Abstract

Identification of mycobacteria to the species level by growth-based methodologies is a process that has been fraught with difficulties due to the long generation times of mycobacteria. There is an increasing incidence of unusual nontuberculous mycobacterial infections, especially in patients with concomitant immunocompromised states, which has led to the discovery of new mycobacterial species and the recognition of the pathogenicity of organisms that were once considered nonpathogens. Therefore, there is a need for rapid and sensitive techniques that can accurately identify all mycobacterial species. Multiple-fluorescence-based PCR and subsequent single-strand conformation polymorphism (SSCP) analysis (MF-PCR-SSCP) of four variable regions of the 16S rRNA gene were used to identify species-specific patterns for 30 of the most common mycobacterial human pathogens and environmental isolates. The species-specific SSCP patterns generated were then entered into a database by using BioNumerics, version 1.5, software with a pattern-recognition capability, among its multiple uses. Patient specimens previously identified by 16S rRNA gene sequencing were subsequently tested by this method and were identified by comparing their patterns with those in the reference database. Fourteen species whose SSCP patterns were included in the database were correctly identified. Five other test organisms were correctly identified as unique species or were identified by their closest relative, as they were not in the database. We propose that MF-PCR-SSCP offers a rapid, specific, and relatively inexpensive identification tool for the differentiation of mycobacterial species.

The emergence of the AIDS epidemic and the growing rate of iatrogenic immunosuppression have rapidly increased the incidence of disease caused by nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) (4, 8). The significance of isolation of NTM in the laboratory often remains unclear. There is, however, an increasing awareness of their potential pathogenicities and even of the pathogenicities of mycobacterial species such as members of the Mycobacterium terrae complex that were previously considered nonpathogenic (23). In addition, 19 new species of mycobacteria have been described in the literature in the last 5 years, bringing the total number of validly published mycobacterial species to greater than 90. With these increases in the incidences of tuberculosis and other infections caused by NTM, there is a growing need for more specific identification, particularly since infections caused by different Mycobacterium species often require different treatment regimens (22).

Routine diagnosis of mycobacterial infection in clinical samples is based on the presence of acid-fast-stained bacilli on microscopy and is confirmed by culture and biochemical testing and with commercial molecular diagnostic kits. In addition, many cultures are slowly growing, and identification to the species level can take up to 4 to 8 weeks. Recently developed techniques provide more reliable means of species identification in comparison with conventional testing. High-performance liquid chromatography, which is used to differentiate species by lipid analysis (2), requires isolation of a pure culture, thus necessitating at least 2 to 4 weeks for completion. AccuProbe (Gen-Probe, Inc., San Diego, Calif.) is an ideal choice for the rapid detection of M. tuberculosis and M. avium complexes, M. kansasii, and M. gordonae, although this limited range does not recognize other NTM. PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis of the hsp65 gene is a relatively new technique that is increasingly being used for the differentiation of mycobacteria (3, 19). Sequence-based identification, such as with the 16S rRNA (10, 17), recA (1), rpoB (9), or dnaJ (18) gene is more definitive and allows analyses of phylogenetic relationships. These approaches, however, may not yet be considered efficient to the point of being implemented in most clinical laboratories.

The 16S rRNA gene, whose use is considered a “gold standard” for bacterial identification, is an ideal choice as it contains both conserved sequence regions flanking highly variable regions (25), which allows PCR amplification of these variable regions. Available sequence databases such as GenBank are more comprehensive for this gene than any other gene for the purpose of species identification. Direct sequencing of the 16S rRNA gene can reliably differentiate all mycobacteria, with the exception of members of the M. tuberculosis complex or M. gastri and M. kansasii, down to the species level.

An alternative to sequencing is single-strand conformation polymorphism (SSCP) analysis, developed in 1989 (12), which uses small sequences of a target gene that has been amplified by PCR. Fragments are heat denatured to create single strands, and the single strands are subsequently renatured, causing the strands to adopt “tertiary” conformations based on their base sequences. Thus, fragments with different base sequences have different conformations. For analysis, these fragments are separated by electrophoresis with a nondenaturing gel, in which each fragment will consistently travel at a unique rate even when fragments are of identical size. This method was primarily designed to detect sequence mutations, including single base substitutions, in genomic DNA (12). SSCP analysis of PCR-amplified fragments of the 16S rRNA gene has more recently been used as an alternative to genomic sequencing for the identification of bacterial species (5, 20, 21, 24).

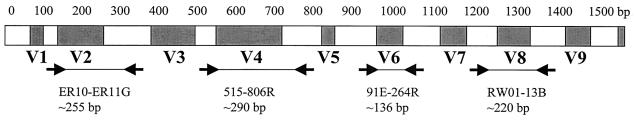

The use of a fluorescence-based capillary electrophoresis system for SSCP analysis (5, 21) has also contributed to the efficiency of the methodology and reliability of analysis. In the study described here, we used this technique for the identification of mycobacteria species by using four pairs of fluorescent primers that amplify four double-stranded fragments containing variable regions of the 16S rRNA gene (Fig. 1) and subsequently analyzing their SSCP patterns. This may provide a technique that is rapid, can be easily standardized, is computer assisted, and has a relatively low cost following the initial purchase of the equipment.

