Abstract

Objective

Impaired cognitive function is a central symptom of schizophrenia and is often correlated with inferior global functional outcomes. However, the role of some neurobiological factors such as cortical structure alterations in the underlying cognitive damages in schizophrenia remains unclear. The present study attempted to explore the neurobiomarkers of cognitive function in drug-naive, first-episode schizophrenia by using structural magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

Methods

The present study was conducted in patients with drug-naive, first-episode schizophrenia (SZ) and healthy controls (HCs). MRI T1 images were pre-processed using CAT12. Surface-based morphometry (SBM) was utilised to evaluate structural parameters such as cortical thickness and sulcus depth. The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) and Chinese version of the Measurement and Treatment Research to Improve Cognition in Schizophrenia (MATRICS) consensus cognitive battery (MCCB) were employed to estimate the psychotic symptoms and cognition, respectively.

Results

A total of 117 patients with drug-naive first-episode schizophrenia (SZ) and 98 healthy controls (HCs) were included. Both the cortical thickness and sulcus depth in the frontal lobe were lower in patients with SZ than in the HCs under family-wise error correction (p < 0.05). Attention and visual learning in MCCB were positively correlated with the right lateral orbitofrontal cortical thickness in the patients with SZ (p < 0.01).

Conclusions

The reduced surface value of multiple cortical structures, particularly the cortical thickness and sulcus depth in the frontal lobe, could be the potential biomarkers for cognitive impairment in SZ.

Keywords: Schizophrenia, Drug-naive, First-episode, Cognition, Cortical surface

Introduction

Schizophrenia, a persistent and disabling psychiatric disorder, affects 0.5–1% of the global population and is commonly characterised by a range of positive, negative, and cognitive symptoms [1, 2]. Although positive symptoms in the form of hallucinations and delusions are the most distinctive features of the disorder, cognitive impairment usually precedes the onset of psychosis and is a reliable predictor of the overall long-term social functional outcome [3]. Cognitive domains such as working memory, executive function, and attention are generally damaged in schizophrenia [4, 5]. Several studies have exhibited that cognitive impairments such as decline in executive function occur in the initial stages or at the onset of schizophrenia [6]. Cognitive impairment is observed throughout the course of schizophrenia, and the degree of cognitive recovery is strongly associated with the individual prognosis [7].

The Measurement and Treatment Research to Improve Cognition in Schizophrenia (MATRICS) Consensus Cognitive Battery (MCCB) is a typical and representative cognitive testing tool that has been extensively employed in China to assess the cognitive function in patients with neuropsychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia and bipolar disorder [8]. The reliability and validity of MCCB have been verified through the development and revision by researchers, system testing, and clinical trials [9]. Numerous studies have demonstrated that patients with both first-episode and chronic schizophrenia exhibit cognitive deficits in multiple cognitive functions evaluated using MCCB [10, 11].

Several animal and cadaver brain studies support the neurodevelopmental hypothesis of schizophrenia, which indicate that the brain development in schizophrenia is abnormal [12, 13]. MRI studies have demonstrated the aberrant structure and function of the brain in schizophrenia, including structural abnormalities such as altered grey matter volume [14], thickness, and gyrification [15]. Some variations in the grey matter volume or thickness of the brain are significantly associated with cognitive damage in patients with schizophrenia, and the abnormal frontal and temporal lobes are commonly considered the critical areas [16]. The results of studies that have explored the neurodevelopmental mechanisms of schizophrenia have been inconsistent. Heterogeneity among these studies may be attributed to the factors such as variations in medications, multiple-episode courses, duration of illness, and study samples.

Thus, the present study was conducted in patients with drug-naive first-episode schizophrenia (SZ) and healthy controls (HCs). MCCB was used to assess cognition, and surface-based morphometry (SBM) was used to investigate the structure of cortical matter in patients with SZ and HCs. The grey matter microstructure can be quantitatively assessed through voxel-based morphometry (VBM) and SBM. SBM is more sensitive and better at detecting the brain structure variation than VBM. The present study performed a hypothesis-free analysis and attempted to explore the altered brain grey matter based on cortical thickness and sulcus depth in patients with SZ and HCs. Furthermore, the study attempted to identify the specific brain grey matter aberrations that are responsible for causing cognitive deficits in patients with SZ.

Materials and methods

Subjects

The present study was conducted in drug-naive first-episode schizophrenia (SZ) and healthy controls (HCs). SZ in all the patients was diagnosed by two experienced psychiatrists according to the criteria specified in the diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM)-IV. Inpatients or outpatients in Nanjing Brain Hospital, Jiangsu, China, were included in the study. All the patients meeting the eligibility criteria were voluntarily recruited continuously from 2016 to 2020. Right-handed patients between 16 and 45 years of age, with an intelligence quotient (IQ) of > 70 and a duration of untreated SZ ≤ 24 months, who were never treated with antipsychotic medications or physical therapy were included in the study. Pregnant women, patients with a history of mental illness, and those contraindicated for magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scanning were excluded from the study. The clinical trial was approved by the Institutional Review Committee of the Affiliated Brain Hospital of Nanjing Medical University. All experimental procedures were performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and other relevant regulations. Written informed consent was obtained from all the participants before conducting the study.

