Abstract

Objectives

This study aimed to quantify increases in the medical expenditures of public hospitals associated with changes in service use and prices, which could inform policy efforts to curb the future growth of hospital medical expenditures.

Design

Nationwide and provincial data regarding service volume, service price and intensity of public hospitals’ outpatient and inpatient care from 2008 to 2018 were extracted from the China Health Statistical Yearbooks, and population size data were obtained from the 2019 China Statistical Yearbook.

Methods

A decomposition analysis was performed to measure the relative effects of changes in service use (volume or its subcomponent factors) and service price and intensity on the increase in the inpatient and outpatient total medical expenditures of public hospitals from 2008 to 2018.

Results

After adjusting for price inflation, the total medical expenditure of public hospitals increased by approximately threefold from 2008 to 2018. During this period, the increase in service volume was associated with 67.4% of the observed increase in the total medical expenditures in the inpatient sector and 57.2% of the observed increase in the total medical expenditures in the outpatient sector. Most of the service volume effect is due to an increase in the hospital utilisation rate. The growth in the utilisation rate was associated with 73.7% of the observed growth in the total medical expenditures in the inpatient sector and 60.3% of the observed growth in the total medical expenditures in the outpatient sector.

Conclusion

Service use, rather than price, appears to be the major driver of increases in medical expenditures in Chinese hospitals. An important policy implication for China and other countries with similar drivers is that the effect of controlling price and intensity growth on containing medical costs could be limited and controlling service utilisation growth could be essential.

Keywords: health economics, health policy

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study extends the existing literature by focusing on the drivers of growth in public hospitals’ medical expenditure during the first decade of the new round of health system reform in China.

This study decomposed growth in medical expenditure into changes in its primary policy-relevant constituent factors, that is, service volume and price, and subcomponent factors of service volume.

This study provides region-specific decomposition rates of the sources of the growth in public hospitals’ medical expenditure in 31 provinces, autonomous regions and municipalities in mainland China.

Due to the lack of a price index specific to the health sector in China, this study cannot distinguish between the contributions of the service price and service intensity.

This study did not consider changes in the types of conditions prompting people to visit hospitals and the ageing of the population.

Introduction

Medical cost escalation is a major problem in both developed and low-income and middle-income countries, including China.1 2 Efforts to contain medical expenditure growth may benefit from a better understanding of the underlying drivers of increasing medical costs.

Studies decomposing growth in China’s health expenditure into its constituent parts since the 1990s have revealed different results. Zhai et al’s study used data from China’s National Health Accounts studies and Global Burden of Disease 2013 studies and decomposed the changes in health expenditures by disease into population growth, population ageing, disease prevalence rate, expenditure per case of disease and excess health price inflation. These authors found that 72.6% of the increases in China’s health expenditure between 1993 and 2012 was caused by growth in health expenditure per prevalent case.3 A recent study by Yip et al using China National Health Accounts data decomposed the growth in health spending by healthcare type into an increase in visit volume and an increase in charges per visit or admission. The study showed that the increase in visit volume accounted for approximately 70% of the increase in the total health spending in China between 2008 and 2017, while increases in charges per visit or admission accounted for approximately 30% of the increase.4 These studies examined the drivers of health expenditure growth in China from different perspectives (cost of disease or healthcare) during different periods since the 1990s.

Some existing studies explored spending drivers in the USA,5–7 Switzerland8 and Brazil9 by decomposing growth in spending into its constituent parts while focusing on two or more factors, including population growth, population ageing, disease prevalence, utilisation/quantity and cost/price. Among all these factors in the decomposing models in the existing literature, the two primary factors are quantity and price, and the other factors can be considered the further decomposition of these two factors.

As the main body of China’s health service delivery system, public hospitals accounted for 92.8% of hospital inpatient admissions and 92.6% of hospital ambulatory visits in 2008; the corresponding values decreased to 81.8% and 85.3% in 2018.10 Public hospital medical expenditures accounted for approximately half of the total health expenditures in 2018.10 11 Cost containment in public hospitals has been a key focus of China’s new round of health system reform since 2009.4 12 Public hospital reforms were launched in 2012, including altering provider payment, eliminating drug mark-up and adjusting fee schedules.11 A guidance document to contain excess public hospital medical expenditure growth issued by the central government in 2015 listed 21 monitoring indicators of medical cost control for public hospitals.13 Of these indicators, seven indicators monitor charges per unit of service (charges per visit, admission or case), three indicators monitor service utilisation and the remaining indicators mainly monitor the share of the cost of drugs, diagnostic examinations or medical consumables in medical expenditures. Based on these monitoring indicators, it seems that the assumption underlying policy decisions was that price and intensity were the primary drivers of medical costs. However, these reforms did not reduce the overall medical expenditures.14 15

Our study extends the existing literature by focusing on the drivers of the growth of national and provincial total medical expenditures of public hospitals during the first decade of the new round of health system reform in China. We focused on the growth in medical expenditure of public hospitals because most of the medical spending is by public hospitals and because cost containment in public hospitals is the focus of healthcare delivery reform across China. We decompose growth in medical expenditure into its primary policy-relevant constituent factors to quantify how much of the growth in real total medical expenditure was attributable to changes in service volume versus service price and intensity. We also explored the impact of changes in the subcomponent factors of the service volume, that is, the population size, hospital utilisation rates and the share of service utilisation in public hospitals, on the growth of public hospitals’ real total medical expenditures. One of the main contributions of this study is the provision of the region-specific decomposition rates of 31 provinces, autonomous regions and municipalities in mainland China. The results of this study could inform cost containment policies in China and other countries that experience soaring medical expenditures.

