Abstract

Background

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are sought-after biomarkers of complex, polygenic diseases such as type 2 diabetes (T2D). Data-driven biocomputing provides robust and novel avenues for synthesizing evidence from individual miRNA seq studies.

Objective

To identify miRNA markers associated with T2D, via a data-driven, biocomputing approach on high throughput transcriptomics.

Materials and methods

The pipeline consisted of five sequential steps using miRNA seq data retrieved from the National Center for Biotechnology Information Gene Expression Omnibus platform: systematic review; identification of differentially expressed miRNAs (DE-miRNAs); meta-analysis of DE-miRNAs; network analysis; and downstream analyses. Three normalization algorithms (trimmed mean of M-values; upper quartile; relative log expression) and two meta-analytic algorithms (robust rank aggregation; Fisher's method of p-value combining) were integrated into the pipeline. Network analysis was conducted on miRNet 2.0 while enrichment and over-representation analyses were conducted on miEAA 2.0.

Results

A total of 1256 DE-miRNAs (821 downregulated; 435 upregulated) were identified from 5 eligible miRNA seq datasets (3 circulatory; 1 adipose; 1 pancreatic). The meta-signature comprised 9 miRNAs (hsa-miR-15b-5p; hsa-miR-33b-5p; hsa-miR-106b-3p; hsa-miR-106b-5p; hsa-miR-146a-5p; hsa-miR-483-5p; hsa-miR-539-3p; hsa-miR-1260a; hsa-miR-4454), identified via the two meta-analysis approaches. Two hub nodes (hsa-miR-106b-5p; hsa-miR-15b-5p) with above-average degree and betweenness centralities in the miRNA-gene interactions network were identified. Downstream analyses revealed 5 highly conserved- (hsa-miR-33b-5p; hsa-miR-15b-5p; hsa-miR-106b-3p; hsa-miR-106b-5p; hsa-miR-146a-5p) and 7 highly confident- (hsa-miR-33b-5p; hsa-miR-15b-5p; hsa-miR-106b-3p; hsa-miR-106b-5p; hsa-miR-146a-5p; hsa-miR-483-5p; hsa-miR-539-3p) miRNAs. A total of 288 miRNA-disease associations were identified, in which 3 miRNAs (hsa-miR-15b-5p; hsa-miR-106b-3p; hsa-miR-146a-5p) were highly enriched.

Conclusions

A meta-signature of DE-miRNAs associated with T2D was discovered via in-silico analyses and its pathobiological relevance was validated against corroboratory evidence from contemporary studies and downstream analyses. The miRNA meta-signature could be useful for guiding future studies on T2D. There may also be avenues for using the pipeline more broadly for evidence synthesis on other conditions using high throughput transcriptomics.

Keywords: Biomarkers, Differential expression, High throughput transcriptomics, Meta-analysis, Micro-RNAs, Type 2 diabetes

Highlights

-

•

Discovered a miRNA meta-signature associated with T2D via a data-driven pipeline.

-

•

Validated in-silico findings against existing evidence and via downstream analyses.

-

•

Meta-signature could help decode etiologic mechanisms and therapeutic targets of T2D.

-

•

Broader utility of the pipeline for biomedical evidence synthesis is envisioned.

Biomarkers; Differential expression; High throughput transcriptomics; Meta-analysis; Micro-RNAs; Type 2 diabetes.

1. Introduction

Type 2 diabetes (T2D) is a chronic, polygenic disorder of multifactorial etiology, which affected nearly 462 million individuals worldwide in 2017, equaling to 6.28% of the global population [1]. According to the projections of the International Diabetes Federation, the prevalence of T2D will increase by 25% by 2030 and 51% by 2045 [2]. The natural history of T2D entails a relatively long, early asymptomatic period characterized by subclinical disease, posing difficulties for its timely diagnosis. The magnitude of this diagnostic dilemma is exemplified by the reports that nearly half of the population with diabetes across the world remains undetected [3]. Classic hallmarks of T2D include insulin resistance primarily in skeletal muscle and adipose tissue, worsening pancreatic β-cell failure, hyperglycemia, liver adiposity, and glucose toxicity mediated chronic inflammation, inducing multiple direct and indirect complications. While genetics, environment, and gene-environment interactions all likely play key roles in the onset of T2D, its pathogenic mechanisms are not fully known.

Micro-RNAs (miRNAs) are highly sought-after as novel biomarkers of complex diseases including T2D [4], as they demonstrate a high degree of stability and reproducibility in various tissues and body fluids [5]. Besides enhancing current diagnostic efforts, deeper analysis of miRNA markers could also shed light on disease etiologies, guide drug target identification and facilitate the ultimate development of precision therapeutics [6]. These small (∼22 nucleotides), evolutionarily well-conserved, non-coding, single-stranded molecules have possible roles in multiple pathological and physiological phenomena such as cellular communications, angiogenesis, immune responses, and metastasis via gene-regulating effects on target mRNA translation [7]. Over 60% of the protein-coding genes in the human genome are reportedly regulated by miRNAs [8]. Recent studies ascribed certain miRNAs to T2D pathogenesis-related functions such as insulin action and secretion [9], insulin resistance and β-cell activity [10], glucose metabolism [11], as well as adipogenesis and obesity [12].

Data-driven research forms a pillar of precision medicine whereas multi-omics insights are fundamental to personalizing care pathways for complex, heterogeneous diseases such as T2D. Avenues for high level evidence synthesis are offered by expanding omics data repositories, continuing advancement of data science, and the diminishing cost of next generation sequencing techniques. Such large-scale studies could also allow for the discovery of potentially novel pathobiological pathways of heterogeneous diseases such as T2D, that would not be revealed in smaller individual studies. Moreover, high throughput miRNA sequencing is increasingly used and is preferred over traditional microarrays, due to its added merits such as less technical biases, higher multiplexing power, and the ability to detect previously uncharacterized miRNAs [13]. While individual miRNA seq studies focused on T2D are steadily reported, common drawbacks inherent in such studies are noteworthy. Individual miRNA-disease association studies tend to be under-powered due to small sample sizes, suffer from non-negligible experimental noise, and are prone to yielding inconsistent findings [14]. Meta-analysis is a viable approach for alleviating the biases of individual studies and merging their findings in order to derive high-level evidence. Thus far, only a few meta-analyses of profiling studies focused on miRNA-T2D associations have been conducted, all of which resorted to pooling published summary measures [15, 16, 17]. However, data-driven meta-analysis of raw, original omics data emanating from individual studies, though computationally intensive, could yield more reliable and robust results, compared to using summary measures [18]. With the growing availability of large raw data repositories such as the National Center for Biotechnology Information Gene Expression Omnibus (NCBI GEO) [19], such novel computational analyses are now possible.

