Key Points

Question

What is the trend of general surgery residency application, matriculation, and graduation for Black trainees over time?

Findings

This cohort study uses data from the Association of American Medical Colleges general surgery residency and highlights the persistent underrepresentation of Black trainees over the past 13 years. There has been little progress in retaining Black women matriculants and graduates, while there has been a decline in Black men matriculating and graduating from general surgery residency.

Meaning

Identifying factors that address intersectionality and contribute to the successful recruitment and retention of Black trainees in general surgery residency is critical for achieving racial and sex equity.

This cohort study evaluates the trend of general surgery residency application, matriculation, and graduation rates for Black trainees compared with their racial and ethnic counterparts over time.

Abstract

Importance

The lack of underrepresented in medicine physicians within US academic surgery continues, with Black surgeons representing a disproportionately low number.

Objective

To evaluate the trend of general surgery residency application, matriculation, and graduation rates for Black trainees compared with their racial and ethnic counterparts over time.

Design, Setting, and Participants

In this nationwide multicenter study, data from the Electronic Residency Application Service (ERAS) for the general surgery residency match and Graduate Medical Education (GME) surveys of graduating general surgery residents were retrospectively reviewed and stratified by race, ethnicity, and sex. Analyses consisted of descriptive statistics, time series plots, and simple linear regression for the rate of change over time. Medical students and general surgery residency trainees of Asian, Black, Hispanic or Latino of Spanish origin, White, and other races were included. Data for non-US citizens or nonpermanent residents were excluded. Data were collected from 2005 to 2018, and data were analyzed in March 2021.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Primary outcomes included the rates of application, matriculation, and graduation from general surgery residency programs.

Results

Over the study period, there were 71 687 applicants, 26 237 first-year matriculants, and 24 893 graduates. Of 71 687 applicants, 24 618 (34.3%) were women, 16 602 (23.2%) were Asian, 5968 (8.3%) were Black, 2455 (3.4%) were Latino, and 31 197 (43.5%) were White. Women applicants and graduates increased from 29.4% (1178 of 4003) to 37.1% (2293 of 6181) and 23.5% (463 of 1967) to 33.5% (719 of 2147), respectively. When stratified by race and ethnicity, applications from Black women increased from 2.2% (87 of 4003) to 3.5% (215 of 6181) (P < .001) while applications from Black men remained unchanged (3.7% [150 of 4003] to 4.6% [284 of 6181]). While the matriculation rate for Black women remained unchanged (2.4% [46 of 1919] to 2.3% [52 of 2264]), the matriculation rate for Black men significantly decreased (3.0% [57 of 1919] to 2.4% [54 of 2264]; P = .04). Among Black graduates, there was a significant decline in graduation for men (4.3% [85 of 1967] to 2.7% [57 of 2147]; P = .03) with the rate among women remaining unchanged (1.7% [33 of 1967] to 2.2% [47 of 2147]).

Conclusions and Relevance

Findings of this study show that the underrepresentation of Black physicians at every stage in surgical training pipeline persists. Black men are especially affected. Identifying factors that address intersectionality and contribute to the successful recruitment and retention of Black trainees in general surgery residency is critical for achieving racial and ethnic as well as gender equity.

Introduction

Diversity, equity, and inclusion within academic surgery are essential as academic medical centers serve patient populations that reflect the changing demographic characteristics of the US.1,2,3,4 However, the representation of racially and ethnically underrepresented in medicine (UIM) general surgeons remains low owing to significant disparities in the proportion of UIM students applying, matriculating, and subsequently graduating from US surgical residency training programs. To our knowledge, the effects of intersectional identities, such as race and ethnicity and gender (for example being Black and a woman), on these disparities have not been examined in academic surgery. In fact, while there has been an increase in the medical school graduation rate for UIM women specifically, general surgery graduation rates for Black women remain disproportionately low compared with their White and Asian women counterparts.5 Consequently, there are few UIM women in academic surgery, with Black women holding a disproportionately smaller number of leadership positions in general surgery and all the surgical subspecialties.1,4 Black women represent less than 1% of academic surgical faculty compared with 49% White men and 14.5% White women.4 Similarly, Black men are underrepresented at all surgical academic ranks.6 The reason for the disparity is multifactorial,7 including persistently low numbers of Black medical school applicants and matriculants over time.8 The objective of this study was to examine Black women and Black men general surgery applicants, matriculants, and graduates over time compared with their racial and ethnic counterparts to develop strategies that will eliminate the disparity between UIM representation in the general population and UIM representation in surgery to ultimately improve patient outcomes.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective review of the 2005 to 2018 Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) roster of Electronic Residency Application Service (ERAS) general surgery residency applicants (categorical and preliminary), first-year general surgery matriculants, and Graduate Medical Education (GME) track survey of graduates of Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education–accredited general surgery residency programs. Not all Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education–accredited general surgery residency programs participated in the GME Track Residency Survey. Prior to 2007, response rates were estimated from 68.6% to 82.1%. Since 2007, response rates have ranged from 88.2% to 94.1%. Data were stratified using race and ethnicity as well as gender as intersectional variables defined by the AAMC, with one exception: American Indian and Alaskan Native, Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander and multiple, other, and unknown races were all combined into a single group (other/unknown race). Although other/unknown race was included in the total number of applicants, matriculants, and graduates, racial and ethnic demographic data were specifically evaluated for Asian, Black, Hispanic or Latino of Spanish origin, and White races. Non-US citizens or nonpermanent residents for ERAS applicants, general surgery matriculants, and graduates were excluded. The study was deemed exempt by the Institutional Review Board of New York University Grossman School of Medicine because deidentified data were retrospectively reviewed.

