Abstract

Solar cells based on organic compounds are a proven emergent alternative to conventional electrical energy generation. Here, we provide a computational study of power conversion efficiency optimization of boron dipyrromethene (BODIPY) derivatives by means of their associated open-circuit voltage, short-circuit density, and fill factor. In doing so, we compute for the derivatives’ geometrical structures, energy levels of frontier molecular orbitals, absorption spectra, light collection efficiencies, and exciton binding energies via density functional theory (DFT) and time-dependent (TD)-DFT calculations. We fully characterize four D−π–A (BODIPY) molecular systems of high efficiency and improved Jsc that are well suited for integration into bulk heterojunction (BHJ) organic solar cells as electron-donor materials in the active layer. Our results are twofold: we found that molecular complexes with a structural isoxazoline ring exhibit a higher power conversion efficiency (PCE), a useful result for improving the BHJ current, and, on the other hand, by considering the molecular systems as electron-acceptor materials, with P3HT as the electron donor in the active layer, we found a high PCE compound favorability with a pyrrolidine ring in its structure, in contrast to the molecular systems built with an isoxazoline ring. The theoretical characterization of the electronic properties of the BODIPY derivatives provided here, computed with a combination of ab initio methods and quantum models, can be readily applied to other sets of molecular complexes to hierarchize optimal power conversion efficiency.

Introduction

The intensive exploitation of energy resources, the growth of global demand for energy, and the associated environmental crisis, e.g., the increase of fossil fuel consumption, are concerns that require immediate attention and evidence the need for alternative sources of renewable energy to avoid further impact on climate change. In this sense, the metal-free organic solar cells (OSCs) are potential candidates to aid in this task. During the past two decades, organic solar cells have attracted much attention due to their quick improvement of photovoltaic properties and environmental and economic advantages; these include low-cost fabrication, lightweight, mechanical flexibility, high versatility due to applications in many fields, and the simplicity of the synthesis process.1−3 The improvement of organic materials’ photophysical capabilities of a new hole transporting material (HTM) and electron transporting material (ETM), which constitute the photoactive components in organic photovoltaic (OPV) cell devices, can increase the performance of such solar energy conversion materials.4−8 Thus, BODIPY–fullerene derivative synthesis becomes a valuable alternative to compose hole and electron transporting materials. This is so, since, as an acceptor component, the fullerene promotes the presence of many closely spaced electronic levels and a high degree of delocalized charge within an extended π-conjugated structure, as well as a low reorganization energy, making these molecular assemblies ideal for acting as electron transporting materials in the charge-separation state.9−11

Recently, among the commonly used artificial photosynthetic chromophores, the boron dipyrromethene (BODIPY) compounds have been of particular interest due to their extraordinary spectral and electronic properties as well as their high absorption coefficients and high emission quantum yields. This leads to an extensive use of BODIPY structures as building blocks for both nanoantenna systems and charge-separation units.12−15 The BODIPY dyes open the possibility to extend the absorption cross-section over a wide spectral range of OPV devices, e.g., BODIPY-C60 dyads.16,17 Consequently, they have been used in applications involving the development of sensors, photodynamic therapy agents, light-energy-harvesting systems,18,19 and protein markers, to cite a few.20,21

In general, the absorption spectra in the near-infrared region motivate the adoption of BODIPY as materials for OSC integration.22 However, few works in the literature show the derivatives of BODIPY and BODIPY–fullerene in the active layer at the construction of photovoltaic devices, among which we find a derivative of BODIPY and PCBM that is used as an active layer in heterojunction solar cells, reaching a PCE of 1.34% in 2009.23 In 2016, Liao et al. synthesized and characterized different molecules based on BODIPY and implemented an OSC, using PC61BM as an electron-acceptor material, with a PCE of 2.15%.4 In 2017, Singh et al. reported a higher efficiency of 7.2% for an OSC built with BODIPY-DTF and PC61BM.24

Despite the low PCE values for these OSCs compared to those of the amorphous silicon/crystalline silicon heterojunction cells (PCE around 26.63%), the bulk heterojunction (BHJ) organic solar cells, including conjugated polymers and BODIPY and BODIPY–fullerene derivatives, provide an effective solution for the roll-to-roll production and the fabrication on flexible substrates.25,26 This said, higher power conversion efficiencies in BHJ solar cells require a morphology that delivers electron and hole percolation pathways to optimize the electronic transport, including a donor–acceptor contact area high enough to form a charge-transfer state near the unit. This constitutes a significant structural challenge, particularly for semiconductor polymer–fullerene systems.27 Then, it becomes a necessity to provide information on molecular systems within the BHJ organic solar cells that can improve the energy conversion potential in such structures.

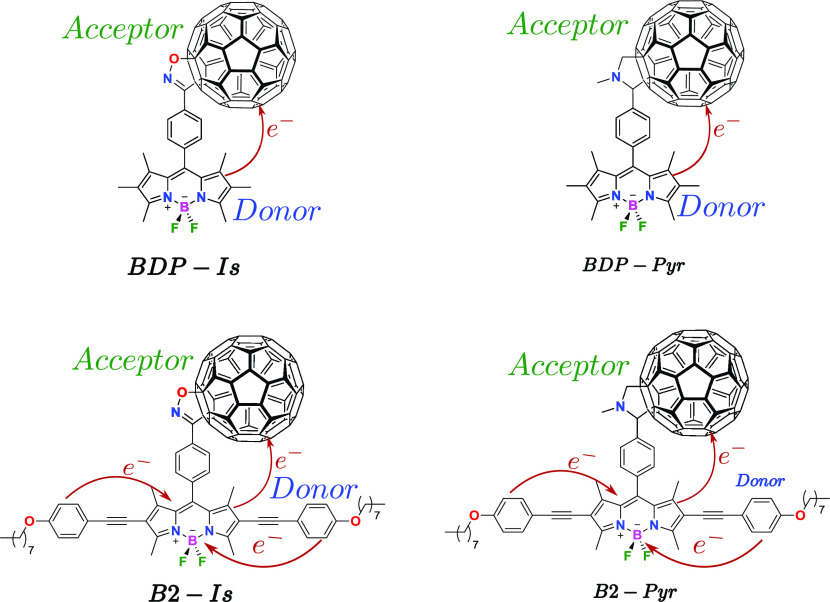

In this work, we propose novel molecular systems derived from BODIPY–fullerene (see Figure 1), which exhibit experimental evidence of intramolecular electron transfer processes as D−π–A materials.6,28,29 By means of Scharber’s model, we were able to compute the PCE and estimate the maximum conversion efficiency (under ideal conditions), thus establishing some working conditions for application to photovoltaic devices.

Figure 1.

Molecular chromophores under study. For simplicity, we have labeled the complexes as BDP-Is, BDP-Pyr, B2-Is, and B2-Pyr.

Results and Discussion

Molecular Systems and Computational Results

In the development of the criteria described here, we consider the molecular systems reported in refs (6, 28), and (29) (see Figure 1). These exhibit experimental parameters already measured, which allow for a direct comparison with our theoretical results via the calculation of observables such as electronic energy levels, absorption spectra, charge-transfer states, and others. The molecules under consideration are shown in Figure 1; we have termed them as follows: BDP-Is, BDP-Pyr, B2-Is, and B2-Pyr. The calculations involve the use of the density functional theory (DFT) with a B3LYB exchange–correlation functional30 and the base set 6–311G(d,p). These allow the investigation of the ground-state optimization geometry of the electron-acceptor and electron-donor components and the prediction of the frontier molecular orbital energies.31,32

The excitation energy, the absorption spectral electronic coupling, the oscillator strength, and the charge-transfer state of the systems shown in Figure 1 are based on the time-dependent density functional theory (TD-DFT) with a hybrid CAM-B3LYP functional. In the ground state, the geometrical configurations were completely optimized with DFT, while the excited state was optimized via TD-DFT. The molecular environment influence was modeled as a dielectric medium by employing a conductor-like polarization continuum model (C-PCM).33,34 The C-PCM is regularly used to recognize the solvation, which indicates the solvent effects in the molecular complex. Here, the polarity effects on the molecular photophysics are modeled on the basis of considering (polar) methanol and (nonpolar) toluene as dissolvents, which are characterized by the dielectric constants εM = 32.6130 and εT = 2.3741, respectively.

There are different methods to determine the electronic properties of organic molecules. Here, we specialize in the DFT Kohn–Sham energy levels, while the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) level can be related to the ionization potential according to Janak’s theorem.35 Nevertheless, we remark that the results will markedly rely on the employed functional.

Transport Properties

Charge-Transfer States

The charge-transfer (CT) states between the electron-donor and electron-acceptor parts in the molecular system have a fundamental role in organic solar-cell operation. Thus, a better understanding of CT intramolecular processes is expected to optimize the organic photovoltaic (OPV) materials, improving the device performance36,37 toward the CT state control. Although electronic excitations on individual molecules are well characterized, a thorough description of CT states is still missing. The challenge to analyze the CT states arises from the multiple factor dependences, such as the molecular geometry, the nature of the pure and mixed donor/acceptor domains, and the interaction with the surrounding polar or nonpolar environment. At the electronic structure level, all of these factors can influence the electron polarization and extend the electronic delocalization having a strong influence on the energy and nature of the CT state.38

The intramolecular electron transfer process involves the following: the system is initially photoexcited from the ground electronic state to π–π* states (|ψDj⟩) primarily localized on either place in the donor part. A nonradiative CT process then occurs at a later stage, corresponding to an electronic transition from the |ψD⟩ state to the CT state (|ψAi⟩) involving a significant CT from donor to acceptor. Once such electron dynamics is known, we employ density functional theory (DFT) to determine the electronic ground state and the time-dependent density functional theory (TD-DFT) to calculate the excited states as well as the geometry and energy by the electrostatic environment affected in CT states. From a quantum mechanical viewpoint, the understanding of this kind of process may help in improving the power conversion efficiency. Our principal concern is then to observe and understand the effects due to the solvent polarity and geometry of the molecular complexes on the electronic and transport properties, especially in excitation and CT states, which is currently an open problem.