All HCs in the present study were enrolled consecutively from the community through poster advertisements. The absence of psychosis in the HCs was confirmed by a professional psychiatrist who used the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I disorders: Patient edition. Additionally, the HCs were examined for the absence of any significant medical or neurological illness, pregnancy, suicidal tendency, history of alcohol or drug abuse, or MRI scanning contraindications.

Clinical measurement

Clinical demographic information was provided by the patients and their caregivers. The right-handedness of all patients was determined using the Oldfield Handedness Questionnaire. The IQ and psychopathology outcomes of the participants were estimated using the Wechsler adult scale of intelligence and the positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) comprising three subscales, namely positive symptoms (PANSS-P), negative symptoms (PANSS-N), and general psychiatric symptoms (PANSS-G) [17]. Repeated assessment for the PANSS total score maintained an inter-rater correlation coefficient of > 0.8. The Chinese version of the MCCB includes a measure of cognitive function, and the final scores were adjusted for age, sex, and years of education. MCCB comprises the following seven psychological dimensions and 10 sub-tests [18]: (1) processing speed: trail making test, digit symbol coding subtest, and semantic verbal fluency test; (2) attention/vigilance: continuous performance test-identical pairs; (3) working memory: digital sequencing test and space span test; (4) verbal learning and memory: Hopkins verbal learning test-revised; (5) visual learning and memory: brief visuospatial memory test-revised; (6) reasoning and problem solving: mazes test; (7) social cognition: emotion management test.

MRI data pre-processing

All MRI data were obtained from the Nanjing Brain Hospital, Jiangsu, China, and an MRI system at 3.0 T (Siemens, Skyra, Germany) was applied. The following MRI parameters of the 3D T1 gradient echo were recalled in (fast field echo) sequence: repetition time (TR) = 2500 ms, echo time (TE) = 2.96 ms, flip angle (FA) = 9°, field of view (FOV) = 256 × 256 mm, slice per slab = 192, voxel size = 1.0 × 1.0 × 1.0 mm, slice thickness = 1.0 mm.

Data analysis

The independent sample t-test, analysis of variance (ANOVA), and the Chi-squared test were used to compare the demographic and clinical data. SPSS version 25.0 was used for data analyses.

The Computational Anatomy Toolbox for SPM (CAT12) was used to process cortical thickness and sulcus depth [19]. The specific process is as follows: 1. pre-processing: cortical surface estimation, topological correction, and spherical mapping or registration; 2. index extraction: cortical thickness and sulcus depth were resampled or smooth surfaces by using 15- and 20-mm full width at half maximum (FWHM) Gaussian kernel, respectively; 3. statistical analysis: analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was used to compare differences between patients with SZs and HCs by utilising age, education level, and sex as covariates, and family-wised error (FWE) correction was used for multiple comparisons (p < 0.05) [20, 21]. Additionally, the Pearson correlation test was performed for assessing the association among values of different brain regions and clinical data.

Results

Demographic and clinical measures

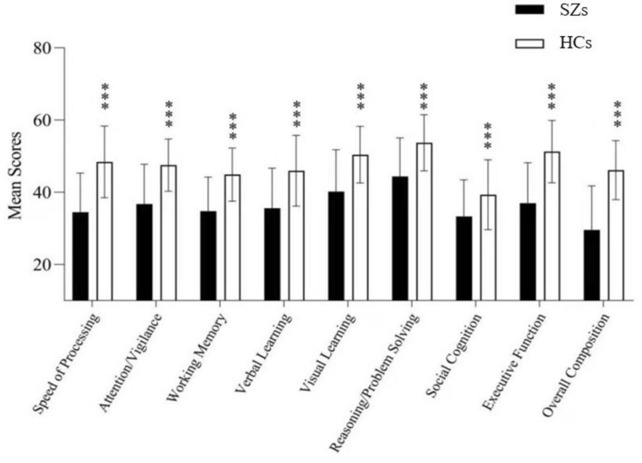

One hundred and seventeen patients with drug-naive first-episode SZ and 98 HCs were included. Table 1 presents the demographic and clinical data of all the patients. The SZ patient group exhibited a lower education level and a lower percentage of women than the HC group (t' = − 2.31, p = 0.22; χ2 = 0.32, p = 0.030, respectively). No significant difference was observed in the age between these two groups (p > 0.05). Both the total score and subscore in MCCB were lower in the SZ patient group than in the HC group (all p < 0.001) (Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and neonatal characteristics and results of the neuropsychological assessment of the SZs and HCs

| SZs (n = 117) | HCs (n = 98) | Statistic | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | t/t'/X 2 | p | |

