Abstract

Hepatitis E virus (HEV) is the major cause of enterically transmitted non-A, non-B hepatitis in many developing countries and is also endemic in many industrialized countries. Due to the lack of an effective cell culture system and a practical animal model, the mechanisms of HEV pathogenesis and replication are poorly understood. Our recent identification of swine HEV from pigs affords us an opportunity to systematically study HEV replication and pathogenesis in a swine model. In an early study, we experimentally infected specific-pathogen-free pigs with two strains of HEV: swine HEV and the US-2 strain of human HEV. Eighteen pigs (group 1) were inoculated intravenously with swine HEV, 19 pigs (group 2) were inoculated with the US-2 strain of human HEV, and 17 pigs (group 3) were used as uninoculated controls. The clinical and pathological findings have been previously reported. In this expanded study, we aim to identify the potential extrahepatic sites of HEV replication using the swine model. Two pigs from each group were necropsied at 3, 7, 14, 20, 27, and 55 days postinoculation (DPI). Thirteen different types of tissues and organs were collected from each necropsied animal. Reverse transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR) was used to detect the presence of positive-strand HEV RNA in each tissue collected during necropsy at different DPI. A negative-strand-specific RT-PCR was standardized and used to detect the replicative, negative strand of HEV RNA from tissues that tested positive for the positive-strand RNA. As expected, positive-strand HEV RNA was detected in almost every type of tissue at some time point during the viremic period between 3 and 27 DPI. Positive-strand HEV RNA was still detectable in some tissues in the absence of serum HEV RNA from both swine HEV- and human HEV-inoculated pigs. However, replicative, negative-strand HEV RNA was detected primarily in the small intestines, lymph nodes, colons, and livers. Our results indicate that HEV replicates in tissues other than the liver. The data from this study may have important implications for HEV pathogenesis, xenotransplantation, and the development of an in vitro cell culture system for HEV.

Hepatitis E virus (HEV), the causative agent of hepatitis E, has been recognized as a major cause of enterically transmitted non-A, non-B hepatitis in many developing countries (1, 30, 37, 39). Transmission of the virus occurs primarily by the fecal-oral route through contaminated drinking water in areas with poor sanitation. The disease affects mainly young adults, with a reported mortality rate of up to 25% for pregnant women (10, 14, 37, 39). In the United States, sporadic cases of acute hepatitis E without known risk factors have been documented and anti-HEV antibodies have been detected in a significant proportion of healthy individuals (21, 28, 32, 37, 39, 45). HEV is a positive, single-stranded RNA virus without an envelope. The genome, which is about 7.5 kb in size, contains three open reading frames (ORFs) and a short 5′ and 3′ nontranslated region (13, 18, 31, 38). ORF 1 is the largest of the three and encodes for nonstructural proteins such as methyltransferase, helicase, and RNA-dependent RNA polymerase. ORF 2 encodes the putative capsid protein, and ORF 3, which overlaps with ORF 1 and ORF 2, encodes a cytoskeleton-associated phosphoprotein (13, 37–39, 55). HEV was originally classified in the Caliciviridae family. However, recent studies have demonstrated the unique genomic organization of HEV, and therefore HEV has been declassified and designated “hepatitis E-like viruses” in an unassigned family (3, 18, 35).

In 1997, a novel virus, closely related to human HEV, was discovered in swine (24). This virus, designated swine HEV, was extensively characterized (9, 24–29). In the United States, two strains of human HEV identified from patients with acute hepatitis E (US-1 and US-2) have shown a striking genetic similarity to swine HEV (6, 40). The two U.S. strains of human HEV share ≥97% amino acid identity with swine HEV in ORFs 1 and 2 but are genetically distinct from other known strains of HEV worldwide (26). It has been shown that the US-2 strain of human HEV infects pigs and that swine HEV infects nonhuman primates (9, 26). Similar findings were reported in Taiwan, where a novel strain of swine HEV was isolated from Taiwanese pigs. This Taiwanese strain of swine HEV shared 97.3% nucleotide sequence similarity with a strain of human HEV isolated from a retired Taiwanese farmer, but it is genetically distinct from the U.S. strain of swine HEV and other HEV strains worldwide (12). Numerous genetically distinct strains of human HEV have also been identified in many other industrialized and developing countries (41, 42, 49, 50).

Due to the lack of a practical animal model and an in vitro cell culture system for HEV, the mechanisms of HEV pathogenesis and replication are poorly understood. With the discovery of swine HEV, we now have a homologous animal model system to study HEV infection. It has been suspected that HEV might replicate in tissues and organs other than the liver (2). Recent results from studies performed with rats infected with human HEV have suggested that the virus may replicate extrahepatically (20). The objectives of this study are to utilize swine as a model system to systematically study HEV replication and to identify potential extrahepatic sites of HEV replication.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Viruses.

The swine HEV used in this study was recovered from a pig in Illinois (24). The swine HEV inoculum has an infectious titer of 104.5 50% pig infectious doses per ml of inoculum (26). The US-2 strain of human HEV (kindly provided by Isa Mushahwar of Abbott Laboratories, North Chicago, Ill.) used in this study was first recovered from a hepatitis patient in Tennessee and then transmitted to cynomolgus monkeys (6, 40). The US-2 strain of human HEV has an infectious titer of 105 50% monkey infectious doses per 0.5 ml of inoculum (R. H. Purcell et al., unpublished data).

Experimental infection.