Statistical analysis consisted of descriptive statistics, with paired t tests to compare the proportional representation of Black women with Asian, Latina, and White women and similarly of Black men with their racial and ethnic counterparts. Trends over time for each of the 4 pipeline cohorts—(1) ERAS application, (2) first-year matriculation, (3) graduation, and (4) attrition—were stratified by race and ethnicity as well as gender, subdivided into 8 intersectional groups, and analyzed with simple linear regression. Each of the 8 intersectional groups was used to independently calculate the average rate of change over the study period. Paired t tests were used for pairwise comparisons and one-way analysis of variance was used for comparison of the 4 groups. Significance was set at P < .05, and all P values were 2-tailed. Analyses were conducted using Excel version 14.4.2 (Microsoft) and R version 4.1.1 (The R Foundation).

Results

General Surgery Residency Applicants

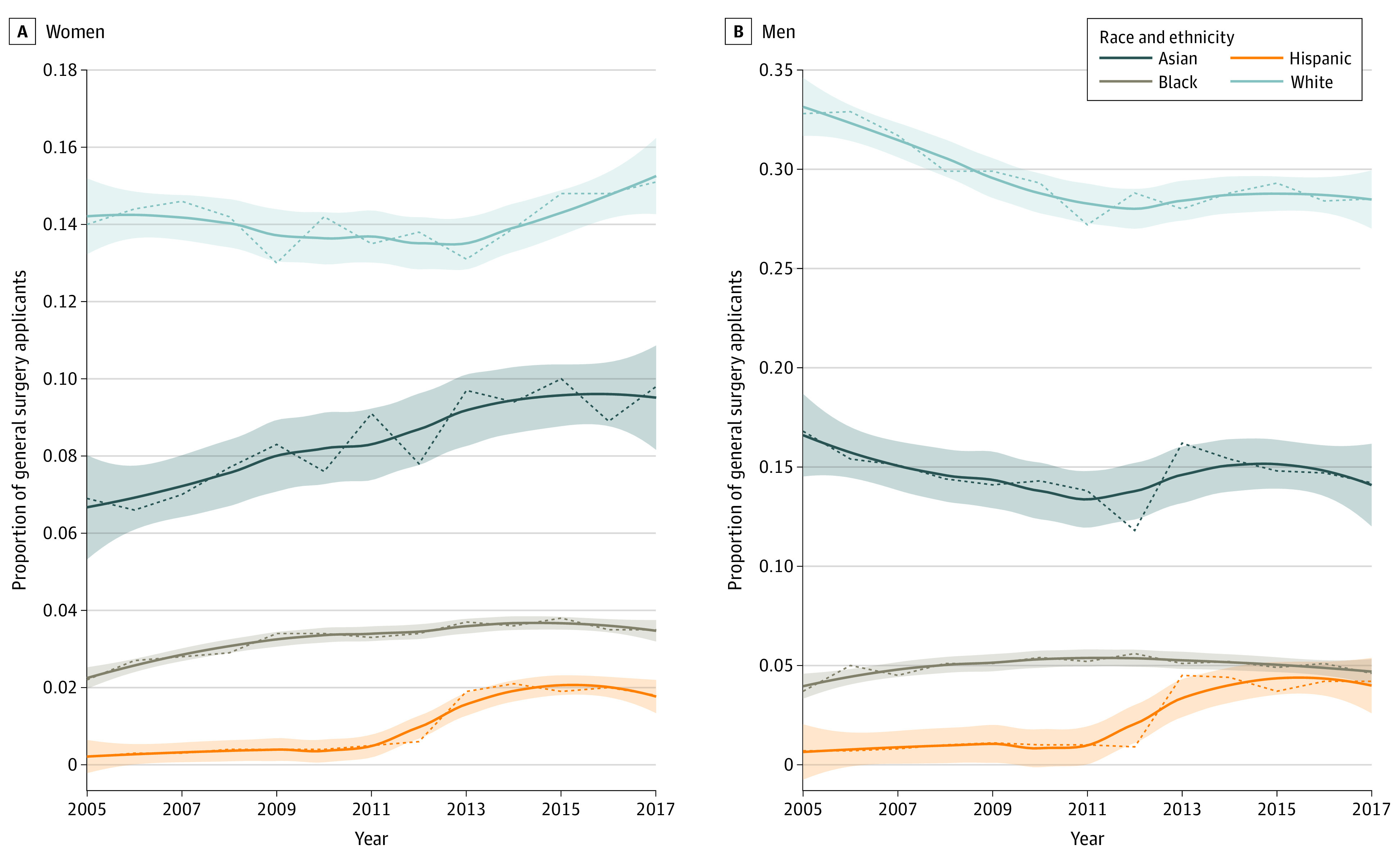

Over the study period, there were 71 687 applicants, 26 237 first-year matriculants, and 24 893 graduates. Of 71 687 applicants, 24 618 (34.3%) were women, 16 602 (23.2%) were Asian, 5968 (8.3%) were Black, 2455 (3.4%) were Latino, and 31 197 (43.5%) were White (Table). When women applicants were stratified by race and ethnicity, 6111 (8.5%) were Asian, 2378 (3.3%) were Black, 769 (1.1%) were Latina, and 10 107 (14.1%) were White. Black women had fewer applications (3.3%) compared with White women (14.1%) and Asian women (8.5%) but more applications compared with Latina women (1.0%; P < .001; Figure 1A). When evaluated over time, ERAS applications saw a significant yearly increased rate of 0.10% among Black women (2.2% [87 of 4003] to 3.5% [215 of 6181]; P < .001), 0.18% among Latina women (0.2% [7 of 4003] to 1.8% [113 of 6181]; P < .001), and 0.27% among Asian women (6.9% [276 of 4003] to 9.8% [604 of 6181]; P < .001); however, for White women, this rate remained unchanged (14.0% [561 of 4003] to 15.1% [934 of 6181]; P = .37).