FIG. 1.

Regions of 16S rRNA gene amplified and run on SSCP. Primers are indicated by arrows. Shaded areas represent hypervariable regions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

A total of 40 strains encompassing 30 mycobacterial species were used for the initial reference database (see Tables 2 and 3). Selected patient strains (n=19), received for identification at the National Reference Centre for Mycobacteriology, were used to test the ability of multiple-fluorescence-based PCR–SSCP analysis (MF-PCR-SSCP) to identify unknown organisms. These specimens had previously been identified by both conventional biochemical tests and sequencing of the 16S rRNA gene. The study was conducted in a blinded fashion, in which the identity of the organism was made available to the researcher only after the organism had been identified by SSCP analysis.

TABLE 2.

SSCP pattern determination based on electrophoretic mobility of PCR producta

| Species | Strain | No. of tests run | Relative mobility (SD)

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 91E | 264 | ER10 | ER11G | RWO1 | 13B | 515 | 806R | |||

| M. avium | ATCC 35717 | 6 | 87.5 (0.7) | 105.1 (0.5) | 227.5 (0.8) | 263.1 (0.7) | 187.5 (0.4) | 235.4 (0.9) | 232.5 (1.0) | 313.4 (0.4) |

| ATCC 25921T | 1 | 86.9 | 104.6 | 227.4 | 261.9 | 187.5 | 236.1 | 231.8 | 313.7 | |

| M. chelonae | ATCC 35752T | 6 | 97.5 (0.7) | 126.8 (0.3) | 218.4 (0.5) | 249.2 (0.8) | 189.8 (0.3) | 231.0 (1.1) | 246.8 (0.9) | 307.6 (0.3) |

| ATCC 35751 | 1 | 97.6 | 126.5 | 218.9 | 249.3 | 189.6 | 231.4 | 246.3 | 307.9 | |

| M. fortuitum | ATCC 6842 | 6 | 88.5 (0.8) | 106.0 (0.5) | 228.0 (1.1) | 261.0 (0.8) | 182.7 (0.2) | 230.8 (1.3) | 245.8 (0.8) | 306.7 (0.3) |

| ATCC 6841T | 1 | 88.2 | 106.3 | 227.5 | 260.1 | 182.7 | 231.5 | 244.4 | 306.8 | |

| M. gordonae | ATCC 35756 | 6 | 86.3 (0.3) | 102.6 (0.3) | 220.7 (1.2) | 258.2 (1.0) | 182.1 (0.3) | 225.4 (1.1) | 232.5 (0.7) | 314.5 (0.5) |

| ATCC 35820 | 1 | 86.5 | 102.8 | 219.5 | 257.1 | 182.1 | 227.2 | 232.1 | 314.7 | |

| M. intracellulare | ATCC 13950T | 6 | 86.9 (0.7) | 105.5 (1.0) | 229.0 (0.9) | 272.5 (1.0) | 187.8 (0.2) | 233.5 (1.0) | 232.2 (0.7) | 313.3 (0.4) |

| ATCC 25122 | 1 | 86.9 | 104.6 | 228.6 | 271.1 | 187.8 | 234.7 | 231.9 | 313.6 | |

| M. kansasii | ATCC 12478T | 6 | 86.8 (0.3) | 104.6 (0.3) | 220.1 (1.0) | 257.5 (1.0) | 181.9 (0.3) | 225.2 (0.9) | 232.2 (0.6) | 313.4 (0.4) |

| ATCC 35775 | 1 | 87.1 | 104.7 | 219.3 | 256.4 | 182.1 | 226.8 | 231.8 | 313.7 | |

| M. marinum | ATCC 927T | 6 | 86.6 (0.7) | 104.3 (0.6) | 220.1 (0.7) | 261.6 (0.7) | 182.9 (0.3) | 223.4 (1.1) | 232.1 (1.0) | 313.5 (0.5) |

| ATCC 11564 | 1 | 86.9 | 104.6 | 220.2 | 260.7 | 182.8 | 224.9 | 231.9 | 313.6 | |

| M. terrae | EB1614 | 6 | 86.7 (0.6) | 102.6 (0.4) | 232.0 (0.8) | 265.1 (0.5) | 182.6 (0.4) | 227.6 (1.1) | 249.2 (0.6) | 318.5 (0.7) |

| ATCC 15755T | 1 | 86.6 | 102.5 | 231.7 | 261.1 | 182.8 | 229.1 | 248.5 | 318.9 | |

| M. tuberculosis | ATCC 25177 | 6 | 87.2 (0.8) | 105.4 (0.9) | 222.6 (0.7) | 263.5 (0.8) | 178.0 (0.4) | 222.8 (1.0) | 232.3 (1.2) | 313.4 (0.7) |

| ATCC 27294T | 1 | 86.4 | 104.9 | 221.9 | 262.4 | 177.6 | 225.6 | 232.0 | 313.7 | |

| M. xenopi | ATCC 19250T | 6 | 87.5 (0.9) | 110.7 (0.6) | 218.9b (0.3) | 265.9 (0.6) | 183.5 (0.2) | 235.5 (1.0) | 239.9 (0.9) | 311.1 (0.4) |

| 227.4 (0.8) | ||||||||||

| ATCC 35841 | 1 | 88.4 | 111.6 | 218.1 | 265.5 | 183.3 | 233.9 | 237.8 | 311.9 | |

| 227.4 | ||||||||||

One strain per species was tested six times, for which the standard deviation was determined, and a second strain was tested once for intraspecies reproducibility.