Study data and methods

Data sources

We extracted 11 years of nationwide data and 8 years of provincial data from the China Health Statistical Yearbooks in 2009–2019 published by the National Health Commission (originally called the Ministry of Health).4 16 We obtained aggregative information of public hospital medical expenditures per visit or per admission discharged and outpatient and inpatient service volumes of public and private hospitals per year.10 The nationwide and provincial population size data in specific years between 2008 and 2018 were obtained from the 2019 China Statistical Yearbook, which provides nationwide and provincial population size data from 2008 to 2018.17

We chose 2008 as the base year for the nationwide analysis and 2011 as the base year for the provincial analysis because the earliest available years of nationwide and provincial public hospitals’ service volume and price and intensity data were 2008 and 2011, respectively. Additionally, there were significant policy changes in 2009 and 2012 as mentioned above, rendering 2008 and 2011 appropriate as base years. The year 2018 was selected as the end date for both the nationwide and provincial analyses because the latest data we could obtain during our study period was 2018, which was also the period of the first decade of new round health system reform.

Patient and public involvement

The data used for this study were directly harvested from China Health Statistical Yearbooks and China Statistical Yearbook. Therefore there was no direct patient and public involvement.

Variable definition

In this paper, we use public hospital medical revenue variables as expenditure indicators. According to the interpretation of the indicators in the China Health Statistics Yearbook and previous studies, hospital medical expenditures in this study fall into the following three categories: medical services, drugs and diagnostic examinations/medical consumables.14 All expenditure variables in this study were adjusted for inflation using the economy-wide consumer price index of China from the International Monetary Fund and were reported in Chinese yuan in 2018 prices.18

Table 1 provides the definitions of the variables used in this study. For outpatient care, the service volume was defined as the annual volume of visits to public hospitals; the utilisation rate was defined as annual hospital visits per capita, including public and private hospital visits; the share of public hospitals’ utilisation was defined as the fraction of public hospitals in the number of hospital visits; and price and intensity was defined as the mean expenditure per visit for public hospitals. For inpatient care, the service volume was defined as the annual volume of admissions discharged from public hospitals; the utilisation rate was defined as annual hospital admissions per capita, including public and private hospital admissions; the share of public hospitals’ utilisation was defined as the fraction of public hospitals in the number of hospital admissions; and price and intensity was defined as the mean expenditure per admission discharged from public hospitals.

Table 1.

Definitions of service volume, utilisation rate, share of public hospitals’ utilisation, price and intensity, by type of care

| Care type | Service volume | Utilisation rate | Share of public hospitals’ utilisation | Price and intensity |

| Outpatient | Annual volume of visits to public hospitals in outpatient and emergency departments | Annual hospital (including public and private hospitals) visits per capita | The share of public hospitals in the number of hospital visits. | Public hospitals’ medical expenditure per visit |

| Inpatient | Annual volume of admissions discharged from public hospitals | Annual hospital (including public and private hospitals) admissions per capita | The share of public hospitals in the number of hospital admissions | Public hospitals’ medical expenditure per admission discharged |

Decomposition methods

The total medical expenditure of public hospitals is the product of two factors:(1) service volume and (2) price and intensity, as shown in the following equation:

where y indicates the year; is the total medical expenditure; is the service volume and is the service price and intensity.

To measure the relative effect of each factor, we used the decomposition method described by Das Gupta.19 20 This decomposition was based on the equation above to calculate standardised expenditures for each factor and then calculate their additive contributions to the changes in hospital outpatient or inpatient total medical expenditures from 2008 to 2018. (For a more detailed description of the decomposition method, see online supplemental appendix 1 exhibit 1.1.)

bmjopen-2020-048308supp001.pdf (158.8KB, pdf)

Given that the public hospitals’ service volume can be expressed as the product of the population size, hospital utilisation rate, and share of service utilisation in public hospitals (the share of public hospitals in the number of admissions or visits), its effect on the growth of real total medical expenditures reflects the subcomponent effects of population growth, changes in the utilisation rate and changes in the share of service utilisation in public hospitals. We further explored the impact of changes in the population size, utilisation rate, and share of service utilisation in public hospitals on the growth of total medical expenditure of public hospitals by developing a four-factor decomposition model as follows:

where y indicates the year; is the total medical expenditure of public hospitals; is the population size; is the service volume of all hospitals (including public and private hospitals); is the service volume of public hospitals and is the service price and intensity of public hospital care.

