Abstract

Background

Diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) is an acute, life‐threatening complication of uncontrolled diabetes that mainly occurs in individuals with autoimmune type 1 diabetes, but it is not uncommon in some people with type 2 diabetes. The treatment of DKA is traditionally accomplished by the administration of intravenous infusion of regular insulin that is initiated in the emergency department and continued in an intensive care unit or a high‐dependency unit environment. It is unclear whether people with DKA should be treated with other treatment modalities such as subcutaneous rapid‐acting insulin analogues.

Objectives

To assess the effects of subcutaneous rapid‐acting insulin analogues for the treatment of diabetic ketoacidosis.

Search methods

We identified eligible trials by searching MEDLINE, PubMed, EMBASE, LILACS, CINAHL, and the Cochrane Library. We searched the trials registers WHO ICTRP Search Portal and ClinicalTrials.gov. The date of last search for all databases was 27 October 2015. We also examined reference lists of included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and systematic reviews, and contacted trial authors.

Selection criteria

We included trials if they were RCTs comparing subcutaneous rapid‐acting insulin analogues versus standard intravenous infusion in participants with DKA of any age or sex with type 1 or type 2 diabetes, and in pregnant women.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently extracted data, assessed studies for risk of bias, and evaluated overall study quality utilising the GRADE instrument. We assessed the statistical heterogeneity of included studies by visually inspecting forest plots and quantifying the diversity using the I² statistic. We synthesised data using random‐effects model meta‐analysis or descriptive analysis, as appropriate.

Main results

Five trials randomised 201 participants (110 participants to subcutaneous rapid‐acting insulin analogues and 91 to intravenous regular insulin). The criteria for DKA were consistent with the American Diabetes Association criteria for mild or moderate DKA. The underlying cause of DKA was mostly poor compliance with diabetes therapy. Most trials did not report on type of diabetes. Younger diabetic participants and children were underrepresented in our included trials (one trial only). Four trials evaluated the effects of the rapid‐acting insulin analogue lispro, and one the effects of the rapid‐acting insulin analogue aspart. The mean follow‐up period as measured by mean hospital stay ranged between two and seven days. Overall, risk of bias of the evaluated trials was unclear in many domains and high for performance bias for the outcome measure time to resolution of DKA.

No deaths were reported in the included trials (186 participants; 3 trials; moderate‐ (insulin lispro) to low‐quality evidence (insulin aspart)). There was very low‐quality evidence to evaluate the effects of subcutaneous insulin lispro versus intravenous regular insulin on the time to resolution of DKA: mean difference (MD) 0.2 h (95% CI ‐1.7 to 2.1); P = 0.81; 90 participants; 2 trials. In one trial involving children with DKA, the time to reach a glucose level of 250 mg/dL was similar between insulin lispro and intravenous regular insulin. There was very low‐quality evidence to evaluate the effects of subcutaneous insulin aspart versus intravenous regular insulin on the time to resolution of DKA: MD ‐1 h (95% CI ‐3.2 to 1.2); P = 0.36; 30 participants; 1 trial. There was low‐quality evidence to evaluate the effects of subcutaneous rapid‐acting insulin analogues versus intravenous regular insulin on hypoglycaemic episodes: 6 of 80 insulin lispro‐treated participants compared with 9 of 76 regular insulin‐treated participants reported hypoglycaemic events; risk ratio (RR) 0.59 (95% CI 0.23 to 1.52); P = 0.28; 156 participants; 4 trials. For insulin aspart compared with regular insulin, RR for hypoglycaemic episodes was 1.00 (95% CI 0.07 to 14.55); P = 1.0; 30 participants; 1 trial; low‐quality evidence. Socioeconomic effects as measured by length of mean hospital stay for insulin lispro compared with regular insulin showed a MD of ‐0.4 days (95% CI ‐1 to 0.2); P = 0.22; 90 participants; 2 trials; low‐quality evidence and for insulin aspart compared with regular insulin 1.1 days (95% CI ‐3.3 to 1.1); P = 0.32; low‐quality evidence. Data on morbidity were limited, but no specific events were reported for the comparison of insulin lispro with regular insulin. No trial reported on adverse events other than hypoglycaemic episodes, and no trial investigated patient satisfaction.

Authors' conclusions

Our review, which provided mainly data on adults, suggests on the basis of mostly low‐ to very low‐quality evidence that there are neither advantages nor disadvantages when comparing the effects of subcutaneous rapid‐acting insulin analogues versus intravenous regular insulin for treating mild or moderate DKA.

Keywords: Adult; Child; Humans; Young Adult; Diabetic Ketoacidosis; Diabetic Ketoacidosis/drug therapy; Hypoglycemic Agents; Hypoglycemic Agents/adverse effects; Hypoglycemic Agents/therapeutic use; Injections, Subcutaneous; Insulin; Insulin/therapeutic use; Insulin Aspart; Insulin Aspart/therapeutic use; Insulin Lispro; Insulin Lispro/therapeutic use; Insulin, Short‐Acting; Insulin, Short‐Acting/adverse effects; Insulin, Short‐Acting/therapeutic use; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic

Plain language summary

Subcutaneous rapid‐acting insulin analogues for diabetic ketoacidosis

Review question

What are the effects of subcutaneous rapid‐acting insulin analogues compared with standard intravenous infusion of regular insulin for the treatment of diabetic ketoacidosis?

Background

Rapid‐acting insulin analogues (artificial insulin such as insulin lispro, insulin aspart, or insulin glulisine) act more quickly than regular human insulin. In people with a specific type of life‐threatening diabetic coma due to uncontrolled diabetes, called diabetic ketoacidosis, prompt administration of intravenous regular insulin is standard therapy. The rapid‐acting insulin analogues, if injected subcutaneously, act faster than subcutaneously administered regular insulin. The need for a continuous intravenous infusion, an intervention that usually requires admission to an intensive care unit, can thereby be avoided. This means that subcutaneously given insulin analogues for diabetic ketoacidosis might be applied in the emergency department and a general medicine ward.

Study characteristics

We found five randomised controlled trials (clinical studies where people are randomly put into one of two or more treatment groups) with a total of 201 participants. Most trials did not report on type of diabetes. Younger diabetic participants and children were underrepresented in our included trials (one trial only). Participants in four trials received treatment with insulin lispro, and one trial with 45 participants investigated insulin aspart. The average follow‐up as measured by mean hospital stay ranged between two and seven days. The study authors termed the diabetic ketoacidosis being treated with insulin analogues or regular insulin as mild or moderate. This evidence is up to date as of October 2015.

Key results

Our results are most relevant for adults with mild or moderate diabetic ketoacidosis due to undertreatment of diabetes. No deaths occurred. Time to resolution of diabetic ketoacidosis from the start of therapy did not differ substantially between the two insulin treatment schemes (approximately 11 hours). Hypoglycaemic (low blood sugar) episodes were comparable: 118 per 1000 participants for intravenous insulin compared with 70 per 1000 participants for subcutaneous insulin lispro (no statistically significant difference). The mean length of hospital stay also showed no marked differences. No trial reported on side effects other than hypoglycaemic episodes or investigated patient satisfaction. No serious events associated with diabetic ketoacidosis were seen during insulin lispro treatment.

Quality of the evidence

Our results were limited by mostly low‐ to very low‐quality evidence, mainly because the number of included trials and participants was low. Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our findings.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Subcutaneous insulin lispro versus intravenous regular insulin for diabetic ketoacidosis.

| Subcutaneous insulin lispro versus intravenous regular insulin for diabetic ketoacidosis | ||||||

| Patient: participants with diabetic ketoacidosis Settings: emergency department and critical care unit Intervention: subcutaneous insulin lispro versus intravenous regular insulin | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Intravenous regular insulin | Subcutaneous insulin lispro | |||||

|

All‐cause mortality (N) Mean hospital stay: 2‐7 days |

See comment | See comment | Not estimable | 156 (4) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderatea | No deaths reported |

|

Hypoglycaemic episodes (N) Mean hospital stay: 2‐7 days |

118 per 1000 | 70 per 1000 (27 to 180) | RR 0.59 (0.23 to 1.52) | 156 (4) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowb | Comparable risk ratios for adults (4 trials) and children (1 trial) |

|

Morbidity (N) Mean hospital stay: 2‐7 days |

See comment | See comment | Not estimable | 96 (2) | See comment | No cases of cerebral oedema, venous thrombosis, adult respiratory distress syndrome, hyperchloraemic acidosis |

| Adverse events other than hypoglycaemic episodes | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | See comment | See comment | Not investigated |

|

Time to resolution of diabetic ketoacidosis (h) Mean hospital stay: 2‐4 days |

The mean time to resolution of diabetic ketoacidosis across the intravenous regular insulin groups was 11 h | The mean time to resolution of diabetic ketoacidosis in the subcutaneous insulin lispro groups was 0.2 h higher (1.7 h lower to 2.1 h higher) | ‐ | 90 (2) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very lowc | Metabolic acidosis and ketosis took longer to resolve in the subcutaneous insulin lispro group in 1 trial (60 children); no exact data published |

| Patient satisfaction | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | See comment | See comment | Not investigated |

|

Socioeconomic effects: length of hospital stay (days) Mean hospital stay: 4‐7 days |