M. xenopi yielded two peaks corresponding to the ER10 primer.

TABLE 3.

Average electrophoretic mobility values of the peaks detected by the fluorescence-labeled primers, in order of retention times, for all additional strain

| Species group and species | Strain | No. of tests run | Avg relative mobility

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 91E | 264 | ER10 | ER11G | RW01 | 13B | 515 | 806R | |||

| Slow growers | ||||||||||

| M. asiaticum | ATCC 25276T | 2 | 87.1 | 103.3 | 221.2 | 257.5 | 182.0 | 228.1 | 230.3 | 314.6 |

| M. branderi | ATCC 51789T | 2 | 87.7 | 101.6 | 232.2 | 264.7 | 181.4 | 234.1 | 242.3 | 323.5 |

| M. celatum | ATCC 51131T | 2 | 88.8 | 106.7 | 237.3 | 268.8 | 182.1 | 232.8 | 242.1 | 323.3 |

| M. flavescens | ATCC 14474T | 1 | 89.0 | 106.7 | 233.2 | 267.1 | 182.4 | 232.0 | 243.5 | 310.7 |

| M. gastri | ATCC 15754T | 2 | 87.6 | 105.1 | 218.8 | 256.4 | 182.1 | 228.0 | 229.8 | 314.7 |

| M. lentiflavum | ATCC 51985T | 1 | 87.4 | 103.9 | 230.2 | 265.3 | 182.3 | 231.7 | 236.0 | 295.9 |

| M. malmoense | ATCC 29571T | 2 | 87.5 | 105.3 | 218.9 | 256.4 | 155.6 | 232.6 | 230.5 | 317.5 |

| M. nonchromogenicum | ATCC 19531 | 2 | 82.4 | 106.2 | 228.5 | 263.4 | 187.5 | 221.1 | 234.3 | 317.6 |

| M. scrofulaceum | ATCC 19981T | 2 | 87.1 | 105.1 | 219.5 | 260.6 | 182.5 | 232.9 | 230.8 | 314.5 |

| M. shimoidei | ATCC 27962T | 2 | 87.4 | 104.8 | 228.3 | 262.4 | 183.4 | 234.8 | 238.7 | 313.2 |

| M. simiae | ATCC 25275T | 2 | 87.3 | 103.3 | 222.8 | 259.1 | 182.5 | 232.8 | 235.9 | 296.3 |

| M. szulgai | ATCC 35799T | 2 | 87.2 | 105.1 | 221.5 | 257.3 | 181.8 | 228.3 | 230.3 | 314.6 |

| M. triplex | ATCC 700071T | 1 | 87.7 | 103.5 | 223.1 | 262.3 | 182.4 | 234.4 | 235.9 | 296.8 |

| M. triviale | ATCC 23292T | 2 | 82.4 | 106.4 | 220.9 | 263.7 | 182.8 | 232.1 | 237.5 | 313.2 |

| M. ulcerans | ATCC 19423T | 1 | 88.1 | 105.5 | 218.7 | 261.2 | 182.1 | 220.3 | 230.9 | 314.9 |

| Rapid growers | ||||||||||

| M. abscessus | ATCC 19977T | 2 | 88.3 | 104.5 | 218.0 | 247.7 | 188.8 | 232.0 | 244.2 | 308.0 |

| M. mucogenicum | ATCC 49650T | 1 | 87.0 | 103.5 | 226.2 | 259.2 | 183.0 | 231.6 | 244.7 | 308.7 |

| M. peregrinum | ATCC 14467T | 2 | 86.1 | 102.3 | 226.8 | 257.1 | 182.4 | 232.4 | 243.3 | 307.5 |

| M. smegmatis | ATCC 19420T | 2 | 87.0 | 103.3 | 226.0 | 260.8 | 182.4 | 232.2 | 243.6 | 307.3 |

| M. thermoresistibile | ATCC 19527T | 2 | 86.9 | 103.1 | 228.9 | 266.4 | 186.4 | 221.9 | 243.0 | 308.8 |

Preparation of DNA.

All strains were grown on Lowenstein-Jensen agar slants or Middlebrook 7H10 agar plates at 30 or 37°C, depending on the requirement of the species. The equivalent of one large colony of each organism was suspended in 1 ml of distilled water and boiled at 100°C for 10 min for inactivation of mycobacteria. The organism was then mechanically lysed with a Mini Bead-Beater (Biospec Products, Bartlesville, Okla.). The lysate was then centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 2 min, and the supernatant was transferred to a new sterile tube and stored at −20°C until required for PCR.

DNA amplification.