As an overview of the molecules with the performed calculations, Table 1 shows the frontier orbital localization according to the donor and acceptor fragments for the molecular complexes BDP-Is, BDP-Pyr, B2-Is, and B2-Pyr. All of the molecular systems have a similar distribution of orbital localization, as shown in Table 1. The molecular orbitals from HOMO–2 to HOMO–5 are located in the electron-acceptor part, while the HOMO–1 and HOMO are in the electron-donor part, and the bound LUMOs are in the electron-acceptor part. Nevertheless, the LUMO+3 in the BDP-Is, BDP-Pyr, and B2-Is and LUMO+2 in the B2-Pyr system are in the confined electron-donor fragment. With the orbital localization, we observe that a low-energy transition leading to the formation of the |ψDj⟩ state located in the electron donor takes place from HOMO or HOMO–1 to LUMO+3 (or LUMO+2 in the B2-Pyr molecule); the D*−π–A represents the resulting state. On the other hand, an electronic transition in a highly probable CT takes place from one of the bound HOMOs located at the electron donor to the LUMO located at the electron acceptor, giving rise to the |ψA⟩ state represented as D+–π–A–.

Table 1. Most Probable Donor (D) or Acceptor (A) Fragments for Localization of Electronic Orbitals in the Molecular Systems BDP-Is, BDP-Pyr, B2-Is, and B2-Pyr.

|

fragment |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| orbitals | BDP-Is | BDP-Pyr | B2-Is | B2-Pyr |

| HOMO–5 | A | A | A | A |

| HOMO–4 | A | A | A | A |

| HOMO–3 | A | A | A | A |

| HOMO–2 | A | A | A | A |

| HOMO–1 | D | D | D | D |

| HOMO | D | D | D | D |

| LUMO | A | A | A | A |

| LUMO+1 | A | A | A | A |

| LUMO+2 | A | A | A | D |

| LUMO+3 | D | D | D | A |

| LUMO+4 | A | A | A | A |

| LUMO+5 | A | A | A | A |

Table S1 summarizes the first twenty-five lowest-energy electronic transitions with their energies, oscillator strength, and orbital involved in the electronic transition for the molecular systems BDP-Is, BDP-Pyr, B2-Is, and B2-Pyr in methanol (for toluene, see Table S2 in the Supporting Information). We consider an electronic state with excitation energies below 3.7 eV to match the spectral range of OPV devices. We characterize the different states by considering their detachment–attachment electron densities that are illustrated in Figure 2 (for the B2-Pyr and B2-Is, see Figure S1 in the Supporting Information), following the procedure by Head-Gordon.39

Figure 2.

Electron density associated with the excited states for the molecular complexes (a) BDP-Is and (b) BDP-Pyr in the methanol solvent.

In BDP-Is and BDP-Pyr configurations, we find four relevant excited states, which can be classified as follows:

The excited states |ψDj⟩ are localized on the donor part and present an oscillator strength with small charge-transfer values between the donor and acceptor fragments and can be identified as the donor π–π* excitation.

The excited states labeled as |ψA1⟩, |ψA⟩, ..., |ψAi⟩ are characterized by a small oscillator strength and a large charge-transfer values between the donor and acceptor part. This process is essentially due to the transference of one electron from the donor to the acceptor segment, constituting a charge-transfer state.

As for the charge-transfer state energies used in the charge-transfer process, they are calculated with a combination of excitation energies from TD-DFT calculations, implementing the ionization potential (IP) and electronic affinity (EA) of the different charge sites and a Coulomb energy term that describes the interaction of the relevant charge sites. The ground state is the reference state, and its diabatic state energy is set to zero. The energy of the locally excited diabatic state (D*–A) is calculated as the vertical excitation energy to the adiabatic state that most represents it. The energy of one of the charge-transfer states (CTS) with a positive charge at site x and a negative charge at site y is calculated as40,41

| 1 |

where IPD is the ionization potential of the donor fragment, which was calculated by subtracting the total energy of the neutral molecule from that of the cation, as calculated by DFT. EAj is the electronic affinity of the acceptor fragment and was obtained by subtracting the total energy of the anion from that of the neutral state. Eℏν is the lowest single excited state energy of the donor molecule calculated by TD-DFT, and Ec(rxy) is the Coulomb interaction between the cation on the donor fragment and the anion on the acceptor fragment. rDj is the distance from the center of mass of the donor fragment to the center of mass of the acceptor fragment, based on the optimized ground-state structure.

Therefore, we found one excitation state |ψD1⟩ = |ψD⟩ for the complexes BDP-Is and BDP-Pyr. With fosc = 0.6040 for the BDP-Is system and fosc = 0.6068 for the BDP-Pyr complex, with resulting excitation energy of 2.4811 and 2.5042 eV, respectively, mainly originated from a HOMO–to–LUMO+3 transition, corresponding to the |ψD⟩ (π–π*) state in the BODIPY molecules. In addition, there are three CT states characterized by a small oscillator strength (0.0001–0.0092), as shown in Figure 2. In the molecules B2-Is and B2-Pyr, we found one excited state |ψD⟩ with fosc = 0.7820 (system B2-Is) and fosc = 0.7800 (system B2-Pyr), and five CT states |ψA⟩ with small oscillator strengths (0.0001–0.0025) and large electron transfer (0.95e–1.2e) (see Figure 2). However, the charge-transfer states used in this work are those with a favorable driving force (ΔG < 0) since they present a greater interaction with the excited states and higher electron transfer, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Occupancy of individual excited states as a function of time for (a) BDP-Is, (b) BDP-Pyr, (c) B2-Is, and (d) B2-Pyr in methanol.

As mentioned above, in Tables 2 and S1 (Supporting Information), the system BDP-Is has two CT states, D+–A–. The first one with an excitation energy of 1.9715 eV, |ψA1⟩, is formed through the first electronic transition due to the main contribution of HOMO-to-LUMO+1. The second one, |ψA⟩, is formed via the HOMO-to-LUMO+2 electronic transition characterized by an excitation energy of 2.1632 eV and also a vanishing oscillator strength. Thus, there are two channels for the dissociation of the exciton D*–A into D+–A– via the photoinduced states |ψA1⟩ and |ψA⟩ with a favorable driving force ΔG|ψA1⟩ = −0.5096 eV and ΔG|ψA2⟩ = −0.3179 eV, respectively. The third state |ψA3⟩ is not considered here because of an unfavorable driving force ΔG = 0.0851 eV. According to Veldman et al., ΔG|ψAi⟩ is the dissipated energy in the CT state formation (|ψD⟩ → |ψA⟩); a negative value for ΔG|ψAi⟩ ensures the necessary driving force for the photoinduced electron transfer (PET) in a photovoltaic blend.42 Considering the first twenty lowest-energy values for electronic transitions, we found only two CT states with a favorable driving force in the molecular structures B2-Is and B2-Pyr. However, in all of the systems, we found |ψAi⟩ states with unfavored driving forces (ΔG > 0), as shown in Table 2; this can be attributed to the lack of interactions between frontier molecular orbitals.

Table 2. Electronic Coupling (Vji), Reorganization Energy (λe), Driving Force (ΔG), Activation Energy (Er), and Constant Rates (s–1) According to Marcus Theory fmor (j → i) Electronic Transitions for the Molecular Complexes BDP-Is, BDP-Pyr, B2-Is, and B2-Pyr in Ethanol.

| molecule | i → j | |Vji| (meV) | λe (eV) | ΔG (eV) | Er (eV) | κe (s–1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BDP-Is | |ψD⟩ → |ψA1⟩ | 7.36 | 0.1347 | –0.5096 | 0.2609 | 1.0212 × 1008 |

| |ψD⟩ → |ψA2⟩ | 25.17 | 0.1347 | –0.3179 | 0.0623 | 2.5945 × 1012 | |

| |ψD⟩ → |ψA3⟩ | 4.17 | 0.1347 | 0.0851 | 0.0897 | 2.4735 × 1010 | |

| BDP-Pyr | |ψD⟩ → |ψA1⟩ | 29.33 | 0.1356 | –0.5245 | 0.2788 | 8.0932 × 1008 |

| |ψD⟩ → |ψA2⟩ | 6.22 | 0.1356 | –0.4399 | 0.1707 | 2.3846 × 1009 | |

| |ψD⟩ → |ψA3⟩ | 19.01 | 0.1356 | –0.2448 | 0.0220 | 7.0189 × 1012 | |

| B2-Is | |ψD⟩ → |ψA1⟩ | 4.87 | 0.1332 | –0.2785 | 0.0396 | 2.3546 × 1011 |

| |ψD⟩ → |ψA2⟩ | 12.04 | 0.1332 | –0.1988 | 0.0081 | 4.8650 × 1012 | |

| |ψD⟩ → |ψA3⟩ | 1.41 | 0.1332 | 0.0436 | 0.0586 | 9.3726 × 1009 | |

| |ψD⟩ → |ψA4⟩ | 1.16 | 0.1332 | 0.1036 | 0.1052 | 1,0618 × 1009 | |

| |ψD⟩ → |ψA5⟩ | 2.87 | 0.1332 | 0.1837 | 0.1884 | 2.5744 × 1008 | |

| B2-Pyr | |ψD⟩ → |ψA1⟩ | 3.70 | 0.1358 | –0.2159 | 0.0118 | 3.9816 × 1011 |

| |ψD⟩ → |ψA2⟩ | 6.20 | 0.1358 | –0.1108 | 0.0011 | 1.6507 × 1012 | |

| |ψD⟩ → |ψA3⟩ | 1.50 | 0.1358 | 0.1366 | 0.1366 | 5.3790 × 1008 | |

| |ψD⟩ → |ψA4⟩ | 1.90 | 0.1358 | 0.1723 | 0.1748 | 1.9255 × 1008 | |

| |ψD⟩ → |ψA5⟩ | 3.00 | 0.1358 | 0.2763 | 0.3127 | 2.2841 × 1006 |

Comparing the energy amount of the |ψD(A)j(i)⟩ states between molecules with similar geometry (BDP-Is and BDP-Pyr), we found a considerable difference probably attributed to the conjugation of electrons in the ion pair of the oxygen (O) and nitrogen (N) atoms within the isoxazoline fragment with the π-conjugated BODIPY core system.