Then, we calculated their additive contributions to the growth of public hospital outpatient or inpatient total medical expenditures from 2008 to 2018. The sum of the contributions of the changes in the population size, utilisation rate, and share of public hospitals’ utilisation was approximately the same as the contribution of the changes in the service volume in the above two-factor decomposition. (For a more detailed description of the four-factor decomposition method, see online supplemental appendix 1 exhibit 1.2.).

Results

Both the inpatient and outpatient real total medical expenditures of public hospitals increased annually from 2008 to 2018 (table 2). In 2018, the inpatient real total medical expenditure increased by 3.6-fold, and the outpatient real total medical expenditure increased 2.9-fold compared with the costs in 2008. The growth rates of inpatient and outpatient real total medical expenditures showed downward trends. Inpatient and outpatient real total medical expenditures increased at average annual rates of 18.2% and 14.4%, respectively, between 2008 and 2013 and decreased to 9.1% and 8.3% between 2013 and 2018. The average annual growth rates of public hospitals’ service volume and service price and intensity also displayed downward trends, while the average annual growth rate of public hospitals’ service volume outpaced that of service price and intensity during the same period.

Table 2.

Medical expenditures and service volumes of public hospital inpatient and outpatient care in China (2008–2018)

| Inpatient | Outpatient | |||||

| Real total medical exp. (billion yuan) | Exp. per admission (yuan) | Admissions* (million) | Real total medical exp. (billion yuan) | Exp. per visit (yuan) | Visits (million) | |

| 2008 | 456.8 | 6678.7 | 68.4 | 285.0 | 172.8 | 1649.1 |

| 2009 | 571.2 | 7344.5 | 77.8 | 338.3 | 191.3 | 1768.9 |

| 2010 | 676.2 | 7789.8 | 86.8 | 380.6 | 203.1 | 1873.8 |

| 2011 | 770.4 | 7960.4 | 96.8 | 426.1 | 207.6 | 2052.5 |

| 2012 | 930.6 | 8224.8 | 113.1 | 497.0 | 217.2 | 2288.7 |

| 2013 | 1054.3 | 8600.1 | 122.6 | 558.6 | 227.5 | 2455.1 |

| 2014 | 1190.1 | 8894.5 | 133.8 | 629.4 | 237.7 | 2647.4 |

| 2015 | 1278.5 | 9345.6 | 136.8 | 675.0 | 248.8 | 2712.4 |

| 2016 | 1406.1 | 9573.9 | 146.9 | 728.1 | 255.7 | 2847.7 |

| 2017 | 1517.6 | 9764.2 | 155.4 | 774.9 | 262.5 | 2952.0 |

| 2018 | 1629.1 | 9976.4 | 163.3 | 830.5 | 272.2 | 3051.2 |

| Annual growth rates (%) | ||||||

| 2008–2013 | 18.2 | 5.2 | 12.4 | 14.4 | 5.6 | 8.3 |

| 2013–2018 | 9.1 | 3.0 | 5.9 | 8.3 | 3.7 | 4.4 |

Expenditures per admission discharged or per visit, admission and visit volume data were extracted from the China Health Statistical Yearbooks in 2009–2019. Total medical expenditure represents the authors’ analysis of data based on the above equation.

*Numbers of inpatients who were discharged from public hospitals.

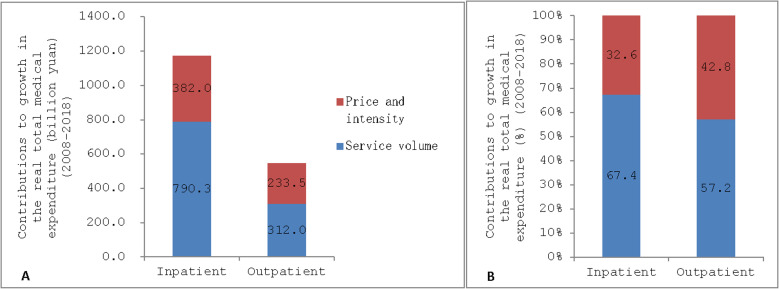

Figure 1 reveals a 1172.3 billion yuan and a 545.5 billion yuan increase in inpatient and outpatient real total medical expenditures, respectively, for public hospitals from 2008 through 2018. (The exchange rate in 2018 was 6.6 Chinese yuan to one US dollar.) From 2008 to 2018, the increase in admission volume was associated with 67.4% (790.3 billion yuan) of the observed increase in inpatient real total medical expenditure, while the change in price and intensity was associated with the remaining 32.6% (382.0 billion yuan). The increase in visit volume was associated with 57.2% (312.0 billion yuan) of the observed increase in outpatient real total medical expenditure, while the change in the service price and intensity was associated with the remaining 42.8% (233.5 billion yuan).