Two duplex PCRs were performed, each containing four different fluorescent primers. Each mixture contained 5 μl of crude DNA lysate (≈10 ng of DNA); 2.5 mM MgCl2 PCR buffer (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Baie d'Urfé, Quebec, Canada); dCTP, dGTP, dATP, and dTTP each at a concentration of 200 μM; and 2.5 U of Taq DNA polymerase (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). Fluorescent primers (Table 1, Fig. 1) (Life Technologies, Burlington, Ontario, Canada) were added to each of the two reaction mixtures, which were brought to a final volume of 50 μl with sterile distilled water. The PCR was performed with the Perkin-Elmer GeneAmp PCR system 2400 with a cycle of 94°C for 5 min and 30 cycles of 94, 55, and 72°C for 1 min each; the mixture was then incubated at 72°C for 10 min for final extension and held at 4°C until SSCP analysis was performed.

TABLE 1.

16S rRNA gene primers used for MF-PCR-SSCP

| Reaction mixture and 16S rRNA gene region amplified | Primer | Direction | Labela | Oligonucleotide sequence | Final concn (μM) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mixture A | ||||||

| V6 | 91E(G) | Forward | 5′-HEX | 5′-TCA AAG GAA TTG ACG GGG GC-3′ | 1 | 14 |

| V6 | 264 | Reverse | 6-FAM | 5′-TGC ACA CAG GCC ACA AGG GA-3′ | 1 | 10 |

| V2 | ER10 | Forward | 5′-HEX | 5′-GGC GGA CGG GTG AGT AA-3′ | 0.5 | 24 |

| V2 | ER11G | Reverse | 6-FAM | 5′-GGA CTG CTG CCT CCC GTA G-3′ | 0.5 | 24 |

| Mixture B | ||||||

| V8 | RW01 | Forward | 6-FAM | 5′-AAC TGG AGG AAG GTG GGG AT-3′ | 1 | 6 |

| V8 | 13B | Reverse | 5′-HEX | 5′-AGG CCC GGG AAC GTA TTC AC-3′ | 1 | 14 |

| V4 | 515 | Forward | 5′-HEX | 5′-TGC CAG CAG CCG CGG TAA-3′ | 1 | 14 |

| V4 | 806R | Reverse | 6-FAM | 5′-GGA CTA CCA GGG TAT CTA AT-3′ | 1 | 14 |

5′-HEX was detected as a green peak; 6-FAM was detected as a blue peak.

SSCP electrophoresis.

SSCP electrophoresis was performed with the ABI PRISM 310 Genetic Analyzer (PE Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.). The two PCR mixtures were run in two separate sample tubes. The PCR product was diluted 1:15 in TE buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, 1 mM EDTA [pH 8.0]). One microliter of this diluted product was added to 11.5 μl of the SSCP analysis master mixture (10.5 μl of deionized formamide, 1.0 μl of GeneScan 500 [ROX] size standard [Applied Biosystems]). The samples were subsequently denatured by heating at 95°C for 2 min and were immediately cooled on ice for 5 min prior to loading onto the Genetic Analyzer. The replaceable polymer used was a 4% nondenaturing SSCP analysis polymer (2.86 g of 7% GeneScan polymer [Applied Biosystems], 0.5 g of glycerol, 0.5 g of 10× Tris-borate-EDTA [TBE], 1.64 g of sterile distilled water). The anode-cathode buffer consisted of a 10% glycerol–1× TBE solution. A capillary (47 cm by 50 μm [inner diameter]) was used, and the electrophoresis conditions were set at a 10-s injection time, a 7-kV injection voltage, a 13-kV electrophoresis voltage, a 120-s syringe pump time, a constant temperature of 30°C, and a 24-min collection time. The retention times of the phosphoramidite (HEX)- or 6-carboxyfluorescein (FAM)-labeled fragments were determined by the electrophoretic mobility value relative to the electrophoretic mobility for the ROX-labeled internal standard, shown as red peaks, obtained with the ABI Prism 310 GeneScan Analysis Software (Applied Biosystems). Arbitrary values assigned to the internal standard peaks are indicated in Fig. 2. M. tuberculosis ATCC 25177 (H37Ra) was used as a positive control with each run to ensure the reproducibility of SSCP analysis, and a negative control consisting of water was included in each PCR run and was analyzed by SSCP analysis to rule out PCR contamination and background fluorescence.

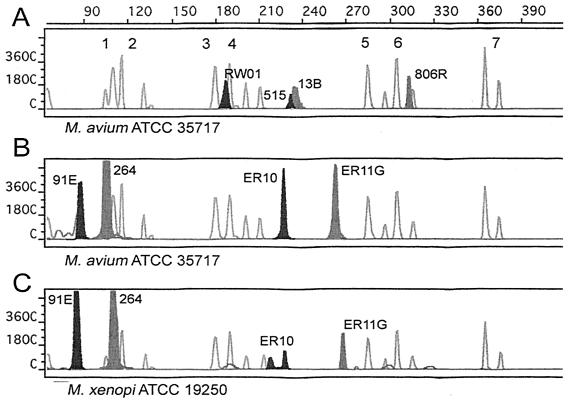

FIG. 2.