| Age (years) | 24.73 ± 7.01 | 26.53 ± 7.05 | t' = − 0.47 | 0.062 |

| Gender (male/female) | 86/31 | 58/40 | X 2 = 0.32 | 0.030 |

| Handedness (right/left) | 115/0 | 98/0 | ||

| Years of education | 13.18 ± 2.79 | 14.14 ± 2.31 | t' = − 2.31 | 0.022 |

| DUP (months) | 15.77 ± 14.56 | NA | ||

| WAIS (IQ) | 102.80 ± 11.69 | 116.67 ± 9.15 | t'= − 8.17 | 0.000 |

| Cognitive domains | ||||

| Speed of processing | 33.52 ± 10.25 | 49.36 ± 9.74 | t' =− 9.86 | 0.000 |

| Attention/vigilance | 36.12 ± 10.82 | 47.96 ± 7.36 | t' = − 7.88 | 0.000 |

| Working memory | 34.12 ± 9.67 | 45.12 ± 7.12 | t' = − 7.97 | 0.000 |

| Verbal learning | 35.16 ± 11.08 | 46.70 ± 9.77 | t' = − 6.86 | 0.000 |

| Visual learning | 39.43 ± 11.86 | 50.73 ± 8.04 | t'= − 6.87 | 0.000 |

| Reasoning/problem solving | 43.57 ± 10.69 | 54.45 ± 7.06 | t' = − 7.39 | 0.000 |

| Social cognition | 32.69 ± 9.87 | 39.56 ± 9.16 | t' = − 4.49 | 0.000 |

| Executive function | 36.30 ± 11.01 | 52.33 ± 8.50 | t' = − 10.07 | 0.000 |

| overall composite | 28.55 ± 12.23 | 47.00 ± 7.53 | t' = − 11.46 | 0.000 |

| PANSS | ||||

| All totals | 91.48 ± 7.88 | NA | ||

| Positive symptoms | 16.16 ± 2.80 | NA | ||

| Negative symptoms | 18.95 ± 3.20 | NA | ||

| General | 46.13 ± 3.83 | NA | ||

Fig. 1.

The difference in each cognitive domain of MCCB between the patients with SZ and HCs (p < 0.001). Seven cognitive domain scores in the patients with SZ and HCs. The patients with SZ exhibited significantly lower scores in all seven cognitive domains than HCs. ***p < 0.001 compared with healthy controls at the same cognitive domain

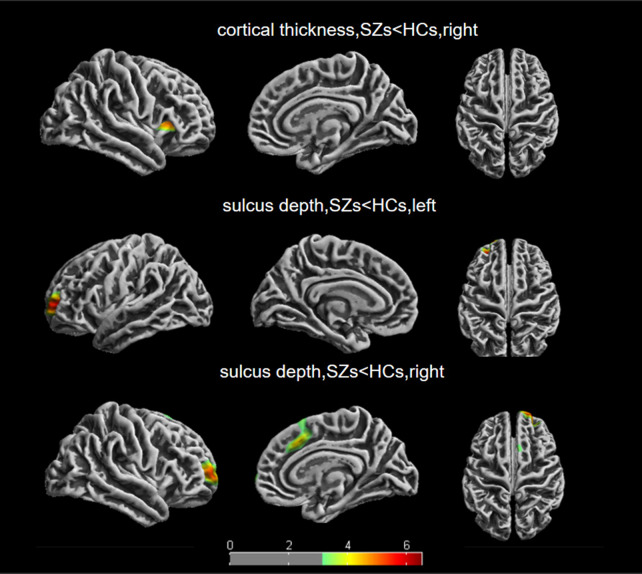

Cortical thickness comparisons between the groups

Table 2 presents the cortical thickness difference between the patients with SZ and HCs evaluated using ANCOVA, with age, sex, and education years as covariates. Patients with SZ exhibited reduced thickness in the right insula and right pars triangularis, right pars opercularis, right lateral orbitofrontal, and right precentral cortices (all p < 0.05, FWE correction). Figure 2 is an excerpt from the original map of CAT12, illustrating the specific differential brain regions.

Table 2.

Significant clusters showing group differences in cortical thickness (FWE correction, p < 0.05)

| Cortical region (hemisphere) | Cluster size, vertices | p value | Coordinates of the max | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x | y | z | |||

| 33% insula (R) | 1763 | 0.000 | 34 | 24 | 9 |

| 29% pars triangularis (R) | |||||

| 28% parsoperculairs (R) | |||||

| 9% later orbitofrontal (R) | |||||

| 1% precentral (R) | |||||

This chart is Desikan–Killiany DK40 Atlas (L: left, R: right)

Fig. 2.

Differences in cortical thickness and sulcus depth between the patients with SZ and HCs. Results of between-group two-sample t tests; FWE correct, p < 0.05. The colour bars represent t values

Sulcus depth comparisons between the groups

In Table 3, the patients with SZ exhibited lower sulcus depth in six regions, namely left rostral middle frontal, left rostral middle frontal, left superior frontal, right rostral middle frontal, right superior frontal, and right frontal pole, than HCs (all p < 0.05, FWE correction). Figure 2 is an excerpt from the original map of CAT12, illustrating the specific differential brain regions.

Table 3.