The addition of the alkoxyphenylethynyl fragments in the molecules B2-Is and B2-Pyr generate excited states with lower energy than those presented in BDP-Is and BDP-Pyr systems. The energetic ordering of solvated states in methanol is maintained for all systems, and the favorable driving forces follow the hierarchy ED > EA1 > EA > EA3 because the solvation energy increases with the strength of the dipole as expected.

On the other hand, the electronic coupling forces calculated between the excitation state |ψDj⟩ and the |ψA⟩ state, obtained via the generalized Mulliken–Hush (GMH) method, as shown in Table 2, suggest the charge transfer from the excited state |ψD⟩ to the |ψAi⟩ states of the photoinduced charge as a possible mechanism. The electronic coupling between the |ψD⟩ and |ψA⟩ states is greater for the BDP-Pyr molecule than for the other systems. The coupling between |ψD⟩ and |ψA2⟩ maintained this behavior, as can be seen in Table 2 for the electron transfer case.

Charge-Transfer Rate Constants

The kinetics of the photoinduced charge transfer is modeled following the image of Marcus’s theory.43,44 The charge transfer is a crucial process involved in many physical and biological phenomena (e.g., in a first approximation, photosynthesis).45 Marcus’ result gives

| 2 |

where Vij is the electronic coupling between the states |ψDj⟩ and |ψA⟩, λe is the reorganization energy, and kB is the Boltzmann constant.

We consider a scenario where the photoexcitation toward the excited

state (i.e., large oscillator strength states) is followed by nonradiative

transitions. These transitions are to lower-lying charge-transfer

state corresponding to charge separation instantaneously upon absorption

(e.g., states |ψA1⟩, |ψA⟩ and|ψA3⟩ in the BDP-Is configuration). Marcus’ constant rate for the |ψD⟩ to |ψAi⟩ state transition and the parameters

that influence these constant rates (the electronic coupling coefficients Vij, the reorganization energy

λe, the driving force ΔG = EA – EDj, and the activation

energies  ) are given in Table 2.

) are given in Table 2.

For the molecular complexes, the electron transfer rates |ψD⟩ → |ψA2⟩ have the same order of magnitude in all systems, with the exception of the BDP-Pyr system where it is presented in |ψD⟩ → |ψA⟩. Additionally, we found that the CT state with a value of ΔG > 0 for the photoinduced electron transfer process has an ET lower rate (between two to six magnitude orders) than the CT states with ΔG < 0 (a favorable driving force), giving us information about the relevant CT states for the charge-transfer analysis.

We noted that λe < |ΔG| for the transitions |ψD⟩ → |ψA1⟩, and |ψD⟩ → |ψA⟩ in the molecular systems BDP-Is, BDP-Pyr, and B2-Is. However, this condition is only accomplished by the |ψD⟩ → |ψA1⟩ state in the B2-Pyr system, implying that |ψA⟩ for B2-Pyr takes place in the inverted region of Marcus.46 Additionally, the |ψD⟩ → |ψA2⟩ transition in the B2-Pyr system shows a λe slightly larger than ΔE, resulting in an electronic transition with a low activation energy. Under these conditions, the classic barrier crossing may become more favorable than nuclear tunneling as a dominant transition mechanism.

Charge-Transfer Kinetics

The overall CT kinetics involves a transition between states |ψDj⟩ and |ψA⟩. Assuming that each of these transitions can be defined as a Marcus constant rate, as above, one can establish the overall kinetics in terms of a master equation describing the incoherent motion through time-dependent occupation probabilities, Pi(t), of some quantum states, |ψAi⟩. Then, the Pi(t) is a solution of rate equations of the type

| 3 |

This equation contains the rates (of probability transfer per unit time) kij for transitions from |ψD⟩ to |ψAi⟩. The first term of the right-hand side describes the decrease of Pi in time due to probability transfer from |ψD⟩ to all other states, and the second term accounts for the reverse process, including the transfer from all other states |ψA⟩ to the |ψD⟩ state. In 1928, eq 3 was “intuitively derived” by Pauli,47 then, this expression is frequently called the Pauli Master Equation or just the Master Equation. By considering ki→j = 0, we have

| 4 |

Here, PψA(D)i(t) is the excited state population |ψA(D)i⟩ at time t, such that PψD(t) + ∑iPψAi(t) = 1, with ke = kψD→ψAi as the Marcus constant rate for the electronic transition from the |ψD⟩ state to the |ψAi⟩ state (see Table 2). We do not include transitions from the excited to the ground state in the master equation and assume the initial electronic state corresponding to photoexcitation at time t = 0. Then, the occupancy is given by

| 5 |

where foscψAi is the oscillator strength of the excited state |ψAi⟩. Namely, we impose direct photoexcitation of the interfacial dimer, which guarantees that the initial state is dominated by bright states.

Figure 3 shows the occupancy of each excited state individually as a function of time in methanol for all of the molecular configurations. The initial states are the excited π–π* states (|ψD⟩), and the transitions to other states |ψAi⟩ occur selectively from |ψD⟩ at different time scales. For the BDP-Is molecular system, Figure 3a, the two CT states (|ψA⟩ and |ψA2⟩) begin with zero population and |ψA⟩ reach their steady state after ∼2.50 ps. The occupancy steady-state value of |ψA2⟩ is larger than that of the |ψA⟩ state, as there are more pathways (π-delocalization link) leading to the |ψA2⟩ state than to |ψA⟩ (see Table 2). However, for the molecular system B2-Is, we find that the steady state is reached at a slower time scale (∼0.80 ps) compared with the BDP-Is system, mostly due to the addition of fragments of the alkoxyphenylethynyl group. Figure 3c and d shows the occupancy of the individual excited state as a function of time for B2-Is and B2-Pyr molecules. For example, the π–π* state (|ψD⟩) is strongly coupled to the |ψA2⟩ state, while is weakly coupled to the |ψA⟩ state, in the molecular system B2-Is. As a result, the |ψA2⟩ state occupancy quickly rises after photoexcitation remaining, essentially, constant after that at the branching ratio value, PψD(0) kψD→ψA2/K. However, for the B2-Pyr molecular system, the |ψD⟩ state is mostly stronger coupled to the |ψA⟩ state than to the |ψA1⟩ state. The latter should not be confused with the occupancy equilibrium of the |ψA⟩ state, which will be obtained at a slower time scale only. The total occupancy of the |ψD⟩ states and the |ψAi⟩ states are plotted in Figure 4. The overall time scale on which the occupancy of the excited state depleted and that on which the occupancy of CT states increases in the BDP-Is configuration is very similar to that observed in the BDP-Pyr configuration (a similar process occurs between B2-Is and B2-Pyr). The CT occurs on the subpicosecond time scale, with 90% of the charge transferred in ∼0.80 ps for the BDP-Is system, ∼0.40 ps for the BDP-Pyr system, and ∼0.50 ps for the B2-Is system. A larger transfer time was found for the B2-Pyr system observed with 95% of the transferred charge in ∼1.8 ps.

Figure 4.

Total occupancy for the |ψD⟩ state and the charge-transfer state (|ψAi⟩) as a function of time for the different molecular complexes: (a) BDP-Is, (b) BDP-Pyr, (c) B2-Is, and (d) B2-Pyr in methanol.

Figure 3 shows that CT states with driving forces ΔG > 0 are unfavorable for the CT process and have a very small (or null) occupation when considering the dynamics of the transfer rate. However, the states with ΔG < 0 present a dynamic of considerable importance since the processes of charge transfer present between the involved states with this condition are mainly favored. Moreover, these last states have the highest transfer rate, as can be seen in Table 2.

Solvent Polarity Effects

The research of bathochromic changes in the electronic spectra of molecules provides information about molecule–solvent interactions. The observed bathochromic shift due to the increasing solvent polarity depends on the difference between the permanent dipole moments of the ground and excited state, in agreement with the dielectric polarization theory. This theory states that the bigger the moment difference between dipoles of the ground state and excited state, the greater the spectral shift induced by the solvent.48 When the dipole moment of the excited state is larger than that of the ground state, solute–solvent interactions of the excited state are stronger than those of the ground state and a red-shift of maximum absorption will be observed.

To understand the effects of the solvent polarity on the excitation and charge-transfer energy values, we studied the bathochromic change of the compounds in methanol and toluene as solvents. Initially, by considering toluene as a solvent (nonpolar), the additional generation of two charge-transfer states with a favored driving force for the B2-Is system regarding the case where methanol is considered, with energies EA1 = 1.5979 eV, EA = 1.6794 eV, EA3 = 2.9223 eV, and EA = 1.9980 eV, is observed. One additional charge-transfer state is observed for the B2-Pyr complex in toluene compared with methanol with EA1 = 1.7106 eV, EA = 1.8143 eV, and EA3 = 2.0657 eV (see the Supporting Information). However, for BDP-Is and BDP-Pyr systems, the same amount of CT state is maintained with energies EA = 1.7486 eV, EA2 = 1.8169 eV, and EA = 2.0756 eV for the BDP-Is system and EA1 = 1.8685 eV, EA = 1.9508 eV, and EA3 = 2.1516 eV for the BDP-Pyr system. Indeed, there is a decrease in the energy for the excited state π–π* (|ψD⟩) in each of the studied systems with values of 2.4811, 2.5042, 2.0868, and 2.1011 eV for the BDP-Is, BDP-Pyr, B2-Is, and B2-Pyr molecular systems, respectively. On the other hand, the dipolar moments of the excited state for the molecular systems interacting with both methanol and toluene have larger values than those for the ground state, as seen in Table 3. Hence, the interaction between the molecular complexes and the solvents is greater in the excited state than in the ground state. Complementarily, we observed the dipole moments for methanol with larger values than those for toluene in the excited state, indicating a “better” interaction between the molecules and the methanol, therefore, a better stabilization of the HOMO–LUMO orbitals in methanol. From Figures 5 and 6, it is clear that the charge-transfer process will perform better in the presence of the polar solvent methanol than in toluene. The reorganization energy estimation for the BDP-Is molecular complex yields λ = 0.1347 eV in methanol and 0.1564 eV in toluene. The difference between the two can be traced back to the larger amount and extent of charge transfer in methanol compared to toluene.