MF-PCR-SSCP of M. avium ATCC 35717 with 515-806R and RW01-13B (A) and 91E-264 and ER10-ER11G (B) and of M. xenopi ATCC 19250 with 91E-264 and ER10-ER11G (C). Hollow peaks represent the internal standard, to which arbitrary electrophoretic mobility values were assigned as follows: peak 1, 110; peak 2, 116; peak 3, 180; peak 4, 190; peak 5, 285; peak 6, 305; and peak 7, 365.

Sensitivity.

A TD-700 Fluorometer (Turner Designs, Sunnyvale, Calif.) in conjunction with the PicoGreen assay (Molecular Probes, Eugene, Oreg.) was used to measure the double-stranded DNA concentration in the lysate used as the positive control. The control lysate was diluted to concentrations of 5, 2.5, 1.25, 0.5, 0.25, and 0.05 ng/μl, 5 μl of which was used in each PCR mixture, for a total of 25, 10, 6.25, 2.5, 1.25, and 0.25 ng of DNA per reaction mixture. SSCP analysis was run for each PCR product by using a 1:15 dilution of PCR product, as for the standard method described above, as well as by using a 1:10 dilution. The lowest detectable concentrations were determined by capillary electrophoresis.

Analysis.

Ten species were run six times each to ensure run-to-run reproducibility and were used to calculate the variability of individual primer peaks. For these 10 species, one additional strain was tested to ensure intraspecies reproducibility. Twenty other species were tested at least once; most were tested twice. SSCP analysis patterns were exported to a software program, BioNumerics, version 1.5 (Applied Maths, Kortrijk, Belgium), that was used to automate the analysis of the results of SSCP analysis. The SSCP patterns for each species, which consisted of eight retention times representative of each primer-labeled PCR product, were entered into a database as a separate experiment file. Band matching was preformed by classifying the retention times for each primer into categories on the basis of a 0.5% position tolerance, and from this a composite data set was created and stored. Unknown SSCP patterns were entered into the BioNumerics program in a similar manner and were then identified by creating a dendrogram by simple matching of the retention time categories and comparison of the unknown patterns against the database.

RESULTS

With the standard 1:15 PCR product dilution that we used for the preparation used for SSCP analysis, the sensitivity of detection upon SSCP analysis was 1.25 ng of template DNA in the PCR mixture. With a 1:10 PCR product dilution for the preparation used for SSCP analysis, the sensitivity of detection was 0.25 ng of template DNA. Dilution of the PCR product is required to reduce the background fluorescence to the point where only the PCR fragments and standard peaks are detectable.

The SSCP patterns for 30 species of mycobacteria were determined (Tables 2 and 3). The SSCP patterns were defined as the average retention times relative to the retention time for the internal standard. Each duplex PCR yielded a gel file from SSCP analysis with four peaks (two green peaks and two blue peaks), each representing one of the fluorescence-labeled primers, and an internal standard (multiple red peaks) (Fig. 2A and B). Variable regions of the 16S rRNA gene amplified by both duplex PCRs include regions V2, V4, V6, and V8 (11). Twenty-six of the 30 mycobacterial species yielded a unique pattern of eight peaks; the exceptions were M. kansasii and M. gastri, which had identical SSCP patterns, and M. gordonae and M. asiaticum, which also had identical SSCP patterns. All patterns were consistent over multiple runs with the same species (Table 2) and have been expressed as the average retention time for each peak. M. xenopi demonstrated a unique pattern in that it yielded two peaks corresponding to the ER10 primer (Fig. 2C). This pattern was observed in both strains tested, as well as a patient strain.

The species in selected unknown patient samples included 14 established species whose patterns were already present in the database. The remaining five species, two established species and three species that had unique 16S rRNA gene sequences closely related to that of an established species, were not in the database (Table 4). The species in all 14 specimens whose patterns were already included in the database were identified correctly, although two strains of M. gastri could be identified only as M. gastri or M. kansasii, which have the same SSCP profile. The two established species that were not included in the database were M. interjectum and M. goodii. The pattern of M. interjectum was recognized as a new pattern, whereas M. goodii was identified as M. smegmatis (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Identification of strains unknown (blinded study) by MF-PCR-SSCP

| True identificationa | Identification by SSCP analysis | Correlation |

|---|---|---|

| M. xenopi | M. xenopi | Yes |

| M. thermoresistibile | M. thermoresistibile | Yes |

| M. fortuitum | M. fortuitum | Yes |

| M. gastri (two specimens) | M. gastri or M. kansasii | Yes |

| M. triviale | M. triviale | Yes |

| M. triplex (two specimens) | M. triplex | Yes |

| M. lentiflavum | M. lentiflavum | Yes |

| M. marinum (two specimens) | M. marinum | Yes |

| M. simiae (two specimens) | M. simiae | Yes |

| M. branderi | M. branderi | Yes |

| M. goodii | M. smegmatis | See text |

| M. interjectum | Unique pattern closest to M. scrofulaceum | See text |

| M. kansasii subspecies | M. gastri or M. kansasii | See text |

| MCRO 6, closest to M. nonchromogenicum | Unique pattern closest to M. nonchromogenicum | See text |

| Unique, closest to M. flavescens | Unique pattern closest to M. flavescens | See text |

Identification was determined by biochemical testing and partial 16S rRNA gene sequencing (>1,400 bp) by the National Reference Centre for Mycobacteriology.

