets. f Unsupervised PCA analysis of cellular subsets between pharyngitis positive and negative individuals at 72 h post-infection and the top 8 factors contributing to differences. Data presented as boxplots show median ± IQR with min–max whiskers. A Friedman’s test was used to compare responses over time in P+ and P− groups, while a Mann–Whitney U-test was performed to compare differences between P+ and P− groups. All tests performed were two-tailed and a p-value <0.05 was considered significant; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

B cells decreased in P+ participants suggesting migration to the site of infection. No changes were observed in memory B cells, transitional B cells and plasmablasts during acute disease (Fig. 3c), and no differences were observed in the surface expression of IgD, IgM and IgG on B cells between P+ and P− participants (Supplementary Fig. 6b). Unconventional T cell populations such as mucosal-associated invariant T (MAIT) cells and γδTCR + Vδ2+ T cells are activated during infection by other respiratory pathogens and bridge the gap between innate and adaptive immunity23. The proportion of MAIT cells was similar between P+ and P− participants, however, γδTCR + Vδ2+ T cells were increased in P+ participants after S. pyogenes infection (Fig. 3d). No differences were observed in cytotoxic CD8+ T cells, however, CD4+ T cells were decreased 72 h after challenge (Fig. 3d). More detailed analysis of CD4+ T cell subsets revealed reduced frequencies of T-helper type 1 (Th1), Th17, regulatory T cells (Treg) and follicular helper T cells (TFH) at 72 h in P+ participants (Fig. 3e), suggesting T cell migration towards the site of infection. Th17 cells are associated with enhanced clearance of S. pyogenes at the site of infection, therefore, they might be migrating to infected tissues to mediate local immunity24.

Unsupervised PCA analysis of the cellular differences between P+ and P− participants at 72 h confirmed that monocytes, dendritic cells, and γδTCR + Vδ2+ T cells contributed to the immune signature of participants who developed pharyngitis (Fig. 3f). Although, there were few differences in immune cell populations at 0 h and 24 h post challenge (Fig. 3), intermediate monocytes (Fig. 3a) and γδTCR + Vδ2+ T cells (Fig. 3d) were higher in P+ participants compared to P− participants prior to challenge. Both intermediate monocytes and γδTCR + Vδ2+ T cells secrete high levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines upon activation and can influence the immune response to infectious disease25,26. Collectively, our data support a role for specific subsets of dendritic cells, monocytes, CD4+ T cells and γδTCR + Vδ2+ T cells in acute S. pyogenes pharyngitis. Further correlation of these subsets with disease pathogenesis or protection will be a key target for future S. pyogenes human-challenge studies and early phase trials evaluating vaccines.