The mean length of hospital stay in the intravenous regular insulin groups ranged between 4 and 6.6 days | The mean length of hospital stay in the subcutaneous insulin lispro groups was 0.4 days shorter (1 day shorter to 0.2 days longer) | ‐ | 90 (2) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowd | US setting: treatment of diabetic ketoacidosis in a non–intensive care setting (step‐down unit or general medicine ward) was associated with a 39% lower hospitalisation charge than was treatment with intravenous regular insulin in the intensive care unit (USD 8801 (SD USD 5549) vs USD 14,429 (SD USD 5243); the average hospitalisation charges per day were USD 3981 (SD USD 1067) for participants treated in an intensive care unit compared with USD 2682 (SD USD 636) for those treated in a non–intensive care setting |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; h: hours; RR: risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

*Assumed risk was derived from the event rates in the comparator groups. aDowngraded by one level because of imprecision (see Appendix 12). bDowngraded by two levels because of risk of performance bias and serious imprecision (see Appendix 12). cDowngraded by three levels because of risk of performance bias, serious risk of inconsistency, and serious risk of imprecision (see Appendix 12). dDowngraded by two levels because of serious risk of imprecision (see Appendix 12).

Summary of findings 2. Subcutaneous insulin aspart versus intravenous regular insulin for diabetic ketoacidosis.

| Subcutaneous insulin aspart versus intravenous regular insulin for diabetic ketoacidosis | ||||||

| Patient: participants with diabetic ketoacidosis Settings: general medicine ward and intensive care unit Intervention: subcutaneous insulin aspart versus intravenous regular insulin | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Intravenous regular insulin | Subcutaneous insulin aspart | |||||

|

All‐cause mortality (N) Mean hospital stay: 3‐5 days |

See comment | See comment | Not estimable | 45 (1) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowa | No deaths reported |

|

Hypoglycaemic episodes (N) Mean hospital stay: 3‐5 days |

67 per 1000 | 67 per 1000 (5 to 970) | RR 1.00 (0.07 to 14.55) | 30 (1) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowb | ‐ |

| Morbidity | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | See comment | See comment | Not investigated |

| Adverse events other than hypoglycaemic episodes | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | See comment | See comment | Not investigated |

|

Time to resolution of diabetic ketoacidosis (h) Mean hospital stay: 3‐5 days |

The mean time to resolution of diabetic ketoacidosis across the intravenous regular insulin groups was 11 h | The mean time to resolution of diabetic ketoacidosis in the subcutaneous insulin aspart group was 1 h lower (3.2 h lower to 1.2 h higher) | ‐ | 30 (1) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very lowc | ‐ |

| Patient satisfaction | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | See comment | See comment | Not investigated |

|

Socioeconomic effects: length of hospital stay (days) Mean hospital stay: 3‐5 days |

The mean length of hospital stay in the intravenous regular insulin group was 4.5 days | The mean length of hospital stay in the subcutaneous insulin aspart group was 1.1 days shorter (3.3 days shorter to 1.1 days longer) | ‐ | 30 (1) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowd | ‐ |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; h: hours; RR: risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

*Assumed risk was derived from the event rates in the comparator groups aDowngraded by two levels because of serious imprecision (see Appendix 12) bDowngraded by two levels because of risk of performance bias and imprecision (see Appendix 12) cDowngraded by three levels because of risk of performance bias and serious risk of imprecision (see Appendix 12) dDowngraded by two levels because of serious risk of imprecision (see Appendix 12)

Background

Description of the condition

Diabetes mellitus is a metabolic disorder resulting from a defect in insulin secretion, insulin action, or both. A consequence of this is chronic hyperglycaemia (that is elevated levels of plasma glucose) with disturbances of carbohydrate, fat, and protein metabolism. Long‐term complications of diabetes mellitus include retinopathy, nephropathy, and neuropathy. The risk of cardiovascular disease is increased. Individuals with diabetes may be admitted to the hospital as a result of diabetic emergencies such as diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) or hyperosmolar hyperglycaemic state (HHS). DKA is an acute, major, life‐threatening complication of diabetes that occurs mainly in individuals with autoimmune type 1 diabetes, but it is not uncommon in some people with type 2 diabetes (Kitabchi 2009). DKA and HHS represent the most extreme consequences of uncontrolled diabetes mellitus.

In the USA, the incidence rate for DKA ranges from 4.6 to 8 episodes per 1000 people with diabetes of all ages, and 13.4 episodes per 1000 people with diabetes who are younger than 30 years old (Faich 1983; Johnson 1980). The incidence rate in the USA is comparable to the rates in Europe, with estimates of 13.6 per 1000 people with type 1 diabetes in the UK (Dave 2004). The mortality rate of DKA currently ranges from 0% to 19%, a rate that has shown a little decline in recent years (Basu 1993; Warner 1998). Mortality rates increase substantially with age and in the presence of concomitant life‐threatening illnesses such as co‐existent kidney disease and infections (Malone 1992). Hyperglycaemic crises are also economically burdensome, as DKA is responsible for more than 500,000 hospital days per year at an estimated annual direct medical expense and indirect cost of USD 2.4 billion (Kim 2007).

The basic mechanism for the development of DKA is a reduction in the effective insulin concentration and increased counter‐regulatory (catabolic or stress) hormones like glucagon, catecholamine, cortisol, and growth hormone. The hyperglycaemia of DKA results from increased hepatic glucose production (gluconeogenesis and glycogenolysis) and impaired peripheral glucose utilisation. Ketone bodies result from a marked increase in the free fatty acid release from adipocytes, with a resulting shift toward ketone body synthesis in the liver. This hormonal imbalance leads to the biochemical triad of DKA: hyperglycaemia, ketonaemia, and acidaemia (Kitabchi 2001). People with DKA are invariably volume depleted because insulin deficiency in DKA leads to hyperglycaemic osmotic diuresis and progressive volume depletion. Glycosuria is also accompanied by large urinary losses of potassium and phosphorus. The above processes can have several consequences, including tissue hypoxia, hyperviscosity, arrhythmia, and decreased blood flow to target organs like the brain.

Successful treatment of DKA requires correction of hyperglycaemia, skillful fluid and electrolyte adjustments, identification of comorbid precipitating events, and above all frequent and close monitoring of the patient (Kitabchi 2009). The treatment of diabetic ketoacidosis is traditionally accomplished by the administration of intravenous infusion of regular insulin, which is initiated in the emergency department and continued in an intensive care unit (ICU) or a high‐dependency unit environment, as endorsed by the American Diabetes Association and the Joint British Diabetes Societies guideline for the management of DKA (Kitabchi 2009; Savage 2011).

Description of the intervention

The first priority in the treatment of DKA is to restore intravascular volume to normalise tissue perfusion and aid in the delivery of insulin to target organs. Insulin administration is essential in the treatment and is initiated immediately, unless there is evidence of severe hypovolaemia or hypokalaemia. Insulin therapy lowers the serum glucose concentration primarily by decreasing hepatic glucose production rather than enhancing peripheral utilisation (Luzi 1988), diminishes ketone production (by reducing both lipolysis and glucagon secretion), and may augment ketone clearance. Insulin administration seeks to restore normal glucose uptake by cells; however, excessive insulin administration must be avoided to prevent hypoglycaemia and hypokalaemia.

The route of administration of insulin in the management of DKA has been debated since the early 1970s. Alberti 1973 reported the results of low‐dose intramuscular insulin in the management of people with DKA. They found that an initial average bolus dose of 16 units followed by 5 to 10 units of intramuscular regular insulin per hour was effective in correcting hyperglycaemia and acidaemia. Later in the 1970s, Fisher and colleagues reported a greater decline in blood glucose and ketone body levels in the first two hours of therapy with intravenous insulin as compared to intramuscular or subcutaneous insulin (Fisher 1977). Furthermore, the dehydration and shock state of people with DKA leads to erratic and unpredictable absorption of intramuscular and subcutaneous insulin (Fisher 1977). Based on this finding, it is now generally accepted that continuous intravenous infusion is the most effective route of insulin administration (Savage 2011).

Randomised controlled trials in people with DKA have shown insulin therapy to be effective regardless of the administration route. Treatment with subcutaneous rapid‐acting insulin analogues administered every one to two hours has been shown to be an effective alternative to the use of intravenous regular insulin in the treatment of uncomplicated DKA (Umpierrez 2004a; Umpierrez 2004b). In one of these trials, the authors found that the effects in people treated with subcutaneous insulin lispro were comparable with those treated with intravenous regular insulin. The authors observed similar rates of death, length of hospital stay, and amount of insulin used until resolution of DKA between treatment groups. Treatment of DKA in the ICU was associated with 39% higher hospitalisation charges than was treatment with subcutaneous lispro in a non‐intensive care setting (Umpierrez 2004b).