Rigorous biocomputing pipelines consisting of impeccable preprocessing steps are required to gain accurate insights from miRNA seq studies. In particular, normalization strategies are critically important, as they are upstream factors that can strongly influence results [20]. While there is no gold standard for miRNA seq data normalization [21], various optimal methods have been proposed by previous studies [22]. Trimmed mean of M (TMM), upper quartile (UQ), and relative log expression (RLE) are standard normalization algorithms in an optimal miRNA seq preprocessing pipeline [23] and various combinations of these in previous studies yielded discordant results [20, 21, 22]. Meta-analytic algorithms regularly used on high throughput transcriptomics include robust rank aggregation (RRA) [24], p-value combining methods [25], and vote counting [26]. Of these, vote counting was found inadequate as a stand-alone meta-analytic strategy [27].

In this context, we aimed to identify miRNA markers of T2D via an extensive biocomputing pipeline utilizing raw miRNA seq data in the NCBI GEO repository. This consisted of five sequential steps: systematic review; identification of differentially expressed miRNAs (DE-miRNAs); meta-analysis of DE-miRNAs; network analysis; and downstream analyses. Three normalization strategies (TMM, UQ, RLE) and two meta-analytic processes (RRA, Fisher's method of p-value combining) were incorporated into the pipeline.

2. Methods

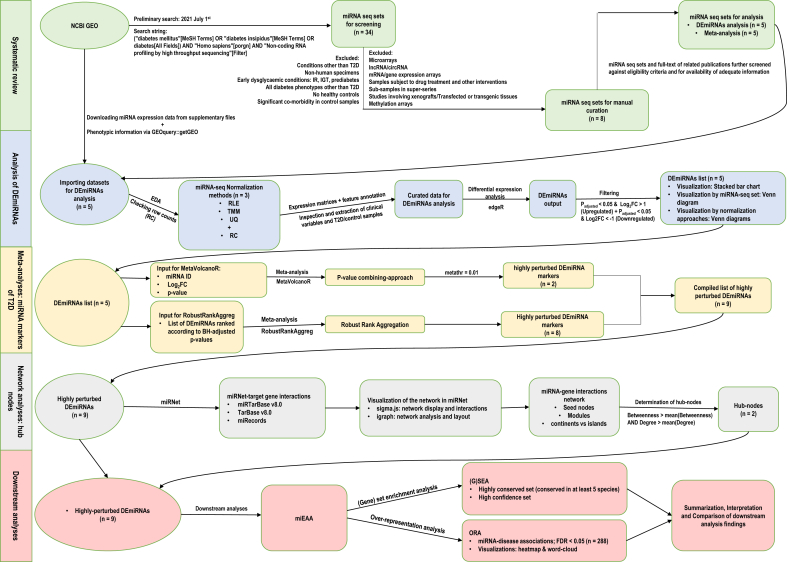

The analytic workflow is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Methodological workflow illustrating the five-step biocomputing pipeline employed in the study.

2.1. Systematic review

A preliminary search on the NCBI GEO platform was conducted on July 1, 2021 using the search string ("diabetes mellitus"[MeSH Terms] OR "diabetes insipidus"[MeSH Terms] OR diabetes[All Fields]) AND "Homo sapiens"[porgn] AND "Non-coding RNA profiling by high throughput sequencing"[Filter]. Publicly available data on the NCBI GEO were thus utilized in this study and no new unpublished data were included. All datasets resulting from this preliminary search were manually assessed against pre-defined eligibility criteria. We included miRNA seq sets focused on T2D with well-defined cases and controls, conducted on humans, with adequate information on tissues of origin, sample sizes, and feature annotation. Microarrays, lncRNA/circRNA, datasets with no healthy controls, samples subjected to drug treatments/other interventions, those focused on diabetes phenotypes other than T2D, non-human studies, and super-series were excluded. Datasets deemed eligible or unclear following this primary screening were included in secondary screening with downloaded raw data files and related publications.

2.2. Data retrieval and pre-processing

All eligible raw miRNA seq supplementary files were retrieved from the NCBI GEO platform while their phenotypic information was acquired using the ‘getGEO’ function of the GEOquery R package [28]. In each miRNA seq set, multiple probes hybridized to the same miRNA were collapsed by calculating mean counts across samples. Lowly expressed probes, defined as those with a mean raw count across samples <5, were removed.

2.3. Normalization

We applied three normalization techniques (TMM, UQ, RLE) on raw miRNA seq sets, via the edgeR R package [29]. A brief description of each method follows.

2.3.1. Trimmed mean of M-values (TMM)

Considered as a robust technique for standardizing miRNA seq synthesis ratios using a weighted trimmed mean of the log expression ratios, this method was first proposed by Robinson and Oshlack [30]. The TMM algorithm is based on fold-change (M) and absolute expression (A) values, which are defined below.

For a specific miRNA ‘a’ with expression levels Ka1 and Ka2 under the two conditions of interest, and N1 and N2 denoting the total number of reads in the two libraries, respectively:

Based on the assumption that most miRNAs are not differentially expressed, the normalization factor for a given sample against a reference sample is estimated as follows:

where,

, .

,

,

.

The TMM is calculated as a weighted average after certain upper and lower percentages of both M and A values (by default, 30% of M and 5% of A, by the edgeR package [29]) are removed, while precision (inverse variance) weights are used to account for disparities in read counts [30]. The library whose upper quartile is closest to the mean upper quartile is chosen as the reference by edgeR [29].

2.3.2. Upper quartile (UQ)

In this method, following exclusion of transcripts with null raw counts in all libraries, the scaling factor is determined by the 75th percentile of reads [20], as follows.

where,

Scaling entails the division of raw reads by the upper quartile of counts in each sample and multiplication by the mean upper quartile across all samples, as proposed by Bullard et al [31].

2.3.3. Relative log expression (RLE)

This algorithm, proposed by Anders and Huber [32], is also motivated by the assumption that a majority of miRNAs are not differentially expressed. The scaling factor, under this method, can be presented as follows:

where,

Kabc = Observed number of reads/counts of the miRNA:

In the condition of interest:

For the biological replicate:

The median library is enumerated via the geometric mean of all samples while the median ratio of each sample to the median library is considered as the scaling factor.

2.4. Differential expression analysis

Using the edgeR package in R version 4.1.0, differential expression analysis was conducted on four matrices (matrices normalized by the three methods described above, and non-normalized, original raw counts) of each miRNA seq set. The miRNAs with absolute log2Fold Change (FC) > 1 and Benjamini-Hochberg adjusted p-value < 0.05 were defined as differentially expressed. For those DE-miRNAs found in multiple matrices, we selected the row containing the highest absolute log2FC. Of note, one study (GSE109266) had directly provided information on DE-miRNAs instead of raw supplementary files, which was used in the current analysis.

2.5. Meta-analysis of differentially expressed miRNA

In order to derive a genome-wide meta-signature of miRNA markers associated with T2D, we meta-analyzed the DE-miRNAs using two strategies: Fisher's p-value combining method via the MetaVolcanoR package [33] and robust rank aggregation implemented in the RobustRankAggreg package [24]. Brief explanations of the two algorithms follow.