T cell activation and migration in experimental human S. pyogenes pharyngitis

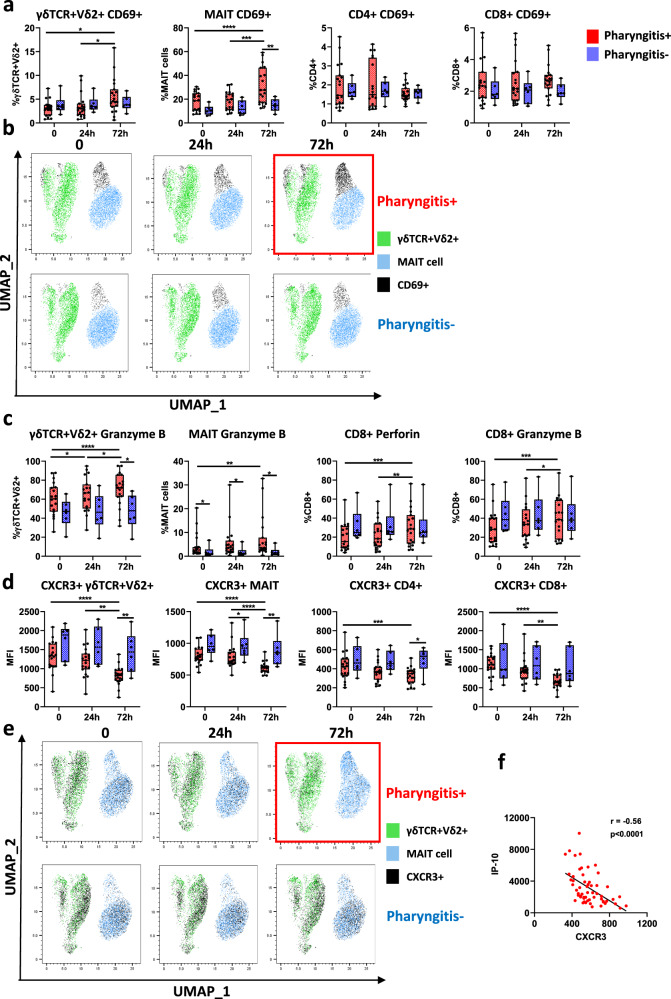

To further elucidate functional immune responses during acute S. pyogenes pharyngitis, we analysed cells for CD69 expression (a marker of activation), CXCR3 (a marker of migration) and intracellular perforin and granzyme-B expression (cytotoxic proteins involved in cell lysis). We found that γδTCR + Vδ2+ T cells and MAIT cells upregulated CD69 at 72 h in P+ participants, but only MAIT cell activation was higher in P+ compared to P− participants at 72 h (Fig. 4a). This was further validated by unsupervised UMAP analysis showing enhanced CD69+ expression on γδTCR + Vδ2+ T cells and MAIT cells in P+ participants (Fig. 4b). In contrast, CD4+ and CD8+ T cells did not upregulate CD69 expression during acute pharyngitis (Fig. 4a). Granzyme-B was also upregulated on γδTCR + Vδ2+ T cells and MAIT cells in P+ participants compared to P− participants (Fig. 4c). While no significant differences were observed in perforin and granzyme-B expression on cytotoxic CD8+ T cells between P+ and P− participants, expression of these cytotoxic molecules increased in CD8+ T cells in P+ participants over time (Fig. 4c). Although S. pyogenes is typically considered an extracellular pathogen, it may evade the immune response by invading epithelial cells and macrophages27,28, and this may account for the differential upregulation of perforin and granzyme-B across T cell subsets.

Fig. 4. Activation and migration of T cell subsets during acute pharyngitis.

a CD69+ activation on T cell subsets timepoint 0 h (pre-infection), 24 h post-infection (24 h) and 72 h post-infection (72 h) between pharyngitis positive (n = 19, red) and negative (n = 6, blue) participants. b Unsupervised UMAP analysis of CD69+ expression (black) on unconventional T cell subsets. c Differences in expression of cytotoxic markers (perforin and Granzyme-B) in γδTCR + Vδ2+ T cells, MAIT cells and CD8+ T cells. d Changes in T cell CXCR3+ median fluorescence intensity (MFI) over time. e Unsupervised UMAP analysis of CXCR3+ expression (black) on unconventional T cell subsets. f Spearman’s correlation between CXCR3 expression and IP-10 secretion. Data presented as boxplots show median ± IQR with min–max whiskers. A Friedman’s test was used to compare responses over time in P+ and P− groups, while a Mann–Whitney U-test was performed to compare differences between P+ and P− groups. All tests performed were two-tailed and a p-value <0.05 was considered significant; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

Expression of CXCR3 was greatly decreased on CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, γδTCR + Vδ2+ T cells and MAIT cells in P+ participants over time (Fig. 4d). Unsupervised UMAP analysis also confirmed the lower CXCR3 expression on γδTCR + Vδ2+ T cells and MAIT cells in participants that developed pharyngitis (Fig. 4e). The decrease in CXCR3 expression (Fig. 4d, e) coincided with increased secretion of serum IP-10 (Fig. 4f), which activates CXCR3 to promote T cell migration29. These data suggest a relationship between the chemokine IP-10 and CXCR3 expression which could be important for enhancing T cell migration from the blood.