Figure 1.

Contributions of growth in service volume and price and intensity to growth in the real total medical expenditure of public hospitals, 2008–2018. (A) The absolute contribution (billion yuan) of each factor; (B) the relative contribution (%) of each factor. Colours represent the contribution of each factor to the overall growth in real total medical expenditure.

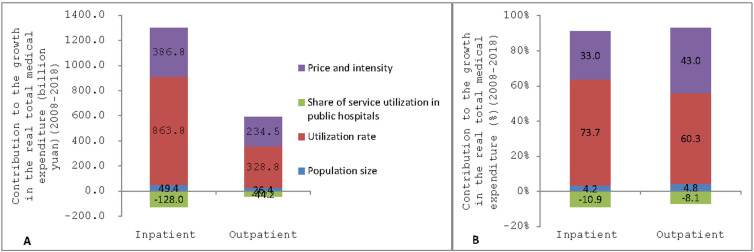

Figure 2 shows growth in the real total medical expenditure associated with changes in each factor in the four-factor decomposition from 2008 to 2018. The increase in utilisation rate contributed 73.7% (863.8 billion yuan of the 1172.0 billion yuan increase) of the growth in the real total medical expenditure on inpatient care, and 60.3% (328.8 billion yuan of the 545.5 billion yuan increase) of the growth in the real total medical expenditure on outpatient care. Population growth was associated with a slight increase in inpatient (4.2%) and outpatient (4.8%) total medical expenditures, while a lower share of public hospitals’ utilisation was associated with a slight reduction in inpatient (10.9%) and outpatient (8.1%) total medical expenditures.

Figure 2.

Growth in the real total medical expenditure of public hospitals associated with changes in each factor in the 4-factor decomposition by type of care, 2008–2018. Growth in the real total medical expenditure of public hospitals from 2008 to 2018 were decomposed into changes in four factors: population size, utilisation rate, share of service utilisation in public hospitals and price and intensity. (A) The absolute contribution (billion yuan) of each factor; (B) the relative contribution (%) of each factor. Colours represent the contribution of each factor to the overall growth in real total medical expenditure. Bars below zero show that the factor contributed to a decrease and bars above zero show an increase.

Regarding public hospitals’ inpatient and outpatient care in 31 provinces, autonomous regions and municipalities in mainland China, growth in the service volume contributed more than growth in the service price and intensity to the growth in the real total medical expenditures in public hospital inpatient and outpatient care in most provinces from 2011 to 2018 (table 3). Regarding inpatient care, the growth in service volume contributed more than the growth in service price and intensity to the growth in the real total medical expenditures in all provinces except for Tibet. For example, the growth in service volume was associated with 87.3% of the observed growth in the real total medical expenditure in the inpatient sector in Zhejiang Province (38.2 billion yuan of the 43.8 billion yuan increase). Regarding outpatient care, the growth in service volume contributed more to growth in public hospital outpatient real total medical expenditures in most provinces (23 of the 31 provinces).

Table 3.

Contributions of growths in the service volume and price and intensity to the growths of public hospital real total medical expenditures on inpatient and outpatient care in 31 provinces, autonomous regions and municipalities in mainland China, 2011–2018

| Province | Inpatient | Outpatient | ||

| Service volume | Price and intensity | Service volume | Price and intensity | |