Significant clusters showing group differences in sulcus depth (FWE correction, p < 0.05)

| Cortical region (hemisphere) | Cluster size, vertices | p value | Coordinates of the Max | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x | y | z | |||

| 92% rostral middle frontal (L) | 1569 | 0.000 | − 24 | 52 | 5 |

| 8% superior frontal (L) | − 23 | 51 | 5 | ||

| 56% rostral middle frontal (R) | 1470 | 0.000 | 25 | 61 | 7 |

| 58% superior frontal (R) | 31 | 49 | 7 | ||

| 2% frontal pole (R) | |||||

| 100% superior frontal (R) | 1363 | 0.001 | 7 | 23 | 40 |

This chart is Desikan–Killiany DK40 Atlas (L: left, R: right)

Correlation analysis

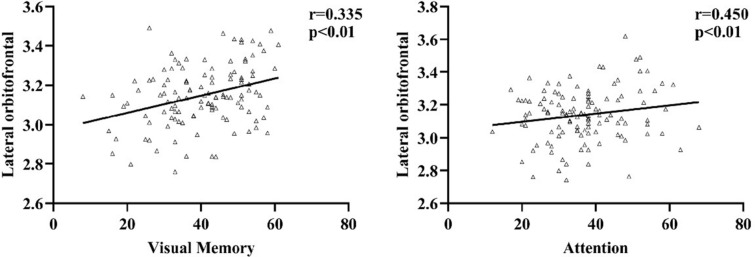

The abnormal brain region values in the patient group were extracted. Partial correlation analysis was used to determine the correlation among clinical data after correcting for age, sex, and education. The right lateral orbitofrontal cortical thickness was positively correlated with the attention and visual learning in patients with SZ (r = 0.450, p < 0.01, r = 0.335, p < 0.01, respectively) (Fig. 3). Additionally, no significant correlation was observed between sulcus depth and cognitive outcomes in the present study. No significant correlation was observed between cortical thickness or sulcus depth and the PANSS subscale score in the patients with SZ (p > 0.05). Additionally, correlation analyses revealed no obvious associations between the mean values of cortical surface and cognitive domain scores in the HCs.

Fig. 3.

Pearson correlation analyses exhibited that the cortical thickness decreased in the lateral orbitofrontal gyrus of patients with SZ and demonstrated correlation with attention and visual learning

Discussion

The cognitive function, cortical thickness, and sulcus depth in different brain regions were compared between the patients with SZ and HCs. Additionally, the correlation of the altered cortical thickness and sulcus depth with cognitive deficits in patients with SZ was analysed. Compared with HCs, the patients with SZ exhibited extensive cognitive impairments, including those related to attention, visual learning, and working memory. Moreover, the patients with SZ exhibited lesser cortical thickness in five brain regions (namely the right insula, right pars triangularis, right pars opercularis, right lateral orbitofrontal, and right precentral) and lower sulcus depth in six brain regions (namely the left rostral middle frontal and left rostral middle frontal, left superior frontal, right rostral middle frontal, right superior frontal, and right frontal pole) than HCs. The cortical thickness in the right lateral orbitofrontal was positively correlated with cognition, particularly attention and visual learning, in the patients with SZ.

Numerous studies have reported several cognitive impairments in patients with schizophrenia [22], especially in chronic patients with a long disease course [23, 24]. However, the mechanism of cognitive damages in schizophrenia remains unknown [25]. Studies have exhibited that although the long-term antipsychotic use can help in improving mental symptoms and disease control, it may cause cognitive impairment in patients [26]. Therefore, antipsychotics may be a crucial factor for cognitive impairment. However, some studies have indicated significant improvements in individuals in the prodromal stage of schizophrenia without medication [7, 27]. Although the results of these studies are inconsistent, MCCB has often been considered as the current mainstream tool for identifying cognitive function damages in the early stage of schizophrenia [11, 28]. Additionally, the GEOPTE scale, in which the subjective experience of patients is used for evaluating cognitive functions, especially social functioning, exhibits superior psychometric behaviour in terms of both internal consistency and correlation with clinical global variables, mood, and degree of insight [29]. Additionally, the cognitive function, particularly the social function, has vital clinical significance, including in predicting disease development and evaluating patient recovery, for young patients with psychiatric disorders and other high-risk groups. Targeted specialised interventions can also improve the social function of early psychosis and improve the quality of life of patients [30, 31]. The medications and long disease course can be reduced, and the pathological mechanism can be uncovered by studying the characteristics and possible mechanisms of cognitive impairment in first-episode untreated patients, which can further promote drug research and development.