2.5.1. Fisher's p-value combining method

Fisher's method combines p-values from a set of independent tests, based on the same null hypothesis, according to the following formula:

where,

Pj = p-value of the jth hypothesis test

k = number of tests being pooled

Under the null hypothesis for a given test, its p-value conforms to a uniform distribution on the interval [0,1] and the sum of k independent tests attains a chi-squared distribution with 2k degrees of freedom. Recent reports confirmed the robustness of this method, including its ability to detect incomplete associations, outperforming other conventional meta-analysis techniques [25].

2.5.2. Robust rank aggregation

Based on the null hypothesis of unassociated inputs, RRA is a parameter-free meta-analytic algorithm which is resistant to outliers, bias, and noise.

For a normalized rank vector ν, reordered as ν1 ≤ …… ≤ νn, βk,n(ν) indicates the probability of ύk ≤νk, given the rank vector ύ is produced by the null model of uniform distribution. The probability of ύk ≤ y, under the null model, can then be written as a binomial probability:

The meta score ρ of the rank vector ν, is expressed as the minimum of p-values, based on the assumption that the number of informative ranks is not known:

Details of the RRA algorithm, proposed by Kolde et al., are available elsewhere [24].

2.6. Network analysis

Network analysis of the meta-signature was carried out on the miRNet 2.0 [34], which, by default, defines hub-nodes as those miRNAs with above-average degree and betweenness in the miRNA-target gene interactions network. These two measures of centrality can be defined as follows:

2.6.1. Degree centrality

where,

d(h) = degree of the vertex ‘h’

n = sum of all the vertices in the network graph

2.6.2. Betweenness centrality

where,

As the densely and tightly connected hub nodes in biological networks [35] tend to be critical functional regulators as well, they are sought after in precision medicine approaches [36]. We visualized the miRNA-target gene interactions network on miRNet 2.0 and determined the network attributes including hub nodes, modules, and continents versus islands.

2.7. Downstream analyses

Functional enrichments were detected via downstream analyses on the miRNA Enrichment Analysis and Annotation Tool 2.0 (miEAA 2.0) [37]. Enrichment analysis entailed the detection of highly conserved- (defined as conserved in at least 5 species) and high confidence- (those miRNAs with high probability expression profiles via small read mappings) sets. Through over-representation analysis, we detected miRNA-disease associations at a false discovery rate <0.05, and visualized them on miEAA2.0 as disease-miRNA association map and word-cloud figures.

3. Results

3.1. Systematic review

As shown in S1 Table, the preliminary search identified 34 eligible datasets, 8 of which were selected for secondary screening. A summary of these 8 datasets is provided in S2 Table. Three of these (GSE151496, GSE160308, GSE178721) had no adequate and conclusive information on the diabetes phenotype, and were therefore excluded. The final five sets selected for subsequent analysis emanated from circulatory (n = 3; GSE139577, GSE109266, GSE90028), adipose (n = 1; GSE174502), and pancreatic (n = 1; GSE52314) tissues. These comprised 113 samples in total (97 circulatory; 9 adipose; 7 pancreatic), of which 56 were T2D- and 57 were non-T2D control- samples (S2 Table).