Discussion

The controlled human-challenge model of S. pyogenes infection allowed us to study the immune response to this important human-restricted pathogen, providing greater in-depth analysis than had previously been possible7. Here, we have defined a distinct inflammatory immune signature associated with the development of acute S. pyogenes pharyngitis in healthy adults. These findings address a critical knowledge gap in our understanding of host immunity to this pathogen and will help establish a platform for evaluating the immunogenicity and effectiveness of future S. pyogenes vaccines.

Acute pharyngitis in participants challenged with S. pyogenes was marked by a strong inflammatory immune response mediated by monocytes, dendritic cells and early activation of unconventional T cells to initiate the immune response to this pathogen. Monocytes and dendritic cells were increased in the blood of participants who developed pharyngitis. Activation of monocytes to induce pro-inflammatory responses occurs following binding of TLR2 to the Streptococcal Inhibitor of Complement (SIC) protein secreted by S. pyogenes which may explain the elevated intermediate monocyte frequency30. In addition, the elevation of monocytes and dendritic cells was associated with increased levels of IL-1Ra, IL-18 and IP-10, produced in response to infection31–33. These may be important as IP-10 has been previously established as a biomarker for viral and bacterial infections34–36. IL-8 and IL-17A facilitate the recruitment of neutrophils, therefore, their reduction in other studies suggests inhibition of neutrophil recruitment during acute pharyngitis37,38. S. pyogenes employs many strategies to inhibit neutrophil recruitment, one of which is through SpyCEP expression, a protease designed to cleave IL-837. In contrast, IL-4, which was reduced in the serum of P+ participants after infection, has been shown to inhibit neutrophil influx, and the balance between these cytokines may be important in regulating neutrophil activity during S. pyogenes infection39.

The activation of γδTCR + Vδ2+ T cells and MAIT cells, but not other T cell subsets, implies that unconventional T cells may contribute to the inflammatory response during acute S. pyogenes pharyngitis. A previous study suggested that MAIT cells were involved in the pathogenesis of human toxic shock syndrome caused by S. pyogenes, a more severe manifestation of this bacterial infection40. The activation of MAIT cells is likely mediated by the production of IL-18 from innate cells as S. pyogenes does not express riboflavin intermediates required to activate MAIT cells via their T-cell receptor41 and both MAIT cells and γδTCR + Vδ2+ T cells express IL-18R and are potently activated by IL-1842,43. T cell migration to the site of infection can be both beneficial and harmful. While T cell migration is required for resolution of disease, excessive migration and release of inflammatory factors can exacerbate disease44. The reduced frequency of Treg cells in the blood suggests these cells have migrated to the site of infection to modulate the immune response to S. pyogenes, although some evidence suggests that Tregs may facilitate immune evasion by S. pyogenes45. Moreover, reduced CXCR3 expression observed on T cells during acute pharyngitis suggests that S. pyogenes infection promotes migration of CD4+ T cells from the blood. These data suggest that CD4+ T cell migration and activation of unconventional T cells may serve as an early marker of S. pyogenes immunity in humans40,46.

A key focus of vaccine research is to induce protection by emulating natural immune responses. While early antibiotic therapy may shorten the immune response, it is reasonable to presume the pattern of early immune responses in these healthy participants was associated with natural protection. Therefore, vaccine candidates that promote early immune responses by monocytes, dendritic cells and unconventional T cells could enhance natural immunity towards by S. pyogenes. There is currently active interest in using adjuvants or other delivery platforms that induce Th1 systemic responses and evidence from animal models show improved protection against S. pyogenes disease due to enhanced Th1 immunity47.

A limitation of this study is the lack of direct sampling at the site of infection. Direct mucosal micro-sampling has contributed significant insight into human-challenge models with other pathogens such as RSV and S. pneumoniae and will be explored for use in future S. pyogenes human-challenge trials, although there are important safety considerations12,13. The strain used in this study was selected for its predictable and limited virulence and the participants being at low risk of complicated disease16–18, thus analysis of the immune response to other strains of S. pyogenes could be beneficial. Although we identified several important features in the human immune response to S. pyogenes, increased numbers of participants may strengthen the findings in this study and provide a greater understanding of disease pathogenesis and protective immunity towards S. pyogenes. A key strength of this study was the serial collection of blood and saliva samples before and after challenge with S. pyogenes, which allowed the identification of changes to the immune system during the critical early stages of infection. Further insights will come from planned randomised placebo-controlled human-challenge trials evaluating S. pyogenes vaccines, including a modified sampling schedule informed by these findings, as well as mucosal micro-sampling and whole blood studies that will bring the role of neutrophils into view.

