Abstract

Social desirability bias (a tendency to underreport undesirable attitudes and behaviors) may account, in part, for the notable ceiling effects and limited variability of patient-reported experience measures (PREMs) such as satisfaction, communication effectiveness, and perceived empathy. Given that there is always room for improvement for both clinicians and the care environment, ceiling effects can hinder improvement efforts. This study tested whether weighting of satisfaction scales according to the extent of social desirability can create a more normal distribution of scores and less ceiling effect. In a cross-sectional study 118 English-speaking adults seeking musculoskeletal specialty care completed 2 measures of satisfaction with care (one iterative scale and one 11-point ordinal scale), a measure of social desirability, and basic demographics. Normality of satisfaction scores was assessed using Shapiro-Wilk tests. After weighting for social desirability, scores on the iterative satisfaction scale had a more normal distribution while scores on the 11-point ordinal satisfaction scale did not. The ceiling effects in satisfaction decreased from 47% (n = 56) to 2.5% (n = 3) for the iterative scale, and from 81% (n = 95) to 2.5% (n = 3) for the ordinal scale. There were no differences in mean satisfaction when the social desirability was measured prior to completion of the satisfaction surveys compared to after. The observation that adjustment for levels of social desirability bias can reduce ceiling effects suggests that accounting for personal factors could help us develop PREMs with greater variability in scores, which may prove useful for quality improvement efforts.

Keywords: Clinician-patient relationship, social desirability, patient reported outcome measure, orthopedic surgery

Introduction

Measures that quantify concepts such as satisfaction, trust, communication effectiveness, and perceived empathy (patient-reported experience measures; PREMs) typically have strong ceiling effects and limited variability (1–). These characteristics of PREMs limit their ability to inform efforts to improve clinical practice and measure the impact of initiatives based on patient feedback (2,6). Although it's tempting to think that our care deserves top scores, it's unlikely that the clinician and unit have no room for improvement; this may indicate deficiencies in the current instruments that measure the patient experience.

It is possible that patients give us top scores because of social desirability, which is a tendency to underreport symptoms, habits, and behaviors that may be regarded as unfriendly or undesirable (7–). Patients tend to give high scores out of gratitude, respect, and deference, or perhaps out of fear that the doctor might become aware of their criticism. There might also be feelings of guilt or remorse when reporting less-than-perfect scores. This study tested whether adjusting PREMs for the extent of social desirability might reduce ceiling effects and increase the variability of scores to a more typical Gaussian distribution (7–).

In this cross-sectional survey of patients presenting for musculoskeletal specialty care, we asked: (1) Does weighting of satisfaction scales according to the extent of social desirability result in a normal distribution with fewer ceiling effects? (2) Does social desirability correlate with measures of satisfaction? (3) Which patient factors are associated with the extent of social desirability? (4) Is completion of a measure of social desirability before or after the satisfaction measures associated with a difference in mean scores?

Method

Study Design and Setting

All new adult (≥18 years) English-speaking patients seeking musculoskeletal care at one of four offices in an urban area in the United States were invited to participate between March and April 2021. Patients were approached by a research assistant who was not directly involved in care and completed surveys on a tablet device or phone in a private exam room without a researcher present. All patients who were not fluent in English, or were unable to provide verbal informed consent, and returning patients were excluded. The participants were informed that they could stop the questionnaires at any point; completion of the survey implied consent. All patients completed two measures of satisfaction with their office visit (an iterative satisfaction score and an 11-point ordinal scale measure of satisfaction), the short form of Marlowe-Crowne Social Desirability Scale to measure levels of social desirability, and basic demographics.

Sixty-four women (54%) and 54 men with an average age of 50 (standard deviation: 17) completed the questionnaires (Appendix 1). Out of 118 patients, 55 (47%) completed the satisfaction measure before the MCSDS-SF and 63 (53%) completed the satisfaction measure afterwards.