Table. 2005 to 2018 Association of American Medical Colleges Roster of Electronic Residency Application Service General Surgery Residency Applicants (Categorical and Preliminary), First-year General Surgery Matriculants, and Graduate Medical Education Track Graduates of Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education–Accredited General Surgery Residency Programs.

| Populationa | Race, No. (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asian | Black | Hispanic | White | Other/unknownb | Total | |

| ERAS applicants | ||||||

| Men | 10 487 (14.6) | 3588 (5.0) | 1683 (2.2) | 21 086 (29.4) | 10 180 (14.2) | 47 024 (65.6) |

| Women | 6111 (8.5) | 2378 (3.3) | 769 (1.0) | 10 107 (14.1) | 5253 (7.3) | 24 618 (34.3) |

| Total | 16 602 (23.2) | 5968 (8.3) | 2455 (3.4) | 31 197 (43.5) | 15 465 (21.6) | 71 687 |

| First-year matriculants | ||||||

| Men | 3007 (11.5) | 824 (3.1) | 587 (2.2) | 10 947 (41.7) | 1721 (6.6) | 17 086 (65.1) |

| Women | 1761 (6.7) | 642 (2.4) | 289 (1.1) | 5448 (20.7) | 1011 (3.9) | 9151 (34.9) |

| Total | 4768 (18.2) | 1466 (5.6) | 876 (3.3) | 16 395 (62.5) | 2732 (10.4) | 26 237 |

| Graduates | ||||||

| Men | 3270 (13.1) | 939 (3.8) | 624 (2.5) | 10 914 (43.8) | 1651 (6.6) | 17 398 (69.9) |

| Women | 1534 (6.2) | 616 (2.5) | 228 (0.9) | 4325 (17.4) | 792 (3.2) | 7495 (30.1) |

| Total | 4804 (19.3) | 1555 (6.3) | 852 (3.4) | 15 239 (61.2) | 2443 (9.8) | 24 893 |

Abbreviation: ERAS, Electronic Residency Application Service.

Unknown gender not shown.

Other/unknown race includes those indicating American Indian and Alaskan Native race, Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander race, and multiple, other, and unknown race.

Figure 1. Yearly Proportion of General Surgery Applicants by Race and Ethnicity With Overlying Loess Trend in Women and Men.

The shaded area indicates the 95% CI.

Similarly, when men applicants were stratified by race and ethnicity, 10 487 (14.6%) were Asian, 3588 (5.0%) were Black, 1683 (2.2%) were Latino, and 21 086 (29.4%) were White. Black men had fewer applications (5.0%) compared with Asian men (14.6%) and White men (29.4%) but more compared with Latino men (2.2%; P < .001; Figure 1B). When evaluated over time, ERAS applications increased significantly at a yearly rate of 0.37% among Latino men (0.7% [29 of 4003] to 4.2 [257 of 6181]%; P < .001) and decreased at a yearly rate of 0.36% among White men (32.8% [1311 of 4003] to 28.5% [1759 of 6181], P = .001) but saw no change noted among Black men (3.7% [150 of 4003] to 4.6% [284 of 6181]; P = .23) and Asian men (16.8% [671 of 4003] to 14.2% [875 of 6181]; P = .37).