Adverse effects of the intervention

Hypoglycaemia is an inherent adverse effect of insulin treatment. Additionally, insulin therapy is associated with injection site reactions, generalised sensitivity reactions, and electrolyte imbalances such as hypokalaemia. Concern has been raised regarding potential mitogenic effects of insulin analogues, but evidence is controversial (Hemkens 2009; Kurtzhals 2000). Insulin lispro and insulin aspart, like human insulin, are rated category B for pregnancy use, which means that well‐controlled trials in pregnant women are lacking, while insulin glulisine is category C, because only animal reproduction studies have been performed with it (Home 2012).

How the intervention might work

In the last decade, considerable attention has been devoted to the development of insulin analogues with pharmacokinetic profiles that differ from existing insulin preparations. Compared to regular human insulin, proline at position 28 and lysine at position 29 of the B‐region were interchanged in the short‐acting insulin analogue lispro. In the short‐acting insulin analogue aspart, proline at position 28 of the B‐region was replaced by aspartic acid, and in the short‐acting insulin analogue glulisine, the amino acid asparagine was replaced by lysine at position three and lysine with glutamic acid at position 29 of the B‐chain (Siebenhofer 2006). Insulin lispro, insulin aspart, and insulin glulisine have very similar pharmacokinetic profiles. These analogues are present either in a monomeric form or a very weakly bound hexameric form. Following subcutaneous injection, they are rapidly absorbed in less than 30 minutes, with a short peak time of insulin concentration of 1 hour and a shorter duration of action of 3 to 4 hours when compared with regular human insulin (Roach 2008).

Data on rapid‐acting insulin analogues in clinical trials (not in DKA) suggest lower postprandial glucose variations when compared with meal‐time human insulin in adults and children, and in type 1 and type 2 diabetes (Home 2000; Mathiesen 2007; Rayman 2007). The decreased incidence of major hypoglycaemia requiring third‐party assistance, in particular major nocturnal hypoglycaemia, is the expected consequence of the shorter subcutaneous availability time of rapid‐acting insulin analogues. In people with type 1 diabetes, the median incidence of severe hypoglycaemia for rapid‐acting analogues is 21.8 episodes per 100 person‐years compared with 46.1 episodes for human insulin (Siebenhofer 2006). In people with type 2 diabetes, the median incidence is 0.3 episodes per 100 person‐years for analogues compared with a mean of 1.4 episodes per 100 person‐years for human insulin (Siebenhofer 2006).

The pharmacokinetic profile of rapid‐acting analogues following subcutaneous injection suggests that they might be a feasible alternative in the case of DKA, that is faster rise in plasma concentration, higher peak concentration, and shorter subcutaneous residence time than unmodified human insulin (Howey 1995).

Why it is important to do this review

As an alternative to an intravenous infusion of regular insulin, people with mild to moderate DKA can be treated with subcutaneous rapid‐acting insulin analogues, offering an opportunity to avoid costly admissions (Kitabchi 2009; Nyenwe 2011; Umpierrez 2004a; Umpierrez 2004b). Delivery of care without constant patient monitoring (for example outside ICU settings) will undoubtedly reduce cost. Also, stable patients could be treated in a step‐down unit close to their relatives.

Two systematic reviews comparing rapid‐acting insulin analogues with intravenous infusion of regular insulin in the treatment of mild to moderate DKA have been published (Mazer 2009; Vincent 2013). Both reviews provide an overview of the studies located, however there are some limitations. Firstly, the comprehensiveness of systematic literature searches was suboptimal. The literature search in Vincent 2013 was restricted exclusively to the PubMed database. Secondly, assessments of risk of bias of studies were not specified (Mazer 2009; Vincent 2013).

Given the limitations of previous systematic reviews, we plan to use specific methodology and criteria outlined by Cochrane in our aim to present a comprehensive systematic review to assess the efficacy and safety of subcutaneous rapid‐acting insulin analogues in the treatment of DKA in adults and children.

Objectives

To assess the effects of subcutaneous rapid‐acting insulin analogues for the treatment of diabetic ketoacidosis.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs).

Types of participants

We included trials evaluating participants with diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) of any age or sex with type 1 or type 2 diabetes, and pregnant women (including gestational diabetes).

Diagnostic criteria for diabetes mellitus

In order to be consistent with changes in classification and diagnostic criteria of diabetes mellitus over the years, we used the diagnostic criteria valid at the time of the trial commencing (for example ADA 1999; ADA 2008; WHO 1998). We used the study authors' definition of diabetes mellitus if necessary. We planned to subject diagnostic criteria to a sensitivity analysis.

Diagnostic criteria for diabetic ketoacidosis

We used the American Diabetes Association criteria for DKA (ADA 2004), which are as follows.

Mild DKA: plasma glucose > 250 mg/dL, arterial pH 7.25 to 7.30, serum bicarbonate 15 to 18 mEq/L, urine and serum ketones positive, anion gap > 10, alteration in sensoria or mental obtundation as alert.

Moderate DKA: plasma glucose > 250 mg/dL, arterial pH 7.00 to 7.24, serum bicarbonate 10 to < 15 mEq/L, urine and serum ketones positive, anion gap > 12, alteration in sensoria or mental obtundation as alert/drowsy.

Severe DKA: plasma glucose > 250 mg/dL, arterial pH < 7.00, serum bicarbonate < 10 mEq/L, urine and serum ketones positive, anion gap > 12, alteration in sensoria or mental obtundation as stupor/coma.

Types of interventions

We planned to investigate the effects of subcutaneous rapid‐acting insulin analogues versus standard intravenous infusion of regular insulin. We expected insulin regimens (use of intravenous bolus, dose, and frequency) to vary depending on the study, therefore we accepted all insulin regimens.

Intervention

Subcutaneous rapid‐acting insulin analogues (insulin lispro, insulin aspart, or insulin glulisine).

Comparator

Intravenous infusion of regular insulin.

Concomitant interventions had to be the same in the intervention and comparator groups to establish fair comparisons.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Time to resolution of DKA.

All‐cause mortality.

Hypoglycaemic episodes.

Secondary outcomes

Morbidity.

Adverse events other than hypoglycaemia.

Patient satisfaction.

Glycosylated haemoglobin A1c (HbA1c).

Socioeconomic effects.

Method and timing of outcome measurement

Time to resolution of DKA: defined as time to reach blood glucose levels < 200 mg/dL and two of the following criteria: a serum bicarbonate level ≥ 15 mEq/L, a venous pH > 7.3, and a calculated anion gap ≤ 12 mEq/L (Kitabchi 2009).

All‐cause mortality: defined as the total number of deaths from any cause and measured as in‐hospital mortality and 30‐day all‐cause mortality.

Hypoglycaemic episodes: defined as a symptomatic or asymptomatic event with plasma glucose ≤ 70 mg/dL (3.9 mmol/L) or according to authors' definition.

Morbidity: such as cerebral oedema defined by diagnostic criteria, including abnormal motor or verbal responses to pain, decorticate posture, and abnormal neurogenic respiratory patterns (major, but not diagnostic criteria include altered mentation, sustained heart rate decelerations, and age‐inappropriate incontinence; minor criteria include vomiting, headache, lethargy, diastolic blood pressure > 90 mm Hg, and age < 5 years (Muir 2004)).

Adverse events other than hypoglycaemia: such as hypokalaemia defined as a serum potassium concentration < 3.5 mEq/L, and injection site reactions.

Patient satisfaction: evaluated with a validated instrument such as the Insulin Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire (Anderson 2004).

HbA1c: measured at hospital admission (baseline) and at three months postdischarge.

Socioeconomic effects: such as length of hospital stay, calculated by subtracting day of admission from day of discharge, and costs, measured as data on hospital charges.

'Summary of findings' table

We present a 'Summary of findings' table reporting the following outcomes listed according to priority.

All‐cause mortality.

Hypoglycaemic episodes.

Morbidity.

Adverse events other than hypoglycaemic episodes.

Time to resolution of DKA.

Patient satisfaction.

Socioeconomic effects.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the following sources from inception of each database to the specified date and placed no restrictions on the language of publication.