Measurements

The primary outcome variable was post-visit patient satisfaction, measured using the Guttman Satisfaction scale and an 11-point ordinal scale. The Guttman Satisfaction scale is iterative and branching, and allows for subsequent questions based on the response to the initial questions (12). The first item in the scale was “Today's visit was satisfactory.” Patients who answered ‘yes’ were given progressively more positive statements on which agreement was tested; the questionnaire ended with the superlative “Today's visit was more satisfying than I could imagine.” Patients who answered ‘no’ were presented with incrementally more negative statements. Higher scores indicated greater satisfaction with the office visit. The 11- point ordinal scale (numeric rating scale [NRS]) asked patients to rate their satisfaction on a scale of 0 to 10 (6). Higher scores indicated greater satisfaction. Additionally, patients completed the short form of the Marlowe-Crowne Social Desirability Scale (MCSDS-SF), which is a 13-item measure of individual-level social desirability, which was defined as the “need for subjects to respond in culturally sanctioned ways”(8,11,13). Subjects answer true or false to each statement resulting in a score between 0 and 13 with higher scores representing greater social desirability bias. An example item is: “It is sometimes hard for me to go on with my work if I am not encouraged.

Statistical Analysis

We explored various ways to account for the extent of social desirability in patient-reported experience measures. For instance, we sought bivariate associations (Spearman rank correlation) between the PREMs and the MCSDS-SF; we then subtracted the product of the MCSDS-SF total score and the Spearman correlation from the satisfaction score to calculate the adjusted score. Another method used was to multiply the satisfaction score by 10 and to subtract the product of the percentile rank on the MCSDS-SF and the Spearman rank order correlation. For example, assuming a Spearman rank correlation of 0.30, a perfect score of 100 among patients on the 80th percentile rank on the MCSDS-SF would equate to an adjusted score of 76 (100–80*0.30 = 76); being in the 100th percentile of MCSDS-SF would equate to 70. We used the Shapiro-Wilk test for normality after transformation and p-values were reported in addition to measures of skewness and kurtosis. Statistically significant P-values (<0.05) indicate a non-normal distribution. Additionally, we performed bivariate analysis seeking factors associated with the MCSDS-SF. For instance, we sought bivariate associations (Spearman rank correlation) between the PREMs and the MCSDS-SF; we then subtracted the product of the MCSDS-SF total score and the Spearman correlation from the satisfaction score to calculate the adjusted score (Adjustment Method A). Another method used was to multiply the satisfaction score by 10 and to subtract the product of the percentile rank on the MCSDS-SF and the Spearman rank order correlation (Adjustment Method B). Spearman rank order correlations were calculated for continuous variables; Mann-Whitney U tests and Kruskal-Wallis H tests were used for categorical variables, where appropriate. All variables with P < 0.10 were moved to multivariable negative binomial regression analysis. Alpha was set at 0.05.

An a priori sample size calculation indicated that a sample of 118 patients would yield 80% statistical power in a multivariable linear regression with ten predictors, with alpha set at 0.05 and a medium effect size of 0.15.

Results

Do Satisfaction Measures Weighted by Social Desirability Have a Gaussian Distribution?

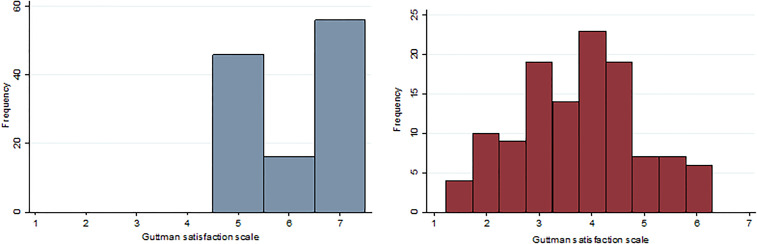

There were substantial ceiling effects and non-Gaussian distributions in both the Guttman satisfaction scale (skewness: −0.17; kurtosis: 1.2; Figure 1A) and the 11-point ordinal scale for satisfaction (skewness: −4.2; kurtosis: 26; Figure 1B). Weighted by to the extent of social desirability (Adjustment Method B), the Guttman satisfaction scale had a normal distribution (skewness: 0.080; kurtosis: 2.4; Shapiro Wilk test; P = 0.73; Figure 2A). The ceiling effects decreased from 47% (n = 56) to 2.5% (n = 3). Weighting (Adjustment Method A) did not lead to a Gaussian distribution in the 11-point ordinal scale for patient satisfaction after weighting by the extent of social desirability bias (skewness: −0.27; kurtosis: 4.0; Shapiro Wilk test: P = 0.019; Figure 2B). The ceiling effects decreased from 81% (n = 95) to 2.5% (n = 3).