General Surgery Residency First-year Matriculants

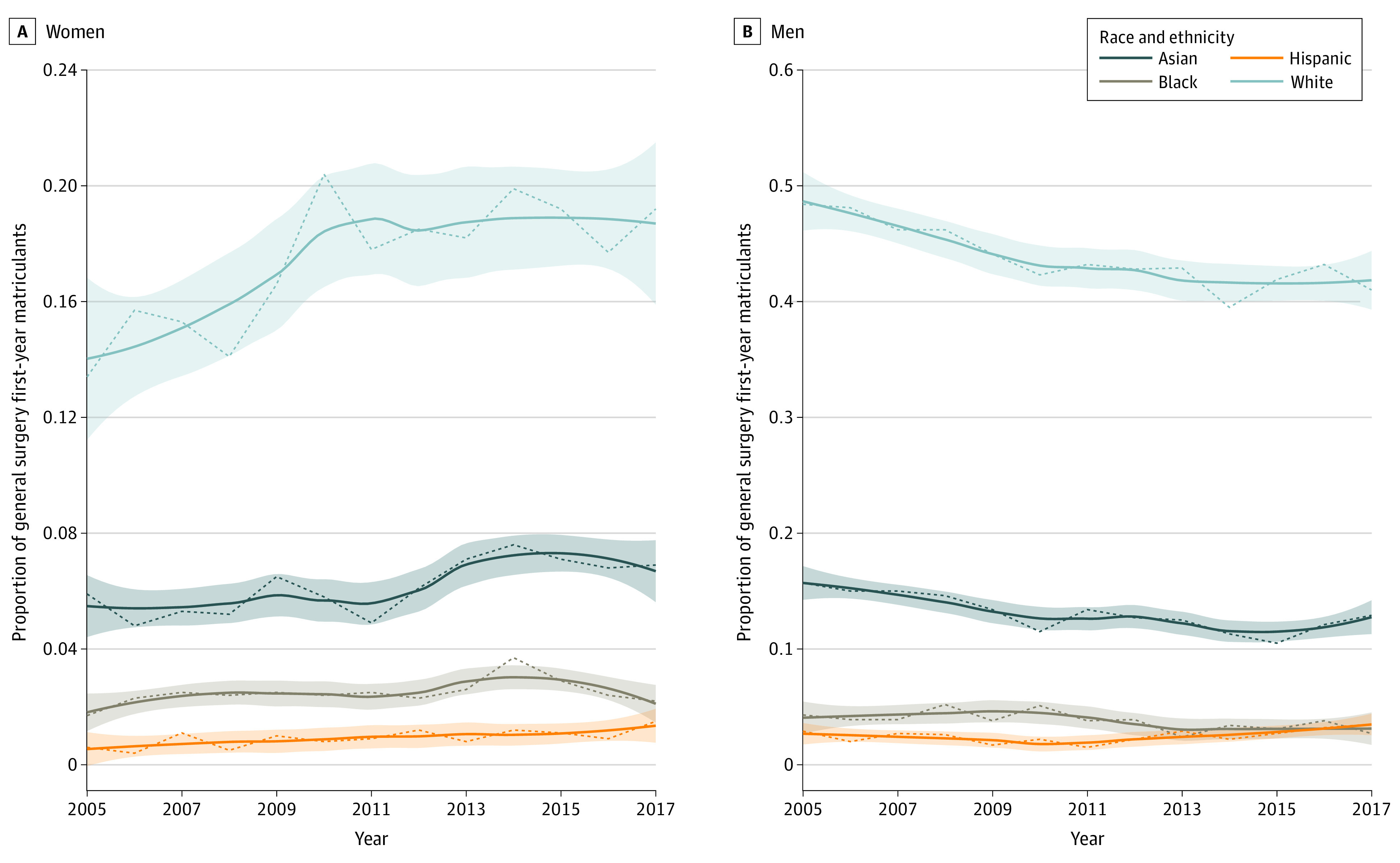

Of the 26 237 first-year matriculants to general surgery residency, 17 086 (65.1%) were men and 9151 (34.9%) were women. A total of 4768 (18.2%) were Asian, 1466 (5.6%) were Black, 876 (3.3%) were Latino, and 16 395 (62.5%) were White (Table). When first-year women matriculants were stratified by race and ethnicity, 1761 (6.7%) were Asian, 642 (2.4%) were Black, 289 (1.1%) were Latina, and 5448 (20.8%) were White. Black women made up a significantly smaller proportion of first-year matriculants (2.4%) compared with Asian women (6.7%) and White women (20.8%) but larger proportion than Latina women (1.1%; P < .001; Figure 2A). When evaluating the first-year matriculation rate over time, Latina women had a significant yearly increased rate of 0.12% (0.4% [81 of 1919] to 1.6% [37 of 2264]; P < .001); Asian women had a significant yearly increased rate of 0.15% (5.4% [104 of 1919] to 8.1% [184 of 2264]; P = .01) and White women had a significant yearly increased rate of 0.26% (19.1% [366 of 1919] to 21.8% [494 of 2264]; P = .006). The matriculation rate for Black women remained unchanged over the study period (2.4% [46 of 1919] to 2.3% [52 of 2264]; P = .10).

Figure 2. Yearly Proportion of General Surgery First-year Matriculants by Race and Ethnicity With Overlying Loess Trend in Women and Men.

The shaded area indicates the 95% CI.

Among the men first-year matriculants, 3007 (11.5%) were Asian, 824 (3.1%) were Black, 587 (2.2%) were Latino, and 10 947 (41.7%) were White. Black men had less representation (3.1%) compared with Asian men (11.5%) and White men (41.7%), but representation was higher compared with Latino men (2.2%; P < .001; Figure 2B). When evaluating the first-year matriculation rate over time, Latino men had a significant yearly increase of 0.22% (1.2% [23 of 1919] to 3.0% [68 of 2264]; P < .001), whereas Black and White men had a significant yearly decreased rate of 0.01% (3.0% [57 of 1919] to 2.4% [54 of 2264]; P = .04) and 0.41% (45.0% [864 of 1919] to 37.9% [858 of 2264]; P = .002), respectively. The matriculation rate for Asian men remained unchanged (13.7% [262 of 1919] to 11.6% [262 of 2264]; P = .06).