The experimental infection of pigs with swine and human HEV and the clinical and pathological findings from the study have been reported previously (9). Briefly, 54 cross-bred, specific-pathogen-free pigs, 3 to 4 weeks old, were randomly assigned into three groups. Group 1 consisted of 18 pigs who were inoculated intravenously (i.v.) with 104.5 50% pig infectious doses of swine HEV. Group 2 consisted of 19 pigs who were inoculated i.v. with 104.5 monkey infectious doses of the US-2 strain of human HEV. Group 3 consisted of 17 pigs who were used as uninoculated controls. Two pigs from each group were necropsied at 3, 7, 14, 20, 27, and 55 days postinoculation (DPI), respectively. Thirteen different types of tissues and organs were collected from each necropsied animal including liver, mesenteric, tracheobronchial, and hepatic lymph nodes, small intestine, colon, stomach, pancreas, spleen, salivary gland, tonsil, heart, lung, kidney, and skeletal muscle. Samples of tissues and organs were frozen immediately at −80°C until used for analysis.

Tissue homogenates.

Samples of each tissue and organ collected at necropsy were homogenized in 10% (wt/vol) sterile phosphate-buffered saline. Mesenteric, tracheobronchial, and hepatic lymph nodes were pooled and homogenized in 10% phosphate-buffered saline. The tissue homogenates were clarified by centrifugation at 3,000 rpm (Eppendorf centrifuge 5810; Brinkman Instruments Inc., Westbury, N.Y.) for 15 min at 4°C. The supernatants of the tissue homogenates were harvested and stored at −80°C until use.

RNA extraction and RT-PCR.

Total RNA was extracted with TriZol reagent (GIBCO-BRL) from 100 μl of 10% tissue homogenates or serum samples and was resuspended in 11.5 μl of DNase, RNase, and proteinase-free water (Eppendorf, Inc.). Reverse transcription (RT) was performed at 42°C for 60 min with 1 μl of the R1 reverse primer (5′-CTACAGAGCGCCAGCCTTGATTGC-3′), 1 μl of superscript II reverse transcriptase (GIBCO-BRL), 0.5 μl of 0.1 M dithiothreitol, 4 μl of 5× RT buffer, and 1 μl of 10 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphates. Ten microliters of the resulting cDNA was amplified in a 100-μl nested PCR with AmpliTaq gold DNA polymerase (GIBCO-BRL). The PCR parameters included an initial incubation at 95°C for 9 min to activate the AmpliTaq gold DNA polymerase, followed by 39 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 1 min, annealing at 54°C for 1 min, and extension at 72°C for 1.5 min, with a final incubation at 72°C for 7 min. The first round of PCR produced an expected fragment of 404 bp using the forward primer F1 (5′-AGCTCCTGTACCTGATGTTGACTC-3′) and the reverse primer R1. For the second round of PCR, the forward primer F2 (5′-GCTCACGTCATCTGTCGCTGCTGG-3′) and the reverse primer R2 (5′-GGGCTGAACCAAAATCCTGACATC-3′) were used to produce an expected product of 266 bp. The PCR parameters for the nested PCR were essentially the same as those in the first-round PCR. The primers were designed in conserved regions of the ORF 2 to amplify both swine HEV and the US-2 strain of human HEV.

Standardization of a negative-strand-specific RT-PCR. (i) Cloning of an ORF 2 fragment.

To standardize a negative-strand-specific RT-PCR to detect replicative, negative-strand HEV RNA in infected tissues, a negative strand of HEV RNA transcript had to be generated for use as a positive control. Briefly, total RNA was extracted from 100 μl of feces collected from a specific-pathogen-free pig experimentally infected with swine HEV (25). The Qiagen 1-step RT-PCR kit was used to amplify an ORF 2 fragment of swine HEV according to the protocol supplied by the manufacturer. Total RNA was reverse transcribed, and PCR was performed with 10 μl of resulting cDNA in a 100-μl reaction mixture. The PCR was carried out for 31 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 1 min, annealing at 55°C for 1 min, and extension at 72°C for 1.5 min, followed by a final incubation period at 72°C for 7 min. Primers F5526 (5′-GGGGGATCCAGCTCCTGTACCTGATGTTGACTC-3′) and R5955 (5′-GGCCTCGAGCTACAGAGCGCCAGCCTTGATTGC-3′) were used in the RT-PCR. The sense primer F5526 has an introduced BamHI restriction site, and the antisense primer R5955 has an introduced XhoI restriction site (introduced restriction sites underlined) to facilitate the subsequent cloning steps. The resulting PCR product (418 bp) was excised from an agarose gel and purified with the glass milk procedure using the GENE CLEAN II Kit (Bio 101, Inc.). The purified PCR product was first ligated into a TA vector using T4 DNA ligase (Stratagene) at 12°C overnight. The recombinant plasmid was transformed into DH5α-competent Escherichia coli cells (GIBCO-BRL). Plasmids containing the insert were identified and confirmed by restriction enzyme digestions. The insert was subsequently subcloned into PSK II plasmid (Stratagene) by directional cloning using BamHI and XhoI. The recombinant PSK II plasmid containing the ORF 2 fragment was isolated and confirmed by DNA sequencing.

(ii) In vitro transcription of negative-strand HEV RNA.