Table 3. Dipole Moments Calculated for Ground and Excited States of BDP-Is, BDP-Pyr, B2-Is, and B2-Pyr Molecular Systems in Toluene and Methanol Solvents (in Debye Units).

| toluene |

methanol |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| molecule | ground | excited | ground | excited |

| BDP-Is | 3.8368 | 4.7372 | 3.1336 | 5.3112 |

| BDP-Pyr | 5.6067 | 6.0955 | 4.5418 | 7.4045 |

| B2-Is | 3.8467 | 4.6521 | 3.7648 | 5.3845 |

| B2-Pyr | 4.2827 | 5.3459 | 4.2287 | 6.5372 |

Figure 5.

Occupancy of individual π–π* (|ψD⟩) and |ψAi⟩ states for (a) BDP-Is, (b) BDP-Pyr, (c) B2-Is, and (d) B2-Pyr configurations in methanol (M) and toluene (T). The dashed lines are the |ψD⟩T and |ψA⟩T states for toluene, and the solid line is |ψD⟩M and |ψAi⟩M for methanol.

Figure 6.

Total occupancy dynamics for the |ψD⟩ state and the charge-transfer state (|ψAi⟩) as a function of time (in methanol and toluene) for (a) BDP-Is, (b) BDP-Pyr, (c) B2-Is, and (d) B2-Pyr.

The existence of intramolecular charge-transfer mechanisms in the current molecular systems gives us information about the capabilities to use them as electron-donor materials. However, the analysis of other properties such as the optical, electronic, and photovoltaic properties employing Scharber’s model offers us a precise scenario about the potential application of these systems in the construction of organic solar cells. Scharber’s model describes an estimation for the power conversion efficiency in bulk heterojunction solar cells, knowing the energy levels (to estimate the capability of the molecule in a BHJ OSC), and provides an indication of the capabilities of the molecular system that is to be achieved by assuming an efficient charge, absorption, and charge-separation process.

Optical and Electronic Properties

In OSC photoactive materials, the active layer (electron-donor material) plays an essential role in the sunlight absorption because the electron acceptor (e.g., PCBM) should have a weak absorption in the visible and near-infrared regions. To investigate the absorption properties of these molecules, such as excitation energies, oscillator strength of the electronic excitations, the composition of vertical transitions, and the UV/VIS absorption spectrum, we carried out TD-DFT calculations with a CAM-B3LYP functional.

The excitation energy and corresponding oscillator strength associated with λmax for each molecular system are listed in Table 4. The spectroscopic parameters corresponding to the D−π–A derivatives are summarized in Table 4, and the simulated absorption curves for toluene and methanol are presented in Figure 7. The time-dependent (TD) DFT calculation for the molecular complexes shows that for the BDP-Is compound, the optically allowed electronic transition is related to populating the HOMO → LUMO+3 excitation with high oscillator strength (fosc), which is related to an energy band that registers an absorption peak at 508.196 nm for toluene and 499.775 nm for methanol in the absorption spectrum of Figure 7; possibly ascribed to the intramolecular charge transfer in the BODIPY part. The BDP-Pyr compound shows an absorption peak at 503.564 nm for toluene and 495.159 nm for methanol associated with the HOMO → LUMO+3 electronic transition in accordance with the experimentally reported value28 (505 nm for Toluene) and an oscillator strength fosc = 0.6061. The simulated absorption spectra show, for the B2-Is compound, a peak with maximum absorption at 599.410 nm, with fosc = 0.8214 for toluene and 594.200 nm for methanol in which the electronic transitions HOMO → LUMO+3 (representing a 97%) correspond to an intramolecular charge transfer. Finally, the B2-Pyr molecule absorption spectrum represents the envelope of all possible electronic transitions at different absorption wavelengths finding a higher contribution in the electronic transition at 596.508 nm in toluene associated with the HOMO → LUMO+3 transition and 590.170 nm in methanol corresponding to the HOMO → L+2 transition.

Table 4. Summary of the Maximum Theoretical λmax and Experimental λmaxExp Absorption Wavelength, Excitation Energy Eexc, Oscillator Strength fosc, Contribution of the Most Probable Transition, and the Light-Harvesting Efficiency (LHE) of the Studied Compounds.

| molecule | λmax (nm) | λmaxExp (nm) | Eexc (eV) | fosc | composition | LHE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| toluene | ||||||

| BDP-Is | 508.196 | 506 | 2.440 | 0.654 | H → L+3 (98%) | 0.778 |

| BDP-Pyr | 503.564 | 505 | 2.462 | 0.652 | H → L+3 (97%) | 0.776 |

| B2-Is | 599.410 | 591 | 2.068 | 0.821 | H → L+3 (97%) | 0.856 |

| B2-Pyr | 596.508 | 589 | 2.078 | 0.848 | H → L+3 (98%) | 0.853 |

| methanol | ||||||

| BDP-Is | 499.775 | 2.481 | 0.602 | H → L+3 (97%) | 0.751 | |

| BDP-Pyr | 495.159 | 2.505 | 0.606 | H → L+3 (98%) | 0.753 | |

| B2-Is | 594.200 | 2.087 | 0.782 | H → L+3 (97%) | 0.824 | |

| B2-Pyr | 590.170 | 2.101 | 0.780 | H → L+2 (98%) | 0.823 |

Figure 7.

Simulated absorption spectra in (a) toluene (C7H8) and (b) methanol (CH3OH) with TD-DFT/CAM-B3LYP/6–311G(d,p) for BDP-Is, BDP-Pyr, B2-Is, and B2-Pyr molecular complexes.

Another parameter that provides information on the radiation capture efficiency of the electron-donor material (BDP-Is, BDP-Pyr, B2-Is, and B2-Pyr) in addition to the absorption spectra is the light-harvesting efficiency (LHE). Generally, the LHE is closest to the magnitude of the oscillator strength fosc and can be expressed as49,50

| 6 |

According to eq 6, the bigger the fosc, the higher the LHE. The LHE corresponding to λmax in the molecules presents the following order B2-Is > B2-Pyr > BDP-Is > BDP-Pyr, as shown in Table 4. The LHE values for the D−π–A derivatives are in the range between 0.751 and 0.856, meaning that all electron-donor compounds have a similar sensitivity to sunlight.49,51

Electronic Properties

There are several molecular systems that have been used in organic solar cells (OSCs) to improve the energy conversion efficiency in those devices. We remark that the theoretical knowledge about the HOMO and LUMO molecular energies is crucial to understand the electronic dynamics in those cells. The HOMO and LUMO energies of the donor segments (D−π–A) and the LUMO levels of the acceptor part are relevant parameters to determine the efficient charge transfer between the donor and the acceptor. In OSCs, the energy of the HOMO–LUMO frontier orbitals of the photoactive components have a close relationship with the photovoltaic properties because the energy levels are related to the open-circuit voltage (Voc) and the energy driving force (ΔE) for the exciton dissociation.52 For an estimation of the HOMO–LUMO frontier orbitals energy of the molecular complexes, we adjusted the equations of Bérubé et al.,52 such that

| 7 |

We performed the calculations by employing the B3LYP/6–311G(d,p) level to estimate the geometrical structure, the frontier orbitals, the exciton driving force energy, and the corresponding band gap for eight compounds BDP-Is, BDP-Pyr, B2-Is, and B2-Pyr, listed in Table 5.

Table 5. Calculated Values of the Frontier Orbitals HOMO (H) and LUMO (L) Energies which Constitute the Photoactivated Material with the Respective Estimation (HEst and LEst), Energy Gap ΔEg, and Energy of the Exciton Driving Force ΔE (in eV) for Exciton Dissociation in Toluene and Methanol.

| molecule | HOMODFT | LUMODFT | HOMOEst | LUMOEst | ΔEg | ΔE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| toluene | ||||||

| BDP-Is | –5.51 | –3.28 | –5.667 | –3.820 | 1.846 | 0.388 |

| BDP-Pyr | –5.47 | –3.14 | –5.640 | –3.725 | 1.914 | 0.483 |

| B2-Is | –5.10 | –3.27 | –5.388 | –3.814 | 1.574 | 0.394 |

| B2-Pyr | –5.08 | –3.12 | –5.374 | –3.712 | 1.663 | 0.496 |

| PCBM | –5.91 | –3.85 | –5.939 | –4.208 | 1.731 | N.A. |

| methanol | ||||||

| BDP-Is | –5.58 | –3.20 | –5.714 | –3.766 | 1.948 | 0.442 |

| BDP-Pyr | –5.55 | –3.10 | –5.694 | –3.698 | 1.996 | 0.510 |

| B2-Is | –5.21 | –3.17 | –5.463 | –3.746 | 1.717 | 0.462 |

| B2-Pyr | –5.20 | –3.06 | –5.456 | –3.671 | 1.785 | 0.537 |

The HOMO/LUMO values of the studied compounds are shown in Table 5 and are in good agreement with previously reported experimental work.6,28 The [6,6]-phenyl-C60–butyric acid methyl ester (abbreviated as PCBM) will be used as the electron-acceptor material, which is an excellent electron transporter with a LUMO energy (−3.95 eV53) that is both high enough to support a large photovoltage, given that Voc is limited by the energy difference between the donor HOMO and the acceptor LUMO, and also low enough to provide Ohmic contacts for electron extraction and injection from common cathode electrons.54 The HOMO and LUMO values of the electron-acceptor component PCBM are experimentally reported in refs (53, 55−59); these are in good agreement with those calculated theoretically in this work and reported in Table 5 (−5.91/–3.85 eV respectively).