General Surgery Residency Graduates

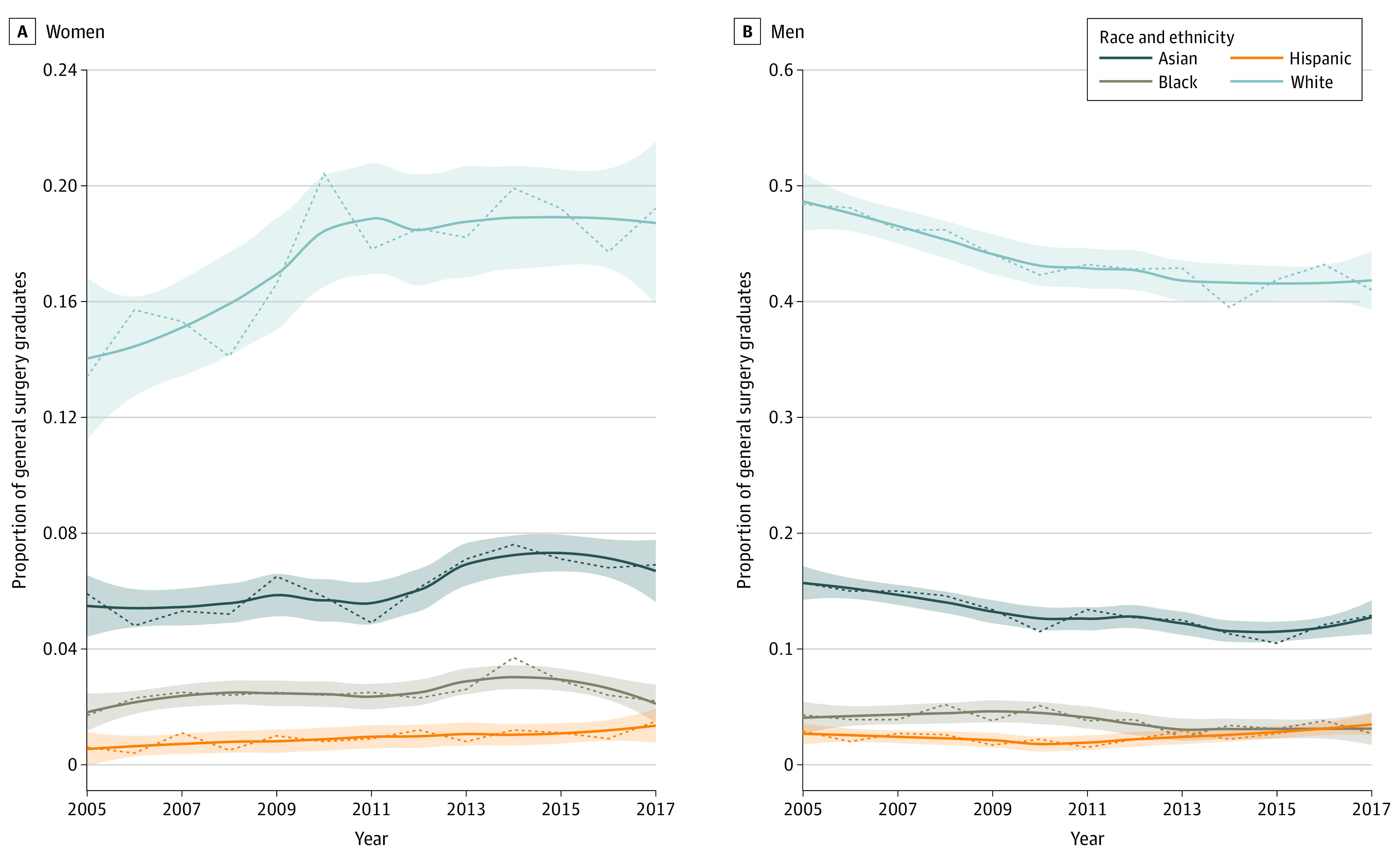

Of the 24 893 general surgery graduates, 17 398 (70.5%) were men, and 7495 (30.4%) were women. A total of 4804 (19.3%) were Asian, 1555 (6.3%) were Black, 852 (3.4%) were Latino, and 15 239 (61.2%) were White (Table). Further analysis of the women graduates revealed that 1534 (6.2%) were Asian, 616 (2.5%) were Black, 228 (0.9%) were Latina, and 4325 (17.4%) were White. Black women represented a smaller percentage of graduates (2.5%) compared with Asian graduates (6.2%) and White graduates (17.4%) but higher compared with Latina women (0.9%; P < .001; Figure 3A). Although the overall number of women graduating in general surgery increased by 55.3% (463 to 719), when stratified by race and ethnicity, the graduation rate among Black women remained low and unchanged (1.7% [33 of 1967] to 2.2% [47 of 2147]; P = .14). In contrast, the percent of graduating Asian and White women residents increased at a yearly rate of 0.2% (5.9% [117 of 1967] to 6.9% [148 of 2147]; P = .004) and 0.4% (13.4% [264 of 1967] to 19.2% [413 of 2147]; P = .002), respectively. The percentage of Latina women graduating also increased (0.6% [11 of 1967] to 1.5% [32 of 2147]; P = .006), although this increase occurred at a lower yearly rate of 0.06% (P < .001) compared with Asian and White women.

Figure 3. Yearly Proportion of General Surgery Graduates by Race and Ethnicity With Overlying Loess Trend in Women and Men.

The shaded area indicates the 95% CI.

Further analysis of the men graduates revealed that 3270 (13.1%) were Asian, 939 (3.8%) were Black, 624 (2.5%) were Latino, and 10 914 (43.8%) were White. Black men represented a smaller percentage of graduates (3.8%) compared with Asian men (13.1%) and White men (43.8%) but higher compared with Latino men (2.5%; P < .001; Figure 3B). In evaluating the graduation rate for men, trend analysis revealed a significant decline for Asian men (15.7% [309 of 1967] to 12.9% [277 of 2147]; P < .001), Black men (4.3% [85 of 1967] to 2.7% [57 of 2147]; P = .03), and White men (48.4% [952 of 1967] to 41.0% [880 of 2147]; P < .001), which occurred at a yearly rate of 0.3%, 0.1%, and 0.6%, respectively. The percentage of Latino men graduating, however, remained unchanged (2.9% [57 of 1967] to 3.5% [75 of 2147]; P = .18).