Recombinant PSK II plasmid containing the ORF 2 fragment of swine HEV was linearized by restriction enzyme digestion with BamHI. Synthetic negative-stranded RNA was transcribed in vitro by activation of the T7 promoter of the PSK II plasmid using Ampliscribe T7 high-yield transcription kit (Epicentre Technologies) according to the manufacturer's protocol. The transcribed negative-strand RNA was separated in a 1.5% agarose gel, and the expected RNA band was excised and purified using the RNaid isolation kit (Bio 101, Inc.) to remove plasmid DNA. The gel-purified RNA was further treated with DNase for 60 min at 37°C. The RNA was then extracted with TriZol reagent, and only the top half of the aqueous layer was collected to further eliminate potential plasmid DNA contamination. A nested PCR with no RT step using AmpliTaq gold DNA polymerase and the external F1 and R1 set of primers and the internal F2 and R2 set of primers was performed to ensure that no plasmid DNA remained in the purified synthetic negative-strand RNA.

Specificity and sensitivity of the negative-strand-specific RT-PCR.

To standardize a negative-strand-specific RT-PCR for HEV, the synthetic negative-strand HEV RNA was serially diluted from 100 ng to 10 ag. Negative-strand-specific RT-PCR was performed on each dilution. RT was performed with the forward primer F1, 1 μl of superscript II reverse transcriptase, 0.5 μl of 0.1 M dithiothreitol, 4 μl of 5× RT buffer, and 1 μl of 10 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphates. A nested PCR with AmpliTaq gold DNA polymerase was subsequently performed with 5 μl of the cDNA in a 50-μl reaction mixture. The first-round PCR used primers F1 and R1 with an expected product of 404 bp. The second-round PCR used 5 μl of the first-round PCR product in a 50-μl reaction mixture with internal primers F2 and R2 with an expected product of 266 bp. For specificity, the negative-strand-specific RT-PCR was performed with RNA extracted from serum samples known to contain positive-stranded HEV RNA.

RESULTS

Tissue distribution of positive-stranded HEV RNA.

All pigs from both HEV-inoculated groups seroconverted to anti-HEV (9). Positive-strand HEV RNA was detected from 3 to 27 DPI in various tissues including livers, lymph nodes, colons, small intestines, stomachs, spleens, kidneys, tonsils, salivary glands, and lungs from pigs inoculated with swine HEV (Table 1). Viral RNA was not detected from tissues collected at 55 DPI. In the absence of viremia, swine HEV RNA was still detectable in tissues from 20 to 27 DPI (Table 1). Swine HEV viremia disappeared after 14 DPI, and positive-strand viral RNA was not detectable from 20 to 55 DPI in the sera of swine HEV-inoculated pigs.

TABLE 1.

Detection of positive-strand HEV RNA in pigs inoculated with swine HEV and the US-2 strain of human HEV

| Tissue | No. of necropsied pigs (of 2 at each DPI) testing positive for positive-strand HEV RNA in indicated tissue at DPI:

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 7 | 14 | 20 | 27 | 55 | |

| Swine HEV-inoculated pig | ||||||

| Serum | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Liver | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| Lymph nodesa | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| Colon | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 |

| Small intestine | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Stomach | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Spleen | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Pancreas | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Kidney | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Tonsil | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Salivary gland | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Lung | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Heart | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Muscle | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Human HEV-inoculated pig | ||||||

| Serum | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Liver | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| Lymph node | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| Colon | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Small intestine | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Stomach | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Spleen | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 |

| Pancreas | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Kidney | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Tonsil | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Salivary gland | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Lung | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Heart | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Muscle | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Lymph nodes, pool of mesenteric, tracheobronchial, and hepatic lymph nodes.

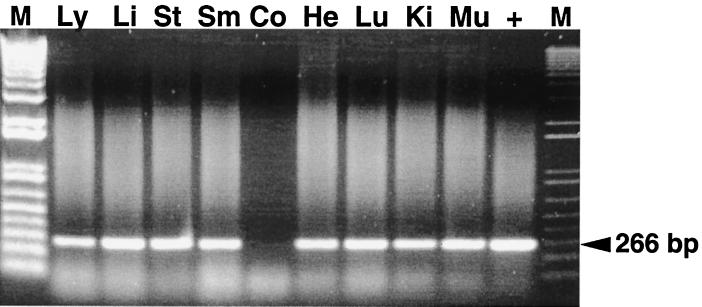

In pigs inoculated with the US-2 strain of human HEV, viral RNA was detected in numerous tissues from 3 to 27 DPI (Fig. 1) (Table 1). The tissue distribution of positive-strand viral RNA is similar to that in swine HEV-inoculated pigs. Positive strand HEV RNA was not detected in the sera of pigs from 27 through 55 DPI. Again in the absence of viremia at 27 DPI, positive-strand viral RNA was still detectable in a number of tissues (Table 1).

FIG. 1.

RT-PCR for detection of positive-strand HEV RNA in selected tissue samples from pigs inoculated with human HEV and necropsied at 3 and 7 DPI. M, 1-kb-plus ladder; Ly, lymph nodes; Li, liver; St, stomach; Sm, small intestine; Co, colon; He, Heart; Lu, lung; Ki, kidney; Mu, skeletal muscle; +, positive control. The expected PCR product is indicated.

All control pigs in group 1 remained seronegative for anti-HEV throughout the study. Therefore, RT-PCR was not performed on the seronegative control animals.