This is the first study to comprehensively characterise the dynamic human cellular immune response to S. pyogenes infection. The hallmarks of acute pharyngitis are increased levels of monocyte and dendritic cell subsets, elevation of IL-1Ra, IP-10 and IL-18, activation of unconventional T cells, and migration of B cells and CD4+ T-cell subsets from the blood. This immune signature will now be traced across the S. pyogenes research landscape, from in vitro assays, samples from natural human infections, and in future human-challenge and field trials evaluating vaccines. Focused efforts to establish correlates of immune protection and development of vaccines are needed to prevent morbidity and mortality across the S. pyogenes clinical spectrum.

Methods

Study design and participants

Strain selection and characterisation, protocol development, and CHIVAS-M75 clinical trial results have previously been described16–18. Characterization of the cellular immune response of acute pharyngitis following experimental human challenge with S. pyogenes is a secondary outcome of the study protocol16. Briefly, healthy adults (aged 20–39) were challenged with emm75 S. pyogenes applied directly with a swab to the pharynx, then closely monitored for development of pharyngitis as inpatients for up to 5 nights. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs), serum and saliva samples were collected prior to challenge, 24 and 72 h post-infection or prior to discharge.

The CHIVAS-M75 trial, including immunological studies, was approved by the Alfred Hospital Human Research Ethics Committee (500/17). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. A safety committee with an independent chair reviewed safety data and clinical details for each participant, meeting at pre-determined timepoints to approve study continuation.

Study reagents

RPMI-160, foetal bovine serum (FBS), L-glutamine and penicillin-streptomycin were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, USA. Anti-mouse compensation beads were purchased from BD Bioscience, San Diego, CA, USA. All flow cytometry antibodies used, and their suppliers, are indicated in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2.

Flow cytometry

Cryopreserved PBMCs were thawed at 37 °C then washed with 10 ml R10 media (RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS, 2 mM L-glutamine, 1000 IU penicillin-streptomycin) and centrifuged at 400 × g for 5 min. PBMCs were washed with 5 ml PBS and centrifuged at 400 × g for 5 min then blocked (50 μl of 1% human FC-block and 10% normal rat serum in PBS) for 20 min on ice. PBMCs were then washed with 1 ml FACS buffer (PBS supplemented with 2% FBS and 2 mM EDTA) and stained with 50 µl of antibody cocktail 1, 2 or 3 (Supplementary Table 1) for 20 min on ice. PBMCs were washed in 1 ml of FACS buffer then resuspended in 100 µl of fixation buffer (BD, Bioscience, San Diego, CA, USA) and incubated on ice for 20 min. Following, PBMCs were washed twice in permeabilisation buffer prior to intracellular antibody staining. PBMCs were stained for 30 min on ice, washed then resuspended in 100 µl FACS buffer for acquisition using the Cytek Aurora. Compensation was performed at the time of acquisition using compensation beads. Data were analysed using Flowjo v10.7.1 software. UMAP was generated using the UMAP FlowJo plugin and 5000 events per sample were concatenated. Gating strategies are shown in Supplementary Figs. 3, 4, 5.