Attrition in General Surgery Residency

The attrition for general surgery residency remained significantly higher for Black trainees (4.1% [211 of 5081]) compared with Asian trainees (2.9% [454 of 15 448]; P = .001), Latino trainees (2.7% [78 of 2934]; P < .001), or White trainees (2.6% [1477 of 56 320]; P < .001). Over time, all groups had a significant decline in attrition, from 4.4% (18 of 409) to 3.2% (11 of 346) (P = .04) for Black trainees, 3.4% (8 of 236) to 2.1% (8 of 375) (P = .03) for Latino trainees, 4.3% (58 of 1345) to 2.4% (33 of 1368) (P < .001) for Asian trainees, and 3.8% (157 of 4157) to 2.0% (98 of 4954) (P < .001) for White trainees.

Discussion

The 2020 US Census shows that the US population is more racially and ethnically diverse than expected, with the percentage of White US citizens decreasing to less than 60%, while the percentage of Asian, Black, and Hispanic citizens continuing to increase. Based on the changing demographics, a 41% and 23% growth in full-time equivalent physicians is needed for the rising Hispanic and Black US population, respectively, by 2032.9 However, over the past 120 years, there has been an underwhelming 4% increase in Black physicians in the US,10 despite numerous publications highlighting the benefits of promoting racial and ethnic diversity along with proposed strategies.11 We hypothesized that Black trainees have poor matriculation and graduation rates from surgical training. When the percentage of UIM surgeons does not reflect the percentage of UIM individuals in the population, health care suffers. It has been shown that patients choose physicians of similar race and ethnicity12 and are more likely to follow the physician’s instructions and therefore more likely to maintain good health.13 In addition, UIM students are more likely to desire practicing in underserved areas.14

It is not surprising that a similar trend is echoed in our study, with the overall portion of Black general surgery residency graduates remaining essentially unchanged from 2005 to 2018 (6.3%). Furthermore, in evaluating the intersectional identity of these trends, we demonstrate that there has been little progress in retaining Black women matriculants and graduates, despite their increasing application rates. There has been a decline in the proportion of Black men matriculating and graduating, a concerning trend given an already low representation. The etiology of this alarming trend is likely implicit and explicit bias. In 2020, Yuce and colleagues15 investigated the prevalence and extent of discrimination based on race and ethnicity in 301 general surgery residency programs across the US. The overall prevalence of racial and ethnic discrimination was 24%, but when stratified by race, Black individuals had an overwhelmingly higher prevalence of discrimination at 70%. On multivariable logistic regression analysis in determining risk factors for discrimination, a surgical resident was 20-fold more likely to experience racial discrimination if they were Black. In addition, Black surgical trainees reported less positively on program fit and relationships with faculty and peers,16 all contributing to the social isolation and invisibility of working in a predominantly White environment often reported by UIM residents.17

In analyzing racial disparities in general surgery residency workforce, it is important to identify problematic areas for which actionable plans can be implemented: (1) address the bottleneck effect from the small pools of UIM students via pipeline programs and establish adequate representation of Black surgeons in leadership and mentorship roles5 and (2) examine the culture of equity and inclusion at these institutions with appropriate changes implemented. Perceived barriers to surgery for Black medical students include lack of effective mentorship and sponsorship, having to excessively prove themselves, and concerns of being a racial and ethnic minority woman in surgery.18 The above examples may be significant deterrents for Black students with prior interest in surgical careers. Acknowledging and understanding these inherent conflicts and challenges arising from differences in race and culture is important in creating a culture of inclusion.

Overall, academic institutions should promote a culture of zero tolerance for discrimination, empower trainees to report discriminatory or hostile behaviors, provide trainees tools for anonymous reporting of microaggressions and discriminatory actions as a support mechanism, facilitate support and integration of Black trainees, implement implicit bias and antiracism awareness training, and proactively support relatable role models and mentors, including Black surgeons in leadership positions.1,15,16 Therefore, strategies to engage the interests of qualified Black applicants should include (1) starting and enhancing pipeline programs at multiple levels and in early education,18,19 (2) developing visiting clerkships for medical students who self-identify as Black,2 (3) fostering an environment of diversity and inclusion within general surgery training programs,15 (4) initiating and supporting formal mentorship initiatives,2,20 and (5) recruiting and promoting Black surgeons to traditional leadership roles through intentional sponsorship.11 These strategies will highlight an institutional commitment to fostering an environment of racial sensitivity and cultural competency that should prove welcoming to all residents.16

Examination of intersectional race and ethnicity and gender identity in our study revealed that the improvement in gender disparity is attributable to an increase in the graduation of Asian women and, more notably, White women but not Black or Latina women.21 The low numbers of Black and Latina women surgical trainees are not the result of a lack of interest in general surgery as a career.22 In fact, this study demonstrates that there is an increasing number of Black and Latina women applicants to general surgery residency.