Figure 1.

The Guttman satisfaction score (1A) and the satisfaction score weighted by the extent of social desirability (1B).

Figure 2.

The 11-point ordinal scale satisfaction score (2A) and the satisfaction score weighted by the extent of social desirability (2B).

Correlation Between Social Desirability and Satisfaction

There was no association between the extent of social desirability bias and the Guttman satisfaction score (ρ = 0.14; P = 0.12) or the 11-point ordinal rating of satisfaction (ρ = 0.01; P = 0.91).

Patient Factors Associated with the Extent of Social Desirability

In bivariate analysis, age, gender, education, annual household income, and commercial insurance were associated with social desirability bias (Appendix 2). Accounting for potential confounders in multivariable negative binomial regression analysis, lower social desirability was associated with younger age (Regression Coefficient [RC]: 0.0041; 95% Confidence Interval [CI] = 0.00034 to 0.0078; P = 0.033) and having an annual household income between $100,000 and $149,999 (RC: −0.29; 95% CI: −0.50 to −0.089; P = 0.005) and more than $150,000 (RC = −0.22; 95% CI: −0.42 to −0.032; P = 0.022; Table 1).

Table 1.

Negative Binomial Regression Analysis of Patient Factors Associated with the Degree of Social Desirability (Marlowe-Crowne Social Desirability Scale - Short Form).

| Variables | Regression Coefficient (95% Confidence Interval) | Standard Error | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.0041 (0.00034 to 0.0078) | 0.0019 | 0.033 |

| Gender | |||

| Woman | reference value | ||

| Man | −0.085 (−0.21 to 0.043) | 0.066 | 0.19 |

| Annual household income* | |||

| Less than $30,000 | reference value | ||

| Between $30,000 and $49,999 | −0.13 (−0.36 to 0.11) | 0.12 | 0.29 |

| Between $50,000 and $74,999 | −0.085 (−0.30 to 0.13) | 0.11 | 0.43 |

| Between $75,000 and $99,999 | −0.20 (−0.42 to 0.0015) | 0.11 | 0.067 |

| Between $100,000 and $149,999 | −0.29 (−0.50 to −0.089) | 0.10 | 0.005 |

| More than $150,000 | −0.22 (−0.42 to −0.032) | 0.098 | 0.022 |

Bold indicates statistical significance, P < 0.05. *Insurance status and education were dropped from the final model because they were associated with annual household income.

Difference in Patient Satisfaction Scores Between Patients who Completed the Social Desirability Instrument Before or After the Satisfaction Measures

There were no differences in satisfaction scores between patients who completed the social desirability bias instrument before or after the satisfaction measures, rated on Guttman scale (median: 6 [5–7] vs. 7 [5–7]; P = 0.14) or the 11-point ordinal measure (median: 10 [10–10] vs. 10 [10–10]; P = 0.16).

Discussion

The ability of patient-reported experience measures (PREMs) to inform efforts to improve practice is restricted by large ceiling effects and limited variability (non-Gaussian distribution) (2,4). These ceiling effects are more likely to indicate deficiencies in the current PREMs than perfect clinical encounters. A mounting body of evidence suggests that social desirability is an important factor associated with underreporting of undesirable symptoms, traits, and attitudes (4,9,10), and this may be associated with the limited variability in PREMs. We performed a cross-sectional study among patients seeking musculoskeletal specialty care to test if weighting PREMs for social desirability could limit ceiling effects and result in a more Gaussian distribution. We found that an iterative measure of satisfaction had a normal distribution after weighting for social desirability, but not the 11-point ordinal scale. The findings that (1) there was no relationship between social desirability and satisfaction, (2) that personal factors were associated with the extent of social desirability, and (3) that measuring social desirability had no effect on ratings of satisfaction all support the independence of social desirability and its potential use to improve measurement of the patient experience.