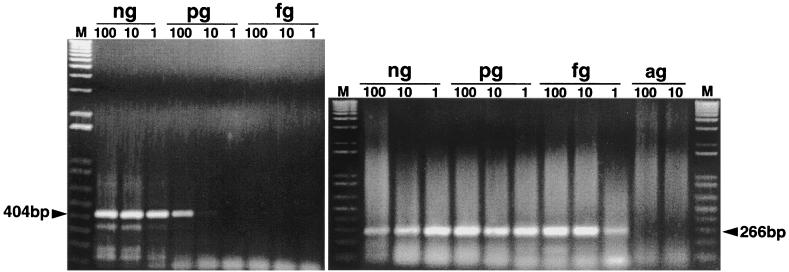

Standardization of the negative-strand-specific RT-PCR.

The negative-strand-specific RT-PCR for HEV was standardized with the synthetic negative-strand HEV RNA transcript. By using the synthetic negative-strand RNA as a positive control, we showed that the test can detect negative-strand HEV RNA to the dilution level of 10 pg in the first round of the PCR and 1 fg in the second round of the nested PCR (Fig. 2). The dilution level of 1 fg correlates to approximately 4,500 viral genome copies. The negative-strand RT-PCR is specific as it fails to detect positive-strand viral RNA from positive serum samples that contain only positive-strand HEV RNA.

FIG. 2.

Standardization of negative-strand-specific RT-PCR using synthetic HEV RNA transcript. The synthetic negative-strand HEV RNA was serially diluted and tested by nested PCR. The expected PCR products in the first and second rounds are indicated. M, 1-kb-plus ladder.

Evidence for extrahepatic replication of HEV.

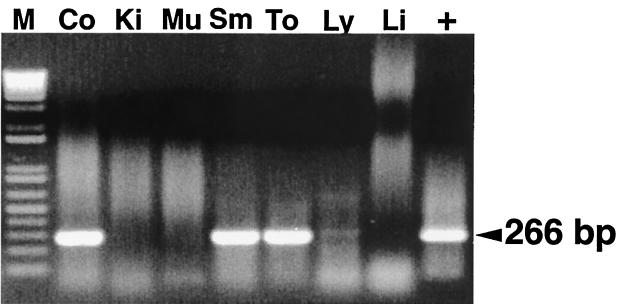

Detection of positive-strand HEV RNA in various tissues of inoculated pigs does not mean that HEV replicates in these sites. Therefore, a negative-strand-specific RT-PCR was performed to retest all the tissues that had tested positive for positive-strand HEV RNA in the traditional RT-PCR. For swine HEV-inoculated pigs, replicative, negative-strand viral RNA was detected in the livers, lymph nodes, colons, small intestines, and spleens between 7 and 27 DPI (Table 2). For pigs inoculated with the US-2 strain of human HEV, negative-strand HEV RNA was detected in the livers, lymph nodes, colons, small intestines, stomachs, spleens, kidneys, tonsils, and salivary glands between 3 and 27 DPI (Fig. 3) (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Detection of replicative, negative strand of HEV RNA in pigs inoculated with swine HEV and the US-2 strain of human HEV

| Tissue | No. of necropsied pigs (of 2) testing positive for negative-strand HEV RNA in indicated tissue at DPI

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 7 | 14 | 20 | 27 | 55 | |

| Swine HEV-inoculated pig | ||||||

| Liver | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | NT |

| Lymph nodesa | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | NT |

| Colon | NTb | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | NT |

| Small intestine | NT | 1 | 2 | 0 | NT | NT |

| Stomach | NT | 0 | 0 | NT | NT | NT |

| Spleen | NT | 0 | 0 | 1 | NT | NT |

| Pancreas | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT |

| Kidney | NT | NT | NT | NT | 0 | NT |

| Tonsil | NT | NT | NT | NT | 0 | NT |

| Salivary gland | NT | NT | NT | NT | 0 | NT |

| Lung | NT | 0 | 0 | NT | NT | NT |

| Heart | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT |

| Muscle | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT |

| Human HEV-inoculated pig | ||||||

| Liver | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | NT |

| Lymph node | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | NT |

| Colon | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | NT |

| Small intestine | 1 | 2 | NT | NT | NT | NT |

| Stomach | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | NT |

| Spleen | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | NT |

| Pancreas | 0 | NT | NT | 0 | NT | NT |

| Kidney | 0 | 1 | NT | NT | NT | NT |

| Tonsil | 1 | NT | 1 | 0 | 0 | NT |

| Salivary gland | NT | 1 | 0 | NT | NT | NT |

| Lung | 0 | NT | 0 | NT | NT | NT |

| Heart | 0 | 0 | NT | NT | NT | NT |

| Muscle | 0 | 0 | 0 | NT | NT | NT |

Lymph nodes, pool of mesenteric, tracheobronchial, and hepatic lymph nodes.

NT, these samples are not tested by the negative-strand RT-PCR since they were negative by the positive-strand RT-PCR (Table 1).

FIG. 3.

RT-PCR for detection of the replicative, negative strand of HEV RNA in selected tissue samples from a pig inoculated with human HEV and necropsied at 3 DPI. M, 1-kb-plus ladder; Co, colon; Ki, kidney; Mu, muscle; Sm, small intestine; To, tonsil; Ly, lymph nodes; Li, liver; +, positive control.