On the other hand, when comparing between the molecules, the calculated band gap ΔEg = ELUMO – EHOMO increases in the following hierarchy ΔEg–BDP–Pyr > ΔEg–BDP–Is > ΔEg–B2-Pyr > ΔEg–B2-Is. Other authors have previously reported the improvement of the photovoltaic properties correlated with a decreasing value of the energy gap (ΔEg).49 Consequently, the B2-Is compound is a suitable candidate for a better photovoltaic performance regarding the molecules analyzed here. The low values of ΔEg–B2-Is compared to ΔEg–BDP–Is, ΔEg–BDP–Pyr, and ΔEg–B2-Pyr indicates a significant intramolecular charge transfer in B2-Is, which translates into a red-shift of the absorption spectrum.

Comparing the band gap between the molecules BDP-Is and BDP-Pyr, as well as the B2-Is and B2-Pyr compounds, we find a larger band gap energy for BDP-Pyr and B2-Pyr than for BDP-Is and B2-Is. We can attribute this to the greater conjugation of the ion pair electrons on the oxygen and nitrogen atoms of the isoxazoline fragment with the conjugation π-system of the BODIPY core. The estimation of the exciton driving force (ΔE) is helpful in predicting the degree of efficient charge transfer between the photoactive materials within organic solar cells and is denoted60 by

| 8 |

The expression above defines the difference between the LUMO orbitals of the electron-donor (D−π–A system) and the electron-acceptor (PCBM) materials. The obtained result shows the energy differences (ΔE) higher than 0.3 eV in all of the studied composites. Therefore, an efficient exciton splitting in free charge carriers (electron–hole pairs), as well as electron transfer between the electron-donor and electron-acceptor materials, can be guaranteed. The energy losses in these molecules are minimized due to charge carrier recombination.60−62 In Table 5, a ΔE range (0.388–0.496 eV) is calculated, and from this result, an ordering between the molecular complexes appear: ΔEB2-Pyr > ΔEBDP–Pyr > ΔEB2-Is > ΔEBDP–Is. The latter can be associated with the molecular π-delocalization link in which the electrons are free to move in more than two nuclei, implying that the π-delocalization length affects ΔE in the D−π–A derivatives.49 In this sense, a longer π-delocalization length produces a lower ΔE as in the case of BDP-Is and B2-Is molecules (0.388 and 0.394 eV, respectively) in contrast to BDP-Pyr and B2-Pyr (0.483 and 0.496 eV, respectively). The delocalization is attributable to the oxygen atom inclusion in the donor−π–acceptor (D−π–A) systems, limiting the conjugation and facilitating the electronic π–delocalization. Furthermore, we observed that molecules with an oxygen atom in the structure have a better dissociation capability at the electron-donor/electron-acceptor interface due to a lower value of ΔE. The previous results show that the BDP-Is and B2-Is molecules have a lower ΔE, guaranteeing the effective exciton dissociation, which together with the low Eg presents these materials as potential candidates for bulk heterojunction solar cells.

Bulk Heterojunction Solar Cells

In bulk heterojunction (BHJ) solar cells, the active layer, which consists of two kinds of molecular materials (the electron-donor and electron-acceptor materials), is sandwiched between two electrodes with different work functions, as shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Design of a BHJ OSC requires the following as diagrammatically sketched in the steps indicated for the energy-level diagram in (a): (1) incident photons, (2) exciton formation, (3) exciton diffusion, (4) exciton dissociation, (5) charge transport, and (6) collection. (b) Configuration of the electron-donor material and the sketched PCBM structure.

To understand the operational principle of a solar cell, we divide it into six different subprocesses, as explained through the energy band gap diagram of the donor and acceptor materials in Figure 8. The steps are as follows: (1) the active layer absorbs photons producing electronic transitions between the HOMO and LUMO states of the donor material, (2) the electronic transition generates a system of electron–hole pairs known as excitons, (3) the excitons are diffused toward the acceptor material interface producing excitonic dissociation forming a charge-transfer (CT) complex, which will be favorable to occur when the energy difference between the donor LUMO and the acceptor LUMO (ΔE) is greater than the binding energy of the exciton,60 and (4) if the distance between the electron and hole becomes greater than the Coulomb trapping radius, the charge-transfer state becomes a separated (CS) state (or free charge carriers) in the photovoltaic process. However, if the electrons are unable to escape from the Coulomb trapping radius, the geminate pair will recombine across the donor/acceptor interface, constituting another losing mechanism in these devices,63 (5) the dissociated charges are transported through p-type or n-type domains toward the metallic electrodes. Finally, (6) the collected holes at the anode and electrons at the cathode can be employed in external circuits.64 While the exciton dissociation process is actually far more complex than depicted, these simplified schematics are useful for generating a conceptual understanding of the photophysical processes occurring in the OPVs.

Photovoltaic Properties

Aiming to provide a working guide that can be useful for experimental researchers in the field, we used Scharber’s model to estimate the photovoltaic properties of the analyzed materials. Initially, the bulk heterojunction organic solar cells (BHJ OSCs) present a mixture of an electron-donor π-conjugate with an electron-acceptor derivative from fullerene. Therefore, we examine the photovoltaic behavior of the new D−π–A derivatives mixed with PCBM (see Figure 1) as a widely used electron acceptor in solar-cell devices.65−69 We evaluated the power conversion efficiency (PCE) as the most commonly used parameter to compare the performance of many solar cells, as well as some important parameters such as the short-circuit current density (Jsc), the open-circuit voltage (Voc), and the fill factor (FF). The photoelectric conversion efficiency of solar-cell devices under sunlight irradiation (e.g., AM1.5G) can be determined by Jsc and Voc and the power of incident light Pin as follows70

| 9 |

where the fill factor (FF) is proportional to the maximum power of the solar cell. This approach allows us to estimate the PCE value of a given polymer or molecular systems in the active layer from its frontier orbital energy levels. The frontier energy levels and their separation (Eg) are critical for photovoltaic behavior since they directly affect the Jsc and Voc values, and a proper control of those levels is of prime importance in the design of high-performance photovoltaic devices.71

The maximum open-circuit voltage (Voc) of the BHJ solar cell according to Scharber’s model is related to the difference between the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) in the electron-donor and the LUMO of the electron-acceptor materials regarding the energy lost during the photo-charge generation.72 The theoretical value of the open-circuit voltage Voc of a conjugated polymer-PCBM solar cell can be estimated by72

| 10 |

where e is the elementary charge and 0.3 eV is an empirical factor. In operational solar cells, additional recombination paths decrease the value of Voc, affecting the PCE of OPVs because they must operate at a voltage lower than the Voc. A decreasing Voc implies a power reduction (Jsc × Voc) given by the fill factor (FF). A simple relation between the energy level of the HOMO of the molecular systems (BDP-Is, BDP-Pyr, B2-Is, and B2-Pyr) and the Voc is derived to estimate the maximum efficiency of the BHJ OSCs. Based on these considerations, the ideal parameters for a π-conjugated-system-PCBM device are determined in Table 6. The calculated Voc is in the range between 0.886 and 1.159 V in toluene and from 0.948 to 1.206 V in methanol, and these are relatively high values implying that the OPV composed of the studied molecule as an electron-donor material and PCBM has potential applications as BHJ OSCs because of their improved Voc. The Voc hierarchy is as follows: VocBDP–Is > Voc > VocB2-Is > Voc in both of the solvents, showing values higher than 1.0 V for the BDP-Is and BDP-Pyr molecules, which means an efficient increase of the Voc.

Table 6. Parameter Values of the Studied Molecular Compounds: Energy Gap (Eg), Open-Circuit Voltage (Voc), Short-Circuit Current Density (Jsc), the Fill Factor (FF), and Power Conversion Efficiency (PCE).

| molecule | ΔEg (eV) | Voc (V) | Jsc (mA/cm2) | FF | PCE (%) | PCE (%)a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| toluene | ||||||

| BDP-Is | 1.846 | 1.159 | 11.939 | 0.895 | 12.380 | 9.523 |

| BDP-Pyr | 1.928 | 1.132 | 10.575 | 0.893 | 10.685 | 8.219 |

| B2-Is | 1.574 | 0.880 | 17.155 | 0.870 | 13.136 | 10.105 |

| B2-Pyr | 1.663 | 0.866 | 15.353 | 0.869 | 11.555 | 8.888 |

| methanol | ||||||

| BDP-Is | 1.948 | 1.206 | 10.248 | 0.898 | 11.103 | 8.541 |

| BDP-Pyr | 1.996 | 1.186 | 9.541 | 0.897 | 10.146 | 7.805 |

| B2-Is | 1.717 | 0.955 | 14.295 | 0.878 | 11.984 | 9.218 |

| B2-Pyr | 1.785 | 0.948 | 13.024 | 0.877 | 10.832 | 8.332 |

The PCE value was calculated by considering an EQE of 50%.