Compared with HCs, the patients with SZ exhibited increased reduction in the cortical thickness in several brain regions, including the right insula, right pars triangularis, right pars opercularis, right lateral orbitofrontal, and right precentral. A study exhibited that the thickness of the left insula and superior temporal gyrus in patients with SZ was significantly thinner than that in HCs [32]; however, the study did not assess the cognitive function. Additionally, other studies have exhibited a significant decrease in cortical thickness, mainly in the frontal and temporal lobes, in patients with schizophrenia compared with that in HCs [33]. Several studies have suggested that the structural changes in the frontal and the insula lobe may be linked to schizophrenia pathogenesis. These findings are concurrent with those of the present study. Animal studies have also exhibited that the use of antipsychotics can modulate the frontal lobe function, thereby improving psychotic symptoms [34]. This finding further suggests that antipsychotics may improve the clinical symptoms of patients with schizophrenia by regulating the structure or function of the frontal cortex. In the present study, variations in cortical thickness in the right lateral orbitofrontal were associated with cognitive impairment, including attention and visual learning, in patients with SZ. Another study exhibited that the loss of grey matter in bilateral superior temporal gyrus and left frontal lobe in patients with schizophrenia may be related to attention, which may reflect as disease-related grey matter damage in patients with SZ, thus disrupting the functional–structural relationship [35]. Some studies have exhibited a diagnostic interaction between verbal IQ and the thickness of right temporo-occipital junction and the left middle occipital gyrus in patients with schizophrenia [36]. Patients with schizophrenia also exhibit an association between working memory and right medial and superior temporal cortex thickness, suggesting that these patients may use a larger compensatory network of brain regions outside the frontal cortex for working memory [37]. Findings of some of the aforementioned studies are inconsistent with our results, which may be due to differences in the sample size, drug administration, or disease course. However, a consensus exists on the changes in the cerebral cortical structure in schizophrenia, and these changes may be associated with cognitive impairment.

Patients with SZ exhibited changes in sulcus depth, mainly in the left rostral middle frontal, left rostral middle frontal, left superior frontal, right rostral middle frontal, right superior frontal, and right frontal pole. Several studies focusing on the olfactory sulcus have reported that variations in the olfactory sulcus depth that existed before the onset of psychosis can predict the transition of psychosis. Additionally, these studies have indicated that the morphology of the olfactory sulcus changes during the disease course [38, 39]. These studies may not be comprehensive enough to study the neurodevelopmental mechanism of schizophrenia owing to the limitation of the studied brain regions and the sample inconsistency. A study indicated that the gestational disruption underlying schizophrenia is likely to predate, and the burden of cognitive damages may be associated specifically with the aberrant superior frontal development, which is apparent in late second trimester [40], suggesting that brain sulcus depth changes in the olfactory and superior frontal may be involved in the development of schizophrenia. Additionally, the frontal lobe plays a critical role in the integration and regulation of higher neural activities in humans [41]. Furthermore, a study exhibited that abnormal spontaneous activities in the right middle frontal gyrus indicate the severity and cognitive damages of disease [42]. The present study observed that the sulcus depth changes in patients with SZ were concentrated in the frontal lobe compared with those in HCs. Only a few studies have investigated the cerebral sulcus and cognitive impairment in schizophrenia, and the association between abnormal sulcus depth and cognitive impairment has not been reported. The present study exhibited that both cortical thickness and sulcus depth abnormalities in schizophrenia are concentrated in the prefrontal lobe. This finding is concurrent with those of other studies and indicates a possible correlation between cortical thickness and cortical complexity. Moreover, the present study excluded the effects of drugs and long disease duration, which might have increased the reliability of the study findings.

Additionally, previous studies have found that patients with schizophrenia demonstrate varying degrees of metabolic abnormalities, including those related to thyroid hormones, steroids, and glucose metabolism. Some studies have reported that patients with first-episode psychosis have reduced thyroid-stimulating hormone levels, although thyroid-stimulating hormone level was shown to be increased in patients with multiple-episode schizophrenia [43]. Some studies suggest that the sex hormone level in schizophrenia reflects the disease severity. Moreover, the serum progesterone level was reported to be negatively correlated with the PANSS total score and PNASS positive score [44]. Mildly elevated prolactin levels were associated with higher total PANSS scores in first-episode untreated women with schizophrenia [45]. Some scholars have speculated that the oxidation–antioxidant imbalance may be one of the influencing factors leading to mild cognitive impairment in schizophrenia [46]. The present study indicates that patients with schizophrenia exhibit changes in the endocrine and metabolic levels, which may affect the cognitive level of these patients. This suggests that we need to pay attention to the relationship between metabolic changes and brain structure and cognition in schizophrenia.

Limitations

The present study has certain limitations. First, the effects of drugs and course of disease were not studied; hence, our cognitive evaluation was not detailed enough. Second, the cross-sectional design of the study prevented the prediction of neurobiological factors that may affect the SZ outcome. Moreover, some studies have exhibited that the cortical thickness decreases with age in healthy individuals, and therefore, attenuated group differences should have been considered in this research. Simultaneously, the inclusion of high-risk groups of schizophrenia and longitudinal analysis of their data would have been helpful in identifying the sensitive factors for schizophrenia. Finally, we chose the commonly used parameters in the MRI data processing, which may exhibit a few effects on the image.

Conclusions

Local reductions in the cortical thickness and sulcus depth, particularly in the superior frontal, lateral orbitofrontal, and post central regions, were observed in patients with SZ. This finding provides evidence for structural abnormalities in SZ. Additionally, the association of cortical thickness with cognitive ability and mental health outcomes was observed. Therefore, this study suggests that the cortical structure may provide biomarkers for SZ.