DISCUSSION

The first animal strain of HEV, swine HEV, was genetically identified and characterized from a pig in the United States (24). Subsequently, several other strains of swine HEV were identified from pigs in Taiwan (12, 53). In Spain, strains of HEV from patients with acute hepatitis E were found to have a 92 to 94% nucleotide sequence identity with a strain of HEV recovered from slaughterhouse sewage which was primarily of swine origin (34). A variant strain of HEV has also been recovered from tissues and fecal samples of rodents trapped in the wild in Nepal. Phylogenetic analysis revealed that the HEV strain recovered from these rodents is most closely related to human strains of HEV from hepatitis patients in Nepal (48).

Serological studies also support the theory of an animal reservoir(s) for HEV. Anti-HEV antibodies have been identified in pigs from industrialized countries such as the United States (25), Canada (27), Korea (27), Taiwan (12, 52, 53), and Australia (4). Anti-HEV antibodies have also been detected in pigs from regions where HEV is endemic, such as Nepal, China, and Thailand (5, 27). In addition to pigs, 77% of rats in Maryland and 90% of rats in Hawaii are positive for anti-HEV antibodies (17). The prevalence of antibodies in rats occurs in both urban and rural areas and increases in proportion to the estimated ages of the animals (8, 17). Anti-HEV antibodies were also detected in rhesus monkeys caught in the wild (47). In Vietnam, where HEV is endemic, anti-HEV antibodies have been detected in 44% of chickens, 36% of pigs, and 27% of dogs (46). Approximately 42 to 67% of sheep and goats have tested positive for anti-HEV antibodies in Turkmenistan, where HEV is also endemic (7). In the United States, anti-HEV antibodies have been detected in about 1 to 2% of blood donors, with up to 20% detected in areas such as Baltimore, Md. (21, 22, 32, 45). Similar results have been reported in other industrialized countries such as The Netherlands (54), Italy (56), Greece (36), England (23, 30), Spain (15), Germany (19), Sweden (16), Finland (30), and Taiwan (11, 33, 52). Although the sensitivity and specificity of these various serological tests are unknown, these results suggest that the prevalence of HEV infection may be underestimated, especially in industrialized countries, and that hepatitis E may be a zoonosis.

The lack of a practical animal model has hindered HEV research. The identification of swine HEV in pigs affords us an opportunity to study HEV pathogenesis and replication in a swine model. The U.S. strain of swine HEV has shown the ability to infect nonhuman primates (26). In an earlier report, we showed that pigs could be experimentally infected with both swine HEV and the US-2 strain of human HEV (9). The clinical and pathological findings of HEV infection in pigs were reported previously (9). In the present study, we attempted to use the samples of tissues and organs collected from this previous study to identify the potential extrahepatic sites of HEV replication.

It has been hypothesized that liver damage induced by HEV infection may be due to the immune response to the invading virus and may not be a direct cause of viral replication in hepatocytes (37). Since HEV is presumably transmitted by the fecal-oral route, it is unclear how the virus reaches the liver, and an extrahepatic site(s) of replication would be a possible explanation (2, 37). Primary hepatocytes are the only known sites of HEV replication (43, 44). In a preliminary study with naturally infected pigs, we found that positive-strand HEV RNA was detectable in a number of tissues, even after viremia was cleared (X. J. Meng et al., unpublished data). Furthermore, in experimentally infected pigs, we also found that the relative genomic titer of HEV in the feces was at least 10-fold higher than that in bile collected on the same and prior days (Meng et al., unpublished), suggesting that HEV may replicate in the gastrointestinal tract.

In this study, we first tested by RT-PCR for the presence of positive-strand HEV RNA from various tissues and organs of both swine HEV- and human HEV-infected pigs. We showed that positive-strand HEV RNA was detectable in numerous tissues. The positive-strand viral RNA detected in tissues from 3 to 14 DPI in swine HEV-inoculated pigs and from 3 to 20 DPI in human HEV-inoculated pigs may not be attributable to the replicating virus, since viral RNA was also detected in the sera. However, after viremia disappeared, positive-strand viral RNA was still detectable in various tissues between 20 to 27 DPI in swine HEV-infected pigs and at 27 DPI in human HEV-infected pigs. Detection of positive-strand HEV RNA from various tissues and organs in the absence of detectable serum viral RNA indicated that the virus detected from these tissues represents replicating virus and is not due to contamination of the tissue samples by virus circulating in the blood.

HEV is a positive-strand RNA virus, and therefore HEV replication produces an intermediate, negative-strand RNA. To further confirm that the HEV RNAs detected in extrahepatic tissues are due to HEV replication, we retested by the negative-strand-specific RT-PCR assay all tissues that were positive for the positive-strand viral RNA. The negative-strand RT-PCR was standardized to detect only the replicative, negative-strand HEV RNA in infected tissues. We showed that the negative-strand-specific RT-PCR is sensitive and specific for the replicative, negative-strand HEV RNA. Our results indicate that extrahepatic replication of HEV does occur. We were able to detect negative-strand HEV RNA in a variety of extrahepatic tissues. It appears that pigs inoculated with the US-2 strain of HEV had positive results in more tissues than did pigs inoculated with swine HEV. No replicating virus was detected in the kidney, stomach, pancreas, lung, heart, muscle, salivary gland, or tonsil tissues of pigs inoculated with swine HEV. Similarly, negative-strand HEV RNA was also absent in pancreas, lung, heart, and muscle tissues from human HEV-inoculated pigs. The detection of replicating virus primarily in small intestine and colon tissues supports our earlier preliminary observations that the feces contain more virus than bile does.