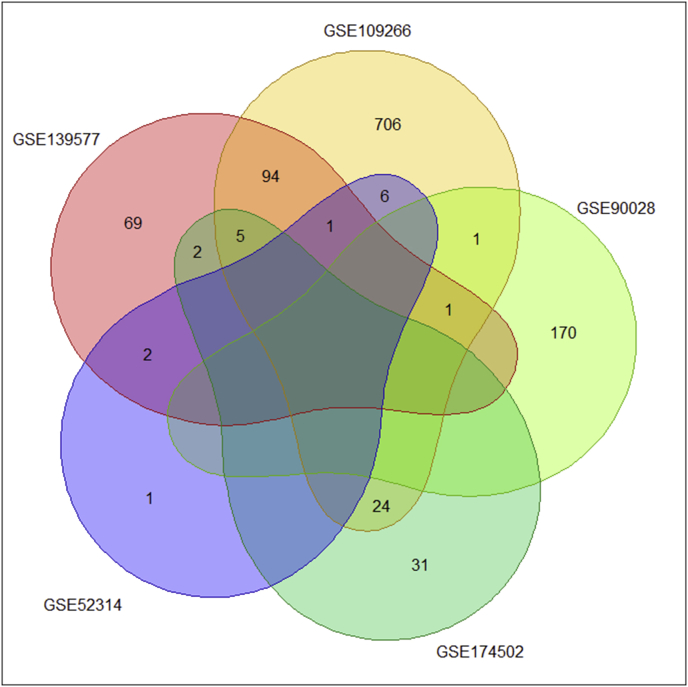

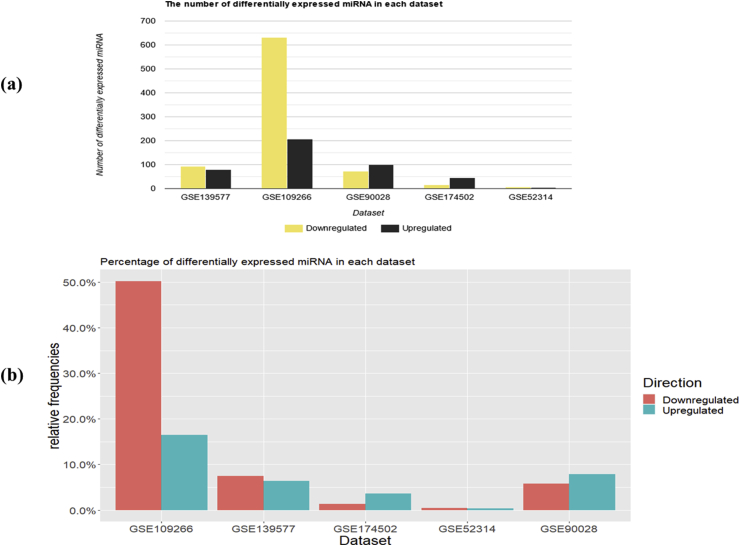

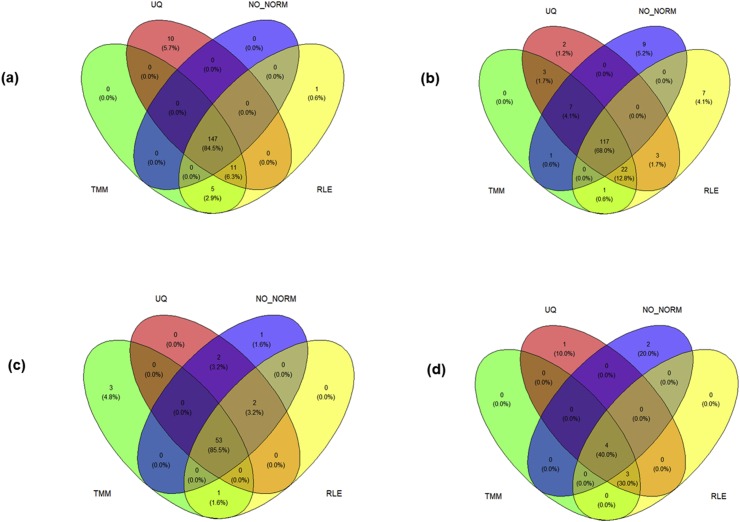

3.2. DE-miRNAs

As shown in Table 1, 1256 DE-miRNAs in total were identified across the five datasets. The number of DE-miRNAs in circulatory, adipose, and pancreatic tissues were 1184, 62, and 10, respectively. The majority of DE-miRNAs (977/1256) were exclusive to each dataset (GSE109266 = 706; GSE90028 = 170; GSE139577 = 69; GSE174502 = 31; GSE52314 = 1) (Figure 2). The dataset containing the greatest number of DE-miRNAs was GSE109266, while the total number of down-regulated miRNAs were significantly larger than the sum of up-regulated miRNAs (821 down-regulated and 435 up-regulated; p < 0.0001) (Table 1; Figure 3). The proportions of miRNAs identified as differentially expressed by all three normalization algorithms as well as via raw counts in the four datasets: GSE139577; GSE90028; GSE174502; and GSE 52314 were 147/174; 117/172; 53/62; and 4/10, respectively (Figure 4).

Table 1.

The distribution of differentially expressed miRNA identified in each RNA-seq dataset.

| Dataset | Tissue type/biospecimen | # DE-miRNAa | # Upregulated | # Downregulated | p-valueb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GSE139577 | Circulatory | 174 | 80 | 94 | 0.1339 |

| GSE109266 | Circulatory | 838 | 207 | 631 | <0.0001 |

| GSE90028 | Circulatory | 172 | 99 | 73 | 0.0051 |

| GSE174502 | Adipose | 62 | 45 | 17 | <0.0001 |

| GSE52314 | Pancreatic | 10 | 4 | 6 | 0.3833 |

| Totalc | – | 1256 | 435 | 821 | <0.0001 |

a: defined as miRNA with absolute log2 fold change >1 and Benjamini- Hochberg adjusted p-value < 0.05; b: computed by chi-squared test for two proportions; c: including genes commonly expressed across multiple tissues.

DE-miRNA: differentially expressed miRNA.

Figure 2.

Venn diagram depicting the number and overlap of differentially expressed miRNA identified by each high throughput transcriptomics set. Number of shared and non-shared miRNAs across the five sets are discernible.

Figure 3.

Stacked bar charts depicting (a) the number of up- and down-regulated miRNA in each high throughput transcriptomic set (b) the percentage of up- and down-regulated miRNA in each high throughput transcriptomic set.

Figure 4.

Distribution of differentially expressed miRNA in each dataset and the overlap across normalization methods (a) GSE139577: circulatory (b) GSE90028: circulatory (c) GSE174502: adipose (d) GSE52314: pancreatic [GSE109266 (circulatory) provided differentially expressed miRNA information directly and these were used for analyses]. NO_NORM = no normalization – raw counts used; RLE = relative log expression normalization; TMM = trimmed mean of M-values normalization; UQ = upper quartile normalization.

3.3. Meta-analyses

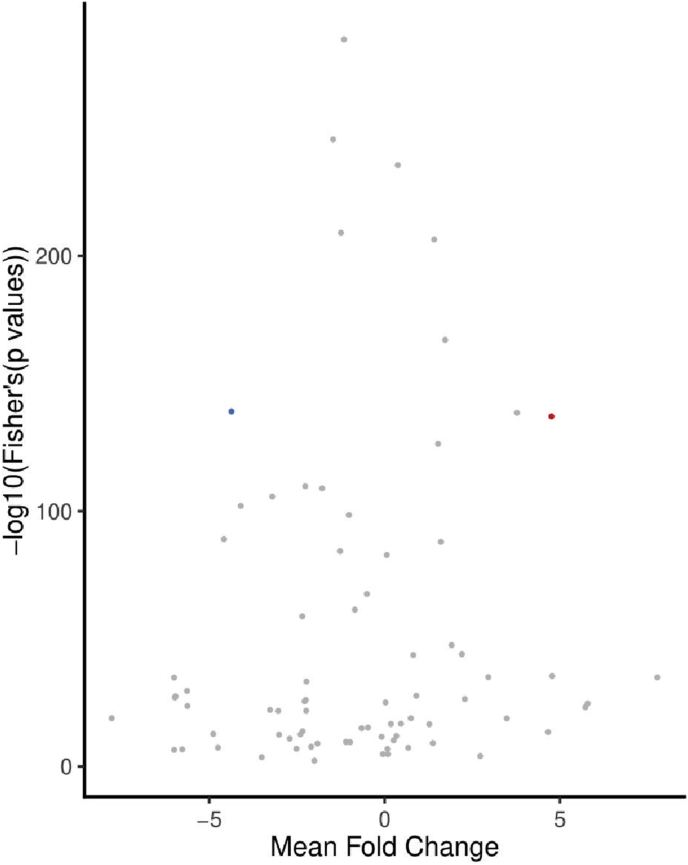

The meta-signature consisted of two miRNA markers identified by Fisher's p-value combining method (hsa-miR-33b-5p, hsa-miR-539-3p) (Figure 5) and eight miRNA markers elucidated by RRA (hsa-miR-15b-5p, hsa-miR-106b-3p, hsa-miR-106b-5p, hsa-miR-146a-5p, hsa-miR-483-5p, hsa-miR-539-3p, hsa-miR-1260a, hsa-miR-4454) (Table 2). One miRNA marker, i.e. hsa-miR-539-3p was identified by both methods, resulting in a meta-signature of 9 miRNAs. Of the 9 miRNAs, 8 were down-regulated while a single miRNA (hsa-miR-33b-5p) was up-regulated. Also, hsa-miR-33b-5p was differentially expressed in both circulatory and adipose tissues, while all other miRNAs constituting the meta-signature were exclusively found in circulatory tissues (Table 2).

Figure 5.

Volcano plot depicting Fisher's p-value combining meta-analysis output employed via MetaVolcanoR. Two highly perturbed genes were identified at metathr = 0.01 (default threshold specified by the package). Red and blue dots indicate hsa-miR-33b-5p (upregulated) and hsa-miR-539-3p (downregulated), respectively.

Table 2.