The current study did not include traditional metrics, such as clerkship grades, United States Medical Licensing Examination STEP scores, and research productivity, to evaluate the qualifications of applicants. Further research is needed to identify and address metrics that may negatively affect the overall application, as many of these metrics are not predictive of clinical competencies required to successfully complete residency training or of performance on board examinations.23

Use of a more holistic approach for application screening and selection, with reviewers blinded to United States Medical Licensing Examination scores and other metrics not predictive of clinical skills, should be considered.2,23 Diversifying review committees and individual interviewers are also important.18 Moreover, a continued need to develop and sustain targeted initiatives to successfully recruit and retain Black women remains.3,24

A paucity of adequate role models has also been identified as a factor in general surgery attrition for women.25 The positive effect of role models of the same gender, subspecialty, and possibly race and ethnicity cannot be overstated; trainees can see themselves represented at a higher level, while mentors can help navigate the challenges linked to greater professional dissatisfaction and burnout in women surgeons. Compared with their men counterparts, women surgeons have to navigate gender-biased misperceptions, hidden and unjust work standards, unequal pay and promotion, social isolation, and work-home conflicts.7,21,25 Structured mentorship between a medical student and a surgical trainee or faculty member and between a trainee and faculty member can help manage personal and professional expectations.15,21 A significant obstacle to this is the small pool of available Black role models in academic surgery.18 A recent study revealed the profound disparity in academic rank, promotion, National Institutes of Health research funding, and leadership roles of Black women within academic surgery.4 At the time of the study, there were only 10 Black women Professors of Surgery. (Since then, W.G. and K.-A.J. have been promoted to Professors of Surgery.) The scarcity of Black women among surgery faculty and leadership negatively affects recruitment, promotion, mentorship, and retention of Black women trainees and perpetuates a cycle of underrepresentation at all levels. Intentional and progressive action at the institutional and national level with the implementation of an equivalent work credit for diversity, equity, and inclusion work to help alleviate the “minority tax”26 for Black trainees is needed to recruit and retain a diverse academic faculty.1,19

The decline in the general surgery residency matriculation and graduation rates for Black men is concerning and parallels the shrinking presence of Black men applying to and attending medical school over the past 35 years. Alarmingly, there were fewer Black men that matriculated at US medical schools in 2014 than in 1978,27 a staggering finding when one considers the vast expansion of medical schools in the US. This disparity is only a small piece of a larger societal problem and is reflective of the disadvantages often experienced by Black men in the US. Black men have historically had lower life expectancy, higher death rate, more encounters with an inequitable criminal system, and fewer educational and employment opportunities.28 Additionally, there are negative perceptions of Black men in the media and throughout society along with the scarcity of role models in medicine.27 The subsequent outcome is the lack of representation of Black men in medicine, which is now recognized as a national crisis.

In August 2020, the AAMC and the National Medical Association announced an action collaborative for Black men in medicine. The goal of this action collaborative is to focus on systemic solutions to increase the representation and success of Black men interested in medicine, with recognition that interventions are needed as early as elementary school.29 Greater collaboration across the systems and communities that will be provided by this action collaborative may prove crucial in reducing the systemic barriers encountered by Black men.

Limitations

A limitation to our study is the inability to distinguish between categorical graduates (hired for 5 years of training) and preliminary general surgery graduates (hired for 1 year of training) from the AAMC data. This distinction is problematic, as a preliminary general surgery resident can later match into a categorical position, duplicating the graduation data after completing their categorical years. In addition, some preliminary general surgery graduates may later match into other specialties. Both scenarios may result in an overestimation of the graduates that actually practice general surgery. Given the small numbers and concern for privacy, the attrition data could not be stratified by gender. Another potential limitation is the variability in the methodology used by AAMC to collect data on race and ethnicity. From academic year 2002-2003 until academic year 2012-2013, the AAMC asked about the race(s) with which an individual identified and Hispanic origin separately. From academic year 2013-2014 to the present, the AAMC has collected race and ethnicity data in a single question that allowed individuals to select any combination of races and Hispanic origin. Because of these changes, race and ethnicity data may not be directly comparable across time. Additionally, lack of accurate coding of ethnic groups is a limitation especially regarding Hispanic/Latino learners and learners of African ancestry who may be immigrants or first-generation citizens and thus not self-identify as per AAMC definitions. Additionally, although the response rate for the GME track residency survey was lower during the early years of the study, the overall response rates were generally robust and unlikely to influence the results.

Conclusions

Little progress has been made in eliminating the disparity between Black general surgery trainees and the general population in the US over the last 2 decades. Black women graduates of general surgery residency programs have remained unchanged, while the representation of Black men graduates have declined. Having a diverse physician workforce is imperative to better reflect the population being treated and to address widespread health care disparities. Efforts to increase Black and other UIM men and women in medicine help to reach a greater percentage of the underserved population and improve the quality of patient care and improve outcomes. We know that patient-physician racial and ethnic concordance matters when addressing health inequities, especially in racial and ethnic minority communities. Individual, institutional, and national initiatives are urgently warranted to address racial and ethnic as well as gender disparities in general surgery residency programs.