Three strains whose 16S rRNA sequences did not correspond exactly to those for well-known species were included in the panel of unknown organisms. These were unique species grouped with (or subspecies of) M. kansasii, M. terrae complex, and M. flavescens.

The M. kansasii subspecies was determined by its biochemical characteristics to be M. kansasii, while its 16S rRNA gene sequence identified it as a “genetically distinct subspecies of Mycobacterium kansasii ” (16). This strain was also an M. kansasii AccuProbe-negative variant. All base-pair variations for this particular species compared with the sequence of the M. kansasii type strain are found in regions V1, V3, and V9 of the 16S rRNA gene, none of which are amplified by our method. For this reason, this species was identified by SSCP analysis as M. kansasii or M. gastri.

A species whose 16S rRNA sequence corresponded with that of MCRO 6 (GenBank accession no. X93032) (17) was identified as having a new SSCP pattern closest to that of M. nonchromogenicum. The 16S rRNA sequence of MCRO 6 is closest to that of M. nonchromogenicum, with a 99.4% similarity. Of the regions amplified by this method, SSCP analysis was able to detect a 1-bp variation in the V2 region. Other variations between the two sequences are found at the V3 and V7 regions.

The organism in a specimen that was identified as a unique species on the basis of its 16S rRNA gene sequence but that corresponded to M. flavescens on the basis of phenotypic and biochemical characteristics resulted in a new SSCP pattern, one closest to that of M. flavescens.

DISCUSSION

Since its development in 1989, PCR-SSCP has been recognized as a rapid and effective tool for the detection of mutations and for bacterial identification. SSCP analysis has also previously been used for the identification of mycobacteria (20). However, the previous study was limited because only 10 species were tested by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and subsequent silver staining. In addition to a larger panel of species tested, the primary method used in the present study has been improved through use of an automated DNA sequencer, which reduced the identification time and dramatically improved pattern resolution and analysis. The results of SSCP analysis can be obtained within 30 min following PCR, and with the new capillary electrophoresis systems on the market, 8 or 16 samples can be run at one time, further increasing the turnaround time. Finally, the automated sequencer allows quick and easy computer analysis, the resulting data from which can be transferred for comparison within a computer-generated database.

BioNumerics, version 1.5 (Applied Maths), software was used to create a database of SSCP patterns of mycobacterial reference strains. By using band matching, the BioNumerics software placed the results for each organism in categories on the basis of their peak patterns. Primer peaks with similar retention times were placed in the same category on the basis of a 0.5% position tolerance. This allows the retention times for an unknown organism to be classified into similar categories and then for the organism to be identified by creating a dendrogram by using a simple matching algorithm. Because of overlapping confidence intervals, some organisms are classified together in the same categories (e.g., M. marinum and M. ulcerans). This problem was resolved by manually checking the data in cases in which the BioNumerics software matches an unknown to more than one organism. The standard deviation of each primer peak retention time helped determine that, in general, organisms with a difference in values of <1 were considered identical, organisms with a difference in values of 1 to 2 were considered likely identical, and organisms with a difference in values of ≥3 were considered different. More testing would be required to clarify a cutoff point within the “grey zone,” consisting of a value difference of between 2 and 3.

The use of BioNumerics software for analysis also allows multiple experiments to be searched simultaneously and, hence, allows SSCP patterns to be used in conjunction with other diagnostic tests (e.g., sequencing analysis, biochemical characteristics, sensitivity patterns, restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis, etc.) for a more definitive or comprehensive identification.

The primer pairs selected amplified variable regions of the 16S rRNA gene (regions V2, V4, V6, and V8) to differentiate between species. With a larger number of primer pairs and variable regions amplified, one has a greater chance of distinguishing different species. However, with more primer pairs, the method becomes longer and differentiation between peaks becomes confusing as peaks begin to overlap. The four primer pairs selected for use in this study allowed a satisfactory balance of specificity and ease of analysis. Some species differ from each other only in select regions. For example, M. ulcerans and M. marinum differ from each other by only 1 bp in the region amplified by primers RW01 and 13B. The difference is noticed by a retention time value difference of 3 with the 13B fragment. Primer 13B, along with primer ER10, also helped differentiate M. malmoense from M. szulgai and M. triviale from M. simiae, two pairs of closely related species. Primer pair 91E-264 was included as it amplified the only variable region between M. chelonae and M. abscessus. As primer 91E alone shows the least interspecies variability of all primers tested, it could be used as a nonfluorescent primer along with fluorescent primer 264 to reduce cost. Primers 515 and 806R were required for the differentiation of M. shimoidei and M. fortuitum. Primers ER10 and ER11G proved to be the most useful in recognizing novel patterns and closely related species. Better differentiation of profiles would likely have been obtained had the V3 region been included, and a primer pair for the V3 region could perhaps replace the 515-806R primer pair, although we initially had concerns of peak overlap as the best primers for amplification of the V3 region would have been pC (forward) and pD (reverse) (15), resulting in a ≈200 bp fragment. In retrospect, the retention time differences between complementary strands were so significant that size would likely not have interfered. In fact, overlap sometimes occurred between the 515 and 13B fragments, which are 290 and 220 bp, respectively, but which were easily analyzable due to their different fluorescent labels (Fig. 2A).