| Beijing | 77.7 | 22.3 | 51.5 | 48.5 |

| Tianjin | 70.0 | 30.0 | 47.7 | 52.3* |

| Hebei | 56.7 | 43.3 | 67.2 | 32.8 |

| Shanxi | 62.4 | 37.6 | 60.8 | 39.2 |

| IM | 78.5 | 21.5 | 66.5 | 33.5 |

| Liaoning | 65.9 | 34.1 | 48.3 | 51.7* |

| Jilin | 54.8 | 45.2 | 45.2 | 54.8* |

| HLJ | 72.2 | 27.8 | 54.7 | 45.3 |

| Shanghai | 74.5 | 25.5 | 58.2 | 41.8 |

| Jiangsu | 77.7 | 22.3 | 60.5 | 39.5 |

| Zhejiang | 87.3 | 12.7 | 70.6 | 29.4 |

| Anhui | 76.1 | 23.9 | 65.3 | 34.7 |

| Fujian | 56.9 | 43.1 | 45.0 | 55.0* |

| Jiangxi | 59.6 | 40.4 | 46.1 | 53.9* |

| Shandong | 62.6 | 37.4 | 68.1 | 31.9 |

| Henan | 59.8 | 40.2 | 59.0 | 41.0 |

| Hubei | 67.4 | 32.6 | 70.4 | 29.6 |

| Hunan | 66.2 | 33.8 | 61.5 | 38.5 |

| Guangdong | 65.1 | 34.9 | 36.0 | 64.0* |

| Guangxi | 63.8 | 36.2 | 58.1 | 41.9 |

| Hainan | 68.9 | 31.1 | 55.7 | 44.3 |

| Chongqing | 76.1 | 23.9 | 59.1 | 40.9 |

| Sichuan | 68.9 | 31.1 | 59.8 | 40.2 |

| Guizhou | 82.3 | 17.7 | 76.0 | 24.0 |

| Yunnan | 79.6 | 20.4 | 58.1 | 41.9 |

| Tibet | 49.3 | 50.7* | 34.7 | 65.3* |

| Shaanxi | 69.5 | 30.5 | 63.4 | 36.6 |

| Gansu | 81.2 | 18.8 | 65.1 | 34.9 |

| Qinghai | 60.9 | 39.1 | 37.5 | 62.5* |

| Ningxia | 68.8 | 31.2 | 58.7 | 41.3 |

| Xinjiang | 63.6 | 36.4 | 63.7 | 36.3 |

Provincial expenditures per admission discharged or per visit, admission and visit volume data have only been available since 2011 from the China Health Statistical Yearbooks in 2012–2019.

*The exception of provinces where increases in price and intensity accounted for the largest increases in the real total medical expenditures of public hospitals.

HLJ, Heilongjiang; IM, Inner Mongolia; PHU, public hospitals’ utilisation; Pop size, population size.

Increases in hospital utilisation rates accounted for most increases in real total medical expenditures on inpatient and outpatient care in public hospitals in 31 provinces, autonomous regions and municipalities in mainland China from 2011 to 2018 (table 4). Regarding inpatient care, increases in hospital utilisation rates accounted for the largest increases in real total medical expenditures of public hospitals in all 31 provinces, autonomous regions and municipalities. Regarding outpatient care, increases in hospital utilisation rates accounted for the largest increases in real total medical expenditures of public hospitals in 25 provinces, autonomous regions and municipalities, except for six provinces, autonomous regions and municipalities, where increases in price and intensity accounted for the largest increases in the real total medical expenditures of public hospitals. Changes in the share of public hospital service utilisation were associated with reductions in both inpatient and outpatient real total medical expenditures of public hospitals in 30 provinces, autonomous regions and municipalities, except for Xinjiang. Changes in the population size were associated with increases in both inpatient and outpatient real total medical expenditures of public hospitals in 28 provinces, autonomous regions and municipalities, except for 3 provinces (Liaoning, Jilin and Heilong).

Table 4.

Contributions of changes in each factor in the 4-factor decomposition to the growth in real total medical expenditure on public hospital inpatient and outpatient care in 31 provinces, autonomous regions and municipalities in mainland China, 2011–2018

| Province | Inpatient | Outpatient | ||||||

| Pop. size | Utilisation rate | Share of PHU | Price and intensity | Pop. size | Utilisation rate | Share of PHU | Price and intensity | |