This study should be read in light of several limitations. First, most patients presented at private practice orthopedic clinics in an urban setting and were relatively affluent and educated, limiting the generalizability of this patient population. However, given the diversity of social desirability scores in the sample, the statistical correlations are likely reproducible in other care settings. Second, current PREMs have high ceiling effects and limited variability, making it more difficult to study the association between the extent of social desirability and the satisfaction with an office visit. Given the different influence of weighting social desirability for the Guttman and the 11-point ordinal measure, it may be easier to study the influence of social desirability bias if we can develop experience measures with less ceiling effect. A more Gaussian distribution (greater variability) facilitates identification of factors associated with that variability. When a continuous or ordinal variable has a high ceiling effect, it acts more as a categorical variable and information important information may be lost. Third, some might wonder about adjusting satisfaction scores for social desirability when there was not a direct correlation. But the relationship may be non-linear, particularly given the ceiling effects in satisfaction scores. Finally, the Guttman (iterative) satisfaction rating is relatively novel, and our findings can be considered more reliable if reproduced by others in different care settings. The lower ceiling effects in this measure suggest iterative measures of satisfaction could be a worthwhile avenue for future investigations.

The finding that both the iterative satisfaction scale and the 11-point ordinal scale had notable ceiling effects but weighting for the impact of social desirability bias created a more Gaussian distribution for the iterative satisfaction score suggests that adjusting for social desirability can improve the utility of information obtained from PREMs. One study of 591 cocaine and opioid users in Baltimore documented an association between greater social desirability and (1) a lower likelihood of reporting recent drug use (measured on a 10-point ordinal scale) and (2) greater perceived social stigma (measured on a 17-point scale), accounting for symptoms of depression (4). Another study of 1,644 adolescents in Northwestern Burkina Faso (14) randomized people to a conventional verbal response arm (high social desirability bias environment) and a nonverbal response arm (low social desirability bias environment) and found significantly higher levels of reported sexual assault and forced sex in the non-verbal response (14). These findings suggest that social desirability could be part of the explanation of ceiling effects and nonparametric distributions of the current PREMs, but there are a variety of other modifiable and non-modifiable patient factors that may explain why patients are likely to give us top scores (15–23). Although it may be flattering for physicians to receive top scores, it may contribute to a false sense that there is no further opportunity for improvement. Our hope is that continued research in this area will help develop instruments that are more sensitive in detecting differences in satisfaction so that PREMs can become valuable instruments for quality improvement and scientific research.

The observation that there was no association between social desirability bias and the iterative or ordinal satisfaction scores can be considered provisional as it may be due to the large ceiling effects and limited variation, which restricts the ability to detect correlations. It’s also possible that this may be a reproducible finding as there is no a priori reason for social desirability to be correlated with measures of the patient's experience of care. Another study of two measures with high ceiling effects—a measure of resilience and a measure of social desirability among family caregivers of children with cancer faced a similar dilemma (18). If we want to measure factors that people tend to rate very highly such as satisfaction with care, perceived clinician empathy, resilience, and social desirability, we are going to need to develop better measures that can capture more of the existing variability in these phenomena. Without such measures we cannot be sure if they are or are not inter-related, and we cannot test for complex, non-linear relationships.

The observation that lower social desirability had modest independent associations with younger age and household income of less than $100,000 suggests that it may be relatively independent of personal factors. The findings in other studies are also modest and inconsistent: One study of 857 patients who completed a cancer screening instrument identified white race and education status of 4 years of college or higher as associated with lower social desirability, with no associations with age and gender (19). Another study among 751 adults living with HIV in Uganda found associations between social desirability and self-reported alcohol use, but not with age or gender (20). Given the absence of factors that are associated with greater social desirability across different populations and settings, we deem social desirability as relatively independent of demographic factors, and therefore a potentially useful adjunct to the measurement of the patient experience.

The observation that there is no difference in satisfaction scores between patients who completed the social desirability instrument before or after the satisfaction measures suggests that its measurement has little influence on measurements of experience (PREMs). Three hundred one undergraduate students enrolled in a psychology course identified associations of increased reports of alcohol use with lower social desirability bias and greater religiosity, which was made greater (primed) by consideration of religiosity prior to reporting alcohol use (14). Our findings demonstrate that such priming effects do not occur when patients are first asked questions that measure their tendency to underreport negative attitudes (social desirability), perhaps because the questions in the scale were relatively abstract and did not have an apparent connection with ratings of satisfaction.