Given that the PCEs are estimated from the values for the open-circuit voltage Voc, the short-circuit current Jsc, and the fill factor FF of the OSCs,73 to achieve high efficiencies, an ideal donor material should have a low-energy gap and a deep HOMO energy level (thus increasing Voc). Additionally, a high hole mobility is also crucial for the carrier transport to improve Jsc and FF, which can be empirically described by74,75

| 11 |

with  and νm = νoc – ln(νoc +

1 – ln(νoc)). The parameter values corresponding

to the BDP-Is, BDP-Pyr, B2-Is, and B2-Pyr compounds are shown

in Table 6. The fill

factor oscillates between 0.869 to 0.895 in toluene and from 0.877

to 0.898 in methanol, in agreement with the reported BHJ SC values

for different polymers as electron-donor and PCBM as electron-acceptor

materials.76,77

and νm = νoc – ln(νoc +

1 – ln(νoc)). The parameter values corresponding

to the BDP-Is, BDP-Pyr, B2-Is, and B2-Pyr compounds are shown

in Table 6. The fill

factor oscillates between 0.869 to 0.895 in toluene and from 0.877

to 0.898 in methanol, in agreement with the reported BHJ SC values

for different polymers as electron-donor and PCBM as electron-acceptor

materials.76,77

If the energy conversion efficiency is calculated with eq 9, by taking the Voc and FF from Scharber’s model and considering experimental Jsc values, a correlation between the calculated PCE and the experimental PCE value showing an absolute standard deviation of 0.8% is found.78 However, if the theoretical value for Jsc and experimental FF is used to calculate the PCE, a considerable change is observed in the correlation between PCETer and PCEExp, which indicates a high sensibility of Jsc to the structural or morphology change in the OPV devices. Thus, similar to the FF and Voc, the short-circuit current density (Jsc) is another important parameter involved in the calculation of PCE and can be determined as follows65

| 12 |

where EQE(λ) is the external quantum efficiency, ϕAM1.5G is the flow of photons associated with the solar spectral irradiance in AM1.5G, q is the electronic charge, and λ1 and λ2 are the limits of the active spectrum of the device. The photon absorption rate of the donor and acceptor materials, the exciton dissociation efficiency, and the resultant charge transportation efficiencies toward the electrodes limit the Jsc values. This quantity represents the probability for a photon to be converted into an electron.

The highest reported EQEs are around 50–65%.58,79 The calculated values reported in Table 6 for PCE and Jsc have considered an EQE of 65%. These values show that the BDP-Is and B2-Is compounds have higher PCE, probably associated with the insertions of an oxygen atom in their molecular structure. Additionally, we can observe that the B2-Is molecule is a great candidate as a compound in the manufacture of organic solar cells.

We can further observe that although the BDP-Is and BDP-Pyr systems possess a comparable Voc of 1.159 and 1.132 V in toluene, respectively, and a quite similar form factor, the Jsc is completely different, marking a great difference in their corresponding PCE values.

Since the model uses rather simple assumptions for the EQE value in eq 12, there is an associated imprecision in the Jsc estimations. The EQE is a complex frequency-dependent function that considers the transport effects and the morphology of the films. The Jsc values from Scharber’s model do not define a strict upper bound and should be considered only as an indicator for the molecular capability as a light-harvesting device. In this way, the estimation of the EQE value is a sensitive parameter in Scharber’s model to define the accuracy between the calculated and the actual experimental PCE values.

Molecular Systems as Electron-Acceptor Materials

The C60 fullerene has often been chosen as an excellent electron acceptor since it presents a triple-degenerated low-energy LUMO. This molecular structure is also capable of reversibly accepting up to six electrons and offers unusually low reorganization energy in charge-transfer processes, allowing ultra-fast charge-separation processes and slow charge recombination.80,81 Therefore, we expect that the merger between C60 and the BODIPY unit may exhibit acceptor properties being able to act as electron-acceptor materials in molecular photovoltaic devices. Therefore, here we consider the analyzed systems as electron-acceptor materials due to the presence of the C60 fullerene in their molecular structure. Hence, we consider the poly(3-hexylthiophene-2,5-diyl) (P3HT) as the electron-donor material because of the relative stability, ease of scalability by direct synthesis,82 and compatibility with high-performance production techniques. Additionally, the widespread use and the well-known material capabilities in OPV research during some time make the P3HT a typical candidate to perform some theoretical tests.83,84 The P3HT became the pioneering material to research on conjugated polymers due to advances in synthetic methodologies, establishing applications in several organic electronic devices such as solar cells, field-effect transistors, light-emitting diodes, and many others. This material has commonly been employed in several fundamental studies regarding charge transport and film morphology because of the smoothness of the synthesis and the high-grade optoelectronic properties.85,86P3HT is soluble in a variety of solvents, allowing advantages over other electron-donor materials as the reduced band gap and the high mobility of holes (>0.1 cm2/Vs) with a suitable morphology control and an absorption edge in 650 nm, which matches with the maximum solar photon flux between 600 nm and 700 nm.87 In this work, the molecular orbital HOMO/LUMO (5.10/2.65 eV) values were calculated following the section Molecular Systems and Computational Results and are in good agreement with the reported values in the literature.88−90

Table 7 shows the calculated photovoltaic property values considering Scharber’s method72 in which the active layer is a P3HT: D−π–A system. We observed that all calculated Voc show large values (1.268–1.376 V), implying that the D−π–A systems improved the P3HT Voc, thus opening the possibility for photovoltaic applications. In addition, we observed a range of around 0.320–0.428 eV in the difference of the LUMO energy levels between P3HT and D−π–A systems, suggesting a photoexcited electron transfer from P3HT to D−π–A, fair enough to be employed in photovoltaic devices. In this order of ideas, we observed lower ΔE values for BDP-Pyr and B2-Pyr systems involving most probable dissociation processes in the donor/acceptor interface than in BDP-Is and B2-Is molecules.

Table 7. Photovoltaic Properties of the Molecular Compounds: Energy of the Exciton Driving Force ΔE, Open-Circuit Voltage Voc, Short-Circuit Current Density Jsc, the Fill Factor FF, and Power Conversion Efficiency PCE.

| molecule | ΔE | Voc (V) | Jsc (mA/cm2) | FF | PCE (%) | PCE (%)a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BDP-Is | 0.428 | 1.268 | 9.541 | 0.902 | 10.527 | 8.098 |

| BDP-Pyr | 0.320 | 1.376 | 9.541 | 0.908 | 11.543 | 8.879 |

| B2-Is | 0.422 | 1.274 | 9.541 | 0.902 | 10.590 | 8.146 |

| B2-Pyr | 0.354 | 1.342 | 9.541 | 0.906 | 11.225 | 8.635 |

The PCE value was calculated by considering an EQE of 50%.

Therefore, a lower ΔE not only ensures the dissociation of the effective exciton but also reduces the energy loss by recombination processes. Thus, molecular systems (electron-acceptor molecules) with high Voc and low ΔE should improve solar-cell performance. The low-band gap of the alkoxyphenylethynyl group allows increasing the PCE by the light absorption up to the infrared range (to harvest additional solar energy), and also changes the HOMO and LUMO levels of the analyzed molecules.91 Based on Scharber’s model,72 the maximum PCE of the photovoltaic solar cells with P3HT: D−π–A as an active layer is around 11.54% for the BDP-Pyr system and 11.23% for the B2-Pyr molecule as electron-acceptor materials.

The results obtained for the PCE with the method presented here do not represent the value reached under real experimental conditions, but rather the maximum value reached theoretically. However, some works52,92,93 show that the decrease in the PCE factor that can be achieved when comparing the results both theoretical and experimental, is around 30–50%. This shows that our systems are robust and could be of interest in the construction of OSCs or optoelectronic devices according to the PCE results shown by the NREL cell efficiency chart.94

Conclusions

The energy estimation of the frontier molecular orbitals HOMO–LUMO showed a high correlation with the available experimental data. The energy of the exciton driving force (ΔE) of all of the D−π–A derivatives has a value greater than 0.3 eV, which guarantees an efficient exciton dissociation. The results presented here demonstrate the crucial role played by the donor LUMO level in bulk heterojunction solar cells: besides a reduction of the band gap, new donor materials should be designed to optimize their LUMO value because this parameter drives the solar-cell efficiency. As seen in Table 6, we remark that an optimized open-circuit voltage translates into optimized device conversion efficiencies. Comparing the BDP-Is and BDP-Pyr systems, as well as the B2-Is and B2-Pyr compounds, we found a favorable dissociation of the exciton in the donor/acceptor interface by the electron conjugation of the ion pair in the oxygen and nitrogen atoms (of the isoxazoline fragment) with the π-conjugated BODIPY core system; consequently, a favorable PCE in the DBP–Is:PBCM and B2-Is:PBCM devices. Our results for the proposed molecular compounds show that the system with the lowest ΔE and highest Voc values exhibit excellent photoactivation features and, therefore, are very well-suited candidates for BHJ solar-cell implementation.

Finally, when molecular systems are considered as electron-acceptor materials due to the presence of fullerene in their structure, it is found that BDP-Pyr and B2-Pyr have a favorable exciton dissociation and transport of holes than the other systems; hence, they would be the most promising ones for application as electron-acceptor materials in organic solar cells, which is also reflected in their PCE values. In addition, we found that the inclusion of a pyrrolidine ring favors the PCE by comparing the BDP-Is and B2-Is systems. However, the addition of the alkoxyphenylethynyl group does not represent a favorable change for either system. We finally remark that the studied molecular systems exhibit properties that are favorable for application as photovoltaics if these are used in conjunction with PCBM and P3HT, according to the needs, as electron-donor or electron-acceptor materials.

In summary, this work makes a theoretical contribution to the physical chemistry of photovoltaic materials by establishing criteria for power conversion efficiency optimization in D−π–A molecular complexes and BHJ organic solar cells. The performed calculations range from the single-molecule domain to the PV properties of BHJ OSCs with novel electron-donor systems, which are a rapidly evolving photovoltaic technology with a projected significant role in the PV market. This said, substantial research and development efforts are still needed to achieve the performance level required to become a commercially competitive alternative.

Acknowledgments

D.M.-Ú. thanks A.-G. Mora-León for discussions about structure and chemical processes. This work was supported by the Colombian Science, Technology and Innovation Fund-General Royalties System—“Fondo CTeI-Sistema General de Regalías” under contract No. BPIN 2013000100007, and Vicerrectoría de Investigaciones at Universidad del Valle (Grants CI 9517-2 and CI 71212).