| Beijing | 9.5 | 75.2 | −7.0 | 22.2 | 11.5 | 50.8 | −10.8 | 48.6 |

| Tianjin | 24.4 | 44.6 | 1.2 | 29.8 | 35.8 | 37.2 | −25.4 | 52.4* |

| Hebei | 5.6 | 65.2 | −14.3 | 43.6 | 5.9 | 75.1 | −13.9 | 33.0 |

| Shanxi | 4.7 | 74.3 | −17.0 | 38.0 | 5.0 | 65.1 | −9.5 | 39.3 |

| IM | 3.0 | 82.6 | −7.2 | 21.6 | 3.0 | 69.5 | −6.0 | 33.5 |

| Liaoning | −1.0 | 92.3 | −25.8 | 34.6 | −1.1 | 71.0 | −22.0 | 52.1 |

| Jilin | −2.6 | 79.1 | −22.2 | 45.8 | −2.6 | 58.5 | −11.0 | 55.1 |

| HLJ | −2.9 | 98.3 | −23.6 | 28.1 | −3.9 | 78.0 | −19.7 | 45.6 |

| Shanghai | 4.6 | 72.0 | −2.0 | 25.5 | 6.0 | 55.1 | −2.9 | 41.8 |

| Jiangsu | 2.9 | 85.4 | −10.7 | 22.5 | 3.1 | 69.6 | −12.3 | 39.7 |

| Zhejiang | 7.6 | 88.8 | −9.1 | 12.7 | 9.1 | 72.1 | −10.7 | 29.4 |

| Anhui | 8.5 | 82.0 | −14.5 | 24.0 | 7.0 | 65.6 | −7.3 | 34.7 |

| Fujian | 9.4 | 57.5 | −9.9 | 43.1 | 8.3 | 40.1 | −3.3 | 54.9* |

| Jiangxi | 4.0 | 65.2 | −9.8 | 40.6 | 4.4 | 48.8 | −7.2 | 54.0* |

| Shandong | 5.9 | 70.4 | −13.9 | 37.6 | 6.2 | 73.3 | −11.5 | 32.0 |

| Henan | 2.6 | 76.5 | −20.0 | 40.9 | 3.0 | 72.2 | −16.7 | 41.5 |

| Hubei | 3.3 | 73.6 | −9.7 | 32.8 | 4.0 | 71.7 | −8.7 | 32.9 |

| Hunan | 6.0 | 79.4 | −19.5 | 34.2 | 6.3 | 68.1 | −13.1 | 38.7 |

| Guangdong | 10.3 | 60.6 | −5.8 | 34.8 | 12.5 | 26.9 | −3.3 | 63.9* |

| Guangxi | 6.9 | 63.8 | −7.0 | 36.3 | 7.9 | 52.8 | −2.5 | 41.8 |

| Hainan | 9.8 | 70.1 | −11.0 | 31.1 | 8.8 | 52.9 | −5.9 | 44.3 |

| Chongqing | 7.8 | 92.9 | −25.1 | 24.4 | 6.9 | 60.4 | −8.3 | 40.9 |

| Sichuan | 4.6 | 80.4 | −16.4 | 31.4 | 4.2 | 63.3 | −7.8 | 40.3 |

| Guizhou | 4.0 | 92.8 | −14.8 | 18.0 | 3.9 | 84.7 | −12.9 | 24.3 |

| Yunnan | 5.5 | 83.0 | −9.0 | 20.5 | 5.0 | 59.5 | −6.5 | 41.9 |

| Tibet | 10.8 | 55.5 | −17.5 | 51.3 | 12.1 | 36.6 | −14.3 | 65.6* |

| Shaanxi | 3.8 | 80.0 | −14.6 | 30.8 | 4.2 | 65.1 | −6.0 | 36.6 |

| Gansu | 3.3 | 86.9 | −9.0 | 18.9 | 3.3 | 67.9 | −6.2 | 34.9 |

| Qinghai | 7.2 | 65.4 | −11.8 | 39.3 | 8.0 | 42.0 | −12.7 | 62.7* |

| Ningxia | 11.2 | 77.7 | −20.3 | 31.5 | 9.2 | 57.8 | −8.3 | 41.3 |

| Xinjiang | 20.9 | 42.7 | 0.1 | 36.2 | 17.2 | 43.2 | 3.6 | 36.0 |

Provincial expenditures per admission discharged or per visit, admission and visit volume data have only been available since 2011 from the China Health Statistical Yearbooks in 2012–2019.

*The exception of provinces where increases in price and intensity accounted for the largest increases in the real total medical expenditures of public hospitals.

HLJ, Heilongjiang; IM, Inner Mongolia; PHU, public hospitals’ utilisation; Pop size, population size.

Discussion

This study measured the increases in inpatient and outpatient real total medical expenditures of public hospitals and how service use and price were collectively associated with these increases from 2008 to 2018. Our results show that the inpatient and outpatient real total medical expenditures of public hospitals increased annually, but the growth rate decreased. The growth in service use explains more of the growth in the real total medical expenditures of public hospitals in China than the growth in service price and intensity, especially for inpatient care.

The annual growth rate of inpatient and outpatient real total medical expenditures of public hospitals decreased by nearly half from 2013 to 2018 compared with that during the period from 2008 to 2013. This finding is consistent with the goal of containing the excess growth of medical expenditures of public hospital reform since 2012.13 Empirical studies in Beijing21 22 and Guangdong23 showed the same trend. Payment method reforms since 2011 have played a role in containing the excess growth of public hospital expenses.24

Our findings of the major drivers of public hospitals’ medical expenditures differ from those reported by Zhai et al, who used data from the 1993–2012 period and reported that the contribution of increasing health expenditure per prevalent case to the growth in health expenditures was more than 70%.3 This study contradicts our finding that approximately 70% of the increase in the inpatient real total medical expenditure of public hospitals was associated with the service volume based on data from the 2008–2018 period. Several differences can contribute to the varying results across the studies, such as different perspectives (eg, cost of disease vs hospital care) and component factors. A key source of the differences may be the varying time periods. Yip et al’s results closely parallel ours. Using data from the 2008–2017 period, Yip et al found that the increase in service volume accounted for approximately 70% of the increase in total health spending in China.4

Our findings also suggest that most of the service volume effect is due to an increase in the hospital utilisation rate. Our findings closely parallel Moses et al’s25 results. Moses et al’s decomposition of change in the volume of outpatient visits and inpatient admissions by countries from 1990 to 2016 showed that in China, more than 80% of the increase in volume of outpatient visits and inpatient admissions was due to an increase in age-sex utilisation rates, and less than 20% could be attributed to changes in the other three factors (population growth, population ageing and sex composition).25

Is the increase in service use acceptable? One study indicated that the need factor (ie, whether one had a chronic disease) was a dominant factor determining health service utilisation among rural residents in China.26 According to the China National Health Services Survey, the prevalence of chronic diseases among respondents aged 65 and above increased from 46.8% in 2008 to 62.3% in 2018.27 28 The share of population aged 65 and above increased from 8.3% in 2008 to 11.9% in 2018.17 Coupled with the soaring real gross domestic product and declining share of out-of-pocket spending on health services, the affordability of health services has improved.4 29 An extensive body of literature highlights the impact of expanding China’s basic medical insurance on increasinghealth service use, especially inpatient services.30–34 It is plausible that rising hospital service utilisation is related to the increase in the underlying need for and improvements in access to hospital services. However, the increase in health service utilisation may also be supply-induced.35However, because under utilisation was a concern before the health system reform initiated in 2009, the increase in hospital service utilisation currently represents as improvements in access.