-

Cochrane Library (27 October 2015)

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (Issue 9, September 2015)

Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE) (Issue 2, April 2015)

Health Technology Assessment (HTA) Database (Issue 3, July 2015)

Ovid MEDLINE(R) In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations and Ovid MEDLINE(R) (1946 to 27 October 2015)

PubMed (segments not available on Ovid) (27 October 2015)

EMBASE (1974 to 26 October 2015)

LILACS (23 October 2015)

CINAHL (27 October 2015)

ClinicalTrials.gov (http://www.clinicaltrials.gov, 27 October 2015)

-

WHO ICTRP Search Portal (http://apps.who.int/trialsearch/) (27 October 2015):

Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (19 October 2015)

Chinese Clinical Trial Registry (19 October 2015)

ClinicalTrials.gov (19 October 2015)

EU Clinical Trials Register (EU‐CTR) (19 October 2015)

ISRCTN (19 October 2015)

The Netherlands National Trial Register (19 October 2015)

Brazilian Clinical Trials Registry (ReBec) (13 October 2015)

Clinical Trials Registry ‐ India (13 October 2015)

Clinical Research Information Service ‐ Republic of Korea (13 October 2015)

Cuban Public Registry of Clinical Trials (13 October 2015)

German Clinical Trials Register (13 October 2015)

Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials (4 August 2015)

Japan Primary Registries Network (19 October 2015)

Pan African Clinical Trial Registry (13 October 2015)

Sri Lanka Clinical Trials Registry (13 October 2015)

Thai Clinical Trials Register (TCTR) (13 October 2015)

We continuously applied a MEDLINE (via Ovid) email alert service to identify newly published studies using the same search strategy as described for MEDLINE (for details on search strategies see Appendix 1). After supplying the final review draft for editorial approval, the Cochrane Metabolic and Endocrine Disorders Group performed a complete updated search on all databases available at the editorial office and sent the results to the review authors. Should we have identified new trials for inclusion, we evaluated these, incorporated the findings into our review, and resubmitted another review draft (Beller 2013).

We planned to evaluate any newly identified studies for inclusion, incorporate the findings into our review, and resubmit another review draft (Beller 2013).

If we detected additional relevant key words during any of the electronic or other searches, we would have modified the electronic search strategies to incorporate these terms and document the changes to the search strategy.

Searching other resources

We attempted to identify other potentially eligible trials or ancillary publications by searching the reference lists of retrieved included trials, (systematic) reviews, meta‐analyses, and health technology assessment reports.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (CAC, LCL) independently reviewed the abstract, title, or both, of every record retrieved in order to determine which trials should be assessed further. We investigated all potentially relevant articles as full text. We resolved any discrepancies through consensus or recourse to a third review author (NDF). If resolution of a disagreement was not possible, we planned to add the article to those 'awaiting assessment', and we would have contacted study authors for clarification. We have presented an adapted Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram showing the process of trial selection (Liberati 2009).

Data extraction and management

For trials that fulfilled our inclusion criteria, two review authors (CAC, LCL) independently abstracted relevant population and intervention characteristics using standard data extraction templates (for details see Characteristics of included studies; Table 3; Appendix 2; Appendix 3; Appendix 4; Appendix 5;Appendix 6; Appendix 7; Appendix 8; Appendix 9; Appendix 10; Appendix 11; Appendix 12), with any disagreements to be resolved by discussion, or, if required, by a third review author (NDF).

1. Overview of study populations.

| Intervention(s) and comparator(s) | Sample sizea | Screened/eligible [N] | Randomised [N] | Analysed [N] | Finishing trial [N] | Randomised finishing trial [%] | Follow‐up timeb | |

| Umpierrez 2004a | I: s.c. insulin lispro | Arbitrary estimation of a difference between groups of ≥ 5 hours to determine ketoacidosis as being clinically important; a sample size of 20 participants was needed in each group to provide a power of 0.93, given an alpha level of 0.05, a SD of 4, and a 1:1 inclusion ratio | ‐ | 20 | 20 | 20 | 100 | Mean hospital stay: 4 days |

| C: i.v. regular insulin | 20 | 20 | 20 | 100 | ||||

| total: | 40 | 40 | 40 | 100 | ||||

| Umpierrez 2004b | I1: s.c. insulin aspart, every hour | Arbitrary estimation of a difference between groups of ≥ 4 hours to determine ketoacidosis as being clinically significant. A sample size of 15 participants was needed in each group to provide a power of 0.81, given an alpha error of 0.05 and a SD of 3 | ‐ | 15 | 15 | 15 | 100 | Mean hospital stay: 3.4 days |

| I2: s.c. insulin aspart, every 2 h | 15 | 15 | 15 | 100 | Mean hospital stay: 3.9 days | |||

| C: i.v. regular insulin | 15 | 15 | 15 | 100 | Mean hospital stay: 4.5 days | |||

| total: | 45 | 45 | 45 | 100 | ||||

| Della Manna 2005 | I: s.c. insulin lispro | ‐ | ‐ | 25 | 25 | 25 | 100 | Mean hospital stay: 2‐3 days |

| C: i.v. regular insulin | 21 | 21 | 21 | 100 | ||||

| total: | 46 | 46 | 46 | 100 | ||||

| Ersöz 2006 | I: s.c. insulin lispro | ‐ | ‐ | 10 | 10 | 10 | 100 | ‐ |

| C: i.v. regular insulin | 10 | 10 | 10 | 100 | ||||

| total: | 20 | 20 | 20 | 100 | ||||

| Karoli 2011 | I: s.c. insulin lispro | ‐ | ‐ | 25 | 25 | 25 | 100 | Mean hospital stay: 6 days |

| C: i.v. regular insulin | 25 | 25 | 25 | 100 | Mean hospital stay: 6.6 days | |||

| total: | 50 | 50 | 50 | 100 | ||||

| Grand total | All interventions | 110 | 110 | |||||

| All comparators | 91 | 91 | ||||||

| All interventions and comparators | 201 | 201 | ||||||

aAccording to power calculation in study publication or report bDuration of intervention and/or follow‐up under randomised conditions until end of study

‐ denotes not reported

C: comparator; I: intervention; i.v.: intravenous; s.c.: subcutaneous; SD: standard deviation

We have provided information including trial identifier about potentially relevant ongoing trials in Characteristics of ongoing studies and in Appendix 5 ('Matrix of study endpoints (publications and trial documents)'). We attempted to identify the protocol of each included trial, either in trials registers, publications of study designs, or both, and specified data in Appendix 5.

We emailed authors of included trials to enquire as to whether they would be willing to answer questions regarding their trials. Appendix 13 shows the results of this survey. We thereafter sought relevant missing information on the trial from the primary author(s) of the article, if required.

Dealing with duplicate and companion publications

In the event of duplicate publications, companion documents, or multiple reports of a primary trial, we maximised yield of information by collating all available data and using the most complete data set aggregated across all known publications. Where unclear, the publication reporting the longest follow‐up associated with our primary or secondary outcomes obtained priority. We listed duplicate publications, companion documents or multiple reports of a primary trial as secondary references under the study ID of the included or excluded trial.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (CAC, NDF) independently assessed the risk of bias of each included trial. We resolved disagreements by consensus, or by consultation with a third review author (DGP).

We assessed risk of bias using the tool of The Cochrane Collaboration (Higgins 2011a; Higgins 2011b). We used the following criteria.

Random sequence generation (selection bias).

Allocation concealment (selection bias).

Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias).

Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias).

Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias).

Selective reporting (reporting bias).

Other potential sources of bias.

We judged 'Risk of bias' criteria as 'low risk', 'high risk', or 'unclear risk' and evaluated individual bias items as described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011a). We have presented a 'Risk of bias' graph and a 'Risk of bias summary'. We assessed the impact of individual bias domains on trial results at the endpoint and trial levels. In case of high risk of selection bias, we would have marked all endpoints investigated in the associated trial as 'high risk'.

For performance bias (blinding of participants and personnel) and detection bias (blinding of outcome assessors), we evaluated the risk of bias separately for each outcome (Hróbjartsson 2013). We noted whether outcomes were measured subjectively or objectively, for example if body weight was measured by participants or trial personnel.

We considered the implications of missing outcome data from individual participants per outcome such as high drop‐out rates (for example above 15%) or disparate attrition rates (for example difference of 10% or more between trial arms).

We assessed outcome reporting bias by integrating the results of 'Examination of outcome reporting bias' (Appendix 6) and 'Matrix of study endpoints (publications and trial documents)' (Appendix 5) (Kirkham 2010). This analysis formed the basis for the judgement of selective reporting (reporting bias).

We defined the following endpoints as subjective outcome measures.

Patient satisfaction.

Hypoglycaemic episodes, depending on measurement.

Adverse events other than hypoglycaemia, depending on measurement.

We defined the following endpoints as objective outcome measures.

Time to resolution of DKA.

All‐cause mortality.

Morbidity.

Hypoglycaemic episodes, depending on measurement.

Adverse events other than hypoglycaemia, depending on measurement.

HbA1c.

Socioeconomic effects.

Measures of treatment effect

We expressed dichotomous data as odds ratios or risk ratios with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). We expressed continuous data as mean differences with 95% CIs. We planned to express time‐to‐event data as hazard ratios with 95% CIs.

Unit of analysis issues

We took into account the level at which randomisation occurred, such as cross‐over trials, cluster‐randomised trials, and multiple observations for the same outcome.

Dealing with missing data

We obtained missing data from authors, if feasible, and carefully evaluated important numerical data such as screened, randomised participants as well as intention‐to‐treat and as‐treated and per‐protocol populations. We investigated attrition rates, (e.g. drop‐outs, losses to follow‐up, withdrawals), and we will critically appraise issues concerning missing data and imputation methods (e.g. last observation carried forward (LOCF)).