Ideally, a single multiplex PCR-SSCP involving all four primer sets would be performed. However, because some of the fragments have similar retention times, this may result in confusion during data analysis. Hence, two primer sets were run in each of two duplex PCR-SSCPs.

The species selected for the development of the SSCP pattern database included known human pathogens as well as commonly isolated environmental species. MF-PCR-SSCP yielded a unique pattern for 26 of the 30 organisms tested in the study. M. gastri and M. kansasii, which have identical 16S rRNA gene sequences, and M. gordonae and M. asiaticum, which are closely related, could not be differentiated by this method. It is surprising that the ER10-ER11G primer pair could not resolve the two latter species, as they share six variations in the region that was amplified. Variability in SSCP patterns according to sequence is arbitrary and cannot be predicted (7). Further optimization of the analytical system, which could include variations in temperature or in glycerol or polymer concentrations, would likely result in the differentiation of these species, although perhaps at the expense of being able to differentiate the others.

The purpose of including unknowns in the study was to determine not only the ability of this method to identify common mycobacterial species but also the ability of this method to detect unusual strains. The spectrum of mycobacterial species isolated in clinical laboratories is larger than what is evident through the use of conventional testing, and genetic methodologies are required for the accurate identification of many NTM. We have included two species not previously included in the SSCP pattern database, as well as three strains with unique 16S rRNA sequences that would normally be identified as the closest relative of the species on the basis of conventional testing in order to test the level of discrimination of the system.

The inability of the method to differentiate M. goodii from M. smegmatis was not surprising. M. goodii was previously a subgroup of M. smegmatis. Variations in the 16S rRNA sequences between these two species are very limited, in which variations of only 2 bp are found in the V2 region amplified by the ER10-ER11G primers. By comparing the SSCP patterns determined for M. smegmatis and M. goodii, the ER10 and ER11G fragments did vary by retention times of 1.2 and 1.4, whereas for all other primer pairs, retention times varied between the two primers by <0.3. However, intraspecies variability in general can attain retention time differences of 1.2 and 1.0 for primers ER10 and ER11G, respectively, and therefore, it is difficult without the testing of more strains to determine if both patterns are discernible from each other.

The database recognized M. interjectum as a new species, although its pattern resembled those of M. scrofulaceum and M. asiaticum more than its pattern resembled that of its closer relative, M. lentiflavum. A tested strain whose 16S rRNA sequence matched that of MCRO 6 varied from M. nonchromogenicum only in the V2 (by 1 bp) and V3 regions. This was reflected by a 3-point variation in the retention time of the ER11G fragment. The recognition of another unique strain by primers ER10-ER11G was demonstrated with a patient strain that was identified phenotypically as M. flavescens. Its 16S rRNA sequence, however, showed several variations along the 16S rRNA gene compared with the sequence of the rRNA gene of the type strain, particularly in the V2 region. Despite these variations, its closest SSCP pattern was correctly identified as that of M. flavescens.

Each fluorescently labeled fragment is expected to yield one peak upon SSCP analysis. An exception to this was demonstrated for M. xenopi, which consistently yielded two peaks corresponding to the fragment containing the labeled ER10 primer (Fig. 2C). These multiple peaks may be due to different stable conformations of the same fragment (7, 12), or M. xenopi may contain two different copies of the 16S rRNA gene, as is known to occur in the slow grower M. celatum (13).

The disadvantages of the methodology described here include the need for stringent measures to prevent PCR contamination, particularly since the gene targeted is universal among all bacteria. Also, a pure specimen is required. While two SSCP patterns may be detected in a single sample, additional peaks only confound the analysis. Although, in general, identification by this method is accurate, instances in which new species present themselves, particularly species closely related to those with a pattern included in the SSCP database, may be missed. Alternatively, new species may be more easily recognized by this methodology than by conventional biochemical testing.

On the basis of the results presented here, it appears that MF-PCR-SSCP of four variable regions of the 16S rRNA gene can serve as a tool for the rapid identification and differentiation of mycobacterial species. The success of this method was demonstrated by its ability to identify organisms with patterns previously entered in the reference database and its ability to recognize new patterns. It is both specific and rapid without being excessively expensive. This method is acceptable for use in most large laboratories, as it requires only minimal training and uses equipment that has become more common in large laboratories. Further investigations would involve expanding the database to include all other species of mycobacteria, performing a larger blinded study to ensure applicability to a laboratory setting, and performing a cost-benefit analysis that compares the method described here to conventional methods.