The meta-signature of micro-RNA markers associated with type 2 diabetes identified by the two meta-analytic strategies: p-value combining method and robust rank aggregation.

| miRNA | Meta-p value/ρ scorea | Expressed in | Regulation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Identified by meta-analysis with p-value combining method | |||

| hsa-miR-33b-5p | 6.87E-138 | Adipose, Circulatory | Up |

|

hsa-miR-539-3p |

7.92E-140 |

Circulatory |

Down |

| Identified by meta-analysis with robust rank aggregation | |||

| hsa-miR-15b-5p | 0.0224214885 | Circulatory | Down |

| hsa-miR-106b-3p | 0.0490074419 | Circulatory | Down |

| hsa-miR-106b-5p | 0.0260325689 | Circulatory | Down |

| hsa-miR-146a-5p | 0.0438733059 | Circulatory | Down |

| hsa-miR-483-5p | 0.0241123607 | Circulatory | Down |

| hsa-miR-539-3p | 0.0003613095 | Circulatory | Down |

| hsa-miR-1260a | 0.0224214885 | Circulatory | Down |

| hsa-miR-4454 | 0.0447624691 | Circulatory | Down |

a: p-value combining meta-analysis in MetaVolcanoR computes a meta-p score based on meta log2 fold-change across studies while robust rank aggregation computes a ρ score based on p-values of DEmiRNAs in individual studies.

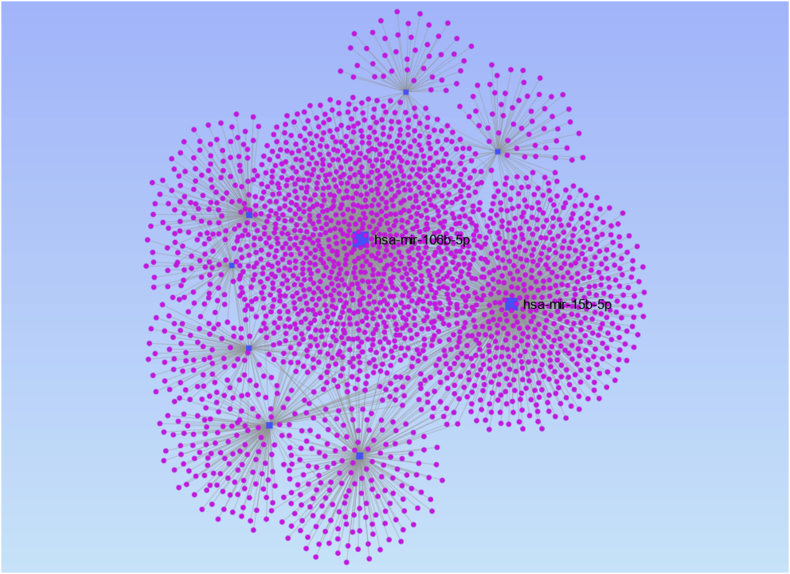

3.4. Network analyses

The miRNA-gene interactions network derived by miRNet 2.0 is presented in Figure 6, while the details of the network are shown in S3 Table. Two miRNAs with above average betweenness and degree centralities, namely, hsa-miR-15b-5p and hsa-miR-106b-5p were demarcated as hub nodes (Table 3, Figure 6). Topologically, the network constituted of nine modules, each clustered around a specific miRNA. Those two modules around the two hub nodes formed large and dense sub-networks characterized as continents while the remainder formed smaller sub-networks stipulated as islands (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

The miRNA-gene interactions network visualized in miRNet 2.0. The two hub-nodes (hsa-miR-106b-5p & hsa-miR-15b-5p) with above-average degree and betweenness are highlighted.

Table 3.

Topological characteristics of the miRNA-gene interactions network.

| miRNA ID | Degree |

Betweenness |

Hub node status |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean = 296 | Mean = 510899.445555 | ||

| hsa-miR-15b-5p | 760 | 1322515.59471805 | Yes |

| hsa-miR-146a-5p | 203 | 367850.990663118 | No |

| hsa-miR-106b-5p | 1091 | 1871815.20015558 | Yes |

| hsa-miR-33b-5p | 101 | 166566.827091811 | No |

| hsa-miR-106b-3p | 76 | 123910.221308144 | No |

| hsa-miR-483-5p | 143 | 253701.019330487 | No |

| hsa-miR-1260a | 162 | 288253.085747575 | No |

| hsa-miR-4454 | 58 | 96535.6018030646 | No |

| hsa-miR-539-3p | 67 | 106946.459182154 | No |

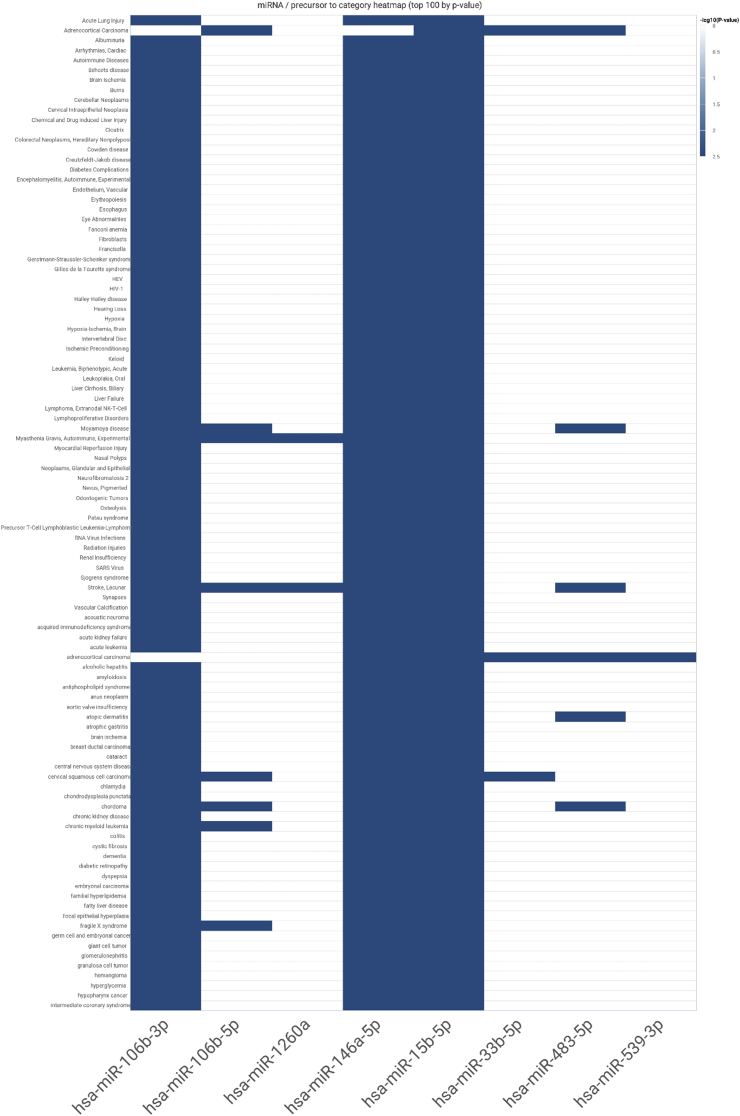

3.5. Downstream analyses

Functional enrichment analyses determined five miRNA markers (hsa-miR-33b-5p; hsa-miR-15b-5p; hsa-miR-106b-3p; hsa-miR-106b-5p; hsa-miR-146a-5p) as highly conserved while seven miRNAs (hsa-miR-33b-5p; hsa-miR-15b-5p; hsa-miR-106b-3p; hsa-miR-106b-5p; hsa-miR-146a-5p; hsa-miR-483-5p; hsa-miR-539-3p) constituted the highly confident set (S4 Table). Over-representation analysis identified 288 significant miRNA-disease associations in total, including hyperglycemia, diabetes complications, diabetic retinopathy and many other chronic cardiometabolic diseases and neoplastic conditions, the details of which are presented in S5 Table. As shown in Figure 7, three miRNAs (hsa-miR-15b-5p, hsa-miR-106b-3p, hsa-miR-146a-5p) were highly enriched across a majority of miRNA-disease associations. The top 100 enriched diseases associated with the 9 miRNA markers according to Benjamini-Hochberg adjusted p-values are visualized as a word-cloud in S1 Figure.