Where standard deviations for outcomes were not reported and we did not receive information from trial authors, we planned to impute these values by assuming the standard deviation of the missing outcome to be the average of the standard deviations from those studies where this information was reported. We wanted to investigate the impact of imputation on meta‐analyses by means of sensitivity analysis.

Assessment of heterogeneity

In the event of substantial clinical or methodological heterogeneity, we did not report trial results as the pooled effect estimate in a meta‐analysis.

We identified heterogeneity (inconsistency) through visual inspection of the forest plots and by using a standard Chi² test with a significance level of α = 0.1. In view of the low power of this test, we also considered the I² statistic, which quantifies inconsistency across trials to assess the impact of heterogeneity on the meta‐analysis (Higgins 2002; Higgins 2003); an I² statistic of 75% or more indicates a considerable level of heterogeneity (Higgins 2011a).

Had we found heterogeneity, we would have attempted to determine possible reasons for it by examining individual trial and subgroup characteristics.

Assessment of reporting biases

Had we included 10 trials or more investigating a particular outcome, we would have used funnel plots to assess small‐study effects. Several explanations can be offered for the asymmetry of a funnel plot, including true heterogeneity of effect with respect to trial size, poor methodological design (and hence bias of small trials), and publication bias. We therefore planned to interpret results carefully (Sterne 2011).

Data synthesis

Unless there was good evidence for homogeneous effects across studies, we primarily summarised low risk of bias data by means of a random‐effects model (Wood 2008). We interpreted random‐effects meta‐analyses with due consideration of the whole distribution of effects, ideally by presenting a prediction interval (Higgins 2009), which specifies a predicted range for the true treatment effect in an individual study (Riley 2011). In addition, we performed statistical analyses according to the statistical guidelines presented in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011a).

Quality of evidence

We have presented the overall quality of the evidence for each outcome according to the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach, which takes into account issues not only related to internal validity (risk of bias, inconsistency, imprecision, publication bias) but also to external validity, such as directness of results. Two review authors (CAC, NDF) independently rated the quality for each outcome. We have presented a summary of the evidence in 'Summary of findings' (SoF) tables, which provide key information about the best estimate of the magnitude of the effect, in relative terms and absolute differences for each relevant comparison of alternative management strategies, numbers of participants and trials addressing each important outcome, and the rating of the overall confidence in effect estimates for each outcome. We created the SoF tables based on the methods described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions by means of the table editor in Review Manager (RevMan), including Appendix 12 'Checklist to aid consistency and reproducibility of GRADE assessments' to help with standardisation of the 'Summary of findings' tables (Higgins 2011a; Meader 2014; RevMan 2014). Alternatively, we used the GRADEproGDT software and present evidence profile tables as an appendix (GRADEproGDT 2015). We have presented results on the outcomes as described in the Types of outcome measures section. If meta‐analysis was not possible, we presented results in a narrative form in the SoF table.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We expected the following characteristics to introduce clinical heterogeneity, and planned to carried out subgroup analyses with investigation of interactions.

Age.

Pregnancy.

Comorbidities.

Precipitating factors (infection, poor adherence to diabetes treatment).

Severity of DKA episode (mild, moderate, severe).

Sensitivity analysis

We planned to perform sensitivity analyses to explore the influence of the following factors (when applicable) on effect sizes by restricting the analysis to the following.

Published trials.

Taking into account risk of bias, as specified in the Assessment of risk of bias in included studies section.

Very long or large trials to establish the extent to which they dominate the results.

Trials using the following filters: diagnostic criteria, imputation, language of publication, source of funding (industry versus other), or country.

We also tested the robustness of the results by repeating the analysis using different measures of effect size (RR, OR, etc.) and different statistical models (fixed‐effect and random‐effects models).

Results

Description of studies

For a detailed description of the included trials, see Characteristics of included studies, Characteristics of excluded studies, and Characteristics of studies awaiting classification.

Results of the search

The electronic search strategies retrieved a total of 645 citations. After duplicates were excluded, two review authors (CAC, LCL) independently assessed the remaining titles and abstracts. We obtained the full text of 23 potentially relevant trials, seven of which we deemed potentially appropriate for inclusion in the analysis. Of these, two trials are awaiting classification, one trial was published as an abstract only, and another trial was registered in ClinicalTrials.gov with the status "This study has been completed", but no trial results were posted and no publication is available. We have provided information about these trials in Characteristics of studies awaiting classification.

We have provided an adapted PRISMA flowchart of study selection, see Figure 1.

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

For a detailed description of the included studies, see Characteristics of included studies. The following is a succinct overview.

Source of data

A total of five trials (five publications) met the inclusion criteria. All five included trials were published as peer‐reviewed original articles. All articles were published in English. We found no eligible trials from before the year 2004.

Comparisons

All five included trials investigated the effects of a subcutaneous rapid‐acting insulin analogues compared with intravenous regular insulin. Four trials used lispro (Della Manna 2005; Ersöz 2006; Karoli 2011; Umpierrez 2004a), and one used aspart as a rapid acting insulin analogue (Umpierrez 2004b). No trial applied glulisine.

Overview of study populations

The included trials evaluated a total of 201 participants, of which 110 received a subcutaneous rapid‐acting insulin analogue and 91 received intravenous regular insulin. All randomised participants finished their assigned treatment.

Study design

All included randomised controlled trials were of a parallel design and were performed in a single study centre. All trials compared a subcutaneous rapid‐acting insulin analogue with intravenous regular insulin in an open‐label fashion until resolution of the DKA episode. No trials specified blinding of outcome assessors. Trials were published from 2004 to 2011. Two trials were partly or entirely sponsored by the pharmaceutical industry (Umpierrez 2004a; Umpierrez 2004b).

Settings

Trials were conducted in the USA (Umpierrez 2004a; Umpierrez 2004b), Brazil (Della Manna 2005), Turkey (Ersöz 2006), and India (Karoli 2011) (see Characteristics of included studies for details). In the US and Brazilian trials, participants were treated with subcutaneous insulin managed in regular medicine wards, in Umpierrez 2004a and Umpierrez 2004b, or in the emergency department, in Karoli 2011, and the participants treated with intravenous insulin were managed in the intensive care unit (Karoli 2011; Umpierrez 2004a; Umpierrez 2004b). Two trials stated that the participants were managed in the emergency department (Della Manna 2005; Karoli 2011), and the Turkish trial did not provide details about the setting (Ersöz 2006).

Participants

A total of 201 participants were randomised and exposed to trial insulins in the included studies. All five trials recruited people who had a DKA episode (Della Manna 2005; Ersöz 2006; Karoli 2011; Umpierrez 2004a; Umpierrez 2004b). One trial included paediatric and adolescent participants (60 DKA episodes in 46 participants) with a median age of 11 years (range 3 to 17 years) (Della Manna 2005); the other trials included either type 1 or type 2 diabetic adults with a DKA episode (Ersöz 2006; Karoli 2011; Umpierrez 2004a; Umpierrez 2004b). No trial specified the number of participants or percentages of participants with either type of diabetes. Three trials reported duration of diabetes (Ersöz 2006; Karoli 2011; Umpierrez 2004a); mean duration of diabetes in these trials ranged between 3.9 and 6.9 years. The mean age of participants ranged between 34 and 49 years in the trials with adults only (Ersöz 2006; Karoli 2011; Umpierrez 2004a; Umpierrez 2004b). Sixty per cent of participants came from low‐ to middle‐income countries, and 27% to 76% were female. In one of the US trials, around 77% of participants were African American (Umpierrez 2004a). The other trials did not specify ethnic groups.

Four of the five trials reported a precipitating cause of the DKA episode (Della Manna 2005; Karoli 2011; Umpierrez 2004a; Umpierrez 2004b). Poor compliance with insulin therapy was the most common precipitating cause (54%). Other precipitating causes reported were infections (31%) and new‐onset diabetes (15%). Two trials reported HbA1c at baseline (Ersöz 2006; Umpierrez 2004b). Mean HbA1c at baseline in these trials ranged between 11.4% and 13.9%.

All trials listed persistent hypotension as an exclusion criterion, but only the US trials clearly defined this (Umpierrez 2004a; Umpierrez 2004b). Three trials excluded people with acute myocardial ischaemia, end‐stage renal disease, anasarca, and pregnancy (Karoli 2011; Umpierrez 2004a; Umpierrez 2004b). Two trials excluded people with dementia (Umpierrez 2004a; Umpierrez 2004b), heart failure (Karoli 2011; Umpierrez 2004a), and with American Diabetes Association (ADA) criteria for severe DKA (Ersöz 2006; Karoli 2011). Other criteria used for excluding participants were surgery, use of glucocorticoid or immunosuppressive agents (Della Manna 2005), and the presence of hepatic failure (Umpierrez 2004b).

Diagnosis

All trials specified diagnostic criteria for entry into the study. These criteria were consistent with the ADA criteria for mild or moderate DKA (ADA 2004). None of the included trials explicitly reported diagnostic criteria for diabetes mellitus.