REFERENCES

- 1.Blackwood K S, He C, Gunton J, Turenne C Y, Wolfe J, Kabani A M. Evaluation of recA sequences for the identification of mycobacterium species. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:2846–2852. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.8.2846-2852.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Butler W R, Jost K C, Kilburn J O. Identification of mycobacteria by high-performance liquid chromatography. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:2468–2472. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.11.2468-2472.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Devallois A, Goh K S, Rastogi N. Rapid identification of mycobacteria to species level by PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis of the hsp65 gene and proposition of an algorithm to differentiate 34 mycobacterial species. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:2969–2973. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.11.2969-2973.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Falkinham J O. Epidemiology of infection by nuntuberculous mycobacteria. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1996;9:177–215. doi: 10.1128/cmr.9.2.177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ghozzi R, Morand P, Ferroni A, Beretti J L, Bingen E, Segonds C, Husson M O, Izard D, Berche P, Gaillard J L. Capillary electrophoresis–single-strand conformation polymorphism analysis for rapid identification of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and other gram-negative nonfermenting bacilli recovered from patients with cystic fibrosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:3374–3379. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.10.3374-3379.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Greisen K, Loeffelholz M, Purohit A, Leong D. PCR primers and probes for the 16S rRNA gene of most species of pathogenic bacteria, including bacteria found in cerebrospinal fluid. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:335–351. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.2.335-351.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hayashi K. PCR-SSCP: a simple and sensitive method for detection of mutations in the genomic DNA. PCR Methods Appl. 1991;1:34–38. doi: 10.1101/gr.1.1.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Horsburgh C J. Epidemiology of disease caused by nontuberculous mycobacteria. Semin Respir Infect. 1996;11:244–251. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim B-J, Lee S-H, Lyu M-A, Kim S-J, Bai G-H, Kim S-J, Chae G-T, Kim E-C, Cha C-Y, Kook Y-H. Identification of mycobacterial species by comparative sequence analysis of the RNA polymerase gene (rpoB) J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:1714–1720. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.6.1714-1720.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kirschner P, Springer B, Vogel U, Meier A, Wrede A, Kiekenbeck M, Bange F, Bottger E. Genotypic identification of mycobacteria by nucleic acid sequence determination: report of a 2-year experience in a clinical laboratory. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:2882–2889. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.11.2882-2889.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Neefs J M, de Peer Van Y, De Rijk P, Chapelle S, De Wachter R. Compilaton of small ribosomal subunit RNA structures. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:3025–3049. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.13.3025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Orita M, Suzuki Y, Sekiya T, Hayashi K. A rapid and sensitive detection of point mutations and genetic polymorphisms using polymerase chain reaction. Genomics. 1989;5:874–879. doi: 10.1016/0888-7543(89)90129-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reischl U, Feldmann K, Naumann L, Gaugler B J, Ninet B, Hirschel B, Emler S. 16S rRNA sequence diversity in Mycobacterium celatum strains caused by presence of two different copies of 16S rRNA gene. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:1761–1764. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.6.1761-1764.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Relman D A, Schmidt T M, MacDermott R P, Falkow S. Identification of the uncultured bacillus of Whipple's disease. N Engl J Med. 1992;327:293–301. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199207303270501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rogall T, Flohr T, Bottger E C. Differentiation of mycobacterial species by direct sequencing of amplified DNA. J Gen Microbiol. 1990;136:1915–1920. doi: 10.1099/00221287-136-9-1915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ross B C, Jackson K, Yang M, Sievers A, Dwyer B. Identification of a genetically distinct subspecies of Mycobacterium kansasii. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:2930–2933. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.11.2930-2933.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Springer B, Stockman L, Teschner K, Roberts G D, Böttger E C. Two-laboratory collaborative study on the identification of mycobacteria: molecular versus phenotypic methods. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:296–303. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.2.296-303.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Takewaki S-I, Katsuko O, Manabe I, Tanimura M, Miyamura K, Nakahara K-I, Yazaki Y, Ohkubo A, Nagai R. Nucleotide sequence comparison of the mycobacterial dnaJ gene and PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis for identification of mycobacterial species. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1994;44:159–166. doi: 10.1099/00207713-44-1-159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Telenti A, Marchesi F, Balz M, Bally F, Bottger E C, Bodmer T. Rapid identification of mycobacteria to the species level by polymerase chain reaction and restriction enzyme analysis. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:175–178. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.2.175-178.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tokue Y, Sugano K, Noda T, Saito D, Shimosato Y, Ohkura H, Kakizoe T, Sekiya T. Identification of mycobacteria by nonradioisotopic single-strand conformation polymorphism analysis. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 1995;23:129–133. doi: 10.1016/0732-8893(95)00198-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Turenne C Y, Witwicki E, Hoban D J, Karlowsky J A, Kabani A. Rapid identification of bacteria from positive blood cultures by fluorescence-based PCR-single stranded conformation polymorphism analysis of the 16S rRNA gene. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:513–520. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.2.513-520.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wallace R J, Glassroth J, Griffith D E, Olivier K N, Cook J L, Gordin F. American Thoracic Society—diagnosis and treatment of disease caused by nontuberculous mycobacteria. Am J Med Crit Care Med. 1997;156:S1–S25. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.156.2.atsstatement. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wayne L G, Sramek H A. Agents of newly recognized or infrequently encountered mycobacterial diseases. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1992;5:1–25. doi: 10.1128/cmr.5.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Widjojoatmodjo M N, Fluit A C, Verhoef J. Molecular identification of bacteria by fluorescence-based PCR–single-strand conformation polymorphism analysis of the 16S rRNA gene. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:2601–2606. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.10.2601-2606.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Woese C. Bacterial evolution. Microbiol Rev. 1987;51:221–271. doi: 10.1128/mr.51.2.221-271.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]