For human HEV-infected pigs, HEV replication was found in tonsil, small intestine, and colon tissues as early as 3 DPI. For swine HEV-infected pigs, replicative viral RNA was first detected in small intestines, colons, lymph nodes, and livers. Both swine HEV and human HEV replicate for a longer time in liver, lymph node, small intestine, and colon tissues than in other tissues. Other extrahepatic tissues such as kidney, tonsil, and salivary gland had detectable replicative HEV RNA for only 1 or 2 weeks. It appears that lymph nodes and the intestinal tract are the main extrahepatic sites of replication. The i.v. route of inoculation used in this study prevents us from identifying the initial site of HEV infection, since the natural route of HEV infection is presumably fecal-oral. Our earlier studies showed that a much higher infectious titer of HEV is required to initiate an infection by the oral route of inoculation (C. Kasorndorkbua et al., unpublished data). The i.v. route of inoculation has been almost exclusively used in animal experiments with HEV and the hepatitis A virus.

The significance of identifying extrahepatic sites of HEV replication is unclear at this time. Since we demonstrated that tissues other than the liver support HEV replication, this could help identify an in vitro cell culture system to propagate HEV. Extrahepatic replication of HEV also raises additional concerns involving xenotransplantation with pig organs. Xenotransplantation is a potential solution for the shortage of human organs for transplantation. Pigs have been identified as favorable organ donors because they have anatomic and metabolic characteristics similar to those of humans (51). The possibility of transmission of swine HEV to immunosuppressed xenograft recipients has been a concern, especially in situations that would involve liver transplants. The findings from this study indicate that xenotransplantation with other organs may also pose potential risk for HEV xenozoonosis. In addition, damages to these extrahepatic tissues and organs resulting from HEV infection may render them useless for xenotransplantation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Prem Paul for technical advice and use of laboratory equipment, Amy Weaver and Crystal Gilbert for assistance with the RT-PCR testing, Robert Purcell and Suzanne U. Emerson of the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Md., for providing HEV inocula and supporting the study, and Roger Avery of Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University College of Veterinary Medicine for his support.