These findings may inform health policy makers, whose current cost contains policy instruments mainly to control the cost per visit or per admission,13 that controlling price and intensity growth are crucial, but their effect on containing medical costs could be limited. In the coming years, health service utilisation is likely to increase due to the ageing population and the increased burden of non-communicable diseases. A study of China’s health expenditure projections showed that the increase in services per case of disease and unit cost would contribute 4.3 and 2.4 percentage points, respectively, of the 8.4% annual average growth rate in health expenditure during the 2015–2035 period.36 Controlling service utilisation growth can be essential through a nationwide effort for a healthier population, which could include disease prevention, healthy ageing, ensuring quality care and minimising unreasonable healthcare demands.37 38 Positive incentive mechanisms should be established to enhance an integrated medical and long-term care delivery system, which would be expected to increase outpatient and long-term care in primary facilities and prevent unnecessary hospitalisation.

However, this study has several limitations. First, the analysis relies on government administrative data, which may be subject to reporting errors. Second, due to the lack of a price index specific to the health sector in China, this study cannot distinguish between the contributions of service price and service intensity. Third, due to the lack of age-specific price and intensity of public hospitals’ inpatient and outpatient care for disease conditions in both base year and end year, this study did not consider changes in types of conditions prompting people to visit the hospitals and the ageing of the population. Further research is needed to identify the sources of the increase in public hospital medical expenditures by type of condition and by controlling for ageing, which could provide crucial evidence for decision makers.

Conclusions

We conclude that service use, rather than price, appears to be the major driver of the increases in China’s hospital medical expenditures. An important policy implication for China and other countries with similar drivers is that the effect of controlling price and intensity growth on containing medical costs could be limited and controlling service utilisation growth could be essential.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Guangyu Hu, Ayan Mao and Zhenzhen Rao for providing feedback on early paper drafts.

Footnotes

Contributors: XY and YL, acting as the guarantors of the article, designed and conceptualised the study. XY conducted the acquisition, analysis and interpretation of the data and drafted the manuscript. YL reviewed the manuscript. JL and KR reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. Raw data used in our study are publicly available, and all data sources have been cited in the methods section. The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

This study does not involve human participants.

References

- 1.Dieleman J, Campbell M, Chapin A, et al. Evolution and patterns of global health financing 1995–2014: development assistance for health, and government, prepaid private, and out-of-pocket health spending in 184 countries. The Lancet 2017;389:1981–2004. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30874-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fan VY, Savedoff WD. The health financing transition: a conceptual framework and empirical evidence. Soc Sci Med 2014;105:112–21. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.01.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhai T, Goss J, Li J. Main drivers of health expenditure growth in China: a decomposition analysis. BMC Health Serv Res 2017;17:185. 10.1186/s12913-017-2119-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yip W, Fu H, Chen AT, et al. 10 years of health-care reform in China: progress and gaps in universal health coverage. Lancet 2019;394:1192–204. 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32136-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roehrig CS, Rousseau DM. The growth in cost per case explains far more of US health spending increases than rising disease prevalence. Health Aff 2011;30:1657–63. 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Starr M, Dominiak L, Aizcorbe A. Decomposing growth in spending finds annual cost of treatment contributed most to spending growth, 1980–2006. Health Aff 2014;33:823–31. 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dieleman JL, Squires E, Bui AL, et al. Factors associated with increases in US health care spending, 1996-2013. JAMA 2017;318:1668–78. 10.1001/jama.2017.15927 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stucki M. Factors related to the change in Swiss inpatient costs by disease: a 6-factor decomposition. Eur J Health Econ 2021;22:195–221. 10.1007/s10198-020-01243-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alves JdeC, Osorio-de-Castro CGS, Wettermark B. Immunosuppressants in Brazil: underlying drivers of spending trends, 2010–2015. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res 2018;18:565–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.The National Health Commission . China health statistical Yearbook-2019. Beijing, China: Peking Union Medical College Press, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xu J, Jian W, Zhu K, et al. Reforming public hospital financing in China: progress and challenges. BMJ 2019;7:l4015. 10.1136/bmj.l4015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meng QY, Mills A, Wang LD. What can we learn from China’s health system reform? BMJ 2019;365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xinhua News Agency . Five departments of the state Council jointly issued a document to control the unreasonable increase of medical expenses in public hospitals, 2015. Available: http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2015-11/06/content_5005927.htm [Accessed 08 Dec 2020].