Interventions

None of the included trials reported treatment before the DKA episode. All of the trials compared subcutaneous rapid‐acting insulin analogue injections every one to two hours with continuous intravenous infusions of regular insulin. Duration of interventions ranged from DKA diagnosis to DKA resolution.

Intravenous regular insulin regimens varied slightly across the trials. In three trials, the intravenous regular insulin bolus was 0.1 IU/kg, followed by continuous infusion given at 0.1 IU/kg/h until blood glucose decreased to < 250 mg/dL, and then continued at a lower dose (0.05 IU/kg/h until resolution of DKA) (Karoli 2011; Umpierrez 2004a; Umpierrez 2004b). Ersöz 2006 used a slightly higher bolus dose of intravenous regular insulin of 0.15 IU/kg/h followed by “standard” intravenous regular insulin infusion. In the paediatric trial (Della Manna 2005), no bolus was used, and intravenous regular insulin infusion was given at 0.1 IU/kg/h until blood glucose decreased to < 250 mg/dL; thereafter 0.15 IU/kg regular insulin was given subcutaneously 30 minutes before stopping the intravenous line.

Subcutaneous rapid‐acting insulin analogues injections varied across studies. Four trials used lispro at given dosages: injection regimens were either 0.15 IU every two hours without bolus (Della Manna 2005), or 0.075 IU/kg every hour, preceded by a bolus injection of intravenous regular insulin (0.15 IU/kg) (Ersöz 2006), or 0.1 IU/kg every hour, preceded by an initial subcutaneous bolus of insulin lispro (0.3 IU/kg) (Umpierrez 2004a), or initial subcutaneous bolus of insulin lispro (0.3 IU/kg), followed by 0.2 IU/kg one hour later and then 0.2 IU/kg every two hours (Karoli 2011). One trial used insulin aspart; subcutaneous insulin aspart was given as an initial dose of 0.3 IU/kg, followed by either 0.1 IU/kg every hour (group 1), or 0.2 IU/kg one hour later and every two hours (group 2) (Umpierrez 2004b). In one trial, when capillary blood glucose levels neared 250 mg/dL, insulin lispro was administered every four hours for the next 24 hours (Della Manna 2005).

Concomitant interventions

Fluid replacement protocols were similar in all included trials. This was largely in agreement with guideline recommendations (ADA 2004). Isotonic (0.9%) saline was infused at a rate of 10 to 20 mL/kg/h or 500 to 1000 mL/h for the initial one to two hours. Subsequent fluid replacement was adapted depending on the participant’s overall status and blood glucose levels until resolution of DKA. Potassium replacement was also in agreement with guideline recommendations (ADA 2004).

Outcomes

Three trials did not explicitly specify a primary outcome (Della Manna 2005; Ersöz 2006; Karoli 2011). Four trials defined DKA by venous pH criteria (Della Manna 2005; Ersöz 2006; Umpierrez 2004a; Umpierrez 2004b), and one trial by arterial pH (Karoli 2011). Four trials used a serum bicarbonate criterion > 18 mmol/L as an endpoint (Ersöz 2006; Karoli 2011; Umpierrez 2004a; Umpierrez 2004b). The paediatric trial used a serum bicarbonate criterion > 15 mmol/L (Della Manna 2005). Notably, only one trial clearly stated blood glucose levels < 200 mg/dL as an endpoint (Ersöz 2006).

All trials reported data on adverse events in the form of hypoglycaemic episodes during therapy. Four trials defined the endpoint for this outcome as a plasma glucose ≤ 60 mg/dL (Della Manna 2005; Karoli 2011; Umpierrez 2004a; Umpierrez 2004b). In the trial by Ersöz 2006, the outcome measure of hypoglycaemia was not defined. All five trials reported on in‐hospital mortality. Three trials reported length of hospital stay (Karoli 2011; Umpierrez 2004a; Umpierrez 2004b). The paediatric trial investigated morbidity in the form of cases of cerebral oedema (Della Manna 2005), and Karoli 2011 described venous thrombosis, adult respiratory distress syndrome, and hyperchloraemic acidosis events. One trial investigated total costs, measured as data on hospital charges (Umpierrez 2004a). No trial reported on patient satisfaction, adverse events other than hypoglycaemia, and change of HbA1c from baseline.

Excluded studies

We excluded 16 trials after evaluation of the full publication. We have provided reasons for exclusion of studies in Characteristics of excluded studies. The main reasons for exclusion were inappropriate interventions and non‐randomised study design.

Risk of bias in included studies

For details on risk of bias of included trials, see Characteristics of included studies.

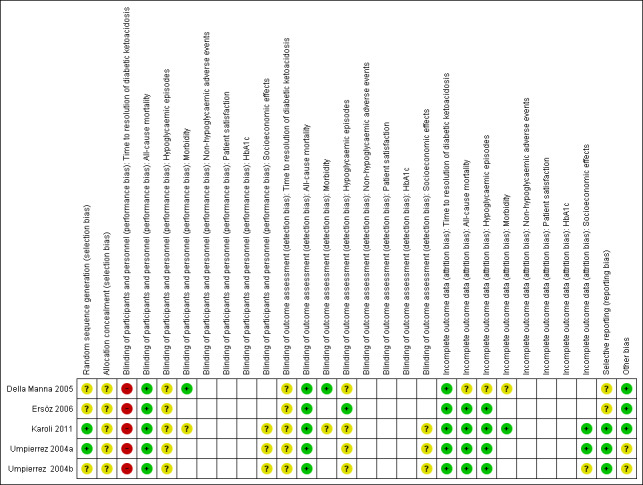

For an overview of review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for individual trials and across all trials, see Figure 2 and Figure 3.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included trials (blank cells indicate that the particular outcome was not measured in some trials).

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included trial (blank cells indicate that the trial did not measure that particular outcome).

Allocation

Reporting on the methods of randomisation and allocation concealment was poor in most of the trials. All trials were described as randomised, however the method of randomisation was adequately described in only two trials (Karoli 2011; Umpierrez 2004b). None of the included trials described allocation concealment.

Blinding

The stated method of blinding was open in all five trials. No trial described blinding of outcome assessors. Given the nature of the interventions, participant and personnel blinding was not appropriate. However, this implied a high risk of performance bias for the outcome measure time to resolution of DKA.

Incomplete outcome data

All five trials reported having complete data for all included participants.

Selective reporting

No study protocol was available for the included trials. Reporting bias was unclear for two trials due to unclear reporting of outcome data for time to resolution of DKA (Appendix 6) (Della Manna 2005; Ersöz 2006).

Other potential sources of bias

Two publications reported commercial funding (Umpierrez 2004a; Umpierrez 2004b), a source of possible sponsor bias.

Effects of interventions

Baseline characteristics

For details of baseline characteristics, see Appendix 3 and Appendix 4.

Subcutaneous rapid‐acting insulin analogues versus intravenous infusion of regular insulin

Umpierrez 2004b was a three‐arm trial investigating intravenous regular insulin versus subcutaneous insulin aspart, given in doses one or two hours apart. In order to avoid a unit of analysis error, we used the one‐hour group for all meta‐analyses.

Primary outcomes

Time to resolution of DKA

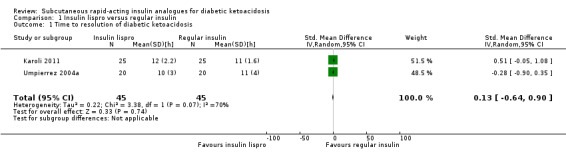

Lispro versus regular insulin (adults)

Two trials compared subcutaneous insulin lispro with intravenous regular insulin in adults with DKA (Karoli 2011; Umpierrez 2004a). Meta‐analysis showed the following differences between the two groups: mean difference (MD) 0.2 h (95% confidence interval (CI) ‐1.7 to 2.1); P = 0.81; 90 participants; 2 trials; very low‐quality evidence; Analysis 1.1. There was a high risk of performance bias and an unclear risk of detection bias for both included trials (Karoli 2011; Umpierrez 2004a).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Insulin lispro versus regular insulin, Outcome 1 Time to resolution of diabetic ketoacidosis.

Lispro versus regular insulin (children)

One trial including 60 children compared subcutaneous insulin lispro with intravenous regular insulin (Della Manna 2005). In both groups, the time to reach a glucose level of 250 mg/dL or less was approximately six hours. However, metabolic acidosis and ketosis took longer to resolve in the subcutaneous insulin lispro group (for intravenous regular insulin the time was six hours after capillary glucose ≤ 250 mg/dL, and for subcutaneous insulin lispro this occurred "in the next 6‐h interval" (Della Manna 2005)). The trial authors concluded that glycaemic control worsened when insulin lispro was spaced to every four hours, indicating that this was time was too long to maintain the insulin analogue action. In addition, children receiving insulin lispro were more likely to receive bicarbonate therapy. There was a high risk of performance bias, an unclear risk of detection bias, and an unclear risk of reporting bias for this included trial (Della Manna 2005).