Figure 7.

The default disease-miRNA associations map illustrating the top 100 associations, produced by miEAA 2.0. Three miRNAs (hsa-miR-15b-5p, hsa-miR-106b-3p, hsa-miR-146a-5p) are highly over-represented.

4. Discussion

In this in-silico analysis, we identified a genome-wide meta-signature of nine miRNA markers associated with T2D via a data-driven, biocomputing workflow. Biological plausibility of the findings was validated through downstream analyses and in the backdrop of contemporary literature. We envisage that the proposed biocomputing workflow would be widely adoptable for studies using data-driven approaches on high throughput transcriptomics for biomarker discovery, including systemic or tissue non-specific meta-signatures.

A recent high throughput plasma sequencing study revealed the down-regulation of three of the circulating miRNAs present in the identified meta-signature (hsa-miR-15b-5p, hsa-miR-106b-3p, hsa-miR-106b-5p), in association with incident T2D [38]. Multiple studies attest to the upregulation of hsa-miR-33b-5p in circulatory and adipose tissues in the presence of dysglycemia. It has been reported that increased hsa-miR-33b-5p levels associate with both insulin resistance and adiposity [39], and leads to impaired insulin signaling as well as reduced fatty acid oxidation [40]. Moreover, upregulation of hsa-miR-33b-5p in cultured adipocytes inhibited GLUT4 – a key gene involved in insulin-mediated glucose transport and homeostasis [41]. Conversely, the inhibition of miR-33 was found to be able to overcome the harmful effects of diabetes on atherosclerosis [42]. Lower circulating levels of hsa-miR-146a were associated with both T2D and prediabetes, playing a potential role in inflammation, as per a case-control study [43]. Another experimental study revealed that hsa-miR-146a-5p is downregulated in human aortic endothelial cells in the presence of high glucose, acting as a mediator of high-glucose induced endothelial inflammation [44]. A nested case-control study found significantly decreased hsa-miR-483-5p levels in the plasma of individuals with prediabetes which indicated its potential utility as a diagnostic predictor/circulating biomarker of β-cell function [45]. Significant downregulation of hsa-miR-539-5p was previously detected in the circulation of individuals with uncontrolled diabetes [46] while another study discovered its implications on both diabetes and the heart [47]. Down-regulation of both hsa-miR-1260a [48,49] and hsa-miR-4454 [49] in the circulation of individuals with T2D was also previously reported. Reduced circulating hsa-miR-4454 levels are associated with early onset obesity as well [50]: a condition that could quadruple the risk of subsequent development of T2D [51]. Concordant findings from contemporary studies with respect to the meta-signature are summarized in S6 Table.

Systems biology insights on miRNA-T2D associations, rendered by network analyses are noteworthy. Since the two hub nodes (hsa-miR-106b-5p & hsa-miR-15b-5p) which formed epicenters of the two most densely and extensively connected sub-networks might have crucial functional roles as well [35, 36], further research on their roles on T2D pathogenesis is warranted. Another insightful observation was the disproportionately high representation of three markers (hsa-miR-15b-5p, hsa-miR-106b-3p, hsa-miR-146a-5p) within the miRNA-disease associations network, which suggested that they likely have key roles in the development of not only T2D but also other cardiometabolic diseases and co-morbidities via multiple cross-talk and pleiotropic mechanisms. The highly conserved- and confident sets of miRNAs, as well as the large number of miRNA-disease associations identified by downstream analyses, provide important guidance and directions on the miRNA markers of T2D to inform future studies. Therefore, future studies focusing on the functions of the miRNAs constituting the meta-signature, including their roles in pathobiological pathways of T2D and as potential biomarkers of T2D-associated comorbidity, would be informative. Longitudinal studies exploring the mRNA and protein expression of identified miRNAs are also recommended as they might assist us in determining whether plausible targets of these miRNAs predict the onset of incident T2D.

The predominance of circulatory miRNAs in the meta-signature could have resulted from the nature of the origins of data sources. A vast majority of miRNA seq data emanated from circulatory tissues, while only a few DE-miRNAs were uncovered in adipose and pancreatic tissues. It should be noted, however, that the circulating miRNAs are often preferred as minimally-invasive biomarkers. They have clear merits including remarkable stability, relatively easy detectability, high sensitivity, and the ability to provide mechanistic insights via their dynamic expression patterns under different pathological or physiological conditions [52]. The meta-signature derived by current analysis may therefore have greater clinical value as a potential diagnostic tool of T2D. Nevertheless, the lack of miRNA seq data from other tissue types was a limitation, which may need to be attended to in the quest for unravelling the complex pathobiology of T2D. The divergent nature of datasets emanating from different tissues and producing vastly different amounts of DE-miRNAs, may have influenced the meta-analytic outputs. Consequently, meta-analyses may have lacked sufficient sensitivity to identify all miRNA markers associated with T2D, in the current study.

Given the lack of consensus on gold standard algorithms for normalizing and meta-analyzing high throughput transcriptomics, it would be prudent to apply a nuanced mix of these techniques, as was done in the current analysis, instead of resorting to a random, single method. While both contemporary evidence and downstream analysis outputs corroborated our findings, further in-vitro and in-vivo experimental studies are recommended to validate the meta-signature of T2D derived via in-silico analyses in the present study. As the miRNA seq databases are gradually getting scaled up, we underscore the potential value of data-driven meta-analyses of high throughput transcriptomics which have hitherto been utilized only sparsely, compared to more abundant meta-analyses of the aggregate measures reported in published studies. Lastly, the proposed biocomputing pipeline could be widely adopted as a robust evidence synthesis strategy in data-driven, high throughput transcriptomics studies focused on various other conditions.

5. Conclusions

In this study, a meta-signature of DE-miRNAs associated with T2D was discovered via a data-driven, biocomputing pipeline on high throughput transcriptomics. In-silico findings were validated against corroboratory evidence from contemporary studies and via downstream analyses. The miRNA meta-signature could be useful for guiding future studies such as those aimed at unravelling pathological mechanisms and effective therapeutics of T2D. There may also be avenues for using the proposed pipeline more broadly for evidence synthesis on other conditions using high throughput transcriptomics data.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

Kushan De Silva: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Ryan T. Demmer: Conceived and designed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Wrote the paper.