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.1c04598.

Four molecular compounds with electronic, optical, and photovoltaic properties, and a detailed description of fifteen features (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Cheng P.; Li G.; Zhan X.; Yang Y. Next-Generation Organic Photovoltaics Based on Non-Fullerene Acceptors. Nat. Photonics 2018, 12, 131–142. 10.1038/s41566-018-0104-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sun C.; Pan F.; Bin H.; Zhang J.; Xue L.; Qiu B.; Wei Z.; Zhang Z.-G.; Li Y. A Low Cost and High Performance Polymer Donor Material for Polymer Solar Cells. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 743 10.1038/s41467-018-03207-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X.; Zhang W.; Usman K.; Fang J. Small Molecule Interlayers in Organic Solar Cells. Adv. Energy Mater. 2018, 8, 1702730 10.1002/aenm.201702730. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liao J.; Zhao H.; Xu Y.; Cai Z.; Peng Z.; Zhang W.; Zhou W.; Li B.; Zong Q.; Yang X. Novel D–A–D type dyes based on BODIPY platform for solution processed organic solar cells. Dyes Pigm. 2016, 128, 131–140. 10.1016/j.dyepig.2016.01.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cai Y.; Huo L.; Sun Y. Recent Advances in Wide-Bandgap Photovoltaic Polymers. Adv. Mater. 2017, 29, 1605437 10.1002/adma.201605437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera-Espinoza A.; Insuasty B.; Ortiz A. Novel BODIPY-C60 Derivatives with Tuned Photophysical and Electron-Acceptor Properties: ISoxazolino-[60]Fullerene and Pyrrolidino-[60]Fullerene. J. Lumin. 2018, 194, 729–738. 10.1016/j.jlumin.2017.09.043. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Madrid-Úsuga D.; Melo-Luna C. A.; Insuasty A.; Ortiz A.; Reina J. H. Optical and Electronic Properties of Molecular Systems Derived from Rhodanine. J. Phys. Chem. A 2018, 122, 8469–8476. 10.1021/acs.jpca.8b08265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madrid-Úsuga D.; Susa C. E.; Reina J. H. Room temperature quantum coherence vs. electron transfer in a rhodanine derivative chromophore. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2019, 21, 12640–12648. 10.1039/C9CP01398A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganesamoorthy R.; Sathiyan G.; Sakthivel P. Fullerene based acceptors for efficient bulk heterojunction organic solar cell applications. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2017, 161, 102–148. 10.1016/j.solmat.2016.11.024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sathiyan G.; Sivakumar E.; Ganesamoorthy R.; Thangamuthu R.; Sakthivel P. Review of carbazole based conjugated molecules for highly efficient organic solar cell application. Tetrahedron Lett. 2016, 57, 243–252. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2015.12.057. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ware W.; Wright T.; Mao Y.; Han S.; Guffie J.; Danilov E. O.; Rech J.; You W.; Luo Z.; Gautam B. Aggregation Controlled Charge Generation in Fullerene Based Bulk Heterojunction Polymer Solar Cells: Effect of Additive. Polymers 2021, 13, 115. 10.3390/polym13010115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Khouly M. E.; Fukuzumi S.; D’Souza F. Photosynthetic Antenna–Reaction Center Mimicry by Using Boron Dipyrromethene Sensitizers. Chem. Phys. Chem. 2014, 15, 30–47. 10.1002/cphc.201300715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo S.; Ma L.; Zhao J.; Küçüköz B.; Karatay A.; Hayvali M.; Yaglioglu H. G.; Elmali A. BODIPY Triads Triplet Photosensitizers Enhanced with Intramolecular Resonance Energy Transfer (RET): Broadband Visible Light Absorption and Application in Photooxidation. Chem. Sci. 2014, 5, 489–500. 10.1039/C3SC52323C. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bañuelos J. BODIPY Dye, the Most Versatile Fluorophore Ever?. Chem. Rec. 2016, 16, 335–348. 10.1002/tcr.201500238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandi V.; Gobeze H. B.; D’Souza F. Ultrafast Photoinduced Electron Transfer and Charge Stabilization in Donor–Acceptor Dyads Capable of Harvesting Near-Infrared Light. Chem. – Eur. J. 2015, 21, 11483–11494. 10.1002/chem.201500728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J.-Y.; Hou X.-N.; Tian Y.; Jiang L.; Deng S.; Röder B.; Ermilov E. A. Photoinduced Energy and Charge Transfer in a Bis (triphenylamine)–BODIPY–C60 Artificial Photosynthetic System. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 57293–57305. 10.1039/C6RA06841C. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gao D.; Aly S. M.; Karsenti P.-L.; Brisard G.; Harvey P. D. Ultrafast Energy and Electron Transfers in Structurally Well Addressable BODIPY-Porphyrin-Fullerene Polyads. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2017, 19, 2926–2939. 10.1039/C6CP08000F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amin A. N.; El-Khouly M. E.; Subbaiyan N. K.; Zandler M. E.; Fukuzumi S.; D’Souza F. A novel BF 2-chelated azadipyrromethene–fullerene dyad: synthesis, electrochemistry and photodynamics. Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 206–208. 10.1039/C1CC16071K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi W.-J.; El-Khouly M. E.; Ohkubo K.; Fukuzumi S.; Ng D. K. Photosynthetic Antenna-Reaction Center Mimicry with a Covalently Linked Monostyryl Boron-Dipyrromethene–Aza-Boron-Dipyrromethene–C60 Triad. Chem. – Eur. J. 2013, 19, 11332–11341. 10.1002/chem.201300318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yee M.-c.; Fas S. C.; Stohlmeyer M. M.; Wandless T. J.; Cimprich K. A. A cell-Permeable, Activity-Based Probe for Protein and Lipid Kinases. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 29053–29059. 10.1074/jbc.M504730200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan K.; Jaquinod L.; Paolesse R.; Nardis S.; Di Natale C.; Di Carlo A.; Prodi L.; Montalti M.; Zaccheroni N.; Smith K. M. Synthesis and Characterization of β-Fused Porphyrin-BODIPY Dyads. Tetrahedron 2004, 60, 1099–1106. 10.1016/j.tet.2003.11.072. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gautam P.; Misra R.; Thomas M. B.; D’Souza F. Ultrafast Charge-Separation in Triphenylamine-BODIPY-Derived Triads Carrying Centrally Positioned, Highly Electron-Deficient, Dicyanoquinodimethane or Tetracyanobutadiene Electron-Acceptors. Chem. – Eur. J. 2017, 23, 9192–9200. 10.1002/chem.201701604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rousseau T.; Cravino A.; Bura T.; Ulrich G.; Ziessel R.; Roncali J. BODIPY Derivatives as Donor Materials for bulk heterojunction solar cells. Chem. Commun. 2009, 11, 1673–1675. 10.1039/b822770e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasa Rao R.; Bagui A.; Rao G. H.; Gupta V.; Singh S. P. Achieving the Highest Efficiency Using a BODIPY Core Decorated with Dithiafulvalene Wings for Small Molecule Based Solution-Processed Organic Solar Cells. Chem. Commun. 2017, 53, 6953–6956. 10.1039/C7CC03363J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heeger A. J. 25th Anniversary Article, Bulk Heterojunction Solar Cells: Understanding the Mechanism of Operation. Adv. Mater. 2014, 26, 10–28. 10.1002/adma.201304373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y.; Kramer E. J.; Heeger A. J.; Bazan G. C. Bulk Heterojunction Solar Cells: Morphology and Performance Relationships. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 7006–7043. 10.1021/cr400353v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yazmaciyan A.; Stolterfoht M.; Burn P. L.; Lin Q.; Meredith P.; Armin A. Recombination Losses Above and Below the Transport Percolation Threshold in Bulk Heterojunction Organic Solar Cells. Adv. Energy Mater. 2018, 8, 1703339 10.1002/aenm.201703339. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera-Espinoza A.; Insuasty B.; Ortiz A. Synthesis, The Electronic Properties and Efficient Photoinduced Electron Transfer of New Pyrrolidine [60]Fullerene-and Isoxazoline [60]Fullerene-BODIPY Dyads: Nitrile Oxide Cycloaddition Under Mild Conditions Using PIFA. New J. Chem. 2017, 41, 9061–9069. 10.1039/C7NJ02057K. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Calderon-Cerquera K.; Parra A.; Madrid-Usuga D.; Cabrera-Espinoza A.; Melo-Luna C. A.; Reina J. H.; Insuasty B.; Ortiz A. Synthesis, characterization and photophysics of novel BODIPY linked to dumbbell systems based on Fullerene [60] pyrrolidine and Fullerene [60] isoxazoline. Dyes Pigm. 2021, 184, 108752 10.1016/j.dyepig.2020.108752. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Becke A. D. Density-Functional Thermochemistry III. The Role of Exact Exchange. J. Chem. Phys. 1993, 98, 5648–5652. 10.1063/1.464913. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ganji M. D.; Hosseini-Khah S.; Amini-Tabar Z. Theoretical Insight Into Hydrogen Adsorption Onto Graphene: a First-Principles B3LYP-D3 Study. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2015, 17, 2504–2511. 10.1039/C4CP04399E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganji M. D.; Tajbakhsh M.; Kariminasab M.; Alinezhad H. Tuning the LUMO Level of Organic Photovoltaic Solar Cells by Conjugately Fusing Graphene Flake: A DFT-B3LYP Study. Phys. E 2016, 81, 108–115. 10.1016/j.physe.2016.03.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Takano Y.; Houk K. Benchmarking the Conductor-Like Polarizable Continuum Model (CPCM) for Aqueous Solvation Free Energies of Neutral and Ionic Organic Molecules. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2005, 1, 70–77. 10.1021/ct049977a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu K. Y.; Govindan V.; Lin L.-C.; Huang S.-H.; Hu J.-C.; Lee K.-M.; Tsai H.-H. G.; Chang S.-H.; Wu C.-G. DPP Containing D−π–A Organic Dyes Toward Highly Efficient Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells. Dyes Pigm. 2016, 125, 27–35. 10.1016/j.dyepig.2015.09.033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Janak J. Proof that ∂E/∂ni = ϵ in density-functional theory. Phys. Rev. B 1978, 18, 7165. 10.1103/PhysRevB.18.7165. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vandewal K. Interfacial Charge Transfer States in Condensed Phase Systems. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 2016, 67, 113–133. 10.1146/annurev-physchem-040215-112144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su W.-C.; Lee C.-C.; Li Y.-Z.; Liu S.-W. Influence of Singlet and Charge-Transfer Excitons on the Open-Circuit Voltage of Rubrene/Fullerene Organic Photovoltaic Device. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 28757–28762. 10.1021/acsami.6b08363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng Z.; Tummala N. R.; Fu Y.-T.; Coropceanu V.; Brédas J.-L. Charge-Transfer States in Organic Solar Cells: Understanding the Impact of Polarization, Delocalization, and Disorder. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 18095–18102. 10.1021/acsami.7b02193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Head-Gordon M.; Grana A. M.; Maurice D.; White C. A. Analysis of Electronic Transitions as the Difference of Electron Attachment and Detachment Densities. J. Phys. Chem. A 1995, 99, 14261–14270. 10.1021/j100039a012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blomberg M. R.; Siegbahn P. E.; Babcock G. T. Modeling electron transfer in biochemistry: A quantum chemical study of charge separation in rhodobacter s phaeroides and photosystem ii. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998, 120, 8812–8824. 10.1021/ja9805268. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Powell D. D.; Wasielewski M. R.; Ratner M. A. Redfield Treatment of Multipathway Electron Transfer in Artificial Photosynthetic Systems. J. Phys. Chem. B 2017, 121, 7190–7203. 10.1021/acs.jpcb.7b02748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veldman D.; Meskers S. C.; Janssen R. A. The energy of charge-transfer states in electron donor–acceptor blends: insight into the energy losses in organic solar cells. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2009, 19, 1939–1948. 10.1002/adfm.200900090. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marcus R. A. Electron Transfer Reactions in Chemistry. Theory and Experiment. Rev. Mod. Phys. 1993, 65, 599–610. 10.1103/RevModPhys.65.599. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marcus R. A. Chemical and Electrochemical Electron-Transfer Theory. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 1964, 15, 155–196. 10.1146/annurev.pc.15.100164.001103. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gray H. B.; Winkler J. R. Electron Flow Through Proteins. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2009, 483, 1–9. 10.1016/j.cplett.2009.10.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin S.; Li L.; Yang Y.; Reimers J. R. Challenges for the accurate simulation of anisotropic charge mobilities through organic molecular crystals: The β phase of mer-tris (8-hydroxyquinolinato) aluminum (III)(Alq3) crystal. J. Phys. Chem. C 2012, 116, 14826–14836. 10.1021/jp303724r. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pauli W. Über das H-Theorem vom Anwachsen der Entropie vom Standpunkt der neuen Quantenmechanik. Probleme der Modernen Physik: Arnold Sommerfeld zum 1928, 60, 549–564. [Google Scholar]