This study was supported by grants (to X.J.M.) from the National Institutes of Health (AI01653 and AI46505) and in part by grants (to P.G.H.) from the National Pork Producers Council and the Healthy Livestock Initiatives.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arankalle V A, Chada M S, Tsarev S A, Emerson S U, Risbud A R, Banerjee K, Purcell R H. Seroepidemiology of water-born hepatitis in India and evidence for a third enterically transmitted hepatitis agent. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:3428–3432. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.8.3428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Balayan M S. Hepatitis E virus infection in Europe: regional situation regarding laboratory diagnosis and epidemiology. Clin Diagn Virol. 1993;1:1–9. doi: 10.1016/0928-0197(93)90027-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berke T, Matson D O. Reclassification of the Caliciviridae into distinct genera and exclusion of hepatitis E virus from the family on the basis of comparative phylogenetic analysis. Arch Virol. 2000;145:1421–1436. doi: 10.1007/s007050070099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chandler J D, Riddell M A, Li F, Love R J, Anderson D A. Serological evidence for swine hepatitis E virus infection in Australian pig herds. Vet Microbiol. 1999;68:95–105. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1135(99)00065-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clayson E T, Innis B L, Myint K S, Narupiti S, Vaughn D W, Giri S, Ranabhat P, Shrestha M P. Detection of hepatitis E virus infections among domestic swine in the Katmandu Valley of Nepal. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1995;53:228–232. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1995.53.228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Erker J C, Desai S M, Schlauder G G, Dawson G J, Mushahwar I K. A hepatitis E virus variant from the United States: molecular characterization and transmission in cynomolgus macaques. J Gen Virol. 1999;80:681–690. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-80-3-681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Favorov M O, Nazarova O, Margolis H S. Is hepatitis E an emerging zoonotic disease? Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1998;59:242. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Favorov M O, Kosoy M Y, Tsarev S A, Childs J E, Margolis H S. Prevalence of antibody to hepatitis E virus among rodents in the United States. J Infect Dis. 2000;181:449–455. doi: 10.1086/315273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Halbur P G, Kasorndorkbua C, Gilbert C, Guenette D, Potters M B, Purcell R H, Emerson S U, Toth T E, Meng X J. Comparative pathogenesis of infection of pigs with hepatitis E virus recovered from a pig and a human. J Clin Microbiol. 2001;39:918–923. doi: 10.1128/JCM.39.3.918-923.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hamid S S, Jafri S M, Khan H, Shah H, Abbas H, Fields Z. Fulminant hepatic failure in pregnant women: acute fatty liver or acute viral hepatitis? Hepatology. 1996;25:20–27. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(96)80323-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hsieh S Y, Yang P Y, Ho Y P, Chu C M, Liaw Y F. Identification of a novel strain of hepatitis E virus responsible for sporadic acute hepatitis in Taiwan. J Med Virol. 1998;55:300–304. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9071(199808)55:4<300::aid-jmv8>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hsieh S Y, Meng X J, Wu Y H, Liu S, Tam A W, Lin D, Liaw Y F. Identity of a novel swine hepatitis E virus in Taiwan forming a monophyletic group with Taiwan isolates of human hepatitis E virus. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:3828–3834. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.12.3828-3834.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang C C, Nguyen D, Fernandez J, Yun K Y, Fry K E, Bradley D W, Tam A W, Reyes G R. Molecular cloning and sequencing of the Mexico isolate of hepatitis E virus (HEV) Virology. 1992;191:550–558. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(92)90230-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hussaini S H, Skidmore S J, Richardson P, Sherratt L M, Cooper B T, O'Grady J G. Severe hepatitis E infection during pregnancy. J Viral Hepat. 1997;4:51–54. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2893.1997.00123.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jardi R, Buti M, Rodriguez-Frias F, Esteban R. Hepatitis E infection in acute sporadic hepatitis in Spain. Lancet. 1993;341:1355–1356. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)90874-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johansson P J, Mushahwar I K, Norkrans G, Weiland O, Nordenfelt E. Hepatitis E virus infection in patients with acute, non A-D in Sweden. Scand J Infect Dis. 1995;27:543–546. doi: 10.3109/00365549509047064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kabrane-Lazizi Y, Fine J B, Elm J, Glass G E, Higa H, Diwan A, Gibbs C J, Meng X J, Emerson S U, Purcell R H. Evidence for widespread infection of wild rats with the hepatitis E virus in the United States. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1999;61:331–335. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1999.61.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kabrane-Lazizi Y, Meng X J, Purcell R H, Emerson S U. Evidence that the genomic RNA of hepatitis E virus is capped. J Virol. 1999;73:8848–8850. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.10.8848-8850.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Langer B C A, Frosner G G. Relative importance of the enterically transmitted human hepatitis viruses A and E as a cause of foreign travel associated hepatitis. Arch Virol. 1996;11(Suppl.):171–179. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-7482-1_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maneerat Y, Clayson E T, Myint K S, Young G D, Innis B L. Experimental infection of the laboratory rat with the hepatitis E virus. J Med Virol. 1996;48:121–128. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9071(199602)48:2<121::AID-JMV1>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mast E E, Kuramoto I K, Favorov M O, Schoening V R, Burkholder B T, Shapiro C N. Prevalence of and risk factors for antibody to hepatitis E virus seroactivity among blood donors in Northern California. J Infect Dis. 1997;176:34–40. doi: 10.1086/514037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mast E E, Alter M J, Holland P V, Purcell R H. Evolution of assays for antibody to hepatitis E virus by a serum panel. Hepatology. 1998;27:857–861. doi: 10.1002/hep.510270331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McCrudden R, O'Connell S, Farrant T, Beaton S, Iredale J P, Fine D. Sporadic acute hepatitis E in the United Kingdom: an underdiagnosed phenomenon? Gut. 2000;46:732–733. doi: 10.1136/gut.46.5.732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meng X J, Purcell R H, Halbur P G, Lehman J R, Webb D M, Tsareva T S, Haynes J S, Thaker B J, Emerson S U. A novel virus in swine is closely related to the human hepatitis E virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:9860–9865. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.18.9860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meng X J, Halbur P G, Haynes J S, Tsareva T S, Bruna J D, Royer R L, Purcell R H, Emerson S U. Experimental infection of pigs with the newly identified swine hepatitis E virus (swine HEV), but not with human strains of HEV. Arch Virol. 1998;143:1405–1415. doi: 10.1007/s007050050384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meng X J, Halbur P G, Shapiro M S, Govindarajan S, Bruna J D, Mushahwar I K, Purcell R H, Emerson S U. Genetic and experimental evidence for cross-species infection by swine hepatitis E virus. J Virol. 1998;72:9714–9721. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.12.9714-9721.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meng X J, Dea S, Engle R E, Friendship R, Lyoo Y S, Sirinarumitr T, Urairong K, Wang D, Wong D, Yoo D, Zhang Y, Purcell R H, Emerson S U. Prevalence of antibodies to the hepatitis E virus in pigs from countries where hepatitis E is common or is rare in the human population. J Med Virol. 