Daniel Jönsson, Aya Mousa: Analyzed and interpreted the data; Wrote the paper.

Andrew Forbes: Conceived and designed the experiments; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Joanne Enticott: Conceived and designed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Funding statement

This work was supported by a PhD scholarship funded by the Australian Government under Research Training Program (RTP).

Data availability statement

Data associated with this study has been deposited at the National Center for Biotechnology Information Gene Expression Omnibus (NCBI GEO) portal: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/

Declaration of interests statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the supplementary data related to this article:

S1 Figure.tif.

Word cloud of enriched diseases associated with the 9 miRNA markers.

Details of the studies (n = 34) that underwent primary screening.

Details of the studies (n = 8) that underwent secondary screening.

Details of the miRNA-gene associations network generated by miRNet 2.0.

Conserved and confident miRNA sets identified via functional analyses on miEAA 2.0.

Table: Details of the miRNA-disease associations revealed by enrichment analyses on miEAA 2.0.

Supporting evidence from contemporary studies with respect to the meta-signature of miRNAs identified in the current study.

References

- 1.Khan M.A.B., Hashim M.J., King J.K., Govender R.D., Mustafa H., Al Kaabi J. Epidemiology of type 2 diabetes - global burden of disease and forecasted trends. J. Epidemiol. Glob. Health. 2020;10(1):107–111. doi: 10.2991/jegh.k.191028.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saeedi P., Petersohn I., Salpea P., Malanda B., Karuranga S., Unwin N., et al. Global and regional diabetes prevalence estimates for 2019 and projections for 2030 and 2045: results from the international diabetes federation diabetes atlas, 9th edition. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2019;157:107843. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2019.107843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weale C.J., Matshazi D.M., Davids S.F.G., Raghubeer S., Erasmus R.T., Kengne A.P., et al. MicroRNAs-1299, -126-3p and -30e-3p as potential diagnostic biomarkers for prediabetes. Diagnostics (Basel) 2021;11(6):949. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics11060949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen X., Xie D., Zhao Q., You Z.H. MicroRNAs and complex diseases: from experimental results to computational models. Briefings Bioinf. 2019;20(2):515–539. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbx130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Faruq O., Vecchione A. microRNA: diagnostic perspective. Front. Med. 2015;2:51. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2015.00051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hanna J., Hossain G.S., Kocerha J. The potential for microRNA therapeutics and clinical research. Front. Genet. 2019;10:478. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2019.00478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Catalanotto C., Cogoni C., Zardo G. MicroRNA in control of gene expression: an overview of nuclear functions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016;17(10):1712. doi: 10.3390/ijms17101712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang F., Wang D. The pattern of microRNA binding site distribution. Genes (Basel) 2017;8(11):296. doi: 10.3390/genes8110296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Calderari S., Diawara M.R., Garaud A., Gauguier D. Biological roles of microRNAs in the control of insulin secretion and action. Physiol. Genom. 2017;49(1):1–10. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00079.2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaur P., Kotru S., Singh S., Behera B.S., Munshi A. Role of miRNAs in the pathogenesis of T2DM, insulin secretion, insulin resistance, and β cell dysfunction: the story so far. J. Physiol. Biochem. 2020;76(4):485–502. doi: 10.1007/s13105-020-00760-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Agbu P., Carthew R.W. MicroRNA-mediated regulation of glucose and lipid metabolism. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2021;22(6):425–438. doi: 10.1038/s41580-021-00354-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zaiou M., El Amri H., Bakillah A. The clinical potential of adipogenesis and obesity-related microRNAs. Nutr. Metabol. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2018;28(2):91–111. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2017.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Andrés-León E., Núñez-Torres R., Rojas A.M. miARma-Seq: a comprehensive tool for miRNA, mRNA and circRNA analysis. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:25749. doi: 10.1038/srep25749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pala E., Denkçeken T. Differentially expressed circulating miRNAs in postmenopausal osteoporosis: a meta-analysis. Biosci. Rep. 2019;39(5) doi: 10.1042/BSR20190667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhu H., Leung S.W. Identification of microRNA biomarkers in type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis of controlled profiling studies. Diabetologia. 2015;58(5):900–911. doi: 10.1007/s00125-015-3510-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liang Y.Z., Li J.J., Xiao H.B., He Y., Zhang L., Yan Y.X. Identification of stress-related microRNA biomarkers in type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Diabetes. 2020;12(9):633–644. doi: 10.1111/1753-0407.12643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gholami M., Asgarbeik S., Razi F., Esfahani E.N., Zoughi M., Vahidi A., et al. Association of microRNA gene polymorphisms with Type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Res. Med. Sci. 2020;25:56. doi: 10.4103/jrms.JRMS_751_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gholaminejad A., Abdul Tehrani H., Gholami Fesharaki M. Identification of candidate microRNA biomarkers in diabetic nephropathy: a meta-analysis of profiling studies. J. Nephrol. 2018;31(6):813–831. doi: 10.1007/s40620-018-0511-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barrett T., Wilhite S.E., Ledoux P., Evangelista C., Kim I.F., Tomashevsky M., et al. NCBI GEO: archive for functional genomics data sets--update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41(Database issue):D991–D995. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zyprych-Walczak J., Szabelska A., Handschuh L., Górczak K., Klamecka K., Figlerowicz M., et al. The impact of normalization methods on RNA-seq data analysis. BioMed Res. Int. 2015;2015:621690. doi: 10.1155/2015/621690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maza E. In papyro comparison of TMM (edgeR), RLE (DESeq2), and MRN normalization methods for a simple two-conditions-without-replicates RNA-seq experimental design. Front. Genet. 2016;7:164. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2016.00164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abbas-Aghababazadeh F., Li Q., Fridley B.L. Comparison of normalization approaches for gene expression studies completed with high-throughput sequencing. PLoS One. 2018;13(10) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0206312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tam S., Tsao M.S., McPherson J.D. Optimization of miRNA-seq data preprocessing. Briefings Bioinf. 2015;16(6):950–963. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbv019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kolde R., Laur S., Adler P., Vilo J. Robust rank aggregation for gene list integration and meta-analysis. Bioinformatics. 2012;28(4):573–580. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yoon S., Baik B., Park T., Nam D. Powerful p-value combination methods to detect incomplete association. Sci. Rep. 2021;11(1):6980. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-86465-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rikke B.A., Wynes M.W., Rozeboom L.M., Barón A.E., Hirsch F.R. Independent validation test of the vote-counting strategy used to rank biomarkers from published studies. Biomarkers Med. 2015;9(8):751–761. doi: 10.2217/BMM.15.39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Koricheva J., Gurevitch J. Handbook of Meta-Analysis in Ecology and Evolution. 