- Lee C.; Yang W.; Parr R. G. Development of the Colle-Salvetti correlation-energy formula into a functional of the electron density. Phys. Rev. B 1988, 37, 785. 10.1103/PhysRevB.37.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tai C.-K.; Hsieh C.-A.; Hsiao K.-L.; Wang B.-C.; Wei Y. Novel Dipolar 5,5,10,10-Tetraphenyl-5,10-ihydroindeno[2,1-a]-indene Derivatives for SM-OPV:A Combined Theoretical and Experimental Study. Org. Electron. 2015, 16, 54–70. 10.1016/j.orgel.2014.10.031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Manzoor T.; Asmi S.; Niaz S.; Hussain Pandith A. Computational Studies on Optoelectronic and Charge Transfer Properties of Some Perylene-Based Donor-π-Acceptor systems for Dye Sensitized Solar Cell Applications. Int. J. Quantum Chem. 2017, 117, e25332. 10.1002/qua.25332. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fitri A.; Benjelloun A. T.; Benzakour M.; Mcharfi M.; Hamidi M.; Bouachrine M. Theoretical Design of Thiazolothiazole-Based Organic Dyes with Different Electron Donors for Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells. Spectrochim. Acta, Part A 2014, 132, 232–238. 10.1016/j.saa.2014.04.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bérubé N.; Gosselin V.; Gaudreau J.; Cote M. Designing Polymers for Photovoltaic Applications Using Ab Initio Calculations. J. Phys. Chem. C 2013, 117, 7964–7972. 10.1021/jp309800f. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma G.; Shanap T.; Patel K.; El-Mansy M. Photovoltaic Properties of Bulk Heterojunction Devices Based on CuI-PVA as Electron Donor and PCBM and Modified PCBM as Electron Acceptor. Mater. Sci.-Pol. 2012, 30, 10–16. 10.2478/s13536-012-0003-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brabec C. J.; Heeney M.; McCulloch I.; Nelson J. Influence of Blend Microstructure on Bulk Heterojunction Organic Photovoltaic Performance. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011, 40, 1185–1199. 10.1039/C0CS00045K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Z.; Fan B.; Xue F.; Adachi C.; Ouyang J. Organic Molecules Based on Dithienyl-2,1,3-benzothiadiazole as New Donor Materials for Solution-Processed Organic Photovoltaic Cells. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2010, 94, 2230–2237. 10.1016/j.solmat.2010.07.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y.-J.; Lo W.-C.; Liu S.-W.; Cheng C.-H.; Chen C.-T.; Wang J.-K. Unified Assay of Adverse Effects From the Varied Nanoparticle Hybrid in Polymer–Fullerene Organic Photovoltaics. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2013, 116, 153–170. 10.1016/j.solmat.2013.03.031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X.; Li X.-D.; Ma L.-X.; Zhang B. Electronic and Electrochemical Properties as Well as Flowerlike Supramolecular Assemblies of Fulleropyrrolidines Bearing Ester Substituents with Different Alkyl Chain Lengths. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 60342–60348. 10.1039/C4RA10654G. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jagadamma L. K.; Al-Senani M.; El-Labban A.; Gereige I.; Ndjawa N.; Guy O.; Faria J. C.; Kim T.; Zhao K.; Cruciani F.; et al. Polymer Solar Cells with Efficiency> 10% Enabled via a Facile Solution-Processed Al-Doped ZnO Electron Transporting Layer. Adv. Energy Mater. 2015, 5, 1500204 10.1002/aenm.201500204. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo S. H.; Kum J. M.; Cho S. O. Tuning the electronic band structure of PCBM by electron irradiation. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2011, 6, 545 10.1186/1556-276X-6-545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D.; Zhang X.; Ding W.; Zhao X.; Geng Z. Density Functional Theory Design and Characterization of D–A–A Type Electron Donors with Narrow Band Gap for Small-Molecule Organic Solar Cells. Comput. Theor. Chem. 2014, 1029, 68–78. 10.1016/j.comptc.2013.12.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Walker B.; Liu J.; Kim C.; Welch G. C.; Park J. K.; Lin J.; Zalar P.; Proctor C. M.; Seo J. H.; Bazan G. C.; et al. Optimization of Energy Levels by Molecular Design: Evaluation of Bis-Diketopyrrolopyrrole Molecular Donor Materials for Bulk Heterojunction Solar Cells. Energy Environ. Sci. 2013, 6, 952–962. 10.1039/c3ee24351f. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Duan Y.-A.; Geng Y.; Li H.-B.; Jin J.-L.; Wu Y.; Su Z.-M. Theoretical Characterization and Design of Small Molecule Donor Material Containing naphthodithiophene central unit for efficient organic solar cells. J. Comput. Chem. 2013, 34, 1611–1619. 10.1002/jcc.23298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzio K. A.; Luscombe C. K. The future of organic photovoltaics. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44, 78–90. 10.1039/C4CS00227J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao F.; Inganas O. Charge Generation in Polymer-Fullerene Bulk-Heterojunction Solar Cells. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2014, 16, 20291–20304. 10.1039/C4CP01814A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennler G.; Scharber M. C.; Brabec C. J. Polymer-Fullerene Bulk-Heterojunction Solar Cells. Adv. Mater. 2009, 21, 1323–1338. 10.1002/adma.200801283. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng Z.; Bredas J.-L.; Coropceanu V. Description of the Charge Transfer States at the Pentacene/C60 Interface: Combining Range-Separated Hybrid Functionals with the Polarizable Continuum Model. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2016, 7, 2616–2621. 10.1021/acs.jpclett.6b00911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangaud E.; Meier C.; Desouter-Lecomte M. Analysis of the Non-Markovianity for Electron Transfer Reactions in an Oligothiophene-Fullerene Heterojunction. Chem. Phys. 2017, 494, 90–102. 10.1016/j.chemphys.2017.07.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee D.; Forsuelo M. A.; Kocherzhenko A. A.; Whaley K. B. Higher-Energy Charge Transfer States Facilitate Charge Separation in Donor–Acceptor Molecular Dyads. J. Phys. Chem. C 2017, 121, 13043–13051. 10.1021/acs.jpcc.7b03197. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang T.; Chen X.-K.; Ashokan A.; Zheng Z.; Ravva M. K.; Brédas J.-L. Bulk Heterojunction Solar Cells: Impact of Minor Structural Modifications to the Polymer Backbone on the Polymer–Fullerene Mixing and Packing and on the Fullerene–Fullerene Connecting Network. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2018, 28, 1705868 10.1002/adfm.201705868. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lu L.; Zheng T.; Wu Q.; Schneider A. M.; Zhao D.; Yu L. Recent Advances in Bulk Heterojunction Polymer Solar Cells. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 12666–12731. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]