References

- 1.Newman EA, Waljee J, Dimick JB, Mulholland MW. Eliminating institutional barriers to career advancement for diverse faculty in academic surgery. Ann Surg. 2019;270(1):23-25. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000003273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jarman BT, Borgert AJ, Kallies KJ, et al. Underrepresented minorities in general surgery residency: analysis of interviewed applicants, residents, and core teaching faculty. J Am Coll Surg. 2020;231(1):54-58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kane K, Rosero EB, Clagett GP, Adams-Huet B, Timaran CH. Trends in workforce diversity in vascular surgery programs in the United States. J Vasc Surg. 2009;49(6):1514-1519. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2009.02.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berry C, Khabele D, Johnson-Mann C, et al. A call to action: Black/African American women surgeon scientists, where are they? Ann Surg. 2020;272(1):24-29. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000003786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Keshinro A, Frangos S, Berman RS, et al. Underrepresented minorities in surgical residencies: where are they? a call to action to increase the pipeline. Ann Surg. 2020;272(3):512-520. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000004209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aggarwal A, Rosen CB, Nehemiah A, et al. Is there color or sex behind the mask and sterile blue? examining sex and racial demographics within academic surgery. Ann Surg. 2021;273(1):21-27. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000004461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gray K, Neville A, Kaji AH, et al. Career goals, salary expectations, and salary negotiation among male and female general surgery residents. JAMA Surg. 2019;154(11):1023-1029. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2019.2879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Acosta DA, Poll-Hunter NI, Eliason J. Trends in racial and ethnic minority applicants and matriculants to U.S. medical schools, 1980-2016. Accessed August 3, 2021. https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/analysis-brief/report/trends-racial-and-ethnic-minority-applicants-and-matriculants-us-medical-schools-1980-2016

- 9.Association of American Medical Colleges . The complexities of physician supply and demand: projections from 2018 to 2033. Accessed November 2, 2021. https://www.aamc.org/system/files/2020-06/stratcomm-aamc-physician-workforce-projections-june-2020.pdf

- 10.Ly DP. Historical trends in the representativeness and incomes of Black physicians, 1900-2018. J Gen Intern Med. Published online April 19, 2021. doi: 10.1007/s11606-021-06745-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Butler PD. When excellence is still not enough. Am J Surg. 2020;220(3):543-544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saha S, Taggart SH, Komaromy M, Bindman AB. Do patients choose physicians of their own race? Health Aff (Millwood). 2000;19(4):76-83. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.19.4.76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Murray-García JL, García JA, Schembri ME, Guerra LM. The service patterns of a racially, ethnically, and linguistically diverse housestaff. Acad Med. 2001;76(12):1232-1240. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200112000-00018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Association of American Medical Colleges . Diversity in medicine: facts and figures 2019. Accessed May 31, 2021. https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/workforce/interactive-data/figure-11-percentage-us-medical-school-matriculants-planning-practice-underserved-area-race

- 15.Yuce TK, Turner PL, Glass C, et al. National evaluation of racial/ethnic discrimination in US surgical residency programs. JAMA Surg. 2020;155(6):526-528. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2020.0260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wong RL, Sullivan MC, Yeo HL, Roman SA, Bell RH Jr, Sosa JA. Race and surgical residency: results from a national survey of 4339 US general surgery residents. Ann Surg. 2013;257(4):782-787. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318269d2d0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roberts SE, Nehemiah A, Butler PD, Terhune K, Aarons CB. Mentoring residents underrepresented in medicine: strategies to ensure success. J Surg Educ. 2021;78(2):361-365. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2020.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roberts SE, Shea JA, Sellers M, Butler PD, Kelz RR. Pursing a career in academic surgery among African American medical students. Am J Surg. 2020;219(4):598-603. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2019.08.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abelson JS, Symer MM, Yeo HL, et al. Surgical time out: our counts are still short on racial diversity in academic surgery. Am J Surg. 2018;215(4):542-548. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2017.06.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dageforde LA, Kibbe M, Jackson GP. Recruiting women to vascular surgery and other surgical specialties. J Vasc Surg. 2013;57(1):262-267. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2012.07.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rangel EL, Lyu H, Haider AH, Castillo-Angeles M, Doherty GM, Smink DS. Factors associated with residency and career dissatisfaction in childbearing surgical residents. JAMA Surg. 2018;153(11):1004-1011. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2018.2571 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Peel JK, Schlachta CM, Alkhamesi NA. A systematic review of the factors affecting choice of surgery as a career. Can J Surg. 2018;61(1):58-67. doi: 10.1503/cjs.008217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gardner AK, Cavanaugh KJ, Willis RE, Dunkin BJ. Can better selection tools help us achieve our diversity goals in postgraduate medical education? comparing use of USMLE step 1 scores and situational judgment tests at 7 surgical residencies. Acad Med. 2020;95(5):751-757. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mason BS, Ross W, Ortega G, Chambers MC, Parks ML. Can a strategic pipeline initiative increase the number of women and underrepresented minorities in orthopaedic surgery? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2016;474(9):1979-1985. doi: 10.1007/s11999-016-4846-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.de Costa J, Chen-Xu J, Bentounsi Z, Vervoort D. Women in surgery: challenges and opportunities. Int J Surg Global Health. 2018;1(1):e02. doi: 10.1097/GH9.0000000000000002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rodríguez JE, Campbell KM, Pololi LH. Addressing disparities in academic medicine: what of the minority tax? BMC Med Educ. 2015;15:6. doi: 10.1186/s12909-015-0290-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Association of American Medical Colleges . Altering the Course, Black Males in Medicine. Association of American Medical Colleges; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Laurencin CT, Murray M. An American crisis: the lack of Black men in medicine. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2017;4(3):317-321. doi: 10.1007/s40615-017-0380-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Association of American Medical Colleges . AAMC, NMA announce action collaborative on Black men in medicine. Accessed April 29, 2021. https://www.aamc.org/news-insights/press-releases/aamc-nma-announce-action-collaborative-black-men-medicine