Aspart versus regular insulin

One trial compared subcutaneous insulin aspart with intravenous regular insulin in an adult population (Umpierrez 2004b). There was the following difference between the two groups: MD ‐1 h (95% CI ‐3.2 to 1.2); P = 0.36; 30 participants; 1 trial; very low‐quality evidence; Analysis 2.1. There was a high risk of performance bias and an unclear risk of detection bias for this included trial (Umpierrez 2004b).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Insulin aspart versus regular insulin, Outcome 1 Time to resolution of diabetic ketoacidosis.

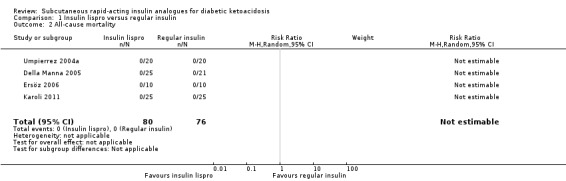

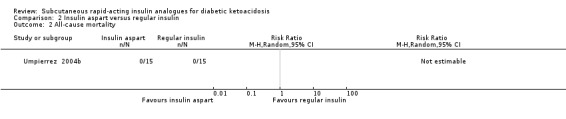

All‐cause mortality

All five included trials reported that there were no deaths (4 trials with 156 participants evaluating insulin lispro; moderate‐quality evidence; Analysis 1.1, and 1 trial with 45 participants evaluating insulin aspart (two different insulin aspart schemes in 15 participants each); low‐quality evidence; Analysis 2.1). However, no trial was adequately powered to investigate all‐cause mortality. There was an overall low risk of bias for this outcome measure.

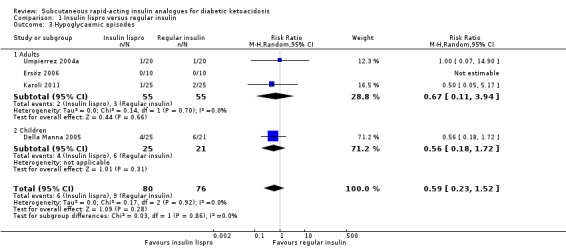

Hypoglycaemic episodes

Information on hypoglycaemia was available from all included trials. Hypoglycaemia was mostly defined as a blood glucose level lower than 60 mg/dL (Della Manna 2005; Karoli 2011; Umpierrez 2004a; Umpierrez 2004b). One trial did not provide a definition of hypoglycaemia (Ersöz 2006).

Lispro versus regular insulin

Four trials reported hypoglycaemic episodes (Della Manna 2005; Karoli 2011; Umpierrez 2004a; Umpierrez 2004b). Comparison of insulin lispro versus regular insulin showed a risk ratio (RR) 0.59 (95% CI 0.23 to 1.52); P = 0.28; 156 participants; 4 trials; low‐quality evidence; Analysis 1.3. There was a high risk of performance bias and an unclear risk of detection bias for all included trials.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Insulin lispro versus regular insulin, Outcome 3 Hypoglycaemic episodes.

Aspart versus regular insulin

One trial including 45 participants compared subcutaneous insulin aspart with intravenous regular insulin in an adult population (Umpierrez 2004b). Insulin aspart versus regular insulin did not show marked differences in the number of hypoglycaemic episodes (1/15 in the insulin aspart given every hour group; 1/15 in the insulin aspart given every two hours group; and 1/15 in the regular insulin group. RR comparing one of the two insulin aspart groups versus the regular insulin group was 1.00 (95% CI 0.07 to 14.55); P = 1.00; 30 participants; 1 trial; low‐quality evidence; Analysis 2.3. There was a high risk of performance bias and an unclear risk of detection bias for the included trial.

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Insulin aspart versus regular insulin, Outcome 3 Hypoglycaemic episodes.

Secondary outcomes

Morbidity

Two trials investigating the effects of insulin lispro versus regular insulin reported some data on morbidity related to the sequelae of DKA. One paediatric trial reported morbidity in the form of cerebral oedema (Della Manna 2005). There were no cases of cerebral oedema, and no child had to be treated with mannitol. Karoli 2011 reported that none of the participants in either group developed complications such as venous thrombosis, adult respiratory distress syndrome, or hyperchloraemic acidosis.

Adverse events other than hypoglycaemia

No trials reported adverse events other than hypoglycaemia.

Patient satisfaction

No trial reported on patient satisfaction.

HbA1c

HbA1c values were available in two trials for verification of metabolic control (Ersöz 2006; Umpierrez 2004b). However, the differences in change of HbA1c from baseline to study endpoint were not reported.

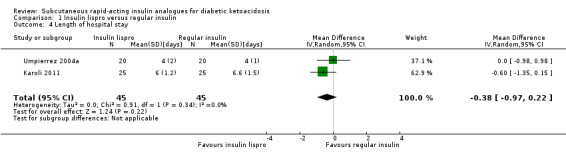

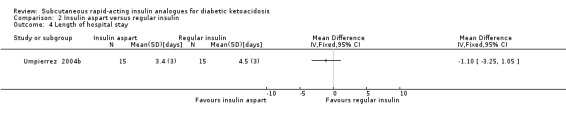

Socioeconomic effects

Three of the trials performed in adults reported length of hospital stay (Karoli 2011; Umpierrez 2004a; Umpierrez 2004b). Comparing subcutaneous insulin lispro with intravenous regular insulin resulted in a MD of ‐0.4 days (95% CI ‐1 to 0.2); P = 0.22; 90 participants; 2 trials; low‐quality evidence; (Analysis 1.4) and between subcutaneous insulin aspart and intravenous regular insulin: MD ‐1.1 day (95% CI ‐3.3 to 1.1); P = 0.32; 30 participants; 1 trial; low‐quality evidence (Analysis 2.4).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Insulin lispro versus regular insulin, Outcome 4 Length of hospital stay.

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Insulin aspart versus regular insulin, Outcome 4 Length of hospital stay.

One study addressed costs (Umpierrez 2004a). The study authors calculated that DKA treatment with subcutaneous insulin lispro in the non‐intensive care unit setting was associated with 39% lower hospitalisation charges compared with regular insulin treatment in the intensive care unit (USD 8801 (SD USD 5549) versus USD 14,429 (SD USD 5243).

Subgroup analyses

We did not perform subgroup analyses because there were not enough studies to estimate effects in various subgroups.

Sensitivity analyses

We could not perform preplanned analyses excluding unpublished trials because we included only published studies in this review. We were unable to perform sensitivity analyses with regard to risk of bias because all studies were of high or unclear risk of bias in various domains.

Assessment of reporting bias

We did not draw funnel plots due to limited number of studies (n = 5).

Ongoing studies

We did not identify ongoing randomised controlled trials.

Discussion

Summary of main results

This systematic review analysed the evidence from all published randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of subcutaneous rapid‐acting insulin analogues in the treatment of diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA). We included five trials with a total of 201 participants in this review. The results of our review suggest that there is no substantial difference in the time to resolution of DKA between the subcutaneous rapid‐acting insulin analogues lispro or aspart and intravenous regular insulin in adult participants. In the one included trial that assessed the effects of insulin lispro in children and adolescents with DKA, the resolution of acidaemia took longer as compared to intravenous regular insulin; the authors attributed this slower resolution to the increased interval of injections at every four hours after the initial decline of blood glucose to less than 250 mg/dL.

In terms of hypoglycaemia and length of hospital stay, the results obtained with subcutaneous rapid‐acting insulin analogues and regular insulin were comparable in both adults and children. No deaths occurred. Data on morbidity and socioeconomic effects were limited. None of the trials reported on adverse events other than hypoglycaemia, patient satisfaction, or glycosylated haemoglobin A1c.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

The trials analysed in this review were conducted in four different countries, three of which could be considered as low‐ or middle‐income countries. Notably, most participants representing the high‐income Western region were of African‐American ethnicity. Younger diabetic participants and children were underrepresented in our trial cohorts. Based on the inclusion criteria of the analysed trials, the results are most relevant to adults with a mild or moderate DKA episode due to poor compliance with diabetes therapy. This may reflect poor 'health literacy' and lack of comprehension of treatment plans, factors associated with socioeconomic deprivation in low‐ or middle‐income countries. Regarding the interventions, rapid‐acting insulin analogues like insulin lispro and insulin aspart are widely available for use in daily clinical practice.

Quality of the evidence

The risk of bias across several domains was unclear for the majority of included studies. This was due mainly to there being insufficient information to permit judgement of either a low or high risk of bias, despite attempts to contact the trial authors. According to the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach, the quality of the evidence was low or very low for most clinically important outcomes (see Table 1; Table 2). The available data were thus too few and inconsistent to provide firm evidence about the effects of subcutaneous rapid‐acting insulin analogues in people with DKA.

Potential biases in the review process

We conducted our review according to the previously published protocol. Two review authors independently assessed all citations identified by our electronic search strategies. Likewise, two review authors conducted 'Risk of bias' assessment and data collection. There were no conflicts of interests.