Acknowledgements

We sincerely thank the generous contributions of the research participants. We are also grateful to the parents for their support.

Abbreviations

- MRI

Magnetic resonance imaging

- SZs

Drug-naive first-episode schizophrenia

- HCs

Healthy controls

- SBM

Surface-based morphometry

- MCCB

Chinese version of the MATRICS Consensus Cognitive Battery

- PANSS

The Positive and Negative Syndrome

- FEW

Family-wise error

- VBM

Voxel-based morphometry

- DUP

Duration of untreated psychosis

- WAIS

Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale

- IQ

Intelligence quotient

- MCCB

The MATRICS Consensus Cognitive Battery

- PANSS

Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale

- NA

Not applicable

- FWHM

Full width at half maximum

- ANOVA

The analysis of variance

- MECT

Modified electroconvulsive therapy

Authors’ contributions

SX and XY designed the study. QW, WY, and RZ collected the data. QW and WY analysed the data and wrote the manuscript. SX and XY revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was partially supported by the Key Programme Nanjing Municipal Health Commission (ZKX21033), and the General Programme of Jiangsu Commission of Health (H2017051), and the Ministry of Science and Technology of China, National Key R&D Programme of China (2016YFC1306805). These institutions had no role in the designing the study, collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, and writing of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The data sets used and/or analysed during the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All research procedures were approved by the Medical Research Ethics Committee of Nanjing Brain Hospital and were conducted in accordance with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments. Written informed consent of the patients with schizophrenia was obtained from his/her legally authorised representative, and the healthy individuals provided written informed consent himself/herself after totally understanding the purpose of our study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential competing interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Qianqian Wei and Wei Yan contributed equally to the article and were listed as co-first authors

Contributor Information

Qianqian Wei, Email: 1170452628@qq.com.

Wei Yan, Email: yanwei@njmu.edu.cn.

Rongrong Zhang, Email: zhangrong8799@126.com.

Xuna Yang, Email: yxn730202@126.com.