1999;59:297–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Meng X J. Novel strains of hepatitis E virus identified from humans and other animal species: is hepatitis E a zoonosis? J Hepatol. 2000;33:842–845. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(00)80319-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meng X J. Zoonotic and xenozoonotic risks of the hepatitis E virus. Infect Dis Rev. 2000;2:35–41. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mushahwar I K, Dawson G J. Hepatitis E virus: epidemiology, molecular biology and diagnosis. In: Harrison T J, Zuckerman A J, editors. The molecular medicine of viral hepatitis. New York, N.Y: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 1997. pp. 33–43. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Panda S K, Ansari I H, Durgapal H, Agrawal S, Jameel S. The in vitro-synthesized RNA from a cDNA clone of hepatitis E virus is infectious. J Virol. 2000;74:2430–2437. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.5.2430-2437.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Paul D A, Knigge M F, Ritter A, Gutierrez R, Pilot-Matias T, Chau K H, Dawson G J. Determination of hepatitis E virus seroprevalence by using recombinant fusion protein and synthetic peptides. J Infect Dis. 1994;169:801–806. doi: 10.1093/infdis/169.4.801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Peng C F, Lin M R, Chue P Y, Tsai J F, Shih C H, Chen I L. Prevalence of antibody to hepatitis E virus among healthy individuals in southern Taiwan. Microbiol Immunol. 1995;39:733–736. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1995.tb03250.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pina S, Buti M, Cotrina M, Piella J, Girones R. HEV identified in serum from humans with acute hepatitis and in sewage of animal origin in Spain. J Hepatol. 2000;33:826–833. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(00)80316-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pringle C R. Virus taxonomy—San Diego 1998. Arch Virol. 1998;143:1449–1459. doi: 10.1007/s007050050389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Psichogiou M, Vaindirili E, Tzala E, Voudiclari S, Boletis J, Vosnidis G, Moutafis S, Skoutelis G, Hadjiconstantinou V, Troonen H, Hatzakis A. Hepatitis E virus (HEV) infection in haemodialysis patients. The multicentre haemodialysis cohort study in viral hepatitis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1996;11:1093–1095. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Purcell R H. Hepatitis E virus. In: Fields B N, Knipe D M, Howley P M, editors. Fields virology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott-Raven Publishers; 1996. pp. 2831–2843. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reyes G R, Purdey M A, Kim J P, Luk K C, Young L M, Fry K E, Bradley D W. Isolation of a cDNA from the virus responsible for the enterically transmitted non-A, non-B hepatitis. Science. 1990;247:1335–1339. doi: 10.1126/science.2107574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Reyes G R. Overview of the epidemiology and biology of the hepatitis E virus. In: Willsen R A, editor. Viral hepatitis. New York, N.Y: Marcel Dekker, Inc; 1997. pp. 239–258. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schlauder G G, Dawson G J, Erker J C, Kwo P Y, Knigge M F, Smalley D L, Rosenblatt D L, Desai S M, Mushahwar I K. The sequence and phylogenetic analysis of a novel hepatitis E virus isolated from a patient with acute hepatitis reported in the United States. J Gen Virol. 1998;79:447–456. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-79-3-447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schlauder G G, Desai S M, Zanetti A R, Tassopoulos N C, Mushahwar I K. Novel hepatitis E virus (HEV) isolates from Europe: evidence for additional genotypes of HEV. J Med Virol. 1999;57:243–251. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9071(199903)57:3<243::aid-jmv6>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schlauder G G, Frider B, Sookoian S, Castano G C, Mushahwar I K. Identification of 2 novel isolates of hepatitis E virus in Argentina. J Infect Dis. 2000;182:294–297. doi: 10.1086/315651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tam A W, White R, Reed E, Short M, Zhang Y, Fuerst T R, Lanford R E. In vitro propagation and production of hepatitis E virus from in vivo-infected primary macaque hepatocytes. Virology. 1996;215:1–9. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tam A W, White R, Yarbough P O, Murphy B J, McAtee C P, Lanford R E, Fuerst T R. In vitro infection and replication of the hepatitis E virus in primary cynomolgus macaque hepatocytes. Virology. 1997;238:94–102. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Thomas D L, Yarbough P O, Vlahov D, Tsarev S A, Nelson K E, Saah A J, Purcell R H. In vitro infection and replication of the hepatitis E virus in primary cynomolgus macaque hepatocytes. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:1244–1247. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.5.1244-1247.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tien N T, Clayson H T, Khiem H B, Sac P K, Corwin A L, Myint K S. Detection of immunoglobulin G to the hepatitis E virus among several animal species in Vietnam. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1997;57:211. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tsarev S A, Tsareva T S, Emerson S U, Rippy M K, Zack P, Shapiro M, Purcell R H. Experimental hepatitis E in pregnant rhesus monkeys: failure to transmit hepatitis E virus (HEV) to offspring and evidence of naturally acquired antibodies to HEV. J Infect Dis. 1995;172:31–37. doi: 10.1093/infdis/172.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tsarev S A, Shrestha M P, He J, Scott R M, Vaughn D W, Clayson E T. Naturally acquired hepatitis E virus (HEV) infection in Nepalese rodents. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1998;59:242. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang Y, Ling R, Erker J C, Zhang H, Li H, Desai S, Mushahwar I K, Harrison T J. A divergent genotype of the hepatitis E virus in Chinese patients with acute hepatitis. J Gen Virol. 1999;80:169–177. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-80-1-169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang Y, Zhang H, Ling R, Li H, Harrison T J. The complete sequence of the hepatitis E virus genotype 4 reveals an alternate strategy for translation of open reading frames 2 and 3. J Gen Virol. 2000;81:1675–1686. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-81-7-1675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Weiss R A. Transgenic pigs and virus adaptation. Nature. 1998;391:327–328. doi: 10.1038/34772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wu J C, Sheen I J, Chiang T Y, Sheng W Y, Wang Y J, Chan C Y, Lee S D. The impact of traveling to endemic areas on the spread of hepatitis E virus infection: epidemiological and molecular analysis. Hepatology. 1998;27:1415–1420. doi: 10.1002/hep.510270532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wu J C, Chen C M, Chiang T Y, Sheen I J, Chen J Y, Tsai W H, Huang Y H, Lee S D. Clinical and epidemiological implications of swine hepatitis E virus infection. J Med Virol. 2000;60:166–171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zaaijer H L, Mauser-Bunschoten E P, Ten Veen J H, Kapprell H P, Kok M, Van den Berg H M. Hepatitis E virus antibodies among patients with hemophilia, blood donors, and hepatitis patients. J Med Virol. 1995;46:244–246. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890460313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zafrullah M, Ozdener M H, Panda S K, Jameel S. The ORF 3 protein of hepatitis E virus is a phosphoprotein that associates with the cytoskeleton. J Virol. 1997;71:9045–9053. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.12.9045-9053.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zanetti A R, Dawson G J. Hepatitis type E in Italy: a seroepidemiological survey. Study group of hepatitis E. J Med Virol. 1994;42:318–320. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890420321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]