We believe that our search for RCTs has been comprehensive. However, we cannot exclude the possibility that studies with negative findings remain unpublished. Also, we did not systematically search the grey literature.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

Our systematic review on subcutaneous rapid‐acting insulin analogues for DKA is in agreement with previously published reviews, Mazer 2009 and Vincent 2013, and current guidelines on the management of a hyperglycaemic crisis in adults with diabetes; treatment with subcutaneous rapid‐acting insulin analogues (lispro and aspart) appears as an alternative to the use of intravenous regular insulin in the treatment of mild and moderate DKA (Kitabchi 2009).

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Our analyses suggest that, on the basis of mostly low‐ to very low‐quality evidence, there are neither advantages nor disadvantages when comparing the effects of subcutaneous rapid‐acting insulin analogues (insulin lispro, insulin aspart) versus intravenous regular insulin for treating DKA. These results are most relevant to adults with a mild or moderate DKA episode due to poor compliance with diabetes therapy.

Implications for research.

Due to the paucity of high‐quality evidence from RCTs comparing insulin interventions for DKA, future trials have the potential to change our way of treating this debilitating and expensive condition.

Future RCTs should adequately report on the method of randomisation and treatment allocation concealment. Blinding of study participants, study personnel, and outcome assessors could be done by using double‐dummy designs. Follow‐up of participants should be longer, and trial authors should adhere to the intention‐to‐treat principle. In addition, outcome measures should include patient satisfaction, morbidity, and socioeconomic effects. Finally, multicentre trials are desirable to ensure external validity.

Notes

We have based parts of the background, the methods section, appendices, additional tables and figures 1 to 3 of this review on a standard template established by the CMED Group.

Acknowledgements

We thank Karla Bergerhoff and Maria‐Inti Metzendorf, Trials Search Co‐ordinators of the Cochrane Metabolic and Endocrine Disorders Group, for developing the electronic search strategies.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Search strategies

| Cochrane Library |

| 1. [mh "Diabetic Ketoacidosis"] 2. [mh "Diabetic Coma"] 3. (("hyperglycaemic" or "hyperglycemic" or diabet*) next emergenc*):ti,ab,kw 4. (diabet* and (keto* or acidos* or "coma")):ti,ab,kw 5. "DKA":ti,ab,kw 6. {or #1‐#5} 7. [mh "Insulin Lispro"] 8. [mh "Insulin Aspart"] 9. [mh "Insulin, Short‐Acting"] 10. ("glulisine" or "apidra"):ti,ab,kw 11. ("humulin" or "novolin"):ti,ab,kw 12. ("lispro" or "aspart"):ti,ab,kw 13. ("novolog" or "novorapid"):ti,ab,kw 14. (insulin* near/4 analogue*):ti,ab,kw 15. (acting next insulin*):ti,ab,kw 16. {or #7‐#15} 17. #6 and #16 |

| MEDLINE (Ovid SP) |

| 1. Diabetic Ketoacidosis/ 2. Diabetic Coma/ 3. ((hyperglyc?emic or diabet*) adj emergenc*).tw. 4. (diabet* and (keto* or acidos* or coma)).tw. 5. DKA.tw. 6. or/1‐5 7. Insulin Lispro/ 8. Insulin Aspart/ 9. Insulin, Short‐Acting/ 10. (glulisine or apidra).tw. 11. (humulin or novolin).tw. 12. (lispro or aspart).tw. 13. (novolog or novorapid).tw. 14. (insulin* adj3 analogue*).tw. 15. acting insulin*.tw. 16. or/7‐15 17. 6 and 16 18. exp animals/ not humans/ 19. 17 not 18 |

| PubMed |

| #1 (hyperglycemic emergenc*[tw] OR hyperglycaemic emergenc*[tw] OR diabetic emergenc*[tw] OR (diabet*[tw] AND (ketoac*[tw] OR acidos*[tw] OR coma[tw])) OR DKA[tw]) #2 (glulisine[tw] OR apidra[tw] OR humulin[tw] OR novolin[tw] OR lispro[tw] OR aspart[tw] OR novolog[tw] OR novorapid[tw] OR (insulin[tw] AND analog*[tw]) OR acting insulin*[tw]) #3 #1 AND #2 #4 #3 NOT medline[sb] NOT pmcbook |

| EMBASE (Ovid SP) |

| 1. diabetic ketoacidosis/ 2. diabetic coma/ 3. ((hyperglyc?emic or diabet*) adj emergenc*).tw. 4. (diabet* and (keto* or acidos* or coma)).tw. 5. DKA.tw. 6. or/1‐5 7. insulin lispro/ 8. insulin aspart/ 9. insulin glulisine/ 10. short acting insulin/ 11. (glulisine or apidra).tw. 12. (humulin or novolin).tw. 13. (lispro or aspart).tw. 14. (novolog or novorapid).tw. 15. (insulin* adj3 analogue*).tw. 16. acting insulin*.tw. 17. or/7‐16 18. 6 and 17 [19: Wong et al. 2006 "sound treatment studies" filter – BS version] 19. random*.tw. or clinical trial*.mp. or exp health care quality/ 20. 18 and 19 21. limit 20 to embase |

| LILACS (IAHx) |

| (MH: "Diabetic Ketoacidosis" OR MH: "Diabetic Coma" OR (diabet$ AND (keto$ OR acidos$ OR "coma"))) AND (MH: "Insulin Lispro" OR MH: "Insulin Aspart" OR MH: "Insulin, Short‐Acting" OR ("glulisine" OR "apidra") OR ("humulin" OR "novolin") OR ("lispro" OR "aspart") OR ("novolog" OR "novorapid") OR (insulin$ AND analogue$) OR (acting AND insulin$)) + Filter "Controlled Clinical Trial" |

| CINAHL (Ebsco) |

| S1. MH "Diabetic Ketoacidosis" S2. MH "Diabetic Coma" S3. TI (("hyperglycaemic" OR "hyperglycemic" OR diabet*) N1 emergenc*) OR AB (("hyperglycaemic" OR "hyperglycemic" OR diabet*) N1 emergenc*) S4. TI (diabet* AND (keto* OR acidos* OR "coma")) OR AB (diabet* AND (keto* OR acidos* OR "coma")) S5. TI ("DKA") OR AB ("DKA") S6. S1 OR S2 OR S3 OR S4 OR S5 S7. MH "Insulin Lispro" S8. MH "Insulin Aspart" S9. MH "Insulin, Short‐Acting" S10. TI ("glulisine" OR "apidra") OR AB ("glulisine" OR "apidra") S11. TI ("humulin" OR "novolin") OR AB ("humulin" OR "novolin") S12. TI ("lispro" OR "aspart") OR AB ("lispro" OR "aspart") S13. TI ("novolog" OR "novorapid") OR AB ("novolog" OR "novorapid") S14. TI (insulin* N3 analogue*) OR AB (insulin* N3 analogue*) S15. TI (acting N1 insulin*) OR AB (acting N1 insulin*) S16. S7 OR S8 OR S9 OR S10 OR S11 OR S12 OR S13 OR S14 OR S15 S17. S6 AND S16 |

| ICTRP Search Portal |

| Standard search: diabet* AND keto* AND lispro OR diabet* AND acidos* AND lispro OR diabet* AND coma AND lispro OR diabet* AND keto* AND aspart OR diabet* AND acidos* AND aspart OR diabet* AND coma AND aspart OR diabet* AND keto* AND acting insulin OR diabet* AND acidos* AND acting insulin OR diabet* AND coma AND acting insulin OR diabet* AND keto* AND analogue* OR diabet* AND acidos* AND analogue* OR diabet* AND coma AND analogue* OR diabet* AND keto* AND glulisine OR diabet* AND acidos* AND glulisine OR diabet* AND coma AND glulisine |

| ClinicalTrials.gov |

| Advanced Search Search terms: ((diabetic OR diabetes) AND (ketoacidosis OR ketoacidoses OR acidosis OR acidoses OR ketosis OR ketoses OR coma)) AND (lispro OR aspart OR glulisine OR acting insulin OR apidra OR humulin OR novolin OR novolog OR novorapid OR analogue OR analogues) |

Appendix 2. Description of interventions

| Intervention(s) |

Adequatea intervention (Yes/No) |

Comparator(s) |

Adequatea comparator (Yes/No) |

|

| Umpierrez 2004a | Subcutaneous insulin lispro every hour: initial injection of 0.3 units/kg followed by 0.1 unit/kg/h until blood glucose levels reached 250 mg/dL; the insulin dose was then reduced to 0.05 units/kg/h, and the intravenous fluids were changed to dextrose 5% in 0.45% normal saline to keep blood glucose at a level of about 200 mg/dL until resolution of DKA | Yes | Intravenous regular insulin: initial bolus of 0.1 units/kg, followed by a continuous infusion of 0.1 units/kg/h until blood glucose levels decreased to approx. 250 mg/dL; at this time, intravenous fluids were changed to dextrose‐containing solutions, and the insulin infusion rate was decreased to 0.05 units/kg/h until resolution of DKA | Yes |