Multiplex cytokine/chemokine assay

A commercial multiplex bead array kit (27-plex human cytokine assay M500KCAF0Y; Bio-Rad, New South Wales, Australia), with the numbers representing the lower limit of detection in pg/ml for each analyte. IL-1β (0.29), IL-1ra (6.21), IL-2 (1.29), IL-4 (0.19), IL-5 (3.63), IL-6 (0.38), IL-7 (1.92), IL-8 (0.85), IL-9 (3.62), IL-10 (1.06), IL-12(p70) (1.43), IL-13 (0.31), IL-15 (12.42), IL-17A (2.44), eotaxin (0.14), FGF-basic (3.26), G-CSF (6.35), GM-CSF (0.48), MCP-1 (0.53), IFN-γ (1.57), TNF-α (3.33), IP-10 (3.41), RANTES (16.72), MIP-1α (0.12), MIP-1β (1.41), PDGF (7.12) and VEGF (18.01) was measured from serum and saliva according to manufacturer’s instructions. Results were analysed on a Luminex 200 instrument (Luminex, Texas, USA) fitted with the Bio-Plex Manager Version 6 software and results were reported in pg/ml. IL-18 was measured by a commercial ELISA kit (R&D Systems, Minnesota, USA) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Results were measured at an optical density of 450 nm (reference wavelength 630 nm), and concentrations in pg/mL were derived from the standard curve.

Statistical analysis

Cellular and cytokine data were presented as a boxplot (median ± IQR with min–max whiskers). A Friedman test was performed to compare cellular and cytokine paired data at baseline (0), 24 h post-infection and 72 h post-infection. An unpaired non-parametric Mann–Whitney U-test was used to compare cellular and cytokine data between P+ and P− groups. A linear regression was used to correlate CXCR3 expression (MFI) and IP-10 concentrations. The data was graphically represented and statistically analysed using Graphpad prism v8 software (Graphpad Software Inc, California, USA). Heatmaps and PCA plots were generated using R software v3.6.1. All tests performed were two-tailed and a p-value <0.05 was considered significant.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

J.A. is supported by an Australian Postgraduate Award Scholarship. D.G.P. is supported by CSL Centenary Fellowship. P.V.L. is a recipient of an Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Career Development Fellowship (GNT1146198). A.C.S. is supported by a Viertel Senior Medical Research Fellowship. B.N. is supported by an NHMRC Investigator Grant (APP1173314). J.O. was supported by an NHMRC postgraduate scholarship (GNT1133299). The challenge study was supported by a NHMRC Project Grant (GNT1099183). We would like to thank Prof. Laura Mackay for her input into the manuscript.

Source data

Author contributions

J.A. collected the data, performed the analyses, and wrote the original draft; S.I. contributed to analysis, visualisation and interpretation of data and critically revised the manuscript; H.R.F., K.I.A., S.J. and B.N. contributed to interpretation of results and revised the manuscript; J.O., A.S., P.V.L. and D.G.P. conceived the study and provided major input into the manuscript revision and data interpretation. All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Stephen Gordon, and the other, anonymous, reviewer for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Data availability

Most data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article (and its supplementary information files). Any additional data are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request. Source data are provided with this paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Joshua Osowicki, Andrew C. Steer, Paul V. Licciardi, Daniel G. Pellicci.

Contributor Information

Joshua Osowicki, Email: joshua.osowicki@rch.org.au.

Andrew C. Steer, Email: andrew.steer@rch.org.au

Paul V. Licciardi, Email: paul.licciardi@mcri.edu.au

Daniel G. Pellicci, Email: dan.pellicci@mcri.edu.au

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-022-28335-3.