Conclusion

We performed a cross-sectional survey of patients seeking musculoskeletal specialty care and found that accounting for the extent of social desirability has the potential to reduce or eliminate ceiling effects in PREMs, which can make them better tools for research and quality improvement. These findings may help guide future research aimed at developing PREMs with a Gaussian distribution. Future investigations can test if weighting new experience measures according to social desirability can lead to the more meaningful measurement of patient satisfaction, which can help develop interventions to improve the patient-physician relationship, or test the relative influence of treatment on the patient experience.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-jpx-10.1177_23743735221079144 for Does Adjusting for Social Desirability Reduce Ceiling Effects and Increase Variation of Patient-Reported Experience Measures? by Megan A. Badejo, Sina Ramtin, Ayane Rossano, David Ring, Karl Koenig and Tom J Crijns in Journal of Patient Experience

Supplemental material, sj-docx-2-jpx-10.1177_23743735221079144 for Does Adjusting for Social Desirability Reduce Ceiling Effects and Increase Variation of Patient-Reported Experience Measures? by Megan A. Badejo, Sina Ramtin, Ayane Rossano, David Ring, Karl Koenig and Tom J Crijns in Journal of Patient Experience

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: David Ring https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5947-5316

Ethical Approval: Approval was obtained from Institutional Review Board, The University of Texas at Austin, Texas for this cross-sectional survey (STUDY00000142).

Statement of Human and Animal Rights: All procedures in this study were conducted in accordance with the Institutional Review Board, The University of Texas at Austin, Texas approved protocols.

Statement of Informed Consent: Verbal informed consent was obtained from the patients for their anonymized information to be published in this article.

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1.Ryan TP. Sample size determination and power. 27 June 2013. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Hoboken, NJ, USA. 10.1002/9781118439241 [DOI]