- 14.Fu H, Li L, Yip W. Intended and unintended impacts of price changes for drugs and medical services: evidence from China. Soc Sci Med 2018;211:114–22. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.06.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang Y, Zhang Y, Ma C, et al. Limited effects of the comprehensive pricing healthcare reform in China. Public Health 2019;175:4–7. 10.1016/j.puhe.2019.06.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xinhua News Agency . The state Council institutional reform plan, 2018. Available: http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2018-03/17/content_5275116.htm [Accessed 25 Jun 2021].

- 17.National Bureau of Statistics . China statistical Yearbook 2019. Beijing, China: China Statistics Press, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 18.International Monetary Fund . IMF Executive Board Concludes 2019 Article IV Consultation with the People’s Republic of China, 2019. Available: https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2019/08/09/pr19314-china-imf-executive-board-concludes-2019-article-iv-consultation [Accessed 30 Sep 2019].

- 19.Das Gupta P. Decomposition of the difference between two rates and its consistency when more than two populations are involved. Math Popul Stud 1991;3:105–25. 10.1080/08898489109525329 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Das Gupta P. Standardization and decomposition of rates: a users’s manual: US Department of Commerce, Economics and Statistics Administration. Bureau of the Census, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu X, Xu J, Yuan B, et al. Containing medical expenditure: lessons from reform of Beijing public hospitals. BMJ 2019;30:l2369. 10.1136/bmj.l2369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.BY L, Man XW, Fang YY. Analysis on the cost changes of total health expenditure of medical institutions in Beijing during the 12th 5-year plan period. Chi J Soc Med 2018;35:107–10. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Deng J, Song XG, CW X. Empirical analysis and optimization research of medical service price reform in urban public hospitals of Guangdong. Chinese Health Economy 2018;37:37–40. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yan XL, Rao KQ, LL H. Discussions on the progress and problems of public hospital payment system reforms in China. Chin J Hosp Admin 2015;31:84–6. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moses MW, Pedroza P, Baral R, et al. Funding and services needed to achieve universal health coverage: applications of global, regional, and national estimates of utilisation of outpatient visits and inpatient admissions from 1990 to 2016, and unit costs from 1995 to 2016. Lancet Public Health 2019;4:e49–73. 10.1016/S2468-2667(18)30213-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.YN L, Nong DX, Wei B. The impact of predisposing, enabling, and need factors in utilization of health services among rural residents in Guangxi, China. Bmc Health Services Research 2016;16:9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Center for Health Statistics and Information NHC . An analysis report of national health service survey in China, 2018. Beijing, China: People’s Medical Publishing House, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Center for Health Statistics and Information MOH . An analysis report of national health service survey in China, 2008. Beijing, China: Peking Union Medical College Press, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meng Q, Xu L, Zhang Y, et al. Trends in access to health services and financial protection in China between 2003 and 2011: a cross-sectional study. The Lancet 2012;379:805–14. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60278-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Su D, Chen Y-C, Gao H-X, et al. Effect of integrated urban and rural residents medical insurance on the utilisation of medical services by residents in China: a propensity score matching with difference-in-differences regression approach. BMJ Open 2019;9:E026408. 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-026408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu H, Zhao Z. Does health insurance matter? Evidence from China’s urban resident basic medical insurance. J Comp Econ 2014;42:1007–20. 10.1016/j.jce.2014.02.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang Y, Dong D, Xu L, et al. Equity in health care after 10 years of the new rural co-operative medical insurance scheme in China: an analysis of national survey data. The Lancet 2018;392:S35–35. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32664-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Babiarz KS, Miller G, Yi H, et al. China’s New Cooperative Medical Scheme Improved Finances Of Township Health Centers But Not The Number Of Patients Served. Health Aff 2012;31:1065–74. 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.1311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xu J, Wang J, King M, et al. Rural-Urban disparities in the utilization of mental health inpatient services in China: the role of health insurance. Int J Health Econ Manag 2018;18:377–93. 10.1007/s10754-018-9238-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang H, HM H, Wu C. Impact of China’s Public Hospital Reform on Healthcare Expenditures and Utilization: A Case Study in ZJ Province. Plos One 2015;10. 10.1371/journal.pone.0143130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhai T, Goss J, Dmytraczenko T, et al. China's health expenditure projections to 2035: future trajectory and the estimated impact of reforms. Health Aff 2019;38:835–43. 10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Meng Y, Yan X, li X. Principal concept and practices and enlightenment of managing health demand in developed countries. Chinese Journal of Health Management 2016;10:241–5. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stadhouders N, Kruse F, Tanke M, et al. Effective healthcare cost-containment policies: a systematic review. Health Policy 2019;123:71–9. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2018.10.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2020-048308supp001.pdf (158.8KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. Raw data used in our study are publicly available, and all data sources have been cited in the methods section. The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.