2013. Place of meta-analysis among other methods of research synthesis; pp. 3–13. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Davis S., Meltzer P.S. GEOquery: a bridge between the gene expression Omnibus (GEO) and BioConductor. Bioinformatics. 2007;23(14):1846–1847. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Robinson M.D., McCarthy D.J., Smyth G.K. edgeR: a Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics. 2010;26(1):139–140. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Robinson M.D., Oshlack A. A scaling normalization method for differential expression analysis of RNA-seq data. Genome Biol. 2010;11(3):R25. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-3-r25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bullard J.H., Purdom E., Hansen K.D., Dudoit S. Evaluation of statistical methods for normalization and differential expression in mRNA-Seq experiments. BMC Bioinf. 2010;11:94. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-11-94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Anders S., Huber W. Differential expression analysis for sequence count data. Genome Biol. 2010;11(10):R106. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-10-r106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Prada C., Lima D., Nakaya H. R package version 1.6.0; 2021. MetaVolcanoR: Gene Expression Meta-Analysis Visualization Tool. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chang L., Zhou G., Soufan O., Xia J. miRNet 2.0: network-based visual analytics for miRNA functional analysis and systems biology. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020;48(W1):W244–W251. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkaa467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Buchberger E., Bilen A., Ayaz S., Salamanca D., Matas de Las Heras C., Niksic A., et al. Variation in pleiotropic hub gene expression is associated with interspecific differences in head shape and eye size in Drosophila. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2021 doi: 10.1093/molbev/msaa335. msaa335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu H., Qu Y., Zhou H., Zheng Z., Zhao J., Zhang J. Bioinformatic analysis of potential hub genes in gastric adenocarcinoma. Sci. Prog. 2021;104(1) doi: 10.1177/00368504211004260. 368504211004260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kern F., Fehlmann T., Solomon J., Schwed L., Grammes N., Backes C., et al. miEAA 2.0: integrating multi-species microRNA enrichment analysis and workflow management systems. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020;48(W1):W521–W528. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkaa309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wander P.L., Enquobahrie D.A., Bammler T.K., Srinouanprachanh S., MacDonald J., Kahn S.E., Leonetti D., Fujimoto W.Y., Boyko E.J. Short Report: circulating microRNAs are associated with incident diabetes over 10 years in Japanese Americans. Sci. Rep. 2020;10(1):6509. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-63606-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Corona-Meraz F.I., Vázquez-Del Mercado M., Ortega F.J., Ruiz-Quezada S.L., Guzmán-Ornelas M.O., Navarro-Hernández R.E. Ageing influences the relationship of circulating miR-33a and miR- 33b levels with insulin resistance and adiposity. Diabetes Vasc. Dis. Res. 2019;16(3):244–253. doi: 10.1177/1479164118816659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dávalos A., Goedeke L., Smibert P., Ramírez C.M., Warrier N.P., Andreo U., et al. miR-33a/b contribute to the regulation of fatty acid metabolism and insulin signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2011;108(22):9232–9237. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1102281108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yang Y., Jiang H., Xiao L., Yang X. MicroRNA-33b-5p is overexpressed and inhibits GLUT4 by targeting HMGA2 in polycystic ovarian syndrome: an in vivo and in vitro study. Oncol. Rep. 2018;39(6):3073–3085. doi: 10.3892/or.2018.6375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Distel E., Barrett T.J., Chung K., Girgis N.M., Parathath S., Essau C.C., et al. miR33 inhibition overcomes deleterious effects of diabetes mellitus on atherosclerosis plaque regression in mice. Circ. Res. 2014;115(9):759–769. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.304164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zeinali F., Aghaei Zarch S.M., Jahan-Mihan A., Kalantar S.M., Vahidi Mehrjardi M.Y., Fallahzadeh H., et al. Circulating microRNA-122, microRNA-126-3p and microRNA-146a are associated with inflammation in patients with pre-diabetes and type 2 diabetes mellitus: a case control study. PLoS One. 2021;16(6) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0251697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lo W.Y., Peng C.T., Wang H.J. MicroRNA-146a-5p mediates high glucose-induced endothelial inflammation via targeting interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase 1 expression. Front. Physiol. 2017;8:551. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2017.00551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Belongie K.J., Ferrannini E., Johnson K., Andrade-Gordon P., Hansen M.K., Petrie J.R. Identification of novel biomarkers to monitor β-cell function and enable early detection of type 2 diabetes risk. PLoS One. 2017;12(8) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0182932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nührenberg T.G., Cederqvist M., Marini F., Stratz C., Grüning B.A., Trenk D., et al. Uncontrolled diabetes mellitus has No major influence on the platelet transcriptome. BioMed Res. Int. 2018;2018:8989252. doi: 10.1155/2018/8989252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hathaway Q.A., Pinti M.V., Durr A.J., Waris S., Shepherd D.L., Hollander J.M. Regulating microRNA expression: at the heart of diabetes mellitus and the mitochondrion. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2018;314(2):H293–H310. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00520.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sebastiani G., Guay C., Latreille M. Circulating noncoding RNAs as candidate biomarkers of endocrine and metabolic diseases. Internet J. Endocrinol. 2018;2018:9514927. doi: 10.1155/2018/9514927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tao W., Dong X., Kong G., Fang P., Huang X., Bo P. Elevated circulating hsa-miR-106b, hsa-miR-26a, and hsa-miR-29b in type 2 diabetes mellitus with diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterol. Res. Pract. 2016;2016:9256209. doi: 10.1155/2016/9256209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ouyang S., Tang R., Liu Z., Ma F., Li Y., Wu J. Characterization and predicted role of microRNA expression profiles associated with early childhood obesity. Mol. Med. Rep. 2017;16(4):3799–3806. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2017.7118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Abbasi A., Juszczyk D., van Jaarsveld C.H.M., Gulliford M.C. Body mass index and incident type 1 and type 2 diabetes in children and young adults: a retrospective cohort study. J. Endocr. Soc. 2017;1(5):524–537. doi: 10.1210/js.2017-00044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang H., Peng R., Wang J., Qin Z., Xue L. Circulating microRNAs as potential cancer biomarkers: the advantage and disadvantage. Clin. Epigenet. 2018;10:59. doi: 10.1186/s13148-018-0492-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Details of the studies (n = 34) that underwent primary screening.

Details of the studies (n = 8) that underwent secondary screening.

Details of the miRNA-gene associations network generated by miRNet 2.0.

Conserved and confident miRNA sets identified via functional analyses on miEAA 2.0.

Table: Details of the miRNA-disease associations revealed by enrichment analyses on miEAA 2.0.

Supporting evidence from contemporary studies with respect to the meta-signature of miRNAs identified in the current study.

Data Availability Statement

Data associated with this study has been deposited at the National Center for Biotechnology Information Gene Expression Omnibus (NCBI GEO) portal: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/