References

- 1.Carapetis JR, Steer AC, Mulholland EK, Weber M. The global burden of group A streptococcal diseases. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2005;5:685–694. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(05)70267-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Steer AC, Lamagni T, Curtis N, Carapetis JR. Invasive group a streptococcal disease: epidemiology, pathogenesis and management. Drugs. 2012;72:1213–1227. doi: 10.2165/11634180-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cannon JW, Bennett J, Baker MG, Carapetis JR. Time to address the neglected burden of group A Streptococcus. Med J. Aust. 2021;215:94–94.e91. doi: 10.5694/mja2.51149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bisno AL. Acute pharyngitis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001;344:205–211. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200101183440308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Osowicki J, et al. WHO/IVI global stakeholder consultation on group A Streptococcus vaccine development: report from a meeting held on 12–13 December 2016. Vaccine. 2018;36:3397–3405. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.02.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tsoi SK, Smeesters PR, Frost HR, Licciardi P, Steer AC. Correlates of protection for M protein-based vaccines against group A Streptococcus. J. Immunol. Res. 2015;2015:167089. doi: 10.1155/2015/167089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Soderholm AT, Barnett TC, Sweet MJ, Walker MJ. Group A streptococcal pharyngitis: Immune responses involved in bacterial clearance and GAS-associated immunopathologies. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2018;103:193–213. doi: 10.1189/jlb.4MR0617-227RR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.D’Alessandri R, et al. Protective studies with group A streptococcal M protein vaccine. III. Challenge of volunteers after systemic or intranasal immunization with Type 3 or Type 12 group A Streptococcus. J. Infect. Dis. 1978;138:712–718. doi: 10.1093/infdis/138.6.712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fox EN, Waldman RH, Wittner MK, Mauceri AA, Dorfman A. Protective study with a group A streptococcal M protein vaccine. Infectivity challenge of human volunteers. J. Clin. Invest. 1973;52:1885–1892. doi: 10.1172/JCI107372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Polly SM, Waldman RH, High P, Wittner MK, Dorfman A. Protective studies with a group A streptococcal M protein vaccine. II. Challange of volenteers after local immunization in the upper respiratory tract. J. Infect. Dis. 1975;131:217–224. doi: 10.1093/infdis/131.3.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Jong SE, et al. Systems analysis and controlled malaria infection in Europeans and Africans elucidate naturally acquired immunity. Nat. Immunol. 2021;22:654–665. doi: 10.1038/s41590-021-00911-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Habibi, M. S. et al. Neutrophilic inflammation in the respiratory mucosa predisposes to RSV infection. Science370, 10.1126/science.aba9301 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Collins AM, et al. First human challenge testing of a pneumococcal vaccine. Double-blind randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2015;192:853–858. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201503-0542OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen WH, et al. Single-dose live oral cholera vaccine CVD 103-HgR protects against human experimental infection with Vibrio cholerae O1 El Tor. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2016;62:1329–1335. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dobinson HC, et al. Evaluation of the clinical and microbiological response to Salmonella Paratyphi A infection in the first paratyphoid human challenge model. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2017;64:1066–1073. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Osowicki J, et al. Controlled human infection for vaccination against Streptococcus pyogenes (CHIVAS): establishing a group A Streptococcus pharyngitis human infection study. Vaccine. 2019;37:3485–3494. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.03.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Osowicki, J. et al. A controlled human infection model of Streptococcus pyogenes pharyngitis (CHIVAS-M75): an observational, dose-finding study. Lancet Microbe 2, e291–e299 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Osowicki, J. et al. A controlled human infection model of group A Streptococcus pharyngitis: which strain and why? mSphere4, 10.1128/mSphere.00647-18 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Fabri LV, et al. An emm-type specific qPCR to track bacterial load during experimental human Streptococcus pyogenes pharyngitis. BMC Infect. Dis. 2021;21:463. doi: 10.1186/s12879-021-06173-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Egesten A, et al. The CXC chemokine MIG/CXCL9 is important in innate immunity against Streptococcus pyogenes. J. Infect. Dis. 2007;195:684–693. doi: 10.1086/510857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gaudino SJ, Kumar P. Cross-talk between antigen presenting cells and T cells impacts intestinal homeostasis, bacterial infections, and tumorigenesis. Front Immunol. 2019;10:360. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Loof TG, Goldmann O, Medina E. Immune recognition of Streptococcus pyogenes by dendritic cells. Infect. Immun. 2008;76:2785–2792. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01680-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mayassi T, Barreiro LB, Rossjohn J, Jabri B. A multilayered immune system through the lens of unconventional T cells. Nature. 2021;595:501–510. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03578-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fan X, et al. Sortase A induces Th17-mediated and antibody-independent immunity to heterologous serotypes of group A streptococci. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e107638. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0107638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dantzler KW, de la Parte L, Jagannathan P. Emerging role of γδ T cells in vaccine-mediated protection from infectious diseases. Clin. Transl. Immunol. 2019;8:e1072. doi: 10.1002/cti2.1072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sampath P, Moideen K, Ranganathan UD, Bethunaickan R. Monocyte subsets: phenotypes and function in tuberculosis infection. Front Immunol. 2018;9:1726. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nozawa, T. et al. Intracellular group A Streptococcus induces Golgi fragmentation to impair host defenses through streptolysin O and NAD-glycohydrolase. mBio12, 10.1128/mBio.01974-20 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Thulin P, et al. Viable group A streptococci in macrophages during acute soft tissue infection. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e53. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Groom JR, Luster AD. CXCR3 in T cell function. Exp. Cell Res. 2011;317:620–631. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2010.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Neumann A, et al. Streptococcal protein SIC activates monocytes and induces inflammation. iScience. 2021;24:102339. doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2021.102339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bossaller L, et al. Cutting edge: FAS (CD95) mediates noncanonical IL-1β and IL-18 maturation via caspase-8 in an RIP3-independent manner. J. Immunol. 2012;189:5508–5512. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1202121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dayer JM, Oliviero F, Punzi L. A brief history of IL-1 and IL-1 Ra in rheumatology. Front Pharm. 2017;8:293. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2017.00293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu M, et al. CXCL10/IP-10 in infectious diseases pathogenesis and potential therapeutic implications. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2011;22:121–130. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2011.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hayney MS, et al. Serum IFN-γ-induced protein 10 (IP-10) as a biomarker for severity of acute respiratory infection in healthy adults. J. Clin. Virol. 2017;90:32–37. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2017.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hoffmann J, et al. Viral and bacterial co-infection in severe pneumonia triggers innate immune responses and specifically enhances IP-10: a translational study. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:38532. doi: 10.1038/srep38532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Latorre I, et al. IP-10 is an accurate biomarker for the diagnosis of tuberculosis in children. J. Infect. 2014;69:590–599. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2014.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Soderholm AT, et al. Group A Streptococcus M1T1 intracellular infection of primary tonsil epithelial cells dampens levels of secreted IL-8 through the action of SpyCEP. Front Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2018;8:160. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2018.00160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Griffin GK, et al. IL-17 and TNF-α sustain neutrophil recruitment during inflammation through synergistic effects on endothelial activation. J. Immunol. 2012;188:6287–6299. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1200385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Woytschak J, et al. Type 2 interleukin-4 receptor signaling in neutrophils antagonizes their expansion and migration during infection and inflammation. Immunity. 2016;45:172–184. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Emgård J, et al. MAIT cells are major contributors to the cytokine response in group A streptococcal toxic Shock syndrome. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2019;116:25923–25931. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1910883116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Le Bourhis L, et al. Antimicrobial activity of mucosal-associated invariant T cells. Nat. Immunol. 2010;11:701–708. doi: 10.1038/ni.1890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tsai CY, et al. Type I IFNs and IL-18 regulate the antiviral response of primary human γδ T cells against dendritic cells infected with Dengue virus. J. Immunol. 2015;194:3890–3900. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1303343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ussher JE, et al. CD161++ CD8+ T cells, including the MAIT cell subset, are specifically activated by IL-12+IL-18 in a TCR-independent manner. Eur. J. Immunol. 2014;44:195–203. doi: 10.1002/eji.201343509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Luster AD, Alon R, von Andrian UH. Immune cell migration in inflammation: present and future therapeutic targets. Nat. Immunol. 2005;6:1182–1190. doi: 10.1038/ni1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Price JD, et al. Induction of a regulatory phenotype in human CD4+ T cells by streptococcal M protein. J. Immunol. 2005;175:677–684. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.2.677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ozkaya M, et al. The number and activity of CD3(+)TCR Vα7.2(+)CD161(+) cells are increased in children with acute rheumatic fever. Int. J. Cardiol. 2021;333:174–183. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2021.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rivera-Hernandez, T. et al. Vaccine-induced Th1-type response protects against invasive group A Streptococcus infection in the absence of opsonizing antibodies. mBio11, 10.1128/mBio.00122-20 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Most data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article (and its supplementary information files). Any additional data are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request. Source data are provided with this paper.