Shiping Xie, Email: xieshiping@njmu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Lewis DA, Lieberman JA. Catching up on schizophrenia: natural history and neurobiology. Neuron. 2000;28:325–334. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00111-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee TY, Kwon JS. Psychosis research in Asia: advantage from low prevalence of cannabis use. NPJ Schizophr. 2016;2:1. doi: 10.1038/s41537-016-0002-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kahn RS, Keefe RS. Schizophrenia is a cognitive illness: time for a change in focus. JAMA Psychiat. 2013;70:1107–1112. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carter CS, Barch DM, Buchanan RW, Bullmore E, Krystal JH, Cohen J, Geyer M, Green M, Nuechterlein KH, Robbins T, Silverstein S, Smith EE, Strauss M, Wykes T, Heinssen R. Identifying cognitive mechanisms targeted for treatment development in schizophrenia: an overview of the first meeting of the cognitive neuroscience treatment research to improve cognition in schizophrenia initiative. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;64:4–10. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sumner PJ, Bell IH, Rossell SL. A systematic review of task-based functional neuroimaging studies investigating language, semantic and executive processes in thought disorder. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2018;94:59–75. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2018.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aquila R, Citrome L. Cognitive impairment in schizophrenia: the great unmet need. CNS Spectr. 2015 doi: 10.1017/s109285291500070x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zanelli J, Mollon J, Sandin S, Morgan C, Dazzan P, Pilecka I, Reis Marques T, David AS, Morgan K, Fearon P, Doody GA, Jones PB, Murray RM, Reichenberg A. Cognitive change in schizophrenia and other psychoses in the decade following the first episode. Am J Psychiatry. 2019;176:811–819. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2019.18091088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shi C, Kang L, Yao S, Ma Y, Li T, Liang Y, Cheng Z, Xu Y, Shi J, Xu X, Zhang C, Franklin DR, Heaton RK, Jin H, Yu X. The MATRICS consensus cognitive battery (MCCB): co-norming and standardization in China. Schizophr Res. 2015;169:109–115. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2015.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nuechterlein KH, Green MF, Kern RS, Baade LE, Barch DM, Cohen JD, Essock S, Fenton WS, Frese FJ, 3rd, Gold JM, Goldberg T, Heaton RK, Keefe RS, Kraemer H, Mesholam-Gately R, Seidman LJ, Stover E, Weinberger DR, Young AS, Zalcman S, Marder SR. The MATRICS consensus cognitive battery, part 1: test selection, reliability, and validity. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165:203–213. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07010042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lees J, Applegate E, Emsley R, Lewis S, Michalopoulou P, Collier T, Lopez-Lopez C, Kapur S, Pandina GJ, Drake RJ. Calibration and cross-validation of MCCB and CogState in schizophrenia. Psychopharmacology. 2015;232:3873–3882. doi: 10.1007/s00213-015-3960-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rodriguez-Jimenez R, Santos JL, Dompablo M, Santabárbara J, Aparicio AI, Olmos R, Jiménez-López E, Sánchez-Morla E, Lobo A, Palomo T, Kern RS, Green MF, Nuechterlein KH, García-Fernández L. MCCB cognitive profile in Spanish first episode schizophrenia patients. Schizophr Res. 2019;211:88–92. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2019.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Young JW, Amitai N, Geyer MA. Behavioral animal models to assess pro-cognitive treatments for schizophrenia. In: Geyer MA, Gross G, editors. Handbook of experimental pharmacology. Springer: Berlin; 2012. pp. 39–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kilic FS, Kulluk D, Musmul A. Effects of dehydroepiandrosterone in amphetamine-induced schizophrenia models in mice. Neurosciences (Riyadh, Saudi Arabia) 2014;19:100–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nenadic I, Dietzek M, Schönfeld N, Lorenz C, Gussew A, Reichenbach JR, Sauer H, Gaser C, Smesny S. Brain structure in people at ultra-high risk of psychosis, patients with first-episode schizophrenia, and healthy controls: a VBM study. Schizophr Res. 2015;161:169–176. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2014.10.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hirjak D, Kubera KM, Wolf RC, Thomann AK, Hell SK, Seidl U, Thomann PA. Local brain gyrification as a marker of neurological soft signs in schizophrenia. Behav Brain Res. 2015;292:19–25. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2015.05.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Van Rheenen TE, Cropley V, Zalesky A, Bousman C, Wells R, Bruggemann J, Sundram S, Weinberg D, Lenroot RK, Pereira A, Shannon Weickert C, Weickert TW, Pantelis C. Widespread volumetric reductions in schizophrenia and schizoaffective patients displaying compromised cognitive abilities. Schizophr Bull. 2018;44:560–574. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbx109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA. The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1987;13:261–276. doi: 10.1093/schbul/13.2.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nuechterlein KH, Barch DM, Gold JM, Goldberg TE, Green MF, Heaton RK. Identification of separable cognitive factors in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2004;72:29–39. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2004.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dahnke R, Yotter RA, Gaser C. Cortical thickness and central surface estimation. Neuroimage. 2013;65:336–348. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.09.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kubera KM, Schmitgen MM, Hirjak D, Wolf RC, Orth M. Cortical neurodevelopment in pre-manifest Huntington’s disease. NeuroImage Clin. 2019 doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2019.101913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nenadic I, Maitra R, Dietzek M, Langbein K, Smesny S, Sauer H, Gaser C. Prefrontal gyrification in psychotic bipolar I disorder vs. schizophrenia. J Affect Disord. 2015;185:104–107. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stone WS, Cai B, Liu X, Grivel MM, Yu G, Xu Y, Ouyang X, Chen H, Deng F, Xue F, Li H, Lieberman JA, Keshavan MS, Susser ES, Yang LH, Phillips MR. Association between the duration of untreated psychosis and selective cognitive performance in community-dwelling individuals with chronic untreated schizophrenia in rural China. JAMA Psychiat. 2020;77:1116–1126. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.1619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nuechterlein KH, Ventura J, Subotnik KL, Bartzokis G. The early longitudinal course of cognitive deficits in schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry. 2014;75(Suppl 2):25–29. doi: 10.4088/JCP.13065.su1.06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sponheim SR, Jung RE, Seidman LJ, Mesholam-Gately RI, Manoach DS, O'Leary DS, Ho BC, Andreasen NC, Lauriello J, Schulz SC. Cognitive deficits in recent-onset and chronic schizophrenia. J Psychiatr Res. 2010;44:421–428. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2009.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mihaljević-Peleš A, Bajs Janović M, Šagud M, Živković M, Janović Š, Jevtović S. Cognitive deficit in schizophrenia: an overview. Psychiatr Danub. 2019;31:139–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Musil R, Spellmann I. Pharmacogenetics and cognitive symptoms in schizophrenia patients treated with antipsychotics. Pharmacogenomics. 2018;19:927–930. doi: 10.2217/pgs-2018-0083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fan F, Xiang H, Tan S, Yang F, Fan H, Guo H, Kochunov P, Wang Z, Hong LE, Tan Y. Subcortical structures and cognitive dysfunction in first episode schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res Neuroimaging. 2019;286:69–75. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2019.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cao A, Shen T, Lis H, Wu C, Cabe M, Mellor D, Byrne L, Zhang J, Huang J, Peng D, Xu Y. Dysfunction of cognition patterns measured by MATRICS Consensus Cognitive Battery (MCCB) among first episode schizophrenia patients and their biological parents. Shanghai Arch Psychiatry. 2017 doi: 10.11919/j.issn.1002-0829.216117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sanjuan J, Prieto L, Olivares JM, Ros S, Montejo A, Ferrer F, Mayoral F, González-Torres MA, Bousoño M. GEOPTE Scale of social cognition for psychosis. Actas espanolas de psiquiatria. 2003;31:120–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pelizza L, Poletti M, Azzali S, Garlassi S, Scazza I, Paterlini F, Chiri LR, Pupo S, Raballo A. Subjective experience of social cognition in young people at ultra-high risk of psychosis: a 2-year longitudinal study. Nord J Psychiatry. 2021;75:97–108. doi: 10.1080/08039488.2020.1799430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pelizza L, Azzali S, Garlassi S, Scazza I, Paterlini F, Rocco LC, Poletti M, Pupo S, Raballo A. A 2-year longitudinal study on subjective experience of social cognition in young people with first episode psychosis. Actas espanolas de psiquiatria. 2020;48:287–301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Song X, Quan M, Lv L, Li X, Pang L, Kennedy D, Hodge S, Harrington A, Ziedonis D, Fan X. Decreased cortical thickness in drug naïve first episode schizophrenia: in relation to serum levels of BDNF. J Psychiatr Res. 2015;60:22–28. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2014.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Takayanagi Y, Sasabayashi D, Takahashi T, Furuichi A, Kido M, Nishikawa Y, Nakamura M, Noguchi K, Suzuki M. Reduced cortical thickness in schizophrenia and schizotypal disorder. Schizophr Bull. 2020;46:387–394. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbz051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Millan MJ, Loiseau F, Dekeyne A, Gobert A, Flik G, Cremers TI, Rivet JM, Sicard D, Billiras R, Brocco M. S33138 (N-[4-[2-[(3aS,9bR)-8-cyano-1,3a,4,9b-tetrahydro[1] benzopyrano[3,4-c]pyrrol-2(3H)-yl)-ethyl]phenyl-acetamide), a preferential dopamine D3 versus D2 receptor antagonist and potential antipsychotic agent: III actions in models of therapeutic activity and induction of side effects. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2008 doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.134536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen YH, Howell B, Edgar JC, Huang M, Kochunov P, Hunter MA, Wootton C, Lu BY, Bustillo J, Sadek JR, Miller GA, Cañive JM. Associations and heritability of auditory encoding, gray matter, and attention in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2019;45:859–870. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sby111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hartberg CB, Lawyer G, Nyman H, Jönsson EG, Haukvik UK, Saetre P, Bjerkan PS, Andreassen OA, Hall H, Agartz I. Investigating relationships between cortical thickness and cognitive performance in patients with schizophrenia and healthy adults. Psychiatry Res. 2010;182:123–133. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2010.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ehrlich S, Brauns S, Yendiki A, Ho BC, Calhoun V, Schulz SC, Gollub RL, Sponheim SR. Associations of cortical thickness and cognition in patients with schizophrenia and healthy controls. Schizophr Bull. 2012;38:1050–1062. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbr018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Takahashi T, Wood SJ, Yung AR, Nelson B, Lin A, Yücel M, Phillips LJ, Nakamura Y, Suzuki M, Brewer WJ, Proffitt TM, McGorry PD, Velakoulis D, Pantelis C. Altered depth of the olfactory sulcus in ultra high-risk individuals and patients with psychotic disorders. Schizophr Res. 2014;153:18–24. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2014.01.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Takahashi T, Nakamura Y, Nakamura K, Ikeda E, Furuichi A, Kido M, Kawasaki Y, Noguchi K, Seto H, Suzuki M. Altered depth of the olfactory sulcus in first-episode schizophrenia. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2013;40:167–172. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2012.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.MacKinley ML, Sabesan P, Palaniyappan L. Deviant cortical sulcation related to schizophrenia and cognitive deficits in the second trimester. Transl Neurosci. 2020;11:236–240. doi: 10.1515/tnsci-2020-0111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ridderinkhof KR, Ullsperger M, Crone EA, Nieuwenhuis S. The role of the medial frontal cortex in cognitive control. Science. 2004;306:443–447. doi: 10.1126/science.1100301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yan W, Zhang R, Zhou M, Lu S, Li W, Xie S, Zhang N. Relationships between abnormal neural activities and cognitive impairments in patients with drug-naive first-episode schizophrenia. BMC Psychiatry. 2020;20:283. doi: 10.1186/s12888-020-02692-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Misiak B, Stańczykiewicz B, Wiśniewski M, Bartoli F, Carra G, Cavaleri D, Samochowiec J, Jarosz K, Rosińczuk J, Frydecka D. Thyroid hormones in persons with schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2021;111:110402. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2021.110402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Huang W, Li YH, Huang SQ, Chen H, Li ZF, Li XX, Li XS, Cheng Y. Serum progesterone and testosterone levels in schizophrenia patients at different stages of treatment. J Mol Neurosci. 2021;71:1168–1173. doi: 10.1007/s12031-020-01739-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tharoor H, Mohan G, Gopal S. Title of the article: sex hormones and psychopathology in drug naïve schizophrenia. Asian J Psychiatr. 2020;52:102042. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bryll A, Skrzypek J, Krzyściak W, Szelągowska M, Śmierciak N, Kozicz T, Popiela T. Oxidative-antioxidant imbalance and impaired glucose metabolism in schizophrenia. Biomolecules. 2020 doi: 10.3390/biom10030384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data sets used and/or analysed during the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.