- 2.Leite WL, Nazari S. Marlowe-Crowne social desirability scale. In: Zeigler-Hill V., Shackelford T. (eds) Encyclopedia of Personality and Individual Differences. Springer, Cham., 2017, 1-3. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burke MA, Carman KG. You can be too thin (but not too tall): social desirability bias in self-reports of weight and height. Economics And Human Biology. 2017;27(Pt A):198-222. 10.1016/j.ehb.2017.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Widmar NJO, Byrd ES, Dominick SR, Wolf CA, Acharya L. Social desirability bias in reporting of holiday season healthfulness. Preventive Medicine Reports. 2016;4(1):270-6. 10.1016/j.pmedr.2016.06.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reynolds WM. Development of reliable and valid short forms of the Marlowe-Crowne Social Desirability Scale. J Clin Psychol. 1982;38(1):119-125. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schoch AH, Raynor HA. Social desirability, not dietary restraint, is related to accuracy of reported dietary intake of a laboratory meal in females during a 24-h recall. Eating Behaviors. 2012;13(1):78-81. 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2011.11.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tachibana S, Muratsu H, Tsubosaka M, Maruo A, Miya H, Kuroda R, et al. Evaluation of consistency of patient-satisfaction score in the 2011 knee society score to other patient-reported outcome measures. Journal Of Orthopaedic Science : Official Journal Of The Japanese Orthopaedic Association. Epub ahead of print 2021. 10.1016/j.jos.2021.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DeVylder JE, Hilimire MR. Screening for psychotic experiences: social desirability biases in a non-clinical sample. Early Intervention In Psychiatry. 2015;9(4):331-4. 10.1111/eip.12161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rodriguez LM, Neighbors C, Foster DW. Priming effects of self-reported drinking and religiosity. Psychology Of Addictive Behaviors : Journal Of The Society of Psychologists in Addictive Behaviors. 2014;28(1):1-9. 10.1037/a0031828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goh GS, Khow YZ, Tay DK, Lo NN, Yeo SJ, Liow MHL. Preoperative mental health influences patient-reported outcome measures and satisfaction after revision total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2021;36(8):2878-86. 10.1016/j.arth.2021.03.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rao A, Tobin K, Davey-Rothwell M, Latkin CA. Social desirability bias and prevalence of sexual HIV risk behaviors Among people Who Use drugs in Baltimore, maryland: implications for identifying individuals prone to underreporting sexual risk behaviors. AIDS And Behavior. 2017;21(7):2207-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harling G, Bountogo M, Sié A, Bärnighausen T, Lindstrom DP. Nonverbal response cards reduce socially desirable reporting of violence Among adolescents in rural Burkina Faso: a randomized controlled trial. The Journal of Adolescent Health. 2021; 68(5):914-21. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.09.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Versluijs Y, Brown LE, Rao M, Gonzalez AI, Driscoll MD, Ring D. Factors associated With patient satisfaction measured using a guttman-type scale. Journal Of Patient Experience. 2020;7(6):1211-8. 10.1177/2374373520948444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nguyen C, Kortlever JTP, Gonzalez AI, Ring D, Brown LE, Somogyi JR. Attempts to limit censoring in measures of patient satisfaction. Journal of Patient Experience. 2020;7(6):1094-100. 10.1177/2374373520930468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nixon DC, Zhang C, Weinberg MW, Presson AP, Nickisch F. Relationship of press ganey satisfaction and PROMIS function and pain in foot and ankle patients. Foot Ankle Int. 2020; 41(10):1206-11. 10.1177/1071100720937013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Keulen MHF, Teunis T, Kortlever JTP, Vagner GA, Ring D, Reichel LM. Measurement of perceived physician empathy in orthopedic patients. Journal Of Patient Experience. 2020;7(4):600-6. 10.1177/2374373519875842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leng C-H, Huang H-Y, Yao G. A social desirability item response theory model: retrieve-deceive-transfer. Psychometrika. 2020;85(1):56-74. 10.1007/s11336-019-09689-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Toledano-Toledano F, Rubia JM de la, Broche-Pérez Y, Domínguez-Guedea MT, Granados-García V. The measurement scale of resilience among family caregivers of children with cancer: a psychometric evaluation. BMC Public Health. 2019; 19(1):164. 10.1186/s12889-019-7512-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Latkin CA, Edwards C, Davey-Rothwell MA, Tobin KE. The relationship between social desirability bias and self-reports of health, substance use, and social network factors among urban substance users in Baltimore, maryland. Addictive Behaviors. 2017;73(1):133-6. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.05.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Parrish RC, 2nd, Menendez ME, Mudgal CS, Jupiter JB, Chen NC, Ring D. Patient satisfaction and its relation to perceived visit duration With a hand surgeon. The Journal of hand surgery. 2016;41(2):254-7. 10.1016/j.jhsa.2015.11.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martinez JR, Nakonezny PA, Batty M, Wells J. The dimension of the press ganey survey most important in evaluating patient satisfaction in the academic outpatient orthopedic surgery setting. Orthopedics. 2019;42(4):198-204. 10.3928/01477447-20190625-03 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Etier BE Jr., Orr SP, Antonetti J, Thomas SB, Theiss SM. Factors impacting press ganey patient satisfaction scores in orthopedic surgery spine clinic. The Spine Journal : Official Journal of the North American Spine Society. 2016;16(11):1285-9. 10.1016/j.spinee.2016.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abtahi AM, Presson AP, Zhang C, Saltzman CL, Tyser AR. Association between orthopaedic outpatient satisfaction and Non-modifiable patient factors. Journal Of Bone & Joint Surgery, American Volume. 2015;97(13):1041-8. 10.2106/JBJS.N.00950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-jpx-10.1177_23743735221079144 for Does Adjusting for Social Desirability Reduce Ceiling Effects and Increase Variation of Patient-Reported Experience Measures? by Megan A. Badejo, Sina Ramtin, Ayane Rossano, David Ring, Karl Koenig and Tom J Crijns in Journal of Patient Experience

Supplemental material, sj-docx-2-jpx-10.1177_23743735221079144 for Does Adjusting for Social Desirability Reduce Ceiling Effects and Increase Variation of Patient-Reported Experience Measures? by Megan A. Badejo, Sina Ramtin, Ayane Rossano, David Ring, Karl Koenig and Tom J Crijns in Journal of Patient Experience